|

|

55°40' 25°22'

Svedasai (Svadushch in Yiddish) lies in northeastern Lithuania, between the

Alausas and Svedasas lakes and surrounded by pine forests, 26 kilometers

northwest of the district administrative center Utyan (Utena).

Svadushch is first mentioned in documents from 1503. Military documents from 1567 mention an estate named Svedasai that belonged to the Radzivil (Radvila in Lithuanian) family. In 1645 it was already a considerable settlement. It was built around a square with houses on all sides. In the center of the great plaza stood the church, and a well. Seven roads radiated from the plaza to nearby villages. The buildings of the estate were situated to the southwest of the town.

From the eighteenth century onward, great markets and two yearly fairs were held in the town. At the end of the eighteenth century the estate was administered by the Morikonis family.

In 1863 Svadushch residents were involved in the rebellion against the Czar's rule. By the end of the nineteenth century the town had grown to contain 64 courtyards, a church and the offices of the county headquarters. The farmers of the county grew mainly flax, that was processed locally.

Until 1795 Svadushch was included in the Polish-Lithuanian Kingdom. According to the third division of Poland in the same year by the three superpowers of those times, Russia, Prussia and Austria, Lithuania was divided between Russia and Prussia. As most of Lithuania, Svadushch became a part of the Russian Empire, first in the Vilna province (Gubernia) and from 1843 in the Kovno Gubernia in the Vilkomir (Ukmerge) district.

In 1904 a great fire destroyed almost the entire town. In 1905 there were uprisings against the Czar's rule. In 1915 during World War I the front line between the invading German army and the defending Russian army stopped for seven weeks at the lakes near the town. Later Svadushch was occupied by the Germans who ruled there till the end of the war and the establishment of the independent Lithuanian state in 1918.

In the eighteenth century an organized Jewish community already functioned in Svadushch. In 1766, the Jewish population was 154 in the town and 75 more in the district. Before World War I many Jews rented their land from the landowners, but subsequently they acquired them and became the owners.

According to the all Russian census of 1897 there were 1,423 residents in Svadushch, 528 of them Jewish (37%).

During World War I, in 1915 many Svadushch Jews moved to Russia and only a fraction remained in the town. After the war, in 1920, most of them returned home.

Relations between the Jews and non-Jews in the town were generally harmonious. Almost all the houses of the Jews who left for Russia were saved intact and not looted. The local priest continued to preach for good relations between the two communities.

During the period of Independent Lithuania (1918-1940)

Following the passage of the Law of Autonomies for Minorities issued by the new Lithuanian government, the Minister for Jewish Affairs, Dr. Menachem (Max) Soloveitshik, ordered elections to community committees Va'adei Kehilah to be held in the summer of 1919. In Svadushch a community committee of five members was elected. This committee functioned until about the end of 1925 when the autonomy was annulled by the Lithuanian government. For several years the committee was active in all aspects of the Jewish life in town.

The first census conducted by the government in 1923 recorded 1,146 residents in the town, 245 of them being Jewish (21%).

The government survey of businesses of 1931 counted nine Jewish shops in Svadushch: three textile shops, one grocery, one leather shop, one restaurant, one bakery, one sewing machines shop an one pharmacy. The remaining businesses were timber and flax merchants, carters, peddlers and fruit growers.

In this period fifteen Jewish artisans worked in Svadushch: five butchers, three tailors, three shoemakers, two metal workers and one baker. There was one customs agent. Of the thirteen telephone subscribers in town, only one was Jewish.

Svadushch Jews were either Hasidim from the Habad movement or Mithnagdim. The Habad men were acknowledged as the erudites in town and they sent their boys to study in Lubavitch. There were two Batei Midrash, one for the Hasidim and one for the Mithnagdim, but they shared one rabbi and one shohet. The rabbi would pray one week with the Hasidim and one week with the Mithnagdim.

Most Svadushch men went to the Beth Midrash after work in order to learn with one of the Torah societies such as Talmud, Mishnah or Ein Ya'akov or to read and study the Tehilim (Psalms).

The wealthier people in the town sought literate husbands for their daughters; thus the Haskalah movement (Jewish enlightenment in the 18th and 19th centuries that was influenced by European intellectuals and sought to offer secular education to European Jews) arrived. One man, Mosheh Ya'akov Farber, sent his daughter to study medicine and after she qualified she worked as a doctor in Svadushch. Her husband was a dentist who also worked there. With the arrival of the Germans in June 1941, both committed suicide.

Before World War I the Jewish children received their education in Hadarim and then in Yeshivoth. Only a few, mainly girls, attended the Russian school.

After the establishment of the Lithuanian state, the community committee looked for a licensed teacher for the planned school. A suitable teacher arrived and wanted to establish the school, but he could not find an appropriate building for it. So the teaching was done in the Ezrath Nashim (the women's section in the synagogue) that was empty on weekdays. However the orthodox group, headed by the rabbi, opposed this and expelled the teacher and the children with some violence and unpleasantness. The children's parents, mostly craftsmen, fought back.

A Hebrew school of the Tarbuth chain was opened with about 60 pupils. Some of its graduates continued their studies in the Hebrew high schools in Utyan and Ponevezh. Besides the school a library and a drama circle operated. Profits from its shows were donated to the Keren Kayemeth Le'Yisrael fund.

Many Svadushch Jews belonged to the Zionist camp. Branches of the General Zionists, the Revisionists and the Zionists Socialists (Z.S.) parties were established, as was a branch of the youth organization Hehalutz HaTsair. Zionist activists included the pharmacist Ya'akov Stolov, in whose house the elections for the 21st Zionist Congress took place, and Shemuel Gafanovitz.

The results of the elections in Svadushch for five Zionist congresses are given in the table below:

| Congress No. | Year | Total Shkalim | Total Votes | Labor Party

|

Revisionists | General Zionists

|

Grosmanists | Mizrakhi | ||||||

| 16 | 1929 | 10 | 8 | – | 1 | – | 7 | – | – | – | ||||

| 17 | 1931 | 35 | 26 | 14 | – | 2 | 8 | – | – | 2 | ||||

| 18 | 1933 | – | 62 | 36 | 9 | 5 | – | 9 | 3 | |||||

| 19 | 1935 | – | 89 | 43 | – | 7 | 1 | 10 | 1 | |||||

| 21 | 1939 | 25 | 24 | 15 | – | 3 | – | N.B.6 | – | |||||

|

|

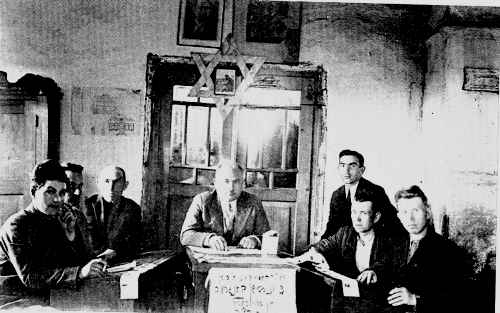

| The elections committee for the nineteenth Zionist congress (1935) |

Many young people went to Kibbutsei Hakhshrah (Training Kibbutsim) and later emigrated to

Eretz-Yisrael. Among the first to do so were Zalman Berzon, Havivah Finkel, Yosef Gafny and

Mosheh Stolov. Others migrated to South Africa.

Rabbis who officiated in Svadushch included:

Shemuel ben Hayim (?-1822)

Yehoshua-Heshl ben Iser

Yehoshua-Mordehai Klatskin (1862-1925)

Aba Shlomovitz

Yosef-Hayim Urinson (1880-?)

Mosheh-Yits'hak Veichik

Yosef Shakhnovitz, the last rabbi of the community, murdered in the Holocaust.

Before World War I the shohet Nathan Fridman taught Gemera in the Beth Midrash.

During World War II

On June 15, 1940 the Red Army entered Lithuania and the state was annexed to the Soviet Union to become a Soviet Republic. Following new regulations, the bigger Jewish businesses were nationalized. All Zionist parties and youth organizations were disbanded and the Hebrew school was closed. Supply of goods decreased and, as a result, prices soared. The middle class, mostly Jewish, bore the brunt of this situation and the standard of living dropped gradually. At that time about 400 Jews (100 families) lived in Svadushch. Soviet rule lasted for one year until June 22, 1941 when the German army invaded Lithuania.

On June 25, German soldiers appeared outside the town and the next day they entered Svadushch and took it over. But even earlier there had been fights between the Soviet militia, in which several Jewish youngsters served, and the Lithuanian nationalists who intended to take control of the town. One of activists was a young Jew, Yits'hak Aras. The Germans placed a reward of 10,000 Marks on his head and his photograph was publicized. But he managed to escape to the Soviet Union, fought in the Red Army against the Germans and was badly wounded. After the war he made his way to Eretz-Yisrael. The Lithuanians hanged his father, the blacksmith, in his shop.

The local Lithuanian activists began to abuse the Jews, in particular the wealthier ones. Two brothers, Jonas and Juozas Rimkus, were excessive in their cruelty. They rounded up the prosperous Jews, imprisoned them in the blacksmith's shop and tortured them into handing over their money and valuables or revealing where they were hidden.

Many Jews were murdered in the town, while others including the rabbi Yosef Shakhnovitz were transported to Rakishok (Rokiskis) under the pretext that they were to work there. On August 10 and 20, 1941 (17th and 27th of Av, 5701) they were murdered together with the Jews of the surrounding areas.

|

|

| The mass grave near Svadushch with the monument |

|

|

| The mass grave with the monument at Velniaduobe |

|

|

|

The monument with the inscription in Lithuanian and Yiddish:

“In this place the Hitlerists and their local helpers on 6-15.8.1941 cruelly murdered 3,207 Jews, children, women, men. Let their memory be sacred.“ |

|

|

|

The monument with the inscription in Yiddish:

“In this place the Nazi murderers and their local helpers in 1941 murdered a group of Svadushch Jews.” |

On the way to the murder site the Lithuanians tried to rape Jewish girls, who

resisted and were shot on the spot. The wounded were thrown in the pits alive.

A young Jew named Sheftl, who had previously been a friend of the murderers,

they saved till last as a “gesture of friendship”. He asked them,

“Why do you want to shoot me? Let me live.” The answer was,

“What would you do all alone in the town?” He tried to escape but his

so-called friends shot him in the back. Two men, David and Leib Pakovitz

managed to hide, but some time later they were caught and murdered.

Near the town several mass graves are marked:

Sources:

Yad Vashem archives, Collection of Lithuanian Jewish Communities, 0-57, testimony of Yits'hak Aras

YIVO, New York, Collection of Lithuanian Jewish Communities, files 1296-1299, 1549

Bakaltchuk-Felin, Melakh (Redactor), Yizkor Book of Rakishok and surroundings (Yiddish), Johannesburg, 1952, pages 356-361

Julius, Rafael, Svedasai (Hebrew), Pinkas HaKehiloth-Lita, Yad Vashem, Jerusalem 1996

Tsait, Shavl #12, 9.5.1924

The above article is an excerpt from “Protecting Our Litvak Heritage” by Josef Rosin. The book contains this article along with many others, plus an extensive description of the Litvak Jewish community in Lithuania that provides an excellent context to understand the above article. Click here to see where to obtain the book.

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of the translation.The reader may wish to refer to the original material for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 22 Sep 2011 by OR