|

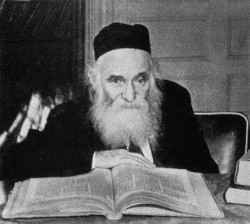

The Gaon Reb Aharon Kotler

|

|

[Page 110]

by Rabbi Moshe Yissaschar Goldberg, z”l

Translated by Kadish Goldberg

1. The Yeshiva After the Revolution

The Rabbi of Slutsk, the illustrious Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, zt”l, with the brilliance of his Torah and his congenial character, enlightened the eyes of his congregation and of the thousands of pupils who flocked to him from near and far.

The overwhelming majority of the people of Slutsk were mithnagdim. They avoided the Chassidic practice of exaggeratedly lauding the miracles and wonders performed by this tzaddik or that saintly Rebbe. Despite this, the masses believed with perfect faith that there was some power inherent in their rabbis and righteous men; whatever they blessed was blessed – “He [the Almighty] fulfills the will of those who fear Him.”

I remember how, as a child, I heard my mother tell of an event that amplified the greatness and righteousness of our Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer in the eyes of all the community. A Russian policeman had come to the home of the Rabbi with orders from the Chief of Police to carry out some act; refusal to do so would result in incarceration. The Rabbi was not intimidated and he refused to obey the order. The policeman forced the Rabbi to accompany him to the station, pulling him bodily. The policeman had seven sons. Soon after the outrageous event, his firstborn son suddenly took ill and died. After a few days, most of his other sons took ill and died, leaving only one son hovering between life and death. The bereaved policeman believed that the holy “Rabbin” was responsible for the tragedy, and came to beseech forgiveness. He entered the Rabbi's home, prostrated himself on the floor, wept, and pleaded that the Rabbi forgive him and pray for the recuperation of his young son. The Rabbi forgave him, and the son's health returned.

During the First World War, the joy of the Sukkot festival turned to melancholy. The number of battlefront casualties grew daily; the front moved closer and closer to Slutsk. The synagogues were full of worshippers, but a cloud of sadness enveloped the congregation – was not a single ethrog in the synagogue. Because of the disruptions in travel, the Slutsk community had managed to acquire only two ethrogim that year, and these were placed in the homes of the rabbis. The Jews flowed to the homes of the two rabbis in order to fulfill the mitzvah of the four species. Father, of blessed memory, took me with him – how we looked forward to observing the mitzvah of holding of the lulav in the home of Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer z”l!

With the dethronement of Tsar Nicholai II, all the citizens, Jew and gentile alike, believed that a new order of total freedom and equality would replace the rotten regime. Young Jews burst out joyfully into the streets of Slutsk and conducted enthusiastic demonstrations, giving public voice to that which had been repressed in their hearts during the old order. In the processions marched the different Zionist organizations and the members of the Jewish Socialist “Bund.” The former marched arm in arm, the blue and white flag leading the companies, all singing with great fervor “Sham BeEretz Chamdat Avot” – “There in the Fathers' Beloved Land” and “Se'oo Tsiona Nes VaDegel” – “Raise the Banner and the Flag to Zion.” etc. The Bundists also marched proudly, their red banner waving, singing the Bundist “Vow” and the “Marseilles.”

Never had the Jews enjoyed such good days. The city elders were fearful lest the youth be swept up in the currents of the revolution, distancing themselves completely from the tradition of their parents. As a preventative measure, it was decided to establish a modern, religious high school. In order to attract the youth, it was decided that the pupils would wear special uniforms, with bright brass buttons embossed with a Jewish emblem. These pupils would not be inferior to their companions in the Russian gymnasium, neither scholastically nor in appearance; they would even surpass them, thanks to their Jewish studies.

The idea quickly won adherents, arousing the envy of youth like myself who had been brought up exclusively on the knees of Torah. I confess without embarrassment, that even during the days of the Tsar, I was envious of my friends who studied in high school. I was comforted with the projected establishment of the school for Torah and science, in which I would be able to study both Torah and science, and in my school uniform I would externally resemble the gymnasium pupils. I revealed my secret desire to my revered father, and his face took on a somber look. “We're going to talk to the Rabbi.” Abba told the rabbi of my intentions. The Rabbi lovingly stroked my cheek and said: “Such a school is a necessity for boys whose Judaism is threatened by the wave of the revolution. It is to be feared that, because of the new freedom, the boys will grow further apart from the bosom of their parents, and it is important to draw them close and to keep them in the framework of traditional life. But a boy such as yourself, educated and raised in a home marked by Torah and fear of God – why should you desire such a school, in which the Torah studies are limited, and the holy and profane are intertwined? Go back to the Yeshiva, and there you will find your world.”

These simple and heartfelt words, lovingly spoken in a concealed vein of worry, penetrated deep into my heart, and I ceased to dream about gymnasium, about uniforms and brass buttons. (Incidentally, tremendous effort was invested in the establishment of this school; unfortunately, the tumultuous events that suddenly blackened the skies of Russian Jewry prevented realization of the plan).

The honeymoon of the revolution witnessed great fermentation in the Jewish community. During the Tsarist regime, because of fear of the police who kept track of the behavior of the community leadership, it was difficult to realize the yearning for free personal and communal expression. No sooner was the arm of oppression broken and the last of the Romanovs gone down in defeat, then great forces burst forth onto the Jewish street. I remember how the city was in tumult at the approach of elections to the “Kehillah” and the “Founding Meeting.” “Agudath Yisrael” appeared as an organized body. The “Zionists” and the “Bund” also conducted vigorous campaigns. The air was full of slogans; posters were plastered on walls and pillars. In the center of the city, on the “Shosai,” the Orthodox raised a large poster which described the aged and the young carrying a Torah scroll in their arms, marching up a path to the light of a new sun, which shone in the skies of Jewry. Hundreds of men and women, taking their Shabbat noon walk, would stop and stare in wonderment, impressed by the religious campaigning, or perhaps just surprised by the very fact that eligious Jews publicly take positions on political issues which had previously been considered unimportant.

The synagogues also provided platforms for the masses during the campaign. I see, as though standing before me and alive, in front of the Ark of the Law, Reb Zelig of Starobin (Rabbi Zelig Portman), one of the Slutsk Yeshiva's finest students (He eventually died in New York). He spoke with fiery enthusiasm, holding his audience spellbound. Rabbi Avraham Yitchak Shisgal, z”l, spoke with polished style, with sweet and clear intonation. The Yeshiva Head, Rabbi Aharon Kotler, may he be set aside for long life, stands on the pulpit, words of flame shooting from his mouth.

[Page 111]

The Rabbi of Slutsk, Rabbi Isser Zalman eltzer, zt”l, his noble appearance radiating gentleness, would occasionally appear among the speakers.

I remember how, on a winter night, a large crowd gathered in the Great Beit Midrash to hear the speakers – or to heckle. The rabbi had barely ascended the pulpit and begun to speak when a few arrogant young men began to harass him with interruptions. The rabbi answer softly, as though reciting the Talmud before his students: “Let them disturb all they want; this will not harm us,” and continued with his speech.

The First World War, which brought in its wake severe problems and great destruction in all branches of life, hit the yeshiva “Etz Hayyim” of Slutsk very hard. Military conscription, damaged roads, and the dangers characteristic of emergency situations, diminished the number of pupils.

The authorities expropriated the spacious yeshiva building, and the yeshiva was forced to go into exile, first to the Tailors' Synagogue, then to the synagogue named after Reb Isserke. I recall those moments of exultation that beat in our hearts when the yeshiva building was later evacuated and we were able to return to our 'home.' The number of pupils increased, but there was a dearth of Talmud texts; without texts, how does one learn Talmud? The inventory of the booksellers emptied out; the connection with publishers of religious books was severed; pupils rushed to the city's synagogues to try and obtain Tractate “Gittin” from the gabbaim. Some were lucky enough to obtain a tome – whether on loan or by full payment – from private sources.

My companion, Yitchak Sochalitsky (currently in Israel), and I went from synagogue to synagogue, searching unsuccessfully. Suddenly an idea! The volumes of the Lyakhovichi refugees! When the Jews of Lyakhovichi fled the terrors of the approaching war, they took their Torah with them; tomes of Talmud, Poskim, and Responsa. The books were loaded on wagons and brought to Slutsk. Since there was lack of space in private homes to house this large and valuable treasure, the refugees agreed to store all the books on the windowsills of the “Cold Synagogue.”

We set our eyes on the “Gittin” volumes of this treasure, but two obstacles blocked our way. One, how does one climb to so great a height? Two, may one take books without authorization? For a response to the second question, we approached the rabbi. He walked back and forth, sunk in thought, and, after consideration, rendered his decision: It is permissible to take them, on the proviso that we intend to return them. The serious look on the rabbi's face indicated that it was very difficult for him to decide on his own. It appears that he suggested that we also confer with Reb Moishe, one of the senior yeshiva students; he certainly would understand the pressing need.

Reb Moishe was an outstanding scholar and a noble personality who was later, in the beginning of the 20's, appointed rabbi in Kletsk. Rumor has it that the Nazis murdered him.

I recall my transgressions. We looked for Reb Moishe of Lyakhovichi that day, but could not locate him. We got to work, assuming that we would receive post facto approval. The mission had to be executed on Shabbat, because on weekdays the synagogue was closed. We entered the synagogue during the afternoon Mincha service, opened some side doors and left them slightly ajar, so that the shamas would not notice them. When the congregants finished Mincha and entered the side rooms in order to chant Psalms and the Maariv service, we left the synagogue, sneaking in later through one of the opened doors. Now we had to overcome the main obstacle. We placed bench upon bench, stender upon stender, and then scaled our wobbly ladder. Finally, right before dusk, we found two volumes of “Gittin,” Vilna edition, beautifully bound. We descended safely, and returned the benches and stenders to their places.

|

|

The Gaon Reb Aharon Kotler |

The next day we returned, ashamed, to the Rabbi's home. Fortunately, Reb Moishe of Lyakhovichi was present. We told him the whole story. Reb Moshe listened with a smile on his lips and approved our action. Our consciences were relieved of a heavy burden.

On the morrow, the noble figure of the Rabbi appeared in the Yeshiva entrance. He entered unhurriedly, exchanged words with a few of the students, as though he were one of them; he then walked back and forth, engrossed in thought. When he sat down, my companion and I, with hearts full of both fear and joy, approached, and our entrance exam began. The Rabbi did not ask difficult questions, nor did he indulge in intricate pilpul; he decided that we were capable of independent self-study.

Well do I remember that winter day, when the Slutsk yeshiva went off to exile, to Kletsk. A treaty between the Bolsheviks and the Poles transferred Slutsk to Soviet rule. Reb Aharon Kotler, may he live to long and good years, and our family, assisted by a few of the senior students, loaded their belongings on the wagon. They, themselves, went on foot, heads bowed, souls sad. The Yeshiva “Etz Hayyim” of Slutsk went into exile, but the exile was not total. A substantial minority of students remained. Supervised by the city Rabbi and the spiritual mentor, Rabbi Asher Sandomirsky, they remained to continue the holy work in the city, despite the foreseen difficulties and dangers. Thus was the body of the Yeshiva cleft in two.

Before long the Slutsk students began to feel the pressures of the Soviet regime, and they found it necessary to “steal the border” and move to Kletsk. Thanks to experienced smugglers, this was not an involved operation, but it did entail dangers.

[Page 112]

|

|

The Yeshiva "Etz Hayyim" of Slutsk going off to exile, to Kletsk |

Some boys were apprehended by the Bolshevik Border Police and accused of counter-revolutionary activity. Rumor had it that some of the students were arrested by the Polish Border Police, sentenced to incarceration, lashes, and torture.

When my time for departure arrived, I was afraid of being caught, and shared my fears with the Rabbi. My apprehension touched his heart, and he considered what could he do for me. Finally he decided to give me a letter, written in Polish, to the effect that he knew me to be an honest young man, a student in his Yeshiva. The Rabbi thought that such a document might lighten my punishment should I – God forbid – be caught by the Polish Border Police. A scribe proficient in Polish penned the document in a clear cursive script, and the Rabbi signed.

At the time, I did not appreciate how much the Rabbi had endangered himself by giving me this letter. Had I been apprehended by Soviet guards with the letter in my possession, they certainly would have accused the Rabbi of aiding young men to flee from Russia to Poland. As it was, the Soviet authorities had already set their suspicious sights upon him. (He, was, in fact, forced to escape into Poland a month later). Yet, despite his precarious position, he gave me the document with a blessing that I succeed in safely reaching my destination.

Until this day, I am amazed. Is it possible that he was not aware of the danger, and endangered his own life in order to save a Jewish soul? Perhaps he was well aware, but still he put his life in danger. He was certain that, with God's help, no evil would befall him.

2. Reb Kaddish der Melamed

My grandfather, Kadish Kraines, best known as Reb Kadish the Melamed (teacher), was weak and thin, his face framed with curly sideburns and wispy beard, his large eyes expressing gentleness.

He taught Talmud and Bible to the fourth grade of the city Talmud Torah, instilling the fear of God in his pupils, along with the other teachers in town. My friend, the poet Ephraim Lissitsky, told me that he obtained his knowledge of Hebrew grammar from Kadish the Melamed. In addition to his work in the Talmud Torah, Reb Kadish taught adults in the Kapashker Synagogue.

Mother told me that he used to teach the children of Reb Shmuel Leibowitz in the neighboring village of Podelipseh. (One of them, Reb Boruch Ber, z”l, served as rabbi in Halosk). He owned a farm in the middle of the town and paid Grandfather in part with various crops –

[Page 113]

including a wagonload of potatoes, which provided food for a long time. Mother and her brothers once transferred potatoes to the cellar by the light of a kerosene lantern that hung from a wall. Unfortunately, the lantern fell and the kerosene spilled on the potatoes. But the family ate the potatoes down to the last bite, despite the foul kerosene smell – so great was the family's poverty.

Grandfather used to walk by foot to and from the estate of Reb Shmuel. Once, in winter, the ice broke beneath him, and had farmers not heard his cries and rushed to his rescue, he would have drowned in the river.

His last years were difficult ones. The city passed back and forth a number of times – Russians to Poles, Poles to Russians. Once, during Soviet rule, he was discovered by a Jewish renegade teaching Torah to two grandchildren in the Kapashker Synagogue, and was arrested. He stood trial but was soon released because of his very old age. In the town it was said that both the informer and the judge were former pupils of his.

When our family emigrated to the United States, we urged him to come along. He deliberated, but finally declined, preferring to spend his final years in the city of his birth among other family members.

In his letters to us, he never complained. His youngest daughter and her husband provided him with respectable support. He was happy in the knowledge that his children and grandchildren continued to engage in Torah and mitzvot even in America.

On the seventh day of Pesach, 5686 (1926), he died, at the age of 75. The Jews of Slutsk paid him great honor, eulogized him as he deserved, and brought him to eternal rest among the most respected members of the community.

3. My Father's Life

Abba, of blessed memory, Rabbi Chayim Ze'ev Wolf Goldberg, was born in Kolna, Poland, to poor parents who eked out a meager survival from carpentry. Even though he was a young adolescent, he learned in the yeshivas of Lomza and Slobodka. Later he moved to the Etz Chayim yeshiva in Slutsk. His wife was Hod'l, daughter of Kadish der Melamed. When he was ordained as a rabbi, he acceded to the request of the illustrious Reb Moshe Mordecai Epstein to travel to America and raise funds for the Slobodka yeshiva. The New World and its democratic institutions found favor in his eyes, and he almost decided to remain there and serve as a rabbi. But he returned to Slutsk.

He chose not to make the Torah his means of livelihood. He did not return to the rabbinate upon coming back to Slutsk. He tried his hand at business, but since he never really understood the ways of commerce, he made nothing. Most of his time was spent in the study of Torah and books of Jewish ethics.

The outbreak of World War I opened many opportunities for massive assistance to Jews in distress. Abba took upon himself the responsibility for helping unfortunate co-religionists who suffered effects of the war. This was the acme of his activities during those “days of awe.” The large local population of paupers was swollen by refugees who fled border towns – entire families lacking all necessities, some of them affluent Jews who had lost their fortunes, women whose husbands had been conscripted into army service, leaving them and their children destitute, without means of support.

Infectious illnesses swept through the town. The problems of providing food, clothing, shelter, and medicine for the refugees occupied the energies of the triumvirate which devoted itself to public aid: Dr. Shildkraut, father and patron to all the inhabitants of the town, Reb Yeshaya Mendel Deretzin, an energetic public figure with a noble heart, and my father and teacher.

Daily they would supply flour or bread to the needy. Every Friday morning they would distribute two challahs for lechem mishneh for the Shabbat meals. (If my memory does not deceive me, the distribution took place in the Linat Tzedek office in the Cold Shul.). Father would 'hide' a few challahs to give secretly to householders who had lost everything, or to scholars and members of prominent families, so as to spare them the embarrassment of waiting in the queue.

Although father was rigid in religious matters, he valued the study of the Hebrew language and Jewish literature, and did not prevent me from studying Tanakh and reading modern Hebrew literature.

With the Bolshevik revolution, the situation in the city took a turn for the worse. The war between the Bolsheviks and the Poles brought ruination. When the former advanced, the town faced the danger of starvation, illness, and fear for the future of religious life. When the Poles advanced, life itself was threatened. The troops of the “Lerchikim” and the “Poznatchikim” molested Jews, killed them, wounded them, and plucked beards. Jews were hurled from trains. Many were murdered by hooligans in neighboring villages and brought to Slutsk for burial. Father fled to America. After three years he was able to bring over his family. But his connection with Slutsk did not cease; he helped support the yeshivas in Slutsk and in Kletsk. This is attested to by letters in my possession written by Reb Aharon Kotler and Reb Asher Sandomirsky, who was spiritual mentor in the Etz Chayim of Slutsk.

The following is a portion of a letter from the latter, dated 24 Tammuz 5683, after Reb Isser Zalman had been forced to leave:

“There are about 100 Torah scholars who sacrifice themselves, just as did our great leaders and sages of old in the days of the evil decrees. We can say of them, 'Should a man die in the tent…' [Midrash exegesis reads this as referring to "the tent of Torah", i.e., one who devotes his total self to the study of Torah]. This institution is the largest and most important, the sole remnant, which remains in all our land… God forbid that this holy institution be destroyed because of material causes.”

Father died in New York in 1935.

[Note by Kadish Goldberg, grandson and translator: ”After a short period as rabbi of Derby and Ansonia, Connecticut, my grandfather served as rabbi for the Orthodox synagogues in South Brooklyn, New York.”]

4. Dr. Leo Shildkraut, of blessed memory

Tall and broad-shouldered was he, and of noble spirit. He sought neither wealth nor honor. He acted for the public's welfare and for the good of the individual, in times of peace and in times of emergency. When he entered a house, he brought a spirit of respect, and he was received with great admiration and affection.

In winter he would appear in the patient's home, dressed in a fine fur coat, with a fur cap on his head. He looked like a Polish nobleman, but actually there stood before you a Jew who loved his poor brothers, and rushed to their aid in times of distress. In education and appearance he differed

[Page 114]

from the Jewish masses, but he understood their feelings and psychology; he spoke their lnguage, and he came close to them.

The poet, Ephraim Lissitsky, told me in New Orleans, how he fell ill with malaria as a youngster. He visited Dr. Shildkraut before the 9th of Av. The doctor commanded him not to refrain from eating meat.

For the welfare of the city's indigent, Dr. Shildkraut placed a closed contribution box in his waiting room, into which patients inserted the doctor's fees, each according to his ability. Sometimes, after examining a poor patient at his home, he would slip – unnoticed – a coin beneath the pillow. Upon leaving, he would say: “I left a prescription under the pillow, and I wish the patient a full recovery.”

He liked to jokingly say that one should believe in “techiyas hameisim,” the resurrection of the dead. “If a Jew can eat a large serving of cholent, take a deep nap – and still rise healthy and whole – is this not veritably a resurrection of the dead?”

Dr. Shildkraut was not a synagogue goer. But on Yom Kippur, he would come to the synagogue for the closing Neila service.

After the October Revolution, a plague of dysentery erupted. The situation was difficult. Many fell sick. Few doctors and little medicine were available. Medicines that were available were expensive. The gravest problem was lack of food to strengthen the body, and starvation claimed many victims. Dr. Shildkraut worked day and night without stop, not caring for his own health.

One morning, pairs of soldiers spread throughout the city, conducting searches. Officially, the searches were for contraband, but once set loose, the brigands did not differentiate between forbidden and unforbidden; they took all that came to hand. A great tumult arose; there was no one to halt the plunder. Suddenly, as if a miracle had occurred, the searches ceased. Rumor had it that Dr. Shildkraut had rushed a telegram to the authorities in Moscow, and from there an order was issued to stop the searches.

The above incident is deeply engraved in my memory, because a few days later, I went with Mother to one of the warehouses, where we signed a declaration that two sacks of flour had been confiscated, and the plunder was returned.

The battles between the Russians and the Poles over Slutsk left the community totally impoverished. There was no choice but to turn to our brothers across the ocean with pleas for help for looted, suffering Slutsk. The three heads of the community – the two rabbis and Dr. Shildkraut – sent a “Plea To Our Brethren In The United States.” Published in “Hatsfira” on 24 November 1920, it read:

“A Call For Help –From the Jewish Community of SlutskThe news that Dr. Shildkraut had suddenly fallen critically ill spread rapidly. That morning became sevenfold more painful when word came that Dr. Shildkraut was no more. Crowds flowed from all corners of the city to accompany him to his final rest. His coffin was brought out to the street, and a great silence hung over all. Thousands of spectators stood, silent and grieving. The huge mass stirred, the procession began. His coffin was carried on shoulders to the large modern hospital, and from there to the old “Hekdesh,” where lay sick indigent Jews, whom he had treated for decades.“Our brothers, hear us! Throughout the years of war, we suffered greatly, many misfortunes passed over us; we passed from regime to regime, our situation changing again and again. All sorts of disaster befell us. Our lives were in danger, and the fear of death was upon us. Stores were closed. The past four months brought great poverty. Travel came to a stop; we remained unclothed; we were all plundered. Recently we saw with our own eyes the blade of the two-edged sword, for the war was waged within the city itself. Arrows flew overhead, arrows of death, explosive arrows. Houses were destroyed, many people were wounded, many killed. Fires broke out throughout the city. The wall of the bathhouse was consumed by fire. The wall of the community and stores went up in flame. All institutions of charity, the orphanage, the old folks' home, and the hospital – all are in a deplorable state, without food, without clothing. Aged and young stretch out their hands for help. We have not the strength to meet their needs, not even with bread and water. The schools have closed down, for lack of salaries for teachers and of firewood for heating. They walk the streets, hungry, barefoot and unclothed, seeking help. But who can help them? For we lack everything. Householders whose hands were once open to help those who ask and beg, now themselves have become those who ask and beg.

“Now, our brothers, our own flesh and blood in America, our eyes are turned to you, our hands outstretched: Help us in our distress. You know what you must do. Hurry, tarry not, for we have no strength to do anything. We lie before you like a stone that has no one to turn it over; it is your obligation to save us.

Sunday, 27 Cheshvan 5681, Slutsk Dr. L. Shildkraut Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer, Head of the Beth Din and the Yeshiva Our Rabbi and Mentor, Rabbi Meir Funds should be sent to the Slutsk Community through the Community of Warsaw.”

At the cemetery, he was eulogized by Rabbi Avraham Yitchak Shisgal, z”l, a student of the yeshivas of Slutsk and Kletsk. He had barely begun to speak, with great emotion and sad voice “… we had a precious pearl, and it is lost to us…” and immediately all groaned and wept. On of the speakers, Rabbi Yosef Peimer z”l, praised the deceased and said that in his life he sacrificed himself upon the altar of his brothers and fellow citizens, and now he was like a “korban olah,” a sacrifice offered totally to God. Upon hearing this, one who “denied the covenant” jumped up, as though bitten by a snake, and publicly insulted the rabbi. A scandal almost erupted at the graveside, but the Rabbi, despite his humility and shyness, was not deterred by the insolent fellow, and continued to eulogize the saintly doctor.

by Baruch Domnitz

Translated by Jerrold Landau

How much splendor is exemplified in this name – Slutsk – for me. How numerous are the memories that are evoked within me when I hear that name. In the eyes of my spirit, I see its gardens and alleyways, people and rabbis, synagogues and yeshivot full and bustling from morning to evening, worshippers and studiers; pure, dreamy Yeshiva lads who streamed not Slutsk from the nearby towns to learn Torah from the great Torah sages who lived there: the Ridba'z and Rabbi Meirke, Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer and Rabbi Nechemia, Rabbi Yosha and Rabbi Michla, Rabbi Berl from the Karnaim, and others.

That city was filled with merchants, shopkeepers, tradespeople, and intelligentsia. It had strong active movements: Bund, S.S. [Zionist Socialist], Poalei Zion, as well as Zionist parties: General Zionists headed by Leibush Gutzeit, with Alter the Shochet, Reuven Altman, the Ratner and Lifschitz families, and others. Some succeeded in making aliya to the Land and others did not. There was Tzeirei Tzion [Young Zion], including Avraham Yitzchak Shpilkin, who signed his name in short as “Ish,” Avrahamele Ratner, Yosef Eliyahu Rubnitz, and Shmuel Noach Landau, whose black eyes sparkled with wisdom, and who had a heartwarming smile on his lips. In addition, there was the lone teachers for Hebrew: Chazanovich, Gutzeit, Katznelson. That groups also included the older youths who studied in the gymnasja, including the dear female members who worked with dedication and at times wit risk to their lives: Fania Karpach, Eshka Leb, Sonia Zimering, Henia Arenbaum, Ruchama Itzkovich, as well as girls of the youngest age, such as Rachele Bergman of blessed memory, who died in her youth at the age of 18 from a cold and pneumonia. She got sick while running in the cold and rain to collect money and provisions needed for our members who were in jail, and from standing for many hours next to the jail to give over the packages in person to our members. How bright were her blue eyes from happiness when she told me every detail of her mission, how she managed to slip notes into the biscuits and bagels, etc…

|

|

View of the landscape atop the bridge to Kolonia |

Slutsk – a city of Torah, labor, and commerce, all together. It is situated on the Sluch River that passes through Polesye and reached the Pripyat, passing through forests and bogs for a distance of hundreds of kilometers. Who does not remember its beauty? The nighttime sailing of boats on the river to Kolonia, and from there onward; the laughter, singing, and mischief, spiced with youthful charm, the secret longing for love, the secret kissing, caresses with a soft, delicate hand, and quiet conversation in the moonlight on spring nights.

At a distance not to far from Kapolya, as it continued on, there was a small agricultural farm called “Shulka” that wholly belonged to a Jew, Reb Yisrael Shulker, and was called by the name of the Land of Israel. On Sabbaths, festivals, and during evening hours, we loved to stroll in that area, which was fully traditionally Jewish and was only working on weekdays. Its trees, pathways, wide pastures with flocks of cattle walking peacefully and eating the pleasant soft grass for enjoyment would imbue you with a sort of special pleasant, calm mood that is hard to forget even at this point. There, we also wove our dreams for Zion and Jerusalem, for the fields of Israel in the valley, the Galilee, and on the Jordan, that is a hundredfold more beautiful than the Sluch.

[Page 116]

We loved to stroll in the quiet alleyways, with fruit trees on both sides – cherries, pears, and apples – with their intoxicating aromas in the spring, and whose leaves turn yellow in the pleasant autumn days, suffused with sadness and silence.

From there, the roadways to Kolonia, and Vigoda spread out, with expansive vegetable gardens, almost extending to the nearby village.

There – is the main road in the center, the highway, with two broad sidewalks, which served as a separation, one for the Bund on the right side, and the other for the S.S. and Poalei Zion on the left side. In the center of the street was the café of Solomiak, with his large belly. It was bustling until midnight with people eating ice cream and layer cakes, drinking cold beer – as well as just a general group of “loafers” who were chatting and joking about Slutsk and its gabbaim, about “America” street and its harlots, about its crazies, wagon drivers, and porters.

On Sabbath and festival days, the street was bustling with people strolling, men, women with their children, brides with their grooms, people walking arm in arm, cracking seeds, as the brides were glancing in every direction. The group of “barefooters” was also not lacking, who would stick pins into the backs of the single girls, to their great laughter and joy. That group was organized by Benny Manyuk the tailor, who had seven sons, left to themselves in a wanton manner, for the parents did not have enough energy to supervise them. They were called “the ten sons of Haman,” which caused no small among of pain to the elderly Manyuk, who was almost half blind at the end of his days.

Vilna Street, also called Charpashker Gasse (meaning Street of Shame[1]) on account of its crosses and icons that were situated not far from the old synagogue with thick walls built of stone and brick, was also well-known. Torah scholars, wise people, and the religious intelligentsia worshipped in that synagogue.

The Street of the Smiths, di Shmideshe Gasse, also had a unique appearance and a characteristic way of life. It was an alleyway that included most of the smiths of the city as well as the various wagon manufacturing workers. From early hours in the morning, while all the city was still resting with their sweet morning sleep, that street was already bustling and noisy. The trotting and neighing of horses, the sounds and echoes of heavy anvils hitting the hot iron, the crackling of the sparks, and the blowing of the bellows could all be heard. All this created a unique, encouraging harmony, the song of work, instilling hope into the person, into the Jewish energy. There, you would meat the Jewish worker, earning his living from his toil, the broad-boned, muscular Jewish worker. These were pure, simple, people, who often stood on guard to protect the honor of the city and Jewish honor from hooligans.

We remember the days, every year, during the months of the drafting of new recruits in October and November. This when the youths of the nearby villages who were designated to join the army would gather in the city. They would wander through the streets of the city and the market, and pilfer merchandise from the stalls of the grocery stores and confectionaries without paying. They would also attack old, weak people on the side alleyways.

Then the lads would come: the smiths, the wagon drivers, the tanners, and the carpenters, the group of beaters [klapers], and would take revenge upon these villagers, show them the force of their arms, and teach them a bit of respect and fear of the Jews, so that they would know and remember.

The following are words about interesting, characteristic personalities in our city of Slutsk:

Reb Leibush Gutzeit

He was a communal activist and an enthusiastic Zionist, who loved the Hebrew language.

With his wide heart and generous hand, with the Jewish pain in his dark eyes, that serious Jew, openly and secretly assisted the individual and the public without seeking honor, without any haughtiness. His large quantity of property was confiscated by the Bolshevik government, and he remained only as a director of his large Chipley estate and director of the alcohol distillery and large sawmill, in which only Jews worked, numbering a hundred or more. He greatly helped out friends who were imprisoned in the jail for the crime of Zionism and teaching Hebrew. He generously supported the community, which had become impoverished during the time that the switch from the Polish to Bolshevik regime.

|

|

Reb Leibush Gutzeit |

I will never forget the moments that I took leave of him as I left Slutsk. When I told him the “secret” of my aliya to the Land, the man wept from a combination of great joy and pain. “If only I could” – he spoke quietly and with emotion – “ If only I could escape and wander, even as an indigent, and go to the Land, I would be happy. For what has been perpetrated against me, and what is left for me from all my great fortune… You are fortunate that you have merited this. Go up and succeed, and do not forget me.”

His words were spoken in Hebrew, with strength and a stormy soul. They shook up the strands of my heart, and I took leave of him with agony and great pain. When his property, the flourmill and large sawmill, were confiscated, the workers granted him a good turn, and due to them, he remained as the director of work. They left him a horse and buggy for his needs, as a memory that the world is a revolving wheel…

[Page 117]

Reb Chaim Yehoshua Friedman

He was a scholar, and knew Russian, German, and Polish. He was expert in the Talmud and Zohar. Every day after the Maariv service, he would read lesson of Talmud with great proficiency and astounding simplicity. His proficiency in world literature was very great. He would frequent the house of rabbi Abramsky when he was in Slutsk. He was the mouthpiece of the community before the authorities. The elderly man merited that at least one member of the entire family, his grandson Shmuel Friedman, made aliya and lives in Tel Aviv.

[2]Itze Nota's the Melamed was known as an expert scholar. For the most part, he could be found in the home of Rabbi Isser Zalman. He concerned himself with the needs of the studiers. He took care of the Yeshiva students with love, and arranged for them to partake of their Sabbath meals in the homes of various householders. Itze Nota's brother was Rabbi Yosha Tritzaner, the head of the Yeshiva in the Kloiz.

Itze Nota's wife Tila Grozowski was considered to be a righteous woman. She would collect money and supported anyone in need. During the time of the Soviet regime, she would bake bread secretly, with danger to herself, and transfer the bread to the Yeshiva students.

She continued her blessed work even after she arrived in the Land. She collected money and supported anyone in need of assistance. She was the gabbai of Heichal Hatalmud and the Or Zoreach Yeshiva. She also founded Gemilut Chesed in Tel Aviv.

Michael Wilenchok

He was a flour businessman. He was expert and sharp. He loved to ask many questions and delve into didactics with his learning. He was an upright man, and a zealous Zionist. When I was already in the Land, he wrote me a letter, asking me to send a certificate [for aliya] to his daughter. To my great sorrow, however, I was unable to do so.

Yosef Rekiner

He was Shpilkin's son-in-law. He was a modest, upright man. He was a scholar, a Zionist, and he knew Hebrew.

Yeshyahu Mendel Derechin

He was a haberdasher. He was a Yeshiva student during his youth. He was diligent. He partook of his meals in rotation [yamim] and suffered, until Feigele came along, with the warts on her face. She was a businesswoman, the daughter of a family of merchants, and she turned him into a man. Derechin's name went before him, for he was trustworthy, upright, open hearted, and generous. He set aside times for the study of Torah, and he occupied himself with charity. He discreetly collected money for the poor and for scholars who suffered from lack. On Mondays and Thursdays, he would distribute food to poor Yeshiva students and to all who were hungry: bread, cheese, salted fish, and hot tea in the morning; potatoes fried in duck fat without meat, and lentil soup in the afternoon; and five kopecks for a meal in the evening. He did this as a remembrance of the verse: I recall the days of my poverty and suffering. Later, he moved to Baranovich and became a large-scale merchant. There too, he organized assistance activities: Gemilut Chesed, Small Credit. He helped Jews in their time of need. He was a sublime Jewish character.

All this was during the times of his wealth and greatness, until the Bolsheviks came and afflicted his life.

Leibe Yoich

The elderly smith Leibe was a unique character. He was known as Leibe Yoich – i.e. Soup. He was given this name because on every Sabbath eve, he tied a leather sack on his back, carried a large pot in his hands, and made the rounds to the doors of the wealthy people to request “challa mit yoich” (bread and soup) for poor women who had just given birth, or for regular poor people who were unable to “make the Sabbath” in the manner of the householders.

He was a strong Jew despite his great old age. He was broad boned, with warm, good, penetrating eyes. His face was adorned with a thick, straggly beard, which was, apparently, never combed. His peyos were curly. He wore a black, oiled kapote that went down to his heavy boots, polished with tar, exuding an aroma in honor of the Sabbath.

His sons lived together with him with their families, and worked together. They honored the old man, and waited for him on Sabbath eves until he had finished his rounds, and sat down to recite kiddush on a cup of wine. The elderly Leibe loved the drink, the cholent, the kugel, and the Sabbath hymns. He would enjoy spiritual contentment on the Sabbath, which quietly descended upon him on the street of the smiths, from the eve of the Sabbath until Sunday morning, when the street once again woke up to regular weekday work.

Dovidl “Kvartalner”

Among those who cared for the needs of the poor was Dovidl, a unique character. He was a beggar the son of a beggar for generations. His mouth was crooked on the right side. Four teeth protruded upon his thick lower lip. He was half blind in one eye, and the other one squinted sometimes to the right and sometimes to the left. His nose was closed and red. His mucus dripped both in the summer and the winter, and he would wipe it with his sleeve or the corner of his wormy kapote.

He had a red cane, which he used at night. During the day, the man would run. He would run as if someone were chasing him. He held a red handkerchief in his left hand, spread out to the sides, “A donation, a donation, dear Jews, a donation.”

Poverty and lack pervaded in his home. There was a great deal of mildew and rot with him, but all this did not stop him from being concerned about others. He was especially concerned about the Yeshiva students, who partook of their meals in daily rotation. Everywhere he went, he would receive [a commitment for] a set day of food for lads suffering from want.

Among the righteous women, it is worthwhile to mention Rachel, the wife of Yankel Poliak. Two sisters sold milk, Esther and Malka, as well as many others. The charitable organizations were Bikur Cholim [tending to the ill], Hachnasat Kallah [tending to poor brides], Lechem Aniyim [providing food for the poor], Kimcha Depischa [providing Passover supplies], and others. Tens of men and women gathered around them, not concerned about their time, doing good for the public. Rebbetzin Margolin, who concerned herself with Jewish prisoners in the city, continued to concern herself with Jewish prisoners here in Tel Aviv as well as in Jaffa. The police already know her, and always permit her to freely enter the prison yard and give over the kosher food and money that she collected for the prisoners.

[Page 118]

Leizer the Shamash

He was a short Jew, with a thin face and inquisitive eyes. He served as the Shamash of the large Beis Midrash for decades. He was careful with his words and mannerisms. Everything happened in accordance with his word.

He was the Gabbai of the Linat Tzedek organization. When he would borrow utensils for the indigent ill, such as bloodletting vessels, icepacks, etc., they told him, “Reb Leizer, you are indeed the Leizer – the redeemer of all tribulations.”[3] He was goodhearted, and when his cheerful daughter Chaya Reizel became involved in Zionism, he said, “You will bring full healing and redemption to the People of Israel, and me – to the individual. The public is composed only of the individuals.”

The Soviet regime that became entrenched in the city mercilessly oppressed the Jewish population, and imposed harsh decrees and heavy taxes. The Kalte Shul [Cold Synagogue] was confiscated and turned into a grain warehouse. The holy utensils from the synagogues, the crowns, the silver letters atop the curtain, the silver reading pointers, and the copper basins were confiscated. Foreclosure was imposed upon the treasury of the Chevra Kadisha, and they demanded money from the funds raised from synagogue honors [aliyot]. Melamdim [religious teachers] were banned, and the property of the Hebrew schools was confiscated. Only a few Hebrew teachers remained, who taught Hebrew clandestinely and privately to Jewish children. The teacher Chazanovich was forcefully drafted, and was forced to teach in Yiddish.

I was removed from the ranks of the Red Army and sent to the Pedagogical Teknicum in Minsk, where I studied for a full year and then returned to Slutsk. I worked as the supervisor of the Yevsektsia and principal of the trade school for carpentry and sewing. They also gave over to me the large civic library, which was supervised by Efron Meisel. Thanks to the trust they placed in me, I took advantage of the opportunity to the extent possible to remove Zionist literature in Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew from the library and distribute it to our members, friends, and acquaintances. The books that I did not succeed in removing remained hidden away in the archives. It was only possible to obtain Hebrew books with a special permit. The supervision was strict, but nevertheless, I knew how to make arrangements with Efron, for he knew Hebrew and appreciated its literature. He still had a Jewish spark within him, even though he was a former member of the Bund, and then transferred to the Yevsektsia.

Necha (Nechtzka) Shapira was the main superintendent of the schools. We suffered many tribulations from her. She was a hardened, strict woman. The teachers wept secretly over their bitter fate. She related well to me, for I would visit her father's house, and also had served as a soldier in the Red Army for two years.

In 1925, I requested that they release me from all my tasks, and I made aliya to the Land. My personal documents remained with the G. P. U.[4] because they thought that I would still return to Russia. They confiscated many of my books on the pretext that they are superfluous, and I would have no need for them in Palestine.

Despite the oppression and spying, clandestine Zionist activity took place specifically among the youth. They arranged meetings during the day and night, in the fields and in the cemeteries, where they divided themselves into small groups of five or six individuals. The spying also did not pass over me, but thanks to my strong personal connections between me and one of my students, Avrahamele Hertzman, I was saved and did not fall into the hands of the authorities.

There were several other Communists who did favorable things for their friends and acquaintances. They were Communists externally, while secretly adhering to Judaism its traditions.

One of these was the red haired Vofka, the son of Malka the milk woman. When his eldest son was born, he came to me to ask for advice as to how to arrange a circumcision. I arranged the circumcision in my house, at night, behind closed shutters and windows covered with curtains, in the present of several trustworthy individuals. Malka beamed with great happiness and wept tears of joy as she prayed silently for the welfare of the baby who had been entered into the covenant of Judaism.

This Malka was goodhearted in an unparalleled fashion. With her last coin, she helped everyone in trouble or with a bitter soul.

Slutsk merited to give its portion to the Second, Third, and Fourth Aliya. Many Slutsk natives can be found in Tel Aviv, Haifa, Jerusalem, Petach Tikva, and various kibbutzim. Among them are teachers and writers who are well-known within the community.

We also had a great share among the victims who fell in the founding of the State. There is no comfort other than building our young, dear country, and in our great hope for a brighter future of a life of happiness and peace.

Translator's footnotes:

by Tzvi Chazanovich

In memory of my revered father

Translated by Jerrold Landau

The Hebrew School, the “Modern Cheder” had great value in the realm of Hebrew and Zionist education. It had a good, dedicated teaching staff. Some were writers, or at least people who knew how to write. They invested great energy in imparting to their students a love of the Hebrew language, a connection to Zionism, and a longing for the Hebrew homeland. Their efforts bore fruit to a large degree: Many of their students tied their lot to Zionism, the Land of Israel, the pioneering movement, and clandestine work. Some were imprisoned, deported to desolate places, or even expelled from the country. Many rebelled and rejected the doctrine that they had studied. Nevertheless, the fire still smouldered in a few of them, who maintained their faith with the Hebrew language, albeit in secret. However, the flame was completely extinguished in many of them. They turned their backs upon what they learned, regarding it as nationalism, reactionism, and opposition to the essence of the great Russian Revolution, acting as a brake to its wheel. Therefore, they felt it their duty to fight against it and extinguish it.

The fate of the Hebrew teachers was bad and bitter. With the strengthening of the Soviet government and the rise of the Jewish Yevsektsia that persecuted with anger any Zionist and Hebrew manifestation within the Jewish population, the Hebrew schools were closed, and teaching of Hebrew was prohibited. The source of livelihood of the teachers was broken. However, there were still some teachers who endangered themselves and clandestinely taught Hebrew. Such teaching was fraught with great danger and deep difficulties.

[Page 119]

And now, the image of my revered father, Mordechai Chazanovich, floats before the eyes of my spirit. He was the principal of the modern cheder for many years, and he taught students of the Russian high schools on a private basis. He was strongly tied to Hebrew culture and literature, and he educated his children and his children's friends to Zionism and love of the language.

I recall the gatherings of Hebrew teachers in our house next to the steaming urn, as they discussed various topics. I also recall Father's visits to the teachers Avraham Epstein, Zeev Gutzeit, Berger, Katznelson, and Nachamovich (Nachmani).

The atmosphere was warm and homey. In the latter period, it was suffused with silent sadness, with hints and foreboding of the approaching disaster[1] that was about to take place over the heads of the Hebrew teachers.

Indeed, that which the teachers suspected did come:

A ban was imposed on the Hebrew language, and arrests began. A Yiddish school was founded in place of the Hebrew school. My father was enlisted against his will to that school due to a shortage of experienced teachers.

He was forced to teach Yiddish according to the new Yiddish orthography, with his heart dripping blood as he saw the purpose of his life – teaching Hebrew – liquidated.

This weakened him. He expressed this in his letter to me in the Land.

In 1924, I was imprisoned for the third time, and deported to the Land. There was a constant mail correspondence between Father and me until his death at the beginning of 1948. His stormy spirit was recognizable in sections of his letters. He expressed his longing for the Land, for Hebrew, and for a life of freedom. The political viewpoint that he had to express in order for his letters to pass through the censor also stood out.

He was precise, made points, asked about new words, fixed expressions, pointed out my mistakes, and also tried to sneak in conspiratory facts in concealed language regarding the fate of my friends who were arrested and deported to far-off Siberia.

In his first letters, he writes:

“It has been many years since I have seen a Hebrew newspaper, a new Hebrew book. A Hebrew word has not been written to me, nor have I written to others Now, for the first time in a long time, I am writing in Hebrew: To who? Not to a friend, not to an acquaintance, but to you, my dear son! Can I describe my joy, my emotions to you?“I drink with thirst any information, any news from the Land. Everything interests me, enthuses me, and involves me. Everything is new, for in truth, I do not know what is happening in the Land. I do not know was a kvutza, a kibbutz, a moshav, or a moshava are? What is a pluga? I do not know the many factions in the Land or their plans? I wish to know the population of Tel Aviv and of the entire Land? How many new immigrants are there every week, what is the harvest of the fields, do they grow fine wheat? How many dunams of Land do the Jews possess in the Land? What is with the new Hebrew literature and the authors? How is Bialik, and does he continue to write?

“And how can I know all this, if I have been cut off from everything for so long? Here, there are no factions, there is no Purim, there is no Passover, religion is dying. In general, you yourself know the situation here. From the time you left, the order of things has not changed.”

He began to dissect my expressions in several letters, and make notes:

“Regarding punctuation, punctuation was not given from Sinai. It was created, if I am not mistaken, during the Geonic period, in a later time, and therefore it is not holy for us. It is open to correction, and it is permitted to tamper with it. How much more so are we required to make efforts to ease the reading and study for young children.“However, the researchers, linguists, writers, and teachers will decide on this question. They will seek ways to improve the language. Efforts should be made that the changes should be appropriate to the principles of punctuation and morphology. Who am I to be so brazen as to place my head into the thick beam?

“Regarding the recommendation of Itamar the son of Ab'y to transfer to the Latin script, this recommendation seems strange in my eyes. Do we not have a unique alphabet? It is an imitation. It is liable to lead to a loss, and I do not know who can justify such a recommendation?”

In one of his letters, he writes:

“There are multiple benefits in my Hebrew writing. My soul that has become naked finds its rectification. My style is renewed, sharpened, and strengthened. Many expressions, formulations, adages, and verses that were forgotten and have been removed from my essence have come to haunt me: How can you not be embarrassed, o son of man, how many years have you tended to us, and now, you have turned your thoughts away from us. I clearly see that from the time I began to write in Hebrew, I have recalled its ways. Indeed, there are many words that I find difficult, especially the new words in your letters, but I am happy that I can still remember that which I have forgotten.

N. N. left the Land and returned to Slutsk in 1928. He brought with him bad reports about the Land. Father walked around confused. He wrote me: “N. described the situation to me in black colors, to the point that my hair on my head stood on edge: ‘In the Land they are dying of hunger. There are no possibilities that the situation will change. The labor is backbreaking. People only earn a bit of bread and a meager amount of water. The Slutsk natives in the kibbutz do not eat to satiety. They look like skeletons.'”

These words had great effect on those whose children were in the Land. Many did not believe his words. Baskin (Shabtai's father) said he would be satisfied if he were able to obtain a visa for his son. Father asked that I write him the truth to refute the false words.

After the first group of Slutskers made aliya to the Land, many of the members of our movement remained in Slutsk. Some were imprisoned. Father responded in an elusive manner to my question about their wellbeing and their deeds. When he wrote about the wellbeing of my relatives, he would also include the friends, as follows:

“The situation of the rest of the relatives, such as Moshe, Feivel, and Eidelman of Minsk[2] is very bad. This is an unfortunate family. It seems to me that it numbers about 15-17 people. They do not work, they do not study, they are sick.”

And in another letter:

“For Shraga[2], they purchased a fur already before the Passover holiday,

[Page 120]

fine and long, so that even in the 40 degree cold, I am sure that if he wears it, he will not feel the cold. Regarding the wellbeing of Uncle N.[3]: that which he earned from shechita, he earned into a bundle with holes. I was told that there is discord and conflict, hatred, and grudges among the family members. One like to eat such and such a food, and N. likes to eat Kurtza[4]. Therefore, many family members battle with him, curse and blaspheme. There is confusion, perplexity, and discord in everything.“I am happy that you are not in prison, that you are living a life of calm and peace in the Land.”

Father wrote often about political matters. He was forced to praise the regime of Stalin. However, it was possible to read entirely different things between the lines.

This is what he wrote in 1946:

“Apparently, I am close to 70 years old. I have already become old. Many of my 248 limbs[5] have been afflicted. I am now reading ‘The History of the World’ – ancient and modern history. I am making connections, forging links, coming to conclusions, and making logical comparisons, a fortioris. In no way can I understand how the Jewish problem can be solved in the Land of Israel. It can only be done through the doctrine of Marxism or international politics. It is easy to solve the problem in accordance with the doctrine of Lenin and Stalin. However, until the ideal is clarified, ‘and the wolf shall lie with the lamb’[6], it is possible that the wolves and the leopards may maul the lambs.”

In 1947, he writes from Leningrad:

“I went to the synagogue on the last day of Passover. I saw many Slutskers there. I stood the whole time at the threshold of the Beis Midrash, and cold not move from the place, for the house of worship was full to the brim. I found an old Gemara, and peered into it. I reviewed a certain Talmudic section, and it interested me more than the service. I cold not read Ki leolam Chasdo [for His mercy endures forever][7] at the time when Hitler and his friends have murdered approximately six million Jews, the elderly, women lads, and children. Let people read the prayers and pour their words out to the Omnipresent, but I do not believe that ‘prayer alone’ can avert the evil decree.”

Father did not merit to be alive when the Hebrew state – the desire of his life – was founded. He died a few months prior. I still succeeded in writing to him about the vote at the United Nations, the decision regarding the establishment of the State, and I described to hi the joy of the Jewish community and its successes.

My teachers at the modern cheder and the Hebrew teachers in general did not succeed in reaching the Land, other than a few who left Russia before and after the First World War. They did not merit to be present for the wonder – the creation of a Hebrew state. However, their toil was not for naught. Many of their students set up deep roots in the Land. They we always recall with gratitude their alma-mater, the modern cheder.

Translator's footnotes:

Translated by Jerrold Landau

Avraham Yitzchak Shpilkin

|

|

From right: Dr. Yaakov Tzvi Lifschitz, Avraham Yitzchak Shpilkin, Nachum Chinitz |

He started off as a Sofer Stam [A scribe of Torah scrolls, tefillin, and mezuzot]. For the most part, his friends would find it at his worktable, bent over parchment folios of a Torah scroll. The aspiration of his soul was Zionist and cultural work. His personality and external appearance aroused attention. He was modest and unassuming, but sharp with his speech. He published sharp feuilletons and poetry on issues of the day in bulletins that appeared in print. He used the signature I'sh. Indeed, he was a fundamental man, an autodidact who developed and obtain communal stature in time.

His father Reb Ben-Zion was a Sofer Stam, an upright man. His mother Esther Malka, the daughter of the renowned Tzadik Reb Rafael-Yosel, inspired him from the womb.

Their house was a gathering place for Zionists, and clandestine Zionist activity. The man suddenly stopped his work as a Sofer Stam and began teaching Hebrew in Tymkovich and later in Slutsk. He was active and vibrant in the Tzeirei Tzion movement.

The Soviet authorities remembered the sins of his youth: Zionism and Hebrew teaching. He was imprisoned for a certain period. He was a craftsman from his youth. When he was freed, he worked as a shoemaker, having no other options. His heart always pined for Zion. In his letters to his friends in the Diaspora and the land, he shook up the hearts of the readers with his sublime longings.

As the Nazis approached Slutsk, he wandered off to Soviet Armenia. His wife Keila the daughter of Reb Yosef Jaronson was killed along the way, and he died in the Diaspora. May his memory be a blessing!

Reuven Altman

He was educated in the Yeshiva of Slutsk. He was a Zionist activist, faithful to the Hebrew language and its literature. Hebrew was the spoken language in his house. He opened the second modern cheder in Slutsk together with the teacher Katznelson. It existed until the outbreak of the Soviet revolution.

His letter from 1932 that he sent to his brother Eliyahu Altman in America testifies to his experiences during the time of the Soviet regime. During the Holocaust, his fate was the same as that of all the Jews of Slutsk, who perished at the hands of the Nazis.

May his memory be a blessing.

[Page 121]

|

|

Next to the grave of their father. Reuvke Altman is in the center. Minka and Eliyahu (Zeidel) are on the sides. The gravestone reads: Here is buried a dear, honorable man Yehuda Leib the son of Reuven Altman. Died on Sunday 12 Shevat 5676 [1916]. May his soul be bound in the bonds of eternal life. |

May 3, 1932My dear Eliyahu!

I received your last letter, and I thank you for it. In general, the day I receive your letter is a holiday for me. It arouses in me forgotten memories, memories of my childhood and youth. I am now writing you a letter as if life is passing before all the times that we spent together in the home of or parents, and all the events. Here it is your birthday. Do you know where you were born? In some ruin. This was after the fire. Our house was burnt. We found a ruin in which people had not lived for years because of the danger. You were born there. We made some sort of canopy in the yard, and your circumcision took place there.

Another image passes before me: I am in the “Storeve” as a teacher of Jewish students. I go outside and from the distance, I see some young lad in yellow clothing. I was surprised. It seemed that these were the clothes of my young brother, but how did he get here? I drew close, and indeed it was true. He had come to some wedding with the musicians.

Now they are taking me to army service, to fight against the Germans. I was in the middle with other prisoners, and we were surrounded by soldiers. I looked back, and our late father was accompanying me with tears in his eyes. I fought, I returned, but I did not find him. I did not merit to be present at his death.

In general, the image of our late father is etched very deeply in my heart. He was of the character of Bonche Shveig[1], or those who are miserable but not miserable. I too have many of the traits of our father. I, along with you and Minka, are standing next to the gravestone of our father, photographing ourselves. The photo came out fine. I still have it, and whenever I wish to forget about the present a bit and turn to the past, I take out the photo and pass it before me.

All the days of my life have passed like a dream. Now I am looking at the picture of my children and seeing how big and lovely they are. My Yitzchak is already 22 years old, and Yeshayahu is almost twenty. It was just yesterday that they were small children, and I carried them in my arms. In previous days, I walked to the synagogue with them and talked to them in Hebrew. I wanted Hebrew to be their spoken language. Now, they are men with different concepts, men who have taken upon themselves the goal of destroying the old and building a new world. They are building a new life, and I see how small I was with the idea that I bore in my heart of building a home for the Jewish nation. My children desire to build a full world, a new world, and a new life!

I sent you a photo of my children. Why have you not written me that you have received it, and what it was like before your eyes? We now have sadness in the soul. It has already been two years since my Yitzchak has not been at home. We waited impatiently for him to come this summer. Now they have sent him to work in the city of Khabarovsk. Look on a map and see how far away it is[2]. A letter from there takes about three weeks to arrive. I already considered Leningrad as his second home, and then they came and destroyed my nest. Thus, our family members are scattered in all directions, to the four corners of the land, and I have already become old. I already have white hair on my head. I am a man without energy or initiative, and I still have to toil with physical labor to earn a loaf of bread.

You wrote in your letter that I am angry at you. I do not know why you suspect this? Is it because I do not write that much. If so, that is because I do not always have time. You remain the only one with whom I can speak what is in my heart. For all my acquaintances have scattered in all directions. Different people with different ideas are around me, and I cannot mix with them. When I am in their company, I am like a mourner among bridegrooms. I wanted to write to you about your acquaintances, but there are barely any. Only Shpilkin remains. He is a shoemaker, and works in the Artel. The sins of his youth, as well as mine, cannot be mentioned or verbalized. The destruction and ruin in our spiritual lives is much greater than in our economic lives. Not even one child can be found who knows how to read Hebrew, or who can understand even one word of Hebrew. Only the Kloiz and the Karnaim remain of all the synagogues and Beis Midrashes. So, it is enough for now. Be well, and see good things.

Your brother who wishes you well,

Reuven

Henia and Liba inquire about your wellbeing, and the wellbeing of your wife Sara. You have asked about our sister. Do not worry about this. Her situation is strong. He[3] is no longer a worker. He is the director of a large cooperative store, and she has everything.

The aforementioned.

[Page 122]

Moshe Yericho

My father was an upright, goodhearted man. The residents of Slutsk loved him and called him lovingly – Mosheke the Feldscher.

He was a medic by trade. He was dedicated and faithful, dedicating all his energy and strength into his patients. He cared for them with love, comforted them in their illnesses, and eased their pains with a pleasant countenance. He did not differentiate between the rich and the poor. He did not consider their status, as he concerned himself with them.

He was the assistant of Dr. Schildkraut. They were cousins, and they enjoyed good relations. They worked together for 25 years.

|

|

Reb Moshe Yericho (der Feldscher) and his wife Gittel |

They both got married in the same year, and they also both died in the same year. Schildkraut died three days before Passover, and father died three days after Shavuot. Indeed, they were not separated during their lives and their deaths.

Reb Yosef of Tshernichov of blessed memory

Reb Yosef Tshernichov of blessed memory was the son of Reb Yehuda Leib and Rivka, the daughter of the praiseworthy rabbi of renown, Rabbi Yossele Peimer the first.

He was born in Slutsk in 1868 and perished in the Minsk ghetto. He studied in cheders, and continued to study Torah throughout his life.

He was a well-known grain merchant. He was close to the common person and easy to get along with. He distributed charity generously. He had an adage: “If a person knows how much he distributes, his deeds are not for the sake of Heaven.” Before Passover, he would amass full warehouses of flour for Passover [matzo] and potatoes, which he would distribute to anyone in need.

He would sit in the synagogue on Kapolya Street every day until noon and study Torah. The landowners of the area already figured out where he was sitting, and would come to the synagogue courtyard with wagon hitched to four horses to clarify and conclude various business matters with him.

He had a business sense, and a special understanding of the grain business.

He would export grain to Germany for large sums of money until the First World War. He exchanged letters in Hebrew with the well-known agents (commissioners) in Koenigsberg, Ephraim Rosenberg and Lifschitz.

He lived frugally[4] and spent time in the tents of Torah in suffering and difficulty. When his son complained: why does he suffer and not benefit from life? Is it possible to sit secretly and suffice oneself with secret gifts? His response was brief: “G-d commanded those who fear Him to make their soul like dust.” “Behold I have dared to speak to G-d, and I am but dust and ashes.”[5]

Indeed, he made his soul like dust. He endured various tribulations. He was imprisoned in 1931. He moved to Minsk in 1932. His property was confiscated. He wandered to foreign places, and was deported to far-off Kazakhstan. When he returned to Minsk, the hand of the Nazis came upon him and his family, who went up on the pyre along with the martyrs of Minsk. “Make my soul like dust” was fulfilled with him.

“And I am but dust and ashes.”

May his memory be blessed!

“Der Salanter”

That is what the second rabbinical judge in Slutsk was called. He worshipped in the Karnaim Synagogue. He was of average height, and a shiny black beard adorned his face. His pure eyes expressed uprightness and wholesomeness. He did not speak much, was taciturn by nature. He nodded his head and uttered some sort of a silent prayer with every tribulation. When there was good news, his eyes brightened and his entire being expressed joy and gladness, as his lips uttered: everything is in the hands of the Dweller On High, Who is capable of everything!

May his memory be blessed!

Shimshon Nachmani (Nachaminovich)

He was born in 1885 in Horozava. He studied in cheders and the Yeshiva of Slutsk. He was a student of Gershuni of Minsk. He was one of the founders of the modern cheder in Slutsk fifty years ago, one of its first teacher, and the instiller of the Zionist spirit.

He was injured and beaten over the head by a Bundist ruffian while he was selling Zionist stamps in the Slutsk cemetery on Tisha B'Av.

He moved from Slutsk to Lyubar, where he taught in the Hebrew school together with his friend Kagan.

After a few years, he made aliya to the Land. He taught in Poria in Tiberias and Safed. After that, he transferred to the Neve Tzedek school in Tel Aviv.

He merited to be one of the layers of the foundation of a Hebrew school in the Diaspora – one of those who revived the language in the Diaspora and the Land – the educator of an entire generation.

After he left Slutsk, he taught Hebrew in the Mafitzei Haskalah school in Rozhichov and Kyiv. He translated twenty books from Russian: Haseara by Ilya Erenburg, (workers Library), “Far from Moscow” (Am Oved), and others. The book Hatayas Hakita was not translated, but only translated by Sh. Nachmani as is noted in the inner cover.

He participated in Kuntrus and Davar.

He was the chairman of the organization of natives of Slutsk and its environs.

[Page 123]

Eliyahu Yarkoni (Greenfeld)

He was born in Slutsk on 24 Elul 5646 (1886).

He studied in cheders and the Yeshiva of Slutsk. He moved on to Haskalah. He was examined in the government gymnasja and was certified as a public-school teacher. He taught in the modern cheder of Slutsk for about a year. He made aliya to the Land in 5672 [1912], and was accepted to the teaching staff of the Neve Tzedek girls' school. He also taught evening courses in Hebrew.

He had the good fortune of coming across the mother of settlements, the oldest school in the land, which is the Pik'a[6] school.

|

|

Eliyahu Yarkoni (on the right) and Sh. Nachmani |

The First World War broke out before he was able to strike roots in the Land. Many at that time “went down to Egypt” and did not return to the Land. Mr. Yarkoni remained. He suffered hunger, wandering, and deportations during the final years of the Ottoman government. With the liberation of the southern portion of the Land by the English and the establishment of Hebrew brigades, Mr. Yarkoni changed from a man of the book to a man of the sword. He left behind the staff of the teacher of young children and took up the gun in order to actively participate in the liberation of the Land from the Turkish oppressors.

He stood on guard of that elementary school for more than 45 years with boundless faithfulness and dedication, with the exactitude that was typical of him, and with the diligence that few in the modern times can even conceive of.

It was clear to him that he must also teach nature and agriculture along with all the other subjects that he taught, so that he could bring the students close to the soil and landscape of the native Land. He was one of those who laid the foundations for the education of the generation.

The disturbances in Petach Tikva during the 1920s shook him up to the depths of his soul. From that time, he took the duty of broad defense of his Moshav upon his shoulders. His days were dedicated to Torah and education, and his nights – to communal affairs and local defense.

Mr. Yarkoni educated generations of students who are spread out today in all areas of the Land. They include teachers, guiders of the youth, government officials, and those who conquered the homeland. Many of his students, including senior army captains, participated in his retirement party that was hosted for him by the veterans of the defense in Petach Tikva,

Yarkoni merited to be one of the founders of the modern cheder in Slutsk, and to stand by the cradle of Hebrew education in the Land. He was among the builders and forgers of the image of the elementary school.

Not only this, but with his many tasks, he was the director of the teachers' division in Petach Tikva, and he was active for the Keren Kayemet [Jewish National Fund]. He visited the school daily and took interest in everything that happened there.

Congratulations to him!

Dr. Shraga-Feivel Meltzer

He was a teacher in the Mizrachi teachers' seminary, a school principal, and a member of the leadership of the community council in Jerusalem. He was born on 25 Adar 5657 [1887] in Kovno. He was the son of the Gaon Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer. He moved with his family to Slutsk. He was educated in the Yeshivot of Slutsk and Slobodka, the University of Berlin, and the Mizrachi teachers seminary in Jerusalem. He was a communal activist, and a member of Young Zion in Poland.

He was in the Land from 1921. He was a Mizrachi activist in the Land, and active in various communal committee. He served as the emissary of the Keren Hayesod to Eastern Europe in 1935. He lectured in the Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan Yeshiva[7] in New York. He was granted the degree of Doctor of Literature at the university of the Yeshiva of Rabbi Yitzchak Elchanan [i.e. Yeshiva University]. He currently lives in Jerusalem, and lectures at Bar Ilan University.

Rabbi Dr. Moshe Chiger

He was born in Slutsk, and was the grandson of Reb Shachna.

He studied in the Yeshiva of Slutsk and then in Kletzk and the Yeshivas of Mir and Slobodka.

When he arrived in the Land, he studied a page of Gemara daily privately with the Gaon Rabbi Isser Zalman Meltzer.

He was in Africa[8] for several years as a teacher, and was granted the degree of Doctor.

He lives in Jerusalem and serves as a (Torah oriented) lawyer.

Translator's footnotes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Slutsk, Belarus

Slutsk, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 16 Sep 2024 by JH