|

|

|

[Page 141-142]

Self-Defence

by Nachman Kestenbaum

In November, 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire Monarchy fell apart. A new Poland came into existence.

Throngs of soldiers, starved and depressed had returned from the fronts. Throughout the entire Galicia, the population expressed their joy about the liquidation of Austria and welcome the establishment of an independent Poland. In the name of the Galician Jews, political organizations had declared their loyalty and readiness to cooperate with the polish authorities in every venue of the life of the state, within the demands of equality and giving, the Jewish minority cultural and national autonomy.

The anti-Jewish excesses which had taken place all over Poland, in big and small cities in Galicia, did not omit Lancut. At the same time that the Polish soldiers returned home, Jewish soldiers also returned home. Insecurity overtook the Jews because with the falling apart of the Austrian rule, anti-Semitic fermentation was felt among the Polish population. The first people that became aware that there was a need to calm down the panic that had spread in the Jewish streets were the Zionist activists' ex-soldiers and officers from the Austrian army. During a mass meeting with the participation of Jewish soldiers and young people of the city, taking place in the quarters of the “Hashachar” Zionist Association, Dr. Abraham (Dolek) Druker stood there, dressed in his Austrian officer's uniform and spoke of the results of the latest anti-Jewish events. Nonetheless, he appealed to the Jews to stand by the Polish authorities in the building of the new country. After the meeting, a demonstration was organized of the soldiers and the young people, headed by Dr. Druker. They marched to the building of the Polish military command. The Polish commander agreed that the Jewish soldiers should join the military unit whose duty it was to safeguard the security and order in the city. A citizen's militia was organized for that purpose which included a Jewish unit under the command of Tzvi Ramer as commander.

In the first days of Poland's revival, a heightened mood had reigned in the city among the Jews. These were the days of the Balfour Declaration. Hope had awakened and the young people were ready to emigrate to Eretz Israel. Armed Jewish guards marched in the streets proudly wearing the ribbon with the Star of David emblem, knowing that they were protecting Jewish life and property.

The anti-Semitic current had grown stronger among the Polish public, having been influenced by the Polish National Party (Endetzia). The mob committed violent excesses against the Jews, which took place in almost every city in Galicia, which was a disgrace for the young Polish government. A wave of pogroms and attacks on Jews had flooded Galicia and had put in danger the physical and economic existence of the Jews.

The Jewish self-defence was on alert and was ready to repulse the Polish rioters which, according to rumours, were getting ready to pilfer Jewish stores.

During several meetings which took place in the Beit Hamidrash, the commander of the self-defence alerted the Jewish population to be vigilant and ready, to defend their honour, life and property of the Lancut Jewry. The young people enthusiastically responded to the appeal and placed themselves at the disposition of command of the defence.

According to the information, the rioters were supposed to attack the Jews on Sunday, 11th November, 1918, a day when hundreds of peasants came from their villages to the city to pray in church. The self-defence forces had concentrated in the public bathhouse in which, at that time, was the location of the offices of the Jewish community. All the Jews that were physically able to fight were armed. Some with rifles and some with a variety of firearms. All the members were tense and ready to fight back.

Luckily, that Sunday had turned out to be a quiet day. It was a false alarm. Possibly, the rioters had been informed that the self-defence were on alert. The Jewish defenders went home and only a few members remained on guard.

However, on Monday, November 14th, 1918, to the Jewish surprise, they found out that Polish demobilized soldiers and peasants had gathered at the riding school hall and were getting ready to march to the Jewish streets and pilfer Jewish stores. The Jewish guards were not visible in the streets, wanting to avoid provocation, but the members were ready in case they were needed, to join the Polish militia. The rioters had marched into the city until they reached the central square. Then, suddenly, the Polish militia disappeared to avoid disturbing the rioters in their destructive work of pilfering Jewish property.

The situation became very serious because it was impossible to gather immediately the defenders and the few that were on guard could not possibly have stopped the mob of robbers. The commander of the self-defence suggested taking up positions on the roofs and open fire on the mob and chased them out from the city. Some had suggested, in spite being a small number, to attack the mob head on and burst into the streets to defend the Jewish residents. (This suggestion was supported by the young son of Dr. Lanes, the grandson of David Tenenbaum). Tzvi Ramer, however, decided on his own to break through via alleys with a rifle in his hand, to reach the military barracks and alarm the military authority and ask for help. The defenders had anxiously waited for Ramers' return. In the meantime, the danger had increased because information had reached the defenders that a few stores had already been broken into and pilfered. Therefore, they decided not to wait any longer but to attack the rioters. In order to find a better position, a group of defenders jumped across Getzel Druker Street and reached Gedalyah Engelberg's street. In the absence of commander Ramer, they selected someone else. I remember how one of the defenders, a Hasidic young man called Joshua Fenig, turned to another Hasidic man that was standing nearby and yelled out to him: “Reb Arish (Kestenbaum) – take over the command!”

In the meantime, more defenders had arrived and their numbers had increased. It was decided to attack. In a wide human chain and with the battle cry “Hurray”, the defenders burst out into the square which was filled with soldiers and peasants. Reaching the square, one of the defenders, Nathan Marder, shot into the air. A panic broke out among the peasants and they began running in every direction while screaming: “The Jews are shooting”. The street was opened to the Jewish stores of which a few had already been pilfered. With bayoneted rifles in their hands, the defenders managed to save a lot of Jewish property.

In view of these events, it has to be pointed out about the brave behaviour of a Polish officer, Dr. Lach, who stood up against the rioters and tried to stop them with reproachful words and shaming them. Seeing that this did not help, he joined the Jewish defenders and, in a way, became their commander, continuing to clear the robbers from the city streets.

However, the anti-Semitic intriguers did not rest. They kept enticing the rioters. The mob again began approaching the positions of the Jewish defenders. When one of the leaders of the rioters attempted to attack a defender, the older son Ephraim Asher Kaner, of blessed memory, the Polish officer, Dr. Lach, threatened him that if he took one more step forward, he would shoot him.

Although the peasants had panicked and the robbery was stopped, it was only for a short while. The demobilized Polish soldiers, who were among the peasants, had renewed the robbing of the stores. A horse-ridden Polish officer appeared in the middle of the crowd. He was satisfied with the greetings of his Polish brothers and disappeared. The guards of Count Potocki could not help either. Remer's return with a military unit did scare the rioters away but they continued their dirty work because the Polish solders were not ready to protect the Jews.

The battalion officer demanded the defenders to disarm and return to their homes declaring that he would restore order only under this condition. The self-defence members were facing a dilemma. They found themselves between rioters, partially armed and a regular military unit who could disarm the Jews by force. Having no choice, they decided to rely on the righteousness of the Polish officer and handed them the rifles.

The officer did not keep his word and did nothing to stop the rioters from pilfering the stores. It was only by the intervention of a few respectable Polish citizens at the office of Marshall law in the city that helped. A few Polish merchants' owners of stores in the city who were afraid for their stores, joined the intervention. Their argument was that the robbers had already enough Jewish property and, therefore, should go home. The military then stopped the robbing after they shot a few salvos into the air. This was enough to chase the rioters away and stop the stealing and robbing of Jewish property.[1]

The leaders of the Jewish self-defence did not trust the local Polish Army. After handing over their arms, a meeting was called that evening at Beit Hamidrash with the participation of Henrik Oster, Tzvi Remer, Aaron Kestenbaum, Joshua Kesten and Yaacov Fast. It was decided to reorganize the Jewish self-defence in Lancut.

Luckily, on Tuesday November 15, 1918, a battalion of military policemen arrived from Krakow, that guarded the city and did not allow the peasants from nearby villages to enter the city. Step-by-step, the situation subsided. The Polish authorities and leader of the city became stronger and new means were adopted to observe the law and order in the city. But it took a long time until the Lancut Jews recovered from the nightmare of the days of awe that they had experienced during the revival of Poland.

[Pages 143-146]

by Anshel Katz

Part One. The doers and their deeds.

The nights of our ancestors were not like our nights. Our nights were not created for sleeping and not for studying but for wandering, sleeplessness and thoughts. With the travail and depression in the heart, one question is gnawing and prevents eye shutting: Why is the house of Israel constantly beaten? Of course, there is a leader in the Capital. Of course, his eyes are upon every human being. If this is true, what has the Polish Jewry sinned, the righteous, which are the foundation of universe and the humble of the world, that an edict was issued to be annihilated? The entire race! Why such great wrath?

During the nights, on my bed, a vision comes to my heart of those that were annihilated, most of the inhabitants of the little shtetlach; but they were doers of big deeds. One by one, the shtetlach with their residents, the community and the individuals pass before my eyes, they with their lives. The love of the Torah that was in their hearts and the good deeds on their hands. Events, which will soon be forgotten when the survivors' lives that witnessed with their own eyes, will end and it will be considered as a legend. The school books will tell a story which will begin with: “Once, there was a man”. And fathers will tell stories to their children: “Once upon a time”.

* * *

Studying the Torah in the shtetl always came first. There were charitable societies like: “Lodging for indigent from out of town”, “Visit the sick”, “Financial help for the indigent from out of town”, “Support for the locally poor”, “Free Loan Society”, “Talmud Torah” to educate poor children and orphans whose parents could not afford to pay. Every group had its task with outmoded by-laws, more than 200 years old, or more, which the Rabbis and public activists kept adding to for the sake of stability. Over all, there was the sparkling crown of the Torah. We are not talking about Yeshiva students, or about simple, lovely young men to whom dwelling in the Beit Hamidrash was their splendour and studying the Torah was their profession. But we mean the merchant, the shoe repair man, the tailor, cabinetmaker, baker and sheet metal worker. Every Jew who carried the yoke of making a living, knew that all the wealth and prosperity are subordinate in comparison to the magnificent crown called “Torah”. The chairman of the community and the simple home owner, knew that their fame was not complete nor the chair upon which they sat was wholesome until the Torah had bestowed her nobility, glory and honour upon them.

The Sabbaths were for rest but there was no complete rest without Torah. Winter time before daybreak, summer time after the midday meal, the children of Israel gathered in the house of God and listened to Reb Wolf Klaristenfeld who enlightened them in “Or Hachaim”. The house was overfilled. Some perspired from the crowdedness and some derived pleasure from the teacher's description of redemption from the hope of better days that their hears were inspired.

After a few passing hours of lush pleasantness, people became tired from sitting or standing. At that time, Shmeril the sexton, produced tea cups which he always used in the morning for early arrivals in the Beit Hamidrash. The tea intermission occurred between the chapters. In the meantime, Yankel the baker came jumping onto a table and called Joshua, the shoe repair man, to bring the hot tea kettle with tea that he had kept in the oven, to do the mitzvah of supporting those that were immersed in Torah studying. In his silk overcoat pockets, he had little bags of sugar and whilst holding the tea kettle, he poured tea for the flock who continued to enjoy the teachings.

The” Mizrachi” members were envious and had asked the chairman to honour the magnificent Kloiz from the “Mizrachi” with teaching the Five Books of Moses with the commentary of Eben Ezra. When the new spread, the Kloiz filled up on Shabbath “Breyshit” when the studying had begun. There were all kinds of listeners, old Mizrachi members, young Mizrachi members, “Hashomer Hadati” members and plain Zionists and intellectuals. They all came to demonstrate their knowledge and learn some more secrets of the book.

And this study continued for many years, every Friday night and on Sabbath afternoons. They studied the “Ethics of our Fathers” with the commentary of the “Ramba'm” and the “Eight Chapters”.

* * *

“The meaning of the proverbial saying: “That a person is credited with the mitzvah only if he completed the deed from the beginning to the end” is addressed to those who participate in the studies summer and winter and does not miss even one lecture. My friend, do no think that I have said the above to please the teacher, not so whatsoever. What I recommend is for your own good. As a metaphor, compared to our teacher, I will tell you a story. A merchant came to a fair loaded with packages and cases filled with “Merchandise”. When many customers started to arrive, he opened the cases and unwrapped the packages to display his ware to the customers. But when the fair was poor, with a few customers only, he left the cases intact and the packages unwrapped and only displayed a little bit of his merchandise.

The words penetrated into the heart and influenced the listeners. When the time of studying arrived, the store keepers left their stores to be watched by family members, the craftsmen put away their tools to the responsibility of their apprentices and everybody came to absorb the teachings of the Torah.

* * *

At dusk in the month of May, a light drizzly rain hit the dust. The air was filled with the fragrance of lilac and the entire universe was permeated with the fragrances of spring flowers. Along the avenue, between the rows of green trees, gentile daughters, light-haired peasant women with heads covered and multi-coloured head scarves, were returning from church. They marched in groups on the road leading to the Sonini village. Let everyone follow in his God's way. Reb Eliyahu Popiol, the milkman, was on his way back from milking the cows in the cowshed of Count Potocki. With milk cans on his shoulders and his son at his side assisting, it was Sunday when the studies between Mincha and Maariv usually began a little earlier. He wasn't too careful, took bigger steps. He strained his eyes to see if the people at the Kloiz were still outside sitting on benches, as they usually did. He was resigned that he would be late from the “Kedusha”. But his conscience bothered him: “Will I be on time at least for the studies?”

In a hurry while drops of sweat were dripping from his forehead, he entered the Kloiz pushing his way to the place where he always sat and saw that the teacher was already circling around in between the tables. The Teacher was explaining a chapter from the tractate: “Kilayim”. From his seat, the teacher addressed the listeners and explains to them the complicated problems according to the “Bartenura” comments, and everyone was absorbing the lecture according to his own ability to understand.

* * *

There were lights of the teachings in the shtetlach that clung to sanctity and purity. Whenever you came to Pszeworsk, Rzeszow, Dembice or Tarnow on business, and as soon as you entered the Beit Hamidrash at Mincha time, you noticed right away that the “Mishnayot” books with yellow and torn pages were open on tables and you could hear the familiar melodic intonations and feel the same warm atmosphere as though you had never left home and you never wandered away. The continuity from yesterday, the problems and the ways were familiar to you exactly as if they were in the city of your residence.

* * *

The departed, and those that are still around, might feel embarrassed hearing the above-mentioned charity societies that were managed by chairmen and committees without any reward. The head of the gentile district rule, a wicked man who began introducing Hitler's teachings in Poland, could not understand why committee members of the “Tomchey Aniyim” (support to the poor) society would run around throughout the city during freezing weather (-30° winter 1929) distributing coal to the poor which they collected with great hardship. What warms them and what kind of pleasure do they derive from such activity?

How, he continued to argue with the “Rabbi” who was the bookkeeper of the society, do the Jewish teachers teach children free of charge? Of course, the Pole grinned under his moustache that they were probably paid from the interest on loans given to members, funds that had disappeared from the books. (The yearly budget of the society at that time was 40,000 zlotys).

There is no interest and no pay here, argued the defender. We have been obliged to help the poor. Jewish people need spiritual consolation and material assistance for their business. My heart yearns to help. However, like a single tree cannot burn, a single hand cannot help. I give for the benefit of my soul and satisfaction. The defender of the society was not acquitted, not until every single member and the loaners were summoned and interrogated having being accused of collecting excessive interest which they charged when approving a loan, until they unanimously testified that they had never charged interest.

* * *

This charity work was sacred and was not done to gain prestige or respect, but God had rewarded them and protected them from illness in order to have the energy and be able to continue doing their charitable work with double the energy and devotion.

* * *

The livelihood of the city residents was a downturn. Business owners and craftsmen were distraught and poverty had spread throughout the land. The wretched had wandered off to other cities, opening their hands to beg for alms. Among the poor, were people of good parentage, wearers of worn- out silk overcoats and plain, poor people that had travelled in groups. Local teachers and shoe repairmen offered them lodging when they came to town. Sometimes, a “preacher” came and woke up the hearts of those he preached to, but Shlomo, the shoe repairman realized that such a “Leviatan” would be offered lodging by the wealthier people that would get a hold of him first, so he invited a lesser famous homilist. Rabbi, he told him: “I will make you a pair of glistening new shoes”. Thanks to the shoe repair man, the entire town enjoyed the homilist preaching and his sweet talk. The listeners enjoyed it so much that they carried him on their hands.

* * *

Sometimes a person dreads to look at his wound. These people were pious, doing good deeds, but God had not opened their eyes to foresee that their fate was sealed. The good and the righteous among them have attempted to redeem the Divine from exile but did not try to redeem themselves, clinging to the point of view that if “He”, (Divinity) will be redeemed, His sons will also be redeemed. But “He” came first. But how can I get consolation? They knew and understood. The righteous among them foresaw and wrote and learned about it: “Their ankles will sink in blood before the big and awful day will come”. They expected the redemption any day and believed that with the redemption of the Divinity, they too would be redeemed. Will God forget them? Will He abandon them forever?

* * *

Hashem wanted oppression. Of course, there is a leader in the Capitol. Of course, his eyes are open upon every creature. If so, what has the righteous, the fundamental element of the world and the humble of the world sinned? Why such big wrath?

Part Two. A remembrance for Sunday.

When the wheel rolls like a waveThe child grew up and became a man and wound up in another place. A residential charming place with proper lineage. This was Lancut and her Jews. The city people were not climbing high into the skies, nor were they any outstanding geniuses. They were simple, mediocre, not distinguished richly and not depressively poor. They were casual merchants and permanent Torah students. They consumed food in this world but lived for the world to come. Still, the people of Lancut were known all over Galicia to be of better lineage. It was influenced by the “Little Lublin Synagogue” in Lancut, forever remembered (until the world disorder came) since Reb Itzikel, who later became the “Seer” of Lublin, resided in the city and left memories which were passed from fathers to sons, about his deeds and solitude during the entire time of his residence in Lancut. His pupil, Tzadik from Ropczyce, came to town to seek his advice of tremendous importance to Hassidism. This great pupil was enchanted with the smell of the city and expressed his surprise that his Hasidim did not feel the good fragrance which the city was blessed with? When his time came to depart from this world, he asked to be taken to Lancut, to a medical specialist who worked in a military hospital, but he passed away before reaching Lancut. He was allocated a splendid burial place in the middle of the city. It was on a hillock, located at the “foothills of the Carpathian Mountains”. Thousands of people en mass came to visit the grave site of this wise Tzadik.

To change the system

Your friendly lover

Turned to you and said: “Look!”(a song poem for the ten days of repentance).

And there was the Count Potocki and his palace with fancy coaches that were hitched to four horses and his adjutant sat in the back up high with a long trumpet, announcing him with a song with which big people were welcomed. The Count, with his unit of cavalry, used to come out on festive occasions in festive attires, and the echoes of his orchestra was heard in the streets and market places, which rose the youngsters on to their feet to run after them until they reached the church. This was also the pride of the city's residents.

The good Jews, as they were not tied up with the vanities of this world, it, therefore, was easy for them when the days of awe were approaching, to devote themselves to goodness. The first day of the year came to an end. Through the windows of the Beit Hamidrash, the glimmers of the dusk and redness of the skies penetrated. The services ended at four and after a quick meal as who would dare to indulge on judgement day? They were already standing again in God's house and praying the Mincha service.

The Talmudic books were coming out from the cabinets. The “Shabbath Goy” (in a few years, he was a guide of the Gestapo to Jewish hiding places, the ones he made a living from) turned on the lights. In the bright light, all the tables were full with Talmudic books, books of ritual questions and answers, Midrashim, Ayin Yaacovs and Hasidic books. Around the books, people wearing silk overcoats and “Shraymlech”, were crowding and explaining to one another, discussing and interrupting each other.

A father was studying with his son and a son studied with his father. Reb Chaim, the son of Yeshayahu, had a prodigy son. In honour of the holiday, he explained to his father a complicated commentary in the “Yevamot” tractate. Reb Baruch Goldman, whose son headed many Yeshivot, were both sweating over an engineering problem in the “Eyruvin” tractates which made father proud of his son for many reasons. Yanchi Peterzeil had two good grandsons. One was studying with him and the older grandson was studying with his father, Reb Wolf Klaristenfeld, of which almost every Jew in the shtetl was his pupil, with whom he studied the “Or Hachaim” on the Sabbaths winter mornings and summer afternoons. His son, who had been married for a long time, needed his help in the Talmud. The father pitifully helped him out with a few innovations which many of his teachers had tried to teach him when he was younger, without success. Moshele Kraut had explained the book of “Shlah”. The glare of the book radiated his face and he was filled with joy. Shlomo Wanger was teaching those who stood around him the “Ayin Yaacov”. Two young men, steady Beit Hamidrash dwellers, had, with iron clad determination, argued a certain paragraph in the “Turey Even” and were swarming with lots of questions without answers.

The house was filled with cigarette smoke. Everyone was talking; the explainer and explained, the lecturer and the receiver, the student and the teacher, all with some kind of a melody and intonation. A stranger would not understand what was going on. They were not Rabbis or Judges. They were just studying the Torah – continuing a tradition. They were not lawyers who studied the law but the people were a part of a chain of many generations. The Jewish People who had received the Torah on Mount Sinai, were teaching their sons, and the sons taught their sons what they had learned from their fathers in order that the last generation should not forget the amusing teachings and its precepts.

The long clock that hung between two windows rang out the 9th hour. Shmeril lit the candles, Rabbi Elazar Spiro had arrived and with him arrived tremor and jitter. Gladness and angst were on his face which he had inherited from his ancestors. The High Holiday melodies were received on Mount Sinai and the intonation of every supplication had penetrated the heavenly chambers. During the Musaf prayer of that day, he demanded mercy and his pleas overfilled the heart:

“Therefore, the memory should appear before you to multiply his offspring like the dust of the earth, and your descendants like the sands of seashores”.It was the customary melody that his ancestors had composed for the above words. It came out “rounded” which instilled hope and confidence, as it was during the days of his grandfather, of blessed memory, and he clearly knew that he succeeded to please the Creator.(Quotation from High Holiday prayer).

Shmeril knocked three times on the table. This was the signal that it was time for the Maariv services. The sea has relaxed, its stormy noise has subsided and the waves move quietly. It wasn't a pain-filled house. The strong arm of their Rabbi was their leader. They could rely on him just as his ancestors had led them. These worldly Tzadikim knew how to appeal to their Creator for the sake of their ancestors. When the Rabbi pronounced the verse: “The entire world belongs to you; including the inhabitants!” It was exactly as his grandfather had done.

On the eve of 1940

I strained my ears – a deadly silence, no preparing for the Judgement Day and no trembling for the forthcoming. God's house – the windows and doors were gone. Scary huge holes imposed terror. The roads were destroyed and visitors were gone. Mothers with their children had perished. The Rabbi, with his community and the sexton, were judged. The books with the students were annihilated.

And what am I?

God, the soul that you implanted in me is pure even though my soul is not the same soul of Rabbi Levi Yitzhak from Berditchev. If a soul had been implanted in me like his, I would have wrapped myself in the prayer shawl and would have asked: “Ruler of the universe! What have you done? You have done more damage to yourself than you have done to us. Who will anoint you to be King? Who will entertain you? Who will tell about you to the next generation? Who will spread your truthful words? Who will continue? And what is the use of continuity? When the well of purification has gone. If you will dwell deeply in justice, who will find you innocent?” Who?

Part Three. No breakthrough.

|

|

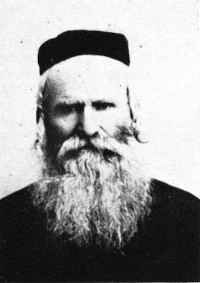

| Yitzhak Shayes |

To come early in Beit Hamidrash on Sabbath Eve for Mincha services was one of my Shabbath pleasures. Friday, before sunset, a strong and wintery wind had dried the mud puddles and had formed a dry path that could enable us to make a shortcut, to walk from the other side of the wood marketplace and reach the Beit Hamidrash.

Regular market days in Lancut were on Friday. During the day, great dealings took place, tumultuous, gentiles and loud horses everywhere. Calves and pigs had felt that they were being bought and sold to become a festive meal by the owners. Dealings and selling, negotiations, hovered in the air. The vodka warmed and radiated the faces and improved the urge to buy and sell.

The sounds of holiness had penetrated into the shtetl from the quiet alleys and closed shutters. Profanity was chased out; the market place was empty and all the dirt that the horses had left was swept away by the wind. Flying pieces of paper and other trash were chasing each other in the wind. The last horse and buggy passed by the Beit Hamidrash where the huge windows were already brightly illuminated. The bright light from the interior had imposed twilight awe on the incidental passer-by. Evening silhouettes swallowed the sound of the whip of a belated coachman who hurriedly passed by. A late drunk leaned against the wall of God's house. From a distance, a pig was screaming as it was being pulled by the owner on the path leading to Sonuno Village. The separation between the weekday hustle and bustle and the Sabbath holiness was felt when approaching the Beit Hamidrash, and one could hear and your soul could enjoy the voice of Reb Itche Shayes, who was reciting a laud: the Psalm “Ledavid Baruch Hashem”.

He was a man in his 70's but his voice was still thin and the melody was beset with fragrance of the Shabbath and with the soul from the Tzadik from Dynow who received his inspiration from Rabbi Mendele from Rymanow, may he rest in peace. From them, Reb Itche adopted the custom of reciting the above-mentioned Psalm on Friday after sunset at the start of the Sabbath at Mincha time before Ashrey.

The market day, the vanity of bathing in the community bathhouse made many people late. The agile were already there. Shmeril the sexton paced up and down the sanctuary while others were busy with weekday problems, he stuck to his sacred work. He cleaned the floor, square-by-square and now he enjoyed the results of his job. In the meantime, Reb Itche had finished the chapter with his pleading voice. There were no outburst and no screaming in our streets, only the loud recitation of Ashrey had begun.

Who understood then the loud shouting? What a sad but sweet depression had penetrated into the heart, caressed and spoke with a vision to the soul? Exile after exile, the entire city expelled.

When Hitler's soldiers came to town, all the Jews except the older people aged 80 and older, were expelled across the river San, which at that time, was the border between the Germans and the Soviets. They were turned into wanderers in a foreign land. The people could not see their birthplace but they remained nearby. They hoped, when things would quieten down and wickedness would disappear from the world, that they then would cross back and return to breathe the air of their shtetl.

The Soviets, however, had smelt the smell of war with Germany, had given the border functionaries an order to gather all the expelled people and transfer them to Lwow. From there, the entire community was made to wander to Siberia. Starvation reigned in Siberia which was by the cold weather. Suddenly, the expelled people received tidings that there was food in Samarkand. Young and old streamed to that place. Unfortunately, the big city had become the grave site of the natives of our shtetl. Many died of typhus, among them Reb Itche Shayes, the man that sang songs to honour his creator with the voice of his throat.

As to how the Lancut exiles fared, we found out from their orphans, of which a few of them had merited to emigrate to Israel with some children transport via Teheran. It was rumoured that after the expulsion, many individuals, mainly women had returned to Lancut. Some pretended to be non-Jews and some smuggled through the border. The hand of the enemy had reached them and cut their lives short. Days later, the good healthy women were sent to work in the ghetto and the rest were either shot or burnt n the crematoriums. On a cloudy day, all the sick, the old, the children and the rest of the community were taken to the woods of Pelkinia and slaughtered.

On Sabbath nights, if you hear the echo of my painful pacing in the room, you should know that my heart explodes from the silence that reaches me from my afflicted shtetl. No outburst nor shriek is heard in our streets.

[Pages 147-148]

by Zalman Dembitzer

Translated by Nathan Kudish

The writer and poet, Zalman Dembitzer was born in Lancut in 1888. At the age of fifteen, he left the shtetl and came back in 1909. His books: “Narrow Streets”, (published in August 1914) “About Love” (1920) are based on memories from his birthplace and its people. His impression of the scenery and the society from days past, he used as the background of his love and experience in his stories from his youthful period in Lancut. He published poetry in Yiddish with Latin letters. “Sound of Life”, “Lost Worlds”, “Black Leaves”. His poems as a young man stand out because of their deep lyrics, immersed in sorrow and sadness, interwoven with dreams and visions of a creative imagination. We bring here a chapter from his book: “Narrow Streets”, “The visit in Lancut”.And I felt again in me the hidden push and craving to see the city where I was born. My heart has pulled me to that place where I sent my youthful years, where I visualized in the bluish summer nights, sights which I will never forget.

My shtetl, my birthplace! Whom did I leave there? Only the grave sites of my romances. Nevertheless, a man's heart years to return to the place where he dreamed his dreams during his Genesis. I took my ancient wander staff and my knapsack and hit the road.

I listened to my heart and with heavy steps, I moved toward my shtetl, my birthplace. If you came across a pale-face lad who strung his way along desolated paths and, in his eyes, there were remnants of a glow, you should have known that it was I, who was . . .

Gloomy and ugly was the evening of my arrival in Lancut, the shtetl of my youth. The world had become sad over me when my spirit became gloomy. My soul wanted to fall asleep forever. The first to greet me with a “Shalom Aleychem” was my old friend Yoshi Meier. He took me around the town and told me the latest “news”. He did not stop talking.

The evening became gloomier and uglier. We circled around the market place and went to the small, silent and narrow alleys. Intermittently, we started a conversation and stopped immediately. We both continued to be immersed in our thoughts. Zalman' You didn't recognize Moyshele? Here he is! Where? Over there – Moyshele, come over here. In front of me that was a young lad, a “Hassid” who held out his hand to greet me with a “Shalom Aleychem”. “How are you? They say that you are a famous person, a poet? Are you writing books? Is there a possibility that you will soon be a doctor?” “Possibly”. “They say that the Kaiser likes you. Listen, maybe you can talk to him about being good to the Jews?”

We strolled in the direction of the Beit Hamidrash. The storekeepers had closed the stores, darkness had spread throughout the city and in the deafening silence, our steps could be heard. We did not converse. We were both immersed each in our own world.

Thoughts came and went. Memories from the past that were long forgotten, resurrected and my life weighed heavily like lead. Then, a summer night came to my mind. The skies were filled with starts and a light, cool summer breeze blew in the shtetl and in a lovely way, caressed the residents sitting on the stoops of their low houses with rolled up sleeves. On the other side of the road, humble young girls strolled at a slow pace with their deep dark eyes and bashful smile which hovered on their lips. A young Yeshiva lad passed them by, their eyes met but he rapidly slipped away while his heart had increased its beat. My happy shtetl.

It seemed that the stars in the skies had become bigger, brighter and better shining. Where is the artist who could record these moments with his paint brush? The entire shtetl was like a blossoming garden, multi-coloured and the people were like sprouting flowers that grew in bunches. The hot air had revived and caressed by heart.

Itzik, come home! It is time to sleep! A sudden call was heard which disturbed the silence in the square and disrupted the stillness of the dreams.

We entered the Beit Hamidrash. It looked empty but, in a corner, near the oven, an old man sat and by the light of a waxen candle, he was bent over the pages of a Talmudic tractate. On the table there were many books laying in a disorderly manner. On the pulpit, a candle for a dead soul was burning and around it, little flickering lights were jumping slowly. The quietness had imposed fear. From time-to-time, coughing was heard from the old man which interrupted the silence in the Beit Hamidrash.

Where are my friends? Where are the Beit Hamidrash dwellers that use to study here and hummed a trilling, heightened melody and the sorrowful sounds that hovered over the Talmudic pages? Oh, how pure and radiant was their song? Zalman, when you grow up, you will be a Rabbi, a genius! Mothers will be asking for your blessings. Torah scholars will see his council. Your name will be famous throughout the entire world. Dreams! Dreams! False dreams!

These were the thoughts that assaulted me and drilled my brains, awaking memories from my youth, but I strenuously wanted to return to reality.

“Moyshele! How are my friends from those days? What are they doing now?” “What should they do?” We became quiet. “Do you remember Srulik the fool? He is married and has a family. Shmuel the middleman was inducted into the army”.

All three of us approached the pulpit. Moyshele leaned on it and continued to chatter. “You remember Yoshi? Do you know that he is a great scholar now? He reads the newspaper “Di Tzeit” and is considered an intellectual. And Alter? Alter is doing nothing. He is an idler, browses around the market square with his hands in his pockets”.

“The second Moshe? He is a scholar. He has a head of a minister. He is very talented in painting curling lines that causes amazement. He also knows to write legal papers like a lawyer! He is already receiving matrimonial proposals”.

Suddenly, Yoshi Meir interrupted his tales and turned to me with a question: “Would you like to see Tzipora? Maybe you would like to know about the mischievous tricks of the shtetl's strong man?”

In my shtetl, like in many other shtetls in Galicia, there was always a “bully”, a mischievous man. His name was Chaim and his wife's name was Esther. He was obese with a red face and she was lean and slim. When he said that it was day, she always contradicted him and said, night! There was a steady squabble going on between them and they took the arguments out into the street. His status was the status of a city ruler and his opinion was counted in the “Burial Society” and in the community. However, in case he demanded a high burial fee from a poor deceased, people turned to his wife for intervention. It was enough for her to take a whip in her hand and say: “Chaim! Do you see the whim?” and that was enough. He immediately ran out of the house to the market square and yelled: “Let he go to hell. I don't want any money. Let the deceased be buried for free but don't let her know about it”. He was proud to be called “mischievous” for a different reason. He saw himself as a noble man who boasted with his status on every occasion. He did not consider proper to start a conversation with some “beggar” in public.

I had no idea how it happened. Suddenly, I found myself in a bed covered with a white sheet and in a situation of being unable to fall asleep. I rubbed my eyes and chased away dreams. Slowly, my consciousness cleared and I opened the window. A cool, morning breeze penetrated into the room and cooled my refreshed and tired head from sleeping. Daybreak had come and the city was wrapped in a heavy fog which blurred the sleepy little houses. Deep silence oppressed the shtetl like on a cemetery.

Suddenly, voices reached my ears and I wanted to shout loudly to the walking corpses: “let me sleep!” Let the people who don't crave to live and lack the gladness of living, rest. Let the young people, the weak, the naïve small-chested with the long ear locks, rest. Oh, how guiltless their eyes are which are begging mercy and craving to escape suffocation before their glow fades. Let the daughters of Israel, the young and the humble with their black, long braids and scared, bashful faces, who dare only to dream about the young boys but would not dare to send longing glances in their direction, being afraid of being caught in their mischief.

The morning fog faded away, the skies cleared and the light wind snuck away between the branches of trees.

Echoes of steps were heard in the alleys. People were rushing to the morning services to thank the master of the universe for his kindness.

The door suddenly opened. Yoshi Meir, my friend, entered my room, breathlessly and excited and told me that the town bully was vigorously swearing! “We planned for you to give a lecture in the “Zionist Association” club about Zionism. The “bully” took the keys to the society club away, claiming that he does not want you corrupting the city people”.

It was not easy for me to calm my friend down. After he did calm down, he lit a cigarette, leaned against the table and blew smoke all over the room. A few minutes later, he sat down and asked me when I was planning to leave. “As soon as possible”, I responded. “Will you write sometimes?” “Of course”. “If so, be well and have a happy voyage.

[Pages 148-151]

by Michael Walzer

In the summer of 1937, after eight years in Eretz Israel, I went to visit my shtetl, my birthplace, Lancut. I was flooded with emotions. I recalled the riots of 1929 when I left my shtetl to emigrate to Eretz Israel. There were also riots in 1937. The Arab terror continued. The tension and the severe rumours had imposed upon the “Yishuv”, special gloomy moodiness.

On the other hand, I had also the emotions of a man who was returning to visit his parents” home, the place where I was born and raised, to his friends, to the life of “small” people, the way I saw them then, like it happened many generations ago. When the train approached Lancut, I became immersed in my thoughts. The screeching of the train wheels passing the fields of Poland, took me back for a moment to the peasant, the farmer and the fields of Sharon from where I had come from. I knew that I was coming to the town that is disconnected from the main pulse of national life – a city that lives with the Diaspora illusion but still, I loved everyone in that city. Every Jewish person in the shtetl was close and dear to my heart. During my travel in the train, I witnessed the miserable state of our Jewish brothers in Poland. The anti-Semitic plague that had destroyed their status and denigrated the honour of the Polish Jewry, was bluntly visible.

I met a man on the train in which I travelled, an intellectual man which the expression on his face testified of his understanding and suffering. He spoke fluent Polish. On the train with us there was a railroad policeman and a priest, each of them was immersed in their own thoughts, but as soon as two students noisily entered, they immediately, without any ado, demanded from the man “to clear his seat” for them. He responded that there were enough seats for everyone, but they insisted: “we don't want to sit on the same bench with a Jew”. I was stunned from the rough reality and the impudence of anti-Semitism which I had encountered face-to-face. Outside, in the passageway, there were many more Jews standing near the glass door, but they immediately left when they saw this anti-Semitic outburst. However, the Jewish intellectual from Lodz did not flinch and attempted to defend his honour.

When I noticed what was taking place, I turned to the priest who sat in the compartment and said: “Take a look at your flock, how they are behaving”. But the priest remained quiet with no reaction whatsoever. I turned directly to the students and tried to explain and convince them with words, but they warned me that they would break my head if I got involved. I turned to the railroad policeman and pulled out my British passport from my pocket. This immediately helped. The policeman intervened and threatened the students that they should quietly sit down.

The Jewish man told me that in the future, he would not stand up again against the ruffians because it did not make sense. He was particularly angry at the Jews that were standing outside the compartment and did not attempt to get involved but left. “I will behave like the rest of the Jews who are afraid”.

That is how I tasted anti-Semitism during my arrival in Poland on my way to my city in 1937. Visiting Lancut, I saw how anti-Semitism was running wild on every step and place, like for instance: Jews were not allowed to use the municipal swimming poor near the military barracks for simple anti-Semitic reasons. The Jews simply accepted this and went swimming in the Wisloka River.

There was segregation between Jews and non-Jews in every venue of their lives, not withstanding the fact, however, that Jews kept doing business with them. Actually, the Jews themselves did not like to use their facilities, especially facilities that the Jews also had.

When I disembarked from the train, I decided to walk to my parent's house. I didn't let them know that I was coming and I thought that walking home would give a chance to walk through my beloved streets and alleys and later drop in as an unexpected guest. My luggage I had sent home with a Jewish coachman. However, I was forced, after all, to take a coach because several friends had seen me arriving at the train station and they had offered me a ride home.

The Jewish coachman, on his way to the city, had spread the “news” about my arrival and when I reached my home in the market square, the secret of my arrival was known to everyone, and many had already gathered near my parents' two-story house. This happened at dusk on a hot and dry day in June. I found my parents in the hardware store My brother, Shimon, who was ten years old when I left him, was now an 18-year-old young man. I was happy with my parents and appreciate all those that came to greet me. However, I did ask everyone to give a chance to rest, promising that “We will meet again and will talk some more”. I went up to the second floor of our house and spread out onto the bed of my parent's home, in the poor Jewish shtetl, and the entire affair felt like a dream.

During the few weeks that I stayed in town, I had the chance not only to breathe the air of the Polish summer, and the emotion of seeing my father, mother, relatives and friends, but I also had a chance to live a little in the Zionist atmosphere of the youth in the Diaspora. The youths with whom I grew up, learned and dreamed together. I was invited to many events and meetings of institutions and different organizations, and participated in them as much as I could.

I tracked down the process of the isolation of the Polish Jewry, after they were removed from the economy because of anti-Semitism. Within this setting, I had several meetings with city gentiles. I repeatedly asked them the eternal question. Why is there such a hostility toward the Jews? They responded directly and without hesitation. What can we do? The general economic situation is bad. The Polish people are suffering. Isn't it logic to remove the Jews from the economy and commerce and bring the Poles, the inhabitants of the land instead? They say the Jews as strangers in their land, ignoring the fact that the Jews had lived in Poland for hundreds of years. That is why, in their opinion, the Jews should leave Poland. Regrettably, the Jews did not understand the situation and did not draw the consequences of this situation. They suffered silently, sighed, collapsed under the heavy yoke of taxation and could not help themselves. “A prisoner is not being in the habit of freeing himself from prison”.

My knowledge in farming, my contact with the earth and my expertise in matters of rain, raised amazement among my friends in town. In their eyes, I had become a specialist, a star seer and constellation. I became a man who knew the difference between a simple cloud and clouds that would bring the blessing of rain. During my stay in town, it was a time of rain expectation as there was a drought. The grains in the fields had become yellow prematurely. The peasants looked up to the heaven and prayed for rain. The Jews also felt the draught because the peasants were sad and broke. They did not sell or buy anything.

And low and behold! Once, on the way with my friends to swim in the Wisloka River, and enjoy the cool air, I suddenly detected, on the edge of the skies, clouds that every peasant in our country knew and that carried with them rain. I remarked to my friends that it would be raining soon and we had better get dressed and return to the city. They laughed at me and said: “Such clouds pass here daily but they don't bring rain”. I did not listen to them. I got dressed and left for the city by myself. When I arrived in the coffee house where we always met, heavy grey clouds had covered the skies, and an angry rainstorm came down to earth. The people stood in the doors of their stores with thankful eyes heavenward. The bathers became soaked down to their bones.

The severe economic situation and the depression of the Lancut Jews had left me with a heavy impression to this day. I went to visit David Yust and conveyed regards from his daughter, Peninah, in Eretz Israel. Mr. Yust was a man who was experiencing suffering and hardships. I felt close to him particularly because during my childhood, I often visited his home and was friendly with his daughter Esther and his two sons, Naphtali and Israel. They were the same age as I.

I was stunned when I came into the of Mr. Yust seeing that the door in his watch-repair store did not close for a minute. There was a constant stream of beggars who came, asking for alms. Mr. Yust was extraordinarily patient with the poor and kept handing out pennies to each person. I knew that his economic situation was not to be envied and that from the watch repairing store, he could not make a living. I asked him: “How can you tolerate the stream of the poor people and keep up giving everyone a donation?” His response was: “It is tragic, but who can give me a warranty that in one clear day, I will not be in the same position as these poor people are now and I will not be standing in a door, begging alms just as these people are doing now?”

I left the store immersed in my thoughts while in the street, there were music boxes playing by a group of poor people who were later collecting donations in return for their monotonous music tunes played by their organ.

I stood near Luxenburg's delicacy store and we conversed about Eretz Israel, about the riots and about Jewish life in Poland. With us were a few of the best young people in Lancut, students and plain folks. Among them a few who were known for their strength and courage: Leibush Shtecher, Michael and Moshe Rosmarin, Hersh Zawada, Abraham Estlein, David Trompeter and others.

At that time, two gentile boys, about 18-years old, passed by and gave me a push. Instinctively, I defended myself by pushing back and caused them both to fall to the ground. There was immediate panic on the spot and all the young Jewish people disappeared. I was left alone but I was ready to respond in kind.

Afterwards, I asked my friends why they had behaved like cowards, and they told me: “Of course we were not afraid of the two gentile boys, even if there were a few more of them. But, would you like us to provoke, here in Lancut, a second Pshitik, a pogrom on the Jews like it happened there?”

There was in Lancut a known pig merchant, a Polish butcher, Shliwinski. He was a typical “Goy” whose greatest pleasure was throwing stones in the show window of the delicacy stores located in the centre of the town and break the window panes. He enjoyed his handy work, feeling safe from being punished for it. When the brother of the store owner, Abraham Margal, approached a police office to complain, the police officer responded: “Thanks to my effort, there is no pogrom in Lancut and you are complaining?”

During my visit in Lancut, I had discovered an interesting phenomenon: The Beit Hamidrash was full of Torah studiers, young lads that sat day and night at the tables and studied with a sad intonation. The Beit Hamidrash was too small to absorb all the people and some were forced to sit in the corridors and study the Torah. The number of worshipers that worshiped in the morning and evening was also big. At the time when I left Lancut, there was an entirely different atmosphere hovering over the city. Young people turned to the big world, many went to foreign countries to study and the Beit Hamidrash was empty! At present, the situation was the opposite. Those who emigrated to Germany and other European countries had returned, depressed and insulted. The gates to every country in the world were closed and there was no escape. All what they could do was to look up to Heaven and ask for help.

I went to a party given in my honour by the “Hazamir” band. I enjoyed meeting the veterans who had invested so much energy and vision in the establishment of such a valuable musical institution. All the conductors of the past were there: Tzvi Ramer, Engineer Spatz, Moshe Feilshus and Shimon Wolkenfeld.

Of course, the subject of our conversation was the problems of the land of Israel; about the feasibility of settling in the land and about the future of the Jewish People. Many who sat there had faces that showed signs that in reality, they had run out of energy and lacked the possibility to move and begin a new life in Eretz Israel. My heart pained for the dear people that were unable to handle the problematic of their future.

I partook in a party by “Wizo” and also met with leaders of youth organizations. I paid special attention to them because the youths demonstrated their readiness to overcome the habit of doing nothing and were ready for pioneering and emigrating to Eretz Israel. Indeed, many of these youngsters did emigrate.

I visited the leaders of the youths in our city, the people whose words and inspiration made me grow up with. I met for a special conversation with engineer Spatz, the chairman of the Zionist organization in our city and who was first at every public and Zionist activity. He was the only Jew among the city leaders that, on the day of my departure, embraced me and began to cry. “Oh, how I wish that I could be with you in Eretz Israel”. He did not. He perished together with the rest of the Polish martyrs in the war of annihilation. He expired somewhere on the road of his travail. His son, an American scientist made “Aliyah” and settled in our land.

I met with Professor Ebner. He invited me to his home and asked me to tell him “Everything about Eretz Israel”. I also met Dr. Leon Markel, the chairman of the “Jewish National Fund” and Dr. Dolek Druker. They all perished wandering during the war.

Rabbi Spira invited me for a conversation: “It looks as though you have a spark of holiness the way you all-guarding the Holy Land”. “However, the problem is”, he continued, “that you are not observant”. I told him: “If the religious people would emigrate to Eretz Israel, they would influence the life in our land for more observance of the traditions of Judaism and Torah, indeed, you should do it. I had contradicted him”.

I visited the Kwiatek family, my school principal in the past in response to their invitation. Of course, we talked about Jews and anti-Semitism and I asked him: “Why do the Poles oppress the Jews in such a severe manner, especially by boycotting Jewish stores?”

“As a peasant in Eretz Israel, wouldn't you help establish your own cooperative stores to protect you from storekeepers charging the peasants exorbitant prices?” I told him that if the roads had been open to Jews in every venue of economic life, working on government jobs, it would have been different but the reality of the situation in Poland was that no Jew was being hired on a government post, not in the police, post office, literally, in no place!

I sat at a friend's store, Mr. Weinberger. Two Polish students came into the store and asked to change a five-zloty bill. The man did not have the change. He got up and went into the next store just to accommodate the two gentile young men. In the meantime, they vandalized the store, spilled ink on the table and on merchandise and when Mr. Weinberger came back, they grabbed the money and escaped.

The view of the city left me with an unforgettable impression. The market place was empty at noon time. Jewish people were moving around, searching, looking for something. It was an atmosphere like on Passover Eve. Wooden cabinets were removed from the houses and old furniture moved from house-to-house to avoid the tax collectors. Everyone had tax problems and fear had overtaken the entire city. The government tax collectors did not believe the Jewish People that business was bad. They maliciously ignored their economic situation. They used every opportunity to collect a few zlotys for the taxes which they owed to the government. They requisitioned furniture, beds, houseware and merchandise and if this did not satisfy them, they searched the pockets of the Jews which they had encountered in the street. They ordered them to raise their hands and searched their pockets. They money that was found, was confiscated, leaving only a few zlotys required by law.

A vision that I saw will never be erased from my memory. It was as follows: The street was empty and in the middle of the street, A Jewish man was standing with his arms risen and the Christian clerk was searching the victim's pockets. Frightened people were watching the scene from their doors and windows, afraid that their fate would be the same.

Here and there, you could see the Jewish “golden youth” idling as they could not get higher education in Polish schools because of being forced to sit in segregated seats.

Near Mr. Lam's store, people gathered in the evenings to listen to the radio. People strolled back and forth on the promenade called “Mokra” and analysed the news, adding their own commentaries.

Before I left Lancut, a mass meeting was arranged where the Lord Pill report was discussed on dividing Palestine. All the Jews of Lancut were present. I became emotional, witnessing the enthusiasm and the love which people had for the Land of Israel, young and old. There were speeches by Dr. Druker, engineer Spatz and of course, I also greeted the assembly.

I separated from the town people. I took my last gaze at the city where I was born and I looked at my dearest to me and boarded the train. The train wheels screeched, and in my head were still the echoes of the words of a Jewish song. “Was this my peer shtetl, was that you, or maybe I saw you only in a dream?”

|

|

| Part of the market square in Lancut, before the Holocaust |

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Łańcut, Poland

Łańcut, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 03 Nov 2022 by JH