|

[Page 107]

Ever since the letter by Count Ferenc Eszterházy on May 10, 1748, permitting the establishment of a Jewish community in Pápa, for almost two centuries the relationship with followers of other religions was excellent. There are many instances to be quoted in connection with this friendly and intimate state of affairs:

In 1840, the Jewish community raised money for the statue of King Matthias and decided to contribute 400 forints to the local Protestant High School, an excellent Hungarian institution. In 1846 the patron of the town contributed 100,000 bricks to the construction of the new Jewish temple.

In 1848 the patriotic sermons of Lipót Lőw were attended on Shabbat by students of the Protestant High School and the Theological Seminary at the Jewish temple. In 1872, a beautiful house was donated by Pál Királyföldi, a landowner of the Lutheran faith, for the purposes of a Jewish school. In his will, the same person also left 500 forints for the school. The annual pages of the Protestant High School always contained the names of Jewish contributors who supported the Relief Association.

Roman Catholic abbé Néger never missed visiting community president Adolf Lőwenstein at Simchat Tora in order to participate in the party given by the president for the members of his community. Community president Adolf Lőwenstein left in his will 500 forints to the town to feed 10 poor Catholics, 10 Protestants and 10 Jews every year at the anniversary of his death.

Lutheran bishop Ferenc Gyurátz greeted the newly elected rabbi by a speech in Hebrew.

Calvinist bishop Géza Antal often went to see the merchant Zsigmond Beck, a respected community member, to talk with him in an intimate, friendly manner.

On pleasant spring evenings we often saw Henrick Blau, principal of the Jewish higher elementary school, walking arm in arm with Baldauf, the Lutheran bishop's secretary (who later became the bishop of Pécs).

Adolf Karlowitz, the secular president of the Catholic Church and the brother-in-law of the bishop of Vác, employed a Jewish woman in his pharmacy, exempting her from work on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

Jewish students were exempted from writing on Shabbat at the Protestant High School, at the Calvinist Boarding-School for Girls and at the Public Higher Elementary School for Girls.

The Protestant High School made it possible for Jewish students to attend Shabbat morning services for youth at 11 A.M. on a regular basis.

Non-Jews made up 40 % of the students attending the Jewish higher elementary school.

József Kraft, a teacher at the Roman Catholic teacher training college, would carry books for observant Jewish students from the eruv [a symbolic fence denoting Shabbat boundaries for carrying objects] to the school gate.

The Pápa district court had no proceedings on Shabbat out of consideration for Jewish attorneys. For decades, Jews filled the posts of the municipal health officer and veterinarian.

The friendliness generally felt towards Jews was not disturbed by the antisemitic wave of the 1880s. When in wake of the Tiszaeszlár blood libel a hired band of György Istóczi organized a demonstration near the Jewish temple in preparation for a pogrom, it was dispersed by Jewish tanner and butcher apprentices joining forces with their Christian friends.

After the Communist rule of 1919, in the days of the White terror, the flames of officially generated antisemitism reached Pápa as well:

three Pápa Jews were executed in the woods of Devecser, the dentist Dr. Róbert Blum, József Steiner and Bienenstock. The teacher Izsó Várhelyi was badly beaten up. When the news came that the lower town was preparing for a pogrom, Jewish youth gathered armed with sticks at the call of the Stern brothers (József, Imre and Géza), under the leadership of Gyula Breuer.

The dark clouds scattered slowly and life became normal again. The rise of the Arrow Cross in the 1940s brought this period to an end After the showing of the antisemitic film Jud-Süss, a riot broke out, windows of Jewish homes were broken, and there was fighting in the streets with the military involved, leaving many wounded by bayonets. Following the German occupation, the end was drawing near: all contacts were severed and no one stood up for Jews. Yesterday's friends became today's enemies. Movie owner Ede Gobbi, the father of actress Hilda Gobbi was a rare bird: he saved a great number of forced labour servicemen. Another rare bird was Lieutenant Csanaky, the principal of Tókert, who remained a human being when people turned into beasts: his forced labour servicemen remember his humanity with gratitude.

However, this chapter should be closed in a sad tone; the words of the psalm came true: they repay me evil for good (psalm 35:12).

Only the pages of this book will tell posterity that Jews used to live in peace with followers of other religions in Pápa.

[Page 109]

by Sándor Lőwenstein

It was like a dream. Or was it a dream really? They were standing by the entrance, it was a relatively good camp, they were wearing a mixture of work clothes and their Sunday best, with open trench coats, expecting new arrivals with the usual excitement of looking forward to something new: to get updated by the newcomers and to go, or rather to fly to their support.

Rumour had it for some time – spread by kitchen staff and those in charge of slicing bread – that somebody was supposed to arrive from our town. They were restlessly milling around, old-timers humbly pulling together their fully grown wings, while greenhorns fluttering their miniature wings which had hardly started to grow. They were not nervous. At last they did not have to be afraid of a husky voice saying “I have been watching you for a long time!”

They had no feelings of fear or revenge, they were free from vanity. The only ambition left in them was not an earthly drive to get to better housing or camp “where the spoon is stuck in the mush”: it was a purely disinterested longing for the higher spheres, to approach absolute purity.

An angel on duty was approaching with a drone like a Stuka. The letter shin on his armband identified from a distance his belonging to the guards. Haberdasher Henrik Steiner, who was a pure soul already on earth, called out to him:

“Where are you going, Comrade-in-Joy?” “I am bringing you someone from Pápa. I am in a hurry, I have to go”, he shouted down to him and disappeared in the purple clouds.

“I told you it was no rumour”, said Tibor Német. Although Tibi was a newcomer, he was immediately accommodated in the barracks of the purified and was told the news even before the archangels. The tension was growing. At noon Sanyi Vértes angrily slammed down the gold mess-tins in the kitchen, because only a few had come for lunch, due to the excitement and the fast.

The company got together only between mincha and maariv on the gravelled yard of the temple. There was hardly anybody on the benches, despite the fact that their favourites were supposed to give lectures in the weekly program called Pele Yoetz: the names of rabbis Róth, Link, Pressburger, Eckstein, Gottlieb, and Haberfeld possessed no attraction for them that day. The situation in the Bet Hamidrash was not any better: rabbis Áron Pressburger, Dirnfeld, and Rapoport were the lecturers there.

Before the appearance of the three stars, Samuel Bodánszky – called Shmuel the Long up in heaven – flew rustling his wings through the trellis gate of the temple yard. Even the saints in the highest circles knew that he had spent his last years and his fortune in support of Polish, Slovak and Austrian refugees. “They will arrive in a second”, said he, rushing to the temple to reassure Uncle Stein, who was quite nervous.

The efforts of Tuvia Biedermann, hiding his wings humbly under his cloak, were useless; his believers were too much of a handful for him that day. He had the title of temple father for life, but he did not take it seriously, spending his time with community policies and visiting the nursery school in the afternoon to play with the little ones. Auntie Julcsa had her eyes on him in vain: he stuffed his pockets with candies, stealing out of his store to distribute them among children, most of whom had been killed in the gas chambers. All of a sudden Uncle Marton and Eizig Gestetner sailed in gracefully through the Eötvös Street gate, holding the newcomer under their arms, then with a clever maneuver gliding over the heads of those waiting, put down the frightened-looking barminan (corpse) on the temple steps. However, as they tried to take him to Uncle Baum in the entrance hall to get his personal data recorded (a person who is not recorded in the chevra book has no name), he was surrounded by a huge crowd. The strict voice of the beadle Deutsch and the attempts to persuade them by Uncle Rosenberg proved futile. The poor soul was harassed from all sides, some were even pulling at his kitel, asking what's up in Pápa. “I don't know a lot because I was staying at a hospital in Pest”, the newcomer tried to excuse himself, “and then I was not taken home because there is no chevra kadisha there anymore, as you probably know.”

“What? No chevra kadisha? How come?” They were appalled. “Where are you living, in the clouds? ,Even the temple is being used as a storehouse and there is no minyan.”

They were struck speechless. With tearful eyes, poor souls were walking down the aisle and getting to their seats on the benches, hanging their heads silently in deadly sorrow. Uncle Marton slowly reached his place at the mizrach and fussily got seated. Baal t'filah Uncle Stein looked back from his pulpit over the talit to see if everybody was settled, and in a husky sobbing voice started to pray: “Vehü rachüm yechaper ovayn, velay yashchis…” And a dreadful choir wept together with him: “Ve-hu rachum yechaper ovayn – velay yashchis…”

I went through a lot of horrors during the blood-soaked years, but the most depressing story I can remember was the following:

After the German occupation, we were languishing in a camp at Újdörögd. Our camp commander Captain Gilde, with some traces of aristocratic background, was replaced by an even more dismal character, a neuropathic and sadistic major whose name I cannot remember. (May his memory be erased.) During a search that lasted for an hour, when our glorious guards with the help of gendarmes with sickle feathers on their helmets even robbed us of our stamps for mail and we were close to collapse after standing at attention, this major summoned one of his henchmen and asked him: “Tell me sergeant, how many Jews did I take to the front in 1942?” “225 Jews, Sir, I humbly report.” “And with how many did I return?” “16 Jews, Sir, I humbly report.” “Did you hear it, Jews? It will happen to you, too”, the Hungarian Royal major bellowed, foaming at the mouth.

However, the major did not achieve his purpose. Our thoughts were flying in another direction. For the past few days we were getting farewell letters from our families before the deportation, letters which were passed by Sándor Szilágyi, the cadet with syphilis. First the letters were arriving from the periphery, then the ice-cold hand was reaching up more and more. After such a distribution of mail the amiable Rabbi Sofer, a dayan from Sopron who slept next to me, handed over his letter to me with a white face. His family, his children were saying goodbye to him. This frightened little Jew, this hero who deserves a monument, continued to comfort our frantic comrades, with superhuman self-control, and tearful eyes. At night the choked sobbing under the blankets got stronger. We tried avoiding each other's eyes. Then on a painful day, the first farewell letter from Pápa arrived. It was our turn. Like forlorn lambs sensing danger chassid and non-religious, got together. Without previous consultation, the precentor started spontaneously praying Avinu Malkenu. Comrades gnashing their teeth and covering their ears were running up and down in the barrack, like moths flying around the fire; eventually they all ended up in the middle of the howling crowd. The whole barrack was writhing in a terrible frenzy. The shaliach tzibur of our community, the gentle and blond Tsodek Stein, with eyes rolling, was beating his breast with one hand, while the other hand was in a cramp, grasping the air. There was no mercy!

Together with his ten gentle and blond children, he became a statistic. When the precentor screamed “chamol olenü veal alolenü vetapenü” (take pity on us, and upon our children and our infants), the walls of the barracks were shaking, and from that point, it was sheer madness. There was no mercy! The brave guards were standing at the door astonished, they did not dare enter. The exhausted bodies collapsed on the plank beds; they had no strength left for crying.

Then we were also taken to the wagons, along the looted ghetto, among the mocking remarks of the gloating mob at Tapolca. Our brothers in Pápa were deported on the same day. Through the crowded windows of the wagon, we were watching the bombs flying around us. They failed to hit us. There was no mercy!

The death sentence of Hungarian Jews was put into effect by the German occupation of the country on March 19, 1944. On April 6 the medieval sign of mockery, the yellow star, had to be sewed on clothing. It was forbidden to go out without it. Those who failed to do so were punished. On one of the first days, clothes dealer Bernáth Altmann stepped out of his store - without the star - in Kossuth Street, Pápa in order to speak to a provincial carter selling firewood. It was only a few steps, it took only a few seconds, but it was enough for his internment in the Sárvár camp, where he met lumber dealer Zoltán Bodánszky, a most pious Jew.

The following Jews were also interned:

M. Jenő Kohn, owner of a cement-plant, because of ZionismDr. Lajos Pápai, veterinarian, together with his wife

Lajos Friebert, manager of the Bacon meat factory

József Steiner, engineer, brick manufacturer in Tapolca

Ármin Leipnik, textile manufacturer

Dr. Emil Guth, attorney

Lajos Pátkai, landowner.

None of them returned, their fate is unknown.

Pápa Jews were locked into the ghetto on June 1, after the destruction of Jews in the Upper Province (Felvidék) and the deadly blow the hated Nazi army received at Stalingrad. The last service was held in the ancient temple on the second day of Shavuot. It was highly dramatic to listen to the chazan singing yizkor, although they did not know, only felt that it was the last prayer in the old synagogue.

The sermon was given by chief rabbi Jakab Haberfeld, who died a martyr.

The elected community board was disbanded, and a five-member Jewish council was appointed to be in charge of Jewish affairs, for the single purpose of executing the harsh orders.

The ghetto was set up in Petőfi, Eötvös, Rákóczi, Szent László and Bástya Streets; it was monstrously overcrowded. The ghetto had two gates: one in Rákóczi Street near Kossuth Street, the other in Bástya Street near Kis Square. When the Jews were taken away through these two gates, they had their bundles checked: not only their jewelry was taken away, sometimes, at random, their only change of underwear was confiscated as well.

Jews were beaten up, slapped and tortured to reveal their allegedly-hidden fortune and jewels.

There is no use arguing that it all happened at German orders. How can you defend the shameful behaviour of Lord Lieutenant István Buda? When he visited the ghetto with his attendants and saw the maternity ward set up by gynaecologist Dr. Kornél Donáth, he burst out:

“It is much too beautiful for stinking Jews, I will see to it!” This beast in human form had no time for action because the ghetto was liquidated. Dr. Glück and his wife Lucy, the pharmacist, committed suicide to avoid cruel tortures in the ghetto.

Junior civil servant Dr. Pál Lotz was the commander of the ghetto in town. This corrupt figure escaped to the West after the war. In Switzerland he was a hotel manager, but when he was informed that he was a wanted person, he fled to Australia. He lived in an unknown place, under a pseudonym.

Pápa Jews were transferred from the ghetto in town to the fertilizer factory. There the ghetto was under the command of police captain Dr. Zoltán Pap. He executed the orders in such a cruel manner that later he was sentenced for 12 years by a military tribunal.

Two thousand five hundred and sixty-five Pápa Jews were taken to the fertilizer factory, where they were joined by three hundred Jews from the districts of Devecser, Zirc and Pápa. There were two Jews in Pápa who were exempted from the anti-Jewish, fascist decrees: Miklós László, who dealt with technical appliances and Pál Frimm. Both were 75 percent disabled and were awarded the gold medal for bravery. Each had lost a leg in the First World War. They did not have to go to the ghetto, or move to the artificial fertilizer factory: as exempted persons, they were permitted to stay in their apartments. Miklós László had his 13 year-old son with him. They lived in Pápa in constant fear until October 15th. After the Szálasi takeover, the two exempted men and the 13 year-old boy were sent to the internment camp in Komárom castle by junior civil servant János Horváth and Pál Lotz, who first confiscated their cash, jewelry and clothes. The commander of the castle in Komárom, however, respected their exemption, and sent them back to Pápa with a document saying they were exempted from deportation. When they returned to Pápa, they went to report to the police station. The two junior civil servants had the two war invalids and the 13 year-old boy taken out and shot in the street.

This terrible act of horror was only an episode of the Holocaust. Out of the 2565 deportees only 300 returned home. The number of murdered children was 671.

On July 4 and 5, they were crammed into wagons.

The bells were not tolled, neither in the temple of the Catholic vicarage on the Main Square (Főtér), nor in Anna chapel. The bells of the new Calvinist church on Jókai Square stayed silent as well, despite the fact that Jews had contributed to their purchase. The bells of the Lutheran church in Gyurátz Ferenc Street were not sounded either. There were no admirers of Ady to run with them, as the great poet foretold it in his poem A bélyeges sereg (The Branded Flock):

There were no neighbours with tearful eyes to accompany them; the grateful clients, students and the patients saved by Jewish doctors were absent. Only the sound of revels with gypsy music could be heard from the train station restaurant: it was a great day for Pápa gentlemen, the Jews of Pápa were being led to their death.

Gypsy music and the sobbing of the victims blended into a symphony of hatred.

The deporting trains arrived at Auschwitz, via Budapest, Hatvan, and Kassa, on July 8, which was Tammuz 17 according to the Hebrew calendar: on this historical anniversary of mourning their destiny was fulfilled.

According to the legend, Moses broke the two stone tablets on that day, but only the cold stones were broken: the words of the Decalogue flew into space. Only one word reached the Nazi empire, the last word of the sixth commandment “Thou shalt not kill“, the word kill! reached the Satanic empire. And they killed murdered, butchered old and young, mothers and babies. And on that day they murdered the Jews of Pápa in gas chambers.

And now we, the survivors, can weep and lament with Jeremiah:

“Alas – she sits in solitude! The city that was great with people has become like a widow.”

None of her lovers remained to comfort her; all of them betrayed her, her friends turned into enemies.

We must preserve the memory of this ancient, sacred community.

Remember and don't forget!

The customary way names are presented in Hungary is family name followed by given name.

Wives were and still are called by their husbands' name with the addition of -né, often followed by the wife's maiden name.

This is seen in the names of the first two martyrs:

“Adler Ignác”,

“Adler Ignácné – Spitzer Jolán”, (p. 119) sometimes presented as for example Stein Davidné, sz., or szül. (short for born) Vogl Sarolta (p. 144).

“Özv., short for özvegy” = Hungarian for widow (or widower), here it is used for women only.

For example on page 119 it appears: Özv. Adler Sámuelné = widow of Adler Sámuel

“Munkaszolg.” short for munkaszolgálatos, a man who served in a forced labour unit called “labour service”. These men were already away from Pápa at the time of the community's deportation.

“(50%-os) hadirokkant” = 50 % invalid resulting from WW I war injuries (p. 124).

“Hadi özvegy = hadi özv.” = WW I war widow (page. 126), also “honv. özv.”

“Eltünt” = disappeared (p. 127).

In some cases there is an address added to a person, e.g. “Hoffmann Miksa, Petőfi u.” when there is another person by the same name on the list (p 129, see also Stern József, p 142).

“...és családja” = ...and his family (p. 132).

“Anyja” = His mother. (p. 135).

“Mayersberg Zoltán, 1943 május 14-én Dorositsban elpusztult” = Died on May 14, 1943 in Dorosits. (p. 136).

“Fia” = his son, (p 138)

“Reichenberg Johanna – férjezett Tannenbaum Miksáné” (p. 140). married to Tannenbaum Miksa

Sometimes a name is followed by expressions other than family members' names (probably not known).

“2 gyermekével” = with her two children,

“1 fiával” = with her 1 son;

“1 leányával” = with her 1 daughter (p. 147).

“és családja” = and his/her family (p. 157).

“család” = family.

“3 unokája” = with her 3 grandchildren (p. 158).

“és ennek menye” = and her daughter-in-law (p.158).

“és 3 tagu családja” = and his 3 member family (p. 158).

“3 fia és 3 leánya” = her 3 sons and 3 daughters (p. 158).

“..hitk. metsző hitvese és gyermekei” = wife and children of the community's mohel. (p. 158).

Page 156, right hand column, second block:

“Felsőborsodpusztán 1945 Március 9-en kivégzett munkaszolgálatosok” = Forced labour servicemen executed on March 9, 1945 at Felsőborsodpuszta is followed by 7 names and hometowns.

Oblivion is the way to exile

Remembrance is the secret of redemption.(Baal Shem Tov)

Not the buried one is dead,

Only those are dead who are forgotten.(The Blue Bird by Maeterlinck)

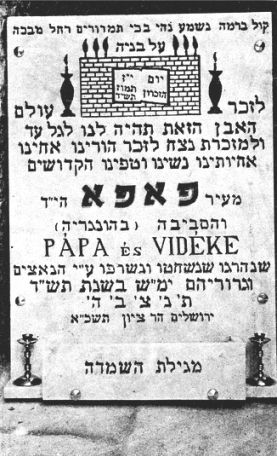

This plaque commemorating the martyrs of the

Pápa Jewish community in the “Holocaust Cellar”

“מרתף השואה” on Mount Zion in Jerusalem

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Pápa, Hungary

Pápa, Hungary

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 5 Sep 2009 by LA