|

|

[Page 1]

by N. M. Gelbar

The city of Zolkiew was built on the land of the nearby village of Vynnyky, which existed since 1398. The village paid a tithe (zhieszenica) to the Archbishop of Halicz, Jakob Strafa. Tatars invaded the territory during the 14th and 15th centuries and they wrecked most of the dwellings and Vynnyky also suffered. The entire town was practically burned down in 1514, however, its leader Andrzej Wisucki undertook the task to rebuild it. In his old age, in the year 1560, Andrzej Wisucki left all of his possessions – Vynnyky, Soposzyn, Maczaszun, Glinski, Wala, Miszianica – to his comrade Stanislaw Zolkiewski, a member of a family of the nobility that was located close to the village of Zolkiew, in the district of Krasnostov, which had a connection to Chelm. Zolkiewski took an active part of his life in city matters, and was also a representative to the Sejm[1]. In the year 1569, he signed the document that served to unify Lithuania and Poland. For these services, he received as a privilege, ownership of the voiedestvo[2] of Belz. After his death in 1596, his second son Stanislaw II (1550–1620) inherited Vynnyky. After Stanislaw completed his studies outside of the country, he enlisted in the military and took part in the war against the Czar, Ivan the Terrible. He succeeded in drawing near to Pskov (1582) and in the war against the Austrian Nobleman Maximilian, an enemy of the Polish King Zygmunt III. He was appointed Hetman[3] by the King the Starostvo[4] of Hrubieszow. He devoted a great deal of his attention to the village of Vynnyky, where he resided.

|

|

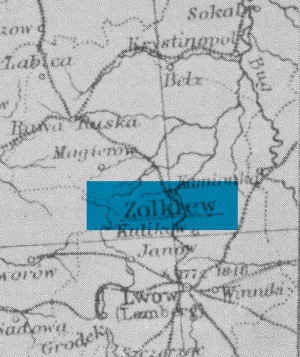

| A map of Zolkiew and its environs on a map of Poland before the Second World War |

[Page 2]

When the Tatars attacked Reisen[5] again in 1594, he gave an order to fortify the village with stout walls. After his death, his wife, Regina, from the house of Herbert Mapelstein, wrote a letter to request permission to call the newly-erected fortress, Zolkiew. The village of Vynnyky became a ‘city,’ through this, and in 1598 through the “Acts of the City” by the leadership committee. On January 1, Zolkiewski created an order to have the poor of the city dressed in accordance with the Catholic faith.

On February 22, 1603, King Zygmunt III changed the name of Zolkiew to the name Zolkiewski, in recognition of his victory near Rawa Rusk, and with an official document (Piwszwili Lokatzini), on the basis of the Magdeburg Laws[6]. The King granted free voting privileges for the office of Mayor, the right to carry a sword (Prawda miecka), he excused the city dwellers from the taxes of Poland and Lithuania, and instituted four fair days a year, and two such fairs bi-weekly.

The center of the city was surrounded by an area of fortified walls and by two suburbs: the Lvov suburb and the Cracow suburb, also called the Glinski suburb. The Poles lived in the city and villages, along with Ruthenians, Armenians, Tatars, and Jews, who populated the northern part of the city. In accordance with the ordinance of February 22, 1803, the ranks of the itemized voters in the city were completed. At the head of the city stood the Mukhtar[7] (Consulas) and on its right was a small hamlet (a magistrate's quarters comprised of 4 Consuls) with 7 Judges, 12 Members, and 1 Record Keeper (Notras Intus Zuwitats), all of whom were elected annually. Aside from the terms of the elected officials, the citizens of the city were given the right to erect a municipal building, stores, baths and butcher shops, in accordance with the example of the other towns, on the basis of the Magdeburg Laws. It was for this reason that the city was first to run market fairs and days, bi-weekly, and twice annually to hold a full market fair. There were to be 4 fairs in the month of March, May, July and November, and market days bi-weekly on Thursdays and Saturdays. Separate detailed rules were documented separately, and the first Mukhtar elected was Paul Szczeneszlivi.

Despite the fact that the city suffered from a variety of invasions in its first years, it was developed and buildings were erected. The number of working people grew, and their unions followed, extracting additional special privileges for its members. The area of the city broadened, roads were paved in the Lvov suburb and the Glinski [suburb] and were built with lights. Thanks to his military effort in the war against the Russians, and the deposition of the Czar, Szuisky[8] Zolkiewski lived with his central administration in

[Page 3]

Zolkiew, where he invited nobility, military officers and senior officials from all ends of Poland, to his house. He wrote his memoirs about the war in Russia, at his residence in Zolkiew.

Zolkiewski was concerned with all segments of the city's population. He granted them privileges and did all that was possible to provide for their religious and educational needs. Aside from Roman Catholic churches, he gave permission to the Ruthenian people to erect their own church, in a written order of June 21, 1612, and granted them privileges equivalent to the remaining citizenry. However, for political reasons, the Starosta[9] Sigmund Grabowski, forbade Ruthenians to stand for election as officials of the city, arguing that this was against the laws of the Church. The Ruthenian leadership presented themselves before Zolkiewski to remind him of the charter that gave them permission to erect their own church, and through which they were promised the right to vote in municipal elections. Zolkiewski ordered that this privilege be properly implemented.

It was not possible for Zolkiewski to think about further development of the city during the years 1618-1620 as he was occupied with leading armies in the war that broke out in those years. On October 7,1620, he was killed beside the shtetl of Cecora. The family demanded that his body be returned to them. They were asked for 3 million gulden to ransom the body. After the agreement was finally reached, he was buried in Zolkiew. Jan Danielewicz, the husband of his daughter Sophia,[10] inherited the city of Zolkiew and its possessions.

The Tatars invaded Reisen again in 1620 and also besieged Zolkiew. Thanks to the effort of Stupnitski, the leader of the palace who threw down many barrels of angered bees onto the camp of the invaders, the Tatars fled, past the gates of the city. For this act, Stupnitski received the gift of Mokrotyn, a part of the town, from Danielewicz. In the years 1625-1627 many houses were built and streets along the roads were widened. A hospital was erected in the direction of Lvov, using monies that were set apart by Sophia, who had come to live there after she married in 1605. Sophia , who was the second wife, devoted her assets and possessions to caring for the needy.

The economic circumstances of the city improved during this period, and it became a center of commerce. Almazy Jurkewic, a senior among the gentile wholesalers, brought merchandise to sell from Poznan to Zolkiew. Jurkewic died in transit during one of his trips in 1630. There were many people who were engaged in beer brewing, and the local beer was known for its excellent taste. Sophia Danielewicz, who was known as a very religious Catholic, looked after the churches, donated large sums of money to monasteries, and set up institutions to collect funds for the churches. In addition, work on fortifying the city was finished and streets were paved. In the year 1632 she turned over the management of these municipal matters to her son-in-law Jakob Sobieski, who supported the workers, and left behind a written privilege dated March 8, 1632, to the various unions of lumbermen, carpenters, hat makers, glaziers, and wagon-drivers (who were able to create wheels out of wood). Along with this, Sophia continued her management of municipal affairs, and remained involved in the issues that interested her. She offered her views and made sure that the municipal leadership carried them out; especially that the city and her friends would deal honestly with the residents of the city.

[Page 4]

Sophia died in August 1634. Her son, Stanislaw Danielewicz, controlled the city for only three years. He lost to the Tatars and died a captive in 1637. At that time, the assets of the city passed to his brother-in-law, Jakob Sobieski, who had also inherited a market and the city of Zolocow and its possessions, from his father. Sobieski worked to preserve the assets of two cities. He built pools and conducted a successful fish business. In his concern for security, he oversaw the improvement of the roads and fortifications, involving the townsfolk in this work. It was not only the wars that befell Poland in these years, but also Cossack rebellions in the Ukraine, that were bound up with the events of (1648-1649). Jakob Sobieski, who was known as a fiery speaker, stood guard over the privileges that had been granted to the city and its residents, and managed the preservation of municipal elections, and the selection of commissioners when necessary. In 1639, the Tatars, once again, fell upon the city environs of Zolkiew. They plundered the area for sheep and took a number of farmers into captivity, but the city itself did not suffer.

There was an increase in commerce and work available in Zolkiew during the time of the reign of Sobieski. In addition to the existing unions, the following groups were organized in 1642: saddle makers, blacksmiths, weapons & arms, coal products, side products from the saddle work, locksmiths and jewelry, and a pharmacy. Workers were obligated to pay a fee to the masters of the city in accordance with their earnings, especially butchers, who increased their income from the sale of cow's milk. Jakob Sobieski died in 1646, and his wife Theophilia gained control of the city.

And here, touching on everything, came the Chmielnicki storm, which laid siege to the city in 1648.[11] The heads of the city offered ‘redemption money’ of 22,000 Gulden to Chmielnicki, who then left Zolkiew and went to Zamosc. In 1649 the matriarch of the city invited the founder of the Dominicans to settle in the city, and allocated land to them to build a church and a monastery. She donated 50,000 gulden for this purpose, which was a significant amount of money. Through this, she memorialized the memory of her son Mark, who fell in battle against Bogdan Chmielnicki beside Batow, on June 2, 1652 when he was 24 years old.

The Cossacks invaded Zolkiew on September 26, 1655. Many citizens of the city, including Soamnon, showed the Cossacks where to find the stores and warehouses in the city. The Cossacks plundered the facilities that were used to distill beer and mead. The invasive battles that struck the city greatly impacted the life of the city and its economy.

Theophilia Sobieska died in the year 1661 and the city then passed as an inheritance to her son, Jan Sobieski who had been selected in the year 1674 to be King of Poland. During his reign, the city, in which he resided, prospered due to his devoted affection, as he managed its development and expansion. And it was indeed, because of his efforts, the city developed economically. In the year 1665 the city was attacked by the

[Page 5]

Hetman[12] Juzhi Lobomirski. Sobieski pursued Lobomirski and plundered his castle and assets. As a reward for this act of plunder, Sobieski was appointed as a Hetman in the year 1666. The city also suffered in the times of the wars against Turkey.

Ulrich of Vradom, who visited Poland in the years between 1670-1672, wrote as follows in his book of adventures about Zolkiew:

“We reached Zolkova by way of the swamps, on December 5, 1670, during the late hours. This is a city whose buildings included a palace surrounded by thick walls of indescribable height. In its outer midst were wooden houses. The great Hetman Sobieski received this settlement as an inheritances from his mother of the Zholkiawski[13] family. She erected a Dominican monastery here, and a beautiful church. Within the walls of the palace, there is a Catholic Church built from magnificent stone. Apart from this, there were 3 other non-Uniate churches, and the synagogue of the Jews, who were to be found in significant numbers. The deputy Starosta[14] Kaminski received us in a gracious manner.”

In 1675, the Turks invaded the city, but they retreated after the Polish victory beside Socawa.

On May 20, 1680, an officer was placed in charge of real estate in the city, and by his order 271 houses were built, of which 183 were owned by Christians, and 88 belonged to the Jews. After the war with the Turks, Sobieski allowed the monks of the Dominican monastery, whose residence was in Kamienec-Podolski, to settle in Zolkiew after the capture of that city by the Turks. At the same time, the monastery of the Ruthenian Basilisks[15] moved here, and the city became a substantial center for the Christian faith.

Sobieski's great victory over the Turks at the gates of Vienna in 1683 saved Europe from capture by the Turks. After this victory Sobieski remained in Zolkiew where he concentrated on resolving issues and creating order. One item was the matter of the privileges of the unions of shoemakers and lumber men. In 1687, a new municipal building was erected in which members of the city occupied space until 1832. Since the city faced difficult economic circumstances because of the wars and the Great Fire of 1691 that destroyed its suburbs, Sobieski bore the burden for eight years, to pay the taxes on drinks (Czafawa) and window taxes (Fadimneh) for those parts of the city that were burned. On March 11, 1693, Sobieski issued a new set of orders, in which he allocated all of the privileges that the city had enjoyed up to this point.

[Page 6]

It was set out in this ordnance that of the 4 heads of the city (Burmistrz[16]) there will be 3 Catholics and one Greek Orthodox member, and among the six judges (Lawnici) – there will be 5 Catholics and one Greek Orthodox. The Jews were permitted to pick their own leadership.

In the processes that were set up to collect taxes from the houses, houses close to the palace were levied with a tax of 1 gulden and 5 groschen, and for the rest and the houses on the Jewish street: 18 groschen. Houses in the center were charged 1 gulden and 5 groschen, and those in the outskirts – 18 groschen. As to the outskirts of Lvov and Cracow, 18 groschen for houses in the center, and 13 groschen for houses to the rear. The collection of royal and municipal taxes was allocated to a special committee, made up of 12 members of the city in authority – 2 men with authority from each labor union, and also 2 representatives of the Jewish community.

After the death of King Sobieski on June 17, 1696, the city was transferred to the rule of his young son, Constantine.

Zolkiew was subjected to the full assault of the plundering Swedes, the Cossacks, and the Russians at the start of the 18th century. In the year 1701, the Russian Czar Pyotr Alexeyevich reached Zolkiew, and praised Poland widely, in order to compel the union of Poland and Russia, and to persuade the Swedish King Charles XII, to sue for peace. It was expected that foreign armies levied taxes, confiscated foodstuffs and merchandise, but thanks to the efforts of Constantine, life in the city returned to its normal state. After his death on April 4, 1726, his wife erected a hospital, lowered the level of taxation and turned her attention to the care of the religious institutions.

The rule of Zolkiew changed over to the hands of Constantine's eldest brother, Jakob Sobieski, in 1728. During Jakob's reign, the city suffered from the invasion of foreign armies, especially from Russia. These invasions cost the city dearly in precious blood. Jakob Sobieski was not an administrator. He did not bother with [the city's] development, and he gave over the management of the affairs of the city to his appointed officials. After his death (12/19/1737) the city passed into the hands of his daughter Maria Karolina de Boullion. She sold all of her possessions as of March 11, 1740, after just 3 years, including Zolkiew, 10 towns (Kulikovo, Varitzow, Zarurdiza[17], Zaborow, Czostków, Zloczów, Sasow, Marcopola, and Ziarna Pomorzany[18]) and 140 villages, to the Duke Mikhail Kazimiersz Radziwill, who was called ‘Pani Ribenky.’

In turn, Radziwill relinquished the management of the affairs in Zolkiew to his Starosta, Mayor Czyczynski. Because of the debts that fell upon him from Jakob Sobieski, the Voievode[19] of Sandomierz, Jan Tarlow, seized Zolkiew as well, and it was returned to the Radziwill family only after trials and a ruling from the tribunal court. But the city remained in her hands only up to the year 1787 when Karol Radziwill died, and all of his possessions were sold.

[Page 7]

During this period, a visible development took place in the economic life of Zolkiew, especially in the city's manufacture of linens and leather, the quality of which was noteworthy in all parts of Poland. A Russian army took up residence in the city in the 1760's, but it departed in 1767.

A plague broke out from July 4 to August 10 during the summer of 1770, causing chaos in the city, and claiming the lives of 57 Christians, and 98 Jews. Dr. De Lakazow and a number of medics were specially dispatched from Warsaw to Zolkiew to assist. The majority of the residents of the city fled to the fields and forests. Their condition in the forests was severe, particularly because they lacked food. Dead bodies lay on the road because there were no grave diggers, and added to this, was the fact that the summer stretched into the month of November. It was very hot and hundreds of people died. It was only in the winter that people began to return to the city.

In the meantime, compelling political changes occurred in Poland. The First Partition[20] took place in 1772, and Reisen and Little Poland fell to the partition of Austria. An Austrian army entered Zolkiew in October of the same year. The Laws of Magdeburg were annulled, and the city was pronounced a city of the district. Franz Gering was appointed the Senior Officer (Becirks-Hetman) of the district by the Austrian rulers. According to the directions by the gubernium[21] (the country's rulers) given in Lvov on November 18, 1773, the citizenry was ordered to arrange for a ceremony to swear their loyalty to the King in accordance with the ranks of: clergy, nobility, etc. and the same for the inhabitants of cities, towns and villages, and the Jewish communities.

This ceremony to swear allegiance to the King took place in Zolkiew on December 29, 1773. The appointed officers, and especially the District Officer, were not well-received due to the skeptical and humorous reaction by the people. This was not a surprise as the original foundation of these new people in Zolkiew was tainted by corruption, bribery, perfidy, and thievery. Most of them had come to Galicia in the hopes of finding an ‘El Dorado’ to get rich and enjoy life. From the perspective of the Poles, they were worse than the Tatars, at least according to documentation prepared by the Polish poet Francziszek Karpinski.

The authorities took away the pharmacy from the Dominicans, who had been granted the responsibility for it since the 17th century, and turned it over to a secular pharmacist on March 23, 1798.

The first of the basic schools were established in Zolkiew in 1785. In 1787, the town was awarded the role of judging and ruling on criminal cases. In that same year, the monasteries were closed. A military hospital was set up in the Dominican monastery, the castle was sold to the Radziwill family, to Adam Juzpalewitz. They built three wings to a high standard, and rented the property out for offices and dwellings. Juzpalewitz himself settled down in part of the castle, which contained the rooms of the King Sobieski.

[Page 8]

The Austrian rulers did not consider Zolkiew to be much of a city. To the Austrians, only the cities of Lvov, Jarostaw, Prszemsyl, Sambor, Drohowitz, Brody, Tarnopol, Zamosc, Zaborow, Buczacz, Tarnow, Biala, and Podgórze were considered worthy of the designation as a city.

Because of wars and invasions and assaults that took place in the first half of the 18th century Zolkiew was very run down. Baltazar Hecht, a professor at the university of Lvov, who toured all the parts of Galicia at the beginning of the Austrian capture wrote: “Zolkiew, the place which had been a seat of the kingdom in the past, still exists, but it is greatly deteriorated and and the palace is close to crumbling. In comparison to the villages of the mid-size cities like Biala, Krasnow, Podgórze, Sambor, Drohowitz, and Stary, whose leadership was knowledgeable and in good order, the running of Zolkiew did not enter their minds, because the head of the city and members of the municipal council were not equipped to manage the issues of the city, and there were amongst them, those who did not know how to read and write.”

Like the rest of the Galician villages, Zolkiew was burdened with considerable difficulties during the first years of the Austrian administration, particularly with regard to the amount of taxes owed to the Austrian treasury, especially for fields. There were also, for example, 8 types of taxes that were levied on houses – 4 Kreuzer to 5 Gulden. And there were ruined houses in the city whose worth was less than the taxes they owed.

At the beginning of the 19th century, as economic conditions in the city improved with new businesses, there were more jobs for workers. For example, there was a factory for home modeling, whose requirements rose from year-to-year, reaching 250 packs of woven goods, and 50 packs of mesh. In Hocyskan, in the district of Zolkiew, there was also a paper factory. Leather goods work increased, and in the center of the city, Glinski, there was a clay factory that produced beautiful and expensive vessels. The owner of this operation, Nikrowic, employed more than 300 workers, and the returns on the output rose to 30,000 Gulden.

A plantation farm, ‘Rhimbarbarum[22]’ was established through the efforts of the residents in 1785, in Mokrotyn, which was close to Zolkiew. By 1792 they had grown 36,000 plants, whose roots were sent to Vienna to examine their effectiveness for medical purposes.

In the year 1808 there were 2,166 residents in Zolkiew.

The Polish army invaded Zolkiew in 1809, headed by the nobleman Jozef Poniatowski. A government was established under the aegis of Wincenty Rolokowski and a Polish battalion took up residence in the town. On August 18, Zolkiew celebrated the birthday of Napoleon. The streets were decorated for this event, and many Poles from the surrounding area came to the city. Invited guests participated in a celebration in the evening, and the streets were filled with parties of the common people.

There were no special changes in the life of the city during the early years of the 19th century. A devastating fire broke out in 1838 that burned down many houses, the synagogue, other houses of worship, and churches. These buildings were completely consumed. The Basilian Dominican monastery was destroyed along with its large library. Money was collected all across Galicia to help those who suffered from the damages.

[Page 9]

In 1848, the citizenry was aroused to active community service, to the Viennese Parliament, that was elected that year. The Ruthenian farmer, Kozar Pankov, was elected from Zolkiew. In August 1848 there were assaults on the members of the Starostvo, but nobody was hurt.

Baron Krieg served as the District Officer during the 1840s. He did a lot to develop the city, including erecting a general hospital in 1844.

Two copper coffins were discovered in the Church, during routine maintenance, in 1861. Later, it was found out that these were the coffins of the Sobieski sons, Jakob and Constantine. On June 16, a funeral was conducted, and the Polish nationalists in the city that caused this were crucified for the way they handled the interment. Hundreds of Poles came from Lvov and its environs to participate in the funeral.

During this period, the district office (Becirks-Hauptmanschaft) the Office of Taxation, the Post Office, and the Educational Advisory Committee were located in Zolkiew, all of which were under the supervision of the Head of the City. Deputies, and the Municipal Committee which, according to a law promulgated in 1874, consisted of 30 members, of which 12 were Poles, 3 Spiritual people, and 12 Jews. The District Education Committee (Powiatawa Rada Szkolna) was led by the chairman and his deputy, overseeing the schools and had 6 members. In addition, there was a District Advisory Committee (Rada Powiatawa) consisting of 26 members. Ten members were property owners, 4 were from cities of the district, and 12 were from the villages. The Advisory Committee was led by a Chairman, his deputy, and six members.

There was a school for boys and a school for girls in the city, with different curricula and activities for each. In 1876, the following were elected: 13 Smiths, 3 Locksmiths, 1 plumber, 2 watchmakers, 3 Upholsterers, 5 Carpenters, 1 Pipefitter, 5 Carvers, 58 Shoemakers, 29 Tailors, 5 Bookbinders, 3 Wagon Drivers, 11 Fence Makers, 2 Weavers, 4 Arch Makers, 21 Bakers, 1 Dyer, 2 Woodcutters, 1 Hatmaker, 2 Hairdressers, 2 Soap Makers, 3 Tanners, 2 Builders, and 2 Window Washers.

In 1850 there were 570 houses in Zolkiew, and 5,500 residents, of whom 2,000 were Jewish. In the election of 1880; 6,794 residents were counted in Zolkiew. The Poles numbered 1,866 individuals (24.5%), 1,145 (16.9%) were Ruthenians, 3,757 were Jews (55.3%), and 26 Other (0.3%).

In 1890, Zolkiew had 7,143 residents. Poles numbered 1,430 (20%), 1,919 (26.9%) Ruthenians, 3,873 (53%) Jews, and 49 Other (0.4%).

In the year 1900, there were 8,966 residents. Two-thousand-two-hundred-twelve were Polish (24.7%), 2,697 (30.1%) Ruthenian, 4,008 (44.7%) Jews, and 49 (0.4%) Other.

In 1910 there were 9,463 residents of whom 2570 (27.2%) were Polish, 3,013 (31.8%) Ruthenian, 3,845 (40.6%) 3,845 (40.6%) Jews, and 35 (0.4%) Other.

A standing headstone dating from 1640 in the Jewish cemetery in the village of Vynnyky that was discovered in 1939, proves that a Jewish settlement existed there even before the name of the village was changed to the city of Zolkiew.

The Jewish settlement spread and grew in tandem with the growth of Zolkiew. Most of the Jews came from neighboring Lvov, and accordingly, they were tied to the Lvov congregation.

Stanislaw Zolkiewski, the Hetman of Zolkiew, wanted Jewish residents to settle and remain in his new city. In order to increase the Jewish populace, he invited the Jews to settle in Zolkiew and to erect a synagogue. He designated a special plot for houses beside the city wall that became called the street of the Jews (Ulica Żhidowska) [23]. The Jews were granted permission to also build houses and wells, buildings for cooking for distilling beer and mead, and a bath house, on this street. However because of the absence of a cemetery, they were forced to continue burying their dead in Lvov.

The growth of the Jewish settlement of Zolkiewski was aided by the effort of Israel ben Joseph who was called Eideles, the owner of the property in Zlotow, and the son-in-law of Rabbi R' Yehoshua Falk (the owner of the חסמ”א. When Zolkiewski erected his city in 1600, he responded favorably to the request of Israel Eideles to permit Jews from overcrowded Jewish neighborhoods in Lvov, to settle in Zolkiew. Many Jews took advantage of this opportunity and left Lvov to settle in the new city.

Zolkiewski provided a written ordinance to the Jews on June 11, 1615, in accordance with his verbal promise, and permitted them to build a synagogue and mikva[24], and he permitted an edge of this property to be used as a cemetery. In a similar manner, he promised them comparable treatment in business with Christians, and permitted them to have a separate judge to deal with their issues, with the privilege of appeal to the rulers of the city. Over the course of 20 years, they were responsible to pay 2 Gulden, as well as all other payments made by Christian residents.

As previously stated, from the beginning of Jewish settlement in Zolkiew, the community was strongly connected to the congregation in Lvov. However, in 5380 (1619) it was reorganized as an independent community on the basis of limited autonomy granted by the Lvov congregation. It was especially limited

[Page 11]

in the matter of allocating parcels to newly arrived Jews, and for each and every instance, the Zolkiew community was obliged to inform the Lvov congregation, and get its permission.

The relaxation of the management of the city resulted in a large stream of Jews to come to Zolkiew, especially from Lvov. This did not sit as well with his wife, Regina Zolkiewska, who offered strong support to the Jesuits. In the year 1618, Zolkiewski was appointed a ‘Hetman of the Kingdom’ (Wilka Korona) and he disappeared for months and years from Zolkiew. In those instances, his wife ran the city.

On October 8, 1619, Regina made clear her intention to limit the extent of Jewish settlement. She levied a payment of 50 Grezhbini for the construction of the municipal walls, and 6 Groschen on every well, for all the Jews who came from the outside and who wanted to settle in Zolkiew. In addition to these payments, the Jews were also made responsible to carry the debt of the general citizenry. In accordance with a proclamation, it was forbidden for Jews to buy or borrow from Christian homes. The Jewish butchers were burdened to provision the castle with 8 ‘stones’ of milk.

As previously indicated, the Jews were concentrated in a particular neighborhood of their own, and they even had their own special gate (Brama Żhidowska). It is interesting that in that same year (1619), it became difficult for Jews in Zolkiew to obtain an occupancy license, even from the heads of the community, who promulgated the following on 11 Tammuz (12 Jul 1620):

‘It has been agreed in our community יצ”ו with the knowledge and concurrence of the important people of the community, that no person in this world will receive entry permission [to the city] for a generation except under the condition that he commit himself to give all immigrants, and all the head taxes that are due to him, and also forgive old debts of those people who reside in our community יצ”ו without any divisions in the world even if he is given a lead of thirty days from the day of his arrival. And all members of our community that will object to this will be fined ten red Gulden.[25]’

The community in Lvov decided that starting from 1624 on, the head of the community in Zolkiew will be forbidden to decide on [the amount of] new taxes. Additionally the amount owed on older debts was not waived. In the year 1614 R' Aharon ben R' Moshe (who died on 7 Kislev 5386 (06 Dec 1625) with the consent of the ‘leaders’ and ‘distinguished ones’ decided upon the amount of the taxes and fines, and all these sums were given over for expenditures needed for all undertakings.” The Shammes[26] was put forward as the head of this endeavor and was given the responsibility to deal with matters of taxation. R' Aharon personally assumed responsibility to turn over all amounts within the 14 days after the first of the month, either in cash or a secured lease, or the amount of money he had to take out of his own pocket. R' Aharon ben R' Moshe, who was among the most trusted of the business people, also gave a Torah scroll to the synagogue, with the condition that if a synagogue was built to the specification of synagogues in other towns, it [i.e. the Torah] will remain there perpetually; but if he moved away to another location before a synagogue is built, he has the right to reclaim his Torah scroll.

[Page 12]

The first Rabbi in a Zolkiew congregation was appointed in 1626. R' Yekhezkiel Issachar, son of Hanoch Avraham, served as the Rabbi until 1637. He also was the head of a newly established legal court. The heads of the congregation announced a special decision on 27 Sivan 5386 (July 21, 1626), to levy a fine of fifty red Gulden[27] – half of it for building a synagogue in Lvov, and the other half to build one in Zolkiew. This was because no member of the congregation, not the plaintiff nor the defendant, had permission to ever enter the Great Synagogue in Lvov. Only demands of more than 100 gulden were within the jurisdiction of the court in Lvov. In the founding year of the of the congregation, it transferred funds that were raised by the well-to-do of the Zolkiew congregation by the following named individuals: Aharon Zelig ben Moshe, Avaraham br' Shmuel Margalit, and Israel ben Yehuda Katz[28], to Regina Zolkiewka, the owner of the city. The amount the congregation needed to raise was decided by the national committee.

On October 7, 1620, Zolkiewski fell as a battle casualty against the Turks. His son-in-law Stanislaw Danielewicz, inherited the city of Zolkiew. Stanlislaw was the Voievode of Ruthenia, and married to Zlokiewski's daughter Zofia, who practically managed the city while her husband watched over the city of Olesko. After Regina Zolkiewka's death in 1634, as mentioned above, the control of the city went over to the hands of her son, Stanislaw Danielewicz, who during his short reign (1634-1637) granted the Jews in Zolkiew on June 18, 1635, a privilege in which he allowed all of the privileges granted to them by previous rulers, and broadened them in a number of easements, such as the right own homes, land parcels, vineyards and fields. However, he forbade the acquisition of new houses without the permission of the palace. And in instances where this prohibition was violated, the house would be confiscated.

This privilege also granted permission to the Jews to build a new synagogue. In an official document, Danielewicz advised that in accordance with the request of the heads of the community, ‘citizens of the city of Zolkiew,’ he is giving ‘all privileges, permissions, purchases that are being granted, or were granted by the rulers of the city Zolkova that came before me, all decrees, privileges, documents, purchases, are being granted because they were given on part or as a whole, and therefore all of the freedoms that were given to them by the city of Zolkova, I give I allow and hold them, and will look out to assure they are not violated.’ All the houses, land properties, vineyards and orchards that the Jews obtained to date, are still valid, and we behave according to their dictates, and they remain in their hands now, and rescued people. However, in the future without the express permission, they shall not buy any house in the city from Christians, and they are prohibited to spread out in the direction of the palace. The buyer will lose the house that he bought. It is permissible for Jews, with previously granted permission, to erect a new synagogue in the same place on a foundation of wood or stone, as they desire, and to decorate its interior in accordance with their customs. He and those that follow after him shall not disturb them in this process, except that centrally, in front of the synagogue, a separate house is required to hide it from the street.

This legal document laid down the basic law to increase and enable the Jewish population in Zolkiew, and provided for the possibility to expand the boundaries of those in it, even without the intention of the palace.

In 1628, the Jews owned 21 houses. Thirteen of them were on ul. Blozka, 4 near Skalca, and 4 in the remaining streets. But not one of them was in the center of the city (Rynek.)

[Page 13]

An increasing number of Jews bought homes in Zolkiew after 1635. The congestion of the Jewish section of Lvov, and the limits on space as a result, forced many Jews to uproot themselves from Lvov and move to nearby Zolkiew, particularly after the great conflagration of January 14, 1645 when Chmielnicki laid siege to Lvov and burned down many Jewish houses. The price of houses was between 400-600 Gulden, and of vineyards, 500-700 Gulden depending on the location and timing. The number of houses obtained by Jews grew at such a pace that in September 1664, Jan Sobieski and rulers of the city publicized an explicit directive that no Jew may obtain ownership by purchasing from a Christian without the consent of the palace.

Despite this, Jews succeeded in getting permits from the palace authorities, and they bought houses within the city. Yaakov Bezalel bought a house at a price of 1,800 Gulden at the Rynek, Number 17. According to local sources, he received this house that his neighbors called, ‘The House of the Authorities’, (Kamienica Krolewska) as a gift from Sobieski. At the center of the city, at Number 10, the printer Uri Favus HaLevi[29] also bought a house built in English Renaissance style, for his printing location.

In 1680 there were 88 Jewish houses. In 1765 the number of houses in Jewish hands numbered 270, with 159 in the city-center, 81 in a Lvov suburb, and 20 in a Cracow suburb where 1,500 people lived. In the year 1788, the Austrian authorities established that the homes in the center of the city were owned by Jews.

According to municipal law, and the same in the documents of record, the homeowners were responsible for paying all the municipal and country-level taxes placed on the houses, depending on their location. Like all other cities, Zolkiew had a number of Jewish homes, synagogues, a hospital, and a Rabbi's manse. The prosecutor and the doctor were released from the obligation of paying taxes for the good of the city.

From the time of the establishment of the city, and through the 17th century, there were good relations between the Jews and non-Jewish people: the Poles, Ruthenians and Armenians. Jews also lived outside of the Jewish street, and the opposite as well, there were non-Jews who lived on the Jewish street. During this period, there doesn't seem to have been conflict between Jews and non-Jews, not even with regard to commercial competition. Also, the relationships of the city authorities and the government and the palace towards the Jews was normal.

In 1634, a Jewish man, Hertz Potlicki, bought a house without notifying the authorities or the palace, and did not obtain any form of consent. The city ruler, Zofia Danielewicz, merely gave a direction in writing, to list the house in the folio of possessions, after he paid her a fine.

In 1649, a Christian man, Jan Tkacz killed a Jew. After the court carried out an investigation which included torture, it issued a death sentence to be carried out in the Cracow suburb. Apart from the murder itself, no further incidents are known, but matters changed in the 18th century.

[Page 14]

From an economic standpoint, the city of Zolkiew had an advantage due to its geographic location. In Lvov, a conquest was underway on the northwestern side through Kulikovo – Zolkiew, Rawa Ruska, Lubicza on to, Zamość, and from there, by way of Tarnogura[30] to Krasnistaw and Piaski to Lublin, which in those days was one of the unique centers of commerce in Poland. This road made it possible for the Jews of Zolkiew to take part in commerce with the north, as they traveled to Danzig and brought back Polish merchandise to sell locally. There were also a small number of Jewish businessmen who had connections with their counterparts in Breslau, Frankfurt-am-Oder, and Koenigsberg. From the list of attendees at the fairs in Leipzig in the years 1681-1699, we are aware of only one Jew from Zolkiew: Joseph Borowowitz. The fairs in Breslau were visited by Yaakov Lazarus, and Nathan Moshe. In the period 1693-1696, Matityahu (Mattes) Freiling also attended.

In the year 1722 there is no record in the visitor's list of names of Jews from Zolkiew to Breslau fairs.

And yet, in 1722 the names of Fishl Leib, Nathan Leib'l, and Shimon Leib'l appear.

In 1725 Fishl Leib'l and Hesh'l Shmuel came again, visitors from Zolkiew told that the number grew because of the year 1692 by a noticeable amount at the beginning of the 18th century.

Yet the city of Zolkiew was bound to Lvov, and was forced to buy their Etrogim[31] in Lvov. And under threat of punishment of the confiscation of their whiskey, they had to sell whiskey to the Christians, and deal only with Jews in Lvov.

Except for local commerce and external commerce, the Jews were engaged in the distillation of beer and mead. Jews also were present in significant numbers among the crafts of tailors, furriers, hat makers, and jewelers of gold- decorated items.

A short time after the establishment of the Jewish settlement in Zolkiew, the Jews approached the task of erecting a synagogue. They had already received permission to do this back in 1600 from Stanislaw Zolkiewski. In 1624 a House of Prayer was created in the house of Aharon ben R' Moshe in accordance with the agreement that was signed between the Bet-Din Senior[32] and the heads of the Lvov congregation, on 4 Nissan 5384 (5 Apr 1624), ‘which committed itself with full responsibility that the upper floor of the building will become the synagogue permanently, and takes on the responsibility to immediately and without delay, to install and activate an oven, and also assumes responsibility to make the windows in accordance with those of Avraham

[Page 15]

Hittelmakher[33]. In the event of delay of any sorts, they must place the bottom floor – and no prevailing advantage is ever to fall on Mr. Aharon, based on some man from Zolkiew claiming a preference that the synagogue is in his house.’ And if he wishes to uproot his family from Zolkiew or wishes to sell his house, the congregation is obligated to give him 600 Gulden for the house and no more.

There were minor disputes that were settled regarding the windows. Aharon ben Moshe and his wife assumed responsibility for documentation of those who contributed to the upper part of the building, and the walking by people in his house explicitly well-explained as to which person it is due and proper.

After his death on 7 Kislev 5385 (18 Nov 1624) the congregation bought the house and all of its boundaries from his son and heir Benjamin Moshe.

With the growth of the settlement, the synagogue was no longer sufficient in size, and in 1627 the Jews made a request to the city ruler, Stanislaw Zolkiewicz, to allow them to build a new synagogue. Their request was granted in a written ordinance on the date of June 18, 1635. But even without this permission, the Jews of Zolkiew did not manage to raise a new synagogue until the end of the 17th century, after new additional permissions were granted which they received from Jan Sobieski on December 12, 1664, 1678, and 1687.

Nevertheless, a rumor was spread that Jan Sobieski erected the glorious synagogue as a recognition of thanks to his Jewish doctor, Dr. Simcha Menachem da Jonah, for curing him of an illness. In fact, the King donated construction materials, wood and stones, to the congregation.

According to Polish law, the Church also had to grant permission to the Jews to build a new synagogue. On March 22, 1662, the community received permission from the Archbishop of Lvov, Constantine Lipsky, who said, that in accordance with the wishes of the King, it is permissible to erect a synagogue built of stone on the old parcel on which the (older) synagogue was built of wood. The construction lasted many years. One of the amendments found in the folio said: ‘since this work will require a great deal of preparation, lasting more than a few days, it was worth five hundred Polish Gulden, every year, it is not needed for the preparations to put up an advance for the building that they planned and brought for the purpose of the construction.’ The synagogue built in the Polish renaissance style, in the form of a fort with a protective roof, and the entrance way inside is supported by gilded pillars, it was built in 1690-1691. Symbols of Poland and the insignias of the ruling House of Sobieski were placed inside the building.

At first the Jews in the settlement brought their dead to be buried in the Lvov cemetery. Through a written ordinance, Stanislaw Zolkiewski promised that a field would be allocated for use as a Jewish cemetery. However, already since 1610, Jews buried the dead in the cemetery that existed before the city of Vynnyky was founded, as was learned from a headstone that was erected before 1640. Stanislaw Danielewicz provided formal authorization to the Jews to maintain a cemetery. This permission was also formalized in the written ordinance that was granted to them by King Sobieski in 1678.

[Page 16]

Before 1656 Matiasz Skiwicki sold his field along the cemetery to the congregation for 700 Gulden. Skivici's heirs, his sister Anna, and afterwards, her son Lukasz, argued that the congregation still owed them the full amount because of an easement for which there was no proof. A fire in Zolkiew had destroyed the city's record books. However, the congregation had two receipts. One was from Matiasz dated 1696, and another dated 1718, from Anna Skiwicki. After court sessions in 1730, a compromise agreement was reached, according to which the congregation paid Lukasz Skiwici 18 Gulden, and he dropped all of his other demands. The congregation was cut off from the legal ownership of the field.

With the passing of years, the cemetery expanded substantially by purchasing inherited parcels of land adjacent to it. From the outset, the cemetery was surrounded by a wall.

As previously mentioned, after the death of Stanislaw Danielewicz in 1637, his sister Theophilia's husband, Jakob Sobieski, the Voievode (district) of Belz and the Castellan[34] of Cracow, managed the affairs of the city in the name of his wife, until his death in 1646. During his rule, there were no compelling changes in the lives of the Jews. One characteristic episode casts a ray of light on the Jewish way of life in this period.

A hardship for the Jews was promulgated into law in 1641. Zolkiew was then owned by the Voievode of Ruthenia, Jakob Sobieski (the father of the King Jan Sobieski III), who was noted for being an intelligent man. This law went against the explicit directions he set.

Gamba (Fawa), a Jewish man, retained a young Christian girl named Maruszka as his servant. In the course of time he fell in love with her, and lived an intimate life with her from Passover to July. When she became pregnant with his child she did not tell Gamba, but quite the opposite. Maruszka hid her pregnancy until the baby was born. The baby was stillborn, and she fell under suspicion of having killed him. However, in the absence of six witnesses, as required under Magdeburg Law, she was obligated by a court of the Voievode Sobieski to swear that she did nothing to cause the death of the newborn and that she did not kill him.

On March 16, the Voievode Jakob Sobieski ruled that Maruszka had to submit to a public flogging by whip, in the city marketplace, and expulsion from the city.

Gamba, the Jewish man,denied the entire matter, but the court did not believe him. He was also sentenced to a flogging with whips in the marketplace of the city, then faced expulsion from the city and the confiscation of all of his possessions by the Elders.

[Page 17]

In order to prevent the occurrence of similar events, the city Elders ordered the prohibition of the hiring of Ruthenian servant girls under threat of expulsion from the city. Despite this, another similar incident occurred nine years later, in 1732.

After the death of Jakob Sobieski, his wife Theophilia took over the duties of ruling. Despite the fact that she was under the influence of the clergy and monasteries, her relations with the Jews were proper and just, as evidenced by her court decision in the matter of the murder of a Jew by the Christian, Jan Tkacz, who was sentenced to death. The period of her reign was a very difficult one, full of attacks and assaults for the many bloody years of Ta”Kh v'Ta”T.[35]

As to the fate of the Zolkiew community, Nathan Hannover, the author of ‘Yevayn Metzullah[36]’ wrote:

‘And they traveled from there (Lvov) and besieged the Sacred Congregation of Zolkova, and asked to approach the wall to put up ladders. They poured boiling water from the wall, and the invaders fled from them. And so they shot heavily at them through the episodes of fire, and killed many of them. And these invaders took counsel and they said: Would it not be better to send men to the city to try and appease them as we did with the sacred congregation of Lvov, the capital city? So they sent people to the men of the city and said to them: You are no better than those in Lvov who could not stand up against us and so they made a compromise with us. Accordingly it would be better for us to do the same with you. And if not, all of us will descend on you, and wreak the same havoc on you, and inflict our brand of justice on you, and inflict bizarre deaths on you. Just as we have done in the remaining settlements of yours. This appeared promising to the city Elders, that these invaders wanted to make a compromise with them. They sent a priest with one Jewish man from the land of Russia, from Chernigov, to arrange a compromise between them, and they settled for having the city residents give them twenty thousand gulden and six thousand for their senior commander, Glawacki, previously mentioned. They traveled from there and left behind several thousand Cossacks to guard the city from the rest of the Cossacks so they could not besiege the city even one more time. And all of the fortresses in Little Poland[37] Russia, Podolia and Lithuania did the same thing when they were besieged and pressured.’

And the author of ‘Mourning Poland’ wrote:

‘Waves of water will pour from my eyes for the rest of the Hebrews. How the dear scions of the holy congregation of Buska and the honest scions of the holy congregation of Berhyn, and the pure scions of the holy congregation of Zolkova suffered from the Cossacks.’

[Page 18]

R' Shmuel Fyvusz ben Nathan Fyvel conveys in the book ‘Tit HaYavan[38]’ where Chmielnicki ‘went to Zolkova and there, there were about three hundred balebatim[39] who gave a great sum of money to redeem their lives.’

On September 26, 1655, after seven years had passed, Chmielnicki made a second assault against Zolkiew, and this time he conquered it. A resident of the city, Syamyan, revealed to the Cossacks where the merchandise was hidden, and similarly pointed out the stores and homes of Christians and Jews that were plundered by the Cossacks, and the damage to goods was very substantial.

But it was rather during these days long before the Holocaust, that the Jewish settlement in the city grew, because Jews came there from Lvov after they lost their possessions as a result of the plunder and the redemption money they paid. After the year of Ta”Kh, the community grew to an extent that it had the nerve to free itself from the patronage of the mother-community in Lvov, and to fight for it in the provincial committee of Ruthenia. This condition improved after the death of Theophilia Sobieska (1661), whose estates were inherited by her son, Jan Sobieski in Olesko, Zolkiew and its possessions, its palaces.

The city developed while under the control of Jan Sobieski, and with it the Jewish community grew, both economically and politically, especially after Sobieski was crowned as King of Poland in 1674. Zolkiew went from being a provincial town to the level of a full city and a political center.

The Jews enjoyed the good feelings of Jan Sobieski and his support. From that time on, there was a royal standard (harazhny karanny) and afterwards that of Hetman-Starostvo Jaworow and the rulers of Olesko. The city of Zolkiew enhanced its closeness to the Jews, and also created closer ties to them. In serving as the Starosta in Jaworow, Sobieski helped the community and was personally supportive of creating a synagogue in the city. He valued the economic status of the Jews, and their importance to the improvement of its condition. There were many Jews in his courtyard in Zolkiew, who had a special and loyal relationship with Yaakov Bezalel ben Nathan, who was the designated administrator for customs. Yaakov Bezalel ben Nathan had settled in Zolkiew in 1685 and he managed the tax office in Lvov.

The towns and villages around Zolkiew and Lvov complained to the King through the Starosta, that the King was conducting an abusive relationship toward the Christians and the Warsaw Magistrate. The Starosta, even saw fit to convey these issues sternly, asking in the city of Lvov, because the issues in Poland had reached the state that ‘the Kingdom's taxes was turned over to a Jew and he assaults and oppresses Lvov merchants, something that is not possible in Warsaw.’

For this reason, the King was well-received by the Jews who saw him as a Patron. People told stories about his deeds and generosity. In September 1664, the King granted a privilege to the Jews in which he authorized all the ordinances that they had received from Stanislaw Danielewicz in the year 1635.

In the written ordinance that Sobieski granted to the city in the year 1678 regarding rules relating to commerce, he explicitly authorized the liberties and laws granted to the Jews by his predecessor, and referenced the previous ordinance of September 12, 1664. In addition, in his written ordinance of 1665, he specified the privilege in which he granted them permission to build a synagogue.

[Page 19]

After the Great Fire that occurred in Zolkiew in 1691, the King released the city from the onus of all taxes for eight years. Because all of the written ordinances of the city were incinerated, on March 11, 1693 the King authorized all of its privileges, and the relaxation of constraints in order to make it permissible for the Jews to participate in the elections of the monarchy, city heads and judges. Jews also enjoyed these privileges granted by similar ordinances, in cities such as Brody, Walichow and in the cities of Prince Radziwill of Lithuania. Prince Radziwill permitted the Jews to have a bath house of their own, and levied taxes against them for the expenses of the city watchmen who looked out for potential conflagrations. It is said there, that Jews who bought houses from Christians shall pay the same taxes as Christians. For setting taxes, the community shall designate two ‘heads’ to a second ratings-committee.

Once a year, the Jews were also given permission to send one or two empowered people to attend the sitting of the Municipal Council, in which an accounting was given on the municipal finances, since the Jews provided a fifth of the expenses disbursed. Jews were required to pay the produce tax (Czafawa) in accordance with older addenda. For purposes of setting the remaining government and municipal taxes, an office of twelve men, including two representatives from each labor union and two appointees of the community, were tasked with estimating the taxes honestly and with justice.

This ordinance, in fact laid the foundation for the life of the community and the Jewish community in Zolkiew. It authorized all previous privileges preceding it. In addition, it added a new item, authorizing Jews to participate in national and municipal elections by the participation of their officials named to the ratings-committee.

With this, the King carefully oversaw the inspection of the taxes paid by the Jews, and on July 27, 1693 he ordered the tax collectors to keep an eye on the Jews, where the élite covered them with their protection. The city suffered during this period, and the entire community of Jews suffered from conflagrations that broke out in the years 1645, 1657, 1691, and 1699, during which many of the homes of the Jews were burned down.

Dr. Menachem da Jonah, the King's royal physician, and the tax appraiser Yaakov ben Nathan took up residence in Zolkiew during the reign of King Sobieski and were active in the life of the community. Their services were recognized even before the establishment of the community on the basis of their recognized influence and contacts that caused them to be valued by the King.

Dr. Simcha Menachem Emmanuel, the son of the physician Yokhanan Baruch da Jonah, was a unique person. His father had settled in Lvov as a practicing physician. His mother Aksa, was a daughter of the doctor Menachem Tzunzfort of Lvov, who died in 1666. His brother Eliezer was also a specialist in Lvov, and he died on 28 Elul 5433 (1673). His brother Yaakov graduated from medical school in Padua in 1678, together with his friend Levi Lieberman Fortis from Lvov, who was the brother of Yitzhak Fortis (חז”ק)[40]. His brother Joseph was a merchant in Lvov and died in 1712. Their father, Dr. Yokhanan Baruch was among the élite of the Lvov community. He was an outstanding and wise man of whom it was said: ‘He had with him the Covenant of the Torah, and the Mitzvah.’ He died on 14 Nissan 5429.

[Page 20]

After Simcha Menachem completed his medical studies at Padua in 1664, he returned to Lvov where he worked as a physician and married Nessia bat R' Pesach. He was quickly recognized as one of the better doctors in the areas surrounding Lvov as well. In addition to his professional work, he dedicated some of his time to the issues of the Lvov community during the hard times after Ta”Kh.

King Sobieski was struck by a severe illness in 1670-1671, and invited Simcha Menachem to serve him and cure him, and requested that the doctor reside near him in Zolkiew. Simcha Menachem agreed to this request, and remained in Zolkiew until the King died on March 11, 1696. Afterwards, he returned to Lvov (Blakharska Street 19). While he was in Zolkiew, he took an active part in the life of the city, and was endeared to the Jewish populace. Even after his departure, the heads of the community turned to him for guidance.

Here, for example, is an incident that happened in 1701 when one of the citizens of the city shamed and accused the community of blasphemy, and Menachem was asked to get involved with the quarrel. In a letter to the congregation of 12 Kislev 5461 (1701), Menachem wrote that ‘he was beloved by all members of the community from the young to the old and that they listened to the speaking of the Rabbi Our Teacher and Rabbi R' Issachar Ber, Bet-Din Senior and a Teacher of Justice[41] in your congregation.’ Similarly: ‘It is certain that all of the spirits of the world will not dislodge the ruling of the Rabbi from its place. Should man intentionally accost another to alter this, it would be as if he were to alter the Divine Presence[42] itself.’ Menachem's letter made an impression on the congregation, and on the government council that dealt with such a matter. It issued a ruling, consenting to the words, of the ‘Honored and Glorified Great Rabbi, Our Teacher and Rabbi Issachar Ber, who was the Bet-Din Senior mentioned before, and the Officer and Leader, the Specialist physician Our Teacher and Rabbi Simcha נ”י[43]. When the writers observe a few people diluting and simplifying the words of the Sages of the Generation to incite anger, such that caused their hearts to leap into their mouths, and with all their might stood in this outburst with their hearts in their mouths, paving the road and blocking it with a gate, so that no one will not suffer any injury and not fall to the ground, even if it is most deficient of all amendments. And from this, the matter is closed and everything was in good taste and an understanding made in truth and honesty that is worthy of God and Man.’

Menachem was also respected for settling a dispute among the printers in Lublin and Cracow, and Uri Fyvusz from Amsterdam, after the last printing house was transferred to Zolkiew in 1690. Our issue was brought before the Va'ad Arba HaAratzot[44] in Jaroslaw that passed a special ordinance regarding this issue. Dr. Da Jonah was designated to inform us that ‘Uri Fyvusz will not print more than seven hundred copies in the holy congregation of Zolkiew, and a handwritten note should be entered in those copies as follows: the Rabbi ה”ה and the Bet Din Senior of Lvov. In addition, the following signatures will be required: the head officer and official and the wealthy man The Rabbi and Our Teacher and Rabbi Simcha son of Our Teacher and Rabbi Yokhanan נ”י, of the holy congregation of Lvov.’

[Page 21]

‘Reb Simcha Doktor’ – which is how the people referred to him – was accepted by all ranks of the populace, both Jews and Christians. He was a Torah Great, a master of the Haskalah[45] and a seeker of faithfulness, as was evidenced, among others reasons, by the fact that his house was built in Renaissance style. His generosity was especially appreciated, because he had an open hand for helping the poor and the indigent.

His first wife Nessia, died in 1693. After he returned from Zolkiew to Lvov in 1696, he married a second time but lived with his wife for only a few years, as he died on 28 Adar 5462 (1702).

Yaakov Bezalel ben Nathan, Sobieski's agent, was different from him. His origins are not known, but we know that his father was killed in the slaughters of Ta”Kh. He came to Zolkiew In 1685 and inherited the right of residence in the city. As far back as 1682, he bought a magnificent house in the middle of the city for 1800 Gulden from the jeweler Stanislaw Tumaszowitz. This took place after he had notified the heads of the community on 10 Tammuz 5445 that in his soul ‘he felt a need to be an equal as one of the community יצ”ו, and to assume the yoke of being one of the citizens יצ”ו’. The heads of the community reacted positively to his request. After some bargaining, they granted him and his progeny a franchise of residence in the community. He took the yoke of the community upon himself, ‘as payment for the obligation of the community from now and in the future along with sons and sons in-law and all other worldly gifts, that will be in his ambit יצ”ו.’ He personally nullified all of the personal privileges he had received from the King יר”ה[46], from the officers and commanders of the Four Lands, and the same from ‘the officers and commanders and leaders of the Galilee יצ”ו who oppose any amendments from the community.’ He was quickly acclimated into the community. On Hol HaMo'ed[47] of Passover in the year 5447 the Gabbaim[48] of the synagogue were elected. In the year 5449 the head of the community, designated that his son-in-law Hanoch, is entitled ‘to be head of the community and to occupy his seat and act like him in all matters.’ Only in instances where it was required to make a presentation to the King or officers would he personally organize the affairs of the community. He served as an agent for the King, Sobieski, and in this position, he reviewed the figures from the income of the tax offices in Ruthenia, Wolhyn and Podolia, and distributed the tax money to all the stations in the southeastern ambit of Poland. His official title was ‘The administrative agent bearing the authority of His Majesty.’

Thanks to his great influence in the King's courtyard, and not from a lack of effort, the privilege of building a new synagogue was attained in 1687, along with the consent of the Lvov Archbishop Lipski (1692).

[Page 22]

In the days of the war against the Turks and the Cossack invasion, Bezalel donated 400,000 Gulden for the needs of the kingdom. It was understood that a Jew at this level was an enemy to the Christians, who hurled insinuations and incitements against him. Rumors grew about him, that he was the enemy of Christians. Because of this, it was said that he cheapened the Christian faith and blasphemed against it. The towns in Lvov, Pozna[49], and Warsaw were incited against him, which further caused fabricated rumors that he was an enemy of the Christians. Representatives to the Sejm in Grodno in 1693 sat in judgment of his conduct and argued that he stole from the country's treasury and blasphemed against the Christian faith. An investigation committee was elected, but with the dissolution of the Sejm, the matter was removed from the order of the day.

We do not know if he was pushed out of his position and imprisoned. We know that he died in Zolkiew on 19 Tishri 5457 (1696).

The heir of the King, Jan Sobieski III – his son Constantine (1696-1726) his widow, Maria de Weisel (1726-1728) his firstborn son Jakob (1728-1737), and his daughter Maria Karolina de Bouillon (1737-1740) all authorized the ordinances of 1693.

In the final years of the reign of the house of Sobieski in Zolkiew, the Jews of the city were shaken by the tale of Jan Serafinowicz. According to sources from the Catholic Church, this convert was born on April 5, 1683 to his father Yaakov Shaul who was the Rabbi of Grodno. He himself served as the Rabbi in Slutsk and afterwards in Lithuanian Brisk. After he was struck by a great fear, and his sanity was compromised, his family brought him to Zolkiew to the Kabbalist and Miracle worker who tried to heal him. Because of these efforts, he was considered to be dangerous to those around him. He was put into chains and imprisoned in the cellar of a doctor's house. According to the stories of the Church, while In the cellar, he pondered about Christianity. One day when he prayed to Jesus about his fear, the door to his cell was opened, and he emerged from there healthy, faced straight toward the Church and converted to Christianity.

The legend ends here. But the truth was, that on April 25, 1710, a young Jew converted to Christianity under the aegis of Constantine Sobieski and Elizabeata Syaniowska, but it is not known whether this was Serafinowicz. In general, it is difficult to establish if Serafinovicz was a real historical figure. Despite the efforts of the Jews of Sandomierz, where the Church stories were involved, he did not present himself for a ‘discussion’ of anti-Talmudic theses or address complaints that the Jews had a need for Christian blood. He was seen in Warsaw at the palace of Syaniowska on May 22, 1712, and from then on any trace of him vanished and was lost. It is also possible that this never happened at all.

With the sale of Zolkiew on the 11th of March 1740, to the prince Casimir Radziwil, a new chapter was opened up in the chronicles of Jewry.

One month later, on April 22, 1740, Radziwill authorized by ordinance, all of those ordinances the Jews had previously received from: Stanislaw Danielewicz on June 16, 1635, and those of Jan Sobieski on September 21, 1664, the authorization of the King Jan Sobieski and his sons Jakob, Ludwig and Constantine in the year 1667, as well as the authorization of Constantine of December 27, 1726.

[Page 23]

In accordance with a request made by Radziwill, the Polish King, August III, authorized all of the referred to privileges on March 31 of the same year.

In this period, conflicts arose between the Jews and the city residents regarding the allocation of taxes, and the rulers of the city dispatched commissars to investigate these complaints. In order to put an end to these conflicts, the King authorized new amendments on June 17, 1741. According to these amendments, based on the investigations by the commissars, the Jews were required to pay 60 Gulden out of every 100 Gulden paid in taxes, and the rest of the 40 Gulden had to be paid by the Christians.

These amendments also required that the Jews had to bear the payment of the salaries to the Beller[50] of the city and service workers, and to partake in the costs of repair to the fortifications, the city wall, the bridges and roads and the franchise for the city siren. They were responsible for partnering with the Christians to protect the city from enemies, and for this reason every Jew had to be able to carry a rifle, sword or a pinion. It was stressed in these amendments, that Jews were forbidden to hire Christian service people, but Christian women may bring water to the Jews from a well during the day. Christians were permitted to wash the white goods of the Jews, but only in their own homes. Accordingly, Christian women are forbidden to spend the night in Jewish houses, and every violation of this prohibition was punishable by two hundred floggings. But it was permissible to engage Christian servants without their wives. According to these amendments, the Jews of Zolkiew were provided with a single fortress-tower, apparently for the purpose of protecting the city, and kitchens, and they were responsible for all repairs and to assure their upkeep and good condition.

Radziwill did not live in Zolkiew permanently, and was invited to stay there from time-to-time. During his rule, he was concerned with maintaining order in the city. He oversaw the equitable application of law honestly and with justice. On May 3, 1758, the home of Yitzhak Pasmanik was plundered. Meir Jakobowicz, who came from Muszczysko, was found in the morning severely wounded and unable to recognize anyone. According to the evidence of the Prince Radziwill after a torturous investigation, the plundering was carried out by Yitzhak Pasmanik, Elazar Burkovnik and Eliyahu an appointee of the town. The Prince authorized that they should be killed by the sword, despite the fact that Meir Jakobowicz remained alive.

Radziwill was also concerned about the development of the city from an economic standpoint. In the year 1746, he established a weaving and porcelain factory, and in order to sell these goods, a special store was opened in Lvov. He created a Jewish printing house that lasted a short time in Tartakov, which was near Zolkiew. He also attempted to get an ordinance for the preservation of the Jews from the Catholic Church, especially in connection with the issue of erecting a new synagogue that had been authorized in the ordinances of Danielewicz and Sobieski.

His efforts were crowned with success in 1741. During the visit of the Archbishop Ignacy Wizhitzki to Zolkiew on June 27, 1741, he granted an authorization to the privileges for Jews in connection with a synagogue, but to maintain the customs of the old, pre-existing synagogue, in accordance with Radziwill's explicit request.

This request emphasized that the law required that Christians cannot suffer and cannot forgive the Jews for the murder of Jesus, but quite the opposite. It is their obligation to not allow them to build new synagogues, and to not renew the old ones, and to not permit them to practice their faith, in

[Page 24]

order to punish them for the sin that they committed. But with the indifference and prevarication, and the relaxation of protection of the élite landowners in Lvov, the Jews earned privileges from the elections in which they participated. In every city, cornerstones were immediately laid for a synagogue, to the extent that there was not a town without a Jewish synagogue. However, considering the current situation, and at the request of the élite, the pleading of the heads of Jewish Zolkiew and their entire community, and due to the vigorous effort of the Voievode, Prince Michael Radziwill, the Jews were allowed to perform their customs and to maintain the synagogue already in existence. ‘We are prepared to please them out of a feeling of Christian charity. However, the Jews have to know that they are exiled by the Christians and their servants, and it is their responsibility to respect the requirements of the Church. They are not permitted to possess Christian servants, especially not women under 50 years of age, especially not as wet nurses for Jewish babies. During Christian holidays, in which Church processions occur, they must shutter their windows, lock the doors of their houses, and not go out into the streets. They are forbidden to plan weddings to take place on Christian fast days. And also they may not move the property of their houses to the vicinity of the Catholic Church. In the instance that their synagogue is torn down, they are forbidden to build a new one without the permission of the Archbishop.’

With regard to the Bet HaMedrash adjacent to the synagogue, Jewish youth learn ‘errors and deception’ and they must pay an annual fee to the Church rector in accordance with prevailing custom.

An incident occurred during the reign of Radziwill that shook up the Jews of the city. The family of Gershon Leibovitz was cruelly murdered in 1746 during daylight hours. As revealed by court authorities, the corpses of the parents were in terrible condition, and the daughter was in a state of dying. Gershon's brother, Aharon, demanded a trial for Dominick Dunayevski, the miller from the village of Soposzyn (near Zolkiew), and his servant Andruszko Smicik, since it was discovered they sold jewelry that belonged to the murdered brother. Under investigation, Dominick admitted that he killed Gershon and his wife with an ax, and beat their daughters. He returned to his mill after the attack and hid the stolen possessions, money and jewelry. Dominick Dunayevski and Smicik were sentenced to death, Dominick by beheading and the quartering of his body, and Smicik, by blows from a sword. Before the sentence was carried out, Dunayevski admitted that Smicik did not participate in the murder and was free of wrongdoing. On the basis of this advice, the original sentence against Smicik was dropped. He was sentenced to three years in jail for having benefited from the monies of the murdered man. The sentence pronounced for Dunayevski was carried out completely under the authority of Radziwill. This sentence made a strong impression on the populace, and there were no further incidents of murder and plundering for a long time. The Jews revealed the names of people who sought to sell them items that were stolen from the palace as an expression of gratitude to the authorities and the palace.

There were no lack of incidents of murder and plunder heaped on the Jews of Zolkiew, also in the years that preceded the reign of Radziwill. There were also incidents in which Jews performed criminal deeds, however most of them were within the community itself.

There were two trials held for acts of plunder from churches carried out by Jews who were not from Zolkiew, in 1736. Similarly, the synagogue in Kamionka-Strumilowa was plundered by two farmers who hid part of the stolen goods in the Zolkiew Dominican monastery. Four of the Jews were sentenced to death. A second sentence handed down in a Zolkiew court saw no justice in keeping them imprisoned in Zolkiew, the men were returned to Kamionka-Strumilowa to be punished there.

[Page 25]

In connection to the story of the apostate Jan Filipowicz, who returned to Jewish law in 1728, and according to the testimony of the Christian shoemaker Itzko Meyaricow, he was arrested and under torture, he admitted that the acts of plunder were implemented by the hands of the Jew Moshe, causing the Starosta of Lvov to issue an order to imprison the Rabbis of Lvov, Drohovyzh and Stary.

|

|

|||

| The Entrance to the Great Synagogue of Zolkiew | The Menorah in the Zolkiew Great Synagogue |

|

|

| The Great Synagogue in Zolkiew (a drawing, artist not identified) |

[Page 26]

The Rabbi of Lvov during those years was R' Chaim ben Lejzor, who succeeded in fleeing from Lvov to Zolkiew, but the court dispatched the official Zdaryuvski there. R' Chaim was warned, and successfully fled from Zolkiew to Turkey.

A noticeable change in the relationship between the Jews and Christians of Zolkiew, due to the influence and incitement by the Catholic Church in Poland, began in the 18th century. At that time, the hatred of the Jews by large segments of the Christian populace became stronger. The oversight of the [Catholic] clergy was particularly troublesome for the Jewish synagogue, and created difficulties for the Jews. Through efforts by the community leaders, Cardinal Sofranan, who was subordinate to the Archbishop Samuel Glubiski in Lvov, granted a permit on September 27, 1756, to maintain the synagogue, according to several conditions: a prohibition to work on Sundays and Festivals, a prohibition from appearing in the streets during Church processions, and the obligation to pay the Church priest a holiday fee.

As in many cities in Poland, arguments broke out among Zolkiew residents for economic reasons, but not to the extent as other cities that were close to Lvov. Arguments relating to the right to conduct commerce, and to implement work were brought to the attention of the city rulers who appointed special commissioners to mitigate the issues. An agreement in 1721 that was signed by Pavel Kroyzak representing the butcher's union, and the community heads represented by Shimon ben Avraham Zelig, stated that the community had to pay the union by October 6, 1721, 50 Ducats for prior years, and 10 Gulden every year thereafter, and to give the Christian ‘drinkers’ club a pitcher of whiskey.

A different dispute broke out between the community and the city in 1731 regarding taxes. The commissars, Witkowski, a Castellan from Minsk, and Szecic-Grabianka, a general commissar of the house of Sobieski, were responsible to settle this dispute.

Year after year arguments occurred among the city dwellers and the Jews. These disputes were like a permanent part of their way-of-life. Despite this, strong ties were formed between them on matters of economics and finance. The priests and local monasteries conveyed specific sums to the Jews and the community. The Jews took possession of homes in Christian neighborhoods, and lived there. Arguments did break out from time-to-time, even coming to blows. Many issues were settled in court. But all of this did not disturb the ties of commerce and the implementation of mutual businesses. Despite the prohibition by the Church that did not allow Jews to employ Christian servants, Christians did work for Jews, and Jews for Christians. Despite the prohibitions set by the government and the Church, Christians from all walks of life needed Jewish physicians and nurses, and they bought their medicines from the pharmacy of the Jewish pharmacist, Moshe Hymowitz.