|

(Blacharska 19)

|

|

[Pages 119-120]

Translated by Myra Yael Ecker

Edited by Ingrid Rockberger

| The reign of King Michał Wiśniowiecki. The dispute with the Christian shoemakers' guilds. The Jewish Trade. dr. Emmanuel de–Jonah. The struggle with the townspeople. The community's financial situation and debts. The Rabbinate under “Sage Cwi [Tzvi]” and his opponents. The rabbis and Shabbatai Zewi's followers. The trial of the Reizes brothers. The students' onslaught. Polemics of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz and Rabbi Jakób Emden. |

Michał Wiśniowiecki [Michael I], who had succeeded in beating Khmelnytsky's forces, pursued a policy of tolerance towards the Jews of Lwów. Soon after he was crowned he granted the community leaders' wishes by allowing the Jews to keep stockrooms in their homes.[1]

Due to that, a dispute with the Polish and Ruthenian Shoemakers' Guild broke out under him.

In 1670, contrary to the royal provision, the Starosta (governor) Stanislaw Mniszek placed the Jews under his own jurisdiction and allowed unqualified craftsmen to undertake their work. He also granted them the right to reside within the nobles' jurisdictions, while forbidding the municipality from harming them. There were also Jews among these unqualified craftsmen. The governor permitted the Jews to settle below the urban castle, to sell liquor and ale and even to establish breweries and beeswax workshops. In 1673, under pressure from the Shoemakers' Guild, a royal verdict was passed to which the Starosta yielded.[2]

The Cossacks who were discontent that Wiśniowiecki had been crowned, succeeded in inciting the Turks to invade Poland. Their demand was that Poland give up the Ukraine region. On the 29th August 1672, they conquered Kamieniec–Podolski [Kamianets–Podilskyi] and from there they set out for Lwów. The municipality requested military assistance from the King. Jan Sobieski, the minister of the armed forces who came to Lwów, was able to defend the town with a limited number of infantry and cavalry men.

Following the King's order, women, the elderly and children left the town while jewellery and valuables were concealed. Those who fled included the rabbis, Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsz (within the town) and Rabbi Juda Judel (outside the town). The one thousand men left in the town were mobilised, including Jews. The Jewish population of Lwów, like that of Rzeszow [Reisha], Przemyśl, Trembowla, Buczacz [Buchach], Tarnopol and Czortkow, was obliged to defend the town together with the Christians. For that purpose they were equipped with riffles and gunpowder, and at times even cannons. To protect the town, the suburbs were burnt down, destroying Jewish property. When the Turks approached the town they demanded its surrender. The municipality refused their demand and sent presents to the Turkish commander, Kapudan–Pasha. He refused the gifts and attacked the town with firearms from the 23rd to the 28th September 1672. As the siege debilitated the town, the King's emissary arrived carrying the order to negotiate with the Turks and to pay them ransom. The Turks demanded 100,000 red Gulden, a sum the townspeople were unable to raise, all they managed to collected with much difficulty was 5,000 Gulden. Once the Turks realized that they could not collect the entire ransom fee, they agreed to accept the 5,000 Gulden collected, in addition to 12 men of mixed–race, which included two Jews. Men who returned home only seven years later.

After the Turks retreated the Jews were in straightened circumstances. Poverty prevailed throughout the Jewish Quarter, and the refugees from the suburbs who feared to return home, preferred instead to wander through the overcrowded Jewish street in town. The community already laden with debts from the ransom payments imposed on it, was in addition obliged to pay a hefty interest and assist the refugees.

The nobles who had fled the town before the siege, and whose houses and castles in the suburbs were burnt down as a result of the war, were compensated after their return, following a law–court's decision. The Jews of the suburbs who had suffered destruction, were however given no compensation. The nobles understood the Jews' predicament and demanded that the “Sejmik” at Wisznia [Vyshnia], release the Jews of the suburbs, whose houses had been burnt down or destroyed for the protection of the town, from the payment of taxes. They also demanded the return of the mixed–race prisoners taken by the Turks. The townspeople, however, took no heed of the Jews' circumstance.

Despite their common war predicament, the townsperson hated the Jew, viewing him as an economic rival. All the townspeople wished for was to remove the Jews from the town, even by expulsion, especially when they saw the swift recovery of the Jewish trade after the war. But as the townspeople had no authority to expel the Jews, the traders and craftsmen settled for limiting the trade and crafts available to them.

[Pages 121-122]

New negotiations for a mutual agreement started, based on the earlier agreements. In 1676, the municipality decided that only a Jew who owned property or real estate be permitted to trade. Traders dealing in imported goods from abroad, or in fabrics, were obliged to prove that they owned at least 5,000 Gulden of assets. Petty trading required 3,000 Gulden; liquor trade required 6,000 Gulden and for ordinary wine and mead 3,000 Gulden were required. For beer brewers and liquor distillers 1,500 Gulden of assets were sufficient.

Consequently, Jews started to purchase plots of land – which benefited the townspeople who were in economic straits. Nevertheless, the townspeople continued to persecute the Jews. Influenced by them, the Sejm of 1676 decided that the Jews of Lwów be only permitted to trade in goods included in the agreement with the town council. As to the debts of the Jewish citizens, the Sejm ruled that in accordance with an ancient custom the Jews were obliged “To assist with the cannons situated on Lwów's town–walls”.

Jan Sobieski [John III], the heir of King Wiśniowiecki who died at Lwów on the 10th November 1673, appreciated the economic role played by the Jews. In his youth he knew the Jews of Żółkiew [Żółkiew], where he grew up, and recognized their importance to the state's economy. That led to his leniency with the Jewish population and his help in improving their circumstances. His court at Żółkiew included a large number of Jews, and he particularly trusted in his administrator and customs officer Jakób Bezalel [Becal] ben Natan, who settled at Żółkiew in 1685, and managed the customs office at Lwów.[3] His treatment of them was a cause for incitement against the Jews.

The municipality and the townspeople complained of the King's contempt for the Christians, and the magistrate at Warsaw commiserated with the Lwów municipality, lamenting that things had gone so far in Poland that “the Royal Customs was given to a Jew who oppresses and suppresses Lwów traders, an unthinkable situation in Warsaw.”[4]

Jan Sobieski's court physician, Doctor Simche Menachem Emanuel, the son of doctor Jochanan Baruch de–Jonah,[5] was an exceptional man. His father had settled as a doctor at Lwów. His mother Eksa, who died in 1666, was the daughter of Doctor Menachem Zunsfurt of Lwów. His brother, Eliasza [Elieser], who died in 1672, was also a specialist doctor at Lwów. In 1678, his brother Jakob qualified at Padua as a medical doctor, together with his friend Levy Liberman–Fortis, of Lwów, and his brother Doctor Izak Fortis; his brother Józef was a merchant at Lwów and died in 1712. Their father, one of Lwów's community dignitaries, a great sage who closely followed the Torah and its commandments, died in June 1669.

The physician Simche Menachem de–Jonah married Nessia, the daughter of Reb. Pesach, and a short while after practicing at Lwów his renown as a doctor spread throughout the region. Besides his medical practice he also dedicated time to community affairs during the years of suffering following 1648.

|

|

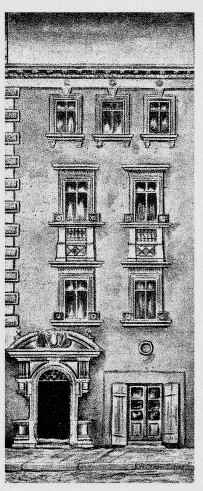

| The house of Dr. Simche Menachem (Blacharska 19) |

In 1670–1671 when King Sobieski fell seriously ill, he invited him [de–Jonah] to treat him and demanded he reside near him at Żółkiew. He remained there till the King died in 1696, after which he returned to Lwów. Here he built himself a magnificent house on the Jewish Street (number 19), and was respected by the community. Still during King Sobieski's lifetime he was “President of Eretz Israel”, and in 1698, he was elected community leader by the Council of Four Lands. In this function he settled important issues, such as the dispute between the printer Uri ben Aron Feibish HaLevy who had moved a publishing house from Amsterdam to

[Pages 123-124]

Żółkiew in 1690, and the printers of Lublin and Kraków.[6] He also settled the dispute within the community of Żółkiew (1701). “Reb. Simche Doctor” – as he was known by the people – was accepted by all classes of society, both Jews and Christians. He was very learned in the Torah, educated and an art lover, as seen from the Renaissance building he built as his home. He was much appreciated for the generosity with which he assisted the poor and the wretched.

His first wife, Nessia, died in 1693. In 1696, after returning to Lwów from Żółkiew, he remarried but only lived a few more years. He died in March 1702.

King Sobieski was accepted by the Jews who considered him their patron, and legends circulated of his deeds and benevolence. One such tale recounted how during his reign Christians accused the Jews of Lwów, of blood–libel. At the time, Sobieski resided at Lwów and one night he stepped onto the balcony of his house and saw several Christians running away, one with a sack over his shoulder. The King ordered to stop the men, and the body of a Christian child was found in the sack. He instantly gave an order to punish the villains and to publish the facts in order to remove all suspicion from the Jews.

In February 1695, the Tatars invaded Reissen and arrived at Lwów. The Polish commander, Jabłonowski, was forced to retreat and to evacuate the Krakowite suburb. The Tatars then attacked the Jewish Quarter, killed most of its inhabitants, demolished and looted the houses. They retreated only after the onslaught by the Polish army.[7]

After the death of King Sobieski (1696), a new wave of wars erupted. The Swedes supported the candidacy of Stanislaw Leszczynski as king of Poland, and the Russians sided with August [Frederick Augustus II] of Saxony. Mercenaries attacked Lwów and the town was obliged to pay ransom.

On the 23rd November 1703 a gun–powder store exploded in the Jewish Quarter (Boimów). Many buildings were destroyed and 36 Jews were killed. Among them was the messenger [HaMagid] Reb. Szmerl Katz,[8] the leader, Reb. Naftali Hersz son of Reb. Jechiel Rubel, the rabbinical judge [dayan], Reb. Aszer ben Reb. Ruben.[9] Hardly had the Jews recovered before they faced a new calamity. In 1704, the Swedes attacked and on the 6th September they occupied the town. The suburbs and their Jewish citizens were again the first to suffer, and the community outside the town was totally destroyed. Refugees from the suburbs fled to the Jewish Quarter within the town, crowding the streets. According to the chronicler Chodynicki,[10] the Jews participated very actively in the defence of the town. One Jew was killed while firing a cannon at the enemy. The Swedes, angered by the Jews who participated in the defence, decided to take revenge on them. When they entered the town, they rampaged through it, killed, and robbed private houses, churches and synagogues.

When the Swedish army left town only one garrison remained, led by General Stenbock. The Jews paid their share[11] of the ransom in addition to munus judaicum (present from the Jews) in the sum of 20,000 Thaler.

Suddenly a fire broke out, destroying the town's warehouses and the street of the Jews. Despite the calamity, General Stenbock demanded the “present from the Jews” payment. When they declared that they were unable to raise such a sum, he placed a hanging–tree in front of the synagogue and threatened the community leaders with hanging, were the tax not paid. Under those threats, the money was collected.

With Stanislaw Leszczynski's intervention, King Karl XII of Sweden agreed that the town of Lwów would pay just 132,000 Thaler, of which the Jews paid 40,000 Thaler.

The Jews of Lwów suffered greatly, their financial standing declined drastically even after the withdrawal of the Swedes, while expropriations and war–tax payments were still ongoing. In the years 1705–1711 the Jews were obliged to give their fair share of the 308,894 Gulden levied by the Swedes, since the nobles and the clergy counted on privileges and refused to partake in that payment. In addition, in 1709 the town paid 150,000 Prussian Thaler to Leszczynski, the Swedes' ally.

To make those payments which amounted to hundreds of thousands of Gulden, the community was obliged to borrow vast sums from Jew,[12] noblemen and monasteries.

The municipality brought legal actions against those Jews who failed to meet the obligation imposed on them in accordance with the 1683 contract which was extended to 1691. The trials continued for 40 years and there was no change in their circumstances till 1773. In 1709, all the “Classes and Nations” in town agreed a rule forbidding Christians from letting any accommodation or shops to Jews. The rule was confirmed by August II in an addendum of the 11th April 1710, noting that anyone transgressing the rule would be fined 200–500 Gulden. The Jews were not surprised and managed to obtain a suspension to vacating the houses from the town's commander, Jaspres. The municipality, however, obtained an instruction from the King that Jaspres had no say in the town's affairs.

The dispute escalated further: the municipality had reached a verdict obliging the Jews to sign a new contract within a fortnight, otherwise they would lose their rights and their trade would diminish; they would be forbidden from owning taverns

[Pages 125-126]

and bars, and they would have to vacate the flats, stores and shops in Christians' houses.

The Jews of the suburbs were forbidden all trade and employment. After they appealed, the royal law–court at Warsaw decided, on the 14th February 1713, that the Jews had no right to sign any contract with the town; that their trade be restricted to four types, and that all their other merchandise be confiscated. Special commissaries were sent out to execute that verdict.

In 1732 (8th March), the municipality received a judgement permitting it to expel the Jews from all the streets and suburbs, other than the Street of the Jews. But the Jews managed to evade and prevent the execution of those judgments, with bribes and through connections. The Nobles backed the Jews and leased them their houses and plots of land, especially in the suburbs, and that due to the high rents they received from them.

The townspeople were embittered as the number of Jewish shops increased, and in 1738, 71 shops outside the Jewish Quarter were declared illegal. They obtained an order from the King handing the settlement of the dispute to a special committee, and after negotiations on the 21st July 1740, an agreement was signed between the Jews and the municipality in which the Jews pledged to follow their trades according to the 1592 contract. However, as the contract did not mention specifically that the Jews had to vacate their shops in town, they did not do so.

The Jews were also on trial against the Jesuits about a brewery they had leased from them. The 1611 contract between the Jews and the Jesuits was altered in 1722. Instead of pepper and saffron with which the Jews had previously paid the Jesuits, they now committed themselves to supply at each holiday: four turbots or carps, three pounds of oil from Danzig [Gdansk], three pounds of ginger, three pounds of pepper, one quarter of a fat calf and one Thaler, besides presents for the students: a container of liquor and a sum of money, quarterly. They supplied the Voivode's priest with four roasts for each and every holiday, and four jars for every new rector. All other taxes were eliminated.

Vast sums of money were required to cover the costs of, and the bribes associated with the trials, resulting in a heavy financial burden on the Jewish citizens.

The standing of the town declined, many of its houses stood vacant and even the Christians themselves let taverns to Jews. The Christians had 67 beer taverns in the town, some of which they let to Jews; the Christians had 71 plum brandy taverns, and the Jews had 31. Of the liquor taverns, 80 were managed by Christians and 16 by Jews. In the suburb there were 57 taverns, all in the hands of Jews. The number of taverns in the hands of Christians decreased further after the war with Sweden.

From every aspect, the condition of the Jews was difficult. There were 49 plots of land in the Jewish Quarter within the town, and after the war at the beginning of the eighteenth century, with the increased number of refugees who fled from the villages, it was impossible to house all the Jews within the Quarter. Consequently, they were forced to rent accommodation outside the Quarter in the adjacent streets (Ruska, Szkockiej [Scottish], Serbska, Boimów). Their shops were scattered all over town, including in Rynek 10, where, in the King's house, a Jew was selling honey.

The 1708 census shows that the situation continued into the beginning of the eighteenth century, when many shops in the town centre market (rynek) belonged to Jews.

The census showed there were 50 Jewish scrap metal vendors, 80 salt traders and 80 pedlars, 30 moneychangers, 30 money lenders with interest, 20 paramedics (compared with 19 Christians) and four physicians.[13]

The townspeople looked askance at the Jews and demanded to have the town cleansed of their competitors, but in vain. The nobles and the magnates as well as the Church who received high rents, had interest in keeping their Jewish tenants in town.

Although it was forbidden to sell any houses situated outside the Jewish Quarter to Jews, and despite the court hearings and verdicts regularly passed against the Jews, a few Jews still managed to break through the barrier and purchase houses from Christian nobles and townspeople outside the Jewish Quarter. Besides the tradesmen, also the Craftsmen's Guilds escalated their fight against the Jews. As their wished to secure cheap raw material for their men, they lobbied to forbid the Jews from exporting.

According to the 1708 census there were at Lwów 18 Jewish tinsmiths (there were no Christian tinsmiths); 44 Jewish goldsmiths (10 Christian); 50 Jewish butchers (eight Christian); 10 Jewish weavers (one Christian); there were no Jewish bakers within the town (20 Christian), 20 outside the town; 50 Jewish tailors (47 Christian).

The condition and management of the Lwów community was miserable. In 1703, as the authority of the community leaders had eroded so that they were unable to collect any dues despite imposing ostracism on the community, the Voivode Stanislaw Jablonowski undertook to regulate the conditions.

On the 5th October 1703, in a special regulation given at Mariampol [Marijampole], the Voivode ordered that the community leaders be elected, and that they be vested with the power of jurisdiction. Concurrently,

[Pages 127-128]

he forbade any officer from interfering in the community affairs, other than in appeals at the district law–court.

The dismal situation the Jewish population had found itself in due to the events of war, lowered the public discipline. Consequently, it was appropriate to increase the community's authority,[14] especially in face of the heavy financial debt with which the community was burdened. In 1727, the community owed 438,410 Gulden to the municipality alone, as its share of contributions during the wars; all the synagogues were emptied out of all gold and silver they had contained. In order to fulfill its obligations, the community was therefore obliged to take out loans which entailed very high interest.

In 1707, the community took out a 4,000 Gulden loan from the “Discalced [barefoot] Carmelites”, at 7% interest; and in 1714, a 15,000 Gulden loan from Benedykt Karkowski. The community owed also 42,000 Gulden to the Brotherhood of Stauropigiańskie; 4,000 Gulden to Magdalena Pruszkowska; 2,680 Gulden to the nobleman Aleksander Siedleski; 12,600 Gulden to the nobleman Adam Karsz; 190 Gulden to the Christian Medics Guild.

In that drained financial situation new taxes were levied on the community. The meat taxes as well as “tenure” were increased in order to repay the debt of 52,000 Gulden to the Dominicans. But even that was of little avail and the community fell into debt with no way out.

While the Lwów community declined, a major mogul rose from among its ranks to succeed in encouraging, raising and returning it to its greatness.

In 1714, the great scholar [gaon] Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsz ben Jakob Askenazy (the “Sage Cwi [Tzvi]”) was elected Rabbi of the two communities, and was received with honour and great joy. He was also respected by the Christians, “and the Jewish community was not alone in receiving him with the greatest honour, for soon also the Gentiles were at his door and greeted him with gifts. And during the short time he was there, he established substantial regulations for the holy community, and raised its fame and glory. He adjudicated on men of violence, and the men of malice surrendered to him. He also removed the powerful community leader, Reb. Zelik from his appointment, after it was revealed that he had stolen community money and robbed the poor. And the latter went and delivered my sire, my teacher [of Jewish studies], the Rabbi of blessed memory, to the governor and the bishop. My sire, my teacher [of Jewish studies], the Rabbi of blessed memory was tried by them, and fear spread throughout the community since the Jews there greatly feared the governors. Yet, my sire, my teacher [of Jewish studies], the Rabbi of blessed memory went to see them, spoke with them in Italian, and the governors showed him such honour as he had never been shown before. The bishop then insisted he sat in the chair next to his own, and kept his hat on. God caused them to like him, and they granted him the right and power to judge almost capital law cases in his community whenever he saw fit, and he left them with great honour and in peace. All the principled as well as the malicious people present were filled with terror. They followed his orders and surrendered to him, of blessed memory, since they feared him, and to the entire congregation he was honour and glory and greatness.

The “Sage Cwi [Tzvi]” knew how to impose his authority on everyone. Reb Mojzesz Jechielis who imposed strict authority on his community members, accepted his precepts and surrendered to his authority. Even wealthy men who appeared in front of him in the law–court did not deter him, and he knew how to enforce his verdict upon them. The community members regarded him as a patron who safeguarded their interests since he knew “to ensure that everyone be content and be taken care of, be guided honestly in accordance with Jewish law, both in community affairs and the value of the heavy taxes; in the affairs of the many and the individuals; in general and in particular. That was his source [of wisdom], also in matters between man and man, to conduct an honest, unbiased trial.[15]

He was particularly involved in education and in the study of the Torah. He regretted that “some men, who had not even read the Bible and did not know the Mishnah [religious doctrine], men who were no experts in the fundamental issue, and who had not examined the first adjudicators, had become rabbis”. As a consequence, he decided on fundamental amendments to the education and the methods of study. He assembled the teachers “and set them the method of Bible teaching, starting with grammar”. But before he was able to establish the amendments, he died at Lwów on the 29th May 1718.

After his demise, the Rabbi of Lublin, Rabbi Simche ben Rabbi Nachman HaKohen Rappoport was elected, but he fell ill on his way to Lwów and died on the 4th August 1718.

He was followed by the great–grandson of Rabbi Jozue [Joshua] Falk, Rabbi Jakob ben Rabbi Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsz [Hirsch] (1681–1756), author of Pneh Josua, and son–in–law of Lwów's community leader Rabbi Salomon Segal Landau. He took an active part in teaching, and the community appointed him to oversee the teachers. [Some years earlier] on the 27th November 1703, his wife Lea, his mother–in–law Rösel, her father Schmerl Katz and his daughter, had all died from an explosion in the gunpowder store–room. The loss depressed him so much that he left Lwów. He took, Taube, the daughter of the wealthy Lwów Reb. Isachar Ber for his second wife, and served at the Rabbinates of Tarlow, Kurow and Lisko.

In 1718, according to Rabbi Jakob Emden's account, his wife's family attempted to obtain the Lwów Rabbinate for him. In September 1718, after his mother–in–law had spent 30,000 Zloty to attain that goal, he was elected Rabbi of the Lwów community and the region. No sooner had he returned to Lwów as head of the Rabbinate than one of the wealthy men lobbied on behalf of his son–in–law, Rabbi Chaim ben Lazer, who was Rabbi at Złoczów [Zelechów] but lived at Lwów, to be made the town's Rabbi.

Rabbi Chaim was the grandson of Rabbi Pinkas Mojzesz Charif who had been

[Pages 129-130]

rabbi at Lwów. His father–in–law who acted as mediator to Voivode Jablonowski, was able to gain the latter's support as well as that of some community leaders. And so, in 1720 – once the tenure of Rabbi Jozue [Joshua] ben Cwi [Tzvi]–Hirsz had come to an end – the community did not renew his tenure, replacing him instead with Rabbi Chaim ben Reb. Lazer, who was also approved by Voivode Jablonowski. He was however unsuccessful in obtaining the Rabbinate for the region.

The two factions parted company and the disputes in Lwów led to the defamation of Rabbi Jozue and “they forfeited his money and assets losing him 30,000 Zloty which he had handed to the community to clear its debt”. Rabbi Jozue was forced to leave Lwów in 1720 and he settled temporarily at Buczacz. He turned to the communities of the Lwów region, who determined in his favour and did not acknowledge Rabbi Chaim as the regional Rabbi, declaring that they would not comply with the Lwów community. On the 17th July 1720, at the regional committee session held at Kulików, a boycott was declared against Rabbi Chaim and his followers.[16] The verdict stated clearly that “we, members of the region, no longer have anything to do with the holy community of Lwów nor with any rabbi whom they elect. All of us as one, however, all the regional communities from one end to the other, owe respect to the above mentioned Rabbi, the Great Light, our great teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Jozue. He alone was our President, and which ever regional community he chooses to reside in, there he will remain, and we will follow him in all Rabbinical matters”.

The Lwów community members were declared “transgressors” and Rabbi Jozue was granted the “authority” to boycott and banish the “sabotaging” Rabbi from all the communities of the region.[17] The Lwów community was sentenced to pay a 30,000 Zloty fine to Rabbi Jozue, a verdict which established him officially as the Rabbi of Lwów and the region. Despite this he did not return to Lwów but settled at Buczacz [Buchach] since Kinowski, the Starosta of Buczacz was in dispute with Voivode Jablonowski, and so Rabbi Jozue was certain that there no harm would befall him.

Meanwhile his dispute was being deliberated by the Council of Four Lands. In 1724, the Council headed by Dr. Izak Chazak (Fortis), noted Rabbi Mojzesz ben Elejzer as “captain”, and justified Rabbi Jozue's claim for 30,000 Zloty.

In 1727, when Rabbi Jozue left for Jaroslaw to represent the Lwów Rabbinate at the session of the Council of Four Lands, his opponents advised Voivode Jablonowski who asked the Starosta at Jaroslaw to hand Rabbi Jozue to him. Only due to his friend Dr. Izak Chazak (Fortis), who at the time acted as comprehensive community leader of the Council of Four Lands, was Rabbi Jozue made aware of the matter. He then hid inside a wardrobe in his room till the detectives left. He was saved, left Jaroslaw and returned to Buczacz.

Rabbi Jozue continued to live at Buczacz under those circumstances till 1730, when he was invited to succeed Rabbi Michael Chassid as head of the Rabbinate at Berlin.

While at Berlin, he tried to have the verdict of the Regional Committee and of the Council of Four Lands, fulfilled, but to no avail. He also left power–of–attorney to his sons and daughter, but it is not clear whether they successfully obtained the compensation from the Lwów community.

At the time, Rabbi Chaim ben Izak Reizes served (1728–1737) as Head of the ritual law–court [Beth Din] of both communities, as well as the Lwów representative in the Reissen Regional Committee.

The number of Shabbatai Cwi [Tzvi]'s followers in Podolia and Reissen rose, and their influence increased particularly throughout the Reissen towns: Zloczow [Zolochiv], Rohatyn, Podhajce [Podhajze], Horodenka as well as Lwów. Many of his followers came from Podolia, which lay close to Turkey. They settled in towns and attracted the interest also of those from scholarly circles.

When the rabbis, who greatly objected to their actions, noted the undermining of the Torah and of the commandments, they gathered, by order of the Council of Four Lands, in the great synagogue outside Lwów on the 2nd July 1722. The regional and town rabbi, Rabbi Jakob Jozue [Joshua] author of Pneh Josua, together with seven of his religious court–judges, declared the excommunication of the sinners by blowing the Shofar [Jewish ritual ram's horn] and extinguishing candles. The entire community stood trembling as they listened to the wording of the curse “and babes learning the Torah repeated after them, Amen… And several transgressing sinners of that accursed cult stood with us on the stage [Bimah] and while sobbing and wailing to heaven even they admitted their misdemeanours and recounted their actions, in accordance with the prayer book which they had put together. After leaving the synagogue on the 2nd July, they had to undertake a self inflicted mourning and ostracism for seven and thirty days, as laid down by the law; every precept pertaining to the outcast and the mourner, besides other penalties and reprimands set by us seven Rabbis, and that was just the beginning.”[18] And afterwards they confessed their sins and publicly received their due.

Similar ostracism was declared in all other communities. Despite the ostracism however, the followers of Sabbataj Cwi [Shabbatai Cwi [Tzvi]] could not be completely wiped out. On the contrary, the number of the cult followers increased, and some years later they joined Jakub Frank's faction.

Lwów's community life was not tranquil either. Since the controversy with Rabbi Jozue ben Cwi [Tzvi] (author of “Pneh Josua”), the community–leaders tried to define the Rabbi's authority.

In 1726, they submitted a complaint to Voivode Jablonowski that the Rabbi was introducing changes which were in contravention

[Pages 131-132]

of the regulations. They also requested that the Rabbi's authority and limits of operation be explicitly specified.

On the 20th July 1726, the Voivode issued the following regulations:

Relying on the nobles' sponsorship they refused to recognize the community's authority or to pay the taxes it levied on them. Things led to conflicts and from time to time the community–leader, Izrael ben Reb. Lewi [Levi], was obliged to enter in his register appeals against “The Jews who reside within the suburbs under the auspices of Princesse Jablonowska and perform circumcisions in private houses, those who avoid paying community taxes, as well as births, marriages and tenure fees.”[20]

Those Jews were mostly owners of shops within the town and therefore it was hard for the municipality to remove them, since their sponsors found endless stratagems to keep them there. The community found it difficult to withstand the hostile attitude that grew under the influence of the Catholic Church, which specifically at Lwów ended in blood–libel trials against Adela of Drohobych [Drohobycz], and against the Reizes brothers.

Miss Adela, the daughter of the head and leader Rabbi Mojzesz Kikenes, was a beautiful and very wealthy woman from the Jewish Quarter, and the subject of envy of the Christian neighbours. On the eve of Passover 1710 , soldiers and officers of the law–court broke into her house and found the body of a dead Christian boy that had been thrown there. The incited Christian mob wanted to attack the Jews, but Adela who wished to save her brother, took the blame on herself without the knowledge of the community, stating that she had killed the child. The law–court sentenced her to death. Once the sentence was published, her Christian cleaner confessed that she had put the murdered Christian child's dead body in her employer's house. The judges agreed to set–aside their verdict, on the condition that Adela become a Christian. She refused, and on the 21st September 1710, she gave her life for God's sanctity.

The trial of the brothers Chaim and Jozue Reizes [Reices] which was staged against a different background, echoed well beyond Poland, with detailed reports of it published in the “Berlinische Priviligierte Zeitung”,[21] the “Gazette de France”,[22] and the matter was also reported throughout the diaspora.[23]

The setting for the libel was the small town of Strusów, where the cobbler Jazko Sjarizow announced that a person who had converted to Christianity and later returned to the bosom of Judaism, was hiding among the Jews. After a thorough investigation by the Church authorities it was discovered that Jan Filipowicz first converted at Lwów where he resided in the house of the painter Lukasz Wijniowski, and later returned to Judaism. From Lwów he went to Dobromil and Drohobych before arriving at Strusów. There he was arrested, he was incarcerated in the church of Uniejów and later was transferred to Lwów.

Initially he did not wish to return to Christianity, but when he was made aware of the punishment, he agreed to remain a Christian. And then the investigation started into how and by whom he was tempted to return to Judaism. Severe torture induced him to reveal that a certain Jew named Moszko put him in the cellar of the rabbi's house where, in the presence of rabbis, the cross which he had carried with him was broken and the Christian faith defamed. Based on his revelation, the Starosta of Lwów ordered that the Rabbis of Lwów, Drohobych and Stryy [Stryj] be imprisoned. The Rabbi of the Lwów region, Rabbi Chaim, who was at Żółkiew when they came for him, was able to escape. In his stead, his mother, and the community leader of Żółkiew,

[Pages 133-134]

Isser ben Mardochaj were arrested as well as the head of the religious law–court of Lwów, Rabbi Chaim ben Izak Reizes [Reizeles] and his brother Jozue; also Dawid Reizes from whom they confiscated 8,000 Zloty, and Mojzesz who, according to Filipowicz's revelation, had tempted him to leave Christianity. The Rabbi of Szczerzec [now Shcherets] succeeded in evading the authorities.

According to an anecdote the Jews were tortured for 40 days but none of them confessed. Then, the archbishop made the prisoners stand in a line and together with Filipowicz he passed in front of them, and again Filipowicz was unable to recognize the culprit. But when Rabbi Chaim Reizes remarked to the archbishop, in Latin: You have kept them here in vain for forty days, Filipowicz retorted[24] “This is the one, I recognize his voice”.

Thus ends the anecdote, the truth of which is hard to ascertain.

According to archival material, a law–court made up of Stanislaw Jablonowski the Voivode of Reissen, Janusz Wiśniowiecki the Kraków castellan, Stefan Humieckie the governor of Podolia, and Stanislaw Potocki the Starosta of Lwów, sentenced Filipowicz to death by hanging. And to appease the Christian mob incited by the clergy, Rabbi Chaim ben Izak and his brother Jozue, were also sentenced to death, by burning. The elder brother was also sentenced to be dragged by a horse throughout the town before his death. The sentence was executed on the eve of Shavuoth [the Jewish Feast of Weeks].

According to Christian sources, Jozue committed suicide by cutting his own throat during his incarceration. The Jesuit priest Zoltowski still tried to entice Rabbi Chaim to convert to Christianity, promising him freedom, but in vain. Subsequently he was handed to the hangman. On the eve of Shavuoth (13th May 1728), he and Jozue were burnt to death.[25] Their property was confiscated and transferred to the municipality for repair to the fortifications.

The community redeemed their ashes for interment at the cemetery. Chaja,[26] the daughter of Rabbi Chaim Reizes, was also implicated in the trial, and was also killed.[27]

The murder was carried out without any protest from the Starosta, although it was his responsibility so to do since the Reizes brothers were citizens of the community outside the town which was under his authority. He probably did not dare oppose the omnipotent Church, even though the Starosta was predisposed towards the Jews. In 1729, a year after the Reizes trial, the Starosta leased all the taxes to Jewish merchants, and in disputes between the Jews and the municipality he always sided with them, probably against payment.

During 1732–1733 a wave of students' attacks (Schüler Gelauf [students' run]) hit the Jews of the suburbs, but in 1733, the students felt the response of the Jews who hit and struck them. After that, the students did not dare continue with their attacks.

At the time, Poland saw the spread of Hassidim and of active men who practised self–denial in the manner of the Safed Hassidim. 1690 saw the publication of HaAri's [Rabbi Izak Luria ben Schelomo] version of the “Shulchan Aruch” [an abbreviated form of the Jewish ritual law] at Kraków and Frankfurt–an–der–Oder. At Dyhernfurth [Brzeg Dolny], with the endeavour of the rabbis of the Council of Four Lands, the “Shulchan Aruch Way of Life” was also published,

|

|

|

|||||

| Seal of Izak ben Abraham HaKohen of Lwów. Dated 1654. Showing the mark of a Priest [Kohen] – priests's palms held in benediction. | A woman's signet ring from Poland. Single–stone. Inscription: “To light the Sabbath Candle”, and candelabrum with three–arms carved and filled with gold. 17th century. | Seal of Aron ben Meszkisz HaLevy, Lwów. Dated 1654. Showing the mark of the Levi'im [Levis] – a jug for washing the hands of priests. | |||||

|

|

|

|||||

| Seal of Józef–Salomon ben Jeruchim of Lwów. Dated 1629. Showing the sign of the owner who was born in the month of Sivan [the 9th month in the Jewish calendar, as it is presently arranged]. | Seal of Jekusiel–Zalman ben MaHaRaR Eleazar of blessed memory, of Lwów. Dated 1654. | Seal of Józef–Salomon ben Jeruchim HaLevy of Lwów. Dated 1629. Engraved with Józef's birth sign; he was born in the month of Sivan. Twice enlarged. |

together with interpretation of “Turei Zahaw” by Rabbi Dawid HaLevy of Lwów, and interpretation of “Magen Abraham” [Protector of Abraham] by Rabbi Abraham Abele of Kalisz, thus uniting all of HaAri's customs of the Halacha [Jewish ritual]. The state of ignorance in Poland encouraged the belief in secret faiths, demons, spirits, talismans, incantations, names and dreams. “Renowned figures”, who also claimed to expel spirits and demons through the power of names, attracted the following of individuals willing to accept potions, folk remedies, amulets and incantation from them. Rabbis who perceived the influence of the Sabbateans in such actions, set out to wipe out the rest of that cult. Rabbi Jozue Falk the author of “ Pneh Josua”, played a major role

[Pages 135-136]

in that struggle, especially after he had left for Berlin, by resolutely attacking Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz [Eibenschütz or Eibeschitz].

The controversy between Rabbi Jakob Emden and Rabbi Jozue Falk on the one hand, and Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz on the other, had attracted his disciples within Poland to a counterattack, which began with a declaration at the Lublin Synagogue, of a boycott against Rabbi Jakob Emden. The controversy provoked tempers in Poland, it was much discussed during the sessions of the “Council of Four Lands”, and its echos reached Lwów and the region.

Among Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz's supporters at Lwów, one knows of the biblicist Reb. David Fest also known as Lemberger, who exchanged letters with Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz, whom he rated “pure and clean of purpose and perfect of mind”.[28]

Unlike the rabbi, Reb. Chaim HaKohen Rappaport of Lwów who did not partake in the controversy, the regional rabbi, Rabbi Izak Landau was among Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz's sympathizers. He and his father–in–law, Rabbi Abraham ben Chaim, head of the Land of Lublin, and his son Rabbi Jakob, rabbi at Lublin who had been one of Eybeschütz's pupils, influenced the session of the “Council of Four Lands” which dealt with the controversy in 1753. The Lithuanian community–leader Abraham, and Baruch Jewen, King August III's agent, sided with Rabbi Jakob Emden.

Swayed by Rabbi Izak Landau, a boycott was issued at Lublin against Rabbi Jakob Emden (28th July 1751). At Lwów, Rabbi Chaim Rappaport did not intervene in the controversy and did not sign the writ in favour of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz which was published at Jaroslaw by the leaders and the rabbis of the “Council of Four Lands”, on the 30th October 1753.[29] The position of rabbis and leaders of the Land and region of Lwów did not concur with that. At the session of the Council at Żółkiew – even before the conference of the “Council of Four Lands” at Jaroslaw – they signed a document in favour of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz,[30] rather than the writ published by supporters of Rabbi Jakob Emden on the 30th October 1753. Rabbi Jakob Emden's supporters who were in the minority and defamed Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz, even ordained a boycott and burning of books which espoused his views.

As known, Kommissar Kazimierz Granowski, of Radom did not permit the “Council of Four Lands” to discuss the controversy between Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz and Rabbi Jakob Emden, as the matter was not under his authority.[31] Only after the Kommissar had left the meeting, that is to say after its official conclusion, did the supporters of Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschütz gather to decide in his favour. On the same day, the books of his opponents were burnt publicly in the Jaroslaw market place.

The following day, the supporters of Rabbi Jakób Emden also published a similar declaration which included a significant note describing the session and the debate: “All acts and affairs of that Council were controlled by strangers and the hand of a gentile meddled in it”, and “due to that fact” we were unable to mend the generation's breaches, to enclose the matter in a rose strewn fence.

[Pages 353-354]

Notes – CHAPTER 8

All notes in square brackets [ ] were made by the translator.

[The spelling of personal names was largely sourced from books cited by the author.]

[Pages 355-356]

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Lviv, Ukraine

Lviv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Apr 2023 by LA