|

re Hebraizing the government school number 4

|

|

[Page 495]

[Page 496]

[Page 497]

Translated by Ala Gamulka

Edited by Karen Leon

I will begin with an apology as is the custom in the world, to show the reader all of the sources that the author used to complete the article. However, the writers of various all-encompassing articles about the history of the Hebrew School in Bessarabia (Avraham Levinson, Shlomo Hillels and Prof. Zvi Shrafshtein) based their studies on articles written by the author of this entry, the former secretary of “Tarbut.” These articles appeared in various forms of the press so the author does not feel obligated to show proof. Also, much of what is written here comes from the memories of those days when the author was deeply involved, for twenty years, in the events concerning the Hebrew school. Fortunately everything was preserved and remains vivid in his mind. The author also used other print sources to explain the history more clearly.

Before the RevolutionUp until the February 1917 revolution, many towns and villages in Bessarabia had, along with the “corrected cheders”, special schools for Jewish children where Russian was the language of instruction. (In the larger cities Jewish children were also accepted into the government-run schools.) These were largely four-year elementary schools that followed government guidelines and were under government supervision. I.C.A. [Jewish Colonization Association] founded some of these schools, for example in the agricultural settlements of Dombrovani, Vertuzhani, Lublin, Markulesht, etc. They were later transferred to the Association of Disseminators of Education in Petersburg. The schools were also part of an educational network in Bessarabia. Some were Talmud Torah schools, which meant that religious studies were taught in addition to the required curriculum. Their budgets came from a special fund of income that was generated through the candle tax, (a tax on the Jewish population for lighting Shabbat candles), and from the meat tax, known as Korobka[1] in Russian.

[Page 498]

The income was often greater than the need in larger cities, so it was used by the local authorities to build fancy high schools. These schools were meant for Jewish children who paid fees. However, in many cases, these schools served the general public and were often nests of anti-semitism among the teachers.

Fights about language and take over by the Yiddishists

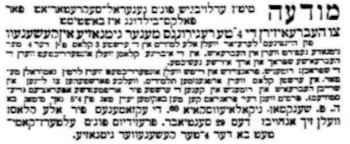

The February Revolution broke the grip of Russification that was forced on different nations. The Jewish minority was energized to create their own educational institutions in its own language. This began with the first teachers' committee which also included a few business people. It met in Kishinev in August 1917, with the support of the new authorities, and was formed after the revolution. After a difficult and bitter battle between the two factions, the Yiddishist and the Hebraists, over the language of instruction, the Yiddishists gained the upper hand. The decision, passed with a two-thirds majority, states[2]:

Since the language in school should be in the mother-tongue of the children, the committee has decided that even in the Jewish school in the free state, the mother-tongue language of Yiddish must be used.The teaching of Hebrew language and literature, an essential part of Jewish culture, must occupy an honorable place in the Jewish school.

The reason the Yiddish teachers took over can be explained by the fact that most of the teachers in the earlier schools had taught in Russian, and were not supporters of the national movement. On the other hand, many of the teachers who loved Hebrew, were not at first, drawn to teach in these new schools. They preferred to teach Torah in Hebrew in small groups or through private lessons. The new Hebrew school, Tarbut, was in its infancy, and existed only at the high school level, and its teachers were not yet involved in promoting it. This is how the Yiddishist camp came to be in charge of Jewish education. This was the group that decided the national fate of the 37 government elementary schools and the two public high schools existing at that time in Bessarabia.

[Page 499]

There were 7,000 students in those schools, out of 33,000 in that age group, and Yiddish was the language of instruction.

In addition to the decision about the language of instruction there was also a determination to establish a special seminary for training teachers. In the meantime, short summer courses were available for this purpose. A Jewish School Committee was also formed. This committee was eventually given official government status as a special department within the Education Ministry. It was a regional organization left over from the Bessarabian autonomy and it supervised the curriculum. There were 12 members: 8 were Yiddishists, which included 6 Bundists, and 4 were from the Hebrew camp.

It did not take long for Bessarabia to be annexed by Romania. At first, the new authorities looked favorably upon the schools for national minorities since they helped to remove the Russian language. At that time, on August 14, 1918, the Romanian government issued a proclamation that recognized the rights of the Jewish minority to educate its children in government schools, in their own language. On this basis, the 37 schools were again recognized. The Reali School in Bender, with a large majority of Jewish students, introduced Hebrew as an official teaching language. Yiddish was the language of the 4th Gymnasia in Kishinev.[3]

The second teachers' committee met in August 1918, causing a rift among the Yiddishists and the Hebraists. The Hebraists demanded that the committee again discuss the issue of the language of instruction but their request was not accepted. The Hebraists left the committee and did not take part again until July 1921 when the third committee met. In the meantime, the Yiddishists were drunk with power and continued to serve on the committee alone.

The education committee continued to provide short, summer courses for Yiddish teachers. These courses began in the summer of 1917 because most of the teachers, especially the women, had become completely assimilated. They were educated in Russian and their Yiddish was quite poor. For them, Yiddish was a street language, not a language of instruction. In addition, their knowledge of Jewish history was inadequate.

[Page 500]

The fact that they joined the Yiddish camp, and preferred Yiddish to Hebrew was not because of belief, but because they chose the lesser of two evils. They could not teach in Romanian, so they stayed with Yiddish. Their loyalty to Yiddish ended as soon as the authorities pressured them. This is what I. Bart, a member of the central committee of the “Culture League”[4] said at a lecture during the third annual Culture Committee about the condition of the Yiddish schools in Bessarabia: “the government's policy of Romanization was not opposed by the school. In the past, the clerks did not understand that the Yiddish language was the best way to educate Jewish children. The assimilationist teachers were enemies of Yiddish and of new pedagogical methods. It was a different situation in the public schools which had a higher standard.”[5]

It must be added that the Jewish public did not believe in the Yiddish schools, and so they were abolished after one or two years.

The decline of the Yiddish school and the rise of the Hebrew school

It did not take long for everyone to realize that the Yiddish school could not succeed in Bessarabia. The Jews of Bessarabia, who were mostly lovers of Jewish literature and nationalists, were not prepared to send their children to a school with a weak national component. The school quickly became important only to a few teachers.

Parents wanted a new, modern school that would replace the “old cheder” and the “corrected cheder.” It would serve as a stronghold for Hebrew literature and would educate its students in a national atmosphere and in a language closer to their hearts. The Tarbut Hebrew school appealed to them. The Jewish public was keen to establish a Tarbut school in every town. They wanted teachers who would devote themselves to the school's success so it would become a beautiful center of culture. For many regions it was a step towards the rejuvenation of national aspirations, soon to become true.

In the meantime, the battle between the two groups grew. On the one hand, were

[Page 501]

the Yiddishists, who were at first in control of the committee for Jewish education. They changed all the government schools to Yiddish language. There were about a dozen schools supported by public funds. On the other hand was Tarbut, which began to build the Hebrew school. It must be noted that the struggle was internal only. Both Tarbut and the Central School bureau cooperated outwardly, whether within the committee or not.

The Jewish high schools had existed even before the revolution. They began to change their character and developed a clear Hebrew nationalist outlook. Zvi Schwartzman established Hebrew studies at the high school in Bendery in 1912. The school earned a strong reputation under his leadership. It was, I believe, the only school of its kind in southern Russia. Secular subjects were also taught in Hebrew. As there was a lack of proper textbooks the teachers translated whatever was needed, and these translations later became the basis for actual printed textbooks.

This is what happened in Beltz: In “Ha'am” (The Nation) of 30 June 1917 we find an advertisement by the Parents Committee (signed by the initiator of the project, A. Grafter), written in Russian, seeking special Hebrew language and literature teachers for the high schools. At first, the high schools opened as dual language institutions - Hebrew in lower grades and Russian in the upper ones. The principal was a local non-Jew. The first teachers of Hebrew, and secular subjects taught in Hebrew, were: P. Lagerman, Yakov Reidel and Shmuel-Nachum Kahanovsky, who had moved from Warsaw. Three years later the principal was Boris Solomonovitz Dubinsky. He was a member of a veteran Zionist family from Kishinev. He had previously been the principal of the boys' high school in Kishinev, “Ozrey Hamischar”.

A whole network of Tarbut high schools was founded in 1919-1920. In Akkerman, the principal was Yakov Berger; in Leonova, the principal was D. Chazak-Auerbach, later followed by Raphael Katz; in Markuleshty, the principal was Yeshayahu Tomarkin, and in Soroka, Eliyahu Maytus, the poet, was principal. Even the boys' high school in Kishinev, founded by Kulik, became part of the Ozrey Hamischar network under B.S. Dubinsky, and it gradually became more Hebraic in character. Agudat Israel established the well-known Magen David high school in 1921, whose affiliation was religious-Nationalist. Magen David was presided over by the chief rabbi of Bessarabia, Yehuda-Leib Tzirelson, and directed by Nachum Livon.

[Page 502]

In the same year, a high school was set up in Securany, under the direction of Shmuel Gorin. Most subjects were taught in Hebrew during its first two years. Beginning in 1923, the principal did not fulfill his mission, and bowed to the pressure of Romanization. He was dismissed from his job, but the school did not return to its earlier situation. Yet, Hebrew studies still held a respectable place in the school and were taught by the excellent teachers, Zev Igrat, Hillel Dobrev, Kalman Spector, Nachman Polichtchuk and Mordechai Goldberg. There were also several Hebrew middle schools in Teleneshty, Tatarbunar, Tarutino, Falesht and Pirlitz. However, these institutions could not withstand the pressure to switch to Romanian, and, by 1925, the schools were closed. The exception was in Tarutino, where the school reopened in 1926. Romanian became the language of instruction for secular subjects there, and the principal was G. Rosenthal.

Elementary schools were founded throughout Bessarabia. Parents paid tuition and the community helped with donations. These schools were packed with little space to spare. It was not possible to open new Hebrew schools since there were not enough teachers. The Yiddish schools in the smaller towns were almost empty. Most of the students were girls as the parents of boys preferred to send their sons to the Hebrew schools. The situation became so bad that the Yiddish teachers went from house to house urging parents to at least send their daughters to the Yiddish schools. Tuition was free! In the Hebrew school, however, parents had to pay high fees, except for those who had no means.

Even among the parents of the government high school in Kishinev (number 4), there was an understanding that Hebrew should be the language of instruction. Before that, in 1918-1919, Yiddish was used.

|

|

re Hebraizing the government school number 4 |

[Page 503]

However, the Education Committee, whose members were mostly dedicated Yiddishists at that time, refused to accept the parents' demand. Finally, after the second parents' meeting, when results of a poll conducted by the directorate was announced, the committee was forced to back down. The directorate approved the parents' decision. The following teachers were appointed at this time: Israel Berman and Pinchas Miastokovski for Hebrew studies and Gleichman for Mathematics.[6]

The results of the poll conducted by the education directorate among the students' parents in May1920, clearly indicated their preferred language of instruction. Of the 103 questioned, 92 (96%) voted for Hebrew and only 2 (1.9%) for Yiddish. In addition, Koliav, the high school principal, addressed this matter with Rabbi Tzirelson.[7] This is the rabbi's reply:

After we lost our homeland, we were forced to wander through many countries. We came to have two national languages: Hebrew - despite 1852 years of exile, still belongs to our land and to our holy fathers, prophets, and heroes, and Yiddish, which grew out of our secular life in so many lands. The difference between the two languages is that Hebrew is natural while Yiddish is artificial. It is like the difference between truth and falsehood. Therefore, if the parents demand the truth for their children, it is our pleasant duty to fulfill their request.[8]

The fate of the gymnasia in Bendery was quite different. According to an article in “Der Yid” of Kishinev, dated 31 August 1920, the teachers refused to swear an oath to the new regime. The local authorities changed the school's status to that of a private school without any public rights. This caused a sharp decrease in the number of students. It also encouraged the assimilated aristocracy in town to push for the school to become a Russian language one. This effort failed, but, in the meantime, the Jewish community lost an important educational institution.

Even after the Cultural Committee in Beltz announced with great joy, that Yiddish is the national language of the Jewish people there was no change in the status of the

[Page 504]

Hebrew school. The Yiddish school did not improve and its decline continued. This was all due to the relationship between Yiddish and the population.[9]

Finally, the Yiddishists saw that the parents were not happy with the government Yiddish school and preferred the Hebrew one, despite the financial toll. They became less enthusiastic. After a lengthy discussion between the two groups, they agreed that the schools had to reflect the wishes of the parents, which meant Hebrew. This could not be imposed from above. They also reached an agreement on the composition of the education committee. The details of the agreement became known through the decisions of the third teachers' conference held on 5-9 July 1921 in Kishinev. The original decisions are cited in the appendix (written in poor Hebrew, the document is in bad condition). It shows the steps taken for the decision. No one imagined, at the time, that this agreement would be cancelled a year later. Nothing would remain of this national educational effort.

In the 1921/22 academic year, the education committee broadened its activities by organizing preparatory courses for teachers and a special office to supervise the schools. This office operated under the authority of the district directorate for education and culture. The instructors were chosen on the basis of their knowledge of Hebrew and Yiddish. Assignments for these teachers were based on district, not the type of school. The teacher, I. Sherman from Orgeyev, oversaw Yiddish and Shlomo Hillels supervised Hebrew.

Despite the restrictions on rights, declared, from time to time, by the Ministry of Education, those in charge of Hebrew teaching saw good progress and real achievements.[10]

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

Right to left top row: Dr. Meir Avner[a], Dr. Max Diamant[b], attorney Mishu Veissman[c] (Amir) Second row: Dr. Shmuel Zinger[a]Attorney Michael Landau, Dr. Ernst Marton Third row: Dr. Yosef Fisher, Dr. Theodore Fisher, Dr Manfred Reiner[b] |

|||||||

|

|

|

|||||

Right to left: Natan Lerner[c], Dr. Yakov Pistiner[b], Horaya Karp[a] |

|||||||

[Page 505]

The main difficulties were the lack of professional teachers and textbooks, but these problems seemed to be temporary, and possible to overcome with some effort.

Soon, Tarbut formed a special instructional and pedagogical unit. Yakov Wasserman and David Ravlasky, leading educators from Odessa joined this unit. They traveled throughout Bessarabia and in addition to their pedagogical advice, they helped to expand the base of the Hebrew School system. The Yiddishists had not been successful in this regard in smaller towns. They managed it only in Kishinev where there were two craft schools for girls (one founded by Dr. Bernstein-Cohen in the previous century) and one elementary school. At that time, the Hebrew school did not receive financial aid from the authorities, unlike the Yiddish schools. The Yiddish schools had replaced the Russian schools and were therefore able to receive funds from the Romanian government.

Despite all this, the Yiddish group still had to struggle to continue to maintain the existing schools, never mind even dreaming of setting up new ones. They were not successful. As mentioned previously, these schools declined and lost most of their students. The few remaining students were mostly girls.

To understand the real situation in the two schools, we can rely on memoirs by the Hebrew-Yiddish author, Shlomo Hillels. At that time, he was a pedagogical advisor for the Education Committee which served both camps. Since Hillels was known to have had a special warm affection for the Yiddish language, it seems his words are authentic. The following are excerpts from his article “Survey on the Development of Hebrew Education in Bessarabia”, published in volumes A and B of “Paths of Education”, New York (December 1942-March 1943).

The first village I visited was Calarash, near Kishinev. There was a Yiddish school there, almost the only one. There was a group of businesspeople who were interested in it and helped in its development. The teachers were, more or less, experts, and devoted to their profession.

The school found an original way to ensure the continuance of both the kindergarten and the elementary school. Since the village was located at the southern tip of Bessarabia, at the intersection of the Prut and Danube Rivers, a large trade in crops had developed there. The town was popularly called the Hamburg of Bessarabia. Huge freight ships carried wheat on the Danube and on its tributaries, to the Black Sea. Yitzhak Agent, the head of the local community, and a native of Braylia, was one of the first Zionists in old Romania. In an unofficial capacity, he instituted an inner tax of 10 Lei for every wagon of wheat brought to the port, used to benefit the school. This is how the school was able to exist without burdening the parents.

[Page 506]

At the meeting I had with them, they spoke of the urgent need to broaden the scope of the Hebrew studies. This was not the case in other villages and towns I visited. I was surprised to see the abject poverty of the Culture League schools, and by how discouraged the teachers were. It was late autumn. Mud reached our knees, and the cold was bone breaking. The government decreased their budget and there was not enough wood to heat the school buildings. The rooms were not thoroughly cleaned. They were cold, moldy, and dirty. The local population was indifferent towards the school and did not rush to enroll their children. Those who did register were from poor families. They were not properly dressed and shod. They were not ready to attend school on cold and muddy days. The principal of the school was honest with me and spoke of his bitter fate. He complained that the parents did not respect the school and did not send their sons there. They felt that if they were only taught “simple Torah” and songs like “On the upper river”, etc., to learn that two times two equals four, it was not worth sending their children to the school for 3-4 years. They could learn all that at home.

The principal complained that out of 45 registered students, only 12, on average, attended on a daily basis. More students came on sunnier days. Our school will be closed, and the students will be sent to attend a Moldovan school.

In most of these schools I found that the teachers were mostly young women who had graduated from public high schools when the Tzar was still alive. They had no knowledge of Yiddish literature or our history. They could not even write in Yiddish. They learned a simple spoken Yiddish at home. It was quite limited. Their knowledge was based on summer courses in Kishinev which lasted only a few weeks. What could these teachers give to their students? That is why the parents, and the students had a poor attitude towards the school and its curriculum. These poor teachers invited pity. They felt inferior to the Romanian teachers, and this depressed them. In one village, even before I reached the school building, I already heard the noise of the students and the yelling of the teachers. When I went inside, I saw the poor teacher running around from room to room saying: Quiet, murderers! Quiet scoundrels! She taught three grades at once in three different rooms. When she taught one class, she did not know what work to assign to the other two.

In one village, I found a young woman who had completed her studies of history by reading a Yiddish book that began with Genesis. Every chapter had questions for the students. She, too, was embarrassed to learn who I was. From the way she questioned the students, and hearing their replies, I realized that the teacher had simply memorized the questions and answers from the book. The teacher, like the students, did not understand the content.

[Page 507]

I tried to reword some questions, but that just confused the teacher as well as the students. Later when we spoke privately, she admitted her lack of knowledge. She had never studied the history of her own people or the basics of the Yiddish language. It was only in summer school that she first heard the names of Mendele Mocher Sforim, Perez and Shalom Aleichem. They, of course, had created wonderful works of literature.

In Russian high school, I learned only about the Russian people, whom I loved, and also general subjects. I always read the rich and broad Russian literature. How was I supposed to know our own history and literature? I learned a little and would like to know more. I do not know if there are textbooks in Yiddish or how to find them, or if there is anyone who could get them for me.

The situation in the Tarbut school, where there were proper teachers, was far better. The curriculum and textbooks were appropriate, and the purpose was clear. The classes were full. The atmosphere in the school was clean and warm. There was also a group of people who cared for the school and supported its existence and comfort.

If the Culture League schools stirred pity and the Tarbut elementary schools brought satisfaction and consolation, I found that the Hebrew high school of Tarbut was blossoming. This fact brought great happiness. The parents and businesspeople, mainly middle class, and good Jews, showed an understanding, proper attention, and commitment to this educational institution. They did their utmost to help it develop and grow. The principals and most of the teachers were highly educated and were qualified to teach the general and Hebrew studies. They were wholeheartedly committed to the spiritual tenets of our people and to the revival movement. In Bendery I found high schools that were taught exclusively in Hebrew. Schwartzman was the director of this school that had a profound influence on the youth. The high school in Beltz was directed by attorney Dubinsky, who was an energetic, active man. A board of directors consisting of the best Zionists in town, helped him to carry out his goal. In Soroca, a lovable young man by the name of Neiditz ran the school[i]. Later, the poet Eliyahu Meitus was appointed principal. Even in the small settlement of Markuleshty, I found the Hebrew high school of I.C.A. under the direction of a young Zionist correspondent from Czernowicz, totally dedicated to Zionism and Hebrew culture. There were many more. In the past few years, I found many graduates of these schools, men and women, among the pioneers. These people were the best, and loyal to our people. They work in all areas of the new life in our country. They are creative, builders, workers, and defenders of their land with their bodies. They give their all for the land, where they have created a whole group of young poets and authors and other cultural contributors.

[Page 508]

Even here, in the United States, I met many graduates of these educational institutions. They teach in Hebrew schools and are dedicated to our language, our literature and our spirituality. This is a sign that the Tarbut institutions in Bessarabia and its teachers sowed the seeds in the hearts of their many young students. It was a good and healthy seed that grew and brought forth excellent fruit.

Publishing textbooks

Tarbut was organized as a central institution with legal standing in early 1920. It had 30 branches in smaller towns. Among its founders were: Eliyahu Ortenberg, Ben Zion Baltzan, Shlomo Berliand, Israel Berman, Asher-Zelig Shokhetman (Al-Yagon), and Yitzhak Shreibman (Shari). Tarbut identified several basic issues in the normal development of a school and insisted on immediate solutions. There was a lack of suitable textbooks, especially for secular studies, and a need for teacher training in these subjects. For this purpose a special pedagogic conference was held on 2 and 3 May 1920. Twenty-five teachers from the larger cities took part, and they worked on a plan to tackle the issues. Zvi Schwartzman of Bendery led the conference. The secretaries chosen were Yitzhak Schwartz of Kishinev, and I. Reidel from Beltz. Several teachers began to write the first new textbooks, based on a Hebrew synopsis, in Hebrew, of what had been taught up to that point. A special educational committee was named to supervise this work. It was headed by the well-known pedagogue Yitzhak Reznikov with Haim Borodiansky (Bar-Dayan) as the secretary. The textbooks were later published by publishers from Kishinev[11] and Beltz)[12].

[Page 509]

Teacher training

A. Advanced study for teachers in Kishinev

As an interesting fact, at the conference mentioned above, it was suggested that they contact the National Zionist movement to ask for funds for advanced study in summer school. The teacher, and well-known Yiddishist, Sheftel Veisman, opposed this. He demanded that Tarbut must remain a non-political entity whose only purpose was education. Those who made the recommendation reminded Weisman of the purpose of Tarbut, as defined in the 7th conference of the Russian Zionists in Petrograd (6 June 1917):

The Seventh Zionist Conference declares that education and culture are among the important aims of the Zionist Organization. This work must be carried out by a special branch. It must be under the authority of the Zionist Organization, but be administratively independent. The Conference has decided that this branch is “Tarbut”[13]

The Conference did not, of course, accept Weisman's distorted proposal. As planned, the advanced studies program opened on July 14 in Kishinev with 42 participants. Among the teachers were the well-known pedagogues and lecturers: Orlov, Shmuel Gorin, Jurini, Israel Weinstein, Shepsl Weisman, Naftali Zigelboim, Moshe Fustan, Yitzhak Reznikov, Yitzhak Schwartz, and Zvi Schwartzman.

[Page 510]

Tarbut did not succeed in the following years despite many efforts to continue these special teacher training sessions. There were some temporary seminaries that were organized during summer programs.

B. The seminary in Iasi

During the winter of 1921, the Zionist Federation in Riga tried to set up a teachers seminary in Lasi. They invited Dr. Efraim Porat and the poet Eliyahu Meitus to serve as directors. A few dozen students were registered, most of them young people from Bessarabia[14] who wanted to dedicate themselves to education. However, legal problems forced the seminary to close in the middle of the second year. Many of the 60 students continued in the profession. Prominent among them were Dr. Sh. Z. Itzkovitz-Yitzhaki (Belgrade), Betzalel Guzman (Calarash), Efraim Davidson (Dombrovani), Israel Wertheim (Bendery), Yeshayahu Khazin (Calarash), Dr. Yokhanan Kapilvatzky (Capreshti), and others.

C. Courses for kindergarten and other teachers in Czernowicz

A similar program to the one in Lasi was also planned in Czernowicz by the Hebrew Language Organization. In 1920 they offered courses for kindergarten teachers along with Hebrew classes. However, as Dr. DE. Kimelfeld, an important Hebrew educator in Czernowicz, wrote in his article entitled “The Hebrew movement and the educational institutions in Bukovina and Transylvania”[15]: “the lack of tradition and specific curriculum, the lack of appropriate teachers, and mainly the short length of study, as the first session lasted only about 6 months, meant that the first kindergarten teachers were not properly prepared either pedagogically or in their knowledge of Hebrew.”

The author did not provide facts about the fate of these courses in the following years, such as their frequency or number of participants. Instead, he jumped to the year 1934 when he wrote that “by improving the curriculum and establishing serious control it will be possible for this institute to succeed in the future.” There are some added details in the Yizkor Book of the Jews of Bukovina[16], but they are incomplete.

[Page 511]

We will now continue to discuss the courses for Hebrew teachers as described by the above-mentioned Dr. Kimelfeld[17]:

In October 1926, courses for Hebrew teachers were organized under the leadership of the Chief rabbi, Dr. Yosef (Avraham) Mark and Dr. B. (Benoit) Gotlieb. It quickly became clear that there was a great need for such an institute. Young men and women streamed to Czernowicz from all parts of Bessarabia hoping to obtain teaching positions in Hebrew schools there. However, the new institute did not make an impact in Bukovina. The organizers received little public support, and no one looked after the students. Many students went hungry and lived in unhygienic places. Only a few found work in factories to sustain themselves. Had the Jewish public had shown more interest, the institute would have become a blessing for the entire Hebrew movement.

It should be noted that it was not only the Jews of Bessarabia who were involved in founding new Hebrew schools. The young people who had been educated in such schools saw their future in the continuation of this tradition. Wherever they found an opportunity, whether in Kishinev, in Lasi in Moldova, or in Czernowicz in Bukovina, they devoted themselves to education and teaching the next generation.

[Page 512]

D. The institute for the preparation of teachers and educators in Kishinev

Since 1921, the leaders of Tarbut had been worried about the future of Hebrew schools under Romanian rule, but the inner pressure to expand their work did not diminish. They decided to set up a seminary to train teachers. Yitzhak Alterman, a well-known educator and pioneer in the Hebrew kindergarten, worked on behalf of the Tarbut central committee and brought in important agencies and active people from other organizations. The new institute opened in 1923. It operated for three years, from 1923 to 1925, and trained 72 early-childhood teachers. There was no possibility of obtaining a permit from the government for this institute so they chose a different path. Tarbut received permission to offer evening courses to teach Romanian and various crafts. The institution planned to open workshops for sewing and embroidery, painting and ceramics, bookbinding, and simple carpentry. The director was Mrs. Miriam Landau, the wife of the director of the national lottery.

In addition to the principal, Yitzhak Alterman and the official director, several educators were invited, including the author Avraham Epstein, Netanel Overbukh (author of science textbooks), Dr. Yaakov Bernstein-Cohen, Leib Glantz, Nachum Tulchinsky (Tal) and others. At times, the authors Shlomo Hillels and Yaakov Fishman joined, as well as excellent instructors in piano, rhythmic, games and orchestra. There were also teachers for special crafts and for work in the gardens.

The institute also had two model kindergartens under the leadership of Bella Alterman and Kratchavskaya, followed by Hannah Gortzenstein (Tversy). The students were able to practice teaching in these kindergartens.

The workshops were equipped with modern tools and served as laboratories for both learning and practice. The work was challenging. In the final three months, the students received training specific to teaching kindergarten, such as making miniature furniture, dolls' clothes, art projects, weaving, paper cutting, and more.

Thanks to this wonderful institute, the status of Hebrew education rose. It became the crown of all educational institutions. Despite the legal difficulties, the number of kindergarten classes doubled and later even tripled.

[Page 513]

In 1924/25 and 1925/26, in Bessarabia alone, there were 36 kindergartens. In Moldova and Rigat there were 5 more, employing 52 teachers and assistants. Altogether, they taught over 1,100 children.

The Hebrew kindergarten was a kind of magnet that even won over the hearts of those who hesitated to send their children to the Hebrew school, which had limited rights and imposed a heavy financial burden on parents. The modern Hebrew kindergarten always impressed the official inspectors. Dozens of reports from their visits attest to this. More than once, inspectors brought the principals of the Romanian state kindergartens, most of whom had no professional training, to the Hebrew kindergarten, to observe and learn from the Hebrew kindergarten teachers. The institute gained a reputation beyond the borders of Bessarabia. It even earned the sympathy and solid support of the Jews of Romania. The Hebrew kindergarten earned an honorable place within the activities of the Women's Zionist Association (WIZO) in many cities and towns in the Rigat region, because it also posed a challenge to all national action. Thanks to the kindergarten, the level of the local schools, including the “Israelita Romina” type, originally established to provide general education with only limited Hebrew instruction, began to rise.

The first class of the institute, in the summer 1924, graduated 23 kindergarten teachers. All of the graduates had at least a high school education. This number did not satisfy the many requests that reached Tarbut in Kishinev, and there was a demand from outside Bessarabia as well. In 1925, the second class included 24 kindergarten and 25 elementary teachers. They were unable to complete their training because the institute was closed.

Alterman and his teachers managed to instill enthusiasm for their craft in the hearts of these young women. Because of Alterman's fatherly devotion to each student, even in personal matters, a strong lifelong bond was formed. Even though he was busy administering the institute, both financially and pedagogically, Alterman still found time to visit distant places in Bessarabia to guide and direct new kindergarten teachers who were struggling. This warm and friendly connection between the students, Alterman, and his fellow instructors, grew into a close relationship. His staff consisted of Avraham Epstein and Nachum Tulchinsky (Tal). Similar ties also existed among the graduates and remained strong for many years.

The first conference of the Association of Kindergarten teachers took place on 22 - 26 of September 1925. The conference addressed both pedagogical and organizational issues.

[Page 514]

Forty kindergarten teachers attended along with many guests from Kishinev and other places. Miriam Diner-Goldstein presided and opened the meeting with a report on the state of the organization in its first stages. The first order of business was to send congratulatory telegrams to Alterman and Tulchinsky who were already in Eretz Israel, and to Avraham Epstein in America. This was followed by greetings from Leib Glantz, a former teacher at the institute and a representative of Tarbut.

Those chosen to lead the conference were Chana Gortzenstein (Twersky), Mania Shor, and Miriam Diner-Goldstein as secretary. The permanent committee included Rachel Baron, Rivka Berkovich, Chana Gortzenstein, Rachel Lev, Bracha Messerman, Mania Shor, and Bluma Schneerson.

Miriam Diner-Goldstein presented a detailed report about the activities of the committee and the special interests of the organization. There were also reports about the actual work taking place in the kindergartens. Gortzenstein spoke about the model kindergarten of the institute. Grinberg and Lev reported on Yavne in Kishinev, Moshenzon-Rabin on Lasi, Schneerson on Orgeyev, Harshanok on Artziv, Kizhner on Leona, Messerman on Savan and Moldova, and others.

Lectures were delivered by Chana Gortenztein on the religious movement in education, by Miriam Shor on the Montessori system and by guest speakers Leib Glantz on music in kindergarten, and Dr. Moshe Vineshlboim on children's health. In addition to organizational decisions, the conference issued a strong protest against the government for its persecution of minority educational institutions in Romania.

The following were elected to the central committee: Grinberg, M. Diner-Goldstein, R. Lev, Sh. Sfader, G. Kilisky (Drakhlis) from Kishinev; C. Gortzenstein, M. Moshenzon-Rabin, B. Messerman and Shor, from the smaller towns.

The pride of the Hebrew school

The first four years of Romanian rule, from 1918/19 to the end of 1921/22, were blessed and creative times for the Tarbut movement in Bessarabia. At the beginning of 1920, Tarbut was registered in the tribunal of Kishinev as a central judicial body. It had already been active since 1917 and had 30 branches in smaller towns. The temporary committee consisted of: Sh. M. Berliand (chair), Eliyahu Ortenberg, BenZion Baltzan, Israel Berman, Aharon Finbron, Yitzhak Schwartz, Asher-Zelig Shokhetman (Al Yagon) and Yitzhak Shreibman (Shari).

The stream of refugees from across the Dniester brought many important educators and teachers to Bessarabia. Some settled in the capital, Kishinev, which became a gathering place for refugees and an important center for Torah and education.

[Page 515]

The newcomers worked hard to fortify the new educational network. This network was originally founded in haste at a time when people were afraid to exercise the national rights awarded to the Jewish minority by the Romanian government.

Haim Grinberg, head of the Education department of the Zionist Center in Romania, arrived in Kishinev at the end of 1920. He was on the way to Berlin to help establish an international organization for the Hebrew movement. In the meantime, he was drafted to help with the first fundraising event of Karen Hayesod and stayed in that position for several months. The Tarbut Central Committee used his sojourn for a broad publicity program and for a series of lectures on cultural topics. The income from some of the lectures, given in a magnificent hall that attracted many educated attendees, was donated to the Hechalutz movement. Some years later, the hall became a center for anti-Semitic theology students.

Among the refugees who stayed in Kishinev for some time were the famous educator, pedagogue Yitzhak Alterman, the writer-teachers Avraham Epstein and Shlomo Hillels, the teachers Yaakov Wasserman and Nachum Tal and the businessmen, Leib Glantz, Leah Vidrovitz, Tzadok Weinstein, Yechezkel Monzon, and Israel Skwirsky. Last but not least was the writer Yaakov Fishman, a native of Bessarabia. He visited Kishinev for lengthy periods and added immensely to the cultural life of his homeland.

By the end of this period (1922), and not counting the fourth government high school, there were 74 educational institutions, along with many Hebrew evening classes.There were 20 kindergartens, 40 elementary schools and 15 high schools. Some of these schools were established in 1918 and some earlier. Some of the schools taught general subjects in Hebrew. All together, there were about 10,000 students and 450 teachers.[18]

It is, therefore, surprising to read the statistics given by Zev Igrat in his article “The character of Hebrew education in Bessarabia” in “The Land of Bessarabia”, Volume A, page 110, edited by K.A. Bertini. His figures were said to be based on the article by Sh. Hillels, mentioned above, yet that article did not mention any statistics.

Igrat erred by stating on page 109, that the writer Sh. Hillels was active in Hebrew education in Bessarabia during the years 1918-1922. Hillels himself, in the article Educational Paths, said that he moved to Ukraine in 1918 and only returned to Bessarabia in the 1921/22 school year.

[Page 516]

In addition, there were several private high schools for Jewish students where the history of Israel was taught, sometimes in Russian as well as in the Hebrew language only. In Kishinev there were two schools for boys and girls founded by “Ozrey Hamischar” (Business Helpers), Goldenberg's high school, and evening classes for young men conducted by A. Weisman as part of a high school program. There were also schools in the villages of Brichany and Yedinitz in Hotin district.

At this point, it is necessary to present some statistical information about the condition of the Yiddish language schools in the years 1921/1922. These figures were published in “Arbeiter Tzeitung” (Worker's Newspaper), founded by Poalei Zion in Czernowitz, in issue Number 4, 15 January 1922. It was a report from the 2nd Cultural Conference of all-Romania, Czernowitz, 6-9 January 1922:

Especially interesting for us in Bukovina, was the report delivered by comrade Sherman, the inspector of public schools in Bessarabia. He noted there were 52 Yiddish elementary schools. Thirty-eight were under government supervision and 14 were private. Altogether, these schools had 147 classes and 5,757 students. This represented only 12% of the Jewish population of Bessarabia. There should have been three times as many schools. The government committed to establish the missing schools within the next 5 years. There was a great need for teachers, mainly in smaller towns. Despite this, the schools were well organized, and the curriculum was at a high level. The future in Bessarabia belongs to the Yiddish schools (underlined by the citer), despite the great obstacles and opponents. The Jewish Teachers College in Kishinev had enormous success.

[Page 517]

The following was published on 23 April 1923 in Arbeiter Tzeitung:

Baraz describes the founding of the Yiddish school, its struggles with Russification and Romanization, and the obstacles placed on its way by the bourgeoisie(?). The lack of qualified teachers brought the Yiddish school to a dying situation (citer). The teaching of Yiddish was in a dire state. The public schools allowed only a very small place for the teaching of the children's mother tongue.

From the school year 1923/24 onward, Yiddish disappeared completely from the public schools in the villages of Bessarabia. Only 3 private schools remained in Kishinev. Two were vocational schools for girls, and the third was an elementary school directed by Shepsel Weisman[19].

The legal reason for the existence of the national school

As previously noted, the first recognition of the right to establish national schools in Bessarabia after its annexation by Romania was proclaimed by the King on 14 August 1918. This right was reaffirmed in Romania's formal commitments within the Peace Treaty signed in Paris, on 9 December 1919 and again on 26 October 1920. These commitments were intended to respect the rights of the national minorities within the borders of Romania. The government repeated this on 26 March 1923 with a clear declaration in Parliament. Here are some of the sections from the peace treaty of 9 December 1919:[20]

Section 1. The Romanian government is committed to following the specific conditions in sections 2-8 of this chapter. These will be basic laws. No other law or regulation will contradict these conditions. No other law will prevail.Section 2. The Romanian government is obligated to grant all its citizens full protection of their life and freedom, without difference as to place of birth. Nationality, language, race, and religion will be respected. All citizens of Romania, generally and individually, will have a choice of worship.

[Page 518]

As long as the choices do not contradict general order and proper behavior.

Section 7. The Romanian government undertakes to grant full citizenship to all Jews living within its borders, provided they do not prefer another citizenship.

Section 8. All citizens of Romania will have the same legal rights and will receive help from civil and political privileges, without restriction based on race, language or religion. Differences in faith, religion or viewpoint will not be a reason to differentiate among Romanian citizens as he carries out his civil and political rights. It is especially so when it comes to public service, the granting of titles, and participation in artistic or business endeavors. No citizen's freedom will be curtailed when it comes to religion, journalism, publications, or public assembly.

In addition, when the Romanian language becomes the official language, provisions must be made to allow all citizens who speak another language, to be able to use their language, orally and in writing, and in court appearances.

Section 9. Citizens of Romania who belong to ethnic minorities, defined by language or religion, will have the same rights as all other citizens. They will be allowed to establish, direct and inspect, institutions of aid and charity, schools or other educational institutions. They will have the right to use their language and to practice their religion freely.

Section 10. For public education, the Romanian government shall provide suitable arrangements for the proper education of children in their own language, in towns and districts where there are citizens whose language is not Romanian. This provision does not limit the government from instituting the study of the Romanian language.

In towns and districts where a large majority of Romanian citizens belong to a minority defined by language or religion, funds from the public budget shall be allocated to the federal and municipal authorities to support that minority's educational, religious, and social aid institutions.

This last section is a repetition of section 7 of the public elementary education law and of section 11 of the public high school education law. However, it was only an act of formality. In reality, fulfilling it was like waiting for the Messiah.

There were several internal and eternal factors that caused the Romanian government, in the four years after the annexation of Bessarabia, to conduct a liberal policy towards the Jewish minority. During this period it recognized the national language as an official language of instruction in the schools.

[Page 519]

On one hand, the government was committed to the peace treaty it had signed with Britain, France, and the United States after WWI which guaranteed the rights of minorities. On the other hand, by upholding these minority rights, the Romanian government found a means of limiting Russian cultural influence and Russification in this former southern Russian province. The same was true of Germans in Bukovina. The Romanian language was still strange for the population. After the first years of annexation of the new provinces, the regime did not have enough teachers. Before the war, Romania had a population of 7.71 million. After the war Romania reached a total of 17.5.

Are the Jews also included in the minorities?

It did not take long for the Romanian authorities to go back on their commitments. Starting in 1922 they flooded the national education institutions with restrictive decrees. Their goal was to make Romanian the dominant language, weaken these institutions and destroy them. In addition, the authorities viewed Jewish community in Bessarabia as ideologically and politically “defective.” It was influenced by ideas of equality and national freedom by the Russian Revolution. Therefore, it was necessary to rid it of these notions. The first to act was the Minister of Education, Dr. K. Angalescu, (supposedly) of the Liberal Party. In early 1922, his government replaced that of General Avarescu. Angalescu brought changes that harmed our national rights. He was infamous for his hatred of Jews. In July 1922, supported by a small minority, he ordered the closure of the pedagogical courses established by the regional education directorate. He closed the fourth government high school, in Kishinev, the only school in Bessarabia with instruction in Hebrew. His reason was that the school had fewer students than in a Romanian school, and its budget placed a heavier burden on the treasury. In December 1922 he cancelled the Education Committee. In an interview with a Tarbut mission headed by Dr. Bernstein-Cohen and the legal advisor Shmuel Rosenhaupt, the Minister, denied an obligation to uphold the treaty on minority rights. His reasoning was that he had not personally signed the treaty. By this, he meant that the Liberal party had refused to sign it, and the actual signature was added later.

[Page 520]

It was signed by a transitional government under Veida-Veiavod. At the end of the discussion Angalescu added: “Are the Jews also included among the minorities?”

With that remark, the true intentions of Minister of Education Angalescu became clear. It was clear he was interested in forced Romanization in every area. The Jewish community prepared itself for a constant struggle with the powerful minister and his followers.

It is important to mention the following decrees, which at that time, most severely affected the elementary schools:

Establishment of the Judicial committee

The serious danger facing the Hebrew schools led the Tarbut Central Committee to establish a Judicial Committee. Its job was meant to provide legal advice and direction, and to protect the rights the government had granted to the Jewish minority following the annexation of Bessarabia by Romania. Soon after, the government began to deny these rights. The Judicial committee maintained a steady and close contact with the heads of the Ministry of Education in the capital, as well as with provincial inspectors. The committee managed to reach its goals. The productive activities of the committee flowed like a second thread during all the years of the central Tarbut organization. The committee worked not only for the good of the Hebrew school, but also for all branches of the national schools, Yiddish and religious. In all dealings with the authorities, the term used was the Jewish school, not the Hebrew school. Because of this, the authorities regarded the committee's spokesman, Shmuel Rosenhaupt, as the representative and defender of all Jewish schools in Bessarabia. The funds given by the government to the Jewish minority in Bessarabia were transferred to Tarbut, which then distributed them among the institutions.

|

|

Right to left: Row 1, seated: Mrs Hillels, D. Schwartzman, Yitzhak Alterman, Yechezkel Monzon, David Rabelsky, Dr. Yakov Bernstein-Cohen, Leah Vidrovitch Row 2, standing: Advocate Shmuel Rosenhaupt, Yehudah Harrison, Yakov Wasserman, Israel Berman, Nahum Tulchinsky (Tal), Shlomo Hillels, Al. Gershanuk, Zadok Weinstein, Avraham Epstein Row 3, top: Zvi Torkanovsky, David Vinitzky, M. Koblanov, A. Malamud |

|

|

Right to left. Row 1 seated: Shlomo Berliand, Yakov Fikhman, Nahum Tulchinsky, Yitzhak Alterman, engineer Mordechai Gotlieb, Israel Berman Row 2, standing: Israel Skvirsky, Shmuel Rosenhaupt, Yakov Wasserman, Yechezkel Monzon, Zalman Rosental, Leib Glantz, Yosef Dolitzky Row 3, top: Hertz Weinberg, Zvi Torkanovsky, David Vinitzky |

|

|

From bottom up, right to left. Row 1 seated: 1. Unidentified. 2. Yochanan Kaplivatzky. 3. Dr. Alexander Shor. 4. Dr. Efraim Porat. 5.Eliyahu Meitus. 6. Unidentified. 7. Yitzhak Yashan. 8. Unidentified Row 2 Standing: 1-3 Unidentified. 4. Shimon Horvitz. 5. Unidentified. 6.Israel Gleizer. 7-11. Unidentified. 12. Dr. Sh. Z. Yitzkovitch (Yitzhaki) Row 3 standing: 1-2 Unidentified. 3. Zev Be'eri. 4.Yehudah Veinberg. 5. Unidentified (Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify many of the students even though they signed the picture given to their beloved teacher, the poet Eliyahu Meitus. They are David Itzkovitch, David Hellman, B. Sheva Safra, Anna Gleizer, Rachel Roitman, Netanel Soroker, Zvi Veisman, Haya Lifson, Hadassah Tchegornit) |

|

|

From bottom to top, right to left: Row 1, seated: 1) Nachum kizhner, 2) Maganzin, 3) David Hershkovitch, 4) Dr. Efraim Porat, 5) Dr. Alex Shor, 6) Eliyahu Meitus, 7) Nachum Fidelman Row 2, standing: 1) Sh. Hukovsky, 2) Otilia Feller, 3) unknown, 4) Rozenbauch, 5) Bat Sheva Schechter, 6) Yakov Gluzman, 7) Zhanta Schechter, 8) Zev Vineberg, 9) unknown, 10) Efraim Davidzon Row 3, standing: 1) Yeshayahu Khazin, 2) Shraga Reicher, 3) Tortchin, 4) Baruch. 5) unknown 6) Avraham Grinberg, 7) P. Roitman, 8) Yosef Kleiner |

|

|

1. Rachel Tzukerman. 2. Leah Steiner. 3. Yael Drakhlis. 4. Bracha Messerman. 5 Sara Staratz. 6. Buzia Friedman. 7. Nava Gorenstein. 8. Dasha Posek. 9. Malta Fliss 10. Polyamory Fishman. 11. Unidentified. 12. Esther Radushovsky. 13. Shifra Tabatchnik. 14. Guinea Grashnuk. 15. Bliuma Shan. 16. Unidentified. 17. Heissiner.18. Yehudit Bercovitch. 19. Tova Heissiner. 20. Chava Rechter. 21. Unidentified. 22. Chana Vagman? 23. Malta Steinberg. 24. Leah Twersky. 25. Carpentry teacher. 26. Tarabikin. 27. Sofia Grig, Mathematics teacher. 28. Schatz, piano teacher. 29. Dr. I Bernstein-Cohen, hygiene teacher. 30. Yitzhak Alterman. 31. Avraham Epstein. 32. Pianist. 33.Nakhum Tulchinsky. 34. Bella Alterman. 35. Tarniansky. 36. Liusya Levental 37. Rachel Lev. 38. Kayla Grinnerg 39. Mrs. Danishansky 40. Chana Fisher? 41. Rachel Kirchner 42. Dvorah Berman 43. Etel Broitman 44. Hinka Sobelman 45. Rivka Bercovitch 46. Heissiner? 47. Sroib? 48. Rachel Baron 49. Unidentified 50. Adina Kharad? 51. Fanta Shor. 52. Mrs. Shteinberg. 53. Yaffa Yankelevitch. 54. Chana Gortzenshteyn 55. Miriam Moshenzon. 56. Chana German. 57. Mrs. Liberzon. 58. Mrs. Bondanovsky. 59. Nusia Kilisky (Drachlis). 60. Shoshana Edelman. 61. Shoshana Girenshtwyn. 62. Unidentified. 63. Miriam Baron. 64. Bliuma Schneerson. 65. Chana-Simka Twersky. 66. Mrs. Shinder. 67. Unidentified. 68. Mrs. Yadlin. 69. Haya Bernstein (Tzukerman). 70. Mrs. Brokhovitch. 71.unidentified. 72. Mrs. Raubuver? 73. Chana Berger. 74. Mrs. Pakelman. 75. Sara Sfarad |

[Page 521]

The work of the Judicial Committee also strengthened the internal front. To that end, meetings were held from time to time with parents, teachers, and principals to discuss problems and suggest ways to solve them.

The first Tarbut conference

After four years of building and developing the Hebrew school system at all levels, Tarbut held its first conference, which took place in Kishinev on September 5-9, 1922.

A month earlier, on 8 August 1922, there was a meeting in Berlin of the executive of Hitachdut (the Union). It was a conference of educational and cultural experts in the Diaspora, in line with the aspirations of the Labor Zionist movement. Yitzhak Alterman represented Bessarabia, and his topic was “pre school education”[21].

The first Tarbut conference was opened in Kishinev in Union Hall by Yitzhak Alterman. There were 60 representatives from 31 locations and many guests. Among them were Motti Rabinovitch, the representative of the Zionist Federation in Bucharest, and Israel Zamora, an author and representative of the school in Botoshan. There were also educational representatives from Bravia, Galatz, Lassi and other towns.

In his opening remarks, Alterman indicated that the Tarbut movement was entering a second stage in its development. The urgent need to inculcate the Hebrew language was over; that goal had been achieved. There was no time or patience to argue with enemies over theoretical disputes. The entire movement was engaged in practical, concrete work. No speeches were necessary. We have a historical duty, he said, to continue our struggles and to make sacrifices, both material and spiritual, in order to move forward and protect our rights. After greetings from various organizations, elections were held. Yitzhak Alterman and Shlomo Hillels (Kishinev), I. Baratin (Tarutino), Hillel Dobrev (Yedinitz), Yakov Reidel (Beltz), Zvi Schwartzman (Bendery) and Dr. Alexander Shor (Lassy).

Picture notes:

Author's footnote:

Original footnotes:

In old Bessarabia it was unanimously agreed that: “the Jewish Cultural Federation recognizes Yiddish as the only national language of the Jewish people. That is why it must be the only language of instruction in the new school.” (Cultur collection, Czernowitz, 1921, page 94. Return

1. Latin language - by Liubomordov S. And Palmer G. Including a Latin-Hebrew dictionary, edited by Oyerbuch (1920).

2.Geography - by Zvi Schwartzman 1921.

3. Botany for beginners - by Netanel Oyerbuch, 1921.

4.-5. Zoology for beginners, Vol. A and B-by the above author, 1922.

6-8. General History, 3 volumes, by Shmuel Gorin and Yitzhak Reznikov (translated by Sh. Veisman), 1922.

9. Mathematics in Hebrew - by I. Reznikov 1922.

10. Geometry - by M. Shaicovitch, A. Rabinovitch, 1922.

11. Latin grammar - by I. Reis, G. Oyerbuch, 1922.

B. Published by Moriah (I. Berman).

1-3. Ancient history, 3 booklets, by Israel Berman, 1921-23. Return

1. Nitzanim, Book 1 after Aleph Bet - by I. Reidel and I. Wasserman, 1923.

2. Nitzanim, second volume for grades 3 and 4 - authors as above, 1923.

3-5. Bible stories, three books, prepared and explained by I. Wasserman and I. Reidel.

6-7. Knowledge of science for elementary schools - by I. Reidel, 1922. Return

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

The Jews in Bessarabia

The Jews in Bessarabia

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 17 Feb 2026 by JH