|

|

|

[Page 195]

by Leymka Plishko (Giv'at Ha–Shlosha)

Translated by Yael Chaver

As early as the last days of August, 1939, we sensed that “something serious is about to happen.” However, no one imagined that the “something” would mark the beginning of the terrible tragedy of the Jews of Europe.

I cannot describe all the stages of the destruction of Jewish Wysokie. Here, I would like only to describe the events that happened to me and that I witnessed.

The events are as fresh in my mind as though they happened yesterday. As I describe them, I seem to relive the horrors of that dark period, which is unparalleled in the bloody history of our people. Once again, I see the innocent victims writhing in pain, the bloodthirsty murderers shooting helpless women and children, the blood

[Page 196]

flowing unchecked…the gas chambers, the heaps of corpses, the tall crematorium smokestacks that spewed thick, black smoke day and night. Sometimes, I can still feel the stifling odor that meant only, “You are still alive now, but know that your turn will come, too, and soon the smoke rising from the smokestack will incorporate your incinerated body, will rise to the sky and be lost in the dense black welter.”

So it began

September 1, 1939.

Nazi Germany attacked Poland. World War II began. The town was struck by terror. The radio brought news of bombed towns, battles raging between the German and Polish armies. Everyone was fearful and panicked when word came that the German forces were advancing and the Polish army was retreating hastily. The river of fire was rapidly expanding, inundating towns and villages, and approaching our town.

Four days before Rosh Hashana, on September 10, 1939, German forces took Wysokie–Mazowieckie. The city became a rubble heap, after having been set on fire in previous bombings. But that was not enough for the Germans. They burned up the few structures that remained standing. That day, Jewish Wysokie suffered its first two victims: Avraham–Moshe Balamut and his son Berl were shot by the Germans, and Yudl Zilberfenig, who had gone to Wiszew the day before the war broke out to buy beer from the brewery, was killed in the bombing.

The Jews who had fled from the bombed town to the fields and towns between Wysokie and Mistka village, were safe for the moment. They found refuge in the towns of Sokoły, Ciechanowice, Zambrów, and even as far away as Bialystok.[2] My family – my father Hershl Plishko, my mother Feyge, my three brothers and four sisters – fled to Sokoły.

The day after the Germans arrived, they arrested almost one thousand men over the age of 17 (300 Jews and 700 Poles) and jailed them in the Catholic church. I was one of the arrestees. The older men – Jews and Poles – were freed the next day. The others, about 700 or 800, were deported: some to East Prussia, to Schtablak camp, and some to Zambrów, to military barracks that had been turned into an internment camp.

The transport to Zambrów, which consisted of 150–200 Jews, was forced to walk. En route, the exhausted Berl Vaynberg, Moshe Grushko, Berl Balamut, and Gershon Fridman, were shot.

At Schtablak, the Poles were placed in the barracks, whereas the thousands of Jews from the cities and towns of Brańsk, Zambrów, Łomża, Kolno, Śniadowo, Stawiski, and other places, were sent to the open field and given tents to set up. At night, the Poles attacked them, took the tents and pillaged them, and took the clothes of many people, leaving them naked and barefoot. Trying to avoid additional robbery, the Jews invented various stratagems:

[Page 197]

they wore a boot on one foot and a shoe on the other, and ripped their clothes so that they would not appeal to the Poles. Quite a few Jews successfully fought back the Poles.

We stayed in Schtablak for two or three months, not working. We received one slice of bread a day and some water, and did not change clothes or underwear the entire time. Our days were largely spent picking out pests from our clothes… The tents were so crowded that people literally sat on each other. There was no room to lie down, and we slept sitting up. Some, who could not withstand the hunger and inhumane conditions, as well as the constant verbal abuse by the Germans and the Poles, went insane. Others died due to suffering and distress.

Eventually, we learned that people who had lived in areas taken, or “liberated” by the Russians (using Russian terminology) would be returned to their homes by the Germans. We were told that we would return to Wysokie–Mazowieckie, which – according to the “partition” – was under Soviet authority.[3]

We were stood in rows and led to the railroad station. Traveling in freight cars, we arrived in Ostrołęka. We marched through Ostrołęka to the strains of military music, and crossed the Narew river on foot (the bridge had been destroyed in the fighting). About two km out of Ostrołęka, we realized that no one was guarding us. We were walking through fields of mangold (chard), which we ate and took with us, we headed for Śniadowo. There were 70 or 80 of us from Wysokie. As we passed through peasant areas, we entered their courtyards, and snatched morsels of pig or chicken feed; even these crumbs were better than mangold.

In Śniadowo, we went to the house of the painter Blumshteyn's brother, whose son was among us. We were given food and water. After a short rest, we went on to Zambrów, which was under Russian control. The local Jews greeted us warmly and made sure that we received hot food. We later continued to Wysokie.

Wysokie, of course, had been burned to the ground when the Germans arrived, and its Jews had found refuge in nearby towns. We scattered to the towns in search of our families.

Under Soviet Rule

Our townspeople slowly started to return to Wysokie. Some settled in the few houses that remained standing after the fires, while some built cabins of wood sold by the Soviets at full price. Bit by bit, life embarked on a normal course.

Saturday night, June 21, 1941, the Polish school held a ball. The young people danced, while German aircraft flew over

[Page 198]

the town. The Russians reassured us, saying that these were only maneuvers; they quickly had to change their tune after the planes bombed the airport built by the Soviets near Wróbla forest. That was when they realized that Germany was attacking the Soviet Union.

Many Jews fled to the forests and fields. The next day, June 23, the Germans were in Wysokie. They put up posters ordering the residents not to leave town, to be calm, and no one would be harmed. The “sincerity” of their promise was soon exposed. The day after they arrived, they arrested Shmuel Grinberg, who was chief of police under the Soviet authority, and had been treating the entire population – Jews and Poles alike – very fairly. As chief of police, he hid a rich peasant named Dolongovsky from Brika village in his house. When the Germans came, Grinberg asked the peasant to return the favor and hide him. The Polish peasant “remembered” his kindness, and turned him over to the Germans. Shimon Tenenboym was arrested at the same time. The Germans took them both to Zambrów, and murdered them there.

Under German Rule

The ghetto was established shortly after the Germans arrived. It was headed by the Judenrat, which represented the Jewish population and was responsible to the authorities. The Germans also set up a Jewish police force, which was tasked with keeping order within the ghetto. It should be noted that the Jewish police worked together with the Judenrat, which spared no effort; its members even risked their lives to help the Jewish residents.

The Judenrat had to supply the Germans with workers. The first job was scattering sand on the roadways. Some of the younger people worked for the landowners, and handed their compensation – potatoes and other produce – over to the Judenrat, which distributed the food to the Jewish population.

The Judenrat set up a soup kitchen. All the needy, especially refugees from nearby towns, received two hot meals daily. The Judenrat organized the work so that they could distribute food to Jews from nearby towns who were building the Bialystok–Warsaw and Tykocin roads. They risked their lives to help their needy brethren.

When winter began, the Germans sent young Jews to the forests to cut trees, chop them, and bring them in as firewood. As compensation, they were allowed to extract the tree roots for their own use. The Jewish workers handed them over to the Judenrat, which distributed them equally among all the ghetto residents, for heat and cooking purposes.

Transportation in the ghetto was reduced to two wagons and their horses. They served to transport the workers, to bring food to the road–builders (who were working 20–30 km from the town), and to bring food and firewood from the towns into the ghetto.

[Page 199]

The Judenrat was headed by Rabbi Alter Zak, who risked his life more than once, and saved many Jews thanks to his firm stance against the Germans. The Germans ignored his impertinence, for some reason, and never punished him. They may have had orders not to hurt the head of the Judenrat so as to avoid unrest among the Jews. The Jews were scheduled to be liquidated in stages, and it may have been too early to remove their leader.

Avraham Hertz was Rabbi Zak's closest helper in the Judenrat. He also served as liaison between the Germans and the Judenrat, and was in charge of handing over the quotas of gold, boots, and other goods imposed on the Jews. He cracked under the pressure, became ill, and died at the end of summer in 1942.

Conditions in the ghetto deteriorated steadily. The Jews lived in constant fear. When night fell, no Jew knew whether he would live to see morning. Terrible news about events elsewhere came constantly. Everyone felt that the tragic end was drawing near.

Liquidation of the Ghetto

On Sunday, November 1, 1942, I heard rumors that the Germans had ordered wagons in order to remove all the Jews from the ghetto. We younger men worked at building the road between Zambrów and Bialystok, about 35 km from Wysokie. We gathered to discuss our plans for the next day. The fateful question was, should we or should we not report for work in the morning. Despite our hesitation, we decided to report. Our main motivation was the knowledge that if we did not show up at work, the Jews of the ghetto would be punished.

That evening, Sunday night, Leyzer–Yosl arrived from the ghetto, with the wagon of food sent by the Judenrat. He confirmed the rumors that the Germans had ordered wagons to move out all the Jews in the ghetto.

The next day, when we reported to work, Schwartz (who was in charge of the camp) appeared, armed with a rifle. We were surprised, as he had not carried arms up to that point. His first question was whether anyone was missing. Before we could reply, we were surrounded by armed Germans. We were ordered onto trucks and taken to the town of Rudki, where we were locked up in the jail. This operation had been planned and executed with German precision. All the Jews from the nearby towns who had been working at road–building were also brought in. We were kept in the jail until the afternoon.

We were then loaded onto wagons, and our arms and legs were tied to the sides of the wagon to prevent any chance of flight. Forces of the Polish police and German Gendarmerie, armed with automatic rifles, accompanied us.[4] We knew that many Jews from Rudki and Zambrów had been murdered on this road. There was no doubt in our minds: it would be our last road. We decided to take every possible chance we could at escape. But how can one escape with ropes digging into one's arms and legs? Yet we were determined not to let them lead us like sheep to the slaughter.

[Page 200]

We started to gnaw at the ropes; they gradually loosened, and we wriggled free. But each of us stayed in place; we knew that if our overseer escorts noticed, we would be shot on the spot. This danger was very real, as each group of three wagons were accompanied by a fourth wagon carrying armed Germans and Polish policemen.

It was chance that enabled us to carry out our plan. As we approached the Kosoka forest, a young couple came up. The Germans asked them if they were Jewish; they immediately ran toward the forest. The guards opened fire. We made good use of the moments when the guards were distracted, jumping off the wagons and running as fast as we could toward the forest, to Chervony Bur. The guards shot at us from all sides, but the trees shielded us: no one was injured.

Ten of us in all – Yankl Tikoshinsky, Ayzik Sokol, Efrayim Mazur, a guy from Warsaw, and others whose names I don't remember – ran through the forest for several kilometers. When we were sure that no one was pursuing us, we lay down for a rest. After a while, we started to be hungry. However, we had nothing to eat, and lay there suffering. We spent the night in the forest; at dawn, we oriented ourselves, and decided to return to our area.

A peasant we met on the road asked us where we were going. When we replied, he said, “Do you want to die? Don't you know that the peasants are killing every Jew they find on the road? You'd be better off staying in the forest.”

A shudder went through us. Death awaited us at every turn. If the Germans don't kill us, the Poles will. There's no escape. The world has conspired to kill us.

We split into small groups of two each, and returned to the forest to hide. We stayed until nightfall. By this time our hunger had become painful; we could barely move our legs. We decided to leave the forest and search for our loved ones. We had nothing to lose; we would die in any case if we stayed in the forest.

We walked alongside the road. When we reached the spot where the Germans had shot the young couple, we saw their corpses lying in the same place. Going through Kolaki forest, we continued through forested areas. Occasionally, we approached a shack, or a forest worker, and asked for bread. Dogs were set on us everywhere and we were driven away. The Poles received us with contempt and curses, shouting, “We have no bread for zhids. It's too bad that you weren't all killed!”

I entered the home of a peasant acquaintance. He was friendly, and invited us all into his home, gave us food and drink, as well as a large loaf of bread for the road. The moment we left his home, young Polish boys started to chase us. They planned to catch us and turn us over to the Germans. We scattered in every direction. Romek, from Warsaw, and I ran together. I held on to the loaf of bread, even though it was slowing me down.

We continued on our way. Early in the morning, as we were leaving the village of Galasza and nearing Wysokie,

[Page 201]

I noticed two people walking in the distance. They hid from us, and we hid from them. I realized they were Jewish. When I came near, I recognized Fishl Segal and his son Peysekh. When I asked for news from the town, Peseykh burst out in tears. Weeping, he told me that all the Jews had been taken out of the ghetto, and no one knew where they were. I placed the loaf of bread on the ground, saying, “What use are the tears? We are all lost. But as long as we can breathe, we must fight to stay alive. Let's sit down and eat.”

Fishl replied, “These days, one doesn't throw away bread. You were lucky to get a loaf, so guard it well. That loaf might save you from death.”

I said, “On the contrary. During this difficult time, people must help each other. As long as I have a slice of bread, I will share it.”

We sat on the ground and ate the bread, dampened with our tears.

We continued deeper into the Galasza forest, not knowing where to go or what to do. We were at our wits' end, no longer even afraid of death. Sitting in the forest, we saw someone approaching. I thought, “Let the inevitable happen. I can take no more.” When he came nearer, I recognized him. It was the Pole Sosnowski, whom I had known a long time. He calmed us down, saying, “Don't be afraid. I will help you as much as I can. Stay here–I'll be back soon.”

Sosnowski left. We though he would be back with a gang of Poles, or Germans. But, to our surprise, he returned alone, carrying food and cloths to bind up our bare feet. When we jumped off the wagon, my friend Romek threw away the shoes he was carrying, in order to run faster.

We said our goodbyes. Romek and I went to Wróbla , while Segal and Peysekh went another way. In a settlement near Wróbla, we met Motl Pianko. He told me that my parents were hiding in the forest, near the home of the peasant Wysocki. I went to that house. “That's right,” he answered. “Your parents are not far away.” I went searching, and found them.

It snowed heavily that night. We lay in the forest all night, barefoot and almost naked. The next day, I told my father that I was going to look for my brother Meir in the Masuria forest. And indeed, when I came to the forest I found the eight people who had fled when the Polish youths had attacked us.

Many Jews found refuge in that forest, and hid in shelters they had constructed. They numbered about 150, including the Segals. We would go out at night to seek food, and spend the day in the shelters. One day in mid–November, around noon, my brother Yisra'el came from the Wróbla forest, and tearfully told me that our parents had sent him to bring me food, but that they were gone when he returned. I calmed him, took him in and gave him some food. We were about to leave to look for our parents, when I saw the barrel of a machine–gun being inserted into the shelter. The German command was instantaneous: “Everyone out! I will open fire unless you come out.”

[Page 202]

We crawled out of the shelter. I immediately saw that the forest was completely surrounded by Germans and armed Poles. Before I could grasp what was happening, an armed German walked up to Fishl Segal and shot him in the mouth. Then he went to Hersh–Yitskhok Trestanovitsh and did the same. Both men collapsed and died on the spot. After he had finished off the first two, he began shooting at all the Jews with his automatic weapon. Some were killed immediately, and many were wounded; many of the latter died in the forest. The rest, some with injuries, were ordered to line up, and were marched to Wysokie. We were taken to a stable, where we stayed all night. It was so crowded and airless that when the doors were opened in the morning, several people had suffocated. Leaving the stable, we felt as though we were emerging from a furnace. The chief of the Gendarmerie later came, brandishing a pistol, and started yelling and cursing: “You murderers, partisans, ruffians, were planning to annihilate us. However, we are letting you live, because we are good people. We are sending you to the labor camp at Zambrów.” The wagons came a few moments later. We were loaded onto them, and taken to Zambrów.

We were depressed, exhausted, and hungry, sure that we were being taken to a place where our burial pits had been dug, or that we would be ordered to dig our own pits. However, this time we were wrong. We arrived in Zambrów, all still alive. Most of the Jews of Wysokie were here. The Germans divided us according to our places of origin. Each town had its own Judenrat. Once again, we found Rabbi Alter Zak and his daughter, the physician Golda Zak, as well as the other Judenrat members who did all they could to ease conditions for the unfortunate Jews. Once again, a soup kitchen was set up, and each loaf of bread was divided into eight portions. A bit of drinking water was handed out. There was no salt at all. Many died of disease and starvation.

The Germans took 2 or 3 people from each bloc, and sent them to the forest to gather twigs and make brooms, for the barracks floors. We would bribe our German escorts and, in between the bundles of twigs, smuggle in loaves of bread we bought from the peasants. One day, on December 31, 1942, the Germans ordered us to lay down the bundles of twigs, and continue walking. I was the only person who was able to bring in my bundle and the bread to the Wysokie bloc. That evening, the Germans ordered all those who had carried bundles of twigs to report for whipping. We cast lots to decide who would report. It fell to Shalom Blumenkrants, Fayvl–Moshe's grandson. He accepted his fate, and reported for the “whipping ceremony.” When he returned to the bloc, we rewarded him with a larger slice of bread.

On January 15, 1943, the Germans started to liquidate the Zambrów camp. They announced that people were being sent to work. Hospitalized people were collected and taken to the Christian cemetery, where they were murdered. This took place on a freezing cold night. The sick were flung onto the wagons like pieces of firewood. They were wrapped in rags, half–naked, and exhausted. Some died right there, before any shots were fired.

[Page 203]

The others, who could still stand, were taken out at night in groups, bloc by bloc, and transported by sledge to the Czyżew railway station. Loading onto the sledge was brutal: people were forced to run under a hail of stones, and many died of cold before they reached the station.

In Czyżew, Efrayim Mazur and Leyzer Yellin managed to sneak away and flee, saving themselves. They are living in America today.

When we reached Czyszew, each of us received a slice of bread; we were then shoved into horse–cars, 120 people per car. We thought we were headed for Treblinka, but were “mistaken.” Our destination was actually Auschwitz. Several of our townspeople broke the car open, and jumped while the train was rolling. Tragically, only one survived. Peysekh Dolongevitsh hanged himself in Segal's flour mill, and the others were killed by Poles. Only Itsik Volmer was able to find refuge in the house of a Polish woman, whose husband had previously worked in Segal's mill.

We arrived in Auschwitz on January 17, 1943. As in every death camp, the elderly, the women, and the children were immediately separated from the young men and sent directly to the gas chambers. Men capable of work were sent to barracks in the camp. I was one of the latter.

Young women from other towns were generally sent to work as well. However, the women of our town were not so lucky. All, including the young, were sent to their deaths in the gas chambers upon arriving in the infamous camp. The only two girls from Wysokie who remained alive were the Golobradka sisters, because they had been brought from the Pruzhany ghetto. Only four men from Wysokie survived Auschwitz: Moshe Brener, Avraham–Berl Sokol, Leyzer Gaskevitsh, and I.

I spent two years in Auschwitz. In January 1945, I was taken to Mauthausen, and liberated by the U.S. Army on May 7, 1945.

After liberation, I returned to Wysokie. The town was Judenrein. Everything was destroyed. I found the brothers Khayim and Peysekh Segal, and about thirty other Jews –the remnant of the Jewish community of Wysokie.

In 1946, I left Poland as a kibbutz member, thanks to the Brikha operation, reached Czechoslovakia and continued to Austria and Italy.[5] The British Mandate authorities deported me from the shore of Palestine to Cyprus. I finally reaching the Land of Israel in November, 1947, immediately joined the Haganah, and fought in Galilee during Israel's War of Independence. I am now a member of Kibbutz Giv'at Ha–Shlosha.

Translator's Notes:

Pesach Segal (may his memory be for a blessing), Ramatayim

Translated by Yael Chaver

Before November 1, 1942, we learned that the Germans had ordered 300 wagons, to transport “seedlings” for forest planting. By then, we knew very well what the Germans meant by such “plantings.”

No one in the ghetto slept on the night of November 1. A dark terror engulfed us all. We knew that we were doomed to annihilation. Jewish scouts stood at the barbed–wire fences, trying to hear the slightest sound coming from the other side of the ghetto. Suddenly, the rumor spread that the ghetto was surrounded. The night was dark and rainy. Many people crept through the barbed wire strands and sought refuge in the fields and the forests. About 40% of the ghetto's Jews left that night. I was one of them. By morning, I had found my father, and other Jews, in the Masurian forest. By November 14, I had managed to collect my entire family, except for my brother Khayim.

The individual Jews in the forest formed groups. I witnessed heartbreaking scenes. Children were looking for their parents; parents were looking for their children. The cries and screams split the heavens. The childish wail of “Mommy! Daddy!” rings in my ear to this day.

My friend David Guzovsky and I collected a bit of money, walked to the nearby village, where we bought bread. We were able to give slices to twenty children who were wandering in the forest.

The forest crawled with Poles from the vicinity, as well as Russian prisoners of war who had escaped from German camps.

[Page 219]

They abused the Jews and robbed them. In spite of the risk that they would be discovered by the Germans, the Jews clustered in a large group against the robbers.

The days passed and the winter grew fiercer. It snowed, and we were constantly shivering. We dug trenches, camouflaged them, and found temporary refuge. My family and I were in the same refuge as the Hertz and Tenenbaum families.

On Saturday, November 14, we heard shots close by. The moment I raised my head, I realized that I was surrounded by German gendarmes and Polish police. “Raus!” came the order, indicating that we should come out. When I climbed out of the trench, I saw many dead bodies nearby. The young people were ordered into rows of 30. There were several groups of Jews, separate from each other. The chief murderer of the Gendarmerie approached us, holding an automatic rifle. His name was Erich, and the Jews called him “Makler” (murderer).[1] When he was five meters away, he ordered, “Bring a member of the Herts family; otherwise, I will shoot 20 Jews.” He started shooting without waiting for an answer. My friends David Guzovsky, Biedak, Aharon (Artshe) Herts, David Beker, Hersh–Yitskhak Trestonovitsch, and about 30 other Jews from other groups were shot right there. This terrifying spectacle convinced me that he was planning to kill us all. I didn't panic, but immediately fled into the thick forest. (I later learned that the murderer had turned to my father, Fishl Segal, asking, “Where did you hide your money?” Without waiting for an answer, he shot him on the spot. My mother, Sarah Segal, was slightly wounded.)

When I began to run away, the murderer aimed his rifle at me and opened fire. The bullets flew all around me, breaking off nearby branches. I was not hit, perhaps because I was a well–trained soldier and stayed close to the tree trunks to avoid the bullets.

Those Jews who remained alive, about 100 in all, were returned to Wysokie and jailed. The next day, they were taken to Zambrów, where all the Jews of Łomża were sent.

I was alone in the forest. My mother, my brother Yehoshua, and my sister Rivka were among those returned to Wysokie.

I roamed the forest alone for two days, and then returned to Wysokie, to my home, which was outside the ghetto. I found my brother Khayim, who had hidden with a Polish acquaintance, Danek Kirszenowski.

Wacek Bialicki, the mechanic who worked at our flour mill, helped me find my brother. Bialicki had helped us to build a hideaway in the mill, where we had stayed until December 24, 1942. He had secretly supplied us with food, always fearing his wife or children might find out and turn us over to the Germans.

We were nearly caught one time. The peasant who took over my apartment when we moved into the ghetto informed on us.

On December 24, we had to leave our refuge and find another hiding place. The previous day, December 23, the German Gendarmerie came to the home of our host, beat Bialicki severely, and demanded that he turn over the Jews that he was concealing. The Pole

[Page 220]

claimed that he was not hiding any Jews, and that he had no idea why they were harassing him. The German broke up the floors, knocked on the walls, and dug into the ground in search of the hideout. Luckily for us, and for our savior, they did not discover the refuge. However, after this event we knew that we had to leave; staying any longer would endanger Bialicki's life as well as our own. We had no doubt that the thorough search had been triggered by an informer, and that they would continue to harass the idealistic Pole until we were found.

We began a new phase of constant wandering and hiding, creeping into barns and granaries, constantly cold and hungry, and afraid of being discovered by Germans or Poles. Besides, we couldn't stay hidden for long and expect miracles. We had to go into the forest from time to time, to seek food. I knew almost all the peasants in the area; before the war, they would come to grind their grain in our mill. They, too, knew me, but few were willing to help us. Some feared the Germans, and others were Jew–haters. Occasionally, we obtained small quantities of food with great difficulty, rarely enough to still our hunger pangs. This was our life until March, 1943.

We invented various tricks in our fight against starvation. One was to knock on a peasant's door and ask to buy schnapps. We knew the peasant custom: if schnapps were set out, they would offer food. This trick worked several times.

One bitterly cold evening, when we were gnawed by hunger, we decided to come out and find some bread at all costs, risking our lives. In the darkness, we slowly moved through the fields toward two tiny flickering lights. Finally, we reached the two shacks with the lights. We knocked at the door and asked for a cigarette light. The Pole, whose name was Marcel Grabowski, invited us in. The inhabitants seemed to be decent people. We then asked to buy a bottle of schnapps. The peasant sent his son to the nearby village of Brika to buy some. My brother stayed inside, while I stepped out to stand guard in case the peasant's son brought the police instead of schnapps. Shortly afterward, the youngster returned and placed a bottle of schnapps on the table. We opened the bottle, saying, “Now, dear hosts, we will drink to your health.” I filled two glasses of schnapps, and the peasant set out food. We ate and drank, thanked the peasant for his kindness, and left to continue drifting. Two weeks later, we paid the peasant another visit. This time, we told him that we had hidden a treasure somewhere, and would use it to handsomely reward anyone who concealed us. We agreed on a price. We later learned that we were not the only ones to find refuge with that peasant. He also hid Leyzer Levin and his daughter Pesya in the straw inside the granary. We suggested that he build a hideout according to plans we had drawn up. The entrance was through the cow barn, and the hideout itself was in the field, near the granary, overgrown with tobacco plants.

[Page 221]

We entered this hideout at the end of March, 1943. The peasant, his wife, and his son supplied us with food: a bit of coffee with milk, soup, and bread. We promised him that the war would end in three months–he refused to hide us otherwise. So, when the war did not end as we had promised, they forced us to leave, fearing they would be discovered by the Germans and killed. Several peasants in the area who had concealed Jews were in fact executed by the Germans.

We had no choice but to leave the hideout, and take cover in the grain fields for a while. When news started to come from the front that the Germans were being defeated and the Russians were moving forward, Grabowski allowed us to return to the hideout. We stayed there until Liberation, in August 1944.

Translator's Note:

Avraham Hirshfeld

Translated by Yael Chaver

On September 1, 1939, the first day of the German attack on Poland, the young Jews of our town spontaneously left for other towns or nearby villages.

My brother Barukh (may his memory be for a blessing) and I also fled to the nearby town of Briansk. We saw victims of the bombings there, and the city was very tense. That evening, we decided to return to Wysokie by wagon, sad and dejected. After travelling all night we reached Wysokie in the early morning. The town was unrecognizable. There was a deathly silence, like the silence before a storm. And indeed, our fears were realized. A few minutes later, we started hearing shots. In the center of town,

[Page 226]

several brave young Poles took up arms and tried to stop the German army at the town gates. The response to this desperate effort was a powerful offensive, including heavy air and ground bombardment. The cannons fired ceaselessly, and aircraft bombed each house in turn, with German precision. Everything was engulfed in fire, and plumes of smoke filled the sky. Everything was burning: the sky above, and the ground underneath. The fire rapidly spread through the town, and people – men, women, and children–rushed out of all the houses. In keeping with Jewish custom, the sick were not abandoned, even under these dire conditions. They were moved out of the houses with their beds, in order to save their lives. The groans and cries of the residents were inaudible in the tumult, as the bombed and shelled town was consumed by flames.

Along with my mother and my brother Barukh (may God avenge his blood), we found temporary refuge in the house of our friend, the intellectual Yitzkhak Vatnik, whose house had not yet caught fire. My brother Barukh helped the Vatniks to pack their valuables. But our safety was short–lived. We could see the fire approaching. Shots rang through the dense air, the smoke was stifling, and we had trouble breathing. Roofs were lifting, breaking up under the immense pressure, and flying through the air with an unearthly noise.

That first day of the war, with no place to run to, I really understood the meaning of the biblical verse “The sword shall destroy outside; there shall be terror within.”[1] We ran instinctively, along with everyone else. But where to? Wherever our legs would take us. We are borne along on the human current to the center of town, running between burning, disintegrating houses. Suddenly, as we reached the fields, our mother collapsed. I protected her with my body from the flying bullets. Gathering up her last strength, she continued running with us. We finally arrived at the Segal–Mayzner flour mill, exhausted.

Night fell. The city is still burning; the flames illuminate the night and intensify our depression and despair.

We form a large black mass of people; we've all lost everything in the blink of an eye. We long for the end of this demonic dance.

Suddenly, I hear the din of approaching tanks, and face the first Nazi soldier. I see him through a fog, as though in a nightmare. His finger is on the trigger, aiming at me. He yells, “Hȁnde hoch!” (“Hands up!”) I hear his voice and can't understand what he wants. My mother and brother shout to me, “Raise your hands!” I raised my hands, and escaped death.

Despondent and weary, surrounded by German soldiers all night, daylight finally came. Only now can we see the town and its awful destruction. Smoke rises from the skeletons of the incinerated houses, from bent telegraph and streetlight poles, from trees that were warped and distorted by the fire. Only a few scattered houses remain, untouched by the consuming fire. Among them are Segal's grain mill and home, as well as the house on the corner opposite the Tarbut school, and the Polish church. We did not know where most of the townspeople had gone.

My mother, brother, and I, found shelter in the house opposite the school, along with many others.

[Page 227]

Some time later, the Germans started shooting at the house's windows. Then the order came for all adult male Jews to report to a certain place. The Germans searched everywhere and dragged out those who did not report. I hid, but they found me and hauled me to the same place. Our numbers kept increasing. Surrounded by soldiers, like a large dark mass, people who are mourning, despairing, and facing death, are walking. Where are they being taken? And why? We are led to the Christian church, not far from the municipal offices. We are stood single–file in long lines, facing machine guns.

The hunt lasted all day. Groups of Poles were also brought in. My brother, who sat nearby, whispered, “If there are Poles here as well, we might be left alive.” In the evening of that difficult, fearsome day, we are taken into the church. We lie crowded in a mass on the floor, like marinated herrings, on top of each other. It grows dark. A weak lamp sends a few rays of light through the immense darkness. A German soldier walks among the people lying on the floor, terrifying us.

We got up at dawn, and drank a bit of water in turn, from the same cup. A German soldier stands at the church door, and we file before him as if it were the day of the final judgment.[2] He makes the final decision as to who leaves and who stays. Some old, sick people were allowed to leave. Suddenly my brother Barukh is beside me, ordering me: “Run, flee for your life, you might be able to make it.” I ask him, “How about you?” “I'll be fine, don't worry,” he replies. In an instant, I manage to evade the German's gaze, and go out.

The solitude outside is terrible: nothing but ruins and wasteland. Luckily, there are no Nazis in the empty street. I run quickly, mustering up the last of my energy, to the house where my mother had been. In a faint, I fall into her arms. She summons up her courage and energy, and finds a Polish wagon–driver. They strike a bargain for him to take me to our relatives in the nearby town of Zambrów. There is no one outside. Alone, I part from my nearest and dearest, lying in the wagon as it rolls along; I'm concealed by clothes and various objects. I finally reached my relatives, the Litavskis.

I reached their house completely exhausted. They were all terrified by the German soldiers, who beat on their doors at night and generally run wild.

My mother's fears for me made her come to Zambrów; a few days later, my brother also arrived. He had fled from the Polish church in Łódż, where the Jews from our town had been marched. He recounted how he and some others had wrenched out a grate in the back wall of the church, then jumped six meters to the street. He told us that the Germans had killed my uncle, Berl Dov Vaynberg, on the way from Zambrów to Łomża.

It was my intention here to describe only the first days after the Nazi invasion of Poland, and the events in Wysokie–Mazowieckie at the time. I am incapable of describing my own experiences afterwards.

Translator's Notes:

Shimon Kahanovitsh (may his memory be for a blessing)

Translated by Yael Chaver

There have been no miracles in Russia since the Russian revolution, although Moscow was home to forty times forty churches. However, it was in this city, where there were no miracles, that I experienced a miracle, at a time when miracles did not happen.

But let's tell the whole story as it happened.

When I was four or five years old, my parents traveled from Bialystok to Wysokie–Mazowieckie. This was during World War I, in 1916–1917. As far as I was concerned, Wysokie was the town where I grew up, studied, and joined a Zionist youth group. All my friends and acquaintances were from this town.

My connections with Wysokie continued even after when we moved back to Bialystok in 1931, as we owned flour mills there and shipped flour from Wysokie to Bialystok. The town was very dear to me.

World War II broke out in 1939, and the Bolsheviks took Bialystok, according to the infamous Molotov–Ribbentrop

[Page 232]

agreement. My situation now became much worse. My parents were considered capitalists, although we all worked hard to make a living. We all underwent various harassments; but the worst was that at any minute we could be exiled to Siberia, under the ongoing project of “deporting disloyal elements.”

I had to do something to save my family. Using my old connections, I was able to obtain “proletarian” documents, proving that I was a car mechanic and driver. This was partly true, as I really was my parent's driver, and I was very familiar with the mechanisms of cars. I also became the formal head of the family, and was thus able to place the entire family under my protection as proletarians. This saved my parents from being exiled to the remote, cold regions of Russia.

As a bona fide proletarian, I began looking for work. My connections helped me find work in the transportation section of a large department store. Naturally, these connections were expensive, and gift–giving was a regular arrangement. But it was a solution.

I had two direct supervisors in the department store, one political and the other commercial. I got the job through connections, as they were not local but rather had come from Russia. I thanked them in various ways for hiring me.

This lasted for some time; we slowly became accustomed to the new situation. However, it was not for long.

On June 22, 1941, Hitler's Germany – Russia's partner in the division of Poland – suddenly began bombing Russian towns, and German armies crossed the borders. Bialystok was heavily bombed as early as that first day. The town was in an uproar, especially among the Russians. We, the locals, were somewhat deluded and believed in the great power of Russia.

My supervisor called me in on that first day, June 22, 1941. He wrote out a travel pass, and told me to fill up gasoline for a trip of several hundreds of kilometers. He had not yet told me where to go. I went back home, said my farewells,

[Page 233]

and told them I was leaving for only a few days. I had no inkling that I was setting out on a long, distant road…

The pass was for Minsk. I drove the wife of the political supervisor, as well as the entire family of the commercial director. This director was a Russian Jew named Lyova Paley. En route to Minsk, we saw masses of dead bodies on the roads. The German murderers bombed incessantly. The roads were packed; one could travel only by night.

We arrived in Minsk the next day. There was massive destruction; the city was on fire. No one was in charge. My supervisor Lyova Paley was able to obtain some gasoline, and we quickly left the burning city. We set out for Moscow.

We arrived in Moscow on the third day. I had trouble adjusting to the situation. Only one thing concerned me: the fate of my parents and family. I could think only of returning to Bialystok as soon as possible. My mission was completed, and I could go back home.

I went to the post office to send a telegram, and received the terrible news that Bialystok had been occupied by the Germans, and contact had been severed. I was at a loss, completely paralyzed. Now, when my parents need me so badly, I am completely cut off from them. I did not know what to do.

Lyova Paley invited me to visit him. I felt close to him. He had helped me settle into my job. Actually, I had compensated him considerably, but it was nonetheless a great favor, which I appreciated. We had become good friends during the short period we had worked together.

He took me into a small room, and made up a bed for me on the floor. Exhausted from my trip and my difficult experiences, I fell sound asleep. Loud hammering on the door did not awake me, but I was woken by a boot blow to my side.[1]

Two NKVD agents were standing over me, ordering me to get dressed.[2] I had been sleeping in my clothes. I pulled on my boots, and waited. The agents took me and Paley somewhere. At our destination,

[Page 234]

my escorts received written confirmation that the “merchandise” had been delivered; they then left.

We were left alone, each deep in sad thoughts for our own reasons. I did not think about the past or the future. I thought that there had been some mistake, and everything would be cleared up. True, in the course of the Soviet regime in Bialystok, I had already heard about the arbitrary ways of the NKVD; but, like every young person, I did not take it to heart but shoved the knowledge deep down.

Paley, on the other hand, was experienced in Soviet matters, and knew very well why he had fallen into such heavy gloom. He understood our difficult situation. He knew enough not to try and escape; he was also aware of what was in store for him.

I had trouble convincing him to tell me everything and describe our tragic situation. Once I understood it and grasped it fully, I was even more despondent. Paley consoled me, saying that I would get away with a light sentence or nothing at all, because I was not the target. They needed me against him. He, for his part, was threatened with a death sentence.

I started thinking about how to help him. I couldn't permit him to pay with his life. I felt conscience–bound to help him. I considered possibilities for a long time, until I finally came up with the following plan:

I tore up the “pass” and destroyed it. As long as there was nothing in writing – “evidence” – we could attempt to create a different version of the trip could be attempted, one that would not exacerbate matters. I first gave Paley my solemn word that I would not cause him any harm. I told him to keep to the same phrasing, the same version, and on no account to believe the words of the investigators, or that either of us would confess, or that there was “secret evidence.”

I then proposed the following plan, that we would both stick to: we had received the “pass” from a high–ranking director named Skorbitsh. Skorbitsh had remained in Bialystok, and no one would be able to check whether he had or had not given us the pass, as Bialystok was busy with other matters. As there had been no official announcement, and no one knew of the incident, we could demand that inquiries be made as to whether it was true. As far as the “pass” was concerned,

[Page 235]

I took it upon myself to manipulate it. In short, our version was that Skorbitsh had given us the “pass” and sent us off. In this way, I was hoping to thank Paley for the favor he once did me.

The next morning, we were separated. I was called to the investigator's office, and asked at first about incidental matters, such as how I found life under the Soviet authorities. As usual, I said that it was only thanks to the Soviet authorities that I had steady work and good earnings, unlike earlier in Poland. At that point he asked what seemed to be the main question: who had issued the ticket. I pretended to search for it, and said that I assumed it was in the car. As there had been checkpoints every few kilometers, I had preferred to leave it in the car. He then asked who had given it to me. I said that Skorbitsh had called me in, given me the “pass,” then summoned Paley, and ordered us to go. Now the investigator posed the most important question: why did such a high–ranking official as Skorbitsh give me the document, when ordinarily – as I had said in earlier statements – the “passes” would be written out by the garage manager. I had an explanation ready: it had been Sunday, and not everyone was at work. I also asked him to ask Skorbitsh in Bialystok.

The interrogator asked me what we had done in Minsk. I said that it had been none of my business and that I was responsible only for driving.

I was taken back to jail, but not for long. They soon summoned me to another questioning, even more severe. I stuck to my version. The interrogator claimed that he had not found the “pass” in the car, and that Skorbitsh had refuted my explanations.

I told the same story at the third interrogation as well. The interrogator threatened me, and tried persuasion as well. “What harm would it do for you to sign a statement that Paley is guilty?” All this was of no avail. I repeated my explanations.

I did not see Paley, but I hoped that he, too, was staying with the story. Up to this point, the arrest had not been difficult. Now, it worsened. I was immediately summoned to another interrogation, again warned to tell the truth, or I would stand trial.

[Page 236]

Indeed, the trial soon took place. I saw Paley there. There was a single judge. He brushed away my explanations. and announced that Paley was the one who had written out the “pass.” Once again, I repeated the explanations I had given in the interrogations. Paley also offered the same explanations.

The trial broke for five minutes, and resumed with the following sentence.

Paley received twenty years for escaping, and I received fifteen years.

We were again separated, and this time taken to prison. My heart was heavy. Fifteen years is no small thing; who knew whether I would ever see my family again. But my conscience was clear. I had done everything it dictated. I did achieve something: the judge hadn't been certain, and hadn't given a death sentence.

Late that night in the prison, a Russian official appeared; as was customary, asked whether anyone wished to complain of anything. The Russians knew enough not to complain. It was totally pointless, and might lead to serious trouble. They always answered, “No complaints.” But I was a “greenhorn,” and announced that I wanted to complain. The official asked whether I had been mistreated by anyone in the administration or the cell. I explained that I had no complaints about them, but that it was a matter better discussed in private. He was curious, and told me to come with him.

He heard me out. At first, he was hostile, because I did not accept the court's legality; but when he heard me out he changed his mind. I demanded that he set up a phone call for me with Skorbitsh, to prove my claims. Apparently, this convinced him to promise me that he would help me to make an appeal. He also told that I would be able to reduce my sentence by five years. However, it would be far better for me if I put the entire blame on Paley, in which case I would go completely free. “Ten years is a lot,” he argued, “for such a young person.”

[Page 237]

I categorically rejected the idea that I should inform on Paley. My firmness apparently convinced him. He promised to help.

The trial resumed. Both Paley and I repeated every detail that we had provided in the previous trial and during the interrogations. It seemed that our explanations, which matched, were logical as well. So – mainly because they could not contact Skorbitsh – everything worked in our favor and the great “miracle” occurred: we were both set completely free. I found it hard to believe, although I had hoped and planned for this outcome the entire time. Paley was even more surprised and astounded. As a Russian, he knew that such things did not happen in Russia.

I felt a mixture of joy and sadness. Joy at being freed, and sadness at the news that the Germans were advancing and the Soviet army was retreating from city after city in an “orderly fashion.” I was living proof of this “orderliness.”

Paley wanted to take me with him to Tashkent, where he had family and a place to live. It was indeed a very good plan, but I was reluctant to go far away from my home. Meanwhile, I had heard over the radio that men born in 1912 were being drafted into army service. I was afraid to go anywhere, as I might pay dearly. I was already under suspicion, and could easily have been tried for desertion.

We parted with heavy hearts. He gave me fifty rubles, as he himself was short of money. He also advised me to go to the management of the department store, where I received 50 more rubles. I asked them to connect me with the army's recruiting office, as I wanted to join the army. They sent me to the military commissariat; their connections helped me to get a job in a garage, where drivers were recruited. The fighting forces would regularly take men out and send them to different battalions.

I worked in the garage for a longer time. Conditions were very harsh; there was no place to sleep, as it was a temporary location. I grew tired of being homeless, and asked the garage manager to be posted to a battalion. He was very friendly. He

[Page 238]

Recommended me to his acquaintance, Major Lyapushkin, who commanded an administrative company. He also gave me a good vehicle; this was crucial, as it enabled a driver could fulfil his orders as well as possible, and thereby gain a reputation as a useful and vital person.

Major Lyapushkin was a fine person. He transferred me to a battalion that was stationed in Moscow. As I was a good mechanic, I quickly became highly appreciated by the unit.

Time went on, and winter came. Conditions at the front worsened. There was heavy fighting in Vyazma.[3] The front came ever nearer to Moscow, and the city was hastily evacuated. The government and all its offices were transferred to Kuibyshev. I was very busy with this project. I moved archives and documents from the Kremlin to Kuibyshev. I also transported materials and necessities to the front.

December, 1941, saw severe frost. We were ordered to take felt boots to the nearby front. On one of these trips, there was great tumult at the front, and we were ordered to return. However, I was not able to travel for long, as my vehicle was bombed.

I woke up in a field hospital with cuts on my face from shattered glass. Someone had found me bleeding in the field and brought me to the hospital.

When I regained some strength, I was not sent back to my battalion. New battalions were quickly organized in the confusion. They handed me a rifle and sent me to one such battalion. This was how I became a complete front–line soldier.

Our battalion had no vehicle at its disposal, but did need one urgently. Many broken–down cars lay all around; choosing wisely, it was possible to patch together a car from their parts. There were only two types of engines in Russia at the time. I proposed to my lieutenant that I should be given tools and workers, and I would assemble a working car. He liked the idea, and I carried out the project. Three days later, a car was ready.

I had pieced the car together so that I would have a chance to rejoin my battalion in Moscow. I waited for a while, until I was able to travel to Moscow. Naturally, I had no documents allowing me to enter the capital. Instead, I had

[Page 239]

some brandy. Thanks to the liquor, I was able to telephone Major Lyapushkin.

The major was happy to see me, and came to get me in person. He immediately took me back into the battalion, repainted my car, gave it a number, and I was once again “at home.”

The Germans began their spring offensive in April 1942. The fighting was fierce, and a regular flow of supplies was necessary. I was near Vyazma several times. Once, I was there during a German advance; before we knew it, we – a group of drivers with cars–were encircled by the Germans.

The first thing I needed to do was to separate myself from my fellow drivers; I was afraid they might say that I was a Jew. As the Germans took very many prisoners, I was able to join a different group. Escaping was impossible, and there was nowhere to hide, either. Having no choice, I was shoved into a barracks with my new friends.

The Germans did not know how to drive cars under the conditions of a Russian winter. Thus, I had no trouble working as a driver once again. But being a driver under German command was not easy. They were very nervous, and suspicious that anyone might be a Jew or a partisan. They tried to find out several times whether I was Jewish. On one occasion, two high–ranking Gestapo officers asked me in German whether I was hungry, and ordered me to eat.[4] I pretended not to understand, although I was very hungry. Incidentally, they both spoke fluent Russian.

I was terribly afraid of a mishap. How long could this last? The Germans acted wildly, shooting people for the slightest reason. Obviously, the situation increased their edginess. They were also in a panic because of the partisans; this was clear from their expressions. They would go on rampages and shoot entire groups of men. The slightest suspicion or remark would lead to the shooting of anyone they considered a potential enemy. My situation became less bearable by the day. I felt that it could not last long. I was resigned to anything.

Deep inside, I had faith that I would be rid of them and not

[Page 240]

have to see their savage faces. I could not stop thinking about escaping. The idea obsessed me; one day I took my vehicle, made sure I had an iron bar – one could not steal a weapon – and set out with a ration of bread. I managed to get far away from the unit's position.

I crashed the car in a ditch, and went into the forest – there were many of those in the region. I was hoping to penetrate the front lines and rejoin my battalion. Going through German–occupied territory was out of the question, both because of the Germans and the hostile attitude of the local population.

I lay hidden in the forest all day, afraid I would be noticed. It grew very cold at night, but my only option was to wait. I did not know which way to go.

I lay there in the murky darkness a long time. At one point I heard steps. People were walking, and moreover – speaking Russian. I could not make out what they were saying, as they were too far away. I was careful not to reveal myself, as I was afraid and did not know who they were. They went up to a pit, and either put something in or took something out. I decided that the first thing was to find out what was in the pit. So I waited for them to leave.

They did leave soon afterward. I waited for some light, and came up to the pit. Once I had removed the camouflage, I discovered an arms cache. I selected a revolver and took a large amount of ammunition. An armed man had to be reckoned with, regardless of the situation.

Now armed, I still did not know what to do next or where to go. Having no better choice, I lay in the forest for another day, waiting for the nocturnal visitors. In the meantime, I concealed myself with branches so as not to be discovered accidentally. I waited for the pitch–black night.

The same people came back late that night. I quietly sneaked behind them, holding my weapon, and asked them in Russian who they were.

After a brief conversation, we came to an understanding. I told them my story, and they said that they were a small partisan group, which blew up railway lines that carried German troop trains.

[Page 241]

They supplied their own food, requisitioning it from the peasants at night. There was a Jew among them, with whom I became friendly.

I had a bad feeling about the place. I very much wanted to return to my battalion. Finally, I convinced my commander that I had received permission, as well as help, to return to my unit.

The way back, regardless of whatever help I received, was very difficult and fraught with danger. That is another story, and I don't want to describe that time here.

I finally returned to my battalion –my second home – uninjured and in good condition. Once again, I sat at the wheel and transported vehicles to the front lines. The further away the line moved from the capital, the longer were my trips. I gradually moved westward, along with the front. This continued until 1944.

The Soviet army then entered former Polish territory. Familiar names of cities and towns began to appear in the communiques. I had mixed feelings. On the one hand, we knew about the terrible annihilation, yet on the other hand we hoped for…maybe…something.

Finally, I heard the names of Bialystok and Wysokie in the communiques. I was anxious to leave. When they dispatched a column of 150 trucks to Ostrów Mazowiecka, I was, naturally, one of the first to go.[5]

Near Vawkavysk, I first became aware of the great disaster. My aim was to see Wysokie and Bialystok – two places where I hoped to meet someone of my kin. I feared the encounter with reality, but had to go. After all, miracles can still happen.

I requested my commander for permission to visit my two home towns on the trip. He gave me permission to make a detour and see – even though briefly – my home towns.

Our house in Bialystok was occupied by strange Poles. The curtains, couch, tablecloths, and other objects were ours. They were familiar, beloved, and comforting. But the people in the house

[Page 242]

made them seem alien. The Poles were alarmed when they first saw me. Besides, I was wearing a Russian uniform. However, when they realized that I was paying no attention to the plundered property and was interested only in my kin, they calmed down.

That night, I slept in Bialystok, if insomnia and being overcome by profound sorrow count as sleeping.

I entered Wysokie early the next morning.

The formerly Jewish town was now Judenrein.[6] There was not a single Jew to be seen. The street was full of unfamiliar, hostile faces. I met a Polish acquaintance named Podszilo, who told me that my entire family had been killed and that nearly all the Jews had been murdered. The few surviving Jews were living in Peysekh Segal's mill. Among them was Pianko. I hurried over there, but could not stay long, as I had to catch up with my column.

I returned as soon as I had reported in Ostrów Mazowiecka. Back in Wysokie, I wanted to meet my surviving friends. We shared our troubles. They coaxed me to leave military service, wear civilian clothing, and join them.

I dearly wanted to be among Jews, especially as these were my own people. Yet I did not want to be a deserter. It was not in my nature to hide. My military service was relatively comfortable, and the main thing was that I wasn't being sent to the front lines. Besides, my work as a driver provided me with better conditions than most.

True, there was no shortage of unpleasantness and anti–Semitism here, either. Once, I was even slightly punished. The incident was as follows:

My vehicle was excellent. Yet once I couldn't start the engine. I tried everything, checked all the parts again, cleaned and polished the engine, but it didn't start. Then one of my helpers told me that someone must have poured sugar into the gas tank, preventing the engine from igniting.

I was very annoyed by this, and decided to teach the anti–Semite a lesson, or even worse things would happen. I informed my superior that I would not sleep in the barracks as I needed to go somewhere. He gave me permission, smiling ambiguously. I

[Page 243]

took an iron bar, crawled into my vehicle, and lay down to wait for the hooligan. He showed up late at night, first inspecting his own vehicle and then approaching mine.

He took out a packet of sugar, unscrewed the top of the gas tank, and started pouring in the sugar. At that instant he was attacked by me. I beat him up. People came running when they heard his screams.

We were both arrested. Proof of his guilt and the damage he had caused was clear: the sugar was strewn on the floor. He received a harsh sentence: to be sent to the front. I was also punished, for fighting–to chop wood for two weeks, and do no driving during that time.

I recount this in order to show that the battalion was none too nice to me. If I had committed one more crime, I would have been sent to the front. In order to be a good driver, one had to commit crimes, wheel and deal, skim off the top, take one's cut. In such situations, the slightest mistake could lead to a sentence of being sent to the front to join a labor battalion.

I decided to stay within the law. I remained in the service. I served in Moscow until May 1945, the end of the war. I shuttled back and forth to the front, driving vehicles and waiting for the end of my service.

Finally, I lived to see it. The war ended. Moscow celebrated the victory. But in my heart there was only a deep wound. It was December 1945 before I was demobilized. As a “defender” of Moscow, I had the right to become a resident of the city – a privilege that any Russian citizen would have counted himself lucky to have.

However, I only thanked them for the privilege, and left for Poland. At first I went to Bialystok, and realized that I couldn't stay there – the tragedy was too profound. I then went to Wrocław. However, I could not be at peace in this Lower Silesian city, where remnants of survivors and repatriates from Russia had gathered. I stayed for a few weeks, long enough to work a bit, purchase new clothes, and appear more presentable.

It was a period of chaos. No one knew what the next day would bring. I crossed the border to Czechoslovakia and entered a displaced person camp. As a driver, I placed myself at the disposal of the Brikha – the Jewish operation that smuggled Jews into the Land of Israel.[7] Enormous streams of Jews were smuggled out of the camps to locations closer to the borders of the Land of Israel, and eventually transported there on ships. The British ruthlessly persecuted both the young people who carried out the operation and the fleeing Jews.

My next stop was Kassel–Frankfurt.[8] I had been doing this work since my youth, and continued doing it out of a deep love for Zion, combined with the bitter experiences of recent years. The entire operation was linked with the years of misery that people had endured. Once again, I had no permanent location. For a time, I worked as a driver for an American organization. Fate did not want me to give up the wheel.

I was tired of moving around, and sought a place where I could rest my head. The prospects of traveling to the Land of Israel were poor, and I had no patience for waiting. I was on my own, with no one to advise me.

At that time, various consulates were registering potential immigrants. People found relatives all over the world, requested documents, and registered wherever possible. I did the same.

The U.S. consul was the first to call me. It was in this way that I came to America in 1948.

(This chapter was written by Mr. Kirsh, who interviewed S. Kahanovitsh [may his memory be for a blessing])

Translator's Notes:

Motl Ptashevitsh, New York

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

Among fields and forests, With villages all around, Lies my town, Wysokie–Mazowieckie, My home town.

Streets and alleys,

A large County building,

Not one to lag behind,

Houses built of wood

A community hospital, a travelers' inn,

A rabbi, so imposing, |

[Page 246]

|

Gardens, orchards, Roads for pleasure walks, For young peoples' fun, And political debates.

Proud young folks,

They started political parties,

Fine homeowners,

They included

Neighbors were like brothers,

The insane, |

[Page 247]

|

This is how I see my town, If I remember correctly. That's where my cradle stood, The scene of my childhood.

An archenemy[1] came,

O, Wysokie, my lovely town,

And to you, my brothers,

Let the words |

Translator's Notes:

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

|

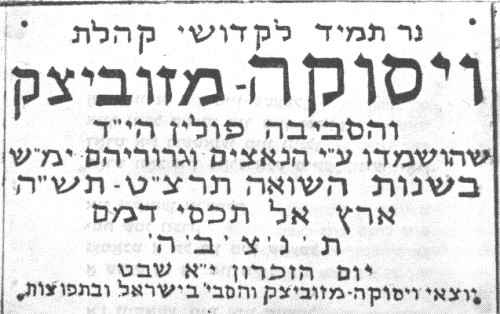

| Plaque commemorating Wysokie-Mazowieckie in the Chamber of the Holocaust, Mount Zion, Jerusalem |

|

|

| Wysokie survivors at the monument in the Forest of the Martyrs |

[Page 249]

|

|

| The audience at the annual memorial service for the martyrs of Wysokie, on the 11th day of Shevat |

|

|

| The audience at the annual memorial service for the martyrs of Wysokie, on the 11th day of Shevat |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Wysokie-Mazowieckie, Poland

Wysokie-Mazowieckie, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 28 Apr 2021 by JH