|

|

|

[Page 9]

Eastern Mazovia

In the several centuries before the Holocaust, the districts of Mazovia were witness to a vibrant Jewish life, so much so that one would have imagined that these were pure Jewish areas where Jews had lived forever. However, these areas were settled by Jews only much later than other areas of Poland. At a time when Jewish communities in eastern and western Galicia, in Pomerania and Volhynia, already had a distinguished past and a tradition going back hundreds of years, it was still forbidden for a Jew to settle in Mazovia. While Jews traveled the roads of Mazovia, peddled in its villages, knew its byways, most of the cities in this region were bereft of any Jews. Special laws that were renewed periodically absolutely prohibited Jews from living anywhere in old Mazovia, which sprawled over major portions of central Poland.

Mazovia retained a certain level of political independence since the establishment of the Kingdom of Poland, at which time central political institutions--weaker or stronger--had been set up. Its rulers and the few citizens who had special rights meticulously preserved these special rights, and viewed any attempt to settle Jews in Mazovia under royal edicts as a threat to their efforts. The clergy of the Catholic Church, which was very influential in this region, perhaps even more than elsewhere, was particularly vigilant in observing the ban on Jewish settlement in the territory of Mazovia. The clergy was consumed with flaming anti-Semitism and never ceased to take pride in its attainments in this realm, and in its success in preventing the settlement of Jews in any place where its influence was decisive, especially in eastern Mazovia.

The fact that Mazovia, despite its fertile lands, was weaker economically than other regions of Poland, very likely because of the absence of Jewish initiative and trade, did not influence the firm position of the Church or the rulers of Mazovia. They were more interested in the independence of the region than in its prosperity.

Up until 1360 the kings of Poland were not even recognized by the dukes of Mazovia. While legally subject to the kings of Poland, in fact the dukes were semi-independent. Only from this period on did the dukes of Mazovia swear allegiance to the Kingdom of Poland at the time of the coronation of its new kings, but ties with the institutions of the monarchy were weak. The kings of Poland worked diligently to bring Mazovia under their rule. When a duke of Mazovia died without sons or legal heirs, the kings of Poland would rush to incorporate his realm into the state. In 1462 when a noble who ruled the County of Rawa died, the kings of Poland absorbed the areas of Rawa and Gostynin into their kingdom. Two years later they took Sochaczew [Sochachow] and its environs, and thirty years later Plotzk [Plock] and Ostroveh. It was only from this period on that the kings of Poland would crown themselves as the being the rulers of Mazovia as well, a Polish region populated by Poles located in the very heart of central Poland.

From the time Mazovia was absorbed into Poland, the latter's laws applied. The szlachta, members of ruling noble families, received the same rights as their counterparts in other parts of Poland. But over and above this, the province maintained a series of special laws, in particular as regards the Jews, who had been given privileges by the kings of Poland.

Mazovia was divided into three counties (voivodeships) [literally, circuits], Rawa, Plotzk and Czersk. But their rulers continued to view themselves as a united authority

[Page 10]

representing all of Mazovia. Ostroveh already enjoyed the status of a city. Boleslaw IV, Duke of Mazovia, had conferred upon the town the status of a city in 1410. But it was a small city of no particular importance, located in the midst of a great, dense forest sprawling over hundreds of kilometers.

The Three Counties of Mazovia

While in the County of Plotzk and in parts of the County of Rawa Jewish communities had already established themselves, despite the official bans, in the County (or voivodeship) of Czersk, which included Ostroveh, there was not a single Jew to be found except for the few who ran country inns.

The rulers of Mazovia briefly succeeded in maintaining a certain degree of independence and in retaining special laws that applied only in Mazovia. Two compendia of the laws of Mazovia were compiled that were also authorized by the kings of Poland. But in 1578 Stefan Batory, the brave King of Poland, decided once and for all to abolish the autonomy of the duchy of Mazovia, and to implement within its borders all the laws that were applicable across the Kingdom of Poland.

The rulers of the region, especially members of the szlachta, were unsuccessful in opposing the brave, victorious and much lauded king. They unwillingly submitted to all the laws that applied to the status of the monarchy and the royal house, the rights of the officers of the king, and so forth. But they continued to fight for the continued existence of various special laws, a battle which is known in Polish history as Excepta Ducato Mazovia[1]. In relation to these laws, for over 200 years the representatives of the szlachta (privileged families who enjoyed full rights) continued to demand in their sejmikis (regional councils) that the Jews be expelled from all the counties of Mazovia.

While for all practical purposes these laws were now only applied to the residents of the County of Czersk, demands were made to apply them to all the counties of Mazovia, especially to the County of Plotzk. Members of the Catholic clergy, who by and large led the battle against the Jews and who for all practical purposes encouraged all anti-Jewish efforts, organized the members of the szlachta in the districts outside Mazovia to support these requests and demands.

The laws of Mazovia about which these battles raged were more like customs rather than signed and sealed laws. In those legal compendia there were no specific paragraphs that prohibited Jews from living in those places. Moreover, even according to those sources, an edict that had been issued by Boleslaw II, Duke of Mazovia, expelling all the Jews was never implemented. So Jews did in fact live in the counties of Plotzk and Rawa and in other places with no clear or permanent boundaries defining them. But the rulers of Mazovia continued to press for the expulsion of the Jews from all its territories. Even after the Gezerot Tat v'Tach[2] and the Polish-Swedish wars [of 1655-60], when the Polish kingdom was teetering on the brink, the region's representatives stridently demanded that all Jews without exception be expelled from all of Mazovia. This demand was once again forcefully put forth in the regional conference at Drobnin. There was in fact a good chance that these demands would succeed. Only the great efforts of the Council of the Four Lands[3] and the payment of large bribes prevented passage of the edict.

Prohibition and Excommunication for the Jews

As these demands did not cease, the leaders of the Council of the Four Lands saw a need to restrict the movement towards the settlement of more Jews in the Mazovia region. In the year 1660, on the day of the Fast of Gedaliah, the following declaration was read aloud in the synagogue of Tiktin [Tykocin] in the name of all the leaders of Council of the Four Lands: [cited from the Record Book of Tiktin in Yiddish, then translated into Hebrew]

[Page 11]

“Attention members of the Holy Community. We, the officers, heads and leaders hereby aver that it is well known that according to previous rules no Jews are permitted to live in the province of Mazovia. But recent news indicates that some people have established their residences there. As these incidents have passed without any reaction, we were silent and did not respond. However, now that the bitter problems of the Diaspora have increased and the evil ones have re-awakened and are gnashing their teeth at us every day, we reiterate that the rules established by our predecessors were appropriate as stated and that the prohibition remains in place. We hereby proclaim and declare that from this day forward no Jews shall take up residence in the province of Mazovia. Anyone who shall dare to do so against our will should know that the opinion of the wise will not be pleased with him and that he will be deemed a sinner, thereby separating himself from the community of Israel, which will exclude him. And if something should occur to him, or if there should arise some baseless accusation where such attacks are common, we will not expend a single penny or any other effort to come to his aid. He is on his own, since as of this notification due warning has been given that he is responsible for his own actions. And we will further pursue him through Jewish law, using all the means of compulsion available to us as agreed upon by the assembly of officers and nobles of the community, who have agreed to maintain the prohibition against Jews living in the province of Mazovia as per the previous regulations.”

From this sharply worded declaration we learn that the Council of the Four Lands issued a ban on living in the province of Mazovia, and that apparently the target thereof was specifically the County of Czersk, where over the years quite a number of communities had arisen, among them that of Ostrow Mazowiecka.

But it was clear that neither these bans and excommunications, on the one hand, nor the evil laws of the Polish authorities, on the other, prevented Jews from settling in this county, whether as individuals in the villages or as small communities, despite the great anti-Semitism that expressed itself specifically in this area, which was blessed neither with good fortune nor with a vigorous economy.[4]

These threats of the heads of the communities that they would not come to the aid of Jewish settlers in the event that they were falsely accused and that they would not help them at all; the extreme decisions that they would view the Jewish settlers in this area as having excluded themselves from the wider Jewish community, would all indicate that the heads of the Jewish community in Poland at the time were under great pressure from the veteran communities in the counties of Plotzk and Rawa. They felt that they were in serious danger of expulsion by the enemies of the people of Israel thanks to the Jews in the County of Czersk, who were dragging the other [Jewish] residents of Mazovia down along with them.

But Mazovia was not completely off limits, especially to Jews of means. Thus, there arose large and elaborate communities in this area. And only a few years after the threats of excommunication and prohibition the beautiful community of Ostrow Mazowiecka also arose.

The Beginnings of Ostrow Mazowiecka

The efforts of the authorities in Mazovia, and the ceaseless incitement of the Catholic clergy,

[Page 12]

who were consumed with hatred for the Jews, and even the prohibitions and regulations to prevent the settlement of Jews in the County of Czersk, all failed. The rules of prohibition and the special regulations remained on paper only. Jews streamed into this area and set up settlements and communities all over.

The szlachta in Mazovia did not give up on their war against the Jews. But as their rule weakened along with undermining of the status of Polish institutions in general, so too did the rules of exclusion vis-a-vis the Jews. No one spoke of the ban on the settlement of Jews in Mazovia any longer. The most extreme ones among them demanded only maintenance of the exclusion of Jews from certain cities and towns.

Ostrow Mazowiecka was one of those cities. In 1789 a royal court issued a final decision that absolutely prohibited Jews from living in Ostroveh. For more than 70 years until 1862[5] this ruling was technically in force. But in practice it had no effect whatsoever. Jews arrived and settled in this ancient city, and in the towns and areas of settlement nearby, to such extent that, despite the law, the entire area became a lively and active Jewish one. Neither the non-Jewish residents nor the Jews even remembered its official legal status as a district that “prohibits entry to anyone of the Jewish faith”.

Ostroveh was an ancient city. Back in 1410 Boleslaw IV, the Duke of Mazovia, conferred upon Ostroveh the status of a city, granting the rights of urban dwellers to its residents. The non-Mazovian duchess substantially extended the rights of Ostroveh shortly thereafter.

The kings of Poland, who had vigorously suppressed the independent status of Mazovia, nevertheless maintained the special rights granted to the city of Ostroveh. It had its own starosta (district ruler), as well as a rest stop or temporary residence for the king. Six fairs were held every year. And by 1660 the population of the city and its surrounding villages totaled 5,509 souls.

The Polish authorities had attempted over the course of hundreds of years to prevent the admission of Jews to this place. But in the early 1600's, even before the law prohibiting Jews to live there was abolished, Ostrow Mazowiecka already had 2,486 Jews among a total population of 4,119. Thus, there was a Jewish majority in the city proper, while only a few Jews lived in the surrounding villages.

In this period there were already ten functioning communities in the vicinity of Ostrove: in Anarzow [Andrzejewo] 586 Jews (among 1,448 residents), in Brok 1,296 Jews (among 2,657 residents), in Vonseva [Wasewo] 196 Jews (among 516 residents), in Dlugow [Dlugosiodlo] 800 Jews (among 1,249 residents), in Zaremba [Zareby Koscielne] 1,063 Jews (among among 2,401 residents), in Malkinia [Malkinia Gorna] 348 Jews (among 1,439 residents), in Nur 1,212 Jews (among 3,345 residents), in Parzemba [Poremba] 14 Jews (among 615 residents), in Sitzukhi [Suchcice] 88 Jews (among 610 residents), and in Czeziva [Czyzewo] 1,596 Jews (among 3,391 residents).

The fact that Ostrow Mazowiecka was situated at the very heart of central Poland undoubtedly contributed to its development. It was 80 kilometers from Warsaw the capital, 35 kilometers from Lomza, 70 kilometers from Bialystok, and just a bit over ten kilometers from Malkinia, where the main railroad line between Warsaw and St. Petersburg stopped. The main road between Warsaw and Bialystok and to Polish-ruled Upper Lithuania passed through Ostrow Mazowiecka as well.

The area around Ostroveh was not especially blessed with fresh water rivers, as were other, surrounding areas. In the northern part of the district there were no rivers at all. Water had to be drawn from the wells that were commonly found in those areas. Only in the southern part of the district was there flowing water, the Brok River and a few other smaller streams that flowed into the great Bug River in the adjacent region.

The Majority of Ostroveh Residents Were Jews

For many years the Bug River served as an inexpensive and popular means of transportation for the area and contributed greatly to its development. The main Warsaw-St. Petersburg railroad traversed twenty-five kilometers in the Ostroveh area, with two stations, one in Malkinia and one in Czeziva [Czyzewo]. Roads were also paved to Ostrolenka and other communities. The County of Czersk now ceased to be a laggard, thanks in large measure to the hard work

[Page 13]

and initiative of the Jews, whose numbers continued to grow year by year. The Jewish majority in Ostroveh established itself and grew. In 1886 some 7,800 residents lived there, including 5,088 Jews and only 2,712 non-Jews. Ten years later a number of villages were incorporated into Ostroveh and the city had 16,431 residents, of whom 10,471 were Jews and 5,690 non-Jews. In 1921, after the independence of Poland, the population was 13,425, among whom were 6,812 Jews. In 1934, five years before the destruction and disaster, Ostrow Mazowiecka, which had been joined with Komorowo, had over 20,000 inhabitants, among whom were only 8,000 Jews.

Despite the establishment of the communities in Ostrow Mazowiecka and its environs in general, the Jews of the city and its surrounding areas never succeeded in achieving a well established economic status. There never developed any serious industry in the city or its hinterland, except for a few miscellaneous and rather small enterprises. Only a few Jews attained any degree of wealth that would have rendered them to be thought of as people of substantial means, but these were rare instances. Most of the Jews of Ostrow Mazowiecka (known during Russian rule as Ostrow Lomzinski) were poor or semi-poor. They eked out their livings from small scale trade or artisanship, from peddling or portering and the like. Only several tens of merchants operated fixed places of business.

The most important businesses in which some of the local Jews engaged were the trades in grain and in lumber. A number of flour mills in the area made the development of the first of these fields possible, even if these were of modest scale. The forests in the region became the source of income for some Jews in the area, who even built two lumber mills. Lumber merchants from Ostroveh did business with all of the cities in Poland and beyond. Before the development of the railroad in a major way the trees were transported down the rivers on rafts. After that the trains replaced them.

However, the principal trade and source of such limited income of the area's Jews was purely local and internal. Every Monday and Thursday peasants from near and far would stream into the city.

|

|

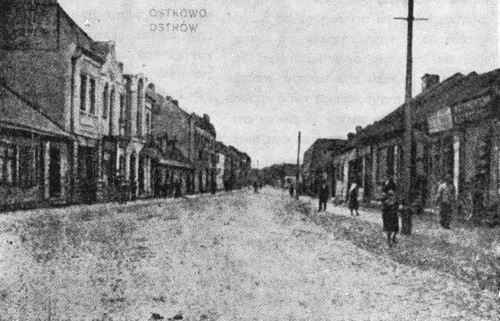

| A street in Ostrow Mazowiecka |

[Page 14]

They sold their produce and bought what they needed at the shops of the local Jews. (This was so until the intensification of the anti-Semitic movement in independent Poland, the establishment of shops by non-Jews and the setting up of co-operatives with government encouragement with the aim of causing Jewish businesses to fail.)

Once a month, on the Monday of the fourth week, a monthly market or fair was held. At that time masses of peasants from hundreds of villages near and far would come, as would hundreds of Jewish peddlers from tens of towns in the area. Several times a year “annual fairs” were held. The basic trade at these fairs was relatively modest, but at times it reached a more or less considerable level. Jews bought grain from the peasants and sold them everything they needed. A peasant would come to town with a cart laden mostly with produce, and would return with a cart even more heavily laden with goods. In an earlier period the peasants would acquire their needs from itinerant peddlers who would travel among the villages fairly often. But over time this practice ended. In the market or at the fair he had a choice of obtaining goods from hundreds of peddlers and merchants, which strengthened his resolve to buy at the fair.

Many roads connected Ostroveh with its surrounding areas both near and far and facilitated access to the city. The main road, which over time became the main highway between Warsaw and St. Petersburg, passed right through Ostroveh. It went from Warsaw by way of Radzymin and Wyszkow to Zambrow, Bialystok, Grodno and Vilna, and from there it reached St. Petersburg, the summer capital of the Russian Empire (today Leningrad[6]).

At the entrance to Ostroveh on the right was a road that led to the town of Brok, which sits alongside the Bug River. On the left of the entrance to the city was a road that led to Goworowo, Rozan, Makow and Pultusk.

In the middle of Ostroveh was a road that led to Malkinia, and on the other side a road that went past Komorowo (three kilometers beyond Ostroveh, which was later integrated into Ostroveh) to Ostrolenka.

The fact that Ostrow Mazowiecka sat at the crossroads of central Poland between its capital, Warsaw, and Polish-ruled Lithuania, was a contributing factor to the settlement of Jews in the city, who came from various places in Poland. This gave a unique character to the inhabitants of the city and its surrounding areas. The particular Yiddish dialect that was used by Jews in central Poland was mixed by residents of Ostroveh and its environs with the Lithuanian Yiddish dialect, thereby creating the unique dialect of the region's residents that distinguished its Jewish inhabitants.

Hassidim and Mitnagdim in the City

As mentioned, the residents of the locale and its environs came to Ostrow Mazowiecka from other areas of Poland and Lithuania. Thus, there were to be found among them both ardent Hassidim and committed Mitnagdim. From the very establishment of the community and its institutions the conflict between Hassidim and Mitnagdim was still alive long after once the sharp battles between Hassidim and Mitnagdim in general had long been forgotten.

When the Mitnagdim sought to dominate the institutions of the community--to select rabbis whom they approved of, or to appoint dayanim [religious judges] or shochtim [ritual slaughterers] who were in accord with their traditions--the Hassidim fought against them, trying to give the city an authentic Hassidic aura. When it came to the selection of rabbis, dayanim or shochtim, and so on, from the Hassidic camp, in the early days of the establishment of the community in Ostrow Mazowiecka the opposing forces were about equally weighted. Sometimes the Hassidim won out, at other times the Mitnagdim. But over time the Hassidim came to dominate the religious establishment of the city, except for those synagogues which had a distinctly Mitnagdic character.

In Ostrow Mazowiecka, as every place else, this conflict between Hassidim and Mitnagdim morphed into a conflict between orthodox and non-orthodox, and among various parties and movements with different political or ideological beliefs. Revolutionary labor movements arose, as did educational institutions with differing or even conflicting goals. The traditional cheder, in which generations of Jews were educated and which became the foundation stone of Jewish education in the Diaspora, lost its dominance to more modern and organized educational institutions, some of which had a religious character, some an anti-religious one.

[Page 15]

The new period of chasing innovation and modernization also changed the traditional way of life that had been accepted for generations in Polish Jewry. Being satisfied with little, aspiring to a modest and restrained life, being happy with the little that the Jew had, and opposing luxuries and a life of ostentation, lost out to a modern life that is lacking in truly joyous occasions, a life centered on the pursuit of luxury and especially the conflict between man and his neighbor to see who could outdo one another with luxuries and in the display of wealth. None of this had ever existed before.

Ostrow Mazowiecka and its surrounding towns, which, like most towns in Poland, Galicia and Lithuania, were not all that big, preserved the beautiful old traditions in this realm until the very day of her destruction. With increasingly greater efforts over the years Jews eked out their limited and modest living with hard work and sweat and were satisfied with their lot. They continued in the beautiful lifestyle of modesty and austerity until their dying day.

From its founding as a community Ostrow Mazowiecka was not prosperous. Of course there were a few wealthy people, but they did not leave their stamp on the community as a whole, nor did they determine its way of life. In fact, poverty conferred a certain charm, an aura of holiness to the life of restraint and modesty of the local residents.

Ostroveh was not a gay city, nor did it ever have such a reputation. But the joys of life were not lacking either. There was no end to the amount of hard work the peddler exerted to earn his few coins. Nor was there any limit to the wearisome toil that the merchant had to exert in his store to support his household modestly, without ostentation. The artisans poured forth rivers of sweat in order to earn a few crusts of bread from their oppressive and difficult manual labor.

The Jews of Ostrow Mazowiecka did not come upon a community that was fully formed. In a relatively short time they established all the institutions of the community. Neither poverty nor lack of resources deterred them from this mission. While a spare penny may not have been available to some individuals, when it came to the general needs of the community nothing was lacking. And as in every Jewish community in Eastern Europe at the time, the homes

|

|

| Warsaw Street in Ostrow Mazowiecka |

[Page 16]

were modest and meager, but the community buildings were large and beautiful.

There were synagogues, houses of study and Hassidic prayer houses, and societies for every need: to provide dowries for poor brides and to visit the sick, to benefit the Jewish soldiers who served in the tsar's army, and for every other charitable purpose. Each of these tasks found a leader who was willing to dedicate his life to that worthy cause without any need for honor or recognition, without reward in any form whatsoever, each of whom worked devotedly in his area or areas.

Only in a later period, when “European modernization” penetrated into public and private life, did each society learn that it had to choose presidents and committees. The first Jews of Ostrow Mazowiecka knew that a mitzvah [religious commandment] is supposed to be carried out heart and soul. It should be done wholeheartedly, with pure, unsullied and honorable intentions for its own sake and not for the sake of any tainted intentions, with modesty and with no personal motivations or desire to stand out or to call undue attention to anything.

The founders of the community of Ostrow Mazowiecka were poor Jews who did not have a penny in their pocket. But they were also wonderful and rare people, who excelled in their values of giving, whose exemplary actions would serve as a model for generations to come. Such Jews, scholars and Hassidim, had no personal needs. The very little that they had, their modest meals, even they seemed extravagant.

Ostroveh did not resemble those older communities where all or most of the members considered themselves family, who had become familiar with one another over the course of the generations and were used to one another. As mentioned, the residents of the town came to Ostroveh from various other counties and regions. Yet, there developed in this community, as in all the older Jewish communities, a feeling of concern and responsibility for one another.

In this period in the Polish Diaspora there was no lack of Jews with charitable values, whose doors were always open, whose hearts were always open to all who those who needed or who asked for help. Moreover, they were on the lookout for any instance of need or trouble. Even though they themselves might have lacked for food, their sole concern was for the poor widow who was caring for orphans

|

|

| Jews in Ostroveh Studying Mishnayot |

[Page 17]

or for the sick or the depressed. Every wanderer found shelter and every starving person succor for his soul.

The Best and Most Honored People of the City

Ostroveh was no different from other communities in maintaining this beautiful heritage. The narrow dwellings of the residents of the city and of the founders of the community in the early years of its existence were always open for assistance. Poverty gave sort of a certain charm to the city and its inhabitants. It did not prevent the residents from doing all they could for one another or for any stranger who knocked on its gates.

As in Israel of old, the face of the city and those who represented it were not the representatives of one class or another, the advocates of one particular ideology or another, or the representatives of parties or movements, but rather the finest people of the city. A Jew who was outstanding in his characteristics and deeds, in his knowledge of the Torah, and so forth, attained the highest rank. Of course, there is no light without a shadow. There were rare instances where the strong ruled and the wealthy advanced themselves thanks to their sharp elbows, but these were few and far between.

The traitor who sidles up to a repressive government was the symbol of degradation. A person who ingratiates himself to people not of his own kind, to the “magistrate,” the non-elected city government that was appointed by the authorities of the Russian tsar, be it Nathan Zelig or Hershel Balbier, who registered dates of birth and of weddings in the official registers, came into direct contact with the world of non-Jews. But the world of the Jews was a world unto itself, a special world.

The small, narrow wooden houses, whose floors squeaked mightily from every step tread upon them, became an integral part of their residents, who practiced a life of austerity and modesty. It was said that thanks to the blessings of a righteous person fire never overcame Ostroveh, that flames never broke out within its gates. Thus, hundreds of ancient houses, of all shades and colors, remained intact.

The residents got so used to their small, modest houses that it was difficult for them to move to larger, more spacious homes, stone houses that were built over the years. These were of greater dimensions containing large and spacious living spaces. But alas they did not bring good fortune to their residents. They introduced a jumbled appearance into Ostrow Mazowiecka, a mixture of old and new that was unlikely to live together in harmony.

Editor's notes:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Ostrów Mazowiecka, Poland

Ostrów Mazowiecka, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Dec 2016 by JH