|

|

|

[Page 97]

by Shmuel Korin

Translated by Aryeh Sklar

It is very hard for me, after nearly a lifetime, to recount the memories of my childhood and youth in that town where I was born and raised. After all, forty–four years have passed since I left its confines and made Aliyah, the only one of my family to do so. The rest of my family remained there, living their lives under the Soviet regime.

I was able to maintain a written correspondence with them until the destruction of the town in the hands of the accursed Nazi enemy.

Most of my family, including my father and mother, were murdered. The only ones who survived were my brother, who served during the war in the Red Army, and my sister, who was living near Leningrad at that time, and was able to escape with her life before the enemy arrived there. It is thanks to my brother and sister that I even know the exact date when my family, as well as many others of the townsfolk, were put to death–it was August 4th, 1942.

My father, whose name was Meir Yosef Korin, had been called in by the Rebbe Reb Moshele and his acolytes who were from that town to assume the rabbinical pulpit and serve as teacher and halachic ruler for their parish.

I was the eldest, and I was about five years old when we followed my father to live in Zinkov, and from then until I reached adulthood, there in our town I grew up and there I was raised.

In his capacity as the rabbi, my father, of blessed memory, was not just the authority on matters of kosher law, but he was also an arbiter on interpersonal matters, and he was dedicated to his parishioners–tending to the sick and providing for widows and orphans. Our home was wide open to them, and throughout the day many different people would be coming and going. One came seeking counsel, another to ask for aid for someone who was sick, or assistance in tuition for orphans. There were also people who would come and appoint my father, of blessed memory, as arbitrator in their disputes. And there were even times when a dispute broke out between a Jew and a non–Jew and both parties, choosing to avoid appearing before a state court, would come to argue their case before my father, each of them confident in receiving a true and just ruling from my father.

One interesting and important detail comes to mind. There were four esteemed families from our town, who were leasing a large nearby flour mill, and a dispute broke out among them, and some of them wanted to take the case to the state court. My father, knowing that such an act would greatly entangle them, potentially bankrupting them, used his influence to prevent them from doing so, and for an entire month, night and day, worked with them to resolve the dispute and effect reconciliation among them. Long afterwards, the parties involved would cite this good deed and express their gratitude to him.

Although the people of our town were not wealthy, and most of them labored for a living, they were kind, and whenever there was a need, they always contributed generously to the best of their ability.

[Page 98]

I must bring up one detail in this context: at the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, an order was issued by Gen. Ivanov, commander of the southwestern front, that, since the Jews are suspected of spying for the enemy, any of them who live within 50 verst (1 verst = 3500 ft.) from the frontline, must, within 24 hours, leave their homes and go farther from the frontline. This was on a Thursday, and from the entire region surrounding our town, a flow of refugees arrived. Hundreds of families with their belongings arrived on farmers wagons, all in need of shelter. Our townsfolk, without exception, all responded to the present need and each home took in several families.

I remember that five or six families took refuge in our home. With the assistance of several of the town dignitaries, my father immediately organized a relief committee that set out to raise money for the families who had been rendered destitute. The next day, Friday morning, we youths set out, sacks on our backs, to collect Challah for the Sabbath from every home in town, to provide for the poor who had not yet had the opportunity to fend for themselves. Only after the Sabbath did a portion of the refugees set out to neighboring towns, and still, in almost every home, a family of refugees remained until the battlefront shifted away from us and the refugees could return home.

It is also noteworthy that in Zinkov lived the offspring of the Apta Rebbe. There were those who said that they had chosen our town as a residence because there were no Christian churches within it, unlike the nearby towns who all had standing at their center, at the market square, a Christian church. Not so in our town, where the Catholic and Orthodox churches were located in the valley by the Turkish fortress, out of the view of the Jews. And occasionally, when a Jew would come to town to visit the Rebbe or one of our townsfolk, or when on occasion a local Jew would head out to the synagogue to pray or to prostrate himself on the tombs of the rabbis, during the month of Elul, he would not encounter even a single symbol of the foreign religion on his way.

It is known that in Zinkov there were two Hassidic courts, that of Reb Moshe'le and that of Reb Pinchas'l. They were brothers, but did not get along, and the dispute between the two brothers extended to their acolytes, and to the townsfolk in general. The town was, therefore, divided into two: One faction included Reb Moshele and his acolytes and friends and family, and the second faction included Reb Pinchas'l and his acolytes and friends and family. My father and his family were among the acolytes of Reb Moshele. As a result, all I knew about the Rebbe and his court, was limited to Reb Moshele's faction. As it is known, around the holidays up to hundreds of Hassidim would arrive from out of town, many of them with their families in tow, to spend the festival within the court of the Rebbe. But from among the townsfolk at large, many would join one faction or the other, not only devout acolytes, but also people from among the “Jewish Enlightenment”, and even from among the youth, would come to bask in the light of the Rebbe's court. The Rebbe Reb Moshele was outstandingly noble, and many were his friends, and friends of his family, and the Rebbe and his family returned love and friendship to all.

Another memory comes to mind, when I was already eight years old and able to freely pray and even understand most of the liturgy. That year, I went with my father to the Kol Nidre service in the synagogue that was in Reb Moshele's courtyard. The spacious synagogue was packed with congregants of all ages, very old to very young. Many a Neshama (memorial) candle stood burning. By the prayer dais near the Holy Ark, sat the Rebbe, in his armchair, wearing a white Kittel, his prayer shawl over his back, on his head a white yarmulke interwoven with silver threads, and a crowd of acolytes and admirers surrounding him, handing him notes with requests. All of a sudden, it became quiet, and the Rebbe stood up, approached the dais, and began

[Page 99]

with the opening verses of the Kol Nidre service. And there was something special about his voice, about the impassioned words coming out of his mouth, and the utterance of his lips left an impression on the congregation. To this day, whenever I enter a synagogue on Kol Nidre night, that impassioned vision resurfaces before my eyes, and the noble image of the Rebbe reappears to me in all its glory, just like in those distant childhood days.

In our town there were not many state–operated educational institutions. There was one public school, attended by the children of the nearby farmers, and even some Jewish children, mostly girls. Boys were not sent to that school, because they had classes on Saturday and there were no Judaic studies in the curriculum, and they learned nothing except the official language and some math.

|

|

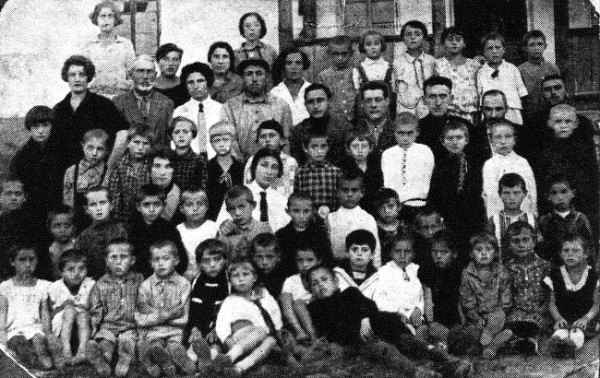

| The Hebrew School in Zinkov, faculty and students |

Parents made great efforts to provide their children with a Jewish education at their own expense, and they could not always afford the costs this entailed, even though for all of them the study of Torah took precedence even over food. The community operated and funded the Talmud Torah, which staffed educated teachers. In our town there were also many a private heder, where teachers drilled Torah into students for ten hours every day. Even on Saturday afternoons, learning did not cease, and they would study Ethics of the Fathers. Even during the intermediate days of Passover and Sukkot, study continued in the Cheiders. There were various types of Cheider, and they were adjusted to the age of the children, from six years to fifteen. Only Judaic studies were taught there, and for official language and math they would go to private tutors. There were also teachers from among the “Haskalah” – the “Jewish Enlightenment”, who possessed outstanding knowledge in Hebrew grammar and literature, and it was they who taught the youth a love and devotion to the Hebrew language and modern literature. And it was they who raised up a generation of students who made their parents proud, and when the first call came to make Aliyah, scores of Zinkovian youngsters arose and joined the camp of the pioneer rebuilders of the land of Israel.

by Yisro'el (Sani's son) Roytburd[1]

Translated by Yael Chaver

Thanks to the editor, the writer Moyshe Grossman

“Oh, somewhere, somewhere far away, far far away,

My childish heart dumbly desired

And longed so–* * * What did I want? I myself don't know.

I know only that it will never return”Hayim Nahman Bialik[2]

In Zinkov, Podolia province, Ukraine, there once stood a house. It had stood there since ancient times. If one took the time and trouble to rummage among the oldest gravestones in the cemetery, one could find the names of the ancestors of the family that had lived in the house. And these ancestors, I was told, had built the house with their own hands. The house was strong and solid, built of hard stone, with thick walls. It seems to me that the house stands to this day; I cannot believe that it was destroyed. The entrance to the house led over a low hill to the beginning of a narrow alley that was called “the between–stores.” It was a corner house, with a ground–floor apartment below and an upper floor with windows facing both sides of the street. Looking out of the eastern window, one could see not only the street but the fields as well, in the distance, across the valley on the slopes that led down to the valley and to the Ushytsia River.

In summer, it was a pleasure to see the changing colors over the hills; from the black cultivated fields to the green grass, from green grass to the golden waves of ripe grain. You could also see flocks of sheep in the early morning climbing up the winding white paths among the fields

[Page 101]

and see them again rolling down at twilight, like a marvelous, constantly shifting, wool carpet. In the fall, the fields were reaped and fine haystacks of stacked sheaves rose in straight lines, like drilling soldiers. When the sheaves vanished, leaving the fields bare, you'd know that winter was coming, and the starkness would soon be covered with a white quilt of crystal–clear snow. The house would start preparing for winter, buying all the necessities, fitting in the double windows, strewing sand between the panes, and cleaning out the chimneys of the central stove.[3]

Let me point out, for the children “who did not know” Zinkov, that the Zinkov Jews could enjoy the beauty of the surrounding fields and orchards only from a distance, but could not benefit from their bounty.[4] The wide fields did not belong to the Jews of Zinkov. The town bordered on its rural surroundings, but Jews could not settle anywhere outside the gate. They had to buy their food and earn money by negotiating their needs with the surrounding Christian population.

As everyone knows, windows are not used only for looking out. They also serve for looking in. Let's drop in for a short visit to the house. The first thing we notice is that the sunlight streams in, first encountering the polished cupboard that stretched half the length of the wall. This cupboard was built by Yoysef (Tesi's son), a local carpenter. These days, such a fine piece of work would be considered a treasure, a real work of art. Yoysef spent long days planing and smoothing out the wood, until the surface was as lustrous as silk; then he lacquered and polished it with chopped walnuts tied up in cloth.[5] He decorated the door with thin strips of veneer. Finally, he crowned the cupboard with an elegant, delicately worked head–tefillin.[6] The subdued sheen gleamed in the sunlight like polished glass. Oh, Yosl![7] You gave so much joy to the children you allowed into your workshop to watch you work. They marvelled at the shavings, spinning out from under the plane as though they were alive, and snatched them up by the handful; the movement and rhythm of the saw cutting the boards was a source of wonder to them.

In addition to the cupboard made by Yosl, the room also contained a large rectangular table with bulbous, carved legs. The table was surrounded by the inevitable “Vienna” chairs with woven cane seats.[8] The wall was decorated with two large photographs of Grandfather and

[Page 102]

Grandmother. The original photographs were originally made by Yehoshua Photographer.[9] Uncle Shloyme asked for them to be sent to America; they came back to us enlarged and colored.[10] The wall clock hung between the pictures. This was a large–faced modern clock, powered by a spring that had to be key–wound every 24 hours. This was an innovation, compared to the heavy pendulum in most contemporary wall clocks. Incidentally, I was never able to discover the age of the clock, or how long it had occupied its important place in our house. In any case, it had certainly happened before I first opened my eyes and took a first look at the world I had entered. The clock was surely showing the hours and minutes accurately, but who would be interested in noticing that? It was probably doing the same thing and showing the hour and minute when I left the house, never to see it again. And once again, no one paid attention… Only the clock itself knew, ticking away the flying time and ringing out the hour, day or night.

So life flowed comfortably and happily–but only for a few years. The clock chimed the hours of Friday evenings.[11] In summer, soon after the festive meal, everyone would go out into the street. Women would sit on the earthen benches adjoining the house walls and discuss the quality of this week's challahs, the high price of the fish for Shabbes, and the like. Young men went for walks with their wives. Children, of course, would be outdoors. In winter, more people went out on Shabbes evening; most people stayed home on Friday nights. Later in the evening on clear moonlit nights, when the Shabbes candles had gone out and the kerosene lamp's wick had run out of fuel, the moon would appear from somewhere and send an exploring ray of light into the house.

The house is quiet. The household members, sitting in the lively darkness with neighbors and friends, have exhausted their conversation and remained seated around the warm central stove, each immersed in thoughts. Now the moon sends a stream of light into the room, driving the darkness out of the corners, throwing a veil of light over everything; minutes later, its round face is looking through the windows. It sees itself mirrored in the polished brass candlesticks on the table, and smiles teasingly at Queen Shabbes, who is visiting here until tomorrow evening and shakes people up a bit.[12] The conversation starts up again. Arye Shenkelman starts singing a psalm to a traditional tune, more and more devoutly, and the

[Page 103]

long hours of the winter night drag on. No one notices that the moon has disappeared, and is hiding behind the tip of the synagogue roof. A trumpet call slices the air, reverberating from somewhere far away, sharp and oddly sorrowful. It suddenly stops, starting again sporadically until it goes completely silent. The watchman at Divishek's factory down in the valley is letting people know that he is awake, and that the hour is late. The trumpet's call has broken the idyll of absolute peace. People wake up, each grab their fur coats and caps, and go out into the cold street. Each person went to his own corner. The cold plucked at people's faces, bringing them wide awake. The nighttime streets lie frozen under the untouched virgin snow. House roofs and tree branches are robed in white, standing asleep as though by a magic spell. Wrapped in dark shadows, the houses leaned against each other. A thin thread of smoke emerged from a chimney somewhere, and stretched straight up to heaven. A glowing ember had breathed out its last bit of fire; or a witch had cooked up her broth.

In the houses, all the windows are dark, not a glimmer of light to be seen. Everything is asleep. Only the startled barking of a dog comes from somewhere. It barks desolately and is soon silent. A stride, a creak. Feet rise up on their own, boldly. I'd love to stride like this to the end of the world… The alleys are now so peaceful and quiet, “how blessed are your tents, Jacob.”[13] Sleep, you familiar, kind people. I'd like to remember you as existing under the reign of Queen Shabbes, and no other regime…

Translator's Footnotes:

by Yitzchak Frenkel[1]

Translated by Yael Chaver

Zinkov stood firmly on the top of a tall hill and was a major center for the Jews throughout the province of Podolia, Ukraine. There were very few non–Jews in town: the judge, the doctor, the medic, the post–office manager, and a small number of hospital workers. The chief of police, his constable, and the police officers they commanded lived out of town.

|

|

| Yitzchak Frenkel |

The hill where Zinkov stood is surrounded by a valley dotted with Ukrainian villages. The Ushytsia River flows gently through the villages; on its way to join the Dniester, its waters power grain mills, usually standing in pairs on either side of the river. The river section that flows through a village is often named for that village: the Kalinovka River, the Krivuli River, and the Men's River, so named for its deep water, suitable for “masculine” swimming. On hot summer days, all the Jews of Zinkov – old and young – would go down to the river to wash off their sweat in the Kalinovka River east of the mill, where the water was shallow. The young folks would go to swim in the deep water of Men's River. On their way to the river and back, the bathers would pluck juicy fruit off the branches overhanging orchard fences.

[Page 105]

No trained engineers had planned the streets and houses of Zinkov, yet the main streets of the town were straight, and the houses on either side were tall and wide, the whitewashed walls gleaming brightly in the sun. The two main streets crossed at a wide square, with a high pole bearing a bright “Lux” kerosene lantern. This was the town center. The Jews of Zinkov would gather on the square in their free time and talk about their livelihoods, town affairs, and the reports in the newspapers. They talked about ordinary matters: whose son or daughter was getting married, a bris or bar–mitzvah in the family; the quality of the cantor's chanting on recent holidays; who was granted which blessing before a Torah reading last Shabbes or holiday; the number of followers who came from towns near and far to the “courts” of Rebbe Moyshele or Rebbe Pinchesl (may their memory be for a blessing) and the gifts they brought.[2]

|

|

|||

| Nekha Frenkel (may her memory be for a blessing) |

Aharon Frenkel (may his memory be for a blessing) |

Other topics of conversation were about the best places to walk on summer evenings and on Shabbes (behind the Christian cemetery (the tsvinter) or behind the city hall; about who needed the services of the court because of a debt or a quarrel; etc.[3]

The Jews of Zinkov made their living in various ways: leasing forests or flour mills, as lumber merchants, trading in flour (both wholesale and retail), fabric, groceries, and notions. There were owners of taverns and hotels, bakers, dealers in medicines, pharmacy owners, teachers, and various artisans. These were the “householders,” the most important men in town, and constituted most of Zinkov's residents. They lived in the homes they owned on the town's streets and squares. The lower street was the home of the poor: patchers of fur garments and shoes; millers; tailors making clothes for peasants, synagogue sextons, the indigents, and the town's gravedigger.

My father, Aharon Frenkel, came to Zinkov in 1898 from his home town of Michalpole, where he was born to his father Yoyne

[Page 106]

and his mother Toyve; in Zinkov, he married my mother Nekha, the daughter of Henekh and Khaye Gornshteyn (may their memories be for a blessing). Father was proud of being Jewish. He was learned, loved to read, and was sociable. He was generous, and always gave freely to the poor of the town and indeed, to anyone in need. He loved young people who were interested in knowledge and culture, advised the municipal library about book acquisitions and even contributed money for this purpose. The local theater troupe took his advice concerning choice of works and performance style. He was a regular at the small synagogue, and donated generously to its maintenance. He would take his seat at the prestigious east wall of the synagogue and participate in choosing the readers for the aliyahs; he would buy the most important aliyah for himself.[4] If there were disputes between grantors of aid and its receivers who did not repay the aid, or between storekeepers about attracting customers, or other financial disputes, the two sides would turn to Father and lay out their arguments. His opinion would be accepted as a judgment, with which both sides were satisfied.[5] Father devoted most of his energy to educating his children. He made sure the children did their homework; he would first help them, then quiz them. Mother was his assistant. He made a living by managing two grain mills on the banks of the Kalinovka, which he leased from the authorities. Each mill employed 10–12 workers.

The Jews of Zinkov lived peacefully. It was not hard to earn a living, and their living conditions were good. The children were healthy and happy; their clothes and shoes were clean and intact. On Shabbes and holidays, their homes were happy and contented. On summer Saturdays, after the Shabbes meal and a nap, each family would go for a walk outside the town limits for fresh air, beyond the non–Jewish cemetery and the vlost, to the square surrounding the old fort (the shloss). The hikers would reach the nearby villages and strike up conversations with peasant acquaintances resting on their fences. These peasants often gave them gifts from their farms – flowers, apples, plums, sunflowers.[6] Relations with the villagers were normal. Things changed with the outbreak of the first World War, in the late summer of 1914. Not all Jewish men of draft age were in a hurry to enlist for the defense of their “step–homeland,” with good reason.[7] Searches for conscripts in Zinkov became common and kept people on edge day and night. The members of the Jewish community council were constantly negotiating with the Chief of Police and the constable, asking them to stop the searches or at least give advance notice… During the first years of the war the food supply was still steady, and trade continued as usual. At the end of 1916 a lack of kerosene, salt, and fabric began to be marked. As a result, tensions with the peasants began to rise. They falsely accused the Zinkov Jews of hiding goods. Discontent and signs of coming revolution were noticeable in Zinkov as well.

[Page 107]

At the first news of the 1917 February Revolution, the Zinkov Chief of Police and the constable vanished, as well as all the policemen.[8] The town was left with no authorities. The city council decided to organize self–defense, without consulting with the public. Most of the townspeople, however, thought that it was too early to take such an independent step, because they were not sure that the revolution was stable; the deposed government might return, God forbid, and such a hasty step would bring disaster upon the town. However, one night we heard knocking at the door. The Chief of Police came in with his Chief Constable, proposing that Father keep their swords and the few firearms they had, until the unrest died down. This great deed would work in the Jews' favor, when the old regime eventually returned. Father sent me to call for the advocate Abstryanik, Gusakov the dentist, Motya Fayerman, and few young men. After a brief consultation, they decided to take the weapons, hand them out to the young folks, and set Father at their head. The Jews of Zinkov could not believe their eyes the next morning: Jews carrying police swords were out on the street for the first time in Jewish history, with all its calamities and humiliations.

The Zionist ideal and the longing for the historic homeland of our people, which Father had suppressed for many years for fear of the authorities (who opposed any movement of national liberation), now burst forth. Zionism became popular in our town, Zionist education was carried out in the synagogues, the schools, and the streets, and captivated the Zinkov natives.

|

|

| Zinkov natives building a road in Rishon Le–Zion: 1. Yitzchak Frenkel 2. Reuven Rozental 3. Netanel Frenkel |

[Page 108]

When the members of the Regional Zionist Committee came to Zinkov to collect contributions for Eretz–Yisra'el, the ground was ready: women and men of the town donated jewelry, wedding rings, and gold watches. Father and Mother, of course, were among the first to donate. The young people started to organize in a HeHalutz group.[9] In order to finance their activities, they chopped wood for school stoves. Father, may his memory be for a blessing, was at the forefront of the young people, fanning their enthusiasm and desire to immigrate to Eretz–Yisra'el.

The October revolution, which swept through all of Russia, led to an extreme nationalist counter–revolution throughout Ukraine.[10] Jewish life and property became free for the taking. Ukrainian armed bands stole, robbed, and killed indiscriminately. Two days after the Proskurov pogrom, Petlyura's forces murdered most of the Jews of Felstin.[11] Representatives of the Jewish community came to Zinkov for help burying the dead and caring for the wounded. Their community distress deeply affected the town's Jews . Father, along with the other council members, organized a delegation of ten young men and two young women; one of the women was a newly certified physician, the other a pharmacist. I was one of the members of the group. We braved the dangers of travel through villages with their gangs seeking to murder Jews, en route to help our brothers and sisters in Felstin. It became imperative to organize self–defense in our town. The best and finest, as well as the young people headed by Nokhem Yoshpe, answered the call; Nokhem describes this project in detail elsewhere in this volume.

The Jews of Zinkov lived under the protection of this “Defense” force for about two years, cut off from the center of the country,

|

|

1) Dovid Fuks 2) Zevulun Rund (not a Zinkov native) 3) Shloyme Goldenberg 4) Unknown 5) Nissan, from Husyatin 6) Zev Nesis (may his memory be for a blessing) 7–9) Unknown 10) Mandel 11) Menachem Vaysman 12) Shmuel Korn 13–14) Unknown 15) Shamai Shor |

[Page 109]

with no reliable news of events. They were also cut off from supplies; there was a severe shortage of kerosene, salt, sugar, and other staples. The value of money dropped; whatever supplies were available disappeared and could be acquired only on the black market in return for grain, or silver and gold coins. Our skies were darkened; there was almost no way to survive. Once again, my father sounded the alarm: Brothers, don't wait for the empty fleshpot to refill itself. Let's leave while we are still alive, and go to Eretz–Yisra'el.

And indeed, a pioneering Zionist movement developed in our town; it overcame all the external obstacles and problems, as recounted by the first pioneer, Nokhem Yoshpe, in his detailed account. Groups of pioneers from Zinkov arrived in Eretz–Yisra'el. Their adjustment to the country was extremely difficult, as was their adaptation to the hard labor of road–building; and even more so – to the unemployment that followed. They could barely subsist until the next job came along. We shared all our experiences with Father, in letters to him. We concealed nothing. All the descriptions of our difficulties did not deter him. In 1923, he arrived in Eretz–Yisra'el with my brother Yekhi'el, and a year later Mother arrived with the remaining four children. They set out with youthful energy to build their new home in the age–old homeland. Father leased 10 dunams of land from the Jewish National Fund, bought a horse and a plow, and started to plant tobacco, assisted by his children.[12] Mother contributed by caring for the modest cabin on the outskirts of Rishon Le–Tziyon, in which the family lived. Over the years, the sons and daughters married, and all settled down in Eretz–Yisra'el. The children helped their parents buy the land on which their home was built. Father planted fruit trees, bought cows, and made a respectable living through his own efforts. All the sons and daughters would gather at the parents' cabin on holidays and celebrate. Father's yearning for the homeland and his lifelong goal was fulfilled. Father died at age 72; Mother lived for 14 more years. May their memory be blessed forever!

Below is the list of pioneers from Zinkov:

The first group included:

Translator's Footnotes:

by Moyshe Garber

Translated by Yael Chaver

Oh, God! Inspire my imagination and strengthen my pen, so that I can use all my might to revive you, my very dear former home and all of you, my dearly beloved sacred martyrs. I, too, would like to add a few bricks to this memorial monument; bricks mixed and molded with blood from my heart and tears from my eyes.

I was not intimate with my town, Zinkov, from 1921 to its destruction. I don't know how people lived there under Soviet rule, whether better or worse, and will not dare to judge; I have no memories and no impressions of that period. But I remember very well Zinkov and its residents during my early childhood, up to the day I left my town, at the end of 1920. Oh, I remember it very well. It is deeply engraved in my memory, in my heart, and in every part of my body.

Often, when I am alone, my heart yearns nostalgically so that I become detached from the reality around me. I shut my eyes and fall into a kind of trance. I let my thoughts carry me back many years, to my distant, impoverished, beloved town, where I was born, where my cradle stood, where Mother and Father trembled as they watched over me, and where I lived through so much joy and suffering together with my family, my friends, and my neighbors. As though through a thick fog, it all comes nearer and nearer, until I see everything so clearly that I can almost touch it. I see the houses, the streets, the alleys, the paths and trails in the fields and hills, where I ran around as a child, and played with my friends. As though on a movie screen, I see the images, the people, and the events that are still so dear to me.

Here is my own home, on the Taravitza, near the field, where I was born and lived until the day I left,

[Page 112]

never to set eyes on it again.[1] No one was out in that cold, dark winter night before we went away, to see me standing outside leaning against the wall, parting from my home and weeping bitterly. I see all the neighbors who lived with us in the same house, such as my uncle Yehoshua Sender's son (Shaye Fotografshchik).[2] Others who lived in the house were Efroyim (Batchke's son) and his father–in–law, the snub–nosed synagogue caretaker, who would call everyone into the synagogue for prayers. Next were the houses of Hersh Foydnik, Shmuel Stolier, Mordkhe Boykes, Shmuel Mishandzenik, Yisro'el Shnayder, Tsalay (Leybl's son), Itzi–Meir Khmelenker, Ben–Tziyon (Shaye's son), Yankl Haritan, and many more.

|

|

|||

| Shmuel–Lipe (son of Sender) Garber and his wife Rokhl (may their memory be for a blessing), the parents of Moyshe Garber | ||||

I see my kheyder, with my kind melamed Sani (may be rest in peace); right next to it is the talmud–toyre, on the butcher's meadow; the house of Mendel the shoykhet, the teachers Bronfman, Koyfman, Kretshmar, Osher Altman, and others.[3] It was in the talmud–toyre that I spent my happiest and best childhood years. That is where my solid foundation of knowledge and learning was laid, the basis for my later cultural education and development. I felt boundless love for my beautiful natural surroundings. When the grain in the field grew tall and ripe, waving like a golden sea, I loved to walk along the narrow path to the Libak valley. Cut off from the world, I would stretch out on the soft, fragrant grass, my face upturned to the clear blue sky, and ruminate, dreaming the golden dreams of youth, and marvel at the beauty of God's world. Oh, how good it was then to be young and free of worry!

[Page 113]

I remember the hot Shabbes days of summer. After morning prayers, we would eat a good midday meal, with cholent and a fatty kugel.[4] The older folks lay down for a nap, and we youngsters were off to the fields and woods, through hills and dales. Once we were tired and sweaty enough, we'd climb up the cramped, narrow path along the old Turkish fort, then let ourselves down to the spring. We'd quench our thirst with the ice–cold, crystal–clear water that flowed down a stone channel. Once we were refreshed, we sat in the shadow of the willows, among the lively rivulets of water. We stuffed our pockets full of putr–krayt (a type of bluish stone we used for carving toys).[5] Afterwards everyone felt like taking a swim. The river was not far away; we headed over there, or to the Grebleye, or the Men's River.[6] Oh, how I envied those who could swim across the river. In my child's eyes, they were more heroic than those who swim across the English Channel today.

And do you remember, dear Zinkov natives, the Shabbes twilight hours, when young and old, dressed in their best clothes, would stroll calmly across the green hills below the fort, below the non–Jewish cemetery, or simply along the fields, all the way to the black cross and back? We gulped in the refreshing air. and feasted our eyes on the beautiful sunset and the beautiful panorama of the valley with the curving river bordered by colorful cottages, orchards, and gardens.

Once again, the amazing images pass before my eyes. They rush one after the other, in no special order: the massive building – our famous synagogue, which I always viewed with so much wonder; it was constantly a mysterious riddle. I really wanted to know how a small poor town such as ours came to have such a gigantic, imposing structure, such an architectural masterpiece; who the artists were, who carved the beautiful Torah ark that defies description, the likes of which I have never seen since. After all, who were the builders and creators of such an expensive project? I never received a satisfactory answer. I'm sure that no one knew.

The image of the market, with its stores, stalls, and sellers, emerges from the farthest reaches of my memory. The non–Jewish women are set up with their wares –

[Page 114]

fruit and vegetables. The Jewish women selling in the market sit further along with their baked goods. At the side is a long row of the earthenware pots for which Zinkov is renowned. The most prominent buildings in Zinkov are the brick house of Yosl (Shaye's son), and Khayim Kliger's oversized building, surrounded by stores. Close by, I can see the rounded well near Shloyme Shor and Sore Yosi Mekhtsis. The well, which had cost a fortune to dig, never produced water.

|

|

|||

| Itzik Hersh Volfbayn's wife (may her memory be for a blessing) |

Itzik Hirsh Volfbayn (may his memory be for a blessing) |

I see it all before my eyes again. I see the patches of deep mud and the cold, dark, winter days and nights. Most of the population lived in dire poverty, need, and hopelessness, but I do not want to think about that too long. I want to remember that which was beautiful, good, and beloved; that which is so closely linked with my romantic, dreamy youth. I seem to hear the whistle of Divishek's brewery, which woke the workers at 6 a.m. The Divishek name and its beer added to the popularity of our Zinkov. Not far from the brewery were the tanneries, with their pungent smell of kvass,[7] in which the pelts were soaked; these pelts were later made into fur jackets for peasants, and used for leather. And here, at the foot of the hill, is the bathhouse. It played an important role in the life of the Zinkovites. That is where the poor washed every Friday, and refreshed their exhausted bodies in the steam bath. Scary voices would scream down from the top bench, “Podovoy paru!” (“More steam!”).[8]

[Page 115]

Dear fellow Zinkovites, you certainly remember the fire brigade (pozharne komande), with their gray uniforms and shiny brass helmets. You remember how they would go out and train with all their gear, climb onto roofs and spray water from their “pumps.” But they could never actually extinguish a fire, because there was a serious shortage of water; water had to be brought up a long way from the foot of the hill. The brigade's center was called “the fire brigade's depot.” Its upper floor consisted of a hall where weddings would be held, visiting theater troupes would have performances, and even we young amateurs would play there, and bring some light and joy into the quiet, monotonous life of the Zinkovites.

Suddenly, the day came which spelled the end of the quiet, peaceful, impoverished life of Zinkov, and of the normal life of the whole world. That was the day when the First World War was declared. The bloodbath and widespread slaughter lasted for two years, before Russia reached the abyss of complete breakup. At that point the democratic Kerensky revolution broke out, putting an end to the Czar and his rotten, incompetent clique, and we breathed more freely and happily, participated in demonstrations, and held inspiring talks. But the Kerensky regime was weak and did not know how to establish and consolidate its power. It continued the futile, senseless war, until the Bolsheviks came and promised a speedy end to it. This had a powerful effect on the weary people, and even more so – on the hungry, bloodied armies, who were rotting in the trenches. In this way, the Bolsheviks, headed by Lenin and Trotsky, rose to power. The internal and external counter–revolutionary forces did not surrender easily, and made repeated attempts to regain power. Denikin, Kolchak, Petlyura, the Poles, and more and more armed bands succeeded each other.[9] Jewish blood and Jewish property became free for the taking. We lived in constant fear of death and terror, lying in cellars and attics like terrified shackled sheep, waiting for the slaughter. The armed bands rampaged, robbed, murdered, and raped Jewish women. Death was hard, but life was even harder. Hunger and typhus finished off the rest.

The devilish dance finally slacked off a bit. Anyone who had the chance ran off, as panicked animals flee from ravenous flames. We ran, and ran again, to all the corners of the world: to America,

[Page 116]

Canada, Argentina, Eretz–yisro'el, and wherever possible.

But when the terrible plague of Hitler came, our unfortunate brothers and sisters could run no more, because the blood–drenched enemy was persistent, strong, and merciless. With real German precision, it completely and forever destroyed our Zinkov, its people, and its life.

Now we survivors of Zinkov, call ourselves landslayt; the word landsman overflows with love, intimacy, and brotherly feelings.[10] We are organized in societies and associations bearing the name of Zinkov, of Zinkovites, of Zinkov life. Even when our inevitable end comes, Zinkov natives find their eternal rest in the cemetery that is Zinkov soil; over its entrance is the inscription “Zinkov – Podolia” in large Yiddish letters. God rescued us from the hellish fire, and it is our destiny to continue the existence of Zinkov and of the Jewish people. This we do, and will continue to do, with love and devotion, to our last breaths.

Translator's Footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zinkiv, Ukraine

Zinkiv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 15 Sep 2020 by JH