[Page 25]

The Geographic Situation of Zinkov

and its Public Life

[Page 26]

Translated by Aryeh Sklar

|

|

| [Translator's note: Hand–drawn map of Zinkov and its immediate surroundings]

Legend [translated from Hebrew]

1 – Gas streetlights

2 – Well

3 – Manual pumps

4 – Public park

5 – Fire brigade

6 – Slaughterhouse

7 – Talmud Toyre

8 – Court of the admor Pinchesl[1]

9 – Old–age home (hekdesh)[2]

10 – Pharmacy

11 – Zemstvi hospital[3]

12 – Dr. Gorbatovski

13 – Christian cemetery

14 – Cemetery

15 – Graves of admors

16 – Great synagogue

17 – Bes Medresh[4]

18 – The old kloyz[5]

19 – Court of the admor Moyshele

20 – Alter Katzenelbogen's kloyz

21 – Artisans' synagogue

22 – The house of Yaakov–Moyshe and the hachshara garden[6]

23 – Domestic animal market (torhobitse)[7]

24 – Pork market

25 – Stalls selling bread and fruit

26 – Hatters

27 – Potters…[8]

28 – Commercial center

29 – Butchers' alley

30 – Yosl Shayes

31 – Markovsky house (history)[9]

32 – Public toilets

33 – Post office

34 – Ruins of fortress (the schloss)[10]

35 – Courthouse

36 – School (uchilishtsa)[11]

37 – Bistitske[12]

38 – The vlost/vlust[13]

39 – Jail

40 – Police station

41 – Notary

42 – Moyshele the folk–healer[14]

43 – Yechiel the folk–healer

44 – Shmuel the folk–healer

45 – Azi Zecherman (the office)[15]

Note: the ubshivka (slum)

[Translator's note: The map includes Hebrew notations that indicate roads leading to/from other locations, as well as geographical features; they are listed in counter–clockwise order, starting at the Legend.]

Center right: To Vinkivtsy

Center top:

– Arrow indicating N.

– To Derazhnya and Proskurov

– Area of Saturday walks

Center left:

– To Adamovka and Yarmolintsy

– Area of Saturday walks

– To Kalinovka, Solovkovets, Kamenets[16]

Bottom right:

– krevuly[17]

– Wells

– The yar[18]

– The path

– Area of Saturday walks |

Translator's footnotes:

- Admor is the honorific title for the leader of a Hasidic group. The admor receives his followers in his “court.” Return

- Hekdesh signifies a service supported by the community. Return

- The Russian zemstvo indicates “government”; this may have been a government–run hospital Return

- The bes medresh (House of Study) is a voluntary, public institute for Torah learning, functioning for generations within Jewish communities alongside the synagogue. Return

- Kloyz is a term for a smaller synagogue. Return

- Hachshara is the Hebrew term is used for training programs and agricultural centers in Europe and elsewhere. At these centers Zionist youth would learn technical skills necessary for their emigration to Palestine/Israel and subsequent life as members of kibbutzim (communal settlements). Return

- Torhobitse is the Ukrainian term for animal market. Return

- The ellipsis is in the original text. Return

- The reference to “history” is unclear. Return

- The use of the German schloss is not explained. Return

- Uchilishtsa is the Ukrainian term for ‘school.’ Return

- I could not translate this non–Yiddish term. Return

- I could not translate this non–Yiddish term. Return

- The hebraic term rofeh is usually used for a folk healer. An accredited medical physician is usually termed dokter. Return

- It is not clear what this refers to. Return

- I could not identify the town of Solovkovetz Return

- I could not translate krevuly Return

- Ukrainian yar means “ravine”. Return

[Page 27]

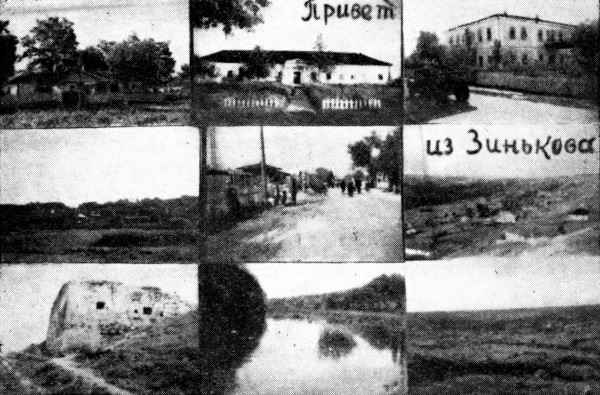

The Town of Zinkov

A Geographical–Historical Survey

by Chana

Translated by Aryeh Sklar

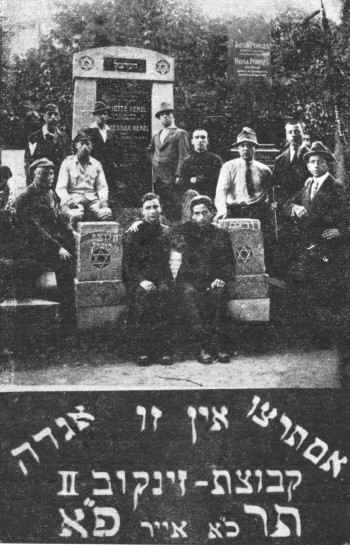

Zinkov is a town in the Letichev district, in the province of Podolia. We have no clear and precise information regarding when the city was founded. There are remains of an ancient fortress there, and tradition has it that it is an [archeological] witness to the times of Turkish rule in that region in the years 1672–1699, which went as far as Kamenets–Podolski, which is near Zinkov. Based on this, one can surmise that the town of Zinkov existed for 300 years before its destruction by the Nazis.

Zinkov is situated a distance of 60 parasangs from Kamenets–Podolski, and a distance of 40 parasangs from Proskurov. It sprawls over a wide hill which encompasses meadows and valleys, and at the foot of it passes the River Ushitsa, which intersects with the Dniester.

The soil of the area is the fertile black earth of Ukraine, and its fields grow rich crops. There are 13 villages surrounding Zinkov, its inhabitants farmers of small fields. Nearby are great plots of land belonging to Polish owners, who built factories for sugar, paper, and beer.

Zinkov's populace was entirely Jewish, with the exception of a small number of Ukrainians and Russians. In 1847, the population of Jewish inhabitants was 2150. In 1897, according to the official census which took place that year, there were 3719 Jews, and in the 1920s and 1930s, there were an estimated 5000 people.

The Jews of Zinkov, for the most part, made their livings among one another, even standing up to the economic revolution with the landowners in neighboring areas. They mostly dealt with wheat and fruits, which Ukraine was blessed with, and they supplied bread and fruit tree products to the world at large. There were also honeycomb sellers and those who leased out flour mills.

There were no especially wealthy people in the town, but there were many average, working–class people, making a living however they could. There were also unemployed, who lived hard and meager lives.

Judaism in Ukraine, especially in Podolia, was not exceptional in its erudition and academics, yet the people were also far from boorishness and ignorance. Every Jew, regardless of wealth, taught their children Torah. Study began in children's classrooms (heder), or in a “Talmud Torah” [traditional school], and culminated with the study of the Talmud. There were some special individuals in Zinkov who studied Torah when they were free from their jobs. Among the teachers of Torah were Torah scholars,

[Page 28]

well–versed in Torah. 7 study halls and “kloyzim” existed in the town, within which they would study at night the Mishna and Ein Yaakov (Legends of the Talmud).

Once the Enlightenment movement (Haskala) started to make inroads in Russian Jewry, it came to Zinkov as well. Parents began to send their children to learn general studies in Russian schools that [taught] both areas [of study], which were operating nearby. Already at the start of the 20th century, many sought a high school education, and young students with those aspirations left to the bigger cities.

From the start of the emergence of political Zionism, the Zionist idea spread throughout Zinkov as well, and many parents educated their sons and daughters in the spirit of this movement, arousing in them a love for the land of Israel. This caused, after some time, a youth pioneer movement, with many from Zinkov immigrating to Israel to work and participate in building it up.

The [General Jewish Labour] “Bund” movement also gained members and supporters in Zinkov, even though the working–class Jews were, to put it mildly, not relevant [to the movement]. They were not in the factories of production, nor did they have the background of the political debates. But a feeling of rebellion was stirred in those workers against their masters [to sympathize].

|

|

R. Moyshele,

May the righteous' memory be a blessing |

Zinkov was close to the cradle of Hasidut, that of Medzibush, which continued the Hasidic dynasty of Apt. Jewish holidays allowed for their spirit to be felt in the area, for they would come from all the surrounding areas, to sing Hasidic melodies. In particular, there was tremendous enthusiasm with song and dance during the festival of Simhat Torah. The court of the Rebbes were always open for anyone seeking counsel, for anyone down–

[Page 29]

trodden. There they would lead passionate public prayer, there they would judge cases of Torah law, filled with truth, justice, and righteousness.

Among the personalities, a few noteworthy individuals should be mentioned:

Rabbi Moshe Barsuk, may his memory be a blessing, secretary of the [Hasidic] Rebbe Rabbi Moyshele, may the righteous' memory be a blessing – or, as he was called then, “the Gabbai” [the sexton]. He was an exceptionally studious man, and the sacred teachings never ceased from his mouth, day or night. He would trade questions and answers of Jewish law with many famous rabbis from the surrounding areas, and he recorded his notes in the margins of his Talmud that he was studying.

Rabbi Mordechai Nachmanes, an exceptional teacher of Talmud – [he was] studious, wise, and an extremist.

Rabbi Chaim Ravizes, may God avenge his blood, a popular and engaging Jew, good–hearted, studious, noted for his collection of stories and especially his sayings, which were abundant with folk wisdom. One of them was: “As bad as it gets in this world, be happy you're not dead where it's worse. Az es iz nit gut aoyf der velt, zal men zikh aoyf yener velt nit veyzn.” “Ikh farshtey – areyngeyn lebedikerheyt in himl vi alihu ader eyngezunken vern in der erd vi krkh, aber nit bleybn heyngen vi abshlum tsvishn himl aun erd – I understand going to heaven like Elijah, or being swallowed up by the earth like Korah, but not Absalom, remaining between heaven and earth.” He was murdered by soldiers of Hitler, may his name be erased. His son, Yitzhak Isaacson, may he rest in peace, was a scribe; he died after a short time in Argentina.

Mordechai Vartzman, an honorable man, with a large and illustrious family, a “Shlomo Nagid”–type.

Herschel Moshe Hayses, with his wife, a “woman of valor,” Rachel. [Rachel] selflessly managed their large family, giving her husband the ability preoccupy himself with Torah.

After the pogroms perpetrated by [Symon] Petliura's men [as part of the Ukrainian People's Republic], and after the massive pogroms in Proskuriv and in Felestyn, places close to Zinkov, many young people abandoned Zinkov, which was close to eastern Galicia, and they were able to cross the border. Some immigrated [to Israel] as pioneers, and others settled in America, and some time later their parents followed them.

[Page 30]

Zinkov, Our Town

(A Historical–Geographical Survey)

by Chana

Translated by Yael Chaver

Zinkov is a town in the Letychiv district, Podolia province.

We have no clear, accurate information about the time it was founded. There are remnants of an old fort in the town, known as “the castle”; and, as passed down the generations, it is evidence of the Turkish occupation of the region, in 1672–1699; Turkish rule extended as far as the nearby city of Kamenetz–Podolsk. Thus, Zinkov apparently existed for about 300 years before it was destroyed by the Nazis.

Zinkov is 60 versts[1] from Kamenetz–Podolsk, and 40 versts from Proskurow. It lies across a broad hill, and is surrounded by valleys and meadows. The Ushitsa River flows at its foot, en route to the Dniester. The soil in the region is the blessed black soil of Ukraine, and the choicest crops flourish and ripen in its fields.[2]

Thirteen villages lie around Zinkov, inhabited at that time by peasants. There were large estates nearby, owned by Polish nobles. Adjoining these estates were factories that produced sugar and paper, as well as breweries.

All the town's inhabitants were Jews, with only a few Ukrainians and Russians. In 1847 the Jewish population of Zinkov numbered 2150. In 1897, when the official census was carried out, the population of Zinkov numbered 3719. During the 1920s and 1930s, it rose to 5000.

The Jews of Zinkov made their living, for the most part, by trading with each other. Until the revolution, they had trading connections with the landowners of the region as well. They were mostly occupied with trading in

[Page 31]

grain and fruit, with which Ukraine is blessed. They exported bread and various fruits all over the world. The residents included lumber merchants and mill leasers. No one in the town was very rich; but there were many average householders and craftsmen, who lived by their trade. There was also no shortage of people who had no occupation and lived in want and poverty.

The Jews of Ukraine – especially in Podolia – were not famous for their education and scholarship, but the Jews of Zinkov were far from ignorant and uncultured. Every Jew, whether rich or poor, sent his child to study Torah, starting with the Talmud–Toyre and ending with Talmud study.

There were also a few in town who spent their free time studying. The local teachers included some scholars and experts. The town numbered seven bes–medresh institutions and small synagogues, where people studied Mishna and Ein Ya'akov in the evenings.[3]

When the Enlightenment movement expanded among Russian Jews, Zinkov was included. Parents started sending their children to secular schools, sending them increasingly to middle schools as well. The young people of Zinkov were attracted to large cities for this reason.

[Page 32]

Once political Zionism began, that idea became popular in Zinkov as well.

Many parents raised their children in this spirit, and awakened a love of Eretz–Yisra'el in them. Eventually, a Zionist youth movement was established in the town, and young people of Zinkov immigrated to Palestine, worked there, and participated in the development of a Zionist community.

The Bund also started a youth movement in town, which attracted many members and sympathizers, although there was no Jewish proletariat in the full sense of the word, as there were no factories. Thus, there were no grounds for class warfare.[4] However, manual workers developed a sense of protest against their bosses.

Geographically, Zinkov was close to Medzhybizh, the cradle of Hasidism, and carried on the chain of Hasidic tradition.[5]

The Jewish holidays would imbue the town with spirituality. The Hasidim, who would gather from all over the region, would sing their melodies. The major musical event was at Simkhas–Toyre, accompanied by an ecstatic Hasidic dance. The courts of the rabbis were always open to all, anyone who was depressed or sought advice. People would pray whole–heartedly with the congregation. Rabbinical legal cases were heard there, inspired by truth, justice, and decency.

The following personalities, which distinguished Zinkov, included the following:

Rabbi Moyshe Barsuk (may his memory be for a blessing), secretary to Rabbi Moyshele (may his righteous memory be for a blessing), was usually called “the manager.” He was an extraordinary scholar, and was constantly studying. He would exchange learned opinions with famous rabbis in the region, and would note his comments in the margins of Talmud volumes as he studied.[6]

Rabbi Mordkhe (Nachmen's son) (may his memory be for a blessing) was one of the best melameds in Zinkov. He was smart, pious and a scholar.

Rabbi Yankev Altanir (may his memory be for a blessing) was a typical scholar, modest, and unassuming.

Rabbi Khayim Royzis (may God avenge his blood) was a pithy, kind, decent person, as well as a scholar.[7] He was known for his tales, and especially for his proverbs, which were suffused with folk wisdom, such as, “If life here is not good, don't show up in the next world,” and “I understand ascending to heaven while alive, like the prophet Elijah, or sinking into the ground like Korach, but not hanging between heaven and earth, like Absalom.”[8] He was murdered by Hitler's monsters,

[Page 33]

may their names be blotted out.*[9] His son, Yitzchok Itzikzon (may be rest in peace) was a writer. He died in Argentina not long ago.**[10]

Mordkhe Vertsman (may his memory be for a blessing). He was an outstanding person, the father of a large, honorable family, a Shloyme Nogid.[11]

Hershl (Moyshe Khayim's son) (may his memory be for a blessing) and his wife, the “woman of valor” Rokhl, who supported the family by her work and enabled her husband to devote his entire life to study.[12]

After the pogroms carried out by the Petlyurists, especially the major pogroms of Proskurow and Felstin (near Zinkov), many young people crossed the nearby border to eastern Galitzia. Some continued on to Eretz–Yisra'el and others emigrated to America; they were eventually followed by their parents.

(Translated from Hebrew)

[Page 34]

|

|

Remnant of the Turkish fort, and the path to the spring.[13]

“The Castle,” remnant of a Turkish fort, and the path to the spring.[14] |

Translator's footnotes:

- Versts (also called parsings) is an obsolete Russian unit of measurement equal to 0.663 miles (3,500 feet) or 1.067 km. Return

- “Black soil” is a literal translation of the Russian term for this type of soil (Russian chernozem), which is a fertile black soil typical of temperate grasslands such as the Russian steppes and the American prairies. Return

- Ein Ya'akov is a very popular 16th–century compilation, by Jacob ben–Habib, of all the Aggadic material in the Talmud together with commentaries. It is still in print. Return

- Inevitable class war between proletarian factory workers and capitalist factory owners was an important part of Marxist thought. Return

- Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760), the founder of Hasidism, lived in Medzhybizh from about 1742 until his death. His grave is still pointed out in the old Jewish cemetery. Return

- Such exchanges of opinions, known as Responsa, form a body of written decisions and rulings given by Jewish legal scholars in response to questions addressed to them. Return

- This honorific for the dead is generally used for Jews who were martyred or killed by anti–Semites. Return

- These biblical references are, respectively, to II Kings, 2, 10; Numbers 26, 11; and II Samuel 18, 10. Return

- Original note:* See “The Destruction of Zinkov” by Y. R. Return

- Original note: **See: “Zinkov Figures.” Return

- This alludes to a character in an early story with this title by Sholem Asch. Return

- “Woman of valor” are the opening words of Chapter 31 in Proverbs. Return

- Translated from Hebrew. Return

- Translated from Yiddish. Return

[Page 35]

The Zionist Pioneering Movement in Zinkov[1]

by Nakhum Yoshpeh

Translated by Yael Chaver

I remember well the day Dr. Theodor Herzl died; I was then seven years old.[2] This event had a strong effect on the town. His deeds might not have been widely known, but everyone knew his name. There were two Hasidic rabbis in town, most of whose followers opposed political Zionism, but on that day everyone felt the strong connection between Dr. Theodor Herzl and the phrase “May our eyes see Your return to Zion, with mercy” in daily prayers. The news of Herzl's death shocked the nation. The children came to kheyder that day (I was studying with the melamed Yoel Khodanchik) and said that a great Jewish man had died, one similar to Moshe Rabeinu.[3] The melamed scolded them, but one of the children added, “That's what my father said.” The Zionists in our town were very depressed because their leader had died.

Over time, interest in Zionism increased in our town. Whenever a Zionist congress was in session, my father would bring a copy of the HaTsfira newspaper from Proskurow, with a detailed account of the deliberations; the newspaper would be passed from hand to hand, even reaching Rabbi Moyshele.[4] The rabbi opposed secular Zionism on principle, for religious reasons, but made his peace with those who were unwilling to wait passively for the Messiah, and believed that they should emigrate to Eretz Yisra'el and settle there. He did not consider it a sin. My older brother, Menachem, once asked the rabbi, “Why shouldn't we accept Herzl as our savior, as the Messiah? Should we really describe the Messiah as the legends depict him, as an angel who will appear and sound a great shofar?” The rabbi answered him, saying, “It is difficult to imagine the Messiah as a physical creature. He may appear in the form of a prophet, too. But the Bible says that when Messiah will come ‘the earth will be full of knowledge,’ meaning that everyone will recognize the Messiah when he is revealed.[5] Previously, the Messiahs who appeared were recognized only by part of the nation; the end result was that not only did they not bring salvation, but caused much harm through their failure.” One must observe all the commandments and lead a righteous life, until the entire nation is in a condition that justifies salvation or, God forbid, damnation.

[Page 36]

The emissaries from Eretz Yisra'el would tell the Hasidim about Hebrew–speaking Jewish workers in the country who were becoming organized.[6]

The years passed, and my brother Menachem went away to study in Husyatin, near the Austrian border. He stayed with my uncle, David Blinder, who was a Zionist activist. On his visits home he would spread the word about Zionism among our young people. He would also bring copies of the monthly magazine Moledet, which was published in Jaffa.[7] My uncle was preparing to go to Eretz–Israel to inquire about settling there. I was a good artist, and planned to join him in order to enter the Bezalel Art School in Jerusalem.[8] However, World War I broke out, and the entire plan was dropped.

At the outset of the war, all Jews were expelled from the areas adjoining the Austrian border. Several families from Husyatin moved to Zinkov, among them my uncle David Blinder and his friend, the teacher Shmuel Fridman, both dedicated Zionist activists. As is well known, the Czarist regime prohibited Zionist activity, but this did not prevent them from quietly disseminating Zionist propaganda in the town. They were the center of a group of sympathizers, and set up Hebrew language classes.[9] Hebrew was the only language spoken in my uncle's home, and the children's names were biblical. His son Avshalom was killed during World War II, in Palestine, as a soldier in the British Army.

In 1917, after the revolution, my uncle David Blinder and his friend Shmuel Fridman openly encouraged Zionism. They founded a Zionist organization and named it HaTechiya, as well as a Zionist club bearing blue and white banners inscribed in Hebrew and Russian.[10] We collected books, mostly in Hebrew, and set up a library. Quite a large group of young people coalesced around at the club. We sang Zionist and national songs.

[Page 37]

We also established a drama group, led by the teacher Yisra'el Shteynberg, the brother of the writer Yehuda Shteynberg.[11] My uncle and Shmuel Fridman led ideological meetings, increased the number of HaTechiyah members, and saw to it that Zionist representatives joined public institutions of the community such as the school board. These meetings aroused strong debates, mainly with members of the Bund, headed by Abramovich. The Bund group in Zinkov was quite large, and comprised more members than the Zionist organization. There were also arguments between us and Levi Stoliar (the carpenter), the “Zionist worker,” who considered our Zionist organization a bourgeois group; his arguments with us and with Tse'irei Tziyon were as strong as those of Abramovich, the Bund member.[12]

Avraham Berenzon, Moshe Gershgorn, and I were in charge of keeping order. The fact that we were all members of the self–defense organization, which was unified regardless of political affiliation or ideological differences, was very helpful. At first, we carried out propaganda activity ourselves. In addition to Shmuel Fridman, my uncle David Blinder, and Moti Fayerman, we young people were also quite successful. I remember my brother Menachem saying, in one speech, “Our nation has preserved its existence as a nation for two thousand years, thanks to its ancient culture. It is like a stream originating in a spring of pure water. Its flow is strong and its water clear; when it joins the ocean, its distinctive flow is noticeable.” Everyone applauded, and even his opponents said, “Mendl is a good speaker.”[13]

|

|

Shmuel Fridman

(may his memory be for a blessing) |

The Bundists once brought one of their famous speakers to Zinkov. He started as follows: “I'm addressing the simple Jew with a beard.”[14] His pointed arguments impressed the listeners. He was followed by the teacher Shmuel Fridman, who was modest and physically weak, but was rich in culture and knowledge, and well–informed about Zionism. Speaking quietly and confidently, he analyzed the situation of the Jews in the Diaspora in general and in Russia in particular, saying, “The Zionist idea is planted in each Jew's heart, but orthodox Jews are waiting for the Messiah to come, while the others are waiting for the other nations to remind them of the vital need to return to their historic homeland. The Jew–haters do not distinguish between Zionists and Socialists. They hate us all, as Jews. A nation without a country is like a house

[Page 38]

without a foundation. Zionism strives to unite us as a nation in our historic homeland and restore us to a productive existence… A nation that speaks its own language, develops its own culture, and aims to live a normal life in its own country is accepted among the other nations. The world has already recognized this fact, and the British have given us the Balfour Declaration. Now it depends on us. We must prove that we are capable of being a nation like all other nations. If we do not make the effort now, when the door is open, it may not be opened for us if, God forbid, there is a catastrophe.” People, including his opponents, listened quietly and with interest to Shmuel Fridman. When the audience left, there was much talk: the Bundist speaker had spoken to the point this time; but, after all, Fridman was right…

Zionist speakers would also be sent to Zinkov from Proskurow. Ivi Zilberman, who resembled Ze'ev Jabotinsky in appearance and in speech, visited us.[15] He spoke in Yiddish, astutely and wittily. Sasha Nirenberg was a favorite speaker in Zinkov; he spoke Russian and attracted young people to his meetings.

Once, we held a week dedicated to Eretz Yisra'el. There were informational and entertainment events, and a display of Jewish strength. As I recall, this display consisted of a group of forty tall young men, wearing a uniform (which consisted of a blue–white cap, a shirt with blue insignia and a Star of David, and black trousers tucked inside Cossack–style striped boots). The group marched through the town like a military unit, headed by riders on decked–out horses. These riders included myself, wearing the uniform, and Avraham Berenzon, a dark–complexioned guy in oriental dress (as a symbol of the ingathering of exiles from east and west). The unit was preceded by a band, and followed by a large crowd. We held an assembly at the synagogue, and sang HaTikvah. Spirits were high, and faces shone… That evening, we had a party in the Firemen's Hall, with performances and recitations. The daytime parade and the evening performances provided a show of Jewish strength and the energy of the younger generation, that was to be directed towards productivity, construction, as well as defense.

Following the meetings and celebrations, we started practical preparations. We were connected with the HeHalutz central committee in Kharkov, headed by Eliezer Kaplan (may he rest in peace).[16] We were informed by the central committee that groups were being organized for agricultural training in the Jewish farming colonies of the Kherson area, and that people who wanted to immigrate to Eretz Yisra'el should register for training in those places.[17] It was clear to us all that the foundational premise of Zionism was a return to the land and to agriculture. There was much enthusiastic talk about the farming communities in Eretz Yisra'el and the cooperative settlement of Merhavya.[18] But of all the respected Zionists who sat at the head and passionately sang HaTikvah and the Yiddish song “We will reap rye there and no longer suffer from exile,” only two put their names down for training.[19] One member and I were preparing to start training at the Dobraya colony, but I had to postpone it for urgent family reasons. The central HeHalutz committee approved the postponement; but in the meantime Denikin's forces took control of the Kherson region, the training project was cancelled, and we remained under Skoropadsky's rule.[20]

So as not to be idle, Ya'akov Moshe Vartsman gave us a plot of land in 1919, where we could practice farming. It was a fine, large plot, surrounded by a tall fence. It was not suitable for field crops, and we only planted

[Page 39]

vegetables, such as corn and sunflowers. I would occasionally bring over one of my Ukrainian peasant acquaintances to teach us the basics of agriculture and show us how to plant and hoe. It was hard work, as we used our hands, with no plow or horses. But we loved the work, and made constant progress. Meanwhile, our region changed hands. Denikin's forces took control, creating a connection between our town and Odessa, from which – according to rumor – a ship was supposed to sail for Eretz Yisra'el. Avraham Berenzon and I set out for Odessa to check out the rumor. It turned out that the “Ruslan” had indeed sailed some time earlier, and there was no chance that another ship would sail soon.[21] While we were in Odessa, it was rumored that Denikin's forces were leaving our region. We hurried back home, so as not to be cut off. Sure enough, we arrived in Zmerynka and found ourselves in the midst of a fierce exchange of gunfire. At its end, Denikin's units retreated and a unit commanded by Petlyura's ally Shchepel entered the town.[22] Once again, we were cut off from the world. Intercity travel was also suspended, and our lives were in just as much danger as before.

|

|

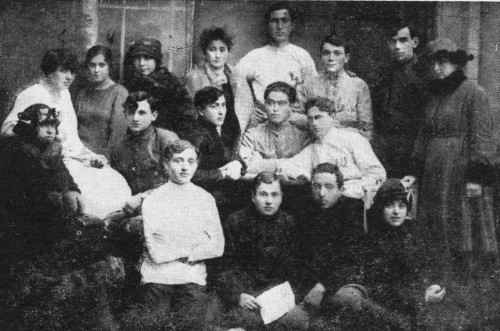

| HaTechiya Zionist Association, Zinkov |

In order to make good use of the difficult period I had to spend in Zinkov, I strove to create a larger, more substantial group of Zionist pioneers who would join me in immigrating to Eretz–Yisra'el when the time was right. Many who were over twenty years old had reservations and did not put their names down. Their excuse was that the situation in Palestine was unclear and therefore immigration was not practical. I then energized and organized a group of younger people, aged 16–17.

[Page 40]

A group of young people (17 boys and 2 girls) joined. We made all the formal preparations, so that we could able to leave once the borders opened. We had some money, which we had earned with our gardening. In addition to the official problems, I had to counter the objections of the parents. Though they were Zionists, they argued that I was organizing minor children, and that I should deal with the parents. I countered by explaining that no one was forcing their children to immigrate, and that leaving the hellish situation that had come about with the changes of rule and the extreme danger to the Jewish community, was in the interests of the children. But they rejected me with various pretexts.

|

|

| The group of Zionist pioneers from Zinkov, 1921 |

However, the political shifts and changes in our region were not over. Shortly afterwards, the Polish army entered, conquered all of Podolia, and reached Kiev. This was in 1920. Thanks to this new occupation, our links with the outside world were renewed. We had news from Warsaw that an immigration committee had been set up there; the committee organized groups of Zionist pioneers and arranged their move to Palestine. We also heard that a group of pioneers had already left from Kamenetz, and another group was being organized in Dunayevtsy. I went there, and found out that everything was now being organized from Warsaw.

At Passover, 1920, we heard the sad news about the events at Tel Chai, and the death of Yosef Trumpeldor and his companions.[23] This dampened the spirits of the local Zionists. They pounced on me, saying, “We were right in saying that hasty immigration was not a good idea, and that the situation in Palestine needed to be clearer.” My response was, “All the more reason to

[Page 41]

organize Zionist immigration; as far as personal security is concerned, immigrating to Palestine is the lesser of two evils.” I mustered the aid of Shimon Saliternik and his wife Mesiya (may their memories be for a blessing), who were seriously considering immigration, to pressure the local committee for funding to travel to Warsaw. I was able to travel there, and in two weeks had arranged the immigration documents and visas, and returned to Zinkov. However, the retreat of the Poles and the takeover by the Bolsheviks delayed our departure yet again.

|

|

| The group of pioneers from Zinkov at the grave of Dr. Theodor Herzl in Vienna |

[Page 42]

After many adventures, I reached Jaffa in five months (November 1920); the group of pioneers from Zinkov arrived only six months later, in early 1921. After that, Zinkov was closely linked with Eretz–Yisra'el thanks to its pioneers, builders of the country.

* * *

When we left Zinkov, the Bolsheviks were in charge, and the local Jews still enjoyed a measure of freedom in commerce and community life. Zionist activity went on, and immigration to Eretz–Yisra'el also continued to some degree, though there were already formal difficulties about leaving Russia. Some young people, as well as families whose children were already in Palestine, were interested in immigrating. The events of 1921 stopped preparations for immigration in our town, and families that were about to leave postponed their trip for a quieter time[24] Immigration increased a bit in 1922; several people and families immigrated to Palestine. These included the Frenkel family, two of whose sons had previously immigrated; Shimon Saliternik and his wife; David Stoliar and his family; Shmuel Fridman; the Zaltzman family; and a few other families. Please forgive me if I have forgotten anyone. My sister Fanny came with her fiancé Aharon Grabelski, and together we started seeking ways to make a living by agriculture for the whole family.

Not all those who immigrated from Zinkov at that time were satisfied. Some went back. One of the important Zionists of Zinkov, D. V., could not adjust to the work and to the living conditions that were generally harder than what he had been used to. He returned to Zinkov. When he was asked why, he did not say, God forbid, that life in Eretz–Yisra'el was not good. He said that the country was good for guys like Nachum Yoshpeh, who had the strength of an ox, the patience of a donkey, was satisfied with a meal of dried figs and pita bread, and could dance a hora with the guys after a day of hard work at the seaport.

Immigration from Zinkov did not yet stop completely. Shortly afterwards, the family of Zeyde Saliternik arrived, as well as my brother Moshe; and the Vartsman brothers. In 1926 my mother (may she rest in peace) and my brother Menachem with his family arrived.

In 1923, I joined the farming moshav of Merchavya; conditions were not too good. I lived in a small shack. We worked from dawn until late at night, hoping that conditions would improve with time and we would establish an economic basis for the whole family that would follow. I corresponded with Mother and my brothers in Zinkov, who were seriously considering immigration.

One day a “tourist from America” came and introduced himself as a former resident of Zinkov. His name was Ya'akov Halperin, and he had known my father well. He saw my meager “farm,” saying, as he left, “I'll write to Zinkov and describe the lives of natives of the town whom I visited in Eretz Yisra'el.” He did carry out his promise, and wrote a detailed letter about our townspeople in the country. When describing my poor, difficult life in Merchavya, he noted that I was living like

[Page 43]

“Vasil Buhatch.” This Vasil Buhatch was well known in Zinkov: he was a short, skinny, cross–eyed Ukrainian, who owned a small, old, broken–down cart and a lame horse. He would do small deliveries around town. His wife was similar: short, twisted, and also cross–eyed. They lived in a small old hut on the way to the river; every time we children would pass by we would pluck out some thatch from his roof. He would sometimes come out and scold us, but we were not afraid of him, poor guy. He was a symbol of poverty; his nickname, Vasil Buhatch, was a kind of euphemism: Buhatch means “rich.” It was this miserable, impoverished person to whom Ya'akov Halperin compared me in his letter to Zinkov. Mother was not told about this letter, to spare her suffering.

Luckily, another native of Zinkov came to visit me shortly afterwards. He viewed me and my farm quite differently. He surveyed every corner of my shack with affection, and joined me in the field. We did some plowing, and came back. As we parted, he said, “I'm so happy to have visited you.” This was Urkeh Frenkel (may his memory be for a blessing). He wrote to people in Zinkov that he had visited a new Hebrew village in Eretz Yisra'el, or, as it was called there, a moshav, where our Nachum Yoshpeh is living. “What can I tell you? He is living like a real Ukrainian peasant. He has a pair of horses and a plow, chickens and ducks, and the main thing is ‘he has his own bread’ and they lack for nothing. True, they live in wooden shacks, but that's not terrible. After all, winter in Eretz Yisra'el is not like ours. He has plentiful crops and is building a house. ‘This is what Eretz Yisra'el means!’”[25]

Translator's footnotes:

- Translated from Hebrew. Return

- Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) was the founder of modern political Zionism. Return

- “Moses, our teacher” is the familiar term for the biblical Moses. Return

- HaTsfira was a Hebrew–language newspaper published in Poland 1862 and 1874–1931. It became a daily in 1886. Return

- The quote is from Isaiah 11, 9. Return

- Rabbis living in Palestine would send emissaries abroad to collect donations for charitable institutions. Return

- The Hebrew monthly (1911–1928), whose name means “Homeland”, was a youth magazine. Return

- The school, now known as the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, was founded in 1906 by the Jewish painter and sculptor Boris Schatz. Return

- The revival of Hebrew as a spoken, secular language, was a principle and a hallmark of Zionism. During the pre–state period, “Hebrew” was often used as an adjective replacing “Jewish,” to signify the new way of life that was developing in the Zionist community in Palestine. Return

- HaTechiya is the Hebrew for “the revival.” Blue and white were the colors of the Zionist flag, and were later used for the Israeli flag. Return

- Yehuda Shteynberg (1863–1908) was a prolific writer in Yiddish and Hebrew. Return

- Tse'irei Tziyon was a competing Zionist youth organization. Return

- The last phrase is translated from Yiddish. Return

- This phrase is translated from Yiddish. Return

- I was unable to identify Ivi Zilberman. Ze'ev (Vladimir) Jabotinsky (1860–1940) was a charismatic Zionist leader, journalist, orator, and man of letters, who founded the militant Zionist Revisionist movement. Return

- Eliezer Kaplan (1891–1952) was an important Zionist activist who became a major Israeli politician. Return

- The first Jewish agricultural settlements (“colonies”) in the Russian Empire were established in the Kherson region in 1806, after a decree in 1804 that for the first time allowed Jews to purchase land for farming settlements. Return

- A co–operative farming settlement was established in 1911 in Merhavya, in northern Palestine. Return

- I was unable to identify this song. Return

- Anton Denikin (1872–1947) was a general who led the anti–Bolshevik (“White”) forces on the southern front during the Russian Civil War (1918–20). Pavlo Skoropadsky (1873–1945) was a Ukrainian aristocrat, military and state leader, who became Hetman of Ukraine for a few months in 1918. Return

- The arrival of the SS “Ruslan” from Russia in 1919 signaled the start of the third, significant, wave of Zionist immigration to Palestine (the Third Aliyah, 1919–1923). Return

- I was not able to identify Shchepel (or Shchepel). Return

- Tel Chai, in northern Galilee, was first settled in 1905, and in the wake of World War I passed under French control. On March 1, 1920, it was the site of the first armed skirmish between Arabs and Jews. Eight Jews were killed, including the admired commander Yosef Trumpeldor. Return

- The “events” consisted of violent riots by Arabs against Jews (May 1–7), which began in Jaffa and spread to other parts of the country. 47 Jews and 48 Arabs were killed; most of the Arab deaths resulted from clashes with the British forces, who were attempting to restore order. Return

- The phrases in single quotes are translated from Yiddish. Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zinkiv, Ukraine

Zinkiv, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 18 Mar 2021 by LA