|

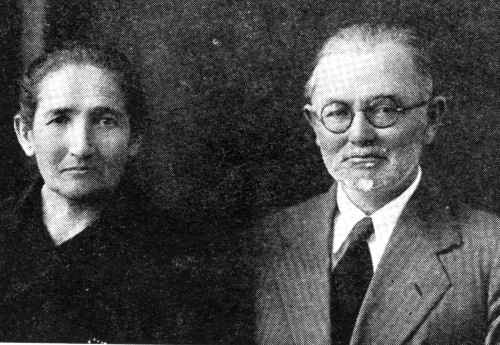

(may their memories be for a blessing)

|

|

[Page 155]

[Page 156]

[Page 157]

by Y. R.

Translated by Yael Chaver

Was there anyone who didn't know Aharon, Arkeh Shenkelman? In a town as small as Zinkov, everyone knew each other, even those who lived ten streets apart. And anyway, how many streets did Zinkov have? And yet, there were different grades of popularity.

Unlike most in our little town, Arkeh Shenkelman did not have a nickname. Arkeh Shenkelman, the Hebrew teacher and pharmaceuticals supplier, was simply called Arkeh, or Arkeh, Moyshe Idel's son, after his father. Both Arkeh and his father were teachers and educators in their time and place. My father, may he rest in peace, would often mention his teacher Moyshe (Idel's son), and describe him as a literalist, who liked the simple explanation rather than subtle, often casuistic explication. People who held their ground were called “blockheads” (“stupid brain”): “In any case, you don't know the difference between the right and wrong versions, so how can you be discussing the wrong version?”[3]

His son Arkeh was shrewd. He did not accept conventional ideas, always imagined the future, and dreamed of poetry. He had a vast knowledge of Hebrew, knew all the details of the verb conjugations, and was a stickler for style and grammar. Woe betide the student who didn't know the conjugations and who couldn't distinguish between a dagesh hazak and a dagesh kal.[4] I don't know whether he was an expert in Talmud, Halacha, and medieval Hebrew literature, but he would explain a chapter of midrash or the Ibn–Ezra commentary so simply and easily that even the slowest student could understand him.[5] He especially loved teaching Bible. The Bible was his pet–he could inspire the whole class to enthusiasm and exhilaration when he taught the Prophets. In these classes he would stand at the edge of the dais, recite the words of the specific prophet and punctuate them with excited commentary. The pupils would sit motionless, intently listening to his words; he seemed to be inspired by the prophet himself.

Arkeh's voice was pleasant, and when so moved, he would lead community services. Sometimes he would enter our house on the eve of Shabbat, after the ritual candles and the lamp had flickered out.[6] He would come in silently, without anyone noticing, and amaze everyone in the next room by singing religious or secular songs in his sweet voice. After he had finished singing, and the next room was silent, he would walk in and say Gut Shabbes![7] Then he would leave. He had a permanent role in the minyan in which he and Father and their friends

[Page 158]

prayed: on Tisha b'ov he would be the one to recite the biblical Book of Lamentations. His emotion as he recited “I am the man” penetrated all hearts and moved everyone, and those few who are still alive will never forget his reading of this book.[8] Few knew that Arkeh Shenkelman also wrote poetry. My father would rarely show me one of these poems, saying, “Arkeh wrote this.” I would recognize the handwriting even without Father's note. His penmanship was beautiful, harmonious and rhythmic, “like a flock of sheep […] they match perfectly, not one is missing.”[9] Nothing has survived of all the poems he wrote while living in Zinkov. His son, Avraham, has saved only those poems that he wrote in Israel, after he arrived and settled in Raanana.

|

|

(may their memories be for a blessing) |

We are publishing some of these poems in our Zinkov Memorial Book; let them be a modest memorial to the man who shared his inspiration and knowledge with his students. His poems were very lyrical, and we have selected some in which he expresses his mood and emotions. These include his poems about Yiddish and Hebrew, his great love for the Hebrew language, his affection for Raanana (where he lived), and a eulogy for the national poet, Hayim Nahman Bialik.[10] Arkeh would have long conversations with the young people who visited the back room of his business about social and political issues; he was the one who inspired them with a longing for pioneering and social progress.

May his memory be doubly blessed!

Translator's Footnotes:

by Aharon Shenkelman

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

Eulogy for a victim of the riots, 1936

Your blood cries out to me from the soil, January 8, 1936

Your blood cries out to me from the soil Anthem to the Hebrew Language!

How pleasant and beautiful, you old–young.

When you were in exilic lands

When our sun shone in the Spanish exile

And in the desert of Czarist Russia |

[Page 160]

|

Raanana

a)

She shows off her charms

b)

No longer a naughty girl 1936 Eulogy for Hayim Nahman Bialik

How, how, and why, our Bialik,

You ascended to heaven, where your lyre will play Language and Morality [2]

The laws of ethics and the Hebrew language 1934 |

Translator's Footnotes:

by Y. R.

Translated by Yael Chaver

At the early age of 16, this only son of a refined father, a devoted mother, and a brother to three younger sisters, was courageous enough to stand guard over the garden at the edge of town, created and nurtured by the Zinkov halutz members, even spending the night there in a little hut. At 16 he also left home and went to Eretz–Yisra'el with the first group of halutzim from Zinkov. As he explained, he was going “to show the way to others.” It was not an easy road. They did not “fly on the wings of eagles,” had no legal passports, or covered travel expenses. Once they came to the country, they were not welcomed by open arms, but by malaria and hard labor. Avrom, or Avromtchik, as he was called, joined Gedud Ha–avoda, where he worked with the other members doing pioneering labor.[1] His older sister Dvoyre left for America, together with her aunt Basya and her two children. At that time, travelling was extremely hard, because of the Petlyura and Denikin bands who were rampaging through the region.

Both children, Avrom and Dvoyre, did not go to blaze new paths for themselves alone. Avrom went to help build a land for the nation, and Dvoyre became the caregiver for the family. Her boundless devotion to the family led her to work hard, sewing blouses for American girls in a shop, and sending money back home. She was able to bring the entire family to Eretz–Yisra'el.[2] She called on Avrom to come to America as well, and help her carry the burden of help for the entire family. Avrom had no choice, and came. He worked for many years, and witnessed the fate of workers in the “golden land.” Those were the worst times of the great strikes

[Page 162]

in the coal mines of Pennsylvania, and the first attempts to organize the steelworkers. Avrom started to work in a steel factory, and joined the movement to organize the steelworkers. He was brutally beaten more than once, by the “Cossacks,” the private storm–trooper army of the magnates, and barely escaped becoming an invalid.[3] He returned to Philadelphia, depressed and discouraged. In time, he met his future wife, and married. He established a fine family and had a good life, in both the private and the community sense. He was the chairman of the “Friends of Israel” organization, where he worked for the cause of Israel enthusiastically. But whenever he met his Zinkovites he would speak nostalgically about the years in Zinkov when they all worked in the halutz garden and dreamed about the future. He, and a nephew in Israel, were the only remnants of the noble Shenkelman family.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Yosef ben–David

Translated by Yael Chaver

He was noble–spirited, imposing – in all senses of the word, with a silver beard that added to his impressive appearance. He had been accredited as a rabbi, but refused to turn his learning into a livelihood.[2] He spent all his time studying, following the command “You shall meditate on it day and night.”[3] But with all his dedication to study, he did not lose touch with the surrounding world. He knew Russian, and was no stranger to secular study. When he needed to write letters to his children, who had emigrated to the U.S.A.

|

|

|||

(may her memory be for a blessing) |

(may his memory be for a blessing) |

(his daughter, may her memory be for a blessing, and his son Moyshe Fayngersh, may he live long), he decided not to ask anyone to write an address in a foreign language, but learned the Latin alphabet so as not to need anyone's help, even for writing out an address. He was very interested in his grandchildren's' education and tried to teach them, as pleasantly as possible, that a person should use every possible chance to increase his knowledge. He was busy with charitable and public affairs, with all possible modesty, so as not to appear a community leader. He had many clever, fine, and elegant sayings, such as, “Life in this world is nothing but a dream, but it is better to wake up from a good dream than from a nightmare.“

[Page 164]

His wife, Rivka (neé Sadikov) was a true helpmate. She managed the business and the household, supervising everything. She was the one who assured the family's livelihood. All who knew her appreciated her intelligence, practicality, and kindness.

They did not fulfill their dream of immigrating to the Land of Israel. Along with their son–in–law David Blinder, they closed their business in order to go to the land they yearned for. But their plans ran into problems. They did leave Russian, but the events of 1920 prevented their plans to continue to the Land of Israel.[4] They had to split up the group. Ya'akov and Rivka Hasid unwillingly emigrated to the United States, and never stopped dreaming and thinking of leaving for the Land of Israel. They were unable to do so, and died in a foreign country. It is a pity for those who are gone and no longer among us![5] May their souls be bound up in the bond of life.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Yosef Ben–David

Translated by Yael Chaver

|

|

He was a prodigy, a devoted student in the best sense of the word. He was engrossed in religious studies until the Enlightenment swept him into secular affairs. However, even after he began to be interested in secular studies and started studying to be a pharmacist, he was able to combine old and new, and derived the best and most useful from both domains. The pharmacy he managed in Zinkov became a center for Zionist youth, a type of club where people met and exchanged views on current affairs in both the general and the Jewish spheres. His compelling personality attracted young people, and he became a teacher, guide, and educator of the young generation in the town. He practiced what he preached. After he returned from the Zionist Congress in Vienna, he decided that the Russian spoken in his home would be replaced by Hebrew; his was the first home in Zinkov where Hebrew was the everyday language.[1] He organized evening classes for young people, which were held at the home of the Sadikov family. He and his friend Shmuel Fridman taught Hebrew to anyone who was interested. When contributions to “Keren Ha–Yesod” were requested, he asked his wife Liba (Ahuva, neé Hasid)–may she live long – to donate her most precious ring, as he believed that people should contribute something that was not only of material value, but, more importantly, had symbolic personal significance.[2] Dudi was not a great talker; deeds were more important to him. He donated and called on others to donate, and activated others as well as himself. He was able to energize every Zionist activity, whether it was for local purposes or for Eretz Yisra'el, and was always ready to act within the HeHalutz organization or gatherings in homes, on weekdays, Saturdays, or holidays. He was also willing to speak about Zionism in the synagogue on holidays and Saturdays, and advocate for Zionist ideology and emigration to Palestine.

[Page 166]

When it first became possible to emigrate to Eretz–Yisra'el, he sold his businesses, regardless of the prices, to achieve his goal as quickly as possible and emigrate to the land he yearned for. However, he did not reach his goal. After selling his businesses he and his family joined a wagon train bound for the Russian border. He left home, but never reached his goal. The riots of 1920 overtook him; entering Palestine became impossible. His life was lost at a young age, and he could not reach his goal.[3]

May his soul be bound up in the bond of life!

Translator's Footnotes:

by Moshe Ben–Shmuel

Translated by Yael Chaver

He was the son of Itzik Sadikov, a well–off – though not wealthy–householder. He owned a fine two–storey house, and was a wine dealer, with a wine cellar and a large selection of the most expensive wines. The Jews of Zinkov, of course, could not afford such wines. These luxury products were bought only by the rich landowners in the Zinkov area.

Itzik Sadikov's only son was Moyshe, who was studying in a gymnaziya in Proskurow or Kamianetz.[2] This Moyshe was a happy, cheerful, vivacious kid, loved by all the young folks. He was a real artist at imitating people, making fun of them and their expressions – a born actor; or, as people in this area would say, “a real clown.” Whenever Moyshe Sadikov came home for summer vacation, decked out in his school uniform, we would all feel happy. First, he would describe life in the gymnaziya with a real flair – the exams, the practical jokes on the teachers. He would especially mock the German and French teachers, when his acting talent would really shine. We guys would enjoy him and rock with laughter, full of envy for his uniform with the shiny buttons; and we envied even more the fact that he was studying in the gymnaziya, which we all longed for but could not attain. To this day, memories of Moyshe Sadikov evoke a warm feeling and a happy smile. Moyshe Sadikov is still alive somewhere, but no one knows exactly where. Some say that he's in Brazil, while others say that he's in Argentina.

Translator's Footnotes:

Yitzchok Itzikzon (Isaacson)

(may his memory be for a blessing)

by Moyshe Ben–Shmuel

Translated by Yael Chaver

Born in Zinkov, he emigrated to Argentina when young, where he lived a productive life and revealed all his talents as an activist of Yiddish culture and a journalist. His friend and colleague, Dr. Moyshe Merkin, who was greatly saddened at the news of Yitzchok Itzikzon's untimely death, wrote: “The deceased was not only a great scholar of Talmud and halakha,[1] but also a highly educated person in many secular domains. His industriousness, sense of responsibility, remarkable diligence, along with his modesty, earned him many friends and admirers. He was a very warm and dear friend, whom I really loved, and respected for his encyclopedic knowledge. It is a pity for those who are gone and no longer to be found! We honor his memory!”

One year after his death, his friend and colleague wrote a memorial article in the Yidishe Tsaytung, in which he said, “… during the forty years of his life in Argentina, he found his place working at the Yidishe Tsaytung.[2] His knowledge was vast and covered many areas, primarily in Jewish scholarship. He acquired this, first in his hometown of Zinkov (Podolia) and later expanding it in Jewish Odessa of the time, where he joined the circles of great Jewish scholars, headed by Yoysef Kloyzner.[3] He was an autodidact, constantly studying, never thinking of interrupting his ceaseless learning… He loved languages and knew many well, including Hebrew, Yiddish, Russian, and English. After Hebrew and Yiddish, he loved English most; he had studied it on his own. For the Yidishe Tsaytung, he would often translate political articles and commentary by important politicians and writers from English, as well as occasional brilliant, witty stories or articles by a great English writer…. Very few Yiddish writers in his circumstances have travelled as much as him. He was the only Yiddish writer in Argentina who travelled to Israel three times at his own expense… It took us a long time to grasp that Yitzchok Itzikzon had gone on a trip from which one does not return. We will remember him forever. Honor to his memory!”

[Page 168]

The famous American Yiddish–Hebrew writer and intellectual, Arn Tseytlin, wrote a belated eulogy about his friend, the playwright Yitzchok Isaacson, in the Tog–Morgn–Zhurnal (June 15, 1964): “Yitzchok Isaacson was ‘a scholar who was not properly eulogized’.[4] Born in Zinkov, Ukraine, he emigrated to Argentina many years ago, where he was a journalist, lecturer and language–instructor. He was a highly educated autodidact, a natural student who was constantly learning. Whenever he was free of his journalism work, he read and studied. He may have been the most highly educated Yiddish author in Argentina. He also had a rare sense of poetry. His taste, refined by world poetry, helped him position himself in Yiddish and Hebrew poetry. I met him when he visited New York. His dream was to settle in the Jewish state, but that remained a dream. His great passion was Hebrew philology. He considered Hebrew the mother of all languages, and hoped he would write the major work about Hebrew philology; that, too, was not destined to happen.”

Translator's Footnotes:

by Moyshe ben–Shmuel

Translated by Yael Chaver

Pessie was the oldest daughter of LeybleItzi–Maykes. Her father had a grocery, from which his family made a good living. She was very likable, medium–sized, with beautiful hair, symmetrical features, and slightly dreamy, affectionate eyes with the occasional flickering spark. Her voice was quiet, clear, and pleasant. Though she tried to conceal it, those who knew her well were aware that the quiet and modest demeanor masked a free temperament and a strong lust for life. Pessie Shraybman had a fine theatrical talent. She was known in the amateur theatrical group of Zinkov as the “prima donna.” She really distinguished herself in such roles as “Khashe the Orphan,” “Mirele Efros,” “God, Man, and Devil,” and other roles.[1] In general, she was a fine young girl, who was good company and a good conversationalist.

[Page 169]

Our friend Yisro'el Roytburd recounts that when he had already crossed the Russian border and was in the town of Czortkow, Pessie Shraybman also arrived with the goal of emigrating to America.[2] But she soon changed her mind. “I don't want to part from my parents, sisters and brothers, and go to such a distant country, and never see them again.” She soon returned to Zinkov, issuing her own death sentence. She and her entire large family, for whose sake her sensitive conscience impelled her to return home, were murdered in 1943, during the grisly brown Nazi plague.

Translator's Footnotes:

by Moyshe Ben–Shmuel

Translated by Yael Chaver

Sima's parents were poor. Her father did not earn enough to sustain his family and give his children a proper education. They really struggled until the boys grew old enough to learn a trade; with their help, the family's life became a bit easier. Her older brother Meir was the guy who is mentioned in our memorial book, in the chapter headed “How Czar Nikolai II was removed from the throne in Zinkov,” which described the first May 1 demonstration in Zinkov. Sima received no systematic education, but had the innate ambition and will to achieve a higher esthetic and cultural level. She did so, thanks to her own talents and resolute efforts to attain the goal she had set herself. She worked hard, and eventually became a wise, interesting person who could fit into any organization. She also acquired a good profession: as an outstanding milliner, she earned enough not only for her own needs but enough to help her family as well.

She grew up to be tall and slim, and was remarkable for her pleasant looks. She also had a talent for making friends, and was always the center of younger girls who were dreaming of the springtime of their lives and the ambition to achieve something they themselves could not express. These

[Page 170]

young, partly grown children approached Sima with love and wonder, and sought her inspiration and spiritual leadership. I remember a few of her devoted disciples – Leyke–Peysie, Sichkarnik's daughter; Liza, Zaynvl's daughter; Tsirl, the daughter of Froym Bontshik; the sister of Isaac Feldman; and others. Leyke is living in Buenos Aires and corresponds with Sima. Sima was especially close to Etl Kagan, or Etl, the daughter of Ezri Arn. Etl was small and not pretty, but was remarkably smart and was very knowledgeable. Sima learned much from her. Etl should have earned a status of her own, but was unable to achieve it due to local circumstances. Sima is still living, in the Soviet Union. Her personal history is very sad. The war with Nazism ruined her life: she lost her husband in the war, both her sons returned as invalids, and she herself is three–quarters blind by now.

The few sketches we have presented here are characteristic of the fate of our young generation during that period. Some are scattered to the ends of the earth; others have been wiped out, obliterated, oppressed, or tortured. This is the road our persecuted, suffering nation of martyrs must walk. I would like to hope that the current younger generations of our people, and of other nations, will eventually find the way to a finer, better world.

by Moyshe Ben–Shmuel

Translated by Yael Chaver

Izya's father was Hershl Baytlman, one of the intellectuals who arrived in Zinkov in the second half of the 19th century. Those young people were not familiar with non–Jewish schools, colleges, or gymnazyas. Yet they attained a fine level of education for their time. They knew Russian and Hebrew well, and were familiar with the literature of both languages – all through self–learning. Hershl Baytlman was a teacher. He died in middle age, around 1904–1905, and left behind a wife and an 8–year old son, Izya.

[Page 171]

Some time later, his widow, Nechama, opened a tiny store devoted to medicines and cosmetics. She had a hard time making a living, and sent Izya to Sumnevich's school.[1] Izya loved music, and his mother managed to obtain a violin for him, which he learned to play by himself. When Izya finished school, he gradually started to help his mother in the store; Nechama, for her part, learned how to make false teeth. Life became easier for them.

|

|

Izya was short, with a fine head of curly hair, a short, upturned nose, and beautiful brown eyes. He had a particular charm and a bearing that made him very popular with the Zinkov girls. His best friend was Moyshe Garber; the two were inseparable. They were therefore known as “the twins.” They grew up together, experienced the happy prewar years together, and took private lessons to study for the position of pharmacist's helper. They traveled to Kamenetz for the examination, and suffered together. After the revolutionary upheavals of 1917, the two friends joined the army together in the struggle to safeguard their newly found freedom – as did many young Jewish men at the time. When conditions finally stabilized, the friends parted. Moyshe Garber went to America, and Izya joined the Communist party, where he gradually rose in the ranks and attained a high position in the government department of trade unions. Izya married one of the finest girls in Zinkov – Rokhl, Shloyme Gelman's daughter, who was a teacher in a government school.

Both were murdered by the German cannibals, in Vinnytsia.

Translator's Footnotes:

Rokhl (Rachel) Kuzminer

by Khayele Klassik

Translated by Yael Chaver

Rokhl Kuzminer was the owner of a notions shop in Zinkov. She was famous in the town and its vicinity as a very generous person, who was always ready to support anyone in need. She was best known for this admirable trait of charity. There were small shopkeepers in Zinkov who lived, as the saying goes, from hand to mouth. They never had enough savings to buy merchandise for a holiday or a fair, when they might have a chance to earn more. Wholesalers would not give them credit. If not for Rokhl Kuzminer, who gave them loans, their situation would have been dire. Often, she didn't have enough ready cash to satisfy the requests of all the shopkeepers. In such cases, she would borrow money from a moneylender at high interest rates, and give it to the shopkeeper as a free loan. She required no promissory notes from her debtors, but only wrote the loans down in a special book. Often, the shopkeeper was unable to repay his debts at one time, and had to incur additional debts before paying off the earlier ones. The list of debtors and the amounts of debt would thus increase. But this charitable woman was not discouraged, and continued her good deeds. It's worth adding that Rokhl's fine practice was a tradition she had inherited from her mother–in–law Basia and her husband Zosya Kuzminer.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zinkiv, Ukraine

Zinkiv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 23 Sep 2020 by JH