|

|

|

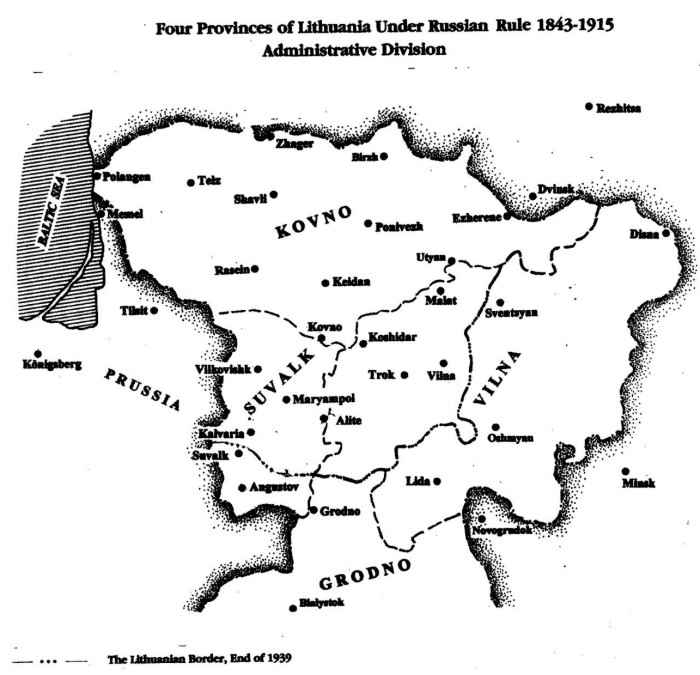

The book I am presenting here contains articles on the history of fifty Jewish communities, about half of them in the Zemaitija region (Akmene, Kursenai, Vidukle etc.) and half in the Aukstaitija region (Krekenava, Moletai, Miroslavs etc.)(see map). Most of the towns had a small Jewish population that during the years became smaller and smaller because many of it emigrated to South Africa, America and Eretz–Yisrael.

I wrote these articles in English and half of them were edited by Sarah and Mordehai Kopfstein, Haifa, Israel, by Fania Hilelson–Jivotovsky, Montreal, Canada, by Sue Levy of Perth, Australia and by Joel Alpert, Boston, USA.

The pictures included in the articles come from various sources: the names of the people who allowed me to use their pictures are printed beneath the pictures. Other sources are the four volumes of Yahaduth Lita published by “The Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel”, Tel–Aviv, and the Archives of the Association and Yahaduth Lita by way of “Mossad HaRav Kook”, Jerusalem. Pictures of the massacre sites and the monuments erected on them were taken mostly from The Book of Sorrow, Vilnius 1997.

Many thanks to my relative and friend Joel Alpert for initiating, compiling, editing and publishing this book.

To my good friend Professor Dov Levin for his encouragement and advice that thanks to him I came write on the subject of commemoration of the Lithuanian Jewish communities.

To my friends Sarah and Mordehai Kopfstein who edited my poor English in half of the articles.

To my cousin Fania Hilelson–Jivotovsky for editing the English in the other half of my articles.

To Peninah, my beloved wife for more than sixty years, for her wise and sensitive remarks.

To Sue Levy for her final editing and proof reading the manuscript of all my articles.

To the “Friends of the Yurburg Jewish Cemetery, Inc.” for their willingness to publish this book.

Josef Rosin has documented the history of a total of 52 Litvak towns in his two volumes of Preserving Our Litvak Heritage, Volumes I and II. Because these two books were so well received, he has decided to continue his documentation of the history of another 50 Litvak towns in this current volume, Protecting Our Litvak Heritage. The editor urges the reader to first read the Introduction in order to fully appreciate and understand the context of the history of each town. The Introduction was written by the eminent scholar of Lithuanian Jewish History, Professor Dov Levin, retired chair of the Department of Oral History at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem.

Both Dr. Dov Levin and the author, Josef Rosin, are natives of Lithuania, raised in that Jewish community and therefore entitled to be called “Litvaks,” a title they both proudly wear. Levin grew up in Kovno and Rosin in Kibart, each living in their hometowns until the start of World War II. They met in the Kovno Ghetto where they were active in the anti–Nazi underground and later in the forests of Lithuania as partisan fighters against the German and Lithuanian Nazis. Both men, now retired, have devoted many years to collecting and assembling information on Litvak history.

In 1996 Yad VaShem published their work, Pinkas Hakehilot Lita in Hebrew (Encyclopedia of the Jewish Communities in Lithuania); it is a monumental work of more than 750 pages detailing the specific history of over 500 Litvak towns. Professor Levin was the editor and Josef Rosin, who wrote about 80% of the entries, was the assistant editor. Unfortunately, this significant work is not accessible to the English reading public because it is written in Hebrew. This current book by Josef Rosin provides an account of 50 of those Litvak communities, in even more detail than was presented in Pinkas Hakehilot Lita, as the author is now able to elaborate and offer details that could not be included due to space limitations. In addition, Rosin has mined the memories and photograph albums of many former residents of these towns now living in Israel and elsewhere, to compile an even more comprehensive picture of these communities. It is truly fortuitous that he accomplished this task in good time, because today, in 2009, those survivors who were young adults in 1941 are now well past their 80th birthday. As we discovered, the younger generations are finally starting to search for their history that existed in their Litvak past, and so we are all extremely fortunate to be able to benefit from the thorough research on which this book is based.

It is my distinct honor and pleasure to have been able to work with Josef Rosin and Professor Dov Levin and thus bring this book to the English reading public.

by Professor Dov Levin, The Hebrew University, Jerusalem

On the eve of the Shoah the Jewish population of Lithuania, including the Vilna region and the refugees from Poland, numbered approximately a quarter of a million souls. Although this represented only around 0.9% of world Jewry during the twenty years of independent Lithuania, it was long recognized as a specific religious–cultural unit as compared to the neighboring Jewish centers of Poland, Belarus and Ukraine. Lithuanian Jews were distinguished by their intellectual and rational attitudes. For good reason the Lithuanian Jews were not only nicknamed Litvak, but also Tseilem Kop (“Cross Head”), suggesting that the Lithuanian Jew would be ready to strike out vertically and horizontally (in the form of a cross, G–d forbid) in order to achieve his goal, or alternatively to cross–check his findings in order to reach absolute truth.

These attributes and others not only had implications in daily life, but also resulted in various phenomena, currents and systems in the socio–cultural strata, for example the reservation of the majority of Lithuanian Jews to the concepts of “False Messiahs” and their opposition to Hasiduth (Chassidism). Their diligence was exemplary in studying the Torah in the Synagogues (Batei Midrash), the Yeshivoth Ketanoth (Junior Yeshivoth) and especially in the Great Yeshivoth. Jewish Lithuania was famous for the great Yeshivoth of Slabodka (Vilijampole), Telzh (Telsiai), Ponivezh (Panevezys) and Kelm (Kelme) where hundreds of foreign students also studied. The Salant community was also well known, because it was from here that the Musar (Ethics) movement began and spread through Rabbi Yisrael Salanter. The Musar principles were based on the use of intellectual activity and knowledge to correct and improve the behavior of the individual. Lithuanian Jewry was also known for fostering the Hibath Zion movement and later for practically adopting the Zionist idea, while exhibiting an almost simultaneous openness to the challenge of the Haskalah (the Enlightenment Movement), whether it be in Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian or German.

The city of Vilna (often referred to as the “Jerusalem of Lithuania”) not only became a worldwide center of Jewish religion but was also the abode of such famous persons as Rabbi Eliyahu (the Vilna Gaon), Rabbi Hayim–Ozer Grodzensky and many others; moreover it was the cradle of the religious Zionist movement (Mizrahi) on the one hand and of the socialist workers movement (Bund) on the other. In due course the Institution of Yiddish Culture (YIVO), now established in New York, was born in this city.

Historically it seems that these impressive attributes and achievements, as well as the special character of Lithuanian Jewry within the Jewish world, developed alongside prolonged struggles for their economic and civil rights among their ethnic Lithuanian neighbors, and this in spite of frequent changes of rulers.

[Page iv]

The first settlement of Jews in the Great Lithuanian Duchy, also named Magnus Ducatus Lithuaniae, began in the fourteenth century by invitation of the Grand Dukes Gediminas and Vytautas (Witold). In 1388, one year after the Christian–Catholic religion was introduced throughout Lithuania, the Jews were also granted a preferred civil status and incomparable bills of rights in many different spheres, such as protecting their bodies and property; freedom to maintain their religious rituals; significant alleviation in the field of commerce and money lending, in relation to Christians. There was also a particular regulation protecting Jews against blood libels. But in 1495, only three years after the expulsion of Spanish Jewry, Grand Duke Alexander expelled all Jews, then numbering more than 6,000, from Lithuania and confiscated their property. Eight years later, when he was elected King of Poland according to the joint rule of these two countries, he allowed Lithuanian Jews to return to their homes and gave them back some of their property. Most of the privileges granted by Vytautas were left intact: for a long period after this event these privileges were of some importance in preserving the legal, civil and economic status of the Jews.

This situation often caused envy among the Christian townspeople, mostly Germans, who were organized in merchant and artisan unions (cechy) and who for a long time had enjoyed the Magdeburg Rights according to the precedent granted to merchants in the town of Magdeburg in Germany; they now perceived the Jews as competitors who had to be fought. For example, they managed to have an edict proclaimed (De non tolerandis Judaeis) forbidding Jews to settle in Vilna, the capital of the duchy, and to trade there. In time this interdict lost its significance. However, insults to Jews by urban Christians, including students at theological seminars in this town and others, continued for centuries.

This was not the same problem that confronted the Jewish population in the north–western region of the Lithuanian Duchy known as Zemaitija or Samogitia (the Jews called it Zamut). In contrast to the eastern region, Aukstaitija, and the south–eastern parts of the duchy, most of this region was settled by ethnic Lithuanian tribes who, in contrast to most of their brethren, had accepted the Christian–Catholic religion relatively late (1413) and, because of their religious background, had not yet been stricken with Judophobia.

The first Jewish settlers in Zamut earned their living by customs and tax collection. A further wave of Jews settled in this region following the expulsion of Jews from Vilna (1527) and Memel (1567). At this time there were already Jewish settlements in Zamut – in Alsiad (Alsedziai), Utyan (Utena), Birzh (Birzai), Zhager (Zagare), Yurburg (Yurbarkas), Palongen

[Page v]

(Palanga), Plungyan (Plunge), Pokroy (Pakruojis), Keidan (Kedainiai), Kelm (Kelme), Shadeve (Seduva)* and other towns.

A considerable improvement in the condition of the Jewish population and in the relationship between Jews and the entire population occurred during the period of the unification of the Great Lithuanian Dukedom with Poland within the framework of the Polish Republic Rzeczpospolita (1569–1795).

Then and for many decades after, feudalism reigned in Lithuania. Most of the population continued to make their living from agriculture as before and from breeding cattle and poultry, from fishing in the rivers and lakes and from harvesting trees. A few, mainly Jews, were peddlers, while even fewer Jews dealt with the import and export of agricultural products. Very few Jews, generally those close to the establishment, were granted the privilege of leasing the collection of levies. With the improvement of roads and sailing routes on the rivers, most of which flowed into the Baltic Sea, there was a gradual increase in commercial activity, especially the export of timber, flax, grains, poultry, cattle and dairy products. As a result taverns and storehouses were established near the crossroads and at river ports. These small settlements developed into villages and towns where many Jewish artisans and merchants settled. Until the eighteenth century in the area of ethnic Lithuania, recognition as a town was granted to 83 settlements and rights to commercial trade to 87 settlements. In fact there was no significant difference in rights between a small (shtetl) and a big town.

An additional factor for Jews becoming firmly established in the economic sphere was the significant growth in the number of Jews employed by nobles and estate owners to manage their estates, and also in the leasing of barrooms and taverns in rural areas. As a result, the Jewish bartender or manager was exposed to the hostility of the rural population, which regarded him as an agent of the noblemen who wished to exploit them.

Although most ethnic Lithuanians were already Christians, the belief in devils and ghosts had not yet disappeared and now the Jew replaced these evil symbols. It was not difficult for the Lithuanians to believe in the veracity of the blood libels, a phenomenon that continued to exist until recently.

Despite this, Western Lithuania, and in particular the Zamut region, became a relatively safe haven for thousands of Jewish refugees who survived the Period of Tribulation (1648–1667) that started with the mutiny of the Cossacks headed by Bogdan Khmielnitsky, and ended with the occupation of Vilna by the Russian army. At the same time, the Black Plague ravaged the population of the region.

The Va'ad Medinath Lita (The Lithuanian Jewish Council) played an important role in maintaining good relations between the general population and the Jews, as well as among the Jews themselves. This Va'ad was a quasi–

[Page vi]

autonomic authority of the union of Jewish communities in the Polish Republic Rzeczpospolita. During the 138 years from 1623 to 1761, this authority effectively and honorably represented the day–to–day interests of about 160,000 Jews in the Lithuanian Dukedom vis–a–vis the rulers and also managed to protect their physical safety and dignity against hostile elements in the Christian population. After the Va'ad was organized, the communities of the Ethnic Lithuania region were included in an administrative unit called Galil Zamut. Later this was renamed Medinath Zamut which included several sub–units in Birzh, (Birzai), Vizhun (Vyzuonos), Plungyan (Plunge) and elsewhere.

Far–reaching changes in the legal and civil status of the Jews occurred during the third division of Poland in 1795; then, most of Lithuania was annexed to Russia and became known as The North–Western Zone, thereby becoming an integral part of the Russian empire. In addition to the Provinces (Guberniae), Vilna in the northeast and Grodno in the south, the provinces of Kovno in the northwest and Suwalk in the southwest were also added. These two included most of the 50 towns presented in this book. This arrangement continued more or less until World War I. (see map taken from The Litvaks).

|

[Page vii]

At the end of the eighteenth century there were several areas in this region where half of the population was Jewish, while in a few the Jews enjoyed a decisive majority. In urban settlements, Jews usually tended to concentrate in a defined area, a Jewish quarter, sometimes called “The Jews' Street.” Jews who were scattered or lived outside this area were strongly linked to and remained in close contact with those living within the Jewish quarter.

As in other areas in western Russia at this time, this region was also proclaimed as belonging to the Tehum HaMoshav HaYehudi (The Jewish Pale of Settlement), where many restrictive edicts and harsh limitations were imposed on the Jewish population, resulting in great hardship and which continued almost until World War I.

At the same time the government was troubled by the isolation of the Jews and tried to deal with this problem in different, sometimes contradictory ways. Thus in 1804 Jews were forbidden to live in the villages and to sell alcohol to peasants, but they were allowed to live as peasants on land allocated to them by the government. Schools were opened for Jews, and in Vilna, a Beth Midrash (Seminary) for Rabbis was permitted. In fact these institutions served as centers for the development of a stratum of learned men who spoke Russian, which gave them entry into the lower echelons of the social and academic establishments. Most Jews, whose main living was based on contact with peasants and the poor and who lived in the villages and in small towns, managed to survive with a minimal knowledge of the Polish and Lithuanian languages. However, among the narrow layer of Lithuanian intelligentsia, still loyal to a great extent to Polish culture and statehood, there were accusations that these Jews were, in fact, causing the spread of Russian culture on behalf of the ruling class. As a result the Jews found themselves “between the hammer and the anvil” in times of war, as during the invasion of Lithuania by Napoleon in 1812. Some of them, favorably impressed by their contacts with French officers, supported the provisional authority established by the French army and even helped to provide information. But the majority remained patriotic to mother Russia. The Jews were thrown into even more critical situations during the Polish uprisings against Russian rule in 1831 and in 1863: on the one hand they were suspected of sympathy with the rulers and some of them were murdered, whereas on the other hand the Cossacks, who had been sent by the rulers against the Poles, abused the Jews after expelling the rebels.

During the 1905 Russian revolution, progressive circles among Lithuanian Jews expressed their support for the Lithuanians, requesting national autonomy in ethnic Lithuanian regions; i.e. in most of the areas of the Vilna and Kovno Guberniae and, in particular, in the Neman (Nemunas) and Vilija (Neris) river basins.

In view of the elections to the all–Russian parliament (Duma) which took place in the years 1906–1917, preliminary agreements were arranged for

[Page viii]

collaboration between Jews and Lithuanians: as a result three Jewish delegates were elected from the Kovno and Vilna Guberniae. At approximately the same time the local branch of the social democratic party in Lithuania published a proclamation in Lithuanian denouncing pogroms against Jews in these Provinces.

From the start of World War I the Russian army organized attacks on Jews in several towns in Lithuania, including Kuziai, on the pretext that they supplied information to the German army. Despite this libel being strongly refuted by a committee on behalf of the Duma, the military authorities did not retract their accusation. Furthermore, in the summer of 1915, before their retreat from the Kovno Gubernia when under pressure by the German army, they exiled 120,000 Jewish citizens into remote Russia.

The German military administration (Oberost) imposed strict adherence to orders on Jews as well as on other residents, but their relationship to Jews was correct and they even made allowances for Jewish cultural requirements.

This attitude was prompted by the presence of several Jewish officers in the German army. Also the identity cards issued to Jews were printed in German and Yiddish. For political reasons the Germans did not allow the establishment of an autonomous framework for Jews, despite the intercession of noted German Jews. A deputation of prominent local Jews, including the chairman of the Vilna community, Dr. Ya'akov Vigodsky, Rabbi Yisrael–Nisan Kark from Kovno and others, represented Jewish interests. Some of them advocated collaboration with Lithuanian delegates regarding the establishment of an independent Lithuania.

Considerably closer relations between Lithuanian Jewry and Lithuanians at the political level could be seen at the end of World War I when Lithuania was proclaimed an independent state. Being interested in acquiring the support of world Jewry, the Lithuanian government granted a broad cultural autonomy to the Jewish minority. Despite the massive participation of Jews in the independence war of Lithuania and their empathy in the struggle against the seizure of the Vilna region by the Polish army, many Jews were nevertheless wounded in pogroms by Lithuanian soldiers in Ponevezh (Panevezys), Vilkomir (Ukmerge), Kovarsk (Kavarskas) and other places. Frequent organized offensives against Jews, such as smearing tar on signs written in Yiddish on shops and on the premises of liberal professionals, were carried out in the temporary capital of Kovno (Kaunas) and in other towns.

In the short period 1920–1925, which can be called the Golden Era of Lithuanian Jewry and the peak of its autonomous status, public Jewish issues were managed by local community committees: these were supported and guided in their daily functions by such central institutions in Kovno as the Jewish National Council, the highest institution of the autonomy, and the Ministry for Jewish Affairs.

|

[Page x]

|

|

|

| Stamp of the Minister for Jewish affairs | Stamp of the National Council of Lithuania's Jews |

The education system in Hebrew and Yiddish, serving about 90% of the Jewish children and the network of popular banks (Folksbank) in 85 settlements, were some of the many achievements of the autonomy period. In most towns, branches of Zionist parties and Zionist youth organizations were active.

Between the two world wars a considerable number of Jews emigrated to Eretz–Yisrael. Hayim–Nakhman Bialik, when visiting Lithuania and hearing Hebrew spoken in the streets, was so impressed that he called Lithuania the Eretz–Yisrael of the Diaspora.

In contrast to the Zionists, the radical religious camp (Agudath Yisrael) and the Yiddishist camp (Folkists, Bundists and Communists) were numerically smaller. Although Hebrew was spoken in educational institutions, in youth organizations and also in a number of houses, the daily language was Yiddish, which was also the language of the six daily newspapers and other publications.

According to the census of 1923, the 156,000 Jews (7.6% of the entire population of Lithuania) comprised the largest minority in the state. The Lithuanian majority numbered 1,701,000 persons (84%). Most Lithuanians were peasants. More than half of the Jews dealt in commerce, crafts and industry and the remainder worked in transportation, liberal professions and agriculture. Two–thirds of the Jews lived in the temporary capital city of Kovno (Vilna and a region around it had been annexed to Poland during this period after World War I) and in cities such as Ponevezh, Shavli (Siauliai) and Vilkomir Ukmerge), while the rest could be found in 33 smaller cities and in 246 smaller towns and rural villages.

[Page xi]

|

|

Front row: Zalman Traub, Dov Aloni Second row: Josef Margolin, Aizik Brudni, ––, Dr. Y.L. Barukh, Shoshanah Alperin, Dr. M. Shvabe, Dr. Josef Berger, Efraim–Nahum Prakhyahu (Prokhovnik) Back row: Avraham Kisin, A. Zabarsky, L. Shapira, Mosheh Cohen, Dr. Aharon Berman, Nathan Goren (Grinblat), Y. Lobman– Haviv, Shepshelevitz |

|

|

From left: Agr. Kelzon (speaking), Dr. Grigori Volf, Leib Garfinkel, Gedalyahu Halperin, Adv. H. Landoi, Fain, ––, Katz |

[Page xii]

In spite of the high degree of loyalty, which Jews showed to Lithuania and their willingness to fulfil their civil obligations to the state, by the end of the 1930s a considerable sector of the Lithuanian public and authorities decided to restrict the economic livelihood of the Jews. A prominent role in a defamation and incitement campaign on this subject was carried out in cities and towns by members of the association of Lithuanian merchants and artisans, Verslininkai. In their journal Verslas they even advocated the prohibition of the employment of Lithuanian women by Jews.

At the same time the number of blood libel incidents, the so–called use of blood of Christian children for baking matzoth, increased. Assaults on Jews increased, on students in Kovno University, and also on people in the streets. Given that specific malicious incidents, such as shattering windows in synagogues and setting fire to wooden Jewish houses, were carried out in several villages simultaneously, one can only conclude that they were organized countrywide. It eventually became clear that some nationalist circles, which favored these actions, had close contacts with various groups in neighboring Nazi Germany, in spite of the fact that at about the same time (March 1939) Germany annexed the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda (Memel), through which numerous Jewish residents narrowly escaped.

This situation, as well as economic depression during this period, which affected the Jewish sector in particular, strengthened left wing political circles among the Jews. Due to international tension and the prospect of war, emigration to America, South Africa and Eretz–Yisrael was restricted.

With the return of the Vilna region to Lithuania at the beginning of World War II (October 10th, 1939), the Jewish population, including war refugees from Poland, increased to 250,000. Despite the difficult situation, Lithuanian Jews came to the assistance of the Polish refugees and warmly welcomed the return of Vilna Jews, with whom contact was renewed after 19 years of separation. This stopped to a great extent on June 15th, 1940 when all Lithuania fell to the Red Army and Soviet–Communist rule was implemented, with all that this implied. Despite the misgivings of many Jews, mainly business owners and those from the Zionist sector, the new regime was accepted positively, particularly when the alternative was that Nazi Germany could have taken over instead.

Despite Soviet rule in Lithuania lasting for only one year, from June 1940 until June 1941, the Jews experienced severe changes to their social and economic status. With Sovietization they were adversely affected by the nationalization of the commercial (83%) and industrial (57%) sectors; by the elimination of the Hebrew education system and the religious institutions, the pride of Lithuanian Jewry; by reduction of the Yiddish press and the closing of all public and political organizations except those connected to the Communist party. A section of Jewish youth, particularly former members of Zionist youth organizations and Hebrew educational institutions, organized

[Page xiii]

secret underground circles, where they maintained intellectual and social activities in Hebrew in a national spirit.

During that year the Soviet government imprisoned several Jewish leaders, local Zionist activists and merchants. All were exiled to Siberia and to other remote areas in the Soviet Union. Others who were destined for the same fate, but had meanwhile been overlooked for some reason, changed their addresses. During this period about 7,000 Jews, including refugees from central Europe and Poland (among them Menahem Begin, the future Prime Minister of Israel) were detained and exiled.

Even though Soviet rule caused obvious suffering to the Jewish population, the Lithuanians blamed the Jews for the loss of their independence, calling for revenge. Meanwhile the Lithuanian national underground (L.A.F. – the Lithuanian Activist Front) which had been established in Berlin on November 17th, 1940, strengthened its secret contacts with Nazi Germany and incited Jews, preparing for an uprising against Soviet rule in expectation of an invasion by the German army.

And indeed, during the first days of war between Germany and the Soviet Union in June 1941, many Jews were cruelly murdered by inhumane Lithuanians. Only a small number managed to escape to the Soviet Union, where some fought against the Nazi German army in the Lithuanian 16th Division of the Red Army.

Since the German army managed to overrun Lithuania in a few days, the majority of Lithuanian Jews remained under Nazi occupation, while the hostile Lithuanian population stepped up their bloody pogroms, raping and robbing their Jewish neighbors.

Very often these terrible events occurred long before the soldiers of the German army arrived at the settlements where Jews had lived for generations. Thousands of Jews all over Lithuania were imprisoned in jails and in other locations which would later serve as mass murder sites, following a precise German plan which was executed with great enthusiasm by the Lithuanian military, the police force and local volunteers. The “Organized Murder Units” would appear in villages where Jews lived, usually after the first pogroms. The scared and hapless Jews were brutally concentrated into synagogues (which became, in fact, torture sites), in market places, on isolated farms or in other buildings. From there they were led, first the men, then the women and children, to the mass murder sites. Here they were forced, while being tortured, to hand over jewellery and other valuables they had carried with them, to undress and to descend into previously prepared pits where they were shot by gun and machine–gun fire. The wounded and those still alive were buried together with the dead in mass graves; their clothes and property were plundered by the murderers and local residents.

[Page xiv]

About 40,000 Jews who survived the mass murders in the summer and autumn of 1941 and who were destined to serve as a temporary labor force for the German war effort, were imprisoned in ghettos in Vilna, Kovno, Shavli, Shventsian (Svencionys) and in several labor camps in eastern Lithuania. The despairing Jews were subject to inhumanly organized murders, euphemistically called “Actions”, and many were deported to countries outside Lithuania. With the Soviet–German front drawing nearer at the end of 1943 and in the first half of 1944, the ghettos and labor camps were liquidated and their remnants transferred to concentration camps in Estonia and Germany. When the Red Army returned to Lithuania in the second half of 1944, there were then about 2,000 Jews in Soviet partisan units and the same number in hiding places, where they had not been discovered. Others had found shelter with non–Jews, mostly in villages far from the central towns of Lithuania. If one adds the number of Lithuanian Jewish survivors to those who escaped or were exiled to Russia, and to those who survived the concentration camps in Germany, Estonia and elsewhere, it would seem that 94% of the 220,000 Jewish residents fell victim to the Nazi occupation, the greatest percentage in all Europe. It is not surprising that most of the remnants of the Shoah left Lithuania's blood–soaked earth: a considerable number of these survivors emigrated to Eretz–Yisrael.

One of those privileged to arrive in Eretz–Yisrael before the State of Israel was established, was the engineer Josef Rosin, the author of this book, having alone survived when his entire family was murdered in 1941 together with all the Jews in Kibart (Kybartai), in western Lithuania.

As in other places in Lithuania the massacre of this community was carried out by Germans along with Lithuanians, who availed themselves to the Germans in the cruel liquidation of their Jewish neighbors, and since then this community no longer exists.

Nearly fifty years after the complete destruction of his community, Josef Rosin decided to commemorate the loss of his family and community by producing the Yizkor Book Kibart, which was published in Haifa in 1988 by the Association of Former Kibart Citizens in Israel. In October 2003 a second extended and updated edition of this book was published, including more impressive photographs of Kibart community members, their institutions, their houses and important documents of community life.

[Page xv]

|

[Page xvi]

Since then Josef Rosin's documentation has expanded to 102 articles on other Lithuanian Jewish communities, which are included in three books: Preserving Our Litvak Heritage – A History of 31 Jewish Communities in Lithuania, edited by Joel Alpert, with the introduction by Professor Dov Levin, and published by JewishGen, Inc. 2003. This first book includes the Yizkor Book of Kybartai and 30 articles on other communities, some of which were situated relatively close to Kybartai.

The second book, Preserving Our Litvak Heritage – A History of 21 Jewish Communities in Lithuania, was published by JewishGen, Inc. in 2007 with the dedicated participation of people and institutions as above.

Now we are privileged to present to the general public and in particular to “Litvaks” (and surely to the historians, sociologists and genealogists) a third book, now published by the Friends of the Yurburg Jewish Cemetery, Inc. This book includes 50 articles on communities from all over Jewish Lithuania.

I am privileged to have known Josef Rosin for more than sixty–five years, since 1943 in the Kovno ghetto: there, we became partners in social and cultural activities in the underground organization of survivors of the Zionist–Socialist youth organization HaShomer HaTsair.

|

|

| Dov Levin (left) and Josef Rosin today |

By that time Josef was already respected for his outstanding knowledge of many subjects and his moderate and balanced point of view. In particular, he gave us immeasurable pleasure in the depressing atmosphere of the ghetto – he would play his wonderful music on his Garmoshka (Mouth organ). Later his melodies soothed us in the heavily forested partisan woods of eastern Lithuania, where we were privileged to be partners in the fight against the German Nazis and their local allies. This pleasant tradition continued, when in October 1945 we were together on an Italian fishing vessel, which transported 171 illegal Shoah (Holocaust) survivors to Eretz–Yisrael. During

[Page xvii]

those seven very difficult and trying days on board ship, he was given the job of allocating the scarce drinking water to the passengers. (It is doubtful that he then foresaw that, within about six years, he would hold the position of a department head of TAHAL – The Water Planning Authority for Israel!).

We arrived safely in Eretz–Yisrael, having evaded capture by the British police as illegal immigrants. Both of us joined Kibbutz Beth–Zera in the Jordan valley and there we worked for some time in the banana plantations. Even after Josef went to study at the Technion in Haifa and I at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, we would meet at least annually with other friends who had shared our ideals and life in the Kovno ghetto. And, of course, we and our families would again enjoy the music from his ever–present mouth organ.

In due course we came to cooperate even more positively at this scientific–literary level. This happened at the beginning of the 1990s, when I was elected by the directorate of Yad Vashem to serve as chief editor of the book Pinkas Kehilot Lita.

Knowing well his involvement and expertise concerning Jewish life in Lithuania and also his accuracy when writing, it was natural to approach Josef Rosin to accept the assignment of assistant editor. I am glad to state that from that time until the publication of the first edition of the Pinkas Kehilot Lita in 1996, we were blessed with productive and beneficial working relations, which, if indirectly, gave rise to the two books mentioned above and in the course of the issue I will refer to the content, significance and particularity of this third book.

The author also deserves appreciation for his care in including with awesome reverence most of the names of his hometown Jews. In view of the terrible tragedy that the Jewish people experienced, it is essential, in my opinion, to repeatedly mention the Jewish names of villages and even more so the names of Jews, particularly those who did not leave relatives or descendants. We hope that, in this way, their names, at least, will not be lost.

The author should be commended for using the old Jewish names of the towns, as a reminder to some of the Litvaks in Western Europe and America who may not know them or prefer to use the official Lithuanian names as enforced by the government for nationalistic–political reasons.

The results of this destructive and draconian policy can be seen in most of the names of the towns presented in this book; so much so that it is sometimes difficult to identify a town by the Hebrew or Yiddish or other name it has had for

[Page xviii]

hundreds of years, according to Jewish historiography and literature. In the 1930s the local Yiddish press was forced to use the official Lithuanian names.

Some of the 50 towns in this book have names that are quite different from their Yiddish names (shown in parentheses): examples include Seredzius (Srednik), Luoke (Luknik), Svedasai (Sviadushch), Moletai (Maliat), Leipalingis (Leipun), Plateliai (Plotel), Ylakiai (Yelok), Tytuvenai (Tsitovyan) and Garliava (Gudleve).

As in the previous volumes, which received positive reviews, the author presents his material in this book in a similar manner to that of the Hebrew book “Pinkas Kehilot Lita” mentioned above.

On page xiii above a map shows the reader the geographical location of each of the 50 towns that are included in the book.

No less important in this volume is the way in which the history of every community is divided into the three main periods of its growth and development since it first came into existence. These periods were:

[Page xix]

| Town (in Yiddish) | 1847 | % | 1855–57 | % | 1897 | % | Remarks |

| Akmyan | 667 | 543 | 36 | ||||

| Anishok | 80–90 families | about 400 persons | |||||

| Erzhvilik | 144 | 20 | |||||

| Gudleve | 469 | 49 | |||||

| Gelvan | 90 * | 1914 families * | |||||

| Girtegole | 530 | 82 | |||||

| Grinkishok | ––– | ||||||

| Grishkabud | 30 families | about 150 persons | |||||

| Kaltinan | ––– | ||||||

| Kamai | 453 | 944 | 85 | ||||

| Krakinove | 594 | 1,505 | 69 | ||||

| Krozh | 236* | 906 | 51 | 1816* | |||

| Kurshan | 1,542 | 48 | |||||

| Laizheve | 434 | 46 | |||||

| Loikeve | 418 | 55 | |||||

| Ludvinove | 1,055 | 69 | 369 | 34 | |||

| Leipun | 134 | 10 | |||||

| Luknik | 949 | 798 | 49 | ||||

| Miroslav | 60 families | about 300 persons | |||||

| Maliat | 1,006 | 725* | 60 | 1,948 | 81 | 1866* | |

| Nemoksht | 255 | 954 | 81 | ||||

| Pashvitin | 435 | 57 | |||||

| Pikeln | 1,206 | 68 | |||||

| Plotel | 171 | 28 | |||||

| Pumpyan | 694 | 69 | 1,017 | 69 | |||

| Remigole | 190 | 650 | 49 | ||||

| Rasein | 5,000 | 59 | 3,484 | 47 | |||

| Riteve | 1,397 | 80 | |||||

| Sapizishok | ––– | ||||||

| Siad | 1,729 | 1,384 | 69 | ||||

| Shadeve | 1,211 | 2,513 | 56 | ||||

| Srednik | 1,090 | 1,174 | 71 | ||||

| Shidleve | 245 | 506 | 42 | ||||

| Survilishok | 250* | 1873* | |||||

| Suvainishok | 684 | 80 | |||||

| Svadushch | 528 |

[Page xx]

| Town (in Yiddish) | 1847 | % | 1855–57 | % | 1897 | % | Remarks |

| Trashkun | 779 | 64 | |||||

| Trishik | 681 | 34 | |||||

| Tsaikishok | 432 | 65 | |||||

| Tsitevyan | ––– | ||||||

| Vabolnik | 508 | 545 | 46 | 1,828 | 78 | ||

| Vaigeve | 193 | 36 | |||||

| Vainute | ––– | ||||||

| Velon | 573 | 70 | |||||

| Vidukle | ––– | ||||||

| Vekshne | 1,120 | 1,646 | 56 | ||||

| Yelok | 775 | 57 | |||||

| Yezne | 170* | 31 | 1866* | ||||

| Zharan | ––– | ||||||

| Zhidik | 914 | 73 | |||||

| Total | 10,961 | 35,458 |

Table 1 includes data of the Jewish population and its percentage of the total population gleaned from the three census surveys of 1847, 1855/57 and 1897 carried out in Lithuania under Czarist Russian rule. In addition to the overall growth in the number of Jews in almost all of the 50 towns, they were the absolute majority in 22 of these centers by the end of the century. It is proper to note that during the nineteenth century the Jewish population in the 50 towns in this book grew by 25,000 despite the great emigration of Lithuanian Jews to overseas countries during this period.

In the 17 communities for which we have census figures for Jewish residents in both 1847 and 1897, 12 of them showed an increase: Kamai*, Krakinove*, Kruzh*, Maliat*, Nemoksht*, Srednik*, Pumpyan*, Remigole*, Shadeve*, Shidleve*, Vabolnik*, Vekshne* while in 5 others, Akmyan*, Ludvinove*, Luknik*, Siad* and the district center Rasein*, a decrease was recorded.

In the following towns the Jews constituted an absolute majority of the total population:

Kamai (85%), Girtigole (82%), Maliat (81%), Nemoksht (81%), Suveinishok (80%), Riteve (80%), Bolnik (78%), Zhidik (73%), Srednik (71%), Velon (70%), Siad (69%), Krakinove–69%, Pumpyan–69%, Pikeln–68%, Tsaikishok–65%, Trashkun (64%), Yelok (57%), Pashvitin (57%), Vekshne (56%), Shadeve (56%), Loikeve (55%), Kruzh (51%).

[Page xxi]

| Town (in Yiddish) |

Jewish Population in 1923 |

% of Total Population |

1945 | After 1945 |

| Akmyan | 360 | 25 | ||

| Anishok | 60–70 families | About 400 persons | 0 | |

| Erzhvilik | 222 | 46 | 0 | |

| Gudleve | 311 | 33 | 0 | |

| Gelvan | 473 | 0 | ||

| Girtegole | 213 | 0 | ||

| Grinkishok | 235 | 24 | 0 | |

| Grishkabud | 92 | 12 | 0 | |

| Kaltinan | 130 | 20 | 0 | |

| Kamai | 336 | 54 | 0 | |

| Krakinove | 527 | 50 | 0 | |

| Krozh | 470 | 0 | ||

| Kurshan | 841 | 0 | ||

| Laizheve | 127 | 15 | 0 | |

| Loikeve | 305 | 42 | 0 | |

| Ludvinove | 85 | 14 | 0 | |

| Leipun | 160 | 21 | 0 | |

| Luknik | 513 | 40 | 0 | |

| Miroslav | 124 | 32 | 0 | |

| Maliat | 1,343 | 76 | In 1959 – 1 | |

| Nemoksht | 704 | 69 | 0 | |

| Pashvitin | 274 | 33 | 0 | |

| Pikeln | 286 | 34 | 0 | |

| Plotel | 150 | 23 | 0 | |

| Pumpyan | 372 | 33 | 0 | |

| Remigole | 480 | 38 | 0 | |

| Rasein | 2,035 | 39 | 6 | In 1989 – 2 |

| Riteve | 868 | 50 | In 1959 – 1 | |

| Sapizishok | 293 | 50 | 0 | |

| Siad | 815 | 44 | 0 | |

| Shadeve | 916 | 29 | In 1959 – 4 | |

| Srednik | 449 | 48 | 0 | |

| Shidleve | 365 | 37 | 1 | woman |

| Survilishok | 104 | 24 | 0 | |

| Suvainishok | 250* | 1921* | ||

| Svadushch | 245 | 0 | ||

| Trashkun | 424 | 48 | 0 |

[Page xxii]

| Town (in Yiddish) |

Jewish Population in 1923 |

% of Total Population |

1945 | After 1945 |

| Trishik | 335 | 26 | 0 | |

| Tsaikishok | 324 | 56 | 0 | |

| Tsitevyan | 221 | 19 | In 1959 – 1 | |

| Vabolnik | 441 | 32 | 0 | |

| Vaigeve | 118 | 30 | 0 | |

| Vainute | 348 | 27 | 0 | |

| Velon | 335 | 71 | 0 | |

| Vidukle | 221 | 32 | 0 | |

| Vekshne | 300* | 0 | 1921* | |

| Yelok | 409 | 41 | 0 | |

| Yezne | 286 | 29 | 0 | |

| Zharan | 174 | 45 | 0 | |

| Zhidik | 799 | 89 | 0 | |

| Total | 20,508 | 10 |

Table 2 gives data of the Jewish population in the 50 towns during the period of independent Lithuania revealed by the census of 1923. It would seem that their numbers had decreased to a noticeable degree in 41 of the towns (altogether about 15,000 persons). Despite administrative manipulations by the authorities, the Jews retained their majority in nine towns (Kamai*, Krakinove*, Maliat*, Nemoksht*, Riteve*, Sapizishok*, Tsaikishok*, Velon* and Zhidik*).

Population statistics presented in the two tables show the early growth of Jewish communities in the 50 towns by the end of the first period (1897), their reduction during the second (1923–1940), and finally their absolute destruction in the third (1941–1945).

There is no doubt that the diminishing numbers of Lithuanian Jews was a result of the increasingly hostile attitude to Jews in the Lithuanian provinces. This foreshadowed the impendion of the slaughter of Jews in Lithuanian towns in the summer of 1941 long before the first German soldier appeared.

The multitude of zeroes in the penultimate column (1945) in Table 2 serves as a grim reminder that 100% of the Jews were exterminated in those places between 1941 and 1945.

After World War II and the shocking events of the Shoah the handful of Jews who returned to live in a few places of the state decreased from year to year from natural causes and also because of continued murders by local gangs who could not tolerate Jewish existence on Lithuanian soil. Also the number of Russian Jews who migrated to Lithuania after the war decreased greatly. In fact the Lithuanian government that once supported the local murderers of Jews and failed to order restitution of Jewish property to its owners, is now

[Page xxiii]

making an effort to reconstruct a few Jewish institutions such as cemeteries in order to encourage Jewish tourists to visit the graves of their relatives, many of whom were murdered by their own neighbors.

On a final note, the reader will understand the considerable differences in religious and cultural life between relatively large communities of more than a thousand Jews in the period of independent Lithuania (e.g. Rasein*, Maliat*) and smaller communities which numbered only several hundreds (e.g. Kurshan*, Shadeve*, Zhidik*, Siad*) and very small communities which numbered only a few dozen (Ludvinove*, Grishkabud*, Vaigeve*).

Despite this difference and others, the Jewish Popular Bank (Folksbank) had branches in almost all the communities described in this book.

The basic way of life of the communities featured in this book shows community life directed first of all to fulfilling religious commandments, e.g. Hevroth Kadisha (burial societies), cemeteries, synagogues and different Minyanim. In bigger communities there were prayer houses for groups of worshipers of the same profession, such as artisans, merchants, shop owners, and synagogue beadles. Special institutions for studying the Torah were established: Batei Midrash for adults, Hadarim for children and Yeshivoth Ketanoth (small Yeshivas) for youngsters. In most of the communities various groups of volunteers, acting under different names, worked in welfare organizations, including Bikur Holim for medical aid and hospitalization; Linath Hatsedek to support the poor and sick and to supply free medicines; Gemiluth Hesed providing small interest free loans to the needy; Zokhrei Petirath Neshamah, for commemoration of the deceased, and more.

Several communities established Volunteer Fire Brigades. These brigades, on more than one occasion, fulfilled an effective role in protecting Jewish communities in times of pogroms and riots. Here it must be noted that almost every town in Lithuania was ravaged by fire. Since most houses and synagogues were constructed of wood, most of the Jewish population was at some time rendered homeless. In such cases, the community Rabbis would publicize the disaster by mail, messengers and in later years also in the Jewish press in Hebrew and Yiddish, pleading for aid from near and far communities. On the whole help arrived as requested, and similar methods were adopted when other disasters struck, such as a virulent cholera epidemic.

[Page xxiv]

| Town (in Yiddish) | 1897 | % | Comment | Donors for the victims of the Persian famine 1871* |

Donors for the Settlement of Eretz–Yisrael1873–1904** |

| Akmyan | 543 | 36 | ––– | ––– | |

| Anishok | 80–90 families | about 400 persons | ––– | ––– | |

| Erzhvilik | 144 | 20 | ––– | ––– | |

| Gudleve | 469 | 49 | ––– | ––– | |

| Gelvan | families 1914* | ––– | ––– | ||

| Girtegole | 530 | 82 | ––– | ––– | |

| Grinkishok | ––– | 67 | 33 | ||

| Grishkabud | 30 families | About 150 persons | ––– | ––– | |

| Kaltinan | ––– | ––– | 11 | ||

| Kamai | 944 | 85 | ––– | ––– | |

| Krakinove | 1,505 | 69 | ––– | 190 | |

| Krozh | 906 | 51 | 1816* | 24 | 17 |

| Kurshan | 1,542 | 48 | 75 | ––– | |

| Laizheve | 434 | 46 | ––– | ––– | |

| Loikeve | 418 | 55 | ––– | ––– | |

| Ludvinove | 369 | 34 | ––– | 2 | |

| Leipun | 134 | 10 | ––– | ––– | |

| Luknik | 798 | 49 | ––– | 29 | |

| Miroslav | 60 families | About 300 persons | ––– | ––– | |

| Maliat | 1,948 | 81 | 1866* | ––– | ––– |

| Nemoksht | 954 | 81 | ––– | 96 | |

| Pashvitin | 435 | 57 | 24 | several | |

| Pikeln | 1,206 | 68 | 130 | 12 | |

| Plotel | 171 | 28 | ––– | ––– | |

| Pumpyan | 1,017 | 69 | ––– | ––– | |

| Remigole | 650 | 49 | ––– | 91 | |

| Rasein | 3,484 | 47 | 74 | 234 | |

| Riteve | 1,397 | 80 | ––– | 89 | |

| Sapizishok | ––– | ––– | ––– | ||

| Siad | 1,384 | 69 | ––– | 53 | |

| Shadeve | 2,513 | 56 | 128 | 57 | |

| Srednik | 1,174 | 71 | ––– | several |

[Page xxv]

| Town (in Yiddish) | 1897 | % | Comment | Donors for the victims of the Persian famine 1871* |

Donors for the Settlement of Eretz–Yisrael1873–1904** |

| Shidleve | 506 | 42 | ––– | ––– | |

| Survilishok | 1873* | ––– | ––– | ||

| Suvainishok | 684 | 80 | ––– | ––– | |

| Svadushch | 528 | ––– | ––– | ||

| Trashkun | 779 | 64 | ––– | ––– | |

| Trishik | 681 | 34 | 62 | 14 | |

| Tsaikishok | 432 | 65 | 101 | ––– | |

| Tsitevyan | ––– | ––– | 1 | ||

| Vabolnik | 1,828 | 78 | 41 | 20 | |

| Vaigeve | 193 | 36 | ––– | ––– | |

| Vainute | ––– | 57 | ––– | ||

| Velon | 573 | 70 | 25 | ––– | |

| Vidukle | ––– | ––– | 61 | ||

| Vekshne | 1,646 | 56 | 118 | 58 | |

| Yelok | 775 | 57 | ––– | 19 | |

| Yezne | 1866* | ––– | ––– | ||

| Zharan | ––– | ––– | ––– | ||

| Zhidik | 914 | 73 | 43 | ––– | |

| Total | 35,458 | 14 Towns of 50 (28%) |

20 Towns of 50 (40%) |

In Table 3 one can see the Jewish solidarity in the communities of Girtigole*, Rasein*, Pikeln*, Kamai*, Shadeve*, Nemoksht*, Tsaikishok*, Vainute*, Vekshne* and others, that expressed itself in donations of money to Jewish communities outside Lithuania, as far away as Persia (Iran) and certainly Eretz–Yisrael.

To illustrate this phenomenon, hundreds of donors' names are listed in this book. They were published in the pages of HaMagid from 1871 and Hamelitz from 1873 to 1904. This may be valuable for descendants seeking reference to their ancestors from genealogical viewpoint or whose tombstones in the cemeteries of Lithuania have been ruined by weathering or vandalism.

A few days before signing this Introduction the author and myself lost our long standing and devoted friend Hayim Galin who was with us for more than fifty years, beginning in the period of organizing resistance in the Kovno ghetto, our fighting in the partisan woods and finally in Israel.

[Page xxvi]

Finally, it is appropriate to mark with gratitude and appreciation the professional work of the outstanding American–born Litvak, our mutual friend Joel Alpert, who invested much energy in preparing this book with all its components and appendices which also have great historical value and human importance. This is an act of true kindness (Hesed shel Emeth) for the hundreds of people of the fifty Jewish communities that were destroyed, never to rise again.

I am a native of Kybartai (Lithuania). I was born on January 24, 1922 to Hayah (nee Leibovitz) from Marijampole and Yehudah Leib Rosin from Sudargas (Lithuania). They were the owners of a paper and stationary shop in Kibart (the Yiddish name of the town).

I received my elementary and high school education in Kibart, Virbalis and Marijampole. During the years 1939 to 1941 I was a student at the Civil Engineering Faculty of the Kovno (Kaunas) University.

I left my home for the last time on Friday, June 20, 1941, just two days before the German invasion into the USSR began. My parents and my sister stayed in Kibart and were murdered together with all the Jews of the town in July of the same year. I was in the Kovno Ghetto for more than two and a half years until the beginning of February 1944 when I escaped into the woods (first into the Rudniki forests and later into the Naliboki forests in Belarus). I remained there until the liberation by the Red Army. In August 1944 I returned to Kovno. At the end of March 1945, I joined a group of young Lithuanian Jews who determined that we should leave Europe and make our way to Eretz Yisrael; we became part of the movement that became known as the “Brikhah” (Flight) movement. I left Lithuania and after the tribulations of the illegal travel through Poland, Slovakia, Rumania, Hungary, Austria and Italy, I arrived in Eretz Yisrael on October 24, 1945 on a ship of “Ma'apilim” (Illegal Immigrants). During the stay in Rumania I married Peninah (nee Cypkewitz) from Wloclawek, who had made a similarly difficult journey from Poland.

We lived in Kibbutz Beth–Zera in the Jordan Valley for nine months. In the autumn of 1946 we left the Kibbutz and moved to Haifa, with the aim of continuing my studies at the Civil Engineering Faculty of the Technion. I was accepted in the second course (as a second year student) and after a further year delay because of the War of Independence; I completed my studies in 1950 with the degree of Engineer. In 1958 I received my M.Sc. in Agricultural Engineering from the Technion.

During the War of Independence I served in the Air Force in the Aerial Photography Unit and was discharged with the rank of Staff Sergeant. I served in the Army Reserves until the age of 54.

During the years 1950–1952 I worked at the Water Department of the Ministry of Agriculture and with the establishment of “Water Planning for Israel” (Tahal), I joined this firm, where I worked until my retirement on the first of April 1987. For more than twenty years I held the position of Head of the Drainage and Development Department of that firm.

In 1989, I published my “Memoirs” in Hebrew and in 1994 in English.

During the years 1987 through 1994 I wrote many entries for the Hebrew book Encyclopedia of the Jewish Communities in Lithuania (Pinkas Hakehilot–Lita) and participated in publishing this book as the Assistant Editor. This book was published by Yad Vashem in 1996, edited by Dov Levin.

In 2001 and 2002 I acted as the assistant editor for the publication of the Memorial Book of the Jewish Community of Yurburg, Lithuania–Translation and Update.

Most recently I wrote two books on the history of 52 Lithuanian Jewish communities, Preserving Our Litvak Heritage, Volumes I and II, published by JewishGen in 2005 and 2006, respectively.

I have a married son and a married daughter and four grandchildren.

Yad–Vashem Archives, Jerusalem.

Central Zionist Archives, Jerusalem: 55/1788; 55/1701; 13/15/131; Z–4/2548.

YIVO, NY–Lithuanian Jewish Communities Collection.

Kamzon Y.D. Yahaduth Lita, (Hebrew) Mossad HaRav Kook, Jerusalem 1959.

Yahaduth Lita, (Hebrew) Tel–Aviv, 1960–1984, Volumes 1–4.

Cohen Berl, Shtetl, Shtetlach un Dorfishe Yishuvim in Lite biz 1918 (Towns, Small Towns and Rural Settlements in Lithuania till 1918) (Yiddish) New York 1992.

Pinkas haKehiloth Lita (Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities in Lithuania) (Hebrew), Editor: Dov Levin, Assistant editor: Josef Rosin, Yad Vashem. Jerusalem 1996.

Masines Zudynes Lietuvoje (Mass Murder in Lithuania) vol. 1–2, Vilnius 1941–1944 (Lithuanian).

The Book of Sorrow (Hebrew, Yiddish, English, Lithuanian), Vilnius 1997.

The Lithuanians Encyclopedia, Boston, 1953–1965, (Lithuanian).

The Small Lithuanian Encyclopedia, Vilnius, 1966–1971, (Lithuanian).

From Beginning to End (The History of HaShomer HaTsair Movement in Lithuania) (Hebrew).

HaMeilitz (St. Petersburg) (Hebrew).

Dos Vort, Kovno (Yiddish).

Folksblat, Kovno (Yiddish).

Di Yiddishe Shtime, Kovno (Yiddish).

Specific references of each town appear at the end of each article.

All the Yiddish and Hebrew names were transliterated anew according to the rules issued by YIVO for this purpose.

Dates in the book are written according to the European standard, as day–month–year, so that, for example, Dec. 15, 1955 would be abbreviated as 15.12.55.

Because of technical difficulties the Lithuanian names of the towns and places (except of the captions of the articles) are printed without the particular Lithuanian letters and symbols.

Agadah – Homiletic passages in Rabbinic literature

Agudath–Yisrael – Orthodox anti–Zionist organization

Aliyah (Ascent) – Immigration to Israel

Aron Kodesh – The Holy Ark in the Synagogue

Ashkenazi – Jew from Central or Eastern Europe

Benei–Akiva – Religious Zionist youth organization

Berith–Milah – Circumcision

Beth Midrash – A Synagogue for praying and studying the Torah

Bikur–Holim – Welfare society for helping the Ill

Beitar (Brith Yosef Trumpeldor) – The Revisionist youth organization

Bimah – Platform, mostly in the middle of the Synagogue, for reading the Torah

Brith HaKanaim – the youth organization of the Grosmanists

Bund – Jewish anti–Zionist workers organization

Ein Ya'akov – collection of legends and homilies from the Talmud

Eretz–Yisrael – The Land of Israel

Ezrah (Help) – welfare society who took over the functions of the Community Committees after their liquidation in many communities

Gabai, (pl. Gabaim) – Manager of a Synagogue

Gemara – Talmud

Gemiluth Khesed – Small loans without interest to the poor

Gordonia – Zionist Socialist youth organization

Grosmanists – Jewish State Party led by Meir Grosman

Gubernia (Russian) – Province

Gubernator – Head of Gubernia

Hakhnasath Kalah – Welfare society for helping poor brides to get married

Hakhnasath Orkhim – Welfare society for accommodate passers–by

Halakhah – Legal part of Jewish traditional literature

Hamelitz – a Hebrew weekly newspaper founded in 1860 in Odessa, later a daily newspaper in St.Petersburg, was closed in 1903

HaMagid – a Hebrew weekly newspaper, founded in 1856, was printed in Prussia near the border with Russia, was closed in 1890

HaNoar HaZioni – The youth organization of the General Zionist party

HaPoel – the sport organization of the Z.S. party

HaShomer–HaTsair – Leftist Zionist youth organization. In Lithuania its official name was: “The Young Guard Organization of Hebrew Scouts”

HaShomer–Hatsair–Netsakh – a splitting of the main organization

HeKhalutz (Pioneer) – Organization with the goal to enable its members to move to Eretz–Yisrael after first undergoing a serious course of training particularly in agriculture

Ivrith uThekhiyah – Hebrew and Revival

Khalutz or Halutz, (pl. Halutsim, Halutsoth) – Pioneer

Hitakhduth – Federation of several Zionist Socialist parties

Hovev Zion (pl. Hovevei) – lover of Zion

Humash – First Five Books of the Bible (Pentateuch)

Joint – Joint Distribution Committee

Kadish – Liturgical doxology said by the mourner

Kahal – Assembly

Kantonist – a Jewish boy removed from his family to serve in the Russian army

Karaite – member of Jewish sect originating in the 8th century, which rejects the Oral Law

Khalah, Halah – Loaf of bread made of white flour, prepared specially for Shabath

Khevrah–Kadisha (Hevrah) – Burial Society

Kheder (pl. Hadarim) – Religious Elementary School

Kheder Metukan – Improved Kheder in which secular subjects were also taught

Khupah – Marriage ceremony

Keren Kayemeth Le'Yisrael (KKL) – The Jewish National Fund. Its goals were buying land, planting groves and other reclamation works in Eretz–Yisrael

Keren Tel–Hai – The fund of the Revisionists after they split from the Zionist Organization

Keren Ha'Yesod – Jewish Foundation Fund

Khibath Zion (Love of Zion) – a 19th century movement to build up the Land of Yisrael before the establishment of the Zionist organization

Khovevei Zion – Members of the above–mentioned movement

Khasidim – a sect in Judaism founded by Rabbi Yisrael Ba'al Shem Tov

Khevrah – Society

Kibutz Hakhsharah – Training Kibutz for the Halutsim before their Aliyah to Eretz Yisrael

Klois – a small prayer room

Kultur Lige – Culture League, association of Yiddishists

Lekhem Aniyim – Welfare society for supplying bread to the poor

Linath HaTsedek – Welfare society for helping the ill

Magdeburg Rights – the Constitution of Magdeburg was an example of almost full autonomy for many towns in Eastern Europe

Magen David (The Shield of David) – The national emblem of the Jewish people

Maoth – Money

Maoth Khitim – Charity Fund for the poor for buying flour for Matsoth

Matsah (pl. Matsoth) – Unleavened bread for Passover

Matsah Shemurah – Guarded Matsah of wheat kept dry from the time of reaping

Melamed (pl. Melamdim) – Teacher in a Kheder

Meshulakh – Emissary for collecting money for different institutions in Eretz–Yisrael

Midrash – Homiletic interpretation of the Scriptures

Mikveh – Ritual bath

Minyan (pl. Minyanim) – Ten adult male Jews, the minimum for congregational prayer

Mishnah – Collection of Oral Laws compiled by Rabbi Yehudah haNasi, which forms the basis of the Talmud

Mithnagdim – Opponents to Hasidim

Mizrahi – Religious Zionist party

Mohel – Circumciser

Moshav Zekeinim – Home for the Aged

Oleh (pl. Olim) (Ascending) – Immigrant to Israel

Olim LaTorah – called up to the weekly bible portion

Orakh Hayim – The first column of the Shulhan Arukh of Rabbi Josef Caro

ORT Chain – International organization for spreading vocational education among the Jews

OZE (Initials of the Russian name) – International organization for improving the public and personal hygiene of the Jewish population, in particular of the school children

Pinkas – Notebook, Register

Pesakh – Passover

Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion) – Socialist workers party

Poale Zion–Smol (Workers of Zion–left) – Radical leftist party, was forbidden by the Lithuanian government

Rosh Yeshivah – Head of a Yeshivah

Sepharadi – Jew of Spanish stock

Shabbat – The Sabbath (Friday night / Saturday)

Shamash – Synagogue beadle

Shas (Abbreviation of Shisha Sidrei Mishnah) – The six books of the Mishnah

Shekhitah – Ritual slaughtering

Shekel (pl. Shekalim) – the membership card of the Zionist organization that granted the privilege to vote at the Zionist Congresses

Shokhet (pl. Shokhtim) – Ritual slaughterer(s)

Shtibl (pl. Shtiblakh) – Small prayer room for people of the same profession

Shul – Synagogue

Shulhoif –The backyard of the Synagogue

Shulkhan Arukh (The prepared table) – authoritative code of Jewish laws, written by Yoseph Caro (1488–1575)

Sidur – Prayer book

Simhath Torah – Rejoicing of the Law (Festival)

Somekh Noflim – Loans without interest for people who have lost their business or property

Tallith (pl. Tallithoth) – Praying shawl

Talmud – The commentaries on the Mishnah

Talmud Torah – Religious school

Tarbuth Chain (Culture) – Zionist Hebrew chain of elementary schools

Tehilim – Psalms

Tefillin – Phylacteries

Tifereth Bakhurim – Orthodox boys' organization

Tomkhei Aniyim – Supporters of the Poor

Tomkhei Tsedakah – Charity

Tsair – Young

Tseirei Zion – Young Zionists party

Tsedakah Gedolah – Charity

Va'ad – Committee

Va'ad Kehilah – Community committee

Va'ad Medinath Lita – Autonomous organization for Jewish communities in Lithuania (1623–1764)

Verslas – Lithuanian Merchants Association

WIZO – Women International Zionist Organization

Yavneh Chain – Religious Zionist Hebrew schools

Yerushalayim – Jerusalem

Yeshivah (pl. Yeshivoth) – Talmudical college

Yeshivah Ketanah – Small Yeshivah

Yiddishist – Ideological fan of Yiddish

Z.S. – Zionist Socialist Party

Z.Z. – Tseirei Zion Party – Young Zionists

| Lithuanian | Yiddish | Russian | Polish | Coordinates |

| Akmenė | Akmyan | Okmyany | Okmiani | 56°15' 22°45' |

| Čekiškė | Tsaikishok | Chekishky | Czekiszki | 55°10' 23°31' |

| Eržvilkas | Erzhvilik | Erzhvilki | Erzwilki | 55°16' 22°43' |

| Garliava | Gudleve | Godlevo | Godlewo | 54°49' 23°52' |

| Gelvonai | Gelvan | Gelvany | Gielwany | 55°04' 24°42' |

| Girkalnis | Girtegole | Girtakol | Girtokol | 55°19' 23°13' |

| Grinkiškis | Grinkishok | Grinkishki | Grynkiszki | 55°34' 23°38' |

| Griškabūdis | Grishkabud | Grishkabudy | Gryszkabuda | 54°51' 23°10' |

| Jieznas | Yezne | Ezno | Jezno | 54°36' 24°10' |

| Kaltinėnai | Kaltinan | Koltynyany | Koltyniany | 55°34' 22°27' |

| Kamajai | Kamai | Komai | Komaje | 55°49' 25°30' |

| Krekenava | Krakinove | Krakinovo | Krakinow | 55°33' 24°06' |

| Kražiai | Kruzh | Krozhi | Kroze | 55°36' 22°42' |

| Kuršėnai | Kurshan | Kurshany | Kurszany | 56°00' 22°56' |

| Laižuva | Laizeve | Laizovo | 56°23' 22°34' | |

| Laukuva | Loikeve | Lavkovo | Lawkow | 55°37' 22°14' |

| Liudvinavas | Ludvinove | Liudvenovo | Ludwinow | 54°29' 23°21' |

| Leipalingis | Leipun | Lejpuny | 54°05' 23°51' | |

| Luokė | Luknik | Lukniki | 55°53' 22°31' | |

| Miroslavas | Miroslav | Miroslavo | 54°20' 23°54' | |

| Molėtai | Maliat | Malyaty | Malaty | 55°14' 25°25' |

| Nemakščiai | Nemoksht | Nemokszty | 55°26' 22°46' | |

| Onuškis | Anishok | Onushki | Hanuszyszki | 56°08' 25°32' |

| Pašvitinys | Pashvitin | Paszwityn | 56°09' 23°49' | |

| Pikeliai | Pikeln | Pikeli | Pikele | 56°25' 22°07' |

| Plateliai | Plotel | Ploteli | Plotele | 56°03' 21°49' |

| Pumpėnai | Pumpyan | Pompyany | 55°56' 24°21' | |

| Ramygala | Remigole | Remigolo | Remigola | 55°31' 24°18' |

| Raseiniai | Rasein | Rossieni | 55°22' 23°07' | |

| Rietavas | Riteve | Retovo | 55°44' 21°56' | |

| Seda | Siad | Siady | 56°10' 22°06' | |

| Šeduva | Shadeve | Shadov | Szadow | 55°46' 23°46' |

| Seredžius | Srednik | Sredniki | Srednike | 55°05' 23°25' |

| Šiluva | Shidleve | Shidlovo | Szydlowo | 55°32' 23°14' |

| Surviliškis | Survilishok | Surwiliszki | 55°27' 24°02' | |

| Suvainiškis | Suveinishok | Suwejnuszky | 56°10' 25°17' | |

| Svedasai | Svadushch | Sviadostse | Swiadoscie | 55°41' 25°22' |

| Troškūnai | Trashkun | Traszkuny | 55°36' 24°51' | |

| Tryškiai | Trishik | Trishki | Tryszki | 56°04' 22°35' |

| Tytuvėnai | Tsitevyan | Tsytovyany | Cytowiany | 55°36' 23°12' |

| Vabalninkas | Vabolnik | Vobolniky | 55°58' 24°45' | |

| Vaiguva | Vaigeve | Vayguva | Wajgowa | 55°42' 22°45' |

| Vainutas | Vainute | Vainuto | Wojnuta | 55°22' 21°50' |

| Veliuona | Velon | Velioni | Wieliona | ––––– ––––– |

| Viduklė | Vidukle | Vidukli | Widukle | 55°24' 22°54' |

| Viekšniai | Vekshne | Vyekshny | Wiekszne | 56°14' 22°31' |

| Ylakiai | Yelok | Ilakyay | Illoki | 56°17' 21°51' |

| Žarėnai | Zharan | Zorany | 55°50 22°13' | |

| Zapyškis | Sapizishok | Sapezhishki | Sapiezyszisky | 54°55 23°40' |

| Židikai | Zhidik | Zhidiki | Zydyki | 56°19' 22°01' |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of the translation.The reader may wish to refer to the original material for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

Protecting Our Litvak Heritage

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 31 Jan 2019 by JH