|

|

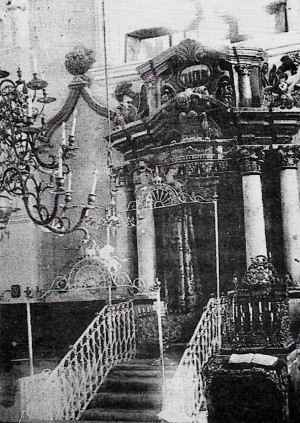

near the Torah Ark of the old synagogue

|

|

|

|

[Page 50]

by Nathan Michael Gelber

Translation by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

Brody was such a unique city, that one of the Austrian officials nicknamed it “Jerusalem of Austria” after Austria seized Galicia. Jewish life, economic and cultural, throbbed in it to its fullest.

Even before Austria occupied it, the Jewish community of Brody was known as a community of scholars, Rabbis, and leaders of the Council of Four Lands and of Districts Councils. The families who ruled the community – Babad, Ravits, Rabinovits, Shatzkes and Bik – succeeded to put Brody on the map by establishing Yeshivas and Kloizes [communal houses of learning, praying and gathering – MK] and by attracting a large number of knowledgeable Rabbis to the city. This way, they managed to establish the city not only as a center of Torah but also of Jewish law – a place where everybody turns to, with tens and hundreds of Rabbis and judges, experts in Jewish law and Halakha.

The prominent families that ruled in the city knew how to improve the community institutions and make Brody an exemplary community in pre–partition Poland. They were also able to defend Brody's reputation, and in time of distress, protect its rights and regulations.

Brody was one of the few cities that the commissars of the Austrian emperor, who came to take over this asset when it fell into their hands, found it necessary to report about in minute details. In this region, which was named Galicia after the partition of Poland, the commissars found for the first time Jews who received secular education, Jewish physicians and merchants, who were familiar with Latin and German languages and culture. Some of these physicians were: Dr. Vishnovitser and the prominent Dr. Yitskhak Ravits, (son of the Rabbi who authored the book Keter Yosef) both studied and graduated in Italy, and Dr. Avraham Uziel who studied at several universities and who welcomed the conquering army of Austria with a beautiful speech, which was also printed in the newspaper Wiener Diarium. These people gave the city an aura of splendor and magic and helped it to become the favorite over other cities in the eastern corners of the Habsburg Monarchy.

The greatest development of the city occurred during the Austrian period. Under the Austrian rule, it became the center of the flow of commerce between east and west. The lines of commerce and transportation between Breslau, Leipzig, Manchester, Livorno and Vienna on one side and Berdichev, Kiev as well as the cities of Valachia, Moldavia and Greece and even Istanbul on the other side, all met here. Therefore, it is no wonder that the city experienced a busy life, where many merchants, knowledgeable in many languages settled. It obviously attracted many Jewish teachers who taught Jewish children different foreign languages.

These conditions ensured that the city's Jews would not remain frozen in their spiritual and cultural life, but assimilate, more easily than other Galicia Jews, into the life of the universal civilization. The slogans of the Enlightenment movement found a fertile soil here. The city youths were captured by it and became its pioneers. Dov–Ber Ginzburg, Yaakov–Shmuel Bik, Mendel Lapin, Dr. Yitskhak Erter and R'Nachman Krochmal created a new reputation of

[Page 51]

the city as a “city of enlightenment” that fought against the Chasidic Judaism on one side and the Mitnagdim movement on the other. It is worthwhile, however, to note that although Brody was known as an Enlightened–city, with a tradition of education and learning, the Chasidic spirit filled its large as well as small Kloizes. The Chasidic movement was the one that continued to spin the yarn of its mystical spirit over the centers of learning for generations, especially over the largest Kloiz (Grand Kloiz) which served as a house of learning for many exceptionally wise and scholarly people – the Brody Sages and Kloiz Sages. Among them were Rabbi Khaim Tsanzer, whom the people of his generation named the “Divine Kabbalist Chasidic Rabbi”, Rabbi Moshe Ostrer, a known Magid Meisharim [Jewish preacher – MK], (who signed, among others, the document of excommunication of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschutz), Rabbi Naftali Margaliot, Rabbi Efraim Zalman Margaliot and Rabbi Mendel Zolkover. All of these Rabbis were considered “princes,” grand rabbis, scholars and holy men of the Jewish community of Brody. These people lived, until the last generation, in the aura of the Chasidic legend. One cannot count the stories we heard in our youth about the Baal–Shem–Tov in Brody and the wars he conducted against his opponents, or about Rabbi Gershon Kitover, and the Magid Rabbi Shlomo Kluger and his fights against the innovations of the Eenlightenment movement (particularly concerning the transport of the dead on a horse drawn cart).

We also need to note, that the universal humanitarian principles, adopted by the Galician Enlightenment movement, were not used by the followers as an excuse to abandon the Jewish tradition. For example, one of the movement's scholars, Moshe Stern, published a letter in the newspaper “Kokhvei Yitskhak” (Yitskhak's Stars) in which he argued against those who denounce the Jewish particular clothing. Furthermore, there were people who claimed that seeds of the new Jewish national movement came from Brody scholars, as it is easy to identify in this movement a clear self–awareness which is based on the appreciation of our ancestral heritage and historical tradition. Brody was saturated with Jewish folklore and national feelings. Therefore we cannot be surprised by the story of Rabbi Yaakov Shmuel Bik who adopted the Enlightenment and then came back to Chasidism, claiming that he saw in it and in the then spoken national language (Yiddish) the foundations to the Jewish tradition so dear to the soul of the Jewish people. Another story, in which the national tie is more pronounced – is the story of the “Brody Singers,” with Berl Broder (Margaliot) as their leader. They were the authors of amusing poems, drenched in humor, in which the satire was aimed against the social conditions of the Jews.

One of the first educated authors, born in Brody, who wrote already in German, was Leo Hertsberg–Frenkel. His stories about the life of the Jews of Galicia were leaning toward the Jews being “half – Asian”. However, one can easily distinguish between them and those of his cousin – Karl Emil Franzus, who also wrote about the life of the Jews of Galicia. The reader of Leo Hertsberg–Frenkel's “Polnische Juden” [“Polish Jews”–MK], can easily distinguish between them since Leo's stories were inherently imprinted with Jewish folklore.

The gallery of people of the Enlightenment movement in Brody, or from Brody, is large. This movement included people such as: Rabbi Moshe Mordekhai Yuval, Berish Blumenfeld, Yitskhak Blumenfeld and Chaim Gorfunkel. The movement also included Mordekhai Ben–Avigdor Ushpits who was the head of the “Bank of Halbershtam & Nirenshtein” and who studied Jewish Studies in his spare time, as well as Khaim Ginzburg, who was also a Germen poet, Rabbi Yaakov Toporover, Marcus Kalir, Yaakov Levin, Moshe Margaliot. Other people of the movement were Israel Roll (the brilliant translator of classical languages), Rabbi Mordekhai Sterlisker, who lived in Brody until 1851 and who was named the “Lion of the Poets”, Hirsh Reitman (initially Yosef Perl's librarian and later the principal of the primary school in Brody), who wrote the outstanding Yiddish parody “Der Kitel” (1863) to Shiller's “Glocke” [“the bell” 1863], and Y. Trakhtenberg and Yehoshua Heshil Schor.

[Page 52]

Ha'Ivri [The Hebrew–MK] and “Ivri Anokhi”[I am Hebrew MK], a newspaper that was published alternately under each name (in order to bypass the newspaper tax), edited by Barukh Verber (during the years 1865 – 1876) and later by his son Yaakov Verber (during the years 1876 – 1890), was loyal to the ideals of the Enlightenment movement as well as to our tradition. At the same time it fought bitterly against the newspaper of the Society of “Religion Keepers” in Lvov, which started its publication in 1873. However, when the national awakening started and the movement toward national independence in our land began to spread, “the Hebrew” did not understand its spirit. It fought against the new trend of emigration to Eretz Israel, and demanded to direct Russian refugees, that passed through the city Brody in droves, toward the United States. He believed that the freedom sun would shine on our nation only in the US.

However, this resistance was not able to prevent the sprouting of the seeds of the Jewish national movement among the city Jewish intelligentsia. People started to comprehend the tragedy imbedded in the situation of the Jews, and recognized the need for a change oriented toward the goals of the Zionist movement. Indeed, the Zionist movement, which penetrated Galicia little by little, with the flow of the pogroms refugees, started to take hold more rapidly, and soon Brody became an important center of the Zionist movement. The Jewish youths who joined the movement enthusiastically, centered their activities on studying Hebrew literature and Hebrew language. Their activities made Brody a model for all other cities and towns of Galicia.

High–school students, who came from the Torah Schools to acquire a general education, taught others in Hebrew classes according to the method of studying “Hebrew in Hebrew”. They were guided by the Brody Rabbi's son, Refael Soferman, who intended to become a Hebrew teacher.

Yehuda Leib Landau, Yehuda Pilpel, Braindel Golde Letster, Refael Soferman, Michael Berkowits, Avraham Robinson, M. D. Anderman and Chaim Tartakover, were some of the people who laid the foundations to the organized Zionist movement in Brody. The awareness of Zionism spread naturally throughout all of the Jewish circles in the city as the people mentioned above continued to expand on their initial activity. Newspapers helped to disseminate the news about developments in the national movement. Jewish students who studied in universities in Vienna and Lvov brought with them copies of the newspaper “Selbstemanzipation” [Self– Emancipation – MK], that was published in Vienna under the editorship of Dr. Natan Birenbaum. Through this newspaper, the news about the establishment of the first Zionist societies became known in Brody.

Initially, the “upper” layers of the Jewish society in Brody did not want to accept the fact that enormous changes of the state of the Jewish nation and its role among other nations are occurring among the Jewish public in Galicia and other countries. However, just a few years later – in 1890 – the first Zionist society – “Zion” was established in Brody. This society had a major impact on the atmosphere among the Jewish youths. The first Maccabee banquet took place in 1891. David Anderman gave a speech in Hebrew about the historical importance of the holiday of the Maccabees. The Hebrew author Reuven Asher Broides, who also spoke in Hebrew, made a very strong impression on his listeners. Many women decided to start learning Hebrew, and many assimilators decided to join the National camp because of his speech. Zigmund Lifshitz and David Hirsh Tiger from Lvov explained, in German and Yiddish, the objectives of the National Jewish movement.

Gradually, the best young people congregated around the “Zion” society. They supplemented their Hebrew knowledge and attended lectures about the problems of the Jewish world. The intelligentsia and the Jewish youths

[Page 53]

recognized the fact that the world is undergoing major changes, and that the attitude toward Jews among the other nations is not what they expected from the emancipation. Even the assimilators felt that they are not welcomed by the gentiles and that the Poles see in them, at best, allies to their own national–political aspirations. Those who came from the Enlightenment movement were interested in “renewing the pride of the Hebrew language, which was almost forgotten by our youth.”

In 1886/7, a group of young people, under the initiative of Yehuda Leib Pilpel, acted “to encourage the spirit of the nation, and to uproot the assimilation which was becoming more and more popular. We shall celebrate our national holidays, and bring back the Hebrew language literally on the stage – perform a show in Hebrew, spoken as a live language before the audience.” As part of their effort, they asked Yehuda Leib Landau, who studied in Brody at the time, “to utilize his talents and his love for his nation to write a play in Hebrew.” According to their instructions, “the play was supposed to demonstrate the victory of the nationals over the assimilators”. The play, “There is hope”, consisted of three acts and was written in simple language for easy acceptance by the audience. It described an episode from the life of a Jewish family, in which the father wished to marry his daughter to a medical student, a Max Blem – an assimilated Polish Jew. The play was performed at a banquet organized in memory of Peretz Smolenskin on 23 February 1893.

The “Zion” Society widened its activities and propaganda for Jewish revival. Many among the Jewish intelligentsia joined the movement despite the strong hype by “The Ivri” against the idea of settlement in Eretz Israel and against the national Jewish movement. The Zionists preached continuously about the national idea among the high–school students. Classes for the Hebrew language, Jewish history and history of Eretz Israel were added during the years 1893 – 1895. Older students were also active in this area and used their free time from their universities to win the hearts of the young people for the idea of the national revival.

When Dr. Theodor Herzl's name started to be known, the enthusiasm for the idea of Zionism was also heightened in Brody. “Zion” Society and Brody youths sent congratulations telegrams to the first Zionist Congress in Basel (27 August 1897). Dr. Herzl was elected honorary president of the “Zion” Society during the gathering that took place on 11 September 1898 in the “Zion” clubhouse.

In 1899, the university students who came home to Brody during the academic vacation, started to organize an academic Zionist society. Chaim Tartakover (1883 – 1944) led all Zionist–cultural activity and succeeded to gather around him a group of male and female students who were devoted to the Zionist idea. He organized the high–school students and youths from all other Jewish population layers. Tartakover also tried, for the first time, to lead them toward pioneering training. Their initial activities involved the organization of national holidays and cultural celebrations. In 1903, Schenkar, Chaim Tartakover, Leon Balaban, Zeev Makh, Zeev Rosenfeld, Barukh Tselnik, Yitshak Hammerman and Anzlem Shtromvasser established the first Zionist society for university students – Techia [Revival– MK]. The society functioned until 1939 and was active in many Zionist and cultural areas. It employed counselors to guide their members in the spirit of national–Zionism and had a significant influence on the development of the Zionist movement in Brody.

[Page 54]

Intensification of the Zionist education and activity occurred during the years 1904 – 1906. By the initiative and with the assistance of the teacher Yosef Aharonovitz, who later became an author and a labor leader in Eretz Israel, the first pioneering organization in Galicia – Chalutzei Zion [“Pioneers of Zion”– MK] was established. The organization was formed under the impact of the “Letter from Eretz Israel” sent by Aharon David Gordon, which created an enormous impression on the Brody youth.

In 1908 – 1910, the conference of the central committee for Cultural Activity and the Hebrew Language of the High–school students' movement – Tse'irei Zion [“Zion Youths”– MK] for the entire province of Galicia was held in Brody.

During the years 1912 – 1914 the Zionist activity concentrated on consolidating its forces, expanding the Hebrew school, enlarging the library and strengthening its loan fund. The fund under the management of Perets Beharav helped small merchants and craft businesses and considerably contributed to their economic success.

In the cultural area, the drama club was active under the management of S. Mirtski, and the Ivriya group concentrated on the dissemination of the Hebrew language and culture. The Hebrew movement thrived in particular among the high–school students and the orthodox youths. The association Hashahar [“Dawn”– MK] was established through the initiative of Moshe Rosenblum, Krochmal, Teller, and Yosef Neigebohr. The Hebrew teachers of the movement and older students taught Hebrew to the students of the Beit Hamidrash [Torah School– MK], as well as history of the Hebrew literature, Jewish history and general sciences. Fertile cultural work among the working youths was done by the association of Poalei Zion [“Workers of Zion”– MK]. Their activities included courses and evening classes that concentrated on the national spirit. Mendel Zinger, Vitlis and Shalom Kupfer headed the association.

During World War II, the fate of the Brody Jewish community was similar to the fate of all other Jewish communities in Poland. Until war broke out between Germany and Russia the Jews in Brody enjoyed a relatively secure life; however, with the German invasion of Poland an extermination camp was established in Brody (in February 1942), under the command of the Nazi Hauptsturmführer Franz Warzok and his assistant Vogel. As many as 364 Jews were murdered immediately. In September 1943, the camp was disbanded and the 600 Jews who were in the camp at the time were murdered in a forest near Brody. The rest of the Brody Jews were sent to the camp on Yanovski Street in Lvov. Their fate was similar to that of the other Jewish communities in the Nazi occupied areas. Very few managed to escape to Russia; the Jewish population was totally annihilated.

Brody, a Jewish city with a brilliant history that existed more than four hundred years died. It was wiped out of the map of the diaspora.

[Page 55]

by Adela Landau Misis

Translation by John Kallir

Note: This selection was translated from Adele Landau Misis's original German manuscript by John Kallir, a

descendant of the author, rather than from the Hebrew version which appears in Ner Tamid—Yizkor leBrody

When, in the middle of the last century, a fire alarm sounded in our native town of Brody, panic fear would seize old and young. From past experience they knew: the town is lost! There were no defenses against the raging element. Neither in Brody nor in its environment was there a river, not even a little brook, not a pond, not a spring with sufficient water. Pumps found in a few streets would, after strenuous efforts, send forth a feeble flow of greenish-yellowish water. The wise town fathers had ordered a large barrel (katjke) to be placed near each pump, to be filled with water all the way to the top in case of an emergency. The barrels were there but half empty, filled with a thick greenish sludge, more likely to stick in the hose than put out a fire. In the yard of every house there stood a rain barrel, with buckets and fire hooks nearby. But rainwater was used for the laundry and other domestic purposes, while in many houses the buckets had lost their bottoms and the hooks their iron. In addition, the town had a few antediluvian engines of ancient design and, I'd guess, about a dozen firefighters. Now, unless there was absolutely no wind, if a shingle roof in the poor quarter caught fire, it would swiftly spread and the entire town (which was really three-quarters poor) would be reduced to ruins within hours. That happened again and again, every eight or nine years. The most recent fire had occurred in 1859, but I don't remember it because I was only a year old then. The stories of parents and grandparents, however, made it very real and frightening.

One morning in May, 1867, Alexander, who slept in our parents' bedroom, woke up crying. He had dreamed the town was on fire, all the katjkes were empty, and the fire kept going. Our parents were surprised how a five-year-old could know the connection between “katjkes” and “fire.” In the afternoon of that day (Lag B'omer), there was a wedding feast of people we knew in a heifel (villa) in the suburbs. Grandmother Landau loved to attend such occasions. She borrowed the carriage of the Kallir grandparents and took Alexander and me along. Returning in late afternoon, we had reached Lesznow Lane close to our home and grandmother was preparing a tip for the coachman. In those days, small denominations were printed on sheets, like postage stamps, to be cut as needed. Next time you're in Vienna, I'll show you a few. Anyway, grandmother pulled a penny sheet from her bag when a sudden gust of wind tore it from her hands. She was about to shout something to the coachman but, just at the same moment, the storm bell began ringing from the church steeple and desperate cries – Fire! Fire! – arose from all sides. Within two minutes we reached home, where everyone was already frantically preparing for our flight, even though the alarm had rung only a few moments before. The office personnel carried massive ledgers that had to be packed in special bags. In the living room, mother and grandmother had opened the big iron “cash box,” where silver candlesticks, dining utensils and jewelry were usually stored. These, too, went into special bags. Also, food, warm clothing and whatever else was needed for our flight. The horses were unharnessed from the carriage and hitched to the dray. Then Uncle Jules raced with the dray to the nearby hospital, loaded up the patients and drove them to safety. I don't know where he took them. Upon his return, women, children and bags were put on the dray and taken away, while the men stayed behind to protect the house. Fanny was only three months old and mother not well. Nurse Libe's baby was brought to us by the woman who usually took care of it. She probably was busy with her own kids. Since no one else was available, they entrusted her baby to me and I watched it all night long. The dray took us far enough away so sparks from the flames couldn't reach us. There we camped on a freshly ploughed field on bundles and bags like emigrants. All around us there were similar groups. Weeping, moaning and children's cries could be heard. There were sick people, as well as pregnant women, and we had to help to the best of our ability since not everyone was as organized and practical as my mother and grandmother. And so we spent a long May night, watching the burning city, trying to guess whose house was going up in flames. Suddenly, little Alexander said, “You see, that's just how it was burning last night!” That reminded us of his dream. When men came up from the city from time to time, their reports were not encouraging, although there were occasional miraculous exceptions with houses remaining untouched in a sea of flames. My dear father came once, reporting that the house of the Landau grandparents had caught fire. Entering the burning house wrapped in wet sheets, grandfather, Uncle Doctor and he were able to salvage some things. Actually, that may not have been necessary for, so far as I remember, only the roof, the entrance gate and a few windows and doors burned, but the interior had remained unscathed. In “modern” fires much that's been saved from the flames is destroyed later by water. That's one problem we didn't have in Brody.

The house of the Kallir grandparents remained untouched, thanks partly to Uncle Jules, who tore down the shingle roof of the adjoining house in back, ignoring the protests of Mrs Tysmenitzer, its owner. Another guardian angel must have protected the front of their house. Their neighbor's house burned, and so did Nirenstein's in the narrow lane opposite. When the iron shade covering our parents' living room window was pulled up afterwards, they discovered a small burnt hole in the window frame. A spark must have sneaked in but it died from lack of air. Even stranger, the wooden garbage bin in the yard had burned without spreading the fire. The roof of our house was made of iron, whereas that of the Nirensteins was made of zinc, which turned out to be very dangerous. The zinc melted and ran down in hot streams, so no one could come close. Long after the fire, we liked to play with those odd shapes, shining like silver, which we found lying all around. People teased Hirsch Braun that his head was so hard, he didn't mind when the molten metal dropped on his bald spot. One of the undamaged buildings belonged to a certain Mr. Czaczkes, who sent this telegram to his brother in Lemberg:

“BRODY DESTROYED. OUR HOUSE SAVED. CELEBRATE!”With the dawning day the fire, though less violent, was still burning. We were freezing and exhausted when the cart came to take us and our bundles to Uncle Jules' villa at a safe distance from the fire. We joined a crowd of strangers who had also found refuge there. We stretched out on straw mattresses, brewed tea and relaxed until, finally, we could return to town.

Our townhouse had turned into a campground. People who had suffered merely the loss of their roof or other outside damage to their home returned and adjusted as best they could. But others, who had lost everything in the flames, turned to the lucky few who could offer them a temporary abode. Of course, our house was a popular refuge and we took care of many relatives and friends. The fiery sky had been visible for miles around and people from neighboring villages brought clothing and food (mostly bread). Aunt Libe, a sister of Grandfather Landau (I'll tell you more about her some other time) came to Brody from nearby Witkow and shared a room with Grandmother Kallir and me. She grumbled about the frivolity of “big city people,” because grandmother owned a few nightingales which kept singing all through the night.

The terrible news of the disaster spread around the world. Newspapers published extensive reports, as well as appeals, with gratifying results. Contributions arrived from all over. I remember the large sums from Hamburg, which might have once suffered a similar misfortune. Next, it became essential to distribute the collections fairly, to make sure not even the smallest amount was spent wastefully. In this, my dear father played an important role. He had contributed to the public welfare on previous occasions, founding the first orphanage in Galicia in 1859, distributing food and Rumford Soups during times of rising prices. Now he became the head of a “Committee for the Fire Victims,” organizing the entire project and leading it to completion. As a consequence, he was awarded Honorary Citizenship although he was only 41 years of age. (Uncle Alexander will show you the handsome diploma, next time you're in Vienna.) All applications, referred to as Bietes (from German Bitten), were addressed to him, to be investigated thoroughly and fairly. Father insisted that the town's reconstruction must receive top priority. Everything else had to wait. All those little houses were rebuilt with better material, better construction and, most important, with iron roofs. Shingle roofs were outlawed. Clearly, that was the right thing, as can be gathered from the fact that no major fires have occurred in Brody since then, i.e. in 62 years! One additional credit is due to the young people who organized a Volunteer Fire Department, with modern equipment and frequent practice sessions.

by A. Yehuda (Osterzetzer)

Translation by Dr. Nitzan Lebovic

Donated by Dr. Lebovic and Stephen Fein

Not too long after its founding, Brody became an important center of commerce for many countries, from the coasts of the Black Sea to the lands at the North Sea, from Odessa to Hamburg. Merchants from Milan to Hamburg and merchants from Berdyczów, Poltava, Nizhni Novgorod and other towns opened in Brody branches of their businesses. The geographic location of the town enabled it to develop as a trade center between Eastern Europe and Western Europe.

About 15,000 residents settled in the city. Two thirds of them were Jews. Their languages were Yiddish and German, because they had originated in Germany. In 1772, the city was annexed to the Kingdom of Austria. Seven years later, it was declared a free city for trade, which meant that there was no need in Brody to pay customs, not for trade coming in and not for trade going out to any country.

So the importance of Brody grew as a transportation city between east and west. Many trade houses were opened in the town, from many countries. The cultural tendency was pro-Western, with the German language prominent. I remember the street called Kallir, after Alexander Kallir, who came from Germany to Brody in 1785.

Tradesmen from our town used to travel to Lipsia [Leipzig] often, in order to buy textiles, household products, and everything anyone could trade in; and they transferred to Lipsia raw materials such as calf leather and furs. Trains did not exist at the time, so everything was transported in hundreds of wagons carried by horses. The convoy used to leave at the beginning of the fall from Brody to Berdyczów, Kharkov, Poltava and the other urban centers in Poland and Russia, as well as to the west. The wagons always visited the most important fairs. Upon arrival, success was guaranteed.

The wagons transported thousands of tons of goods. When in 1800 a large fire broke out in Brody, the trade fair collapsed in Lipsia. The importance of this trade can be gleaned from the decade between 1770-1780, when our townsmen added to Lipsia gross income of about half a million ducats (gold coins) in cash.

The most important professions of the Brodyites in this town [in Leipzig] were fur and leather work, industrialism and trade. For example, in 1800 there were in Lipsia around 50 small business merchants from Brody. They received a temporary license to reside in town, and after a few years received licenses for permanent residency. They were forced to swear on the Bible in a festive celebration, with representatives from the city hall and witnesses (59) from the Jewish community. Only then did they get public positions as city clerks.

Brody was one of the first cities in the world to trade in fur and different professions related to leather cultivation. In 1818, of 35 traders in Lipsia who were sworn in, 28 were Jews, among them 14 from Brody. These posts carried much weight in the eyes of our townspeople, because their occupiers won in time also license for permanent residency in Lipsia. Those Brodyites did not leave their businesses in Brody. They conducted business in both cities simultaneously. At the end of the last century, when emancipation was decided on in Germany, there were already around 1000 fur merchants in Lipsia, about 500 of them Jews. Also, 50% of the 1200 shops were owned by Jews. Those shops traded and sold coats and suits, hats and gloves, shoes, boots, sandals, hand bags, toys etc. The improvement in rights was obvious if we take into consideration that up till the 16th century, Jewish presence in Lipsia was forbidden. Nevertheless, at the same time Jews had the right to visit the town as traders at fairs and to build there storage places and shops. In mid 18th century the traders and visitors started to establish their own little prayer houses, still temporary. The Brodyites also established their own synagogue, which is called the “Brody Synagogue” to our day. Next to their synagogue they opened also a schul. If during the fair someone died, they'd transfer the corpse to be buried in Dessau, till in 1811 Yoel Schlesinger paid to the city of Lipsia hundreds of talers as rent for a cemetery. That was the first and only [Brody] cemetery [in Leipzig].

Other Brodyites who received licenses to stay and work in Lipsia were: Moshe Hischl Yechis, Yaakov David Risberg and Meir Michael Torkotan. Other than these, whose names we know, in 1872 there were other merchants from Brody, including the trade place of the Hermlins. This family is known to have conducted business in Lipsia for five straight generations. One Yeshiva-Bucher with an ability to write, Yosef Ehrlich, who was born in Brody, published at the end of the 18th century a booklet in which he described the history of this family. It is possible to read [information] there about the situation of the Jews of Brody and about the family atmosphere and economy of the Lipsia Jews.

by David Davidowitz

Translation by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

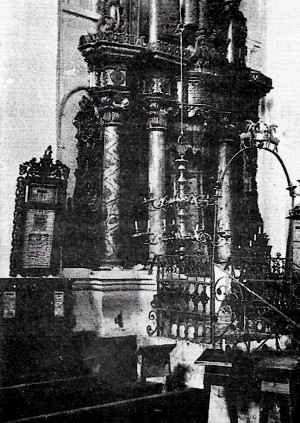

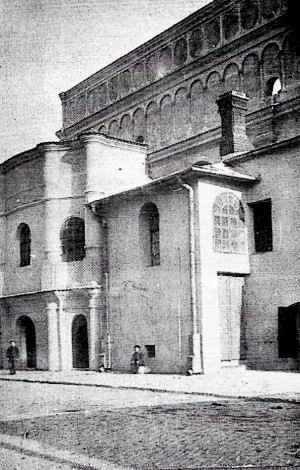

Like the community itself, even the synagogue in Brod – this old Jewish monument with the impressive classic lines, one of the most beautiful fortress-like synagogues in Poland – was destroyed to its foundations.

In his journal-book, S. Ansky writes: “I visited the old synagogue in Brody, which played an important role in the cultural life of the Jews. Here sat the “Wise Men of the Kloiz” [ Kloiz was the name given to a house of learning and prayer. MK], the giants of the Jewish intelligentsia of that time, R'Yekhezkel Landoi, R'Meir Margalyot and others. Here the fight against the Chasidic movement was concentrated. A whole period of Jewish life was connected with Brody and its Kloiz. The synagogue was ancient, and most beautiful inside. The gabay [synagogue administrator, MK] showed me old silverware, 'Torah crowns', lamps and lanterns from the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries, as well as valuable Parokhot [curtains covering the front of the Holy Ark in the synagogue. MK]”.

Indeed the synagogue excelled not only from the architectural point of view, but also by its collection of ritual objects, one of the richest and most interesting synagogue collections in Poland. We can mention here, that in the ritual exhibition that took place in Lvov in 1894, a gilded silver platter rich in decoration from the Brody synagogue was displayed. In the center of the platter, inside a small indentation, a box with filigreed doors between four filigreed columns was fixed. The tops of the columns were decorated with birds and deer heads. A crown was placed above the indentation, and a small balcony with five sculpted figures on it, depicting the ceremony of the removal of the Torah from the Holy Ark. Beyond this group, above the balcony the figure of a shofar blower was placed. The platter was decorated on its upper part with an eagle crowned with a royal crown, and on its lower part with ornamental wreaths of leaves and animals (a bear in the center). The platter originated in the eighteenth century. Another valuable object from the same synagogue displayed in the exhibition was a Torah Crown, richly decorated with ornaments from the animal kingdom (oryx, eagles, oxen and bears) as well as biblical figures.

Among other ritual objects from the synagogue, it is worthwhile to mention the magnificent Hanukkah Menorah, richly decorated with ornaments from the animal kingdom (including winged lions).

The synagogue itself was decorated with paintings painted by many artists, among them the Russian painter Lokomski, a great admirer of the Brody community. This is the place to mention an interesting historical detail: During the years 1755 – 1739, the city was under the hegemony of the Catholic Bishop of Luchek and Brisk, Franchishek Antony Kubeilski. This priest instituted sermons in the synagogue of Brody that preached conversion to Christianity. He made such sermons himself to the elders of the community and its leaders (such sermons were frequent in western Catholic countries in cities such as Rome and Vienna, but have never been instituted in Poland before).

[Page 62]

We learnt about the fate of Jewish Brody and its famous synagogue from a letter that was sent by Dr. M. Weiss, one of Brody's survivors, to the author Dov Sadan (Schtock) in February 1946: ”…I have never imagined… that on the slopes of this mountain (Olesko mountain), in the quarry, our birthplace notables would dig up their graves. After the annihilation of the ghetto, 300 people from our city worked in the death camp located in the Olesko Monastery. They were all shot and murdered on one day in the month of Iyar year 5703 (May 1943). The city of Brody is half in ruins and it is completely deserted. In what used to be the ghetto, between the Hospital Street and the railroad tracks, in the market, in the fish market and their environs, there are mounds and heaps of ruins. Only the walls of the old synagogue are standing in their splendor. The synagogue looks like the Coliseum from afar. From the Jews of Brody, only enough for a minyan have survived…”

This is how a whole period of Jewish life which, according to Ansky, was inseparable from its kloiz, was interrupted and ended with the tragic destruction of Jewish life in the city and the destruction of the magnificent synagogue.

[Page 63]

|

|

|||

near the Torah Ark of the old synagogue |

||||

|

|

|||

[Page 64]

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brody, Ukraine

Brody, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 13 May 2020 by LA