![Map of the Town of Drohobycz - dro001.jpg [79 KB]](images/dro001.jpg) |

|

|

[Page 10]

by Shin Shalom

Translated by Sara Mages

Distinguished members of the Association of Former Residents of Drohobycz,

Boryslaw and SurroundingAlthough I was not born in Drohobycz, it is the city of my childhood, the city where my family lived, that thousands of capillaries of memories connect me to it and to its vibrant, simple, sensitive and sharp-witted Jews.

Something in my heart revolts against the division into communities communities, ethnicities ethnicities, tribes tribes, and towns towns even in the State of Israel, even if

it comes for the lofty purpose to which this book was dedicated. Therefore, I will be content to say, well done and thank you for the hard work and effort you put into erecting a monument to a Jewish metropolis, and I will express my faithful hope that this book, written from a holy and pure intent, will also serve as a base for the complete unity of Israel to which we strive.

Your brother,

S. Shalom

Haifa, Hanukkah 5716 [1955]

[Page 11]

by Dr N. M. Gelber

Translated by Dov Youngerman and Yocheved Klausner

Edited by Valerie Schatzker, with the assistance of Alexander Sharon and Daniela Mavor

Drohobycz was established early as a royal town chartered under the Magdeburg Law.[1] The towns of Drohobycz, Borysław, Dolina, Stryj, and the surrounding areas were important for their salt mines. Because the mines did not yield pure salt, the mineral had to be refined. The earliest documents record that a church built in Drohobycz in 1392 was used as an administrative centre for the salt refineries. Refined salt was sold and distributed by agencies, most of them leased to Jews.

In Lwów, on 31 March 1460, King Kazimierz Jagiełłończyk (1427–1492)[2], who reigned from 1447 to 1492, reaffirmed the privileges that had been granted to the townspeople and their leaders by King Władysław[3], especially the Magdeburg Law and the right to cut trees freely in the royal forests for both construction and firewood. Drohobycz enjoyed royal patronage, especially from King Zygmunt I[4], who founded a children's hospital there in 1540. In 1571, a shelter for old people was established. King Zygmunt August[5] also helped the town's development by granting various privileges that aided general growth and commerce. The town was situated at an economically strategic point on the Lwów–Grodek–Sambor trade route, with easy access to the salt mines near Drohobycz and Stebnik. King Zygmunt August also transferred to the town government the right to levy tax on beverages, as well as on wagons which came to transport salt or other goods.

The Ruthenian settlement grew from the start of the sixteenth century. Kings Jan Albrecht[6], Aleksander Jagiełłończyk[7], and Zygmunt I granted the Ruthenian church comprehensive privileges that not only guaranteed freedom of worship but also established the foundation for the Church's economic existence. Nevertheless in 1540, under the influence of Polish settlers, Zygmunt I prohibited the erection of a Ruthenian church inside the city walls.

Jews lived in Drohobycz as early as the beginning of the fifteenth century[8]. In 1404, only Jews, who were salt lessees, were permitted to live within the town; the others lived in the suburb of Na Łanie,[9] where they eventually set up their own community. Although they were given permission to settle on lands adjoining the mines, they were not allowed to establish a cemetery, since a cemetery and a synagogue always constituted the basis for a Jewish community. When Jews had a cemetery, they were reluctant to leave the area, being fearful of leaving behind the graves of their ancestors.

One of the earliest Jewish salt–mine lessees in Drohobycz was known by the name of Wolczko. Besides leasing the salt mines, Wolczko served as a banker for the court. At the time, the king, Władyslaw Jagiełło,[10] took an active part in the settlement of Galicia, or Russyn,[11] as it was then known.

In 1425, we hear about a Drohobycz Jew by the name of Detko or Dzatko, who was a salt mine lessee, a wholesale merchant with trade connections in Turkey and Kiev, and a supplier to the royal court. In the king's correspondence, he is known as officialis noster (our representative). Detko also had financial dealings with the court of King Władysław Jagiełło, with various noblemen, and with town dwellers in Lwów, to whom he paid sizeable sums on the king's orders.[12] We know of yet another lessee from Drohobycz, called Natko or Nathan, who held the lease for the salt mines from 1452 to 1454, paying a total of 3,050 grzywna (one grzywna was worth 200 grams of silver) in rent for two years.

Shimshon of Źydaczów, a well–known lessee of that century, held the lease for the mines from 1471 to 1474. He had to pay 2,363 grzywna a year for the lease to collect the royal taxes in Lwów and Grodek, and for the lease for salt in Drohobycz. He also had to supply the king's court and in 1472, the archbishop in Kraków with one roll of Turkish silk.

In the fifteenth century, the salt mine lessees of Drohobycz were the most important in Russyn. They sought to obtain a monopoly on the right to collect the town's income itself. Jakub Judicz was a salt mine lessee in Drohobycz and a well–known wholesale merchant in Russyn. At the end of February 1564,[13] King Zygmunt August granted him the lease on brandy, which the king described as being to the town's advantage. Based on that royal privilege, the municipal government, on its own initiative, leased to the Jews the collection of the annual income

[Page 12]

from the municipal monopolies of the alcohol distilleries, salt refineries, and the import of lumber and building materials. In turn, each lessee employed sub–lessees, as well as a considerable staff of Jewish customs officials and clerks. This increased the number of Jewish inhabitants of the area.

The Gentiles in Drohobycz were not comfortable with this situation and made every effort to get rid of the Jews. They used the only means at their disposal: the law de non tolerandis Judaeis (the law of not tolerating Jews).[14] In 1569, the conflicts concerning the presence of the Jews led to a dispute between the city and the king. In that year, the king, without having the authority to do so, mistakenly leased the tax on alcohol to two Jews, Shmuel Markowicz from Chelm and Isak Jakuszow of Lwów. The city protested, maintaining that the right to lease the alcoholic beverage tax was the city's exclusive privilege. Because of this protest, the king was forced to rescind his decision in that same year. The lessees brought a suit against the city (adversus famatos proconsulem, consules, advocatum et scabinos oppidi nostri Drohobycz). The king rejected the lessees' claims. In his decision, he stated that the town's ancient privileges gave it the right over propination. (This was the right over the production and consumption of alcoholic beverages, which was usually owned by the nobility; peasants could not purchase alcohol that was not made in the landowner's distillery and were obliged to purchase a given quantity of vodka). Thus, he argued that he had no power to grant the right to this tax to Shmuel Markowicz and Isak Jakuszow. It would have been impossible to grant them an advantage that infringed on the city's privileges and they were obliged to return the tax to the town.[15] This dispute encouraged the city to try to obtain the privilege of non tolerandis Judaeis. Its efforts bore fruit. On 20 March 1578, when about 3,600 people were living in Drohobycz, King Stefan Batory [16] granted this privilege to the city. Under this law, Jews were forbidden, either in Drohobycz itself or immediately outside its walls, to lease, rent, or conduct any trade whatsoever, except at fairs, and even then, only on occasion. They were also forbidden to settle in the area outside the city. Any Jew who tarried in the town longer than three days was to be punished with a fine of 12,000 marks, and whoever gave him lodging would be fined 100 grzywna. The fines would be divided equally between the royal treasury and the town to cover its needs. [17]

For fifty–seven years, there were no Jews in Drohobycz or its environs. In the same era, the town suffered from incursions by Tatar hordes and in 1618, the entire town was destroyed. This dire situation continued throughout the 1640s to the point that in 1645, the town was relieved of paying all taxes due “to the great destruction.” [18] In 1635, there was a notable turning point [for the Jews]. The wojewoda (head of a township) of Russyn, Jan Danielowicz, gave the Jews permission to settle on his lands in Na Łanie near Drohobycz. They were permitted to live only outside the town, near the salt refineries. They were forbidden to establish a cemetery. This permission was granted because of economic necessity. The lessees of the salt mines and the customs houses, and even the villages in the Drohobycz district needed their Jewish clerks. Thanks to their efforts this permission was obtained from Danielowicz. [19]

It should not be forgotten that, in this very period, there were royal estates in the environs of Drohobycz held by two very wealthy Jews of Lwów, Yitzhak Nachmanowicz and Izak ben Mordechai (Markowicz), who lived and acted like lords. Their influence with the authorities was so great that they could obtain permission for a Jewish settlement. They lived in Na Łanie, on a private estate under jurydyka podmiejska (suburban jurisdiction). The Jews who lived there were not subject to the laws of the town. This permission was confirmed by Kings Wladislaw IV and Jan Kazimierz.

In 1648, the Cossacks of Bohdan Chmielnicki made incursions near the town. The townspeople contacted them. They collected jewelry for them in the Ruthenian church, but the priest stole it and fled from the town. When the Cossacks appeared before the town, the Catholic townspeople opened fire. The Ruthenians abandoned the batteries and shouted to those who remained to cease fire, since they would succeed only in destroying themselves and others. [20] In the meantime, another group took the weapons from the town and the batteries and handed them over to the Cossacks. Together with the Ruthenians, the Cossacks attacked the Catholic church, slaughtered the Catholics they found there, and pillaged everything in sight. The Cossacks withdrew, thanks only to military assistance of the citizens of Stryj. After the troops from Stryj left the town, Ruthenian people from the town and villages gathered together near Drohobycz; they looted and destroyed the town. It is not known what happened to the Jews of Drohobycz, but it is assumed that they fled with those townspeople who escaped to Stryj.

In 1663, only fifteen Jewish homes were counted in the census in the Na Łanie suburb. This census was conducted on 8 October by the officials of Volhynia, the starosta [21] of Pinsk Jan Franciszek Lubowicki, [22] the scribe of Halicz Jerzy Mrozowicz, and the royal secretary Stanisław Makalski.

During this census, the town complained to the authorities that the Jews living in Na Łanie brought only problems for the town. They had settled and built their own street, Ulica Żydówska (Jew Street). Contrary to the laws and privileges of the town, they had opened shops and were engaged in commerce, selling mead, liquors, beer, and brandy. The town requested that the Jewish street be destroyed and the Jews evacuated, since in the past Drohobycz had only one or two Jews working in the service of the salt mines.

To answer this complaint, the Jews produced the royal permit of King Kazimierz [23] given in Warsaw on 18 December 1659, which included the letter of the deputy minister of the treasury, Daniłowicz [24] and the confirmation of that letter by King Władysław IV. [25]

[Page 13]

The Jews maintained that they were also in possession of other, even older privileges, but they could not produce them, since they were held by the jurist Zadworny in Warsaw. After considerable deliberation, the authorities recognized that Łan belonged to the Drohobycz district, which collected an annual rent of 100 zloty from the Jews. They made no definite decision but transferred the matter for adjudication to the royal court that was scheduled to convene two weeks after the Sejm (the Polish Parliament) was to assemble. Aside from this grievance, the town also complained that the local lessee, Aron ben Yitzhak (Izakowicz) maintained four soldier–servants for his convenience, forcing the town to provde them quarters and pay each of them one and a half gold pieces per week. Residents of the suburb complained that Aron ben Yitzhak would take whiskey from them and prevent their buying whiskey for weddings and other joyous occasions at cheaper prices.

Aron ben Yitzhak replied that he maintained not four but two servants with the permission of and under contract to the town. These servants were needed to expedite the sale of whiskey and to prevent its being stolen and sold by neighboring peddlers.

The town officials ruled that according to the agreement with the town, Aron ben Yitzhak had the authority to maintain two soldier–servants. The townspeople could impose new conditions concerning soldier–servants in any new contract they might sign. The complaint of the suburban residents was found to be unjustified.

Aron ben Yitzhak complained to the authorities that the town government had not repaid a debt of 2,511 gold pieces and 10 groschen that it owed him and did not allow him to deduct this from his rent, even though the town did not deny that it owed him that sum. The final ruling was that Aron ben Yitzhak could deduct the debt from the rent payments in three stages. [26]

Following this census, on 28 September 1664, the town government rented to the Jews of Łan one tavern and ten shops for the sale of merchandise permitted by the guilds for a six–year period. An annual rent payment of 200 gold pieces was paid in advance. Under this agreement, the Jews were released from several debts. The city would not allow any foreign Jew to reside in the town without the agreement of the leaders of the Jewish community. The Jews were not subject to the town's jurisdiction but to that of their own courts and the courts of the wojewoda. [27] Any disputes with the guilds would be argued before the town council. Jews from outside the town could not be employed in the shops. Any party that did not abide by the terms of the agreement would be punished with a fine of 1,000 gold pieces.

This contract was signed on behalf of the Jews by Isaak Josefowicz, Shmuel Herszowiz, Isak Majerowicz, Mendel Dawidowicz of Przemyśl, Lazar Ruwen Zelkowicz, Moshe Jakubowicz, Shlomo Berkowicz, Dawid Josefowicz, and Yudka Zalmanowicz of Krakow. The contract was renewed in 1672 and 1678. The third contract (1678) was kept only four years instead of six, since the Jews sold mead and beer in eight taverns instead of two and maintained forty stores instead of eight, as provided in the agreement.

Little by little, the settlement grew. Despite the legal prohibitions, wealthy Jews gradually penetrated the city itself. Over time, they established a community with many institutions. On occasion, this situation stirred up the opposition within the town government and protests would be raised. Relations between Jews and non–Jews were not always friendly. The situation grew especially bad in the Drohobycz area following the deteriorating situation in the villages and suburbs with Jewish lessees and their officials. Once more, the townspeople and craftsmen saw the Jews as strong economic competitors. They complained that the Jews were undermining their existence and destroying their economic standing.

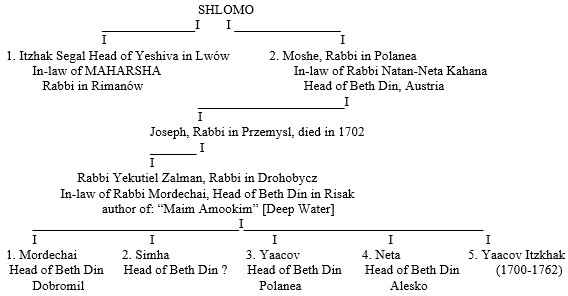

In 1670, rabbi and chief religious judge, Rabbi Yekutiel Zalman Siegel Kharif, the son of the rabbi of Przemyśl, Josef Kharif [28] served in Drohobycz. He was rabbi for ten years. In 1680, his position was taken by Rabbi Zvi Hirsch, the son of Chaim, rabbi in Kołomyja, the son of Yehoshua of Kracow, who had formerly been rabbi in Brzeźany. From Drohobycz, he went on to occupy the rabbi's position in Tyśmienica. His son Israel, [29] who was also rabbi of Drohobycz and later lived in Kamieniec Podolski, was appointed by King August III [30] on 26 February as his agent and servant with the right to buy wine and other goods for the king without paying customs duty. In the letter of appointment, [31] he was described as rabbi of Drohobycz (Israel Herschowitz Rabinus Drohobicensis incola Camenecii Podoliensis) and as a wise and honest man. In fact, he was the only Jewish agent at the court of King August III. In 1755, he was also appointed as a trustee of the House of Israel in the Council of Four Lands. [32]

After Rabbi Zvi Hirsch, R'Yehuda Leib ben Jacob was appointed rabbi. In 1696, he gave his endorsement to the book, Dat Yekutiel (Źółkwa: 1696) by R'Yekutiel Siskind, the son of Rabbi Shlomo Halevy, who printed the 613 mitzvot in rhyme.

His successor in the rabbi's chair was the Rabbi Naftali Hirsch, who on 21 Sivan, 5526 (1766) in Drohobycz gave his endorsement to the book Ohel Moed (Frankfurt am Oder: 1767) by the rabbi and chief religious judge of the community of Ulanów, R'Yosef Jaski, the son of R'Yehiel Michal. It presented new variations on the number of blessings and the laws of the holidays.

[Page 14]

From the administrative standpoint, the autonomous Jewish institutions of Drohobycz, which was in the Przemyśl district, were part of the assembly of Jewish institutions of the province of Russyn; they sent two community leaders to its meetings. Their work began to be noticed around the mid eighteenth century. In that period, there lived in Drohobycz R'Isak Chajet (1660–1726), one of the most famous scholars of his generation and a well–known kabbalist and sharp opponent of Shabtai Zvi. He was the grandson of the Vilna rabbi R'Manosh Chajet. He served as rabbi in Skole, but due to disputes with the leaders of the community, he left its rabbinate and settled in Drohobycz, where he also took an active role in Jewish life. He died in 1726 and was buried in Drohobycz.

The Jewish community grew substantially during the reign of King Jan III Sobieski (1696–1796), who had a great deal of interest in the situation of Jews in Żółkiew, Przemyśl, and Drohobycz. He had a special concern for the Jews in Drohobycz and did a great deal to improve their condition. On 13 June 1682 under his reign, the lessees of the taverns and shops, along with the leaders of the community, agreed to pay an annual rent of 300 gold pieces for six years, starting on June 1, 1683. After the expiration of this agreement, the city was authorized to act according to its laws and privileges, if it did not wish to sign a new contract. This time the pact was signed by the community leaders: Izaak Jozefowicz, Abraham Moszkowitz, Srul Dawidowicz, Giecio (Getz) Helclowicz, Israel Hayfer Lwowski and Szymon Kru. [33] In 1684, the Jews already had forty shops and dominated all branches of commerce. Of course, the townspeople looked upon this unfavourably; they were not ready to tolerate the expansion of the Jewish community in the town.

On September 8, 1685, the townspeople brought a suit against the Jewish lessees: Izcyk Shmuyl, Samson Shmuyl, Dr Danielew, Jacob Giec, and Mendel, Jona, and Moshe Shmuyl Dawid, charging that by being in violation of earlier contracts they were bringing injury to the town. [34]

The Jews brought a countersuit, and on 18 March 1686, King Jan III Sobieski ordered that no one disturb the Jews in their commerce, their shops, and their taverns, until the royal committee had reached a decision. In this order, the king also commanded that the Jews be allowed to maintain their customs and their court, as permitted to them by the laws of the kingdom. In 1688, a new dispute broke out on the matter of municipal leasing between the town and two Jews, Shmuel ben Chaim (Chaimowicz) and Leib ben Yitzhak (Izakowicz). King Jan III Sobieski ordered that a royal committee investigate the matter. These lessees complained that Piotr Woszczynowski and Alexander Truska, town government and city council members of Drohobycz, had signed a three–year rental contract with them for the period 1688–91, but that, without any explanation, the town government was conducting negotiations with other individuals. The committee was instructed to study the matter from the legal standpoint, discuss the issue with both parties, and make efforts to reach a compromise. [35] However, we lack information about the outcome of this dispute.

During the same period, on October 6, 1690, at the behest of the townspeople, King Jan III Sobieski forbade the Jew Liebermann, who had kept a tavern near the church, to distill brandy and beer, since his business violated the privileges of the town and brought damage to it and to the church. He ordered him to remove his tavern and ordered the town government to pay him compensation.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Jews were primarily employed in the sale of alcoholic beverages, in leasing, and in trade. Almost all the villages around the town were leased to Jews. In 1564, we hear of the Jew Jakub Judicz, a lessee of the salt mines and of propination in the town. After him, two other Jews became lessees. One of the most important lessees was Aron ben Yitzhak (Izakowicz), mentioned above. Toward the end of the seventeenth century, after 1683, the head of the community, Izak Józefowicz, leased the right for municipal propination.

In those years, the lessee Liebermann was involved in disputes with other Jewish lessees, when, behind the backs of the leaders of the community, he obtained an agreement with the starosta that granted him the lease for propination. Only thanks to the king's intervention was this matter dealt with according to the law. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, conditions changed to favour the Jews in many ways. From then on, the Jews expanded their activities in the town, taking over all commerce and industry, as well as most trades. Apart from leasing the town's monopolies, selling liquor, and distilling brandy and beer, they were involved in wholesale trade on a large scale, particularly dominating in foreign trade. Jewish merchants from Drohobycz came in great numbers to the fairs in Breslau, Frankfurt am Oder, Danzig, Königsberg, Leipzig, and other German cities. A wholesale merchant would consign his merchandise to traders or agents, who would travel as his hired representatives and sell within the city or its environs. The agents would also travel to fairs in other cities to sell the merchandise. These merchants were the pillars of commerce. Trade in salt from the Drohobycz mines was another important sector of the economy that was almost entirely concentrated in the hands of Jews. They brought the salt to Lwów, where they ran into stiff competition from Jewish salt merchants who were bringing salt from Bolechów and Kałusz to sell at a lower price. Thus, for example, during five weeks in 1621, 4,000 sacks of salt from Bolechów were sold at a price of one gold piece and six groschen per sack, while the salt from Drohobycz remained unsold because of its high price. However, Drohobycz merchants also sold their salt to other cities and to Wallachia (Romania).

Commerce in salt and the leases for the salt mines were in the hands of Jews in the eighteenth century as well.

[Page 15]

The trade in oxen, destined for sale in Breslau, was also concentrated in the hands of several Jews. The partners Yehoshua ben Shmue (Shmuylowicz) and Baruch be Elisha (Eliszowicz), Eliezer ben Arie (Leibowitz) and Eliezer ben Yitzhak (Izakowicz) used to buy herds of hundreds of bulls and cows and transport them to Silesia.

There were also wholesale merchants in cloth and fabrics in Drohobycz. One of them, Berko Meyerowicz, would buy and sell cloth for thousands of gold pieces. Another wholesaler, Wolf ben Jozef (Josefowicz), would bring large quantities of merchandise from Mogilew (in Belarus). Leib Leibowitz, who had capital of over 200,000 gold pieces, carried on an extensive trade with the outside world.

Drohobycz merchants also conducted large financial transactions abroad. In this regard, we know of Israel, the son of the Drohobycz rabbi Hersh ben Yaakov, who died during a visit in Dresden.

As a commercial center, Drohobycz attracted many Jews in Russyn and the population grew apace. By 1716, the number of Jewish families in the town had grown to 200. With time, all the commerce of Drohobycz and its environs was concentrated in the hands of Jews. In 1769, an official document noted that “the Jews include community leaders, merchants, shopkeepers, and artisans; the masses of Jews in Drohobycz, living in the town itself and in Łan, hold in their hands almost all sectors of commerce. They have settled within the Christian part of the town as well.” [36]

With the growth of the Jewish population, the number of artisans grew as well. In 1716 and 1717, there were a few Jewish tailors, three bakers, two goldsmiths, one tinsmith, one doctor, one furrier, one bookbinder, one jeweller, and one housepainter in Drohobycz.

In 1728, there were six tailors, three bakers, two tinsmiths, two goldsmiths, and two jewellers. Other Jewish workers, found in Drohobycz but not in other towns, were those serving the salt mines, such as clerks and lower officials working with the Jewish lessees.

Among the wealthy, there were also moneylenders. This was considered a profession. Some loaned only to Jews; others loaned to both Jews and Christians. For the most part, they would lend for bills of exchange or a pawn. Even merchants, who were not professional moneylenders, would make loans to invest their profits so that the money would not be idle. There were also moneychangers, who dealt with currency exchange. Since Drohobycz maintained trading ties with Hungary and Jewish traders would pass through various cities on their way to Hungary and Austria, they needed foreign currency. As Ber Birkenthal–Bolechower, [37] who accompanied his father on a trip to Hungary to buy wine, wrote: “… and we passed through the Jewish community of Drohobycz so that we could change Polish coins into Hungarian [38] and Austrian currency [39] coming from Hungary.” [40] They were helped by the famous and honourable Nagid (a wealthy elder), Rabbi Zalman Bejnat. [41]

As early as the seventeenth century, merchants and artisans, who had been well organized into various guilds as far back as the end of the fifteenth century, opposed the growing influence of the Jews in economic life. From the community chronicle, which is mainly devoted to the eighteenth century, we know of the existence of artisans' guilds, but we have no documents of bylaws for these organizations.

According to one document, dating to the period of the Austrian rule, there were long drawn out conflicts, as there were in other communities in Poland, between Jewish artisans and the Christian guilds that resulted from the stiff competition between the two groups. The Christian artisans wanted, if not to destroy the Jewish skilled trades, then at least to limit their activity by controlling the number of artisans. Unfortunately, we have no details on the actual background and the scope of this struggle and on the compromises reached and the compensation paid, as we do for other towns.

From the organizational and administrative standpoint, the Drohobycz community was included along with thirty–three other communities in the Przemyśl district council, but it did not join in paying taxes, apparently because the residents of Drohobycz were exempt from taxes.

The synagogue and the cemetery were already in existence by the beginning of the seventeenth century.

In 1711, the Jews received a permit to repair the synagogue from the bishop of Przemyśl, Jan Kazimierz. [42] In the 1720s, a fire broke out, and the synagogue burned down. After great efforts, a permit was received in 1726 from the bishop of Przemyśl Alexander Antony to allow the construction of a new synagogue on the same site, on condition that it would not be larger or more beautiful than the old one had been. The costs of construction were high; the Jews had to borrow sizable sums to meet them.

In 1733, the Jews received permission from the church to fence in the cemetery, in exchange for supplying windowpanes and carrying out various repairs to the Catholic church.

From an organizational–administrative standpoint, communal affairs were conducted as they were in the other communities in Russyn. From the minutes of the elections in 1717, we learn that heading the community council were two chief alufim (leaders), four parnasim (community workers), three tovim (respected people), three members of the community, and several financial committees with three to seven members.

[Page 16]

The following committees were in existence: a) synagogue fund (three to five members), b) Eretz–Israel collections (seven members), c) Talmud–Torah fund (five members), d) widows and orphans fund (four members), e) general charity collections (four to seven members), f) assessors' committee (thirty members), and g) rabbi, cantor and attendant committee (five arbitrators). Apart from this, the community elected two courts, each composed of six members. With the growth in the number of residents, the numbers of committee and community workers increased.

The Jews, who lived in the villages, were affiliated with the Drohobycz community and took part in its expenses. Their numbers grew over the years. By 1765, eighty–six villages belonged to the community.

Communal activities encompassed administrative and financial matters and judicial, religious and educational concerns, as in any community in Poland.

The earliest communal administrative committees known to us from documents are from the years 1664 and 1682. In 1682, the community council was composed of ten members: Icko Jozefowicz, Szmuyło Herszowicz, a son–in–law from Krynica, Icko Eysyk Majorowicz; Mendl Dawidowicz Przemyski; Leyzor Rubin Zelikowicz; Moszko Jakubowicz of Mościska; Szloma Berkowicz; Dawid Josoiwicz of Lublin; Uszer Aronowicz; Judka Zelmanowicz of Kracow. [43]

In 1682, the committee had only seven members: Izak Josefowicz; Abraham Moszowicz; Srul Dawidowicz; Srul Hajfer of Lwów; Matys Zelik Lwowski; Szymon Kru and Giecio Helclowicz. [44] According to the election by–laws, control remained permanently in the hands of the well off and the wealthy, the mine and propination lessees, and the wholesale merchants.

Over the years, there were several domineering people among the leaders of the community, who exploited their authority for their own benefit. One of them, Jona of Kropiwnik, made a ruling [45] naming himself “head of the leaders” for life. He exploited his position to effect a radical change in the method of election to further his schemes. Thus, in contradiction of the by–laws, two members of his family were among the four community heads elected.

During the period of his control, members of the community brought appeals against him to the Polish authorities. Despite these complaints, he succeeded in holding on to power, with the help of his family. His son Jehuda Leib was one of the heads of the community and his chief aide. He ruled with cruel severity, imposing taxes according to his whim, without considering the situation of the members of the community. After Jona's death in 1728, Jehuda Leib was chosen to head the community for the rest of his life.

The community also had an executive staff composed of rabbis, preachers, judges, slaughterers, and the scribe, who was the community's administrative officer and usually represented it before the gentile authorities. The community was involved in all the concerns of its residents: religious, economic, social, cultural, and educational. It fixed and collected the taxes necessary to cover its budget, which included salaries to the administrative staff, payments to government officials, the clergy, the municipality, and other direct and indirect taxes. It also collected general maintenance taxes, (100 gold pieces in 1738) and payments from weddings, funerals, dowries and honours.

Drohobycz was part of the council of the province of Russyn, and took an active part in its affairs. It used to send two representatives to council meetings. From a receipt of 1758, we learn that the community's representatives, who attended a province council meeting convened in Radom, received 640 gold pieces from the community for expenses. [46] The only ones on permanent salary were shtadlanim (lobbyists, representatives to the Gentiles) at the Sejm and community shtadlanim who were community employees.

It happened not infrequently that the community was at loggerheads with the leaders of the province of Russyn. In 1756, together with the Dolina community, it presented a complaint against the tax burden and the use of the leaders' power against the general good. Drohobycz representatives at the council of Russyn took part in the opposition against Dov Berisch, the son of the chief judge of Brody.

Relations between the community and the heads of the provincial council were rather tense and especially bad during the period, when Zalman ben Zeev (Wolfowitz) headed the council. After he was removed from office in 1758, relations deteriorated again when the community joined with Dolina and Rożniatów in a protest (15 April) against the provincial council of Russyn under the leadership of Berk Rabinowitz (son of the chief judge). According to the complaint, they used their authority only for their own benefit and oppressed the communities with a heavy tax burden. [47]

In the worst period of religious fanaticism in Poland, during the reign of the Polish king August II of Saxony (1697–1733), a blood libel trial was held (1718) against Adele, the daughter of the wealthy head of the Lwów community, Reb Moshe Kikenis. She was married to the son of a salt mine lessee in Drohobycz. Because the couple lived in Drohobycz, she was called Mistress Adele of Drohobycz. She conducted wide–ranging business affairs. Adele's gentile maidservant hid a dead Christian boy in her house on the night of Passover, and “confessed” to the priests that, at the command of her mistress, she had slaughtered the child for its blood, which the Jews needed for their Passover matzos. Because of this charge, Adele and all the Jews of Drohobycz were arrested. After cruel torture, Adele confessed that she herself had committed the crime, and that no other Jew was involved. The Jews were freed, and she was put on trial in Lwów. The trial was short, and she was sentenced to a cruel death. When the maid heard the verdict, she repented declaring that her confession had been false. She said that she had killed the child and named the Christian, who had incited her to do so. She was immediately removed from the courtroom and strangled in jail, since the priests did not want the details of the act to become known.

|

|

| Map of the Town of Drohobycz |

|

|

| Drohobycz: a general view |

|

|

| The City Hall |

|

|

|||

| The City Tower | The Gymnasium [High School] |

Despite this new confession, the judges were unwilling to reverse the verdict. The priests attempted to convince Adele to convert, promising that she would then be freed, but Adele refused to accept their mercy and courageously went to death, serenely accepting martyrdom. Adele was buried in Lwów. Her tombstone reads:

On Shabbat eve, the 27th of Elul 5478, the brave Adele, a holy and pure woman, daughter of our leader and teacher Rabbi Moshe Kikenis, was sentenced, sacrificed, and gave her life for all Israel. May God avenge her blood and may her soul be bound up in everlasting life.

The Jews of Drohobycz went through a difficult period in the middle of the eighteenth century, when they were ruled by Zalman Wolfowitz, the central personality of the town and one of the cruelest men in all Jewry in Russyn.

Zalman was born in Drohobycz in 1711. His father was a very poor furrier. [48] His childhood was passed in poverty until he obtained a job as a cashier in the salt mines. He lived licentiously and immorally and spent a great deal of money wastefully. One day in 1729, when the books were audited, a deficit was found. Zalman then gave poison to his supervisor, who died the next day. Zalman was arrested by order of the court and tortured, but they could not force a confession from him. A light sentence was passed; he received 100 lashes in the town square and was banished from the town. For a few years, he was a cashier in the salt mines in the neighbourhood of Sambor. There, he got into trouble with some Jews who prepared an ambush in the forests at Słopnice to kill him. They were not successful. Zalman brought charges against them. On 30 December 1732, the six Jews were sentenced to death, but through the efforts of the Jewish community, the sentence was mitigated. The instigator, Isak, was sentenced to one year in jail and a fine of 1,300 grzywna (1,000 paid to Zalman, 300 to the court). The rest of the accused received sentences of six months in prison. [49] Zalman succeeded in winning over Chomentowski, the district ruler of Drohobycz, and received from him the lease of all the incomes of the district and the salt mines in the area.

Chomentowski died at about that time. His wife, a young widow, who later married the starosta of Tarlo, [50] fell in love with Zalman, who was a handsome man. She supported him and leased to him her estates, salt mines, and the brandy monopoly in the villages and in the town of Drohobycz. At her initiative, the scribe of the municipality erased the 1729 sentence against him from the court records and Zalman was completely rehabilitated. Her love also helped him be chosen as head of the community.

The head of the community, Rabbi Chaim, had died at that time. On the intermediate days of Passover, the members of the community gathered in the synagogue to choose a new head. Zalman offered his candidacy. His rivals opposed him and interfered with the elections. The vote was interrupted. The following day Rychcic, the representative of the starosta Bielski, brought forty peasants armed with pitchforks and whips, and in their presence, ordered that the names of the other candidates be stricken from the list and that Zalman be chosen parnas and head of the community.

The Jews were terrified. Seeing that there was no point in opposing the will of the authorities, they elected Zalman head of the community against their will.

Two months after his election, Zalman began to take over the entire community. First, his son–in–law Shmuel ben Leib was named rabbi of the community. The Jews had no choice but to give in. Whoever dared to raise his voice against Zalman lost his livelihood and the right to live in Drohobycz. Zalman was revengeful, jealously pursuing power, and God help the Jew or Gentile, who didn't obey his desire and command.

He concentrated in his own hands not only the leases on the monopolies and the salt mines, but also all the wholesale trade in wine and iron. He imposed taxes (he himself paid no taxes!) and increased maintenance fees. He imposed all kinds of taxes and payments on artisans, oppressed and beat them mercilessly with rods, when they did not do as they were commanded. Whoever opposed him was punished with beatings; more than one was seriously injured. Detentions in the community jail were on the daily agenda, but all this did not concern Zalman. He was concerned only with accumulating power and wealth. The artisans' guilds were forced to keep constant armed watches in the marketplace and in front of his home and the homes of his family members to protect the treasury of the salt mines day and night. He didn't hesitate to steal community funds or to practice forgery and other kinds of deceit. In 1734, he lost the election; Dawid was elected community head. But in 1735, Zalman brought peasants with staves and pitchforks and forced the voters to elect him head of the community again. The Jews made complaints to the starosta's wife, but in vain. Chomentowska [51] confirmed the right of free election and gave order that new elections be held, but this order was only on paper and was not enforced. Zalman held on to power, but in the end, the community lost patience. In 1741, several Jews made complaints against him and accused him of forging the tax lists. Dawid Abusziewicz filed suit, charging that he had been seriously injured by Zalman; the same complaint was joined by Yitzhak Jósefowicz. Wolf Herszkowicz, called Boraczek, was seriously wounded by his brother–in–law Shmuel ben Jakob (Jacobowicz), who struck him at the instigation of Zalman. Suddenly all barriers split open, and the court was flooded with complaints.

[Page 18]

The community itself presented a complaint that excommunications had been imposed unjustly at his initiative. A few families filed suit, charging that he had stolen houses and businesses from them, and dozens of people complained about the tax burden. There were also complaints about embezzlement of community and public funds. But Zalman did not respond. On the contrary, on the days in which the trials were scheduled, he was absent from the town. He and his family members, who aided him in all his deeds, always found a trick to evade the deliberations of the court. Only his supporters and relatives were elected to the council. His son, Anshel Leib, was elected his second in command. His son–in–law, Rabbi Shmuel Segel, gave him loyal support. He was elected together with Zalman in 1746 as “leader and head of the province.” Their appointments were signed by rabbis of Lwów, Żółkiew, Tarnopol, and leaders of the communities in Brody, Tyśmienica and Kałusz communities. [52] The two of them participated in sittings of the provincial council and were authorized to sign its minutes. But Zalman was always the one to sign. In 1748, Zalman obtained an order from the province council, which announced a decision that if the leader of the province found himself in any community, he alone was authorized to make decisions concerning disputes between the community and private individuals or between the various villages and the community. The order also informed all the rabbis in Poland that Zalman, citizen of Drohobycz, was leader and head of the province, and that for that reason, he could settle disputes between the Drohobycz community and private individuals. Thus, it was forbidden for any rabbi or community to interfere with his authority. In this way, he dispensed with the possibility of appeals or complaints.

His behavior was also cruel to the Gentile townspeople and peasants. He put pressure on the municipality and forced it and even judges to bow to his will. It was forbidden to buy or sell housing in the town without his permission. He appointed mayors, village chiefs, and even guild leaders. He often beat people with whips, especially peasants who were forced to work in his fields, provide horses and wagons, and make all kinds of payments to him. The bakers had to buy his flour at whatever price he asked.

Over the years, his misbehavior and crimes passed all bounds. The matter blew up in 1752, when the town government lodged a collective complaint against Zalman and his family in the name of the Christian population in the town and the villages, as well as the Jewish community, and against Jakub Szmulewicz, a former salt mine lessee, concerning the leasing of the municipal right to propination. This case was also brought against the starosta's widow, Chomentowska. King August III set the dates for the trials, enjoined both sides to refrain from any disputes, and gave both sides safe conduct.

Zalman scorned the whole matter and carried on with his deeds. For example, he extorted a tax of fifty Hungarian gold pieces from the community, while an excommunication was handed down against his rival Jacob Shmuelowicz. Ignoring his letter of immunity, he seized him, beat him, and put him in prison. Jacob managed to escape after three weeks and fled to another town.

In the meantime, many complaints began to pile up. On 16 February 1753, the king appointed Leon Libiszewski and Ignacy Krokondo–Trepke as commissars and ordered them to investigate the situation. But again, nothing came of it. On the contrary, on this occasion, Zalman obtained a guard of twenty dragoons from the starosta of Przemyśl, who stood guard before his house to protect him from the wrath of the population.

In 1752, Zalman's affairs also involved the Council of the Four Lands, which assembled that year in Konstantinów. The Jews of Drohobycz brought a suit against the tyrannical parnas. However, for lack of time, the chief shtadlan Reb Szymon, suggested that the dispute be transferred for arbitration to a meeting in the Lwów district. The parnas of the Council of the Four Lands, Rabbi Abraham of Lublin, carried out the decision and informed the parnas of the Lwów district, Reb Izak Yissaschar Berisch, son of Reb Moshe Wolf, son of the chief judge (of Brody). [53]

In 1753, the dispute of the Jews of Drohobycz with Zalman came up on the agenda of the Lwów District Council, convened in Bóbrka under the leadership of Reb Berisch, the son of the chief judge. A delegation of five Drohobycz Jews, headed by the baker, Leib, appeared before the council. Leib described in detail Zalman's past, how he came to power with the help of his lover the starosta's widow Chomentowska, and all his misdeeds, crimes, and frauds. The leader of the province Reb Berisch, who himself was involved in many disputes with the people of his community in Brody, where he ruled firmly and autocratically, did not want to discuss Zalman. Most of the members of the Council viewed Leib's complaints as part of the dissatisfaction of the masses, well known to them. In their opinion, the masses were always dissatisfied and ready to complain at any opportunity about their parnasim and their leaders. Working from this assumption, they saw no justification for the complaints of the Jews of Drohobycz, since as far as they knew Zalman was totally innocent. Nothing was done, and the deputation of Drohobycz's Jewry returned home without obtaining a ruling against Zalman. [54]

In Drohobycz, Zalman, had already received a report on the deliberations at the session of the District Council from the Council's scribe, Józef Skałatski. He prepared an appropriate reception for the delegation. Reb Leib scarcely had passed the town's border, when he was seized by Zalman's mercenaries and brought to prison. A new phase of persecution, fines, and heavy taxes began. Whoever dared to oppose them was excommunicated by Zalman's son–in–law, Rabbi Shmuel ben Leib.

[Page 19]

Zalman behaved in a wild manner in this period and acted cruelly toward the citizens of Drohobycz, Dolina, and Sambor, both Jews and Christians. He didn't hesitate to put mayors and village chiefs in jail and punish anyone who did not obey his commands.

At this point, the patience of the entire population was at an end. On 29 August 1753, at the initiative of Mayor Jan Jachniewicz, the residents of the suburbs, Zawiezna, Liszniański, and Zadworna, united with the Drohobycz city government to defend the rights and privileges they had received from the kings and obtain justice in a suit, which they brought against Zalman. A complaint was presented in Warsaw, joined by the Jews of Drohobycz, Dolina, and Sambor, the lessees and sub–lessees of Stebnik, Kałusz, Czehryń, and Truskawiec. At a special assembly of Jewish representatives in Stryj, the Jews promised to cooperate with the Christians and make every effort to destroy Zalman. Since they had received no assistance from the Council of the Four Lands or from the district council, they chose to help themselves. [55]

On 12 April 1754, the Drohobycz municipality and the starosta, Maj.–Gen. Count Nosticz Rzewuski, received a royal decree, in which the king named commissars to rule in the dispute between Tarlowa–Chomentowska and Zalman on the one hand and the town of Drohobycz and the communities of Drohobycz, Dolina, and Sambor on the other. The committee arrived a short time after the decree was received. The town government recanted all its complaints against Chomentowska and turned all the accusations against the Jew Zalman, his son Leib, his son–in–law the rabbi, and the rest of the family. Two town council members, Piechowicz and Czernigowicz, of Stanisławów, inspected his account books. Based on this investigation, Zalman and his entire family were arrested. During the investigation, the matter of the poisoning of 1729 was reviewed. The Jews presented the community's books to the committee and revealed in detail the corrupt dealings and bribery at the time of the election of the rabbi, as well as the other frauds and misdeeds. The rabbi, his son–in–law, fled Drohobycz. Zalman and Leib also tried to break out of prison, but their escape was not successful. The commissars turned the matter over to a court composed of the starosta and the town judges.

On 9 June 1755, a judgment was delivered. Zalman was sentenced to death by hanging, and his son Leib was sentenced to receive 100 lashes with a rod in front of the town hall. All his property was confiscated to compensate the victims. Leib's son and his wife were ordered to have all their property, gold, silver, cash and jewelry conveyed, and were to be kept in jail until this was done.

In the ruling, Zalman was accused of making pacts with devils, witches, and magicians and in so doing, bringing great damage to Christianity, as well as concentrating in his hands all the power of Drohobycz in the office of the starosta. Everyone had been dependent on him and had brought him had brought him gifts. They had even conducted a court in his home and had shown him each decree in advance, making changes according to his command. He had demanded money for everything. All the artisans' guilds and village councils were forced to give him their money. The peasants worked his lands for nothing; trees were felled in the forests of the county without payment. He demanded special payments from anyone who purchased a lot of land or built a house on his farms and estates or in the town and its suburbs. Only after the payments were made, did he allow the documents to be entered in the town's record books. The residents were forced to drink brandy to ensure that his liquor would be sold. Whoever distilled brandy without his knowledge was punished with a large fine. Zalman himself paid no taxes, neither to the crown nor to the municipality. Half of the houses and all the stores in town were in the hands of his family, but the municipality was forced to pay the taxes on them.

Noting that in a free Christian republic one Jew had been able to oppress the Christian population, the court ruled that no punishment would be appropriate for him other than hanging and the confiscation of all his property for the benefit of the victims. On the Sabbath, 14 June 1755, the judgment was to be carried out, and Zalman was to be hanged in the town square.

Meanwhile, the masses gathered in the square. A scaffold had been erected in the centre. The court, together with the mayor and town council members were seated in their places. After a drum roll, the town scribe began to read the sentence. Suddenly, several Jews appeared and went directly to the town benches. They began to negotiate. The scribe ceased reading. The community's parnassim, Wigdor ben Ze'ev (Wolfowicz), Anszel ben Leib (Leybowicz), Wolcio Buynowicz, Oszja (Yehoshua) ben Moshe (Moszkowicz), Leyzor ben Leib (Leybowicz), and Abel ben Aron (Aronowicz) offered the municipality 500 red gold pieces (9,000 gold pieces) in exchange for commuting Zalman's death sentence to life imprisonment. After brief deliberations, the proconsul announced that the town government would be prepared to accept the offer, if the entire sum were paid immediately. Because of the sanctity of the Sabbath, they accepted pawns, which the Jews had brought with them: a basket full of gold objects, necklaces, rings, chains, pendants, and earrings. On the spot, the town scribe prepared a promissory note on behalf of the parnassim of the congregation and in the name of the families of Zalman, Yitzhak ben Hirsh (Herszkowicz), Leib ben Zelman (Zelmanowicz) and Jona ben Hirsh (Herszkowicz). According to the promissory note, they took upon themselves, in the name of the community, the obligation to present pawns worth about 500 red gold pieces to the municipality immediately after the Sabbath, thus sparing Zalman Wolfowitz from the hangman and commuting his sentence to life imprisonment. The money was to be paid in cash the following day. They undertook to meet the various claims brought by the Jews of Dolina and Sambor against Zalman. Zalman was to be imprisoned for life, and no steps were to be taken to free him.

[Page 20]

If Zalman did not conduct himself properly in jail, then the authorities were authorized to carry out the death sentence without a new trial. His son Leib's sentence of 100 lashes with the rod in front of the town hall was commuted.

The following day, the community's parnassim paid the money. Negotiations with the Dolina and Sambor communities continued for years on the demand of the Drohobycz parnassim that the other communities share in the payments made to the town government. The matter was also discussed in a sitting of the District Council at Brody and handed over to the Lwów rabbi for a decision.

Leib and Zalman's family left the town. Zalman remained in jail in Drohobycz. At the order of the judge Łopuski, he was given many comforts. He was even brought kosher food. Yet Zalman tried to figure out how to free himself. Even though his property had been expropriated, he and his relatives had managed to transfer some money to Tiacziw before the sentence was handed down.

Flight was impossible. Thus, Zalman decided to convert in exchange for release from jail. He made his conversion at the end of 1755, receiving the name Andrzej Wolfowicz. He was freed from prison but only to be transferred to the Carmelite monastery near the town. He attempted to flee from the monastery. His only ambition was to reach Tiacziw. Some of his Jewish adherents even tried to smuggle him out, but they were not successful. The number of his guards was doubled, and Zalman died in the monastery in 1757. He was buried beside the small church in the Zwaryckie suburb of Drohobycz. His memory was immortalized in Galicia in legends and, most especially, in Ruthenian popular song. In the Ruthenian Easter festivities (Hailka), young girls used to sing many songs about the life and cruel deeds of Zalman. Until 1914, the following song was sung in the area [56] of the Drohobycz hills:

|

Text of song [Polish]

1. Jede, jede Zelman

2. W sej koreti Zelman

3. Pomahaj bih Zelman

4. Każe klasty Zelman

5. Każe byty Zelman

6. Perebrau wże Zelman

7. Ne panuje Zelman

8. Na pohybel Zelman |

All Zalman's assistants and followers, who had run the affairs of the community with him, were dismissed except for Anszel Leibowicz. He remained head of the community for another few years and was also named leader of the province. Besides the 9,000 gold pieces that the community had to pay for freeing Zalman from the noose, it was forced to meet the financial demands of the Dolina and Sambor communities. The community recovered only 1,000 gold pieces from Zalman's property. For many years, the community was delinquent in its tax payments, and under heavy pressure by the authorities. The community sent the salt mine lessee Jacob ben Shmuel (Shmuelowicz) to Warsaw to explain to the authorities the sorry state that had resulted from Zalman's rule. This intervention at court cost sizable sums and led to disputes between the representative and the community, which did not reimburse him for his expenses.

Jacob Shmuelowicz, one of Zalman's harshest rivals, was chosen parnas after Anszel Leibowicz. In the latter half of the eighteenth century, Reb Hersh ben Jakob (Jakobowicz), one of the richest people in town, and Reb Yisrael ben Zvi (Herszkowicz) served as rabbis. The community was plagued with debts that dated as far back as 1716. Installment and interest payments rose to 10,000 gold pieces; 50,000 gold pieces were owed to the Carmelite order in Sambor alone.

By 1741, the debts had risen to 90,000 gold pieces, of which 50,000 were owed to the Jesuit order in Sambor, 11,500 to the Carmelite order, 2,000 to the Dominicans in Lwów, and 3,000 to the church in Felsztyn. [57] The community had trouble paying the interest, for which purpose, it had to resort to taking new loans. The countless court cases which were undertaken also involved great expense.

In 1716, it had been decided at a general meeting of the entire community to raise the existing taxes and impose indirect taxes of twenty gold pieces on every 100 pieces, 10 percent of the value of gold and silver objects and jewelry, 5 percent on apartment houses, and 3.1 percent on simple homes. A special committee took evidence under oath from everyone about his or her economic situation and property. But the sums mobilized in this fashion were not sufficient to pay the debts.

[Page 21]

When the situation became worse in 1733, it was decided to raise taxes once more. In 1738, the community decided to impose a special tax (koropka) on all items of commerce and on all craft sectors. The tax burden rose, especially during Zalman Wolfowitz's rule.

In 1752, the budget showed revenue, including loans, of 15,652 gold pieces and expenditures of 18,768 gold pieces. That did not include debt payments, the rabbi's salary, and such tax payments as the yeverna, a head tax totaling 2,200 gold pieces.

Thus, it isn't surprising that the community's financial situation in those years was disastrous, even before considering the serious effects of Zalman Wolfowitz's rule on the community's financial situation. In 1754, the community owed 121,574 gold pieces, 89,174 to the priests, and 32,400 to the noblemen. [58] We can see how heavy the tax burden was by examining the communal records from the 1750s. [59] As well as direct taxes, there was no consumer good or food item that was not taxed. [60]

From the tax lists in the communal records of 1753, we can determine the occupational composition of Drohobycz Jewry in that period. Jewish breadwinners were divided according to occupation into eight categories: a) lessees and tax–collectors; b) bankers and money–changers; c) wholesalers; d) tavern–keepers and innkeepers; e) retailers and traders; f) middlemen and apprentice traders; g) religious functionaries; h) artisans.

The first group, lessees and tax–collectors, included: a) lessees of the town's mills; b) mead distillery lessees; c) road tax lessees; d) municipal propination lessees; e) salt mine lessees, and salt merchants.

Bankers and moneychangers: as cited above, eighteenth century Drohobycz was an important commercial transfer centre with Hungary. Associated with this trade, capital transactions of three types occurred: a) loans with interest; b) pawnbrokers to Jews and Christians; c) money–changers.

There were fourteen types of wholesalers. They were headed by: a) wholesalers, who traveled to the fairs in Breslau, Frankfurt am Oder, Rawa, [61] and Danzig, bringing back wares to sell in Drohobycz. It is interesting to note that during this period the Drohobycz merchants were the only traders from Poland who came to these fairs; b) wine merchants, who brought wine from Hungary or from other towns to sell in barrels. Hungarian wine was also purchased from wine merchants in Stryj, the best–known merchants of Hungarian wine in Poland; c) wholesale merchants who dealt with the lands across the Vistula (Germany) and brought back iron, plowshares, and all types of iron implements; d) merchants bringing implements from Bohemia and Italy, such as sickles and roofing nails; e) poultry dealers; f) linen merchants, and those importing linen from Danzig; g) dealers in women's fabrics from France and silk goods; h) grain merchants; i) leather merchants; j) horse and cattle merchants; k) salt fish wholesalers; l) wax wholesalers; m) gold and silver merchants; n) harness merchants.

The fourth category, tavern–keepers and innkeepers, included: a) innkeepers who distilled their own beer and sold liquors, beeswax, [62] and mead; b) grain syrup merchants; c) sellers of wiśniak [63] or cherry whiskey in jugs; d) innkeepers who also dealt in oats. [64]

The fifth category, retailers and traders, included: a) sellers of salt by the pound; b) sellers of salt fish in the town square; c) sellers of plums, small nuts and Italian nuts; d) sellers of goat cheeses; e) grain sellers; f) sellers of wax by the pound; g) sellers of linen; h) sellers of shoes; i) sellers of leather; j) sellers of lead, sickles and roofing nails.

The sixth category included: a) salt mine clerks; b) middlemen.

The seventh category, religious officers included: rabbis, judges, preachers, slaughterers, teachers, synagogue attendants, tutors.

The eighth category included artisans: by the agreement of 1664, Jews were permitted to deal only in merchandise that would not compete with the Christian craft guilds. But the Jews paid no attention to this regulation. Jewish artisans worked in the crafts that supplied the needs of the Jewish population. From the start of the Jewish settlement until the eighteenth century, the number of Jewish artisans was relatively small, but from the seventeenth century, Drohobycz became an important center for Jewish artisans who distributed their goods, especially furs and jewelry, throughout Russyn and beyond.

In the 1765 census, Drohobycz numbered six bakers, six doctors, seven goldsmiths, sixteen tailors, four furriers, three dyers, one tinsmith, one bookbinder, two jewellers, a barbr/barber–surgeon, and several musicians.

In the mid eighteenth century, there was a wealthy group among the artisans, who paid substantial taxes. According to the koropka list of 1742, tailors paid two groschen for every gold piece of profit. Traveling tailors, who worked in the villages, paid three groschen for every gold piece, tinsmiths paid four groschen. Jewellers, who worked their own raw material, paid three gold pieces for merchandise worth 100 gold pieces. Jewellers, who worked raw material belonging to others, paid four groschen for every gold piece of their wages.

[Page 22]

Artisans paid two to four times more than merchants. There was a difference in payment between those artisans who worked independently and those who worked for others,

As a commercial centre, there was great occupational variety in Drohobycz's Jewish population. But this list does not reveal the differences among those Jews working in trades and those who were labourers and wage earners. One must assume that there was great diversity in this stratum too.

The masses were not always happy with the communal rulers. For the most part, they did not like them and made their dissatisfaction known. It is true that we only know of only one case of an attempt to rebel against the rulers of the community, but this is because of the lack of documentary evidence for similar cases. In 1770, an excommunication was declared in the synagogue against Avigdor Herszowicz , on the grounds that he had incited the masses against the leaders. Because of this excommunication, he was barred for life from any communal job or position.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, the Jewish community had become large and stable from a socio–economic point of view. The houses in the center of town belonged to the Jews. The crises during Zalman's rule had passed and were quickly forgotten, and the community resumed its normal functioning. It even managed to pay off a sizable part of its debt, to the point that the total had fallen to 26,968 gold pieces by the time Galicia was annexed to Austria. In 1765, in the last census under Polish rule, there were 1,923 Jews in Drohobycz and its dependent areas. In the town itself, 979 Jews paid the head–tax. Jews owned 200 houses, mostly built of wood. In this period, Rabbi Reb Naftali Hertz served as rabbi and chief judge.

In 1769, many Polish soldiers passed through Drohobycz and camped in the town. They forced the population provide lodging, food, fodder and beverages. According to the starosta Wacław Rzewuski's order, given by his son Józef on July 20, the burden was distributed among the population according to the following formula: one third of the expenses were to be covered by the Christians, one third by the villages and one third by the Jews living in the town and in Łan. To ensure a fair distribution of beverages, food, and fodder, the Christians and the Jews each chose two officers who were sworn in by the town government. [65]

We do not know to what degree confusion and disorder was brought upon the Jews of Poland by the Sabbataean [66] movement and how Frankism [67] affected the Jews of Drohobycz. The existing sources relay no details whatsoever on this matter. However, the khasidic movement did penetrate the Jewish community. Rabbi Izak of Drohobycz was one of the earliest of the khasidim. His father, Rabbi Yosef was a man of truth, and was called by the people Safra Viedliver. Yosef was a follower of the Baal Shem Tov. In his old age, he immigrated to Eretz Israel and sent his son a khumash [68] from there. His mother was called Yente, the prophetess.

Rabbi Izak was a moralizing preacher in Drohobycz. At first, he opposed the Baal Shem Tov [69] and his teaching, because he wrote amulets. [70] But despite his opposition, khasidic legend tells that he secretly admired him. We know how much he admired and honoured the Baal Shem Tov from the legend that tells how he went to the Besht and became one of his followers. One night, Reb Isaac was unable to sleep. He knew, therefore, that he had committed a sin and that he had to repent before he could sleep. He considered all his deeds and found no sin, apart from having kept his silence and made no protest when he had been in the company of mockers who made fun of the Besht. He immediately went to the Besht, made peace with him, and became one of his intimates. From that time, he became one of his most faithful pupils.

After joining with the Besht, Rabbi Yitzhak Drohobyczer went to Ostrava, [71] and became one of the ten batlanim, [72] and later a moralizing preacher at the bet hamidrash [73] of the well–known magid [74] Yózef Yózefa ben Shmuel Yelkish (d. 1762). For while he lived in Brody and befriended the head of the yeshiva Rabbi Yitzhak Hamburger. He was later a moralizing preacher in Horochów, [75] and once more in Drohobycz. He died in Horochów. [76] His son was Rabbi Yehiel Michael, the preacher of Złoczów , among the most outstanding pupils of the Besht. [77]

Among the first khasidim in Drohobycz, one should also mention Rabbi Yosef Drobyczer (Ashkenazi), father of Rabbi Israel Nachman Drobyczer, [78] who was rabbi and judge of the tailors' society in Ostróg [79] and later judge and rabbi in several towns in Poland and Germany. At the end the eighteenth century, he went to Italy and traveled widely there. He was a native of Stanisławów, and sympathized with the khasidim. He, his wife, and his family emigrated to Eretz Israel and settled in Safed in 1804. In 1807, he traveled abroad to publish his books. He left again in 1813, living for a few years in Livorno. He spent his last years in Eretz Israel. There were not many khasidim in Drohobycz in the eighteenth century, and their influence was not felt in communal life. The influence of the khasidim began to be important only in the nineteenth century.

In 1772, Russyn was annexed to Austria, and Drohobycz became an Austrian city. This political event brought change in all areas of daily life. First, the Austrian administration, which was sent to Russyn, known as Galicia after 1772, had a colonizing mission. Through a series of orders, laws, and decrees, they tried to erase the area's past and turn it into an imperial province, just like the other crown lands within the Hapsburg monarchy.

[Page 23]

From the very beginning of the Austrian rule the administration viewed Drohobycz as a city. Right after the conquest of Galicia, Drohobycz was faced with an important problem. Its solution influenced its economic and financial existence.

As a royal city, Drohobycz, like other cities with the same status, benefited from special attention from the bureaucracy. Unlike other cities, in which the municipal government during the Polish era held monopoly rights to propination, in Drohobycz, Sambor, and Stryj, the starosta, the king's legal representative, leased out this monopoly, mainly to Jews, through agreements reached with the municipality, at times voluntarily, at times by force. Since these agreements had been made many years before, the municipalities showed no concern about the manner of leasing or about who was getting the income. The Austrian authorities declared immediately that these rights be returned to the cities. Acting on their advice, Drohobycz sued the treasury and the lessees, demanding the cancellation of the contracts and the return of the monopoly to the city. The city won the case, thereby gaining the possibility of an annual income of 5,000–6,000 gold pieces. Naturally, this change seriously damaged the vital interests of the Jews. Furthermore, the officials disregarded the fact that the majority of the city's residents were Jews, the very Jews whom most of the bureaucrats viewed as smugglers, swindlers, and thieves.

From an administrative standpoint, Drohobycz belonged to the Sambor district. Changes in the internal affairs of the Jews were initiated as well. According to new legislation regarding Jews, promulgated by Empress Maria Theresa in 1776, the Jews of Galicia were to be governed by a new organization. The Generaldirektion der Juden, the chief executive council of the Jews of Galicia, stood at the top of a hierarchical order that included all the communities, each led by six to twelve parnassim (community leaders).

The communities in the Drohobycz and Sambor districts were under the direction of the district parnassim (Kreisältester), over whom six provincial parnassim (Landesältester) were in charge, headed by the provincial rabbi. Six district parnassim and six provincial parnassim, together with the provincial rabbi at the head, constituted the chief executive council of the Jews of Galicia and were responsible for all Jewish concerns.

This body was eliminated in 1786. No province–wide body was set up in its place; only the local community parnassim remained in office. Except for Lwów and Brody, each headed by a directorate composed of seven parnassim, all the communities (including Drohobycz) were run by committees composed of three parnassim. Their functions included: representing the community before the authorities; caring for the poor in the community; supervising, together with the community rabbi, the registration of births, marriages, and deaths; collecting the community tax; collecting the Jews' taxes; and running all communal matters. The parnassim reported to the district authorities and were under their control.

The authorities investigated what taxes and payments had been imposed on the Drohobycz community and its members and then approved the community rabbi and parnassim. [80] In the meantime, economic problems arose which worked to undermine Jewish life. In Austria, unlike Poland, the trade in salt was a government monopoly. The authorities took control of all trade in salt and established an office for the sale of Galician salt (Direktion des galizischen Salzverschleisses).

Except for the large mines at Bochnia and Wieliczka, they took over all salt mines, including those in Drohobycz, together with the salt–water springs, from which refined salt and distilled salt (Sudsalz) were produced.

Just after the annexation of Galicia, Shlomo David, a Jew from Breslau, and Ze'ev Moshe Heymann of Prussia, attempted to obtain from the director of the salt monopoly the right to sell Galicia's entire salt production, whether from the mines, the springs, or the refineries. In fact, Shlomo David succeeded, after negotiations with Vienna, in attaining the right to purchase salt for a total of two million gulden but he was not allowed to obtain a lease for mining salt. [81] In Drohobycz itself, several Jews received the right to sell salt from the board of the monopoly. But the government's concentration of salt production hurt many Jews, and over the course of time, even those few Jews who had received the right at the beginning of Austrian rule, lost it.

The most important salt refinery in Galicia was Drohobycz, with branches in Hucisko, Stebnik, and Solec. [82] Fifty thousand hundredweight (each about two kilograms) of refined salt were produced each year in these refineries. They brought almost 180,000 florins into the treasury each year.

Besides salt, the government began to be interested in another type of mineral resource. As far back as 1772, in Słoboda Rungurska in Pokocja [83] several Jews began to exploit a type of oil found beneath the surface. From this material, which was petroleum, although this was not recognized, the Jews produced grease for wagons and for leather. Near Drohobycz, where petroleum was later discovered, the residents had noticed that a kind of earth–oil would seep up from the ground. The peasants used it to make grease for wagons and shoes and a type of varnish.

[Page 24]

The peasants paid two florins and fifty kreuzer for each hole they drilled to dig this oil. [84] The first attempts to strike oil were made in 1810 near Borysław by a Jew named Hecker, [85] but without positive results. More than half a century passed before it was successfully shown that these lands were indeed rich in petroleum. We have detailed information as to the degree to which Jews exploited this resource and concerned themselves with the production of grease for wagons and shoes. [86]

In the meantime, the city, which had won its suit to regain its right over propination, was making major efforts to obtain recognition for the privilege de non tolerandis Judaeis, so that it could drive out the Jews from within the city. In fact, it succeeded. At first, the municipality requested in 1780 that its [Christian] citizens be given back the homes that once belonged to them and now were owned by Jews. [87] In October 1783, the city's representatives, Piechowicz and Anton Hisowicz, turned to the authorities with the request that the Jews be made to evacuate the city immediately and to move to their quarter Na Łanie, where they had been given permission to live in the past. In addition, they asked that the Jews be prevented from carrying on any commerce or sale of brandy in the city. The government replied that after studying all the city's privileges, it would decide to what extent the implementation of these demands would be legal. [88] In November 1783, they sent to Vienna for all the documents concerning the privileges of Drohobycz. But even before this request, the above–mentioned representatives asked that an order be given that elections to the city council be held only in the presence of the district governor and without the participation of the Jews. [89] On 3 April 1784, the government ruled that the city council elections be held under the supervision of the district commissar in the presence of the area officer, and that Jews be excluded from the elections. [90] During that period, the privilege de non tolerandis Judaeis was renewed, and at the start of 1784, the Jewish community was ordered to leave the city, sell their houses, and settle only in Na Łanie. [91] This order, carried out punctiliously and with severity, caused the economic collapse of the Jews.

Regarding the evacuation, the beverage–tax lessees Aba ben Zalman, Moshe ben Israel and Zeev ben Leib, demanded return of beverage taxes paid as advance payments by Jewish tavern keepers or paid illegally. After extended negotiations, the Jewish community and the municipality reached an agreement. This was the Vienna Agreement which stipulated that payments of more than forty–five kreuzer per barrel of beer be returned. [92] Advance payments of a total of 3,573 florins and seven and a half kreuzer were invested in a public trust as the capital of the Jewish community in Drohobycz. The profits were used to cover the expenses of the community. In 1787, the government agreed to use the interest from this capital to pay the community's debts from the Polish era. [93] In the same period, the community asked the government to order that 15,000 florins be paid to it by the heirs of the last starosta, General Rzewuski. [94] On 9 December, they sent to Vienna for the documents, but we do not know to what extent the community's demand was complied with and whether this money was returned. The municipality also made efforts to eliminate the rest of the lessees, such as Shmuel Majerowicz, lessee of the flour mills, but in this instance the municipality failed.

Despite the decree that they evacuate the city and give back their houses, the Jews of Drohobycz did not despair. A few weeks after the authorities' decision was announced, the parnas Izak Benyamin made a written appeal on behalf of the community that the Jews be allowed to keep their houses and conduct commerce. In November 1784, the central authorities in Vienna ordered that the Jews be protected against all prejudices. [95]

But the Jews still faced a difficult struggle for the right to live and own property in the city. The Christians, the earlier owners, broke into the homes and forced their Jewish owners to leave. The authorities were flooded with complaints from Jews evicted from their homes and requests that they be allowed to conduct their businesses or trade.

The head of the community Izak Benyamin, who represented the community to the authorities prior to the Austrian conquest, [96] carefully examined and worked diligently on every case. For example, in November 1784, he reported the humiliating incident of the Jewish tailor Cymel Berkowicz and two wealthy merchants, who were turned out of their homes and whose merchandise was thrown into the street. In the name of the community, he requested that the sale of the houses be stopped and that the situation be reexamined. [97]