|

|

|

The Children Transport

The rabbi arrived safely to Prague but was very disturbed by the entire incident in Warsaw. Indeed, it was difficult to perceive, for a man raised in democracies, what was happening to the few remaining Jews in Poland. He imagined the life of the Polish Jewish survivor without special guards like himself. The incident stimulated his desire to helpthe Jew especially the Jewish child. Waiting for him at the station was Elfan Rees, UNRRA's Prague representative. Rees delivered the bad news. The Czech government had cancelled all agreements granting the children Czech entry visas for their six–week stay in a Deblice camp outside of Prague. The decision also affected all Czech–Polish borders. Hundreds of Polish Jews who reached the border crossings were told to stay on the Polish side.

|

|

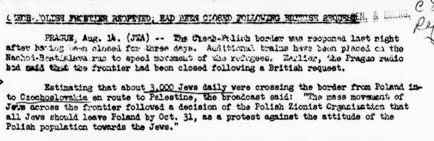

| Czech Polish Frontier Reopened: Had Been Closed Following British Request |

The document is difficult to read. The news comes from Prague, dated August 14, by the Jewish Telegraph Agency. The item states that the Czech Polish border has been reopened last night after it was closed for 3 days. The report further quotes the Czech radio that stated that the borders were closed following a British request. According to the Czech radio, it is estimated that about 3,000 Jews were crossing daily into Czechoslovakia on their way to Palestine. The mass movement of Polish Jews across the frontier followed, a decision of the Polish Zionist organization that all Jews should leave Poland by October 31, as a protest against the attitude of the Polish population towards the Jew.

The reason for the border closures was not the British request although Britain asked the Czechs to close the borders. The simple reason for the Czech actions was money. Rees told the shocked rabbi that UNRRA owed the Czechs millions of korunas for providing housing, food and medicines to Jewish refugees and had been very slow in reimbursing, apparently a planned program to reduce the number of Polish Jewish refugees entering Czechoslovakia . At the time, the Czech cost of housing the Jewish refugees was running $100,000 a week, and that was only for the transients' brief stay in a transit camp on the way to Germany or Austria. Unless UNRRA came up with the money, the rabbi was told, there would be no further Czech help. This reasoning was apparently not explained to the rabbi, but observers believe he probably realized that the British were behind the UNRRA tactics.

Clearly, thinking the rabbi had influence with UNRRA, the US government, and Jewish American organizations perhaps, Rees took the rabbi by the arm and explained that members of the Czech government were waiting to discuss these matters.

When the rabbi met with Czech Foreign Ministry officials, he was told that if he deposited a check to cover any costs arising from the transport and the children's six– week stay in the DP camp outside of Prague, then the children would be allowed into Czechoslovakia. The rabbi explained that even if he had the cash in his pocket, it was not his, and he had no authority to turn it over. He added that, legally, he could not even sign any guarantees of payment. UNRRA had to be trusted to cover the cost of the children's stay as they did for all refugees.

Herzog also learned from Rees that even the JDC would not guarantee UNRRA's payment, since such a guarantee would set a precedent that the JDC would have to honor all over Europe. To make matters worse, the rabbi was told that the Czech government was planning to close the borders to Jewish refugees. If that happened, the children stuck on the train would have to return to the orphanages. Rabbi Herzog saw all his hard work and plans unraveling before his eyes.

Rabbi Herzog met with Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk who strongly advised him to meet with Deputy Prime Minister Klement Gottwald, leader of the Czech Communist Party. Gottwald was someone with tremendous influence within the Czech Government, since the Communists had won 31 percent of the vote in the 1945 elections. Gottwald, who spent the war in Moscow, would be appointed Prime Minister in 1948, after the Czech Communist seizure of power. Gottwald granted Herzog the interview. Accompanying Rabbi Herzog to meet Gottwald were two Jewish Czech parliamentarians, one of them was Frisher. Doctor Rizik also joined the group that entered Gottwald's office, where they were greeted cordially. A persuasive speaker, perhaps from his legal training or well–honed diplomatic skill, the rabbi made his case. The rabbi pointed out to Gottwald that Czechoslovakia had an age–old and highly–respected history of ethical behavior and helping those in need. The rabbi told Gottwald that while he had seen a tragic decline in morality, Czechoslovakia had not sunk into the morass of brutality and murder like other European countries, but kept a high standard of enviable behavior. And except for a few isolated instances, the Czech borders had remained open to hapless Jewish refugees. The rabbi also raised the painful issue of the Holocaust and the fate of the desperate Polish Jewish survivors now gathered at the border. Anti–Semitism was still a threat to Jewish life, explained the rabbi, reminding Gottwald of the Kielce pogroms that had resulted in the death and injured Jewish Shoah survivors. The children's lives were in danger every moment in Poland. The rabbi told the deputy prime minister of an impending meeting in Warsaw with LaGuardia, the head of UNRRA, and assured Gottwald that at that meeting he would raise the issue of UNRRA's financial obligations to the Czech government concerning the Jewish refugees. The rabbi explained that he had French entry permits for the children, and assured Gottwald that the children were not going to stay in Czechoslovakia one day longer than they had to, six weeks needed until the French facilities were ready. Gottwald listened to the fiery rabbi give his impassioned plea, and decided on the spot to grant the children entry visas into Czechoslovakia[1]. He instructed the deputy Minister of the Interior, Zdenek Toman, who was in charge of the borders, not only to issue the visas, but also to absorb any costs for housing the children at the Deblice transit camp on the outskirts of Prague.

While Rabbi Herzog was running about Prague, the UNRRA office finished the plan of transporting the Jewish children out of Poland. The plan, entitled “Transport 750,” was given directly to a member of the Vaad Hatzala and the liaison officer between UNRRA and Rabbi Herzog. The document was in Rabbi Solomon P. Wohlgelernter's hand by August 19, 1946. The UNRRA plan anticipated 750 children would be on board the train. Wohlgelernter placed a call to Rabbi Herzog in Prague and to Rabbi Kahana in Warsaw, informing them of the latest news.

|

|

The UNRRA “Plan 750” listed 750 youngsters plus escorts even though permission had been granted for 1,000 orphans and yeshiva students.. But because of the logistical difficulties only 750 were chosen initially. Plan “750”was very detailed and appeared to cover all eventualities. The large 44–car train would begin loading children in Lodz, Poland, then proceed to Katowice where the majority of the children assembled from the different orphanages would board the train. The train was to arrive in Prague, Czechoslovakia on Friday, August 23, 1946.

The UNRRA document listed the leaders of the various organizations that would be on the train. The Polish government was represented by Wanda Siwek, of the Polish Repatriation office. A Major Sokol would be in charge of security. Dr. Alfred Kalmanowicz was in charge of the medical issues. The Va'ad Hatzala was represented by Rabbi Simcha Wasserman , Mrs. Recha Sternbuch, and Rabbi Solomon P. Wohlgernter. There was, however, one serious flaw in the plan, namely this train with the children was only going to Prague where the children would find that there was no proviso for transportation out of Prague. The children would have to stay in Prague for six weeks until their housing arrangements were completed in France. Rabbi Kahana's office worked feverishly, removing bureaucratic and physical obstacles in order to get children out of their orphanage to the railway stations. Kahana coordinated all of these activities from his office at the Association of Jewish Religious Communities in Warsaw. Group tickets had to be purchased in advance so that the various groups could reach their assembly point. The safety factor was very important when dealing with Polish trains that were frequently ambushed by Polish officials and Jews were killed. Also the children train would have to be protected as it traveled through Poland.

Rabbi Kahana had to make instant decisions. He was notified that the Polish train would arrive on August 21, 1946 at the Lodz railway station where boarding would commence at once. In view of the short notice time allotted, hurried arrangements had to be made. Rabbi Kahana sent word to the different orphanages to organize the children and make for the main train station in either Lodz or Katowice according to the assigned station. The orphanages were also instructed to provide the children with extra food rations for the trip. Rabbi Kahana dispatched Captain Yeshayahu Drucker to Lodz to supervise the loading of the train there.[2] Drucker arrived in Lodz on Wednesday with Rabbi Aaron Becker, just in time to greet the children that arrived at the railroad station. Drucker made certain that the Lodz boarding proceeded according to plan.

The plan called for the train to start in Lodz and proceed to Katowice, a distance of about 168 kilometers. The next day, the train would leave for Prague.

|

|

| The train would then travel from Katowice, Poland to Prague, Czechoslovakia |

On August 21, 1946, all the Jewish children boarded the train that left the city of Lodz at 10 P.M. heading to Katowice, where it arrived on Thursday morning, August 22, 1946. It was parked at the freight terminal where boarding began.

|

|

| Jewish orphans arrive at the train station in Lodz |

|

|

| Jewish children waiting to board the train |

|

|

| The youngest passenger aboard the train. |

Meanwhile Rabbi Herzog was in Prague closing all points of dissension with the Czech government officials. He still lacked UNRRA's permission to enter the refugee camp in Prague. Negotiations throughout the day proved fruitless. Next morning, Rabbi Herzog, accompanied by his entourage, boarded an UNRRA plane provided for him by UNRRA's chief Fiorello LaGuardia, and flew to Warsaw.

The meeting between Rabbi Herzog and LaGuardia took place at the Warsaw UNRRA office. LaGuardia denied Rabbi Herzog's claim that the Poles were persecuting Jews. As a matter of fact, he said, the Polish government was doing its utmost to ensure Jewish life in Poland. Rabbi Herzog replied that there was no difference between the government and the masses. The masses had carried out the Kielce pogrom, right in front of a powerless government, and shattered the fragile postwar Jewish existence in Poland. The rabbi argued that Jews were fleeing Poland primarily for their own safety.

LaGuardia then announced his game–changer. Polish Jewish refugees, LaGuardia said, could no longer be classified as refugees since they were not endangered by governmental actions. Since they were not threatened by the Polish government, they were not entitled to UNRRA assistance, earmarked only for persecuted refugees.

LaGuardia unintentionally revealed that his unusual interpretation of the word “refugee” was one used by both Britain and the United States– namely Jews who returned to their native homes and being threatened are not entitled to any help.

But Herzog was also an attorney and knew that according to UNRRA's own definition, a refugee was a person who feared for his or her life due to changing political conditions. Using that interpretation, these Polish Jews and other Jews from Eastern Europe had fled for safety.

Herzog pointed out that the Jews fleeing Eastern Europe were afraid for their lives, fleeing to stay alive, and thus should be considered refugees. The rabbi told LaGuardia he firmly believed these Jewish refugees' lives were in danger from the very real Polish anti–Semitism. He reasoned that according to this interpretation Jewish refugees were indeed entitled to UNRRA help.

Jewish Holocaust survivors were running for their lives, the rabbi told LaGuardia. Not only had they survived the Holocaust, he said, but just look at the Kielce pogrom and similar pogroms on a smaller scale that took place in other Polish and Slovak cities, and could LaGuardia please explain how the Jews were safe in Poland.

LaGuardia was already under a great deal of pressure from American Jewish organizations, regarding UNRRA's refugee policy. He admitted to the rabbi that he was on thin ice with the definition favored by Britain and the United States. Then, perhaps persuaded by the rabbi's arguments, LaGuardia seemingly backtracked on his own statements. He promised to work on changing the present reality Jewish refugees faced. Meanwhile, he said, UNRRA would notify the Czechs that UNRRA would approve the children's stay in Prague's Deblice transit camp. Finally Rabbi Herzog had permission for the transport to proceed. It was already late in the day.

He managed to fly to Katowice where his transport was sitting all day. The rabbi reached the train station and boarded the train that started to roll towards the Polish–Czech border, traveling at about 30 km per hour, the normal speed for Polish trains at the time. It was nearly midnight when the train slowed down as the border approached. Some of the passengers on the train were stowaways who had snuck on hoping to get out of Poland without the necessary papers. This was a tricky proposition fraught with danger. A stowaway could be arrested and imprisoned, with no hope of ever getting the necessary papers to leave Poland. As the train cruised to the border station one of the stowaways, a teacher from one of the orphanages who had inserted herself in with a group of children lost her nerve. She must have been getting steadily more frightened with each kilometer the train covered, getting closer and closer to the border. First she moved out of the compartment where she'd been sitting with the children from her orphanage, and then in the corridor slowly made her way towards the door. The children she'd been with who considered her their foster mother wouldn't leave her side. When she got up, they got up, when she moved to the door, they moved to the door. She could not convince them to go back to the compartment. Suddenly, the pressure was too much. She pulled open the door and jumped from the very slow moving train. The problem was some of the children jumped with her. Polish border guards saw them and rushed from their posts, surrounding the children as the train came to a full stop. More of her students jumped down from the train crying “This is our mother. Our mother died, and now she is our mother. You can't take her away.” But they did.

The locomotive was still churning when another unpleasant surprise came. The Polish border commander, seeing the scene, boarded the train and painstakingly checked the passenger documents, compartment by compartment, car by car. Even though the children were traveling on group visas, the process seemed to take forever. Minders from the different orphanages had lists of their children, a body count, and the French entry permits. The border guards rifled through the papers, keeping count as they moved slowly from compartment to compartment. When the inspection finished, they approached the Rabbi with the bad news. There were 10 more adults on the train than on the travel manifests. The latter called for 500 orphans and 101 escorts.. But somehow there were now 111 adults. Until the situation was resolved, the Polish military commander refused to let the train cross the border.

The Rabbi's people asked for a recount. Perhaps the border guards had made a mistake? Once again the guards went through the cars, counting and recounting. Hours clicked by. Hours crept by until the border guards finally discovered the extra passengers. They located 10 women, one, the mother of a nine–year old child from one of the orphanages, the others were relatives or friends of the children aboard the train[3]. Screaming and crying for help from the Rabbi or anyone who would listen, the women were forcefully removed from the train.[4]

|

|

| A page entry by Lea Lederman in her notebook regarding the trip of the Children train |

The entry is in Polish. Lea describes the departure from the city of Bytom on August 22, 1046. Her orphanage was located in Bytom. They traveled to Katowice where they boarded the children's train. They discovered a mother aboard the train without a passport and made her leave the train. All pleas were ignored. The train then continued to Ostrava Moravska where she stayed Saturday at the Palace Hotel. The transport continued to Prague.

The illegal passengers wanted to leave Poland the easy way by train instead of crossing the border illegally and going from D.P. camp to camp until they would reach France. Of course, all along the border, the Brichah members were helping thousands of Jews to cross the border illegally, some in the woods not far away from the train[5]. Once the stowaways were taken off the train, all was right with the tally. The Polish border guards gave the conductor permission for the train to continue across the border. Before the train started to roll, Captain Drucker, Rabbi Becker and the special Polish military guards left the train. One of the non–Jewish Polish soldiers who had been guarding the train told Drucker he was happy to have had the guarding detail. The soldier told Drucker he was really Jewish, not a Gentile, and that his wife and five children had all been killed by the Nazis. Drucker patted him on the shoulder and then stood near the tracks and watched as the train moved beneath the signs that separated Poland from Czech territory. He waved at the children he'd brought out of the farms and monasteries, and convents, hoping they'd find a better life where they were going than that they'd been handed so far.

The train crossed the Polish border and entered Czech soil. After a perfunctory check of papers, the train was permitted to continue the journey. It was already daylight and the distance to Prague was several hundred kilometers away. The train would never reach Prague before Sabbath. How could the Rabbi permit the train to travel on the Sabbath, something forbidden to religious Jews. While the Rabbi considered the options another objection reportedly arose. Mrs. Rachel Sternbach, the Va'ad Hazelah representative approached the rabbi and demanded that her group be permitted to leave the train in order not to violate the Sabbath. While the rabbi was pondering the question of Sabbath, the train finally arrived in Ostrava, Czechoslovakia, at nearly noon on Friday the 23rd of August 1946. According to the original schedule the train should already have been in Prague.

Rabbi Herzog went to the Polish authorities on the train and pleaded with them to sidetrack the transport until the Sabbath ended. His request was denied. The train was due in Paris. A contingent of wounded Polish soldiers was waiting in Paris, and the train was already behind schedule. If the Rabbi wanted to go to Prague, stay on the train, but if not, get off. The train was going to leave in minutes.

The Rabbi instructed all aboard to gather their belongings, and leave the train. He made certain the minders checked each compartment to make sure none of the children or supervisors was left behind. One imagines the Rabbi had serious concerns how food and lodging was going to be found for over six hundred Jews in a town like Ostrava when he stepped off the train.

Lucky for Rabbi Herzog and the passengers on his train, Ostrava had a small Jewish community of Shoah survivors. The Czech JDC helped the survivors to reestablish their community. The Czech Brichah used, on occasion, the city as a rest home for Polish Jewish refugees so the local Jewish community helped the refugees. Ostrava, about 290 kilometers from Prague, sits along the merger of the Ostravice, Oder, Lucina, and Opava rivers. A coal–mining and industrial town, Ostrava was off–limits to Jews under the Hapsburgs, until about 1792 when a Jewish distiller arrived and opened up a business. After the Hapsburgs granted Jews freedom of movement in 1848, more Jews arrived. The Rothschilds opened a steel mill there in the late 1800's. By 1900 there were about 3,200 Jews in Ostrava, the third largest Czech Jewish population after Prague and Brno. About 7,000 Jews lived in Ostrava before the outbreak of WWII. The Nazis deported about 4,000 to Terezin, the rest to other camps. The six synagogues were burned down. Because of the steel mills, the town was badly damaged by Allied bombs during the war. After the war about 250 Jews returned to the town.

Frantic telephone calls were made to the UNRRA office but the offices were closed. Mrs. Sternbuch called the Vaad Hatzala office, but that too was already closed. The children were milling around the railroad station, their minders trying to keep them out of trouble. The Prague JDC office received an urgent cable pleading for help. Someone contacted Gaynor Israel Jacobson, Joint director in Prague. Strange as it seems, up until then Jacobson, according to JDC cables, had not been informed about Rabbi Herzog's successful efforts to organize a train filled with Jewish orphans that was soon to arrive in Prague. In all probability, the chief of police of Ostrava notified headquarters in Prague that a transport of Polish Jewish children had just arrived in town and are hanging around the railway station. He asked for instructions. Thus, Toman assistant minister of the interior became aware of the children transport.

Although the scale of the refugees dwarfed anything the Ostrava community had ever faced, when Jacobson turned to his contacts there they responded immediately –– first, by clearing the Moravska hotel in the city, placing it at the disposal of the Herzog transport, then organizing whatever food they could for the fast–approaching Sabbath. Most of the passengers were lodged at the Moravska hotel. A few others were placed in different locations nearby. David Danieli recalls that in the morning, the Rabbi conducted Sabbath services[6]. The Rabbi used the Torah scroll carried by the Yeshiva students. The rabbi also organized an afternoon study session for the Yeshiva students. He was, after all, still the Chief Rabbi of Mandate Palestine.

David Danieli, one of the children of the transport, took the opportunity to explore the city with some friends, and then play in and around the hotel. According to Danieli, for most of the Jewish orphans, the hotel was a novelty. Most had never been in a hotel, nor been exposed to the telephones, elevators, carpeted staircases, and velvet draperies. The hotel was not left in the same pristine condition the children found it in. While the rabbi was praying and giving a lecture to the students, the office of the JDC was busy pressuring all their connections with Czech officialdom, namely Zdenek Toman, to provide transportation for the Herzog transport. Many phone calls had to be made to insure that the children would leave Ostrava. The efforts paid off, for a special train was assembled and sent to Ostrava. Only a powerful man in the government could accomplish in 24 hours such a deed in post war Czechoslovakia where everything was in short supply.

|

|

| The Herzog children's train reached the main Prague railway station where Rabbi Herzog, seen standing on a small platform, thanked the Czech government and Czech officials for their hospitality |

Early Sunday morning, the supervisors gathered up the children and shepherded them to the train station. The children did not question how a train had appeared to carry them to Prague. Rabbi Herzog himself was unaware of all the behind–the–scenes maneuverings. But he was happy, nonetheless, to board the train for the ride to Prague. The train proceeded directly to Prague where it arrived August 25, 1946. A huge crowd had assembled. The Rabbi had requested from the Vaad Hahatzelah that they organize a reception, and to bring out the press. He thought that by publicizing this rescue he would be able to raise more money for the rescue and support of even more children. Apparently no one informed the Rabbi that the entire issue of Jewish refugees crossing into Czechoslovakia was a hot topic not only in Prague, but also in Paris, London, Moscow and Washington. The JDC office in Prague was trying to keep the issue out of the press, if possible. Rabbi Herzog's arrival was anything but quiet. Even UNRRA and Czech officials turned out to greet him.

|

|

| Rabbi Herzog speaking in Prague Aug 25, 1946 |

Rabbi Herzog addressed the crowd, thanking the Czech government for the hospitality extended to the transport. A huge Vaad Hatzala banner was hoisted held up by dozens of children, with hundreds posing behind them. Some critics point out that no other sponsors of the mission were mentioned in any other banners, not UNRRA, and not the JDC. Some respond that this was because only the Vaad Hatzala made a banner. Following the reception, the children were taken to the Repatriacni Tabor Dablice camp on the outskirts of Prague. This camp, a former German military base, was established by the Czech government to handle the thousands of refugees who crossed Czechoslovakia on their way home.

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Children Train

Children Train

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 06 May 2018 by JH