|

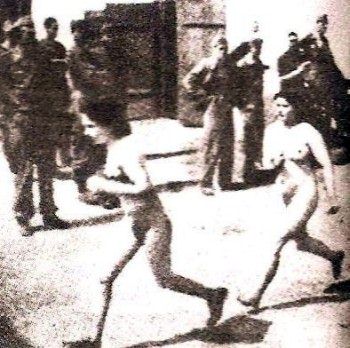

“Everything else was a game. This was the true contest. With your stomach turning and breath thin, you ran – beneath the throb of the lying music – for your golden life”[10]

|

“Everything else was a game. This was the true contest. With your stomach turning and breath thin, you ran – beneath the throb of the lying music – for your golden life”

When the Krakow Ghetto was liquidated, Julius Madritsch transferred 232 men, women and children from Krakow to Tarnow on March 25 and 26, 1943. On September 1, 1943, the Tarnow Ghetto came to a brutal and violent end. The day before the liquidation, Madritsch and Titsch were invited to a ceremonial dinner for Commandant Goeth and other high SS officials. When Madritsch requested to leave, SS-Obergruppenfuhrer Scherner ordered him to stay until dawn and left him with two SS officers to keep him company.[2] At 5 am on the following morning Madritsch and Titsch were released. They drove directly to Tarnow, where he saw Goeth. Goeth informed them that the Ghetto had been liquidated and was no more. Goeth assured Madritsch that his workers were safe for the time being. Large bribes weren't offered but were demanded by Goeth and Scherner. Madritsch later noted that there had been a fierce resistance in the Ghetto and that many Jews had been shot. All Jews who survived the onslaught were transported to Birkenau and gassed. Only the Madritsch Jews survived.[3]

Like Schindler, Madritsch was taking dangerous chances to protect his Jewish workers. Never did a week go by when these two entrepreneurs didn't risk their luck for the sake of their workers. Madritsch refers to many instances of help he received from the Wehrmacht and, in particular, a sympathetic German officer named Lt. Col. Mathisen, who assisted in evacuating Jewish families to safe areas.[4]

It seems the bigger the lie you tell the more chance you have of getting away with it. Stern, Pemper, and Schindler decided on an audacious ploy. Mietek Pemper (69514), who worked in Goeth's office, had seen the report from Oranienburg requesting that an immediate list of inventory of machinery and prisoners be made. In his position as administrator of the workshops, Stern compile a highly inflated projection of production in the camp. All this information was printed neatly in book form, with many graphs and drawings. Pemper submitted the material to Goeth, who immediately checked it. He found the information was incorrect and raved over the fraud. Then, according to Pemper, he laughed and said nothing. In an odd way, Goeth, Schindler, Bejski, Stern, Bau, and Pemper got on well; accepting the status quo was in the interests of everyone. Goeth knew that this was an effort to save the camp and obtain concentration camp status. As it was also in his interest, Goeth signed the account, which was sent to Berlin.[5]

Some days later the camp was visited by a team of statisticians from the Main Office in Oranienburg to check the projected productivity of the workshops. The team was headed by SS Obersturmfuhrer Mohvinkel and his assistant, a German Huguenot named LaClerc. The books and plans were scrutinized, while Stern and Pemper could only wait and hope. The inspection was short and sharp. Stern was at the beck and call of the inspection team, kept busy bringing books and plans as requested. Stern did not flinch; he was respectful, direct, and cool. Stern knew that he had the responsibility on his shoulders to ensure the safety of the camp.

At the end of 1943, still no decision had been made; now everything depended on receiving orders from the Wehrmacht. Plaszow's output was mainly through their tailoring shops, but to survive they needed to transform the workshops into metal stamping and press machinery. Goeth sought the help of Schindler; after all, it was in everyone's interest that the camp's status be upgraded. Frantic work went on in Plaszow, to be ready for an inspection that was to take place shortly. On the last Sunday in December 1943, a high-powered inspection team, lead by SS Obergruppenführer Krüger arrived at the camp. The inspection team toured the camp with Goeth.. In the workshops, which Schindler had realized would not stand scrutiny, he made a special arrangement. As the tour commenced there was a sudden blackout in the workshop. The inspection went ahead in the gloom so that everything appeared enhanced. Whatever the assumptions, it appeared to have worked. In fact, Schindler had arranged for the electricity to be cut during the early stages of the inspection.[6] In January 1944, Plaszow was designated “Konzentrationslager,” under the central authority of SS- Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl's SS Main Economic and Administrative Office in Oranienburg, the outskirts of Berlin.

Plaszow's change of status brought a slight relief to the prisoners. No longer were there to be summary executions. Everything had to be sent to Berlin in triplicate, and hearings and any sentence had to be confirmed by the new head of Department D, SS-Obergruppenführer Gluecks.

Mieczyslaw Pemper[7] had a photographic memory, and for many months had been memorizing the highly classified documentation that went through Goeth's office. Over a period of some weeks Pemper had pieced together secret information transmitted from Gerhard Maurer, Hitler's Chief of Concentration Camps, to the Commandant of Plaszow. The information was depressing. Several thousand Hungarian Jews would be arriving at KL Plaszow, and room was to be made for them. Goeth was frantic as Plaszow was already overcrowded.[8] Goeth asked permission to cull the camp to make room for the necessary space.[9] Gluecks authorized this course of action in another memorandum, which Pemper just happened to memorize. KL Plaszow was to disperse its labor in all directions and to give up its excess to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Pemper's contribution in this war of information cannot be underestimated. Goeth's personal secretary was a young Polish girl (Keneally refers to her as German - Frau Kochmann), who was very efficient in her general work but who, because she had problems when inserting multiple sheets of papers and carbons in the typewriter, always asked Pemper to help. On many occasions he would slip in an additional piece of carbon paper and retrieve it after the typing had been done. By holding the carbon to a mirror, Pemper was able to clearly read the most secret information. This extra carbon would be spirited out of the camp via Stern and Schindler. Schindler then passed to the Jewish agencies in Budapest this vital information which was central to the West's grasps of the Hungarian transports.

Amon Goeth had been busy, and under the code name Die Gesundheitaktion (the Health Action) he set about the partial liquidation of KL Plaszow. Space for 10,000 had to be made in the camp. Auschwitz was working over capacity, but would be able to take these Hungarian prisoners in a matter of weeks when the pressure of the crematoria had subsided. The selections at KL Plaszow began on the morning of May 7, 1944. On the Appellplatz, row upon row of prisoners, in barrack formation, stood silent. They knew it was their last chance. Block by block they were marched to the reception area. Ordered to strip naked, as each name was called out the prisoner presented himself or herself to the examining teams of doctors headed by the SS Dr. Blancke. Also assisting in this selection was the collaborating Dr. Leon Gross. The women had to line up and walk forward, one by one, and jump over a series of large holes that had been especially dug to test their level of fitness and, therefore, their right to survival. Prisoners were made to run up and down in front of the examiners. Some women who were suffering from chronic diarrhea rubbed red cabbage leaves into their face to give them color. [Mrs Chana Kinstlinger (76328)]

|

|

“Everything else was a game. This was the true contest. With your stomach turning and breath thin, you ran – beneath the throb of the lying music – for your golden life”[10] |

During the course of the SS Aktion, Goeth turned his eye to the 280 children housed in a separate compound (the Kinderheim), where working parents could bring their children up to the age of 14. Cared for by experienced personnel, the children were kept busy and safe. Now was time to deal with the children. Sensing trouble, Goeth sought reinforcements from Krakow. Parents seeing their children separated and confined without the opportunity of proving their worth began to wail and scream for their loved ones. There was panic and pandemonium everywhere. Whole families were separated in the selection, some to the left, some to the right. No one knew, for sure, whether they were on the good or the bad side. To the experienced prisoner it was not difficult to guess; looking at the group which contained the elderly, the sick, and the disabled was a sad realization.

Some children, the urchins of the camp, had their hiding places already prepared. Even so, when they dived for cover they would find that their space had been taken by someone else, and they ran in frantic search for another sanctuary. To the inexperienced child, it would be complete panic: they would stand in the open and believe themselves invisible.[11]

On May 14 all became clear. The day everyone knew their fate, standing to attention on the Appellplatz. There was an air of sad resignation around those selected for transport. Those Jews not selected for deportation were distressed and saddened seeing their parents, grandparents, children, and friends marched off to the waiting wagons destined for Auschwitz. It wasn't uncommon for mothers, in order to protect their teenage daughters, to change coats and join the column marching out to the transports. The individual camp number sewn in the breast of their coats was sufficient identity when being checked by the guards. During the course of the action, dance tunes and lively music were broadcast over the loudspeakers, providing a musical background for the sick and the young children who were being sent to the ovens of Auschwitz. As the Jews marched to the train, the radio technicians, with their sense of Germanic humor, could be heard singing the German lullaby “Goodnight Mammy.”[12]

Schindler visited the camp a few days after the main transports had left. He was dismayed to see another transport of several wagons[13] in the siding, guarded closely by the SS. This transport was destined for Mauthausen. On this very hot day, with the heat shimmering off the roofs of the wagons, the wailing and shouts for water could clearly be heard. Outraged and in the presence of Goeth and his posse of SS officers, Schindler persuaded the Commandant to allow hoses to be directed onto the wagons. A shimmer of steam from the locomotive broke into the air. Schindler played probably one of his final cards by imploring Goeth to allow this indulgence, much to the mockery of the SS present. As in the Spielberg film, Schindler brought in additional watering appliances to quell the heat of the wagons. He gave the guards on the transport baskets full of liquors and cigarettes and requested that at each stop the prisoners should be given water and the doors opened. Well after the war, two survivors of that transport, Doctors Rubenstein and Feldstein, confirmed to Schindler that this was done.[14]

The selections and transports made in May, to make way for the 10,000 Hungarian Jews, were the most difficult accounts for many of those that I interviewed to relate. The late Dr. Moshe Bejski had to have several breaks in the interview before he could bring himself to complete his account.[15]

Footnotes

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Schindler - Stepping-stone to Life

Schindler - Stepping-stone to Life

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 7 Sep 2007 by LA