|

|

|

[Page 196]

by Tzvi Hirsh Neufeld, Johannesburg

(memories of a home that is in ashes)

Translated by Esther Libby Raichman

Hirshl, Write!

(a sort of introduction)

For over 20 years I have constantly heard a voice which keeps calling out: Hirshl, write! During all these years I stood helplessly listening to this special voice and asked myself, trembling: What should I write, how can I write and am I worthy of writing about the Jewish Stoibtz which is no more? Stoibtz is ruined and razed to the ground. Among the 3000 Jewish men, women and children who were slaughtered there by the savage killers, may their names and memories be erased, I have a great personal stake: the loss of my youngest brother, four sisters, their children and grandchildren. So where then are the words that could truly express my pain and sorrow when they all stand before my eyes - all the 44 innocent souls of my family! - Most of them still quite young - all murdered together without mercy.

And suddenly after so many years, I hear a voice, an urgent call that I can no longer resist - the call is from my dear friend, my warm old friend Zalman, whom I last saw 42 years ago - the same Zalman who was worthy of being elected to the highest position in the Jewish land of Israel. And when the President calls then the old disciplined soldier that I am, must be at his service.

As I take pen in hand, I will try to search my memory, rummage through my mind for everything that I remember and am able to recall about our ruined shtetl. And I pray that as a poor bystander, my words should be worthy of this eternal monument - the Sefer Hazikaron of the town of Stoibtz (Memorial Book) - and do it justice.

Stoibtz of Yesteryear (background)

The holy community of Stoibtz was established between the 12th and 13th century when the persecution of the Jews in the more developed countries of Europe forced them to flee to the more primitive Russia. Every family then chose a village or a town where it was convenient for them to settle. Our ancestors chose to settle in and around Stoibtz mainly for two reasons - firstly because the town was surrounded by very old forests (which is also the source of the Russian name of the town: Stolbtzi) and secondly - because of the great Niemen river that flowed past the shtetl.

|

|

Their Jewish instinct that made them feel that this was the right place for trade and work did not disappoint the incoming Jews.

|

|

Hundreds of acres of forest were bought by Jewish forest merchants. They employed hundreds of overseers

[Page 197]

who worked with measuring tapes. Thousands of peasants cut the more than 100 year old trees. In the winter months hundreds and thousands of sleighs followed one another with long thick logs stacked on top of them. From early morning until late at night, the sleighs used to glide along quietly and smoothly through the market to the river's edge. Here the managers stood and paid the peasants with coupons; later the peasants would come to the shops in town and purchase their provisions with the coupons. On Sundays the merchants exchanged the coupons in the offices of the forest merchants. In the spring the Niemen used to overflow its banks and flood an area of more than 3 *viorst[1] reaching as far as Drazdi and sometimes even further. When the “river returned to its shores”, only then did the feverish work begin: The release of the logs into the river, tying them together in a “bench”(a bundle) ; 15 - 20 in a bundle; 10 - 15 0f these bundles were tied together on a raft on which they used to erect a straw booth to be ready for the journey.

Every day one could see hundreds of raftsmen walking through the market place with pants rolled up and long hairdos. Their wagons were packed with bread, groats, salt, pork meat and other kinds of provisions; they also had with them, spoons, bowls and other eating and cooking utensils for a journey of 3-4 weeks until they reached Kovno. In Kovno they transferred their entire shipment of logs to Lithuanian raftsmen who had to continue the journey to Memel. They returned home by train. On their return to Stoibtz, they used to leave their bundles with the Jewish merchants and innkeepers and go to the offices to get their salaries. After purchasing the necessary supplies for their families, they used to sneak into the saloon and get drunk and with the dawning of the day, each one would walk to his village. They remained there for a couple of days, rested a little and once again returned to the rafts.

There was another source of income for the Jews in the 60's (19th century). Russian merchants from Smolensk, Riazan and even from Moscow used to arrive with 3 horses in tandem, hitched to large sleighs packed with grains - barley and oats, wheat, corn and buckwheat - which they sold to Jewish merchants. They used to unload into the big granaries at the port on the river. The granaries stretched from Mordechai Yerucham Charchurim's house to Chadzinski's 3- storied stone granary. In the spring the grains were packed onto barges and exported.

Jews earned a living from exporting grain at the beginning of the 60's but when the government built the railroad from Moscow to Brisk, the port became obsolete. More than 100 granaries stood empty and that - as I understand - was the reason for the fire that the older Jews talked about constantly - about how and what, happened. In that fire the port burnt down and ¾ of the town went up in smoke - from Mordechai Yerucham's house - to the new Jewish cemetery and up to the Christian cemetery. Only one structure survived the destruction - the stone walls of Chadzinski's granary which, with the burnt out holes of the windows and doors, looked like a scary image to those walking past or driving through. Years later the great and prominent merchant Benye Yanik sold his largest brick building in the market place to my brother-in-law Azriel Ruditzky and - probably - bought the ruined stone walls and in one corner, built an apartment and a store for himself. After his death his “efforts” came to nothing and I believe that the scarecrow walls still stand there to this very day.

Three large stone buildings stood in the market place at that time - their owners were: Hershke Gershenowicz, his son Molye and Benye Yanik. Three smaller houses belonged to Nissan Harkavi, Velvel Shaynes and Meir Mirski; in addition there were small brick houses belonging to Chantze and Yisroel Isser Isenberg who also had a beer cellar. All the other buildings were wooden.

Sources of Income in the Shtetl

Of the wooden homes in the shtetl some were beautifully built - such as those of Maishl Ivianski, Hirshl, Molle, Payye Malbin and Yankel Arinkes(Tsirulnik). Most of the remaining houses were shops and saloons. In the middle of the market place stood 16 wooden shops of which most were tailor shops which were colloquially called manufacturers. The others were grocery and fancy- goods shops. In the market place there also stood baker's booths where the bakers brought in their freshly baked goods in baskets on carts: corn and rye bread, bagels, cakes, perogen, butter/cinnamon cakes etc. There were also a few booths selling soda water

Aside from the normal market days, on Sundays the market place came to life with much greater intensity than on the regular days, especially on the days of the fairs such as: Ulas, which fell before Purim, Usheste and Dzeviatnik - between Pesach and Shavuot.

Already a few weeks before the special market day, the small Yachim Fillipovicz would walk around with the big drum and in a loud voice announce, that on such and such a day, a fair would take place. On the days of the fairs, more so than on week days,

[Page 198]

many merchants and tradesmen came from all the surrounding villages: there were shoemakers, tailors, trunk makers from Mir, saddle makers from Kletzk and Kafuly, pot makers from Ivenicz and Rakov, cap makers from Rubzevicz - and they would all set up their booths in a straight row in the middle of the market place and display their various wares. Then the merchants began calling out constantly to entice the customers.

In thousands of wagons in the summer and sleighs in the winter, peasants came from the surrounding villages with their agricultural produce: a wide variety of grains, potatoes, wood, seeds etc. In the summer orchard owners also came in wagons packed with all kinds of fruit. In the middle of all this noise and tumult stood a slightly built widow, Faige Kalman, the money exchanger at a small table on which there were displayed little piles of silver coins - or roubles - of 50, 20, 15, 10, Kopeks(a small Russian coin). On her apron she hung a large bag of coins and the table draw was filled with heaps of paper bank notes. She herself was as big as a groshn (half a Russian Kopek) and on winter days she stood covered in furs over a fire tub, looking like a round pumpkin. Her business of helping the merchants to exchange money ran into thousands but it never happened that anyone tried to rob her. Coming home frozen to her small room in the home of Riva Messel (Kastrelevicz) and calculating the day's proceeds, she always remained with a balance of 10 roubles and many times even more.

Stoibtz was considered a centre, a sort of capital of all the surrounding little towns: Shverzne, Mir, Yeremicz, Turetz, Lyubtsh, Nalibok, Derevne, Kafulye, Nesviz, Kletzk, Mohilne, Pestatshne, Rubzevicz, Ivenicz, Rakov etc. and also a few of the more developed small towns like Mir, Nesvicz etc. that were much bigger and more populated. Yet Stoibtz was the leading town and had the upper hand.

The Jewish Stoibtz and its Families

The Jewish population of Stoibtz consisted of a few quite large families, a few middle-size and mostly small families. The largest were: Tunik, Neufeld, Razovski, Malbin; the middle and smaller ones were: Charchurim, Mirski, Barsuk, Bruchanski, Aginsky, Gershenovicz, Inzelbuch, Russak, Machtay, Liberman, Zaretski, Dvoretski, Kushner, Ginsburg, Rubashov, Garmizze, Kantarovicz, Epshtein, Bernshtein, Pozniak, Tsharnagubov, Lyusterman, Bruk, Segalovicz, Milcenzon, Rabinovicz, Yosselevicz, Maharshak, Radunski, Akun, Ruditski, Kagan, Izgur, Renzon, Baskin, Aronchik, Levin, Riser, Lis, Shapiro, Lyublinski, Sirkin, Rubin, Munvez, Bogin, Gurvicz, Stalovitzki, Dagilevicz, Zlatter, Yanik, Manker, Berger, Berkivicz, Tzechanovicz, Chait, Manashevicz, Spektor, Lungin, Kroyshik, Viner, Kivovicz, Evenchik, Chvedyuk, Zlotnik, Shulin, Sasland, Henkin, Kumak, Altman, Krupitzki, Ratner, Yitzchak Margolin, Kitayevicz.

The Nyfelds (Novopol'ye) were, as already mentioned above, one of the largest if not the biggest and as my minority status is also of this original

|

|

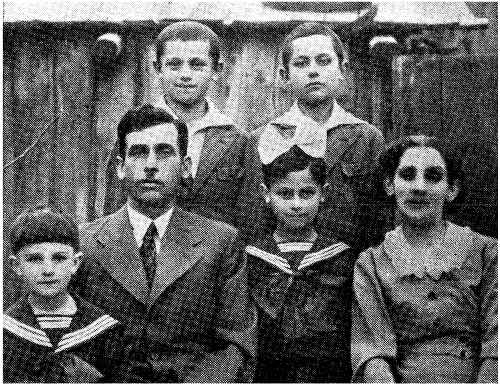

| Sitting from Right: Moishe and Feike Epshtein, Mordechai and Zlatte Pozniak, Freidl Neufeld Standing from right: Nachum and Liebe Kantorovicz, Shimshon and Hinde Weinshtein, Fyve Neufeld |

[Page 199]

family with the same name, I want to make the effort to search my brain and to dig out from it everything that I ever heard from my grandmother and my father, of blessed memory, about the prestige of our ancestors.

|

|

My Bobba Minke from Afyetzok was the only daughter of Ya'akov and Reizl of Novopol'ye which apparently translates into Yiddish as Neufeld. My Bobba had 3 brothers: Dodde, Yashe and Moshe-Tsalle. Of all the beautiful stories that our Bobba told us when we sat on the big oven and plucked feathers - wonder stories of Elijah the prophet, Rabbi Meir the master of miracles, Chonni Ha'm'agel, about bears and wolves, lions and foxes, the most beautiful was, a wonderful story of the family.

“One day a covered wagon drawn by 2 horses flew into Nove-Folye. One of the travellers jumped off the wagon, grabbed my brother Dodde who was 12 years old at the time, threw him into the cabin and - “giddiyap”, and took off down the road. When my younger brother Yashe, became aware of it, he immediately, without hesitation, sneaked out of the house and - “took off” and started chasing after the wagon. He ran like a whirlwind for 10 viorsts until he reached Stoibtz. When he saw the wagon there, he went directly to the military marshal and out of breath, in a pure non-Jewish village accent, began to plead: Let my brother go because you will not have any joy from him - he is a weakling and sickly and a Mother's boy … rather take me - I am well and strong and I will be a better soldier for our father the Tsar! The Marshal listened to the boy's pleading and he liked what he heard. So he said to Dodde: run home quickly, you weakling and if you make it home, let your Mother continue to spoil you. Yashe was sent deep into Russia and for a very long time no one heard anything from him. Four years later a Russian soldier came home to the village on leave after 20 years of service. He came to us and said: I am bringing you regards from your son - he is healthy and happy. He asked only that you send him a prayer book. When I go back I can take it to him. We bought him a pair of tefillin and a small prayer book and the soldier took it with him for our Yashe. Years later we received a letter from Yasif Yakavlevicz Neufeld, where he wrote that he was released from the army before the end of his term of service and was getting married to a Jewish girl - the daughter of a soldier from Nikolayevsk; his request is - that his Mother come to the wedding - Mother went to Moscow and spent 6 months with Yashe.

Yashe showed Mother all of Moscow, including the Tsars palace where he showed her the artfully crafted furniture that he had made; he also showed her holy icons in a small shop - his handiwork. When my Mother returned home, my brother Moshe-Tsalle went to Moscow and stayed there for a few years before relocating with his family to Kazan. He had a few daughters and one son - Abraham, who married there and then, emigrated to America. Later his wife, his son and 3 daughters also emigrated to America.

Up to here is the story that my grandmother Minke told us. Her father Ya'acov - our great grandfather - leased a plant in Novopol'ye where pitch was burned. Tree stumps from the trees that were cut were brought there and pitch, tar, wheel grease and turpentine were extracted. The ovens in which the stumps were burned were built in a specific way in order to allow the various minerals to be discharged through separate pipes. The liquid minerals were poured into wooden barrels and

[Page 200]

sold in the country and also exported to other countries.

And it came to pass on a certain day - a young man came from Ivye, named Faive Kagan who was an expert in making ovens for producing tar, began to work in Novopol'ye. There he fell in love with the young, pretty and slender Minke and they got married. In order to prevent their children from being caught by the Tsars soldiers and taken to the army, he changed his surname from Kagan to Neufeld. His brother Avremel, a men's tailor, retained the family name Kagan. He lived in Mir close to the great Yeshiva. Avremel had 2 sons: Moishl a scribe and Rafael - a town's official, and a few daughters. And here truly lies the answer to the question: How did the Nyfelds come to be kohanim[2]?

After they married my grandfather and grandmother, may they rest in peace, went to live in Ofyetzok - a village 7 viorsts from Stoibtz. After living there for a few years they moved to Stoibtz and built a home on Yurezdikke Street. Her brother Dodde - a tall good looking Jew with a silver-grey imposing beard, always clean and nicely dressed, lived on Synagogue Street next to the old Bet Midrash[3]. And this uncle Dodde is the old Jew about whom a humorous story circulated in our town. Once when a couple of Yeshivah students approached him in the synagogue and asked him to explain a difficult section of the Gemorrah[4], he answered: If he was not able to explain the Gemorrah to them, they would be embarrassing him - and that would be insolent - therefore he would not answer their question.

Uncle Dodde together with the old Jew Dovid Neufeld (Yashe the commissioner's father) - a Jew of short stature, wearing white socks and slippers - used to come to my grandmother Minke every Saturday after eating tsholent, for tea and snacks. We the young people listened eagerly to the stories they told one another about the old times. When his wife Peshe Shifre, died, he sold his house to Yankl Altman and at the age of 85 “shipped himself off” to America to his only daughter Golda where he lived out his 90 years.

My Bobba Minke had 2 sons - Leizer and Berre - and 3 daughters - Feyge, Rikliye and Sorre. Leizer married Golda-Feige Garmizze and Berre married - Hirshke the shoemaker's daughter, Simke Russak.

When grandfather Fyve died, Grandmother Minke remained living with us and managed our household until she was into the nineties. She sewed and prepared her “outfits” and for a long time she used to dress up and show everyone her wardrobe that she prepared for herself with her own hands. A few days before Tisha B'Av - in the summer of 1904 she didn't feel well and she began to prepare to go on her way … She immediately prepared an old shirt and announced: “when the women come and begin to tear pieces of my shirt as a remedy and a cure for their anxious children, they may pull me off the table” … Then she asked that her daughters in Selevicz and Lechevicz be informed as well as her grandchildren and great grandchildren in Baranovicz. The next day at 7 in the morning when everyone arrived with

|

|

the train from Baranovicz and gathered in the house, she was very happy and said: “Now that the orchestra is here one must prepare for a reality”. She recognized everybody, spoke with each one, even joked and at around 10 o'clock in the morning, with a sad smile on her wrinkled face, she closed her eyes forever. The sorrowful news spread instantly amongst the shtetl Jews and at 12 o'clock she was brought to her eternal resting place.

My father Berre may he rest in peace, was a carpenter. He used to build homes in the town and also quite often in the village - for rich peasants and nobility. The carpenters were united in labour associations - 4 to 6 in one unit. There were about 4 to 5 such units in the town. Each association separately, used to accept contracts for building houses. The cost of building a house was dependent on the size of the lot, the number of rooms etc. The price ranged from 70 to 150 roubles and the construction lasted

[Page 201]

3 to 5 weeks. During the period of construction, they used to make a few box-rooms, roofs, verandas etc. - and each time the homeowner would prepare a bottle of brandy and snacks.

The work of the association partners was set up in the following way - the better workers used to stand at the front corners of the structure to be erected, the less able at the back corners, in the middle and in the construction of the inner walls. Every Sabbath evening the partners gathered in our home. My father used to calculate the weekly earnings per person and pay each one his share. The main partners were Heshl, Avreml the son of Mendel, Shmuel Boyle, Abraham Gershon, Shmuel the little one, Velvel Katayle etc.

After finishing the calculations they sat down to drink tea and told stories from King Savyeski's times. My father often told how they built the railway line alongside the shtetl. He worked together with 100 men from Moscow and Smolensk constructing the scaffolding for the iron bridge over the Niemen River. In order to implant the pylons in the river, they constructed a floating punt with a tall mast: at the top of the mast rested a wooden log tied with thick cables that was used to pull up the heavy logs and then release them immediately on to the pylons with full force. While the log was being raised the Russians would sing a special song lasting 5 minutes and it took only a blink of an eye to release it. In this way they raised the log again slowly, singing the same tune. A story was told that Lurye, the Jewish representative from Minsk, wanted to show off his status so he approached my father and said: “Hebrew, less singing and more sweat”.

At the beginning of the 80's of the last century (19th), after Alexander the 2nd came to power, Jewish life in Russia took a new turn as a result of harsh decrees and restrictions which the Minister of Interior Pobedonostsev issued as provisional decrees: expulsion of the Jews from Moscow and the proclamation of the Pale of Settlement where Jews were permitted to live, expulsion of Jews from villages and the removal of their right to the ownership of land. As a result a large number of the Jewish farmers were forced to relocate to smaller towns in the vicinity of their estates; poor merchants also arrived who could not afford to buy the first guild's patents; also tradesmen and craftsmen who did not pass the difficult guild examinations. Suddenly the populations of the small towns expanded abnormally and parallel to it, grew the need and urgency to make a living.

Stoibtz had a large number of tradesmen who worked very hard to make a living - tailors, shoemakers, carpenters, painters, harness makers, bricklayers and wagon owners etc. There were also a large number of seamstresses who sewed for women, working with 6, 8 and even 10 girls. The conditions for learning the trade were extremely difficult. In the first year the father of a 10 - 12 year old girl had to pay the tailor or seamstress - the owners - 10 rouble. The “apprenticeship” consisted of helping with housework, caring for children, running errands, removing stitches from garments, fanning the coals in the iron, and learning to sew with a thimble from which the girls used to get blisters on their fingers. At times - by the kindness of the seamstress - they were allowed to sew a seam on the machine. In the second year the apprentice received her 10 roubles back; in the third year an additional 10 roubles, meaning 20 roubles. Each year they received an additional 10 roubles until one reached 60 roubles and many times even 80 roubles a year.

Once this stage was reached the girls usually “went out on their own”, hired 4 - 5 girls and “opened” a table and managed their own workshops. The largest workshops in town were owned by the 2 tailors of women's clothing - Benjamin Reshes (left for America) and Noach the tailor. They had the best customers in town: rich ladies, the doctor's wife, the pharmacist, the Ivanskis, the Malbins etc. They also used to travel quite often to the estates of the aristocracy with all the girls, sewing machines and all the implements for an entire week. There they would sew clothes for the noblewomen and their children.

|

|

There were a large number of seamstresses who completed their apprenticeships with the leading tailors

[Page 202]

Binyamin and Noach and opened their own sewing workshops and sewed specifically for women: Chaya, Peshe, Leah-Rochl and Shaynke - the daughters of Simche Zalman the carpenter, Golda - the daughter of Yankl the carpenter, my sister Raizl and others. There were also seamstresses with smaller shops who sewed bed-linen. The work conditions were very difficult, with working hours of 14-15 hours a day. In the summertime they worked from very early in the morning until late at night - and sometimes even another hour after lamp lighting. In the winter they worked from early morning until 11-12 midnight and Thursdays they worked the whole night in order to finish the outstanding orders for the daughters of the rich who were about to get married. On Saturday night, right after Havdalah, the workers would already be running to work with needles and thimbles in their hands.

On a Friday at lunch time, a large number of the girls would sneak out for a while to Chaim Itze the teacher who was also a book seller. The girls used to borrow books from him; they were mostly by Shm'r, Elyakum Tsunzer, Meir Isaac Dick, Goldfadden and others. The books were heartbreaking, suspense romances with awe-inspiring stories, with attractive flowery titles like: The Garden of Eden Bird, The Deceived Bride, The Bewitched Princess, The Misled Girl, Richard and the 40 Thieves and other similar 32 Paged books. After eating cholent[5] on the Sabbath, the girls lay on their beds reading and crying bitter tears over the fate of the heroes and heroines, fall asleep for a while, read again and then sing a few songs about *”the daughter of Zion the widow” the poor orphan etc.[6]

In the second half of the 90's new winds began to blow and new movements took root in the larger towns. The first sprouts grew quickly: the First Zionist Congress in Basel and the first gathering of the Jewish Labour Leaders in Kovno, stirred Jewish public opinion. They began to discuss and debate, talk and whisper about all national and social problems: even economic, political and social issues were not removed from the order of the day.

At that time a new kind of preaching had arisen. Among the wandering preachers who often visited our shtetl, a new breed of agitators began to arrive promoting the new ideal of “Zionism”. I liked to listen to their speeches and on my return home, I would stand on a bench, put on my Father's yarmulke and my Mother's Turkish shawl - in place of a tallit - and repeated a large section of the speeches. One fine day we were informed that a Rabbi from Warsaw had arrived - a Rabbi who wants all Jews to go to Zion (the land of Israel) - and that he would speak between Mincha and Ma'ariv in the old synagogue.

|

|

Naturally, I was in the synagogue long before the appointed time. A large crowd of Jews gathered there, among them the important people of the town: Mr. Yoel and Mr. Hirshe Ginzburg, Maharshak, Alter Yosselevicz, Rubashov, Lusterman and others. However, right after the “Aleinu” prayer an incident occurred: the local Rabbi walked over to the guest Rabbi and informed him that he should not approach the Bima because he, the local Rabbi, forbids him to make a speech. Jews began to whisper - a whisper which, little by little turned into a commotion and turmoil broke out. In the middle of the general uproar and hu-ha, I noticed my beloved Rabbi, Mr. Yitzchak Tanchumes stepping calmly from behind the Bima, quietly singing his usual tune. He moved close to the Eastern Wall and speaking apparently to himself but loud enough so that the crowd on the side should also hear his words:

“So he is a Rabbi?” He is only a non-orthodox Rabbi so how is it that he comes here to give speeches; he even calls his children by Christian names so how can he dare to want to speak about Zion?”

And as he was speaking he came very close to the Eastern wall and remained standing there surrounded by the large audience.

“Who is speaking there?” the Rabbi asked.

“Mr.. Itshe” one of the surrounding Jews answered, “he also says Rabbi, that the strange Rabbi is not worthy of giving a speech”.

“Is that so, do you hear?” the Rabbi caught on to this idea and in his hoarse voice shouted: “Itshe - says so too? So let him go and give his speech!” And the Rabbi, with hasty steps almost ran out of the synagogue

[Page 203]

and did not return even for Ma'ariv prayers.

The guest Rabbi wrapped in his tallit, walked up to the Bima and delivered a fiery speech. As a ten year old boy at that time, I hardly understood anything of the speech. The speech was new, without a tune and without an end and later I tried to copy it - I made gestures with my hands and yelled at the top of my voice but without much success.

I remember another such incident which took place a couple of months later when a young man, I think from Pinsk, came to Stoibtz to gain support for Zionism. Once again the Rabbi did not want to allow it, and also this time, Itshe moved slowly to the Rabbi's corner speaking constantly:

“Did you see such Chutzpah, such disrespect for G-d? A young man, a shaven man, should dare to stand before the Holy Ark?”

“Let him speak on the big Bima” the Rabbi shouted when he heard Itshe's words and again as before, he left the Shul with hasty steps.

The young man quickly jumped on to the Bima and without delay began to bombard the audience with the following words:

“These are the orthodox, the religious, who shouted 3 times a day to G-d: “May our eyes witness …” (a return to Zion) and even louder they shout: “next year … “(in Jerusalem) and when a Jew comes and wants to talk about a return to Zion, he is not allowed to speak. This is what you can expect from the orthodox. Tell them, the orthodox that … .”

“Villain, scoundrel, rogue!” Voices were heard from the, right side of the Shul “down from the Bima you scoundrel, if not I will come and drag you off immediately”. A big commotion broke out and the crowd was pushing forward to see who the person was, that was shouting. They saw a furious Jew, red like a beetroot who did not have even one hair on his head and was still screaming in a shrieking voice:

“Villains, why are you silent? Drag him off the Bima, throw him out of the Shul, the scoundrel!” A few leaders of the community came close to the screaming man and wanted to know why he was ranting at the young man.

“You did not hear? Such Chutzpah, such a rascal! Did you not hear him calling the whole Jewish community, oxen?”

The crowd then realised that what the speaker mentioned a couple of times was the word, “orthodoxen” - and he, the screaming man thought that he was calling the Jews oxen. The Jew also had a speech impediment and said a “g” instead of an “r”, so instead of “parches” (vulgar) he said “pagches”. With great difficulty they managed to persuade the angry man that the speaker used a new word that he doesn't understand, which means religious and has nothing to do with oxen. With difficulty the man calmed down and the young man delivered his speech, to which the audience listened in silence.

This was the state of affairs that existed at that time - 65-70 years ago. Although there were indeed Rabbis and learned people there was still considerable ignorance amongst the Jews at the time. At the same time a labour movement began amongst the workers in our town - especially amongst the seamstresses. The first of them was Chaya, the daughter of Mordechai Isaac the wine merchant (Gershenowicz) - an intelligent girl from a well-respected family who wanted to learn a trade. Once she started working she realised what it was like to work a 15-16 hour day; sitting the whole time with a needle and sewing or constantly turning the treadle of the sewing machine that caused swelling of the feet. Little by little she began to speak to seamstresses from other workshops about improving their work conditions.

One fine Sunday the first “strike” by the seamstresses broke out in the shtetl. The demand was for a 12 hour workday. The fact that the girls went on strike, stirred the entire shtetl. The community leaders created an uproar: What a cheek of the young women - striking! And when? Exactly on the eve of the non-Jewish holidays when the businesses are inundated with orders. Others even threatened: let us travel to the governor in Minsk and he will teach them a lesson - they will gather them in black wagons and will send them beyond the “mountains of darkness”[7] in exactly the same way that they sent the female student.

They told the story of the female student as follows: people saw a black covered wagon approach her grandfather's house and 2 policemen with sabres came out of the wagon and went into the house. Then they escorted the student out of the house, put her into the wagon and “off they went”. To this day no one knows what happened to her. However, all the threats and stories did not scare the young women. The young tailors took the young women under their wing and guarded them in case strike breakers showed up. The girls stood firm and resolute until they won the strike. And that is exactly what happened: On the 4th day my sister Raizl, until recently a former worker, called together her 8 co-workers and gave into all their demands. Immediately after this incident all the others gave in to the demands of the strikers and at 8 o'clock on Thursday morning, all the girls were already at work. The workday stretched until 8 o'clock in the evening. With this victory, the first strike in our shtetl ended.

[Page 204]

|

|

Standing from right: Berel Moshe Riser, Aron Isenberg, Chaim Dvoretzki Sitting from right: Mordechai Machtey, Noach Berel |

At the same time the first sprouts of a labour movement began to creep out among the Jews. After the first strike, there were further strikes amongst the tailors, shoemakers, carpenters and other trades. Now having won a little more free time for the workers, the town's intelligentsia opened an evening class for workers. They rented a house from Rayne Berl, Chashe Brynes (Tunik) and invited all those who wanted to learn Russian. The teachers were students who came home for their vacation. Thirty five girls registered and every evening - from 9-10 o'clock, they were taught to read and write Russian. The Zionists also began to lure young members. They organized a larger group of young men to learn Tanach (Bible). Every Shabbat, after eating tsholent, we gathered in the house of Yoshke Berke, the son of Henye the baker. There we listened to lectures about the Tanach and Jewish history. Besides the 4 sons of the owner of the house, 20 to 25 young men used to come together: Nache, Pinye, Noach and Berele, Maishl the bookbinder's son, Noach Paromnik, Hershe Yossl the son of Shye Kagan, Berel Moshe the son of Shmerl, Maishl Shmuel the son of Yeshaia, Mirski, Yossl Leib Tsurilnik and many others. The lecturer was Chaim Tshornogubov, a very nice young man with a smiling face - he used to teach chapters of Tanach and provide explanations of dates in Jewish history according to the interpretation of Graetz[8]; and so a whole summer passed.

One day, in the middle of summer when I came home for dinner, I saw my older brother Leibtshe dragging himself in with 2 large and heavy packages. He was dragging them from the entrance to the attic. I wanted to help him but he pushed me away: not your business! When I came home from Chayder, I climbed up to the attic straight away. I rummaged through the packages and discovered a treasure of Jewish books - over 50 volumes: Yossele, Hershele from Dinnenzon, Fishke the Lame, The Tax (on kosher meat), The Mare by Mendele Mocher Sforim, My Friend's wife and other books by Emil Zola, Ivan the Fool,

Tolstoy's Kroitzer Sonata and tens of books by the American publisher I.M.Hermolin. In Hebrew “Wanderings in the paths of life”, “The Burial of a Donkey” by Peretz Smolenski, “Love of Zion”, “Amnon and Tamar” by Avraham Mapu; also a large number of books in smaller format by Sh. Frug, Y.L.Peretz and others. Going through such a mountain of books, my eyes opened wide in wonder. I thought that my brother did not understand because the books were in fact, my business.

From that very first day when the Jewish library opened in Avraham Meir Borsuk's house, I was a subscriber - one of the first boys who brought in 20 kopeks deposit. The library was open on Tuesdays and Fridays from 1 to 3 in the afternoon. The librarians were: Manye Rubashov, Malka Tsirulnik, Shayne Epshtein, and Peshe, the granddaughter of Elkanah Shmerl. Generally, intelligent, educated young women keenly volunteered to take on any work whose purpose was to spread knowledge and education among the youth of the shtetl.

And now back to the books in our attic. First of all I chose 5-6 larger books and a few smaller ones and hid them in another place in the attic. As soon as I had a free moment, I was in the attic reading diligently. When I finished reading the “borrowed” books, I put them back in their place and took others until, in a short time; I finished reading all the books. In one of the books I found a removable coupon from the post in the name of Michael Rubin and it became clear to me, where the books came from. Michael was the older son of Ya'akov Isaac Rubin. His father was the chief manager of Heller's forest industry. His forests stretched from Stoibtz to Volozhin. After he finished the Re'al school, Michael studied engineering and was one of the students who in those

[Page 205]

times reached out to the masses. He was however, not the only one - there was also Berel Ivianski the son of Motl, Alperovicz, the Russian teacher, the pharmacists from our pharmacy, Leibson and Vilentshik. Those mentioned here and a few others were the ones who managed the evening courses and who bought a large number of Yiddish books and donated them to the library - because until then most of the books were in Hebrew.

The evening school expanded so much that on Shabbat and the festivals, the young women and a few boys would meet in the classrooms. There they would also sing songs, read books and sometimes even dance. The objectors in the town protested loudly such “self-indulgence” as they could no longer bear such immodest behaviour, and one day - I think it was the 2nd day of Sukkot - a few of them forced their way into the home of the Russian teacher Alperovicz, ordered him to pack his belongings and leave the shtetl. A horse and carriage, they told him, was already waiting for him outside. Having no choice, he packed his few possessions and the books, got into the wagon - accompanied by curses and abuse from the fanatics - and forcibly taken to the train station, never to return again.

These persecutions did not stop the work of the movement. The movement moved underground, rented rooms clandestinely and continued to conduct classes in smaller groups of 10-12 members. On Pesach, 1900, a few tailors came home from Minsk and reported that in Minsk the workers are free to strike and they hold their meetings in the “Paris” hall and no one bothers them.

This happened at the time when Manye Vilbushevicz, Sasha Tshemerinski and Aleksander Vollach were arrested in Minsk for their political activities amongst the workers. When they brought them to Moscow for a hearing, the colonel gendarme, Zubatov, persuaded the court to allow them to hold legal economic strikes, demanding a 12 hour work day and higher wages, on condition that they refrain from political activities and stop promoting political propaganda: then the police will not interfere in their economic struggle. (And for this trick, Zubatov later became famous). They allowed themselves to be persuaded by Zubatov and on their return to Minsk they proclaimed a new “Independent” party. They rented a place in the “Paris” hall on Romanovske Street and began a branch of legal activities among the workers.

This was the news that Leibe, the black one, and Leib-Arke Boruch, the son of Muller - both good tailors - brought us, as has already been mentioned, when they arrived for Pesach from Minsk. They were very keen to establish something substantial for the local Stoibtz workers but what could be accomplished locally when there was not much work available? So the 2 fellows came up with an idea: They will start a fire in the shtetl. The plan was

|

|

[Page 206]

simple: if half the shtetl burns down, there will be work - and the workers would have an opportunity to strike.

And from words to action: The two young men got together with a couple of carpenters and locksmiths and one night they went off together and started a fire in Yashe the Commissioner's granary that was filled with cases of matches, tons of kerosene and other merchandise of that kind. Suddenly - before they managed to run a significant distance from the danger - the large bell of the yellow church began to sound the alarm. The town woke up in fear, the Fire Brigade with Salye the son of Benye at its head, arrived swiftly with “hoses”, ladders and axes and it did not take very long to localise the fire. The granary with all its contents burned down - but nothing else. The arsonists could by no means understand how it happened that the bell had already sounded the alarm before the fire could spread as it should have.

In the morning the entire incident became clear: Tevele the deaf-mute water carrier who used to provide his customers from half the market place with river water for tea, usually started his work at 2 o'clock at night. His “water route” used to begin with: Motl Ivianski - Yoel Gintzburg - Molye the son of Hertzke - Elye lal Shulkin and he used to finish with Yashe Neufeld and Chaim Yonah the innkeeper. He would complete his round with these business owners by 4 o'clock in the morning. From 4 he used to provide his services to the other half of the market place, from Rishke Henkin and Leibe the carpenter's drawer of water. He was walking in the night, the yoke with the 2 heavy buckets of water hanging over his shoulders, humming his usual a-eye-a. He came to the river, filled the buckets and walked back to the houses - backwards and forwards until he reached the house of Elye Shual Shulkin's house and there he saw a bizarre scene: people were standing and striking matches one after the other … but when he saw the small fire, he left the buckets standing on the porch and ran like a whirlwind to the church and pulled the bell. As he was running he saw the arsonists running away. One of them had a limp.

In the morning Tevele told everyone in his own unique stuttering language: “See with eyes, strike a match, and house burns” … . and when he imitated how the fire lighters ran, everyone understood immediately according to his signs, who the men were, that started the fire. The story began to go from mouth to mouth until it reached the town's official. Without thinking too long the officer and his 2 policemen went hurriedly and arrested Elye Yonahanan, the father of the blacksmith and Leib Arken, the son of Boruch the bricklayer, brought Tevele the witness and he confirmed that he saw them “light up and run”. There were 2 others with them but they managed to hide.

In the meantime the town's official detained the 2 men in a cell and stationed a policeman with a stick at the door. Then he himself went in search of the other 2 criminals. He decided to send the 2 detainees to Minsk early the next morning but the 2 detainees did not wait for the officer's invitation; instead they contacted Yehoshua Shashes the agent who arranged for a coachman, 2 horses and a wagon and at 11 o'clock at night they arrived at the prison and with large blacksmith's hammers, broke open the wooden door. By the time the policeman with the wooden stick woke up from his drink-induced sleep, all 4 were already sitting in the wagon and the swift horses were already on their way to Baranowicz, to Anekshtein, the chief agent; from there to the border and - away to America. With this incident the adventurous attempt to create work and organize strikes, came to an end. In the shtetl itself and far into the surrounding towns, they continued to tell and whisper for a long time, about the shrewd work that the friends did to the town's official.

No one could stop the movement. It grew from day to day. New members continued to join. The organisation was built on separate small circles and small groups with representatives from the leadership. The members of one cell never knew the members of another cell. One could only see various groups of people walking on the promenade on Galachsher Street. There they spoke and discussed in subdued voices, a variety of subjects: Zionism, Socialism, strikes, boycotts etc. The representatives used to collect membership dues, distribute “literature” amongst the members, legal and illegal brochures, small books, printed with small letters on very thin paper, for example: The story of the 4 brothers, The working Day, The wages, The essence of the Lasal constitution, The biographies of the old National Party, Ivan Kozsuchin, Zselechov, Sofia Peravskaya, Balamashov and others; how Count Kropatkin, the anarchist, escaped from Shlisslburger Fortress; how Grigori Gershuni escaped in a barrel of cabbage, and similar books. From the Minsk committee we still used to receive: “The worker's voice” from London, “The future” from America. The literature was passed from hand to hand and from cell to cell.

[Page 207]

|

|

After Pesach 1901 the leadership decided to call a general meeting of all the “acquaintances” and “Babbes” (a secret sign for male and female members). On all 4 roads leading to the Zadvorier forest, a row of patrols was stationed. Each representative led his group to the forest on a different path. Prior to the meeting they found a clearing in the forest surrounded by old dense trees. That was where the general gathering took place. People became acquainted with one another, presented speeches, sang songs and enjoyed themselves.

This secret meeting was also attended by the intellectuals: Itshe Mordechai Isaacs, Michael Rubin, Berel Ivianski, Malka Tsirulnik, Shayne Epshtein and others. When the “meeting” ended everyone returned to the town in the same order that they arrived. And from that day on, meetings such as these took place almost every Sabbath in various surrounding forests: Siniaver forest near Shverzne; Akintshitz, Artiyuchi and even in the Nikolyeshtzinne, 10 viorst from the shtetl and Atialles. In the winter meetings took place in secret apartments: At Rayne, at Libbe Grivkes, Ozer Kivves and at Berel Hayshke the butcher. There they taught reading and writing and studied the political economy of Smirnov and Kapital by Karl Marx etc.

In the summer of 1902, the Bundist party organisation numbered over 100 active members and a large number on the periphery who identified closely. They began to prepare for the celebrations of the 1st of May and also to organize a self-defence group. This just happened to be after the shoemaker, the hero Hirsh Lekert, made the well-known attempt on the life of the Governor-General of Vilna, for which he paid with his young life.

The movement started in the surrounding villages. A strike of tailors and seamstresses broke out in the town of Mir which lasted a whole week, without result. We received a request from the Minsk committee to send a couple of our representatives to Mir. We arrived early on Saturday and immediately met the leadership: Yosef Leib the Turner, Tzinkin and others. A general meeting was called in the Miranke forest where the strikers were addressed and encouraged. The leaders, sensing the high spirits of the striking workers, called our representatives on Sunday and we consented to a 10 hour workday and payment for the days of the strike. Similar strikes also took place in Nesvizh, Garadzay and other places. We then established a bond with Baranovicz where a strong “Bund” organisation existed with Alter the Turner and others in the group.

[Page 208]

At the same time a significant part of the Zionist party broke away under the leadership of Ber Borochov (may he rest in peace) and established a new party under the name of *”Poalei Tzion”. Then a teacher came to us in Stoibtz, Zalman or Zelig Rabinovicz - “zar” - a very intelligent young man and a good speaker who attracted a significant number of the Zionist youth to the new party: Nache, Pinye and Berele sons of Slovve, Zalman Rubashov, Feigl Shapiro and her sister, Yessl and Leizer Riser, Baylke Tzechanovicz, Rozze and Soltshe Ginzburg and a few other well-respected young men and women. Besides them there were a few tailors and shoemakers who worked in their parent's businesses.

As they had little to discuss with the General Zionists, they turned their heavy artillery against the “Bund”. For this purpose they would convene general meetings where the best debaters from both sides were presented to discuss their political policies. Each side tried to persuade the listeners that his policy is entirely true and his party is the best. After the debate the representative of each side returned to his camp. The Poalei Tzion[9] received a certain level of popularity when the Tsarist government declared the new party illegal and arrested a number of the party's leaders, among them Vladek (Baruch Tsharni).

Vladek was an exceptional orator-agitator who was crowned with the additional title “Lasal the Second”. While in prison, the so-called Socialist University together with a large number of political prisoners, discussed the policies of the various parties for so long, until one day Vladek declared that he is leaving “Poalei Tzion” and crossing over to the “Bund”. Among the political prisoners were also Baruch Teper and Sascha Tshemerinski (the last mentioned did penance for his sins with Zubatov).

A General View of 1905

The stock-exchange on Galachsher Street became too small to accommodate the large mass of youth so it was moved to the market place. For strictly secret meetings and discussions they still used the old stock-exchange. So the 2 labour movements were both in the same Jewish street - and in our shtetl - Bund and Poalei Zion - moved ahead with the usual revolutionary pace of the entire, enormous Russia.

A new page in the history of the Russian revolutionary movement was opened on the 9

This demonstration was the first signal that brought about a wave of open dissatisfaction among the liberal population and revolutionary turbulence among the factory workers. Hundreds of appeals and proclamations were illegally printed and distributed across the length and breadth of the Russian Tsarist Empire, in every town and shtetl. Also in our Stoibtz we published a graphic proclamation in which we challenged the public to participate in a political strike.

On Shabbat the 15th of January we called a meeting in the Zadvorier forest where the speakers enlightened us and described the political situation in the country and called on workers to be prepared for a general uprising in the whole of Russia. In every little corner of the land the mood was restive, like pressure building in a boiler. Everyday couriers used to come to the shtetl to inform the working masses of the great news about uprisings and demonstrations in Moscow, Kiev, Odessa, Cherson, Warsaw, Bialistok, Lodz, and Riga, Kovno, Vilna and others. The army and the police met the open demonstrations with fire. In the streets of many towns, barricades were erected and many lives were sacrificed. The hospitals were full of wounded workers and the prisons were being filled by arrested revolutionaries.

The main strength of the revolutionary movement could be seen in the might of the 1st May celebrations: in all the towns and villages of the great land, the working masses went into the streets demonstrating and for the first time, openly celebrated the worker's holiday, waving red flags and banners, on which were written the needs and slogans of

[Page 209]

the Proletarian parties. The life of the entire shtetl came to a halt. All the mills, factories and workshops were closed, also all the bakeries and shops were locked up. Even the horse-drawn coaches, the cabs, the trams and other means of transport in the towns came to a standstill. Everything remained quiet but in a few cities real street slaughter took place between the army, the police and the workers.

The following morning an order came from the revolutionary labour committees, to go back to work. The factory chimneys were smoking once again, the machines in the factories were clattering and all workplaces and stores were open. Once again a normal life began, as normal - as the abnormal time of a revolutionary period can appear. The underground movement attempted to crawl out from her underground position and be seen and heard in the broader public arena. This situation stretched throughout the entire stormy summer until the end of September when the revolutionary labour committee decided to call a general railroad strike.

I considered my personal position and decided that in such turbulent times, it was not fair of me to remain in the shtetl. And with only 15 kopeks in my pocket, I sat myself down in the train - without a ticket - and went to Minsk. Once there, I immediately threw myself, body and soul, into party work amongst the Jewish working masses. I went from one factory to another calling upon the workers to strike in the streets and to close the stores that still stood open. A few days passed. On the 5th October at 10 o'clock in the morning, the famous manifesto of Nikolai was proclaimed and was distributed in a few minutes in tens of thousands of copies. The manifesto was printed in huge letters beginning more or less as follows: We, Nikolai the Second Emperor of all Russia, King of Poland, almighty ruler of Finland and so on, have decided, with G-d's consent to command that the representatives of the Duma (Parliament) should convene, elected by my faithful subjects, by general, fair and secret ballot, and so on.

In a few moments the houses emptied. Whole families filled the streets. Spontaneous demonstrations formed. The first thing we did was to join the demonstration at the jail on Yuriever Street. The heavily fortified gates of the jail opened and all the political prisoners were released all at once. The masses rejoiced and called out “Let freedom live” and were carried on high with song, from the Marseilles, Varshavianka and other revolutionary labour songs. We marched together in closed ranks to the upper market place where thousands of people had already gathered. From there everyone marched together through Franciskana and Zacharevska streets and turned toward the Vilna railway station. At the steps of the station we were met by a whole row of soldiers with guns extended and ready to fire who, without warning, fired 3 volleys into the 50,000 mass of people. It turned into a bleak turmoil and people ran in alarm, trampling one another. Many were killed and many more wounded - this was supposed to be the first day of “winning” freedom.

In these turbulent times, the Black Mafia (Black Hundred) saw for themselves a good opportunity to spit out their Jew-hatred that had been gathering for years in the darkest of their intestines. Daily their reactionary newspapers “Novoye Vremya” (“New Times”), “Kievilianin” and other newspapers, through the foul mouths of their editors Krushevan, Suvorov and all the other collaborators, poured fire and brimstone on Jewish heads. The Black Hundred stirred up the mob and exploiting the turmoil, organized pogroms in Zhitomir and Hommel. The truth is that they immediately encountered substantial resistance from the Jewish self defence unit. Yet the losses in souls, possessions and goods were substantial. When the hooligans, under the protection of the police, committed murders, plundered and robbed, there was a growing fear that the pogrom-plague would spread to other towns and villages.

With regard to such an eventual possibility, my first thought was for my own home town, Stoibtz. I immediately turned to the Minsk committee of the “Bund” and received 6 revolvers. Now the question arose: How does one transport the package of weapons when Minsk was then like a besieged fortress, where on every street corner there were soldiers and police patrolling? It was an enormous risk but I decided to take the package with me and by using various roundabout ways and cunning ideas, I got through the entire road - from the high market to Romanovska Street - in peace. I entered the Stoibtz inn where Yoel Tunik was already waiting for me with his horse and wagon. I sat down with my “package” and off we went - home. We arrived very early and a little later I called a meeting at the market place near the Volostnye Pravlenye (circle committee). A large crowd came and I told them about everything that had happened recently, as well as about my personal experiences.

From there we

[Page 210]

began a large demonstration of over 1000 people, through the market place, Minsk Street and back through Yurezdikke Street to the market place. Our first free demonstration ended without incident.

Freer winds began to blow. The movement came out of its hiding places. We opened a worker's club in the home of Hershl Dvoretzki in Rumovver Street. All Dvoretzki's 5 sons - Yisroel, Leib, Chaim, Yossl and Zissl Yitzchak were active members but it was mainly Chaim who excelled. Every evening we used to meet in the club and one of the friends would give an overview of the daily political events, or report on the forthcoming elections to parliament. We set up a dramatic circle with Arre Getze the carpenter's son - by profession a wig maker - but also a good singer who used to take the lead roles.

The general population in Russia as well as the Jewish population now leaned towards the Liberal, Civil and Labour-Movements in the country; but the shadow of the Black 100 still lurked over the Jewish towns and villages. The Jewish socialist parties, fearing the possible outbreak of pogroms, devoted a lot of time to organising self-defence units. In Stoibtz our locksmiths prepared a large number of rubber and wire whips and lead-filled “gloves” etc. while the carpenters made thick hollowed sticks with daggers fitted into the hollowed spaces - and other types of “weapons”. The wooden sticks were well polished so that no one would suspect what was inside.

Overall we had a considerable number of “cold weapons”, possibly more than necessary but where could we get hot weapons - revolvers, rifles? At the time those weapons were scarce and we needed a minimum of 2-3 guns in each unit - this meant a total of 50-60 pieces - and that would cost a fortune - so where do we get the money? At that time the land cultivation office used to allot various pieces of forest land each year, “plots”, and sell them on auction to the forest merchants. Prior to the auction the merchants would send out their managers to measure and count the number of trees in each plot and then work out how much they were worth. Then the traders got together In Minsk, for the auction, and there the bidding began and prices rose. Sometimes it would happen that the prices were driven so high that the poor merchant bidder, in the heat of the moment, would lose his money, other people's money and even - his underpants … .

In that year when the date was announced for the sale of the forest plots, the merchants considered the following: perhaps it would be a good plan that the leadership of the bidding should be taken over by the young parties in the town, because the delegations of these parties were good. Said and done: a secret meeting was called with the representatives of the “Bund”, “Poalei Tzion” and a new party ”Dergraycher” (Achiever) that had organized itself at that time. It was decided that only a few merchants should travel to the auction together with one representative from each party, but on the appointed day, a greater number of merchants attended, than planned. The representatives from the parties were: Nache Kushnir from “Poalei Tzion”, Hersh Dvoretzki from the “Dergraycher”, and I - from the “Bund”. We worked out a specific procedure of how to conduct ourselves so as not to arouse suspicion that we were all working together. We agreed on how much the maximum prices should be. The auction went very quickly and we all went home pleased.

A week later all the merchants gathered in the Rabbi's house to “settle”. There each one could suggest prices according to his calculations and discretion. Also this resale brought in an extra 1200-2000 rouble which made everybody happy. The extra money was supposed to be divided - 1: amongst the merchants who did not manage to buy plots 2: for the towns necessities: “Bikkur Cholim” (visiting the sick), “Gemillut Chesed” (Benevolent Society), “Linat Hatzedek” (lodging for the poor) and other societies as well as for the synagogues, the schools and other important institutions in the town, and 3: for the participating political parties. According to our agreement all the political parties were supposed to receive a considerable portion of the surplus money because there was a need to cover the cost of self-defence. And here the worst happened: When it came to the division of the money, the parties were completely forgotten. So we called a general assembly of the party-committees and decided to send a deputation of 2 members to those responsible for dividing the money, and to demand the portion to which we were entitled.

When Nache and I - the 2 party representatives - arrived at the meeting, where 7 leaders of the town sat with the Rabbi at their head, we told them that they did not deal fairly with our parties and that we were not there to ask for money for ourselves personally but for the needs of the community, for a national Jewish cause. We also explained that our members were prepared to sacrifice their lives, spill their young blood for Jewish honour and for Jewish

[Page 211]

property and goods, so how then, can you - Jews with long, kosher beards - defraud us in such an ugly way after we all understood that the surplus money would be shared according to the law?

We presented our rightful complaint calmly and logically but suddenly one of the merchants jumped up: How dare you force your way into a strange home and embarrass elderly people. We will call the police immediately and they will show you where your proper place is… . Out of here rascals! Loafers!

Not wanting to inflame the mood and making too great a commotion, we left, embarrassed by their vile behaviour and at the money-exchange we reported the fine reception that they had organized for us. That happened Thursday evening. The following day in the early morning, they spread a rumour in the shtetl that the young men from the parties attacked the Rabbi and the leaders and wanted to re-allocate the community money. On Shabbat morning, in the big synagogue, the Rabbi walked onto the Bima after the reading of the Torah and called out: “in the name of the Rabbi and the community we excommunicate the young men and their families and no Jew can have anything to do with them” and the Rabbi descended from the Bima happily. But remarkably when the worshippers were leaving the synagogue, every passing Jew came over to us to bring a warm “good Shabbat”! Many even squeezed our hand with acknowledgement.

The news of the ban spread through the whole town like lightning. All the Jews were shocked. All the Jews from Yurezdikke Street, from the street of the synagogue, from all the small prayer groups, as well as those from the side streets, came to the big synagogue for Mincha and in one voice demanded that the ban be removed immediately. Among the large congregation of Jews, were also a few of the forest merchants with whom we made the agreement: Mr. Leib Rubashov, Yoel and Hirsh Ginzburg, as well as the 2 Zionist leaders, Maharshak and Alter Yosselovicz, and other important leaders. After extended negotiations it was announced from the Bima, immediately after Havdalah, that “in the name of the Rabbi and the leaders of the holy community of Stoibtz, the ban is declared null and void and the young men are cleared of any mishandling or arrogant behaviour”.

That same evening a meeting was called at the home of the Rabbi, once again and there it was decided to allocate 200 roubles to be divided proportionally among all the political parties, for the purchase of weapons. There was one condition however, that the guns should only be used in time of danger G-d forbid, and that it is forbidden for the weapons to be used for other purposes.

We purchased the necessary quantity of weapons and organized fighting-units. A group leader was assigned to every 15-20 members. They established strict disciplinary measures and in groups they went into the forests to learn to shoot. Then we joined forces with the surrounding villages and sent them our instructors. We also mobilised all the town's wagon owners and we had over 200 trained and able fighters who were ready to fight at a moment's notice. The “Poalei Tzion” also had their units and the rapport between the parties was friendly and cordial. And now, after over half a century, when I scratch into my memory and do some soul searching, I come to the conclusion, that only due to good tactics, strict discipline, excellent organisation and friendly, coMr.adely relationships, did we manage to avoid greater excesses, pogroms and robberies in all the towns of the province of Minsk. We knew from our reconnoitring units that the Black Hundred was preparing to launch pogroms in ours, and other towns, but overnight we already stood guard in a wired area. Long before anything happened, our spies could already detect the place of danger and any possible sign of an attack was stifled in time. Little by little, life in the town settled down, that in those times and circumstances could be called normal.

The elections to the Duma took place in which a certain number of Jewish representatives were chosen from Minsk, Vilna, Grodno, Bialistk, Kovno, Warsaw, Lodz as well as from other large Jewish communities. A Jewish faction was formed in the Duma but its impact on general politics was insignificant, also as far as the government policies relating to Jews, it had little impact. A few party newspapers appeared on the Jewish street but too often they were confiscated or closed altogether but on the following day, the same newspaper would appear under a new name and with a new editor. The Jewish labour movement was at a stage of being part legal and part underground.

The political activity of the movement was primarily concentrated in the clubs. A large portion of the active workers were devoted to perfecting their general education. My worldly education was very limited: I learned Yiddish and a little Russian with Velye the teacher for 30 kopeks a month. Besides that I learnt Yiddish from

[Page 212]

a “letter writer”, Russian from the 3 parts of the “Ruskaya Retsh” (Russian Speech), a bit of Arithmetic: addition, subtraction, multiplication - until division. I learnt Hebrew with Yitzchak Esterkin in “cheder” from the book “Moreh Halashon”(The Teacher of Language). Finally I decided to sit down with my study books and cram. In retrospect, I was helped considerably by my great acquaintance with the Rubashov family who moved to Stoibtz from the neighbouring town of Mir, at the beginning of the 1890's. Mr. Leib Rubashov was a tall, lean Jew, with a fine, black, imposing beard. He was a forest merchant who devoted a great deal of time to study and spent most of his time reading books. His wife Santze was a highly educated woman both in Yiddish as well as in worldly matters. She knew the whole Tanach well, the “Shulchan Aruch” and even understood a section of Gemorrah. All the children were intelligent and gifted. All the daughters studied and the older son Zalman studied with me for 3 terms with Yakov Meir the teacher. After that I went to study with Itshe Tanchumes, and Zalman went to Mr. Yakov Meir the emissary for a further 3 terms. As there were no longer any other more-learned teachers in the shtetl, Mr. Leib Rubashov decided to ask the interpreter at the shtiebl - a young man, a scholar, dedicated to the study of the sacred books, to study for a couple of hours a day with Zalman and a few other boys. With regard to this he informed my aunt Sarah that he wants to see me. I entered the Rubashov's beautifully furnished home. In every room stood cupboards with books, and Mr. Leib was sitting at the table with a silk yarmulke on his head. With a smile he asked me what I had already studied. I answered: Tanach and Gemorrah. He took out a small, comprehensive Tanach and read out a few verses from various passages; he also asked me a few questions from the gemorrah. When I answered everything, pointing out, in addition, in which section of the Bible and in which chapter the verses could be found, he asked me to tell my father that he would like to see him because he wants to discuss a certain plan with him. After his discussion with Mr. Leib my father did not approve of his plan for me to study for only a few hours a day.

Then I approached the great Talmud Torah (religious school) of Mr. Dovid Epshtein, Mr. Eliyahu's son-in-law, from the school in the Minsk and Mir Yeshivot. Zalman studied Bible commentaries with Motl Machtey, a good friend of our community. Rubashov's daughters all studied in the big cities. Manye completed her medical studies and became a doctor of midwifery. Katye and Vitke finished High School with distinction and in between - from the time they matriculated until they entered university - they

At the beginning of 1907, Mr. Leib Rubashov moved to St Petersburg and at the end of the same year, the remaining members of his family joined him. Katye studied at the Moscow University where she completed her medical studies and practised there. Radl became ill in St Petersburg and passed away there. Vitye and Avromtshik also studied. Avrom completed his medical studies and in 1917, after the revolution, Vitye was appointed professor of the psycho-analytical faculty at St Petersburg University.

At the end of 1910, I was called up for military service in the Russian army. At the end of 1913, after 3 years of service, I was released from the army. During this time, life as well as people, changed completely. It was difficult for me to adjust to the newly established environment but before I managed to shake off the many years of grey military life, Tisha B'Av 1914 arrived, and the First World War broke out. Once again I was in uniform, with a great coat, a fur hat, a gun on my shoulder and cartridges wrapped around my hip. On the 3rd September, we marched into East Prussia and reached Konigsberg and - then - we turned back to: Lithuania, Poland, Galicia, Ukraine and finally - Russia.

[Page 213]

For 2 full years, I did not sleep under a roof. In heat and rain, cold and snow, hungry and thirsty, we marched from one position to another, from one ruined town to another, from ruin to destruction, until one day, at the end of 1916, I remained lying on the battlefield, having fainted, and covered in blood. In this condition, German medical field-workers picked me up and took me to their field-hospital and then sent me to a prisoner of war camp where the hunger was unbearable. From then on I wandered from one camp to another doing various hard labour tasks. One day when they chose 30 Russians and 10 Frenchmen and sent them to a village to do field-work - I was among the fortunate ones. There we recovered a little. In the field we used to gather sorrel and other grasses and fill our pockets with potatoes, beetroots and radishes - cooked them all together and enjoyed ourselves … Besides that we also used to pick cherry leaves from the trees, dry them and then grind them and roll them in newspaper (as cigarettes). One day before Rosh Hashanah in 1918, I received a parcel through the Red Cross: 5 bars of chocolate, 10 packets of cigarettes and 5lbs of sugar. I could not believe my eyes. Who could have sent it?

On the 7th of November 1918 peace was declared. Immediately the participating governments began to repartiate all the prisoners to their homes. During this entire period I hid my little bundle of Russian coins, with only one hope, that as soon as I enter the first Russian railway station, I will first of all, buy a pound of white bread and a couple of bagels. But all my hopes were dashed when I saw starving Russian towns and the poverty at every step. The needs of the entire population knew no bounds. The trains moved slowly like turtles. The train crept forward a few viorsts and from the lack of heating materials there was no steam in the locomotive and the passengers had to go to the trouble of dragging wood from the nearby forests. For 15 days we dragged along until we reached Stoibtz.

And here I saw the great destruction of my home town. The town was completely destroyed by fire. The inhabitants moved into temporarily shelters made of wooden boards knocked together. The hunger stared out of each one's eyes and poverty whistled in every little corner. The Poles proclaimed their independent state and even wanted to take White Russia under the protection of her wing… . A new little war was blazing between Russia and Poland. The Poles sent their “armies” from Galicia and north of Poznan - they were bands of criminals and lawbreakers who robbed and terrorised the civilian population, beat up and killed Jews, cut beards and carried out many horrific acts. When the Russians succeeded in driving away the Polish bandits, we breathed more easily but not for long. During this time I wrote a couple of letters to Vitye Rubashov in St Petersburg. She replied immediately and here I discovered the secret of my Red Cross package that I received in captivity: Vitye's father, Mr. Leib Rubashov, of blessed memory, found my name in one of the bulletins published by the Red Cross with names of war prisoners in Germany and sent the above mentioned package.

In the middle of summer 1920 the Poles again gathered a strong army and began a great offensive on the White Russian front. During the attack, they captured all the larger cities in that region: Baranowicz, Bialistok, Brisk, Grodne, Vilne etc. On Shmini Atzeret they marched into Stoibtz. They reached Kolosova - a village 10 viorsts from Stoibtz - and there they signed a peace treaty with the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Gradually life began to normalise. The town of Stoibtz was declared a seat of the province. People returned to open the shops that had been boarded up for a long time. Shopkeepers travelled to Warsaw and Lodz to purchase goods. The shelves in the shops filled up again. The town elected a magistrate with officials and a mayor. The Jewish community also came back to life. Chaim Liusterman was chosen as chairman. People began to rebuild the burnt out houses and the town began to assume its pre-war image.

The new life was however, difficult. The government - in order to balance her large budget - place heavy taxes on the population, especially on the middle-class which was primarily Jewish. The political parties in the meantime, breathed more freely. Each party published a daily newspaper or periodic journal. A large network of professional organisations began to spread all over the country.

The central Jewish school-organisation became very active: opened a network of Jewish Folk schools throughout the country and a teaching institute in Vilna. A Jewish Folk School was also opened in Stoibtz with the support

[Page 214]

of my dear friends Noach Kushnir, Chaim Dvoretzki, Mulye Kaplan and others. About 50 children of working class parents studied in the school with very good results. Things were not only culturally brighter but also in practical areas: an electrical station was built in the town. Jewish performing groups came quite often from Warsaw and Vilna and gave the best performances. It seemed that the social life was becoming more settled and stable but this did not satisfy me, personally.

Russia was shut with 7 locks and no end of limitations for entry into the country, even for Russian citizens who remained outside its borders. I felt a responsibility towards my family - so after I organized my brother Fyve and my 2 sisters Fayke and Zlatte with an income - houses and businesses - I threw my rucksack over my shoulders and left for South Africa.

I started working with my older brother in his men's clothing factory and from South Africa, I continued to maintain my ties with friends from Russia and Stoibtz. I often met with my good friend Meilech Milcenzon and all the other immigrants from Stoibtz when we met to raise funds for the “Gemillut Chesed” (a welfare organisation) and other needs of the town. I also collected funds for the “Folks Tseitung” (people's newspaper) and for Madam Sanatoria (a Jewish rehabilitation establishment) in Otvokts “tsisha” (meaning “peaceful” in Russian). In 1931 the repressions in Russia intensified, the Iron Curtain was completely drawn and their ties with the western world became loose. I lost all contact with my friends on the other side of the Iron Curtain.

In 1934 I married my wife, Henye Norman from Birzsh, Lithuania (previously the Kovno province). I tried to find ways to bring a few members of our family to South Africa. With great difficulty we managed to bring over our brother-in-law Mordechai Pozniak and my sister Raizel. In 1938 we also brought my sister Zlatte's two older boys: Berre - 14 years old and Shimon - 13 years old. We put them into school for a couple of years and they grew up to be fine young people. We also provided our nephew Berre Epshtein with all the necessary documents to come here but upon arrival in South Africa the local government did not want to allow him in: with tears and prayers we managed to persuade the English consul of Northern Rhodesia to allow him to go there. With a guarantee of 500 English pounds

In the summer of 1945, after the victory over the mighty, murderous Germany, that lay completely crushed, we gathered a few Stoibtz landsleit (former fellow citizens of Stoibtz) and established a support committee for the Holocaust survivors, organized by Avrom Russak, his son Yechezkel and his daughters, Yakov Bruk ,the Chesler brothers, Bashke Milcenzon, Yankl Neufeld, Zissl Dvoretski, Nachum Malbin and others. We called on all our landsleit, collected money and sent parcels of food, clothing etc. to Eretz Yisrael.

[Page 216]

have to look for hand-outs. They accepted our advice and established the Gemillut Chesed where, for a fee of 5 pounds every landsman became a member of the fund. We also raised large sums in the following manner: every time a child or grandson was born or there was barmitzvah or a wedding - every landsman who had a celebration donated £5 to the Gemillut Chesed and received a certificate in their name. In this way our small “colony” in the golden land contributed a great deal to the success of this much needed undertaking. According to its balances, it is clear that the Gemillut-Chesed fund grew into a very large institution with a turnover of tens of thousands of pounds.

A significant number of our members - Avrom Russak, of blessed memory, and his children, Yakov Bruk and his wife, Solly Per, Yankl Neufeld and their wives, Bertse and Shimon Pozniak - visited Israel and every one of them brought good news about the circumstances of our friends and acquaintances. In the last few years the work of our Stoibtz society has slackened a little: we get together less often and the meetings are attended by fewer landsleit; yet it is still possible to collect 50-60 pounds from the 5-6 couples that attend regularly.