|

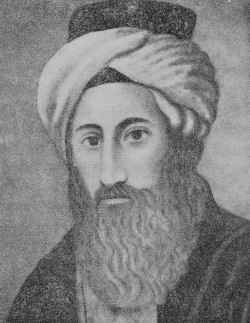

(Grandson of Rabbi Joseph from Biala)

|

|

[Page 3 Hebrew] [Page 5 Yiddish]

Translated by Marc Zell

Two events in our generation shocked and fundamentally changed Jewish history – the destruction of the Jewish diaspora in Europe and the renaissance of the nation's political life in the Land of the Patriarchs.

These two events are influencing and will continue to influence the course of Jewish history, in ways that we cannot now foresee, because we are far too close to the events to be able to assess their meaning for all time. Therefore, we cannot today resolve the connection among these events and how they affect one another.

Now, at this time, it is only possible for us to see the results that confront us directly: concentrating the remnants of the Holocaust – the most important among having laid the foundations for independent existence in Israel, and the others which are laying the basis for renewed dispersals or maintaining those that now exist, the majority of which are located beyond the oceans and a minority in the countries of Western Europe.

The centers of these two types are continuing and nourishing one another overtly and covertly. One of the concealed paths of such mutuality is –– the amity among townsfolk which has increased after the Shoah. People who left the cities and towns many years ago, departed without a second though, lifting their eyes to what lay before them, toward a personal future in hope and not looking back to those places in a kind of organic or organizational completeness, other than the narrow circle of the families who remained to them there. After the Shoah and the loss, the eyes and hearts of these same people began searching the world for a Landsman as if he had been a brother from birth. Sons of families who had been destroyed found some slight solace in their Landsman family and in the hands of brothers extended overseas and continents.

They strove for this fellowship in different ways. Different devices for extending assistance to brothers who survived the Holocaust were created or strengthened. Landsman societies were founded, different funds and institutions, all with the intense desire not to allow the memory of their town to be forgotten. In lieu of the body of the town that had been burned, they wanted to protect the memory of its soul. That is the reason for books about the history of different towns and hence the reason for this book about our Biala.

We have not intended in our book to glorify and exalt our town, but merely to tell its story. Biala was not a mother to the Jewish people in Poland, but rather one of its daughters. And it is about this daughter, whose memory is so precious to us, we shall tell. We will tell about its lights and its shadows, about the lights that illuminated its skies and about the clouds that darkened them; about the great men of the Torah, both revealed and concealed, and the great Hasidic leaders who settled there from distant generations until its destruction and about the simple folk; about those who fought for free thought who arose in the last two generations of effervescence and rebellion, about the political and social movements that gave it voice and about the stuttering masses.

We shall tell and revive the memories of the periods of her vibrant life and mollifying the time of the bitter end that came so fast and we shall bewail the Holocaust and the loss of those souls so dear to us all, who painted the life of our town in a bevy of colors.

[Page 4 Hebrew] [Page 6 Yiddish]

All of the material was collected in Yiddish, with the exception of a few articles in Hebrew. We thought it appropriate to leave each article and the historical overview in the original language written by the author, because it was beyond our financial capacity to publish the book in both languages. The historical overview of the early generations of Dr. M. Handel, was written by him in Hebrew and Yiddish and the overview of the later generations up until and after the Shoah by M. Y. Feigenbaum and the history of the Zionist Association by M. Bruhel were translated into Hebrew and appear at the beginning of the book. We must also thank Mr. A. L. Faiyans for the translation of the overviews; he gave us his precious time and his blessed pen.

We also wished to recall for all the world the list of souls who finished the last page in the history of our town, but we were not able to do so. We asked those who had come from our town through the Diaspora to send back a special form with the names of their relatives killed in the Shoah, but we only received but a few dozen responses. We therefore were forced regrettably to abandon this effort.

For the reasons mentioned, only group pictures of the political, cultural and social of our town are presented hars and ere. For some of these photographs we thank our landsman Yakov Aronovich (Buenos Aires) who provided us with the negatives.

This book is the fruit of the labor of our landsman M.Y. Feigenbaum, whose took the initiative to collect, research, edit and arrange the material. He also wrote some of the surveys himself. He was engaged in this work for more than ten years taking pains to garner every piece of information about our town from the memories of our landsmen and those who were not from our town; clarifying and checking every little detail from that which was written and told to insure its truth and value.

We owe special thanks to the historian, Dr. M. Handel (Tel Aviv) for his comprehensive overview of Biala from the time of its founding during the Jewish exile to Poland until some 100 years ago. Likewise we are grateful to the researcher and author, Mr. M. Edelbaum (New York) for his lovely review of the rabbinical dynasties who over the generations occupied the rabbinical throne in Biala and for his review of Hasidic Biala and to those who prepared the articles about the political and social movements who through their personal participation in them succeeded in giving life to their descriptions of their development and activities. And a word of thanks to all those who openly or anonymously contributed to this portrait of Biala as set forth in our book. Above all thanks from the bottom of our hearts to the Holocaust survivors who told us of their experiences and their eyewitness accounts of our community's last days.

The publication of this book would not have been possible with the financial assistance of the émigrés from our town first and foremost in Israel, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Australia, Canada and Paris.

Finally, we must mention the two committees selected by us: one who assisted M.Y. Feigenbaum in the final editing of the book by reviewing, clarifying and screening the material and the second which helped administratively. We do not mention the members of committees who were public representatives of the emigrants from our town in Israel and who carried out the wishes of us all.

Biala is lost and no more. Together with all of the holy communities of the Jewish Diaspora in Poland, Biala was consumed by fire, sword and gas with all its holy martyrs. We shall remember her in our hearts forever.

Publishers

Biala Podlaska Jewish Community Kupat Gemilut Hesed

Tel Aviv

Elul 5720

September 1960

by Dr. M. Handel, Tel Aviv

Translated by Marc Zell (Pages 9-14)

and Dr. Ida Selavan Schwarcz (Pages 15-21)

A. Biala the Town

Ancient Poland comprised two parts: Crown Poland and Lithuania. Biala, which lies close to the border between these two lands, belonged to Lithuania. Polish cities were divided into two types: Towns belonging to the Kingdom, whose residents were had the status of municipal citizens and private towns that were founded by members of the aristocracy on their lands. Biala was a private town, owned by the Radziwill princely family, whose extensive landholdings, numerous armies and the high positions they held in the in the political machinery of the state transformed them into a major force that gave little consideration to the laws and regulations of the state. The center of the Radziwill's “kingdom” was the town of Nesvizh; but there were periods when Biala also occupied a central position.[1]

Among the members of the Radziwill family were princes who had an extraordinary reputation for strange practices, whose wild caprices were celebrated throughout Poland. Obviously, their rule was harsh blow to their subjects –– Jews and Christians alike. One of the Radziwills had a passion for going sledding in summer. He would order that salt be spread out along the track. Another Radziwill “ran out of” birds to hunt; he would place a Jew in a tree and command him to whistle like a bird and then would shoot him. It was told that one Radziwill (in the eighteenth century) had a kind of affinity to Judaism. He would only select Jewish advisors, he learned Yiddish and Hebrew and would wear a four–cornered garment [Transl. talit katan] on Sabbaths together with his military medals. The family wanted to detain him and placed him under special supervision – first at the palace in Biala and afterwards at Slutsk – but he failed to cut off his ties with the Jews and there are those who say that the Jewish community in Slutsk suffered greatly as a result. The Rabbi of Slutsk was placed under arrest in Biala. The whole affair came to an end only upon the death of this “Judaizing” prince in 1781. Historians also mention good rulers who cared about their subjects and were recorded as being kind governors. Thus, for example, the historian, Bertoszwicz (a native of Biala), writes about Princess Anna, under whose reign Biala was content and a refuge for the poor. The cities inhabitants – Jews and Christians – profited from commercial negotiations with the Court and from labor and financial transactions. But by the same token the rulers put pressure on the town, saddling it with various taxes and burdens.

Among the town's institutions the Academy deserves special mention. It was a kind of intermediate secondary school between high school and university. The city was under an obligation to contribute to the institution's budget, but it also benefitted from it – through trade and supply transactions. The students were cautioned not to deal badly with the town's residents, not to abuse them verbally and physically and not to carry weapons without the rector's permission. The fact that this warning was included in the oath each new student had to take proves that the relations with the town had not improved and there were clashes certainly occurred more than once. We know from other towns that students were very often the cause of riots against the Jews.

The Polish author, Kraszewski, who had a great interest in Biala, writes that that the town did not have a rich history. “It was focused on itself for itself.” Nevertheless, it is worthwhile noting that the town experienced several historical events, in addition to political events in the stormy history of Polish parliamentarism and partisan politics in which the Radziwils participated quite actively. We will cite several occurrences: in 1665 the Lithuanian Senate convened in Biala. Three years later the Polish King Jan Kazimierz visited the town during the Northern War at the beginning of the 18th century in which Poland was allied with Russia against Sweden and the town was conquered by the Swedish army. In 1789 the Emperor Jozef II passed through the town returning from his visit to St. Petersburg. The foregoing events (save for the Swedish occupation) only had a marginal effect on the town's population. Another type of event affected the people of the town greatly: these were the frequent fires that plagued the town over the centuries. One must remember that the town was built entirely of wooden houses. Characteristic is the comment of Bartoszwycz: “There were always fires in Biala. It was burned down time after time and then regularly rebuilt.” After one of the fires – during the Swedish conquest, when a plague broke out in the town (1711) – it turns that in Biala and its nearby villages 559 souls were injured, among them according to a declaration made by the leaders of the “Municipal Citizens Community”, Kappel ben Yitzhak and Shmuel ben Meir, 37 Jewish souls.

B. The Biala Jewish Community

Within the framework of the structure of Jewish autonomy in Lithuania, the Jewish community of Biala was within the area ruled by the Brest–Litovsk Jewish congregation, which together with the Jewish communities of Vilno, Pinsk, Grodno and Slutsk comprised the highest organization in the Autonomy: the “Council of the State of Lithuania.” When the representatives of the Jewish communities within the Brest–Litovsk government district met in 1705 to divide up the responsibility for the royal tax to be paid by the Jews as a head tax, Biala was assessed a total of 510 gold zlotys, the third largest amount after Brest–Litovsk (1,384 gold zlotys) and Wysoka (700 gold zlotys). Those paying less than Biala were Prozana (485 zlotys), Woldowa (400 zlotys) and Siedlice (230 zlotys). This gives one an idea about the place Biala had among the cities and towns of the Brest–Litovsk District.[2]

[Page 10]

We do not have any reliable information about the time when Jews settled in Biala and the establishment of the Jewish community there.[3] In the record books of the customs post between Crown Poland and Lithuania, at Bielsk and Lukow from the year 1580[4] mention is made of Jews passing the post with merchandise, who were from Tiktin, Bielsk, Wengrow and Kotsk, as well as Christians from the towns of Czynowyce, Loszyc, Bielsk, Kobryn, Miedzryzec, Brest–Litovsk and Pinsk. There is no mention of any Jew or Christian from Biala. Was this just a coincidence? One must assume that it was precisely in connection with the border trade between Poland and Lithuania that the Jewish community in Biala was founded. The first information that has come down to us about Jews in Biala is connected with the Land of Israel. A Jew from Biala, R. Uri bar Shimon emigrated to the Land of Israel at the end of the sixteenth century and settled in Safed, which at that time had distinguished itself as a center of economic and spiritual success. He was sent from Safed to Europe to organize the collection of charitable donations for the Jewish community in the Land of Israel[5]. In 1575 we find R. Uri in Italy, where he prints a list of the holy gravesites in the Land of Israel. As to who this R. Uri when and when he left Biala nothing is known. In all probability this was a Jew who was a seasoned world traveler, if he was selected for such a responsible position by the Safed Jewish community. In any event, thanks to this R. Uri, we are able to establish that in the last quarter of the Sixteenth Century there was already a Jewish settlement in Biala. It is worth noting here that in the field of emissaries sent from the Land of Israel to the Diaspora, Biala occupies a place of considerable distinction. The important emissary, R. Chaim Yosef Azulai who lived in the Eighteenth Century was the grandson of a Jew from Biala. We will speak about this in the following chapters.

The first actual information we have about the Jews of Biala comes from 1621. One get the impression that by that year the Jewish settlement in Biala was already quite well established. As in other Polish towns, disputes between Christians and Jews multiplied on issues concerning the right of settlement and to engage in trade and artisan. The Radziwill Prince found it necessary to settle their mutual relations in a formal document. We learn from this document important details about the Biala Jewish community. From earlier years, the Jews of Biala had already obtained written charters granting them rights from the Prince's court, under which they were released from various levies due to the court. They were obligated to contribute to the town's budget six grosh per family (one grosh was 1/30 of a gold zloty). Their principal occupation was commerce and as merchants most of them lived in the town center (”Rynek”) and the surrounding area. However, from that date, i.e. 1621, they were forbidden from living in the town center and the total number of houses allowed to them anywhere in the town was limited to 30, with one family per house. They were allowed to engage freely in trade in these houses and only these families were released from the levies in favor of the Court and only they had the right to pay no more than six grosch to the municipal treasury. But there is a clause which shows that the number of Jews in the town was larger. That clause provides: “If it eventuates that the Jews of Biala have more than 30 houses, then they shall be obligated to pay all of the debts owed to the Prince and the town in same manner as the Christian population.” This was the economic situation during the Seventeenth Century. However, the 30–family house limit was in fact non–existent, since their number increased continuously.

The right of autonomy of the Jewish community was, it would seem, very limited. The Court intervened in all internal matters. The budget of the Jewish community was subject to the Court's approval. So too was the decision to engage a Rabbi, to such an extent that there were instances where the Prince discharged a rabbi and replaced him with a rabbi of his own choosing. This was the situation in the Eighteenth Century. There is reason to believe that the situation had been better beforehand and worsened with the general economic decline throughout Poland and the increase in anti–Semitism that resulted from the religious fervor that was on the rise at the end of the Seventeenth Century. To illustrate this, we bring two contracts between the Prince and the Jews under which he leased the revenues from the landholdings of the Biala palace. One was from 1645 and the other from 1736. In the first contract with a Jew from Brest–Litovsk (Pinhas ben Shmuel), R. Pinhas was granted the right of adjudication over the village populations (the “Tax Lease Lord” or “his officials”). It was only with respect to crimes carrying the death penalty that the Prince reserved the right to add a judge of his choosing. Even in cases involving freeholders (not permanent peasantry) R. Pinhas had the right to propose the judge, a member of the landed gentry. By contrast, the contract from 1736 with a Jew from Biala named Shmuel ben Yitzhak, who bore the title: “the loyal, the factor, and general treasurer”): “in serious crimes the factor Shmuel is prohibited from judging and punishing his subjects, and a Jewish hand shall not touch a Christian.” The difference is striking and needs no explanation; in the one the “Tax Lease Lord” and the other a mere “Factor”, even though this factor held an important position as being in charge of a portion of the Court's treasury.

We shall now see how this limitation on the autonomy of the Jewish community was expressed in the Eighteenth Century. Reference is made here to four documents: two from the year 1736 and two from the years 1763 – 1765. In 1736 Princess Anna was approached to “make order” in the Jewish Community and she commanded the above–mentioned general treasurer, Shmuel ben Yitzhak, to “look into” all of the affairs of the Jewish community and “prepare a budget of income and outlays.” The Jewish community was ordered to submit all of its books and papers to R. Shmuel and to obey all of his directives and “not to do anything without his knowledge.” R. Shmuel was granted the authority to dismiss the elected management of the Jewish community and to appoint new management, should the Community not obey him. To give her decree further validity, the Princess ordered that this directive be published in the Synagogue. It would seem that the Princess also had the best of intentions to act on behalf of the poorer strata of the Jewish community. In her decree she expressly stresses that that the budget must be prepared in such a manner as not to favor the rich at the expense of the poor and that one should not suffer for the benefit of another. Thus, we have a clear picture about the social tensions within the Biala Jewish community, tensions which prevailed in all the Jewish communities and, in the opinion of historians, caused serious challenges to the Jewish autonomy as a whole. As to how R. Shmuel acted relative to the social goals desired by the Princess is difficult to know. But we do have one explicit clue: In the year 1748–1749, a not very large tax of 15 gold zlotys was registered on the account of R. Shmuel (actually he only paid 9 gold zlotys) and in the year 1749–1750 he is paying even less, not more than seven gold zloytys). This R. Shmuel was quite clearly a very rich Jew. His tenure as general treasurer certainly brought him large sums and if he held his position in the above–mentioned years, it may be asked why he paid such small amounts to cover the municipal budget at a time when others were paying up to 250 gold zlotys!

[Page 11]

Let us return to the orders of 1736. A great outcry arose in the Jewish community and there is reason to assume that there was a call to excommunicate R. Shmuel for having undertaken such great powers against the Jewish community. However, the Princess did not relent. For her this was not a question of Jewish autonomy, be it broad or narrow, but rather a matter of demonstrating her prerogatives and protecting her interests. Any Jewish community that dared to oppose her, was no longer in her estimation, good security from a fiscal perspective for her interests and affairs. Therefore she began to act. Three days after issuing the foregoing orders with the power of attorney in favor of R. Shmuel, she removed the Rabbi from his office and imposed a large fine upon him of 100 red zlotys. R. Shmuel was ordered to appoint a new rabbi. In the preamble to her judgment the Princess emphasized that the reason for her actions was fiscal: that transferring the authority to R. Shmuel was intended to increase the Court's revenues from the Jewish community and that the community and the Rabbi had wanted to harm her interests. It is not known how long R. Shmuel ruled over the Jewish community. From a chance article found in a German newspaper from Danzig, it may be gleaned that by 1751, R. Shmuel had departed this world.

And now for the documents from 1763–1765: The Prince announced: “Various parties have praised the scholarship and humility of one Yosi ben Yaakov. Therefore I appoint him Rabbi of the Biala Jewish community.” To Rabbi Yosi the Prince granted the right of adjudication and reserved to himself the right to hear appeals. The appointment was for six years (that is until 1769). The new Rabbi wanted to assure a permanent appointment for himself and for which he undoubtedly paid a fair price. For his efforts he obtained official approval from the supreme authority for his office, from the Minister for the Interior in Warsaw. It is unfortunate that we do not have any information about the manner in which the new Rabbi exercised his authority or about how the Jewish community reacted to him. In any case, it is clear that in the eyes of the Prince, the autonomy of the Jewish community was not a reality. He made use of Jews who were ready to serve him even if it was against the Jewish interest: that his how the tax lessor Shmuel acted as did Rabbi Yosi.

C. Biala's Jews and Their Economic Situation In The Mid–Eighteenth Century

The Jewish population of Biala in the mid–Eighteenth Century stood at 110 families, each one of which had their own house. In addition there were another 90 families of “Kamarniks”, i.e. subtenants of other Jews. Based on an estimated five souls per family (husband, wife and three children), there were, therefore, some 1,000 Jews living in the town. It should be remembered that the statistical data from that time are very complicated and not very accurate. In one list the suburb of Wolya is counted along with Biala, while in another list only Biala is listed. One list includes all of the Jewish children in Biala, while in another only children over the age of 10 are counted. One list counts houses (dymy chimneys), while another list deals with families or home–owners. Plagues and fires also scrambled the numbers. One must forget as well that all of the population statistics made for purposes of taxation are as a rule inaccurate, since one cannot know how many of the residents evaded the census. Most of the statistical lists were intended principally for purposes of fixing taxes. The determination of the fact that the Jewish population numbered approximately 1,000 souls cannot therefore be anything other than an estimate that approaches the truth, but it is not accurate for all purposes. In any case, it would appear that the Jewish community was not small. We know, for example, that the Lublin Jewish community (without its surrounding villages) in 1764 numbered 1,383 souls; the Jewish community in Lukow: 543; Radzyn: 537; Siedlice: 332, excluding children under the age of one. In comparison with these communities, Biala was therefore very well populated. For the year 1742 there has been preserved in the Radziwill archives in Warsaw a list of Biala residents by street. Even it is not accurate for all purposes, it gives an informative picture of the town's population. (The table appears on page 12).

[Page 12]

| Street Name | Christian Houses |

Jewish Houses |

Christian Families |

Jewish Families |

Comments |

| Town Center (Rynek) | 14 | 17 | 14 | 18 | |

| Brest–Litovsk Street | 20 | 22 | 24 | 34 | The Jewish hospital was located here |

| From the Blonia to the Rynek | 23 | 2 | 27 | 3 | |

| In the direction of the Reformation Church | 15 | 0 | 22 | 0 | |

| From the Reformation Church to the Wolya Suburb | 6 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| From the Reformation Church to Jurdyczne Street[9] | 6 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |

| Lublin Street | 7 | 0 | 8 | 0 | |

| Lublin Street–Jurdyczne | 15 | 0 | 18 | 0 | The Christian hospital was located here |

| Plebanska Street after the Fara[10] | 15 | 0 | 17 | 0 | |

| Behind the Church | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | |

| Town Street from Plebanszczyzny | 7 | 4 | 9 | 6 | |

| Mezritch Street | 31 | 7 | 35 | 10 | |

| Potters Street (Garncarska) | 17 | 0 | 18 | 0 | |

| Losice Street | 16 | 22 | 17 | 28 | |

| From the Synagogue to the Cemetery[11] | 19 | 12 | 20 | 20 | |

| Janow Street | 25 | 1 | 29 | 1 | |

| Behind the Synagogue to Janow Street | 0 | 24 | 0 | 45 | The Synagogue was here |

| TOTAL | 242 | 112 | 281 | 166 |

What does this list teach us? Here are several conclusions:

[Page 13]

a debt for different work done: 2, 836 gold pieces, including amounts owed to tailors and furriers totaling 869 gold pieces and a debt to engravers for 1,384. Beyond all this there is a list of miscellaneous debts, large and small. Illustrative proof of how much the Prince did not meet his financial obligations may be found in the accounts of 1780. In that year the Prince owed the Jewish community the sum of 3,756 gold pieces for wax[13]. The Jewish community received on account of this debt 400 gold pieces in cash and another 40,000 bricks in lieu of 900 gold pieces. The Prince undertook to pay off the balance of the remaining debt in the amount of 2, 456 gold pieces in one year, but this debt actually remained on the books in 1795 as part of a debt of 5,000 gold pieces that had accumulated over the years. To settle this debt the Prince undertook to set off this amount against the sum the Jewish community was paying him for the Karawka[14] in the amount of 500 gold pieces per year (that is a 10–year arrangement).

The make–up of the citizens of the Jewish community seen from the standpoint of their economic situation will be clarified for us based on the tax list from the mid–18th Century. Still one must be careful to say that the resulting picture is not precise. Like today the rate of tax paid by a citizen does not faithfully reflect his true economic situation. But it nevertheless possible to get a sense of the situation that is both real and credible sense from the following table:

| Did Not Pay Any Tax | 27 individuals in the Jewish Community |

| Less than One Zloty Paid | 3 |

| 1 – 5 Zlotys | 26 |

| 6 – 10 Zlotys | 46 |

| 11 – 15 Zlotys | 25 |

| 16 – 20 Zlotys | 25 |

| 21 – 30 Zlotys | 20 |

| 31 – 40 Zlotys | 12 |

| 41 – 50 Zlotys | 9 |

| 51 – 60 Zlotys | 8 |

| 61 – 70 Zlotys | 3 |

| 71 – 80 Zlotys | 2 |

| 81 –90 Zlotys | 1 |

| 91 – 100 Zlotys | 1 |

| 101 – 150 Zlotys | 3 |

| 151 – 200 Zlotys | 1 |

| 201 – 250 Zlotys | 1 |

| Over 250 Zlotys | 1 |

| TOTAL | 214 Taxpayers |

If we define people paying taxes of up to five zlotys as being poor, up to 40 zlotys as middle class, up to 100 as rich and above this as extremely wealthy, we get the following composition:

| Poor | 56 | 26.2% |

| Middle Class | 128 | 59.8% |

| Rich | 24 | 11.2% |

| Extremely Wealthy | 6 | 2.8% |

| TOTALS | 214 | 100% |

It should be noted that a majority of the people in the middle class were artisans.

D. The budget of the Biala Jewish Community for the year 1748/1749

| Revenue | Expenditures | ||

| Direct Taxes (Property Tax and Head Tax) | 3,133 zl. | Royal Tax | 1,035 zl. |

| House Tax | 661 zl. | Taxes Payable to the Prince's Court | 2,609 zl. |

| Direct Tax from Village Lessees and Holdings Belonging to Biala | 604 zl. | Payments to the Priesthood | 2,534 zl. |

| Income Tax from Minor Commerce | 900 zl. | Gifts to the Priesthood and Court | 365 zl. |

| Meat Tax (Karawka) | 3,225 zl. | Municipal Tax | 112 zl. |

| Special Tax for Covering the Conversion of the Prince's Funds | 231 zl. | For the Needs of the Community | 1,467 zl. |

| Income from the Mikveh and Bath House | 150 zl. | Miscellaneous Expenses | 529 zl. |

| Penalties and Fines | 15 zl. | Debts and Interest | 2,075 zl. |

| Tax on Empty Lots | 30 zl. | Remanent (Depreciation) | 342 zl. |

| Loans | 1,079 zl. | ||

| TOTAL | 10,028 zl. | TOTAL | 11,068 zl. |

Before analyzing these data, a few notes about the mechanism and management of the finances of the Jewish community. Outwardly the Jewish community appeared to be a unified body and its management was the official representative and interlocutor between all of the individuals and all the extrinsic institutions. On taxation matters, therefore, all the undertaking and responsibility for payment did not fall on the individual but rather on the Jewish community as a whole.

[Page 14]

The community had three possibilities for collecting the necessary funds: (a) to impose a direct tax based on the economic situation of individual members of the community; (b) to impose indirect/excise taxes on the primary essential commodities, such meat etc.; and (c) to use both of the foregoing methods and when the these did not supply what was required, to go into debt and take loans from Gentiles and Jews including payment of interest, which meant burdening the budgets for coming years, in the hope that perhaps they will be better. The Biala Jewish community followed all three paths, like the other Jewish communities in Poland–Lithuania.

For purposes of assessing the direct tax, the Jewish community used to select a committee of appraisers which operated in accordance with a fixed procedure. We do not know the details of this procedure, because the registry of the Jewish community was not preserved. In any case one should remember that the level of tax paid was also used as a key to allocating social and political rights. Only those who paid the highest “sum” were entitled to exercise the active and passive rights in electing the institutions of management. Those charged with tax collection were the trustees and beadles. It would appear that these people also were assisted by officials of the Court. Indirect taxes were leased out and the tax lessee had himself a fair income from this activity. Frequently the tax lessees had troubles, when the Prince set the tax rent at a high rate or when he insisted on a regular supply of meat. There is one entry in the documents of the payment of a bribe in the amount of 60 zlotys to a kosher food inspector by the Court for not being too strict about his duties.

We turn now to the details of the budget and begin with the expenses. The Jews were paying two types of taxes to the Kingdom: house tax at the rate of approximately 8 zlotys per house. In the subject budget year this tax totaled 537 zlotys and applied to 70 houses. The second type of tax was the head tax (”Chraga”), which the Jewish community used to pay in a fixed amount through the Jewish community of Brest–Litovsk. In the subject budget year Biala paid 498 zlotys head tax. This was the custom until 1764. In that year the central autonomy of the Polish–Lithuanian Jewry was abolished and the head tax was from then on levied personally in the amount of two zlotys per person, except for children under the age of one year. The payments to the Court had tripartite character. One type of payment was actually in exchange for the Court's services for the benefit of the Jewish community, such as rental payments for lots on which Jewish houses were standing. The second type of payment was gifts made on various occasions. The third type was payments made in accordance with the feudal regime, paid by all of the princes' subjects, and in the first instance, the farmers. Out of the 2,609 zl. Only 609 were for services rendered for the benefit of the Jewish taxpayer. The remainder (in the amount of 2,000 zl.) were payments of the second and third types.

And here are a few line items: horses and carriage for various needs of the Court (travel to Warsaw, field work), fence repair, lighting for the Court guard, for renewal of the Jews' privileges, holiday presents, gift for the birthday at the Prince's Court, etc. Included in this category was also the payment of 808 zlotys to cover a deficit caused by a devaluation of currencies. There were various currencies in circulation in Poland and their real value was constantly in flux. The Prince paid his service providers their wages at the exchange rate that was most beneficial to him and the difference with respect to the real value was paid by the Jews. Here too are some other details about the payments to the Court treasury which are difficult to determine into which category they belong: “To settle matters when many Jews from the masses did not want to pay taxes in accordance with the existing custom;” for lawsuits against male and female storekeepers who did not want to pay according to the ancient customs;” “to settle affairs when the Jewish community did not wish to purchase rye and barley that the Court had imposed on them an obligation to buy;” “bribe for an officer so that he would treat well a representative of the Jewish community who was under arrest;” “for the maintenance of Jewish prisoners locked up in the Palace jail. Behind each payment of the foregoing types there lurked a poignant reality![?]

We see that the Prince knew how to satisfy himself for the kindness he bestowed upon the Jews by allowing them to live and earn a livelihood in Biala. He also knew to insure that his revenues would not be suppressed by the other financial undertakings that applied to the Jewish community. Thus we hear, for example, that the Biala Jewish community is requesting that Brest–Litovsk reduce the rate of the head tax by 158 zlotys (340 zl. instead of 498); the reason: lack of financial ability to pay. The shortfall caused by the concession made to Biala will be paid by another Jewish community, but the Prince was not prepared to relent and claimed what was due him down to the last penny.

Payments made to the priesthood were to a small extent interest on monies lent, but were largely gifts to the priests and the churches, monks, nuns, to the Academy for its teachers and pupils, to the old age home adjacent to one of the churches, to purchase tallow and candles for the churches. All of these payments, in amounts exceeding 1,000 zlotys over and above the expenses for the needs of the Jewish community, are striking proof of the feudal regime in which the priesthood occupied a privileged status equal to that of the nobles. With respect to the administration of the town, the Jewish community was almost entirely independent of it. The Jewish community and the town were two separate units subject to the Prince. Still the town had priority and the Jewish community was liable to compensate it as well with gifts and to contribute to the maintenance of the town administration: the mayor, the chimney sweep and others.

The item for the needs of the internal affairs of the Jewish community (1,467 zlotys) did not make up more than 13.25% of the total budget. This fact says much and needs no interpretation. Even if we were to add to this the line item for miscellaneous expenses, the picture would not change significantly. Among the expenses for the needs of the community the largest item is for the wages of clerics and the officers of the community. The rabbi receives 360 zlotys and his dwelling; the trustee 224 zlotys; the preacher (magid) 156 zlotys. After them come the beadles, the gabbais charged with social welfare and for distributing pletten to the poor[15], the ritual slaughterer, the cantor and choir, community servants and the night watchman for the community. Community officials got more meat for holidays, boots and other services. It is worth noting that the community was not particularly meticulous about meeting its obligation to make these payments. For the year in question the rabbi received only 166 zlotys (the following year only 93 zlotys), the preacher only 57 stringent, because the eye of the Prince was always watching and showed no willingness to be lenient. The line item for “wages” says 969 zlotys, namely about two–thirds of the expenses for the community's needs. In second place was social welfare, donations and contributions for wayfarers and itinerant preachers. Every preacher who came to town received financial support from the community along with travel expenses for the continuation of his journey. In the subject budget year, not less than 26 itinerant preachers visited Biala (from Horochow, Korow, Lvov, Pinczew, Astra, Przymysl, Jaborow, Sluck, Radzyn and Tiktin). Yeshiva students also came to Biala, a wedding that was held at poor widow's, an emissary from the Land of Israel or a cantor or emissary from the Brest–Litovsk Jewish community in connection with settling up the Chraga tax,

[Page 15]

occasionally destitute Jews would come to town, from Poland or abroad (in the subject budget year two emissaries from distant Prague came to Biala to collect alms). Anyone in need would apply to the Parnes (Transl.: a well–to–do member of the Jewish community) of the month[16], who would groan and respond with a generous or parsimonious hand, according to the circumstances. In 1748 these various donations amounted to 234 zlotys and the community found itself in dire straits, since no such sums had been included in the budget approved by the Prince. The Jewish community even sent a special delegation to Brest–Litovsk asking them to have pity on Biala Jewish community and not to send any more itinerant preachers and poor people their way. It appears that this request was effective to a small degree. In 1749 the Jewish community only expended some 66 zlotys for these purposes. But in subsequent years the number of mendicants grew even more, since there was great suffering and the Jews had become quite impoverished[17]. In third place were expenses of a representative communal nature. An important guest would arrive in town, a rabbi or Parnes from another Jewish community and the Parnes of the month would honor him with liquor. Apparently he had the capability of bringing out up to two bottles of mead (one bottle cost 19 groschen). In Biala there were visitors from other Radzwillian towns who came to make various arrangements with the Court; these visits too resulted in additional expense: in 1748 24 zlotys and in the following year 34 zlotys. Included among expenditures of this type were liquor shipments for weddings of wealthy proprietors. In the subject budget year there were eight such weddings which cost the community some 14 zlotys. The fourth place was held by expenses of an administrative nature: drinks for appraisers who were engaged in dividing up taxes, food for “arbitrators” who took care of running the elections for the management of the Jewish community, expenses for preparing the contract for leasing out the Karawka, inspecting the mikveh, the community property and the trade stands owned by the Jewish community.

We must still turn our attention to the expenses for covering debts subject to interest. In all the history of the Jews of Poland this problem was known to have reached its greatest importance in the Eighteenth Century. With the rise in impoverishment (the number of itinerant preachers is one of the more outstanding indicia of this) and with the increase in the burdens imposed upon the Jewish communities, debt spread and mushroomed. In 1764, the year that central Jewish autonomy was extinguished, it was discovered that that the communities' debt had reached the sum of 2.5 million zlotys. The communal debt rose even above this amount. We do not know precisely what the situation of the Biala Jewish community in this regard. Based on the sparse information available to us, one may assume that its debt was not particularly high, “thanks” to the Prince's system of administration which did allow the Jewish community to go into debt and in any such instance demanded a detailed accounting. This was the case, for example in 1745 when the Jewish community wanted to take a loan in the amount of 3,000 zlotys from a member of the priesthood. And with respect to the last line item: “Remanent”: this item had its origins in the fact that revenues from taxes were recorded as “outstanding” at a time when in actuality many taxpayers were unable to pay the tax obligations imposed on them, or were late in paying, or had died or left Biala, forcing the Community to write off the amounts either on its own initiative or at the direction of the Prince. In the subject budget there are 62 such cases of write–offs: 8 of which were due to Jews who had left Biala, six due to death and five cases where the Prince demanded that the amounts be written off. Two of these cases where officials of the Jewish community were relieved from their tax obligations and two cases where the tax was paid by labor for the Prince in lieu of cash payment. The depreciation amount of 342 zlotys out of such a large budget proves that the tax collection mechanisms worked quite strictly and was difficult to evade. The one who benefitted most from this was, of course, the Prince. As an example, we have a striking case from 1742. In that year a new contract was made with the tax lessee of the Karawka tax and the Prince insisted on setting forth in detail all the purposes for which the proceeds of the tax lease were to be used. Since the expense reached an amount in excess of 55 zlotys over the revenues, the Prince demanded that this amount be recorded as a debt of the tax lessee against his tax accounts.

In turning to our review of the revenues, it must be pointed out at the outset that the direct taxes were at the top of the list. If we divide the revenues into four categories, we get the following picture:

| Direct Taxes | 5,529 zlotys | 55.1% |

| Indirect Taxes | 3,225 zlotys | 32.1% |

| Loan Proceeds | 1,079 zlotys | 10.8% |

| Minor Revenues | 195 zlotys | 2.0% |

| TOTAL | 100% |

In accordance with the accepted practice at the present time for budgetary policies of public institutions, one may determine that the practice of the Biala Jewish community was advanced from the standpoint of the relative rates of direct and indirect taxes. The question remains, however, whether the allocation of direct taxes was justified in that everyone would pay according to his true ability.

Let us now examine the balance sheet. Placing revenues against expenses we find a deficit of 1,040 zlotys. The situation will be clearer if we would also take into account details of the financial situation for the year 1749/1750. For these two years we find among the documents a writing from the Court which gives one the impression of being a “preliminary balance sheet” which was prepared by the committee on behalf of the Court. In this preliminary account we find the following with respect to the two years:

| Revenues (not itemized): 18,434 zlotys

Expenses |

| For the Priesthood | |

| Royal Tax | 2,712 zlotys |

| Horses, carriage and various materials for the Court | 792 zlotys |

| To cover the deficit caused by exchanging the Prince's money | 1,074 zlotys |

| Lighting for the Court Guard | 86 zlotys |

Thus there is an excess of 5, 852 zlotys. Actually the situation was quite different. The Court was budgeted 2,409 zlotys for two years (792 + 1074 + 86 +83 +74+ half of expenses for gifts –300),

[Page 16]

and as we know from an analysis of the budget for 1748/49, that the Court received 2,609 zlotys and half of the expenditure for gifts –182 zlotys, equaling 2, 791 zlotys. The preliminary balance sheet is, therefore, not accurate, since the Court committee hid a not inconsiderable amount, that was promised to the Prince, and on the other hand, did not deal with the actual expenses of the community. The latter spent 1,467 in 1748/49, 2,934 for two years, not 1,960 (720+ 312 + 312 + 416 + 200) shown in the preliminary balance sheet. The accurate expenditures for the abovementioned two years is actually:

| Revenues | Expenditures | |

| 1748/49 | 10, 028 zlotys | 1, 068 zlotys |

| 1749/50 | 10, 214 zlotys | 8, 940 zlotys |

| Total | 20, 242 zlotys | 20, 008 zlotys |

The excess, therefore is only 234 zlotys (and not 5852 zlotys). But this excess sum exists only on paper: the loan of 1, 079 zlotys from the year 1749 was not repaid. Also the debts stemming from the salaries of the community officers were not paid. Moreover the community took on new debts in 1749: from the priesthood – 350 zlotys; from Shimon the storekeeper – 105 zlotys; from the tailor – 321 zlotys; in total 776 zlotys of new debts.

And here is another interesting fact. In 1749/50, the community had to borrow from the synagogue budget, from the Chevra Kadisha [burial society] and from the Tailors' Society, the sum of 245 zlotys. How then can one speak about an excess? And where was the money to cover the debts of the previous year, 1748/49? Something here is not in order.

The Prince knew, but it was convenient for him to ignore it, so that his income would not be affected. The Jews also knew this: they sighed and moaned, haggled about prices, showed open opposition and went to jail, tried various schemes, but finally , the Prince prevailed and the Jews paid, more than they could afford. The whole (deficit) of one year was covered by a patch, and the hole in the patch was covered by a new patch. Moreover the amounts in these budgets were not the only community expenses. Jews paid membership dues to the Chevra Kadisha and the Tailors' society; there were contributions for the maintenance of the hospital and the home for the aged and homeless; the Jews who lived in the center of town paid a special individual tax to the city and Prince; for taverns there was a special fee to the Court and to the Royal Exchequer; Jewish who worked selling hides and materials for making shoes paid a special fee to the municipal guild of the shoemakers. And there were additional expenses; rebuilding after a fire or an epidemic; for special royal occasions; the Court and the community and the Kingdom in general.

All of this added up to a heavy burden and testifies to the struggle for existence. It was difficult, but the Jews managed, honorably.

E. Events on the Jewish Scene

Life within the Jewish community of Biala did not differ in any way from life in the other Jewish communities in Poland: matters of finance, and trade, and work, raising children and marrying them off, Cheyder and yeshiva, bet–midrash [study hall], quarrels within the community, rabbis and religious functionaries, quarrels with the Prince and the municipality, the sufferings of Exile and the hope for the Messiah–this was the stage upon which the daily life of the Biala community was enacted. In addition, it is important to note three events of special Jewish significance, where the Jews of Biala performed a particular role, and in later years, even a major role.

These three events are connected to the ferment in all the Jewish communities with the appearance of the messianism of Shabbetai Zevi.

In 1666 Shabbetai Zevi converted to Islam; one might hope that thus the tragic events had come to an end. In fact, however, matters took a different turn. His followers did not despair; they saw his conversion as a mysterious way to hasten the redemption, to hasten the coming of the Messiah. During the tens of years following his conversion, prophets and wonder workers appeared in various countries, and to a large extent, also in Poland, who wished to hasten the coming of the Messiah, calling for repentance and faith in the coming redemption. Thus it is no wonder that they found loyal respondents. The belief in Shabbetai Zevi and his mission were revived, and a fierce struggle arose among Jews –for Shabbetai Zvi and against him. One of the leaders in this belief – possibly from Siedlce –– R' Yehuda Hassid, together with another Polish Jew, R' Hayim Malakh, organized a great migration to the Land of Israel. Among the migrants there were enthusiastic followers of Shabbetai Zevi, and other Jews who believed that by ethical lives, repentance and suffering, and their connections to the Land of Israel, they would pave the way for redemption. There were about 120 people when they left Poland and on the way the group grew until it reached 1500. About 500 people died along the way. After a year– long journey, through Moravia, Hungary, Germany, and Italy they came to Jerusalem in the month of Cheshvan [4] 461 (October 1700). Unfortunately, five days after their arrival, their leader, R' Yehuda Hassid, died. Their situation was very bad. Many became depressed and some converted [to Islam] or returned to Exile [i.e. Europe]. Those for whom immigration to the Land of Israel was a question of life, remained – and among them was one man named R' Yosef son of Pesah Bialer. We do not know how many of the immigrants came from Biala. Two are known by these names: one was R' Zalman Bialer who died as soon as he came to Jerusalem and was buried on the same day as R' Yehuda Hassid.[15] The other was the above–mentioned R' Yosef, for whom coming to the Land of Israel was the beginning of a new life, a life of holiness and purity. He became well known among the groups that remained in the Land. He was sent from Jerusalem to Izmir (together with another leader R' Moshe from Siemiatyce) to see how the Sabbateans were doing there; in 1707 we find his signature on a rabbinic document sent from Jerusalem to one of the great scholars in Germany, R' David Oppenheim. In 1729 he was still alive and he was the only hassid known to us who had remained in Jerusalem.[16] In 1702 a group of immigrants came from Italy under the leadership of kabbalist R' Avraham Revigo, who founded a yeshiva here in during the intermediary days of Passover; among the ten men chosen to be the nucleus of the yeshiva there was the aforementioned R' Yosef (along with another five Polish Jews). These ten chosen men were to sit “night and day, praying and crying aloud with broken hearts.

[Page 17]

Immediately after the prayers, clad in holiness and purity in their tallit and tefilin, they choose to study the Zohar, and after that the writings of the Ar”i until the hour of prayer, and after midday they study gemara and poskim and Reshit Hochma until Mincha.”[17] Thus, through the personality of R' Yosef, Biala received great recognition. It may be assumed that R' Yosef was a well– known figure in Jerusalem. As proof, he became related to one of the most respected Sefardic families in the city, Azulai, who took R' Yosef's daughter as a wife for his son. A son was born, Hayim Yosef David, and this Biala grandson, R' Hayim Yosef David Azulai (Hid”a) who was born in Jerusalem in 1724 (and died in 1806 in Livorno, Italy) is still famous until the present as one of the great emissaries who went out from the Land to the lands of the Exile, as a bibliographer and an outstanding scholar.

|

|

| Rabbi Haim Joseph David Azulai– Hida (Grandson of Rabbi Joseph from Biala) |

He authored countless books, among them “Shem Hagedolim” [Names of the Great Men] and a book of memoirs “ Ma'agal Tov” [A good Circuit] about his journeys as an emissary[18] of The Land of Israel in West Europe and North Africa. It is so sad that he never visited Poland; he could have brought us greetings from the city of his mother's birth. And since he was blessed with a sharp eye and a gift of insight he could have given us details about the life there. What the Hid”a missed, his son R Avraham, completed. He was an emissary to Poland, although he never visited Biala. Among the followers of the Ba'al Shem tov there was a tradition that in his later years the Hid”a expressed regret “ that I was in many distant lands but did not visit the countries of the followers of the Besh”t [Ba'al Shem Tov]. In 1756, when he visited the city of Kleve in Germany he found there an aunt, “a sister of my mother, Mrs. Gitli daughter of the king [?] my lord my grandfather the kabbalist the holy man of God, our teacher Rabbi Yosef Bialer may his memory be blessed.”[19] Thus we see that in 1756 the aforementioned R' Yosef was no longer alive. If we may surmise that during his years in Jerusalem R' Yosef communicated with Biala, we may yet discover a letter from him or from Biala to him.

The second event on the Jewish scene in general in which the Jews of Biala participated actively, is in connection with the new storm that swept over the Jewish world as a result of Sabbateanism. In the middle of the eighteenth century the whole Jewish world was wracked by anxiety that the rabbi of Hamburg, Rabbi Jonathan Eybeschuetz, one of the greatest rabbis of his day, was suspected of leaning towards Sabbateanism. The Jewish world was divided into two camps: Those who rejected any accusation and others who tried to prove by means of the amulets that Rabbi Jonathan gave to the sick and new mothers that he was a heretic. If so, he should be persecuted, excommunicated, and dethroned from his high position. At the head of the second camp stood Rabbi Jacob Emden ben Zevi (Yavez) the son of Chacham Zevi Ashkenazi, the former rabbi of Hamburg. Yavez lived in Altona (that was part of the Hamburg congregation) and from there waged a life and death war against Rabbi Jonathan. For both camps it was important to gain the support and loyalty of the higher autonomous institutions of the Jews of Poland–Lithuania, whose spiritual authority was great not only in Poland but in the entire Jewish world. Yavez had two agents in Poland both of whom came from Biala. One was the head of the rabbinic court in Biala (who was also a rabbi in Slavatisch; perhaps it was customary to connect two rabbinic positions), R' Yitschak, the son of the famous rabbi from Eisenstadt, R' Meir (Maharam Esh – Our teacher Rabbi R' Meir Eisenstadt) the brother–in–law of Yavez. The second one was a man from Volhyn who had lived for a time in Biala, R' Baruch the son of R' David, known as R' Baruch Yavan. This R' Baruch was a wealthy Jew who had widespread financial ties with the Polish–Saxon Minister Bruell and with the Minister of Finance in Poland Shedlenicki [Siedlecki?], and thus he had the power to try to get government intervention in a matter that was of great moment to him. He married into Yavez's family, by marrying his son Eliezer to Yavez's daughter Nechama. Yavez wrote about him in his memoirs, “Megilat Sefer” [Scroll of a Book]: “This man fought the wars of God for me; even though he could have made much money in bribes if he had gone along with my opponents, he took not a cent from them and fought for me and even spent some of his money for the honor of God's name, may he be blessed, and his zealousness for the Torah.”[20] The war was not an easy one. The rabbi of Lublin and his father R' Avraham, who had a great deal of influence in the Council of the Four Lands, were on the side of Eybeschuetz and in 1751 achieved the excommunication of Yavez. But R' Baruch was not dismayed: Here is what he wrote to a rabbi from Amsterdam who was one of the brave proponents of the camp of Yavez: “Every day and every hour I have been drawing the attention of the honorable rabbis and parnesim [community leaders] and loyal followers with my words; “Why are you rushing? I did not rest and did not keep quiet, but persisted at the doors of the parnesim and the loyal rabbis.” When he was convinced that he could not succeed from the Jewish side, he turned to the Minister of Finance Shedlenicki and he imprisoned R' Avraham. His followers wanted to bribe him by giving him some hundreds to stay mum. “Not only do I answer only to the One above in these matters, but I have spent the little that God has given me and bestowed upon me.” In short, R'Baruch wrote to Amsterdam: “I thank everyone, I have been steadfast in my position,

[Page 18]

I have fought against them all.”[21] But none of this helped. Eybeschuetz's party was very strong, and the autonomous Polish council (of the Council of the Four Lands) as well as the Lithuanian council (“The Supreme Council of the Province of Lithuania”) expressed their support of his position. In 1751 the Lithuanian Council declared:” We excommunicate and cast out and curse whoever opens his mouth against our teacher and rabbi Yehonatan.”[22] Two years later the Polish Council declared that R'Jonathan was a Jew “within whom is the spirit of God and he is fit to be divinely inspired; he is innocent of wrongdoing and has explained his amulets as grounded in holiness to the learned men of the time: and anyone who doubts him it is as if he doubts the divine presence”[23] –and they ordered all the writings against Eybeschuetz to be burned. For three years, 1751–1753, R' Yitschak and R' Baruch were on guard and they participated in all of the important meetings and tried to influence whomever they could to their side. For them it was a holy war. It was especially difficult for R' Yitschak who did not have the financial resources that R' Baruch had. Here are some of his words: “I must travel to the meeting of the Council of Four Lands in Constantine and may the Holy One Blessed be He reimburse me for my many expenses”[24]: “I battled against all the writings that came into my possession and gave 12 gold pieces and half [ma'ot fashet?]”[25]: “I was there (in Brody) for a month in order to guard the Tree of Life and may the giant in Torah scholarship our teacher Rabbi Baruch Yavan be remembered for supporting me in my battles, and the rabbis said to send a pair of rabbis to the Holy Congregation of Hamburg, and I among the, but the main point is missing from the story: who will cover the expenses? We must give many red hundreds [monetary units] for one hour.”[26] R' Yitschak believed sincerely that he would be able to battle against Eybeschuetz; “and my hand is outstretched for the Council that will be in the Holy Congregation of Constantine on the 12th of Tamuz (1755)[27] For until when will the sword eat and conquer them: wherever there is a desecration there they do not honor the rabbi.”[28] R' Yitschak and R' Baruch were ready to continue their struggle, but meanwhile a new event occurred that was more dangerous than the amulets of R' Jonathan Eybeschuetz.

And here is the third act in the history of Polish Jewry in which the Jews of Biala participated–again via the abovementioned R' Yitschak and R' Baruch. At the end of 1755, a Jew named Jacob Frank [1726–1791] of Podolia, returned to Poland. He had spent a great deal of time in Turkey and there had been in touch with the Sabbatean sect, the Donmeh.[29] He gathered around himself all the supporters of Shabbtai Zevi and although until then Frank had been drawn to Islam, he began to lean toward Christianity. Frank and his sect lived like hedonists, immorally and atheistically. They conceived the idea of converting to Christianity and even accused the Jews of the blood libel, that the Talmud teaches them to use Christian blood for Pesach. The Eybeschuetz–Emden controversy was, with all of its difficulties, an internal Jewish problem. Here there was a matter of great danger to all of the Jews of Poland. In those dark days blood libels appeared quite often, and the testimony of Jews could bring disaster. The leadership of the Jews entered into the midst of the conflict and a bitter struggle ensued. The Lvov Provincial Council placed an excommunication order upon the Frankists. The excommunication order was confirmed by the Council of Four Lands in Constantine. The Bishop of Kamenetz took the side of the Frankists and ordered a public debate between the Jews and the Frankists. The debate ended with the Bishop deciding against the Jews and his decision to burn the volumes of the Talmud (1757). Frank continued with his propaganda and as a prospective convert to Christianity, he gained the support of the king. A new debate was ordered, this time in a central place, in Lvov, in order to prove that the correct version of the Jewish Torah and its messianic belief was Christianity. The Jews were steadfast in this worrisome debate (1759) but the Christian ruler announced that the Frankists were victorious. Only in one detail did the Jews win a partial victory, but this was an important detail: the question of the blood libel remained open until the decision of the Pope. The Jews turned to him and asked for him to intervene and reveal the truth. At this time the Frankists openly trumpeted their conversion to Christianity. However, there was a quarrel between Frank and his Christian supporters on his loyalty to Christianity. He was arrested and imprisoned in the Czestochowa fortress. With the first division of Poland (1772) the Russians freed Frank and he and his followers settled at first in Brno in Moravia, and afterwards in the area of Frankfort on Main, where he died in 1791 at age 91 [sic!, i.e. 65] all the while believing in his messianic mission to redeem the Jewish people.

We are concerned here with the activities of R' Yitschak and R' Baruch in the war against the Frankists. In his book, “Megilat Sefer”, Yavez writes: “ My father–in–law, R' Baruch, should be remembered with favor in this matter, for he stood firm as a pillar of iron before the King of Poland and his officers to abolish their evil plans against the Jews and he offered his life and wealth to retaliate and pursue”.[30] During the early years of the struggle R' Yitschak Denan stood in the forefront. In a letter of R' Baruch to Yavez he writes about the Committee in Constantinov: ” He (R' Yitschak) was here for a time and during the time of the meeting of the Large Committee he held steadfast to his faith like a foundation stone in his work for a mitzva.”[31] R' Baruch on his side emphasized not only the Jewish aspect of the matter but also how it would affect the Christian church: “And we too must root out our feelings towards them and stand before the lord bishops to judge these accursed ones to be burned, because according to their laws, anyone who creates a new faith is doomed to be burned.”[32] His judgement was correct: According to these tactics the struggle would be easier and would be crowned with success. After the Edict of Kamenetz (1757) [the burning of the Talmud], R' Baruch turned to Prime Minister Bruehl, and described to him how the matters had developed –“ I besought him to ask our lord the king to command, in his great mercy, to cut them off as a sect of Shabbetai Zevi, may his name and memory be erased.” Bruehl advised him to present a memorandum to the king so that he should continue acting with the aid of the Ambassador of the Pope (the Nuncio). R' Yitschak wrote the memorandum and sent it to the King, “and I did even more, taking with me people and making supplication to the Nuncio's court.[33] And the hand of God favored me and I donated as a holy contribution one hundred reds for the expenses of this judgement.”[34] It should be noted

[Page 19]

that R' Baruch did not act arbitrarily on his own, but consulted the official representatives of Polish Jewry and reported to them. He hoped that this would be the end of the Frankist sect. He writes: “When our eyes saw the Torah being burned, it was as if we saw our daughter being burned.”[35] At the same time as he acted in Warsaw he also turned to the congregation in Amsterdam to work with the community in Rome at the court of the Pope.

We have seen above how the matters developed. R' Baruch continued to involve himself in the matter. When Frank was imprisoned in the fortress of Czestochowa he managed to make connections with Moscow and [St.] Petersburg, hinting that he would be willing to accept the Russian Orthodox faith. Again R' Baruch appeared on the scene, “he actually laid aside all his business affairs and worked for the sake of heaven, and he was able to reveal the true face of Frank and his helpers and these evildoers were disappointed.”[36]

In conclusion, we can state that these two Biala Jews represented the Jewish position with great honor; it is not their fault that they were unable to do more.[37] And again we say sorrowfully that we have no additional data about R' Baruch and R' Yitschak; it would be interesting to know if and how these two important leaders acted in the community of Biala itself.

F. The Community and the Outside World

The Jews of Biala also shared in the history of the many persecutions and cruel edicts, which befell the Jews of Poland. There are not many data on what occurred to the Biala community during the 1648–1649 massacres by the troops of Chmielnicki, but from subtle hints we can assume that it was also involved in the tragic events. The main chronicler of the edicts, Rabbi Natan Hannover, did not write much about the fate of the Lithuanian communities. He just mentioned in general that “some of the people of the Holy Congregation of Slutsk and the Holy Congregation of Minsk and the Holy Congregation of Brisk of Lithuania [Brest Litovsk] escaped to Greater Poland and some to Danzig on the water, on the River Vaisel [Vistula?] – but the poor people remained in Brisk and Pinsk and some hundreds of souls were martyred.”[38] In the introduction to the Slihot prayers that the great teacher Rabbi Shabtai Kohen (author of the commentary on the Shulhan Arukh “Siftei Kohen” –Shakh), who was himself a victim of the edicts against the Jews of Lithuania during the uprisings of 1648–49, we read: “They slaughtered many in the Holy Congregation of Vlodovi. Also in the Holy Congregation of Brisk and the Holy Congregation of Pinsk and all the districts and nearby towns, there was no place where corpses of men and women were not heaped upon each other.”[39] In another chronicle (“The Place of Suffering” of Rabbi Shmuel Fayvish son of Rabbi Natan Faitil) there is list of the edicts which were enacted on various congregations: “In the state called Podleshi” [Podlask?]; he mentions Mezeritch a number of times (Greater Mezeritch, Lesser Mezeritch, and Great Mezeritch). There is no doubt that one of these was close to Biala.[40] Biala is not mentioned but without doubt its fate was like that of the other communities near Brisk.

We must pause here to mention two personal tragedies among the residents of Biala that occurred in the 18th century. In the year 1710 a Jew from Biala was condemned to death on the basis of a blood libel. Ten years later there was an incident which is not well based in history, but contains a grain of historic fact. The incident relates to the famous son of the rabbi of Lvov, Rabbi Hirsh the son of Rabbi Naftali Hertz, whom Biala was privileged to receive as rabbi and head of the yeshiva. In the sources he was called Rabbi Tsevi Hirshli Halberstadter (for the name of the congregation of Halberstadt where he served after he left Biala). It seems that he received the name Biala [sic!] as a family name. Rabbi Tsevi Hirsh had a beautiful daughter whom the landlord desired. The rabbi and his wife sought to save their daughter from the landlord and hastily married her off to a student of the rabbi's, Rabbi Moshe of Brisk. During the wedding the landowner suddenly appeared and tried to snatch the bride by force. All the guests were frightened to death. But the young bridegroom kept his nerve and with one blow felled the landowner and escaped with his bride. The landowner was enraged because of the insult and failure and he imprisoned the rabbi and his family. The rabbi was doomed to die. To his good fortune, the Jewish shtadlan [intermediary] and wealthy businessman, Yissachar Ber Lehmann from Halberstadt, intervened. He had great influence in royal circles, and the rabbi and his family were freed. It was difficulty for him to remain in Biala, especially after the news arrived that three days after her escape his daughter died. Therefore Rabbi Tsevi Hirsh accepted the offer from Yissachar Ber to be appointed rabbi of Halberstadt. He took his son–in–law, Rabbi Moshe, with him, who was later a rabbi in Pressburg. It is told about Rabbi Tsevi Hirsh's service as a rabbi in Biala: “When he was in Biala all the people loved him and honored him greatly. They knew and understood that their rabbi was one of the great scholars of the generation and one of the great leaders of the Diaspora. His modesty and the charity which he gave to the poor, and the respect which he showed every one of his congregants brought honor to all. No one interrupted him in his devotion to the study of the Torah when he spent his time within the confines of Jewish law.”[41] Rabbi Moshe directed a large yeshiva in Halberstadt. He was distinguished in his scholarship and was given the honorary title of “Harif” [sharp–witted]. He developed many activities as spiritual leader. He died in 1748. His rabbinic letters were published in “Ateret Zevi” and “Kos Yeshuot”. Rabbi Maimon described him in his book,”Sarei Ha–Me'ah” as “ a prince of the Torah and a paragon of holiness and purity; a wonderful personality, endearing, with unique influence and generosity of spirit.”[42]

In 1751 an item was published in a German newspaper. Shmuel ben Yitschak, who had been the chief treasurer and manager of the leases for the income of the court, whom we have mentioned in the past, was involved in a dispute between the landowner and the finance manager of the King of Prussia with his Jewish provisioner, Efrayim. It seems that this dispute had a bad effect on the royal treasury, and since a Jew was involved, the landowner revenged himself on the Jews of Slutsk and Biala and put 92 of them in jail. In 1751 the dispute was settled and the economic ties between the King of Prussia and Prince Radziwill of Biala were renewed and the prisoners were released.

[Page 20]

He granted the released prisoners gifts and showed special beneficence to the family of Shmuel, who had died in the meantime. “With abundant goods for all their lives.” The original item appeared in a Danzig newspaper. From this we can infer that the dispute arose in connection with the sale of produce from the landholdings of the Radziwills in the maritime markets of the city.

Another piece of information from the seventeen sixties reached us by chance. It has a connection to the great rabbi. In 1744 Rabbi Meir ben Yitschak, known by the name Maharam Esh (our teacher Rabbi Meir Eizenstadt) died in Eisenstadt (Hungary). His son, Rabbi Yitschak son of Rabbi Meir was the rabbi of Biala in the seventeen fifties, and in the previous chapter we wrote at length about his activity by the side of Yavez in the battle against the Sabbateans. In 1766 his brother, Rabbi Yehuda, also a resident of Biala, published their father's book “Or Ha–Ganuz”, novellae on the tractate of Ketuvot and the laws of gentile wine, and in the introduction he writes: “ Our Holy Congregation of Biala, in contrast to [what happened in the city] at the time the king was chosen in Poland in the year 524 [1664] we drank the poisoned wine: That same year, on the first and second days of the month of Tammuz, the enemies came to our community with great noise and clamor and gave permission [to their men] to do whatever they pleased to the Jews, who were called in German Flindrin [?]. They were given permission to attack for three hours, and they plundered for a full day, Heaven forfend! And who can tell at length about the great troubles, especially what they did in the Great Synagogue and in the House of Study in our community. They plundered and stole from me all my property and left me and my wife and my son, may they live, all our nice clothes and we were left stark naked. Nevertheless I thanked the Lord, may He be blessed, that no one was murdered. May the Holy Congregation of Brisk be remembered for good for the leaders of the community announced that when the robbers left to go to Brisk, they passed an edict that whoever bought any of the plunder from our community had to return it to us without any profit. This was of great assistance to our community. Many manuscripts of my father and teacher the rabbi, may his memory be for a blessing, were lost except for his book on the Torah, “Ketonet Or” and “Novellae on the laws of gentile wine and novellae on the tractate Ketuvot.”

From this introduction, we learn that in 1764, in the days of confusion in connection with the choosing of the last king of Poland, Stanislaw August Poniatowsky, Biala suffered a pogrom which ended without any deaths. Rabbi Yehuda suffered a great deal, and his greatest pain was the loss of his father's books that had been stolen. Two years after the pogrom he travelled throughout Poland, Austria and Germany to collect money to publish the manuscripts which had remained. He gave the manuscript of “Ketonot Or” to his sister's son who was a rabbi in Zablodova, who published it. He himself published the book “Or Ha– Ganuz”. From his story we learn of the noble behavior of the community of Brisk, which helped Biala recover after the pogrom.

G. The Period of Transition from the Kingdom of Poland to Congress Poland (1795–1815)

In 1795 the Kingdom of Poland ceased to exist. In that year there began the third division of Poland (after the first two divisions: 1772, 1793). The Great Powers–Austria, Prussia, and Russia––– annexed additional Polish regions. The districts of Lublin and Siedlce, in which the town of Biala was located, became part of Austria with a new name “Western Galicia”. In 1809 there was another change as a result of Napoleon's victory over Austria. Western Galicia (including Biala) was taken from Austria and added to the “Principality of Warsaw” created by Napoleon for the King of Saxony (in 1807). For fourteen years the Jews of Biala were Galicians. In 1815 the Principality of Warsaw became a part of Congress Poland connected to Russia –according to the decision of the Congress of Vienna. This transitional period created changes in the constitution and the juridical and economic situation. We should add that this entire period was full of battles, and clearly this fact impacted on the general situation of the town and the community. There was another change as well. In 1813 the Prince Dominik Radziwill died after participating in the Battle of Leipzig, and Biala passed to hands of his son–in–law, the Russian Prince Wittgenstein. Biala became the subdistrict capital and the academy became a royal gymnazie. In the ledger of the “Chevra Kadisha” [Burial Society] we find a list which hints at the change from 1809. Until then the fees were paid with Austrian money but from then on would be paid with the new monetary units “because of the changing times.” In the days of the Warsaw Principality, Biala continued serving as a subdistrict capital. In the chronical of those years there were three important events: In 1812 there was the Sejm on the subject of joining the Napoleonic trek to Moscow. During that same year there was a Russian–Saxon battle in the Biala area, and it cost the town large sums (payment of tribute). In the fall of 1815 the Russian Tsar Alexander the First passed through Biala on his way to the Congress of Vienna, which was convened to end the rule of Napoleon. At the time of his visit he received a delegation from the Polish Senate.

As for the Jews, during Austrian domination they were required to pay two new taxes: “Kosher tax” which increased the price of meat greatly, and candle tax which had to be paid by every family. Thus the Austrian ruler became the guardian of the Jewish way of life as related to the lighting of Sabbath candles, memorial candles, etc. There was also an increase in the old Polish poll tax (now called Toleranz Steuer, that is, a tax for the right to live and work). There was also a payment for conducting weddings. Life did not therefore become easier. On the other hand, there was an improvement in general conditions because of the new impact upon commerce and industry in providing for the army. In general, Austrian policies toward the Jews included additional burdens: requirements for army service, school attendance, and taking a family name, edicts to outlaw the traditional Jewish dress, and selling liquor in the villages. We do not know how these laws were applied in Biala.

In the time of the Austrian rule there was a change in the relationship between the Jewish community and the town administration. In 1800 the two sides reached a mutual understanding, and a charter was drawn up which, if it had been observed, would have fundamentally improved the lot of the Jews. According to the charter, the Jews would participate in electing the administration;

[Page 21]