|

by M. N.

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

In the middle of the market in Radomsk stood a house, which belonged to Reb

Mordekhai Szpira. This house possessed a peculiar emblem on the front wall – a

head of a chimneysweep, with beads on the throat. This was bricked in the

middle of the house, very near the roof.

A verse went around that the emblem was a conspiratorial sign for the Polish rebels of 1863. That the rebels' room is located in the house and there the conspirators' conferences were held.

Mordekhai Szpira was a Jew, a rich man, a Gerer Hasid, a man burdened with thirteen children. He and his wife Hana had a spice shop in the house and later an iron store.

|

| H. D. Nomberg |

When the children had grown little by little, Reb Mordekhai began to look for a

husband for his oldest daughter Mashele, who was then sixteen years old. He

traveled, as was his habit, twice a year on yom-tov to Ger to the rebbes.

Sitting by the rebbes in Ger, Reb Mordekhai asked for a young man as a

husband for his oldest daughter. He was ready to take the son-in-law “oif kest”

(Translator's note: provide room and board) instead of giving a dowry.

After three years, after deliberation, the rebbe gave his advice: in as much as

there is a yeshiva in Radomsk proper, he should turn to the head of the

yeshiva in his name and he would, according to his opinion, make an

effort to find an appropriate young man among his students.

Coming home after the holiday, with a document from the rebbe attesting to his lineage in his pocket, Reb Mordekhai turned to the Radomsker head of the yeshiva, Reb Mendel, with a plea that he choose a young man for him from a good family, chiefly a Talmudic student. The yeshiva head promised to give an answer in about a week. A week later the head of the yeshiva proposed a candidate for son-in-law to Reb Mordekhai – the child prodigy Hersh-Dovid Nomberg, a young man, an orphan (Translator's note: in Yiddish, a child whose father had died is considered an orphan), who came from Amszinow (Mszczonow in Polish).

Reb Mordekhai did not oppose the choice, but he asked the head of the yeshiva to send the young man on the nearest Shabbos, after noon, to an “audition.” At the appointed hour, the young man accompanied by Reb Mendel came to Reb Mordekhai's room. [Reb Mordekhai] had invited to the “audition” every Gerer Hasid with whom he was acquainted. The twenty pages of Gemera, which the young man had learned by heart, made a colossal impression. The “audition'” ended with the general wisdom that the young man has an “open head'” and is, indeed, the prodigy of the yeshiva.

Reb Mordekhai agreed to the choice and proposed to Reb Mendel that he should inform the mother of the young man and discuss the terms of the tanaim (engagement contract), although the groom and the bride did not know each other. Later it was announced and the tanaim was written and the wedding was set for about three months hence.

All of the Gerer Hasidim of the city were invited to the wedding along with the head of the yeshiva and all of the students and many acquaintances and guests. Before the khupe, the bride's mother showed her daughter Mashele her groom and Hersh-Dovid looked at his bride for the first time. The wedding celebration lasted for eight days as was then the custom and took place with great pageantry. After the wedding, Hersh-Dovid returned to studying and spent time together with his friends in the Beis Hamidrish until late into the night.

The three promised years of kest quickly ended. Reb Mordekhai began to think about a business for the young pair, who at that time already had two sons – Moishe and Eliezer. He rented a store for them, together with an apartment – a food store. Hersh-Dovid had to interrupt his studies and remain at home, in order to help his wife serve the customers. For almost a whole day, no one was seen in the store. When a customer did appear, Reb Hersh-Dovid would interrupt his studies and serve the customer with a melody from the Gemera… Very often it happened that Hersh-Dovid would confuse things. Instead of giving what was asked for, he gave another product.

Hersh-Dovid began little by little to abandon his studies and from time to time, began inviting his friends Sz. Y. Epsztajn (Kakeske ) and Abraham-Yakob Tiberg for “sixty-six” (a card game). Guarding himself from his contentious wife, he began to read various “not-permitted” books in the Hebrew and Yiddish language. When Reb Mordekhai learned about Hersh-Dovid's behavior he began to howl: “It denotes – such a heretic!” The moralizing and curses did not help. It was decided to close the store.

Hersh-Dovid traveled to Warsaw and, in order to support himself there, gave

lessons in the Hebrew language. The income from this was negligible and

Hersh-Dovid had to return to Radomsk. He was already then totally different,

not the Hersh-Dovid of before.

[Page 275]

He started to study languages by himself and mastered them in a very short time.

Gradually, he started to write songs, short stories and random stories, which

he sent to the editors of Hebrew newspapers in Warsaw. (Hazman [“The Time”],

Haboker [“The Morning”], and later Hatzfirah [“The Siren”]).

All of the material he sent was recognized by the editors as artistic creations

and were published without revisions.

After a conflict with Reb Mordekhai, who had demanded a get (religious divorce) for his daughter from Hersh-Dovid, he [Hersh-Dovid] decided to leave Radomsk and travel to Warsaw to seek success for the second time. This time he was satisfied, because his songs and short stories were published in the Warsaw newspapers. He turned, as was then the custom of the young Jewish writers, to Y. L. Peretz, of blessed memory, who took him on with open arms and fought with him for beginning to write in Yiddish.

After speaking with Y. L. Peretz, Hersh-Dovid Nomberg was taken in as a permanent contributor to the daily newspaper “Heint” (Today).

In 1909, the editor of “Heint ” delegated H. D. Nomberg to go to America. Before departing, he suddenly came to Radomsk to see Mashele and the children. He boarded in the furnished rooms of Mr. Winter and in the morning sent a messenger to Mashele to inform her that he had come from Warsaw and wanted to meet with her and the children. The meeting took place in Shlomele Epsztajn's home in the presence of the oldest son Moishe. All three sat and were silent. Suddenly, Hersh-Dovid stood up from his place, came to Mashele and proposed to her that she travel with him to America and there get married again. The three children would have to be left temporarily in Radomsk, until he would be settled [in America]. Mashele listened to the proposal and asked to postpone her answer until the next morning.

The next evening, during the second meeting, Mashele rejected the proposal, [giving as] the reason that her father, Reb Mordekhai would not agree to keep the children with him and he would certainly renounce his daughter, if she would travel with the “heretic'” Hersh-Dovid to America.

At his departure, Hersh-Dovid asked that she agree to take a photograph together with the children. She agreed that the photograph would be taken without her, only he with the children. Such a photograph was taken, in Wajnberg's studio* (in the market).

After that encounter, Hersh-Dovid never again visited Radomsk. Reb Mordekhai Szpira took his daughter and her children into his house and took pains to raise them as frume (religious) Jews, in his spirit. When the children had grown up, one by one they left Radomsk and settled down with the assistance of their father in Warsaw.

*Printed in this book on page 65.

During the outbreak of the Second World War, Mashele lived in Radomsk. When the Germans erected the ghetto on Shul Street, Mashele was driven to the ghetto with the large Szpira family.

Later she wound her way out from the ghetto and traveled to Dombrowa-Gurnicza, where her son, Kalman Wohlhendler, from her second husband (He was a ritual slaughterer) lived. She arrived safely, but during the liquidation of this ghetto (1943) she and all of the Jews from Dombrowa-Gurnicza perished.

Of all three sons of H. D. Nomberg, only the oldest Moishe survived. He is now

with his family in Israel.

H. D. Nomberg

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Oy-Vey and Eh, Eh, Eh, Oy, Oy

a.

A hurt in the person's life,

Oy yes! It is so.

He chases good fortune and finds it nearby

And chases and falls, oy, oy!

Eh, eh he chases and runs!

Oy-vey, good fortune runs away!

The time

Passes!

Alone

Remains standing

The man and sees: the head is gray

He asks first: “What is the purpose?”

And laughs with malice: “The end of playing!”

Oy-vey

b.

The world is foolish and corrupt,

Oy yes! It is so.

She had acquired many belongings

And needs – still more, oy, oy!

Eh, eh! The money succeeds!

Oy-vey! The need crushes!

And curses

The world

With blows

And bundles

And thinks hereby we quiet thus:

And we hit the world in the head and turn.

Remains a calm heart! They clearly understand!

Oy-vey and eh, eh, eh, oy, oy!

c.

My daughter is a song of songs.

Oy yes! It is so.

Good luck.

She kisses

Refreshes,

Her gentleness is morning dew,

Then she plays now on another's lap!

They are calm, heart, and scoff at you!

A Travel SongBlack clouds run, chase,

The wind whistles and roars,

Your father sends from Siberia

To you a greeting my child!Only the wind.

He brings us greetings

From the cold land!There it stands, a spade

He holds it in the hand.

And he digs everything deeper, deeper,

Throws the earth out –

Do not worry then!

For a falsehood

He digs out graves.Not the first, not the last

He falls on the field!

Do not worry my child, gave birth to you

Did a great hero.And a hero you will grow to be,

Sleep, sleep now:

Gather strength for the future.

Gather strength for the future,

Gather, only child!

by Zeeva & Dvorah

Translated by Sara Mages

|

| 29 Shevat 5658 (1898) – 8 Heshvan 5709 (1948) |

On the first anniversary of the passing of our townsman, David Kalay (8 Heshvan 5709, a collection in his memory, containing words of remembrance and appreciation for him, and part of his articles and notes ,was published by N. Tversky Publications, Tel Aviv. And so it was said in the introduction to the collection by the publisher: Avraham Levinson.

“During the twenty-nine years of his life in Israel, David Kalay never stopped writing. His many articles scattered across all the workers' newspapers, touch on almost all areas of life in Israel - society, economy, settlement, culture, etc. Some of the articles, which were included in the collection, were found in his estate in manuscript form. Some of them were complete and ready for printing, and some were beginnings, or drafts, for large articles, books or pamphlets. This collection does not include the brochures and pamphlets that David Kalay wrote and published: “The Second Aliyah,” “The First of May,” “How the Histadrut was founded,” and more – and also large articles. The hope of the caretakers of the deceased estate is that, over time, they will be compiled and published over time in a special book.”

The collection contains approximately 400 pages and is divided into eight sections: A) to his image (words of appreciation for him); B) Personalities (22 of his articles, among them about Nahum. Sokolow, Nachmant Syrkin, A. D. Gordon, Berel Katznelson); C) Our Culture - its Problems and institutions (23 articles); D) throughout the labor movement (19 articles); E) on the road to our independence (14 articles); F) In the field of settlement (8 articles); G) Letters (over 20 letters Sent by him to his wife Paula and his daughters Zlila and Zeeva, and also to institutions and personalities, among them - Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Prof. Martin Buber. David Remez, David Shimoni); H) bibliography of his books, translations, and articles (about 200 names).

In the first section of the collection in question, dedicated to his character, the participants (in this order): his daughter Zeeva (Beit HaShita) and his sister Dvorah Carmelit (Gold), Dvora Lachower, Nachum Twerski, Yosef Sprinzak, Shmuel Yavne'eli, Shmuel Dayan, Rachel Katznelson, A. M. Koler, Shimon Kushnir. Avraham Levinson, Y. D. Beit HaLevi, Betzalel Shachar (Schwartz), B. Y. Michaeli, S. Ben-Tzvi, Michael Asaf, Avraham Broides, G. Karsel. A. S. Shtein.

Below we present the words of his daughter Zeeva and his sister Dvorah from the collection.

| The editorial staff |

My father was born on 29 Shevat 5658 (19 June 1898) in Szczekociny Poland. When he was a boy, the family settled in the city of Radomsk, where he spent most of his childhood and adolescence and also started his public work.

A boy like all the boys in the cheder, and he had a beloved and admired eldest brother. This brother of his was already known in the city as a young man who read forbidden books and fell into bad ways… The boy David was completely under the influence of his beloved brother. From him he heard and learned the beginning of things. Under his influence, at the age of 12-13, he found his way into serious and educated libraries and studied and read there in secret. This is he found his way to Mendel Frenkel, on whom he talks in one of his letters (the letter to R' Benjamin), and among others he wrote: “ when I was thirteen years old, I swallowed in his home the book Dor dor ve-dorshav [“A Generation and Its Seekers”], but by then I already had dozens of books from the world of new literature in my cupboard.”

At the age of thirteen my father left to study at the Gerrer Rebbe yeshiva and was accepted into the yeshiva's upper class. He was like one of the family in the rich library of the head of the yeshivah, the Rebbe's brother, and even visited the Rebbe's bibliophile library. He became the yeshiva librarian. During that time, he began writing and also sent his manuscripts to the orthodox newspaper Hapeles [“The Leveler”] of the Rabbi of Poltava. At the same time, he was active in the local youth literary and the cultural association and published in the daily newspaper Der Moment [“The moment”] about the life in the yeshiva and the urban youth. He was expelled from the yeshiva for the sin of writing a critique article.

Father returned to Radomsk, feeling a great need for further education and general knowledge. He began to study on his own for a year and passed exams for five classes of the Russian Polish Gymnasium in Radomsk. During that period, he also tried his hand at translations and translated Gorky's stories and others into Hebrew and Yiddish.

Under the influence of his brother Nachman, and together with him, he took his first steps on the path of cultural-educational work. At the age of seventeen, he became a librarian and regular lecturer at the circles of “Cultura” [culture] society in Radomsk. A year later, he was already among the founding of the Zionist organization in the city, its secretary and librarian. He was also among the founders and instructors of Hashomer [The Guard] society (which preceded Hashomer Hatzair) in the city.

In 1918 he moved to Warsaw. There, he took lessons on psychology and sociology at the institute of Towarzystwo Kursów Naukowych [Society of Scientific Courses], a free university of the greatest Polish scholars who did not participate in the official university run by the German occupier. In Warsaw, he took his place in Jewish society and the Zionist youth. He was among the founders Tzeirei Zion [“Youth of Zion”] in Poland, a member of the first central committee of Tzeirei Zion and a member of its secretariat. He worked in the editorial staff of the party's weekly Bafrayung [“Liberation”], and for half a year in the editorial staff of Ha-Tsfira [“The Morning”]. This made one of his childhood dreams come true. He once told us that when he was a boy, his brother, Nachman, worked for Ha-Tsfira. He was very jealous of him and dreamed of any job in Ha-Tsfira, even a janitorial job, as long as he could walk around the rooms and listen to the adults' conversations... Then, he learned printing, especially typesetting, and saw it as a job that would support him in the future.

At the beginning of the Third Aliyah, in 1920, the circle of close friends seriously considered making aliyah to Israel. Many said and did. My father was also among the immigrants. Sometimes, when we talked, he spoke sadly about his fate that did not make him a simple farmer, a laborer, a real manual laborer, or a printing worker. And indeed, it seems that since his youth he has been active in the field of cultural activity and found his place in it - in its various fields, at different times.

|

| Hashomer society in 1917 |

He continued his cultural activity also in Israel. Immediately in the first few days of his arrival, he began working in editorial staff of the Kuntres [“Booklet”]. He was asked and he answered. He did not work in manual labor in gravel and on the roads like most of the members of the pioneering Third Aliyah, but directly to the editorial staff. He wrote articles for the Kuntres in various pseudonyms. For a certain period of time, he managed the publishing house of Ahdut HaAvoda [“Labor Unity”].

In 1921, the working public moved towards the establishment of the Histadrut [General Federation of Labor]. Father -one of the “new”- was one of the preparers and activists, not an elected delegate - but preparer and organizer - among the founders of the Histadrut. In one of his diaries he wrote:

“I have only been in Israel for six months, from 26 Av and until now. Over time, I got to know many of those born in Israel, and also many from the Diaspora. I haven't studied the country much yet. Apart from Yafo-Tel Aviv, Jerusalem and Petach Tikva in Judea, and Haifa in the Shomron, I have not been anywhere, I also found people with heart and soul. I never left public work. I participated in the preparations for the Haifa conference and joined the activities, then I started to work at the branch of Ahdut HaAvoda in Yafo. I haven't had a moment of discontent during this time. Eretz Yisrael is undoubtedly a necessary place and a fertile ground for the development of the souls of our young people and slandering it is only out of misunderstanding or complete irresponsibility” (26 Shevat 5681/ 4 February 1921).

And more from then: ”Sailing in the country. For two full days – in Nes-Ziona, Be'er Ya'akov, Tzrifin, Rehovot, Yavne and Rishon-LeTzion. Writing about the country is a great thing, and it is a pity for those who do not know it. He who walks the path whose horizon is heaven and earth - it is necessary that the Divine spirit rests on him. Everything around illuminates, warms, encourages, excites, uplifts...” (15 Adar 5681/23 February 1921).

At the beginning of his work in Israel, he felt and felt even more keenly what he already knew: the working public in Israel must be given educational material, so that it may increase its knowledge. Our working public must acquire social education, acquire broad knowledge. This recognition accompanied him in all his actions, during his years of work in Israel. He always said: The most important - sources, foundations. From this perspective, he dared to translate the “Communist Manifesto.” Although he feared that the task might be beyond his ability, the recognition of the necessity of translating the book into Hebrew spurred him on to it, and the work was done, and he was then about twenty-four years old.

[Page 278]

A few years ago a more elaborate edition of the Communist Manifesto was published by HaKibbutz HaMeuhad. But my father has first right to it, the translation of the manifesto twenty-seven years ago, when Hebrew labor literature was almost nonexistent and printing options were slim. That green booklet fulfilled its role in those years, and over time, thousands of workers and youth studied it and, with its help, formed the foundations of their socialist consciousness.

In 5682 (1922), Shechunat Borochov, the first workers' neighborhood near Tel-Aviv, was founded. Father was among its first founders and authors of its bylaws. On 22 Elul 5682 (15 September 1922), he happily informed his brother about his first night in his hut, on his land in Shechunat Borochov and he did not leave to his last day. He was an active participant in it all the years, whether directly as chairman of its general meetings, or behind the scenes. He always followed up on what was happening and gave practical advice on every action. He did not shy away from the most difficult days for the neighborhood, when deviations from the initial pioneering path were evident. Father tried to withstand the onslaught, to prevent the evil as much as possible... The veterans of Shechunat Borochov knew what the neighborhood was for Kalay, and what he was for the neighborhood, so it wore heavy mourning on that day...

In the years 1923-1929, my father was the director of the central library of the General Organization of Workers and the publishing house of the Cultural Committee. From 1925, he edited and published a library on social sciences named after Zeev Barzilai. Here too, the same law served as spiritual authority: imparting fundamentals. Primary educational material. Sources. For this library he translated Ferdinand Lassalle's booklet “The Workers' Program,” wrote “The First of May,” and translates Max Beer's big book, “The General History of Socialism and Social Struggle,” which was published in five-part.

In the years 1923-1929, he acted as a member of the Central Cultural Committee of the Labor Federation. At that time, he wrote the first regulations for the employees of the Cultural Committee (which also included teachers and kindergarten teachers - today the Education Center).

In the years 1929-1939, he edited and published the “society's” books. True to his principle, publishing basic books in social sciences, he translated for this library “England” by Wilhelm Dibelius and “Capitalism & Socialism After the World War” by Bauer.

|

| The high school named after David Kalay in Givatayim |

While working on translation in general, and especially on the translation of Bauer 's book, Father introduced many new words into our language. In order not to overuse foreign terms, get used to innovating and creating words for his own needs. Their number certainly reached many dozen. There are words that were not even absorbed into the spoken language, or more appropriate words were created over time. I am not entirely sure whether Father was the first to use them in this way, although I have reason to believe so. But there are many that are undoubtedly the fruit of his innovations.

In 1927, my father began to dream a daring dream: after his success in translating The Communist Manifesto, he decided to try and translated the book “Das Kapital.” Many questions were piled up before him: Who to translate for? Who will publish the book? Who will bear the costs of the work? If these questions were answered, “Das Kapital.” would have been published in the years 1927-1929. At that time, he was already a patient in the family and was burdened with worries about making a living. He could not take on this responsible job without contacting a serious publishing company that would agree to carry out the project. For a while, he had a glimmer of hope that it would come true, and then he sat down and began the translation, and even managed to translate a considerable portion, but it soon became a disappointment. But he did not give up on the idea and continued to dream of the translation of “Das Kapital.”

When he learned of the desire of “Sifriat Hapoalim” to publish the book, he quickly came to terms with it, but for various reasons, an agreement was not reached in the negotiations, and the book was published in the translation of others. This, of course, caused great sorrow for my father. For more than twenty years, he considered it his duty and life's calling to translate Marx's books into Hebrew, and especially “Das Kapital,” that he invested a lot of work into its translation. And on the other hand, despite his great pain, I doubt if there were many who were as happy as he was with true joy at the appearance of this book in Hebrew. We at home felt the mix of emotions, the joy mixed with sadness, when talked about the book…

In 1930, the cultural committee was disbanded and my father moved to a new field of work. Until now he was active in the fields of the General Organization of Workers, and now he moved to work as the executive editor of “Shtibel Publishing” in Tel-Aviv. He worked at this publishing house for four years

In 1931, he was given the opportunity to realize one of his dreams: to publish a general Hebrew encyclopedia. Here, the desire of “Masada Publishing” united with one of my father's aspirations and his ability. He started working as the editing coordinator, but in fact he was the editor of the “General Encyclopedia, Masada.” My father's private archive contains copies of the speeches given at various parties in honor of the publication of the “General Encyclopedia, Masada,” and the “Encyclopedia for Youth.” In one of them, tin he speech of the author Yacobovitz, who worked with him all the time, it is written:

“Mr. D. Kalay only calls himself “editing coordinator,” a term he invented in Hebrew. However, I can tell you about a secret from the room that Kalay

[Page 279]

is the real editor of the “General Encyclopedia” and also of the “Encyclopedia for Youth.” And I use this opportunity to reprimand him in public for his special humility that made him not to call himself by his true title - - - His greatest virtue as an editor is the feeling of deep responsibility for what he does. This feeling is also what often brings him to depression. There is not a day that a disaster does not happen to him, a tragedy, or a real catastrophe. Every article that did not arrive on time, every photo that did not come out properly, every minor or serious mistake - all these are real personal disasters - days, weeks and months pass in such disasters, and in the end, a new volume is published - a volume of the General or the Encyclopedia for Youth.

My father was full of new plans for an encyclopedia for children before the completion of the sixth volume of the General Encyclopedia. At first the idea was about translation only, but later, as the idea developed - he saw the need for special things for the Israeli children. And so an original plan was created. Indeed - translated sections. Indeed - a lot of learning from the experience of foreign encyclopedias for youth, but mainly - originality. My father was struggling hard with the problem. He sat and studied, studied everything. It was not possible that an article on anatomy, for example, would not be checked for accurate of every detail. He acquired information in areas that were almost foreign to him - all for the purpose of editing the “Encyclopedia for Youth.”

In 1945, my father returned to work for the Histadrut. After Y. Sandbank's death, he started working again in the fields of cultural organizational activity at the Center for Culture

Two years later, with the renewal of the labor movement's archive, the management of the institution was handed to my father. Here he found a wide range of activities.

In the last year all his thoughts were given to the issue of Cyprus. Father knew, and saw, that a vast collection of material of great quantity and quality for the history of the movement and the aliyah was stored there. Material brought by the illegal immigrants from their countries of origin, and material that was created in the island. He saw his role in gathering this material and bringing it to the archive. Its place is only here, in the archives of the Labor Movement. He traveled to Cyprus twice for this purpose only. A special “emissary”: not for a kibbutz movement, not for a political party, not for the Irgun, an emissary for an institution, an emissary almost for himself - for a matter that was not always understood and not always received properly. His trips were not easy - in several respects. But there was a lot of talk about the imminent liquidation of the Cyprus exile -and father feared that all the precious material would be lost - and he traveled, spoke and inspired, acted and was active, and collected a lot of material. Twice, in two journeys, he brought with him boxes full and overflowing with newspapers, letters, photos, works in wood, stone, metal and cloth, certificates, pieces of paper, oral testimonies, historical and nationalist material of great archival value.

He traveled to collect material - and there, while working, he wanted to perpetuate the Cyprus affair, to write a book that will reflect and give a name for all this period, since the deportation of the first ships until the liberation of the last prisoners in Cyprus. He elaborated a plan and began to concentrate on the material and even began to deal with obtaining financial sources (the main inhibiting factor for any big and important plan). He was full of hope that this matter would find many supporters.

Rosh Hashanah 5709 (1948), my parents came to celebrate with us in Beit HaShita. On this holiday we had the opportunity to reach Kibbutz Maoz Haim. Father was very happy about this opportunity. “I have been immersed in work for the past few years, and I cannot go out and travel - I am not at all familiar with the new settlement areas...” We visited Maoz Haim, saw, and received explanations about the kibbutz and the area. Father, in his usual manner, asked and was interested in everything, investigated every detail and listened to answers and explanations.

In that long conversation he also told me about his plans for Cyprus - it was close to his return from there, full of impressions, full of energy and a desire to do something huge for the commemoration of such an event in our history.

We talked a lot about the division in the Labor Movement. This matter bothered him a lot and he always believed in full unification in the near future.

Three precious hours of a slow and pleasant walk, and a long conversation - and I did not know that they were my last together with my father.

- - - I traveled over the year. When we arrived in Eilat, and there were many impressions, I thought: to whom would I tell now? To whom am I writing now about my trip? Who will read and ask questions about every detail about my trips? - As father asked and was interested?

- - - with the liquidation of the camps in Cyprus - how father waited for the day! How he dreamed of traveling, to see and commemorate - but was not able to do so.

- - - the elections to the Knesset and the opening of the Knesset, in the same conversation on the road, we talked a lot about the first elections in the State of Israel, about our first “parliament,” how it would be, what it would be. He expressed speculations and hopes, waited for this day, living these words in his soul.

I go through the huge materials found in cupboards, in bags. Unlimited plans upon plans. Plans for books, for collections, outlines and lists. He had a dream: after both of us, the girls, become independent and no longer need him financially - he will find a way to ensure a modest income for him and our mother, and then - he will retire from his job and devote himself to writing.

During all the years, especially in the last years, during his work in the archive, he collected and recorded, researched and demanded details, and accumulated a lot of material. All the written sections, all the small pieces of paper - everything was the material for the great work he saw before him.

Here is a book, partially written - but not finished: the Histadrut book.

Here are cards, cards arranged alphabetically in boxes. It was supposed to be a lexicon of the Labor Movement. Thousands of entries, many of them are written, many - marked with titles and references - ready for work, for continuation.

Here are chapters of history, chapters that need to be used as a foundation for the great history book of the Labor Movement in Israel in all its parts.

Here is a thick notebook - the last work he started. And during this work, right while writing' death found him: “The anthology of the Third Aliyah in five volumes.” In the notebook hundreds of source scores arranged by subjects - the first work.

[Page 280]

Those - and many more, are just plans. All - work in progress waiting for the desired day when father would stop working outside and finish his work, and that day did not come.

| Zeeva |

With a broken heart and aching soul, I will try to sail with the power of memory to my hometown in Poland. To a period of time that is decades away, to my childhood days in my parents' home, in order to shed some light on the youth of my late brother, David Kalay Gold z”l, and on the home where we grew up together.

Our father, Yakov Mordechai Gold z”l, was considered a Torah genius in his youth and a student of HaRac HaGaon of Omstov [Mstów] (a town near Częstochowa), and there he received ordination to the rabbinate at the age of seventeen. While he was supported by our grandfather, he continued to learn foreign languages and research their books. He was a scholar and ardent Hasid of Sefat Emet [R' Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter] of Ger. Despite his daily worries, there was not a day that he did not study the Gemara, and in our home the sound of Torah was always heard from my father and his eldest son, Nachman z”l.

In this spirit, our parents' youngest son, the adorable and wonderful David, grew up. By the time he was five years old, he was already proficient in the Chumash. Before my eyes live this image: my mother z”l, a noblewoman, took the little boy out of bed every day at five in the morning during the winter, and in awesome respect dressed him in warm clothes. With one hand she led the child, and with the other she held a kettle of hot tea for the “rabbi” the teacher. David, with his bright eyes, fresh and happy, took the wooden lantern he had made, lit the candle in it, and to the sound of a Jewish folk song went out happily to the cheder with her. This is how my mother guided her son to Torah over many winters, until he was twelve. In those days, there was no longer a qualified teacher in our city, Radomsk, to teach him. The boy, David, surpassed his teachers in his knowledge of Torah, and out of necessity, my parents decided to send David to study at the Gerrer Yeshiva.

His age was not revealed there because this yeshiva only accepted students of Bar Mitzvah age. They dressed him in a long new cloak, almost to the floor, took him to Ger and arranged him there in the yeshiva. David was accepted after exams into the second grade (the highest grade there was the first grade), Several months later, they transferred him to the last first grade because the boy amazed all the yeshiva directors and supervisors. Every time my father returned from his visit to Ger, all the family members heard from him, with tears of joy and anxiety, his praises of David the genius.

His period of study, and ideal development, at the Gerrer Yeshiva lasted approximately two years. One day, we were suddenly informed by telegram from the yeshiva that our boy had escaped and gone to the city of Warsaw. Without thinking for a moment, my father and brother Nachman traveled to Ger and Warsaw to search for the boy and find out the reason for the act. It turned out that during a search conducted by the yeshiva supervisors in the student dormitory, there was a handwritten on the subject of “Examining the threads of eruvin,” and along with it, the newspaper Der Moment in which this material was printed (with changes) in the form of a sharp feuilleton against the people of the Gerrer Hasidic dynasty.

The disgrace of the severe punishment that awaited David for his sin - his escape to Warsaw (and indeed we found him then in the bustling city with the help of Mr. Noah Prilotsky). Thus, at the age of fourteen, David began his vocation in writing, which lasted for decades until bitter fate snatched the pen from his hand untimely.

He, of course, did not return to Gerrer Yeshiva. He remained at home and started general studies. He worked hard on his spiritual development day and night, and at the same time, he always sought to teach and delegate the rest of his spirit to others. In this way he reached his first period of public activity. He organized a youth movement (Scouts) in our city and was its counselor. He founded and managed libraries and was among the founders of Tzeirei Zion in our city.

At the end of the First World War, David left his home and birthplace and moved to live in Warsaw, the capital of Poland, which fought at that time for its liberation. In 1920, he found a window of opportunity to make aliyah to Israel.

| Dvorah Carmelit (Gold) |

by Shlomo Tanay

Translated by Sara Mages

|

| 1887-1942 |

Hanina Yosef Koschitzki was born in 1887 in the Polish city Novo-Radomsk, to a family of scholars and Torah lovers. His grandfather, Haim Yechiel, was a Torah scriber and was hired for this work by the Rothschilds in Frankfurt. It is said that he was fired from his work because of a letter that was seized by the Baron and because it had a secular date at the top. He and his sons lived in Germany and on the Polish Russian border of those days, but they did not assimilate among the gentiles and remained observant of tradition and Torah. In his youth, Hanina-Yosef was educated in the city of Katowice in Upper Silesian and was the only member of the large and extended family who glimpsed Western culture.

Hanina Yosef Koschitzki was born in 1887 in the Polish city Novo-Radomsk, to a family of scholars and Torah lovers. His grandfather, Haim Yechiel, was a Torah scriber and was hired for this work by the Rothschilds in Frankfurt. It is said that he was fired from his work because of a letter that was seized by the Baron and because it had a secular date at the top. He and his sons lived in Germany and on the Polish Russian border of those days, but they did not assimilate among the gentiles and remained observant of tradition and Torah. In his youth, Hanina-Yosef was educated in the city of Katowice in Upper Silesian and was the only member of the large and extended family who glimpsed Western culture.

At the age of 19, he married Ester Perel of the Buchner family and established a family in Israel. In adulthood, he became a passionate and active Zionist and ensured that his sons receive a Hebrew and Zionist education, mainly by teaching them the Hebrew language. He himself was a man who loved music and literature. When he met my mother, Ester Perel, he bought her books of classical German literature as gifts, one of the reasons for the “boycott” imposed on him in the family. After his marriage he began learning to play the violin with a klezmer, but his musical achievements only entertained his children on Saturday evening

[Page 281]

after the Havdalah, when he played Goldfaden's songs and other folk songs.

And not only did he learn and read, but he also passed on the love of literature and learning to his sons. He spent a lot of time discussing Torah with his family, at the table, and in any free time. He often engages in biblical discourse with his family, at the table and in any free time. His home was always open to guests. In Bielsko, to which he had moved after the First World War, he turned his house into a center for Zionists and halutzim [pioneers], For years, there were permanent teachers at home who taught the children Hebrew and provided them with a Hebrew education.

In 1929, on the month of November, immediately at the end of the Arab Uprising, just after his eldest son made aliyah to Israel, he liquidated all his businesses in Bielsko and made aliyah to Israel with his family, five sons and three daughters one of whom was married. After the hardships of immigration, the family put down roots in Israel, and over time the family members changed their name, and they are called Tanay.

From time to time he traveled abroad on business, and in 1939, on his last visit to Poland, the Second World War broke out. During the first years of the war, the family maintained a contact with my father and efforts were made to save him and bring him to Israel. These efforts were in vain, and with Italy's entry into the war in 1941, the contact was completely severed. At the end of the war news reached us that my father perished in the great Holocaust.

From people who met with him before he set out on his final journey, we learned that when there was a possibility of escape, he refused for two reasons. He claimed that he was no longer young, and feared that if he died on the way, he would not be buried in a Jewish grave. Secondly, he did not want to leave the community where he lived during the difficult days and, according to him, it needed his help.

The manuscript of the Shemoneh Esrei Prayer, along with various documents, was given to us by a man who survived the Holocaust. He received these writings from my father before he left on his final journey.

May his soul be bound in the bond of life.

The editorial staff's note:

The above article by Shlomo Tanay (Koschitzki), and the following lines from his composition, the Shemoneh Esrei Prayer of Hanina-Yosef Koschitzki z”l, were taken from a booklet written by Shlomo Tanay and published in Tel-Aviv in 5711 (in 200 copies).

The aforementioned booklet includes: Hanina Yosef Koschitzki's prayer in memory of his father; a last blessing to his mother z”l; the (first) Shemoneh Esrei Prayer [“Eighteen Prayer”] in rhymes, that the first letters at the beginning of the lines join to the following names: Hanina-Yosef, Esther-Pearl, Elimelech, Tamar, Ohad, Rani, Avraham, Mary, Shendel, Isaschar-Dov, Ruth, Eliezer, Malka, Rachel, Shlomit, Moshe-Nechemya, Mordechai, Bertha, Danishek, Ashrel, Chaim-Yechiel, and Shlomo-Lipa (names of family members). The second Shemoneh Esrei Prayer, whose sections begin in alphabetical order, is given below.

|

|

by M. H-R

Translated by Sara Mages

|

Prof. Yitzhak Zaks received a traditional education at the home of his father,

the renowned cantor in Radomsk Reb Shlomo Zaks. Already in his youth, he was

revealed to have an exceptional talent for music and singing. He first

conducted the choir at the synagogue in Radomsk and in addition he founded a

music choir, a drama circle that jointly presented small operettas. The Musical

Section in Radomsk headed by Yitzhak Zaks conducted performances and concerts

for the benefit of charitable organizations. Prof. Zaks was also a music

teacher at the Jewish Gymnasium in Radomsk named after L. Wajntraub.

From Radomsk he moved to Częstochowa where he managed the Great Synagogue choir, was a music teacher at the Jewish Gymnasium and participated in the performance of various operettas and conducted choirs.

From Częstochowa he moved to Łódź where he was the conductor of the Philharmonic and active in the cultural life of the Jewish community. He also composed various compositions for operettas that earned him a worldwide reputation as a first-rate conductor and composer. Among others, Prof. Zaks composed a cantata for the poem Mul HaYeshimon [Facing the Wilderness] by Avraham Shlonsky, which was performed by the Philharmonic on 28 October1935. Among the soloists in that concert were the well-known cantor Moshe Koussevitzky and the singer A. Heman and others (the cantata included a choir, a tenor, a baritone and a symphony orchestra).

|

|

The title page of the booklet printed in Łódź in 1935 |

During the Second World War he fled first to Bialystok. There he became the

director of the city radio and also participated in the Moscow Music Festival.

Since his wife (daughter of Reb Haim-Dovid Zandberg from Radomsk) and his

children remained in Poland, he returned to Nazi Germany – to the Warsaw

Ghetto.

Also in Warsaw during the Holocaust, he was active in cultural affairs. His name is mentioned in praise in the Ringelblum Archive for his musical activities during the bitterest days for the ghetto's Jews. He was sent along with the Jews of Warsaw to Treblinka, where he perished.

A. Shlonsky, one of the most original young “Palestinian” poets, gives an impressionistic contrast between old and new Eretz-Yisroel in his poem. We see clearly how the backward and neglected land receives fresh strength and a fervent upbuilding tempo carries itself over the whole area. A musical setting for the poem was created in the form of a cantata by the well-known composer Y. Zaks.

The cantata begins in the middle with an introduction by the orchestra, in an adagio tempo. The introduction reflects life in the country. The mood is monotonous and hopeless. Somewhere the lament of the jackals resounds, but the slowly striding caravans in the desert echo. Monotonous Eastern melodies are heard.

Suddenly the mood is disturbed by new, completely unfamiliar motifs. Ships with pioneers arrive; from the ships a happy “ehe-ehe-leile” is carried from the renewers of the old land.

The description is presented by the tenor in recitative form, and later through the men's and women's chorus. The melody gives way to the march of the camel caravan in the country.

The bass gives the announcement: “The dispersed jackals left for the mountain and the king of the animals gave the order, 'Into the desert!'” The whole land is seized by the new flowering life. A hymn resounds. The chorus sings in moderato tempo, then transforms itself into happy folk singing. Clanging is heard, “dli fe, dli fe,” like the work of building, and, at the end again, the pioneers' song “ehe-ehe-leile.” The finale of the hymn is the recitative: “Thus did the hands knead the mixture of cement and sand.”

The mixed chorus and then the women's chorus of three voices and the bass and tenor sing “Al Breva” and “Allegro.” Dissonance is heard, chaos; a three-quarter fugue resounds, a hurricane… A flood…

The tenor brings calm with his recitative. The work again has the upper hand.

The last number from the cantata illustrates the triumph of the work. A chorus of eight voices and soloists sing in a march tempo the hymn of work and repose.

As we have already announced, this year's concert season of Hazamir is beginning, with the cantata of Y. Zaks' “Mul Hayeshimoon” to a text by A. Shlonsky. This work will take place under the direction of the composer, Monday, the 28th in the Philharmonia Room.

Taking part in the concert: The mixed Hazamir chorus, Lodz Philharmonia Orchestra and the soloists Aziber Kantor, M. Kusewitski, artist from the Warsaw Opera, A. Helman, H. Fefer and others.

| October 5, 1935) |

by Moishe Zandberg

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Yitzhak Zaks was the son of the Radomsker city cantor Reb Solomon Zaks who was

a very talented musician and author of many religious musical productions.

Yitzhak inherited the musical talent from his father and achieved a high level

of musical erudition.

Already in his youth, he distinguished himself in his father's choir, which accompanied the davening in the shul, under the leadership of the director Mr. Gershon Groisberg.

Striving to increase his musical achievements, young Zaks pushed himself to become acquainted with more musical instruments. At the same time, he made an effort to draw in youthful strength in his musical circle, particularly the young, very capable Natan Ofman, who had studied in the Warsaw Conservatory. Together with a great deal of energy, they created a musical circle of young people, who had an inclination toward music, under the name Kultura.

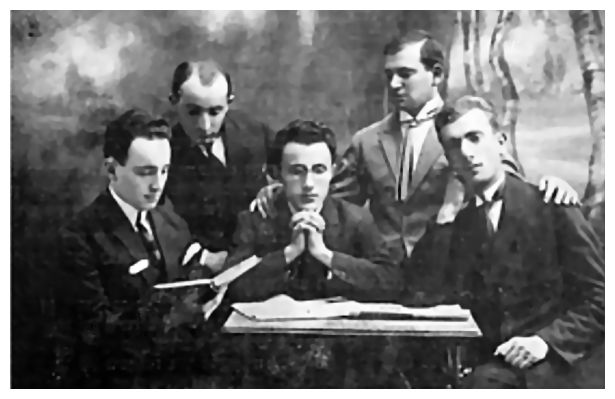

|

| The composer-conductor Yitzhak Zaks (first on the left) and his closet friends

(from the right): Abraham Bugajski, Dovid Fajerman, Berl Bruner, Zisman Epsztajn |

The young Yitzhak Zaks organized a chorus, too, which in a short time, carried out significant

musical productions in public concerts in the city theater. The young conductor

satisfied himself, but not with this. At the end of the First World War, he

already had a dream of creating a Jewish orchestra in Radomsk. As the Austrian

occupation of Radomsk had collapsed, he succeeded in buying up almost the whole

wind-orchestra of the 16th Mountain Troops.

This was not only literally a treasure of first class musical instruments, which made it possible for our musical circle to practice and study, but gave great possibilities to the young gifted musician Mr. Zaks to take advantage of his high qualifications in instrumental music.

After a short education, the orchestra – under the leadership of Mr. Zaks – was already able to give public musical concerts. At the same time, a drama section was created under the leadership of Mr. Adash Horowicz and some times, both cultural institutions appeared together at public events in the city theater, which always were a great spiritual and material success.

In 1919, when the Radomsker Jews could already freely celebrate the Balfour Declaration, the young decided to arrange a public garden entertainment. A large exercise square belonging to the local firemen was located near the city theater, which was also used for public “amusements,” in other words entertainments. After great difficulties, we succeeded in obtaining the square, which was as due decorated. Some blue and white kiosks were set up and at the entrance near the Polish flag, fluttered two blue and white flags, which I myself hung up. The entertainment made a great impression on the local Jewish population, as well as on the Jews from the surrounding towns and shtetlekh, which had sent delegations to the celebration. The friends Natan Ofman and Yitzhak Zaks had furnished sheet music for Yiddish folksongs and other Jewish creations, according to which the firemen's orchestra played during the celebration. For a long time, Jewish Radomsk remembered the beautiful Zionist garden entertainment.

Our musical and drama sections developed more fully and new members joined from the local youth. Public concerts were regularly given, which gave us – Radomsker youth – spirited pleasure. However our happiness did not last long. The Polish population could not accept that the Jews had their own wind orchestra. They requisitioned the instruments from us, with the argument that they belonged to the Austrian army and, therefore, it is war property. Regardless of our interventions, our instruments were never returned to us. Thus, we lost our wind orchestra and its sheet music together with our beautiful young dream.

Mr. Zaks became the conductor of the Częstochowa Synagogue and, later, conductor in the Lodz Synagogue and of Hazamir.

Some of our former members are found in Israel, particularly Mr. Natan Ofman, who sometimes come together in order to remember our Jewish youth in Radomsk.

Let these words be in memory of all of the young friends, some of whom were the

co-founders of the musical and drama sections.

[Page 285]

by Issachar Ben-Abraham

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

In my house (in Haifa) is kept a picture by the painter Natan Szpigel, who

lived for a long time in Radomsk. The picture is 57 by 79 centimeters, painted

on linen and shows a fragment of the old shul in Kus'mir, which

was destroyed by the Nazi-Germans. In the picture one sees a

hand lamp with four candles, several lecterns and a shelf near the wall.

Natan Szpigel painted many interesting images, but two of his paintings made the greatest impression. One image depicted a pair of worn out, burst leather men's shoes. The shoes were painted in such a way that it appeared as one sees the weary feet of an old man, who went around in them for many years to houses collecting donations. The second picture presented a table with tefillin – a shel-yad (phylacteries for the arm) and a shel-rosh (phylacteries for the forehead). When one studied the tefillin, it appeared as if someone had davened with them and soon someone would again come to the table, take the tefillin and put them on the head and on the left arm to daven.

Natan Szpigel belonged to the Realists. He had exhibitions of his pictures in different art galleries in Poland (in Warsaw, Lemberg) and England (London). In our city, he was the first who had a painting exhibition. The exhibition took place in Zhilinske's Polish gymnazie, on Czenstochower Street. There were landscapes, portraits, still-lifes and all of the paintings made a great impression on the visitors, whether Jewish or Christian.

Little by little, Natan Szpigel was drawn into the communal life of the city, often held lectures about art and associated with the young people. He married the eye doctor [in Radomsk], Hana Fort, who was from Galicia. They lived on Strzalkow Street in the villa of the Jewish pharmacist Mientkewicz and had two children – a boy and a girl.

When the Germans entered the city, Natan Szpigel and his wife decided to stay in Radomsk (He had said: “In a war, no one knows when one will die”). A doctor, a Nazi, came to the city and in a few days, Natan Szpigel received an order from city hall – to immediately free the villa for the German doctor. With a heavy heart, Natan Szpigel's family left the villa and moved into the ghetto in Blumsztajn's house, on Strzalkow Street, which was later the Jewish Hospital.

Natan Szpigel worked for a short time in the special commission of the ghetto at the Judenrat. Later, when he saw the growing and hopeless Jewish need, he quietly left the special commission (“My heart,” he said, “becomes sick and hurts seeing how the Jews come requesting help and one cannot help them”).

|

| The painter Natan Szpigel during his picture exhibition in Radomsk |

In spite of this, he would often gather the young in the ghetto, talk and sing Yiddish and Hebrew songs,

so that they would not be so sad.

When the Nazis began to prepare the deportations of the Jews, Natan Szpigel left his son in the Polish hospital on Strzalkow Street and hoped that there the child would be protected. However, on the 9th of October 1942, when the Germans chased the Jews from the ghetto onto the deportation platz, two Polish nurses from the hospital came with the boy and left him on the platz.

|

| The surviving picture by Natan Szpigel |

A Nazi noticed this. He went over to the boy and roared, “Loifen, du Yude”.

The boy began to run from fear; the German shot after him with his gun and

the boy fell down dead. The Nazi laughed, when he saw the child's blood on the

ground.

After the liberation, when I came by foot from Częstochowa to Radomsk, I met Mrs. Keselman in the market. A few days later, I visited her in her home and there saw two pictures by Natan Szpigel. Mrs. Keselman told me that after the liberation when she came back to her home, she noticed on the wall two portraits of German soldiers. She took them down, studied them from the other side and saw it was splattered with blood. She ran [her fingers] over the pictures. She scratched off the portraits and then the real pictures were revealed-- the two images by Natan Szpigel.

Several days later, when Mrs. Keselman's daughter was by chance standing near the pictures, Polish rowdies shot through the window of the residence and the daughter was murdered. One of these pictures, splattered, subsequently [traveled with me] until I came to Israel.

Natan Szpigel, his wife and the second child were deported from the Radomsker

ghetto and did not come back. One of his images, however, came to Israel, the

land of his young dreams.

[Page 286]

by Josef Sandel

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Yakov Cytrinowicz was born in Radomsk in 1893, into the family of a poor

shoemaker. From his youngest years on, he was inspired by the beauty of nature,

but he did not reveal that deep in him there burned a talent for plastic arts.

During the First World War, he was forced to work in a coal mine in Germany, where he took part in the revolution. After many years, he returned to Poland and studied art with Professor Szimanski in Warsaw. There the world-renowned sculptor and “social worker” Nakhum Aronson, of blessed memory, saw Jakov Cytrinowicz's sculptures and praised them. Later Jakov Cytrinowicz came to Paris and at first Bakhum Aronson helped him with “counsel and deed.” In Paris he worked and created many interesting sculptures.

In 1936, the eminent Ukrainian painter Aram Turin wrote about Yakov Cytrinowicz, in “Gszegland Artisticzni ”: “Cytrinowicz goes after simplicity, too. He wins in the fine sculpture 'A Woman in a Long Dress,' but he loses in 'Head of a Girl,' and it a great loss, because in print the head is a very pretty one. The same impression of poverty is felt in the 'Female Body,' with all its virtues and defects of this sculpture, in sum Cytrinowicz is interesting.'

During the Second World War, Yakov Cytrinowicz lived in Paris under Nazi-German occupation. France was divided into two zones: an occupied and an unoccupied. In the summer of 1941, he tried to run away from Paris to the unoccupied zone. Crossing the border he was caught by the Germans; they arrested him and then sent him to a concentration camp from Ban La Roland, there he was spared with a thousand more Jews for almost a year. In June 1942, he was deported to Oswiecim (Auschwitz) to the concentration camp. A month later (July 1942) he died there in the gas chamber.

Honor his memory.(From Josef Sandel's Collection about Yakov Cytrinowicz, in the book “Murdered Jewish Artists in Poland” [Volume two], Warsaw, 1957)

by Melekh Rawicz

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

Born in Radomsk, Poland; 1900-1918 – Vienna; 1937 – Paris; 1961– Settled in Land of Israel (Safet); died the 4th of March 1963.

There are in every cultural environment artistic people who are, because of a

technical accident of nature, themselves not creative. They are filled with

literature, live their lives with literature. Some write themselves, but in

general not, or scarcely anything. They are full of paintings, dream about

paintings, live their lives with paintings. They understand often better than

the artists themselves, but they do not paint. They are friends of poets,

painters, artists in general – and artists befriend them, dying to hear a good

word from them about their writing, about their painting. They are the

connection between the creator and the beneficiary of all kinds of art from the

nine daughters of Zeus. They are the shadows of the artists, but not a large

shadow – they are colorful, clanging shadows, living shadows who can love.

And A. B. Cerata was one of these.

[Page 287]

|

| A. B. Cerata |

I knew him in Vienna – when he was only an assistant typesetter in a Jewish

printing shop, right after the First World War, and later we met many times in

Paris. Of average height, with sharp facial lines, Semitic? No – rather

Hindu-Aryan looking. His face always smiled, sometimes with love, sometimes

ironically, sometimes with anger. Often he could be quiet, often observe

endlessly waiting until it was his turn to speak, to approach a painter face to

face, or writer, whom he liked. And he chose his likes according to his taste.

He was a simple worker, a linotypist, a typesetter. Often he worked at night, but he always had time to visit his artist friend. He did everything for others. However, he was not servile; he did not serve. He did things in the manner of a friend. He helped.

In Paris in 1950, later 1956. In a small hotel, I have a plan today to visit the Louvre.

|

| An invitation to the opening of the A. B. Cerata art gallery in Bet-Yam |

I leave the room, begin to ask how to go to the Museum. Suddenly, a smiling face

appears near me, wearing a French beret on the side of the head – Cerata.

– Come Rawicz, come Ruchel, I will take you. But how did your suddenly appear here?

– I heard yesterday by chance that you want to go to the Louvre.

– And so almost every day, these wonderful shadows have some kind of secret power to multiply your time; perhaps that is why they do not connect with families. The artists are their brothers and sisters and children.

In the difficult first Hitler years in Vienna, when it was necessary to save several Yiddish writers from there, Cerata was already in Paris and did everything to save them. And he actually saved them. No one asked him to do this. Letters in my archive pay witness to Cerata's activities.

In order to do something substantial – Cerata, both in Vienna and in Paris, published a line of Yiddish books. The edition was animated with artistic taste by graphic prints. However, Cerata's life's ideal was to create a graphic print museum, mainly Jewish graphics, and to build it in the Land of Israel. And he achieved the building of this museum in Safet – where the first books by Jews were printed by Jews hundreds of years ago.

Cerata had a peculiar handwriting: long straight letters written with the patience of a bee. His letters looked like lines with miniature picket fences. He would describe an event in detail in his letters (8 to 12 sides). They were small short stories in the first person. In these letters lived Cerata's longing to be a writer himself. Through these letters he transformed his beloved writer in an ingenious way into a reader…

Cerata's last letter lays on my table now; in the letter, he writes an awesome story about a miracle with a little goat, who did not want to let himself be slaughtered. Cerata heard the story in Meron, where he spent Lag b'Omer 5722 (1960-61). The whole story is gold with silver from cabala folklore and marvelously illustrated, the little goat with a sky blue skin…

A. B. Cerata was buried in a cemetery in the cabalist city, Safet. Where then

should such the colorful shadows of many Jewish artists and poets find] eternal

rest? Lived as an artist and died as an artist. I am sure that even in death A.

B. Cerata's face has not lost the loving and ironic smile. I am sure that with

this smile he will appear before G-d and before his beloved painters and

poets, who will wait for him in the eternal arts club…

[Page 288]

by H. Leiwik

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

H. Leiwik, the great Yiddish poet, gave this poem as a gift to the Nowo-Radomsker

landsleit in America. When the poet ran away from Siberia, as a persecuted political

[prisoner], he came to Nowo-Radomsk and found hospitality with contemporary

comrades, A. Alibarde and Zakun Szreiber, who guarded and protected him and

smuggled him over the border on his way to America. This song was published in

the 'Almanac' of the Radomskers in America.

The old-fashioned of the world:

Murder,

Captivity,

Treachery,

Discharge.

Treachery from the closest,

Discharge from the most beloved,

With the back turned away,

With bile on the lips –

Stands the yesterday brother.Thus as it was,

Thus as if nothing had happened

From eternal.And the strongest is after all the person in power,

And the person in power is after all a wicked person,

And the truth is after all with the betrayed,

And not with the betrayer.

And justice is after all the tortured

And not the torturer

Thus as it was,

Thus as if nothing had happened

From eternal.

A dry land on the shoulders

Dirt roads bogged down – through Fifth Avenue,

Frozen lane – between the banks of the Hudson,

Tortured Irkutsk-- through East Broadway,

Shaded yurts – in the snow of Harlem

Through all dirt roads – to the furthest way

Back.

From all truculence to the snow of misery

Back.

All, all, all are driven back.The stronger is after all the person in power,

And the person in power is after all the villain,

And the truth is after all with the beaten,

And not with the beater,

And justice is only with he who is under

Lock,

And not with the guard who bangs with the

Keys.

|

| H. Leiwik in the middle (with his parents), on the way from Siberia to America |

Thus as it was,

Thus as if nothing had happened

From eternal.Old-fashioned talk,

Old-fashioned singing, –

Disgrace, shame

To open the eyes on the streets of New York

And see oneself under the watch of sentries

Being led to the old, to the cold

Old-fashioned, eternal land Siberia,

Eternal land of snow.

March.

March.

March.

Gone bright window panes,

Gone warm bed, –

Le no one accompany,

Let no one console,

And the hand of the most loved

Should lower and fall

And not come opposite.

March.

March.

In heavy linen – the body,

In iron blocks – the feet.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Radomsko, Poland

Radomsko, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 19 Jan 2026 by LA