|

|

|

[Page 2]

|

|

And I will avenge their blood which I have not avenged.

(Joel 4:21)

The chronicle of the shtetl of Ternivka that will be related below was written from memory only. I heard many of the events that will be related from my ancestors of blessed memory and from the elders of the shtetl. I myself was an eyewitness to many of the events. I also received from reliable people, natives of the shtetl, feedback on events that occurred in the shtetl after I immigrated to Israel (1920).

As the “Last of the Mohicans” who still lives in his spirit and memory shtetl life and its history (the vast majority of Ternivkers who are still living today in Israel and abroad left the shtetl as children so the events that occurred in the shtetl are not at all clear to them), I decided to relate on these pages the history of the shtetl in which the cruel Nazi enemy annihilated both young and old.

May these words about Ternivka serve as a testimonial and a memorial to the pure souls who died at the hands of human beasts. May God avenge their blood.

Most of the events related here are not in chronological order but are arranged according to subject matter so sometimes earlier events appear after later events because we do not recall our memories in chronological order.

Unfortunately, I don't have any photos to accompany the text that would portray shtetl life, its institutions and personalities. I only have personal family photos that don't at all portray shtetl life.

As far as I can remember, shtetl life and its institutions were never “immortalized” in photos but instead were “immortalized” in events and activities.

G. Bar–Tzvi (Wortman)

Tel Aviv, Israel's 22nd Independence day, 5th day of Iyyar, 5730 (May 11, 1970)

The First Edition of Our Shtetl Ternivka that appeared in 5730 (1970) in a limited number of copies and was well received by the critics in the newspapers Davar, Yeda–Am, Forverts and Der Tog sold out completely. Therefore the publishers, the Ternivka Landsmanschaft, decided to publish a Second Edition of this book.

And because, since the publishing of the First Edition, I have remembered more events, activities and personalities of the shtetl, I have also put them to paper and they are appearing here in this Second Edition for the first time.

In this expanded edition 20 new chapters have therefore been added and fitted in according to their subject matter and content. Those additional chapters have been marked with an asterisk in the Table of Contents.

It is clear that even with the addition of these chapters the whole story of this humble shtetl, its vibrant atmosphere and its unique nature, has not been told. But even in the “shaded ember” of these memories, the shtetl of Ternivka is reflected in all of her charm and innocence right up until her bitter end (1942).

G. Bar–Tzvi (Wortman)

Tel Aviv, Israel's 24th Independence Day, 5th day of Iyyar, 5732 (April 19, 1972)

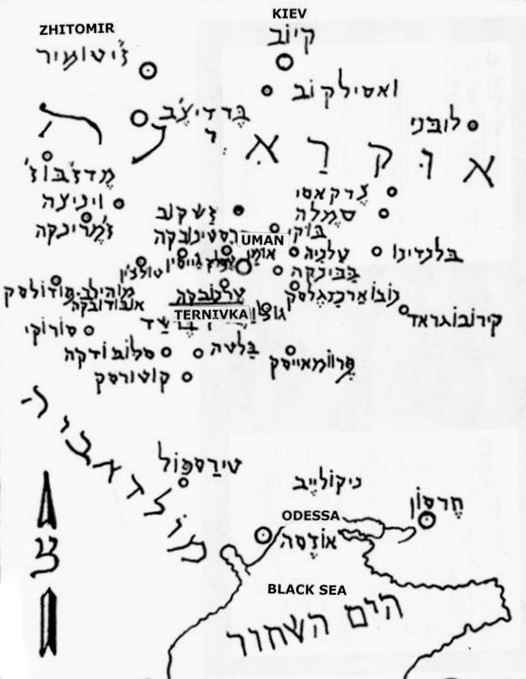

The shtetl of Ternivka, which was in the Province of Podolia (Podolia Guberniya) and on the border with the Province of Kiev (Kiev Guberniya), belonged to Kiev Oblast during the Soviet period (I believe that it may actually have belonged to Vinnitsa Oblast as it is today). It is surmised that it was called Ternivka after the low prickly bush “Tern” or “Ternovnik” (Prunus spinosa) that was widespread in the area. This bush produces small fruit about the size of a cherry, bluish and edible. The people called the fruit “tarn.” It would appear that the word Ternivka is derived from there.

According to tradition, the shtetl was established in the year 1813 and this is how it happened. In the District of Uman (Uman Uyezd) there was a tiny shtetl called Bosivka on land owned by a Polish landlord (Bosivka is about 30 miles north of Ternivka).

One day there was an important wedding. The young prodigy, 18 year old Yankele (Ya'akov), who had already been ordained as a Rabbi and was the son of Rabbi Avraham Wortman, Rabbi of the community, was entering into a life of marriage and the doing of good deeds with the daughter of the Chasidic Rebbe, Rabbi Refa'el of Bershad (1751–1827), an outstanding disciple of the Chasidic Rebbe, Rabbi Pinchas of Koretz (1726–1790), a close disciple of the Ba'al Shem Tov (the founder of Chasidism, ca. 1700–1760).

All of the Jews of Bosivka participated in this joyful event and sang and danced all across the shtetl. Just at that time, it happened that the Polish landowner, who was a zealous Catholic and a hater of Jews, passed by and when he saw his “Moshkes,” the Jews, joyful and happy, dancing and singing in public view on “his land,” he was filled with anger and rage and decreed that his servants, the doers of his will, destroy the homes of the “Zhidi” (Jews) because of this “impertinence.”

In those days, the decree of a landowner was like a royal decree and much to the horror and shock of the frightened and frantic Jews, the cruel and insane decree issued by the landowner was quickly carried out despite the pleading and the weeping of the Jews of Bosivka. After the destruction of their homes these wretched souls had no choice but to take their children, their wives and their possessions and wander to another place in order to put a roof over their heads.

[Page 7]

About half of the shtetl of Bosivka, which had about 100 families, moved to the neighboring shtetl of “Rachmistrivka” (Rotmistrivka was in fact about 90 miles ENE of Bosivka) and Rabbi Avraham Wortman (the Rabbi of the Jews of Bosivka) with the permission of the local Rabbi, was the Rabbi of the Jews of Bosivka who settled there. The rest of the refugee families spread out among other shtetls – Monastyrishche, Talne, Tulchin and other shtetls.

The “Yeshiva” (seminary) student Rabbi Ya'akov Wortman urged his fellow “Yeshiva” students to go somewhere else and found a new shtetl rather than settle in a shtetl that already existed. His heartfelt and convincing words and the esteem in which he was held persuaded them and about 20 “Yeshiva” students went with him and arrived at the lands of the estate of Ternivka.

When these wanderers stood before the “Puritz” (landowner) and asked his permission to settle on his land and establish a Jewish community there, he willingly agreed because he knew well that the diligent and talented Jews would help him to develop his estate and increase his revenue. He set aside for these Bosivka refugees a plot of land on which to build their homes and establish a Jewish community, a Jewish shtetl. That is how the shtetl of Ternivka came into being. And Rabbi Ya'akov Wortman, who was among its promoters and founders, was its first Rabbi and spiritual advisor. As previously mentioned, this happened in 1813.

This small settlement developed over many years and became a large shtetl because over the years it absorbed more Jews. It would seem that the town was preplanned on engineering principles. All of its streets were as straight as a ruler and parallel to one another. There was only one street across the breadth of the shtetl and it connected a few main streets. There were even a few streets that were paved with flagstones. Only Jews lived in the shtetl itself and surrounding it was the village of Ternivka where the Ukrainian farmers lived. About 4,000 Jews lived in Ternivka at the outbreak of the First World War (1914).

The community of Ternivka conducted itself on calm waters. There was no fuss and no bother. Jews made a living somehow, made do with little and worshipped their Creator with love and awe. But during Rabbi Ya'akov Wortman's elder years the skies over the shtetl grew dark, brewing a strong storm of emotions.

And this is what happened. The Rabbi of the community, Rabbi Ya'akov, was not only the son–in–law of the Chasidic Rebbe, Rabbi Refa'el of Bershad (for decades Rabbi Ya'akov and his family celebrated the first two days of Passover [the Seders] with Rabbi Refa'el of Bershad until Rabbi Refa'el passed away [1827]). He was also a long–time and distinguished disciple.

The Chasidism of Bershad distinguished itself by its simplicity, its modesty and its innocence, its level of humility and its great love for truth. Rabbi Refa'el practised what he preached. He lived a life of simplicity and scarcity unlike the Chasidic Rebbes of Ruzhin, Talne and others who lived lives of splendor and opulence, lives of wealth and luxury, like landowners, living in luxurious palaces and traveling in splendid carriages pulled by prancing horses, wearing the finest silks and using dishes of silver and gold.

Rabbi Ya'akov with his modest and moral ways was greatly admired by the Jews of the shtetl and even by the non–Jews who considered him a man of God, a holy man. Most of the Jews of Ternivka were also followers of the Chasidic Rebbe, Rabbi Refa'el of Bershad. But a certain assertive man in the shtetl by the name of Zaks who was friendly with the “Puritz” (landowner) and with those in power was of course a follower of the Chasidic Rebbe of Talne because this Chasidic Rebbe, like Rabbi Judah the Prince (a 3rd Century CE Rabbi), paid homage to rich men.

One day Rabbi Duvidl of Talne (Rabbi David Twersky, 1808–1882) came to Ternivka to visit his flock, his few but rich and assertive followers. Rabbi Ya'akov, even though he was elderly and advanced in years (about 70 years old) and even though, as mentioned before, he was not a follower of the Chasidic Rebbe of Talne, saw it his duty as the Rabbi of the community to greet the respected visitor who was descended from a distinguished family and the grandson of the Chasidic Rebbe of Chernobyl (Rabbi Menachem Nachum Twersky, 1730–1797) may his merit protect us.

When Rabbi Ya'akov came to the inn where Rabbi Duvidl of Talne was staying (it was the inn of the rich and assertive Zaks where mostly landowners and government officials would stay) in order to greet and welcome him, he saw to his great astonishment, and woe to those eyes that behold such a thing, that the collar of the shirt of Rabbi Duvidl of Talne was not fastened with a lace according to the custom of proper Chasidic Jews but was buttoned with a button according to the custom of landowners, God forbid.

[Page 9]

|

|

It is dated Sunday, the 18th day of Iyyar (Lag Ba'Omer), 5581 (May 20, 1821). |

[Page 10]

|

|

[Page 11]

“Woe is me,” Rabbi Ya'akov deeply sighed, “the grandson of the Chasidic Rebbe of Chernobyl is transgressing ‘you must not follow their customs’ (Leviticus 18:3) and buttons the collar of his shirt in the way that the evil landowners do!” These words of admonition were said in the presence of the followers of the Chasidic Rebbe of Talne.

The clever Rabbi Duvidl remained silent and swallowed his pride and did not respond. After all, he (Rabbi Duvidl) was a relative youngster (about 58 years old) compared with the elderly Rabbi Ya'akov (about 70 years old) who was one of the greatest disciples of the Chasidic Rebbe of Bershad. But Rabbi Duvidl remembered this insult and when he returned to Talne he decided to avenge this insult and he sent a Rabbi from among his followers to Ternivka to replace Rabbi Ya'akov as Rabbi of the community.

When this became known in the shtetl, it created a huge storm of protest and the majority revolted against this shameful act, but the assertive Zaks, who as mentioned before, was close to the “Puritz” (landlowner) and to those in power and other followers of the Chasidic Rebbe of Talne, rich and assertive men, paid no attention to the protests of the masses and appointed the new Rabbi, Rabbi Hirsch, Rabbi of the community against their will. By the way, this Rabbi (Rabbi Hirsch) was the grandfather of the Hebrew writer, Micha–Yosef Berdichevsky/Bin–Gorion (1865–1921).

When the humble Rabbi Ya'akov saw that God's name was being desecrated and that a great controversy might erupt, God forbid, with unforeseeable consequences, he decided to relent and to leave the shtetl and the community rabbinate and to immigrate to the Holy Land. With no alternative, the community accepted this and even took it upon itself, of its own good will, to send to Rabbi Ya'akov, for the duration of his life, the salary that he was receiving as the Rabbi of Ternivka.

On the day that Rabbi Ya'akov left the shtetl for the Land of Israel (in 1865), all the stores and the workshops were closed and all of the inhabitants, both young and old, accompanied him for a short distance. When they returned to their homes there was a sudden downpour of rain. The inhabitants of the shtetl then said: “Even the heavens are weeping over the departure of a saint from the town, as our sages of blessed memory have said: ‘When a saint departs from a city, its splendor and glory also depart.’”

Rabbi Ya'akov's journey to the Land of Israel took many weeks and when he arrived in the Land of Israel after a difficult journey, he decided to settle in Tzefat, one of the Four Holy Cities of the Land of Israel (Jerusalem, Tzefat, Tiberias and Hebron), the city of the “Kabbala” (Jewish mysticism) and the “ARI” (Rabbi Yitzchak Luria [1534–1572]). There he bought himself a small house and gathered around him a few “Yeshiva” (seminary) students and taught them at no charge the Torah and reverence for God. By the way, once, his wife (his second) was walking in the streets of Tzefat and an Arab who was passing by on a donkey hit her with his club, for no good reason, and she fell down and died.

[Page 12]

Fifty–five years after Rabbi Ya'akov Wortman immigrated to the city of Safad in the Holy Land (in 1865), one of his great grandsons, the writer of these pages, immigrated to the Land of Israel as a pioneer, and he traveled to Tzefat in search of the “footprints” of his great grandfather, the Rabbi. After much searching, he succeeded in finding an elderly man by the name of Rabbi Nathan who supervised the baking of Matza (this happened close to Passover in the year 5682 [April of 1922]).

The elderly Rabbi Nathan told the great grandson that he himself was one of the “Yeshiva” students who had studied the Torah with Rabbi Ya'akov and he had much to say in his praise and about his great knowledge of the Torah. Rabbi Nathan even led the great grandson to the house of Rabbi Ya'akov. It had long ago fallen into ruin. Only partial walls and the oven of the ruined kitchen could be seen. In those days in 5682 (1922) there were many ruined houses in Tzefat, as if they had no value. Removal of the ruins would have cost more than the lot was worth.

When the elderly man was also asked to point out the grave of Rabbi Ya'akov, he apologized that he would not be able to fulfill this request since a long time had elapsed since Rabbi Ya'akov had died and many old gravestones had fallen over and were broken and he no longer remembered the place of burial of his Rabbi, Rabbi Ya'akov, because he hadn't gone to the cemetery in many years.

By the way, the “Kushan” (Ottoman deed of property) for the house that Rabbi Ya'akov bought in Tzefat was sent for safekeeping to his descendants in Ternivka, as their “inheritance.” The deed of property was kept by his son–in–law, Simcha Koifman. After that, it was passed on to his grandsons, the Koifman brothers. Because of the Russian Revolution and the Civil War, the brothers were scattered to different places in Russia and the deed of property was lost.

Many stories and tales about Rabbi Ya'akov spread in the shtetl of Ternivka. They related that on the Sabbath it was his custom to speak only the Holy Tongue (Hebrew) because he used to say “the Holy Tongue is suitable to the Holy Sabbath.” He didn't like positions of power and would quote a saying of our sages of blessed memory, “you should hate positions of power” (Ethics of the Fathers 1:10) and he would educate his scholarly sons to be in awe of the Lord, to work and to have worldly experiences. One of them became a fisherman and the other a merchant. Rabbi Ya'akov would go from door to door and collect donations in his large, red handkerchief which he would later distribute to both Jews and non–Jews ”in the interest of peace.” He often would walk in the streets of the shtetl and help an elderly person, a woman, a child to carry their load.

[Page 13]

Part of a letter or note in the handwriting of Rabbi Ya'akov found in the family collection. Below is a printed copy of the letter.

The letter starts by mentioning that Rabbi Ya'akov stopped in the town of Tarashcha on the eve of the New Moon of Tamuz (June of 1865) on his way to the Holy Land (possibly in order to prostrate himself on the grave of his Rebbe [and father–in–law], Rabbi Refa'el of Bershad who had lived in Tarashcha towards the end of his life and had been buried there in 1827).

|

[Page 14]

It was also related that the Ukrainian man who would every year for forty years on the eve of Passover carry water in special “Passover buckets” from a distant well to the house of Rabbi Ya'akov – died suddenly in the very same year that Rabbi Ya'akov immigrated to Tzefat in the Holy Land… because by his service to Rabbi Ya'akov he had fulfilled his purpose in the world…

By the way, on Passover, those who were very strict in their Jewish observance didn't use the water that the Jewish “Vasser Treggers” (water carriers) would supply them with in their barrels because those barrels were not special “Passover barrels,” but were regular barrels in which the Jewish “Vasser Treggers” would carry water all year long and which in honor of the Passover holiday they would just “Kosher” by immersing them in boiling water.

Like most shtetls, Ternivka also existed from trade, storekeeping and handicrafts. It even had “industry.” It had a large steam driven flour mill to which the Ukrainian farmers of the surrounding area would bring their wheat to mill. It had a large and famous beer factory. This beer was famous far and wide. People would come to Ternivka from many large and distant cities and from many shtetls to buy this excellent and famous beer. There were a few different types of beer. These two successful enterprises belonged to the Koifman Brothers who were among the richest and the most respected of the shtetl.

They were among the great grandsons of Rabbi Ya'akov Wortman through their grandfather (Simcha Koifman, Rabbi Ya'akov's son–in–law). They were also large suppliers of sugar beets to the sugar factory of Brodsky (Lazar Brodsky the Jewish ”sugar baron,” 1848–1904) that was in the vicinity of Ternivka (the writer Yitzchak Norman of blessed memory who was born in Dubovo [23 miles ENE of Ternivka] worked in his youth as a clerk for the Koifmans).

There were also a few horse–powered mills that ground grits in the shtetl, a few small gins for beating and cleaning wool that the farmers would bring after the shearing of their sheep, a large seltzer water factory, two oil presses and also a Passover Matza factory. The degree to which Ternivka was a shtetl of trade and traffic is proven by this fact. There were twelve hotels and low–priced inns in this small shtetl that provided a living for their owners!

[Page 15]

Every two weeks on a Tuesday a very large “Yarid” (market day) that was “famous” in the area would be held in Ternivka. I remember one episode connected with the “Yarid” that gave testimony to the “wars of the Jews” over the issue of livelihood. The “Tandetniks,” that's what the sellers of ready–to–wear clothes, mainly to Ukrainians, were called (Jews almost never bought ready–to–wear clothes because of their plain fabrics and also because of their weak and shabby stitching) who were looking forward to the “Yarid” every two weeks were disappointed by the tents of Jewish “Tandetniks” from other shtetls who were coming to Ternivka for the “Yarid” and selling clothes cheaply, competing with the “Ternivkers” and depriving them of their livelihood.

So what did the locals do? They went and complained to the “Pristav” (Police Chief) about their difficult situation. Of course, this complaint was accompanied by a nice bribe. The “Pristav,” a clever Ukrainian, gave the “Ternivkers” this advice. Even though there was no need for the locals to set up tents to sell clothes like the outsiders since they had stores, he suggested to them that they also set up a row of tents near their stores.

On “Yarid” day when the “Pristav” passed through the different streets in order to supervise what was happening at the “Yarid” he also passed through the “Clothes Street” and when he saw the two rows of tents, of the locals and of the outsiders, he immediately ordered that all of the tents be taken down “because they were interfering with the traffic in the street.” So the tents were taken down without any complaints or back talk (of course the locals did not lose out in this matter) and from then on “Tandetniks” from outside never came to compete with the locals.

In Chapter 4 we already mentioned the Koifman brothers, among the richest and the most respected of the shtetl. The grandfather of these brothers, Simcha Koifman, married the daughter of Rabbi Ya'akov Wortman, the first rabbi of Ternivka. Simcha was a wise and educated scholar and one of the wealthy men of the nearby city of Uman, the metropolis of the region, invited Simcha Koifman to educate and tutor his children. Simcha lived in the home of this wealthy man for twenty years and from time to time would visit his home in Ternivka (about 20 miles to the South–West).

[Page 15]

This wealthy person (in Uman) had dealings with many Polish landowners who would visit his home. In that way the educated and intelligent Simcha learned the Polish language and the manners and etiquette of landowners. After twenty years of teaching, Simcha “divorced himself” from tutoring and went into business. He established contacts with the landowners of the region and as an intelligent, honest and trustworthy man he found favor in their eyes and they relied on him for everything.

When Simcha died, his son Avraham Koifman continued to do business with the landowners until he himself became ill and was bedridden for many years until he died. His wife Tzurtel, a valiant and energetic woman, with the help of her sons (she had six sons and one daughter) and especially with the help of her two eldest sons Ya'akov and Chaim who were the pillars of the many branched Koifman family, continued on with these different businesses both when her husband was ill and after he died.

One of the six brothers, Aharon, immigrated in his youth to the United States where he became a streetcar driver and…a socialist. The Koifman brothers asked their brother Aharon to leave the “Golden Land” and the streetcar and return to the shtetl where they promised him an abundant living. But he refused to return. It would seem that as a socialist he didn't want to return to reactionary Russia and he also did not want to be a beneficiary of the charity of his capitalistic brothers…Only when the Bolshevik Revolution broke out did he return to Russia.

As a speaker of English, he got himself a good Soviet position and as a socialist he was pleased with the Revolution. As for his brothers, the “capitalists,” they became impoverished and were left with nothing. All of their property, the mill, the beer factory, etc. was expropriated. The brothers who were left without a living, left the shtetl and were scattered among the different cities of Russia and suffered like most of the Jews and the inhabitants of Russia during the Revolution.

And so one of the most glorious families, one that was always generous to anyone in trouble and suffering, left the shtetl and was scattered by the storm like chaff before the wind…

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ternivka, Ukraine

Ternivka, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Jul 2015 by LA