|

|

|

[Page 221]

|

|

Israel, 1963

| Note from the translator:

Certain articles in Yiddish were a repetition from the Hebrew section. Therefore, I have only translated from the Yiddish section, those articles that were not in the Hebrew text. Harry Langsam z”l |

[Page 222]

Michael Walzer, Dr. Natan Kudish

Book Committee:

Israel: Michael Walzer, Dr. Natan Kudish, David Haar,

Michael Fast, Pinchos Goldman

America: Kalman (Charles) Buch, Moshe Frieder, Louis Rozenblit

Argentina: Eliezer Stempel

Belgium: Moshe Kneller

Printed in the Cooperative Print Shop “Achdut”

Printer's engraving: “Israeli Cinkograph”

Tel-Aviv, Levontin Street, 39

[Page 223]

by Dr. Yitzhak Schwarzbart

|

On the railroad from Krakow to Lwow, a not too big Jewish Community in the Polish city of Lancut, wove and spun a Jewish life. The city itself, however, played a major role in the history of Poland, and the Polish culture and tradition had a significant influence upon the Jewish population.

However, the Jewish Community had a strong adherence to Judaism in its spiritual and social-cultural institutions. In my book: “Between two World Wars”, which was published in 1958, naturally, I have also mentioned Lancut and her community activists.

The fate of the Jewish community of Lancut is a part of our great and horrible catastrophe. The details about the contribution of the Lancut community to Jewish life in general, before the catastrophe and about the perish and destruction of the Lancut Jewry will undoubtedly be described for eternal remembrance in this “Yizkor” Book. This assignment will be fulfilled by the Lancut Jews which, thanks to Providence, have survived from the greatest experience in our history.

Personally, I would like to dedicate a few words of awe and respect to the perished community of Lancut; for her enthusiasm and devotion to Zionist activity; for her brave struggle and suffering. I am expressing gratitude to my brothers and sisters and my colleagues for the preparation of this “Yizkor” Book. I believe that I have a right to such an expression, not just because I was asked by the Lancut Organization in Israel, but particularly, because of being the chairman of the executive of the Zionist Organization in Western Galicia and Silesia, to which the local Lancut Zionist Committee have belonged since 1919 up until the Holocaust.

Memories from my visit to Lancut in 1933 became enshrined in my memory to this day, here in the distant New York. The unusual, gentle stillness in the city in general, the Beit Haam that was built thanks to the effort of the entire Lancut community, and in particular, thanks to the tireless activity of the Lancut Committee headed by Engineer Spatz, became the centre of Jewish life in the city, the local laboratory of the effervescent activity, the always active Zionist dream, busy with local problems and political strategy. At the same time, the Beit Haam was also the centre of those striving Zionist Youths in Lancut to help build the future Jewish State, not with resolutions and enthusiasm but by actual preparations and ascendence to Eretz Israel, by culture and love to the Jewish past and future.

Here was the Beit Haam from where I had the honour to address the Jewish population in Lancut, a small dot on the map of a huge net of the World Zionist Organization, that Beit Haam has remained in my memory to this day.

There is no more Beit Haam today.

The State of Israel became the inheritor. It became the big Beit Haam after the Holocaust.

[Page 224]

by Dr. Abraham Chomet, Ramat Gan

Translated by Janie Respitz

Edited by Peter Jassem

A Word of Introduction

In order to become familiar with the beginning of Jewish life in the old historic city Lancut (in Polish Łańcut) as well as the conditions in which Lancut Jews had to struggle daily for their material and spiritual existence, from the earliest days until the final destruction during Hitler's time, we begin our work with an overview of the history of this city.

The first part of our work includes the history of Lancut, beginning in the year of its founding until the outbreak of the second world war (1939). The second part is dedicated to the history of the Jewish community in Lancut and this is why in the first part we do not offer a lot of information about Jews in Lancut who were connected to the general history of the city.

Important sources used for this work were monographs about Lancut by Stanislaw Cetnarski, the former mayor of Lancut and the historian Zenon Szust, who did not spare any effort in describing the history of the city in all periods of development. We owe many thanks to the people's doctor, W. Balicki, who took upon himself the task to collect all the documents and acts which have significance for the history of the city as well as those connected to Jewish life in Lancut.

The region where Lancut is situated is on the lowest terrace of the Carpathian Mountains, which stretch a few hundred metres from the north side of town until the valley near the Wisłok river. The southern mountainous area was cut through in ancient times with recesses where water flowed from southern heights and flooded large areas of wooded land creating swamps and mud which made reaching there almost impossible.

In the middle of these swamps stood a mountain which from the earliest times was called Mount Łysa (or the Golden Mountain). On this mountain, where from the second half of the 14th century the castle of the noble Pilecki family stood, colonists would gather to find means to exist.

In the 12th, 13th and beginning of the 14th century Lancut was an empty, uninhabited area with swampy forests filled with wild animals. In the middle of these forests was an enclosed road with a few narrow gates. There were watch towers erected to protect these gates. The names of these towers became names of various places, for example “Strażnica”. According to the hypothesis of the historian Szust, the name Lancut originates from one of these watch towers, (called Landeshut), although the second hypothesis is more probable as it says the name Lancut derives from the Bavarian locality Landshut where many of the early German colonists came from.

[Page 225]

The area surrounding Lancut was swampy, and it was difficult to approach from the east as well as west and north. But from the south Lancut did not posses any natural defense possibilities. Therefore, on the flat soil, a wall was built from earth and in the southeastern corner of the town's fortification stood a walled gate which was called “Przeworska Gate”. Across stood a second fortified wooden gate.

Although Lancut was not far from the castle on the Golden Mountain, the town, which only had small wooden houses, could not protect itself against the frequent attacks by enemy forces who destroyed the town and robbed and plundered the population. Such attacks occurred in 1498, 1502, 1523, 1624 and 1657. Only the castle on Golden Mountain could repel the enemy's attacks.

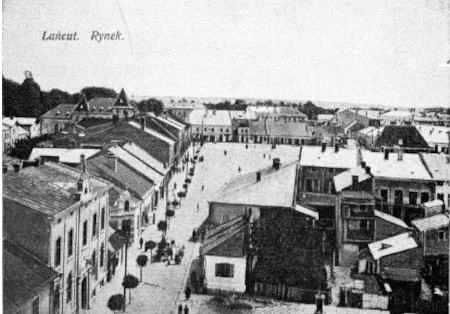

The historians of Lancut ascertained, that during the first period of its existence, the town occupied the area of the old marketplace which in 1883, in honour of the 200th anniversary of the victory over Vienna, was named “Sobieski Square”. As previously mentioned, among those who founded Lancut and organized municipal activities were colonists from the Bavarian region of “Landshut”. They received privileges in accordance with the Magdeburg Laws. Lancut received a statute from the Polish King Casimir the Great in the years between 1350 – 1360. According to the church records, the City of Lancut was founded in 1349 because in that year the Latin Catholic Parish was founded.

Surrounding the castle on “Golden Mountain” there was without a doubt a market which provided the administration and military personnel of the castle with produce, handicrafts made by artisans and primitive toiletries. Lancut was founded around this marketplace near the castle at first as a small settlement and later as a city founded on German law. In the area between the “Golden Mountain” and the old town (the old marketplace) a wider market was built and from each corner of the new market a street emerged. The Town Hall was built in the centre of the new marketplace.

At first the people who lived in Lancut were personally or economically dependent on the owners of the castle to whom the town also belonged. The first historic ruler over the region was Otto Pilecki who already in 1381 permitted the German Hansel Lang to establish a village called “Handzlówka” just south of Lancut.

Following Otto Pilecki's death in 1382 Lancut was inherited by his daughter Elżbieta, who later, in 1417, already a widow after her husband Wincenty Granowski died, married the Polish king Władysław Jagiełło. All the property which belonged to Elżbieta were given to her son Jan Pilecki by Jagiełło. Only two years after her marriage to Jagiełło, Elżbieta got sick and stayed mainly in Lancut where King Jagiełło came to visit her many times until her death in 1420.

The transportation line had a great influence on the development of the city which connected the west with Red Rus for centuries. This road was called “The Ropshitz Country Road” because the Imperial Toll House was situated in Ropczyce (Ropshitz in Yiddish). The town was built in the length along what is today Dominican Street which was the main transport line and later was extended to connect Lancut with Krzemienica where the majority of the German colonists resided. The eventual widening of the town reached down the road which led from Lancut toward Leżajsk and Sokołów through Kańczuga and finally, north of town where most of the Polish locals lived.

By the middle of the 15th century Lancut was already an important economic centre in relation to its population. In 1458, 1464 and 1465 many important meetings took place in Lancut with delegates from Przemyśl and some of the other largest cities of that time in order to consult in economic and especially commercial matters based on the model of the municipal associations in Germany.

In 1447 Jan Pilecki received the right from King Casimir Jagiellończyk to establish a yearly fair every year for one week on a pre-determined date. These fairs became the most important source of income for the population as well as for the owners of the city. Because of this a controversy ensued between rulers of the neighbouring Rzeszów (Raysha in Yiddish) and the owners of Lancut each making great efforts to liquidate the fair in the neighbouring town.

After the death of Jan Pilecki, Lancut was handed over to one of his three sons, Stanisław, who

[Page 226]

in 1488 built a church in Lancut and later, in 1491 a second church and another one for the Dominicans.

In the middle of the 16ht century Lancut became renowned due to the owner of the town at that time, Krzysztof Pilecki, who joined the reformist Lutheran religious movement and took with him a majority of the population of Lancut. Lancut became one of the most important dissident centres in Poland. Krzysztof Pilecki chased out the Dominicans as well as the priest from the Catholic parish, transforming the Catholic church into a Lutheran one. For 80 years, the Catholic residents of Lancut prayed in a small wooden prayer house in the neighbouring village Sonina. In 1565 and 1567 two important Protestant Synods were held.

The first historic document in which the name of the city of Lancut is mentioned is a Papal Bull dated 1378 which authorized the Dominican church in Lancut. We can surmise that by then Lancut was already a town of significance and already a past a period of development.

There is also an act put forth by Otto Pilecki in 1381 stating the place Lagendorf, which was in Lancut county, and no longer exists today, received legal status. Witnesses of the assemblage of this act were the village magistrate of Krzemienica, the largest village in Lancut county, the village mayor and 4 aldermen from the city of Lancut. This act also shows us that by the end of the 14th century Lancut had had a developed municipal order.

More information about Lancut can be found in the documents of Cardinal Demetrius from 1384 which mentions the tithe for the Przemyśl diocese in the Lancut church district. This act as well as the documents concerning the locality of Lagendorf are two important sources for the history of Lancut county and for the city of Lancut, because they bear witness to the fact that the district of Lancut, in the second half of the fourteenth century was well developed and the population of Lancut and the residents of the surrounding villages were tightly connected with the social – societal fibre and common interests which were boldly expressed in the institutions of market and fairs.

There were good economic relations between Lancut and neighbouring towns which branched out even more in later periods, when Rzeszów and Lancut belonged to the same Lubomirski magnate family. Similar relations existed between Lancut and Tyczyn because for a few hundred years both towns were owned by the Pileckis. Besides this, Lancut was connected with Leżajsk but only until the time when Lancut belonged to Stadnicki who for many years was at war with the magnate Łukasz Opaliński who had his residence in Leżajsk.

As a result, Lancut remained in good relations with neighbouring Przeworsk to the east and as was emphasized by Zenon Szust, the acts of the branches of the Przemyśl land authority in Przeworsk began in 1437 and since then Lancut has remained in regular contact with Przeworsk.

Until the partition of Poland Lancut formally and administratively belonged to Red Rus and together with neighbouring towns of Rzeszów, Przeworsk and Jarosław, in the mid- 14th century belonged to a territory which was under special control of Casimir the Great. Now the doors opened wider to Red Rus and further east and Casimir the Great made all efforts to unite all of Red Rus with Poland.

In the first stage of development the German colonists were the domineering element in town. Proof of this, as presented by Zenon Szust, were the town records of Lancut from the years 1539-1559 and from 1575-1591 in which property transactions were registered by established by German colonists. The economic situation at the end of the 14th century, beginning of the 15th century was at a high level. Until today, you can find in the archives the statute of the Lancut handicraft guild from 1406 written in German. The fact alone, that in 1469 this statute served as an example in 1469 for weavers in Lemberg (Lwów in Polish, now Lviv, Ukraine) illustrates that Lancut was already an important economic centre and at that time the weaver's branch in Lancut was well developed. Already in the 15th century Lancut was in active business contact with Lemberg because Lemberg was supplying Lancut with spices, herring, wool, and various foods.

[Page 227]

Also, the fact that in the second half of the 15th century meetings took place in Lancut with delegates from larger towns who came to consult about common economic business matters shows the importance of Lancut in economic life of the day.

Based on these facts, we can without a doubt affirm that Lancut, at the above-mentioned time period (the 14th and 15th centuries) was a city which had a well established significance in business of the day. By the end of the 14th century and the beginning of the 15th century there was a significant and impactful circle of merchants living in Lancut.

In the year 1578 Lancut was taken over by the son of Krzysztof Pilecki whose name was also Krzysztof. He registered the town and its estates to his wife Anna and when her husband died in 1586, she ceded Lancut and the surrounding villages to Stanisław Stadnicki, the so-called “Lancut Devil”, whose rule was tragic for the city resulting in many years of stalled development.

His hatred of the Catholic church was not new as in this regard he continued the anti-Catholic attitude of the previous ruler of Lancut, Krzysztof Pilecki and his sons who made Lancut renown in the Protestant world. Stadnicki had the reputation of being among the worst fortune hunters who appeared on the Polish arena before the partition and for this he was know as “The Lancut Devil”.

With his cruelty and debauchery, he instilled fear in the inhabitants of Lancut and the surrounding area. He used all means, even violence, to increase the income of his estates in Lancut. It began with the issue of a fair which in the time of Otto Pilecki took place in Lancut every year on April 23rd and later, prohibited by the Polish kings thanks to the efforts of the owners of neighbouring Rzeszów where the fair took place yearly two days later, meaning the 25th of April. Stadnicki did not respect the decision by the Polish king and ordered the yearly fair to be held in Lancut as before on April 23rd. Since 1600 he attacked the merchants on the road to Rzeszów demanding large payments. This led to an armed struggle between Stadnicki and the owners Rzeszów, including Ligęza, which lasted for years and ended tragically for Stadnicki.

He also participated in an armed revolt against the Polish King Zygmunt III and when this adventure also did not end well for him, he entered into a dispute with the village elder of neighbouring Leżajsk, Łukasz Opaliński. The fight between these two enemies was long and bloody. After a few small victories by Stadnicki a larger battle took place in 1608 on the road from Leżajsk to Przemyśl. When Stadnicki's soldiers began to retreat, Opaliński's fighters chased Stadnicki's people, arrived unexpectedly in Lancut and took revenge on the residents whom they robbed and murdered. Part of the city was burned; the town's records were destroyed as well as documents of privilege. They robbed the churches and the castle on “The Golden Mountain” was robbed and burned.

Stadnicki managed to survive and immediately returned to Lancut where he took revenge on everyone he suspected took part in robbing the castle.

In 1610 there was finally a decisive battle between Opaliński and Stadnicki, where Stadnicki was killed leaving behind three sons. The youngest, Stanisław, remained alone and could not pay his father's debts and in 1629 left Lancut paying of 250,000 Polish zlotys to the Duke Stanisław Lubomirski, the governor of Rzeszów.

In Stadnicki's time, the population of the town, as recounted by Zenon Szust totalled 1,785 in 1589. That number dropped by a third and continued to decrease.

The new owner of the city, Stanisław Lubomirski, returned the city to its Catholic character, chasing out dissidents and bringing back the Dominicans returning their church and estates to them.

In 1629 Lubomirski began to build a magnificent, fortified palace in the village of Sonina which was completed in 1641. Lubomirski also looked after security of the town and devoted a lot of attention to the development of business and trade in town. The population began to grow and

[Page 228]

the area of the town was expanded. As before, the residents of Lancut did not only live within the fortified city; they created homes outside the fortifications which surrounded the town.

Stanislaw Cetnarski mentions in his book the fact that there was a hospital a short distance from the town's border, or actually an asylum for the poor elderly as well as a small church on the road to Rzeszów which today is called Dominican Road.

Cetnarski also points out that until today there are documents we know of that talk about artisans who worked in the suburbs of Lancut as well as the residents of the town itself that had to pay duties to the owners that were connected to the general duties collected to protect the town. This expansion, according to Cetnarski extended further toward what is today Grunwaldzka and Konopnicka streets in the area of today's suburb (Przedmieście), because that region was closest to the main transportation line.

When the area of Lancut became crowded they began to build in “Przedmieście” and “Podzwierzyniec”, which from the start were just extensions of the city's territory and for a long time was not considered a separate community. In later years when Galicia belonged to the Habsburgs, these two suburbs constituted independent communities.

After the death of Stanisław Lubomirski in 1649 Lancut was inherited by his son Jerzy Sebastian who distinguished himself during the Swedish attacks on Poland.

After the victory over the occupiers in January 1656, King Jan Casimir stopped over in Lancut as a guest of the duke Jerzy Sebastian whose castle was temporarily transformed into a residence for the king and his adherents.

Lancut suffered greatly from battles against foreign forces. When the Duke of Siebenburgen, Rákóczi, invaded Poland in 1657, he captured entire regions of Polish land and destroyed everything that stood in his way. When he arrived at the walls of Lancut castle, despite all efforts, he could not conquer. However, the town of Lancut fell and when his wild soldiers captured it, they burned it along with the old Pilecki castle which was never rebuilt. Both churches were burned as well as the old town hall and houses which were situated around the Lancut marketplace.

The administrative and economic activity of both Lubomirskis, Stanisław and his son Jerzy had great significance on the town. At the time, the significance of the guilds rose resulting in the development of trade, thanks to, without a doubt the well organized and numerous inhabitants of the castle.

The oldest and strongest guild at that time was the Lancut weaver's guild whose statutes were documented in 1406. According to a decision made by Stanislav Lubomirski, new statutes were created for this guild based on the guild organization in Przeworsk. The difference was that the Lancut guild statutes contained a special directive for military duty of the artisans in the event of an attack on Lancut which was at the time a fortified town. The novelty was that this document was written in Polish which showed the German element which in the 14th century was an important factor for the development of the town had already assimilated by the 17th century through economic and family connections with the Polish element. In the 17th century the German language was used only in municipal offices in Lancut.

New luxury business had now been established like foundry manufacturing of candelabras and small bells, however the most developed was weaving.

From Zenon Szust's monograph “Lancut and its Surroundings” (Warsaw 1959) we learn that according to calculations of revenue and expenses in Lancut from 1563-1607, in 1579, out of 115 taxed artisans, 37 were weavers, meaning 30% of all artisans.

The frequent fairs helped the development of business. On January 28, 1656 during the sojourn of King Jan Casimir in Lancut, the city obtained the privilege to hold fairs.

The process of continuous development of the town was weakened in the second half of the 17th century when Duke Jerzy Lubomirski took a hateful political stand against the Polish king and led a

[Page 229]

rebellion. The Polish Sejm sentenced him with expulsion from the country. He died in Wrocław in 1667.

Jerzy Lubomirski left behind 5 sons who inherited the Lancut estates, however his widow Barbara ruled the castle which held a lot of weight in the development the town's guilds. In one of her privileges she donated a large piece of land in the western part of town to the weaver's guild to build houses for members of the guild.

The situation in Lancut became more difficult and critical when one of Jerzy Lubomirski's sons, Hieronim Augustyn, joined the Warsaw Confederacy which opposed the Polish King August II. Only when August II captured Lancut and stayed there for a short time, did Hieronim surrender and returned to the side of the king.

In 1699 his older brother Stanisław Herakliusz took over Lancut and the castle. He was a close friend of King Jan Sobieski, an important businessman and well educated. The first thing he did was rebuild the part of the castle that had been burned. After his death in 1702 Lancut was inherited by his son Franciszek who two years later gave the town over to his younger brother Teodor, a talented and excellent administrator. His foremost concern was to raise the level of comfort and prosperity of the population of the town and the surrounding area, displaying special interest in the town's guilds who he provided with gifts and privileges.

As a result of a compromise, in 1745 his inheritors divided up the inheritance in this manner: Lancut and the castle fell to Duke Stanisław and Przeworsk and the other estates were received by Duke Antony Lubomirski. Duke Stanisław Lubomirski (the third) was the last Imperial Marshal of Poland and had the reputation of being a praiseworthy respected businessman to whom the Polish King Stanislav August gave a medal for his great political accomplishments for Poland. At the same time, he did not forget the Lancut castle nor the town itself. He married Countess Elżbieta Czartoryska who at that time was considered the wealthiest countess in Europe. The countess chose Lancut as her permanent residence and she rebuilt the castle and the fortress and turned it into a magnificent comfortable palace, with salons furnished with very expensive artistic furniture, paintings and galleries of magnificent statues.

The residence of Countess Elżbieta in Lancut to a great extent contributed to the economic existence of the town because from that time on the population of Lancut remained in close contact with the residents of the castle. Many of the town's public institutions received help and donations from the owners of the castle, resulting in more earning opportunities in business and trade.

After the death of Duke Stanisław, the countess began to leave for longer stays in Paris. The outbreak of the French Revolution forced the countess to leave France and return to Lancut. Many French immigrants returned with her, including the count Antoni Bourbon, the future French king Louis the 18th as well as the well-known writer Madame de Staël. At this time, guests were received at the castle including Kościuszko, Kołłątaj, Jan Śniadecki and other famous personalities.

Countess Elżbieta survived the entire tragedy and chaos of the Polish Empire during the Napoleonic Wars in the Lancut castle. After Napoleon's defeat, when all victorious representatives gathered in Vienna, Countess Elżbieta went to Vienna as well, despite her advanced age. At the Peace Congress of 1815 she used all her previous connections to help Polish patriots in their political negotiations. She died in Vienna in 1816 and thanks to her great grandson Count Alfred Józef Potocki[1], her remains were brought to Lancut to the family grave.[2]

[Page 230]

As already mentioned, Countess Elżbieta survived the first partition of Poland. In the summer of 1772 Lancut was taken over by the Austrian regime. The new political relations had a terrible impact on economic situation of the town of Lancut. The Austrian government overwhelmed Galicia with new decrees, commands, and administrative orders in order to make the occupied land more dependent on the German-Austrian central provinces.

Lancut fell to the level of a second-degree small town. The population decreased and as Stanisław Cetnarski wrote, over the next few years, there were no more than two and a half thousand people.

The residents of the town had to pay enormous amount of taxes which limited their earnings. To make matters worse, cheaper goods emerged from large Austrian and Czech industry taking away livelihood from artisans in Lancut.

A major change occurred in the relations between the residents of Lancut and the owners of the castle. This ended the material and personal dependence of the town on the master of the castle. Lancut became an independent administrative unit. The fortification walls which surround the town were abolished. The walls were leveled as they now lost their purpose.

The road from Kraków to Lemberg which was built between 1795- 1810 had great significance for the town. This so-called “Kaiser Road” offered shorter and more convenient connections with Rzeszów on one side and Przeworsk and Jarosław on the other side through Głuchów and Kosina. Lancut suffered economically from this as the population from the surrounding area as well as from Lancut proper looked for merchandise from larger businesses in Rzeszów. Many businesses which had once been significant in Lancut failed, like wool weaving, linen products as well as bronze production which employed many and for years provided income for a large portion of the Lancut population.

After the death of Countess Elżbieta the Lancut estates were run by a judicial administration and the entire duchy was divided in three equal parts, of which Alfred Potocki received the Lancut estates. Count Alfred excelled in the battels of the Polish Legion in Napoleon's army. After the unfortunate battle at Borodin, Alfred fell into the hands of Cossack patrols and was sent to Siberia until 1814. Right after Napoleon's defeat and Poland's dreams of liberation were quashed, Tsar Alexander pardoned all Polish prisoners and permitted them to return to their homes.

Count Alfred Potocki returned to Lancut. His concern for the town and the castle helped the development of the town.

Just as the economic situation began to improve for the first time after the fall as a result of the partition of Poland, in 1820 a fire destroyed practically the entire town. The fire began in the barracks in the so-called “Sztermerówki” (Sztermer was the name of the manager of the castle). All the wooden houses were lost in the fire as well as all the ancient and historical documents. The development of the town was restrained and the appearance of the town changed.

According to what Stanislaw Cetnarski describes, before the fire all the houses were wooden one-story houses in the old Polish style, except for larger buildings such as the synagogue, the church, the Catholic church, the castle and city hall. The shops around the marketplace which belonged to Jews were also burned. After 1820 it was forbidden to build wooden houses on the streets of Lancut. Every trade was concentrated on a different street, for example all the butchers were located on the street which ran from the market square to “targowisko” (editor's note: a larger marketplace in the town's outskirts), the blacksmiths were on the next street and all the weavers lived on the street which reached beyond the walls giving them the opportunity to bleach their linens in the nearby fields by the river. Today's Tkacka Street emerged on Jan Cetnarski Street. The “podcienie” (arkades) in the marketplace disappeared after the fire, and all that remained were

[Page 231]

the cellars which were under them. These cellars were covered and sidewalks were built over them. After the fire, where the one -story wooden houses once stood, two story brick houses were built.

By the second half of the 19th century Lancut began to recover from all the difficulties endured after the fire of 1820. The efforts to rebuild the ruined city began to bear fruit. The reconstruction was largely aided by the owners of the castle, the Potockis, who in 1853, in their two enterprises, liquor and a sugar factory, employed approximately 500 workers.

The abolition of serfdom in 1848 also influenced the improvement of economic relations in town as the farmer became a better consumer. This significantly widened the mutual economic relations between Lancut and the surrounding villages.

The railroad from Vienna to Lemberg which was completed in 1859 also helped in the cultural and economic development.

In 1862 Count Alfred Potocki died leaving behind two sons and two daughters. The majority of the estates in Lancut were taken over by the youngest, Alfred Josef Potocki. After completing his university studies, he served for a few years as an Austrian diplomat and then returned to Lancut where he gave up the administration of the Lancut family estates. In 868 he returned to political activity and first served as Minister of Agriculture in the Austrian government and later, in 1870 he became the Prime Minister of the Austrian cabinet. Finally, in 1873 he was nominated Imperial Governor of Galicia and remained in this post until 1883. The Austrian Kaiser chose him as Vice-Protector of the Academy of Sciences in Krakow. He died in Paris in 1889 leaving behind two sons. His son Roman, who occupied important political posts in the Austrian administration, settled in with the entire board of directors of the Lancut estates. The relations between the princely court and Lancut was weakening, especially when Roman Potocki ordered to close the park where in the summertime people would walk in the shade of the large trees. However, besides this, the duke did not break relations with the town and generously helped the poor portion of the Lancut population. Roman Potocki connected the town to the plumbing of the Lancut castle.

Duke Roman died in Lancut in 1915 and the Lancut estates were given to his eldest son Alfred the Third, who displayed great warmth and interest to the Lancut population and was even active in various social and communal institutions. He donated approximately 400 acres of fertile land to the invalids of Lancut and yielded land for the expansion of the slaughterhouse etc.

The entire administration and management of the castle lay in the hands of the Countess Elżbieta.

In 1867 Galicia gained autonomy which gave the Polish society as a whole more possibilities to strengthen the Polish regime's positions in Galicia and deepen the influence of Polish nationalism on the cultural and economic life in the land.

As in the rest of the county, many changes occurred in communal life. The leadership and city administration were taken over in 1879 by the engineer Jan Cetnarski, an energetic representative of the town's intelligentsia, who remained without interruption in the position of mayor on Lancut for 35 years until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

The economic situation improved greatly in the period of Jan Cetnarski's administration, and the outward appearance changed as well. Intensive communal activity developed the Polish intelligentsia. The city doctor Krawczyński helped the cultural institution “Mrówka” by donating his entire private rich library, laying a foundation for a significant cultural centre in Lancut. Two other libraries were founded at the same time, one at the “Official – Casino” and the other at the “Gwiazda” Society where the petty bourgeois gathered. All three libraries were destroyed during the First World War. Besides cultural institutions, during the period of transition between the 19th to

[Page 232]

20th centuries, more and more financial and economic institutions emerged in Lancut, mainly thanks to the Polish communal activist, the deputy of Lancut county, Bolesław Żardecki. These institutions had a great influence not only in Lancut, but in other places as well where they even had branches of Lancut's credit institutions. Żardecki was also one of the founders of the linen factory and weaver school in nearby Rakszawa.

This is how Lancut developed at a fast pace in the early years of the 20th century. In 1907 they opened a Humanities High School and a year later the city administration began to conduct electricity in the town which now had about 5,000 residents. This development of the town also had an influence on its appearance. The streets received convenient sidewalks and thanks to the completion of colonization, sanitary conditions improved. By 1911 the town received its own electrical establishment which provided all of Lancut and the surrounding area with electricity.

The outbreak of the First World War interrupted the continuous development of the city. In the first weeks of the war Lancut was captured by the Russians, who remained in the city until October 1914. During the first Russian invasion a temporary municipal administration was set up, which bore a purely pro-Russian Endek (that of the National-Democratic Party) character, headed by Dr. Szpunar, who the Austrian authorities interned after the town was liberated from the Russians.

The first Russian invasion resulted in a lot of damage. Besides the alcohol factory, the Tenenbaum family's house was burned as well as other houses.

On November 6th 1914, the Russians captured Lancut for the second time. This invasion lasted until May 12th 1915. Stanislav Cetnarski led the city administration and remained as mayor of Lancut after the Russians retreated and Lancut returned to Austrian control.

Understandably, the economic situation in town worsened during the war. The artisans did not have work and the few industrial institutions were at a standstill. Only the two large enterprises which belonged to Count Alfred Potocki remained active, the liquor factory, which after the fire during the first Russian invasions was moved to “Podzwierzyniec” and the alcohol refinery.

The Austrian Empire fell in October 1918. On the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, among others, the Polish State was founded which included, besides Crown Poland, Galicia. In the early months of Poland's independence, the Jews of Galicia suffered greatly. Their physical and economic existence was now threatened by excesses and pogroms, especially in the small towns.

This wave did not bypass Lancut. Masses of peasants from the surrounding villages were incited to violence by the Endek groups and returning soldiers attacked Jewish shops and stores in Lancut. Thanks to the courage of a quickly organized Jewish self defence, there was not great bloodshed nor larger robberies of Jewish possessions.

The social and economic life in Lancut now faced great disruption. At the same time the proximity to Rzeszów badly impacted the broader development of the city and the owner of the castle, the Potockis, did not help strengthen industry in town. The peasant population in the surrounding villages lived off their meagre fields in dearth and destitution. Consequently, the peasants from the Lancut region radicalized and in mass demonstrations from 1932-1936 demanded land and work. In the village of Grodzisko, not far from Lancut, this resulted in bloody skirmishes between the peasants and state police.

Until the outbreak of the Second World War Lancut did not undergo any great development and did not move beyond the framework of a provincial town.

Hitler's occupation was bloodily registered in the history of Lancut as in all of Poland. The historian Zenon Szust wrote the following about that period in his previously mention monograph (“Lancut and Surroundings”):

[Page 233]

“The vegetation of this provincial town was interrupted by the brutal attacks of Hitler's forces. Difficult tests by the occupiers oppressed the population and the Polish inhabitants lived under constant fear of “łapanki” (roundups) and transports to death camps”.The owners of the castle, the Potockis, hardly suffered because during the entire war the salons of the castle were used and maintained by the Nazis as headquarters.

The last Potocki, Alfred the Third, left Lancut in 1944 on the eve of liberation, with the Soviet army who took him abroad with 11 wagons filled with expensive cultural treasures, rare paintings and porcelain handicrafts. He died in Switzerland. His memoir was published in 1959 in London titled: “Master of Lancut – The Memoirs of Count Alfred Potocki”.[3]

In August 1944 the Soviet Army liberated Lancut from Hitler's occupation. Hitler's murderers exterminated the entire Jewish population but the town began a new period with a new regime in a new Poland. A new chapter began in the history of Lancut which has nothing to do with our work.

Original footnotes:

by Dr. Abraham Chomet, Ramat Gan

Translated by Janie Respitz

Edited by Peter Jassem

We have broadly and in great detail occupied ourselves with the history of the city of Lancut in order to provide the canvas of the historical development of the town, offering a full picture of the Jewish community in Lancut from its founding until its demise.

The historians of the city of Lancut, Zenon Szust and Stanisław Cetnarski, when writing the history of Lancut and its development, were either completely silent (Zenon Szust) or incidentally mentioned the Jews and their role and activity in Lancut, and Stanisław Cetnarski who does mention Jews in his above cited book[1] of Lancut. However, he presents their role in a narrow subjective manner as well as the significance of the role they played in the development of the town.

There is an amateur historian who lives in Lancut, the cultural activist Dr. Władysław Balicki, the most popular doctor in Lancut and the entire region, who for years has collected books, old documents and historic acts which are connected to the city and its environment. This honourable doctor, (now the chairman of the planning committee of the 600th anniversary of Lancut), is busy until today with collecting and organizing material on the history of Lancut. In a letter to the Jewish historian Dr. Gelber of December 12th, 1958, Dr. Balicki writes that in various libraries there are 10 city council registers dating from the 16th to 19th centuries which are important for the history of Lancut, and in connection to the 1000th anniversary of Poland, the anniversary committee would like to publish a few of these mentioned registers. Dr. Balicki emphasizes in this letter that it's possible they will find a lot of material about the Jewish history of Lancut in these records.

Meanwhile, we must manage with the material which we were able to obtain, and understandably, because of

[Page 234]

this, the cross section of history of the Jews of Lancut will not be complete and without a doubt, there will be gaps which we will be forced to fill with suppositions whose sources come from the general premises and facts concerning Jewish life in Poland and after the partition of Poland, in Galicia.

In order to answer the question when did the Jews settle in Lancut we must take two facts into consideration: firstly, when the town was founded and communal life was organized, German colonists were active. And secondly, Lancut and the surrounding villages belonged to a feudal magnate who decided about the social and economic life of the residents who settled on his land. He was the ruler, and from a certain point of view, he was the lawmaker of the region and had full influence on all municipal matters. The population was morally and materially dependent on him.

The settlement of German colonists from “Landshut” in the first half of the 14th century was not an isolated event. German colonization of Poland was a result of a deeper shock which Poland experienced in connection to the invasion of Tartar hordes in the eastern regions of the country. Already in 1241 and again in 1278 the Tartars invaded Red Rus and Poland and destroyed entire towns and villages. Entire comminutes were wiped out. In order to rebuild these destroyed places, the Polish rulers opened their doors to foreign colonists, particularly Germans and Czechs. Masses of German colonists began to wander toward Poland where they received the right to organize their social and economic relations on the basis of the Magdeburg Laws, giving them the opportunities to work in agriculture and to establish settlements. As a result, they were obligated to pay tenant farmers of the colonized land a tax in money or produce.

Many Jews also came to Poland with the German colonists This immigration of German Jews to Poland in the 13th century had a pure economic character because this opened great earning possibilities for them. Therefore, many German Jews settled in Poland, especially when the privileges of the Polish ruler Bolesław from Kalisz gave the Jews in 1264 the opportunity to freely do business in Poland. As stressed by Dr. Balaban in his History of Jews (Vol. 2) the Jewish merchant in Poland was at that time the only middleman between the producer and the consumer.

The Polish feudal magnates willingly received Jews from Germany after the Mongolian invasion mainly because the majority were townspeople who brought with them great experience in business and trade. They also introduced something new to Polish economic life: the credit system.

During the first half of the 14th century the German colonists from the Bavarian city “Landshut” settled in the region owned by the Pileckis, a magnate, feudal family. This area which they later called Lancut received municipal status in 1349 from King Casimir the Great.

We must accept that together with the German colonists from “Landshut”, Jewish colonists arrived from Germany and settled.[2]

As we know, together with the German colonists who came east, there were German Jews as well. The greatest wave of Jews flowing east was in 1348 – 1349 during the “Black Death”.

The fact is, when the town of Lancut was founded (1349), there is no doubt there was a connection with the colonization activity of Casimir the Great who supported the settlement of Jews in Poland. This serves as important proof that German Jews who were being chased out of Germany settled with Germans on the land of Lancut.[3]

Lancut was the object of special interest for the Polish King Casimir the Great, who in 1349 gave Lancut the status of a city. We must take into consideration that the king placed a lot of weight on the development of business in Poland and realized the economic talents and usefulness of the Jewish immigrants for Polish business while at the same time confirming the previous privileges of Bolesław of Kalisz bestowed on Jews in 1264.

[Page 235]

We can reach the conclusion, that at the same time Lancut was proclaimed a city, there were Jews living there who came from Germany.

Besides this, it is important for our hypothesis to note the fact that Lancut, in those years was situated on the country road that went from Rzeszów (Raysha in Yiddish) through Lancut, Jarosław and Przemyśl to Lemberg (Editor's note: Lwów in Polish, now Lviv, Ukraine). In the Middle Ages this was the only road (the Ropshitz Road) for trade from east to west (Ropshitz is Yiddish for the town of Ropczyce).

Although, as Dr. Schipper[4] recounts, in historical sources the Jewish community of Lemberg is not mentioned until 1400 and the Jewish community of Przemyśl does not appear before the period between 1400-1450. In later years, from 1450-1500, there are comments about a Jewish community in Jarosław. However, B. Mark[5] emphasizes: “We cannot just accept the fact that Jews only lived in the towns where Jews appear in documents, or by dates in Jewish cemetery since we know there were Jews living there in the 14th century. Not all Jewish communities are mentioned from their earliest years in documents”.

In the works of B. Mark, we find information about the existence of Jewish communities in Small Poland and in Red Rus in the 11th century. B. Mark maintains for example, that from the 11th century there is information about Jews in Przemyśl which was a crossroad of two important trade routes: Czechia - Small Poland - Red Rus and Hungary-Red Rus, and at that time there were vestiges of a Jewish community in Jarosław.

An important fact for us is that at the beginning of the 14th century a Jewish community existed in Rzeszów and between Lancut and all the other towns mentioned which are nearby, there was economic and trade relations. It is hard to imagine, that Jews had not settled in Lancut, which was situated so close to the above-mentioned towns where, by the 14th century, there were Jewish communities. There is no doubt they helped maintain trade relations between some towns on the long road from east to west, from Lemberg through Przemyśl, Jarosław, Lancut, Rzeszów, until Krakow and beyond, until Wrocław.

There are documented signs which prove our hypothesis that Jews lived in Lancut at the time when the Pileckis ruled.

The Jewish historian Dr. Gelber writes in his article (in the Hebrew portion of this Memorial Book), that in the archives in Warsaw there is a document from 1563 which contains a note about Jews in Lancut. It mentions a Jew from Lancut called Eliezer Feldman, but no details are provided. As we can see, this was the period when Lancut belonged to the Pileckis.

An important contribution to clarify the problem of when Jews settled in Lancut is the inventory of the owners in Lancut and the villages which belonged to Lancut estates in the years 1775, 1776 and 1777. We must thank the esteemed collector of Lancut antiquities, Dr. Władysław Balicki for the copy of the original which can be found in the National Archive in Warsaw. We will deal with the details of this inventory later in this book, meanwhile we will quote “Item 51” from this inventory under which the following appears: “a column with a cross at the place of the destroyed Jewish school”, We must add that in this inventory the town is divided into quarters and “Item 51” with the above mentioned column belonged to the part of the town which the inventory designates as the area of “Sokołów Gate until the Jewish School”. (Żydowska Szkoła) (Translator's note: even though they translate “Shul” to “Szkoła” which means school, I believe they mean synagogue. This will become clear later in the text).

Let us analyze this “Item 51”. We mentioned earlier the cradle of Lancut was the area around the “Golden Mountain”, where the castle belonging to the magnate Pilecki's family stood. The first rulers of Lancut. We also know, the first residents of the place called Lancut lived around this mountain. It is also worthwhile to mention, after the area was elevated to the status of a city and it spread further south, the area 200 metres from the “Golden Mountain” was called “the Old Town” and later, Sobieski Square (Plac Sobieskiego). On the north side of the Old Town, a bit further down the road, which is now called Grunwaldzka Street, was the Jewish cemetery which was closed in the first half of the 19th century. In this cemetery, of which nothing has remained after Hitler's invasion,

[Page 236]

was the grave of the famous rabbi, the great scholar Reb Naftali Horovitz of blessed memory, who came from Ropshitz and died in 1829. Thousands of Jews would travel from far and wide to Lancut to visit his grave on the anniversary of his death.

M. Walzer who is from Lancut and now lives in Israel pointed out that across from the cemetery there was an area the Jews of Lancut called “The Black Garden” and the older generation told of a pogrom that took place in that area. More important for us is the information provide to us by our friend Walzer, stating that on the land of the “Black Garden” a column with a cross stood before the last World War.

Another townsman from Lancut living in Israel, Nachman Kestenbaum, describing episodes of Jewish communal and cultural life in Lancut tells us that on the Sabbath, the Jewish youth in Lancut would meet at the old Jewish cemetery, sit on the walls of the “Black Garden” or on the hill across from the cemetery. Kestenbaum recounted there were many legends circulating about ghosts that would appear on Friday nights.

According to all the documents and information the matter of the “column with the cross on the spot of the destroyed school” which appears in “Item 51” of the inventory of inhabitants of Lancut in 1775 can be explained.

As we know, the column stands in the “Black Garden” which just like the old Jewish cemetery was not far from the hill with Pilecki's castle. It is already clear that we are connected to that spot. This is where the first Jews settled. We are trying to show they arrived in Lancut during the first half of the 14th century. Here on this spot was the beginning of the Jewish community in Lancut. This is where the first Jewish colonists in Lancut built their synagogue and cemetery.

In order to clearly provide the timing of the founding of the Jewish community in Lancut we will try to establish when the destruction of the synagogue occurred on the spot where they erected the column with the cross. (Translator's note: previously on page 235 they mention the destroyed Jewish School, Szkoła in Polish. Here they call it “Beys Kneses” or “Beyt Kneset” which is a synagogue. I believe it was the synagogue that was destroyed, not a Jewish school).

However, it is important to stress, that according to the documents, we have information saying until the second half of the 18th century there were three synagogues in Lancut:

One synagogue is mentioned in “Item 51” from the list of settlers in Lancut from 1775, which, as it is cited, was destroyed and in its place a column with a cross was erected. This was the synagogue, as we already mentioned which once stood on the land of the “Black Garden” not far from “Golden Mountain”.

The second was an old wooden synagogue about which the historian of Lancut, Stanisław Cetnarski[6] claims, stood in the south -eastern corner of the old marketplace, near the former Przemyśl Gate and according to his opinion, was burned. Cetnarski adds that before the last World War, the house of the Lancut resident Wagschal stood on the spot of the wooden synagogue.

The third synagogue, the New Shul, of which we have a lot of information, was built in 1761 near the aforementioned wooden synagogue, and today belongs to the Antiquities Buildings of Lancut.

Now we must deal with the question, when was the synagogue in the “Black Garden” destroyed? The answer to this question will allow us to figure out the time of the first Jewish settlers in Lancut. It is important us to stress for our future interpretations the synagogue on the land of the “Black Garden” was destroyed, as we read in the official list of settlers in Lancut in 1775. If, on the spot where the synagogue once stood, they erected a column with a cross, it was, without a doubt an act of anti- Semitism which must have been carried out in the vicinity of this area. We must add, the synagogue on the land of the “Black Garden” had to be destroyed much earlier than 1761 because before that year the wooden synagogue stood near the Przemyśl Gate and such a small Jewish community like Lancut could only have had one synagogue. So, by the time that there was the wooden synagogue, the synagogue at the “Black Garden” had already been destroyed and without a doubt, the column with the cross was already erected where the synagogue once stood.

When could have this hateful incident taken place against the Lancut Jewish community near the “Black Garden”? When could have they destroyed the synagogue on the land of the “Black Garden”?

[Page 237]

against the Lancut Jewish community near the “Black Garden”? When could have they destroyed the synagogue on the land of the “Black Garden”?

From the history of Lancut we know these early events occurred together with the acquisition of Lancut by the Pilecki magnate family which ruled until 1586. These magnates who occupied the highest state positions in feudal Poland kept order and calm in the City of Lancut which for them was a source of income. We also know these Polish feudal magnates did not hate the Jews and actually found them to be quite useful. Therefore, we must accept that at this time when the Pileckis ruled there were no anti -Jewish public incidents nor excesses and surely, the owners of Lancut would not have permitted the destruction of a Jewish synagogue.

A separate chapter deals with the period the last Pilecki, Krzysztof, who in 1549 converted to Protestantism and chased the Dominicans out of Lancut as well as the Catholic priests. At that time, Lancut was one of the most important dissident centres and in the years 1565-1567 two Protestant Synods took place there. In 1586 Lancut was taken over by Stanisław Stadnicki, a strong supporter of the Protestants. He used even more drastic means to chase out the Catholic population. In 1629, when Lancut was taken over by the Red Russian provincial governor, Stanisław Lubomirski, the period of Protestantism in Lancut came to an end. Now all the Protestant sectarians were chased out and the Dominicans returned. Their churches were returned to them.

Now we pose the question: Did the Protestants destroy the synagogue in the “Black Garden” between 1549 and 1629 or was it destroyed after 1629?

First of all, let us accept the possibility that the synagogue was destroyed at the time when Lancut was a centre of Protestant religion, meaning the first of the above-mentioned periods. For this point of view, we must provide some necessary words about the relations between Protestant sectarians and Jews in Poland.

The heretical leanings and reformation sects in the Catholic church began to spread in Poland already in the 14th and 15th centuries. By the first half of the 16th century there were already dissident sects in Poland and except for Husiatyn and other Protestant jurisdictions the Arian and the so-called Unitarians or anti-Christians were quite developed since they did not recognize the three units (Translator's note: The Holy Trinity) which is the foundation of Catholic belief. They were also called Socyns after the reformer Socyn who united all those in Poland who opposed the Holy Trinity into one sect. They were also called “Polish Brothers” and were also known as “Yudayzantn” [editor: reform Judeo-Christians] or Arians because just like the Reformist Bishop Arius, they stood between Jewish and Catholic beliefs. These sectarians were mercilessly persecuted and tortured in Poland and as a result the anger of the Catholic clergy was focused on the Jews who they suspected were trying to convert Christians. The Arians did not hate the Jews, especially when compared to the extermination of anti-Christian heretics of the Catholic inquisition. Therefore, we can establish the possibility that he synagogue in the “Black Garden” was destroyed by those who supported Protestant beliefs.

If we were to accept the second possibility that the synagogue was destroyed in the period when Lancut belonged to the Lubomirskis (1629), we must firstly stress that by that time in Poland the constitution of 1539 obligated the Jews living in towns and villages to be handed over as private property to the feudal magnates under their factual and legal jurisdiction.

When the first Lubomirski, Stanisław, took over Lancut, he rid the town of Protestants, invited back the Dominicans and Catholic priests and attempted to develop the town and raise the economy and provided the Jewish residents with protection. Given that all the members of this magnate family always had friendly relations with the Jewish residents of the town of Lancut and endowed them with privileges, we can presume that during Lubomirski's rule in Lancut there were no anti -Jewish excesses nor anti – Semitic events which could have resulted in the destruction of the Jewish synagogue.

[Page 238]

This was actually a time when Jews in Poland in their struggle for residential and business rights had the Christian residents and the clergy against them. However, the Jews of Lancut were in a better situation finding protection and guardianship given by the Lubomirskis who made sure Jews in Lancut could work and trade freely.

It is possible to assume the synagogue was destroyed when the Duke of Siebenburgen, Jerzy Rákóczi attacked Poland in 1657 completely destroying towns and villages. He also captured Lancut and burned the town. The following facts go against that possibility: firstly, it is known that in 1657, when Rákóczi attacked Lancut, the Jews there concentrated around the area of today's synagogue which was built in 1761 near the old wooden synagogue which was situated in the southeastern corner of the old marketplace. If we were to accept the old wooden synagogue was burned during Rákóczi's attack, Stanisław Cetnarski informs us that Theodore Lubomirski, who recaptured Lancut in 1702 helped the Jews rebuild the wooden synagogue so we cannot say that after the synagogue was burned a column with a cross was erected on that spot. To the contrary. The same Theodore Lubomirski later gave the Jews a place near the aforementioned wooden synagogue permitting them to prepare bricks in order to build a new synagogue which was completed in 1761. And as we already know, where the old wooden synagogue stood there was a house which belonged to Wagschal until the Second World War.

Familiarizing ourselves with the history of Lancut, we found certain vestiges that lead us to the time when the synagogue in the “Black Garden” was destroyed and where it becomes clear to us who would have erected a column with a cross on the spot where the synagogue once stood.

We remember, that during the fight between Stanisław Stadnicki (the “Lancut Devil”) and Duke Opaliński in 1610, a decisive battle took place where Opaliński's men arrived in Lancut and destroyed the town. A large portion of the town was burned. Opaliński's men robbed the castle on the “Golden Mountain” and without a doubt took the opportunity to destroy the Jewish synagogue which was situated in the vicinity of Stadnicki's castle on the “Golden Mountain”.

When the Dominicans returned to Lancut in 1629, they found ruins where the synagogue once stood. In Lancut, the Dominicans took over the role of inquisitors who drove away the Arian dissidents and persecuted all types of Reformers. They also did not treat the Jews with respect. The Dominican inquisitors took revenge on the Jews in Lancut for the sins of the Protestant heretics and Opaliński's soldiers erected a column with a cross where the destroyed synagogue once stood. This is the only way we can understand the connection between the destroyed synagogue and the column with the cross.

What other conclusions can we draw from the hypothesis that in the year 1610, in Lancut, in the vicinity of the old Pilecki castle, the synagogue was burned and a column with a cross was erected on the ruins?

From this fact we can specify approximately the time when the Jewish community took on certain forms of autonomy because smaller Jewish communities did not receive the right so quickly to build a synagogue and cemetery and hire a rabbi. Such a small community, in the beginning could not have covered all these expenses which were connected to supporting these institutions. Also, all these institutions needed permits from the feudal master to whom the place belonged. Therefore, such a community had to depend for a long time on a larger neighbouring Jewish community to which it was dependent for necessary communal matters. A larger community paid the imperial taxes from monies collected from smaller dependent communities. The head community and its affiliates shared a rabbi and Jewish court, a synagogue and cemetery. In those years, only wealthy communities could have their own cemetery. Jews from smaller communities brought their dead to larger Jewish communities in cities where there were already cemeteries.

When a dependent Jewish community developed in time, it first had to make efforts to get the right to build a synagogue, hire their own rabbi and then, obtain their own cemetery. Only then could an affiliate

[Page 239]

break away from the larger community and constitute an independent Jewish community. For a long time, the Jewish community of Lancut was an affiliate of the Jewish community of Przemyśl.[7]

By the 16th century, the Jewish community in Lancut had to be quite strong, because according to our hypothesis, the Jews of Lancut already possessed their own synagogue and cemetery.[8]

We have already shown in a previous chapter documentary proof of Jews already ling in Lancut by the second half of the 16th century. The historian from Lancut, Zenon Szust, in his monograph “The Middle Ages in Lancut”, published a list which was printed in a Lancut municipal register, of names of people who from 1539 – 1559 carried out transactions with the municipal founders of Lancut. This list which was printed in a Lancut municipal register from the above-mentioned years contains about 90 German names and about 170 Polish names. But after a detailed search, we find two names which are without a doubt Jewish, namely: one name “Shmialek” [editor: or Shmulek] which surely means Shmuel and the second name, “Żydkowa” which means the wife of “Żydek”, a Jew.

The same Zenon Szust emphasizes in relation to this list, the numbers provided concerning the town's population of that era, which is based on the town's register does not provide a true picture of the times. As for the German names on this list, they also do not prove that among those names there are no Jews, because as the well-known Jewish historian B. Mark explains in his book “The History of the Jews in Poland” (page 336), Jewish German historians emphasized the fact that in 13th and 14th century Germany Jews used German names or names derived from German. So, it is difficult to ascertain if some of the names that appear on this list are not Jewish even though the sound German.

The facts brought forth until now support our hypothesis that the first Jews settled in Lancut in the first half of the 14th century and that by the 15th century and first half of the 16th century a Jewish community already existed which was really

Let us now try to answer the question: how did the Jews live in Lancut from the second half of the 14th century until the beginning of the 17th century?

We mentioned earlier that when Jews settled in Lancut transport played a significant role. The Lancut historian Zenon Szust emphasized in his monograph “Lancut in the Middle Ages”, by the end of the 14th century Lancut was already developing as fairs and markets were already taking place there in which residents from neighbouring places would display their produce for sale. Twelve villages already belonged to the Lancut estates so by this time Lancut and the surrounding villages represented a large enough territorial unit which was connected by a common economic interest.

We learn from the history of Poland in the 14th and 15th centuries, Jews were the only ones involved in trade. Jewish merchants provided the magnate families and well as the local residents on the transportation route from Red Rus westward with such articles as herring, spices, and wool. The merchants would sell these goods at the fairs which took place at various times in cities and towns.

We can assume that Jewish merchants from Lancut in the 15th century supplied various kinds of merchandise and luxury articles to the Pilecki's court, which was one of the wealthiest families in Poland. In addition, it is worthwhile to mention that the Polish king Władysław Jagiełło, who would often visit his second wife (the daughter of Otto Pilecki, the widow of Kasztelan Granowski) in Lancut and had a close financial relationship with the Jewish banker Wolczko, who lived in Lemberg, without a doubt carried out credit transactions with the king's court as well as with the Pileckis, using Jewish middlemen who lived in Lancut.

Also, the economic contacts of the 14th and 15th centuries between Lancut and the neighbouring cities such as Rzeszów, Tyczyn and Przeworsk about which

[Page 240]

Zenon Szust mentions, could only be maintained by Jewish merchants that lived in Lancut, because only they, in this time period, were in contact with other Jewish merchants from other towns and organized close business contacts.

This was, without a doubt, the economic situation of the Jews of Lancut until 1586, when the town belonged to the Pileckis.

What were the economic relations with the Jews in Lancut when the town belonged to the Stadnickis?

The previously quoted historian Cetnarski describes the situation in Lancut from the time the town was taken over by Stanisław Stadnicki with the following words: “Since Stadnicki settled here the fate of Lancut was closely connected with the remarkable actions of a violent man, whose lust and passions were insatiable and did not respect any laws or ethics. A man who for a quarter of a century disturbed the surroundings, near and far and was always fighting with the neighbours and unpunished robbed, destroyed and murdered”.

It is understandable, that under such conditions, the Jews of Lancut could not carry out their business and had to cut all economic contacts with the neighbouring towns, particularly with the merchants in Rzeszów.

Zenon Szust informs us that in April 1600, Stadnicki held back all merchants from Lancut by force who he found on the road to Rzeszów on their way to the fair and threateningly forced them to pay ransom. There is no doubt these merchants from Lancut who were going to the fair in Rzeszów were Jews. It is clear, under such unsafe conditions, and fear for one's life and property, business had to cease. It is easy to imagine these types of relations resulted and the weakening of the Jewish community in Lancut. Later on, when Lucas Opaliński, the elder from neighbouring Leżajsk, Stadnicki's bitter enemy and his forces captured Lancut in 1608, they, as described by Zenon Szust, raped women, robbed and murdered the residents of the town, burned a portion of the town and destroyed all municipal records and privileges. It is understandable that the Jews could no longer remain in their wooden house and all they possessed went up in smoke.

The battle between Opaliński and Stadnicki lasted for two years, and as we already know, Stadnicki fell on the battlefield in 1610. The town of Lancut suffered terribly from the long fight between Opaliński and Stadnicki and ended up in ruins. No records or documents have remained from the period Lancut belong to the Opalińskis or Stadnickis from which we can derive information about the economic life of the Jews in those days in Lancut. Unfortunately, we do not have the possibility to familiarize ourselves with the records of the town of Lancut from the 16th to the 19th century or with the 20 Lancut parchment documents from the 14th until the 19th century as mentioned in the previous chapter and as Dr. Balicki reported, can be found in various Polish libraries.

The historian from Lancut, Zenon Szust, in possession of the town records from 1539-1559 and 1575- 1597, only stated that in this period which includes the years of the above-mentioned records, meaning the time when the Pileckis ruled, the domineering economic element in Lancut were the German bourgeois, because they, as Szust points out, carried out all the financial transactions which were registered in the above-mentioned town records. The historian Zenon Szust however, forgot one important thing. Those records only talk about transactions having to do with houses or rooms and had no connection to business, trade or credit. The rich patricians, those that carried out transactions with houses and made sure these transactions would enter town records, the German bourgeois, actually governed Lancut at that time, but a few residents in town were artisans and businessmen and they were the domineering economic element, although city council was governed by rich aldermen.

Zenon Szust was totally disinterested in Jewish problems in medieval Lancut. In the first part of his monograph “Lancut in the Middle Ages” he absolutely does not mention Jews in Lancut in this period. He refers only to bold and unjustified affirmations that in Lancut, in the Middle Ages the Polish Catholic population was growing. He maintains in another place, that at the time Lancut belonged to the Pileckis, meaning the Middle Ages, the economic

[Page 241]

dominant element in Lancut were the German patricians who were not yet Polonized.

From the same source, we learn, at the end of the 14th century and the beginning o the 15th century, Lancut was at a high level of economic development and already at that time there were fairs and markets taking place. And as we stressed earlier, if Lancut in the Middle Ages was so well financially developed, there is no doubt this was a result of praiseworthy actions by Jews.

We learn from the history of Jews in medieval Poland that by the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th century the credit and trade activity in Polish towns which were situated on the Ropczyce [Ropshitz] road from Lemberg all the way to Kraków and beyond was in Jewish hands.

Even when the weaving house industry developed on a larger scale in the 15th century, only Jewish merchants from Lancut were capable of taking these finished products and bringing them to other towns to sell at fairs and markets because at that time a Polish business element did not yet exist.

We have more detailed information of Jewish life and impact in Lancut from sources of the time when Stanisław Lubomirski took over Lancut in 1629.

In his last monograph “Lancut and Vicinity” Zenon Szust only mentions Jews in the first half of the 18th century, concerning more privileges given by the last of the Lubomirskis, Stanisław, who took over Lancut in 1745. Here the concern about Jews living in Lancut is obvious.

We can find more information about the Jews in the aforementioned monograph written by Cetnarski in which he occupies himself with the role Jews played in Lancut in this period, when Lancut belonged to the Lubomirskis. We read: “Jews, at the time of Poland's independence benefitted from the support of the rulers of Lancut” and “These people previously felt at home in Lancut, although on a limited scale” – “because the maps and counting of the population of Lancut in the 18th century show only a few Jewish families”, and “by the end of the 18th century, under the guardianship of Austria, Jews penetrated the marketplace where they acquired a few houses”.

Stanisław Cetnarski adds that Teodor Lubomirski, who took over Lancut in 1702 permitted Jews living in Lancut to build houses and work in business and trade except saddle making, the fur business, shoemaking, tanning and blacksmithing.

As we can see, Cetnarski's attitude regarding Jews was not very objective making it important for us to analyze the role and economic activity of Jews during this period when Lancut belonged to the Lubomirskis.

After the rulership of Stadnicki in Lancut, Stanisław Lubomirski took over in 1629. The first thing he did was rebuild the town which was destroyed in the constant battles between the “Lancut Devil” and his enemies. In order to raise the town economically, Lubomirski showed great interest in the development of trade and to achieve this he received the right from the Polish King Władysław in 1635 to open a “warehouse for fish and wine” in Lancut which brought greater income to the town.

With regard to the attitude of the Lubomirskis toward the Jews in Lancut we must remember the Polish magnates who were private owners looked after the Jewish population and protected them from attacks by the local Catholic population which regarded the Jews as competition, particularly the Catholic clergy. It is worthwhile to look at the interpretation of this issue by Dr. Meir Balaban concerning the relations between the Polish magnates and the Jews who settled in private towns which belonged to these magnates.

“Already in the second half of the 16th century” writes Dr. Balaban in his third volume of “Jewish History and Literature', “Jewish communities are emerging in new towns, especially in the eastern regions of the Polish Republic. Weary from constant battles with Polish petty bourgeois, Jews are immigrating from overpopulated imperial cities to new town and were maintained by the owner's trade and business privileges. They were permitted to settle in the marketplace, receive houses and gardens as well as wood and bricks to build a synagogue. Besides this, they also received privileges according to the model of general privileges of the Polish Kings. And so, we see that by the end of the 16th century we see a

[Page 242]

Jewish community in Żółkiew, a suburb of Lemberg. Jews begin to immigrate from Przemyśl to the neighbouring towns”. “One of the greatest curses of Przemyśl” writes Balaban, “was when the Lubomirskis took the Jews under their protection and at the same time obliged them to protect the town of Rzeszów”. In this “cursed privilege” form Rzeszów we find a passage which reads: “every homeowner must have as many guns as men, a pile of bullets to load them and three pounds of powder for the gun, and the Jews must have three stones of dry powder, a pile of bullets for the their guns, a half a pile for the cannons and 4 guns for the synagogue, and one Jew who will service the guns and shoot”.

Let us understand that Stanisław Lubomirski who was the magnate who took the Jews of Rzeszów, which was his town, under his protection, and who almost at the same time (1629) took over the city of Lancut from Stadnicki's inheritors, took the Jews there under his protection as well. They were already living near the Przemyśl Gate in the vicinity of Lubomirski's castle. As he did in Rzeszów, Lubomirski also gave the order in Lancut to protect the city. Cetnarski writes about this: “We see Stanisław Lubomirski' and his follower's concern for the security of the town in the content of the municipal guild privileges”, because “we often see privilege directives about the obligation to deliver war materials like powder, bullets etc.. as well as the obligation for residents of the town to possess weapons”.

Although Stanisław Cetnarski does not say a word about whether or not these orders from Stanisław Lubomirski and his inheritors were intended for Jews as well, there is no doubt that just like in neighbouring Rzeszów, these privileges in Lancut placed the obligation of possessing weapons on Lancut Jews who, according to Cetnarski, lived near the Przemyśl Gate, the most dangerous and easiest to attack.

After Stanisław Lubomirski, Lancut was inherited by his son Jerzy Sabastian who held the high position of Imperial Marshal and hetman. The new boss of the town dedicated a lot of attention to the development of business in town and when the Polish King Jan Casimir stopped in Lancut on January 28th, 1656, the town received the privilege to organize town fairs. Later, in 1671, Lancut received this privilege from Hieronim Lubomirski.