|

|

|

[Page 248]

by M. Y. Feigenbaum

Translated by Ofra Anson

In many aspects, our town lagged behind other towns in Poland. Yet, religious life was more developed than in other places. I do not mean the way religious life was organized, nor how people practiced, these followed the pattern set in earlier times.

Biala was known as a Hassidic town and was even documented as such in world Jewish literature, for example by Y. L. Peretz in his story “Between two Mountains”. Biala was the home of Rabbi Berish Landoy and his son, Rabbi Aharon. Rabbi Berish had a reputation as a great scholar, and many Hassidim came to him from all over Poland. The last story published by Opatoshu, “The Silent man from Wurk”, was written about Rabbi Berish Landoy. The court of Rabbi Yitzhak Jacob Rabinowitz, well known around Poland, was in Biala, and his Hassidim were called “the Bialer Hassidim”. Several communities of Bialer Hassidim can be found today in Israel. Their Rabbi is the grandson of Rabbi Yitzhak Jacob. Naturally, the rabbinic courts were very influential in the community and in the religious life in town.

There were also Mithnagdim in Biala, but there was no hostility between the two groups.

By the turn of the 20th century, there were no more Hassidic courts in Biala and religious life was mainly influenced by the town's Rabbi, Shmuel Leib Zak. Although most of the time he sat in his room with his books, and hardly mingled with the members of the community, his word was a command for the religiously observant.

Generation after generation, people were trained to adopt a strictly religious way of life. Men knew that their spare time should be devoted to prayers and learning. Praying and studying lasted from the cradle to the grave. Lullabies included messages of the importance of Torah studies. When a boy was a little older, he went to the Heder, where he learnt the whole day and in winter even in the evenings. When he graduated from the Heder, he continued studying either in a Hassidic learning institution or in a Yeshiva. Only those who could not learn went to work. Parents would do everything they could to motivate their sons to study. The parents' dream was that their son would grow up to be a scholar. At the same time, those who started working were not cut off from religious life. They kept praying three times a day, and on Saturday they learnt Chumash (Pentateuch) and read psalms like everybody else. I do not mean to say that there were no ignorant men in Biala, but everyone knew how to use the prayer book. Even those who could not read Hebrew were no strangers to it.

When the young men who were studying got married, they were often supported by their parents-in-law and continued their studies. The young men who started a business often let their wives run the store while they themselves went to study. Those who had to make a living themselves went to study a page of Talmud in the evenings. Indeed, Biala was known to be a town where many people studied.

Jewish women also were educated to keep to the tradition of strictly religious way of life. The Rebetzin [Rabbi's wife, O.A.] taught the girls to pray, and the mothers did the rest of the training.

[Page 249]

|

|

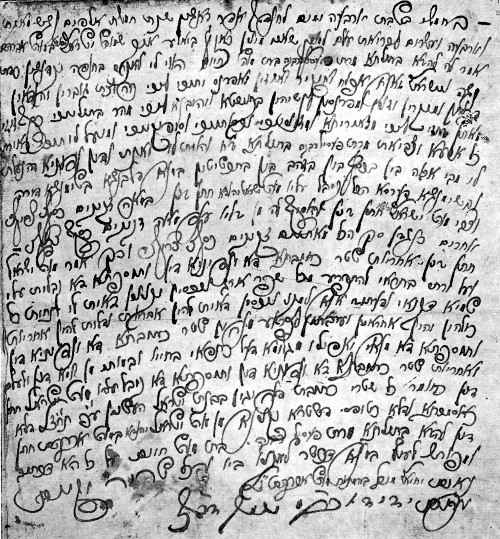

| Marriage contract (Ketuba) written in Biala in 1864 |

Among the women, the proportion illiterate and who could not pray was higher than among the men, particularly among the poor. The morning after the wedding, the bride's head was shaved and she wore a coif, and later – a wig.

At the turn of the century, and particularly during WWI, radical changes took place and religious life became looser.

Before Saturday or a holiday, one could see and feel which tradition was the dominant one. The local governors could have their way during the week, but Saturdays and holidays belonged to the Jews.

On Saturdays and holidays the Jews were not in exile in a Christian society, but the other way around. All the shops and workshops were closed, and a sacred atmosphere rested upon the town. Even in the remote villages, the Christians knew not to enter them on a Jewish holiday.

Until WWII, Jews determined the town's life on Saturdays and Holidays, despite the changes in religious life. Time, of course, brought about change, and some of the restrictions were somewhat released. The spirit of revolution in the Czar's regime affected life in town. WWI brought its own changes and the aspiration for freedom and equality also affected religious life. The streets on Saturday did not look like Shabbat at the turn of the century anymore. Shops were closed, except for two pharmacies, a colonial shop, and two other businesses (the pharmacies and the colonial shop had been open since before WWI).

[Page 250]

|

|

| Orthodox teacher Feiga Shnur and her girl students |

Still, on Saturday one would not see a Jewish person with a cigarette on the street. Behind closed doors, there were people who broke the rules. The only visible change on Saturdays was that young men and women walked on the streets together.

Yet, when the High Holidays approached, the fear of doomsday brought back the old religious life. For the whole month before the New Year, early each morning, men went to the synagogue to hear the Shofar and read psalms. Traditional tunes and prayers could be heard from workshops, people went to visit their ancestor's graves.

When WWII broke out, the yard of the synagogue included the synagogue and two places of learning, a learning place in Vollia, about 10 Hassidic prayer houses, and another few Minyans of Hassidim and Mithnagdim. The Talmud Torah on Proster Street was also active until the war.

There was a Yeshiva, established after WWI, which stayed until the last days of WWII. Mordechai Shimonowitz was the first headmaster, Rabbi Israel and the manager David replaced him. It was founded by Jews from East Poland and most of the students came to Biala from other parts of Poland.

Dr. Dov Yarden, a former student in this Yeshiva wrote:

“I was about 11 years old when an emissary from Novardok Yeshiva, located in Biala Podlaska, came to our town Motal (near Pinsk, birth place of Haim Weizmann). He gave a speech in the synagogue, encouraging the audience to send their children to the Yeshiva in Biala. My parents and the Kolodney family accepted the offer.

My father came with me [to Biala, O.A.]. He presented me to the head of the Yeshiva, Rabbi Mordechai, a pleasant, handsome, man. My father praised me, and mentioned I knew the sacred language . Rabbi Mordechai said that it is not the language that should be sacred, it is the heart. The main difference between Novardok and other Yeshivas was the moral teaching. Most of the day was devoted to studying the Talmud, like in other places. Rabbi Mordechai and his assistants taught us, and we memorized the lesson either by ourselves or with a friend. Yet, some hours a day were assigned to moral studies. We used different books, such as “Chovot HaLevavot” [“Duties of the Hearts”, O.A.], written by Bahya Ben Yosef Ibn Pakuda (skipping the first, “philosophical”, “gate” [section, “sha'ar” in Hebrew. O.A.] because of unexplained fear); “Sha'arei Teshuva” by Yonah Gerondi; “The Prince and the Monk” by Ibn Chesdaii; “Mesillat Yesharim” (“Path of the Upright”, O.A.) by Rabbi Moshe Haim Luzzatto, and others. We dwelled particularly on the essays of Rabbi Yosef Yoizel Hurwitz, the founder of the Yeshiva “Madregath HaAdam” [“Stature of Man”, O.A.], based on conversations he held over the years. We used to read the books for about half an hour, and then went out to discuss what we had read. Each older student took one or two young student with him and, with one on his left and one on his right, walked up and down the study house and discussed a moral idea. We used to call these conversations “Burse”. On the origin of this name there was a story that Rabbi Yoizel (or “the elder”, as we used to call him out of respect), while visiting the study house and seeing the enthusiastic moral discussions between the students, said amazingly: “This is like in a real burse!”

Apart from studying in the educational institutions, men went into the Hassidim prayer houses to study Torah. The teacher, Benjamin Hersh Eidelman, used to study in Beith Hamidrash, each evening and Saturdays, with those who were interested.

There was a Tehilim Group in town, who regularly came to the praying house to read psalms. There was a group of Shabbat keepers, who went around the town Fridays before candle lighting to remind the traders to close their shops. On Saturdays, they used to patrol the streets to check if smoke came out of any chimney, and if they detected some, they entered the house and asked them to turn the fire off.

[Page 251]

Occasionally they went to the train station to make sure that Jews did not ride the train on Saturdays.

The Mikve [ritual bath, O.A.] was in a sealed building on Bud Alley. The building was renovated during WWI. The wooden walls were replaced by metal ones, and showers were installed. After the war, it was used mainly by the orthodox.

The following persons were active in the religious life of Biala:

Rabbis:

Rabbi Nahum Wolf Bornstein (the father of the well-known Rabbi Avreimale from Sochachow). He lived in the market, in the house of Israel Wichnem (later rented by Motl, the leather trader). The Rabbi had a Yeshiva in his home.Rabbi Shmuel Leib Zak became the town's rabbi after him. He came from Szczebrzeszyn. He lived on Brisker Street, in the house of Motye Shuster. He died in Otwock, in the winter of 1932, and was buried in Biala.

The last Rabbi was Zvi Hirshorn. His previous position was in Yavoshna. He lived in the Market, in the house of Motl the leather trader.

Rabbinical Judges:

Before WWI: Rabbi Leib Zak (he specialized in writing contracts according to Jewish law. People invited him for their more important contracts, personal matters or property selling. His contracts were accepted by the official notary); Rabbi Yakir, Rabbi Yitzhak Kalman; Rabbi Menke (the son of the Rabbi from Tykocyin, he had the reputation of a great scholar). After the war, Rabbi Moshe Otchen (the son in law of Rabbi S. L. Zak).The Rabbis and the judges were paid from the earnings of the slaughterhouse and by the community. Later, after the Polish independence, they were paid by the community (which now had responsibility for the slaughterhouse).

Slaughterers:

Gershon Mendel, Shimon, Haim (all before WWI); Salman's Mendele (he was a great scholar and published a book by the name of “Memories of Menahem”); Meir Yod; Shmuel Rubinstein; Jacob PolonJetzky and Keibele Winetraub (from Markuszow, the son in law of Mendele the slaughterer).Cows were slaughtered in the slaughterhouse; fowls were slaughtered at the slaughterer's home and later in the prayer house yard.

Supervisors:

Gitl Bashe's Baruch; Moshe Hofer; Zelig Hersh (before WWI) and Meir Aranowitz (nick named Pishke [box, O.A.]).

Purgers:

Elijahu Mordechai and Gdljahu Leib (both before WWI); Davidche Grinstein (from the Kitties); and Shlomo Eliezer Frankreich (Shlomo Lazar).

Let us list as many scholars and teachers as possible that worked in Biala during the last 70-80 years of Jewish life. The great scholars were, among others: Berish Landoy, Rabbi Nahum Wolf Bornstein, Noah Shahor, Itche Moses, Moshe Latzes (called “Big Moshe”), Leibish, Siskind, Haim Asher, Aharon Lipke, Menke, Itchke's Heinch (a young man, son of the teahcer Itchke Patel), Aharale Judah Jacobs, Moshe Yaffe, Wevel Goldfarb, Meirl Kalishiner, Gavriel Sofer, the brother in law of Shalom Vinograd (his name was forgotten, he later became an atheist and died young), Komlet (the husband of Ita Gampl), Baruch Eisenberg, Small Moshe, Rabbi Shmuel Leib Zak, Yehezkel Erlich, Shimon Kreidstein, Joel Meir Hilbloom, Benjamin Hersh Eidelman, Benjamin Gewirzman (Sotche's), Mendele Shohat, Baruch Shalom Kreidstein, the son of Mendel Rososher (a youngster), the brother of Moshe Kaveh, Israel (son of Hershel Yanover, died young).

Teachers:

Moshe Kalman

Avreimale Kodiner

Eizeek

Feivale Lubliner

Jacob Nathan

Israel Yitzhak Heigenbaum

Shmuel Hersh Appleboim (father of Nera the teacher)

Mendel Appleboim

Leibish Katz (a nickname)

Leibele Rososher

Arieh's Leibish Jacob

Tzalke

Welel Lutwak

Moshe David (son of the teacher Tzalke)

Welvel Idl the laundryman

Shia's (Yeshajahu) Sender

Aharon Lipe

Kive (Akivah)

Tuviah

Yehuda Leib Ashberg

Elijahu David

Shepsel's Elijahu

Wowele's Elijahu

Eliezer Leib

Shmuel Yankl Rubinstein (father of the teacher Menahem Rubinstein, and grandfather of Rabbi Shmuel Rubinstein, Paris)

Itzl (Yitzhak) Nahum

David Walf

Peie's Hersh Haim Moshe

Artchele's Hershl

Shlomo Kreidstien

Nahum Petke (teacher of very young children)

Tuvia Glikeles

Motl Domatchewer

Avraham Avele

Avreimale Janover (teacher of very young children)

Jonah Krokewer

Nuske (the son in law of Welwel Lutwak)

The teacher from Badker

Pesah Rishon [Pesah the first, O.A.] (teacher of very young children)

Pesah Sheni [Pesah the second, O.A.] (teacher of young small children)

The teacher from Radzyn

Hershl Shtrikenmacher (teacher of very young children)

Tuviah the Ginger

Moshe Haim Kligsberg

Binem (Bunim) Rososher (also produced wine for Kiddush)

David Leibele (son in law of Shalom the butcher)

Yizthak Moshe Bobkes [a type of cake, O.A.] (nickname, his wife made the cakes)

Leibele Ketche (nickname)

Avraham Yitzhak (son of Hain Hushler)

Moshe Itzikl (his mother was the sister of Shmuel Moshe the butcher)

Avraham Simha

Mendele

Itchke Potls (nickname)

Moshe Srul (Israel) Potls (nickname)

Haim Asher

Shakele Feigenboim (teachers for girls)

Hersh Ham' Sender Matias

Baruch Shalom Kreidstein

Yankl (Jacob) Brahie (Brahyahu – a Talmud Torah teacher)

Haim David Appleboim (a Talmud Torah teacher)

Nahum Eidelman (a Talmud Torah teacher)

Neta Appleboim (nicknamed Shteker)

Berele Appleboim (Neta's brother – teacher of very young children)

Joel Meir Heicloom

Feivele (teacher of very young children)

Menahem Rubinstein (the father of Kihele's husband)

Benjamin Hersh Eidelman (the son in law of Welvele the butcher)

Moshe (Israel Yitzhak's) Feigenbaum

Yitzhak Orkelesh (a Talmud Torah teacher)

Haim Gitl Milboim

Hershele Bankhalter (son in law of Simhale Sofer)

Hershele (teacher of very young children)

Elijahu Davidl Gutman (teacher of very young children)

Fleck (nickname – a teacher of very young children)

Shmuel Gliksberg

Haim Israel Finklstein

Moshe Michl (teacher of very young children in Talmud Torah)

Mendl Rososher

Aharon Hil (Yehiel) Weinberg

Welvel Yustman (Rososher)

Shlomo Haim Shwartzbard (a Talmud Torah teacher)

Ben-Zion.

[Page 253]

Until the First World War, the so-called “Kazyonne” Rabbis were also active in Biale. The classification “Kazyonne Rabbi” speaks for itself; these were Rabbis for the authorities, and not for the Jewish population. These Rabbis received their salaries from the community and an additional income for keeping the registry of Jewish births.

Of these Kazyonne Rabbis, the people of the town would remember one called Yosef Dryzin.[1] In approximately 1889, he came from Russia, having been appointed by the Governor. He was a liberal person and was driven out of the town by the community.

A Biale resident, Shlaymele Goldberg, became the Kazyonne Rabbi after him. He had once worked for the public registrar and later passed examinations to become a Kazyonne Rabbi. Shlaymele died even before the First World War and there were no Kazyonne Rabbis in the town after him. Under Polish rule, the Rabbi Moshe Utshtein, a judge of rabbinic law, would receive the oath of the Jewish soldiers in the town's regiments and was the guardian of the Jewish soldiers in the town.

This is how religious life continued in the town, almost without disruption under all the political regimes. With the occupation of Biale by the Germans in 1939, this life ceased to pulsate. Pious Jews were forced to shave their beards, wear peak caps, and because of forced labour, even had to desecrate the Sabbath. The prayer houses were filled with newly arrived refugees and people no longer prayed there.

Footnote

Translated by Phillip A. Applebaum

Before a Talmud Torah was built in the city, poor Jewish children whose parents could not afford Jewish education did not remain without Torah learning. There were the so-called Talmud Torah teachers who, in their own houses, taught the poor children without a fee and the community rewarded them for it.

Around 1894, the community purchased the house near the prison on Prosta Street and there organized the Talmud Torah. The Jewish poorhouse was also there.

Around the First World War, the officers of the Talmud Torah instituted wide-ranging reforms. This probably was done under the influence of the Yavne School.

The poorhouse was removed and a major renovation was undertaken. Modern school benches were installed in some of the rooms, and also a detention room was set up ... A school office functioned under the management of Moshe Braverman and for the first time in the history of the Talmud Torah, there was registry of students. The most important of all the reforms was the instituting of secular studies several times a week for several hours. The teachers were Volf Nuchowicz, Michael Fejerman, Gedalia Krawiec and Moshe Kramarz.

During the period of Polish sovereignty the condition of the Talmud Torah worsened in all respects and again, neglect was the order of the day. The Jewish ritual slaughter of chickens took place in the school yard in full view of the children.

The Talmud Torah's budget was mostly covered by a subsidy from the Jewish community and the remainder from a minimal tuition.

The Talmud Torah Committee, in various times, consisted of Moshe Laces (“Big Moshe”), Leibish Sourimfer, Moshe Uczen, Binyamin Cohen, Meir Jud, Yisrael Eliyahu Szapiro, Moshe Melech Silberberg, Yerachmiel Lichtenbojm. Some of the committee members came on Shabbat in the summer to hear the students recite their lessons.

Administrators of the Talmud Torah in the decades before the Holocaust were Selig Frajnd, Moshe Melech Silberberg and David Silberberg. The administrators also sold shechita coupons.

The teachers were Chayim David Epelbaum, Yankel Brachja, Yitzhak Urtszeles, Menachem Rubinsztejn, Velvil Rososzer, Shmuel Kligsberg, Binyamin Hersh Edelman, Nachum Edelman, Moshe Michl, Chayim Yisrael Finskesztejn and others.

Information received from Moshe Braverman, Asher Hoffer and Alter Weinberg.

Additional Details

232 students study in the Talmud Torah. The Christian teacher, Zelichowski, instructs the students the Polish language. A Talmud-Torah teacher earns 30 zlotys a month in salary (Podlashier Leybn, number 4 of 28 January 1927).

Administrator of the Talmud Torah was Moshe Melech Zilberberg. And the teachers that worked there: Chayim Szwarcbord, Chayim Yisrael Finkelsztajn, Chayim David Epelbaum, Binyamin Ze'ev Ajdelman (Podlashier Laybn, number 18 of 12 August 1927).

Despite the fact that most recently the Talmud Torah teachers are paid 10-15 zlotys a week, they declared a strike on 15 January 1933 (Podlashier Laybn, number 3/68 of 20 January 1933).

The preliminary community budget provided a subsidy for the Talmud Torah at the level of 5,500 zlotys (Podlashier Laybn, number 5/70, of 3 February 1933).

[Page 254]

by M. Y. Feignbaum

Translated by Ofra Anson

The Synagogue

Even the oldest people in Biala did not know in detail how the synagogue came to be built. According to the accepted story, prince Radziwill built it. It seems plausible that he helped with building materials, or even with money. The older people only remembered that, before their time, it was painted by the Christian artist–painter Tzishewski. Why was the work, in a holy Jewish place, entrusted to the hands of a Christian, when Jewish builders were available? Is it possible that the Jewish builders were not qualified enough?

At the end of the 19th century, the synagogue underwent a major renovation, which cost few hundred rubles. During the renovation, the plaster was repaired, and a new coat of paint applied.

The entrance was to a corridor that was a little lower than the street. Steps led from the corridor to the synagogue, which was about a meter and a half lower. The corridor included a Holy Ark, Elijah's chair and a bowl of water to wash the hands.

|

|

| The Synagogue and the Beit Hamidrash |

A closed cellar with names was on the left side of the synagogue. The Permanent Candle was on the west wall of the synagogue, next to the entrance. The Holy Ark stood next to the eastern wall, which was quite simple, with no special decorations. A few steps led to the Holy Ark, and the lectern stood right next to it. The stage was in the middle, surrounded by metal bars and wood. The access to the stage was from the south to the north. High windows were located on the walls, except for the western one. Looking at the windows, one could see how thick the walls were, more than half a meter. The walls were covered with wood up to the height of two meters. Around the walls were benches and stand and next to these stood benches and tables.

The women's section was on three sides of the synagogue: south, north, and west. On the southern and the northern sides there were two attached wings on the ground floor.

The entrance for men and women was from the front, on the west side. Women could watch the service through a thick window with bars.

Over the synagogue, there was an attic, with a round opening on the western side. A stone–paved pavement led to the building, with two large stones on its side, where brides and grooms used to stand during the marriage ceremony (Huppa).

Until the end of WWI, oil lamps and candles in a big copper chandelier hung from the ceiling and smaller candleholders on the walls behind the benches lit the synagogue. After the war, electricity was introduced.

The synagogue had a hand–written book of prayers (Siddur) made of parchment, size A4, which had been mended in a few places. It had several beautiful Parochet, artistically made. The most beautiful one, artistically sewed and carefully finished, was saved for the high holidays. It was decorated with two verses, embroidered with silver yarn: “Tikuu Behodesh Shofar” (blow the Shofar, O.A.) and “Ki Bayom Haze” (on this day, O.A.). During the Ten Days of Penitence, the Parochet with “Remember us for Life” was used, and on regular Saturdays the one with “And Israel will keep the Shabbat” embroidered on it was hung.

During the thirties, an old book was discovered, with a note–book of the “Eternal Candle” society, which operated in Biala in the past.

[Page 255]

A few years before WWII, the synagogue was renovated again. This time the builder was an acquaintance from Miedzyrec, the synagogue builder Hersh Liber Podolak.

There were three Minians in the synagogue: the early Minian, the cantor's Minian, and Moshe Kaveh's Minian.

|

|

| Contract of purchase of a place in the synagogue, written by Rabbi S. L. Zack |

The janitors (Gabaim) of the Synagogue were: Moshe Feikes, Godel Binik (Milboim), and Yosel Wetchik.

The cantors were: Mechl from Russia, Joshua'le, and Moshe Yehuda Hacohen from Lithuania, who served for about 15 years, until WWII. He was known to be extremely orthodox, and devotedly supported the Novgorod Yeshiva in Biala.

Among the others who conducted the prayers were: Shimale Kreidstein and Benyamin Kliger.

The Germans destroyed the synagogue.

Further Details

It would appear that this was not the first synagogue in Biala. People used to call another place “the old synagogue yard”. It was the place where the houses of Moshe Haim and Treinele and Godel Binik the carpenter on Proster Street, and up to the houses of Hiench and Alther Kawal (Jarnitzki), with an entrance on Grabnover Street.

The first Minian was called “the waking up Minian”. It was the Minian of porters and wagons owners, who used to get up very early for work, and got up early, even on Saturdays. Sholkele Feingenboim, the lame girls' teacher, led the prayer for this Minian. The Gabai was Avigdor Reicher (nick–named Tato).

The second Minian was the cantor's Minian. The important people prayed in this Minian, for example: the lawyer Heartglass, Idl Schwartz, Israel Cohen, etc.

[Page 256]

Moshe Kaveh's Minian was the third. The people who prayed in this Minian were mainly artisans, some Hasidim who used to pray in the Sephardic style. The prayer leaders were, until WWI, Mendele Melamed, later the writer Yeshayahu Eliezer (Shaii Laizer).

Before the Shtibels [literally, a small home; it means a small praying place, O.A.] for the Gere and the Radzyn Hasidim were built, they prayed in the women's section on the left hand side of the synagogue. When the Hasidim left, the Minian named the “Tailors' Minian” came onto the first floor. The shingle makers also prayed with them. The outstanding members of this Minian were Rabi Yosl Koliatsh (second name), and Rabi David Baruch the requests writer. The reader was Rabbi Gabriel Rosenstein.

In the women's section, on the second floor, prayed the “shoemakers' Minian”. This Minian was respected because they had a good pray leader, Yoel Kigl (Shtromvaser), on one hand, and a good choir on the other. Their reader was Ben–Zion the teacher.

The Beith Hamidrash was built in 1892/3 in the same place where the old, small, Beith Hamidrash, had been. This was about to collapse and had to be demolished. The initiators of the building were Motl Shenker and Izik Shahor (the father of Tile Berlin). The money was collected from donations by the residents.

The builder was Israel Weinberg, and the furniture made by Shmuel Shmai Simels (Friedman).

The building was made of bricks, and the roof made of tin.

The women's section was on the western side, and it had two enterences on the side. The window from the women's section into the Beith Hamidrash had thick bars.

Two large doors, on the southern and the northern sides, lead to halls, and from there, a few steps lead to the Beith Hamidrash itself. The bowl for hand washing was located by the southern entrance, on a high brick stove. By the entrance from the southern side stood a bookcase. The Ark stood in the middle of the inner eastern wall, a few steps higher than floor level. The lectern was on its right side. Left to the ark was the Rabbi's place. The stage was in the middle, and it could be reached from both north and south. Four wooden poles were located next to the stage, up to the ceiling. There were three big windows that let a lot of light come in.

The Beith Hamidrash was full of tables and benches. On one table by the western wall book–sellers, not necessarily from Biala, used to sell books and other items for religious purposes. Beith Hamidrash could hold some 500 people. Electricity was installed in 1918. Oil lamps were in use before that.

Major renovations took place a few years before WWII. The tin stoves were replaced by white stoves. A fresh coat of paint put on the ceiling and the walls by local experts: Abraham Lemberger, Haiim Yosef Knuzcnik, and the Rosenker brothers.

Many minyanim prayed in Beith Hamidrash fron early in the morning. All day long one could see people studying the Gemara. In the evening there were more people studying, among them: Goldfarb (Velvele?) and the teacher Benyamin Hersh Eidlman.

Friday night Psalms were read in public. During the last period, the tailors Pesach Saks (nick–name) and Sheime Bekerman (from Sanies) were the readers.

Among the leaders of the prayers were: Rabi Manes, Eizshe Libman, Soshe Rosen, Joel Greendlass, and Haiim Shye (Yeshaayhu).

The minyan the rabbi prayed with, The Gere Hassid Zalmn Zak lead the prayer.

The Gabayim of Beith Hamidrash were Moshe Tuvya Stolier, Itzke Koval, Yosef Nathanson, Michael Eizenstat, Zile (Uziel) Stolier (Feigenboim).

Janitors: Shalom, Yankel, Avraham Thevel, Avreimale, Noah, Joel Greendlass, and Haiim Shye (Yeshaayhu).

After WWI, the yeshiva operated in the women's section.

[Page 257]

During the Nazi occupation, Beith Hamidrash was converted to host refugees. They burned every item made of wood during the freezing weather. Even the wooden floor was used. Like the synagogue, Beith Hamidrash was taken over by the Germans during the war.

Further Details

The first minyan was the Mitnagdim [the Orthodox Jews that opposed the Hassidic movement, O.A.]. These were mainly artisans, who also did odd building jobs for Beith Hamidrash.

On the Eastern side sat: Velvele Waserman, the architect and the chief planner of Beith Hamidrash; Shlomele Stolier and his son, Menachem Leibele, sat next to him; the brothers Shaulke and Itschke Eidelman (Kavales); and Moshe Toker. The Gampel family also sat at the eastern wall, because Leibish Gamplel was Gabai and administrator of Beith Hamidrash when it was built, and worked for Moshe Batchke, who donated handsomely to the building.

The second Minian was the Hassidic one. The best known of them was Rabbi Zalman, the son of the former Rabbi, a brother of Avreimale Sochatzover, and Rabbi Heikel Lichtzier. The Hassidim named the Toiter [the dead, O.A.], from Broslov.

The Additional Beith Hamidrash

At the northern side of the Synagogue's courtyard stood the “Additional” Beith Hamidrash. It was built by a few Jews from the Russian army to commemorate their survival in the Russian–Japanese war.

It was built after the Russian–Japanese war. The initiators were Shmerl Pep (nickname) and Heinch Koval (Yarnitzki). The money was raised from the reserved Russian army stationed in Biala. The workers came from the reserved army, and Alther Weinberg supervised the work.

Human skulls were discovered while digging the foundations for the Beith Hamidrash.

The entrance was on the southern side, and lead straight to the Beith Hamidrash. The floor was a bit lower that the door step. Indoors, on the western side, was another door, which led to a small room.

By the eastern wall stood a wooden Holy Ark and a lectern. In the middle of the large room stood a table to read the Tora. Tables and benches stood around the walls.

Over the Holy Ark was the permanent light with the inscription: “Donated by Meir, son of Rabi Yehuda Leib Goldhamer” (the eldest son of Leibele Shemes, on behalf of Feivel Gold, North America).

The women's section was built over the Beith Hamidrash. It looked like “r”, and was closed, with wooden bars of 1.5 meters high. The steps to the women's section were on the western side of Beith Hamidrash. Next to the entrance of the women's section was a little apartment.

Most of the years, the Gabai was Jacob Velvel Hershberg, the blacksmith.

A Heder operated there during the last years before WWII.

This Beith Hamidrash also hosted refugees during the war, and here too all the wooden pieces were burnt.

The Germans destroyed the Additional Beith Hamidrash too, and thus no sign of Jewish life remained in the synagogue's courtyard.

The Beith Hamidrash of Volia

Some say that Jews settled in Volia before they settled in the town. To find its Beith Hamidrash one had to walk out of the town, cross the river to its left bank, away from the path, almost out at the green. It was built like a Hasidic Shtible: without a stage in the middle and without a built Holy Ark. Four wooden stands were in the middle, and it had a women's section.

It was a low building. It stood on wet ground, and its foundations had to be changed from time to time.

Two minyanim prayed there. In the first prayed the Motnagdim, and then the Hasidim (Alerlii Hadasim)

[Page 258]

by Fyvl Gold, New York

Translated by Libby Raichman

The Kotzk Prayer House

The Kotzk Chassidim were the first Chassidim in Biale, so their prayer house in the street of the bathhouse, was the oldest. It is my opinion, that it had already existed in the first half of the previous century.

The Kotzk Chassidic Rabbinic court was the closest to Biale. The most important and first travellers of Biale were: Reb Herzl Cohen (Reb Shualke's and Reb Yisroel Meir's father), Reb Izik Shocher-Tsharny, as well as my great-grandfather Reb Yakov Eliezer Pishtshatzer.

The Chassidic prayer house was a traditional large synagogue, with four pillars in the centre, the holy ark in the east, and the lectern for reading from the Torah, in the middle. There was a room on the right that was filled with religious books.

The Kotzk Chassidim had split a few times. The last split occurred between the Sokolov and Pillev Chassidim and the prayer house remained in the hands of the Sokolov Chassidim.

The most eminent Chassidim there, were: Reb Boruch Sender and his son Reb Dovid (Kligberg), Reb Shmuelke Pizshitz, the tar makers, the scholars: Hersh Chaim Melamed (of the Pyes, great-grandfather of Elye (short for Eliyahu) Marks, (New York), the teacher Binyomin Hersh, Reb Yakov Goldhammer (my father's brother, who was called Yankel of the bubkelach, Shayne Chaye's; the teacher Reb Dovid Leibele (son-in-law of Sholem Katzeff).

The Ger House of Prayer

This prayer house situated in Potshtovve Street, was enclosed by a high fence. It had a large courtyard with tall trees. One would walk up a few steps and enter the foyer. On the right side of the foyer was the entrance to the prayer house, and on the left side - the residence of the beadle. The prayer house was large and bright. At the eastern wall was an entrance to a smaller room, where shelves of religious books were housed.

At the eastern wall, on the left of the holy ark, sat those of very distinguished descent: Reb Yisroel Meir (a younger brother of Reb Shualke, and son-in-law of the first Rabbi of Gur, Reb Itshe Meir, the exalted Torah reader in the prayer house; Reb Yossl Yunever (the father of Dina Yunever), who in his later years, left for the Land of Israel; Reb Leibl Dine (of holy memory). Reb Leizer (Eliezer) Mintz (of the “Varshavsky Magazine”), and Leibele Dovid, son of Reb Isaac.

Besides those mentioned above, there were other members of distinguished families who prayed there: Reb Eliyahu Mintz, Reb Bunim Leibele, the sons of Reb Shmelke (Shmelke and Yakov Kahan's grandfather, a son-in-law of Reb Isaac Shocher. In Biale, if one wanted to reprimand someoneone, they would ask: “what are you, a Reb Shmelke?”), Reb Dovid Tzvi (the grandfather of the Orlanskes) etc.

At the table between the southern and western side, stood Reb Shualke (Reb Hertzl's oldest son, regarded as the wealthiest Jew in Biale), who conducted himself in an unassuming way and

|

|

| The Prayer House of the Gur Chassidim (winter 1944/5) |

[Page 259]

sat together with the common people. Yirmiyahu Bedner (also Bedder) and his family, also sat at this table.

On the Sabbath, prayer services were held three times. The first was called “Reb Yossele's prayers”. Reb Yossele was the brother of “words of truth”, and brother-in-law of Reb Noach Shocher. He stood in a place of honour, at the large printed prayer “Hodo”. Next to him: Reb Mendl Buchner (Reb Chaim's youngest son-in-law), the family of Reb Moshe and Zishe Cohen, Reb Yechiel Hersh and other “P'nay” [leading citizens]. Reb Yossele, who wore a tallit with the largest display of silver embroidery at the collar, was a quiet and unassuming man. His strength was manifest on Simchat Torah, when he was given the honour of reciting the “Atah Har'aytah”, and an additional soul entered into this quiet Yossele as he delivered the prayer with confidence, pride and contentment. The last two verses poured out with immense rapture (his wife Chanele, would gather round, flat stones the whole year, to make her utensils kosher on the eve of Passover. She would ask my mother that when she baked matzah at our place, she should ask those who rolled out the dough, to have pity on her and say, “for the sake of good matzot”).

The second service was called, Moshe Latze's, or Moshe the big one. Reb Moshe the big one, was Reb Noach Shocher's oldest son-in-law, and was regarded as one of the great scholars in the town. He was the main ambassador of the Rabbi of Gur in their rabbinical court in Biale.

The leaders of these prayers were: Reb Yosef Lubliener (the only one who studied the Jerusalem Talmud) and Reb Leibele Shocher. The Torah reader was – Reb Zalman, of holy memory.

The third prayer service was called, Reb Meirl Kalushiener's. This prayer service was conducted from 2pm to 3pm. The main objective for these worshippers, was study.

Reb Meirl Kalushinner was regarded as a great and astute scholar (his first wife was the daughter of Reb Yisroel Meir).

The leaders of these prayers were: Reb Hershl Urtsheles and Reb Motl Mintz, and the Torah reader – Reb Meir Korman.

Aliyot to the reading of the Torah were sold, with exception for a few congregants of distinguished descent, as well as for a bridegroom, for the father of the bridegroom or for a Barmitzvah. The prices of these call-ups would rise on the Sabbath, before the new moon, at the beginning of a new month, even more on the festivals, and mainly on the High Holy Days. The person who paid the highest price (minimum 25 Rubel) would bring in the prayer “Atah Har'aytah” (Motl Mintz), and Yisroel Cohen bought “Chatan Brayshit” . There was also an annual fee, the highest being -- 12 Rubel and the minimum - one Rubel. The fee was collected by snatching the worshippers' tallitim on the Sabbath and then requiring the person to pay their fee, for the return of their tallit.

The youth sat and studied in the Ger house of prayer, as well as in all the other Chassidic houses of prayer. The two eminent Talmudic Chassidim were: Reb Yosef Refael (Reb Yisroel Meir's oldest son-in-law – the first trustee of the synagogue, from the earliest times, that I can remember; three of his four sons, were Rabbis in the small towns), and Reb Shimon Ahreles (a brother-in-law of Reb Leibl Dine, the father of Aharon and Yakov Gelblum) would often walk over to the young students and help them.

The Radzin Prayer house

As is known, the Radzin Chassidim wore a blue thread in the tassels of their prayer shawl and undergarment; due to this, there was a major dispute between them and other Chassidim and they were severely harassed; they were not allowed to approach the synagogue lectern, and not allowed to be called up to the Torah. They were, therefore, very stubborn. (In Biale, a stubborn person would be asked: - who are you? A grandchild of Reb Shabtai? – meaning Reb Shabtai Finkelshtein).

Reb Shabtai Finkelshtein was a son-in-law of the famous Shocher family who initiated the construction of the Radzin prayer house in Biale, a sufficiently large prayer house in Vansk Street, that was built of brick.

Those who assisted him, both with money and with professional knowledge were: the Goldreich family, Reb Chaim Pesach of the wine store, and Reb Tzemach Shenker (Tuchmintz). These were Chassidim truly, to the core.

In later years, the main person of distinguished descent, was Reb Yechezkel Erlich, one of the scholars in the town. The following were also regarded as distinguished: Reb Kalman Sheinberg (of Reb Shabtai's and Reb Urele's family) and Reb Zishe Goldreich.

Eminent worshippers were, among others: Reb Arye Tabatshnik, a handsome Jew and a passionate leader in prayer, Reb Yehuda Yakov and the “targovnik” (a nickname – father of Yoel Itzl Schneider, New York).

The Partzev Prayer House

After much wandering, over various premises, the Partzev Chassidim chose a place for prayer, in a unit, in the house of the brothers Itshke and Shualke Eidelshtein (Kovalle's), that was located close to the Rodzin prayer house, and the prayer house of the opponents of Chassidism.

The eminent Chassidim who belonged there were, Reb Leibe Bornshtein and his son-in-law Reb Chaim Rammes. Their prayer leaders were: Reb Natan Rammes (son of Reb Chaim), and the teacher Reb Aharon Yechiel Vineberg.

The Lomaz Prayer House

The Lomaz Chassidim did not have their own house of prayer. Before the Viness fire, their prayer house

[Page 250]

was situated on Proste Street, at the corner of Kshivve Street, opposite Reb Aharon Landau's courtyard. After the fire they were at first, in the premises of Berel Kozzes, (a Lomaz Chassid) later – in occasional premises only for the Sabbath and the festivals. Their last place of prayer was in the premises of the well-known honey-cake baker, Alte Treinele, in Proste Street.

Of the older eminent Lomaz Chassidim there were: Reb Velvl Lutvak (husband of Treinele, well-known for her hospitality and father of the sisters: Shifrah and Alte), the scholars Reb Paltiel Oppenheim (son of Yeshayahu of Zeif – who had a wholesale food store) and the teacher Reb Menachem Rubinshtein (the husband of Alte Treinele and father of Rabbi Shmuel Yakov Rubinshtein in Paris, the author of the book “Sh'ayrit Menachem”” that was published in three volumes, in Paris in 5714 [corresponding to 1953].

The Lomaz prayer house produced three distinctive characters: Reb Boruch Yakov Brodatsh (Gershon Chaim Kubeles son, brother of Chaim Brodatsh – New York, a local quick Torah reader, who managed, on a Shabbat, to read the weekly Torah portion at a few different prayer houses in the town; Yosef Marchbein (of the Patotz's – nickname), founder and leader of the Socialist- Revolutionaries in Biale; and Chaninalle Kling, one of the leaders of the “Bund” in Biale, during its period of glory.

Pillev Prayer House

The Pillev (Pullavi) Chassidim had their prayer house in the home of Moshe Tuvia, on Proste Street. Before the Second World War, they had to leave the prayer house, and on the Sabbath and festivals they prayed in the Talmud Torah.

Mezritsh Prayer House

The Mezritsh Chassidm also wandered around from one location to another, until they settled in the house of Moshe Yitzchak Stollier at 29 Proste Street.

The eminent Chassidim there were: Reb Berish Urbach (of Viness) and the cantor Izshe Liebman.

The Aleksander Prayer House

This prayer house was situated in the courtyard of Reb Aharon Landau and later in the house of Meir Korman.

Aside from Reb Aharon Landau, the most eminent worshippers were: Reb Volvish Goldshtein, (son-in-law of Sh. Pizshitz), the Gampel family, the Rabbi, Reb Moshe Utshen, Reb Chaim Lieberman (of the Kozzes – a nickname), and Reb Aharon Zilberberg (Shkop – nickname).

The Lublin House of Prayer

Their place of worship was situated in the premises of Fyvele Melamed on Grabanov Street, but only until the First World War.

The Damatshev House of Prayer

They had their prayer house in the courtyard of Chaim Yaske Kashtenboim. People knew little about it, but it did exist before the First World War.

Shedletz House of Prayer

A prayer house like this, was created a few years before the Second World War, and was situated in Viness. Their prayer leader was Yechiel Urbach (a son of Berish).

The House of Prayer of the Opponents of Chassidism

This prayer house was situated on Vansk Street and was built as a synagogue, with a large reading desk in front of the lectern for reading the Torah, and a smaller one - in front of the holy ark. They also had a women's section.

The builders of this non-Chassidic house of prayer were stubborn scholars and religious artisans, adversaries of Chassidism. The entire fit out and accessories in the women's section were given by the renowned lady, Feige Frimmes (she had a house and a factory on Varshevve Street).

Eminent worshippers who belonged to that house of prayer, were: Reb Menkin Dine, Reb Nachman Rozenkrantz, the brothers Yehoshua and Eliezer Hoffer (of the Pyess) and their brother-in-law Reb Moshe (grandfather of Gittel Rozenblatt, New York).

When Reb Yehoshua died, it was told that in his will, he bequeathed to the prayer house, religious books to the value of 300 Rubel and also a sum of money (he made a good living, but was not a wealthy man. Typically, the children of the above mentioned distinguished persons, Reb Moshe, Reb Yehoshua and Reb Eliezer Pyess, were Chassidim).

The Tarshish House of Prayer

This was a typical Chassidic house of prayer and their worshippers were not the followers of any particular Rabbi.

They were mostly young people of Chassidic families, who were frowned upon in the Chassidic prayer houses, because they wore pressed collars with neckties, short forelocks, polished boots and clothes that were of good quality. In jest they were called “Jonah the prophet's Chassidim” because the prayer houses spat them out (threw them out).

[Page 261]

The founders of this prayer house were, Asher Hoffer (of the Pyess), Moshe Lebenberg, Yoske (Yosef) Vinograd, Asher Feigenboim and others.

The prayer house was situated at Asher Feigenboim's (carpenter) on Brisk Street. Later, until the First World War – in the house of Leibe Mendik. In the first years of the First World War – in the house of Asher Hoffer on Yatke Street. Later, until the Second World war – back to Asher Feigenboim. The leaders in prayer there were: Asher Hoffer (also the Torah reader), Binyomin Klieger, Moshe Lebenberg, Yakov Goldshtein, Leibele Krideshtein, Yossele Glezer (called a Rodzinner), Moshe Biebergal, and Shpiegel (from Lodz, son-in-law of Hersh Yakov Zshelazni).

The Society of Talmudic Students

There was a saying in Biale: “A Talmudic student says the blessing for wine over wood shavings”. For a young man it was impossible to secure a call up to the Torah. He had to wait until he was married. So, a group of young men got together and created their own prayer group. That happened at the end of the 19th century. The young worshippers later married but their prayer group was still called the Society of Talmudic Students.

The society reached a high level when their leader was Reb Moshe Mordechai, a man who was renowned in his time (called the Kesselerke's son-in-law – later went to live in Tsfat in the Land of Israel). He would study with the worshippers on the sabbath during the day, and in the evening, they arranged a third meal at the end of the Sabbath, with Sabbath hymns. After the departure of Reb Moshe Mordechai, a young man, whose name I do not remember, studied with the group. (He was the brother-in-law of the painter Chaim Yehoshua Blushtein).

Their place of worship was in the house of the brothers Moshe and Meir Zuberman. Later, in places where they received hospitality. Finally, in the women's synagogue, to the left, on the second floor.

They had two fine prayer leaders: Hersh Bernshtein (a tailor, who immigrated to Canada) and Yossele Platt (a shoemaker of Lashitz).

Original footnote

by Feivel Gold, New York

Translated by Ofra Anson

Biala, the town we loved and that we all miss, does not exist anymore, not even the sign of a grave.

Let us remember the cantors we all knew, loved, heard, and enjoyed. They did not use any technology or tricks when they prayed. They knew very well who they represented and to whom the prayer should be directed.

The old cantor

I never knew his name. He was very old, may have reached hundred years, and was a cantor in Biala for more than 60 years. He prayed solely, without any help, even on Saturdays, and because he held the position – no other cantor could be hired. Hearing the high tones on Saturday prayers, I knew he had a rich baritone voice when he was young.

Shimale Kreidstien

The most handsome person in the big synagogue. He was a cantor who served mornings and evenings and blew the Shofar. An old person with a small beard, gray hair and a beautiful young tenor voice. He was dressed like a Hasid rabbi. In his time, he was the only cantor who I heard singing the confession on Yom Kippur in the old, traditional, tune. Yosel Wetchik and Althar Cheshler were his assistants.

Aaron Yehiel Melamed

Aaron Yehiel Melamed was called Beile Hishes husband. He was born in Parczew, and served as a cantor during the High Holidays as long as the old cantor held his position. Before holding the service in Biala, he used to pray in the small settlements around Biala. He had a nice tenor voice, and used to cry a lot while praying. He reached high tones when he sung the prayer for the 10 persons assassinated by the Romans and considered to be as Jewish martyrs. He cried so hard, as if he himself went through the tortures.

Joshua'le – the new cantor

In his youth, he studied in Beith Hamidrash with the rabbi of Biala. He was a gentle young man, a scholar, and sang beautifully. He became a cantor due following the advice of the Rabbi, though he had lung disease. The orthodox Jews of Biala believed that the Rabbi helped him reach high tenor tones. Before he became a cantor in Biala, he worked in few other towns. In Biala, people took pride in having such a handsome and talented cantor.

[Page 262]

He organized a good, large choir. Biala was enchanted by his soloists, such as: alto – Yosele Solovei (Yosl Zied), Yankl Motl Kaves; Tenor – David Sara Rivkes (Hochberg); Bass – Shmuel Moshe Antsheliches. For me, his best composition was for “lo amut ki ehyeh” in the “Halel”. Second best was “venathna tokef”. In general, what he said or sang, alone or with the choir, was full of sweet feelings. On Saturdays, in “av harachamim”, when he got to “Kama yomru hagoiim…”, he sang it loud and with such pathos, we were sure it went straight to heaven.

Manes

Manes was the cantor of the big Beith Hamidrash. He was a Hasid of the old Rabbi of Lublin, the prophet. He was an old person, short, with a nice white beard, and a good bass voice. His Priestly Blessing (birkat hacohanim) was particularly original and beautiful. His assistants were Noah Shames and Pinie Beker (the father of Kotchemeinik).

Eyzshe Liebman

He was born in Lomza, and people called him “the husband of Sara Hanna Miriam's daughter”. Sara'le was the one who made the living. She had a big family, and run a food store in the shop of Moshe'le, the son of Yankel. Eyzshe used to sit in the Rabbi's Beith Hamidrash and study. He came into the store to wish it success.

When the cantor of Shaharit in Beith Hamidrash suddenly died, the Rabbi was asked to find a replacement. Thus, Eyzshe Liebman became the cantor after Manes died. He was the first cantor I heard praying “Ani ha'ani mima'as” in the traditional tune, and with a choir – his own children. He sang nicely, though there were people who complained that his voice was not clear enough. He used to pray with devotion and strength. His first-of-the-month blessings, Hallel, and Avinu Malkenu were particularly beautiful and original.

Feigale's Meir

Kotsk Hasidim loved Tikkun. Naturally, when you start a little Tikkun, dancing and singing are involved. Indeed, the Kotsk Hasidim had a reputation as the best music players.

Feigale's Meir (the writer's cousin), the son of Haim Ortcheles was the best cantor the Kotsk Hasidim ever had. Rabi Haim Ortcheles died very young in Biala, when his eldest son, Meir, was not even 13 years old. Yet, Meir had already learnt his father's sweet singing, and the Kotsk Hasidim in Biala liked him a lot. After the death of the Kotsk Hasidim's Rabbi, he joined the Pilever Hasidim (led by the Kotsk Rabbi's younger son). Sokolover Hasidim, whose rabbi was the Kotsk Rabbi's eldest son, were quite sorry he did not join them.

When the Shaharit cantor of Beith Hamidrash suddenly died, the Rabbi sent for Meir. Meir argued that his voice was not strong enough for Beith Hamidrash and that he was already committed for the Musaf in the Pelevers' praying place, but the Rabbi convinced him. He worked hard to learn the Ashkenazi prayers for New Year's Eve, and he prayed with the well known Kotsk devotion and sighs.

He is the only cantor of Biala that has a grave because he died in Israel.

Hershale the Rabbi's son

Hershale, the youngest son of Biala's Rabbi, sometimes served as a cantor. He had a high, young, tenor voice. The Hasidim in Biala used to compare him with Mendel Buchner. He played the violin, and prayed the Musaf with a large choir. His Kol Nidrei was a big success, and people came to hear him from far away. He had a very nice melody for “Yishtabach”, and the Hasidim in Biala adopted it. He had a very popular melody for “ve'ak kulam”, which became a folk song – “Yente Geneshe received a telegram saying that all strikers were killed”.

He was a rabbi in Siedlce, and died very young. His son became the rabbi of Biala in Tel-Aviv, Israel.

Mendel Azarekaver

He was a Hasid of Biala's Rabbi, and used to spend all the holydays with the Rabbi. He held the position of cantor in the morning prayers. Before the prayer he used to go to the Rabbi's Mikve, and his ginger beard became like a shining piece of red wood. He used to say “Hamelech” by the stage, and run with the same breath to the column, while the Hasidim moved to free his way. He prayed with such devotion, as if he meant to pull the heaven down to earth or the earth up to heaven.

[Page 263]

Moshe of Peia

Peia's Moshe was the cantor for the morning prayers in the Mitnagdim's praying house, together with Rabbi Mneke. He used to sing the first “The King” with such a force, that his voice became hoarse.

I do not know why, but the devil got hold on him, the eldest and distinguished member of a well-known family, and one of the handsome persons in the Mitnagdim's praying house. Each year he lost his voice during the high holidays, until he was in his 90s.

Menke the (daian) judge

Being a judge in Biala, where there were hundreds of certified Rabbis, was not a mean achievement. Rabbi Menke was the most handsome Jew in in the Mitnagdim's praying house, and led the Musaf. He had a very nice baritone voice. He prayed with all his heart and pain. His assistants were: Haim Naftcharz (Hoffman), Arie's Baruch Jacob, and a son of Yosel Miner. His Hakafot in Simhat Tora were well known.

Itzke Moses

Itzke Moses was married to the granddaughter of the Kock Rabbi. He was raised in the Warka Rabbi's yard, a decedent of a well-known Hasidic family. Yet, even without all that heritage, he was suited to be the Musaf cantor in the Gere praying room, where the aristocracy of Biala prayed. He was over 70 when I met him. He was one of the Geres' great scholars, with an aristocratic-patriarchal grace.

His sweet, deep, baritone came into full expression when he prayed “Ithgadal” during slihot, or “Barechu” on New Year. I remember he used to pray in tunes that were also popular among the Kock Hassidim. He had a choir of six singers, three of whom – Leibish Commissioner (Heibloom), his brother Simha Heibloom, and Itzhak Lipes – were cantors themselves in the Gere praying room. The first in Biala, the second in Losice, and the third in Miedzyrzec. The other three singers were: Hershele David son of Iizik, Yoske Yehiel Hersh, and Moshe Yenterl (who died in Israel).

Mendel Buchner

Mendel Buchner was married to Yocheved, the daughter of Rabi Noah Musinke. It means that big Moshe, small Moshe, and the Gere's rabbi (who recently passed away in Jerusalem) were his in-laws. He had a nice voice, good diction; he was clear and composed nice tunes. He was much respected in the Gere's praying place. He led the morning prayers on Saturdays and holidays, and took on leading the evening prayers after Itzke Moses left Biala. He had no help, and figured out how to present clearly the most difficult prayers.

His tune to “kachomer beyad hayotzer” (like putty in His hand) was based on a folk song “Everyone knows that there is no school on Sunday”. This tune was arranged by Joseph Rumshinsky and sang by Molly Picon in the play “Yankele”.

Leibish Ortcheleres

Leib Commissioner (Ortchelers) resembled Mendel Buchner. He liked the stage, and prayed with Hassidic ecstasy. After Mendel Buchner took on the leading of the evening prayers, Leib became a candidate for leading the morning prayers. Yet, his business, which involved long hours of daily train riding, was an obstacle. He used to go to Warsaw to buy merchandize and distribute it, so leading the morning prayers was physically impossible. After WWI, when his children had already left home, telephone connections and automobile transportation allowed him to quit traveling, and he became the morning cantor of the Grere praying place.

Whenever I think about my relative Leibish Ortchelers, I remember the way he used to sing El Adon on Saturday.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Biała Podlaska, Poland

Biała Podlaska, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 21 Feb 2021 by JH