|

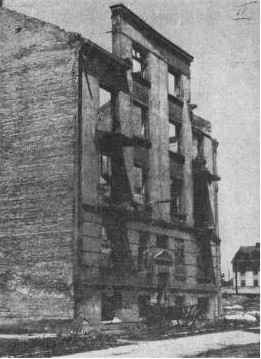

(Widok Street, number 3)

|

|

[Page 836]

Thus ended the bloody Thursday. The mass graves at the Jewish cemeteries, Zbylitow Mountain and in Skrzyszow forest were filled with martyrs, and Tarnow Jews were in cattle cars on their deathbeds on their last trip, to Belzec. The German murderers took all of the more valuable things from the orphaned Jewish houses, leaving the remaining Jewish articles for the Polish mob. In principle, possessions remaining from annihilated and deported Jews were confiscated on behalf of the German treasury and in the Hitlerist nomenclature were considered as Judengut [Jewish goods]. Members of the Gestapo sent the Jewish possessions to their families in Germany. The more expensive things, from murdered and deported Jews, were first gathered at the Judenrat then taken from there to German warehouses that were located on Kaplanowka. Jewish furniture was also taken there.

A feeling of frustration reigned over the remaining Jews after the deportation aktsia. Those who had saved themselves looked at themselves in disbelief. Although no one said a word to another, everyone's eyes reflected a silent question: “You are alive?” How did this happen? They were themselves astonished that they remained alive. Like a surrounded animal that runs from one place to another even after the departure of the persecutor, unsure if there is still any danger, did the Tarnow Jews who survived the cruel slaughter leave their lairs, hiding places and residences, cautiously and with distrust, quivering and with anxiety, looking around on all sides to see if the German murderers awaited them.

A strange thing. There remained then in the Jewish quarter of Tarnow

[Page 837]

up to 20,000 Jews and few of them thought of running away, about escaping from the encirclement. It was clear that the Germans had given out a death sentence to the Jews of Poland. After the aktsia on the 1st of June that was played out in all of the large Jewish centers in Poland, it was difficult to have any illusion concerning the true plans of the Hitlerists with regard to the Jewish population. Besides, the Germans were concerned that the Jews could change their minds and recover. Tears were not yet dried; they had not yet found their separated and lost families and the next morning, another deportation. On Friday, the 19th of June 1942, notices suddenly appeared on the walls of the city about the decree of Hakbart, the starosta [city chief], to create an enclosed ghetto for Jews. From then on, it was not only the Gestapo that was engaged in the murder of Jews. All deportations, confiscations of Jewish possessions, catching [Jews] and mass deportations were sanctioned by administrative decrees from the occupying power.

The Hitlerist hangmen organized the ghetto in order to surround the Jewish population, to separate them from any contact with the outside world – an old, known method from hundreds of years back that the Germans had once applied to the Jews in Germany. Once, in the 16th century, there existed crowded, overflowing ghettos, in Frankfurt, in Prague and in Worms, that could not absorb all of the Jews from a given area. Jewish families lived tightly packed and in filthy, small alleys, which led to crooked steps or ladders. Entire families with children and grandchildren lived in small rooms similar to stables. Brick walls surrounded the German ghettos and one or more gates connected the ghetto to the city. The gates from the Jewish quarter were guarded by a municipal guard who would lock the gates at night, Shabbos [Sabbath] and Sunday, Jewish and Christian holidays. However, local Jewish life developed in these closed Jewish areas during the time of the dark Middle Ages.

The Hitlerist ghettos of the 20th century were converted into prisons where tens and hundreds of thousands of Jews were squeezed in for only one purpose: to physically annihilate them. If certain measures from the earlier ghettos were supposed to make the nightmarish fate of the Jews a little sweeter, it happened in order to put their vigilance to sleep and lead them to a mistake. All of the facilities and arrangements about ostensibly converting the ghettos into [so–called] “Jewish republics” with their own governments – Judenrat, with their own police – ordernundienst – their own

[Page 838]

post office on their own “territory” and – as in Lodz – even their own currency, was a swindle. The Hitlerist ghettos were closed prisons where the tortured and exhausted Jews were driven to slaughter. The ghettos were created only for this purpose.

Only a few houses were allocated to the Tarnow ghetto. According to the decree of the starosta [village elder], 20,000 Jews, as well as converts to Christianity, had to move into the ghetto within 48 hours; [the ghetto] consisted of a few streets: the Pad Dember Square, the left side of Pilsner Gate, the left side of Lwowska Street. The gates of the houses were closed. The exits thus led into the ghetto; an opening onto the courtyard of house number 6 –with an entrance into this house – was created through the brick walls of Lwowska 2 and 4.

|

|

(Widok Street, number 3) |

[Page 839]

Thanks to the openings hacked in the back walls of these houses that were connected to each other, from there, one could reenter the houses on Lwowska, numbers 10, 12, 14 and 16. From house Lwowska 16, the ghetto went through Zamknienta, Szpitalna (after Wictum's house) alleys up to Jasna and through Folna Street, the right side of Goldhamer Street, Drukarska and Nowa up to Falwarczna Street. This small area was fenced in with barbed wire.

Today, one can still recognize the entire ghetto area. After the Germans left Tarnow, all of the houses of the former ghetto were searched by Poles who looked for hidden Jewish treasures. Only ruins and skeletons of houses remained where Jews lived during the occupation.

Gates led to the ghetto – two on Wolanska Square and one on Falwarczna Street near the Judenrat; the fourth gate was on Pad Dember Square, near Apel's restaurant. At the gates, at the external guard posts, stood a Polish guard, the so–called Granatowa Police [Blue Police – the Polish Police of the General Government]; the Jewish policemen stood on the innermost side near the gates. The S.S. Oberscharführer [senior squad leader Hermann] Blache, the ruler over the life and death of the ghetto residents, reigned in the ghetto itself. He lived at number 24 Lwowska Street. The ghetto was very quickly transformed into the most frightening torture place for Tarnow Jews and for Jews from the surrounding shtetlekh that had been driven into the confined living area.

Among other things in the accusation against the mass murderer, Amon Gothe, it was said: “In the area of the Krakow District a ghetto was first created in larger and smaller cities, among which the ghettos in Krakow and Tarnow were more famous than any others. Both were bloodily liquidated by the accused Gothe.”

Approximately 20,000 Jews spent the night in this prison, several dozen people to a room, in terribly unhygienic and unsanitary conditions.

The Germans allowed the Jews only their own Judenrat and their own police. The Judenrat in Tarnow also established a special Jewish postal system, it should be understood, by order of the German regime. The postal system was led by Mrs. Bronislawa Perlberg. The German's stamp with a printed “Jewish Post” was pasted on letters. The postal system was abolished after the third deportation. Incidentally, it was only for correspondence between Jews. It was strongly forbidden to have any written contact with the non–Jewish population. There was the death of threat for receiving a letter from a Pole outside the ghetto. That is how Manya Korn perished. The wife

[Page 840]

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| Jews in the Tarnow ghetto | ||||||

[Page 841]

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| Jews in the Tarnow ghetto | ||||||

[Page 842]

of the lawyer, Dovid Lenkowicz, member of the kehile council and leader of the left Poalei–Zion [Workers of Zion – Marxist–Zionists] in Tarnow was killed for corresponding with Poles. The young doctor, Lustig and Miss Argand also perished for corresponding with Poles.

A number of Jews had to be employed at forced labor. The ghetto inhabitants left every morning under the guard of the Polish or Jewish policemen to work for various work places outside the ghetto . There were also those who had individual passes to go to work outside the ghetto without a guard. Those who did not have work or could not work lived by selling their possessions. They would give these possessions to the Jews who went to work outside the ghetto and they would receive food for them. Those who did not have anything to sell lived in constant need. Poles also would smuggle food into the ghetto [and that involved] great danger.

Things went well for the members of the Judenrat and their many bandits. These people bathed themselves in luxury. They always placed new taxes on the ghetto inhabitants. Some of the money went to the treasury of the German hangmen and some to the banquets and amusements that certain members of the Judenrat arranged night after night, for themselves and their “ladies.” They were not very absorbed with what took place in the ghetto. Meanwhile, the Hitlerist scoundrels, Rommelmann and Grunow, did not sit with idle hands – they shot, murdered, robbed. Instead of reminding those who did not present themselves for work – [there was] a bullet in the head from behind. Ghetto Commandant Blache's children were trained in the art of shooting individual Jews.

There also were noble, illustrious figures in the ghetto who began to organize help for the poor and hungry in this tragic, difficult situation. There were many who suffered from hunger. Once the most respected citizens, rich merchants and entrepreneurs, lawyers and doctors, simply begged for a piece of bread.

In addition to the orphans' house that was moved into the ghetto after the first deportation, four people's kitchens were arranged which provided several thousand lunches every day. A division for social aid that was active at the Judenrat was led by former communal workers. They displayed a great deal of initiative and activity in order to receive more funds from the Judenrat and help the population which suffered from need.

The khevre kadishe [burial society] was also active in the ghetto. It worked with self–sacrifice. Despite the mass [number of those] murdered, it wanted to follow

[Page 843]

Jewish law when burying those who perished. The khevre kadishe was a division of the Judenrat and the work there was considered the most difficult. When Tarnow Jews began to believe that they could save their lives through work, hundreds of Jews knocked on the door of the institution pleading for work from Yehoshaya Sztub, the manager,. The Gestapo increased the number of workers at the khevre kadishe to 50 before the first deportation aktsia. Dedicated to the work were: Wolf Weksler, a son of Moshe Weksler, who was descended from an old Orthodox family; Hachauzer, the son of Aba Wieczner [Aba from Wieczyn], Chaim Kuperman (now – rabbi in one of the cities of South America). They were always on duty; worked day and night. There were no days without Jewish victims.

Zekhor, the previously mentioned book by Eliezer Unger (son of the Rabbi Yisroel Yosef Unger, of blessed memory), now director of the Aliyah [immigration to Israel] office in Paris, tells of the superhuman work of one of the members of the khevre kadishe, based on his [Unger's] own experiences in the Tarnow ghetto:

“The Judenrat housed several refugees and deportees in my father's house of prayer, mainly the old and poor people. Among them was a certain Yehiel Meirl, a modest, pious old man, who

|

|

| This picture and the pictures on pages 841–842, found by the Rabbi Yehuda Auseibel (Geffen) after the war in a residence of a Hitlerist family – give witness to the German torture in the Tarnow ghetto.[1] (In the picture from the right: Reb Alter Lewi, of blessed memory, and Reb Naftali Zvi Irum, of blessed memory) |

[Page 844]

took upon himself the removal of the dead. It was not easy for the old man to fulfill his duty because the number [of dead] increased that last spring as a result of the typhus epidemic and poor nutrition. Firstly, movement of the old man in the street was very dangerous. Secondly, as a member of the khevre kadishe, he would be called to the Gestapo where Jews were shot in the courtyard, and he then had to remove them. The remaining members of the khevre kadishe were afraid to enter the courtyard of the Gestapo. The old man, Yehiel Meirl, immediately ran there when he learned that there was a martyr in the Gestapo courtyard, so as to provide him a Jewish burial. Even on the most terrible days, when the Gestapo murderers , Rommelmann, Van Moltka and Grunow came to the ghetto for fresh victims, the old man was not afraid to run to the kitchen for the poor, carry home a spoon of cooked food for his sick neighbor, or to do his work of removing Jews who were shot. More than once he returned home from funerals bruised, covered with blood. A vile murderer often placed his revolver on [Yehiel Meirl's] chest. It did not frighten him and did not turn him away from doing good. At night he read the Zohar [main work of Jewish mysticism] and Kaballah; during the day he cleared away the dead. One morning he learned that a Jew who had been shot was lying in the courtyard on Goldhamer Street. This Jew was denounced by the landlord as a Bolshevik who had returned not too long ago from the Soviet occupied area. All of the neighbors warned the old man not to go where the victim lay because it was not known if the Germans had left that spot. However, he was determined: ‘The removal of the dead is one of the greatest mitzvahus [commandments].’ He left for the place of the crime and began to work with the dead one ; the murderer, recognized him from a distance. The old man fell, shot onto the dead body of the earlier martyr.” (p. 132)

Not all residents of the Tarnow ghetto surrendered passively to their tragic fate. The idea of staging a revolt against the subjugation was born among a number of the young who had been raised in various pre–war youth organizations. Immediately after the first deportations, several young people from Hashomer Hatzair [the Youth Guard – secular Socialist–Zionist organization] brought up this idea. The most active among them were: Yosek Bruder of Hashomer Hatzair, Shmuelik Szpringer [Shpringer], the Jewish policeman, and the communist, Malekh Binensztok [Binenshtok].

[Page 845]

They acquired weapons and established connections with the Polish underground. It was proposed that a Jewish fighting organization be created, using the example of Warsaw. We write in detail in another place about the plans of several dozen Jewish young people from Tarnow who took on the challenge against the enemy and raised the flag of revolt against the German hangmen. The fighting spirit of all of the young people came to particular expression during the further deportations from the Tarnow ghetto. However, these were weak, spontaneous reactions. Twenty thousand Jews, the community at large, were squeezed together in the ghetto, patiently working for the Germans, hungry and suffering.

Meanwhile, the murderers, Rommelmann , Ash and Grunow prepared for a new slaughter of the Tarnow Jews. They did this slyly, covertly, although they had not ceased torturing and shooting individual Jews. After the first deportation, when eight Jews returned from the Pustkow camp as they were incapable of working, shot them himself in the courtyard of the Judenrat.

Three months passed in 1942 after the first deportation in June. The bloody wounds from the first death action had barely begun to heal; the tears that resulted from the deaths of those close to them had not yet dried when a new registration – on the first day of Rosh Hashanah (the 11th of September 1942) –was suddenly ordered. The Jewish policemen took the work cards, explaining that new stamps would be placed on them at the Judenrat. Now no one doubted that this was a sign of a new deportation, a new blood bath. There was a stir in the ghetto as in an ant's nest. They again saw rescue. The stamp would protect them from a bullet, from torture, from a mass grave, from Belzec, from where everyone knew no one returned. They struggled for work cards with the new stamps. Twenty thousand Jews lived with only one thought: how to obtain the stamp, the accursed amulet of life. Let it be [a life] in need, in the ghetto – but it was still life. This also meant surviving the war, waiting for a better morning.

It was difficult to receive a stamp from the Judenrat so they found another solution. They provided themselves with a stamp copied by an honest Jewish artisan, Rab. Despite the threatened danger, he stamped the work card with a stamp of his own making for a minimal cost. There were also those who had a great deal of capital or valuable things. They paid the Gestapo people large sums for a stamp.

Those who could not obtain a stamp or did not even have a work card hid in cellars, attics,

[Page 846]

bunkers. There were hundreds in the bunkers and as many as 200 people (as, for example, in Mandelbaum's house), equipped with lights, water and food for several days. At night on the same day a number of residents of the ghetto – those without stamps and without work cards – went into hiding places and bunkers to breathlessly wait, survive the second deportation and wait for its conclusion. Those who did have the stamp and work cards for their entire family waited, trembling, for what the next morning would bring.

This was a bloody Thursday, the 12th of September 1942. The ghetto was surrounded by the Gestapo and Polish police (Granata [Polish police in German occupied areas]) right at dawn. They began to drag all of the Jews and their wives and children from houses –those who had a card with the stamps and those who did not. Everyone was taken away to Magdeburg Square (Wolanska [Freedom] Square), where the bus station was located. They were told to kneel and bend their heads to the ground. The large square did not fill up quickly. When the German hangmen saw that there were few Jews, they appealed to the lowest instinct of the unfortunate ones: ordered them to reveal the bunkers and hiding places. For this vile deed the men were promised the return of their wives and children who were kneeling on another part of the square. Alas, there were those who let themselves be persuaded and for a price showed the Germans the bunkers in which 100 or more people were located, and saved themselves. The large hiding place in Mendelbaum's house on Szpitalna Street, in which 200 Jews were hidden, was revealed.

Among other unfortunate ones chased from the bunkers was Reb Mendl Leib Grinsztajn [Grinshtein], a distinguished, deeply religious Tarnow citizen who, however, had an understanding of the tasks of the time and did not prevent his children from taking an active part in the Zionist movement. Reb Mendel Leib Grinsztajn's three sons – the well–known Zionist leader, Dr. Yitzhak Grinsztajn (Shamir), chairman of the Zionist organization in Bielitz [Bielsko] Silesia) and manager of the Israel trade mission in Poland during the early days of the land of Israel – Chaim and Moshe Grinsztajn, and also his daughters, Golda and Malka – now live in Israel. Reb Mendl Leib Grinsztajn was dragged away from the bunker to Belzec where he perished al kiddush haShem [as a martyr – in sanctification of God's name]. Honor his memory!

The selection took place on Magdeburg Square. Those who had work cards with a stamp were separated. Those who did not have the paper had to kneel in another

[Page 847]

area there. Those who had the stamps but whose children were with them when the 3,000 Jews without work cards were assembled and who did not want to separate from their children were sent immediately in a transport to Belzec.

However, the number of Jews who possessed work cards appeared too large for the German hangmen. They wanted to decrease the number. The murderers carried this out immediately. They ordered those who possessed the work cards to march past. Every tenth one was pulled out of the rows and forced to go to another area where there were already those who had been sentenced. Nineteen year–old Moshe Alban, raised in HaNoar–HaTzioni [The Zionist Youth], could not be convinced to kneel in front of the German murderers. When a German soldier gave him a blow to his head with the butt of his rifle, Alban reacted to this as a proud Jew who knew how to die with dignity. He slapped the German, spit in his face and shouted: “Now shoot me, bandit, now you have a reason.” The young Moshe Alban perished from a German bullet on the spot.

Old people in Wolanska Square were immediately taken to the cemetery. There, naked near the wall, they were shot and thrown into prepared pits. The Poles from the “construction service” searched the clothing of those shot, looking for “Jewish goods” under the watchful eye of the Gestapo.

The second group of Jews, kneeling at the second spot, were sent to the school named Czacki, where the warehouses were located for stolen Jewish goods while the owners of work cards with the stamp remained at the square. A second transport for deportation was prepared at the Czacki School. On Friday, the 13th of September 1942, approximately 3,500 Jews walked on Krakow Street to the train station. Again Tarnow Jews were sent to the death camp in Belzec. For the last time, they went through the streets of the city where they were born, grew up and worked. The tortured, tired figures were urged on by the Hitlerist hangmen. They went to a martyr's death. Among those unfortunate Jews were Rywka Zilberfenig (from the Rapaports), and, as the surviving Tarnow Jews told it, she walked in the death march with a proud, raised head, not weeping and not crying. Golda Mazel, who was notable among the chased masses, held herself with dignity and courage.

The Gestapo, German police, Granatowa police and the Judenrat – all fulfilled their tasks as usual during the second aktsia.

[Page 848]

When the contingent of condemned Jews was insufficient, the German murderers went to search for hiding places, which in many cases, were pointed out by Jews. At the last moment these weaklings broke down, believing the German promises that for giving up 20 Jews, their wives and children would be returned to them. These unworthy Jews later perished at the same murderous hands.

The entire night trained dogs led by the Gestapo hunted for hiding places where women and children, old people and the young were located. Poor Jewish children! Torn from their parents, they did not

|

|

| A Jewish child in the Tarnow ghetto (the photograph is of the grandson of Maurici and Ester Laub) |

[Page 849]

cry nor ask about anything. The children immediately understood what the fear and desperation on their parents' faces meant. One word, “escape,” was enough for them to understand the situation. They hid in cellars, attics, holes, crates, wherever it was possible, quiet, rolled up together, they waited with pounding hearts. Until the German beasts would stop. They waited futilely. It was difficult to hide from the German murderers and their wild dogs.

Who is capable of describing the hell of Jewish children and their parents who could not help them and went with them to annihilation? The moment was terrible when the parents, a mother or a father particularly, had to separate in a moment: to remain alive, but without their child, [who was] sentenced to death, or to take part in the child's fate. This was not a spiritual distress, no inner struggle. This was a decision, outside of human thought, that reached the deepest depth of a person. It is difficult to explain what [led to the decision] at that moment – all the parents remained with their children.

There was a case when German bandits took from Tulek Facher, the cap–maker, his only child and led him [Tulek] to the group of those capable of working. He did not think for long and said to the Gestapo murderer: “You will shoot me only with my child!” The German immediately shot the cap–maker, his wife and his child.

That night, Leon Lezer searched in the ghetto for his seven year old nephew whose father had been dragged out of a bunker during the day. Before the historical commission in Krakow, Lezer told of the experiences of the terrible night:

“I went through almost the entire ghetto and did not find the child. Finally I came to a house where a rotary press was located and began to call out. After several moments, the child crawled out from under the press because he had recognized my voice and said, ‘Uncle! ’ The child had lain there from eleven in the morning until two at night with three other children. I gathered the children and took them to their mothers, who were gathered on Wolanska Square. There I learned of a well–disguised bunker that was located in an open square under the ground and undiscovered up to that time. I took the children there and returned to the square, thinking that they would remain in a safe place. Early in the morning, those remaining were permitted to go home. The others (from the Czacki school) were taken away…

“Our windows looked out onto the square where the bunker was located in which the children were hidden. I wanted

[Page 850]

to go after them to bring them home. But their father advised me to wait another half hour. Five minutes had not passed when we saw three members of the Gestapo and a Jewish policeman and a dog. They went in the direction of the bunker. No doubt, someone had pointed it out because they went to that site. The dog sniffed at it; the father of the children was sure that they would not be found because the bunker was well disguised, but the Germans went with great certainty. I stood with my sister–in–law and the father of the other children, Shimkha Temer, and waited in the greatest stress. After a while, the Gestapo left the bunker followed by an old Jew; behind him was my nephew's frightened child, and after the rest [of those in the bunker], approximately 20 people. They told the child to kneel with his face to the ground. The mothers themselves appeared and turned themselves in to the Gestapo. They were told to leave, since they had work cards, but the mothers did not want to leave their children. My sister–in–law saw the child, went out and surrendered to the Gestapo. They told her to kneel, one member of the Gestapo found her suitcase and told her to give them all of her valuable things and money, and threatened her with death. In the presence of the fear of death among these mothers, the Germans did not forget about gold and wanted to steal whatever was possible from the condemned. People gave everything and Shreder of the Gestapo began to search everyone to see if they had anything hidden. The mother of these children, Mrs. Temer, had to undress completely at his order and something was found sewn in her shirt. Wanting to shoot her, he told her to go to the side and turn around. She begged him not to kill her; she grabbed his hand, saying she had forgotten about this. However, the German continued to shout that she should turn around. When this did not help, he shot her in the face and when she fell down, he shot her with several more bullets. Her 10–year old daughter, seeing this, screamed, lifting her small head; then the murderer ran to the child, gave her a blow over the head with his cane and killed the girl on the spot. Our child kneeled, rolled up, hugging his head to the ground, not even moaning. Then, the people were ordered to stand up; their valuables were taken from them and they were taken to Wolanska Square to the remaining condemned.”

The second deportation lasted for two days. Around 7,000 Tarnow Jews then filled the gas chambers of the Belzec crematoria. Hundreds of Jews and Jewish children were brought to mass graves

[Page 851]

in the Jewish cemetery. Yes, as usual, the Gestapo, Polish police and the Judenrat fulfilled their task.

The Germans again made their devilish plans to annihilate the surviving Jews, after the second deportation, when only 12,000 Jews remained in the Tarnow ghetto. They prepared systematically, methodically and in secret.

This was apparent from every German decree that was issued for the ghetto after the second deportation. Little by little the rope was drawn around the neck of the weary Jewish population, [which had been] weakened physically and spiritually.

Except for a few individuals, they stopped issuing certificates giving permission to pass outside the ghetto. From then on the ghetto residents had to march to work in groups, standing in a line under a guard. Leaving the ghetto became more difficult. The guard posts of the Polish Granatowa police were fortified around the ghetto. More attention was paid to the Jewish police who guarded the ghetto from inside. It appeared that the Germans even stopped trusting them. It was unnecessary to wear the precise armband now. No Jews could leave the ghetto as an individual. Therefore, there was no fear that the Jews could hide their origins [as Jews]. The armbands that every Jew had to wear until now were replaced with other insignias. There now existed one measure for the Germans to evaluate if a ghetto slave was useful for the German military machine, which meant that he still had the right to live. Only the Jews who were employed in one of the enterprises that worked for the war industry had this right. There were no illusions in regard to this, that without a workplace and work card one was lost. In the ghetto, they had the illusion that the work card meant a lottery ticket with life as the winnings. Almost everyone believed in this.

Moreover, the Germans did everything to create the impression that those who worked would think that they were saved. Now they received new armbands with the inscription R.W.Z. (Richtung Wehrmacht Zivilbetrieb [Army Munitions Civil Enterprise]). Whoever wore such markings was certain that he worked for an important purpose, that he was safe from further anti–

[Page 852]

Jewish aktsias. They believed, had illusions and patiently worked in German enterprises.

And the others? The number of work places was limited then. Fifteen thousand Jews were now located in the ghetto because several thousand Jews had arrived from the surrounding towns where the local ghettos had been liquidated and the survivors driven into the Tarnow ghetto. The Jews who did not have work understood that they were under threat. The non–Jewish environment was indifferent, often hostile to the suffering Jews. There also were a few exceptions when Poles made it possible for Jews to hide in bunkers.

There were cases of escapes from the ghetto. Only those who had enough monetary means to organize the escape could take this step, which incidentally was very risky and dangerous. And in most cases it ended with the death of the entire family of the escapee. They escaped to Bochnia and, from there, a road led to Hungary. Several Jewish families succeeded in escaping on this road and saved their lives. Because the procurement of such identity cards was connected to difficulties and danger, they began to forge them.

The escape with Aryan papers that did not require as much money was more common. They bought baptismal certificates and identity cards – personal documents during the German occupation in Poland.

The group of young shomrim [guards] that we already mentioned who were in the ghetto at that time, after the first deportation aktsia immediately undertook the organization of a resistance movement, and made contact with the Polish underground. In the beginning their activity was limited to giving help to those who had decided to leave the ghetto and to escape into Poland or to Hungary. One of the organizers of the group (now in Israel), Yosef Birken, describes the part taken by the guards in the underground movement in the Tarnow ghetto (Mosti, April 1947, Lodz). In his residence, where his trusted comrades came together, his sister Franka (now in Poland) “fabricated” baptismal certificates in the Latin language until late at night. Despite the tragic situation, he writes, “We laughed more than once when searching for family names and names of god parents, midwives, priests and the like. The Latin stamps of the Ochawa and Lipnica Murowana parishes were created by Jasek Bruder.”

Only those who had a “good appearance” and spoke Polish well could make use of Aryan papers to escape. A Jewish–appearing face and poor mastery of the Polish language could betray the one hiding. And who wanted

[Page 853]

to hide a Jew at that time or give him help? However, there were individual cases when Poles showed a full heart and understanding of the tragic situation of the Jews and they came to help. Thanks to this, several members of the Postrang and Landman families survived. They were hidden with the Pole, Banek, in the attic of his house. A railroad worker from Mościce saved the Jewish Betrubins family. The Mitler family hid in a bunker with a Polish family. There also were cases where peasants hid Jewish families who had escaped from the ghetto.

As mentioned, these were rare exceptions. The Jewish community felt surrounded, besieged and, wanting to save their own lives, began to build bunkers and hiding places. Various hiding places appeared, often deep in cellars and in open spaces; some of them had electric lights. Food was prepared to last for a long period of time. Those who were not assigned to any work and did not possess a work card were ready to hide under the ground, at least during the time of the deportation aktsias, which were awaited with fear by everyone.

Need in the ghetto grew. Hunger and disease helped the Germans annihilate the Jewish population. The Jewish hospital was overflowing. The hospital director, Dr. Eugeniush Szifer [Shifer] could not cope with so much work. The more prosperous Jews had already sold everything and remained completely without the means to live. Those who once had hidden their savings or valuables somewhere could not reach them now. They remained without the means to live and begged for a piece of bread. The food emergency in the ghetto became still worse. The ghetto itself also had to procure food in an illegal manner because who would provide food for the ghetto residents, if not the ghetto residents themselves? The members of the Judenrat had a restaurant with all kinds of good things that was located at Lwowska 4. Only members of the Gestapo and those who served them could make use of the restaurant.

They gave out watery soup at the people's kitchen at the Judenrat because the food allocations for the kitchen were negligible and the majority of the ghetto citizens needed to provide for their food themselves. This was possible as long as both those who worked and those who did not work lived in the ghetto, because those who left the ghetto for work could bring in certain foods, bought for a great deal of money, although with difficulty and risk. However, now the entire matter was made more difficult and complicated because when the hangmen Grunow and Rommelmann learned about this they strengthened the guard at the ghetto gates and ordered rigorous personal searches of those who returned to the ghetto from work. Discovered food would be confiscated and during one such search, Grunow, the murderer, shot the wife of Biegleizen, the hairdresser (lived on Goldhamer Street) because she was bringing food for the ghetto.

[Page 854]

In these circumstances, the ghetto population, starving and tortured, waited for the future aktsia. They searched for various ways to hide, to escape from the local prison. However, the possibilities were very limited for this. Only a small handful of young shomrim who had been preparing armed resistance for a long time decided to sacrifice their lives. The previously mentioned Yosef Birken related (Masti, Lodz, April 1947) a few memories about the attempt to organize a resistance in the Tarnow ghetto. The author describes:

“After the first deportation in Tarnow, Yosek Bruder left for Lemberg where he arranged for Aryan papers for his wife's family. Fearful of being mobilized in the army in the territory of the former Galicia district, he returned to the Tarnow ghetto with his wife Giza Gros, also a member of Hashomer Hatzair [socialist–Zionist organization – the Young Guard]. At that time a number of members of Hashomer Hatzair began to create a resistance center to which belonged (in addition to Yosek Bruder and his wife): Szisler [Shisler] and his sister, Yehezkiel Kriger, Kubtsha Kuperwaser and a group of other people. Among them the Ordnungs [security] man (Jewish policeman) Shmulik Szpringer [Shpringer], pseudonym “zibtsentl [little 17],” and the communist Malekh Binensztok [Binenshtok]. The initiative for the group lay in the hands of Yosek Bruder. As the former head of a battalion, to which Y. Bruder and R. Szosler also belonged, as well as a former member of the main council in Lemberg, I enjoyed the trust of the entire group, although organizationally I was only loosely connected with it at first, and always in contact with Polish groups. After the second deportation (September 1942) our collaboration became energetic. I have the impression that the young men, losing contact, eventually having difficulties in contacting the Krakow group, left to their own devices, looked for support nearby. It should be understood that the most important task was to obtain weapons. We succeeded in obtaining four pistols. The security man, Shmulik Szpringer (shot by a member of the Gestapo when he let a person through the ghetto gate

[Page 855]

who was not entitled to go), had usually led one of us out of the ghetto to the Aryan side under a convoy and after this took the weapon back into the ghetto. Wanting to have a smooth contact with the Aryan side, I tried to get assigned to forced labor on the ramp in Mościce. There, I received radio bulletins, information about the plans of the Germans, deadlines for the deportations and so on from Polish friends. The young men came to my residence after returning from work.”

We have already mentioned how baptismal certificates were manufactured to obtain Aryan papers in this residence. Others in the group were occupied with direct actions outside Tarnow.

Yosef Bruker writes further in his memoirs: “At the time, Yehezkiel Kriger, who wanted to take direct action at any cost, separated from our group. Yehezkiel went to the east and he killed Germans on the Przemysl–Lemberg–Stryi train line. He shot two gendarmes, among others, near the train station in Przemysl. He perished amidst shooting in Sambir, having killed at least several dozen Germans.”

Meanwhile, the Hitlerist murderers prepared for the planned aktsia. Several days before the 15th of November 1942, an order was published that Jews who were in hiding across the villages and shtetlekh could return to the designated cities without any punishment, provided they live only in enclosed areas, that is, in the ghettos. Tarnow also was included among these cities. This was simply a vile bribe of the unfortunate Jews who this time, believing the German assurances, left their hiding places in the villages and small cities in great numbers to permit themselves to be closed in the Jewish jail that was called the ghetto.

On the 15th of November 1942, when all those working had left for their workplaces, the entire ghetto was surrounded by the granatowas (Polish) police and a group from the Gestapo entered the ghetto. The frightening seizure of people began and those unable to hide immediately fell into murderous hands. The captive Jews were sent to the train station where a fresh transport to Belzec had been readied. Because a large number of unemployed ghetto residents were hiding in bunkers and

[Page 856]

cellars, the German did not have enough Jews for the shipment that was designated for slaughter. Therefore, the Gestapo hangmen went to a number of workplaces, took the workers from there and drove them straight to the train station. A number of workplaces were entirely liquidated then. At others only a selection was carried out. Two thousand five hundred Jews were sent to Belzec on that day. These came from those languishing in the Tarnow ghetto, perishing in a martyr's death in the Belzec death factory.

The third deportation aktsia was directed mainly at those not working, older people and old men. This time again, the German murderer did not succeed in entirely annihilating the children, old and unemployed. A small handful were temporarily saved thanks to undiscovered bunkers; others arranged for Aryan papers and there also were those who succeeded in escaping from the transport whilst the death train was taking them to Belzec. Several of them returned to the Tarnow ghetto to their remaining relatives. Persecuted and mistreated, they could not find a place of refuge anywhere. It is true that they had a roof over their head in the ghetto – but for how long? Blache, the ghetto commandant, the subordinate oberscharfuhrer [senior squad leader – Nazi party paramilitary rank], had already assured that the 10,000 Jews who remained in the Tarnow ghetto would not have one moment of calm. His daughter, an animal in human form, boasted that, “the Fuhrer himself [Hitler] gifted her father with 8,000 Jews.”

On the morning after the third aktsia, Blache ordered the division of the ghetto into two parts: ghetto A and ghetto B. All of the old, the sick, the children and those who had no designated workplace were shut up in the first part. All of those working had to live in the second ghetto. Whoever could, ran to work. Illusions again emerged that work could save one from death. New workplaces were created in the ghetto itself, if only one could manage to get into ghetto B.

Both parts of the ghetto were divided by fencing. Crossing from one ghetto to the other was strictly forbidden. The purpose of such an arrangement was clear. No one any longer doubted that those from ghetto A were condemned. If they did not perish from hunger they would sooner or later be taken to Belzec or to another death camp. And actually – a frightening hunger ruled in ghetto A. But thanks to the secret help from ghetto B they could receive a little nourishment. Those working maintained a kitchen in ghetto B. They gave [to ghetto A] a third of the food allocations that they received as workers. As this kitchen

[Page 857]

was located between the border of both ghettos, it was possible to give a number of lunches to the unfortunates in ghetto A. In addition there were those noble and devoted Jews, such as Henrik Holender, Wolf Weksler, Yisroel Glacner and others, who would bring help to the hungry by collecting sums of money from the better situated working Jews on behalf of their brothers in the neighboring ghetto.

The number of Jews in the Tarnow ghetto grew because the remaining Jews from the Nowy Sącz ghetto that was liquidated at the end of 1942 were brought there. All ghettos in the Tarnow area were liquidated and the remaining Jews sent to Tarnow. Thus, the Jews from Brzesko and Szczucin arrived in the Tarnow ghetto.

There were no mass aktsias during the following months. The first half of 1943 passed without a larger deportation aktsia; there were no mass slaughters, but there were no days without a quick execution carried out on individuals or a few Jews. The least reprimand, the smallest ostensible offense was enough to receive a bullet in the head from behind. Once, Rommelmann verified if children or the old from ghetto A had entered the ghetto for workers. He came upon four non–working women: Landman, Miler, Jakubowicz and Czeliborska [Zheliborska] (the later from Wloclawek). The bloody hangman shot all four women on the spot. Woe to those who did not appear at their workplace. They earned only one punishment, immediate shooting.

The Jews of Tarnow had grown accustomed to such individual executions for robbery and theft. If only it had stayed like this. The Jews went to work in fear and with broken hearts, praying quietly and with [silent] tears because they were not permitted to cry and to pray; everyone was feverish with the thought: when would another deportation occur?

Only a group of young members of Hashomer Hatzair did not submit and prepared to take revenge, to stage a resistance: Shmulik Szpringer, Riwek Szisler and Moniek Eksterman. They gathered weapons, bought for money, given by very trustworthy people in the ghetto. The idea to organize a Jewish underground with its own fighting organization also developed. The Straus brothers, who escaped from the ghetto during the later deportation in October 1943 but perished on the road, and Samek Szmidt [Shmidt] who during the third deportation forgot about the Aryan identity card he was carrying and was shot on the spot by the Germans, belonged to the group of young people who wanted to challenge the bloodthirsty enemy.

[Page 858]

Yosef Birken, already mentioned, writes about the exploits of the shomrim group in the Tarnow ghetto in Mosti (number 4, December 1947, Lodz):

“Meanwhile the shomrim group in the ghetto consolidated. As a reserve officer I taught the young men how to use weapons and conserve them. In December 1942, a conspirator entered the workplace and was searched for by the Gestapo. I left the ghetto. Thanks to the female liaison officer, Kataczina H. and Yosek Koch, I maintained constant contact with the group from the Aryan side. At that time I received a letter from Yosek Bruder in which he shared with me the information that he had received three kilos of “macaroni,” which meant three pistols, bought from an Italian soldier. In September 1943, knowing that the granatowa police had received an order to concentrate itself in the ghetto in the city, I warned the group about this. In the letter to the young men, I asked them not to lose their equilibrium during the crucial moment and to not let themselves be dispersed. According to the plan, I needed to wait for five evenings for the young men at a predetermined point for us to try to get into Hungary. The day of the liquidation of the Tarnow ghetto arrived. No one appeared at the agreed upon place. I received a letter on the third day of the aktsia from Melekh B. with the help of the female liaison officer with approximately this content: ‘We are apart. Giza and the child are alive. I am with an acquaintance in the city of Ratowo.’ I immediately contacted Motek Kurc, a coworker in the R.P.Z. [Rada Pomocy Zydom – Council for Aid to Jews] in Krakow, who came with ‘papers’ for Melekh in the morning. But he did not find him in the hiding place. He learned from the owner of the hiding place that Melekh had left for the village to hide (where, incidentally, he perished). I only learned about the group several weeks later, that they had waited out the aktsia and about a week later they left for the forests and perished there.

Y. Birken said, “After the liberation I met K. Kuperwaser, the only one in the group who survived. He told me about the fate of the Tarnow Shomrim group. They left the ghetto under the leadership of Yosek Bruder and went in the direction of the Hungarian border. On the third day [of the aktsia] the group had to withdraw from Tarnow to about 20 kilometers to the south of the city, to the forest outside of Tuchów. They set up a tent in the forest in the evening and not being careful they lit a fire and, like in the good old times, sang songs late into the night. Then everyone went to sleep, leaving a young boy on watch. When it started to rain, the guard hid in the tent and probably fell asleep. At dawn the group was unexpectedly surrounded

[Page 859]

by an S.S. division that had been ordered to open fire on the tent. All of the young men there perished, with the exception of three who, using their weapons, broke away from the surrounding S.S. men. Two of them, wounded, dragged themselves outside of Tarnow, where they perished, first shooting and wounding several Germans. Only Kuperwaser was successful in returning to the Tarnow ghetto. The group was betrayed by a forest overseer who informed the Germans of the presence of the Jewish partisans in the forest.

Thus, the young shomrim from Tarnow, proud and courageous young men armed only with revolvers, wanted to destroy the Tarnow ghetto in an unfortunate struggle with the armed and detested enemy [which ended in their] tragic death. Not wanting to be led like sheep to the slaughter, they killed more Germans before they died. The last deportation, aktsia came too soon for them. They did not yet have enough weapons to take on open struggle. However, even then when they broke through the surrounded ghetto and set up tents in the forest, they did not think about the danger that faced them. Drunk with the freedom they had obtained, they sang shomrim songs. They did not perish suffocating in the cattle wagons, were not shot by the Gestapo in the street and were not burned in the gas ovens. Before going to sleep they sang shomrim songs, not sensing that they were singing for the last time. And the three young men who broke through did not cry or beg that they be given their lives, but shot the Germans with their last breath, wounding them and perishing as true heroes. Honor and glorify the Tarnow Jewish fighters who perished!

Need in the ghetto grew even greater; foreign currency and jewelry were exchanged for bread, although those with [these resources] became even fewer. Those who worked helped the hungry in ghetto A. Holender, Wolf Weksler, Yisroel Glocner [Glotsner] and other Jews, hearing of this, continued to help those arrested. On Passover 1943, those working were given potatoes and beets and they gave it all to the three above – mentioned Jews who were involved with helping others. However, the opportunities to provide help were very limited. The few who had not yet dropped their hands and fallen into despair tried to save themselves in the ghetto if possible, but they also became doubtful and helpless because of the hopelessness

[Page 860]

of obtaining the most minimal means of help. This was difficult work because the number of those suffering from hunger increased every day.

The ghetto Jews, caught in a vise, took account of the fact that they were condemned, waiting in the ranks to be lain in mass graves. It is no wonder that in such a spiritual depression there were many cases of suicide. They had taken place earlier, during the second aktsia. Among others, the woman Antonina Edelsztajn [Edelshtein], a quiet, genteel communal worker, who was very active over many years in the philanthropic society, Beis Lekhem [bread for the needy], took her life. Her daughter, Dr. Berta Edelsztajn, also took her own life.

Mrs. Gryn, an active W.I.Z.O. [Women's International Zionist Organization] worker, Mrs. Szif [Shif], who could not bear the death of her husband after the first deportation, took their lives during the third deportation aktsia. Those who had no more strength and possibilities for living committed suicide and there were many such as these…

In the middle of August 1943 the bloody hangman Amon Goeth, hauptsturmfuhrer [paramilitary rank of captain] of the S.S., came to Tarnow. He was entrusted with the liquidation of the ghettos in Tarnow, Bocnia, Przemysl and Rajcza. His appearance in the ghetto was a portent of a new slaughter, fresh deportations, although in the beginning it was not clear what role Amon Goeth would actually play. This tall, thick murderer would stroll around the ghetto. He probably was working out the precise plan of how to annihilate the ghetto with the help of the black–uniformed Ukrainians, Latvian fascists, members of the S.S. and other scoundrels who were not lacking in Tarnow itself.

A tumult, distress, arose in the ghetto. They quickly began to build bunkers; every concealed spot was used for a hiding place – in attics, cellars, chimneys. Trembling, they waited for the incoming storm. But the bloodthirsty Goeth did not deceive them with his plans. This time, Goeth's annihilation was to be complete and final. Therefore, he endeavored to confuse the Jewish population by calming them and saying the Jews just needed to be taken to a work camp. He wanted to gain the trust on the part of the Jews with his invented stories to carry out his bloody aktsia more easily. The hangman prepared for the slaughter methodically, systematically and made sure that no one would disappear from the ghetto.

[Page 861]

Again very early on a Thursday, the second of September 1943, the German military and Latvian fascists circled the ghetto, covering it with machine guns. The fencing that divided the ghetto into two parts – A and B – was removed. Jewish policemen went through the houses and announced that all of the Jews were being brought to the Plaszow camp. Therefore, they needed to pack their most important things and prepare for their departure. The bolder ghetto residents left for Magdeburg Platz where the command of the Jewish police was located, to receive more details. At around seven in the morning, Amon Goeth himself came to the square. He was approachable and mild then. He permitted the Jews who gathered around him to ask where they were being taken. He answered everyone with the assurance that they were going to the Plaszow camp and that they needed to take all of their valuable things, particularly clothing and jewelry because they would be useful to them in the camp. Goeth was not only a murderer and executioner, but a simple swindler and thief, who took expensive objects for himself from the ghettos. As a result he was arrested by the Gestapo in September 1944, because he had not shared the Jewish possessions he stole with other German murderers, as he should have. Now, he stood in the Tarnow ghetto,

|

|

| The house on Magdeburger Platz where the command of the Jewish police was located |

[Page 862]

convincing his victims to take their jewelry and things of value with them. He wanted to murder them and be their inheritor.

This time, the non–working Jews in ghetto A, for the most part, were not fooled. They hid, hid themselves in the ground, wherever they could. This was their only hope of temporarily saving their lives. Those not working did not have the least trust in Goeth's assurances. They hid en masse in previously prepared bunkers. Whoever did not have a prepared hiding place disappeared into the municipal sewers.

It seems that the Germans were afraid of a resistance. Over 10,000 Jews had been assembled that day in Magdeburg Platz, almost all of the residents of the Tarnow ghetto. As a certain Berek Figa, who appeared as a witness in the case against Amon Goeth, tells it, Walnoszczi Square was well fortified with cannons and heavy machine guns placed around it . The Germans and Latvians were armed from head to foot.

The unskilled workers, employed in Maszczic were the first to march to Walnoszczi Platz, then other groups from the firms: Ostban, Madritsch and others. Amon Goeth himself, the murderer, watched to be sure that the people stood according to the labor workshops with a separate sign for each firm, five, four and three in a row. Yes, the Germans have a love of order. Even the preparations for sending people to their death had to go orderly, according to a plan and system. The groups of those working marched by Goeth in military order, with their chests stuck out to show the hangman their ability to work and good physical condition. The selection took place. All one had to do was move a finger; it took a second to determine if the person should remain alive or go to the transport that this time would take them to Auschwitz. Now it became clear why those who worked had been permitted to bring their children with them. All of those who had children with them were thrown in the second group – those not working. Realizing what this meant, a number of those working tried to hide their children in backpacks, valises, packages. They wanted to smuggle them out in various ways.

The selection lasted all of Thursday. Goeth chose 300 healthy, well–built young people from those working – 200 men and 100 women – for the “clean–up column,” to work in the liquidation of the ghetto. Goeth separated about 3,000 Jews to send to the Plaszow labor and death camp. Those remaining – numbering about 8,000 – were chosen for the crematoria in Auschwitz.

[Page 863]

Thousands of Jews again were driven to the Tarnow train station. The transports were driven in cars the entire day and the whips and rifle butts incessantly were brought down on the heads of the unfortunate ones. The bloodthirsty Goeth now filled his role; the drunk members of the S.S., the black [shirted] Ukrainians and the Latvian fascists helped him in his irrational impulses. Such a case of Goeth running wild is described: “In the Walnoczczi Platz, the bride of a furrier Batist, one of the “fortunate ones” who was chosen for the “clean–up column,” went up to him and asked to be permitted to remain with her groom. Goeth refused. When she again repeated her plea, she received a bullet in her head from behind instead of an answer.

“I stood with the tailors in the first row. Goeth approached and asked if I was a pre–war tailor. I answered, yes! Goeth said, ‘Good!’ My friend Szpiler stood near me. Goeth asked him the same thing, but he was much younger. He [Goeth] took him by the hand and led him to the fence and fired. Szpiler was frightened, fell, but nothing happened to him. Goeth laughed to his colleagues and left. Later, I saw Goeth order a woman to go to the front. She did not know where to go; he drew his pistol and shot her on the spot.”

Meanwhile, the Germans and Latvians finished their annihilation work in the Tarnow ghetto. They ran through the ghetto alleys with bloodhounds looking for bunkers and hiding places. Hundreds of the hiding Jews fell into their murderous hands and, if they were not shot on the spot, they were taken straight to the train station. Those who were hiding in the sewers gave themselves up. Not being able to bear the smell and the poisoned air, they asked passersby if the deportations had already taken place. They did not know that the German soldiers lay in wait for them. Most were dragged out of the sewers; many of them were shot on the spot. The remainder were stuffed into the train wagons like cattle on their last trip, to Auschwitz. Hundreds of dead now lay in the Tarnow ghetto. Blood again flowed like a river.

Approximately 8,000 people designated for the Auschwitz gas ovens were chased to the train station. Freight wagons [box cars] were already there, into which 170 people were pushed, where there was only room for 40. People fell while still at the station,

[Page 864]

pressed together, beaten, suffocating in the narrow wagons spread with lime. At the above–mentioned trial of Goeth, Dr. Henrik Faber stated that this train took approximately 8,000 Jews which increased on the way with another 2,000 Jews from the Bocnia ghetto, arriving at Auschwitz with more dead than alive. The witness, a doctor in Auschwitz, had to receive the transport. Seeing the large number of dead who fell out of the wagons, he motioned with his hand and left. According to the statement of Dr. Faber, only one person, a certain Wilhelm Sztern [Shtern], who jumped out of the train wagon through the window, survived the transport.

Those who were to be sent to the Plaszow camp were loaded into separate wagons. They were given such “mild” treatment that only 95 men were stuffed into each wagon. The remainder who could not be taken by the wagons remained in Magdeburg Platz all night. On Friday morning, they were taken to the train station. They were not permitted to take their children with them. During the selection, Goeth removed from the ranks all those who worked and had children with them. The despondent mothers and the unfortunate fathers tried to hide their infants in the packs, knapsacks, valises – who wanted to separate from those most dear to them? The infants instinctively sensed the threatened danger. Pressed together in a backpack or a valise, such a child lay quietly, did not cry or groan so as not to betray himself to the German murderer. Fathers and mothers who were in the wagons with their hidden children breathed easier; finally the danger had passed. They did not know that according to Goeth's order, all of the Jewish children in the Tarnow ghetto were to perish on that day. Shocking scenes played out at the train station. The small number of surviving witnesses of those tragic events, those who went on the road to hell to Plaszow, described these events at the trial of the human murderer, Amon Goeth, before the highest national tribunal in Krakow.

The witness Mendl Balzam, designated for the transport to Plaszow, waited at Walnoszczi Platz on Thursday night before Friday. On Friday morning among others, he and his group were at the train station. The witness stated: “When everyone was loaded, Goeth approached each wagon and announced that if a child was found in a given wagon, everyone in the wagon would be shot. A great commotion began and they began to give out the children. The ordnung's man [security man], Cymerman[3]) entered

[Page 865]

the wagons and extracted 40 children and their parents. All of the children were taken away in vehicles by the Gestapo.”

Not all of the mothers wanted to separate from their children. Several left the wagons with their children and were loaded into the autos. What became of these mothers and children? Where did the vehicles go?

We learned of this from the witness testimony of Leon Lezer (now in Israel) at the above–mentioned trial. His “good fortune” was that he was assigned to the “clean–up column” and, therefore, he and his group remained at Magdeburg Platz. In his testimony the witness described a shocking picture of the bloody execution of the unfortunate children and parents pulled out of the train transports that the murderer Goeth carried out with his own hands. The entire group that was assigned to clean up the ghetto after the last deportation was sealed into a carpenters' barracks that was located on Magdeburg Platz opposite a small alley in the ghetto that connected the autobus square (Magdeburg Platz) with the hospital street near Kacner's [Katsner] house. As the windows of the barracks looked out onto the alley, the witness had the opportunity to observe everything that took place in Tarnow on the morning after the liquidation of the ghetto:

“Everyone left the ghetto,” Leon Lezer said, “the others chosen by Goeth remained on Magdeburg Platz. Goeth rode to watch the loading of the Jews in the train wagons, gave an order and we were sealed off in the carpenters' barracks. When Goeth returned to the ghetto, I noticed that a young boy approached him and said something to him. Goeth immediately got into the vehicle and drove out. Half an hour later, a covered truck arrived, Goeth's private vehicle after it. At first I saw a man, a woman and two children get out of the second vehicle [the truck]. There was a small, closed alley opposite the window at which I stood in the barracks. He [Goeth] told them to go into the alley, and shot them all with a series of bullets. He again ordered four people to leave the truck, again a woman with children, told them to go on top of the previous victims and shot them. Thus, up to four victims continued to leave the truck, some 40 or 50 people and Goeth himself shot all of them. A number of victims were still alive, lifting hands, feet. He [Goeth] was so tired that he took off his hat and wiped the sweat from his brow. Then he asked to be brought a bowl of water and washed his hands. He was in the company of another Gestapo

[Page 866]

member. The members of the Gestapo ended it for those who were still alive. This happened on Friday. All of the workshops had to be taken apart. Goeth removed all of the locksmiths from our column. He also called me out and gave an order that the entire locksmith shop had to be dismantled within two hours. Goeth himself waited until all of the trucks were loaded onto the same train with which the Jews were to travel to Plaszow. He was in a great hurry because he wanted to go to Krakow. We loaded everything with the people and when everything was ready to go to the train, Goeth left Tarnow.”

The same Leon Lezer, giving his statement to the historical commission in Krakow, additionally stated that among the victims he recognized was Dovid Mesinger, a goldsmith from Tarnow, 33, and his wife and child. All of the “clean–up column” then had to gather all of the dead bodies, load them into wagons and Gestapo members watched that they did not search all of the pockets and take those objects they found. They even told them to remove the better clothing from the dead.

Also watching this bloody spectacle was Mrs. Erna Landau, who was at Magdeburg Platz on Thursday, the first day of the deportation, in the group that was sent to Auschwitz. She succeeded in moving away from this group unnoticed and hid in a bunker that was located in the previously mentioned small alley. In her testimony at the trial against Amon Goeth, Mrs. Landau stated, “This was a small house in which there was a small attic in which we successfully hid ourselves. I took out a roof tile to [create] a window. What took place in the alley was unimaginable. Thus, I sat in the small attic for all of Thursday, day and night. Friday morning, Magdeburg Platz was completely empty; it was quiet there. Suddenly I heard a roar of vehicles. I was afraid because the vehicles passed in front of the house where I was hiding. I took a look and in the vehicles sat the Germans who were familiar to me – Blache, Grunow and Goeth. Ikla and Kastorius were also there. I heard: Lasse! Herous! [Go! Out!] Several people left the truck. Goeth led them and shot one of them. Then he told the second one to stand on the dead and shot again. He himself, standing near the victim, shot. A six–year boy was among the others. He was afraid and ran away. Goeth called him: “Come, come do not be afraid!” The child took a mirror and other trifles out of his pocket. With a smile, Goeth took the child's things in one hand and with the other shot

[Page 867]

the child. Mrs. Walz and her six–year old and eight–year old girls were there. He shot them all. When he left, he was brought a bowl of water. He washed his hands and his comrades ended [the lives] of the others.”

Mrs. Landau, who saw Goeth shoot the wife of Yehezkiel Klophalc [Klophalts] in the street, stated that in this street Amon Goeth himself shot 54 people, mainly women and children.

This was how the bloody hangman, Amon Goeth, parted from the Tarnow ghetto. This animal in human form condemned to death by the Polish Supreme National Tribunal on the 5th of September 1946, still asked for a pardon by the President of Poland. A criminal asked for a pardon from the prosecutor, Mieczyslaw Siewierski, in the highest court, who in his closing speech at the trial against Amon Goeth, designated him as a man whose image in life grew into a legend as the embodiment of evil and cruelty, bestiality and cunning as the contemporary personification of the biblical devil. An individual without any moral scruples, who did not differentiate between good and evil, did not have any feeling of pity because he lacked any feeling of mercy.

The presidium of the National Council of Poland – then the highest jurisdiction – did not grant him his amnesty request and on the 13th of September 1946, the human murderer, Amon Goeth, went to the gallows.

Was the death penalty sufficient for the crimes that Amon Goeth committed? We will permit ourselves at this point to repeat the words of the prosecutor of the Supreme Tribunal, Dr. Tadeusz Cyprian, at the end of the trial against Amon Goeth. Among other things, the prosecutor said:

“The accused can only pay for these deeds with his life, that is with everything he possesses.” Let us also repeat the words of the same prosecutor that characterize Amon Goeth's murders of humanity, murders that extend from that glove that he removed from his hand after shooting 50 people in the small alley in the Tarnow ghetto, through aiming blows at a child who is considered untouchably sacred to all of the nations of the world, to the mass extermination, to the murder of men. This crime against humanity – the prosecutor, Dr. Cyprian underscored – is not only an expression of the internal impulses of the accused. It is a sign of the spirit that ruled the nation that produced the accused, a people who

[Page 868]

will now need to suffer for these crimes if historical retribution will be a just one. The Nuremberg trials revealed the complete moral decay of the German people, revealed the cases from which stem the tendency to benefit from, to have power over the dead bodies of people and nations. Some day history will combine the information from all of the trials and create its synthesis and give us a picture of the decadence of a once great people, a people who fell deeply, so deeply that it will not be easy to rise up, if it will want to raise itself from this decadence.

A day before carrying out the sentence of Amon Goeth, Janina Wiezbowska wrote in the Warsaw daily newspaper, Glos Ludu [Voice of the People] (4.9.46 number 243) that “Amon Goeth will be judged today for the anxiety of death of those who lay on their deathbed in pain, for each spasm of those who scratched the earth in their last shudder, for those stiff–with–fear hearts of mothers, for the fear of fathers, for the shame of their daughters, for every drop of sweat that ran from the weary bodies of those who did superhuman work, for the unlived lives of those children who fell into his hands. And with him is judged the system that, because of satisfying the unlimited arrogance of one race, washed an entire people from the earth's surface and turned men into beasts. And with him also is judged every criminal idea that arms blind hands with weapons or with stones and plants seeds of all kinds of hatred in the dark, politically unaware brains.”

The liquidation of the ghetto was not yet complete. There were still sick people in the Jewish hospital. The Gestapo carried out a bloody action against them. The Gestapo shot all of those who were seriously ill. There were no moderately ill people in the hospital. And to end the bloody spectacle, the German beasts drove 450 Jews who were caught in various hiding places to Widok Street; everyone was shot and then they were burned on campfires.

Meanwhile 300 Jews, assigned to the “cleaning column” whose task it was to clean up the ghetto, erasing the traces of the crimes, gathering all of the remaining Jewish items – Judengut [Jewish possessions] – remained alive. Those in the group lived in two houses at Walnoczszi Platz – at Szpitalna 13 and 14. These two houses were now a sealed off area, the last “Jewish quarter” in

[Page 869]

Tarnow. When the workers from the “cleaning column” returned from work at five at night, the Ukrainian guards sealed them off in these houses so that none of the last Jewish arrestees would escape.

Little by little the remaining number of Jews in the Tarnow ghetto grew. Several days after the last aktsia, about 500 Jews left the bunkers. They now found themselves in a difficult situation because the Germans had precise evidence of the number of arrestees who were located in the two houses on Szpitalna Street. Those who returned from the bunkers were not on the lists of those belonging to the “cleaning column.” These were the illegal ghetto residents who were sent to Szebnie during the second half of September 1943. However, they never arrived there because they were shot in a forest on the way.

The previously mentioned Leon Lezer spoke about the last terrible acts of the German murderers in the emptied ghetto:

“Now, after the final liquidation, only our liquidation group and several people from the Judenrat (Folkman, Lerhaupt, several officials and security men) remained. The Germans now began to search for bunkers and almost every day discovered such hiding places. The people were dragged out and shot on the spot. The Germans told them to lie down in a row, shot them, then told others to lie on top of the dead bodies, while those remaining who were waiting for their row had to stand and watch everything. There were women and children, young and old, defenseless compared to the armed to the teeth Gestapo members with trained dogs. Such actions often were turned into cautionary lectures for growing young Germans and the Gestapo would use this for educational purposes. Thus, Blache taught his two sons – one 10 years old and one 13 years old – when he pointed them toward a group of Jews who were discovered in a bunker – to shoot in the direction of these people. The father stood nearby and with a smile watched his son shoot and the Gestapo members shook their heads in approval and satisfaction.”

Thus, in the middle of September 1943, Tarnow remained with only a handful of Jews, sealed off in two houses, Jews who cleaned and brought order to the ghetto. The dead, empty ghetto cast a terror with its emptiness.

At the end of November 1943, 150 people in the “cleaning column” were sent to Szebnie. They were no longer needed because the work in the ghetto was finished. They already had cleaned out

[Page 870]

the dead; the stolen Jewish possessions were taken to the German warehouses.

The remaining, last group of Jews, numbering 140 men, sat in the two houses awaiting their fate in fear. They began to plan their escape. Blacher [referred to as Blache in the remainder of the text] and Kessler observed them well, particularly after the Jews themselves had been observing each other because they knew that in case one escaped, everyone was threatened with being shot. No one in this group was permitted to keep anything of value; even wedding rings had to be given to the Germans.

In time the Gestapo murderers finished in a pitiless manner with the members of the Judenrat who had served them so loyally throughout the entire time. Josef Fast and his wife first were beaten and then shot. Lerhaupt, the vice chairman of the Judenrat, who more than anyone, observed the Jews in the ghetto, was shot at Auschwitz, right before the end of the war.

When the ghetto was cleared, when they gathered the stolen Jewish possessions in the German warehouses, this last group also was annihilated by the executioners Ash and Blache. A small number of Jews who remained in the Tarnow ghetto at the very end were taken to Plaszow, on the 9th of February 1944.

Tarnow became Judenrein [free of Jews] in February 1944.

Jewish Tarnow ceased to exist. Forty thousand Jews, who lived in Tarnow at the start of the war, perished al kiddish haShem [in sanctification of the name (of God) – as martyrs].

Translator's notes

by Dvoyre Abramovitz–Horwitz

Translated by Miriam Leberstein

By way of preface, I want to say that I very infrequently, almost never, remember dates and numbers; the divisions of time based on the calendar have been erased from my memory. I only remember seasons like fall or summer, the weariness of a day, or the darkness of a night. Only in this way have the images remained – images of blood, sickness and death. But there is one date that I do remember well – September 1, 1939, the date that marked the beginning of the end, when life stopped, said goodbye, and left.

The night before, we were standing in front of our house. The town of Tarnow was dark, extinguished. Not far from us, in the coffee house across the street, several people sat by candle light (lamps were no longer being used). The windows were curtained and you could see only shadows, silhouettes, on the walls. It looked strangely sinister, already a portent of the great final event that was about to engulf the entire world.

The next day, things were in an uproar. The pharmacy was packed with people buying supplies, gas masks and other items of protection in preparation for bombing and gas attacks. (The big Moshtshits ammunition factory was near Tarnow and people were sure that the town would be the first to be blown up.) We didn't know then that the Germans would invade Galicia without a struggle, as if it was their land. No one knew this and their preparations were extensive. People also stored up food, candles and other items. I sewed a small gas mask for my child, who was then five months old. It was an odd gift for his young, newly begun life. My husband Buziek received a summons to report for military duty and his parents had already run away to Tarnobzheg (Dushikev), a small town right on the Vistula.

[Page 872]

Helpless in the middle of all the commotion, knowing that Buziek had to go away, I quickly packed a few things and decided to go to where my parents were. Buziek accompanied us as far as Melitz. The buses were packed with refugees. While we were travelling, German airplanes were flying quite low over our heads, not considering it necessary to waste a bit of gunpowder on us. The Jews thought they weren't even German planes.

Even more refugees boarded the bus in Melitz. My husband and I said goodbye. One last look at me and my child, and then we let him go, off to the Polish army, even though everything had already been lost. I remember his last glance. Life was gradually slipping away.

We arrived in Tarnobzheg. Our former home, my father's house, had been seriously damaged during the war of 1914, but several other houses were still standing, where my brother was living. That Saturday was a golden autumn day. I sat with my child in the orchard, with its big, thick trees, and every stone reminded me of my childhood and of my former home.

Suddenly, in the evening, the sky was in flames, the town covered by a hail of bullets, one blast of thundering noise after another, red flames and black smoke. It felt as if the earth was trembling. We went into the front room, so that we could run out if the walls fell in. The big lamp in the middle of the room fell down and broke into pieces on the floor, and we cried out our first Shema Yisroel [prayer traditionally said as a Jew's last words].