|

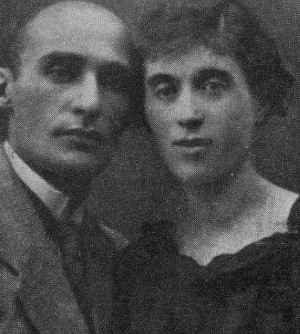

Szmuel Hersh and Sheindel Mirmelsztejn

|

|

[Pages 291-293]

by Rachel Feldger

Translated by Gal Amir

Edited by Lynne Tolman

| Project coordinator's note: The author of this article, Rachel (Feldger) Onie, immigrated to Palestine in 1937. Her mother, sister, two brothers and their families were murdered by the Nazis in Shumsk in 1942. Rachel died in Afula, Israel, in 1984. This article was translated into English from the original Hebrew by her grandson, Gal Amir. |

The towns in Volhynia were renowned for their vibrant Jewish social life, but our town Shumsk, so it seems to me, was outstanding in this respect. Its public life was Jewish-Zionist, since most of the population was Jewish. No other national group held any public activity.

Jewish social activities in the town were varied. There was a large “Hechalutz” branch, which prepared pioneers for their aliyah; there were the national funds for rebuilding a Jewish homeland -- the Keren Kayemet and Keren Hayesod -- contributions to which increased annually; there was a large Tarbut school, a Hebrew library which numbered most of the young people of the town among its readers, etc.

Much could be written about each of these, and this would be of major interest for research into the early stages of nation-building, but I will only write about the activities of our dramatic group. This group, of which I was a longtime member, was very dear to me, and its memory still reverberates within me.

I do not know exactly when the company was founded. I was among the youngest of its participants.

Its most prominent figure, one who will be forever remembered by anyone who participated in the group, was our director, Mirmelsztejn, and his wife, Sheindel, of blessed memory. He and his wife volunteered to set up the group in their home and the meetings and rehearsals were held there.

|

|

Szmuel Hersh and Sheindel Mirmelsztejn |

The dramatic society had two objectives. The first was to develop the artistic and cultural interests of its participants and its audience. The second was to engage in activities which would strengthen our identification with Zionism. Artistically, we made efforts to present plays by well- known Yiddish playwrights, above all Sholom Aleichem, Goldfaden and [Jacob Michailovitch] Gordin. Zionist activity centered on donating the proceeds of the shows to the national funds and the “Hechalutz,” and to helping those of our friends who were making aliyah. The dramatic society had a third objective, incidental but of educational significance. It was to make us aware of our responsibility to our community. Part of our income went to charity for the needy -- matzot for Passover, firewood in the winter, etc.

It goes without saying that the activities of the drama group were based completely on voluntary collective efforts, with no personal financial rewards for anyone. And yet, some of the audience viewed us as mere “comedians.” Fortunately, most of the audience appreciated our work and were sympathetic to our cause.

We spared no time or effort. None of us ever missed a single rehearsal, in rain or snow, and we even contributed our own money for costumes, scenery, or musical scores in the cases where a show did not cover its expenses.

I remember Mirmelsztejn, standing among us during the rehearsal, guiding, encouraging, influencing, giving strength, like the great teacher he was. He wanted his pupils to succeed, and he was concerned with the nature of the group we were building, so he did not spare his anger when he felt that we had deviated from the spirit of the play or the goals of the dramatic society.

In the home of Sheindel and Mirmelsztejn we experienced a taste of freedom and deep friendship, and we loved meeting there.

Sometimes in my mind's eye, I see myself in their home, engulfed by its warmth, belonging to a large, ever growing group. To this day, I feel that I am connected to those who with me participated in those cultural evenings, and who are no longer with us now. Sometimes their images appear to me, and I remember them as they were. Here are Fania and Grisha Akerman, of blessed memory, Fania, our “prima donna,” and Grisha, the director who succeeded Mirmelsztejn. The beautiful Fania played every part like a professional actress, with talent, taste and charm. Grisha was the cheerful joker who made us laugh and be happy. My sister Batiah, of blessed memory, played the part of the Jewish “Yachne”[1] in many plays.

Chaim Klejnsztejn was the comedian, the company jester, who played Hotzmach in “The Witch” (“Caledonia”),[2] and Ting Tang in “Salome.” Alongside them were the many less talented actors who were always prepared to allow the stars to “shine” and so ensure the success of the show.

Alongside the dramatic group there was a small string orchestra which accompanied the performances. Here too were beloved friends who gave of their musical talents for the success of the plays, and I recall those who were most prominent: my brothers, Moshe and Yaakov Feldger, of blessed memory; Meir Akerman, may he rest in peace, and Tartekovsky, of blessed memory. This modest orchestra was so devoted to its calling that it developed into the best of such musical ensembles. Even members of the arrogant Polish ruling class who held anything not Polish in contempt had no choice but to recognize their talent and invited them to play at their shows. This, of course, enhanced our pride in being Jews.

The repertoire of the dramatic society included outstanding plays by Jewish playwrights, such as Gordin's “Mirele Efros,” “The Great Win” by Sholom Aleichem, and others, and Goldfaden's operettas “Bar Kochba,” “Salome,” and “The Witch,” which were the audience's favorites.

In preparing material for the shows we were always concerned with presenting problems and the search for their solution, but in order to remain acceptable to a wide audience we were compelled to acquiesce to common taste. If we didn't present plays which were attractive, the audience would leave us. We, in the dramatic group, had developed a group spirit of our own, had many shared experiences, and were a unique force in our town, Shumsk. We had many shared experiences behind the scene, with all that these entail.

There was no dearth of humorous incidents and “curiosities.” We presented the last plays in the auditorium of the public school Shkola Pobshechna, but before that we performed in the Wilskier Braver, a wine hall that did not have enough light, but had enough space … and also had birds which would defecate on the audience during the shows...

I remember during one show in the Shkola Pobshechna we all went on stage, in costume and makeup. The curtain went up, and the actors waited for the cue from the prompter -- but the prompter was not in his place! The audience sat quietly, waiting expectantly, but the fellow had disappeared ... Of course we had to lower the curtain. We stood there, not knowing what to do, when suddenly we saw the prompter, Zecharia Sztejnberg, may he rest in peace, standing in one of the corners of the stage, behind the scenes, praying “Shemone Esre”[3] with devotion. This made us laugh -- not according to the program, of course, and the audience stirred in surprise. But we forgave Zecharia, and the play was a success in spite of the late start. It was only then that we learned of the identity of our prompter. There was something in him that symbolized our activities: boundless dedication to the Jewish nation, employing all means possible -- both the ancient one of prayer and the so-called modern one of artistic expression -- each one loyally whispered, with equal fervor.

Footnotes:

[Pages 294-296]

by Akiva Shprecher

Translated by Rachel Bar Yosef

Edited by Lynne Tolman

| Project coordinator's note:The translation of this article is in memory of Akiva Shprecher, who immigrated to Palestine from Shumsk in the late 1930s, lived in Haifa, and passed away in 1993. The translation was donated by his children Haim Shprecher and Miriam Adir. |

I write these words, which spring from my great love for my town, especially for the Shumsk Yizkor Book. My fondest wish is that this book will serve as a historic document, to which future generations will turn to read about the conditions in which we grew up, studied, developed. Our reality here in Israel today is nothing whatsoever like the conditions of that time and place. Herein lies the greatness — as well as the weaknesses — of our forebears.

Our town of Shumsk was surrounded by 24 villages, most of whose inhabitants were Pravoslavic Ukrainians, who made their living either farming or working in the nearby forests. A few thousand Jews lived in the center of the town; most of them were engaged in trade, with the exception of a few dozen heads of families who were laborers (tailors, cobblers, carpenters, glaziers, etc.).

Part of the town was hilly. At its southern edge ran the Vilya stream, which drove two large mills. Avraham Rajch's mill supplied Shumsk with electricity, lighting streets and houses. In this our town was different from the other towns in the area, which remained in darkness for many subsequent years .

Every week there was a traditional market, to which the farmers would bring grains, fruits, and vegetables. With their profits they would buy groceries, clothing, and shoes, and they would end up getting drunk … and being arrested by the police.

The youth of Shumsk — their education and future prospects

For many years, the people of Shumsk were content to study Jewish religious subjects in the Talmud Torah school in the synagogue study hall. As time passed, they started to teach their sons secular subjects and de-emphasized Torah and Gemarrah. There were two schools in the town, a state elementary school and the private “Tarbut” school, whose high tuition cost made it inaccessible for many children. This was a great pity.

The children at the Tarbut school were taught Hebrew and general subjects, as well as receiving a Zionist education that involved preparation for physical labor and “Hachsharot.”[1] Once a boy finished his elementary schooling, in most cases he would work to help support his parents and family. But since there were an average of four or five children in each family and there was not enough work to go around, thoughts of emigrating to America would enter people's heads (already in those days tens of thousands of Jews were bewitched by the thought of America). Later, beginning in the 1920s, some pioneering spirits started thinking in terms of settling in the Land of Israel. This was when our local branch of “Hechalutz”[2] got organized, encouraging the young people to adopt real physical labor. The boys, including Lokaczer, Seforim, Shalom Rojchman, and others, worked in the timber warehouse, and all the Efros sons started learning carpentry. The parents were amazed by the phenomenon that our boys, with their own hands, were turning out work on a higher level of craftsmanship than the gentiles. The girls started to learn to weave reed baskets, under the guidance of a gentile master basketweaver, right in our own home. My sister Devora, Malka Klejnsztein, and Gittel Seforim later went to “Hachsharot” in Klosova[3] and other places in Poland. To the best of my recollection, the first pioneers made aliyah[4] during the riots of 1929, after taking their leave of the townspeople with a mixture of joy and sadness.

This was the generation of revolution and revolt, a generation that took a dim view of our town life, so deficient in terms of economic stability. They aspired to put the situation to rights by making a radical change and embracing a productive life of manual labor and the realization of the dream of establishing a Jewish state in the Land of Israel. Later, the town's branch of Betar and the “Hachsharah Kibbutz” were organized, based mostly on work in the sawmill in Malanyov (about 7 kilometers from Shumsk). This was backbreaking work, which involved, among other things, lifting and positioning the logs for sawing, and all manner of associated tasks. This work supported these boys, at the same time that it provided training in an occupation for those who were not thinking of leaving Poland. There were other boys who went to the ORT school in Kremenets to study. (ORT was a Bund-influenced school system that sought to train Jewish youth for productive employment.) Jewish boys began unashamedly to turn their energies to physical labor, even if they were planning to spend the rest of their lives in Jewish Shumsk.

Social life and leisure

The young people would meet at their branch clubhouses, whether that be Hechalutz or Betar, and every Shabbat there would be a general meeting ending with a hike to Gorka, where there was a lovely pine forest. Some went farther afield, to the Malanyov forest, to gather berries. In the rainy season the young people would have to be content to entertain themselves in the clubhouse. The river would freeze over in winter, stretching as far as the village of Olyvus, which added an enormous amount of glassy-smooth territory to the town.[5] Not only did this make it easier for the farmers to get to the town; the frozen river also enabled the more athletic young people to ice-skate, some with wooden blades and some with steel. In the evenings, they would gather with their sleds on the top of a hill and slide down, over and over.

Enlistment in the army

When a boy reached the age of 18, he reported to the municipal office for a routine examination of his papers, and at 21 he had to report to the recruitment office in the district city of Kremenets for a medical examination and assignment of his health status. A boy who was underweight would receive a deferment for one year, but if after three examinations he was still underweight and his health did not improve, he would receive a release from the army. To obtain this magical release, our boys would gather for months before they were due to report, spending hours upon hours eating seeds, in their desperate effort to lose weight and get out of serving in the alien army. There were extreme cases in which parents collaborated with their sons and baked them cakes made with castor oil for this purpose. Those who had already resigned themselves to serving in the Polish army used to run riot on the last evenings before their mobilization. A typical prank might be changing signs from “cobbler” to “doctor” or from “doctor” to “carpenter,” or using boards and snow sleds to erect tall barricades, and so on. I should point out that the gentiles considered it a source of great shame to evade army service, but Jewish youths would resist being called up for two reasons: fear of anti-Semitic abuse at the hands of their comrades in arms, or fear of eating meat that was not kosher or not ritually slaughtered, or a combination of the two.

There were the youth of Shumsk, and these were their concerns and activities.

Footnotes:

Penina (Dorfman) Sharon of Kibbutz Afek in Israel, originally from Shumsk, explained in oral communication with the Shumsk Yizkor book translation project coordinator that the Shumsk branch of Hechalutz Hatzair (the Young Pioneers) -- which was a youth movement for children and teenagers -- had a special hachshara project for its young members. It involved working on tobacco plantations that were owned by two Polish Army officers who had been granted land in the area by the Polish government for their exemplary service in World War I.

Return

[Pages 297-299]

by Mordechai Gilon

Translated by Shulamit Berman z”l

| Project coordinator's note: Mordechai Gilon, born Mordechai Freider, immigrated to Palestine in 1934 and Hebraicized his surname to Gilon. Mordechai was one of many children born in Shumsk to Etya and Yisrael Leib Freider. Shalom Freider, who wrote “Our Rabbi, Reb Yossele – and Sports” on page 221 of this book, was a brother of Mordechai. Other members of the family chose different surnames in Israel. Mordechai was named for his grandfather, Rabbi Mordechai Freider of Kosogorka. Mordechai Gilon died in 1987. Another article about the drama group in Shumsk, written by Rachel Feldger, begins on page 291 of this book. |

The first association of theater lovers in our town convened with neither stage nor professional direction. It consisted of a few “theater freaks” led by Herzog Milman and Mirmelstein the photographer, who, together with his wife,[1] organized the first amateur troupe.

I remember our early misgivings when we rehearsed the first play with the aid of our first prompter, the late Zecharia David Ziskind,[2] who hid under the table in order to fit into a “bunker” in the middle of the stage, because he had to sit there whispering during the play.

Our first material was taken from the library. We dramatized it ourselves, and thus the first version of “Caledonia” was performed. A great deal of its success was due to the late [Avraham] Kunyanski, who was already the father of several children. One of his daughters, who now happens to be my sister-in-law,[3] played a leading role, as did her father.

I'm not going to enumerate the other difficulties that beset the amateur troupe at the outset – obtaining a permit from the authorities for each play by bribing the commandant, the journeys to Kremenets, the regional center, and to the starosta (community elder). This duty was undertaken by Elyakim Katz,[4] the troupe's “public relations officer.”

After the coveted permit finally arrived, feverish preparations were underway to erect a stage in Shimon Sivker's inn. First we had to clear out the waste from the horses that were usually harnessed there, eating their fill from the trough. It wasn't easy to build the stage. Everything was done by volunteers, from dragging boards from Yudel Kolsnik's yard to getting nails from Leib Berels'[5] shop. It should be noted that without the participation of Yudel Kolsnik's sons, Shmuel and David, and Leib Berels' daughter Ettil, we would never have managed to build the stage.

|

The set was designed by Sheindel Teicha's,[6] who was also our leading lady. The director was her husband, Mirmelstein. And so we completed our preparations for the play.

On the evening of the performance, after the kerosene lamps were lit on stage and Zecharia had inserted himself into the “bunker” to prompt us, we had our first mishap. A calf had been forgotten behind the scenes, and now it began to make itself heard. The play had to be delayed while it was reunited with its mother. So the play did not begin on time. The audience, seated on bare planks with no backrests, indicated their displeasure, which increased as the play progressed. Luckily for us they didn't notice that some sections of the play were missing. Our prompter Zecharia became confused and jumped two pages ahead when the light went out, and by the time a match was found the actors, too, were confused.

It all ended well, however. The orchestra of David with the Lips, [7] under the direction of Yankele Poyker and Minkofsky, played a pleasant accompaniment totally unconnected to the subject of the play – marches, gypsy airs, a hodgepodge.

It turned out that had we opted to forgo the orchestra and not invited them, we would have performed before an empty hall. The audience loved the orchestra. We once attempted to stage “Dorfus Young” without the orchestra which ate up most of our profits. It was in Chaim Wilskier's stables and brewery that we learned our bitter lesson. The musicians settled down in the yard in front of Holy Cross [the church on which there was a large cross] on the way to the theater, and began playing dance tunes. Gentile boys and girls filled the yard and started dancing, and the curious onlookers forgot the theater, or, more to the point, they forgot about the play. They stayed with the dancers and abandoned us. We had no choice. We had to come to an agreement with Dudi with the Lips and his friends. Spurred by the marching band, the audience moved in the direction of the theater and tickets sold out in the blink of an eye.

Nevertheless, despite all the glitches, we still recall the special experience of preparing for a play, the collective effort, and the unforgettable cultural evenings.

In the course of time the troupe improved and began staging plays in Kostyuk's school hall. We were on our way! But that's precisely when the painful separation occurred. The troupe split into two: one led by Mirmelstein the director, and the other headed by Herzog Milman, the producer, manager of the Tarbut library.

The split was ideological. As pioneers of the revolution in Shumsk, we did not agree with the material being staged. We also demanded that all proceeds be channeled toward helping needy immigrants to Eretz Israel. But the outcome was not good. There was competition between the plays; venues were snatched up. The whole town was stirred up. The commandant was unexpectedly pleased; the printers were happy. The main problem was with the orchestra. It was made up of four musicians and since there was no possibility of their splitting up, they remained neutral. They performed for the highest bidder, sometimes in two places on the same night, playing the same repertoire of marches, polkas, and wedding tangos.

This was the early beginnings of Shumsk theater. In the course of time it grew into something we could be proud of. When we hosted troupes from far-off places with playwrights and directors like Yitzhak Nuschik, Yaacov Adir, A. Wolfstadt and others, they often expressed their admiration and amazement at our theatrical achievements, despite all the difficulties we had faced.

The plays contributed a great deal to the education movements, the fund drives, and the Zionist organizations.

|

|

The Dramatic Society |

Footnotes:

[Pages 300-304]

by Chaim Livne (Yukelson)

Translated by Shulamit Berman z”l

| Project coordinator's note: Chaim Avraham (Yukelson) Livne was born in 1913 to Rivka (Berezin) and Alter David Yukelson. Chaim graduated from the Tarbut School in Shumsk, studied at a vocational school in Kremenets, and became active in the Zionist youth movement. In 1933 he moved to Palestine. He was a member of Kibbutz Messilot in the Bet Shaan Valley, where he lived until his death in 1991. Further details of his life and family are in the introductory notes to “Schools in Shumsk” on page 267 of this yizkor book. |

Population: numbers and composition

At the entrance to the town hung a banner giving details of the population. If my memory is correct, the numbers were as follows: over 1,000 men and slightly more women. In other words, close to 3,000 residents. These figures apply to the year 1928. Just prior to the Holocaust the population had almost doubled.

Most of the townsfolk were Jews. The population in the suburbs was mixed. There were also some gentiles who made their living as the proprietors of eating-houses or kiosks in the market. Gentile urbanization was on the upswing, and further economic anti-Semitism was fomented under the Polish regime, in addition to passionate religious anti-Semitism.

The large cooperative movement in Ukrainian villages and the growth of consumerism, which began with the slogan “What is ours goes to us,” helped fuel anti-Semitic polemics. Gentiles settled among Jews, but the Jews always constituted the large majority in Shumsk.

Shopping center

Most of the Jews made their living from small businesses. The center of town was shaped like a large square, surrounding four rows of wooden shops. The struggle of the authorities to convert them to brick structures continued until the Holocaust. This ongoing battle ended, of course, with the victory of the authorities. The many delays in carrying out the decision cost the Jews a great deal in bribes.

|

The wooden shops were not particularly large and there was an ever-present threat of fire. Peasants from the nearby villages arrived once a week on market day to stock up for the week. They bought items such as pickled herring, sugar, oil, spices, haberdashery, clothes, shoes, kerosene, candles and so on. Many items of food and clothing were made by the farmers themselves. With the rise in the standard of living, however, the number of items the farmers bought in town rose accordingly.

Market day

Market day was always Monday or Thursday. It was also on the eve of every Orthodox Church holiday and sometimes also on the eve of Catholic Church holidays. Wagons harnessed to horses were lined up in the center of the market square and in every street in town. One family member remained with the wagon to guard the produce to be sold, while the others went round the market and into the shops to haggle and look for goods. The extent of commerce in the shops was linked to how much farm produce was sold – grain, poultry, eggs, homespun cloth, flax, boar bristles, honey, milk and so on. The scope of the farmer's purchases depended on the demand and on how much he charged for his produce.

|

Market day was always lively and colorful, with the farmers in their dazzling scarlet and rose colored peasant garb. The sounds of the horses and the enthusiastic hubbub of the crowds added to the overall noise and excitement. Market day also provided social entertainment. It was the one day of the week when the farmer left home, met people, spent time in town, and drank a glass of brandy with friends. Sometimes the entertainment consisted of a street singer, or the two blind men who sang about heroes and events in their native Ukrainian, accompanied by a three-stringed lute. Or maybe there would be a juggling duo performing for money. The townspeople were rushed off their feet on market days, but that's when they made their greatest profit.

The region and transportation

The Shumsk region was quite large, with a “hinterland” of villages within a twenty to thirty kilometer radius. The farmland was generally good – the black Ukrainian soil near the Black Sea yielded abundant crops. The area was thickly forested with oak, birch, and pine, which provided material for the building industry. Shumsk, situated among the forests, got its name from the sound of the trees.

The larger businesses provided merchandise to the small shops – iron, building materials, fabric and so on. The wholesalers bought their wares in Kremenets and L'vov, and even as far afield as Lodz. Until recently the only way to travel in the vicinity was by horse cart, but now a bus connects the town with the outside world, but only in summer. Once the rains turn the roads to mud, followed by frost and snowstorms, the horses and winter wagons return as the only means of transportation.

Commerce and crops

An extensive branch of industry was devoted to the grain trade. Most merchants lived outside the town, competing with one another as regards the distance of their warehouses, each wanting to be the first to claim the farmers when they brought the grain to town. This resulted in fierce competition among the grain merchants. Many a time two Jews would pounce on the same sack of grain and it would develop into a brawl, with each party enlisting his family's aid. This resulted in embarrassing social situations for the Jewish merchants. Lately the grain merchants have become very prosperous. Some have installed a telephone in their homes and adopted affluent airs.

The trade in seeds for fodder has been booming. Rumor has it that the Germans use them for manufacturing dyes.

Forests and trees

Ever since Poland regained its independence, trade in timber and building materials belonged entirely in the hands of the Jews. The forests were owned by the Polish government, who either confiscated them from the landowners or inherited them when their owners remained in Russia. The government handed the forests over to the Jews for purposes of commerce.

Some were involved in leasing the forests while others worked with them as brokers. They were extremely quick-witted, smooth-tongued, and accustomed to dealing with gentiles. But there was also a drop of bitterness … The forests, the loneliness, and the distance from their families all left their mark. Nevertheless they were known as a cheerful and well-established tribe, whose unique stamp was evident among Shumsk's Jews.

In the course of time their importance diminished.

The great sawmill in the forest was transferred to the Polish government, who employed many non-Jewish Poles. Also, business was also transferred to more distant merchants.

Craftsmen

Most of the craftsmen in Shumsk were Jews: tinsmiths, tailors, carpenters, blacksmiths, watchmakers, and so on. The tailors opened factories for ready-made clothing that they sold in the market. The shoemakers were the lowest class. Many Jews also earned their livelihood sewing women's clothing. Actually, the large majority of Jews were wagon-drivers. Everyone needed them and everyone knew them. There were all kinds of stories about each one of them – their habits, how they treated their customers … They were known for being belligerent and fearless, traits they had developed driving on dangerous roads in severe winters. They could teach any thug or bully-boy a lesson. They were proud – more than once they stood up to defend the reputation of the Jews.

The town's barbers knew how to cut hair and spin yarns. They had plenty to say and they knew everything. Their profession required them to know a lot so they could entertain their customers while their scissors were at work.

The idlers of the town would crowd into the barbershops to enjoy the jokes and the banter.

Industry

Industry in Shumsk consisted of a few fairly primitive factories: oil presses powered by a blind horse or by hand, and a few crushing machines for buckwheat grits which were also powered by hand.

A modern industry, according to the standards of those days, was A. Buder's[1] fabric factory, where he made winter coats for the peasants from raw, unprocessed wool, using motor-driven machines. His employees were family members, apart from one German expert who came from outside. There were two water-powered flour mills that worked to full capacity 24 hours a day. The employees were gentiles but the owners and supervisors were Jews. Next to Rajch's flour mill was a five-story structure that had once been a windmill. Judging by its dimensions it must have been very big. Now it was useless and roofless. We were told that it burned down along with its machinery. It was the biggest building in town, clearly visible from afar.

The mills were powered by water from the Vilya River. The river was also used as a fishery. Every four years the waters were drained out by opening the dams and the fish were extracted and sold in the surrounding towns.

In conclusion it can be said that the townspeople worked very hard to eke out a living. A few did not earn their living honestly, but they were very few.

There were also some special “businessmen” in Shumsk. They were horse traders, who didn't always abide by the highest ethical standards. There were many ways to give new life to an old horse, dyeing and shining its mane and tail, making it drink alcohol … all designed to trick the buyer. There was a common saying, “to lie like a liveryman,” which meant to lie like a horse trader. Among them were those who stole horses from farmers' stables and then sold them in the market. They could be seen on market day, shod in clumsy boots, wielding a whip on the horses for sale.

They were as daring as the devil and quick with their fists. In times of trouble they used their fists to protect Jews when they were involved in a dangerous fight with their gentile neighbors, but that did not ingratiate them with the Jewish community. They were despised for their dishonest trading practices.

Many circumstances forced the Jews to pursue a despicable lifestyle. Sometimes the thirst for life led them to do all kinds of things simply to survive. Nevertheless the positive outweighed the negative in the economic life of Shumsk, and godliness was observed, albeit at a very high price.

Footnote:

[Pages 305-307]

by Pesach Lerner

Translated by Shulamit Berman z”l

| Project coordinator's note: Pesach Lerner was born in Shumsk in 1901 to Malka (Roichman) and Moshe Lerner. In pages 261-266 of this yizkor book, he describes the cheder (elementary school) he attended from 1904 to 1914. He immigrated to Eretz Yisrael in 1921. He founded the Organization of Shumskers in Israel. For more biographical information, see the translator's notes on page 199 of this yizkor book: https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/szumsk/szu185.html#Page199. |

A few years before the First World War the Czar legislated compulsory schooling and Shumsk gained a mixed school for boys and girls, Jews and gentiles.

The situation was bad for the Jews. Teachers and pupils alike conspired against them, causing a great deal of trouble, and nobody in town stood up for them. However, when it was decreed that Jewish children must attend school on the Sabbath, tempers flared. Everyone in Shumsk, young and old, focused solely on this problem. Nobody was willing to accept the situation.

After much lobbying a compromise was reached. The children would attend school on the Sabbath but would not be required to write.

Not everyone was satisfied with this compromise and parents began taking their children out of school.

Out of strength came forth sweetness:

Matisyahu Freider,[1] an excellent teacher, took it upon himself to establish the first Jewish school in town, at a time when it was not permitted. This was therefore a clandestine operation fraught with difficulties, and the teachers faced danger on a daily basis. Classes were held in a tense atmosphere. The teachers were constantly on their guard. We loved our school. Our teachers were true academics with a vast wealth of knowledge. We acquired the rudiments of language and advanced rapidly in general subjects. Every lesson was an event, and the situation of the teachers became ours too. Together with them we feared that our underground school would be discovered.

And then it happened.

It was during a lesson with our beloved and esteemed teacher Yehiel Kanfer.[2] We were all focused on a student who was demonstrating addition and subtraction on the board. Suddenly our teacher left his place and dived through the window like a gangster. We wasted no time leaping after him. Afterwards it transpired that our offense had been discovered and the regional inspector suddenly turned up at the scene of the crime.

The school was closed. We continued to study privately with our teachers. Once I conducted a survey and discovered something strange: The teachers who devoted themselves to teaching Hebrew did not go to Eretz Israel but emigrated to other countries, yet most of their students are in Eretz Israel.

Before the outbreak of World War I it was impossible to alter the situation with regard to education and there was no Jewish school.

In the first year of the war no attention was paid to education. There was general confusion among the Jews and all eyes were focused on the unrelenting war and economic concerns. But in the second year a new kind of life took hold that also allowed for education.

That was when Shlomo (Wallach) Ben-Yehuda, a seminar student from Eretz Israel, turned up in our town. He had been stuck in Russia and found himself in Shumsk. He was the first to introduce the method of teaching Hebrew in Hebrew, and he displayed exceptional teaching ability. However, he taught privately, so most of the youth were left without the learning establishment our parents had become accustomed to during the brief period of Matos Freider's school.

So they brought a qualified teacher with a state license to the general Jewish school: Mr. Meir Dikshtein.

|

Dikshtein, now deceased, was popular with everyone in Shumsk. His focus on teaching Talmud in school inspired trust and within a short time all the Jewish youngsters in Shumsk who were seeking an education began to visit him. His family adapted to the town as if they had been born there. Shumsk had acquired a new and respected family, whose many children were educated and talented.

Since he was a semi-official functionary, we were not aware of Dikshtein's public persona, but from the behavior of the kids who attended every Zionist activity including the drama group, it could be assumed that he had a Zionist background. When I was preparing to make aliyah to Eretz Israel his family asked me to convey their good wishes to Meir's father. It then became clear that Dikshtein's formal guise concealed Zionist leanings.

Upon my arrival in Eretz Israel I visited grandfather Dikshtein. I found an elderly, serene gentleman sitting with a Gemara open before him, preparing the lesson he taught on a voluntary basis at the local synagogue.

|

|

Manus Matisyahu Freider |

Then Matisyahu Freider was also seized with literary zeal. He took advantage of the reigning confusion and the waning fear of the authorities to reopen his Jewish school, where general subjects were also taught. All his teachers were from Shumsk and they were all excellent. They included Sonya Ackerman, who taught Russian, geography and math; Hirsch Mendel Geldi,[3] who taught grammar and Tanach (Bible) -- and best of all, Yaakov Zilber,[4] who was loved by all the students and whose lessons in grammar, Tanach and language were unforgettable.

We were able to gauge the quality of advanced Hebrew education in Shumsk when we emigrated to Eretz Israel and discovered our spoken Hebrew was rich and our cargo of knowledge was considerable. You couldn't tell that we had learned with misgivings, at intervals, with disruptions, in secret. Many of us felt our early education was the foundation and chief factor in the fulfillment of our aliyah.[5]

|

|

| This image has no caption in the original Shumsk Yizkor Book. It is a receipt from the Keren Kayemet (Jewish National Fund) for a contribution made in Shumsk on the 30th of the month of Heshvan. The year is not stated. The amount is 32 guilders and 20. The receipt contains the name Sudman and possibly the words “Hoshana Rabbah,” which is the next-to-last day of Sukkot, when people give charity. Yisroel Sudman built a shul, so perhaps this receipt is for money contributed by the people who prayed there on Hoshana Rabbah. |

Footnotes:

[Pages 308-309]

By Mordechai Gilon

Translated by Shulamit Berman z”l

| Project coordinator's note: Mordechai Gilon, born Mordechai Freider, immigrated to Palestine in 1934 and Hebraicized his surname to Gilon. Mordechai was one of many children born in Shumsk to Etya and Yisrael Leib Freider. Shalom Freider, who wrote “Our Rabbi, Reb Yossele – and Sports” on page 221 of this book, was a brother of Mordechai. Other members of the family chose different surnames in Israel. Mordechai was named for his grandfather, Rabbi Mordechai Freider of Kosogorka. Mordechai Gilon died in 1987. |

The idea of establishing a kindergarten at a time when people were unwilling to entertain any thought of secular progress, and to teach small children, was daring, and it involved personal risk.

I don't know how I, the writer of these lines, dared to do so without public support and without even a helpful atmosphere.

The year was 1924. I had returned from my studies in Rovno and Sarna and submitted my idea to the Zionist bodies in town but I was turned down. They raised many doubts about the feasibility of such a venture.

The truth is that the Shumsk financiers were right. The difficulties of aliyah[1] and their efforts to support it used up all their resources. They were also concerned with the reaction of the ruling religious sector, who would view it as heresy, and in order to save the little ones they would intensify the town's opposition to all Zionist activities. It could also be assumed that the teachers, their cronies, and their cronies' cronies would regard it as robbing them of their livelihood.

Nobody would dare “deprive” Jews of their income.

I set out on an unpaved path. Alone, solitary, in a hostile environment and with no real hope of bringing my project to fruition or even a suitable place to function. A kindergarten without children.

|

|

Mordechai Freider with the kindergarten in Shumsk in the month of Av (July/August) 1927 |

I launched a private effort and managed to persuade several mothers, but many had strange questions for me: Will this ensure a paying profession? Will there be a belfer[2] to carry the children on his shoulders? And many more such klotzkashes (foolish questions) for which I had no satisfactory answers.

Armed with the promise of this small number of children I began seeking a place for my poor establishment.

Such a place could not be found in our town. And if such a place could be found, it was not available to me, for fear of excommunication and penalties and the like.

The only one who shared in my efforts was Yossil Basils. He had just added a salon and he gave me the use of the new spacious room in his house.

The room had no floor; the ground was plastered with clay. It was dusty. The walls were pitted with holes. Until now it had been a roosting place for ducks, who were still around, even during classes. I was given to understand that my landlords had the right to go through my classroom whenever they pleased.

When I agreed to this condition I was not aware that the landlord was usually accompanied by curious neighbors with plenty of free time, as well as traders who came from the fair on market days.

I accepted all these initial torments and continued with my project for a while.

The parents of my “students” were extremely satisfied and showered me with blessings. The little ones found themselves in a shining garden of childhood, free of the burden of early Judaism and the yoke of mitzvot here, in their age of freedom. They learned to write and draw. They expressed their feelings in many ways, and it seemed to me that I would continue. The parents would change their concepts of education and I would be able to attain my goals.

Regrettably, “my parents” were the first who were put off. They caused my efforts to fail when they saw that their children were not studying Torah and there was no chance of them boasting of how they could quote Rashi's commentary. They were alarmed by such nonconformity and at the first opportunity they pulled their children out.

The kindergarten in Shumsk did not last. I was tired and disappointed. When I think back, I only do so in order to remind myself and others of our daring, when we tried to achieve what we did, to some extent, in order to promote Zionism among the people of our town.

It's a shame they didn't let us.

Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Szumsk, Ukraine

Szumsk, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Mar 2025 by LA