|

|

|

[Page 269]

by Yitzchak Gilun Zelinsky (Engineer)

[from page 137]

|

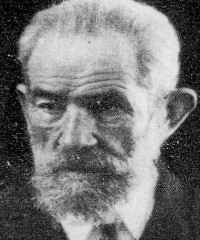

I can't imagine a memorial book dedicated to Pabianice without the mention of one of its most admired personalities, R. Yosef Davidowitz.

During my visits to Pabianice I had the pleasure and honour to be counted as one of his closest friends and to participate in important community activities with him. His personality was blessed by many characteristic traits worthy of mention. He was a family man par excellence, a dedicated volunteer in helping the elderly, and always innovative in his approach to care. He was the graduate of a Yeshivah and a visionary, yet also a man of deep thought, knowledgeable about modern literature and current events. And lastly he was both an aristocrat and a great democrat.

This mix of wonderful traits enabled him to lead many communal activities. There wasn't one centre in Pabianice that he was not connected to, nor a person who didn't know about him; he was fondly known as Yoske Davidowitz.

I met him in 1917, when I came to Pabianice to take up the position of Principal of the Hebrew High School. R. Yosef, who was one of four main leaders in the community, was elected to the Community Committee. Surprisingly, this man, with his traditional attire, at first impressed me as a religious, conservative Jew. But as we continued to discuss matters regarding the establishment of the high school, he showed a great capacity for solving community problems concerning the teaching of Ivrit [Hebrew], and in developing the school curriculum.

When I learned that he had sent both his sons to the Hebrew High Schools in Lodz and Warsaw at the turn of the century, I understood his frustration of not having the same sort of school in Pabianice: religious bias had prevented this till now. I began to understand his ultra–modern views and aspirations for the new school.

R. Yosef Davidowitz was born in 1870 in the village of Dombrova in Kalisz. His father R. Aliyahu Leito, was a well–known timber merchant, a descendant of the Koshmirak family who were landed gentry with many estates in the Kutno area. His mother, Esther (nee Revatzki), was a descendant of one of the Rabbis of Lask, Rabbi Meir Tzilich, who became one of the last emissaries to four different countries during the second half of the eighteenth century.

In 1895, after his wedding, R. Yosef went to live in Lodz to join his brother–in–law, the industrialist Ya'acov Mendel Cohen, who later in Pabianice taught him the art of weaving. It was not long after that R. Yosef became known as a successful businessman and great supporter of Jewish tradesmen in Jewish manufacturing companies.

A number of years before World War I, he and others established the first Jewish co–operatives for the textile factories, the Independent Mechanical Weavers. This organisation helped Jewish weavers to 'break into' the Polish factories even though an embargo had been imposed against them previously. As early as the turn of the century this young industrialist understood that it would be impossible for Jewish tradesmen to succeed without independent Jewish Institutions such as a Jewish bank, Jewish financial institutions and factories.

[Page 270]

With the help of friends he succeeded in setting up the first Jewish bank, which provided mortgages, loans from independent sources, a place for savings and the like.

With the advent of World War I the weaving industry, which was the main source of income for Jews in Pabianice, was greatly diminished due to the German invasion. At the same time, added to these hardships came the news of a British Mandate in Israel and the Balfour Declaration.

Yosef the old Zionist directed pleas for Jewish rights to the German authorities who agreed with the conditions set forward. At the same time, the Jewish Club and Library were established.

His most remarkable actions were his involvement in the Jewish High School and the struggle for Zionist ideological education, which was opposed by the “Agudah” [ultra–Orthodox Jews], by the Germans and later by the Polish authorities.

At the end of World War I he was involved with restoring the social status of needy folk. He established a general food store, a Jewish enterprise called “Consume”, in order to supply the Jewish population with food at very reasonable, affordable prices.

After the war, when flour and other food donations arrived from the U.S.A., sent by expatriates of Pabianice, the major donor, Devorah Kyak, asked for the donations to be distributed specifically by Yosef Davidowitz (Yoske).

I knew of his energy and initiative all the time I dealt with him while I was stationed in Pabianice. At one stage we wanted to set up a Jewish dye workroom, as the dying of threads was handled exclusively by the Polish workers in the huge German–owned factory “Dobzinka”. That particular factory did not employ Jews so it seemed bizarre that we should have supported it.

R. Yosef, in his engineering capacity, erected a great factory called “Fabrikanka” with the blessing of one and all: the industrialists, the “Agudah”, Rabbi Wolf Mendel, and the Ger Chasidim. This factory excelled in its modern, technical machinery, received plenty of work from the Jewish Industrialists and existed for a good few years.

The attitude that R. Yosef had towards his Jewish workers will be demonstrated by the following story:

One of the Christian girls working at the factory wanted to insult a particular person so she took a pair of scissors and put them beside the beard of the delivery man whose name was R. Noah “the pious one”. When R. Yosef heard about this incident he fired her immediately, as he thought that this rotten joke was an abuse of Judaism and of the victim.

This type of incident had precedents, as there was great abuse of Jews with beards in General Heller's Polish army at the time, and also of Jews in general.

No pleading or apologies on the girl's behalf helped and she was dismissed promptly. From that time I understood R. Yosef's principle: “an educator is a holy example”. I also learned to respect and admire a self–respecting man who respected others equally.

[Page 271]

In 1935 he realised his dreams by making Aliyah to Israel, where he settled with his wife Hannah in Tel Aviv and enjoyed the atmosphere of the new homeland. Whilst here he enjoyed spending time with other Pabianice expatriates and toured the land with his wife.

He would be ecstatic, with a joy hard to describe, visiting the old City of Jerusalem, the Kotel [Western/Wailing Wall], or Rachel's Tomb. He would go up to Har Hatzofim to the Hebrew University and stand amazed at the view from its mountain top of the country of the bible.

Maybe fate wasn't with him, as he became ill and had to return to Poland after eighteen months and part with his beloved son and the country. Every letter he wrote afterwards mentioned how he missed Israel and its beautiful blue sky.

The hands of the Nazi criminals put an end to this noble man. With him, his sons and the last of his grandchildren also perished. His memory is engraved in the hearts of his many friends and admirers.

Written by Yitzchak Gilun Zelinsky (Engineer)

[from page 118]

|

The Jewish community of the industrial city Pabianice was led by the most well–to–do people during its one hundred and fifty years of existence, and in that respect did not differ from other cities in Poland.

Prior to Poland's independence the city was under Russian rule and there was a forced assimilation policy for Jews.

It is important to note the role played by Pabianice Jews in the weaving industry, who made a major contribution to workers' unionism and equality. At the same time as, importantly, religious standards were upheld, nevertheless every person's ambition was to become an independent manufacturer (a fabriquant). These qualities typified the Jewish populace who were in old times mainly Ger or Alexandrian Chasidim.

The great ideological revolution only occurred with the advent of World War I and this brought the beginning of a new kind of thinking. During this period, the Jews of Eastern Europe felt that this was the “spring and birth–time” of nationhood.

Everyone had heard about the creation of the Jewish Legion which was formed in Israel to fight against the Turkish occupation. The Balfour Declaration and the decision to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine were great influences in the aspirations of the Jewish psyche at the time.

These matters were instrumental in changing the old regime, and the religious Jewish leadership was replaced by new Zionist leaders, particularly in the Jewish membership on the Pabianice City Council.

The main leaders were:

Yosef Davidowitz,

Chanoch Vigdorowitz,

Ya'acov Vigotzki,

and Leib Adler.

To the credit of those mentioned, new institutions were established and, specifically, their dedication to the education of the young generation led to the establishment of the primary and secondary Jewish schools. These were the first schools of their kind in our city. To achieve this goal, the community leaders liaised with Dr. Mordechai Branda and A. Perlman, responsible for both the Hebrew High School and education in Lodz, regarding the school's curriculum, its framework and educational staff.

After much discussion with Jewish institutions in Poland, I was lucky to be appointed as the first Principal of “The Community Hebrew High School of Pabianice”.

[Page 273]

Despite the fact that I was formerly employed as an industrial chemist, I saw this appointment as a very responsible, community position and it was also an honour to have merited such a place. Without hesitation, I left my former residence in Tomashov and moved to Pabianice with my family. After completion of the educational and administrational arrangements, it was decided to have a formal opening of the school, with many important dignitaries attending including Dr. Branda and Perlman.

The students walked down the streets Warsawska and Bozonizha in their new uniforms, in a street march to the local synagogue in the old town, and after prayers were said the first school year of 1918–19 was begun. One of the first problems to arise was the school building: it was inconceivable that a new one could be built due to the difficult financial circumstances after the First World War. After many searches, a suitable place was found in the large house of Israel'ke Ekstein in Warsawska Street, in an area rather distant from the city centre.

Setting up the curriculum was by no means an easy task and we were assisted by the central educational committees of Warsaw and Lodz. The first teachers were appointed. The first I shall mention is Mr. Gurewitz who taught senior Hebrew: he was a dedicated teacher of Hebrew culture and the Bible. Warterman, a man from Tomashov, was the junior Hebrew teacher, young and enthusiastic with innovative methods of teaching although he was a graduate of an old Yeshiva.

For many years, these men not only taught but also participated in many workshops and discussion groups on Jewish history and literature which they set up for the young people. They also devoted time to teach students who were not part of the school. Warterman and his wife directed many plays and were also great actors in their own right. I shall mention some more teachers from the staff: Wallach taught maths and arithmetic, Sanina Maths II and calculus and Stern taught French. As for the lady teachers, Sanina taught physics and biology, Zalinok, my wife, botany, and Mrs Nireenstein taught Polish and Polish literature. As well, there was a conductor called Drogozinski who taught music and singing and who was helped by the Cantor Yermiyahn Vanderorovnik. Mrs Paster taught arts and crafts and Mr. Viskopp was the physical education instructor.

The main aim of our school was to instil an understanding of Jewish culture, history, the Hebrew language and our ancient and modern literature. We dedicated an eighteen–hour weekly program to Jewish studies. The remaining time was for general studies. We followed the prototype of the Lodz school which was regarded as one of the best in Poland.

It was our core priority to educate our young folk in love of Israel, the Hebrew language, Jewish history and geography and to make of them young Zionists.

One of the hallmarks of this schooling was the blue and white uniform, including a beret which had the Star of David embroidered on it with olive branches on each side. This was our school emblem. Students felt that by wearing the beret they set an example of pride for others and showed pride in their own identity.

[Page 274]

|

|

teacher Wallach , Y. Firenikasz, L. Fogel, Y. Alter 2: H. Szeps, A. Korn, M. Rothberg, K. Weitzmann, D. Yakovovitz, P. Abramson, Y. Lavakovitz, P. Zasharski. 3: S. Fogel, Y. Szynitska, R. Szynitska, A. Reichmann, G. Reichmann, S. Yoskowitz |

Enrolments began to stream into the school from students from the old Jewish School and the non– Jewish school. Those who came from the government schools experienced an agreeable change immediately. The Jewish culture in which they were now included and the love bestowed upon them by their Jewish teachers were very different from what they had previously experienced. In the first year of the school one hundred and fifty students were enrolled. That was the same number as were in grades prep to three at that time. There was, after all, a population of 10,000 Jews in the city. Every year, a new class was added. Notably, the school was not only made up of the children from well–to–do families but for the first time included working–class children. It was the only Jewish high school between Lodz and Kalish, a distance of some eighty kilometres.

As a result, children from Lask, Zdunska–Wola – nearby towns – or even further afield – Praska, Tomashov or Kroshmivitzm – sent their children to our school. It is worth mentioning the large family Shlomo, who were the children of Michael Zloti, who sent their children from Prashka to Pabianice, quite a distance from where they lived. This reminds me of the Hebrew saying: “There is no exile for Torah”, (quoted from the Teaching of Our Forefathers, Chapter 4, Sentence 18).

The establishment of the Hebrew High School symbolised the Jewish national awakening in our city. Here, more than in any other Jewish centre, there was an atmosphere of Judaism par excellence.

Jewish activities were not exclusively conducted inside the school walls but extended to extra– curricular activities such as the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement (most of whose members came from our high school) and the various Jewish union organisations. Our extra–curricular program at school also offered languages, sport, drama, music and singing. The parents of students at our school formed committees for helping to feed the poor, undertaking cultural activities, making costumes for our plays, and making annual trips to various Jewish or Polish historical places of Interest.

Even the Jewish students at the Polish High School and the Jadwiga Girls' College spent most of their recreational time at our programs and activities and also socialised with us.

[Page 275]

|

|

|

|

The high school provided a meeting place for the various youth movements. Many good times were had by the participants, especially during the huge Lag Ba'omer trip to the forest. These excursions included non–Jewish school participants, but they had to participate secretly for fear of being called “traitors”: this was regarded as an unwarranted intrusion by the Polish educators.

The following were the contributors to our educational agenda:

Chairman Dr Yosef Szwarcwasser, (known in Israel as the late Dr Ben Renan) Yehoshua Alter,Chanoch Freiman,

Moshe Fuchs,

Chanoch Reichman,

Alter Grinstein,

Mendel Shiniotzki,

Yosef Shinitski, and Mordechai Chmura.

[Page 276]

The inspectors were Dr. Mordechai Branda and A. Perlman – the principal for the Lodz High School (now an inspector for Israeli schools) – and Dr Arieh Tratkover of the World Zionist Congress (also now in Israel).

|

I was appointed as a municipal councillor representing the Zionists after some time and was able to go back to the high school at times in an advisory capacity. One of my roles was to distribute food parcels equitably to the poor, which were sent from the US by our expatriates. I regard this as the “golden period” in the history of Pabianice.

My many ex–pupils now in Israel, when we meet socially remind me of this wonderful time.

Written by Yosef Zimberknopf

|

R. Jakob Yakubowitz was reared by his grandfather, R. Issachar Dov of blessed memory. His maternal grandfather, the elderly R. Ephraim Rosenthal was one of the respected members of our community. These two influences were the beginning of Jakob's development and of his spirituality.

He was a noted, successful student at the Ger Yeshivah in his youth. Because he was fatherless, he was obliged to go out to work early in his life in order to support his mother and family. Sheindl, his late mother, was very close to him and insisted he never forgot his studies whilst earning a living.

[Page 277]

After his marriage to his school sweetheart, Pearl, the daughter of the Chasid–Kalman Feldman, he joined the Young Ger Chasidim, studying and working conscientiously. His alertness and keen understanding of the issues affecting daily life were already notable in this period. The development of religious Zionism, the socialist Russian revolution, the impacts on Jewish populations during the First World War, the useless loss of Jewish lives in the fighting when both sides had Jews fighting against each other and dying saying; “Shemah Israel”: all these brought up the question, “when shall we return to our own homeland?”

This soon became more of a reality for all concerned and caused Jakob to develop a passion for the Zionist cause and devote a great deal of time to it. As a result of his practical, analytic personality he became heavily involved in Religious Zionism. Despite the fact that the chief Ger Rabbi did not approve of this ideology, he was undeterred and continued working for the cause. And so he found a new path, little by little, and as a first step began to prepare his children to go to Israel.

In 1925, he made Aliyah and was present at the opening of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He went back to Poland but visited Israel very often. Eventually, he transferred all his finances and household goods there and settled in Israel permanently. Firstly, he planted an orchard, then he built houses and became an extraordinary builder, and then he built a large factory as he had expertise in this field from Poland. He not only brought in money, inventiveness and initiative, but was also a pioneer [chalutz] who paved the road that others would follow.

I want to mention now his commitment to the Mizrachi movement. Already in his days in Poland, he was a foundation member of Mizrachi and chairman of the Hebrew Committee. The importance of his work lies in the promotion of Jewish education for young folk from children to young adults. He instilled in them a love for the Torah and a pioneering spirit. All this was done with the aim of preparation for Aliyah to Israel.

One of the apartments in his building served as an Hachshara [preparation for life in Israel] specifically for young religious Zionists. This small, kibbutz–like establishment served as a great prototype for other such places in Poland, in its furnishing and organizational methods. His faithful commitment to the movement was evidenced by the fact that he financed everything himself.

I remember the strike by Polish workers as a result of Jakob's insistence on the employment of Religious Zionist weavers in his factory. The outcome of the strike was that the Poles agreed to keep on the young weavers, who were regarded for the time being as “Zionist students going to Israel”. This was largely a result of Jakob Yakubowitz's political prowess. As a member of the Jewish Bank Committee, he did great things to help the “little man”: very often a loan would be approved by him alone. His young wife, Pearl, was always his spiritual and practical support. Her home was always open to visitors, delegates of the Zionist Federation, and to all charity events and their donors.

It is thanks to his love for Zion and Jerusalem that the main part of their family was saved from the horrific murders suffered by many others, and managed to go and settle in Israel. However, the axe of the murderous usurper did not manage to miss all the members of his family, as their daughters Devorah and Shoshanna and sons Itzchak and Ephraim Fishl were murdered by the Nazis, amongst the other members of the “Vineyard of Israel and its bunches of grapes, its honour and all its glory”. May their Memory Be Blessed and Never Forgotten.

Written by. M. Sh. Gashoori

|

R. Yirmiahu Vandrobnik was our cantor for many years and was born in the city of Szransk (Poland) in 1882. He studied the art of Chazanut [cantorial singing] with his father and in Blashki until the time of his marriage. His father served as a Shochet [spiritual slaughterer] and as the cantor of Blashki. As a young boy, he stood on a chair by the Ark and enchanted the congregation with his marvellous voice. Many senior cantors took him “on loan” so as to secure themselves a good position.

He married in 1904 and lived in Lipna in his father–in–law's house for the first years of his married life. The great and prodigious rabbi of Lipna, named Weingut, certified him as a qualified Shochet. After his father–in–law's passing, he moved to Frankfurt en Mein and worked as a spiritual slaughterer. From there, the family moved to Tushnaad (Hungary) where he received his first appointment as a cantor. This was an honour given to him by the Tushnaad citizens after his sixth month there. Two years later, he was appointed as cantor, without having to undertake any examination, in the synagogue of Dombovar where he spent the next five years.

At his father's request , he was appointed cantor of Pabianice. He would often leave Poland on trips to Budapest where he learned music and cantorism from the professors at the conservatorium. In his own right, he tutored many young cantors, amongst whom was Professor Forgasz who was later the president of the “Stahahl–Weisenbourg Opera”.

R. Yirmiahu was the civil Great Shul's cantor for thirteen years in Pabianice where he also became accomplished in the art of harmony. His specialised qualification was supervised by the great cantor, actor and musician Avraham–Bar Birenbaum, whom he often saw in Lodz. He had many students in Pabianice: one of the first was the excellent cantor–to–be of Amsterdam (Israel), Eliyahn Maroko. He was often invited to the Great Shul of Breslev (the capital of Schlezia in 1914), to relieve the well–known cantor there. In 1914, he was invited to take services in Paris. He declined the invitation due to family priorities. In the same year, he was appointed as municipal cantor of Volotzbak, where he served for fourteen years until his passing and where he won the hearts of those who listened to him.

As a warm and sensitive Jew, R. Yirmiahu saw himself as a “Soldier in the Zionist Camp” in Mizrachi and Oneg Shabbat parties in Volotzbak.

R. Yirmiahu Vandrobnik died in Warsaw at the young age of forty–six and his death shocked everyone. The community of Valotzbak decided to pay for the funeral and take him from Warsaw to Valotzbak for burial. Almost everyone was present at the funeral as a mark of honour to show how well he was loved. They mourned the loss of a devoted, warm, senior cantor, and an ardent Zionist and kind man. He left six daughters and a son. Two of his daughters are living in Israel.

Written by M. Prager (Tel Aviv) [from page 165]

Reb Mendele isn't walking normally but instead he's running; thousands of Jews are marching in a great crowd, the young and old together, women holding infants and babies in their arms and young children holding on to their skirts. The sick and infirm, the blind and crippled are aided by the healthy as the parade continues to move slowly. Everyone is being dragged along by the others, whether or not their feet want to take them, but the rabbi is running.

The guards have satanic smiles on their faces and are not in any hurry. They are merry and making jokes. From time to time they glance at their wristwatches as if savouring every moment of this funny, “never to return”, game. And they laughingly declare: ”Keep your faith now as you won't see another day!”

Meanwhile, R. Mendele speeds up his pace heading towards the head of the crowd. He has spotted a dignified white beard which is flecked by only a few dark hairs, a symbol of the Jewish tragedy which is unfolding.

Suddenly, something is tossed at his feet and a baby wails. Rabbi Mendele picks up the baby and gathers it into his arms as evil laughter is heard. “Ha, ha, ha, Jew! You won't ever have to be in such a rush again.” As the baby's shrieking increases and, panicking, it wraps its arms around the rabbi's neck, he starts to run faster as if to stifle the baby's crying. Now, as he approaches the point in the crowd where he cannot advance further, unexpectedly the rabbi loses energy and feels the blood rushing to his head.

“Fellow Jews,” he says, “can you see what I am holding in my arms? This is the purest being in all humanity: a Jewish baby! And let's have a closer look, dear friends, Satan himself is tearing up this Jack Straw game [infant's game] in front of our very eyes.

“Just as the sun lights up whatever black hole its light falls upon, so the evil and corrupt cannot blot out the sunshine.

“How can this tiny weak babe be of any harm to the murderous and corrupt? The burning of babies will be a process of purification that will thwart the aims of the filthy murderers.

“Dear Jews, believe me when I say that every one of us feels crushed and defiled now, and whilst they were burning Torah Scroll at my place, it felt as if they had destroyed the holy writ of our culture. But they are actually scared of our strength and belief as were all our enemies in the past; they, too, want to break the source of our strength.

“Every one of our enemies throughout the history of the world selects us as the first victims to prey upon. It is a tyrant's first thought, “It's the Jews, or me.” The eternal truth is that the Jewish nation is the centre and the heart of the human body. Our belief in survival, in humanity and in kindness is deeply rooted in our faith in God. There is a saying: “Kindness and Truth meet as a kiss between Justice and Peace.” What feels the coming of the “end of days”? The human heart. What feels the pain in any of the other human organs? Again, the heart. Whenever a flood or tragedy occurs, the heart goes out to it first. So Satan sends his ire straight to the heart of humanity – the Jews.

[Page 280]

“Therefore, I beseech you, dear Jews, do not forget the aim of the war. After all, we are just a link in a chain many generations long. Generations come and go but Satan always wants to eradicate Jews. Is it not written in “Psalms”, “let us separate them and diminish them in all nations and the name of Israel will never be heard of again”?

“Can you recount them all? The Edomites, Moabites, Emalikites, Philistines, Scharikes and the Great Nebuchadnezer, Antiochus and Titus; and all the generations of Latins, Greeks, up to the Turkish Empire, and the Polish anti–Semite Chelemnizki and his descendants. It's a very ancient war, fought down the ages.

“Brothers, let us not be prevented from achieving our final victory. The devil always chooses the physically strongest to be his representatives. But in the end what happens? They always drown and fall to the bottom of the sea [Exodus].

“Evil does not reign for long, as truth is born of this earth and lies have no place to put down roots. None of the regimes of the enemies of Israel has survived and that will include 'may his name be erased from the living' [Hitler].”

Then, R. Mendele lifted the bleeding baby above his shoulders. “This is the end of the eternal battle. The enemy has openly sworn to expunge every last drop of holiness of the Chosen People. As its hatred grows, it becomes more and more bloodthirsty. But here is proof that they will fail: at the moment when our enemy has crushed a whole community, still a tiny baby rocks them profoundly. They are worried that a sole surviving baby will be the final victor.”

R. Mendele had a lot more to say but he lost his will to continue, and a strange sweet lullaby was heard from his mouth and his whole body was affected. He felt as if time was sharpening his thoughts while his fingers and toes were quivering. It was as if he was floating on the wavelets of a river.

While all this was happening, a murderous hand reached out to pluck at his beard. “Ha, ha, you with the nicest beard, you'll lead the way to the final march, on the double!”

Rabbi Mendele was now once again alert and he left the line of marchers declaring:

“Listen brothers, Children of Israel, do you know where we are going? We are going on the ancient road of martyrdom. Just as our forefather Abraham happily undertook the “binding of his son Isaac”, recognize how magnificent this moment is. Children, grandchildren, mothers, fathers and the whole community, all of the pure, are going to be martyred in the eyes of God. We are going together in order to sanctify our Lord.

“But don't be in a rush, fellow Jews, savour the moment: the only crime of which we are accused is that we are Jewish. We shall go on with an absolute feeling of devotion.

“I am willing to give my whole heart and soul – to all of the four kinds of death and to all of the attendant tortures.”

There was complete silence from the great gathering and everyone's eyes were fixed on Rabbi Mendele. He then went on to say, almost nonchalantly, “Whoever shall bring me some water for the 'Blessing of Washing Hands' [Netillat Ya'daim] before my last confession, may inherit half of my entitlement in Heaven.”

Written by Dawid Dawidowitz

[from page 145]

|

The most auspicious figure in our community for many years was Dr Ben Renan (Szwarcwasser). Few of us still alive remember how he came to us in 1915 during the difficult years of the First World War as a young army surgeon, released by the Germans. He helped our glorious industrial establishment from its beginnings.

Before his first two years were over, he had already proven his ability and initiative. The triumph of the Zionists and the foundation of the Hebrew High School were the greatest achievements in which he took part. He was the first to realise that Zionism was a part of modern scientific education. He advocated this and lectured at many pre–electoral meetings, and was a great opponent of Augudat Israel's anti–Israel stance. The Gl'oss Jidowski [Jewish Voice Gazette] included many of his many articles.

Together with his blessed work at the Zionist Federation, he also served as a city councillor, a director of municipal hospitals and as one of the respected doctors at the public clinics.

One of his attributes, only known to his closest friends, was his love for Hebrew, so much so that he might be called a Hebrewphile. He was especially interested in the roots of Hebrew words; we youngsters saw this as just a hobby of his. But he was a young Zionist interested in the language of our forefathers, and he managed to learn it and use it in his speeches to attract his young listeners. He had many other strengths too numerous to mention here.

At this point I'd like to mention his medical and scientific achievements, his life's work. He was involved in the new discoveries in medical science in early twentieth–century Europe, particularly in psychology.

He graduated cum lauda as a doctor in 1908 at the age of 24 in the University of Basel, Switzerland. He was a specialist whose thesis dealt with the investigation of disease of the retina of the eye. Afterwards, he spent a few years studying at the Berlin and Zurich universities. He returned to Lodz where he published his findings on bacterial types, later to be published in the “zentreblatt fir bacteriology” in Berlin (1909–10). He returned to Basel in 1910 where he worked at the University hospital assisting Professor Gerhardt. They published a work called “The Value of Chlorides in the Human Body, from the point of view of Immunization”. This work was translated into Polish in 1911. From 1915–1918, he worked in Pabianice at government hospitals. He went on to a special clinic for “second term pregnancy”.

Specialising again in internal and neurological medicine, he went to live in Israel in 1925. There he was involved in high school clinics, at the Hadassah outpatient clinic and in private practice. In 1929 he was elected as the Director of the Tel Aviv Medical Association. He became editor– in–chief of the popular monthly magazine “Gates of Health”.

[Page 282]

These are some of his publications from Tel Aviv:

1. “Tel Aviv – a healing place”2. “Healing treatments for prolonged tonsillitis by concentrated sunlight radiation”

3. “Thallium Toxicology” (“Medicine” 1931)

4. “Symptoms of epidemic encephalitis” [meningitis] (1931)

5. “A certain prominent symptom of epidemic encephalitis is hearing loss”

6. “The treatment of typhus is eased by Argentinium derivatives” (1931)

7. “Climatic effects on health in the Land of Israel” ('Medicine” 1933)

8. “Designs for developing pharmaceuticals” (1940)

9. “Medical Investigations and tests comparing pharmaceutical products” (1940)

10. “New methods of shock treatment in psychiatry”

11. “Re vitamins as supplements to diet” (1943)

12. “The importance of human well being on immunity and illness”

13. “The physiology of the motor neuron system” (1944)

He continues to serve the public side–by–side with his scientific work. He coined the phrase, “Remind the Anglo–American Alliance of the Importance of the Jewish Problem from a Bio– Historical and a Psychoanalytical Point of View”.

By that he meant, “establish an independent Jewish state!” He also meant that the nations of the world have had a problem in accepting a Jewish state because of their Christian and Islamic religious biases. He believed that a modern democracy in Israel would be an asset to the Middle East as well as to the whole world.

We cannot conclude this portrait of Dr Ben Renan's life without emphasising his scientific and political work. “The Encyclopaedia of Hebrew Vocabulary” contains many findings of his on the source of Hebraic words related to the Indian Peninsula and the Kamaic and Sanskrit roots of these ancient languages. It contains a thousand pages of research. He even saw a parallel between the vocabularies of physics and Hebrew in that both were able to bring out “substance and light” through atoms. This was of great interest to the International Atomic Energy Committee in Geneva in October of 1955. Unfortunately he did not live to see his work honoured as he died before it was published by the committee.

In his notable book “Jews and Jewesses Famous throughout History” (written at the end of the eighteenth century), Alexander Kahut describes Dr Hertz as a person who was loved by the simplest Jews of the German Ghetto area in Berlin. He was valued both for his philanthropic work and as an excellent doctor. They had an old nickname for doctors, “The Angel of Death”, but after years of Dr Hertz's service they changed the name to “The Redeemer of the Dead”.

The new generation in Israel doesn't know of Dr Yosef [Joseph], just as the brothers of the biblical Joseph did not recognise him. But we, who were honoured to know him in Poland, to admire and to be enthused by his devotion to the Zionist cause no less than by his care for the sick, found him to be a supreme and inspiring soul who had descended upon us from above into the Valley of Death, to enliven the Dead Bones.

May His Name Be of Blessed Memory!

|

[Bronia Light, nee Eisman, was born in 1920 in Poland and lived in Pabianice with her family from 1928 to 1942. She was sent to Auschwitz and then to a work camp attached to Bergen–Belsen, and once liberated found she was the only member of her immediate family to survive the war. After the war she came to Australia, married widower Meyer Light and raised a family, one son Jack from Meyer's previous marriage, and a son Ian and daughter Eva of their own. She died in 2012. Her memories of life in Poland, in the war years and after were written in English in 1993 and 1994. What follows is a selection from this record, covering her life in Poland and Pabianice and during the war years. – Eva Light]

My parents, Menachem Mendel Eisman and Chava Miriam Lidzbarski, both had ancestors who for the few centuries of known family history were amongst the learned Jewish families in Poland. My great, great, great grandfather Lidzbarski, as the story goes, was a great entrepreneur – a feller of trees and a builder of roads. He was successful as a 'Talmud Hacham', a philanthropist and very much respected. Sometime in the 18th century he received his name, which derives from the name of

the town – Lid bark – not far from Mlawa. Lidzbarski was thus my mother's maiden name. There was only one family Lidzbarski in Poland, and as I was told early in life, all Lidzbarskis in Prussia, Russia and Poland were kinsmen.

My grandfather was a handsome, quite tall man with a flowing white beard. I was in awe of him, as were my brothers, my parents, uncles, aunts, and cousins. He died when I was seven, at the biblically ripe age of seventy – however his son and five daughters were inconsolable, broken–hearted and full of grief. I remember how he lay in the salon, on the floor, covered with a black cloth, candles around him. His funeral began the stirrings of melancholy in my heart. Melancholy as nostalgia – the yearning for the past.

My father was born in Gur in 1888, and was only 17 when his father died. There is a story of my father being an Alexander Chassid, but at the time the Alexander and Gerer still talked and studied together, so that my father got his 'Smichut Rabbinut' together with the brother of the Rebbe of Gur, Mendel Alter, who was later the rabbi of Pabianice. Later on Mendel Alter's son–in–law did the 'Smichut Rabbinut' with my eldest brother, Moshe. My father's name was also Mendel, Mendel Eisman.

[Page 284]

After he married my mother in 1906 he came into my grandfather Lidzbarski's household in Mlawa. With the help of an uncle he became an agent of tanned leather and did extremely well. Before the beginning of the First World War, in July 1914, my father left for Russia with a transport of leather, which was to be delivered to a merchant in Odessa. He became embroiled in the war and could not return home. My mother, together with my three older brothers Moshe, Abram and the newly born Nachmus, stayed with her father and mother, who at the time occupied one of the largest homes in Mlawa. For three years, from 1914 to 1917, my mother was an 'agunah', a woman who did not know if her husband was still alive. She used to tell us later that only through the love of her parents and her siblings did she emotionally survive those years. My parents were very much in love, though theirs was an arranged marriage. My mother was said to be a real 'Krasavitsa' (beauty, in Russian).

Mlawa was a small town without factories, but the population in general – and the Jewish in particular – were well educated both in Talmud and secular matters. That part of Poland, which was for 150 years under Russian occupation, and only kilometres away from the East Prussian border, was also known as an area of smugglers, and Mlawa and its surrounds had been known as the capital for all sorts of shonky activities – the temptation being the proximity of two large and diverse empires, Prussia having the industrial knowhow, and Russia the agrarian bread basket.

Mlawa had in it a Russian Pension school for young ladies. Thanks to this school, my mother and her sisters received a first class education, learning French and German. They learned to play the piano. Grandfather said he would rather they learn to peel potatoes than play piano. Later in life they did peel potatoes…

My grandparents' house was the scene of many weddings; the succah attached to it was described by a Warsaw cousin, one Berenholz, whose pen name was 'Selim'. A copy of that article, painstakingly written out word for word, was among my mother's many relics, which she kept in a large drawer, and called 'My Nostalgia'. Later, living in Pabianice, she used to open it at times when she was troubled or when she was particularly longing for the bright and happy times she spent in her parents' home, surrounded by love, care, and by her brothers and sisters.

After having spent five years in Russia my father, upon his return to Mlawa in 1919, found his business and home in ruins. He was only 32 years old, a father of three sons and one baby daughter, a Gere Chassid, but a very worldly one. His stay in wartime Russia – where he was twice threatened with death by drowning during the Revolution – was an education to him. Odessa was a port city: the Jews living there were quite sophisticated; mostly they were well versed in Talmud, speaking – as merchants would – several languages. My father, who by the accounts of my mother and relatives was a brilliant scholar, acquired in Odessa a diploma in accounting. In the 1920s, my father built up a very successful business in textiles in Lodz and Pabianice. The Wall Street Crash in 1929 put an end to this business and my father could not get started again until 1935 when keeping accounting books became compulsory in Poland. His Odessa diploma was recognised by the Polish authorities and enabled him to establish a substantial accountancy practice. We were quite well off again. During the dark years of the Depression, we pawned anything that was of value; after 1935 we could redeem all that and our home was beautiful once more.

From the time when my father established his business in the Lodz area, during the 1920s, my mother and I used to travel from Lodz to Pabianice several times a year. I do not remember the beginnings in 1922–24 as I was too little for that, but I do remember seeing early pictures with Mary Pickford. One in particular has stayed vivid in my memory – 'The Girl of Ostend' – this being the place where one of my many cousins was studying engineering.

My parents had a great time during these visits. My mother, though wearing a beautiful wig, was lively and very much in love. I remember her dancing a Foxtrot with my father. She used to play the piano, sing beautifully. All of us in my mother's family have good singing voices. My voice, though

[Page 285]

never as good as my mother's, was burnt out by the very many cigarettes I smoked incessantly from 1946 until 1969, beginning in Paris while waiting to board a ship that was to take us to Australia.

From 1928 to 1942 we lived in Pabianice, near Lodz, where my father had built up a considerable business – initially a textile factory, as well as an office–warehouse in Lodz. His landlord, my mother's brother, was a millionaire and lived in a villa. This landlord–tenant relationship caused many family quarrels.

In Pabianice there were only three Jewish families who lived in villas. The newest and most beautiful was the one that my uncle built during the darkest days of the Depression. During the German occupation this villa became the seat of the Gestapo.

Rabbi Mendel Alter was matchmaker for my brother Moshe, but the marriage, unusually for this time – 1932 – ended in divorce, and my mother, who was a Chassid, helped my brother to get the divorce. She maintained that according to the Jewish law, people should be happy in their marriage. There was a child of this marriage, Frydele. I used to go to Lodz with my brother to visit his daughter. I will never forget how on one of these visits the little girl threw away the beautiful doll that we brought her. I will, I think, forever remember the pain in my brother's eyes. Fortunately, my brother later married a lovely girl, Hinde Stahl, and they had two lovely daughters.

My cousin Chuma came to Pabianice after her parents, three brothers and youngest sister came to live in that town. It was 1934 then and their arrival was a blessing for my mother and for us. Unlike my uncle's, Auntie Sara's household was strictly kosher and we were allowed to mix with Abram, Luzer, Fishel and Rachelke freely. Chuma was a teacher of physical science in the kindergarten. She had a boyfriend in Mlawa whom she adored, but because of a lack of a dowry it was not easy for the two to marry. Chuma used to come to our house for holy days. During the night she would sit up at the sewing machine mending linen, making new curtains or mending old ones. She would change bed linen and cushions, wash and iron it all, rearrange the furniture, clean cupboards, wardrobes, drawers, so that the house looked fresh and beautiful. My mother used to say that little dwarves came and helped Chuma in her spring or autumn cleaning. During one of these visits, she met and married a man whose first name I do not remember; his surname was Sieradzki. He was divorced. Chuma and he had a little daughter, Shulamith, who later was to be killed in Chelmno. Chuma never spoke about her after the liberation, even to me, who witnessed the birth and knew the manner of Shulamith's death.

My brother Moshe, 14 years older than I, was a very learned man in Talmud, as well as in secular subjects. My older brothers had a tutor, a young Polish student who used to come to our house and give the boys lessons in Polish, history, geography, and natural sciences. I remember the exceptionally severe winter on 1929, after the Wall Street crash in October. I did not go to school for some time. At that time my brothers were learning Greek mythology. In later years, when I was in high school, I did particularly well in history – I remembered Greek mythology well.

Four of my brothers were playing well, and took regular lessons from good musicians. Even if there was no money for meat for the everyday main meal, there was, as I can remember, always money for teachers and learning. One of the walls in our dining–cum–sitting–room was filled with five violins and three mandolins. When Nachmus felt reasonably well and when there was enough money to eat and pay rent and other outgoings, there was song, music and laughter. Friday nights of course were the most loved times for all of us. My mother was in a white satin dress, wearing whatever jewellery was at home at the time, a wig, beautifully combed up, with a chignon, looking beautiful. My father, who all week wore modern European clothes, used to put on the long satin 19th–century coat, with a silk 'gartel' at his waist and a so–called Yiddish cap. My five brothers were all in similar Shabbat clothes, Moshe with his beautiful 'peyes' behind his ears. I suppose I too must have looked good. My mother was a very elegant woman and I am sure that she dressed me nicely. As an adolescent I was

[Page 286]

very unwilling to have clothes made, so losing valuable time from homework, literary groups, reading: I was quite difficult. Of my clothes at that time, late 1930s, I remember a long navy taffeta dress, made for a wedding to which the whole family was invited. Soon after this wedding there was a Maccabiah ball, held by the Poale–Zion group. My cousin Hela's son Abramek, who was studying medicine in Grenoble, was home on holidays and wanted very much to take me to the ball but my parents objected.

1933: the height of the financial depression for my family. I finish elementary school. I am the only Jewish girl admitted to the government high school–gymnasium, and allowed to stay away on Saturdays. After two years, in 1935, when Nazism and Jew beating and killing were already rampant in Germany, my parents were informed that unless I attended school on the Sabbath – just attended, not wrote – I would not be allowed to be a pupil of this high school–gymnasium. 'Attending' school was not acceptable to my parents – the headmaster of my elementary Jewish school visited my parents, begging them to allow me to attend school and not to break my 'brilliant career' as a lawyer, writer, scholar, etc. However, my parents would not allow me to attend. I was angry and hurt, thinking I was being deprived of an education and a brilliant future. I did blame my parents, egged on by many of my relatives to resist their decision, to run away from home, to go on studying… After the war began, during the on–going destruction and slaughter of the Jews, I was glad I did not resist my parents' wishes. How would I have felt, even being a university student for a year, having broken my parents' hearts?

1938: I am fully prepared to sit for exams for external Matriculation in Lodz. After Nachmus's death, my mother does not leave the house, does not go out for six months. I, the only daughter, stay home with her…(no exams). Only after the beginning of the war do I hear my mother say, it was good that Nachmus did not live to be beaten to death by a German, since he was not able to work.

1939: the year of the outbreak of the war. Knowing what had happened in Austria and Slovakia, Czech–Bohemia, we felt uneasy. The papers were extolling the might of the Polish army: one clever journalist, Zelenski, wrote, “When the German tanks, which are made of butter, enter Poland, the strong Polish sun will melt them all down.” The Polish government boasted of the might of the Polish army, which had two tanks and almost no armoured trucks; the officers were riding horses and the kitchen and auxiliary personnel were riding in peasant wagons. When the Germans entered Pabianice on September 3rd the noise and might of their Panzer trucks, their tanks and the soldiers marching was incredible. Poland, however, was the only country that withstood the German attack, at Warsaw for 28 days. Paris surrendered: France capitulated mainly to preserve their historic monuments; Belgium, Holland, Denmark were overrun by the Blitzkrieg.

For Rosh Hashanah/Yom Kippur 1939, prayers were held in our apartment; people who lived nearby came to pray. Fear was quite great, because the Germans were on the prowl. People – Jews in particular – were forbidden to assemble. We were continuously harassed in the streets by Germans. In November 1939, my brother Abram, who spent the 28 days of the Warsaw siege at the home of our cousins in Warsaw, married his sweetheart of six years, Sala, at the deathbed of Sala's mother. He immediately left for the Russian zone with his wife, her sister and brother. My mother encouraged him to leave Pabianice. He was a very brave and proud young man, and my mother was terrified at the thought of Abram, when provoked, spitting into a German's face.

During the bombardment we were huddling in the basement of our uncle's villa. After a few days, when we knew the Germans were entrenched in the western part of Poland, except Warsaw, and the eastern part, which was held by the Russians, we ventured out. The Germans started killing the intelligentsia – doctors, lawyers, teachers, as well as industrialists and business leaders, mainly Jews, but not sparing Poles either. There were summary executions. We were so stunned that I do not remember this particular time well. Bread was being distributed at certain posts; Jews were last in the queue no matter how early in the morning they arrived. The Germans, being a mixed race with

[Page 287]

northern and southern Germans looking slightly different, could not distinguish between the Poles and the Jews, but there were quite a few Poles who did this selection for them, and as a result, we used to arrive home empty handed. On one day father came home from an errand with half his beard shaven off. He shaved off the remaining half, but was dreadfully shaken. His spirit was broken, never to fully recover.

By 1940, we had to leave our homes and go to the 'Old City', to the quarter assigned to us. Our landlord, who was an elderly German, offered to keep our crockery, cutlery, a Persian rug and quite a lot of silver dishes. He was truly a very good man. While in the ghetto, which was an 'open' one, for one whole year, my mother used to put on a peasant shawl to cover the yellow Star of David which we were forced to wear, take a bike and ride out to this German man. She used to come home with a goose, a chicken, some provisions, and each time she would say, “That is for the 'fleishig' crockery set”; “that for the Pesach one”; “this for the Persian rug”, and so on. By the end of the first year we, who were not so wealthy, only comfortably off at the outbreak of the war, had nothing more to sell and suffered hunger. We would sell the loaf of bread that was part of our ration to buy a sack of sweet potatoes. When cooked in water only – there was no money to buy sugar, flour or salt – it had no nourishment value, and after a short time one was hungry again. My cousin Mala sometimes used to bring us a bag of flour, sugar or salt, which made for a real feast.

In 1940 my eldest brother Moshe was caught in the street and sent to a camp in Zbaszyn to work on the Autobahn; his wife and their two little girls Faige Nehumele (4) and Rivkele (2) were staying with us at the time. We were lucky to have two rooms in a building that belonged to my uncle. The girls used to pull at my shirt, saying, “Auntie, we are so hungry.” Sometime that year my mother, who was an energetic, industrious and courageous woman, got three of us – myself, Symek and Idus – to clean out a shop in that building. It was a coal seller's shop with soot and grime – impossible to clean, but we managed. We then papered the walls and the ceiling and scrubbed out the floor. My mother sold the last piece of jewellery and bought a small stove, a sack of potatoes, some flour and some oil, and started making potato cakes – an enterprising venture. She started cooking soups, and from then on we were working and not hungry until the liquidation of the Pabianice ghetto.

My father had a complete nervous breakdown at the time – he was a heavy smoker and as there was hardly any money for cigarettes he suffered greatly. Father took great pride in our improved fortunes: the war, deprivation, dislocation and hunger had a terrible effect on him both physically and mentally. A week before the liquidation of the Pabianice ghetto the doctor advised us to take him to hospital where he could get medication – his heart was in a very bad condition at the time. He was shot with other patients – 150 of them – by the Germans, when they entered the Pabianice ghetto. This tragic incident is documented in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, Vol 16, under 'Pabianice'. I often think with pain and not a little remorse about my father's death: had we not put him in hospital, he would have gone to his death in Chelmno, but could have been together with my mother, my nieces, my uncle and aunt and their little grand–daughter. Perhaps this would have been an easier death?

There is also another cause for my many feelings of guilt: when we left the ghetto on liquidation day the Germans ordered us into two groups: one with work cards held aloft, the other without work cards. This way the able and young were separated from the old, the sick, children and babies. Supposedly the young, able people were to go to a working camp and the others to a special caring camp, where they would have better food, better conditions. I do not remember if the Germans told our leaders about it, or if it was just one of the many rumours circulating at the time, but we believed it. When we found out that our dear ones were sent to Chelmno to be gassed we were inconsolable.

My mother, who was a young 53 at the time, was working in one of the workshops, which the Germans ordered us to run. She was a presser of men's shirts and she had a worker's card. A few months before the liquidation of the ghetto I became ill with pleurisy, and in order to look after me

[Page 288]

my mother had to give up her work card. It is still very painful for me to think about it, but as time passes and I think that my parents who were born in 1888 could not have lived until 100, I can stand the pain better.

The hardest and most cruel thoughts are about Symus and Idus, who were younger than I and who I had to outlive.

On the 1st and 2nd of Av 1942, we, the Jews of Pabianice, were ordered to leave our homes, take just a bundle of clothes and food and form two groups: workers and 'idlers' – children and older people. We, the young, were transported to ghetto Lodz (Litzmannstadt), the children and older people to Chelmno, to death…

In Lodz, we stayed for a whole day in the open, the Jewish community trying frantically to allot us places to live, bedding, bed linen, utensils, etc. It was a difficult time for the kehillah, with thousands of Jews were arriving from surrounding small towns as the smaller ghettos were liquidated. Lodz became the workhouse of the district, supplying the Germans with all manner of goods, manufactured in the many 'resorts'. We were given one room at Bzeniask 12, all six of us – Chuma, her brother, her sister Rachelke, my brother Szymek, Idus and I. We stayed in that room together until 1944, when ghetto Lodz was liquidated. The boys worked in different 'resorts', and Chuma, Rachelke and I in Marysin plaiting straw and making boots for the German troops in Russia. Had we known how badly the Germans were faring in 1942, 1943 and 1944 on the battlefields of Russia it may have been easier for us to exist. We did not know how desperately the Germans needed those straw boots in the Russian winter…

I used to get infected fingers all the time and had to have some bone removed from my right thumb. Chuma and I tried to keep our room clean and tidy, the children's clothing and bed linen washed regularly in freezing water in winter, when after work we began housework, often working till dawn. Chuma and I so much wanted to spare the youngsters and create some home atmosphere for them. Rachelke, Chuma's sister, soon became ill with consumption. That illness was raging in the ghetto and, in spite of all our efforts, Rachelke, the youngest of our children, contracted it. In winter, Szymek used to bring in bagfuls of wood chips and we kept the room quite warm with the help of a little iron stove. By that time Chuma and I became permanent workers in soup kitchens. We are forever grateful to the late Szmul Greenbaum, whose wife Rachel was a cousin of Chuma's. Szmul worked in a soup kitchen as a storekeeper and he was able to get us work as potato peelers after our work in Marysin. After a few months of working overtime, there was a so–called 'stitch–tag' and the Department of Soup Kitchens accepted all casual workers as permanent ones. Chuma and I ate our fill in the soup kitchen and then we could divide our meagre rations between the two younger children. Thanks to that, they were not as hungry as others. Szymek did start violin lessons. He was a good violinist and was taught in Pabianice by a very good teacher who found him very talented. I found out later, before the liquidation, that Szymek bought his violin for three weeks of soup, and paid for his two weekly lessons with soups also. That is, soups that were being distributed in the resorts.

When Rachelke became very, very ill, bedridden and began spitting blood, Chuma took me aside one day and said, “You'd better try to get a room for you and the boys. They are young and may contract the illness.” I then had a session with both my brothers and Szymek said: “Rachelke is clever and intelligent, she will understand why we are moving out, besides, I could not possibly supply woodchips for two rooms, and so they will be cold in winter. Above all, if God is willing, we will all survive, but one really does not know who is destined to live and who to die. As it happens, Rachelke came with us to Bergen Belsen, when she died a natural death in 1944, a few weeks before the liberation; Szymek and Idus were killed on the first day of our arrival in Auschwitz in September 1944. Szymek's goodness and selflessness manifested themselves in many ways and culminated in his going with Idus to the left during the Auschwitz selection.

[Page 289]

During one of the Lodz 'shperes' we hid Idus behind a bag with linen. We stood all day long in front of the building, surrounded by Germans holding machine guns, threatening to beat to death anyone who was discovered, and subsequently to machine gun all inhabitants of the block where someone was discovered. I saved Idus. Others – old people and children – were also hidden.

When the time of liquidation of the ghetto arrived, Chuma and I thought of hiding, but we were afraid of being discovered and being forced to see our 'children' tortured and killed. This was the punishment that the Germans had in store for disobedience – and so we went on that fated journey to Auschwitz.

The journey in the cattle truck has been described by many in detail. What can I say? We stood most of the time; there was no room to sit. The few older people and children who were hidden during the selections and were still alive at the liquidation of the ghetto suffered greatly. We tried to help one another, to make room for those who were exhausted. A few died during the journey. We, the younger ones, tried to stroke people, to ease the pain of the sick ones. Much later in Melbourne on a tram I met a woman who told me that she too was in that cattle wagon and that I sang there a few times during the journey. The Germans guarding the wagon kept opening the doors and, keeping them open, asked me to go on singing. And so we in that wagon had some fresh air. I was so shaken hearing that on the tram that I forgot to ask her name. My brothers were still alive then, during that journey, and I would so much have liked to hear a bit more. That journey: when I forbade my brothers to eat too much of the bread and sausage which had been given to us by the Germans when we left the ghetto. This food was supposed to last us for three or four days, and I was terrified lest they would have nothing to eat after having eaten their rations. As it happened, we had to throw the food away on arriving at Auschwitz. Symek and Idus were separated from me, as all the men and women were. At the selection, Symek, being tall for his age and still very strong and extremely handsome – he looked like my mother with big black eyes, beautiful bone structure, dark hair – was sent to the right, to life. Idus, only 14, small for his age, was sent to the left. Symek said in German, “I want to go with my brother,” and was then sent to the left, to the gas chambers. This was related to me by Aronek Freidman, our cousin, who stood together with my brothers but was sent to the right, survived the war and is living in Detroit. After the liberation Aronek did not tell me at first what had happened with the boys. I looked for them all over Germany and also in every possible place where Jews assembled after the liberation. When I asked him why he let me search so long for them, he said, “You were not strong enough to hear that they were killed.” By then I knew how my parents died, how Moshe met his death, and only in the 1960s in Israel was I told that Abram, Sara and their seven–day–old baby were shot at Pinsk by the German Einsatzgruppen. Moshe's wife died in Auschwitz; Moshe's three daughters were gassed at Chelmno in 1942.

Chuma, Rachelke and I were in Auschwitz for three days. When we arrived, we were gathered in a big hall, told to undress and to throw away all our belongings. We were then shaved. A woman from Pabianice, living in Israel, wrote to me that while we were waiting in the queue to be shaved, I put some sugar on her tongue. She asked me, “Does death have to be sweet?” Apparently I said, “Do not talk like that.” We then went into the hall with the showers. We were standing naked in a cold September night; at dawn four SS men came to choose 400 women out of the multitude. They selected the ones who still had some flesh on them. Chuma, Rachelke and I were among the chosen ones; after having worked in the soup kitchen in Lodz we were less emaciated than the thousands and thousands of others. We were given the striped garb of the concentration camp and numbers printed on narrow strips. Our transport did not get tattoos on their arms. There are many explanations for that, one being that we were originally destined for the gas chambers and only some were selected for work.

While we were waiting for a train to arrive, we were spotted by our cousin Mala, who was an 'old' inmate of Auschwitz. In 1942 she had been arrested on a train while smuggling food from Mlawa to the Warsaw ghetto where her parents were. She recognized the three of us and brought us a piece of

[Page 290]

bread, a needle and some thread, a piece of soap and a floral dressing gown. It is difficult to describe her heroism. She ran across the cordon of SS men in order to help her cousins. Mala survived the war and is now living in Haifa with her family. I am forever grateful to her and full of admiration for her bravery: the deadly risk of smuggling food to her beloved parents who died in the Warsaw ghetto and the deadly risk of helping us in Auschwitz.

We were ordered to climb into the cattle wagons and, after having travelled for several days, arrived in the middle of a forest. It is difficult for me to describe the journey, though it was not as bad as the one from the Lodz ghetto to Auschwitz. We were all relatively fit and also young, with the exception of a few middle–aged women who passed the selection. We did not know at the time what had happened to our dearest ones. The young ones (I was already 24 years old at the time) were upset with the loss of our hair, and when we saw others looking like boys we were in despair. We had not yet shed our vanity. The place where we disembarked was called Hambühren–Waldeslust, near Celle in Germany. There was a cement factory in the vicinity, where the 370 women of the camp worked. Thirty of the women were servicing the camp: kitchen personnel, sick room, cleaners for the 150 “Volksdeutsche” Dutch who escaped Holland in 1944, fearing reprisals. As soon as we arrived, the SS officer asked who of us spoke German. Many hands were lifted, as most of the Jews of Lodz learned German as a second language, since the textile mills in Lodz and the surrounding towns were run and owned mainly by Jews and Germans before the Second World War. After asking a few of the women who lifted their hands to say a few words in German, the SS officer asked a German Jewess and myself to step forward. A table was brought, together with two typewriters and boxes of index cards with printed questions. Irma and I sat down and our fellow prisoners formed two queues. They came over to us and we asked them the particulars requested. After we finished indexing, the SS officer asked Irma and myself what work we had done in the Lodz ghetto. I do not remember Irma's reply, but the SS man told her, “You will be the Älteste (head) of the camp.” When I told him that I worked in a soup kitchen in Lodz doing the bookkeeping he said, “You will do the same job here.” He then asked me to choose ten women for the work in the kitchen. I chose Chuma, my other cousin Lola, and one other friend. Chuma chose another few, and the rest somehow came in. This was unbelievable luck for the few chosen ones.

The chef of the kitchen was a Volksdeutsche man from Slovakia. He was a butcher by trade, and told me later on that when he was an apprentice the only master who did not beat him and who gave him enough food was a Jew. We were preparing 400 litres of soup for the camp inmates, 150 meals for the Dutch Volksdeutsche and 50 meals for the SS men who were running the camp. The chef had a mistress, an SS woman, but she was also a decent human being. Both of them tried to help us as much as they could. The chef allowed us to send the leftovers of the 50 good meals to the sickroom, to get 30 women from the camp (different ones each day) to do the preparation: potato peeling, cleaning etc. We gave these women our meals (we eleven had enough food without these meals); they in turn gave their soup to 30 different people daily. As a result, there was less hunger in the camp.

The Kommandant–Lagerführer was a cruel man. After the liberation the British gave the camp inmates four weeks to find their tormentors, and after a trial brought these Germans to justice. I was ill with typhus at the time but was told that this man, our Kommandant, was hanged when found. We had to use all kinds of ways to escape his cruelty. Women used to take the bags from cement to cover their bodies, which were naked under the striped tunics, especially in the harsh winter of

1944/45 in the north of Germany. The winds from the Atlantic were savage – snow turned into ice. We wore wooden clogs that hurt our feet and wounds were common. If anyone was found doing something forbidden, biting on a frozen potato, chewing on something given by a passing person, the whole camp was punished after work, running around the camp square or walking on bent knees. One day a very young girl (who survived and lives in Paris) stole a loaf of bread from the store where the food was kept and ran out through the window. The Kommandant called me, as the storekeeper, and asked me to count the loaves. After I did so, he said to me, “If you don't tell me who the girl is

[Page 291]

who stole the loaf, you will soon be hanging from the tallest tree of the forest.” He grilled me several times on this day. Fortunately one's life had little value at this time, because I really do not know if I could have denied knowledge of the girl's name in different circumstances.

The well–known murderer Kramer was at the time the Kommandant of Bergen–Belsen; he used to come to visit the chef of the Kommandant of our camp and used to have meals in our kitchen. Our friend Anka, who died in 1978 in Melbourne, was an excellent cook and the meals she prepared for the 50 SS men were real 'cordon bleu' banquets. The chef used to leave his radio on so that we could listen to the news. In December the news from the Russian front filtered through the censor and we were happy to hear how critical the situation of Germany was. In January 1945 the chef called me into his office and told me that the camp was being closed and that we were all going to the Belsen camp. He asked me to work with him in the soup kitchen in Belsen, so that he would not have to worry about getting someone else to run the storeroom and to look after the books. Knowing that he was a good man, I dared to say that unless all of the kitchen staff could go, I would not be going. This was only partly altruistic, because although one could have a good position in the camps, there was no certainty or safety because the changes were constant; however, without one's family or friends it was impossible to cope. To my happy astonishment, he asked me to make a list of the eleven women.

We arrived in the hell that was Bergen–Belsen. To quote Dr Giselle Pearl (from I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz, pp. 157–160): “Let no one speak to me of German culture, German civilization: Bergen– Belsen was the faithful portrait of German civilization; Bergen–Belsen mirrored the German soul.” There were no bunks in Belsen, except for the people who worked. We were lying in a block among the dying and the dead, among skeleton–like women in dirt and excrement. I remember a Hungarian woman whom I embraced on the floor and took into my arms; after a little time she died on top of me, kissing me and thanking me in Yiddish. It is impossible for me to describe this nightmare – but we eleven women from Waldeslust were lucky as on the fourth day a girl arrived in our block with the list that I had written out and given to the chef. She took us out of the dirt and stench, marched us to a shower block, where we were given clothes and taken to the soup kitchen where the chef greeted us with a smile in his eyes. In the evening we walked three kilometres to a block that had bunks – no blankets – bare bunks but what a luxury!

The kitchen in which we worked was preparing 15,000 litres of soup each day – it was a vast building which housed the store with provisions, four large vats, a store room, and a large room with troughs around it and over them taps with cold water. There we were 150 women – peeling potatoes, carrots, cutting cabbage, carrying it all and emptying the raw vegetables into the vats, adding water, salt, pepper, paprika and thin slices of bacon. Dr Klein, who at the time was camp commander, used to come in to taste the soup and invariably would say to me, since I was in charge of the books and provisions, “More pepper, more paprika.” One day I fearlessly said to him, “There is no water in the camp, the people will die of thirst.” He looked at me angrily and walked out. For a few days I was expecting to face the firing squad. Dr Klein was sentenced to death at the Nuremberg trials. After a few weeks, sometime in February, Kramer came into our kitchen, complaining of the wasted vegetables that were piled upon the ground around the kitchen block. After he left, I asked the chef to allow me to get 100 more women from the camp to help with the peeling and washing of the vegetables so as to be able to have a thicker, more substantial soup and to avoid wastage. He allowed me to prepare a list. I went around and asked each one of the 150 women if they had a relative or friend in the huts. I put the names down and the chef asked me to get these 100 women. Getting them into the kitchen was an inspiration and saved many of them from terrible beatings. Almost each one of them was smuggling out food for their dearest ones; at the gates, which we passed each day, there was a control, and almost everyone who had food hidden, fastened on their bodies, was beaten mercilessly. Chuma was one of the most brave. She was fearless and went on smuggling food out in spite of the beatings. Having the 100 extra women in the kitchen, where they could eat their fill, was a good decision.

[Page 292]

The chef was a truly good man, especially having seen the SS men who ruled the camp, their swastikas and cruelty. An incident with Kramer illustrates his attitude to the unfortunate inmates. Kramer came in one day and complained about prisoners stealing vegetables. The chef replied: “I have here in the kitchen 250 women whom I have to supervise; I can't go out and prevent the prisoners from taking vegetables, which are freezing and rotting. Let them eat.” After a week he was transferred to the Russian front. Chuma, who used to bake biscuits for him, set out to bake kilograms of these biscuits. We were very upset for the chef, for the Russian front was like a death sentence. We also feared his assistant, who was a vile–looking man, a six–footer, who inspired fear in us all. We somehow managed and kept on helping as much as we could. We were glad to hear after the war that the chef had survived and returned to his village. He had a mistress in Belsen – a very gentle, beautiful girl, who used to put out buckets of cooked potatoes for prisoners in another camp in the vicinity of Belsen. We wanted to write to him, but she would not give us his address in Slovakia, either for fear that someone might denounce him or for fear that we might write to his wife about her – the mistress.

The lack of water in Belsen was especially hard on the victims of typhus, which was raging in the camp. The people in the hospital, weak with fever, were suffering greatly. One day I asked our 'colossus' to allow us to carry large cans of coffee on our way to the camp at night. To my astonishment he allowed us to carry as many cans as we could. We prepared and took them, and each pair carried the cans for a certain distance – the camp was 3 kilometres away from the working area so we changed hands several times. We kitchen staff were strong – we were fortunate, we did not suffer hunger. When I think of it now I feel very humble and often think that I personally have no story – only my losses, my parents, my brothers, their wives and children are my story, my pain and grief. We in the kitchen were spared, even as far as seeing the horror that was Belsen… We would come to the kitchen at 4 o'clock in the morning, in a northern European winter, dark and cold, dressed in prison garb at first, then we got some dresses, no underwear, hardly any shoes, wooden clogs mostly. We washed before we left our block. It was cold lying on the bare bunks, but we were lucky: after the brisk march we reached the kitchen, we were under a roof, we could work all day under cover, not being hungry. When we walked back in the evening, it was dark again, so we saw little of the columns of skeletons arriving constantly from the death marches, we saw little of the mountains of corpses and dying people thrown alive on the heaps – corpses and bodies still moving, mixed with filth and excrement – we saw little of the mountains of spectacles, shoes and toys…