|

|

|

Drawn By Leib Fufiski–Ent

|

|

Shimon Kantz Translated by Janie Respitz ––Just like Sventzian, New – Sventzian did not possess high mountains, deep valleys or rushing waters. Some large stones, and some lonely small stones could be found on the shore of the Zemya River. The people were similar to the town, simple, hard working with the worry of bread on their brows. Most followed the Rabbinic tradition (Misnagdim), but even the Hasidim didn't stand out. Their Jewishness was calm, sensible, without great pretensions, but without any dissension. Throughout the generations the Jewish life in New – Sventzian took its own route, quiet, slow and assured, in Jewish and world affairs. But, anyone who would dare attack the national dignity, would face vigorous opposition, which came to be in every aspect of Jewish life. Among the thick pine trees of the old Sventzian, New–Sventzian was born. Common worries and joys, economic, cultural and family issues brought the old and New – Svenztian together. The “New”, brought its own colours to the existing way of life. New –Sventzian possessed its own original dynamic. The train line from Petersburg to Berlin brought currents of renewal, energy and courage that was mirrored in the stubborn struggle that New –Sventzian waged for national rights during the German occupation during the First World War; for the right to continue with Jewish cultural life. This is how the Jews of New – Svetzian defended Jewish national autonomy during the rise of the Lithuanian state; it was like this during Polish rule as well. Yiddish and Hebrew schools were founded. For every new Jewish cultural event, the young activists added another brick to the cultural building. In the worst of times, when the Jewish youth did not know where to turn, and ran wherever their eyes led them, those who remained stubborn, stood alongside the religious students and psalm sayers, and shackled themselves to the golden chain of modern Jewish culture, while staying close to the source with a lively, juicy, exuberance. A quiet melody accompanied them, like a pale premonition of the impending catastrophe, but they did not stop being drawn to the bridge that connects the past to the future, and move from the old the new with respect for the connection to the greater ideal, with hope for stability and continuity. The majority of survivors emerged from this group, who are today erecting the memorial for our destroyed town. |

Heshl Gurvitch

Translated by Janie Respitz

|

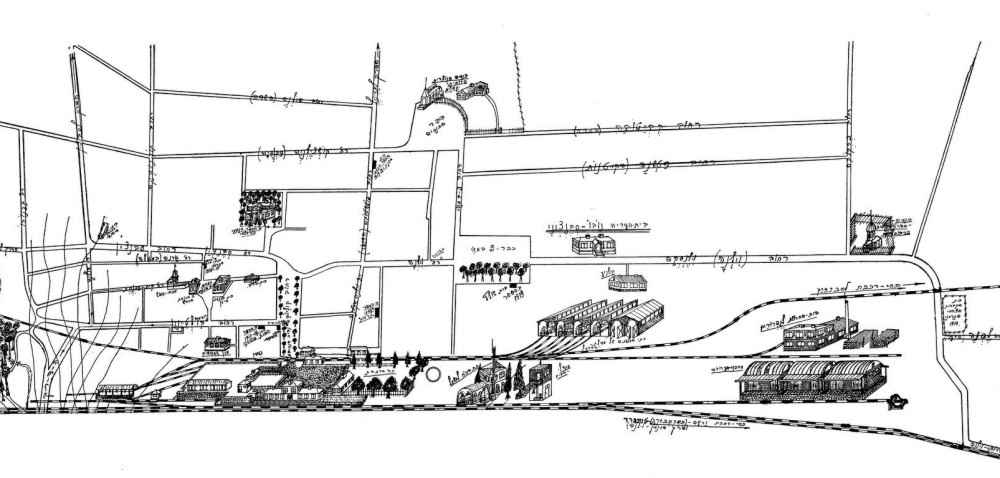

The road from Vilna to the two capitols of Russia, Moscow and St. Petersburg ran through Niementchine, Podbrodz, Sventzian, Daugelishok, Vidz and Dvinsk. In 1861 when they began to build the St. Petersburg – Warsaw train tracks, for various reasons the route was changed. The residents of Niementchine and Sventzian were afraid of the train and tried through various means to have the train travel through another route.

Therefore, the railroad cut through other area between Vilna and Dvinsk, for example, Novo – Vileyke, Bezdan, Podbrodz, Ignalina, Duksht, Turmant and Kalkun.

Thanks to these new train stations, the open areas where there were pine forests, rivers and lakes, began to breathe new life. Slowly the stations attracted people and towns were built around them.

This is how, 10 kilometres from Sventzian, 72 kilometres from Vilna and approximately 80 kilometres from Dvinsk a new town was built which was called “Novo – Sventzian” or as the Jews called it in Yiddish “Nay – Sventzian”. (New–Sventzian).

A new life began to emerge around the train station: the workers and officials that came from afar brought their families. The government gave them plots of land on which they built houses and settled permanently.

A few years later, Jewish families began to settle, arriving from surrounding villages and small towns. The Jews opened taverns, stores and handicraft workshops. A few Jews found work at the train station.

The land the town was built on

[Col. 646]

belonged to the nobleman Svirzhevsky. He lived on a beautiful piece of land on the road to Sventzian. The Jews leased land from him and built their first homes. This is the reason, in later years a large part of the town belonged to this nobleman's inheritors.

Besides this, many Jews built homes on land that belonged to the government. They had to write their contracts with a Christian name as in those days it was forbidden for Jews to lease land which belonged to the government.

The town was being built from the east, north –

[Col. 647]

South side of the train station. The main street in the centre of town began at the station and was called “Train Station Street”. Later – under Polish rule it was called “Koloyove Street”.

Left of the station was the road which led to the towns Kaltinian and Lingmian, then Kaltinian Street was built. Further on, also on the left side, near the prayer house, was the Shul Street.

From North – East, on the road to Sventzian, Sventzian Street was built. On the south side, right of Train Station Street was the road to Podbrodz and Vilna. There they built a long beautiful street with trees planted on both sides. It was called: Vilna Street.

From the west side stood the train tracks and the Zhemaniye River. At the end of Vilna Street were the majority of the “Dachas”. Almost exclusively Christians lived there. Train Station Street and Kaltinian Street were Jewish streets, with a few

[Col. 648]

exceptions: on Train Station Street there was a Christian food store which belonged to the Tsibulsky family.

On Kaltinian Street there was a Christian house where the family of the train worker Slavinsky lived. His children spoke a good Yiddish and lived well among the Jews.

The Make Up of the Population

The population of New–Sventzian was comprised of Poles, Lithuanians, Russians and Jews.

The Non – Jews mainly worked with the railroad, as officials or workers. The Jews worked mainly in business and trade. Only a few worked at the station.

The first Jewish families to settle in New–Sventzian were:

|

|

[Col. 649]

|

|

Slowly the population grew and in the last years left a lasting impression on life in the town. Almost all the business and inns were in Jewish hands.

The Christian population held the most important positions at the train. As the soil around the town was sandy and not very fruitful, the farmers in the surrounding villages were very poor. This is where the majority of Lithuanians lived.

The Economic Life

New–Sventzian was founded thanks to the train station and continued to grow and develop together with the station.

After a few years the New–Sventzian station became one of the biggest on the Vilna – Dvinsk line. All the fast trains traveling to and from Berlin to St. Petersburg would stop, besides Vilna and Dvinsk, in New–Sventzian. The importance of the station increased in 1896 when a small train line was added linking Sventzian to Lintup, Haydutzishok, Postov and Gluboke.

A short time later a link from the other side was made with Kaltinian, Utian, Aniksht and Panyevezh.

The town became an important connecting point between White Russia, Russia and Lithuania to central Poland and Germany.

All the head offices, workshops and depots of the small – train were in New–Sventzian. The town took on the role of an important place of work.

The sound of the siren at dawn woke all the workers from their sleep; mid–day the siren sounded when it was time for lunch; in the evening, when the workers heard the siren, they left their workshops and went home.

Early in the morning the streets of New–Sventzian were filled with workers, employees, machinists, controllers, in their dirty work clothes, walking to work.

Unfortunately, there were very few Jews among them. Moishe Zaydl was the only Jewish official on the train and Shoykhet was the only Jewish machinist.

Shoykhet was considered the best machinist. When the small train went by quickly – up hill

[Col. 654]

to Panyevezh, everyone knew Shoykht was driving the locomotive.

Inns, Hotels and Wedding Halls

Because New–Sventzian was an important hub, the train station was always filled with people. The two large waiting rooms and the buffet were filled with travellers from morning to night. The first class passengers were served at tables with elegant service. That is where the rich people sat.

Third class was for the simple, poor masses. All trains stopped in New–Sventzian and all the passengers would disembark to buy something to eat and drink.

The train station also attracted the locals who liked to take a walk there in the evenings, on Shabbes or whenever they had free time.

Everyone was curious to see the passengers passing through; the wealthy, well dressed men and women from the well–lit sleep coaches and especially the lovely restaurant car. Walking at the train station gave them the opportunity to see people from the big, outside world. This left a huge impression on the population of New–Sventzian. It raised their own standard of living and created a big difference between them and the people from surrounding towns.

The Jews of New–Sventzian became more sophisticated. People from the area referred to them as stuck up.

In 1901 a big fire destroyed practically the entire train station and a large portion of Kaltinian Street. The residents rebuilt their homes, now out of brick instead of wood.

Among these new, nice brick buildings were inns, hotels and especially wedding halls.

The development in this area was interesting. Due to a various reasons, passengers often disembarked at our station and stayed in our town for a long period of time.

[Col. 655]

|

|

| A portion of the Train Street. Right: to Vilna Street; Left: to Sventzian Street. Right: Mordechai – Yose the ritual slaughterer's house. |

Merchandise passed from one train to another: because of the diverse business in lumber, geese, crayfish and fruit, agents from important firms would come to town as well as important businessmen. Besides this, the small train would often be delayed requiring passengers to wait for hours at the station.

This called for a need for hotels and inns, providing many Jewish families with a nice income. The nicest hotels belonged to: Avrom or Dobeh Noyme Pruzhan, Abba Gorfayn, Avrom Yitzkhok Tcharnebrodky, Elia Yose Kavarsky, Eliyhau Gershon Zak and Boyershteyn.

Before the fire the town was a place for matched weddings.

At first they took place at Yose the Innkeeper's, whose house later belonged to Elia Yose Kavarsky; At Shmuel Abba Smorgansky's, Avrom Mordkhi Azhinsky and in the last years at Abba Forfeyn's and Boyershteyn's. These weddings brought a lot of money to our town. This influenced the standard of living and the development of our society.

As a young boy I sang with cantor Shulman

[Col. 656]

(an uncle of the famous Kusevitsky) and because of this, I had the opportunity to be at many weddings. The beautifully set tables and the fine food mad a huge impression on me.

The Railroad Work

Jews were involved in the repairs and work on the trains like; tin smiths, painters, glaziers and especially “purveyors”. The first to work as a glazier, painter and Purveyor was Shmuel – Nokhem Kovarsky.

He had a large family, sons and sons–in–law who all worked around the trains. At first they worked with him, and they became independent entrepreneurs.

The Kovarsky family “ruled” the entire length of the Vilna–Dvinsk line, also running the stations at Kovno, Verzhbolove – Aydkunen at the German border.

Besides the family members there were also many hired workers.

[Col. 657]

All the materials and workers were concentrated in town and Shmuel –Nokhem Kovarsky provided a livelihood for many Jewish families.

Also working on the trains were: Khatzkl Levinshteyn the tinsmith and Yose Kovalsky and his sons who were carpenters.

The Lumber Business

As the entire area was surrounded by forests, a strong lumber trade developed in town. The lakes and rivers provided the opportunity to transport the chopped down trees over the Zemiane, Vilia and Nieman to Germany.

The lumber merchants would export wood by train to paper factories and coal mines in Germany and England.

Baranova played a separate role in the lumber industry in our region.

The Branaover forests began behind the Zemiane River at the edge of our town and went on for kilometres.

As Jews did were not permitted to buy forests from the state, the entire area of Baranova, deep pine forests were purchased using a Christian name by two Jews, Rogovin and Kovarsky from Minsk.

Baranova was 4 kilometres from town. The head office dealing with the exploitation of the forests was located there. The head of this office was Yudelevitch, who was tough and authoritarian. Because of his bad relationship with the workers, he was forced to leave Baranova during the 1905 Revolution.

The new manager who replaced him was Lev, who was a liberal man. The management of all the Baranova businesses lay in the hands of Rogovin's relatives. The cashier was Elkind and the office director was Friedenheim. Both lived with their families in New–Sventzian.

Almost all the employees, like record keepers, brokers, and entrepreneurs bringing the wood to the rivers were Jews. The town prospered from this economic activity; all the produce for the yard, for the employees,

[Col. 658]

woodsmen and foremen and food for the horses – was ordered from the Jews of New–Sventzian.

Besides the exploitation of the Baranover forest, the lumber merchants bought pieces of forest from various noblemen and chopped them down.

In Kaltinian, which was connected to New–Sventzian by the Zemiane and the Bay, the entire Jewish community worked in the lumber business.

The forest merchants from Kaltinian, Hirshe Kremer and Gershon Rudnitsky were considered big entrepreneurs in the region.

In New–Sventzian, those involved in lumber and forestry were: Avrom Rabinovitch, Khayim Leyb Segalovitch and Velvl Pupisky.

New–Sventzian was the centre of the lumber and forestry business in the region. The biggest buyers and exporters of lumber had their middlemen there.

Berries, Mushrooms and the Fruit Business

The forests of our region were filled with red and black berries and various mushrooms. The Christian women and children would pick them and bring them to town.

The local merchants would clean and sort the berries and mushrooms, pack them and send them to Vilna, St. Petersburg and Warsaw.

Hirshe Deitch had a large export firm in New–Sventzian which would buy these products from the surrounding region and export them to Germany.

Elia –Yose Kovarsky and Yisroel – Eliyahu Berman were in the same business.

Besides berries and mushrooms there was developing trade in other fruits such as cherries, plums, apples and pears which Jews would buy from local orchards and send to Vilna, St. Petersburg and Warsaw.

Fishing

The surrounding towns, particularly Lingmian and Kaltinian were surrounded by large lakes filled with a wide variety of fish. The Jewish

[Col. 659]

merchants leased the lakes from the government or the nobility, would sort the fish according to species, pack them in large baskets and transport them to fish markets in the big cities.

The biggest fish merchant in our area was Meir Gavenda from Lingmian. Yose–Leyb Solteisky was the fish merchant in New–Sventzian.

The brothers Feyve and Yitzkhak Volfson, the sons of Rokhl Faye Gordon provided fish for use in our town.

Crayfish Export

Crayfish was an important business. It was run by the previously mentioned firm Hirsh Deitch and sons. New–Sventzian was a centre for the crayfish trade.

On the road to Baranova at the edge of town on the Zemiane, the Deitch Company built a special sorting house with floating metal boxes.

They sold the crayfish in all the surrounding villages and towns and would bring them to New – Sventian on the small and big trains and in many wagons. They were packed in braided baskets lined with moss and sent by courier to Germany.

[Col. 660]

|

|

A few Jewish families were involved in the crayfish trade. Among them was Yosef Shteyn, a relative of Hirsh Deitch. Those involved in the transport of crayfish were: Meir Moishe Katz, and his sons Yakov, Velvl and Mates.

|

|

[Col. 661]

Geese

Our town was very involved in the Goose trade. Geese would be brought to us from the entire region and from deep in Russia. The Geese would be exported from New–Sventzian to Germany.

The geese were brought in special wagons. From the train station they were taken to special buildings where they were washed, cleaned and well fed. This process would often take days, sometimes a few weeks. New–Sventzian became the main transit centre of geese from Russia to Germany. The business was primarily run by Hirsh Deitch and his sons: Zalman Mendl, Araon and Avrom and his son in law Stanietsky.

Not far from Zemiane on Baranover Street they had large warehouses and special facilities. All their offices were also there and a nicely built building that was their home.

Things were always happening. Merchants would come from near and far. Many Jews would come to discuss their private affairs with Reb Hirshe Deitch.

Reb Hirshe Deitch was not only a great businessman and a scholar; he was also an ardent Hasid who loved to receive guests. His house and hand were always open to every Jew.

On holidays his doors were always open. On Simchat Torah there was a tradition in town. All the Hasidim, young and old would go in the evening to Reb Hirshe Deitch as if to a Rebbe.

Tables were prepared with all sorts of good food and drinks, and the Hasidim would celebrate, singing and dancing into the night.

Khatzkl Perutsky also had an export house for geese. Not far from the railroad stood

[Col. 662]

a two story building. The yard was filled with feed.

The managers of Khatzl's business were Shloimeh Maimon and Alter Berman.

Khatzkl's company also sold oil to the whole region.

A third centre for the goose business was Dovid Ryng, near the rail road. He worked with smaller exporters like Motl Gurvitch, Hamburg from Duksht and Gorfeyn.

Many residents of New–Sventzian worked in the Goose trade, providing feed and selling feathers.

Old things

On Baranover Street, in a blocked off area, were the warehouses of Yosef Shneur. This was a centre for selling and sorting rags, used iron, rubber, boots and bones. After sorting and packing the used goods would be shipped to factories in Russian and Poland. Just like Reb Hirshe Deitch, Yose Shneur was also an ardent Hasid, totally devoted to Hasidic ideology.

Ventures

Before the First World War there were soap and molasses factories in town that belonged to Reb Aron Tzinman from Sventzian. His bookkeeper was Averbukh who later moved to Vilna.

There was also a steam mill and a saw mill built by Vishnarsky and run by his brother–in–law Khayim Krasnoselsky.

Fishing Nets

Fishing nets were being fabricated in Sventzian and after the Polish take over a factory was built in New–Sventzian by Moishe Gurvitch, Moishe Elperin and

[Col. 663]

|

|

Right: Yitzkhak Elperin, Yitzkhak Gurvitch, his small nephew Shakhne Seated: Moishe Elperin, Khone Rutshteyn Standing left: Moishe and Esther Gurvitch |

Khone Rutshteyn. The factory employed 40 workers, mainly Russians and White Russians. A few Jews worked there as well: Nokhem Troytze, Yudl Troytze, Yose and Yitzkhak Elperin and Yitzkhak Gurvitch. There were also Jews supplying wool and selling. The factory was on Kaltinian Street.

The Meat Business

Most of the butchers in New–Sventzian served the local population. They included: Gedalia Zak and his son Motl, Ruven and Rafael Shutan, Moishe Yitzkhak Shutan and Shloimeh Bak. Only Leyb Troytze, who they called Blond Leyb and his sons Moishe, Dovid, Meir, Sholem and Nokhem sent meat to the big cities, particularly St. Petersburg.

Every Wednesday which was market day in Sventzian, Leybe and his sons would buy calves and cows and bring them to their large yard near their house on Kaltinian Street.

The same evening they would slaughter them,

[Col. 664]

skin, cut and pack them and send them by courier train to St. Petersburg. The next morning fresh meat would be sold in the market of the Russian capitol that was brought from New–Sventzian.

Shopkeepers

As there was no market in New–Sventzian, most of the revenue came from train officials, train workers and passengers. The surrounding region was poor. Sometimes carts were set up on Train Station Street, but there was no market as in other towns. The poor farmers did not give the Jewish shopkeepers much business. The train workers also did not shop in town. They had free train tickets and would often travel to Vilna where there was more variety and often cheaper prices.

This all impeded the growth of the shops

[Col. 665]

in our town. A lot depended on loans.

All the officials and workers would get payed at the end of the month. All month they shopped on credit and at the end of the month payed their debts, sometimes only partially, still owing money.

Some fine businesses opened in town. Most were on Train Station and Kaltinian Streets.

The nicest and largest stores were: Tzibulsky, Shneur Fingerhoyt and Yosef Kliot's food and delicatessen, textile stores owned by Yisroel – Eli Berman, Nosn Shapiro, Yitzkhak Kovarsky, and later, Dovid and Motl Milner; Iron shops of Khayim Yanishsky and Shimshon Berman; haberdashery and shoe store of Zalman Kovarsky and Taybe Gitl Ozhinsky; crockery store of Dovid Zeliviansky and Avrom Kovarsky; wheat business that was served by the coachmen that worked near the train and large forest trade. These stores belonged to Mendl and Beyle Perl Levin, Todres and Malka Shafton, Kalman and Raikhl Katz, Eltzik and Khaya Elperin, Yehoshua and Fruma Bitshunsky, Rafael and Gitl Shutan, Henekh Gurvitch and others.

A large wholesale business of flour was situated at the beginning of train Station Street that belonged to Sholem–Leyb Gordon from Ignalina and was later run by his son–in–law Hirsh Kizberg. A wholesale business of a variety of good was owned by Razavsky.

Other wholesale businesses were later opened by Khayim Gordon, Eli – Yosl Kovarsky and the brothers Heshl, Eliyahu and Leyzer Gordon.

Artisans and Workers

Thanks to all the train officials and workers in town, the Jewish artisans had regular work. There were shoemakers, tailors, blacksmiths, tinsmiths, glaziers, masons, painters, bakers…we can add the coachmen to this list.

The first shoemakers in town were Ezriel Bruslan and his son Etchik; Tall Yosl, Moishe Yose Kovarsky, Yose Malerovitch and Leybe Rudnitsky.

The best tailor in town, where the intelligentsia would go, was Mikhal

[Col. 666]

|

|

Mikhl Yukishsky on Vilna Street. Besides him, other tailors were Avrom Layzer, who later emigrated to America, Khone Yose, Blond Leybe's son–in–law, Itzik Khayt – the Londoner and Yankl Rudnitsky. All the tailors lived on Kaltinian Street. Later, Leyzer Itze Katz as well.

The tinsmiths in town were Zelik for the Shul Street, who later left for South America, Khatzkl Levinshteyn and Aron Yitzkhak Maliarovitch.

The blacksmiths were: Yehuda Moishe Gordon and Mendl Kharmatz from Kaltinian Street and Yekutiel Loyfer form Dolner Street.

The carpenters were Yose Kovarsky and his sons Moishe and Velvl. Chayim Feyve Shutan was a mason. So was Melekh. Eliyahu Landsman and Moishe Nodel were glaziers.

The bread bakers in town were: Avrom Altman, who was known as the Black Guy from Kaltinian Street; Mordkhai Yose the ritual slaughterer from the Train Street; Eli Yose Kovarsky from the Train Street. White loaves

[Col. 667]

were baked by: Meir Rudnitsky, Rafael Mirman, Shimon Ruven Kavarsky, and on Kaltinian Street, Shmuel Broida who came from Klushtshan and lived on Train Station Street.

The coachmen were: Nokhem Tzale Yukishsky, Meir Moishe Katz and his sons Velvl, Yankl and Mates. The entire Katz family worked at transporting goods for the export firm Deitch. Other coachmen were Hirshe Kliatchka and his sons Avrom and Tuvye, who mainly worked transporting lumber from the forest to the river. Other coachmen were: Moishe Khayt and Yose Tzinman.

[Col. 668]

Elia Rudnitsky, also known as Elchik the village elder would drive all the official government representatives. He was also responsible for delivering mail, telegrams and packages.

An interesting character was Abba the chimney sweep. He was very popular due to his good moods and happiness.

Labourers, in the true sense of the word, like in the factory towns, did not exist in New–Sventzian.

This in short is a description of the economic life in our town.

[Col. 667]

Rabbis, Hasidim and Houses of Prayer

For a long time the Poles, Lithuanians and Russians did not have a place of worship, and would have to go to other towns to pray.

Some of the Lithuanians belonged to a church on Kaltinian Street, led by the priest Burbe, who by the way spoke Yiddish well. The poles, Russians and another group of Lithuanians belonged to the Catholic Church in Sventzian and to the Orthodox Church there.

As soon as the Jews settled in town they made sure they had their own (Beis Midrash)

House of Prayer. The first one was built in 1869 and it was called the Old House of Prayer. The managers were: Shmuel Abba Smorgansky, Berl Berman, Mene Gordon, Alter Berman – the son–in–law of Avrom Mordkhai Azinsky, Shimshon Berman, Eli Yisl Kovarsky, Khayim Gordon, Feyve Gordon and others.

The first beadle of the Old Prayer House was Reb Mayreim and after Leyb Khayt and Yehuda Moishe the blacksmith.

A second House of Prayer was built across the street from the first, which was called: – the New House of Prayer. The managers were: Gedalia Zak, Zavl Bernshteyn, Mikhal Mikhl Yukishsky and Motl Zak the butcher.

The first beadle in the new House of prayer was Yose Lapidot who was a teacher and helped his wife sell milk.

After him, the beadle was Eliyahu Meir the teacher.

[Col. 668]

Both Houses of Prayer were attended by Misnagdim (not Hasidim), who comprised the majority of the Jewish population in town.

The Hasidim would pray near Kaltinian Street in a wooden building. After the big fire they built a big brick building. The managers were: Yose Shneur, Avrom Taytz, Shloimeh Maimin, Avrom Yitzkhak Tcharnobrodky, Kurliandchik and Hirshe Gurvitch. The first of the Hasidic group was Shimele and later on Mikhal Solomiak.

The first Rabbi in New– Sventzian was Reb Hirsh Rotzker, who died a few years before the First World War. The position was taken over by Rabbi Mereminsky, a grandson of “Chefetz Chaim”. During the First World War it was Rabbi Hirsh Volin. (His son Moishe is a well–known theatre impresario today in Tel Aviv). After the war the Rabbi was Rabbi Aron Cohen, the Chefetz Chaim's son–in–law. The last Rabbi in town was Rabbi Eliyah Kimkhi, who was killed together with all the other Jews in Poligon.

The town's ritual slaughterer was Reb Mordkhai Yose Gordon. Shulman was a cantor and a ritual slaughterer. The Hasidim would often bring their own slaughterer so there were almost always two in town.

After the First World War the ritual slaughterer was Mordkhai Yose's son–in–law.

For a long time New–Sventzian did not have its own cemetery. The deceased had to be taken to Old–Sventzian. Only in 1911 was a cemetery opened on the road to Kaltinian.

[Col. 669]

Not far from the Zemiane River, on the other side of the train tracks stands a single grave of Shimon Altman who died during the Cholera epidemic in 1893 and they were not permitted to bury him in another town.

Medical Help

Because of the large amount of officials and workers on the trains, New–Sventzian always had a doctor who also served the Jewish population. When he was busy, they would bring Dr. Orlov from Sventzian. Besides them there were always medics, like Mintz, Shreibman, Khatzkelevitch, Yose–Itze and the Pole Paniatovsky, who was, by the way, involved with the Jewish population.

In the last years there was a Jewish doctor from Vilna, Dr. Shloimeh Kopelovitch.

There were also midwives in town; Rayzl, Rashe, Zaman Ezra's wife, and Peysakh Shreibman's wife Ita, and a Christian midwife – Yavisha.

In New–Sventzian there was a pharmacy which belonged to two assimilated Polish Jews, the Tzipkin brothers. It stood on the side of Sventzian Street in a big garden. It had fruit trees that bordered on the only Jewish fruit garden belonging to Reb Shmuel Nokhem Kovarsky. After the war, Tzipkins nice house was bought by the Yiddish Folk–School.

After the Tzipkin brothers died the pharmacy was taken over by the pharmacist Borukh Turgel from Vilna, and later by Borukh and Khaya Shliapak.

For a while there was a small hospital which served the poorer population providing an opportunity to see a doctor and receive medication for free.

The Credit Office

The first Jewish social service institute was the credit office, founded in 1910 by Zalman Mendl Deitch. It gave out loans at very low percentage rates. The office was run by elected management but the greatest influence was made by Zalman Mendl and his entourage. It was located in the home of Kalman–Yose Vinoker.

[Col. 670]

Children's Education

At first there were no modern schools in town. The Christian children went to school in Sventzian, traveling every day on the small train. The Jewish children, mainly the boys, would study in Cheder (religious schools) where besides religious studies they learned arithmetic and writing.

The teachers were: Yakov Dovid, Eliyahu Bak, Yose the Beadle, Mikhl the Beadle, Khayim Yankl, Eli Meir Khatzkelevitch, Yose Kagan, – from Kaltinian, Shmuel Hendl – from Sventzian, and Veynshteyn who had a more modern Cheder. There were attempts to establish a modern Cheder by Moishe Yakov, Rabbi Rotzker's son, and by Cantor Shulman's father–in–law, who they called the teacher from Smorgon.

At his school, the children sat on benches which were an exception then.

After the 1905 revolution, thanks to the efforts of a progressive government official Politayev, three Russian classic Folk– Schools were founded in town. A large number of Jewish children studied in these schools together with Christian children.

During the First World War a modern Folk – School was founded where the language of instruction was Yiddish. It belonged to the TSISHO organization. A second school was founded with Hebrew as the language of instruction, belonging to the Tarbut organization.

The Fire Department

New–Sventzian had a good volunteer fire department, comprised of Jews and Christians. The management was also run by Christians and Jews.

The Christain chiefs were: Dreps, Shleglmilkh, Tzibulsky, Savko, Panizhovsky, and others. The Jewish “Chiefs” were: Zalman Kovarsky, Motl Milner, Khatzkl Levinshteyn, Yosef Gildin, and in the last years Eloyshe Katz, a newcomer from Kaltinian.

The cooperation of Jews and Christians in the fire department helped improve Christian Jewish relations. Thanks to this, Tzibulsky and Savko became true friends of the Jews maintain good relationships.

[Col. 671]

|

|

Lying down: Motl Gurvitch, Lozer Svirsky, Avrom Kovarsky, Yitzkhak Kovalsky, Berl Ryng, Avrom Katz Higher: Elchik Klubak Sitting: Sovka_____, Poniatovsky, Gudelis, Khatzkl Levishteyn, Motl Milner, Aron Yitzkhak Malarovitch Standing: Khasriel Itzikson, Moishe Gurvitch, Avrom Yaffe, Hirsh Kovalsky, Tzibulsky, ___,___, Avrom Gordon, ___,___, Yosef Gildin, Yitzkhak Shutan, ___, Fishl Saltaysky, Avrom Umbrus, Khone Rutshteyn, ___, Beinish Svirsky, Henekh Kovarsky, Nosn Shutan, Shabsai Shmulevitch, Lipman Zak, ___, Eltchik Bruslan, Nokhem Troytze, Mirman, ___, Hirsh Bitsunsky, ___, Yudl Rudnitsky |

[Col. 671]

Revolutionary Turmoil Before and After 1905

In 1903 the Russian Japanese war broke out which ended in failure for Russia. Liberal groups were extremely unhappy with the Czar and his clique. This strengthened the workers' revolutionary movements throughout the land. As a result a large train strike broke out.

Since New–Sventzian was an important train centre with many train workers; the revolutionary turmoil was strongly felt.

It is worthwhile to recount an incident that took place at that time at our station. Noske, Ruven the butcher's 13 year old son climbed onto a locomotive, untied the rope that served

[Col. 672]

as a brake and sent the train rolling.

The Polish workers tied their revolutionary activities to the hope of a national liberation, and the creation of an independent Polish state. The head of the Polish revolutionary movement was the leader pf the Polish Socialist Party “P.P.S”, Jozef Pilsudski.

He was born in our region, on a farm in Zulove which was located between Podbrodz and New– Sventzian. He decided to attack a mail car at Bezdan station, in which there was a lot of money. After the attack, he hid for a long time with Mordkhai Yose's Maishke, who also belonged to the P.P.S.

The revolutionary turmoil also effected the Jewish youth in our town,

[Col. 673]

mainly, youth from fine families. Their revolutionary activity was not expressed in deeds, rather in holding protests. The P.P.S and the Bund found representatives among the Jewish youth in our town.

Between the poverty and the small proletariat in our town, the Bund dominated. A Bundist activist from Sventzian, Miron Tarasaysky came to town. He took part in a meeting that took place at Yose's house.

At that meeting our Bundists sang the oath to the Bund and swore on a red flag their devotion to the party and revolution.

An original revolutionary demonstration took place at the wedding of Leybe the shoemaker and Khava's Khaya, who were both true proletariats and very poor. All the guests sang revolutionary songs and they flew a red flag.

The leader was Yosl Gorfeyn from Vilna and a member of the Bund.

A victim of this revolutionary activity was Shmuel Teiytz who worked in Vilna. He was arrested and sent to Siberia.

After the revolution failed, the scapegoat, as always was the Jews.

Government sanctioned Pogroms broke out in many cities. The youth of New–Sventzian immediately organized self defense. Everyone was armed with nagaikes, – a long, rounded stick with a buckle and a ball of lead at the end. Here and there, someone got hold of a revolver.

There was never a pogrom in our town. Everything remained calm.

The revolutionary turmoil and the elections to the Duma brought an element of hope that we may soon be freed from the Czarist yoke. But the failure of the revolution, and the harsh reactions left a bitter disappointment.

[Col. 674]

Among the Jewish population the feelings for national liberation were strengthening. It was becoming clear that Jewish redemption would not come from changes in the Diaspora, rather form rebuilding our old home in the Land of Israel. A few Zionist activists emerged in town, particularly Shimon Ruven Kovarsky, Yosef Berman and Yerkhmiel Gordon, the son of Mordechai–Yose the ritual slaughterer.

Another group among the youth showed a strong inclination to emigrate across the ocean. Many actually did leave for America.

Others left our town for Vilna, worked at various jobs or studied in the high school and the university.

Those living in Vilna would come home for holidays bringing with them “winds of change”. They had a great influence on the youth that remained in our town, trying to change their standard of living.

At this time, Moishe Bikson, the grandson of Mene Gordon, opened a library in the home of his father Shmerl.

Heshl Kovarsky helped to spread literature through town. He was an enlightened Jew who provided books for the so – called heretics.

The First World War

Right after the outbreak of the First World War our region was cut off from the German mark, the largest buyer of all our products and goods. All the export firms dealing with Germany had to liquidate. Due to the war and difficult communications, business with the Polish large cities and deep in Russia ended as well. Together with Warsaw and St. Petersburg, the economic situation in our town was paralyzed.

With material difficulties, we also experienced loss of loss of morale and national problems now developed. Many of our youth were mobilized and sent to the front. At first everyone was intoxicated by the great victories Russia gained over the Germans. Most of all, we were excited by operations the Russian General Renenkampf, of German origin, carried out in Eastern Prussia. Patriotic feelings were growing everywhere.

[Col. 675]

The picture changed very quickly. The Russian army suffered great defeats; she was destroyed in eastern Prussia. The mood was oppressive. Opposition to the government and its generals was growing. The Czarist government attempted to channel the anger of the people elsewhere and quickly found the eternal scapegoat – the Jew.

All at once they realized that Renenkampf was not responsible for the defeat, nor the spy Miasaydov from the border patrol at Verzhbolov, but the Jews. They were considered the greatest enemy of the Russian people and all the Jews were considered informers. The Jews hid telephones in their beards and sent important new to the Germans.

In order to secure the front from such “horrible informers”, the Russified Polish General Januszkevitch gave the command that all Jews in the Kovno Fortress region “must leave their homes within 24 hours.”

Thousands of Jews, wandering as refugees, lost their homes, their belongings and everything they had acquired over a few hundred years.

The wave of Jewish refugees approached New–Sventzian on the small train. They were later evacuated to Ukraine and deep into Russia.

The town soon became the centre of “YEKAPO” (Jewish Relief Agency), which provided aid to the ruined refugees.

The Jewish community in New–Sventzian became active in the work to help refugees, particularly the Jews from Ponevyz.

They too soon met their fate as refugees as well, as the front was nearing; the fear of war was increasing; we feared provocation and denunciations. This had a great impact on our town, and people soon joined the large wave of wandering refugees.

The majority of the Jewish population left their homes and went

[Col. 676]

deeper inside Russia. Many families did not return and broke all ties with our town.

Only a few Jewish families remained in New–Sventzian and lived to see the arrival of the German army.

Under German Occupation

August 1915 New–Sventzian was occupied by the German army. It did not take long before Jews in hiding began to return. Returning families included those of Zavl Bernshtyen, Leybe Troytze, Velvl Pupishsky, Chayim

|

|

Ley Segalovitch, Hirsh Kizberg, Mordechai Yose the ritual slaughterer, Chayim Gordon, Avrom Yitzkhak Rabinovitch, Borukh Turgel, Shteyngold, Eltchik Elperin, Chayim Feyve Shutan and others.

Jew from surrounding towns began to arrive as well, as they could not return to their home towns. Among were the families Tzepelevitch from Postov, Shloimeh Gurvitch and Svirsky from Vidz, Berl Zale Guterman from Kaltinian, Ligumsky from Sventzian, Feyge and Mania Tzikinsky from Tzekin, Heshl Kavarsky from Niementchin, Yisroel Portnoy from Yanishok.

Slowly the youth hiding in Vilna and other places begin to return, like Leyb and Henekh Kovarsky, Heshl and Motl Gurvitch, Alter Azhinsky, Lazer Yanishsky, Zalman Maimin, Zalman and

[Col. 677]

Polia Shneur, Shmuel Leyb Shaftan, Sholem Berman, Hirsh Bikson and others. The German divided the occupied region into two: a front territory and a phase territory. The difference was those in the front territory were ruled by strong wartime laws and the civilians were confined; in the phase territory, people were a lot freer and were even able to earn a living.

We were lucky, New–Sventzian fell under the phase – territory. They immediately founded a civilian administration. The elected leaders were Zavl Bernshteyn and his deputies Chayim Gordon and Leyb Kovarsky. Besides them, there were a few Christians in the administration.

Most of the Jewish homes were taken over by the Germans. Prisoners of war were placed in our houses of prayer, and they worked in German warehouses.

The Jews slowly began to adapt to the new conditions. Thanks to the similarity between Yiddish and German, the Jews were able to understand their occupiers.

Jewish coffee houses and restaurants soon opened. They began to exchange things with the Germans. Both sides began a big smuggling business. Jews did not do too badly.

Soon a social life began to emerge, around the new prayer house. The two others had been taken over by the Germans.

The Rabbinate was taken over by Rabbi Zvi Volin, the son–in–law of Yudl the baker from Sventzian. The administrators were Zavl Bernshteyn and Yisroel Portnoy.

The youth began to organize cultural activities. They received books and newspapers from Vilna. They would gather to discuss various topics, or just enjoy and evening together.

Meanwhile, not far from us a great effort was being made to save Jews from hunger and cold.

The front was now near

[Col. 678]

the towns Myadel and Haydutzishok, and the Germans decided to remove the local civilian population. They took them to the former Russian military summer camp “Poligon”, which was situated between New–Sventzian and Podbroz.

The Jews were also placed in wooden barracks which were surrounded by barbed wire. They all had to work for the German military and received very little food.

We knew the refugees in Poligon were suffering from hunger. We founded a committee to provide aid to the Jews in Poligon.

Those serving in the committee were: Avrom Yitzkhak Rabinovitch, Zavl Bernshteyn, Chayim Leyb Segalovitch, Borukh Turgel, Velvl Pupisky, Leyb Kovarsky, Heshl Gurvitch and others.

The committee collected various products and sent them to Poligon.

The committee realized the demand for help was too great for them to handle alone. They reached out to other towns, like Sventzian and Kaltinian for help. Sventzian quickly organized a committee comprised of: Rabbi Meirovitch, Yosl Svirsky, the Brumberg brothers and Teytlboym. Those to help out from Kaltinian were: Gershon Rudnitsky, and the Vidz Rabbi, Rabbi Kahaneman (later from Ponevyz), who was then in Kaltinian.

Winter was approaching and it would be hard to survive the frost in the broken wooden barracks. They began to explore ways to get them out.

First they approached the field rabbi, Rabbi Lev, who was well connected with Jewish aid organizations in Germany.

The German authorities came back with a negative response. The committee then approached community activists in Vilna, Rabbi Rubinshteyn and Dr. Zemakh Shabad and asked them to intermediate for the Jews in Poligon. This did not help either. It was decided to secretly take out the Jews. The plan was magnificently successful. All the Jews were freed from Poligon and no one was ever caught.

[Col. 679]

The aid committee did not cease to exist after this operation. The Germans brought other Jews to Poligon, including some from Vilna. A typhus epidemic broke out in Poligon and they had to figure out how to help the sick.

The Founding of the Jewish Folk – School

In 1916 the German authorities called upon Jewish deputies to found a special German school for Jewish children.

The Jews did not understand the intention. They did not find it necessary to consult with anyone and signed a request to open a school for Jewish children with German as the language of instruction.

And so, a German school for Jewish children was founded in town. The teachers were: Shapiro and Hinda Fliner from Postov. Religious studies were taught by Rabbi Volin.

[Col. 680]

The writer (Heshl Gurewitch) of these lines, while in Vilna, fought for a Jewish school in Czarist times, and began to agitate against the decision, and worked to found a school with Yiddish as the language of instruction.

Unfortunately, not everyone understood the importance of a Yiddish school. Many Jews felt the school should run in the language of the government. If before it was Russian, now it should be German. They said the plan is normal and this is how it should be. Even Rabbi Volin advised not to join the “rebels”.

The youth responded warmly to our first call. But we needed parents to present our request to the authorities. The community workers were excited with our plan: Avrom Yitzkhak Rabinovitch and Turgel the pharmacist.

We began with the fact that in that school they learned on Saturday and rested on Sunday. One Saturday I came to the new house of prayer just before the reading of the Torah went up to the Bimah (stage) to make a speech in support of a Yiddish school.

|

|

Seated: Beyla Gurvitch, Shayna Rudnitsky, Zilbershteyn, Shayna Katz, Roahe Yunglson, the teachers Hellershteyn, Pliner, Shapiro, Sorah Kharmatz, Zisle Pupisky, Zalman Bernshteyn, Liza Kurliandchik, Pesie Tzinman, Khaya Tzeplovitch, Tzipe Gordon, Feyge Berenshteyn, Soreh Volfson, Khane Shutman, Mine Kulbak, Khaya Gordon, Moishe Volin, Motl Tzinman, Leyb Pupisky, Menke Volfson, Aron Rabinovitch, Yitzkhak Milner |

[Col. 681]

I explained that Jews have a right to receive an education in their mother tongue, as all other nations. I then presented to them that Jewish children should have their day of rest on Saturday and not Sunday.

There was uproar in the house of prayer. Some complained I was doing this on the Sabbath. Others believed I was right.

The struggle for a Yiddish school went forward with a lot of energy from that Saturday on. In 1917 a school was founded with Yiddish as the language of instruction. The first teacher was Eliezer Hellershteyn from Vilna.

Besides the aforementioned two activists, the founders of the school were: Sholem Berman, Motl Bak, Leyb Kovarsky, Hirsh Bikson, Nekhama Kovarsky, Mania Tzekinsky and Dina Tseplevitch.

Alongside the founding of the Yiddish school was the strengthening of general cultural activity in town. A general “National Association” was founded where many young people joined. It was divided in two directions: Zionist – with Motl Bak, the teacher Hellershteyn and headed by Nekhama Kovarsky, and the Socialist – with the writer of these lines, Mayrim Segalovitch, headed by Eltchik Kulbak. A rich library was founded in the home of Shmuel Kulbak who lived on Vilna Street. Turgel the pharmacist began a drama club. He put in a lot of effort and time before he decided the troupe could perform for the public.

The first play the drama club performed with great success was Yakov Gordin's “God, Man and the Devil”. This is how life was in our town during the German occupation, until the outbreak of the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Second Reich.

Under Various Regimes

When we first began to hear rumours about the Russian Revolution, we were happy. Finally we would see the end of the Czarist regime, which

[Col. 682]

oppressed the Jews, with general reactionary politics and hypocritical attitudes.

A year later, the Russian Revolution influenced Germany where they deposed the Kaiser and created a Republic. The Germans left our region and it was now controlled by the Red Army. At first it was only bourgeois complaining, but then even the strongest socialists were bitterly disappointed.

All communal activity was stopped. The Soviet power even got involved in the existence of a Yiddish school, forbidding the study of bible as it was considered religious education. These orders even left an impact on the extreme Yiddishists.

On all the roads there were streams of homeless people trying to return home. Many families returned to New– Sventzian. The entire Kovarsky family returned with all their sons, daughters and their children. Other families that returned were: Berman, Shapiro, Shutan, Gordon, Elperin and others.

Only a few families remained far away: Khone Yose the tailor, Dovid and Sholem the butchers', Avrom Soloveichik.

New families arrived during the German occupation and remained.

New–Sventzian also became a centre for prisoners of war and refugees who were looking for a way home.

The writer of these lines, together with Eltchik Kulbak worked on behalf of the homeless at the Red Cross.

It did not take long for the Red Army to leave our region.

The Polish legionnaires arrived, led by the former revolutionary, Jozef Pilsudski. They were filled with venom and hatred for all non– poles, especially Jews.

Their entrance into Vilna was accompanied by a Pogrom against the Jews. Jews were shot,

[Col. 683]

Among them was the poet A. Vayter. New–Sventzian only experienced fear and robbing of Jewish possessions.

After the Bolsheviks left our town, we joined “YEKAPO” in Vilna and received financial aid for the needy, especially widows and orphans.

We also received a subsidy for our school which made it possible to continue to exist. During the war the school was totally destroyed. The building was taken over by soldiers who destroyed it. Only with great difficulty we managed to salvage the old benches. We rented another location and the children began to study.

The majority in town lived from donations from American relatives. All the community activists were trying to figure out how to create a self– defense and an organized Jewish community.

Soon, there were elections to elect officials for the Jewish community. There were two lists: from the older generation and the youth.

The result was the youth received a large majority and the first chairman of the Jewish community was the teacher from the school, Yitzkhak Gordus. After him was the pharmacist Borukh Turgel, who held the position until he left town.

After Turgel, Chayim Leyb Segalovitch was elected chairman.

The board of directors of the Jewish community eventually took charge of all the social work in town. The old timers were not very happy. They were not used to things working this way.

Thanks to the funds we received from “YEKEPO” in Vilna, we were able to support the Folk– School, the teachers and the religious school. The community also funded a library, a children's kitchen and a fund for the needy.

After communal elections came elections to city council. These were still the honeymoon months of the Polish–Jewish agreement. A joint list of Poles and Jews

[Col. 684]

was presented. Four Jewish councilmen were elected: Yitzkhak Gordus, Chayim Leyb Segalovitch, Borukh Turgel and Avrom Yitzkhak Rabinovitch.

The authorities forbid the author of these lines to run as a candidate because he wrote sharp articles in the Yiddish press against the harassment and robbery carried out by Polish soldiers and administrators.

The Yiddish Folk – School now had the opportunity to buy its own building. The wife of Tzipkin the pharmacist wanted to sell her house which was surrounded by a beautiful garden. We bought the building from her.

Disregarding the fact they had been assimilated Jews their whole life, the Tzipkins wanted their house to remain in Jewish hands.

With the help from “YEKAPO” and large donations from the local community we bought the beautiful building and it soon became the cultural and social centre in town.

It did not only house the Folk–School, but also the library, the relief agency and later the People's Bank, the “He'Chalutz” and “Young Zionists”. From then on, all lectures, talks, evenings and performances took place in that building.

The Zionist pioneers began their first training on the soil which belonged to that building.

Meanwhile, over the next few years, there were many political changes in our region. Like a ball in football (soccer) field we are being tossed from one regime to another: from the Bolsheviks to the Lithuanians, and from them to the Poles.

First of all, the Soviets marched into Warsaw. New–Sventzian was not spared. The same issues repeated itself after the war. However this time we experienced more than just fear. Some Jews from Sventzian and Podbrodz were shot.

After the defeat the Red Army experienced near Warsaw, they retreated from Poland and handed over power of our region to the Lithuanians. In Polish history this defeat is referred to as “the miracle at the Vaysel”.

For a short time we found ourselves under Lithuanian rule and enjoyed all the freedoms of

[Col. 685]

Lithuanian Jews. There was a liberal government in Kovno and Jews received national autonomy. There was even a Jewish minister nominated to take care of Jewish affairs.

The relationship of the Lithuanian authority to our institutions was very good. The Jewish community received full rights. They gave the Yiddish school a large subsidy and the relationship was no different than to other schools. In general, the Jewish population was pleased with this match.

It did not take long before a received a new regime. The Polish general Zhelogovsky rebelled firstly against the Polish government and her military administration, chased out the Lithuanians from Vilna province, and founded a new state: Middle – Lithuania.

As he needed the Jewish vote in a decision to determine to which people would Middle–Lithuania belong, his treatment of the Jews was magnanimous, as in previous times.

In the end, the majority called for uniting Vilna province with the rest of Poland. The veil was lifted and we returned to the Polish republic.

Once again we were under a new regime.

Under Polish Rule

After the unification of Vilna province with Poland, the Sventzian region was totally cut off from Russia and Lithuania. The borders of Poland were: from the north at Dvinsk – with Latvia and from north –east – in the middle of the town of Lingmian – with Lithuania.

The small train toward Ponevyz stopped functioning. Just like the Germans, for strategic reasons, built the big train between Podbrodz and Haydutzishok, the small train to Gluboke went as far as Lintup. The big train to Warsaw went as far as Turmant – Zemgale, near the Lithuanian border. New–Sventzian lost its status as an important railroad centre, and remained with only one window – to Vilna and Warsaw. This had a huge impact on the Jewish community and ruined the economic life of our town.

We found ourselves on the so–called east – territory,

[Col. 686]

that suffered greatly from the war and the passing from one regime to another, more than others. All eyes were on the American Jews, and the powerful help organization, the Joint.

In Vilna, the help lay in the hands of “YEKAPO” which was run by the dedicated workers: Dr. Shabad, Moishe Shalit, Dr. Vigodsky, Rabbi Rubinshteyn, Nosn Kovarsky, Yevderov, Kliansky, Valk, Eliyahu Rudnitsky and others.

“YEKAPO” spread its activities throughout the province, providing help in various regions. They provided clothes and food for the needy: they provided artisans with machines and coachmen with money to buy horses; they founded a relief fund; opened kitchens for children and adults, and founded an emigration service called HIAS (Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society), which provide information and help on immigration issues, and helped people locate relatives in other countries, particularly on the other side of the ocean. Thanks to HIAS many people found their relatives abroad, contacted them and received aid which helped them exist is such difficult times.

“YEKAPO” workers were also dedicated to improving the development of cultural activity among the Jewish population. They gave out subsidies for Jewish schools, libraries and orphanages.

The Yiddish school in New–Sventzian was a branch of the Yiddish school organization in Vilna, but it was not purely Yiddish in character. It was dualist and the majority of its graduates were Zionists. They embraced both languages but agreed Yiddish should serve as the main language of instruction of the school.

The school continued to exist for a long time. In 1921 we were privileged to see our first graduating class. In 1924 we celebrated the second.

Thanks to the school, intellectual circles in town were growing. The teachers married girls from our town and settled here. The teacher Hellershteyn married

[Col. 687]

Liza Maimon, Gurdus – Mirl Shneur, Tzinzinzatus – Rosa Berman, Vinik – Genia Yavitch.

Thanks to this, the teachers participated in all community events in town. They were active in youth organizations, in the People's Bank, the board of the Jewish community and the magistrate.

With the growth of our youth who were influenced by the Hebraists, and the growing differences emerging on the Jewish streets, by the end of the 1920s our school was split and a second school was founded. This school was connected to “Tarbut”.

The “YEKAPO” workers in Vilna created a large book – centre and provided the libraries in the provinces with scientific and literary books. This saved the New–Sventzian library from closing. Thanks to the books received from “YEKAPO” and thanks to the hard work of the teacher Vinik, the library was reborn. The author of these lines served as representative of “YEKAPO” in New– Sventzian, who together with Yitzkhak Gordus, worked on behalf of the whole province.

Thanks to the founding of The People's Bank the economic situation in town improved. After the bank was founded in Vilna, branches were opened throughout the provinces, of course in New– Sventzian as well.

The first manager of the People's Bank was the teacher Gordus. Motl Bak worked as a cashier and Yakov Shvartz as the bookkeeper, Chana Portnoy was an employee.

Inspector Kliansky did a lot for the bank. He was a good friend and also did a lot for the Yiddish school.

The People's Bank slowly became the most important factor in the continued rebuilding of our town. It enabled many families to get back on their feet and receive material existence.

All the above– mentioned efforts did not help. The economic situation of the Jewish population

[Col. 688]

became more difficult from year to year, until the time came when they could not see any future prospects.

The export business which had been connected to Russia and Germany had already been liquidated. Jewish business now relied totally on the local population. This was a weak solution. The official and workers on the trains were mainly Poles. The government set up special cooperatives for them. Christians began to open shops which brought great competition to the Jewish shopkeepers.

A stubborn battle began against Jewish artisans in the form of guilds, permits and forced closure on Sundays.

The years of crisis had begun. The older Jews had no choice, but the younger ones were searching for a way to get away from this hopeless situation.

Many young people attached themselves to the Zionist organizations in order to go to a training camp and prepare to immigrate to the Land of Israel.

Some of the wealthier families were looking to leave our town. The first to head in this direction was the businessman Avrom Yitzkhak Rabinovitch, who liquidated his business and moved to the Land of Israel in 1923. The movement was stronger among the youth, but painfully, only a small amount had the opportunity to emigrate. The majority of the Jewish population had to remain in town.

All of them, our nearest and dearest, waited for better times, for redemption and salvation.

A few years went by and then the Second World War broke out. New–Sventzian spent a few years under the Soviet regime, and then came the Hitlerite and Lithuanian animals that brought a dismal end for everyone.

Whoever was not saved in time was killed by the cruel beasts.

The beautiful Jewish community of New–Sventzian was destroyed. Nothing remained.

We who lived and worked there will never forget. We will remember our town, with love and longing, until our last days.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Svencionys, Lithuania

Svencionys, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 31 Dec 2019 by LA