|

|

|

[Page 478]

by Elye Shteynberg (Paris)

Translated by Tina Lunson

The un-captured Jews who were still in Paris no longer appeared in the open: each one lay hidden underground, and whoever dared to come into the un-occupied area wrestled further with Fate.

I came to Lyon, to the free zone. In the summer of 1943 Lyon was also seized by the occupier. And again the struggle for life went on. In November 1943 I was captured by the Gestapo, that was always pursuing its trade of death.

Tuesday, the 22nd of November, I am brought to Drancy with a large group of Jews. We are counted and checked by the Jewish police aides, who promptly take away one part of our group for deportation the following morning. I am among those who remain temporarily. After going through all the checks I am led into a large room, where there are other captured Jews from all over France. I remain here for 15 days and later am sent off with a group in closed train cars, like all the newly-captured Jews, to the East. The train hauls us in a direction that later became familiar.

Meanwhile we lay on sacks of straw and wait. The chief of the squad wakes us with a whistle, at 4:00 in the morning. It is still quite dark outdoors. We gather our baggage that we had brought with us. Our important valises of things had been taken two days earlier by the SS, who assured us we would get them back at a designated place. We find ourselves in the courtyard of the famous Drancy. We hear the second whistle and we march, altogether 60 people in a group – men, women, children, all crying.

The buses are waiting for us. Each group is stuffed into one bus, guarded by fully-armed French gendarmes with iron helmets on their heads. The old folks from the home for the elderly are also being deported.

Our turn finally comes, they take us to a train line. When we stagger off the buses we see that we are at the Babenia station – a suburb of Paris.

[Page 479]

Our debarkation is under a stern guard of armed gendarmes. We are counted again:

“60 pieces”. The Germans soldiers take us over and lead us to a train boxcar with a printed notice “For 8 horses or 40 people”. The German guards close the heavy iron door.

Outdoors it is dark; the train begins to move. We stand by the see-through cracks and want to see where we are. The train runs past Naze-le-Sec and then stops. When it is really dark, the full train begins to travel at a very high speed. It looks as though the Germans do not want us to travel by day, in order that the French not see our tragedy.

The chief of our train car (Wiess, a French Jew) lights a kerosene lamp that hangs in the middle of the car and we try to arrange some resting places, although it is not possible that everyone can lie down. People change places.

An Arab Jew who is with us wants to get out of the train, he wrestles with the bars of the little window on the outside of the car. The three German-assigned overseers (Jews) are frightened that all the Jews will be shot. All hell breaks loose, all 60 prisoners get to their feet, all are shouting, the women and children weep, the chief argues with the Arab Jew.

Outdoors it gets light and we can see that we are now in German territory. Now there is no question about jumping from the train.

The first night is over, and we wait for 24 hours in the closed train car. The water in the buckets is long gone and now people use them for their natural needs. Men and women empty their bowels; the buckets run over and we, 60 living creatures, suffocate in the horse wagon.

It begins to get dark again, and we do not know where are they taking us. Everyone is embittered and again tries to prepare some resting places but there is no space, and everything is wet. The pails are full. The elderly who are traveling with us soil their clothes where they stand or lie. The second night is much worse than the first. The train speeds, and there is no place to lie down. We have made a place for the women, children and old who cannot stand up. We all stand on our feet the whole night and the sun looks in on our stinking wagon, where we are shut inside like cattle. The women and children cry; there is no food for the children, no diapers – everything is wet, cold, everyone is smeared with filth.

[Page 480]

After 48 hours of travel the train comes to a stop. A German opens the door of the car: “Come down with the pails!” he orders. Weiss does the work unwillingly. He comes back to the train and says with a bitter attitude we are going to the East. The door is closed again.

The train runs at top speed. We travel past German cities, we can see people in civilian clothes through the cracks; the women and children continue to weep. Night comes again, and again people lie on the wet floor of the wagon. Thus the third night.

It is Friday the 10th of December 1943. We stand up and look through the cracks and see snow-covered fields, everything around is white. Now it is four days since we have sat in these closed cars, not knowing where they are taking us.

The train slows down and stops. We can hear the wild bellow of the S.S.: “Get down! Out quickly, out quickly!”

We crawl out of the train. The whiteness of the snow hurts our eyes. The violence of the S.S. drives us, we are confused. The Nazis leap around us and never stop shouting “Louse, go faster! Louse, make it quick!”

When everyone is finally out of the train with their packages they tell us to pile them all in one heap, even the baby bottles. They arrange us into two rows: men separate from women. Everything must be done quickly, and the dog-like yelping of the demons goes on. Now we are standing in two rows. Three Nazis arrive, in military clothes with many medals on their lapels. One of them makes selections – to the right, to the left. In a little while the selection is done.

We stand, the selected are crammed into the waiting trucks that take away first the women and children and then the men.

Now comes our turn. We are stuffed into the trucks and taken away. Not long, and they tell us to get out. We are at a camp building for the sick, between two barracks. The sick see us through the window, and they stretch out their withered heads. We see three rows of beds, one against the other.

We stand in a line. Soon an S.S.-man comes to us and roars like a tiger: “Undress and remain standing.” He does not stop screaming: “Undress and remain standing naked!” It is terribly cold outdoors, the snow

[Page 481]

is up to our knees, we begin to undress but it is not fast enough for them, and they beat us over the head with clubs.

We arrived at 10 in the morning and it is now three in the afternoon. We stand. In the evening they take us to a wash room. An S.S.-man demands that we surrender everything that we brought with us; when someone wants to hold something back he is shot. We listen to their talk and take off our watches and so on and trample everything unnoticed.

Exhausted and resigned, we wait to see what will happen next. Finally two men in white smocks come in: a former French professor and a Polish Jew. The first speaks to us in French and the other, in Yiddish, saying the following:

“As you see, you have arrived at Auschwitz-Monowitz. You are in work-camp Buna. Here is a concentration camp from which one does not come out. Your children and wives who came with you have been taken to the gas-chamber where they have been gassed and then burned, all those sorted to the left are exterminated. You are in a work-camp, here people work hard, do not think about your women and children, detach yourselves from your private lives, do not think about the past, if you want to live.”

The same was repeated at the arrival of every new transport.

We were as though paralyzed, we looked at one another, the blood stilled in our veins. We sink from the pain: Now our dear ones are dead. So we said to one another as we stood naked in the wash-room. We came here as 1,250 souls, and in the wash-room we are only 180, they have taken 1,070 people to exterminate. Our pain is huge, to insanity.

After that sermon which announced nothing good about the new place we find ourselves in now, several barbers arrive. We all have to be shorn and shaved so that no hair is left. All 180 of us wait. We stand that way for hours until everyone is ready. Now each one is disinfected, smeared with a sharp efficiency in the delicate places, and taken to the bath. From 10 in the morning we stood on our feet and from 2 in the afternoon we stood naked, exhausted from our journey. Now we are in the bath. The place is not big enough for 180 souls. The S.S.-men push our naked bodies with their boots until everyone is crammed in. Here we wait further for water, and maybe gas will come out, who knows? We hear a weary voice call out, it's all the same, we're lost in any case.

[Page 482]

A stream of horribly hot water comes over our heads, they wet us down with the hot water and quickly drive us out onto the frosty outdoors naked. Now they lead us to a second building, where we receive clothing.

We come into a clothing warehouse. Here we receive a shirt and underpants, and in another building, trousers, a man's jacket in stripes, a cap and pair of gloves, all with stripes. We look like crazy people and do not realize it.

|

|

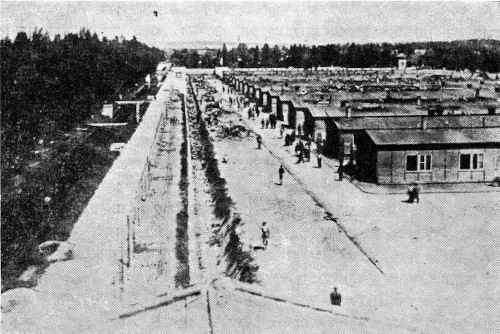

| A German concentration camp |

The camp elder, dressed in striped trousers with shiny boots, a black jacket with a green triangle (an old criminal) leads us to the buildings, bellowing “One, two three, four equal steps, you cursed mouse-faces, equal steps”. Then we are beaten over the head and the blood runs down. Exhausted, used up, we must march in military steps.

The blocks prepared for us are 30, 31, 33. I am in block 30. Here with me is Wiess, the chief of the train-wagon, with his assistants Pikart and Shtern; my friends Maurice Reznik, Shusterman with his two attorney sons (whom I knew from Paris), Shikore, Shlos (a merchant from San Anton), Maks Vint (a Jew from Vienna who came with me from Nice to Drancy) and many other French Jews whose names I do not know. When we arrived at block 30 there is a Jewish house-elder, Maxim – from Germany.

We lay deeply exhausted on sacks of straw. The house-elder Maxim announces that today we would not get any food. In the morning we would get bread and soup. Already 4 days since we left Drancy and until today we have had no food. Lying there, sleeping, it was Friday night into Shabes, the 11th of December, 1943.

Deeply weary I lie and think about the day which was so very painful. It was 4 in the morning, I hear the ringing of a clock somewhere that wakes us to get up and soon the house-elder screams: “Get up! Get up!! Make your beds! Open the windows!” His voice becomes more dog-like by the minute, and blows are delivered. “Don't you understand, bag of shit, the clock has rung. Get up and make your bed.” And he threatens that anyone who did not make his bed properly would receive ten on the ass, and indeed in the evening many received the promised strokes. The sentenced one must lay across a stool with his hindquarters up, and the block-elder and his helper choose a strapping Polack who loves to beat a “Jude”. The kapos stand around, the “house elder” (or the “house servant”) counts, and the Pollack lays on the strokes with all his might. Everyone around laughs as the victim writhes in pain. And I was one of the victims.

The clock rings again and the kapos scream: “Work commando outdoors to the roll- call”. The clock also rings for the march out. The clock tells us when to get up, when to lie down, or when someone is being hanged. Then they call all the prisoners to assemble in order to attend the execution, or for some other torment.

On Shabes we get bread and soup. We get acquainted with the rules of the camp, according to the kapos. In the evening after the roll-call we lie on the straw sacks again and consider the past day. We have not been taken to any work yet.

Sunday, the 12th of December 1943 – a rest day for the prisoners. After every 15 days of work the prisoners get one day of rest. The roll-call comes only once on that day, at 12 noon (it is usually twice a day). Everything must be in order by noon. That means: be shorn, shaved

[Page 483]

and through the lice control. From 12 to 1 is the appel; soup is given out at 3. After that the prisoners are free… to be tortured.

In the evening, returning from appel, the block-elder announces that the camp elder is coming to see that everything is in order with us, so that everything must be in a better order, he says, and everyone must be by his bed.

The hour draws near, we all stand by our beds where we sleep, everyone checks himself that everything is in order.

At the specified time the camp elder arrives. We hear a shout from the house-elder.

“Attention, caps off!” Each of us stands by his bed as if welded there, the blood in our veins freezes, we do not move from the spot and do not move any limb, we hear the heavy panting from the prisoners (200 in a block), our hearts pound.

Before us moves a colossus with wild disheveled hair, a face red with ferocity; he goes step by step and clenches his teeth. He is looking for a victim, and from time to time asks someone where their birthplace is. And he curses the “damned Jews”, the mouse-faced. “Now do you known how to keep yourselves clean? I'd like to hang you like dogs. Where did you crawl out from? None of you will ever get out of here! You are in a sanatorium now, you pigs! Mangy Frenchies! Nigger race! You wanted a war?!”

He walks slowly with a switch in his hand. A deadly silence dominates the block, except for the house-elder following him step by step.

We breath hard. Now he is on the third row, where he finds a victim, and blows rain down. Someone was not shaved. We see his brutality and look at the victim, who is now lying on the ground, blood running out, he must get back up quickly, his face is creased, blood flows from his nose; now the German is using his rod, he beats him in the face, the cries from the victim are horrible and he falls to the ground again. Now he kicks him in the belly with his boot and laughs: “You creeps, you want to beat us, damned Italian, you wanted an armistice?!” (The victim was an Italian Jew), and still cursing the Italian he leaves the building. Then we again hear a scream from the block-elder: “Achtung!” The camp-elder is gone. We breathe easier.

That's how the first visit from the camp-elder to Block 30 on Sunday December 12 looked. We receive our portion of bread and

[Page 485]

the liter or soup. Seeing the sad spectacle that took place in our block this evening we now understand the direction of the talk during our trip here, we begin to grasp what is going on. More than one us thinks about why he did not go off with his wife and children.

The bell strikes again. We run to the apel-place. All the prisoners of Monowitz stand with us – some 11,000 men. All stand and shiver, after the counting we go back inside the block. There the house-servant announces to us that tomorrow we will go to work. The full bitterness begins for us.

Monday, the 13th of December, before dawn, the clock wakes us at 3:30. Maksim, himself a Jewish prisoner, is no less brutal than his boss: “Get up!” he roars with all his savagery, “it doesn't go faster, crucifix!” And thus lets his knout out over our heads. His German doggish bellowing is no different from the cursed S.S. Plus he rampages over our tragedy.

We receive our portions of bread and margarine, and soon he chases us out of the building. It is dark outside. “In line!” he shouts. We stay in front of the block, five in a row. A kapo comes, number 63 on his armband, a prisoner like me in striped clothing with a red triangle. A political prisoner from the Lublin region (a red triangle denotes a political). He quickly counts off 40 pieces. It begins to get light outside, the kapo marches with us as if with recruits. After counting we go into work commandos. Along with the 11,000 prisoners from Monowitz we march to work across the field called Bona.

We march to the gate that leads to the camp, the kapo goes in the left side of the first row and continually shouts, “Left, left. Nose high, step left, left.” The path to the gate is lined with S.S., armed with machine guns.

When we arrive at the gate we hear “Left, left, nose high, hats off!” Here we walk like wooden figures with our hats in our right hands and do not turn our heads. The kapo announces: “Command 63, 40 prisoner pieces.” We are at the gate. A band of 12 men in striped clothing beat out a military march on musical instruments. As if to deafen.

Thus we march past all the figures in stripes up to the gate into hell. All the leaders of the camp stand here (the charge leader, the labor leader, the K. A. P. leader) and many S.S. soldiers with machine guns, all guarding the

[Page 486]

helpless, exhausted prisoners. The band of murderers continue to do their devilish work.

The road from the camp to Bona (the work place) is 4 kilometers. Every 50 paces there is a two-story observation point, where an armed S.S.-man watches the road while the prisoners march out of the camp, fenced in with electric wires. Woe to those who cannot march anymore; they are simply dragged out of the line and set on the side. A large number of them are collected every day. When all the crew have marched by from the camp, all of those who cannot march are taken to be checked out in the sick bay, for those able to work; whoever is dragged away his fate is decided. So they die every day. We march along with the other prisoners toward Buna. The roads that lead to the work place are covered with those various stripped figures. But here too we are watched by the S.S. and enclosed with electric wires that make it impossible to approach the exits of the work area.

Kapo 63 shows us our work. We dig the frozen earth. The lead worker, a Pole named Franek, shows us how we should work, and also curses the “mangy Yids”.

Our work is not easy: using pick-axes to strike the frozen earth which does not want to yield.

At 12 noon we hear a siren that tells us it is lunch time. We receive some slop – something indigestible. The first day it is disgusting, a little later we eat it with a good appetite. The 45 minutes of eating lunch is over, and we work again.

The day ends when it gets dark. We go together with all the other crews to the camp. Our workday is from sunrise to sunset – from daybreak until night – we do not know the clock time, all 40 of us go together and the kapo 63 leads his crew. When we come to the gate again, we hear the shouts from the kapo, the familiar “Left, left, nose high!” We stand like wooden figures before the death-gate. The kapo shouts “Hats off, crew 63, 40 prisoners, left, left, caps off!” and again they drag out those who cannot walk and put them on the side. Every morning, every evening, one is not sure of his life. With heart-pounding

[Page 487]

marching we enter the camp. There is the roll call, all the prisoners are now in the apell-place.

We stand for roll-call in front of block 30, the block-elder comes out and counts out his 200 with disdain. His hands move quickly, he does not spare anyone punches or a kapo one in the belly.

We stand together with all 61 blocks which are counted by the S.S. checkers. We stand in long rows in military arrangement, we hear a scream from the camp-elder: “Hats off,” and the report-taker walks among us. Everything comes out precisely. We hear the second order: “Hats on”. The music plays and we march into the blocks under the command of the block-elders. Two block-elders stand in front of the block and pull certain prisoners aside for a further check. After checking we all run to wash, and after that, according to number, each receives the liter of soup and we lie on our straw sacks. So from 4 in the morning until 9 in the evening without rest. When we finally lie on the straw sacks there is a foot check by the block elder (with a green triangle). He is assisted by two strapping Poles who are not averse to beating Jews, and they look at the feet of those lying in the bunks. Whoever's feet are not clean is hit with rubber truncheons and has to run naked and barefoot to wash his feet again. On returning he is checked again, and may have to run out again without shoes. So they entertain themselves.

We work hard. In the evening we unload cement from the trucks, we haul 50-kilo sacks of cement, we have to go 50 meters from the truck to the place to pile the cement. The kapo drives us, his intent is to exhaust us. We run with broken wooden shoes and continually fall down. The kapo goes wild, the weary exhausted crew do not have strength to walk, and he drives us to run, whoever falls with a sack of cement makes the kapo even more insane and he beats them with a stick. “You're all mangy Jews!” he screams. The Polish teacher from Lublin, the kapo in the camp – is helping to exterminate the Jews. “Do you want to make business, or not work, I will teach you how to work. You are guilty for the war, because of you we Poles are suffering. You lazy-bags, disgusting Jews!”

When it gets dark, we move back into the camp. We are among the last crews, the Polish kapo moves into the camp with us and we, exhausted, must run another 4 kilometers. One worn out man with not even the strength to walk but must run and thereby loses a wooden shoe. The mad kapo does not allow him to put on

[Page 488]

the shoe, and he has to run with one shoe in his hand on a cold December day.

So beaten down, laying on the straw sacks, more than one person thinks it would be easier to go to the electric fence than to be tortured so.

In the morning we are two fewer people, both victims are in the sick bay and hardly anyone returns from there. Today is a rest day. The clock is already 8, the bell rings for us to get up. From 8 until 12 we do the work of a rest day, and we think about the soup that we will get today, the portion of bread with margarine is not far off now.

A “blokshpere” is declared – we are forbidden to go outside. We are all closed in and could be sentenced to be burned. We do not know what “blokshpere” even means. We are all frightened and no longer think about the soup. No food would go down our throats now. We sit, depressed. The doors and the windows are guarded by the kapos. The block-elder orders us to undress and line up number-wise, all very quickly. We are as if paralyzed. Our hearts pound nervously and soon our young lives will be extinguished. 200 men stand naked with hearts pounding and wait to go through the Angel of Death. Who knows who will be sent to the ovens, who of us standing here will not be alive tomorrow? Our naked bodies are withered. We hear a bellow: “Achtung!” The devil, a tall man in glasses and a fur coat. His two assistants, one an S.S., the second the sick bay elder from Monowitz. The three of them send hundreds of prisoners to the crematoria every day. 200 starving bodies, frozen in torment, spread out for the S.S. officer and the sick bay “doctor”. Whoever will be killed tomorrow will have his card taken today. The block-elder, who holds the cards in his hand, give it to the S.S. man, the S.S. man gives it to the sick bay elder, that is the procedure. In 45 minutes 34 lives sentenced to destruction. We hear another “Achtung!”. The devil and his two helpers are gone.

We are in the building, and see the dawning day with its whole horror. The sentenced know that in the morning they will be killed. We all choke on tears, looking at them. The Yugoslavian man from my crew says goodbye to me, his name is Doytsher,

[Page 489]

brought here from Italy in 1943. The other, who sleeps in the same bunk as I, Konstantin, a judge from Italy, is also sentenced to die in the morning. He weeps.

From my crew 63 are leaving, 6 to the crematoria.

Again a day like all the other days. We stand and work at filled lorries and we stuff the lorries instead of machines, the work is hard. I work with the shovel. The naked selection gives me no rest.

The kapo speaks to us about the naked selection as a thing that is natural. Those who cannot work are not to be fed, especially Jews. He says that yesterday 6 of our crew were taken, tomorrow there may be another 10. This does not bother him, he serves the S.S. loyally and is a convinced antisemite; he justifies the Hitler murderers who exterminate the Jews. He brags about his madness, he has already sent many Greeks and French to the ovens. At the end of the day he tells us his standard curse words: “You disgusting zshides will all go in the crematoria; none of you will get out of here alive”. So speaks Mietek, the kapo of crew 63, the former Polish teacher.

Each day the bell rings again to get up and again the day to day meanness. Outdoors it is frightfully cold, the winds rip things to pieces. The work that we do is always the same. We are freezing and starving, exhausted and tormented all day from 4 in the morning until 9 in the evening, and chased. We have been turned into walking figures of wood who do every thing without understanding, without feeling, and every day is the same.

In the evening we come to the roll-call by the thousands, blackened from loading coal or cement; people with no light in their eyes, bent over from the cold: people with swollen fingers, black as if covered in rubber, fat lips and dark rings under the eyes, uglified and broken, from everyone comes one great moan: when will this ever be over.

Rather than in the evening, today we march into the camp at 2:00. It is news for us when we come to the roll-call place that something is happening. We, the green ones in the camp, are shocked. We take our places – 11,000 of us. We stand after the roll call-with

[Page 490]

our heads bared and look in the direction where the S.S.-men are. Soldiers arrive, machine-guns in hand and helmets on their heads.

The thundering voices of the camp-elders rip through: “Hats off!”. We stand as though painted and do not move at all, our glances are strained in the direction of the S.S. Soon someone reads a death-verdict: Sentenced to death by hanging for attempting to escape from the concentration camp. We hear the judgement and strain our eyes to see the gallows standing near block 4. Someone in stripped clothing stands under the gallows with his hands tied behind him, and a second prisoner, also in stripped clothing, puts the noose onto the sentenced one. We hear the slam of the deck that the sentenced is standing on and the hanged one struggles for just a few seconds…. The 11,000 must all march past and see the hanged man. Which now looks like broken tree limb hanging down.

A few from our block are in the sick bay. And now I am sick. Knowing what happens here I think about my lot, because everyone who goes into the sick bay are candidates for Auschwitz. Thus days and days go by and I struggle with myself, not wanting to go to sick bay, my fever rises and I am on fire, the hard work knocks me out. In the evening when we came from work I run to the sick bay – I cannot hold out any longer. When an aide takes my temperature it is 38.4. He says it is not enough to be put in the hospital – one must have no less than 39.5. When I dispute this, they hit me and throw me out. In the morning I must go to work again. I drag myself after my crew and collapse at work, the kapo is not happy. He wants to send me directly to the crematoria. I lie near the shed where they store the work tools. I do not eat the mid-day soup.

At the roll-call they take me back to the sick bay. The doctor tells me to lie on the ground, where others are lying in a row waiting. Every evening they bring in frozen, wasted and beaten workers. The room is too small contain all who seek help. The thermometer-reader goes from one to the other, and I have 40.1. “Young man,” he says, “tomorrow you will be in heaven.”

I understand that I am done for. Today is already the

[Page 491]

72nd day since I came to this hell. The kapo explains nothing of what he is doing. He brags that every three months he sends 40 or 50 prisoners to the crematoria.

I am fully conscious of that, and now I am staying in the hospital, from which few people return. Each day there are many deaths, the “Muselmen” (those who submit) that are brought here, and do not last long.

|

|

| The kapos load the dead to be burned in crematoria |

I see my home, my 4 brothers and 2 sisters, my old parents, my large family. I wonder which of them is suffering still; I think of my brother who was taken from Paris on 16th July 1942, who of my nearest are still alive?

Now is my turn, my pain is terrible when I think of my dear little son, he is not even 4 years old, will he know how his father died? Or is he also among those the brown murderers have dragged to Auschwitz?

Kurt, the patient-tender in the hospital, interrupts my talking to myself. I look at him with wild, burning eyes. I say to him, “My

[Page 492]

little son is only 4 years old and now he will be an orphan.” The orderly listens to my words and wraps me in in a wet smock.

When I woke it was daylight outdoors, I saw a big snowdrift through the window and I covered my head, not to see the empty life of my fellows who march in the deep snow to their forced slave labor. I remind myself of my crew with a shudder. How many tortured or frozen men will they bring in from work today.

Today is the first day since I have been in the hospital. I am fine in a dirty bed that stinks of the pus of the last one who died here. I am warm, now 74 days without sleeping, of getting up at 4 in the morning and standing on my feet until 9 at night.

It is just a little into the day and I am still in bed. I burn with fever. My neighbor, a Czech prisoner lies near me and continually spits out the remainder of his lungs. He is near the end and gives me his black coffee. I do not get any food either, just a little black coffee.

My other neighbor tells me that a selection took place in the hospital two days ago. They took out 100 people to truck to the crematoria, those who did not want to be taken were dragged out by force. Later their coats were brought back.

It is now the second day I have been in the hospital. The doctor, a Jew, considers me from all sides and finds an infection in my left side; he calms me saying that I do not have any water and tells me that he will make an effort to save me. He does not have any medicines, the S.S. provides only death.

Coming back to bed I see that my neighbor, the Czech, is covered over. He spent the night with us. I cannot fall asleep. The little night-light sends fear into me. I think about death. The orderly Kurt wraps me again in a wet blanket, and tells me that I will get better. My new neighbor also ends it and breaths out his soul. For 5 days he has hidden his whole ration of bread in a bag under his head, not knowing that he will never eat that bread, his nose is a white as chalk. Before it gets dark, he is already dead. The found bread is divided among those who can

[Page 493]

eat. The hunger is huge and one does not think about where the food comes from.

Every morning and evening they bring in broken, swollen prisoners, and all day they carry out the dead. My third neighbor, a Jew from Lodz, is also dead now. He went to sleep without a moan. It goes like that constantly.

Seeing what is going on here, I want to go back to the work crew soon. The doctor says that I am doing much better. The 23rd day in the sick-bay I am designated, along with another in the same room, to serve the sick. For this we receive an additional soup.

Shabes the 1st of April 1944 I leave the stinking sick-bay, where I have lain for 28 days.

I come back to block 30, where I had slept. The block elder (a green triangle: criminal) looks at me with disgust. The roll-call comes around. When we come back he asks me what crew I want to be in; when I say 63, he coughs. “A good crew.”

When we came back from roll call I am placed as before with crew 63. The kapo looks at me with irony; seeing me alive is probably not his wish, I am superfluous to him. He has fresh victims. Of the 40 people that were with me there remain only the one who shines his shoes and his three servants. All the others from before are no more. As I understand it they all became “submissive” and were taken in a selection.

The kapo of crew 63 is a well-known antisemite. And he incites all the other to beat the Jews; also kapo 178, who is himself a practiced beater. (Kapo 63 is called Mietik, a former teacher from the Lublin area, in 1944 he was in camp Monowitz.).

Coming back from work we see another three gallows set up near Block 4, where the camp-elder lives. Everyone marches into the roll-call area. The S.S. come in fully armed.

The voice of the camp-elder rips out: “Rest! Hats off!” All the small and mighty of the camp stand opposite us. The procession is in full process.

A prisoner from the writers' house reads the judgement: Sentenced to death by hanging for stealing food in the time of an air-raid alarm. So with all three judgements. We, 11,000 in striped clothing, with uncovered

[Page 494]

heads, hold our breath to hear the last words of the death sentences.

The martyrs say something but because of the distance I cannot understand it. Again we march past the hanged men, whose corpses are rocking in the wind. For them everything has ended. They had suffered so much, years of torment and hunger, cold, and now in 1944 when the Nazis are beginning fighting the death knell and their dark end is approaching, they see death. The month of May is coming, the air attacks are more often, and we have no right to hold out. When the bombs fall we must remain on the ground. Bona is huge, a whole town with factories that was built by the slaves brought here. Jews, Russians, French, Belgians, Italians, Poles, Yugoslavs, Greek, Turks work here – people from all over Europe.

If not in the crematoria we die from being slammed around, our nerves are shredded . When the operations ended we were able to further see how everything is shattered. After the recent attack we collected the bodies, among them our fellows, there are 225 dead and 430 wounded. And so it continues.

As we march into the camp from work the sick-bay drives back. The doctors do their work – taking in the wounded, and sending the dead to the crematoria.

I find myself in a much lighter work-crew, in transport. The kapo is a German Jew from Berlin; Hitler burned his wife and child in Auschwitz in July 1944. He does not swear or fight. We sort pipes, rolling them from morning to night, gathering those destroyed by the bombings. We do the work with great pleasure, knowing that it all goes to an end. Thus we live with hope to perhaps survive.

Among the last transports brought to Auschwitz in July 1944 were the Hungarian Jews (and some from Carpathia), they had been settled in the villages and in little towns for generations, the majority of them craftsmen; one related that someone said to him that everyone was being taken to a camp to work. “So, I thought it was to work as I was used to working, and that would not be so bad.” He was the father of 8 children, the whole family was taken, among them 2

[Page 495]

daughters who had survived by living with non-Jews. He had done that in order to keep the whole family together…

The work in the fields was hard and bitter. In the summer months we stood in the water all day with the sun overhead, burned by the heat and thirst, smeared with mud and cement, with swollen and blistered feet from the wooden shoes. In winter rain and snow or frost we get up at 4 in the morning and stand at our difficult work in the field until 7 at night, always threatened by death in a selection for cremation or another method.

Now I am in Block 34. The block-elder is a converted Jew from Germany. He had deep hatred for the Eastern European Jews and beats us as if to kill. He himself doles out the soup and pours with the intent to humiliate. And woe to anyone who falls into his bloody hands. We are already lying in our bunks. My current neighbor is a Belgian Jew, born in Poland. He now comes from the camp trading post – that is what we call the latrine – the exchange for the prisoners. There one can sell his shirt or his shoes for a piece of bread or a little soup. He comes from there with the horrifying news that there will be a selection in a few days.

|

|

| A group of “prisoners” at work |

The Hungarian Jews, who came in the last transports in 1944, sleep as many as a thousand people in a space that can hold 200. The people are insane from crowding, it takes hours to get a piece of bread or the soup. The conditions there are hard to bear. When they came from work they recite the afternoon prayers

[Page 496]

and evening prayers before going inside the building, not comprehending where they are.. A large number of them, the very religious, do not eat the soup for reasons of kashrus, they live on the portion of bread and sell their soup for cigarettes or something else. They quickly become “submissives”.

September 1944. It is erev Rosh-ha'shone. Jews plead with the block-elders for permission to pray together on Rosh-ha'shone after their work in the block. Vetsl, the converted Jew, is the block-elder in Block 34, but – he permits it. Rosh-ha'shone night, coming from work, we wash and each one takes his portion of soup. In the block we can feel the fear of God from the religious Jews. A prayer leader prays aloud, and all the Jews pray with him. The weeping and the pleading to God that he may release us from this gehenem permeates our bodies. People weep for the destruction of Auschwitz.

In the morning we go off again to our hard labor. Jews talk about the upcoming Day of Judgement, it is erev yon-kiper. When we come to the block after work, the block-elder announces that this night is a block shut-down. Door and windows will be guarded by the kapos. The black-elder and the servants are happy to be free of the “bags of shit” (so they call us). They bare their teeth. One's heart shrinks at such a moment, we can not move and must stand like oxen in a slaughterhouse.

The sentenced know that tomorrow they will not be alive, their nerves are weakened, all are enveloped in the morning smoke that will draw from the crematoria toward the clouded sky. The kapos and the block-elder are now closed into their “day room” where they eat and drink.

At 3 instead of 4 in the morning today, the block-elder and his helpers fly among the bunks of he sentenced and take away

[Page 497]

their clothing, and drag the sentenced into their room until all the others go out to work. Afterwards they take them with all the others sentenced and drive them to the gallows, that stand in the middle of the place in the middle of Camp Monowitz. This time 500 people from Monowitz are sentenced to die. At 11 in the morning vehicles come, to take them to the gas chambers and ovens.

Again we stand between day and night on the roll-call area opposite the gallows, where a new three sentenced stand on the decks. At putting the noose around his neck one of the sentenced shouts out: “Friends, hold your heads high! We are the last victims, may Free…” he did not manage to finish his speech.

The year 1944 will soon come to an end, we know that in Germany the surviving Jews are free.

In the large latrines with 16 seats on each side sit 32 people in striped clothes, trousers dropped and roaring out the Marseilles in French.

Once we are in the block we hear sirens, and cracks from airplanes. Bombs are falling someplace, and we in the dark block are drawn from our straw-beds. Some are calling out “Shema Yisroel”. We are closed in an electrified state, not able to get ourselves out of here. The window panes rattle, the buildings shake, everything leaps into the air. From a distance we see red fires flaming toward the sky, not far away a camp is burning. We lie in our places and are forbidden to hide, only wait to die.

It is the end of 1944. Because of their holiday we have 2 days of rest. In the evening, right after the soup, each one of us lies on his straw sack. In Block 34 where I am there are many Greek Jews. One lies on the third level and bemoans with great pain: “My wife and my two children are burned, my home is destroyed”, and tears stand in everyone's eyes. In is quiet, the block-elder does not disrupt us. One does not want to live any more, in camp every days becomes worse, our food less. When we come from work the next day there is no light and no water. Everything is smashed.

The block-elder and the kapos become wilder. The beat us mercilessly and continually remind us that we will not get out of here alive.

January 1945, we are freezing. Getting up at 4 in the morning is terrible.

[Page 498]

On the fields of Upper Silesia the winds bite and we gather together from the cold.

When we come from work on January 15 the block-elder announces that we will evacuate this place.

There is tumult. We do not get any more soup, just a couple of potatoes with skins on. Each takes his potatoes in his hat. Each does what he wants: When the clock rings at dawn everyone gets on his feet as every day to march to work. We wait inside. It is 5, 6, 8 o'clock, they don't take us to work; the clock sounds again in the afternoon and everyone runs out to the roll-call area. We march out to the work place Bona. At the gate we do not see any military leaders, no masters. S.S.-men with machine-guns stand there, the big ones are gone. There is no noise coming from Bona, everything stands still. The gas-works and the power-works are not in operation. Each kapo leads his crew where he wants, no one does anything.

Later we go back to the camp, the block-elder is not beating us anymore. He lies locked in his “day room”; we are naked without shoes, without food.

In the evening the block-elder announces that we might still march out today. We tear up the straw sacks and everyone makes a carrying sack. In the morning we stand in the frost on the roll-call area, wearing our sacks over our shoulders, and wait.

At 12 o'clock we go back to the blocks, after getting our soup. We stand again and wait. The sick who cannot even stand go down a hard path.

So it goes the whole afternoon. Before dark the atrocious clock rings again. It is the 18th of January 1945. All 11,000 prisoners stand arranged by 100 in a ow. The roll-call place has a particular appearance: all the kapos and block-elders stand with us, only the Tiger (the camp-elder) walks in front. Complete quiet reigns. An announcement: “March!” We walk in a long row. I look before me and behind me; my eyes cannot see where this long train ends.

We go to 5 abreast along the snowy roads. In the distance there is a truck from the Red Cross, but not for us. We are guarded on every side by S.S. with machine-guns. We walk past

[Page 499]

a village. The wooden shoes are full of snow and we walk as if on stilts. We see that civilians evacuate on hand-carts. The panic among those fleeing is great. We drag ourselves dead tired on the road for hours and cannot walk any more. In a second village at night the church clock strikes two.

We march with all our strength. Anyone who cannot march any more is shot. The night is horrible, the shooting does not stop. We do not know where we are being led, we continue along side roads, not on the highway. This makes the marching harder. Already there are hills of the shot, and they drag us further on. Outdoors it begins to get light.

A little into the day we came to a brick factory. We have been dragged for 15 hours without rest, hundreds of us remain on the snow-covered fields, we are all weary, exhausted.

Outdoors is just empty cold. It is the 19th of January 1945.

We are in the town of Nikolayev, the whole town is occupied by S.S. who are retreating from the front, there is no place for us, we are all stuffed into the courtyard of a brick factory deeply covered with snow. We lie down anyplace. An attic, a hole, any place to rest. But people are lying everywhere, they lie on top of the snow. People are sitting on every brick, half-frozen, many are asleep due to the cold, there is already a pile of stiff people.

They cannot move and are thrown onto a heap of the dead. The others take their rags off them and cover themselves, the corpses lie naked, their bodies are black with stiff legs. The cold stings. Lying stuck in a hole I meet a fellow townsman from my home Sokolov. I only remember his first name – Yosl. Then we lose each other right away.

The clock strikes three and soon we hear the whistle “Stand up and march!” We arrange ourselves in fives, now there are no kapos, the S.S. who lead us are completely insane, they run around with revolvers in their hands, anyone who moves from the spot is promptly shot.

Now we must march 24 kilometers to Camp Gleyvits II.

When we come to Gleyvits we stand to a long time until we are let inside.

This is not a large camp and is already full of

[Page 500]

transports that have come before us. The horrible hell Gleyvits can contain only 2,000 prisoners and there are already a couple thousand from Auschwitz, Birkenau and others. Everyone came before we did. The barracks, the writing room, the ammunition dump, the latrine – are all clogged, not place to lie down. People are hanging on the walls, everything is packed, all hell has broken loose. The cold is killing us, we collapse from tiredness and lay all together in the snow. Let it be for eternity, as long as I can lie down.

Another transport arrives with people in striped clothing from Auschwitz: among them a lot of German citizens, former criminals. There is no place for them either, they throw themselves on us weaker ones. We drive them away from our “warmed snow”, where we lie and freeze and receive blows from the S.S. They want us to give up our places. Outdoors it gets light and I meet my Monowitz neighbor from Lodz who I lost at our arrival in Gleyvits II. We stand together. The sun comes out from the fog, we hear a wild whistling, that is to say entry to roll-call. Everyone from the block stands, a queue of human heads on the roll-call plaza. The block leaders stand on the rooves of the buildings, armed with sticks. Standing here I meet my Sokolov landsman, Yankl Kviatek. We are happy to see one another among the living. He tells me who from our neighborhood has not survived. The S.S. whistle and scream again: everyone from Auschwitz and Birkenau “March”. The S.S. selection commission checks: anyone who is already exhausted and cannot march any further is promptly shot. Behind us, near the block there is a mountain of those shot.

Those from Monowitz remain longer, we are taken into a barrack that is free now. Soon we hear mad shouting and shooting. They stand us again in fives ready for the road. It is the 21st of January, 1945.

We go through another death commission that happens after 30 hours of hunger. Who will get a 300-gram piece of bread and 25 grams of wurst, and who will get shot behind the barrack. In a long row of 5 we come to the train line not far from the camp, and stand for 5 hours. A transport arrives at 10 at night, open cars without rooves. The S.S. order: “Quickly into the cars! Faster! Faster!” If we do not go fast enough, shoots fly over our heads. Everyone throws themselves into the cars. Soon there is no more room, nerves are frayed.

[Page 501]

It becomes suffocating. Into a car for 40, 180 to 220 people are stuffed in. It was a structure of three levels: the first to get into the car remain underneath, the second layer lays on the first and the third layer, on the second. The highest level is freezing and the lowest level is suffocating.

Already 2 days that we have sat in the cars without food. We nourish ourselves with snow, that falls from heaven into the cars. We do our natural functions where we stand. By day the train stands by the fields, and by night it drags us unseen through the towns. We travel through Bresliv (Wrotslow). Everything there is closed and dark, the train does not stop at the train station, only at the fields.

It is the third day that we sit freezing in our cages without food, without water. To the question about freeing us from the dead, comes the answer, “You will be dead yourselves, the dead remain here until you arrive at the place.” On the 4th day we arrive in a town and stop. We realize that we are in Thereisenstadt.

We stay here long enough that the S.S. and also the doctors from Monowitz travel around the cars. After four days of travel we stand up for the first time and see that people are carrying bread for the prisoners. The doctors run around the each car and ask how many living there are in each car. A few of the stronger ones who count the living and the dead, and report. In our car there are 75 living and maybe as many dead. They lay the dead to one side and the living move to another side. They lay the dead one atop the other in order occupy less space.

An S.S. ask if everyone has received bread. The S.S. calls out the three distributers, confronts them in the car and finds their portions and two whole loaves of bread. He asks again “Has everyone received bread?” Then he counts the living himself and finds fewer living than was reported. He takes the bread-distributors out and murders them.

We travel on. The train drags on the whole night, we sit again in the places full of filth from the 4 days. We are on Czech territory. Our train stops at a station opposite the civilian trains. The civilians see our striped clothing and comprehend who we are. They look at us with pity. A few toss us packages of food, which are quickly snatched up.

[Page 502]

It begins to get dark and we travel further on. Again we hear shooting, and again several prisoners are buried by the light of the moon. When it gets light we can see the towns and villages. We come to a train line and realize that we are in Weimar and not far off – the infamous camp Buchenwald. One half of the train remains behind and we travel on up on a hill. We see barracks fenced in with electric wire and ride into a decimated forest, which frightens us. The trees on both sides make the gloomy skies even darker. Buchenwald really is located in the center of a forest.

Our train stops and the crazy bellowing begins again: “Get up and clear the cars, faster! Faster! Out, out!”

We climb out of the train and fall down, our legs do not function after lying in one place for six days and nights. The S.S. get wilder and beat us over the head, we get up and clean out the cars. We push aside the people who collapse. The dead lie frozen with their bones broken, black with yellow spots.

There are also tens of thousands who have arrived before us. The “camp security” in green coats deals with us, they beat us without mercy. We, a group of Parisians, stand together: Misha Reznik, Bakivietski, Marcel from Orden, Shpiglman and Ayzenberg from Belgium and my friend Salomon.

In the plaza opposite the baths lies a mountain of fur coats, Astrakan curly lamb, mink, the best fur goods, and other valuable items brought in from victims all over Europe.

Our group stays together. People become insane and mad from despair, one stands on another, people lie shatterd, the queues of people writhe with the cold, tens of thousands arrive in waves.

Late in the evening the “camp security” comes and arranges us again in fives, and directs us to a block, we are in the old camp, Block 57. The inquisition place has two camps: one old and one new, the latter built of bricks with several stories, and the old camp is of wood as in Auschwitz or Monowitz.

Our group is 1,000 souls. We are let into the barrack. The mad scurry to find a place begins again

[Page 503]

There are bunks on three levels here, but not enough for a thousand people. In one bunk for 5 people must lie 24.

It becomes quiet, we lie wrapped in our clothes, the block-elder comes in, a tall German with many wrinkles on his face. (As I later realized, he was a political prisoner, already in Buchenwald for 10 years.). He walks through the block with assistants, a Frenchman and a Russian. The block-elder orders us to stand group-wise in order to receive our soup. That news is enough to get all one thousand men on their feet and push towards the barrels of soup. The assistants shout in every language for people not to push, that there is soup for everyone, but that does not help. The assistants are not strong enough to hold back the frozen, starving men who have gone 8 days with nothing warm to eat.

The block-elder appeals again to keep calm, but everyone stands against him with eyes bulging out and looks at the barrels from which steam is rising. They begin again to dish out soup and the shoving stops.

The block-elder tells them to take the soup into his room. At night we wake up in groups and it is doled out the whole night.

When the block-elder counts us in the morning and finds fewer than one thousand men, the assistants search the block and pull out from the corners and holes the dead, beaten, exhausted, depressed. The dead are dragged behind the building by their feet and their faces are sprinkled with lime. When the number agrees each of us receives a piece of bread, wurst and a liter of soup for 24 hours. And on the bunks there is hardly any relief from crowding.

In the early morning we hear the whistle: “Come out for roll-call!” Prisoners drag large wooden wagons full of dying people in striped clothing, we are taking them to the crematoria. I see familiar faces among them. The sick get an injection and are soon dead. “In Buchenwald,” says a kapo with a dull face, “we don't play around, there are too many sick.”

The first ordinance: Get rid of the rags that we are wearing. We are happy to throw them off ourselves, and we are led naked into another room. Here stand two S.S. officers. They look us over, tell us to open our mouths (probably looking for gold teeth), and tell us to turn around with our shoulders facing them, tell us fold ourselves in two, each one after another so that they can check us. When everyone is

[Page 504]

suitably checked we are let into a large hall to be shorn and shaved with electric machines, all parts of the body. Then we go to a separate hall where each of us must go and dip himself into a vat of a biting liquid. Then they take us to wash ourselves.

The warm water envelopes the emaciated bodies that have grown together for so long in heaps. Then they take us to a clothing warehouse. Each of us receives a shirt, trousers, a jacket, a cap and a pair of wooden shoes; these are all old civilian clothes with a red stripe on the shoulders.

Coming back to Block 57 we receive our portions for the day: a piece of bread and a liter of soup which is immediately swallowed, and again up to the sleeping bunks on the crowded third level to be suffocated. Each day they drag the “late-sleepers” from the bunks and after roll-call the bodies are loaded onto carts pulled by prisoners. People say that there are 60,000 prisoners in Buchenwald.

We stay with old Buchenwald prisoners who already know the rules of standing for 10 hours in the cold or under a burning sun. Some tell us horrible things that they have been through in the early days, when Buchenwald was built: about licking the floor with the tongue, crawling on the belly from one wall to another, or standing from 11 in the morning on a summer day at the roll-call area under the broiling sun until the next day at 11 in the morning. More than half of them died. They were shot for any tiny infraction, people went mad from the hardships.

We are registered once again: name, birthplace and we get a number. My number is 124000 of Buchenwald, the number from Auschwitz is not considered here, and afterwards everyone gets an injection. On the seventeenth day we go over to the second camp, where we go through a commission for sending us to work in a factory. After such a horrible evacuation we do not know which of us will remain alive. Friends decide therefore to give each other the necessary last will in case one of us falls. After the selection, we are taken to a movie hall with wooden benches set out. Here sits everyone who will be shipped on a transport. Until 4 in the morning they continue to fill the hall with a couple thousand people. Afterwards we go to the roll-call area for counting. Outdoors it is still dark and the searchlight illuminates the huge roll-call area of Buchenwald.

[Page 505]

We stand in long military formations of 100. They say they are shipping out 10 thousand prisoners for work.

We march under the accompaniment of S.S.-men armed with machine guns, along snowy by-ways among trees to a railroad line. We ae counted into 60s. We site on the ground and receive bread and white cheese.

Along the way our train is shot at by planes. We are inside and a wild clatter is going on over our heads, the S.S. who stand by the doors fall dead, their heads split open. They fall on us, blood pours out from their split bodies, we lie in one big pile, the planes above us. We jump out and run over the surrounding fields. The planes fire a burst from their machine guns. We throw ourselves to the ground. The planes circle around a few times and fly off leaving ruptured bodies, also of some prisoners.

We think there is no point to running away, not far from Buchenwald, surrounded by S.S. who can loose their death tools on us and we return to the train. The planes have caused devastation, the train is smattered, many dead lie around and we gather the dead and wounded. The Red Cross comes with doctors and gives help only to the wounded S.S. Prisoners lie there with bellies ripped open, with arms and legs torn off, Dr. Makovski from the sick-bay in Monowitz is with us. He runs to each wounded and does what he can. He cannot help the mortally wounded. He only has a few paper bandages. So we gather the dead prisoners on one side and the dead S.S. – on another. Only the wounded S.S. are taken to a hospital. The women who came with the Red Cross give out water for everyone and collect the broken body parts in the field.

Finally we arrive at the train station in Halberstadt, 50 miles from Buchenwald and 150 from Magdebourg.

In the clean city of Halberstadt we march past businesses where one can get everything. Everyone does his daily work. Civilians stand and stare at us. We still march under the impression of death. Again we arrive in a decimated forest.

Camp Halberstadt. Like the other camps, it is also enclosed in electric wires, and located in a valley between two mountains.

[Page 506]

Coming into the camp we see three people in striped clothing bound to electrical poles with their hands tied behind them.

We stand in a long line. The camp leader comes and sternly orders that we divide into Jews, Russians, French.

Then we stand as three groups. He asks who can translate to French and who to Russian. Translators step up. The camp leader tell us that here in the camp things are very strict. If anyone here steals, runs away or does not follow the orders, he is given over to the “Gestapo” and hanged. Here are three Russians who stole potatoes from the kitchen; they must stand until the crews come from their work, that is from 7 in the morning until 7 in the evening. The translator relates everything in the various languages – that is, for taking potatoes three people are tied to the electric poles for 12 hours on a winter day. It is the 19th of February 1945 in Camp Halberstadt.

After listening to the elder's speech and the translations, they let us in to a large hall, which the non-Jews leave. So we stand for 6 hours and are not permitted to move from the spot.

We receive black coffee and then a registrar asked each one his name, trade and origins. Before night we are led to Block 14, located in a valley. Everything here is wet and filthy. No beds, no straw-sacks, no roof, no light, no water.

For three days we lie on the sticky earth. The food her is much worse than in the other camps. One bread for 6 people, a little disgusting soup. Now many days without washing, each day they take us from the hill down to the roll-call, which is located not far from the gate to the camp. On the 6th day when we stand at the roll-call and everything is ready, there comes an order to remain standing. The night shift goes off to work, the second crew for the day shift comes back from work, and we remain standing. A commission comes for us, the “Herman Goering Project” which is work in a tunnel, the “Wafen 2”. The commission – a group of civilian Germans with batons in their hands and leather caps – walks through our long rows and looks each one in the face. We wait to see if they will buy us. Afterward we go back to the cemetery block. The filth eats at our bodies and

[Page 507]

we continually get sick. We lie there for whole days and do our dirty work of trying to get the lice off ourselves.

On the 8th day it is announced that we will go to work. They assemble a 310 crew of 50 numbers (50 men). Our leader is a prisoner who has already been in the camp 4 years. His assignment is to deliver us to work.

We go into the “Herman Goering” tunnel for the first time. Our group is escorted by the S.S. who are not of the “pure race”. He shouts “Walk faster!” in a foreign accent.

Along the way members of the “pure race” with rubber truncheons beat us continually as the crew goes to the tunnel to work. We run like crazy people and break our feet on the various materials that lie about on the roads. Finally we come to the tunnel, which is not wide and does not have enough light. One party comes out and a second goes inside. Two rail-lines run through the middle, which carry out the broken-out stones in little rail cars. The S.S. who check on everything stand on the sides of the tunnel like dog-beaters with sticks and hit us over the head, so that we will work in double-step. We run among the machines that go in both directions and are deafened by the noise and the screaming of the S.S. People are squeezed between the fast-moving machines. The crushed people are taken out on the cars with the stones.

We arrive at our workplace “Herman Goering”. The master assigns the work. Our overseer, who brought us here, has nothing to say. The master divides us into various groups to a second master. The second, who directs us, is also a Germans from Hamburg with an angry face without teeth. He speaks to us with a Hamburg accent and we do not understand a word. Our work must be: breaking up the stone walls and loading the stones onto the carts. We chop at the walls with pickaxes.

The work-shift in the tunnel is 12 hours. The work goes on in 2 shifts, day and night.

Each morning we are wakened not by a bell but by a wild German with a truncheon in his huge hand. His hateful water-eyes make him look like a hangman. We get to our feet quickly and run to the roll-call area. Here in Camp Halbershtadt there is one large latrine for all the prisoners and one water faucet, far from the barracks. Everyone is dirty and full of lice. In the evening

[Page 508]

when we come back to the camp we get the disgusting soup.

After 15 days on the day shift we are changed to the night shift. The night shift is much worse – we do not have day and we do not have night. Returning in the morning from night work takes a long time until we can lie back on our lice-infested straw sacks. They wake us at 1 o'clock to prepare for the night shift work. Before marching to work we receive the daily food at 2 o'clock. There are a limited number of plates circulating in the camp, that remain in the hands of the strong-men, mostly non-Jews. We must wait one after another for our turn to get the little bit of disgusting cold soup.

Those who get the soup go in a large hall that holds about 2,000 people, and take a place on the filthy straw. Many non-Jews sit there, who work with us: French, Russians, Yougoslavs, Poles, Latvians. After the soup distribution no one is let out. Each one stays with his group of the same nation.

The Russians are largest group. Five nations are mixed up here, that do not live in peace with one another. Some, the majority of them Slavic peoples, have specialized in various ways to steal another's bit of bread. It is done in this way: You are holding your portion of bread in one hand and the soup in the other hand, one of them grabs your cap, the second grabs your bread, the third your bowl of soup, then they run away.

The old – perhaps 70 year-old – master never stops threatening us that he would kill all the filthy Jews with his truncheon. He struck with a particular sadism. So the days stitch together. Assigned to the crew where I worked was a lame S.S.-man who came from the front after being wounded 7 times, with one arm and one stiff leg and a rubber truncheon. Woe to anyone who fell into his hands. He took one prisoner and told him to prostrate himself and count out 25 strokes. And he often comes into the tunnel and takes revenge for his unfortunate end from his experiences at the front.

The people fall exhausted from the work, from too little food and the terrible conditions. The death rate is very high. The camp numbers 4,500 confinees, and each week there are piles of dead. There are no crematoria here, and the dead lie until the Sabbath when burying the dead takes all night. Life is even worse than

[Page 509]

in the previous camps where I have been. The room with the dead is located among the barracks where we are, and is filled with a horrible smell.

Each morning the block-elder comes, an obtuse German criminal with his helper who is already long years in the camps. He wakes us with his gnarled cane, and if that is not as fast as he wants he sicks his police-dog on us. That is how we are driven each morning out to the roll-call area, and the dog rips out pieces of our dried-out flesh.

|

|

| Clearing away those who perished |

Every Sabbath the order comes from the roll-call: “Jews remain standing!” Then we carry out the dead that lie in the crates, the withered arms slide off of the dead, they hang down like two whip-handles over our shoulders. We come to the huge common grave, today the prisoner standing there to direct the work wants to imitate a true S.S.-man and constantly screams, “Fling them in!”

At the beginning of the month of April 1945 when we come from work into the camp, we encounter a new situation. What is happening here makes us very uneasy. The 4,500 prisoners here are arranged in lone rows on the roll-call field. Each of us states his conjecture, no one knows for sure. We think it is another evacuation. The night drags on in noise and disorder. We curl up tighter together in our bunks. In the morning we do not go to work.

[Page 510]

After the roll-call we are not driven back to our blocks, the April sun warms us a little and we lie out in the plaza and peel off the skin from our bodies, so broken out from the filth.

The camp leader and the S.S.-men order us to assemble; the S.S. search for hidden weapons in the barracks. On the third day we are called to roll-call, as we are going into transport.

On the evening of 8th April 1945 we are assembled into separate language groups: French and Belgians together, Russians and Poles, and Jews separately. We are 500 Jews from France, Poland and Holland. Our group is the smallest, the majority are Russians. Our march out takes place as in Monowitz.

As then, we are accompanied now by the Hitler hordes, armed from head to foot, and the leader with the death-head also goes with us. The S.S. leaders drive us on with their doggish voices. We are in the train car, among sowed fields. Military units are pulling us. The fields are already greening up. The S.S. lead each group in a second direction, in the dark along back roads. Indeed we see their failure: The military runs in both directions here and back in mad chaos.

Somewhere airplanes are operating, we hear the bursting of the bombs; rockets fly skyward and illuminate us. We see the second group, marching on another side, there comes an order to lie down in the fields. Most of us are walking at night. In our group there are only Jews, we meet civilians with hand-carts full of children, the women push the carts, we do not see any men.

At dawn we arrive at a church where we sit out like beggars, weary from the third day of slogging, embittered and starving.

The night goes by under the bullets of machine-guns. Everyone wants to cling to life. However weary and depressed we are no one wants to breath their last by bullets. One holds on to another and drags along. Now our ranks are thinned out. I am among the last, walking in the back rows to be shot. I see my end now. My friend Resnik is near me and encourages and drags me with all his strength.

The Hitler Army runs back in disarray. We come up against a group of hurrying soldiers. “Where are you taking this shit to throw it away?” We go further toward the field where the leader tells us to lie out, and we receive

[Page 511]

250 grams of bread each. Everyone is lying down and cannot go further, everyone has swollen feet, it is now the 5th day, even if I get shot. The torn wooden shoes are useless; our feet are rubbed raw, why march further? I am certain that I will not be able to walk any more and that death is right under my nose.

I think of running away if we come to a dark forest, since many have done that. I do not know how that ended for them. Those who fell into the hands of the Gestapo while fleeing were certainly shot. There are tens of shot people lying along the roads.

I firmly decide that my walking further has no purpose: Those such as I, already lie in the ditches or fields, shot dead. Because I cannot walk any more, and it is not possible for anyone to carry me, because everyone is spent and weary. I turn to my friend, saying I want to run away. He will not risk falling into the hands of the Gestapo. Each day there are fewer of us. He says that he only wants the live. I turn to someone else. He understands the same as I do, that walking further is pointless but his feet no longer serve him; he would be glad to, but cannot; he knows that he could also be a victim for not being able to walk and could be shot on the road, but he does not want to run away. I turn to another couple of friends, but no one wants to give up this absurd life.

I find another friend from Halberstadt, Maks Salomon, a Polish Jew who lost a wife and 2 children in Auschwitz. My conversation with him was a short one: he is ready to end the death-march, because continuing was nonsensical. From the moment that we came to that understanding we stayed together. Both of us understood the responsibility of the risky decision. We both decided in the recent days of our tangled path of suffering to risk it. Being successful would be good, but if not there was nothing left to lose. Outdoors it begins to get dark. The order comes: Get up and march on. We go together, and talk through how to do it and decide that when we come to a dark forest we will run a few steps and throw ourselves on the ground; one will crawl to the right and one to the left; we will not lie still, but keep crawling on all fours.

We march into a forest, both together and hold the other by the hand. The guard around us is thick, we walk with hearts

[Page 512]

pounding, maybe this is the last moment that our hearts will beat. We give each other the agreed-upon signal, leaving the ground of the crew. We let the S.S.-man walking near us get ahead of us and we are slower. He shouts, Faster, louse! In that moment we both break from the crew and run into the dark forest, as the S.S.-man chases after us and shouts, Stand still! We lie on our bellies and crawl on all fours, the wild S.S.-man still shouting, Stand still! He runs a few steps and retreats.

We lie for a few seconds and listen as the crew marches on. We crawl around in the forest, one toward the right and the other left for a few minutes and remain lying and listen again to the quiet of the dark night. Everything around is dead still, we hear the echo of the machine-guns as they kill those who cannot walk; when we can no longer hear the crew we crawl further into the forest. That goes on long enough until we find one another. Now we are both thoroughly spent; we both know our lives are in the balance. We look into the darkness – we do not know where we are. We are each alone in the fear of death, and decide to go out of the forest to the side, in order to orient ourselves where are in the dark, and around everything is dark. At the edge of the forest there is a deep ditch that separates the forest from the road. We sit here exhausted, leaning our shoulders together and look around to see if anyone is coming.

Our eyes bulge out of our heads. They want to sleep, and we try not to fall asleep. The night is unmercifully cold. Sitting there we notice that something is moving in the dark. Now running away makes no sense, we lean back more towards one another, like one paralyzed piece. Quietly a figure in rubber boots comes up to us and says: “Here are two, and here are another two.” And walks on. We remain sitting in deadly fear. When it begins to get a little light we leave that place and come to a village.

There are a few girls in the street. Seeing us they quickly run into a house. Soon someone in a green hat appears on a motorcycle. Now we see that we are caught. He attacks us with a dog-like howl and aims to shoot us. Our blood freezes and we feel this is really the last moment before death. He takes us to a room and locks us in. We see two others in the room, not Jews. After a little time he comes back and unlocks

[Page 513]

the room, holding his gun in his bloody paw. He takes us both and curses, “You bandits, you want to run away!” He shows us 4 shot prisoners in striped clothing in the middle of the street, and shouts “You will be shot the same as they!” He takes us to a field, holding the revolver in his hand and never stops cursing; the human-animal indicates with his boot on the wet earth the size of a grave for us and also the 4 shot who lie in the roads. Then two others come, like him, in civilian clothes, and he orders them to call the mayor.

A very fat German arrives with 4 armed civilians with shovels for us to dig the grave; the first speaks with the mayor about removing the numbers from us after we are shot. We dig and listen to the conversation.

Our blood is frozen in us: now are we going to be dead? We answer to them that we are not bandits but have lost our troop. “No!” he growls, “you wanted to run away,”

There we stand in the field between heaven and earth, the four armed men around us talking among themselves. We stand with the shovels in our hands and dig the cold grave, where our bodies will soon be thrown.

It is hard to think, standing in one's own grave. We dig slowly, so it will last longer. The tears run from our eyes, it is difficult to bring forth a word.

I feel as though my heart has stopped, the blood in my veins is frozen, I am all of 35 years old and now my life will be ended.

My friend Salomon and I are living our last hours. I look around and take leave of everyone in my mind. I think about everything and I want to cry out about our torment, our pain in the world. Everything around us is blooming, everything is alive: the birds sing, the trees are leafing out, and soon we will be thrown into a wet grave.

I think about my family, of my parents, of my 4 brothers and 2 sisters with their families who were killed by the same murderers and burned in the crematoria of Treblinka or Auschwitz. Now it is my turn – yet two years of suffering in the camps of Birkenau, Manievits, Buchenwald, Halberstadt.

I think about my only son who is not even 5 years old.

[Page 514]

Is he alive or not or have the butcher's boys burned him or smashed his little body onto a stone wall. I see everything that is presented to my eyes; I know that I am digging my own grave. My friend speaks of his wife and two children who were burned in the crematoria of Auschwitz.

We stand here and dig, lost to the world. We, two living corpses, have nothing to say. We stand bent under the weight of the Angel of Death and wait for death, it is very hard to bear the last hours of life. Our guards stand around us. The mayor comes and says something to the others. We hear a loud shooting around us. The German with the green hat brings another 4 prisoners, among them 2 Jews from Poland.

Now we are 6 men who are guarded by 4 armed guards. We are still standing by the open grave, looking at the four opposite us. The bandit with the motorcycle suddenly runs quickly away.

We hear shooting in the distance. The mayor comes back and tells us to get out of the grave. He speaks to all 6 of us: “Collect the dead and throw them into the grave, and you will – not be shot.”

We weep for joy, once again among the living. The mayor goes away and we begin to gather those shot and bring them to the grave; all 4 lie near the dug grave. We wrap them individually in garments they were wearing and let them down one after another. This takes until about 12 noon. The grave is covered over. The mayor comes with a large round loaf of bread and an pail of water and gives each of us a piece of bread and a scoop of water.

The 4 guards are armed and we ae standing at the fresh grave. We can hear the shooting. The front, it seems, is very near to us. The German with the motorcycle is not ever coming back. We stand in the same place, and at 2 o'clock a civilian comes and takes all 5 of us off to a small town.

We walk through the streets, everything is closed, the businesses are locked and the shutters are latched. Someone shouts from a distance: “Beat down the shits!” They lead us on, women want to approach and give us something. The civilian guard leading us does not allow this. Everyone around stares at our horrifying condition. We arrive at a

[Page 515]

bridge where there are a few more like us. They are guarded by S.S.-men and they take over guarding us.

Now we are again in the hands of the S.S. The guards run to the other side of the bridge, and we hear a frightening banging.