|

|

|

[Page 139]

The Repercussions of the Pogrom in Siedlce

The three–day–long pogrom in Siedlce was a link in the chain of anti–Semitic pogroms that the reactionary czarists had organized in Russia. The pogroms aroused the liberal world in Russia and beyond its borders. Journalists from foreign and Russian newspapers came to Siedlce to see the tragic outcome. Correspondents came from the “Neue Freie Presse,” the “Daily Mail,” the “Echo de Paris,” the “Gazzetta Faranga,” and Warsaw's “Der Veg,” the only daily Yiddish newspaper in Poland. The uniqueness of the events were portrayed for weeks and months.

The young artist Maurycy Minkowski (killed in an automobile accident in Buenos Aires in 1930), who had almost completed the Arts Academy in Cracow, came to Siedlce in the company of the young journalist Noah Prilutzki. At the train station they were amazed at seeing hundreds of bewildered Jews sitting with their packs and waiting for a train in order to escape the city. With this as his inspiration, the artist created the pictures “Refugees” and “After the Pogrom,” which had an extraordinary success in international shows.

Y.L. Peretz also came soon after the pogrom along with the young writer Menachem Boreysho in order to console the city. Peretz long bore the difficult impressions that the city had made on him[75].

The Russian Duma (Parliament), the Social Democrat Tzeretely spoke out against the regime, against the nightmares it created in Siedlce and Bialystok. The Russian press, too, even though they operated under firm censorship, wrote confidently about the participation of the regime in organizing the pogrom.

The well–known and influential newspaper of that time, the “Petersburg Statement,” wrote: The regime is obliged to seek and find those who are truly guilty of these murders, not excluding their own agents, who lay the entire blame on the Jews.

[Page 140]

The English “Times” emphasized: “It is difficult to publish sympathetic feelings for a regime that helps perpetrate a barbaric slaughter. There is ground for believing that Stolypin is upset that the events in Siedlce help his enemies to undermine him.”

In regard to the pogrom, the French newspaper “Aurore,” the paper of Clemenceau, wrote: “We regret that we believed Stolypin merited being called a liberal prime minister.” The “Berliner Tagblatt” sharply attacked the czarist prime minister: “Stolypin's accomplishments in Russia have been shattered. Will he and his be silent about the events that will also probably take place in Warsaw (There were rumors about preparations for a pogrom in Warsaw–Y.C.)–will he also lose his foreign reputation?”

The Yiddish press reacted strongly and sharply: “Glas Zhidowsky” (in Polish), under the editorship of the lawyer a Hartglass, and the government, as a penalty, had shut down the paper; “Dos Yiddishe Volk” in Vilna, from the 13th of Tishre, 1907, in its lead article had written, “The slaughter in Siedlce has ended, as all slaughters of Jews have ended: with the coming of commissions of ‘inquiry,’ after which comes a message blaming everything on the revolutionaries, while the pogromists fight for higher reasons, and so the story goes.”

“Der Yiddisher Arbeter,” the organ of Tz. K. of the Poale Tzion in Austria reacted in number 32 from 1906 in this language: “How long will Europe regard with equanimity the system led by the czar's underlings? How long will the Jews of Europe see the murders of Russian Jews and be silent after the official excuses of the government because the Jews of eastern and western Europe are absolutely without influence? It is high time that the czarist regime should once and for all cease to exist.”

“Der Neier Veg,” number 18, from 5 (18) September 1906 wrote: “Unable to stifle the revolution by the barbaric and devilish means it has heretofore used, it now tries to fight with new weapons that have never before been used in any country or in any revolution–the

[Page 141]

the government treats the country as a camp of fiends, as a foreign army, which has declared war and will destroy the country. The government makes a ruin of the land, creates everywhere a state of war, sends out punitive expeditions, murder, death, robbery, takes captives, as if there were a bloody war between two devilish peoples.”

“Di Velt,” the organ of the Zionist Action Committee (published in Cologne in the German language), devoted much space to the Siedlce pogrom. This central Zionist mouthpiece brought news and depicted the situation of hundreds who had been arrested before and after the pogrom. The arrested were accused of trying to overthrow the czarist government.

“Ha–tzefirah,” number 251, from the 24th of Kislev 1906, carried a report by the Siedlce maskil K. Galitzki. He recounted that the local committee to support the victims of the Siedlce pogrom had collected 1200 rubles. The money had been sent to Petersburg to the central committee for the victims. The article also describes the attitudes among Siedlce's Jews after the pogrom:

The Jews of Siedlce gathered in the city's beis–medresh to pray. They read the Torah portion “Va'yakhel” {[This is not the name of one of the weekly portions. Rather, it is a passage following the story of the golden calf that is related to repentance–trans. note]. The cantor said a memorial prayer for the martyrs. After the prayers, the rabbi eulogized the fallen.

Also in the city synagogue, the official city cantor, R. Yosef Tiktinski, arranged a prayer service. Also those in attendance wept bitterly.

A gathering to protest the bloodletting was also organized. The protest resolution called for equal rights for all Jews in Russia.

The Effects of the Siedlce Pogrom in America and England

The first alarming news about the Siedlce pogrom appeared on one day, September 10, 1906, in all Jewish newspapers. The “crying heads” told about the frightful experiences of Siedlce's Jews. However, these descriptions of the bloody events in Siedlce

[Page 142]

bore the seal of the czarist information office. The correspondents of the American press bureau “The Associated Press,” it seems, received their information about the Siedlce pogrom directly from the czarist government circles, or they had been influenced by these circles. They received the impression that Stolypin and the Warsaw governor general wanted them to.

So, for instance, at first in the New York “Forward” the pogrom was described in such a manner that it gave the impression that the army in Siedlce was fighting against Bundists and revolutionaries. First A. Litvin, the Forward's special correspondent, warned the one should treat with caution the news from the “Associated Press.” In particular, people's eyes were opened by the news that appeared in the American papers, that Dr. Paul Nathan, the chair of the “Union of Aid for German Jews” had wanted to visit Siedlce and the Russian government had not given him permission to go to the city. This fact emphasized to everyone that the Russian government held back the true story of what had happened in Siedlce.

Already on September 12, 1906, the “Forward” wrote under the heading “In the Civilized Countries, People Remain Silent”:

The Jewish people could have thousands slaughtered and lose whole towns, and the civilized world would not come to help. Our local American republic acts like all the rest: President Roosevelt mixes in everywhere, but when it comes to killing the killing of thousands of Jews, he remains silent. The government in Washington takes on Cuba, but when numberless Jews are killed, when our brothers fall like sheep, not a voice is raised.

The well–known author Yakov Dinenzon writes in a column in the “Yidishe tageblatt” on September 25, 1906:

Is it not time that a fine hero should be found in Europe or in America, someone like your Roosevelt, who would have the diplomatic wisdom and dexterity to interfere in anywhere and bring an end to the terrible war in Russia and make peace.But I doubt that your Roosevelt will test his luck and his wisdom

[Page 143]

once more. But I do not doubt that without such a fine hero from abroad, the battle in Russia will not come to a quick end and the horrors of Russia will spread around the world.Meanwhile we have blood, iron, and fire, pogroms, military trials, hangings, and slaughter in the streets.

In Siedlce, what goes on in the streets? How many killings? How many orphans? How many cripples and new Jewish beggars? Siedlce! Now you are mentioned in all the newspapers, but until now no one spoke about Siedlce.

The “Morning Journal” of September 10, 1906, wrote the following about the incoming news of the pogrom:

The pogrom was not unexpected. Two weeks earlier, on August 24, the European newspapers printed dispatches that police and soldiers in Siedlce were planning a pogrom and that Jews were fleeing from the city. Jews were preparing themselves for the pogrom.

All of the Jewish newspapers in America celebrated in particular the heroic bearing of Siedlce's dozors–Y.N. Wayntroib, M. Temkin, community secretary D. Tshatchkes, and the Siedlce rabbi D.B. Analik–for their intervention with the governor of Siedlce and the murderer Tichinovsky. Also the Russian newspaper “Birzhevi–ya Vyedomosti” printed an article called “Siedlce's Heroes” and stressed the proud bearing and high courage of the Jewish leadership in Siedlce.

After the pogrom in Siedlce, the Jewish community leaders and openly liberal opinions were disturbed in anticipation of further pogroms organized by the government against the Jews. As we have already said, there were fears of such a pogrom in Warsaw.

The current leader of the P.P.S in Galicia, Ignace Dashinski, telegraphed the London “Times” from Cracow that the Russian government had brought in special soldiers who knew how to make a fine slaughter (“Judisches Tageblatt, September 16, 1906).

On the next morning, the same newspaper reported that Dr. Paul Nathan, the chairman of the “Union of Aid for German Jews”

[Page 144]

had sent the following alarming telegram:

A letter from Warsaw reports that Russian and Polish officers from liberal circles believe that a slaughter is imminent for the Jews of Warsaw. Jewish soldiers report as the commanders of their regiments who are quartered in Warsaw made speeches to their troops in which they declared the czar had chosen a day for reckoning with the Jews. In short, since the czar wants them to kill the Jews, the commanders distributed ninety thousand rubles among the soldiers.

The telegrams from Dazhinski and Nathan revealed the intentions behind the proposed danger. The pogrom in Siedlce made the danger even starker by saying that the czar's devilish plan would be carried out in Warsaw. However, no pogrom took place in Warsaw, but daily murders took place there, as Yakov Dinenzon rightly noted in the “Yidishe tageblatt” in his article “Regarding the pogrom in Siedlce.”

When, after the Siedlce pogrom, it became known in other countries that the czar planned to hold military trials for two hundred people among the victims of the czar's army, the Jewish community leaders–David Alexander (director of the “Board of Jewish Deputies” in England), Claude Montefiore (chair of the Anglo–Jewish Association), and Leopold Rothschild (vice–president of the Organizational Bureau) published the following letter in the London “Times”:

As representatives of the Jews in England, we protest the newly–planned battle against our unfortunate brothers in Poland. We hold fast that it violates the limits of propriety that characterize the civilized world that those who committed such atrocities against the Jews of Siedlce should sit as judges against people whom they arrested to cover up their own misdeeds. We ask with pounding hearts that those arrested should receive at the very least impartial trials. From a telegram we have learned that two hundred people were arrested in the confusion and that their fate is in the hands of army judges who have already been chosen. We hope that the voices of civilized lands will prevent this terrible miscarriage of justice.

[Page 145]

Siedlce Jews in America and Their Help for the Victims

At that time there were in America approximately 140 immigrants from Siedlce whose families were still in their hometown. The news in the papers about the pogrom against Siedlce's Jews gave the immigrants a horrible shock.

Several activists among the Siedlce group in New York began to plan an aid program for the pogrom's victims. On the same day, a meeting was organized at which it was decided to call for a mass gathering to found the “Siedlce Pogrom–Relief Committee.” At this gathering, which was poorly organized, there were few people from Siedlce, and the sum that was collected there amounted to about a hundred dollars. A second mass meeting was organized, which was held on September 13, 1906. From a note in the “Forward” under the headline “Siedlce in a River of Blood,” we can see who spoke at the meeting. In the note, we read:

A huge mass meeting is called by the Siedlce branch 53 of the “Arbiter Ring” this Thursday, the 13th of September, at 8 in the evening. Where the following speakers will address the crowd: B. Feygenboym, Dr. Gurewitsch, M. Katz, Dr. Sh. Feskin, Ab. Goldberg, and many others. Come in masses to show sympathy and consolation for the widows and orphans.

We find a report about this mass meeting in the “Yidishes Tageblatt” of September 14, 1906:

Last night at the Terrace Lyceum, 205 East Broadway, a mass meeting was held, called by the Siedlce branch 53, over the terrible pogrom that occurred in Siedlce. Despite the powerful storm that occurred last night, the huge hall was packed with people, who shed many tears as a variety of speakers described the great misfortune that befell Siedlce's Jews. Many pledged donations to the aid fund for the unfortunate people of Siedlce

[Page 146]

For several months, the Siedlce group in New York tried to raise a meaningful sum for aid, but the amount they gathered was very small. The directors of the collection then decided to go the “American Jewish Committee,” which was led by the well–known millionaire Jacob Schiff. This group had gathered a huge sum to aid pogrom victims in Russia. Some of the money was sent to London in case of a pogrom–which was a frequent phenomenon in czarist Russia–so that help could be conveyed quickly. The Siedlce representatives wanted some of this money to be sent to the victims of the Siedlce pogrom.

According to Sh. Tcharnabrode in his memoirs, which were given after his death to the YIVO in New York, the lawyer Louis Julian (Slushne), a son of Yoel Julian (Slushne), the chair of the Siedlce “Pogrom Relief Committee,” went on behalf of the committee with a letter to Jacob Schiff proposing a meeting between him and the committee. Jacob Schiff quickly responded to letter, saying that he was prepared to meet with the committee.

Jacob Schiff warmly received the delegation, which consisted of three people: the committee chair, the already mentioned Julian (Slushne), his son Louis the lawyer (who was not a member of the committee), and Harry Green.

As soon as the Siedlce committee arrived, Schiff remarked that he knew why they had come to him and he had already done what they wanted. He showed the delegation a telegram that he had received from Claude Montefiore. This was a response to Jacob Schiff's telegram that they should send a meaningful sum for the pogrom victims in Siedlce. Claude Montefiore told Schiff that they had sent seventy–five thousand rubles to Baron Ginzburg in Petersburg, with the proviso that the Baron should send the money to Siedlce.

The Siedlce “Pogrom Relief Committee” rejoiced over Jacob Schiff's answer that such a sum

[Page 147]

had been sent. The help of the American committee revived the Siedlce group. The committee members became even more fervent in their efforts.

Emigrants from the pogrom came to New York, fleeing from Siedlce. They no longer wished to remain in the city that oppressed them to death. Those who arrived declared that irresponsible do–gooders had taken over the Siedlce committee, and they put their own financial welfare first. This news made a strong impression on the committee members in New York. The matter went so far that the New York “Pogrom Relief Committee”decided not to send funds to Siedlce, but to use it for grants for the newly arrived immigrants. But when the relief committee went to the Yarmalawski Bank, where the money was located, the bank refused to hand over the money, with the warning that the money was intended to be sent to Siedlce. When negotiations with the bank produced no results, it was decided not to put any more funds into that bank and that any money yet to be collected should be used for grants for the new immigrants, whose number in America–particularly in New York–was growing from day to day.

The “Pogrom Relief Committee” was dissolved in 1907. It had done much for the victims of the pogrom. Despite the malevolent warning about the activities of the Siedlce committee in helping the pogrom's victims, one must stress that the committee provided sums of money for the reconstruction of ruined houses and burned buildings, stolen merchandise, and grants to buy passage for emigration to Copenhagen, America, o Eretz Yisroel, where the emigrants from Siedlce had begun to go. From the assembled funds, a total of a thousand rubles was designated fir the opening of the “savings and loan,” which in later years became the “Udzhalovi Bank,” one of the largest cooperative banks in Poland. The descriptions of the immigrants had been exaggerated and smelled of gossip.

[Page 148]

The Siedlce Pogrom in Folk Song and in the Light of History

The pogrom in Siedlce had no Bialik, who could publish artistic accounts of his sorrow and fury over the form of Jew–extermination (the military pogrom) that the czarist government had developed. But the people themselves considered the horrible murders of Siedlce's Jews.

In the course of long years–almost a whole generation, until Hitler's extermination of the Jews–the bloody misfortune lived in the people's memories. Parents told their children about those nightmarish days. The people created a song that was sung to a melancholy tune.

The song consisted of 12–14 stanzas and told in rhyme what had happened in the city. Sadly, no one wrote down the text of the song, and so from oral memories of those who lived through the pogrom, we can present only six stanzas:

On Shabbos evening, after their meal

the Jews wrung their hands in fright.

They never could have imagined

how terrible would be that night.In attics and basements we sat hidden,

afraid for our very souls.

The Labovsk swine[76] ran wild in the courtyards.

Destroying our lives was their goal.The feathers, they all went a–flying

as in winter comes down the snow;

our gold, silver, diamonds, and jewelry

off with the bandits did go.Yitzchak the well–known butcher[77]

tried to defy the toughs–

they hit his head with their rifles

and ran off with all of his stuff.

[Page 149]

Just listen, Abraham the goy,[78]

don't think that it will be so.

You ordered the deaths of children

and the cost of children's blood you will know.In your own little town,

be sure you look around–

lest someone throw a bomb.

The pogrom in Siedlce received attention in historical accounts, which appeared in later years. The great historian and martyr Shimon Dubnow unfortunately described the murders in Siedlce in his latest history of the Jewish people, but in several spots he included errors. Thus, for instance, Professor Sh. Dubnow calls the pogrom's organizer “Tichanovitsch” rather than his correct name, Tichanovsky. Dubnow writes:

––––––The head of the security police in Siedlce, Tichanovitsch, planned a bloody military pogrom (8–10 September)–casualties included 30 killed and 150 injured Jews. The pretext was a provocative shooting at soldiers, after which the army opened a wild volley in the streets and bombed Jewish houses. A second agent from the local “Okhrana,” a police official, delivered an official report that the Jews had no pretext for a pogrom and that it was entirely a planned police action; nevertheless, the guilty Tichanovitsch was not punished, but instead received thanks from the Warsaw Governor General “for his efforts in restoring order”[79].

In 1916, in Prague, Czechoslovakia, a brochure was published in German in which the author, Avraham Greenberg, described the Siedlce pogrom. The author did not cut down on exaggerations[80].

The historian of the Polish workers' movement–Stanislaw Martinowski–in 1936 published in Lodz, in Polish, a work in which he dealt with the 1906 Siedlce pogrom.

[Page 150]

In 1947, the writer of the present work published, for the fortieth anniversary of the Siedlce pogrom, a Hebrew monograph about the events in Siedlce[81].

The End of the Pogrom Heroes

The murderer Tichinovsky died after great suffering a short time after the pogrom. While he was handling his revolver, a bullet was discharged and hit the pogrom hero, from which he developed blood poisoning. For a while he lay unconscious. He would cry out that the Jewish dead, his victims, would not allow him to rest. When he regained consciousness, he told his colleagues–the officers closest to him–that he feared assassination from the Jews, and he begged them that if anyone actually killed him, they should take vengeance on the Jews with a second slaughter. A short time thereafter, this evil man gave up his unclean ghost. A short time before his death, it became known that Czar Nicholas II at issued an “imperial thanks” and gave gifts to a number of Black Hundred heroes who excelled in conducting pogroms and slaughters against the Jews of Russia. Tichanovsky was singled out.

Tichanovsky had received a welcoming telegram from the Black Hundreds in Yelisavetgrad (South Russia). He responded to this telegram with thanks: “I thank the loyal Russian men. Bayonets are mightier than rags.”

Governor Volozhin left Siedlce in 1912, when the district was dissolved. He went to Chelm, and from there–to Petersburg, where he assumed the position of head of the Police Department. Finally he became the head of the Holy Synod.

At the time of the revolutionary storm in 1917, Volozhin and his wife, Madam Dolgorukov, who had come from an aristocratic background, fled to France. These czarist notables in 1932 lived in the Riviera town Boulogne–sur–Mer and survived by running a spice shop.

The czarist government later persecuted Pyetuchov for his

[Page 151]

report to Skalan about the pogrom. As a punishment, he was sent from Siedlce to Riga. A couple of years after the pogrom, a judgment was made against him for three rubles of army funds. Thus did the czarist government get vengeance against Pietuchov for his report to Skalan about the Siedlce pogrom, which had caused the government such trouble.

Zionist and Cultural Activities After the Pogrom

After the pogrom, all activities of the Jewish community were directed toward helping the victims, taking care of the orphans, appealing to Petersburg, and so on. Then was established the “Esras Yesomim” (Orphans' Aid), which later developed into a major organization to aid orphans. Slowly the Zionist movement came back to life, as did the activities of the socialist parties that existed illegally in Siedlce. At that time, a group of Poale Zion was organized in Siedlce.

How the Zionist activities in the summer of 1906, before the pogrom, appeared, we can see in the description in the memoirs of Shimon Tcharnobrode.

In his memoir, Tcharnobrode says:

It was in the summer of 1906. Zionist work in Siedlce was feeble. Aaron Menachem Gurewitsch was the Zionist leader in town. The only Zionist activity was that every Shabbos Mr. A.M. Gurewitsch would speak about Zionist and general Jewish questions.Although I was then very young, I was a member of “Ha–tekhia” (a democratic–Zionist youth organization). I went to hear his talks. But I was quite unhappy about the feebleness of the Zionist activities that took place in Siedlce.

One time on Shabbos, in the summer of the Siedlce pogrom, I heard that there would be a talk by Mr. A.M. Gurewitsch. I went to hear the talk. After the talk, I approached Gurewitsch with a question: Why was Zionist activity so pathetic?

[Page 152]

Mr. A.M. Gurewitsch responded that he was glad to hear that I was dissatisfied with the state of Zionist work and he advised me to think of activities.

In the summer of the Siedlce pogrom, I threw myself heart and soul into Zionist work. Zionism, the Zionist movement, became my ideal…In fact the organizational work got a good start, but in the middle of his Zionist activities, A.M. Gurewitsch [trans. note–Sometimes he says “A.M.” and sometimes “M.A.”] had to leave Siedlce for Odessa for a Zionist gathering that M.M. Usishkin had called on his own initiative. Because of czarist prohibitions, this gathering was held illegally in a summerhouse near Odessa.

M.A. Gurewitsch received an invitation to the gathering and so went to Odessa[82].

As we noted earlier, the democratic–Zionist organization “Ha–tekhiah” smuggled weapons into Siedlce when it became known that the government was preparing a pogrom against the Jews. “Ha–tekhia” wanted to create a real self–defense organization.

Soon after the pogrom, an exodus from the city began. Mainly people headed for America, but a certain group of Zionist and Poale Tzion members went to Eretz Yisroel. The so–called Second Aliyah to Eretz Yisroel was then under way, comprised of idealists; not everyone, however, could withstand the harsh conditions of the journey, so some returned. But some struck deep roots in the life of Eretz Yisroel.

The emigration of Siedlce's young people to Eretz Yisroel made a strong impression, as did the letters they sent, in which they described their lives as farmers in the Galilee or Judea. The impression became even stronger. The Poale Tzion published their Poltava Platform, which strengthened the Zionist influence among the masses. One of the effects in the city was the strengthening of ties to Eretz Yisroel through the

[Page 153]

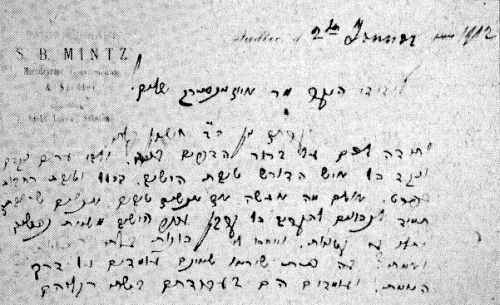

involvement of the bank Sh. B. Mintz and Yehoshua Goldfarb, who was born in Mezrich. The two partners had opened bank offices in Siedlce with branches in Mezrich, Byala Podolsk, Lukow, and Sokolow.

About Yehoshua Goldfarb we know that he was born in 1867. His father, R. Moyshe, took part in the Khivas Tzion movement and was among the founders of “Yesod Ha–ma'alah” [a settlement in Palestine], and by profession a brewer. Yehoshua also belonged to the “Khov'vey Tzion.” As he grew older, he was a member of the “Benei Moyshe.” From Siedlce he went to Eretz Yisroel, and there, together with Zev Gluskin of Warsaw, founded the wine business “Carmel” and was also among the founders of “Menucha ve'Nakhalah”–the creators of Rekhovot.

|

|

At first, Yehoshua visited Eretz Yisroel as a tourist. Later, in 1909, he settled in Rekhovot and was active in local community life and became involved with the colony's committee. A while later he moved to Tel Aviv and founded a business by the name of “Kadmas Ha–aretz,” which bought property around Tel Aviv. At the time of the First World War, Goldfarb lost all the money that he had left in Poland. In Eretz Yisroel, he helped to fund the large Tel

[Page 154]

Aviv bank “Kupas Am,” which planted an almond grove in Rekhovot.

Before and during the First World War, as long as Siedlce found itself under the domination of the czarist government, there was no possibility of discussion of greater Zionist activity. The most work went into organizing meetings and lectures that were laboriously prepared by Greenboym, Hartglass, and others. Such gatherings were held conspiratorially or under other pretexts so that the Russian government would not seize them. With the end of the czarist regime, the Zionist movement became livelier. It moved from being a small circle to a mass movement.

Before the outbreak of the war, a group of Zionist young people came to Eretz Yisroel. Among them was the later–to–be leftist Poale Tzion leader Yosef Slushni. For various reasons, whether because of illness or economic problems, some of them went back to Siedlce. Yosef Slushni also came back and undertook broad business activities.

At that time a new boom took place in Siedlce's Jewish life. The workers' parties, the “Bund” and the “Poale Tzion,” which had been illegal, began to show lively activities. The only place where this openly Jewish community life was on display was the aforementioned library and the “Ha–zamir” Society.

The “Ha–zamir” Society came into existence in the difficult years after the pogrom. In those dark days of great apathy and indifference toward community life, in August of 1908 a small group of wise people, lovers of literature and music, gathered and founded a society under the name of “Ha–zamir” [The Nightingale], which a short time later was changed to “The Literary–Musical Society of Jewish Arts.” It is strange that the creation of such a society occurred in such difficult times.

For the opening of “Ha–zamir”, the writer Tchemerinsky (R. Mordechayele) was brought in. The atmosphere was

[Page 155]

dignified. The following comprised the first committee: Kalman Golitzky, Matityahu Mintz, Yitzchak Eliyahu Zucker, Avraham Ziglwaks, Moyshe Volovsky, Berl Mintz, and Yosef Rozenzumen. The committee had developed a broad set of activities involving music and literature. There was a chorus, a drama section, and an orchestra. They also arranged readings by Kalman Golitzky and lecturers who were brought in from Warsaw.

The activities of this cultural institution were influential in the community life of Siedlce, and “Ha–zamir” helped to strengthen the spiritual and national life of the depressed population of Siedlce.

The czarist government watched the community closely and began to persecute it. The early signs were obvious. Meetings were not permitted. The local society was told that its hall would be closed. Only thanks to the intervention of Y.N. Wayntroib did the society continue to exist.

In 1912, “Ha–zamir” changed its name to “Jewish Arts.” The following were added to the society: M. Mandelman, Berl Tcharnabrade, and Asher Liverant, Genia Halbershtam, Tirzeh Zucker, Rochel Edelshteyn, Bronia Goldberg. Thanks to these people, the society developed quickly.

At the same time, the aforementioned library also developed. It was founded in 1900. By 1912, the number of books had more than doubled to more than 2,500. However, it lacked a systematic catalogue and a list of subscribers. In order to broaden the activities of the library, a project was instituted to unite the library with “Ha–zamir,” which had already changed its name to “Jewish Arts” According to its by–laws, the society could incorporate a library, so that the existing library in the name of M.M. Landau transferred to “Ha–zamir.” Under its new custodians, the library flourished. First, it had a larger location, and in its

[Page 156]

first two years, until the outbreak of the First World War, the numbers of readers increased to over three hundred.

When the war broke out, the military government threw the library out and requisitioned their building. Thankfully the books were taken care of by the committee, like an eye in the head [that is, they were treasured]. The hard times and the concern for their continued existence tore the library workers from their work. There was a danger that the library would disappear, but thanks to the energy and concern of a group of devoted guardians from the cultural organization, the library remained unhurt. Keep in mind that no purchases were made, because there was nothing available to buy, which meant that a sum of money remained. This meant that during the German occupation, a fine location for the library could be found on what was then Warsaw Street.

The First Jewish Periodical Publication in Siedlce

In December of 1911, the first published periodical appeared in Siedlce. “The Shedletzer Vort” [“The Siedlce Word”]–that was the name of the small, thin booklet, as big as a small little prayer book. “The Shedletzer Vort” was considered a rarity in those days, when it was not so easy to distribute a newspaper in Russia, especially in Yiddish. Therefore this little booklet had a special charm, despite its poor appearance.

This publication was thanks to the travelling loner, the ailing Avraham Gilbert (cousin of the well–known writer Sh. Gilbert) who arrived in Siedlce with a small press and some printing type, in order to open there a publishing house and derive a little income. It could be that Avraham Gilbert came to Siedlce because of his brother Moyshe, the Siedlce resident, Russian teacher, and overall active member of the “Agudas Achim,” an organization that at that time played an important role in the cultural and community life of the city. Moyshe was a man of talent and used to write songs, parodies, humoresques, fables about local

[Page 157]

concerns. He often appeared with his creations at concerts and evening events that were organized by the “Agudas Achim.” He had a large following in the local community. From sheer delight, people often carried him around on their shoulders.

Because he had no work and no income, Gilbert struck upon the idea of issuing a weekly paper. He brought the printing equipment with him, along with printing type, and he knew how to write…

Gilbert confided his plans to Dovid Neumark, a religious frequenter of the beis–medresh who later became a Bund activist and an editor of the Bundist publication–the “Folkszeitung” [the “People's Newspaper”]. (Today in New York is works at the “Forward” and “Der Vekker.”) Neumark told the secret plan to Fishman, who later wrote a book of stories called “Summer Days” (Warsaw, 1938) and “Homeless Jews” (Shanghai, 1948). The three of them came to an agreement and decided to publish a Siedlce newspaper.

The birth of the journal was accompanied by great labor, because he had too little printing type and he had to do all the work himself. He could not even think of taking on an assistant because his finances would not allow him to.

Despite these circumstances, the “Shedletzer Vort” was born. Neumark treated “Ha–zamir.” He printed a story by A. Maidanik, a translation from Hebrew. Avraham Gilbert was represented by two poems and Y.Kh. Fishman with his first tale, “A Chasidic Story,” under the pseudonym Y.Tz. L'vavitsch. Itsche Altshuler also wrote a short article.

It took two weeks to print the paper, because there was only enough type for half a column, and each column was printed twice. In the second issue, which appeared in 1912, he was assisted by Yakov Tenenboym and Yehoshua Goldberg. He printed a kind of local poem under the name “Siedlce Panorama,” which was quite successful. It provided descriptions of well–known Siedlce personalities.

[Page 158]

The “Sedletzer Vort” was liked by its readers, but not by the czarist government. The police arrived at Gilbert's pathetic publishing house and confiscated the forbidden materials.

Avraham Gilbert, lost the courage to continue, and his pioneering spirit was taken over by Yakov Tenenboym, who had participated in the second issue of the “Shedletzer Vort.” Yakov Tenenboym was by profession a country doctor. Although he was absent–minded, his writing was sharply funny, impactful, satirical, and flashy. When Tenenboym became interested in Journalism, he was already about thirty years old and had five children. Everybody wondered when Tenenboym became a journalist and had the idea to put out a weekly paper.

The writing was very difficult for Tenenboym, especially because he alone had to fill three–quarters of the paper. He brought Y.H. Fishman into the work. Fishman, then about twenty years old, at first was unwilling to do the work, but eventually he became involved in the writing. He and Tenenboym would sit all day, and often into the night, working on the paper.

Because of his journalistic work, Tenenboym neglected his medical practice. It appears that the ailing did not wait for him.

Tenenboym also approached his offended friend Yehoshua Goldberg about working with him on the paper. Goldberg was about the same age as Tenenboym. They were friends since childhood, but they had a falling out when they began working in journalism…because Yehoshua had brought into Tenenboym's room his poem for the journal, but he put the manuscript onto the table and not handed it to Tenenboym. There was a kind of literary jealousy between them. Tenenboym envied Goldberg because of his talent. Yehoshua had already published poems in a Warsaw literary magazine.

At the same time, Yoel Mastboym showed up–Yehoshua's

[Page 159]

young friend, who had begun to write. Goldberg edited the “Shedletzer Vokhenblatt” for three years. There he wrote sketches and feuilletons that described life in the city. His feuilletons, “From the Tales of Siedlce” and the cycle “My Teachers” were sources of Siedlce folklore, which, sadly, have still not been put into book form.

With Goldberg's help, Tenenboym later began to put out a new paper that was called “Siedlce Life.” The editorial was by the lawyer A. Hartglass, who at that time lived in Siedlce. Hartglass was not invited to take part in the work, but it happened that he wanted to participate. He announced his desire to write for the paper. Naturally the editors happily welcomed him. He wrote his article in Yiddish, but his Yiddish was full of errors. It was called “Our Defects,” and criticized the Russification of the Jewish intelligentsia. As an example, he cited an advertisement for the earlier newspaper by a reader named Yagodzinsky. The advertisement was written in Russian.

Y.Kh. Fishman also published a story about the bad luck of the former rabbi of Siedlce, R. Yisroel Meizels, the son of the famous Warsaw rabbi Berish Meizels, who had been the official rabbi of Siedlce (1858–1867). We wrote about him in an earlier chapter.

After the second issue, there was, as is customary among Jews, a rift: Goldberg and Tenenboym left and put out another paper, the “Shedletzer Viderkol” [the “Siedlce Echo”]. (All subsequent publications bore the first word “Shedletzer.”) The first issue appeared in a large format, on yellow paper with nice graphics. IT was printed by Yehoshua Lichtenfacht. Tenenboym, as always, had filled the paper with articles and notices that filled all the pages. The articles and notices filled both sides of the pages, and their focus was the face of the city.

[Page 160]

Before the publication of the second issue, a sensation was created when the lawyer A.M. Hartglass submitted an article that drew the attention of all the Jews in Siedlce because of its sharp attack on the anti–semitic article by Dr. St. Wansowski in “Glos Podloski.” St. Wansowski was then profoundly anti–semitic and called for a war against the Jews. (Later he became a liberal and supported the Jews.) His article was called “The Uplifted Weapons.” As he argued against Wansowski, Hartglass found it necessary to make certain observations about the Jewish population, about their behavior at certain times. These observations upset Tenenboym. In the same issue in which Hartglass' article appeared, Tenenboym printed a long critical article arguing with these observations about Sidelce's Jews.

Hartglass would not let this go, so he immediately sent a longer response in which he demonstrated that Tenenboym was mistaken.

Tenenboym had already prepared an array of pamphlets against prominent people and community leaders, but he had nowhere to publish them. It appears that someone had intervened and the police arrived at his print shop, confiscated the remaining copies of the “Shedletzer Viderkol,” and strongly warned him not to continue publishing the journal. Tenenboym also faced a trial, but his father Chaim–Michael intervened. He did whatever he could…and he protected his Yankel from a judgment.

Gilbert, too, seeing what had happened to Tenenboym, published a third issue of “Shedletzer lebn,” and thus ended the first period of the Jewish press in Siedlce. Gilbert resigned and left Siedlce and went to Switzerland to heal his ailing lungs. It is a shame, a true shame, that no trace remains of these publications. Y.H. Fishman writes about all these publications in his unpublished memoirs[84].

Aside from the newspapers, A. Gilbert and D. Neumark published a small book of poems, “Die Nachtigall” [“The Nightingale”], which contained mostly poems by Gilbert.

[Page 161]

The Time of the First World War and in Independent Poland

The First World War broke out, as is well known, on August 1, 1914. In Siedlce was quartered the north–west headquarters of the Russian army, led by General Danilov. General Danilov, it appears, was not anti–semitic, and at the behest of Rabbi Rubenshteyn, made efforts to stop the expulsions of the Jews from the eastern front. Since this matter concerns Siedlce, we will discuss it further on.

Rabbi Rubenshteyn, the former rabbi of Vilna and senator in the Polish senate, describes in his memoirs[85] his visit to Siedlce at the beginning of the First World War and his meeting with General Danilov:

Pesach was approaching–so says Rabbi Rubenshteyn–and people were concerned about getting matzo to the Jewish soldiers at the front. In this cause, Rabbi Rubenshteyn went to General Danilov and asked him for permission to take matzos to the front.

General Danilov's quarters were in a military train. His train car stood by a special platform of the Siedlce train station. No civilian could approach it, except with great difficulty. Rabbi Rubenshteyn had identification papers from Duke Tamanov. On the basis of these papers, Danilov, by telephone, allowed Rubenshteyn to visit him. After the army security had checked out Rabbi Rubenshteyn's papers, he was taken to the train.

Danilov's adjutant led Rabbi Rubenshteyn to the welcome car. From there he was taken to Danilov's private living quarters on the train, which were decorated like a luxury dwelling, ornamented with mirrors and pottery and doors made of polished glass.

The rabbi stated the purpose of his visit. At first the general was doubtful about whether it was necessary or important to bring matzos to the Jewish soldiers in the midst of combat. He also had doubts about whether it was possible. Transport,

[Page 162]

Danilov said, was beset by many problems. The trains were needed for carrying soldiers and ammunition. Every village had lost its normal peacefulness and private comforts. The Greek Orthodox soldiers–he said–would also not receive their religious “treats.”

After Rabbi Rubenshteyn explained the importance of matzos for Jews, the importance of the mitzvah, which was much more important than the Russian custom of eating sweets for Easter, Danilov agreed that it was not fitting to force Jews to eat chametz on Pesach, and it would not be proper. Nor would it be wise to upset the religious conscience of soldiers in the trenches when they felt themselves face to face with death. Danilov responded: “Nu, gut [translator's note: I doubt that the general said “Nu, gut”] send the matzos. Give me instructions and I will order that the matzos should be taken at the right time and should be divided in the proper way among the Jewish soldiers.”

The staff commander also dealt with the rabbi's second request, that the army should send the matzos by military trains and the “Jewish Committee Concerning Matzos” should be freed from paying transport feels. The committee had saved up scores of rubles for this, an amazing sum in those hard times.

When the rabbi had finished his discussion of the matzos, the general spoke with him about other things. His courtesy greatly impressed the Vilna rabbi. The general paid several compliments to the record of the Jewish soldiers, who impressed him with their service. The courteous behavior of the general gave the rabbi courage to raise other Jewish matters. He set before him the anti–Jewish incitement, he described the woes of the “homeless,” their being sent to Siberia without trials after baseless accusations of espionage.

General Danilov responded that his duty was to worry about what the army needed at the front and to preserve order behind the front.

Rabbi Rubenshteyn left the general, and when he arrived at home, he sent a telegram with new questions about how to care for the matzos. Once again the

[Page 163]

rabbi telegraphed the general and asked for a second audience.

This time, too, the general was very courteous and agreed to meet the rabbi in two days.

In a second case–explains Rabbi Rubenshteyn–he came to Siedlce with a delegation from Warsaw in order to intervene with General Danilov and ask him to introduce the Jewish delegation to the head of the general staff Alexeyev, to whom the delegation wanted to complain about military and civilian authorities who created such sorrows for the Polish Jews. Their chief request was: people should not exile the “homeless” in Warsaw, and the aid committee, which had raised sums of money from the royal committee in Petersburg, should cease abusing the Jews. The delegation also knew of a plan to deport the Warsaw Jews that the local powers had devised, and they wanted to touch upon the issue.

On the same day, a telegram arrived in Siedlce at the address of Rabbi Rubenshteyn that said that there was also an order to deport the Jews of Lithuania. The expulsion was supposed to encompass all the districts in the region: Vilna, Gradno, the length of the Nieman and the area from Kovno to Bialystok. The delegation, led by Rabbi Rubenshteyn had the assignment to confer with General Danilov, who was headquartered in Siedlce, and to have him nullify the decrees of Jewish expulsion from Warsaw and the right bank of the Nieman.

The night before the audience, General Danilov ordered that Rabbi Rubenshteyn be found in Siedlce in order to request that Rabbi Rubenshteyn should come to him without the rest of the Warsaw delegation.

When Rabbi Rubenshteyn conveyed his requests to the general, Danilov said that the orders about the Nieman were not in his jurisdiction. But he promised that he had already gone to the general of the tenth district and inquired why he had not carried out the orders of the head of the general staff to cease oppressing the Jews, but General Ratzkevitsch answered that in his jurisdiction he made the decisions and in the tenth district he could do what he wanted, because he was responsible

[Page 164]

for security. Be assured–Danilov told the rabbi–I would not allow such things.

The Nieman was the boundary between the front and the hinterlands–the Rabbi went on–and Jews were being driven out from the shtetl of Trok and from the areas on the right bank of the river, which was under the control of Your Excellency.

Impossible–the general said–the Jews are hysterical and they are fantasizing.

The Vilna Rabbi assured him that he had received a telegram from the Vilna community that clearly stated that all the Jews from those areas, including the Jews of Trok, which was near Vilna, were awaiting expulsion.

The general became upset, and in order to counter Rubenshteyn, he sent a telegram to Duke Tumanov, asking him whether it was correct that an order had been issued to expel the Jews from the right bank of the Nieman. In just a moment, even before the audience ended, Tumanov's reply arrived. He confirmed the news. He said that the order had been issued by General Ratzkevitsch.

As soon as the answer arrived, Rabbi Rubenshteyn took heart and began again to argue: It is impossible that the expulsion of Jews from a shtetl only a few kilometers from Vilna should not include the Jews of Vilna, who would also be expelled. Can they issue such an order without your knowledge!

Danilov became furious with General Ratzkevitsch and said: “Vilna is always under my control–the Jews will not be expelled!” Danilov assured him that the Jews of Warsaw would also not be expelled.

As later became obvious, General Danilov did a lot for the Jews in that area in his capacity of commander at the front.

On August 12, 1915, the Russian army began to evacuate Siedlce and retreat from Poland. The Hebrew daily paper

[Page 165]

“Ha–Tzefirah” gives the following description of how the city was handed over to the Germans:

The police left the city on Wednesday, August 11, 1915, and the militia took over the post office. At night shooting was heard and flames appeared. Government buildings were burning and the depot blew up.After midnight the Cossacks arrived in the city. They tore the doors of the largest stores in Siedlce and stole merchandise. Several of these thieves broke into the dwelling of a rich man and forced him to hand over all of his money. Later on, another group arrived, searched around and took another 1250 rubles. The Cossacks spent the whole night going from house to house and stealing.

On Thursday, at 10 in the morning, a German patrol arrived in the city. Then the Germans entered the city from all directions[86].

After the Germans occupied the city, a civilian committee with a German governor managed Siedlce. The electric station, which was founded in 1906 and was destroyed in the war, was relaunched by the Germans, first as a private concern and in 1918 it was turned over to the city. The total electric output was very little, consisting of a single machine of 75 horsepower.

Thanks to poverty and hunger, a typhus epidemic broke out in the city. In the Jewish population, which was undernourished, there were many deaths. Religious people in the city sought a charm to halt the epidemic. They believed that people should hold a wedding in the ceremony and conduct a burial for “sacred papers” and torn holy books that had been stored in the “genizah” of the city shul and in the beis–medresh. Both activities, which are noted down in the Jewish Hand–Encyclopedia[87] and in a folklore collection , in “R”shimoys”[88], were carried out. In the former case, a wedding was conducted in the cemetery of the Kerkutzka Street cemetery (the last cemetery)

[Page 166]

between Yidl the “Tzenerkop” [something like “with the head of a teenager–not a compliment], who was a well–known porter, and a mute girl. As for the burial, many Jews took part. Socres of wagons and stacks of ruined documents were brought for burial.

|

|

Of the nine doctors who lived in the city on the outbreak of the war, only three remained. Several had been drafted into the Russian army as combat doctors, while others, together with the nurses, had been evacuated to Russia.

Although in the city and in the surrounding areas there had been no major battles, even in the early days many sick and wounded had arrived. From the twelfth of August until the fifteenth of September, 38 wounded soldiers from the German and Austrian armies lay in the city hospital, two officers and 111 Russian soldiers; 32 of them died.

Regarding the attitude of many Poles in Siedlce toward the Jews, we can see this in an article that was published in an American newspaper. The author, M. Zeidman, gives many details that demonstrate the evil attitude of the Poles toward the Jewish citizens.

At that time, masses of Jewish refugees streamed toward Siedlce (“the homeless”). These “homeless” were driven out of Brisk, Kobrin, Pinsk, and Grayevo. The newspaper explains:

The organization that had been founded to help the Jewish unemployed also helped the refugees; to this end they instituted a tax on meat and schmaltz. The tax raised, in its first month, twelve hundred rubles. Soup kitchens were also established[89].

An accurate picture of Jewish life in Siedlce under the German

[Page 167]

occupation in the First World War can be found in a report published in the Yiddish press in America by two women from Siedlce, Bracha and Chana Kagan–daughters of the Siedlce butcher Hershel Kagan[90]–the two women left Siedlce and by various means arrived in Rotterdam, then took the ship “Norttdam” to New York. The immigrants were invited by the club of Siedlce immigrants to report about the situation of Siedlce's Jews. Later the report ws published in one of the Yiddish papers. The report, which can be found in the Sh. Tcharnebrode Collection of YIVO in New York. We give a characteristic description of that time with certain stylistic and orthographic changes:

Sisters and brothers from Siedlce!It has been a short time since I left Siedlce, from the place where I lived together with your parents, together with your dearest and most beloved. For the whole time since the outbreak of the war, it has been 31 months of sorrows and troubles. Now I stand before you and will give you greetings from everyone with whom I lived.

But what shall I tell you about?

How can one say in words all the troubles of 31 months? There were troubles the like of which the world does not know. The worst inquisitor could not dream them up. They were inhuman troubles, that no human language can express. No words have been created for such pains and horrors.

How can one convey the weeping of women whose husbands and children were taken by battle?

How can one convey the sorrow of broken, destroyed peaceful homes, on which people worked hard and strained for their whole lives?

How can one find words to describe the devastation of children whose fathers were killed in the war and whose mothers died of disease?

How can one convey the moments that people live amidst the agony of death for weeks and months?

[Page 168]

How can one present the times when people are caged on all sides and receive the worst news about death and devastation?How do you anticipate the time when the enemy pursues you from the outside and inside you are frightened by terrible reports?

It is awful when one begins to recall all the images, images of blood and marrow, of young and old, of women, men and even young children; these are images that slice into the deepest part of your heart and create new wounds. These are images that pile one atrocity atop another, and all together torment mercilessly, although you want to forget them immediately; but how can one forget such images, when it all continues even now?…

It is difficult for me to describe the different images pervaded by such horror. They contain pain that cannot be eased. The only thing you can do is give a little bread and thereby mitigate some of their hunger pangs.

People of Siedlce!

Can you imagine what they are going through, lacking even a piece of bread? Can you understand what it means: weak old men, pale young women have to work and dig the earth just to get a piece of bread? Can you grasp how deep the pain is when old religious Jews permit themselves to work on Shabbos just for a piece of black bread?

Hunger!!! That is the main horror there. At four in the morning (because it is not permitted to go out earlier), you can see on the streets men with ashen, melancholy faces in whose eyes burns the fever of hunger. They head for the lines where, beginning at 8 o'clock, they will receive a half pound of black brad, baked with potatoes. They hurry there! They have left at home their starving children, who have waited from the day before, or even the day before that, for a piece of bread. And there is already a line of a hundred men, women and children. The door of the store is locked, the windows are closed, and the line keeps growing. extending to other streets. Then a window opens, through which the bread is given

[Page 169]

and the whole mass of people move forward. There is pushing and shoving. They know that if they are not among the first, they won't get bread. Often, very often, more than half return home sorrowfully, desperate and hopeless. Therefore they are ready to turn on each other in order to get bread, but now along come the whips of the Germans and more than one woman or man or child remains lying wounded and bloodied in the street…The horrible epidemics–typhus and tuberculosis–rule free and wide over those weakened by hunger. And how awful is the situation of the sick. People would always sell their last piece of clothing to help the ill, but now they are afraid to summon a doctor, but as soon as a sick person develops a fever, they are required to remove the patient from the house and send him to a special hospital for infectious diseases outside of the city. The house is closed up, and no one is allowed to see the patient in the hospital, and often no one knows what happened to the corpse. Usually the corpses are burned. Consequently, most of the time people decide to remain at home without medical help or to go to the regular hospital.

The jails are packed with “lawbreakers” who steal bread or other products in the city.

How awful, how horrible is the treatment of the prisoners! They get almost nothing to eat! They are disinfected and forced to perform hard labor. It seldom happens that anyone leaves the jail. Death rules there!

People of Siedlce!

It is difficult for me to convey all the prior and current sorrows of our dearest and most beloved. I can only say that hunger is the worst manifestation of recent times.

Do you know what hunger entails? You cannot feel it, you can only understand. Whoever has not seen the evidence of hunger in Siedlce, when hundreds of women go to the local leaders and one cry–“Bread”–can be heard, cannot understand that all other issues disappear, become

[Page 170]

as nothing under the single cry for bread, which takes first place and cries out for an answer when no answer can be given.The eyes of all your beloved on that side of that ocean turn to you. You are the only people from whom they can now expect anything. You have the duty to help them and you must help them.

This description of Jewish life in Siedlce after the outbreak of the war pertains to the first period of fighting. Later on, things improved a little. The military rulers began to give orders for shoes, which restored employment in the shoe factory. At the same time there was a shortage of workers because so many shoemakers had been mobilized over the past year, until the Russians had lost the city.

A similar situation existed among tailors. The tailor workshops worked on military demands.

When the front got near Siedlce, conditions changed radically. The Russian Cossacks tormented the tailors. They would order garments, but instead of paying, they would take the mended uniforms and beat the tailors and the members of their household with whips.

When the city fell into the hands of the Germans, the situation of the tailors was not better than those of other crafts. The shoemakers were in a bad way. They had lost their workshops, had been put to hard military labor, serving in the hospital or in the prison for two marks a day.

The normal commerce of the city barely existed. But smuggling existed. A number of Jews received their income from smuggling into the city products from the villages. The German rulers fought strongly against smuggling, but quite a number of Jews got their income from smuggling, and some even became rich.

But most of the Jewish population in Siedlce at the time of the German occupation in the First World War lived in need. In order to alleviate the need of the Jewish population in Siedlce, a soup kitchen was opened that fed a thousand people. The “Bri–os” Society

[Page 171]

opened an infirmary for walk–in patients and also paid home visits, treated tubercular children with summer–camps, and the “Ahi'ezer” Society helped the poor population with money and goods. Until the end of the First World War, there was in Siedlce a many–faceted Jewish social life, that took care of the religious, cultural, and social needs. The only official legal government institution–the Jewish Kehillah–was still in the hands of the so–called “dozors.” They based themselves on an older and undemocratic system, a leftover from czarist rule.

Activities of the City's Philanthropic Institution

With the help of the “Joint,” Jewish philanthropic institutions were active during the war in Siedlce. The most notable were “Ezras–Y'somim” and “Moshav–Z'keynim.”

There was a story behind these two organizations.

“Ezras–Y'somim” began its activities in 1906, soon after the pogrom, when organized help for orphans whose parents had been murdered was required. The creators of this organization for orphans were themselves young.

A growing number of young people were taken with warm feelings for the orphans, and so was born the idea of creating an institution that would organize on–going help for these still–living victims of the czarist pogrom. A group of young people took the initiative to create an “Ezras–Y'somim” and took their idea to the Siedlce kehillah, which provided a certain amount of money for the project.

They took a room on Dluga (later First–of–May) Street, number 22. They bought beds, kitchen equipment, while donors provided other necessities. And so the “Ezras–Y'somim” came into being, providing a home for twelve children.

The number of orphans slowly grew.

[Page 172]

The room became too small. The “Ezras–Y'somim” moved to a bigger apartment in the community building.

At the same time, there existed a “Moshav Z'keynim” [a dwelling for older people], that took care of lonely older people. This was a kind of “poorhouse” in a small house. The few old people were cut off, the beds were filthy, and the food that was given to the old people was not suited to them. Jewish women used to bring them a little food so they would have something to eat.

In 1909, R. Ephraim–Fishl Frankel bought a house on Ogradova Street (later Shenkovitsch). In this house, which was originally bought only for the Moshav–Z'keynim, the ground floor was devoted to the “Ezras Y'somim” and the first floor–for the Moshav–Z'keynim. R. A.F. Frankel also put up a beis–medresh on an empty lot that he owned at 14 Kilinski.

This building for “Ezras–Y'somim” and Moshav–Z'keynim solved the problem for only a short time. The administrators of the two institutions quarreled. The Moshav–Z'keynim maintained that the house was bought only for them, and “Ezras–Y'somim was taken in only provisionally, and as the Moshav–Z'keynim grew, its leadership held that the “Ezras Y'somim” should leave. On the other side, the “Ezras–Y'somim” was not comfortable in the small building. In the meantime, the number of orphans grew steadily. The “Ezras–Y'somim” could not dream of leaving the building, because they had no other place.

During the war, “Ezras–Y'somim” really helped the orphans who arrived with the refugees. The number of children grew. The building was too small, but they could not think about enlarging it or about finding another place. Their financial situation was too straitened and both institutions relied on subsidies that they received from the kehillah and from central philanthropic organizations.

Also the Moshav–Z'keynim had to broaden its activities and take in needy old people.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Siedlce, Poland

Siedlce, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 13 Nov 2019 by LA