|

|

|

[Pages 553-554]

by Dr. N. M. Gelber

Translated by Myra Yael Ecker

Edited by Karen Leon

The earliest information about the history of Lwów's Jews, was presented by the Polish writer [Dyonizy] Zubrzycki, in his book Kronika miasta Lwowa [The Chronicles of Lwów],[1] where a large number of details appeared about the private life of Jews, especially about their struggle with the municipality. Zubrzycki relied on records held at the municipal offices in his day. The “Accounts” of the priests [Ignacy] Chodyniecki,[2] and [Tomasz] Józefewicz,[3] dedicate sections to the history of Lwów's Jews. The Polish poet, Józef Bartłomiej Zimorowic, depicted details in his letters about Lwów's Jews, written in an anti-Jewish vein.[4]

The first Jew to concentrate his activity on assembling the historical records of Lwów's Jews, was Gabryel Suchystaw [Gawril Suchestow]. He reproduced the tombstone inscriptions from the cemetery, and made also use of the notebook [pinkas] of the synagogue outside the town. He also collected and printed the legends and tales about Lwów's personalities and dignitaries. Later on, Rabbi Dr. Jecheskiel Caro attempted to present us with a brief history of Lwów's Jews. At the same time, the eminent scholar, Salomon Buber, published his work Anshei Shem [Men of Renown], which includes biographical data on Lwów's Rabbis and community-elders. In addition, Chaim Natan Dembitzer published the first part of Sefer Kelilat Yofi about Lwów's Rabbis.

The first person to write the history of Lwów's Jewry from an historical-scientific aspect, was Dr. Majer Bałaban.

The following are biographical summaries of the authors who depicted the history of Lwów's Jewry:

I. Gabryel Suchystaw [or Gawril Suchestow]

Born at Lwów, Gabryel Suchystaw was the son of Rabbi Hirz [Suchystaw, known as the Black Maggid] the rabbi of the community outside the town. In his youth he studied Torah under great scholars, and became a prodigy. Despite his profound knowledge he was unable to earn a living. He taught, and later became a preacher and a Maggid [religious, itinerant preacher] at the synagogue on Boimów Street. Every Saturday, his supporters assembled there to hear his biblical exegesis. He spoke at length and presented references from our sages of blessed memory, from Midrashim [interpretations] and from scholars' sayings. On weekdays he visited his followers to collect alms for his livelihood. He remained a pauper his entire life and failed to find employment that suited his personality. To his misfortune, he broke his arm and it had to be amputated.

His narration was filled with vivid imagination and rich vernacular language, however, his learning consisted only of Judaic religious studies. He did not know other languages and he did not have a secular education. However, he was always drawn to historical research. He visited cemeteries and reproduced the inscriptions found on the tombstones. He was drawn to the ancient stones and the inscriptions, and to the legends told about the personalities buried there.

The printing cost of his research was funded by Mendel Schütz, a wealthy hospital administrator, who helped Suchystaw publish the reproductions of the tombstone epitaphs. The first printed booklet, Maceweth Kodesz [Mazewet Kodesch; Matzevet Kodesh; Holy Memorial] - a memorial to the Tzadikim, appeared in 1860. It was “a book of remembrance to all the great scholars and holy men who are on the Lord's duty at this ancient cemetery in the town of Lwów. The tombstones' epitaphs and comments shed light on their lives. Also, the history of the great scholar, light of the diaspora, our Rabbi Chacham [Sage] Cwi [Tzvi], may his memory live on. (by the printing press of D. H. Schrenzel).”

Booklet I, included 62 tombstones from (5338) 1577 until (5398) 1638, together with the history of the great scholar, Chacham Tzvi, reproduced from the book Eidut Ya'akov [Jacob's Testimony]. The prayer, “El Maleh Rachamim [God full of Mercy], for the souls of the Rabbis Chanoch and Jozue Reizes [Reices],” from the notebook of the small Synagogue, was also included.

One-hundred-twenty-two epitaphs were reproduced from the tombstones dating from (5340) 1580 until (5479) 1719, in the second booklet which was published in 1862 (printing press of L. Madfes). The Maskil [Enlightened] author, Mendel Mohr, wrote an introduction to Booklet II, in which he expressed “Praise and Glory to the precious book Maceweth Kodesz, a memorial to the righteous.”

[Pages 555-556]

R' Joseph Kohn-Zedek, one of the Galicia's leading Maskilim and Hebrew language news press writers in those days, wrote a poetic introduction on the importance of Suchystaw's endeavour.

This booklet also included Shir Geula [Song of Redemption] by R' Izak HaLevi, together with “A Pleasant Interpretation and A Dreadful Event which occurred at Prague in (5374) 1613/4.”

Suchystaw offered a new booklet in 1864, published by the Lwów printers Kugel and Lewin, which included 57 headstones of rabbis from the period (5320) 1560 – (5477) 1717. This booklet also included the prayer El Maleh Rachamim from the notebook of the Great Synagogue within the town, for the holy people murdered outside the town on 3rd May 1664 (5424), and inside the town, from 3rd May until 13th June 1664.

His third booklet was published in 1865, by Kugel and Lewin. It contained an introduction by Mendel Mohr and Dawid Rappoport, supplemented with an article by Gabriel Falk on the character of Amsterdam's Beit-Chaim [cemetery], and Imrei Noam [Pleasant Sayings] by the renowned Lwów scholar, Jacob [Isak] Jütes.

In 1869, Lwów's Poremba press printed a new booklet, 352 pages long, that contained new tombstone inscriptions as well as those presented in the earlier booklets. Suchystaw's booklets also included a variety of tales and legends, reproductions of writings from the Rabbis' responsa notebooks, and rabbinical articles such as articles by R' Jozue Falk on Interest Law, etc. Suchystaw's books were confusing, unstructured and poorly organised. Suchystaw died in poverty, at Lwów, at the age of seventy.

II. R' Chaim Natan, ben Jekutiel Salman, Dembitzer (1821-1893)

R' Chaim Natan was born at Kraków, where he served as Dayan [rabbinical judge] from 1856. He was influenced by the writings of R' Cwi [Tzwi] Hirsch Chajes [Chajut] and R' Salomon Jehudah Rappoport [Shir], and he dedicated his work to researching Jewish history.

His book Kelilat Yofi, which provided a history of Poland's rabbis, was considered to be an important work. Part I of the book (Kraków, 1888), was dedicated to the history of Lwów's rabbis from the origin of the community until the present.[5]

This book, which forms the basis for Lwów's rabbinic history, also contains comprehensive historical material about the community's inner life. The book is based on primary sources from the rabbinical literature and the communities' notebooks. Even in its great meticulousness, the book lacks a true scientific and historical method of research. A major drawback of his book lies in the confused mass of quotes and facts that are difficult for the reader to wade through.

II [III]. Salomon Buber (1827-1906)

Salomon Buber's investigations were largely influenced by R' Nachman Krochmal and R' Salomon Jehudah Rappoport, as well as by critical publications of manuscripts and prints. His book Anshei Shem (Kraków, 5655; 1894/5), published in a lexicographical fashion, was based on surviving community notebooks, biographical data on 564 scholars, rabbis, heads of Yeshivah and Lwów's community-elders. At the end of his bibliographical book he also entered several reproductions from the notebook. His prime source was Suchystaw's book.

Salomon Buber's book does not constitute a history of Lwów's community.

IV. Dr. Jecheskiel Caro (1844-1915)

Dr. Jecheskiel Caro was the son of Rabbi Józef Chaim (1800-1895), the Rabbi of Włocławek [Leslau], and brother of the renowned historian Prof. Dr. Jacob Caro (1835-1904). In 1891, he was appointed preacher at Lwów's Temple of the Enlightened. His teacher, the historian Prof. Dr. Tzwi [Hirsch; Heinrich] Grätz, demanded that his students research the history of the communities in which they served as rabbis and preachers. Dr. Caro, who had already published the history of the Jewish communities of Erfurt before arriving at Lwów, decided to dedicate his time researching the history of Lwów's Jews, based on the information in Lwów's archives.

Dr. Caro, made use of the publications by Suchystaw and the recordings of Salomon Buber, and was the first [Jewish] researcher who also studied Polish sources and data from Lwów's municipal archives, under the directorship of the Polish historian Dr. Aleksander Czołowski.

The first part of Dr. Caro's book[6] describes the history of Lwów's Jews until 1772. It is largely comprised of German translations of entire sections about Jews, from the Chronicles of Zubrzycki, Józefewicz and Zimorowic. Part II, which focuses on the cultural life, relied on Suchystaw's book, but unlike the original text, Caro arranged the content chronologically, including the lineage of the rabbis, scholars and community-elders. However, Caro's book still lacks historical research, and does not provide the actual process of development of Lwów's Jewish community during the early reign of Poland. Despite the many shortcomings of

[Pages 557-558]

Dr. Caro's book, it is the first history book about Lwów's Jews, on which later historians greatly relied.

V. Prof. Dr. Majer Samuel Bałaban (1877-1941)

Professor Bałaban was the first historian to research the history of Lwów's Jews, using modern historiographical methods. He was not self-taught, but had acquired the scientific method of historical research at university.

As a student of the renowned Polish historian, Prof. Dr. Ludwik Finkel, he had the opportunity to systematically hone his research method.

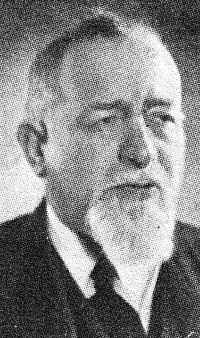

|

|

| Dr. Majer Samuel Bałaban |

Dr. Bałaban, was engaged in the field of Jewish historiography for over 45 years. He was one of its main founders and exponents. In addition to his proficiency as a scientific researcher, he was a significant personality in the Jewish life of Galicia, and later of the whole of Poland. He charmed his friends and acquaintances with his good company, interesting talk, and pleasant personality.

He was also one of the few researchers of Jewish history who succeeded in establishing a particular system of historical research. He had many students who carried on his work and taught Jewish children in Polish schools, about the history of our People. This was accomplished from novel, historiographical perspective and not as a dry “religious study.”

Dr. Majer Samuel Bałaban was a great-grandson, and grandson of a well known Lwów family whose members were community-elders, and leaders, as far back as the 17th century. One of them, Lewko Bałaban, from the middle of the 18th century, did much for Lwów's communities, and was known for his fair judgement. His son, Zusman (Zyskind), led the community for years. He was active in the fight of the Objectors against the Chassidim. He detested the Chassidism and led his family on an anti-Chassidic route. His grandfather, Majer Bałaban, supported Rabbi Jakob Ornstein in his fight against Chassidism.

Prof. Bałaban was born in 1877 and received a traditional, Jewish education at his parents' home. He attended secular schools, and studied Torah in the afternoons with Torah teachers. He began to study law at Lwów University in 1895. Due to his father's financial situation, however, he was obliged to abandon his studies and turn to teaching to earn his living.

He started a life of wandering from job to job. He began as a teacher at the first elementary school established by Baron Hirsch in Gliniany [Hlyniany], one of Galicia's towns known for its Zionist-national organisation and way of life. Later, he continued at Gołogóry [Holohory], a remote small town in eastern Galicia. During all his hardships he never gave up his plans to pursue historiographical research. Immersing himself in it, he realised that his mission was to dedicate himself to historical research. In 1900, after extraordinary tribulations he was transferred to Lwów's primary school named after Tadeusz Czacki, that was in the Jewish Quarter.

A couple of years later he returned to university, but not to the study of law, despite his father's desire to see him as renowned advocate. Instead, he immersed himself in the study of philosophy, and especially of history, and began working in his field of research while he was still a university student.

In 1903, he published the first bibliography written in Polish on the history of the Jews in Poland. He earned the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in 1904, became qualified as a teacher, and was appointed as instructor of history and geography at gymnasiums. After a short time, he was obliged to teach the “Jewish Religion,” because it was deemed unacceptable for a Jew to teach History, at gymnasium level. The Vienna Ministry of Education considered history to be fundamental to patriotic education, and could not, in its opinion, be entrusted to a Jew.

Bałaban's difficult economic conditions left him no other option but to accept the post of “Teacher of Religion,” even though he had already been awarded two premium scientific prizes: [Hipolit] Wawelberg Prize by the University of Lwów, and [Probus] Barczewski by the

[Pages 559-560]

Polish Academy [of Fine Arts] in Kraków, with the recommendation of the leading Polish historian, and Galicia's governor, Prof. Dr. Michał Bobrzyński. The prizes made no difference in Balaban's status. He was a proud Jew and had to manage with the post of “Teacher of Religion.”

From time to time Bałaban travelled abroad for his research, to Berlin, Breslaw [Wrocław], Vienna etc. He spent the First World War, as a refugee in Vienna, and in 1915, he was appointed a military rabbi to the Austrian armed forces. He served in 1915-1918, during the Austrian occupation of Lublin, and did his best to improve the situation of the Jews.

After the war, he settled at Częstochowa [Tschenstochau] where he managed the Jewish gymnasium, and one and a half years later he moved to Warsaw. Ten years after that he directed the Tachkemoni rabbinical seminary, and the Ascola gymnasium. In 1928, he was appointed lecturer of the History of the Jews at Warsaw University, and in 1929, lecturer at the Free [Polish] University (Wolna Wszechnica Polska). In 1936, he was appointed full-time Professor. In 1928, together with Prof. Dr. Mojżész Schorr, and Dr. Markus Braude, he established The Institute of Judaic Sciences [Instytut Nauk Judaistycznych w Warszawie], that during the years 1928-1939 occupied a very important role in the cultural life of Poland's Jewery.

Bałaban's historical undertakings were derived from his Zionist-national conviction. Beginning in the 1820s, the Zionist movement took root amongst secularly educated youth and attracted a large number of supporters, whom it encouraged to cultivate the Jewish culture. Young men from the Torah-study school gave up the world of the Halachah [Jewish law], and put their faith in secular education at the universities of Vienna and Berlin. Zionist movement facilitated the return to Judaism amongst the youth. Students studied Hebrew in secret circles, along with the history and culture of the Jewish people. Apart from the interest in a Jewish national organisation, the romanticism of the Zionist movement also encouraged the Jewish youth to delve deeper into the sources of Judaism and its history.

Galicia's Jewry, a fount of great Judaic scholars, including Rabbi Nachman Krochmal [RaNaK], Salomon Jehudah Rappoport [Shir],

Salomon Buber, Salomon Rubin, Abraham Krochmal, Tzwi Hirsch Chajes, Dr. Moses Ehrenreich, Jozue Heszel Schorr, author of Hechaluc [HeChalutz], Faybus Mieses, Dr. Józef Kobak and others, fell silent for several years. With the waning of the Haskalah [Enlightenment], it could no longer offer the youth a suitable fresh life-plan in this period. Although Galician [Jewish] Enlightenment stayed clear of the spiritual assimilation noted in Germany, it was unable to halt the cultural assimilation that took hold of Galicia's youth.

Then, in the ‘eighties, the national Zionist movement appeared, imbued with many elements of the Haskalah, especially with the teaching of Rabbi Nachman Krochmal, which refreshed the [Jewish] cultural life, rescued the youth from the clutches of assimilation and invested in it a positive life-purpose and faith in its People's future. It played a vital role in the revival of Jewish science in Galicia. It was this period that also influenced Bałaban, who joined the earliest circle of Lwów's Zionist Students, under the spiritual leadership of Dr. Mordechaj [Markus] Ehrenpreis, Dr. [Jozue] Ozjasz Thon and their associates.

Dr. Bałaban's literary work began with journalism. In Przyszłość [Future], the first Zionist Weekly of Galicia, he wrote articles about the problem of Jewish life, under the fictitious name Emet [Truth]. The Weekly's editor, Adolf Stand, one of the first Zionist leaders in Galicia, relates in one of his letters the literary beginnings of Bałaban: “It was in 1897, in the good old days. A young student worked for us, naturally not proofreading the Przyszłość. Once he approached me embarrassed, blushing, and handed me an envelope containing a manuscript. I corrected it and informed its author that in a few days he would proofread his article. That must have been the happiest day of his life. After this article he wrote other articles. I realised that the young man was less suited to journalism that to history. And so I steered him in that direction. The man is the author of comprehensive books on the history of the Jews of Lwów and of Kraków. And were he not a Jew, he would certainly have been a full-time professor by now, at one of the Polish universities.”

Bałaban published his first research on the history of Lwów's Jews in Rocznik Żydowski [Jewish Yearbook] edited by Stand, in 1902-1906. Incidentally, he inherited the “desire to tell stories” from his father, Zusman, who was a renowned Lwów “Objector,” and left his vividly written memoirs in manuscript form, which Bałaban intended to publish.

Before delving into the history of Poland's Jewry, Bałaban tried his hand at the history of the Jews in the days of the Second Temple, and presented his findings in articles on Josephus Flavius and the Hasmoneans. Bałaban abandoned that field of investigation once he started his archaeological research. He and Mojżész Schorr were the first to make use of the significant treasures found at the Bernardine Archives [at the Bernardine Monastery, Sorbona Sq.], and at the municipal archives, in

[Pages 561-562]

search for the Jews' history. Most of the monographs on the history of Poland's Jewry published earlier than theirs, such as those by Samuel Joseph Fünn (Kiriya Ne'emana, Wilno [Vilna; Vilnius]), Arieh Löb Feinstein (Ir Tehilah Brisk-Delita), Szymon Eliezer Friedenstein (Ir Giborim, Grodno [Hrodna]), Salomon Buber (Kiriya Nisgavah, Żółkiew; Anshei Shem, Lwów), Jechiel Matityahu Zunz (Ir HaTzedek, Kraków), Chaim Natan Dembitzer (Kelilat Yofi), were based on informations from Jewish sources. They rarely used non-Jewish documents. Consequently, the historical depiction of the Jewish past, lacked definition, due to its one-sided aspect.

Mojżész Schorr, is notable for conducting researches

|

|

| Dr. Mojżész Schorr |

in the Polish archives, and thus expanding the historical framework. But Schorr abandoned historiography, and dedicated himself to Oriental Studies. Bałaban, who continued Schorr's undertaking, established the research into the history of Poland's Jewry.

His early writings: Żydzi lwowscy na przełomie XVI i XVII wieku [Lwów's Jews at the turn of the 16th and the 17th centuries] (in Polish), for which he received the Wawelberg and the Barczewski prizes; “Herz Homberg i szkoły Józefińskie dla Zydów w Galicyi: (1787-1806)” [“Herz Homberg and the Josephine Schools in Galicia (1787-1806)”] (in Polish, Lwów 1906); Dzieinica żydowska we Lwowie [Lwów's Jewish Quarter] (in Polish, Lwów 1906), already demonstrated his fundamental lines of scientific enquiry that was quite different from the methods of the earlier mentioned Jewish historians, who considered that the history of the Jews was that of the rabbis, the Dayanim [rabbinical judges] the Mohels, cantors etc. Bałaban's method also differed from another type of historians, who applied an apologia or an aspiration for assimilation, to the history of Poland's Jews. This type of historians, such as Hilary Nussbaum, Aleksander Kraushar and Dr. Ludwig Gumplowicz, also failed to provide a true depiction of the Jewish past, in Poland.

Bałaban, pursued entirely different avenues. His primary ambition was to provide an investigative research of the Jews' history in a specific town. In his opinion, it is impossible to write a synthetic history of Poland's Jews, without having detailed knowledge of their lives, throughout the country and from every aspect.

The historian's mission is to delve into all aspects of life comprehend the fundamentals and nuances, in order to provide a full view. It is possible that at times Bałaban provided too many details in his research, but his aim was to assemble these details in order to weave the canvas required for his painting. This he did with endless devotion and artistry. The writing of history was always poised between science and art, and the debate whether historiography is a science, is yet to be resolved. Bałaban's particular historical narration was the key to his greatness. His work was based on actual documents without embellishments or concealment. His creative talent highlighted the past in all the aspects of life. The individuals mentioned in his accounts are no heroes, but human-beings who just stepped out of the crowd and remained part of it. In Bałaban's opinion, it was the Jewish People, their origins, customs and manners but above all the pinnacle, their spiritual culture, that were the deciding factors in history's power-struggles. This clarifies why in his classic monographs on the history of the Jews of Lwów, Kraków and Lublin, Bałaban wrote lengthy descriptions of the lives of common people, their pleasures [simches], weddings, pain, hardships and even conflicts that appeared at times unfair and quite rough.

With the flair of an artist-author, Bałaban depicts the conflicts and intrigues between the community masses and its elders, and even amongst the community-leaders themselves, in all their unsightliness and sordidness which set his concept apart from those of the apologists, who wished only to portray the attractive facet of the Jews. Bałaban did no flinch from recounting the plunder and theft by the elders of the Holy Communities, and by the elders of the Council of Four Lands, who ruthlessly deprived the Jewish people of their rights and who looted as much as they could.

Bałaban's descriptions of the informers are noteworthy. There was Szlome Rabinowicz, part of the privileged Jekeles family from Kraków. There was Feibisch Abramowicz, Kraków's community leader at the end of the 18th century, who took part in the theft and embezzlement perpetrated by the community's tax-lessees. His partner, Herschel Stobnicki, organised an entire gang in 1780-1792, that did not recoil from committing

[Pages 563-564]

detestable deeds. There was the heinous act by Zalman Wolfowicz, Drohobycz's community leader, about whom a Ukrainian folksong was written. Bałaban knew how to engage the reader by skilfully describing the hardships, trembling and horror of the masses. He did so irrespective of the opinions of his detractors, historians and apologists, who were very careful not to divulge any evil events amongst our people, to the Gentiles. To Bałaban's great credit, he did present Jewish history as a separate entity, but introduced it within the framework of general history. He strove to unravel all causal connections between the outside world and the Jews, and he examined how, and how far, the general events affected the lives of Jews.

In his monographs on Lwów, Lublin and Kraków, Bałaban created a model of historical monograph, par excellence, both in the precision of the archaeological research, and in the organisation and process. His books occupy a prime position in Jewish historiography, where they will remain as eternal memorial stones. Not satisfied with regional or local research alone, Bałaban also delved into the problems of communal governance among Poland's Jewry, and into the history of the spiritual-psychological factors. His study on the Sabbateans in Poland, that formed the introduction to his book History of Jewish Mysticism in Poland (which was left in manuscript form, and was lost); his book in Hebrew, LeToldot HaTnua HaFrankit [The History of the Frankist Movement]; and his short but invaluable research written in German: Studien und Quellen zur Geschichte der frankistischen Bewegung in Polen [Studies and Sources on the History of the Frankist Movement in Poland], based on new archival sources and unknown manuscripts, show Sabbateanism and Frankism in Poland, in an entirely new light and reveal unknown, general facts instrumental in the formation of these movements and in their conceptual foundations. His studies of the management and governance of the community were important. He published his research into the community's legislation in 16th- and 17th-century Poland in Jewrejskaja Starina [Jewish Antiquity magazine], as early as 1910-1911.

In 1913, Bałaban published “Die Krakauer Judengemeinde-Ordnung von 1595 und ihre Nachträge” [Jahrbuch der Jüdisch-literarischen Gesellschaft; The Kraków Jewish Community's Regulation of 1595, with its Amendments], which contained his research about the autonomous Jewish institutions in Poland. He studied the community, the Jewish Sejm, and the Council of Four Lands (published in Russian, in Istorja jewrejskog Naroda [History of the Jewish People], Vol. XI, St. Petersburg 1914), and published his small book Polish Jewry's governance Problems, provide focused description of these genetic developments.

Much of his scientific work concernec the history of the cultural life and its leaders, such as R' Samson Wertheimer, Jakób Pollak, Jozue-Jonas Teomim-Fränkel, histories of physicians, pharmacists, printers and pioneers of the Haskalah. His investigations uncovered new material on the history of blood libel in Poland. He unveiled the mysterious world of the Jewish ghetto in Poland, in a sequence of studies. Beyond collecting and processing material, Bałaban largely occupied himself with the questions of historiographical-investigation. An example was his study into conceptual conclusions, which he derived from sources and facts, to resolve the historical question “When and whence did the Jews arrive in Poland” [“Kiedy i skąd przybyli Żydzi do Polski”] (in Polish; Warsaw 1931). Another was the lecture on the evolution of the “Cultural Elements from the river Rhine to the Vistula-Dnieper” [“Elementach kul–turalnych od Renu po Wisłę i Dniepr”] which he delivered at the [7th] International Congress of Historical Sciences in Warsaw, in 1933. He also gave significant lectures at the Fifth Congress of Polish Historians in Warsaw [28.11-4.12] 1930, on the “Tasks and Requirements of the Historiography of the Jews in Poland [Zadania i potrzeby historjografji Żydów w Polsce].” In these lectures, he specifically stressed the national character of Poland's Jewry, which required its own historiography rather than being included in the general Polish historiography, because the concept of national priority constitutes the driving force of historical reality.

In his research “Questions about Jewish historiography in relation to the history of the Jews in Poland,” he touched upon issues which had troubled Jewish historiography as far back as Rabbi Nachman Krochmal and [Isaak Markus] Jost: How to determine the typical periods of our People's history, and, to what extent should our history reflect the historical framework of the nation amongst whom we reside at any particular time.

|

|

| Dr. Markus Braude |

This was not a new dilemma. Bałaban just wanted to inject his own contribution, although he was well aware that reaching a true conclusion was well-nigh impossible. The main questions, in his view, were: should Jewish history follow the generally accepted historiographical periods (Ancient Period; Middle-Ages; Modern Period), and should our history follow the dynamics of every particular period.

[Pages 565-566]

According to Bałaban, the turning point from the Ancient Period to the Middle Ages in our history did not occur in 375, which was the start of nations' migration, but rather in 135 CE, the year of Bar Kochba's revolt, the last attempt to liberate the Jewish State. Consequently, the turn from the Middle Ages to the Modern Period in 1492 CE is not compatible with our history either, since our Middle Ages lasted until after the French Revolution.

The conventional view holds that Balaban was a purely local historian, but his studies lead to a different conclusion.

There is no field in the history of Poland's Jewry which was not advanced by Balaban in some way. He presented a quantity of new material on the history of Jewish art and crafts in his extensive and comprehensive study of “The historical remains of Poland's Jewry,” and rich material on blood libel, in his legally and psychologically important article on “Hugo Grotius und die Ritualmordprozesse in Lublin 1636 [Hugo Grotius and the blood libel trials in Lublin 1636]” (in Festschrift zu Simon Dubnows siebzigstem Geburtstag, Berlin 1930). He extensively researched the history of Galicia's Jews, a topic on which he published several articles, including the book Historja Zydów Galicji i Rzpltej Krakowskiej (1772-1868), Lwów 1912 (History of the Jews in Galicia and in the Kraków republic 1772-1868, Lwów 1912). His last book Historja Lwowskiej synagogi Postępowej, [History of Lwów's synagogue of the progressives], contains a great deal of information on the history of the cultural life of Galicia, and particularly of Lwów, at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

Balaban started his work in the field of bibliography, and his final work was also in this field. He gathered all the material over many years, and hoped to publish it as an extensive bibliographical sequence, arranged in 25 sections, that followed a new system. His students also assisted him in this work. The first volume was published which introduced the sections list. The fate of the manuscript that was not yet published, is unknown.

He told me that he had four monographs: i) The history of blood libel trials in Poland; ii) History of the Council of Four Lands; iii) History of the Jews in Poznań; iv) A volume of historical investigations, that included his articles about “Lwów's Jewish Street,” all of which had been published in Chwila [Zionist daily], and made a great impression at the time. His work over 45 years amounted to 300 books, studies, articles and reviews.

It took a lot for Balaban to attain this position in his own lifetime. From his youth on, he experienced hardships that required him to pave his own way, both materially and socially. Poverty forced him to give up this university studies and take up teaching at Baron Hirsch's primary schools, where he faced a struggle with the assimilated managers. After he eventually returned to Lwów and finished his university education, a new episode of difficulties and conflicts began.

Bałaban refused to succumb to political demands and betray his Zionist views. He never made any concessions and always stressed his Jewish heritage, despite the fact that he could have held a professorship at university if he were willing to declare his affiliation to the Polish nation.

Although he confronted many struggles throughout his life, he never lost his passion for the scientific work to which he tirelessly dedicated his time and effort.

Balaban was also successfully involved in the field of Hebrew education. He prepared teachers to provide Jewish education in Poland for many years. His three-volumed textbook on the history of the Jewish People to the end of the 18th century, is one of the best. As an academic instructor, he was perhaps the first and only among Jewish researchers of the pre-1939 generation, who successfully established an historical system.

Over a hundred scientific works and dissertations were completed at his seminary, with all the archival references appended to each one of them. Those communities under particular study, divulging a variety of subjects on the history of the Jews in Poland between the 16th and the 19th centuries, included, Zamosz [Zamość], Tykocin, Brody, Opatów, Kołomyja, Przemyśl, Łuck [Lutsk], Sandomierz, Lublin. This invaluable material, especially now that most of the Polish archives were destroyed, is kept today in Warsaw. Who knows, perhaps one day it will find its way to Israel.

As a creative historian, Bałaban knew how to guide his students because he understood the essence of history. Besides expanding the material and the summaries of the information in his monographs, he also outlined the morphology of Jewish history in Poland. He highlighted their problems and their roles based on European methodology, and he created a bridge between Jewish historiography and the historical science in Poland. His last works were marked by a desire to end his analytical research, process the rich material he had collected, and turn his hand to the writing of a concise and comprehensive book on the history and lives of Polish Jewry. Fate, however, decided differently.

[Pages 567-568]

The loyal historian of Poland's and Lwów's Jewry, fell victim together with his beloved brethren, to the depiction of whose histories he had dedicated his brilliant writing, his life's vigour.

The Jews of Poland and their chronicler did not part in life nor in death.

Notes:

All notes in square brackets [ ] were made by the translator.

[Pages 569-570]

by Rabbi Dr. David Kahana

Translated by Myra Yael Ecker

Edited by Karen Leon

The origin of the Jewish cemetery in Lwów probably goes back to the beginning of the 14th century and possibly even to the end of the 13th century. To date, it is not known if there was another Jewish cemetery, nor were traces of any other found within the boundaries of the old town and suburbs of Lwów. Presumably, therefore, from the time the Jewish community of Lwów was first established until 1855, that is to say until it closed, the old cemetery near Szpitalna Street served as cemetery for all the Jewish residents of Lwów, with its two communities: the Holy Community within the town, located in the Kraków suburb, formed Lwów's principal and the earliest Jewish community, and the Holy Community outside the town, which was established at a later date.

The cemetery is first mentioned in the municipal records of Lwów in 1414.[1]

These records mention the long established Jewish cemetery that bordered on the field that belonged to a Christian who lived near the Jewish Quarter. As Lwów's official documents first mention the Jewish Street in 1383-84,[2] and as no other cemetery existed in the town proper nor in its vicinity, one can safely assume that at the end of the 13th century there was already a Jewish cemetery in Lwów.

The perimeter of the cemetery, before the Holocaust, formed a square flanked by Rappaporta, Szpitalna, Meiselsa and Kleparowska streets. Flanking Szpitalna Street, was the hospital established by [Maurycy] Lazarus, the Jewish retirement home, and the storerooms of the Jewish burial society [Chevra Kadisha]. Beyond these buildings sprawled a thick forest, its thickets littered with thousands of grey stones, holy headstones leaning against one another with age.

The early days of the cemetery, like that of the community itself, was wretched. In time, with the development of the community within the town and outside it, and as the small communities surrounding the town had no other cemetery, it was a matter of urgency to expand the cemetery.

According to the land purchase register of the municipal archive, eminent members of the town purchased land from their Polish or Ruthenian neighbours, piece by piece, in full payment, until they acquired this plot land.

The cemetery was enclosed in part by a fence, and in part by a wall. A tent stood at the entrance gate, where memorial services were held, where eulogies for the deceased were read out, and from where the funeral processions set off. It is hard to tell whether a synagogue existed there, too, as was generally customary. The synagogue on Szpitalna Street, known as the “Cemetery Shul” was only constructed in the nineteenth century. At the centre of the plot, where the paths crossed, stood the Jewish Pantheon. Here were buried the rabbis, heads of Yeshivas and the leaders of the communities, as well as important personalities and leading rabbis from other communities who died in Lwów. This practice was followed by Lwów's Jews until the old cemetery was closed. Consequently, a concentration of headstones from different periods amassed in one place. Next to the tombstones of R' Nachman ben Izak and his wife Rózà (die goldene Rojze [the Golden Rose]), of Mordechaj [Marek] ben Izak, of the community-elders from the seventeenth century, are found tombstones of community-elders from the nineteenth century. Next to the tombstone of Rabbi Jozue Falk from the seventeenth century, is interred Rabbi Chaim Kohn Rappoport of the eighteenth. The tomb of Rabbi Jakób Ornstein from the nineteenth century is next to the tomb of Rabbi Abraham Kohn. Adjacent to this group are the graves of the holy Reizes [Reices] brothers, who were martyred in 1728. The place was over crowded. In time, the cemetery was practically in the middle of the town.

It is believed that the dead of the Karaite community, which left Lwów in the fifteenth century to establish new communities in eastern Galicia, in Halicz, Dawidów [Dawydiw] and Kukizów [Krasny Ostrow], are also buried in this cemetery. Lwów's elders referred to a narrow strip near the wall which bordered Szpitalna Street, as the burial area of the Karaite sect. Although there were no graves in the area, it was full of broken stones and smashed headstones. I heard the same assumption from Dr. Ananiasz Zajaczkowski, professor at

[Pages 571-572]

Warsaw University, head of Poland's Karaite sect after WWII.

The cemetery was full of trees and bushes, and from afar it looked like a grove. The trees were planted in the sixteenth century. It wasn't until the seventeenth century that their branches and leaves shaded the tombstones and paths, so that the priests [Kohanim] were forbidden from entering the grove for fear of entering a “tent of impurity.” The debate on this issue between Rabbi Jakób Koppel ben R' Aszer Kohn, head of the Rabbinical court, and head of the Yeshivah outside the town (1620-1630), and the great rabbis of his day, is interesting.[3]

As mentioned earlier, the topography indicates that the cemetery was almost at the centre of town, and it was surrounded by houses and gardens that belonged to Christians. Prof. Majer Bałaban, of blessed memory, found after extensive search, that in 1588, 63 Christian houses and courtyards surrounded the Jewish cemetery.

The question is, how did the Jewish funerals arrive at the cemetery through the Christian neighbourhood? The issue was complicated in those days.

From all the data and assessments it is possible to deduce that the funerals arriving from any direction had to pass through two danger spots: via the Dominicans-Square (Plac Dominikański), and via the Kraków-Gate (Brama Krakowska). At times, the funerals met with processions of the clergy, near the Dominicans-Square, while at the Kraków-Gate (at the crossroad of Krakowska and Skarbkowska Streets), a riotous mob and the Christian poor congregated.

I will mention two incidents as examples. On Sunday, 10 August 1631, a large, celebrating crowd blocked the way of a Jewish funeral which passed the Kraków Gate on its way to the cemetery. The mob was led by two students from the religious Metropolitan [Greek Catholic Archbishopric] school, Jan Czech and Stanisław Wiszomorski. They were joined by apprentices and craftsmen who chased the funeral procession, caught up with it near the gate, attacked the escorts, beat them up, robbed them, and destroyed the buildings inside the cemetery. The town police put an end to the outrage. They caught the two leaders while the rest ran away. The second incident took place near the Dominicans' yard, on 26 May 1636. The funeral met with a Christian procession that ended in a fight between the Christians and the Jews. According to the official complaint submitted by the Dominicans, the Jews attending the funeral pushed the priest, who held the sacrament in his hand, and the Christians drew their swords. Many Jews were injured on their heads, many ears were chopped off and many remained disabled for the rest of their lives. These two incidents, which surely were not the only ones, clearly illustrate the pain and torture the Jews suffered on their way to the cemetery to pay their last respects to their relatives.

Among the tombstones in the cemetery, it is worth mentioning,[4] in particular:

I.

1. Tombstone of Jakób Bachor

Jakób Bachor with God 22 Elul

God cried with rage

And Jakob departed bright and witty

Fifteen years old he studied read and iterated

Often called teacher rabbi having made a name for himself

Rabbi Aron Juda Leib delivered eternal majesty and lamentation

Woe my son departed making an impression

May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life,יעקב בחור לו יה כ׳׳ב אלול

בכה אליל אף וחרונה

ויעקב הלך לדרכו חריף ושננא

בן חמש עשרה למד וקרא ושנה

מה׳׳ר הרבו לו כי שם טוב קנה

א׳׳הר׳׳ן נשא עליו נה׳׳י וקינה

הוי בני הודה זיוה והדרה פנה

תנצב׳׳ה

According to the Lwów folklore, the gravestone of Jakób Bachor was the most ancient in the old cemetery.

The stress on the letters ק-ח, points to the date in the sixth millennium [of the Jewish calendar], that is, 1348. The style of the gravestone indicates a measure of Biblical knowledge, which is improbable at that time. There were no Yeshivahs in Poland in the mid-14th century, and the level of Torah knowledge was very poor. Perhaps there was an additional detail or indication which Suchystaw missed, or which in time had fallen off or had been erased from the gravestone.

In contrast, the inscription on the second gravestone from the 14th century is undoubtedly faithful, that of:

2. The woman Miriam-Marisza

Here is interred the honest hearted and modest

M[rs] Miriam Marisza bat our teacher Rabbi Szmuel

Who passed away on Sunday, 2nd Tamuz 5140 [6 June 1380]

May her Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life.

One hundred and forty of the sixth millennium, that is to say 1378. If one compares the date 1378 on Marisza bat Szmuel's tombstone, with 1414, the first mention of the Jewish cemetery near Szpitalna Street, as it appears in the official records of the municipality, one can conclude with certainty that the old cemetery of Lwów was established at the end of the 14th century.

Incidentally, the name Miriam-Marisza calls for deeper investigation. It points to the spoken language, probably affected by a Slav language, which was used by the Jews of Lwów in those days, before the migration of the Ashkenazi Jews.

[Pages 573-574]

3. Tombstones of the brothers Nachman and Mordechaj bnei R' Izak

The Nachmanite family ruled Lwów's community in the second half of the 16th- and in the beginning of the 17th-century.

The family's forebear was Izak ben Nachman, a wholesale merchant, community leader and elder, who built a synagogue at his own expense in (5342) 1582. The researchers refer to it as Nachman's synagogue, but it was popularly known as the Synagogue named after Turei Zahaw (Die Turei Zahaw Schul) or die goldene Rojze [the Golden Rose] Schul.

The inscription on their gravestones read as follows:

i) Tombstone of R' Nachman ben Izak

Lamentation in memory of the here resting jar of manna, the

splendour of time, a faithful shepherd, holy, generous and

merciful man, the great champion, our teacher R' Nachman ben

our teacher R' Izak, the revered local Rabbi, chief, angel, leader

and prime speaker against kings, rulers and ministers. His mouth

and tongue speaks noble wisdom and innocent, honest reason.

Great in the Torah, in his standing, will raise his reputation, his

large charitable giving from his fortune bears witness to his

principled distribution. He is also hospitable in his house. For

all this May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life. Amen.

ii) Tombstone of R' Mordechaj ben Izak

Here is interred the affable Rabbi, our Teacher Rabbi Mordechaj

ben the leading Rabbi, our Teacher Rabbi Izak who turned his

teaching into a regular law. As stuart he also dispensed his

wealth among relatives and strangers. A champion in the Torah,

head and leader of the community and of the Land, he faithfully

handled the public's needs and founded Yeshivot as of old. He

was engaged in the redemption of captives, according to custom

and law, he donated his money to the poor in Eretz Israel. As

stuart he regularly fasted for long periods and he also donated a

building for the hospital and also donated the roof to enlarge the

synagogue that he, his father and his brother had built. His

goodness was boundless, he built a hostel for guests and donated

a great deal of money to brides' doweries. His benevolence and

righteousness is immeasurable. For this May his soul be Bound

in the Bond of Everlasting Life and his spirit and soul abide

under the shadow of the Almighty. May his good deeds stand in

good stead for us and all Jews. Amen.

The version of the inscriptions on the gravestones indicates communal involvement and engagement. The attitude toward Eretz Israel needs a mention. Nachman ben Izak was termed “revered local Rabbi” and it was said of Mordechaj ben Izak that he “sent his coins to the poor in Eretz Israel.” Both of them were “presidents of the Holy Land,” and they transferred the donations to the appropriate destinations. As known, from the early days, the donations from the whole of Poland were sent to the town of Lwów, to the safekeeping of a faithful man who was given the title “President of Eretz Israel,” who then transferred the donations to Eretz Israel.

iii) Rózà bat R' Jakób - the wife of Nachman ben Izak

She was known as die goldene Rojze [the Golden Rose]. She took part in the fight against the confiscation of the synagogue built by the Nachmanowicz family. She was an energetic, enterprising woman. A bouquet of legends was created around this woman.[5] The text on her tombstone reads as follows:

Here is interred an honest, standard-bearing lady Mrs. Rózà

bat Rabbi Jakób. Tuesday – 4 Tishrei (5395) [26 September

1634]. I deeply lament the grave loss of the daughter of Jakób.

The crown fell off his head, his resourcefulness was displaced

and the branches of the pure candelabra broke off. A more

wonderful woman could not be found. Angels and clerics saw

her, rose and bowed.

May her Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life.

The style of the gravestone bears witness to the fact that Rózà, the wife of Nachman ben Izak, died a natural death in 5395 (1635), with no hint of a murder or martyrdom. The absence of the customary phrase “God will avenge her blood,” lays to rest any doubt that these were founded on fiction.

The love and admiration of the masses created these myths about her. It is possible, and according to Dr. Jecheskiel Caro,[6] over time, the masses introduced the name Rózà in place of another woman who was actually martyred, Adel of Drohobych.

And this is the wording of her tombstone:

iv) Adel of Drohobych

On Friday, 27 Elul 5470 [22 September 1710], the holy and pure

lady, Mrs. Adel, daughter of the great head and leader our

Teacher and Rabbi Mojzesz Kikenes, was sentenced consecrated

and gave her soul for all the Jewish People. God will avenge her

blood and for this May her Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life.

Adel daughter of Mojzesz Kikenes was sentenced and martyred in 1710.

v) Tombstone of the holy Reices brothers

And the entire Jewish People will mourn the fire burnt by God.

Like a blade, the flame set out to separate the parts into pieces,

the head and the fat for fragrant scent. The day of judgement is

upon us on that massacre day, the eve of Shavuot [Festival of

Weeks]. The evening shadow darkened our countenances in the

year 1728 as woe betide us. The fire started and consumed the

foundations of the sacred brothers. The Rabbi, the light the great

scholar, our teacher Rabbi Chaim head of Yeshivah of the two

communities, crown and jewel of Israel was brutally killed, burnt

at the stake, and his young brother Pneh

[Pages 575-576]

Josua observed the moon for several years, sat fasting and died

of thirst and bitterness, our teacher, the great scholar, Rabbi

Jozue. The sons of our teacher Izak HaLevy who courageously

sacrificed their souls and were martyred for the sanctity of the

special God. They both departed terribly, burnt to death in the

fire, unwilling to convert. Their souls departed sacred and pure,

and their ashes saved from the fire were interred here and

it was collected and placed like the ashes of Izak in perpetual

memory of the martyrs. For this May their Souls be Bound in

the Bond of Everlasting Life.

Adel of Drohobych and the Reices brothers bear clear witness to the method of persecution of the Spanish Inquisition. The Latin Archbishop of Lwów, who headed the Inquisition's tribunal in the district of Lwów, sentenced to death Adel of Drohobych and the Reices brothers.[7]

II. Rabbis and Heads of Yeshivah

i) Avenging God, come and avenge the spilt blood of your servant,

revenge of our teacher The head of Yeshivah, light of Israel the

Rabbi, the great scholar, holy and pure Menachem ben Rabbi

Izak of blessed memory who sanctified the great and awesome

God and who gave his life for the Jewish community and

suffered a brutal, grave death by the hands of the reckless who

congregated on the holy Shabbath (8 Iyar 5424) 3rd May 1664,

here at Lwów outside the town. May his Soul be Bound in the

Bond of Everlasting Life, and God soon avenge his blood and

may his virtue stand all the Jewish People in good stead.

ii) Woe betide that our teacher light of Israel, head of Yeshivah, the

great scholar [gaon] Eliezer ben our teacher Aszer was taken

for our sins and suffered a brutal and grave death by the reckless

on the holy Shabbath (8 Iyar 5424) 3rd May 1664, here in the

holy community of Lwów outside the town. For teaching Torah

and raised many disciples, May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life, God be his inheritance. May he rest in peace

and God avenge his blood.iii) The crown fell off our head, the pride of our generation, the great

scholar our teacher light of Israel Rabbi Simon ben Rabbi our

teacher Bezalel who suffered a brutal and grave death by the

reckless, on the holy Shabbath (8 Iyar 5424) 3rd May 1664,

here, outside the town of Lwów. For teaching Torah to the

Jewish People, being the head of the rabbinical court and head of

Yeshivah in several important, concealed communities, for this

the Merciful will ensconce him under his wings for eternity and

will bind his soul in the bond of Everlasting Life. God be his

inheritance and soon avenge his spilt blood.iv) Our eyes darkened as, for our sins, our teacher head of

Yeshivah, Light of Israel, the great scholar Rabbi Izak ben

our teacher Rabbi Samuel was taken from us. He sanctified the

special God and was martyred for God's divinity and for our holy

Torah and was killed by the accursed reckless who gathered on

the Sabbath (8 Iyar 5424) 3rd May 1664, here, outside the town

of Lwów. May his soul be bound in the bond of Everlasting

Life, and may God soon avenge his blood.v) Here is interred the great scholar [gaon] head of Yeshivah, may

his light shine, our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Maszka son of our

late rabbi, Rabbi Chaim, who was martyred and forsook his

soul, and underwent a harsh and difficult death on the Sabbath (8

Iyar 5424) 3rd May 1664, outside the town of Lwów. As he

taught Jews the Torah, and for this may his soul be bound in the

bond of Everlasting Life, and may God soon avenge his blood.vi) Here rests the Torah pouch and our precious vessel, the holy and the pure great scholar, our revered teacher Mordechaj ben Rabbi Salomon head of Yeshivah who was martyred, forsaking his soul for the Almighty, he underwent a harsh and difficult death on the Sabbath (8 Iyar 5424) 3rd May 1664, in the holy community of Lwów outside the town. For this, May his soul be bound in the bond of Everlasting Life, and may God soon avenge his blood. Amen.

vii) Woe to us for our loss of our precious, beautiful and glorious

agent. Avenging God, avenge the blood of your servant, the soul

of our teacher and rabbi, the great scholar, our teacher, Rabbi

Aron Jechiel son of our teacher, Rabbi Jozef the blessed

head of Yeshivah and excellent Dayan [religious judge]

who passes honest judgements, young in years but a leader of

wisdom who was murdered by four parts death and his blood

spilt like that of a common bovine. May the ground not hide his

blood. Killed by a gruesome four part death of stoning, burning,

slaying and suffocation on the Sabbath (8 Iyar 5424) 3rd May

1664. For this, the Merciful will eternally shield him under his

wings and preserve his memory as the ashes of Izak or others

murdered for their Jewish faith. May his soul be bound in the

bond of Everlasting Life.viii) Avenging God, come and avenge the spilt blood of your servant

by the good-for-nothings who in rage and anger murdered

the holy and pure great scholar, our splendour and

glory, the great Dayan and head of Rabbinical court, our

teacher Rabbi Judah Leib ben our teacher the priest Rabbi

Szmuel Margulis head of the Rabbinical court in the

community of Przemyslany where he wielded an exalted

presidency and taught the Jewish community Torah, which he

also avidly studied day and night. But alas, he who delved into

the Torah was penalised with a harsh and frightful death and for

this, the Merciful will protect him under his wings for eternity

and bind his soul in the bond in everlasting life. God is his

domain. May he rest in peace and God soon avenge his blood.

His good deed will reflect on all the Jewish People.ix) Sons of Turei Zahaw ([Turei Zahav]; Golden Columns)

Almighty, the most esteemed, avenge the spilt blood of your

servants, the soul of the beloved, affable brothers. The special

one, leader of the group, the ultimate champion, our teacher

and rabbi, Rabbi Mordechaj

[Pages 577-578]

and the second, the ultimate rabbi our pious teacher Rabbi

Salomon, sons of our teacher and rabbi the great Rabbi

Dawid HaLevy who were day and night engrossed in the Torah

(two lines were erased) for that avenging God soon avenge their

blood. May their souls be bound in the bond of Everlasting Lifex) Gravestone of the great Scholar, Cwi [Tzvi] Hirsch Aszkenazi author of Chacham Tzvi.

Under a brilliant moon the splendour of the Torah was plucked,

and its glory dissipated during the season of the first grapes when

a bunch is insignificant. Asceticism and purity have perished, the

mood was stored. Holy light, a once in a generation wonder.

What of a generation that has lost its leader, commander of

angels, man of God in the capital, our master, teacher and rabbi.

The quintessential rabbi the renowned great scholar [gaon] as our

Teacher Cwi Hirsch ben the quintessential Rabbi Jakób who

presented the light of his teaching to the holy community of

Amsterdam and that of Hamburg, and was confirmed as head of

the Rabbinical court and head of Yeshivah of the holy community

of Lwów and of the district. Died on the eve of the second day of

Iyar (5478) [2.5.1718]The reverse of the gravestone reads: The generation was left

orphaned without a comparable in wisdom and pure God-

fearing, reliable biblical teaching. His instruction was

disseminated as a clear ritual law and he wrote responsa books

and innovations of religious tracts and shining articles like

sapphires and jewel, his divine wisdom mesmerised. A

great and strict traditionalist, minister of God's army who in

order to uphold the religious practice, he extricated senses and

artfully commented on death. He stood at the fissure to defend

the rampart of faith and fence it in. May he safely dwell in

heaven and rest in peace. May his soul be bound with his God

and his spirit preserved in heaven and his soul in the Bond of

Everlasting Life.

III. Community Leaders

xi) Here was interred the holy and virtuous, the head and leader of

the Land, our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Szmuel ben our teacher

Rabbi Juda who was sentenced to a severe death and was

murdered by an accursed hand, in Lwów outside the town, on the

Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. May his Soul be

Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and God soon avenge

him.xii-xiii) Here is interred the holy and virtuous, the elder and leader, the

head, the overseer and the governor, our teacher Salomon ben our

teacher Salomon who was sentenced to a harsh death and was

murdered by an accursed hand, in Lwów outside the town, on the

Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664], and God will soon

avenge his blood.

Also, his holy and pure son, Abraham ben our teacher the holy

Salomon who gave his soul and was murdered also in Lwów

outside the town, on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May

1664]. May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life,

and God soon avenge him.xiv) Here is interred the trusting, holy and virtuous head and leader

of the Land, the rabbi, the eminent sage [Chacham], the overseer

our teacher, Rabbi Mordechaj ben the great scholar, our

teacher, Rabbi Jechiel HaKohen who was martyred for the

sanctity of the special and awesome God. For this, may his

Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and may God

soon avenge him. Amen.xv) Here is interred the trusting, holy and virtuous eminent and dear

charity collector of the new synagogue outside the town, our

teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Dawid ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi

Daniel. As he was martyred for the sanctity of the special God,

and was murdered harsh deaths , in Lwów outside the town by

the accursed hands of the reckless, on the Holy Sabbath,

8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this may his Soul be Bound in

the Bond of Everlasting Life, and God soon avenge his blood.

xvi) And Samuel who lovingly and with awe followed God and who

prepared himself to face the holy sacrament and the pure

candelabrum and who focused his prayer, was suddenly punished

with a harsh, severe death. He was murdered during payer by the

accursed hands on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May

1664]. The quintessential Torah scholar, our teacher

and rabbi, Rabbi Samuel ben the teacher and rabbi, Rabbi

Jozef Chajes [Chajut], he was the prayer leader outside the town,

and honoured God with his larynxes. For this, God will soon

avenge his blood and bind his Soul in the Bond of Everlasting

Life, and may he rest in peace.

IV. The Saintly

xvii) Here is interred the exalted worshipper, our learned, holy and

pure teacher and rabbi Juda ben the great scholar [gaon] our

teacher Salomon, of blessed memory, who was martyred and

underwent a harsh death, in Lwów outside the town, by the

accursed reckless on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May

1664]. For this, may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life together with the souls of Abraham Isaac and

Jakob and with the ten royal martyrs and God will avenge his

blood.xviii) Avenging God, avenge the spilt blood of your worshipper, our

teacher the great scholar and rabbi, Rabbi Nachman ben our

teacher Salomon, of blessed memory, who was martyred and

was murdered in Lwów, by the accursed reckless, on the Holy

Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this may his Soul be

Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life.xix) Here is interred our trusting, holy and the virtuous teacher,

Jakob, may he rest in peace, who was martyred in Lwów, for the

sanctity of his People, on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd

May 1664]. For this, may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life, and God avenge his blood.xx) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher, Majer ben our

teacher Menachem Chazan HaLevy for the harsh death and

was martyred for the sanctity of God on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar

5424 [3rd May 1664]. May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life, and God avenge his blood.

[Pages 579-580]

xxi) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher, Izak ben our

teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Jakob, whose blood was spilt like the

blood of a bull, and who was murdered a harsh death, on the

Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this may his

Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and God avenge

his blood.xxii) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher and rabbi, Rabbi

Juda ben our teacher Szmuel who was martyred, murdered in

Lwów, on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664].

May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life,

and God soon avenge his blood.xxiii-xxiv) Here is gathered and interred our holy and virtuous teacher and

rabbi, Rabbi Juda ben our teacher Szmuel who was martyred,

harshly murdered, set on fire like wood, on the Holy Sabbath,

8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. May his Soul be Bound in the Bond

of Everlasting Life, and may God soon avenge his blood.

Also his holy and virtuous brother, our teacher Salomon ben our

teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Szmuel who was martyred, murdered

on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. May his Soul

be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life.xxv) Here is interred and gathered the body of our holy and virtuous

teacher Ozer ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Salomon, who

was martyred and was murdered outside the town of Lwów, by

the accursed reckless, on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May

1664]. For this may God avenge his blood and bind his Soul be

in the Bond of Everlasting Life.xxvi) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher, Shimon ben our

teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Majer, who was martyred, murdered

in Lwów by accursed hands on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424

[3rd May 1664]. May his Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life, and may God soon avenge his blood.xxvii) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher and rabbi, Rabbi

Mozes ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Salomon who was

martyred outside the town of Lwów, murdered a harsh and severe

death for the special and awesome God. For this, may God bind

his Soul in the Bond of Everlasting Life and avenge him.xxviii-xxix) Here is gathered and interred our holy and virtuous teacher and

rabbi, Rabbi Izak ben the teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Jakob,

who was martyred for the great and awesome God, who was

murdered in Lwów by an accursed hand on the Sabbath, 8 Iyar

5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this reason, may his Soul be Bound in

the Bond of Everlasting Life. His holy and virtuous brother, our

teacher Zecharija, ben our teacher Jakob, who was martyred for

the special God, and whose blood was spilt like the blood of a

bull. For this, may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting

Life, and may God soon avenge his blood.xxx) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher Eliezer ben our

teacher Avigdor. For worshiping the great and awesome God,

and being martyred on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May

1664]], may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life,

and God avenge him.xxxi) Here is interred the trusting, judicious, holy and virtuous head

and leader of the Land, the quintessential Chacham,

influential man, our teacher Mordechaj ben our teacher

Jechiel HaKohen, who was martyred for the special and

awesome God. For this may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of

Everlasting Life, and may God soon avenge his blood, Amen.xxxii) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher Eliezer ben our

teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Abraham. In Lwów, outside the

town, he was martyred for God, murdered a harsh and severe

death, on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For

this, may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and

God avenge his blood.xxxiii) Here is interred our holy and virtuous teacher Baruch ben our

teacher Mordechaj, who was martyred. He was murdered

outside the town of Lwów by the hands of the accursed reckless,

on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this, may

his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and God

avenge him.xxxiv) Here is buried and gathered the body of our righteous, holy and

virtuous teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Szulem ben our teacher

and rabbi, Rabbi Nissim, who gave his soul for the sanctity of

God. Full of love and fear, he was murdered by an accursed hand

on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this may

God bind his Soul in the Bond of Everlasting Life, may he rest in

peace and God avenge his blood.xxxv) Here is buried and gathered the body of our righteous, holy and

virtuous teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Izak ben our teacher and

rabbi, Rabbi Jakob who was martyred for the special and

awesome God, and was murdered outside the town of Lwów, on

the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this, may his

Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and may God

avenge him.xxxvi) Here is interred our trusting, holy and virtuous teacher, Azriel

ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Avigdor, who was martyred

for the special God, and was murdered a harsh and severe death,

by the accursed reckless, in Lwów outside the town, on the

Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rdMay 1664]. For this, may his Soul be

Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and may God avenge

him.xxxvii) Here is buried and gathered the body of the righteous, holy and

virtuous great man, our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Shimon ben

our late teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Majer, who was martyred

for God's sanctity, murdered, in Lwów outside the town, by the

hands of the accursed reckless on 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664].

For this, may his Soul be Bound in the Bond of Everlasting Life,

and may God avenge him.xxxviii) Here is interred the holy remains of the holy and virtuous rabbi,

our teacher Eliezer ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Reuben

Hakohn, who was martyred for the sanctity of the special God,

and was sentenced to harsh deaths and his body set alight on the

[Pages 581-582]

Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664]. For this the merciful

will bind his Soul in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and his

memory will ascend with the ashes of Isaac, and like the ten

royal martyrs, may God avenge his blood like and the blood of

his disciples spilt like a fragrant scent, Amen.xxxix) Avenging God, dressed in avenging garments, avenge the spilt

blood of your worshippers, spilt like water. The young and wise

wait for sweets from a larger and more sprawling family. He was

always very astute in his studies, displaying great proficiency, his

heart as wide open as a hall entrance. He devoured the Torah like

a lion and his notable leadership was like that of a seventy-years

old. He mastered the Torah as no student of a hundred years or

more could. Scripture says of someone like him: the sleep of the

worker is sweet, if short, and the satiety of the rich is in the

wealth of the Torah. By an accursed hand, here in Lwów, outside

the town, on the Holy Sabbath, 8 Iyar 5424 [3rd May 1664], our

teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Dawid ben R' Izak Nachmisz was

murdered in his youth, kicked by a snake. For this, may his Soul

be bound in Bond of Everlasting Life, Amen.xl) Regard his origin, the sign marking his cave represents the

cornerstone. How such excellence turned into ashes, he, who

aged fifteen, wrote and read a great deal. The astute and

proficient Mr. Chaim ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi

Baruch, who was murdered by accursed reckless hands and by

those good-for-nothings. For this, the all merciful will bind his

soul in the bond of Everlasting Life, and will avenge his blood.

God is his patrimony and may he rest in peace.

The Martyrs of 10-11 Iyar 5424 [5-6 May 1664]

xli) Our eyes darkened as our dear, youthful light, our teacher, Cwi

[Tzwi] Hirsch ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Abraham

Katz, was snatched from us. Here, in the town of Lwów, on 10

Iyar 5424 [5-6 May 1664], the great scholar [Gaon], champion in

the Torah and Chassidism, in sanctity and purity, in the great

Jewish literature and a foremost Rabbinical judge [Dayan], was

murdered and stabbed a severe death. For this, the all merciful

will shield him under his wings, and bind his soul in the bond of

Everlasting Life. God is his patrimony and will soon avenge his

blood and the blood of the virtuous, may their souls be bound in

the bond of Everlasting Life.xlii) Exhausted, Abraham died prematurely and without trial.

Judgement is in the hand of the avenging God. Protecting and

avenging God, avenge the spilt blood of your disciples, our

champions and our virtuous, the great champion in the Torah and

in the fear of God, an instructor of the Torah who taught many

students. The Dayan and head of Yeshivah, our teacher and

rabbi, Rabbi Abraham ben our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi

Salomon, the great Chassid who poured his troubles and prayers,

body and soul, and his mellifluous voice as that of the Leviates in

the Temple, was martyred by those good-for-nothing who

together murdered and stabbed him. Martyred for the love and

fear of God, and the sanctity of his great name, he was murdered

in the town of Lwów on 11 Iyar 5424 [6 May 1664]. For this,

may his death serve as atonement for the entire Jewish People,

and God avenge his blood, and bind his soul in the bond of

Everlasting Life.

The Martyrs of 13-14 Iyar 5424 [8-9 May 1664]

xliii-xliv) Protective and avenging God, dressed in avenging garb…

Avenging God, avenge the spilt blood of your disciples, blood

spilt like water by a group of good-for-nothing, who murdered

them on 13 Iyar 5424 [8 May 1664], in their homes in their beds.

The champion, pure light, proficient in the Torah, our holy, great

scholar and pride, our teacher Aron ben our teacher Lapidot

who spent all his days studying the Torah, he also taught many

disciples. He was a great and excellent rabbinical judge and

greatly devout, who followed God wholeheartedly and prayed

with his entire being. He extolled the great and awesome God,

and his modest and devout wife, the Holy and pure Mrs. Reisel

bat our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Jakob of blessed memory.

For this, God will soon avenge their blood, may their soul be

bound in the bond of Everlasting Life.xlv-xlvi) Avenging God, avenge the spilt blood of your disciples, and the

blood of the Holy who were martyred for the sanctity of the

special and awesome God. For alas, men of the covenant were

lost, and no one blocks the fissure or protects the boundary.

These two brethren of mine among the Holy, exalted, pure the

devout, steeped in the Torah and sanctity, our teacher and rabbi

Rabbi Izak and our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Eliezer bnei the

champion and great scholar, our teacher, Elijahu used to sit

and study Torah lessons with disciples in an orderly fashion.

They were sharp and refined, but were alas murdered severe

deaths by an accursed hand, on 14 Iyar 5424 [9 May 1664], and

God will soon avenge their blood and bind their souls in the bond

of Everlasting Life. God is their domain, and may they rest in

peace.

The Martyrs of 20 Sivan 5424 [13 June 1664]

xlvii) Lament and howl for the tree of life cut short in its short years.

Like the holy fruit of an edible tree of life, he was heavily

laden with the Torah. He exerted himself in the Torah, like a

one-hundred years old student. A harsh and difficult death was

suddenly inflicted on him. The great rabbi, the quintessential

scholar [Chacham], our teacher and rabbi, Rabbi Chaim ben

the rabbi our teacher, Rabbi Mordechaj, was murdered on 20

Sivan 5424 [13 June 1664]. God will avenge his blood and

bind his Soul in the Bond of Everlasting Life, and may he rest in peace, Amen.xlviii) Our heart ached, our eyes darkened at God's blows of removing

off our heads our crown and splendour, the great scholar, our

teacher, Rabbi Abraham ben the champion great scholar, our

teacher, Rabbi Josef Katz, head of Yeshivah of the Kolomiya

community, who was removed, for our sins, and was murdered

harshly by an accursed hand. He was martyred for the sanctity of

God in his special awesomeness.

[Pages 583-584]

As he taught Torah and raised many disciples, the Merciful will

ensconce him for eternity under his wings and will soon avenge

his blood. May his soul be bound in the bond of Everlasting

Life.

The holy men, within the town, were not mentioned in the book by Gabryel Suchystaw [Gawril Suchestow], apart from the holy man Chaim ben Mordechaj, who was murdered on 20 Sivan 5424 [13 June 1664]. They were probably buried in a separate, unknown area of the cemetery.

The Decorations and Symbols

In the manner of religious art designated to serve as the memory of generations, the tombstones in Lwów's ancient cemetery are noted for their decorative wealth, their diverse ornamentation and their complex forms and clues.

On the whole, they are made of an upright stone with a semicircular or a triangular top. The prevalent stone here is the sandstone (Sandstein). The ornamentation of some tombstones consists largely of their epitaph. Their motives are reminiscent of ancient Prochets [ornamental curtains in front of the holy ark in a synagogue] with two columns on either side. Fauna and flora motifs, or symbols, primarily bedeck the semicircular or triangular portion, but appear also along the borders.

Among the symbols engraved on the tombstones of Lwów's ancient cemetery were these that were common and well-known to the Jews of Poland: Raised hands of a priest - symbol of a Kohen's grave; a washbasin, jag or musical instrument – symbol of a Levite's grave; charity box on the grave of a philanthropist; parchment covered in a goose feather - symbol of a scribe of Jewish religious texts; a lion on the grave of an “Arie, Leib”; a deer on the grave of “Hirsch [Hirsz; Cwi; Tzvi]”; candelabrum [Menorah] or lit candles on the grave of a modest woman; a tree that was cut down - a symbol of a young man whose life cut short; Keter-Torah [crown shaped ornament set on top of a Torah scroll] on the grave of great scholar; an open book engraved with the title of an essay - symbol of a great rabbi and an author; an open Ark with a Keter-Torah above it - symbol of a rabbi or head of Yeshivah.

Besides the aforementioned symbols, a unique heraldic motif is used in Lwów's ancient cemetery. Drawings of fish decorate the tombstones of members of the Kikenes[8] family, referred to as the descendants of the prophet Jonah. A magnificent drawing of two fish is carved into the top, semicircular or triangular portion of the tombstone.

The following are a few examples:

i) Levy ben Izak Kikenes

Angels seized the Holy Ark. The angels conquered the cliffs and

off our heads was removed the crown and splendour, the great

scholar, the eye of the diaspora, our teacher, Rabbi Levy ben

the great scholar, our teacher, Jakób Kikenes, scion of the

prophet Jonah, head of the rabbinical court and head of Yeshivah

at Lwów. Woe betide us for losing a righteous man who

dispensed justice and charity among the Jews, taught them the

Torah and raised many disciples. Woe for this adornment which

will wither in the dust. For this, may his Soul be bound in the

Bond of Everlasting Life.

Died on the first day of Pesach [Passover] 5263 [11.4.1503].