|

|

|

[Page 234]

by Mordechai Ehrlich, Kiryat Motzkin, Israel

An inner emotion disturbs my rest – perhaps we will be too late! [It is this which] moves me to pen these lines.

I, one of the last of the generation of our city, in which we were raised and educated, despite the fact that we have been gone for decades. If we do not undertake to do this sacred task, it will not be done by the generation for whom that tie has been sundered.

It is a responsibility that falls on all of us, to memorialize for all time all of the scions of the city who were murdered, and put to death such that no man knows where they lie buried.

Let this book serve as a monument for us and the coming generations.

My pen trembles when I remember what happened to my relatives, and in general, to the Jews of Tomaszow.

[It was] a city that counted about twenty thousand residents, most of them Jewish, that, in its day, was privileged to have a leader of the city who was Jewish – Yehoshua Fishelsohn ע”ה, surrounded by an abundance of pine forest, which served as a meeting place in the summer for young and old alike.

It was a city that was not uniformly developed, and was partly neglected. It had no sources of economic activity, no factories, with most of its residents living in considerable want, yet rich in its Jews. No matter in which direction you would turn – Jews. Religious Jews, Hasidim, and even a small number of progressive Jews. There was an abundance of synagogues, houses of study, and Shtiblakh, that throbbed from Jews at prayer, and adherence to Talmud study, with a refrain that spilled out into its streets.

Slowly, slowly, the course of life flowed on. Night – day, with each day like the next. Today was like yesterday, and so would be tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow would be like yesterday. The railroad was at a distance of seven kilometers from town.

Life is manifested with a traditional imprint, in the deeds and legacy of ancestors, a chain of generations, in a set of links, where each resembles the other. It was in the same place, in the same house that one's father, father's father, and his father, that one lived one's self, as it was received by inheritance.

Even the forms of livelihood, though impoverished, and of a minimal nature, they too were handed down as a legacy: storekeepers, merchants, saloon keepers, the Jews that served the nobleman, sporting houses ‘forbidden,’ ‘Open Tobacco’ without permission, tradespeople, butchers, wagon drivers, water carriers, etc. All anticipate the ‘Market Day’ on Thursday, the day that will sustain them for the remaining days of the

[Page 235]

week, and especially to fund the preparations for the Sabbath.

‘Market Day’ was the basis for sustenance for hundreds of families. It is deeply etched into my memory, because my parents' home stood close to the place, and I was able to observe it for years.

In the heart of the city is a large, empty lot, around which goes a walk path shaded by trees, getting filled up from the earliest hours with hundreds of wagons from the village folk, with their wives, until there is literally no more room. Around the walk are stands on which are long white breads, black round loaves, pitas, rolls, and ring cakes. There are stands with fruits and vegetables, stands with ready-made clothing, shoes and boots. A Jewish woman with a barrel of salted fish, not of the best quality, whose odor could be sensed all around.

The women vendors sit under the burning sun in the summer, and in the winter they are cloaked in lamb's wool, with a pot full of glowing coals flickering under their dresses to keep them warm. They call out in loud voices to the lady villagers the ‘goyehs,’ ‘shiksehs’ praising their wares.

We must not, God forbid, skip over people in a higher station. However, the number of such people was not great, and these are the owners of stores that were pretty, and well-organized on the Lwowska Street, the merchants of forest products, Jews of means, wit leisure, standing and milling about with their walking sticks, leaning on the fence of the ‘public’ park that was set aside for the exclusive use of Christians. They would stand like that for hours, days, and years.

Life was sustained from these kinds of occupations, raising sons and daughters, paying tuition and giving charity.

Sabbath and the FestivalsOn Fridays, with the arrival of darkness, everything vanished. The wagons, the market stands, the people, and the square remains standing deserted, abandoned as if it was orphaned. One hears the sound of keys turning, the scraping of doors and shutters. Jews are returning from the bath house – which does not operate according to all of the details of the sanitation code – inside it is flaming, with measured steps, and underneath the house are the dirty bricks that were laid out.

One person stands in his Sabbath rousers, with a vest over his fringe garment, polishing shoes in honor of the Sabbath. Women, with sweaty faces, sit outside, resting from the burdens of the labor of doing all the Sabbath preparations, and in the process, snatch a bit of conversation with their neighbors. Children in their Sabbath finery, with shined shoes, walk diligently and carefully while holding a bottle of sacramental wine in their trembling hands.

Snippets of the melody associated with Kabbalat Shabbat are waft from the synagogues, and the festive voices of the worshipers. An alarmed ‘laggard’ hurries home, whipping his horses with an angry nervousness, and the wheels of his wagon reverberate noisily on the stones of the street.

With morning, a shutter is opened, a woman, wrapped in a coarse housecoat, calls to the ‘Shabbes-Goy,’ strolling with his wife expansively, in the quiet of the street, in whose hands are bags of bread rations that they receive from the Jews for stoking the oven and removing the candlesticks from the table.

A Jew, in his house slippers, returns from his morning ablution in the mikva before prayer. Men, enveloped

[Page 236]

in tranquility, are walking to the synagogue. Their prayer shawls are tucked under their jackets, and on their heads is a yarmulke that sticks out from beneath a hat. Behind them are women in their Sabbath dresses, with the little girls behind them, carrying the prayer book, ‘Korban Mincha’ with a white embroidery wrapped around it.

During the festive afternoon Sabbath repast, children carry pots full of the warm food for the Sabbath from the nearby bakery ovens. Jews return from Kiddush amid vociferous discussion. The sound of Sabbath song bursts forth from the open windows. There is the rest taken in the afternoon, the pleasure of a ‘Shabbat Nap.’

The Jewish community was centered about the Lwowska Street. At its head, stood Mr. Shmuel Shiflinger, and its Secretary Aryeh Levenfus ע”ה. Its mission was highly circumscribed. It did not concern itself with the establishment of educational institutions, or cultural ones, etc. Sources of revenue were meager, and apart from a minor sum that came from the ritual slaughter of fowl and cattle, expenses covered building maintenance and the limited functions [of the community].

Accordingly, a certain vigilance was felt by the community leaders when it was necessary to retain a Rabbi, a ritual slaughterer, and the like. One of the tasks that required its sanction, was the retention of the first Jewish doctor, Dr. Shulman הי”ד. At the beginning, he was involved with the Jews, but after establishing a location, he consorted with the Christian intelligentsia for lack of such a group in the Jewish settlement.

A Bank Spoldzielczy was established that served both Jews and Christians before the First World War, at whose head stood Dr. Zawadzki, a liberal Christian, an enlightened man, who was a student of the Tanakh, and a lover of Israel. The bank employees were purely Jewish.

My father, of blessed memory, R' Kalman Ehrlich, was one of its original founders and employees. Most of his Jewish friends, storekeepers of middling status, who wrestled with survival. Were pressed to utilize loans and credit. It took over a central location in the town in a pretty and tended garden (Kasse Gorten) and its reputation went out before it.

After The First World War, the town placed its remains in the premises of the bank. It's Jewish Secretary, Eliezer Dornfeld הי”ד served in this position until the year of the Holocaust. The bank transferred to its new building opposite its prior location.

In 1930, a purely Jewish bank ‘Nadorkor’ was established as a workers bank. Its members were craftsmen, and diligent storekeepers. At its head stood Mr. Hirsch Meir Cyment, and Elazar Bergenbaum ע”ה.

The Gemilut Hesed existed only nominally. It could not respond to the demands of the needy, and its management was primitive. Many who came to knock on its doors did so in vain.

Educational InstitutionsOur city was poor in educational institutions in general, and in Jewish ones in particular. Despite this, the government established a general school and a high school, but many of the Jewish children, especially the sons, did not attend them, for a variety of reasons, such as: to have to sit with head uncovered, boys and girls mixed together. Accordingly, there was a preference to send their sons to Heder, in which secular studies were taught at the margin.

[Page 237]

The high school was open to all capable children of the Christian residents, and to a limited number of the more fortunate among the Jews. There [sic: the Jews] numbers were smaller because of the ‘Numerus Clausus’ law.

The issue of observing the Sabbath, and the cost of tuition, foreclosed the gate with certainty. Among the results of this was the absence of a Jewish intelligentsia. Part of the young people streamed to the various houses of study, and to the shtiblakh, to study Torah, some went to work, and a portion went into the business of their parents, or simply were left idle.

In the year 1918, with the conclusion of The First World War, activists of the Mizrahi youth arrived, headed by Mr. Joseph Lehrer, who was found among us, from the Land of Israel. They saw a great responsibility, to the youth that was trying to get education, but without any Jewish schools. It was decided to establish a progressive ‘Mizrahi’ school. The curriculum consisted of integrated secular and religious subjects. Its first teachers were: R' Benjamin Tepler, teacher of Talmud and Pentateuch, and Alter Gitlin from Baranovichi, teacher of Hebrew and Tanakh. Nahum Dov Glass as the teacher of experiments. The school had forty students, and was located in the house of Yitzhak Maiman on the Zamoyski Street.

Two months had not gone by, when a great fire broke out and burned down the entire town, except for the northeast quarter. Despite the fact that the house that contained the school survived, the rooms were grabbed up by those who survived the fire, and the students were scattered about.

Thanks to the efforts of the teachers to preserve the school, they succeeded in obtaining two rooms in a timely fashion, in the home of Avigdor Eidelsberg, but after a short while, all their efforts came to naught, and in the end they were forced to close.

The Mizrahi activists did not remain silent, nor did they feel their work to be complete. Their sense of responsibility to the local youth, to assure they do not remain idle, and to educated them in a Zionist pioneering spirit, gave them no rest. At the end of the year 1919, with the visit of Rabbi Graubart ז”ל from Stacze, and the arrival of a group of Mizrahi activists to the office in the house of R' Israel Garzytzensky ז”ל, Among them were: Chaim Joseph Lehrer, David Yud'l Szparer, Zusha Kawenczuk, who [sic: today] are found in Israel. Kalman Ehrlich, Yaakov Lederkremmer, Sholom Zilberman, Leib'l Lederkremmer, Yankl'eh Arbesfeld הי”ד. After many deliberations, it was decided to, once again, open the school.

This decision was taken with great trepidation. There was the concern of how to sustain it financially, as well as other aspects. One of the issues was to find a suitable building. After extensive searches, it was decided to rent the house of Zvi Winder, even before the building was completed.

With its opening, the number of students grew to one hundred, and courses were conducted in accordance with their normal manner. With its expansion, the number of teachers also grew. To the two teachers that I have already mentioned, were added, the son of Rabbi Graubart of Stacze, as a teacher of Hebrew and Tanakh. The teacher, Frischleiser from Lvov was added to teach Polish and Arithmetic. After he left, we retained Zvi Edelstein and Yeshayahu Firger הי”ד.

The school did not have much time to breathe freely. After several weeks, with the outbreak of the war with the Polish-Bolshevik War, the normal rhythm of the school was disrupted, and there was a need to close it. With the end of the war, classes immediately started up again. As the Principal and a teacher, Abraham Huberman was retained, one of the teachers who excelled in both direction and leadership simultaneously.

[Page 238]

His influence contributed to the development and progress of the school.

In the year 1921, before the holiday of Shavuot, the Office of Education closed down the school because it was not recognized as a [sic: legitimate] educational institution. All attempts to nullify this order were ineffective. After its name was changed to ‘Torah V'Da'at,’ was permission granted in 1922 from the Office of Education, and the enlightened government administration to re-open it. It continued to function without interruption until 1929.

In that year, the school joined the network of ‘Yavneh’ schools in the Histadrut, from its foundation in Mizrahi. Even its name was changed to ‘Yavneh.’

Mr. Zvi Edelstein was retained as the secular principal, and teacher of Polish. In addition to the teachers that I have mentioned above, were added: Shmuel Blei, and Karelman as Talmud teachers, Joel Kaufman for Hebrew and Tanakh, and to be separated for long life, Mr. Shapiro, currently to be found in South Africa, Aryeh Arbesfeld, and Mrs. Sandberg who are in Israel.

With the expansion of the school that was [now] comprised of over one hundred fifty students, it was necessary to rent a number of rooms in ordinary houses. As you can understand, this had an adverse influence on the way instruction was implemented. In the year 1934, there was success in renting one large building that consisted of seven rooms, from Moshe Adler (Latter) on the Krasnobrod Street. The leadership of the school passed into the hands of Mr. Kessler. A number of years before the outbreak of The Second World War, a Kindergarten was opened, by the school, in which there were forty children, and for which a separate, suitable building was erected.

It is necessary to underscore the not-very-little amount of laborious effort and the sizeable dedication of Mr. Yaakov Arbesfeld הי”ד, in his role as the central technical director from 1925 up to his last day.

In the year 1938, at the twentieth anniversary since its establishment, this halfway jubilee was celebrated with a large assembly, with the participation of Dr. Sh. Z. Kahana, the Director of the Histadrut ‘Yavneh’ schools for all of Poland. Today, he is the director of the Ministry of Religion in Israel. The newspaper, ‘Das Jüdische Leben,’ of the Mizrahi Histadrut in Poland, published a special supplement that was dedicated to the halfway jubilee of the school, which got a lot of play in the vicinity. A generation was inculcated with a love of the Homeland, for the pioneering movement, and for the rejuvenation of the Hebrew language.

The first graduates continued at the ‘Takhkemoni’ school in Warsaw, in high school, and at universities throughout Poland. Many tribulations and crises befell the school. It survived only thanks to a group of activists, who saw a sacred duty in preserving it, and who contributed a great deal. The sowed with tears, but they reaped with joy.

My responsibility in setting down this record will not be properly discharged, if I do not underscore the dedication and tiring hard work, done without compensation, and performed by Mr. Chaim Joseph Lehrer. A man of noble spirit, full of activity, and able to energize others, who led the school from the day it was founded to its last day, when it ceased to function. He truly raise the standard of the institution during the fruitful and blessed era in which he led it.

[Page 239]

|

|

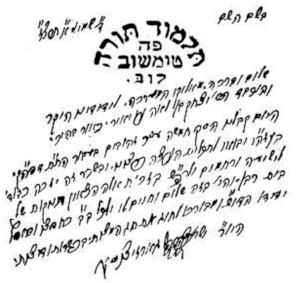

The network of Jewish educational institution also encompassed a Talmud Torah of several tens of students, children of the poor, from the less-endowed classes, most of them orphans, hungry for a slice of bread. Barefoot, and in tatters.

In the year 1929, the responsibility to provide shoes was allocated to one of the respected balebatim, a Torah scholar, wise, of impressive appearance, and an Elder of the community, a man who had great influence – my grandfather, R' Israel Garzytzensky ז”ל, and, to be separated for long life, Mr. Yitzhak Karper, a forest merchant, well received both in the Jewish and Christian communities, and today with us in Israel. They gathered a number of other respected balebatim around them, Mr. Aharon Lakher, ז”ל, and others, who dedicated a substantial part of their time and energy to this undertaking. They linked up the Jewish community with other public institutions. After a while, a house was obtained for this purpose, and the number of students grew to about one hundred, receiving food, drink and clothing to wear.

How joyful it was, and how the heart beat, to see these children stroll off to the forest on Lag B'Omer, with bows and arrows. Wearing festive holiday clothing of their own, and new, shined shoes, with their teachers and melamdim, with packages of food for their adventure in their hands.

Groups and Youth Movements

|

|

Among others, the following are found on the picture: Chaya Stang, Fanel, Mirachnik, Shayndl Arbesfeld, Rachel Lichtenstein, Gitt'l Fersht, Leah Arbesfeld, Feiga Goldman, Shayndl Zucker, Sarah Fersht, Masha Shaffel, Rivka Tanenbaum, Rivka Blank, and Katz |

|

|

Among others, the following are found on the picture: Jonah Zilberstein, Leib'l Lederkremmer, Sinai Putter, Yitzhak Borenstein, Israel Greenbaum, Hirsch Zilberberg, Avigdor Eidelsberg, Chaya Putter, Y. Minkowsky, Abraham Pfefferman, Zilbergeld, Chaim Goldzamd, Hirsch'l Ehrlich, Ary' Levenfus, Asher Herbstman, David Shapiro, Moshe Eilbaum, and Moshe Eidelsberg |

Our city was blessed with all of the groups, beginning with the Zionists all the way to the Bund, and communists.

The general Zionist movement, at whose head stood Avigdor Eidelsberg הי”ד assumed the central position and was the progressive group. A number of the Mizrahi membership went to the general Zionist movement

[Page 240]

because most of the city residents were religiously observant, and therefore this movement appealed to them. At its head stood Chaim Joseph Lehrer. He was one of the founders of the movement in the city, a man knowledgeable in literature, and who accomplished a great deal, a powerful protagonist without bounds. He was at one with his ambience, and stood at his post up until the destruction of the city. This movement established a training camp of Poel HaMizrahi at which tens of pioneers received their physical training and pioneering indoctrination before they made aliyah to the Land.

The Poalei Tzion group took a very respected position – Tze'irei Tzion at the head of which stood Fyvel Holtz הי”ד who dedicated his heart and soul to it. The youth movements of HaShomer HaTza'ir, HeHalutz, and Freier Skut all coalesced around it.

Hundreds of young people found a place in the movements, most of them in ‘HeHalutz.’ They went out to training camps, and were spread out all over Poland. Many of them made aliyah, and continue the legacy of Tomaszow scions in the Land of Israel.

The activities of the Zionist movements in the city were legion. They played no small part in the collection of donations to Keren Kayemet and Keren HaYesod, at parties, weddings, flower days, etc, that were arranged by the young people, and in which they saw a sacred duty.

And they suffered no little subversion by Agudat Yisrael, ordinary Jews, Hasidim, and fanatics, who saw in this work that was sacrilegious.

On the eve of Yom Kippur, at the time of the Mincha service, it was an accepted custom to give to charity, in order to redeem one's soul. On the ‘Balemer’ {the table on which the Torah scroll was placed to be read) plates were set out for all the various institutions that helped the poor, anonymous giving, the Talmud Torah, the Yeshivas, R' Meir Baal HaNess, etc. It was also the custom to put out a plate for Keren Kayemet and Keren HaYesod.

An incident occurred in the house of worship of Rabbi Yehoshua'leh, where most of the worshipers were Hasidim, known to be great fanatics. The writer of these lines volunteered not to skip this house of worship with a plate set out for Keren Kayemet. My decision was accompanied by great trepidation, because I know fully well, before whom I would be standing. Thanks to my family connections, I had the nerve to stand beside the ‘plate’ in silence, and to observe who might choose to seek redemption for their soul by making a donation to Keren Kayemet, and Keren HaYesod. This was in vain, since this plate was orphaned [among the others]. And then, an elderly Jewish man entered, bewhiskered with a long beard, with curly side locks, wet from his ablutions at the mikva, his lips moving silently in prayer. He approached the table with the platters, placing his coins in plate after plate. When he came to the row of the Keren Kayemet plate, he stopped dropping coins, and with an angry cry, he asked: ‘Who is the sheketz[1] who had the nerve to place this abomination in this holy place?’

With frightened respect, and without moving, I indicated that it was myself. In one moment, he gave me two slaps to the cheek that were forceful enough, in front of the entire assembly of people. My reaction was not to move, and also not to remove the platter.

[Page 241]

A sense of dissatisfaction coursed through the worshipers in regard to the behavior of the individual who disturbed the mood of the prayer leading to Kol Nidre.

It was not trivial for the young Zionists to contest with the fanatics on one side, and the Bund and communist on the other side. Nevertheless, their resolve stood with them.

In part, the words of the prophet came to be: ‘and the wolf lived together with the lamb.’

Today, in the Land of Israel, can be found those, who in days past, were opposed to the State, as citizens with equal rights. A shame! What a shame! It is a shame that so many did not reach us, and no man knows where their graves might even be.

Let their memory be for all eternity!

by David Y. Levenfus

The B.B.W.R. (Pilsudski's Sanacja) and the Jewish Voters

The Tomaszow Jews took an involved part in the elections to the governmental representative bodies. In the elections to the Sejm and the Senate of 1922, all the Jews in the city went under the national minority block, which had the number sixteen. In later elections, the [various] Jewish parties put up their own [separate] slates.

On March 4, 1928, Pilsudski stood for election to the Sejm and the Senate, after having taken power with the force of his military, and also wanted to have, so to speak, a parliamentary majority. For this purpose, a non-partisan government block was created, in which all of the minorities were included. Deputy Wiszlycki, among others, was elected from this slate.

The block called itself Sanacja, or B.B.W.R.[1] They were listed in the election under Number one.

Many Jews were drawn into this election work, to enable Jews to be elected, and also so in our town.

And, indeed, in each election, they were able to get a meaningful number of candidates elected, in which much was accomplished because of the proximity to Galicia, who were accustomed to voting for the ‘sitting government.’

However, after Pilsudski's death, his heirs, the ‘colonels,’ took on a more manifest anti-Semitic direction, the situation becoming keenest when Colonel Katz organized the AZAN.

[Page 242]

In general, Jews were drawn to the elections passively, but despite this, a specific group could be found which assisted in finding votes for the AZAN, as the results demonstrate to us.

Community Elections

|

|

Up to the time that Poland became independent, there had never been elections for community representatives, on a democratic basis for ‘Dozors’ as they were called among us. The ‘powers,’ in partnership with the authorities, found ways not to let the force of rule out of their hands.

Communities, in fact, only first started to organize themselves under Polish rule, and despite the fact that the new law anticipated an immediate organization of the Jewish community (paragraph 709 of March 17, 1921) the Polish government did not want to give the Jews even the slightest illusion about their so-demanded ‘self-determination,’ and they deliberately postponed the elections of the community., because in the independent elections of the community, a spoor of independent thinking manifested itself, and purely Jewish issues.

After the establishment of independent Poland, the Municipal Council nominated the first Dozors, the persons of: Mendl Lejzor's (Reichenberg), Benjamin Weinberg, and Abraham Yitzhak Blonder.

The first contest between the parties took place in 1924, during which the so-called ‘community elections’ took place across all of Congress Poland. Despite the fact that the community bore both in theory and in practice, the stamp of a very obvious religious character, not a single party chose to forego the opportunity to field candidates, and take part in the elections, so that even the Bund took part.

Each [political] coterie wanted to demonstrate its strength on the Jewish street, which, in turn, would create authority and visibility for them, as well as providing them with the possibility of utilizing the community platform as a propaganda vehicle for their own party. At that time, people carried out, and still believed in, party dogmas.

Because of this, the contest was stubborn and sullen. One fought hard and bitterly for each and every vote. The party agitators did not stop at anything, especially the representatives of the parties for whom the majority of its members were the younger people, most of which had not yet even reached the age of majority, where they could vote, who had to seek votes among those who were not fully informed, and the non-oriented masses. The principal battle took place over the common people of the streets. All manner of wonderful promises were made to them, such as lowering the fee for ritual slaughter, repealing the payment for entry to the mikva, or the baths, and other demagogic sort of ‘solutions,’ which the leaders, knew, because of the conditions in Tomaszow, constituted a utopia that would never come to pass, but what will one not do to obtain the seat of a Dozor in the Municipal Council.

Despite all of this, one could foresee a substantive victory for the Agudah, which united all of the Hasidim and Orthodox in the city. However, because, at the last minute, the Belz and Chelm Hasidim joined forces with the Hevra Kadisha, and put up an independent slate, the situation changed. The result was the following:

[Page 243]

| Agudah – | 5 Seats |

| Belz – | 1 Seat |

| Mizrahi – | 1 Seat |

| General Zionists – | 1 Seat |

| Manual Trades – | 3 Seats |

| Bund – | 1 Seat |

They were elected to the council that consisted of 12 members, and from among those elected, they formed a leadership, consisting of 8 members, which, in fact, carried out the activities of the community.

I wish to refresh my memory, and to provide a list of the people who were elected, or assumed the office after the resignation of their predecessors. I am, however, not certain that I am providing a complete list, because of the force of forgetfulness, and I beg those omitted for their pardon.

I am also not making a separate list of membership in the council or its leadership. The list entails more terms of the council and the leadership.

Agudah: David Weitzman, Ary' Heller, Mikhl Yuda Lehrer, Pinchas Zilbergeld, Yehoshua Goldstein, Mikhl Yuda Pflug, David Schwindler, Neta Heller, Yitzhak Meir Gartler, and Joseph Friedlander (son of Yerakhmiel).

Mizrahi: Lejzor Lederkremmer, Sholom Zilberman, and Mordechai Ratzimer

General Zionists: Avigdor Eidelsberg, Yitzhak Borenstein, Yitzhak Lederkremmer, and Moshe Reichenberg.

Belz – Hevra Kadisha: Mendl Reichenberg, Baruch Szparer, and Yud'l Ader.

Bund: Nahum Schuldiner.

Trade Union: Yekhezkiel Kaffenbaum, Meir Bumer, Hirsch Meir Cyment, Joseph Grohman, Shmuel Shiflinger, and Eli' Stralzer.

In the election of a President, all of the parties united with the Belz Hasidim, and elected Lejzor Lederkremmer (Mizrahi) as the President.

In the first honeymoon years, each meeting attracted a large audience of attendees, with meetings conducted just like matters of general parliamentary matters, with reading of declarations by each of the party representatives, his wish and regards, that the community fulfill the desires of his party, in which the Bund sought to free humanity from fascism… or to come out with a sharp attack against the clergy…

Before the term of the first elected officials came to an end, a number of the party politicians argued before the authorities, to diminish the size of the body, meaning, that instead of a council and a leadership [committee] that the body consist only of a group of eight people.

In the later elections, the public had already lost a bit of its interest. Very heated engagements took place among the parties at each election.

[Page 244]

Shmuel Shiflinger was elected as the community President., who held the office of President for almost the entire time, up to the last term, when Chaim Joseph Lehrer (Mizrahi) was elected, who held the position to the very end. R' Itcheh Meir Gartler held the position of President for a certain period of time as well.

Municipal Council ElectionsHere, the parties really spread their hands far apart. The council consisted of twenty-four members. Jews were a majority of the general city population. There was something from which deals could be cut. In the first elections, Jews achieved a clear majority, because of which, by law, the Jews were entitled to the position of Burgomaster (or Mayor). However, under pressure from the Starosta, Wielonowsky (incidentally, a convert to Christianity, Grossman from Bochnia) the Jews voluntarily stepped back from this position in favor of the Polish population, and with their help, Mr. Logowski was elected, a landowner and former anti-Semite, but later he was a very liberal person. He raised a homeless Jewish child, and paid tuition for him. Later on, the child received a surname: Lejzor Logowski.

The Poles, however, did not want to depend on the good will of the Jews, and later on, the Interior Minister amalgamated all of the nearby villages through a special decree (with a privilege that would remain with the smaller villages) and in this manner, gerrymandered a gentile majority. Despite this, the Jews had fifty percent of the council membership.

However, in order to elect the burgomaster, nobody had any ideas. Only the Starosta imposed a retired colonel from the Sanacja.

by Neta Eisen (A. Roum)

|

|

Abraham Unterbukh, Szparer, Zelig Pomerantz, Naphtali Messer, Shmuel Boxenbaum, Yerucham Munster, and Nathan Szparer |

The following rule applies: what has happened in the past, everything that has gone by, and no longer is, except – as is understood – the gruesome death of our near and dear ones, all of this later reappears so interesting in our memory, so fecund, so touching.

Even difficult personal experiences, and profound human suffering, is illuminated by a stark and pure candle of nostalgia of an idealized past. That is the nature of the human heart: It loves, and longs for that which once existed, and has gone forever, even when the present is better, more comfortable, and brighter than yesterday.

In reality, there is nothing new here. That ‘past,’ was our childhood, our youth, our innocent world of dreams and aspirations. So what is the wonder that we yearn for it, yet again? That from which our memory draws buckets

[Page 245]

overflowing with delight, longing and tranquility?

I often admit to myself, that from the day that I achieved the ability to reason and understand – and to my joy or sorrow – that was very early on, I strove mightily with all my strength to flee our town. I was beset with want, the flighty forms of making a living, the insecurity with which the Jews had to live. But entirely apart, what troubled me was the idleness, the hopelessness of the young people, of the boys and girls, that loitered about empty-handed, with nothing to do, and lived with a perpetual fear of what tomorrow might bring.

I personally was tortured by a sharp contradictory inner feeling that burned inside of me: on the one side, I deeply loved the land, meaning the fields, forests, rivers, the beautiful frosty moonlit nights, in the winter, the rich, invigorating early morning of the Polish autumn; I drank thirstily from the sources of Polish literature and poetry, and I even loved the Polish man, and I was prepared to forgive him. On the other side, again, I felt like I was passing over an alien territory, that I live among an unfamiliar and hostile nation, that there is no resolution or hope coming tomorrow, and it will be darker than yesterday, and the further one proceeded, the worse it would become. It was in those sleepless nights, and restless days for doubt and struggle, of contradiction and suffering, that my Zionist revelation was born, and took me onto different roads and ways.

Such is fate.

As I said, I derived little pleasure from my home town. I was dissatisfied with everything, despite the fact that I did not hold anyone responsible for this situation. Such was our plight. The curse had been poured out over it, just like it had been poured out over all the other Jewish cities and towns in Poland.

But it is interesting, that the further I distanced myself from Tomaszow both in distance and in time, all the more did the good, and beautiful times in the city materialize before me, the genuine virtues of its Jewish residents, the interesting content-rich social and cultural-spiritual life.

Paying no mind to the difficult and bitter struggle of earning a bit of bread to eat, for sustenance; paying no mind to the economic want, and the hostility of the environment, causing the Jews to have to run their lives like a captive country within a country, from a national and spiritual standpoint. The Jews, as a rule, were untied by a common language, with their own holidays, with their personal traditions, with obligations and mutual assistance, in short: despite the fact that we lived in a strange land, and under a foreign ruler, we guarded our own national Jewish identity, our spiritual inheritance, and continued to spin the thread of Jewish survival and Jewish continuity and Jewish vitality.

It total, several thousand Jewish families lived in Tomaszow. It was a small Jewish community, but it conducted its Jewish and spiritual life rich in color, and dynamically. Across the omnipresent Tomaszow sky, was spread the rainbow of all the concepts, possibilities, and ideals that in the first decades of the twentieth century dominated the Jewish polity, if not the entire world.

Ardent Hasidim and self-made freethinkers; adherents of Mizrahi and those of the Agudah, and communists, Zionists, Bundists, adherents of the Sejm, territorialists, and even anarchists. One could find someone from all of these persuasions in the tiny Jewish settlement of Tomaszow. And each of these believed in their own way, in their own ideal, each read and studies; [each] agitated and fought stubbornly and with commitment for the victory of their particular beliefs. Today, it would not be believed that such a thing would be possible,

[Page 246]

or even existed. Truthfully, we all went hunger, and the solitude and need was not minor. Everyone created a different world of their own, a spiritual one, a conceptual one, in which he felt free and without fear, and it served as a form of refuge from the plight of reality, and as a harbinger of a better future. There were so much spiritual energy, so many beautiful dreams about humanity's love for one another, of the unity of nations; so much longing and a dream of personal resolution, and salvation for the [Jewish] people, that was invested in the Jewish children, in the Jewish youth, and in every Jew in Tomaszow!

Until [the decade of] the thirties, of the present century, I was bound and tied to all parts of the Jewish community in Tomaszow, with young and old alike, with the faithful and non-believers, with simple people from the masses, with Zionists, and Bundists, with everything and everyone. I see them all before my eyes, downtrodden and proud; listless and feisty; poor in material goods, and rich in spirit; resigned and hopeless. All pass by, as if in a kaleidoscope. Tomaszow did not have the privilege of producing Gaonim. I think that it is hard to find even a single Jew, whose fame transcended the borders of that very city. As a result, the oversight has granted me a boon:

The summation of worth and virtues between each, jointly and severally was certainly more accurate and possibly more necessary.

There once was a Jewish Tomaszow that had within it suffering and happiness, with the creation of faith and hope.

It was – and is no more!

by Sh. Licht

The theme is both broad and deep, as our Torah says, from time immemorial, with the heavenly dictum: ‘man lives not by bread alone.’ If he desires a life of substance, a spiritual satisfaction with his existence, then he must have some purpose, a goal, and ideal, which will endow him with strength to negotiate the twists and turns of life, and avoid falling of the path in a material sense, so that he should not fall so low, and not go so high, that he should earn something that contains his worth, in today's parlance, a vitamin of life – in the best sense.

I do not have it in my mind to write an historical treatment of the high spiritual plane of Tomaszow Jewry, since its establishment. We can take pride, when 350 years ago, when many Jewish settlements in Poland were still raw, and undeveloped, barely able to assemble a prayer quorum, many of which had an appointed clergy serving simultaneously in the six functions of Rabbi, Cantor, Shokhet, Melamed, Mohel and Shammes, Tomaszow already had a thriving Jewish settlement, with the greatest of the Gaonim of that era, as Rabbis and Headmasters of Yeshivas. It is worth recalling our own, such as the Gaon, Rabbi Mordechai a brother of the Rabbi of Cracow, the author of ‘Maginei Shlomo,’ and ‘Pnei Yehoshua,’ martyred in the year T”AT [1649], the Gaon, Rabbi Yaakov son of R' Fyvel, the Rabbi and Yeshiva Headmaster in Tomaszow, and later in Lutsk, the Gaon Rabbi Yehuda son of R' Nissan, a disciple of the Maharsh”l and Maharsh”a, and later the Rabbi of Kalisz, the author of ‘Bet Yehuda,’ was the Rabbi of Tomaszow in the year 5414 [1654], from whose Yeshiva, there came the great scholars of that generation, and the most eminent of the Rabbis of that

[Page 247]

time. Such a work would take me too far afield, and later on there were the various Rabbis of Kotzk, and Jarczow, etc. I only wish to concentrate on the later era, the one that we [personally] remember, or that we heard about from our parents, about times through which they personally lived.

The Spiritual Nourishment of the Last EraAnd one wants to deal with the question of what was the spiritual nourishment of our brethren, the Jewish people, in the Tomaszow community in our time and yours?

In order to suitably and accurately deal with this subject, I must divide the answer into two parts:

First: Up to The First World War; and second, after The First World War.

This is because the war not only changes the borders of countries and nations in general, but also created a new comprehension, a new look at life and the world. It simply revolted against the entire old order of Jewish life and thought. In order to be more specific and realistic, the period before The First World War needs to be divided [also] into two parts: Up to the year 1905, and from 1905 to 1914, that is, the outbreak of the war.

The Spiritual Situation Up To 1905And so, let us go in [chronological] order. Up until the year 1905, our Tomaszow Jews lived with a way of life, and customs, of their ancestors. The foundation of their lives was the holy faith, and the construct of their lives, whether in private life, or in public, was shot through and interwoven with all of the stringent rules of the Shulkhan Arukh, the laws of the Torah, were the forces that shaped individual and public life. There was no distinction between rich and poor, between a merchant or a laborer; all had one goal, and all had one purpose: it was to observe all the dictates of the Torah in theory and in practice, and the importance of an individual was measured by the caliber of Torah knowledge, or according to his piety, and charitableness. The more learned and honest a Jew was, the more respect he obtained. In a large sense, Yiddishkeit, in the last century, strengthened itself because of the influence of Hasidism, which rooted itself powerfully in Tomaszow. It refreshed, re-energized and infused commitment and energy, joy and liveliness, self-strengthening, self-reliance, energy and revitalization. The common people were especially uplifted. The greatest wish that a mother and father could have was to raise children who would become Torah scholars, and God-fearing people.

Jews prayed morning and night, in a minyan, and tried to take in a bit of study each according to their own means. Even the low level manual laborers, who because of their impoverished means had to go to work in their early youth in order to earn a living, had their own Rabbi who studied Eyn Yaakov and the Mishna with them. True, one found unlettered people, an ignoramus, and even those who transgressed the laws, but this was only the occasional individual, without any ideological underpinnings, or organized only mostly by appetites, driven by base lusts, and instincts, or it was because of difficult circumstances and tribulations that a person came to grief. The Haskalah, which in neighboring Zamość and Szczebrzeszyn, had such giants as Yaakov Reifman, Sh. David Schiffman the original Peretz, and other phenomenal people, appeared to touch the integrity of Judaism, the original Yiddishkeit in Tomaszow. As I see it, the formidable bulwark of Hasidim in Tomaszow helped [sic: as a barrier]. To begin with, there were no Mitnagdim, or as they were

[Page 248]

called, ‘the worldly Lithuanian Jews,’ only Hasidim, balebatim, and simple Jews, that class later to be designated as ‘the masses,’ which consisted of poorer craftsmen, village itinerants, and a certain level of small scale storekeepers.

There was never any talk of secular education. Certain Jews (especially from the wealthier merchant class, could read and write the language of the land, and could do calculations to the extent that was required in commerce. And even that was learned only through private tutoring who themselves were very observant Jews with a full beard and side locks. The greatest emphasis was placed on sacred studies, Shas and its commentaries. Almost nobody attended the municipal school. One had little interaction with non-Jewish neighbors even if they might have been the best customer, or neighbor. The Hasidic Jews would add to this the study of Hasidic texts, such as Noam Elimelekh, Kedushat Levi, and Avodat Yisrael, and the books of the Rabbi of Lublin. The more modern would make use of the research text, such as ‘the Guide to the Perplexed,’ Baal Akeda, Kuzari, or later on, Sefer HaBrit, and studied the Tanakh with Malbim.[1]

One hundred percent of the population knew Hebrew and how to pray. Being able to sign one's name, and use Yiddish, by about 80 percent. This was at a time when 80 percent of the non-Jewish population was illiterate.

Life proceeded monotonously. Nobody missed morning and evening prayers, and only the more refined would study on a daily basis, each in according to their station and capacity to learn. Hasidim would also fulfil this obligation with an Hasidic conversation, or the telling of a Rabbinical tale. In the Bet HaMedrash of the lesser-educated, the so-called ‘itinerant preachers’ would come around, and the common people would eat them up, in particular the ‘parables.’ And if a dispute arose, which regrettably was not in short supply, there was fresh news every day. There were ‘private tutors’ in the city, and a municipal Talmud Torah, for the poorer children. There was a Russian school in the city for elementary education, but not everyone sent their children there. From among the Jews, almost nobody. Jews lived together with Poles and Russians, and dealt with them on a daily basis, but did not have any relationship with them. And this was not only religious, but also culturally there were two separate, or even better said, opposing worlds. Most of the Jews did not speak the native language, and it was in this manner that entire generations were raised, a generation going, a [new] generation coming, and the Jews remained the same stubborn adherents to their original Yiddishkeit.

New CurrentsBy the end of the nineteenth century, fresh new people took up residence in Tomaszow, who had come from very far away. Modern people, nursed at the bosom of the Haskalah, these were the contractors and forest merchants. In their homes, the language of discourse was only Russian, and it was under their influence and pressure that the Litvak, Rabbi Shidkovsky was retained, first in the capacity of ‘Kozioner Rabbiner’ and later as the Rabbi of the city. The ambience of his home was very close to the new currents, and they also drew in the young Hasidim to the extent that a circle of ‘modern youth’ began to form, to learn Russian, read a newspaper, or a pamphlet. The [newspaper] HaTzefira, began to make an appearance in Jewish homes, and brought in a bit of ‘Enlightenment’ and sowed the first seeds of Zionism. In 1905, with the outbreak of the

[Page 249]

Russo-Japanese War, and the first signs of revolution, the Russian Empire, in general, underwent a shock, and with it, all the old foundations under the Jews also began to wobble and shake, taking into account the newly arrived balebatim, the modern Russian Jews. Among some of those who were inoculated with the ‘Zamość Haskalah,’ there were those who derived some satisfaction from sneaking a pamphlet to a young Hasidic boy or girl, to the extent, that in 1910 the first Jewish library was founded through the help of a Mr. Maiman, but it did not exist for long. A couple of observant Jews, together with R' Mordechai Joseph Milchiger ע”ה at their head, entered at night, and tore up and burned all of the books, and demolished the local. The Russian authorities took pleasure in this, and remained silent. A general community Zionist organization began to blossom and develop, but it did not achieve realization. It was in this fashion that life continued until the outbreak of the war in 1914.

The Spiritual RevolutionDuring the time of the First World War, which brought destruction, hunger and want, nobody had community activities in mind. It was only at the end of the war, that a variety of parties, and circles began to appear, especially after the war, with the establishment of an independent Poland. Among many, it elicited hoped for new opportunities to exist in the same place. They were blinded by the paper-based liberation documents that put forth ideas of proletarians and Bundists, that suggested that here, in Poland, was our future, and it is hear that we must battle out our rights and this is our home. They called for unification with and fraternization with the Poles, whose destiny was seen to be one we shared in common, and actually, that spiritual barrier [between us] began, slowly, to disappear. This was not from the part of the gentiles to the Jews, but rather from the Jews to the gentiles. This was for the most part, what the liberation of enslaved lands elicited from them a pent up zeal, and awakened a national pride, especially after the Balfour Declaration. Jews became enthusiastically in favor of the rebuilding of the Land of Israel, a ray of hope for their own independent national homeland, a land of their own that Jews craved and longed for, for thousands of years. It was this, which drew large groups into the Zionist organizations, in all of its forms, and in all of its nuances, from the Mizrahi to the HaShomer HaTza'ir, and left-wing Poalei Tzion.

New winds began to blow through the Jewish street, and began to penetrate almost all the houses, breaking down all barriers and impediments. The party was placed higher that all else, even family interests. [Reading] Pamphlets and newspapers became a daily activity, speeches and get-togethers were often occurrences. Libraries and drama circles were created, sports clubs, and in general, the participation in all these things brought dereliction, and the yoke, of the Torah and its commandments, was discarded. Not everyone with the same tempo in Tomaszow, but the old foundations of Yiddishkeit were shattered, and the gap between one generation and the next became wider and deeper. Orthodoxy had been broken and beaten. The shtiblakh were practically empty of the young people. Every new party or ideal, when it first looked to obtain candidates, it was from the ‘Orthodox camp.’ Until the Agudah was established. But this helped only minimally, until the Cieszanow Rebbe took up residence in our city. He raised the spirit especially of the young orthodox, instilling them with energy and pride. And he raised an aware Hasidic youth, who were no longer torn away and swept along with the modern current. Rather, here were proud, energetic young people and young boys, and it was in this way, more, or less, into which life settled.

[Page 250]

|

|

The older generation, meaning age 40 and up, was one hundred percent religious, drawing its spiritual sustenance from the ancient Jewish storehouse, a Gemara, Mishna, a Hasidic book, etc. However, a larger percentage of them, already read a newspaper on a daily basis, and many of them were seduced by ‘Heint,’ or ‘Moment,’ Zionist periodicals overloaded with irreligious content. The very observant and the ‘Agudah’ people read ‘Der Jude,’ and later on, ‘Tageblatt.’ Even though they personally didn't need to, they took it into their homes, to block an excuse for their children to buy a second paper. Reading did not come easily. Part of the people had the paper for only an hour, and a part only on the morning of the following day, or even the next day, because 6-8 people subscribed to one copy, but the paper was read from beginning o end. And when it came to party matters, one lived it, as if it were a personal experience.

From 25-40 those who were ‘liberated’ had a good savvy and were aware. Among the younger generation, almost 50% were already ‘liberated.’ In this category, what it meant in our context was, people who did not observe Torah laws, meaning they permit themselves to ignore the Torah. The sense of the 3-day-a-year Jew, where being religious meant coming to synagogue on Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, did not exist for us (with the exception of the doctor). If he was not religious he never went at all. There were no people in the town who violated the Sabbath publicly, because all businesses and laborers didn't work, with the exception of the hairdressers. However, in some of the party offices, where the Bund, or left-wing Poalei Tzion or the Jewish Labor Party, known under the acronym AYAP, could be found, the violation of the Sabbath was (practically) a part of party life.

But even the substantive cosmopolitan parties, did not officially adopt a policy of violating the Sabbath. Especially the pioneering youth. The reason was that it represented an expression of parting with the old and idle way of life.

Not everyone read books, but everyone carried a pamphlet ‘under the arm,’ because this created the appearance of ‘enlightenment,’ and being modern. Almost a majority of the Jewish children in the city were already attending the Powszecna Szkola, yet only a rather small percentage went on to the gymnasium. Yiddish was the daily language of discourse, even among the young people, and nobody subscribed to a Polish periodical. Even the Bund made do with the ‘Volks Zeitung.’ It was only in the thirties that Polish began to penetrate into the Jewish homes. The small percentage of Jews, who attended gymnasium, already spoke only Polish. The young intelligentsia also spoke in Polish, and this continued to spread. The ‘Khvalyeh’ from Lemberg, and the ‘Nasz Przeglad’ from Warsaw (Zionist periodicals in the Polish language), were being read for about a year, and became widely disseminated. Orthodox youth was divided into three parts: Mizrahi, Agudah, and unaffiliated. The national-religious youth concentrated itself in Mizrahi, into two groups, ‘Torah V'Avodah’ and ‘Shomer HaDati,’ but by and large they didn't have any staying power, because in the main, it served as a bridge to pass on to the more liberal camps. But in any event, they derived benefits from both worlds… mixed membership of boys and girls, studying little, and rarely was any of them from those who attended the Bet HaMedrash. They were keepers of the faith, which is why they took the name ‘Shomer HaDati.’

The Agudah youth were the zealots, young men who studied all day. Even the sons of merchants also had lessons in the morning and the evening. However, the newspapers, and the various periodicals, such as ‘Darkeynu,’ ‘Jugend Blätter,’ ‘Bet Yaakov’ journal, stole from the time available for Torah study. They

[Page 251]

reasoned, however, that they needed this to arm themselves with the principles of the Agudah, so that they would not be called ignoramuses. It was either that, or they simply found the reading of interest to them… The unaffiliated were a small percentage, and from year to year, Yiddishkeit in general grew weaker. Despite the fact that there was no official violator of the Sabbath, and Kashrut was observed in all the homes, and there were only a few exceptions to the observance of ritual family purity. However, in general, this was the observance of instructed people, and the young always went further away. It is true that this was brought about by the special limitations pertaining to Jews. They were frustrated and embittered people, and this created barriers for them along many paths. They simply wanted to run away from themselves.

Also the hatred of the faith was very strong with many, and in general, the party played a great role not only in public life, but also in shaping the spiritual persona of each individual.

And in each party, there were to be found such idealists, who placed the party's interests above their own private interests. In any case, Polish Jewry, of which our city was a part, exhausted itself in spiritual convulsions, and continued to alter its spiritual appearance from year to year.

|

|

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 02 Jun 2023 by JH