|

|

[Page 1]

This is the story of a typical Galician shtetl, its triumphs and tribulations and its final destruction.

As it was my hometown and I was sometimes a bystander at some events and a participant in others, what happened to me gives the reader a very good idea of what happened finally to the entire Jewish population of the town.

To fully explain the context, my biography is interwoven into the complex tapestry of events that begin in the immediate pre-WWI period and does not end until the post-WWII period. It is also important to relate the fate which befell the Jewish population of some of the towns and villages in the Kuty-Kolomyja-Czernowitz triangle.

The events related here are based on the following sources:

The town of Kuty was founded by the Polish Count Potocki in 1775. In public school, during geography lessons, I learned that f rom the beginning it was inhabited by Jews and Armenians (ormiansko-zydowskie miasteczko), a small town of Jews and Armenians, although there were also Poles and Ukrainians.

The Armenians who settled in Kuty came from the Rumanian provinces of Walachia and Moldova where they had settled first, after fleeing from Turkey. As it was with other immigrants, for several generations, they still spoke Armenian. But in the 1920's, when I started school, my generation of Armenians were being polonized and none of my Armenian schoolmates could converse in their native tongue. They were even starting to polonize their names.

My maternal grandfather who, like many Jews did a lot of business with them, still knew some Armenian words and sayings. And for a number of years, we had, in Kuty, an Armenian mayor, Norcessowicz and a deputy mayor, a Jew, Mr. Israel Pistiner, both men in their seventies who when they were together, so people said, spoke Armenian to each other.

The first “Dismembering of Poland” took place in 1772. One part went to Russia, one to Prussia and one called Galicia (where Kuty is located) went to Austria (later to become Austro-Hungarian empire). The Austrian period lasted from 1772 until the end of 1918 when the rebel

[Page 3]

Polish army established a Polish government. This government lasted until September 1939, when the Red Army occupied the eastern provinces and the German army took all the west of Poland. The Soviet-German border moved west from the river Zbrucz (an affluent of the Dniester) to the river San (an affluent of the Vistula) which flows through the city of Przemysl, separating the city into two parts – one German and one Soviet.

Kuty lies in the valley of the river Czeremosz. The river flowing through Kuty is a result of the merger upstream of the White River and the Black River. From Kuty, the river flows towards the town of Sniatyn where the Czeremosz reaches the Prut, an affluent of the Danube. Kuty is composed of two main parts: an upper part and a lower part. The upper part was the main part with the marketplace as its centre. The lower part, called the Dolina, was more like a suburb and in some places, it looked more like the countryside with small buildings and houses scattered more widely than in the upper part of the town. The upper part of the town was inhabited mostly by Jews and some Poles while the Dolina was mostly Ukrainian.

At the edge of upper-Kuty was Mount Owidjusz from which one could get a wonderful view of the Dolina, the river with its beaches, the town of Wiznitz and on the far side of the river, the mountains rising in the Bucovina. Before 1914, both sides of the Czeremosz, the Galician and the Bucovinian, were Austrian. As a result, there was a free-flow of goods and people across the river and most families had some relatives “on the other side” as we called it. After 1918, the river became the border between Poland and

[Page 4]

Rumania, the free-flow of goods stopped and smuggling became a new occupation in town.

My father had one sister (my aunt Esther) in Wiznitz, and one in Czernowitz (my aunt Pesie Leah). My mother had an aunt in Czernowitz (my grandfather's sister, Chaye Syme). My father's other siblings were: my uncle Hersh in Yablonov near Kolomyja, and my uncle Simon in Montreal. My father's sister, Sara Klein-Pfau, died in an accident before I was born. She dropped a petroleum lamp in her kitchen and her clothes caught fire. She was badly burned and died leaving six small children – four boys and two girls.

Evacuation and flight through the mountains. Refugees in Kolin

My father's name was Wolf Klein (Velvel in Yiddish, Zeev in Hebrew). My parents were married in 1907 (probably) when my mother was 19 and my father was 28. My paternal grandparents were Shlomo Klein and Rachel Shamir. My maternal grandparents were Leib Kasner and Taube Gitl Fischer.

I was born on October 8th, 1914 in the town of Kuty. I was named after my maternal great-grandfather, Abraham Fischer. My first name, Abraham, is always the name used when I am called to the Torah. It is also the name that has always appeared on all my official documents. But my parents called me Bunciu at home and that is what everybody called me in Kuty.

My father had, since his youth, been involved in doing some trading with the local Ukrainian mountain people (called the Hutzuls). Both my grandfather Leib Kasner and his father Mordecai were also traders. They bought called and sold them to butchers in the town. And they also bought furs which they sold to agents of fur companies from Kolomyja who came to buy in Kuty.

In 1912, my mother had a son. My parents named him Raphael, after Rachel Shamir's father, but at home we called him Uciu.

[Page 6]

The Great War had broken out in August of 1914 and when I was born two months later, the war was already raging near the Austro-Hungarian border, only 120km from Kuty. The Russian army had attacked almost immediately and by September, the first detachments were approaching our town. The Jewish population that lived near the Russian border was well aware of the pogroms and persecutions of Jews in the Czarist empire. A general panic resulted in a flight of refugees.

My father had been mobilized just before the war broke out. Already in 1899, when my father was called up with his age group (of 21 years old) to serve in the peace-time army, my grandmother Rachel had gone to see the Wiznitzer Rebbe. She asked for his blessing and prayers so that the mobilization orders would not come for her son. The Rebbe had assured her then that her son would not have to serve in the army. And in fact, my father's military service was deferred at that time. Was it the Rebbe's intervention that helped, or was it my father's faking some deafness in his right ear? Nobody could know for sure.

So, this time too, my grandmother went to see the Rebbe. Now, once again, the Rebbe assured grandmother Rachel: “Go home and everything will be fine”. But this time, the Rebbe didn't deliver. And the struggle between the spiritual power (the Rebbe) and the earthly power (the Austrian government) resulted in a tie: once my father was not called up and once, he was.

My father was sent to Hungary for training. I do not remember where he was posted later. I just remember him telling me that he spent much of the war working in offices, instead of in the

[Page 7]

trenches, thanks to his many skills as a secretary, repairman and jack-of-all-trades.

My father being absent, the entire family, my mother, my brother and me, my maternal grandparents, my great-grandfather Mordecai (Mordkhe) Kasner and my paternal grandmother Rachel, prepared to leave. They hired a farmer from a nearby village, loaded their most precious belongings on his sleight (it was already late November), and pulled by two strong horses, they started a trip which was to last four years.

They headed towards the village of Konyatin, situated on the Bucovinian side of the Czeremosz hight in the Carpathian Mountains, about 95km from Kuty. One of my father's sisters, Esther Klein-Rosner, lived there. She was married to Shaye-Wolf Rosner, a widower with two or three children (who else could a poor girl like her marry without a reasonable dowry?).

Why did my family decide to go to Konyatin? Here are the words of my mother: “After talking it over with the neighbours, we decided that it would be impossible for the Russian army, especially the artillery, to pass over the high mountains, and so they cannot reach Konyatin where the surrounding peaks are in the 1500m to 2000m range”. Poor mother! Neither she nor her neighbours had ever heard of Hannibal. It was much easier for the Russians to penetrate the Carpathians with their horse-drawn cannons than it had been for Hannibal to cross the Alps with his elephants. And so, a few weeks after my family had reached Konyatin, the Russian army reached the village in the middle of winter.

The Rosners had a pretty big house with a few rooms and a general store. The Russian officers

[Page 8]

requisitioned one part of the house for their use, and “naturally”, helped themselves from the store whenever they wanted to. Aunt Esther had to cook and bake for them too.

I heard later, also from my mother, about an incident which convinced my family that it was time to leave and join the other families who were moving further into the heart of the Austro-Hungarian empire. One day, a Russian captain was having his breakfast in the house. He started slicing some bread and then yelled out: “Khazayka! Do you want to poison us? Look at that bread”. Aunt Esther came running and saw that the slices of bread were coloured with different shades of blue. After some checking around, the saw that the bags of bread flour were stored under some shelves where bags of paint powders were stored. Obviously, some of the powder had accidentally dropped into the flour. The captain saw where the flour was kept and understood what had happened. But, after breakfast, he and his fellow offices decided to “scare the Jews”. They took everybody outside, lined them up along a wall and prepared a mock execution. A few soldiers made a lot of noise loading their rifles, yelled at the “prisoners” and told them they were going to die. After an hour of torture, the captain told everybody that he forgave them this time but that the next time, the execution would be a real one.

A few weeks after the incident, my family decided that it was time to leave. So, for the second time in a few months, they rode through the mountains on a hired sleight, this time toward the Slovakian border. Here, there is a gap in the story: I don't know where they reached a train line

[Page 9]

or how they got there, but they finally entered Bohemia (there was no Czechoslovakia then). They settled as refugees in the town of Kolin, about 50km from Prague.

The Galician refugees in Bohemia, like those who crossed in Hungary or those who continued on to the capital of Vienna, were now officially recognized as refugees and the Austrian government took care of them.

I don't know much about the four years my family spent in Kolin. We did not talk about it much after our return to Kuty at the end of the war. I was too young for that. I remember a few things from what I had heard later. In 1915, my material great-grandfather, Mordkhe (Mordecai) Kasner passed away and was buried in Kolin. First, my older brother Uciu (Raphael) and later I too went to a kindergarten where some activities were carried out in German and some others in Czech. My father, stationed in Hungary, came to visit us a few times on leave.

Some people remember things from the time when they were three or four years old, but I have no recollection whatsoever from the Kolin years. Nor do I remember our return to Kuty after the war at the end of 1918 or the first months back in Kuty in 1919. However, I find that although I don't speak Czech at all, the Czech language has always seemed to me more similar and closer to Polish than any other Slavic language. Perhaps there is some trace of those childhood years in Kolin after all.

On November 11, 1918, W.W.I. came to an end “officially”. I say “officially” because until the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, the borders between the European countries were not finalized and a lot of fighting was still going on in several places. There was fighting between the Poles and Lithuanians, between the new Soviet government and the newly resurrected Poland, between the forces of the Ukrainian Hetman Petliura and the Red Army and between the revolutionary forces of Ataturk and the government forces in Turkey.

As for Kuty and the surrounding villages, they were first occupied for a few months in 1919 by the Rumanian army which had crossed the Czeremosz after having conquered Bucovina, following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian empire. After a few months of the Rumanian occupation, the bands of Hetman Petliura attacked and incorporated the region into an independent Ukraine, which they created and which lasted for about six months.

For Jews who came back from exile then, it was a very dangerous period. The bands of Petliura were known from the pogroms in Eastern Ukraine, and a panic overtook the Jews. There were anti-Semitic attacks but it was not as bad as in Eastern Ukraine. However, it was bad enough that I heard about the terrible “Petliurczyki” for years, while I was growing up. I do not remember the exact year that the new Polish army reached Kuty from the North, but

[Page 11]

from 1920 on, we became Polish citizens and at the age of six, I entered the Polish public school.

When we came back from Kolin our house in Kuty was half ruined. The Russians kept horses there. For that reason, they had knocked down some walls and doors and modified different things. The wooden floors were ruined, encrusted with horse manure and full of holes.

My father had been demobilized and had joined us for the return to Kuty. He was a perfect handyman and could “create” something from almost nothing (like a big bang). He could repair any tool, pieces of furniture and other domestic objects. He was a painter, carpenter, mason, cobbler, butcher and even a cooper. For a few years, he always repaired or resoled our shoes with pieces of leather taken from old shoes.

Painting, carpentry, masonry and shoe repairs were everyday work for the first few years after our return. Once, he bought roughly hewn pieces of beechwood, finished them into staves and assembled them into a bathtub with the help of steel hoops. We used it for years.

All this work was done between Tuesday afternoon and Friday afternoon. One might think that from Sunday to Tuesday afternoon, he was idle. But it was not his work at home which was feeding our family: my parents, maternal grandparents, my paternal grandmother and two small children.

This is what he was doing to make a living: From the time he was a teenager, he used to do business with the mountain people, buying cattle from them and reselling it to the butchers in

[Page 12]

town. He also worked for a certain period in the lumbar yards of the local sawmills.

From his frequent contact with the butchers, he learned how to skin an animal and how to carve up the carcass. This quasi-apprenticeship came in handy in the preparation of homemade smoked meat.

Speaking of homemade smoked meat, I thought it worthwhile to describe the way we made it in some detail. The smoked meat making, an important part of the self-sufficiency period of my father's activities, was taking place in the fall. The whole production was a kind of ritual in our house.

The meat we used was always from sheep. We got sheep from the Hutzuls who were doing business with us. Usually, it was as payment for some transaction, but sometimes, we bought a sheep from them. When a Hutzul owed my father some money and couldn't pay him anything for a while, he would bring us a sheep. This didn't affect the amount of his debt, so it was a kind of gift (or extra interest payment).

Normally we would have had to bring the sheep to the municipal slaughterhouse, about 2km away and pay some fees. However, the shochet lived across the lane from our house, so we would let him in at night through the door of our stable. By calling the shochet in this way, we had to pay only him and so avoided the municipal and Jewish community taxes. (Of course, this was not really legal and that is why we did this at night).

The shochet would come in and slaughter the sheep. After that, he slit open the belly of the sheep, seized the windpipe and pulled out the

[Page 13]

lungs and liver which came out attached together. He would blow into the windpipe and inflate the lungs like a balloon. The, he examined the organs and according to what he saw, he declared the animal kosher (or sometimes not kosher). And then he would go back home across the lane. After the shochet left, we hung the sheep from a beam in the ceiling of the stable with a hook and a cord.

At dawn, my father would wake me up while it was still dark outside, and we went to work. I say “we” although my main job was to hold a lantern (a small glass cage with a lamp inside) so that my father had enough light to work. My father began by cleaning out the sheep, removing all the organ meats which we saved and used in our stews. He took out the innards, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys and brain and even the ram's testicles. Although these latter are located on the rear part of the animal, they are considered kosher. I always wondered why, but never found a good explanation for this strange fact. This didn't prevent me from enjoying the delicious taste of this delicacy when I fished it out of one of my mother's stews. After cleaning out the animal, my father skinned the sheep. After that, he separated the front or kosher part, from the non-kosher part. He carefully cut out the principal veins and arteries (trebern in Yiddish), all still clogged with blood.

My father sold the non-kosher meat to some Ukrainians he knew and he sold the skin to a furrier. By selling these parts of the animal himself, he got a better price than by selling them to a butcher. This way, he made enough money to recover the cost of the sheep when he had bought

[Page 14]

it himself, or to earn a bit of money when he had received it as payment.

After that, my father would cut the head off the carcass. The remaining kosher part of the animal was split down the middle. Then, from each side of the neck, we cut out strips of meat, about 10-12 inches long and about 3 inches wide and 1 inch thick. These were pieces of meat without bones. Each side of the rest of the carcass consisted of half the rib cage. All this meat, including the two halves of the severed head, was not turned over to my mother for koshering.

Here let me make a digression. One has to know that meat from a kosher animal, slaughtered by a shochet, cannot be eaten by an observant Jew before it is koshered. The purpose of the koshering procedure is to remove all of the blood from the meat. So, this is how my mother koshered our meat (she did this with all the meat we ate, two or three pounds of beef or veal, for soup or a roast, a chicken, and not just with this smoked meat that I am talking about here). She would spread out pieces of meat in a wicker basket and lay the basket across the top of a bowl. The basket was my mother's colander. She then would salt the meat generously (including the two halves of the severed head) and leave it to drip out its blood into the bowl for an hour or so. After that, she would put the pieces of meat into another bowl which she filled with water, and the meat was left to soak for another hour or so. By the end of the hour, the meat was rid of practically all of the blood. And so, finally, the meat was kosher and could be cooked or grilled and eaten.

After my mother had koshered the meat, we began the preparation of the meat for smoking.

[Page 15]

We placed the meat in a wooden bowl. In another bowl, we combined some salt, pepper and garlic, a small package of mixed spices and crushed it all into a paste. Each piece of meat was rubbed with this paste taking care that it penetrated well into the meat. We then added some bay leaves. The meat was then covered with a weight to press it down and was left to marinate in the bowl for a day or two.

Then came smoking the meat in the chimney. We used beechwood at home both for heating and for cooking. Smoking meat can only be done with a hardwood such as beechwood; softwoods like pine or spruce do not work well because of the resin content and because they produce huge, sudden flames which overheat the chimney. This can burn the meat or dry it out. Our chimney rose up from the kitchen oven and passed through the attic. The part of the chimney that passed through the attic had a kind of door in it, essentially a large opening in the side of the brick which was opened or closed by a panel on hinges. And at that spot, inside the chimney, there were some wooden planks fixed vertically to the brick.

These planks had some hooks screwed into them. We hung the pieces of meat from these hooks with some strings. The meat stayed inside the chimney for two or three days, depending on how much cooking my mother did that week. After the two or three days of slow smoking, the meat was ready to be eaten. By then, it was completely smoked and cooked.

We ate the boneless meat, sliced thinly, as a snack or in a sandwich. Sometimes, we grilled some pieces of meat over live coals and then sliced them. This meat tasted even better. The rib

[Page 16]

cage belonged to my mother's kitchen. She would take the rib cage and break it into pieces. The ribs still had some meat on them and she would put a few ribs into a pot with a cup of white beans and cover it all with water. She brought this to a boil and then, depending on how long she would let it simmer, it became either a soup or a thick stew. Both the beans the ribs were delicious.

We usually ate these meals with mamaliga (the Rumanian word for polenta) and some homemade pickles (the making of these pickles is another long story which I will not tell here).

Even after being here in Canada for years, I used to dream of this wonderful homemade delicacy. I even though of building some kind of smoke house in my backyard to produce, if only approximately, the real smoked meat of my childhood. Although now I like to eat smoked meat in Montreal, to me it always seems to taste like a product of “exotic” spices, artificial colouring and some chemical flavouring to imitate the taste of the smoke produced by a hardwood fire. With time, like every immigrant, I started to get more and more used to the local foods, including the “smoked” meat. After a few more years, I even started to like ketchup, relish, etc. The only think I still don't like is the world-famous, ubiquitous Coca Cola (and this happens to be both my sons' favourite drink!). Imagine, to give Canadian citizenship to a person who doesn't like Coke, - quelle horreur!

Let us now return to the activities and occupations of my father in his youth or in the post WWI years. My father started to work in one of the city's sawmills when he was only 16 or 17 years old. He was young and inexperienced and

[Page 17]

was paid a very low salary. However, he was very observant and learned quickly on the job and soon he was in charge of both shipping and receiving.

The administration of the sawmill used to require periodical inventory taking. This would take a day or two and no business could be transacted during the inventory. After one of these inventory days, my father had an idea. As he was in charge of shipping and receiving, he started keeping a ledger of all the incoming and outgoing logs. In addition, he noted the number of planks these logs yielded, their volume in cubic meters, and so on.

When the next inventory day arrived, my father went to see the administration and showed them his ledger with all his records and calculations. He told them that they did not need to shut down for an inventory-count anymore. After some discussions and verifications, he was proven right. And, he got a big raise.

After our return from Bohemia, my father started over again the routine of doing the rounds of the neighbouring villages. He used to get up on Sunday morning at 4 o'clock, get dressed according to the season and go up deep into the Carpathian Mountains and go into the valleys of the streams flowing into the Czeremosz. He had to get up early because a large part of his business was done on a Sunday, near the churches where he met most of the people going in or out of mass.

As he knew almost everybody in the region, he found out who had something to sell that day and he made some notes. He would spend the next two days visiting all these people in their huts or

[Page 18]

cabins where he was shown the animals they had to sell. Then came the sacrosanct haggling procedure, eastern bazaar-style. Irrespective of the outcome of the haggling over every penny, the visit ended with some food on the table.

My father did not usually bring much food with him. There was enough food available which a (non-ultra) orthodox Jew could still eat in a Catholic household: milk, yogurt (made from non-boiled milk), eggs, potatoes, cornbread, fish, fruits, etc.

The villages he visited most frequently were: Rozhen, Tielki, Rozhen Maly and Bialoberezka, all lying 20-25km from Kuty. And he walked all the way, most of the time.

My father also tried his hand at tanning. Together with his cousin, Motie Schamir, they bought skins from the peasants and made leather for the moccasins the mountain people used to wear. It was not Box calf but a good primitive leather (called Youcht) of a brownish colour. The skins were washed, soaked in a vat with oak bark for a time and then put in slaked lime. After a few weeks, came the scraping of the skins with two handled knifes (similar to the cooper's knives for making staves). The scraping cleaned the skins from the remaining bits of flesh. It was very delicate work because a faulty movement of the knife could result in piercing the skin in several places, making the skin worthless. The same went for the colouring.

This tannery adventure didn't last long. Soon better products appeared and there was no more market for the youcht leather.

When we came back to Kuty after the war ended in 1918, the very first thing my parents did was to send the children to a Hebrew school. Although calling it a school is most definitely an exaggeration. The teachers were Jews who did not have any teaching qualifications. They didn't know much more than how to read and write. Their living and teaching quarters consisted usually of an all-purpose room and a kitchen. The main room was a living room, bedroom and a schoolroom all at the same time. The school was a long table in a corner with two benches on opposite sides with a chair at the head of the table for the teacher. My teacher's name was Avrum Lulke. This was not his family name and, in fact, I never knew it. In small towns, many, if not most of the people had nicknames. A lulke is a pipe in Yiddish. I don't remember now if he smoked a pipe or not, but this doesn't really matter. People inherited nicknames from their parents or even from their grandparents.

Some nicknames alluded to a profession, a trade, an infirmity or a foreign origin. I knew people whose names were Boruch the carpenter (who did construction work); Chaim the carpenter (specialized in furniture), Barish the baker, Fishel the butcher, Yosi the watchmaker, Leibuniu the mason, Motie the Bulgarian and Leibele the hunchback. They were all pretty close neighbours, but I never knew their real family names. Some of them were named after their father, their mother or even a grandparent. Older people called

[Page 20]

my father Velvel Rocheles (Rachels). One of our neighbours was called Avrum Ethel Feyge Menashes (Abraham son of Ethel the daughter of Feyge, herself daughter of Menashe). And still no know family name.

Coming back to Avrum Lulke, like all the other “Dardeke” teachers, he had a “belfer”. Dardeke in Aramaic means small children. The word belfer comes from the German Beihelfer and means a helper. The belfer looked after the children, repeating previous lessons with them when the Rebbe, as the teacher was called, was absent, sometimes for reason of sickness, or for some other reason. But this was not his principal occupation because his real boss was the wife of the Rebbe. He ran errands for her and even did housework for her. He chopped wood, brought water from the well or took a chicken for the ritual slaughter to the shochet.

The Rebbe's wife also did some teaching. She taught the children the morning and evening prayers. The children in the cheder, as this kindergarten was called, were all boys and there was no parallel school for girls. Thus, the Rebbe's wife went to some (usually well-off) families' homes to teach the girls to read and write in Yiddish (not in Hebrew like the boys). She also taught them some special prayers for women.

In the fall of 1920, with the Polish government having pushed south as far as possible and now being firmly established in our region, I was enrolled in the Polish public school. A few months earlier, I had also left the kindergarten cheder for a cheder of a higher level where we studied mostly the Pentateuch (Chumash) and some of the prophets.

[Page 21]

This is how it came about: One day in the summer of 1920, the teacher of this cheder, a friend of my father, came to our house for some reason that I don't remember. He looked at me and said to my father: “Velvel, let's see what this boy knows, maybe he is ready to enrol in my cheder”. Opening a chumash he made me read. He was amazed. He said: “There is no reason for the boy to waste even one day more with Avrum Lulke. He is ready to learn Chumash and the prophets and translate into Yiddish”. A week later, I enrolled in his school.

Now I embarked on a busy life. From 8 a.m. to noon or even 1 p.m. in the Polish school and from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. in the Cheder. Besides this, in the morning before going to school, my father took me with him to the synagogue for morning prayers (shacharis). In the summer, we went there around 6 a.m. and in winter at 7 a.m. Very few of the boys my age went to synagogue for morning prayers. In our house, it was routine. In the beginning, the public school was located in a huge two-story building. The boy's school was on the 1st floor and the girls was on the 2nd floor. The schoolyard was divided into two parts – one for the boys and one for the girls, and there was almost no contact between the two. It wasn't until 1925 that our boy's school was transferred to another building leaving the old one entirely for the girls.

The year 1922 was a disastrous year for our family as it was for several other families in town. The post-war typhoid epidemic finally reached the region. My mother and my brother Uciu contracted the disease.

My father was their only nurse for weeks and weeks. He had nobody to help him and there was no hospital in Kuty. The nearest one was in Kosow, 10km away and in those days, that was very far. He couldn't afford to hire somebody to help him and he couldn't leave the two of them alone to visit the villages and do business. He passed night after night at their bedside, sometimes not even undressing, to be ready for an emergency. As if this was not enough, I myself was struck with scarlet fever. There was only one doctor in town and he was overwhelmed. There were a few good doctors in Wiznitz on the Rumanian side who could be called to come to Kuty, but they charged more, and more importantly, they had to be paid immediately in cash. And my father didn't have the money. Then, suddenly, a new doctor came from a northern Polish town and opened an office in Kuty. I always remembered and still remember her name: Dr. Buzath. She was a young woman freshly out of medical school. She married a local judge. My father went to see her and told her: “There are three sick people in my house. I would like you to come and see them but I have no money to pay you now. I promise you that I will, in time, pay you for your visit”. She came to our house. I don't

[Page 23]

know if it was to promote herself in the town or if she was really devoted to her profession (but I always felt that it was the latter).

She came several times, sometimes twice a week and never mentioned the money. She showed my father some nursing techniques. Much later, when my father was able to do business again, the first thing he did was to start to repay his debt to her. Sometimes I think she must have been an angel incarnate. She nursed my mother and me to health.

Unfortunately, my older brother (who was 10 years old) was getting worse and worse. Finally, he passed away, while my mother was still very sick, with a high fever and periodical fits of delirium. She did not know that her son was gone forever. She only learned it after she had recovered enough so that she could be told about it. One can only imagine her chagrin. My brother was considered the genius in the family. His marks in Cheder and in school were much superior to mine.

That same year, my paternal grandmother, Rachel, also passed away. She was in her sixties. She was in a coma for a few days. One day, my great-uncle Leiser Kasner, came to visit and stayed a few hours with us. Before leaving, he looked at my grandmother; he asked for a feather, ripped off a piece and held it on her lip, under her nose. Then he said: Baruch Dayan Haemeth (Praised by the true judge). She was dead.

In 1923, my mother bore another son. He was named Mordechai Isaac (at home he was called Bubciu). These diminutive names, like mine and my brothers were very popular in the Austrian empire and lasted far into Polish times. We wanted to name him Mordechai inly but a neighbour of ours begged my parents to add the name of Isaac, after the name of her father, because she had no children. So, his birth certificate listed him as Mordko Itzig Klein, in the Polonized spelling.

After the birth of my brother in 1923, my parents decided that my father would abandon his old way of life. He wouldn't go any more, every week for 2 or 3 days into the villages. Instead, he would trade with the Hutzuls when they came to our town. Also, my parents would open a small store and sell the milk products they bought from them.

In the mid 1920's, we sold our small house near the Ukrainian church and moved into the restored house of my great-grandfather Mordecai, which stood next to my grandfather's house. My great-grandfather had left his house to his two sons: Leib Kasner (my grandfather) and his brother, Leiser Kasner. My grandfather eventually left his part to my mother and then we had to buy my grand-uncle's part back from him.

[Page 25]

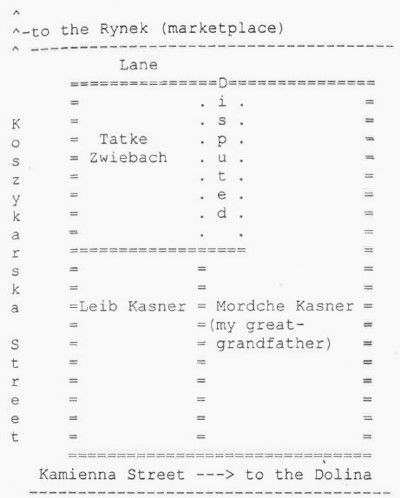

The layout of the buildings was something like this:

My grandfather's next-door neighbour, Tatke Zwiebach, had a small stable where he kept a cow (we got our mile from him during Pesach). He asked my parents to sell him a part (about 1m wide) of the adjacent stable in our new house. His stable was very small and inconvenient. At first

[Page 26]

my father refused to sell. But Tatke wouldn't stop pestering us and finally he used blackmail. He threatened to offer much more money to my great-uncle for his part of the house if we didn't accede to his demand. Finally, my parents gave in and only then did we buy my great-uncle's part of the house.

This episode was soon forgotten. With time, we came to realize that Tatke was literally up against a wall (our wall). In his stable there was so little space that milking and feeding his cow were difficult jobs. Soon our relations with Tatke improved and our families lived as good neighbours until the end.

Tatke Zwiebach's father's name was Abraham Itzik, and his nickname was Mitziu. One of Tatke's sons was named after this grandfather. His other son was named Yankel, after Tatke's brother. Tatke's brother Yankel had served in the Austrian army in WWI. At the end of the war, after the armistice was signed on November 11th, there was still some shooting for a few more days until all the troops everywhere were informed that the war was over. The story was told in Kuty that Yankel was just sitting around with some fellow soldiers, on one of those days right after the end of the war, when he was killed by a stray bullet.

Tatke also had three daughters: Pepi, Shlima (named after her grandfather Shulem) and Ethel. The whole family, save for Ethel who emigrated to Israel after the war, perished in the Holocaust.

So now, during the day, we spent our time in my grandfather's house because the store of dairy products that we had opened was located in a part of his house. In the evening, we passed back into our house.

[Page 27]

From the time we opened the store, my mother became very busy. My grandfather's house was the centre of the business. My father still did business with the Hutzuls who came to see us and it was my mother who ran the store most of the time. This work was in addition to cooking, baking and doing the housework.

Besides the usual work in the store and in the house, my mother had also seasonal things to do, like for the holidays or some special tasks in the spring or the fall. In our old house, before we moved into the house of my great-grandfather, she raised chickens in the spring. The hens with their chicks wandered around the house. Often, they went out the door and even crossed the street and got as far as the yard of the Ukrainian church where they pecked for food. They usually came back on their own, but in the evening, we would count them and sometimes find that one or two were missing. Once we found one of them dead in the barrel of water we kept for our daily use. Since we had no running water, someone had to get water every day from one of the wells in town. Usually, it was the water carrier who emptied the pails she brought from the well every day into our barrel. Sometimes the missing chickens were stolen, sometimes they were killed crossing the street. From a flock of about fifteen, we were usually left with about one third.

After we moved into my great-grandfather's house, which was more spacious, my mother had another seasonal occupation, this time in the fall. We bought a dozen geese and we kept them in a cage in the attic for about two months. We bought some big bags of corn grain to use as feed to fatten them up. The corn was cooked until it was soft

[Page 28]

And that is how we fed the geese. Sometimes, when I went up to the attic for some reason, I would reach into a bag of corn and grab a handful of grains to munch on. With time, the geese would put on a layer of fat. They would usually put on between 1.5kg to 2kg of fat. We checked them often and we would slaughter those that were fat enough first and keep on fattening the rest for a few more days. By the beginning of winter, all the geese were gone. We rendered the fat and stored it in jars. We used some in our daily cooking and we kept some jars for Pesach (when we made wonderful latkes with goose fat). We did all our dairy cooking and all our baking with butter and we used the goose fat for frying and roasting meats. We made enough to last us almost to Rosh Hashanah the following year. We used almost no oil and the main thing we used it for was to spray the baking utensils (our way of non-stick baking). We used so little oil that half a litre would last us for a year.

The fattening of the geese has another story. Some people do it by force-feeding the birds, stuffing handfuls of corn down their throats or even sticking a funnel into their mouths to shove more food into them. That way the birds put on more fat. The Rabbis do not allow that. They say that there is a risk of tearing the oesophagus and an injured bird or animal is not kosher. However, there were some Jews who did it anyway. There were rumours in the family that my great-aunt Rivtzia Kasner force-fed her birds. But my mother didn't want to hear anything about doing it.

It was only later, when we were doing better, that we hired a housekeeper. She was Ukrainian from a nearby village. She didn't earn much

[Page 29]

because she was paid a “hypo-minimum” wage. She slept on a wooden bench in the kitchen. She cleaned both of the houses, did the washing and did some other housework. She became like a member of the family and after a certain time, she could speak a passable Yiddish. Unfortunately, after a few years, her story did not have a happy ending. This is what happened: One evening after we passed into our house from my grandfather's house, my father went into the room where he kept his documents and some money. When he went to the cupboard where he kept the money, he saw that the door was broken wide open and the lock pried off. The money had disappeared. The money amounted to a few hundred zlotys and a few hundred U.S. dollars (in the 1920's some business was still done in dollars in Poland). We called the police. They interviewed everybody, including Annetza, the housekeeper. They even grilled her but my parents said: “leave her alone, we vouch for her”.

A few weeks passed. One day, one of our neighbours, Juda Engel who had a store near the marketplace, received a customer, a Ukrainian from a nearby village. He looked around for a while, chose an item and when it came time to pay, he pulled out from his pocket a $50 note. Mr. Engel was suspicious. I don't know if he knew the story of our break-in, but he found it strange that a poor villager would have a $50 bill. So, he continued talking to the man but asked an employee to call the police. It turned out that the man was the uncle of our housekeeper Annetza. One day, before we had come home for the night, she had let her uncle into our house through a door leading to a usually deserted lane,

[Page 30]

and he had done the job. We recovered part of the money. The uncle went to jail and the housekeeper was let go. After that, we hired a Jewish housekeeper, Taube, an old maid who was recommended to us by our shoemaker, her brother-in-law. This woman stayed with us until the Soviets came in 1942. She did not do the heavy work like the washing, which was a two-day operation. The household linen was put into a big kettle which was filled with hot water; a bundle of beechwood ashes tied in a piece of cloth was suspended in the kettle. The kettle was boiled for about two hours. The ash released sodium hydroxide into the water. This was the first stage of the cleaning. Then came the washing by hand in soapy water and the passing through rollers to squeeze out the soap. After that, the whole load was placed on a hand driven carriage and taken down to the river canal (Mlynowka, a mill canal). The washer-woman chose a big flat stone and installed herself near it. She then took out every piece of linen, rinsed it in the canal, placed it on the stone and flattened it. She then beat it with a small thick board which had a handle carved out. She repeated this process several times with every piece, alternating the rinsing and the beating. Then, everything was reloaded on to the carriage and brought home. The linen was hung out to dry and then came the most important and final phase: the ironing. My mother, had for years, employed the same woman. The ironing alone took almost two days. My mother was very fussy about it and constantly checked and verified every detail. The iron itself was a box with a lid on hinges and with holes on the side. Before ironing, it was filled with live

[Page 31]

coals to keep it hot. The ironing was my mother's most favourite obsession. It simply had to be perfect. And finally, it always was, even if the woman had to do it over again. I inherited this obsession from my mother. I am not a particularly well-dressed person, but a badly ironed shirt irritates me to this day.

My mother worked hard and for several years in the 1920's, she would go for a few weeks in the summer time to one of the villages near Kuty for a kind of vacation. She would stay with some distant relative and even though she was often only an hour or two from home, she would stay away from home during her “vacation”.

As I said before, in 1920, I enrolled in the Polish public school. Even though around 50% of the population was Jewish, there were no Jewish teachers except the teacher of religion. This teacher was not a Rabbi but a graduate of a special institute where Jewish religion teachers were formed. It was more Jewish history than religion. For the lessons of religion, the classes were separated. We had our teacher; the Poles had a Catholic priest and the Ukrainians a Greek-Catholic priest. This class was about two hours a week.

This absence of Jews was seen in many other professions besides teaching. There were no Jewish judges in the regional courts, no bailiffs and no stenographers. The same was true of the post office, the tax department, the municipal services,

[Page 32]

or the police, and in general, no government department employed Jews. With very few exceptions, most of the Jewish employees from the Austrian period were let go and no new ones were hired.

For the first few years after the war, Kuty was a pretty backward place: no running water and no electric power. There were a few wells and professional water-carriers would deliver water to peoples' homes. They carried a bar on their back with a can or bucket of water hanging down from each end. We had a big barrel at home which the water-carrier would fill up every second day. In the summer, the water was mostly luke-warm and in winter, there was a crust of ice on the barrel which we had to break every morning. For a few years, there were no street lighting in the town. There was no municipal bath-house. The Jewish community built its own bath-house which served as a combination of bath-house, sauna and mikvah.

Towards the end of the 1920's, things started to change. The streets and access roads to the town, often muddy until now, were covered with gravel and sand and compressed with heavy rollers. Then came the construction of sidewalks. They were made of sandstone slabs carved out from sandstone deposits in the nearby mountains. Trees were planted and gas lamps were installed on the corners of some of the busy streets. A building to house cultural events was constructed. This building had a large hall which served as a movie theatre where silent movies were shown on Saturday and Sunday evenings. Sometimes plays were presented in Polish or in Yiddish by local organizations, or, sometimes by

[Page 33]

Famous theatrical companies coming from Lwow, Warsaw or Wilno. The hall also served as a meeting place for the Polish Scouts organization, for political parties and annual Polish balls. There were also two other halls; one Ukrainian and one Jewish where each community celebrated its weddings.

Returning from Bohemia, from Vienna or from Slovakia after the war, a small number of Kuty Jews emigrated overseas, mostly to the United States. But the great majority tried to forget the war and rebuild their lives in town. Some opened new stores, brought in merchandise from wholesalers or from plants in the big cities. Some owners of horse-drawn wagons carried the merchandise to the villages of the Czeremosz valley in the surrounding mountains. There were also carriages which served as buses until they were replaced a few years later by motorized vehicles. They linked Kuty to Kosow and even to Kolomyja. Many Jews also worked in the flour and saw mills (constructed by Jews) on the Czeremosz canal. Tanning was another industry in town. There were a few tanneries, all owned by members of the Grebler family.

After 1930, another industry started up in town, the kilim industry. A kilim is a carpet woven on a loom, with a cotton warp and a woollen woof. Middle class people bought the looms and placed them in the homes of poor families where the family members worked on them (for a minimum wage). The owners of the looms then hired agents (salesmen) who travelled across the country selling the carpets.

For years, the kilim industry put bread and butter on the tables of poor families and enriched a few individuals who had a strong sense of entrepreneurship.

[Page 35]

Most of the business was conducted five days a week – from Monday to Friday. The Jewish stores all closed late Friday afternoon, at different hours depending on the season. The rynek (marketplace) and the surrounding stores were closed. Only a few Polish or Ukrainian stores were open and there were also a few Ukrainian re-sellers who sold some food products.

On Saturday, the Hutzuls didn't come to town and no town people went to the marketplace. The centre of the town looked like a totally Jewish town. Jews coming and going to the Synagogues, older people strolling in the streets after lunch, the sound of chopping onions and liver on kitchen counters. A Saturday lunch consisted of chopped liver, pot-au-feu with kugel or latkes and tzimmes (dessert), usually a mixture of carrots and prunes and then tea with lemon. This was our usual Saturday lunch and there were not many variations. Teenagers often bought pumpkin seeds and walked around town talking or discussing politics and cracking the seeds. Some streets were covered with layers of white pumpkin seed shells, giving the street sweepers a lot of work.

Sunday the stores stayed closed by law. Except for some small store owners, especially groceries. It was very difficult for these small stores to lose two whole days of business a week. As the divine law (Halacha) was considered more important than the law of the government, they tried to do some business on Sundays. These small stores were often located inside the owner's homes and there were generally double entrances and exits. A member of the family was on the lookout to see if there was a policeman around,

[Page 36]

and if not, he would let in one or two, and sometimes more, customers. The customers didn't wait around. They pretended to stroll about and when the coast was clear, they went inside. There were heavy fines for opening on a Sunday but most of the time, the owner would get off by paying a small bribe to the police.

Saturday mornings were spent by most men and by older women in the synagogues. There were ten synagogues in Kuty. The most beautiful building was the Great Shul. The roof was supported on beautiful pillars which, like the walls, were decorated with paintings representing biblical scenes. The balcony, reserved for women, was decorated in the same way. There was no heating and so few people went to pray there during the winter months. The Great Shul was also used as a hall for political or religious speakers. The great majority of the Jewish population were members of the smaller synagogues called Besmedresh or Klaus. Dos naye besmedresh, dos hoiche besmedresh, dos Peltzen besmedresh, dos chassidishe besmedresh, die Kosover Klaus, die Wiznitzer Klaus, die Tchortkower Klaus and two small synagogues built-in on either side of the Great Shul: dos Katzowische (butchers) shulechel and dos schneidereche (tailors) shulechel.

The name “besmedresh” comes from the Hebrew: beth hamidrash, which means house of learning. The name “shul” comes from the German: Schule, which means school. This shows that Jews were always using their houses of prayer for learning and for the education of their children. Also, the title of Rabbi originally meant teacher, a prestigious title in Talmudic times. Ancient Rome and Greece followed this example. The titles 'doctor and master' (magister in Latin) originally meant teacher. The word 'philosopher' originally meant l

[Page 38]

over of wisdom. It is a pity that in modern times, teaching is neither a highly regarded nor a well-paid profession.

The name Klaus comes from the Latin clausus, a closed place or room. We used it for synagogues whose members belonged to a group following a Chassidic rabbi (Wiznitzer, Kosover, Tchortkower, etc). Or, who had once belonged to such a group when the synagogue was founded or first built. In my time, anyone could belong to those synagogues.

The approaching Saturdays and holidays were visible and palpable on every street, on every corner and in every house. It is important to distinguish between purely religious holidays, Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur and national holidays like the Shalosh Regalim (Pesach, Sahvuot and Succoth). High Holidays were days of prayer, reflection, fasting and asking for forgiveness. We used to spend almost the entire day in Shul. During the Shalosh Regalim, besides saying the appropriate prayers, we were also concerned with more earthly matters, eating well, singing, parading, etc. The preparations for these holidays were especially lengthy and elaborate.

Shalosh Regalim in Hebrew means “The Three Pilgrimages”. For these holidays, many people travelled to Jerusalem. These people were the Oley Regel, or “Those who walk up” because Jerusalem is in the Judean mountains.

Pesach

Pesach, besides being a national holiday, also had a social significance. The Hagadah says: “Kol dichfin yaysay veyaychol, kol ditzrich yaysay veyifsach”. This means: “Let all who are hungry enter and eat; let all who are needy come and celebrate Pesach”. In their commentaries, later sages and Rabbis wrote that this was not to be

[Page 40]

understood literally. One is not being asked to invite the poor to a Seder but one has to see to it that they are provided with everything they need to celebrate the holiday.

Rich people in Kuty gave the most, middle class people gave less and the community officials distributed it all as best they could. The money that was donated was called “Maos Chitim” (money for wheat), because flour for Matzohs is the symbolic Pesach item.

In the first years after WWI when everyone in Kuty was struggling to rebuild his life and when everyone was too poor to give to charity, the Jewish society in New York sent money for Maos Chitim. This lasted for a few years until we, in Kuty, could afford to do it ourselves. Today, most synagogues in North America collect the money for Maos Chitim. Here it is called a “Campaign for the Needy”.

The preparation for Pesach started the day after Purim. The important things were a thorough cleaning of the house, buying new clothes for the children, making the borscht, baking the matzos and koshering some kitchen utensils. The highlight of the cleaning was the white-washing (with slaked lime) of the walls of the house. Everything which was broken or not functioning was repaired. The wooden floor was scrubbed and sometimes repainted. We had a separate set of kitchenware for Pesach, but some steel or cast-iron pots and kettles would be koshered. To kosher a kettle, it was filled with boiling water. An iron rod heated on live coals was then plunged into the hot water which then started bubbling violently for several minutes. This made the kettle kosher-le-Pesach and it

[Page 41]

Could then be used during Pesach. Neither enamel kitchenware, clay nor stoneware could be koshered because of their porosity. Then came the borscht. There was no Manishevitz, no Rokeach nor any other borscht makers. My mother would peel and then cut beets into large pieces. She put the beets in a barrel, covered them with water and let them sit there for a few weeks. No vinegar and no sugar were added. The fermentation was natural and resulted in a borscht which was ready to heat and serve. The fermentation method was used at Pesach because an ordinary beet borscht required the addition of vinegar and vinegar is not Pesachig and cannot be used during Pesach.

Now it was time to buy new clothes for the children. Until 1926, my mother never bought a read-made suit for me. She used to go see Hersh Leib Shnyapkes (this is his nickname. I never knew his family name), who had a big store of fabrics. He was an elderly Jew, bearded and wore a yarmulke. Hersh Leib had know my mother since she was a young girl and he addressed her informally (with Du instead of Ihr).

My mother would test several kinds of fabric between her fingers to see if they were of real wool and when she finally chose one, the haggling would start. This phase of the buying process lasted a relatively long time. Sometimes when they couldn't agree on a price, Hersh Leib would say: “Shayne Frayde, you go home and send Velvel to me and we will make a deal”. He would say that because he knew that my father didn't bargain much. What my father told my mother when he returned, I don't know, but I supposed that he didn't tell her the whole truth and nothing but the

[Page 42]

truth, for the sake of Shalom Bayith (peace in the house).

With the fabric bought, we went to Shaye Kluger, our tailor. There, again, there was bargaining over the price, and later, during the three fittings, haggling over the measurements, the quality of the accessories and over when the suit would be ready, over the final adjustments. He, too, knew that y mother would notice the smallest imperfection and that she would ask for it to be corrected.

With the Matzoh, it was like with the borscht, no Manishevit, no Streit, no Israeli matzohs. There was not machine-made matzoh (shortly before WWII, matzoh-making machines appeared in the bigger cities). A few Jewish families who had big kitchens and big ovens turned their houses into matzoh bakeries. They hired people to knead, roll and bake the matzohs. They had their regular customers every year. The majority of families did things a different way and we were of that group. About a dozen families in our neighbourhood banded together to buy the flour and install the necessary equipment in the house of the Blaukopf family across the street from our house. A copper basin for the kneading, long planks of wood stretched out between two tables for the rolling, koshered containers for the water and the long-handled shovel to push the matzoh into the hot oven. The oven had to be koshered before baking. A huge pile of wood was erected in the oven and lit. It burned for hours. The live coals were spread over the whole surface of the oven and left until everything cooled off. This resulted in the complete elimination of every trace of chometz. The water had to be brought in

[Page 43]

from the well the day before the baking and was left overnight (I never knew the reason why). The Ukrainian servants had to be accompanied to the well by a Jewish child or an older person because there was a danger that they might eat something on the way and thus drop a crumb of bread or some other chometz into the water they were carrying.

During the years when we were part of this group of families, my father was the kneader and I would stand next to him with the water jug and pour the water over the flour when my father said “Noch a bissel”. As there was no yeast and no waiting for the dough to rise, each mayra (piece of dough) was ready in a few minutes. The dough was cut into pieces and was then put on the long table where a dozen women were busy rolling the dough and then passing a toothed wheel over it to make the holes in the matzohs to prevent bubbling. Then the baker would put the matzoh into the oven. These matzohs were round and came out of the oven arched, not flat.

The equipment was ours and after the baking was over, we took it home. My father's motto was: “if you need a tool, a container or some other utensil only once a year, buy it and never borrow”. We then took our share of the baking, about 15kg of matzoh, put it in a huge basket, brought it home and stored it in the attic. It lasted for weeks after Pesach.

The usual Pesach means were more or less the same as Saturday's, except that the challah was replaced by matzohs, potatoes and (lots of) latkes. The adults only drank coffee in the morning before going to the synagogue. The children got matzoh crushed into boiling hot milk.

[Page 44]

By the time we came to the evening of Erev Pesach, the house had already been thoroughly cleaned from top to bottom. There was now no bread left anywhere in the house, except for what we would eat for breakfast the next morning. After supper, we began the symbolic cleaning out of the last trace of bread in the house. We went around to every room and placed a few crumbs of bread in a corner. As soon as we had finished putting down the crumbs, we started to go through the house, room-by-room to “clean” it of all chometz. We used a goose feather for this special cleaning to sweep up the crumbs into a wooden ladle. Then we emptied the ladle full of crumbs into a small bag which we kept until the next morning.

The next morning, the day of Erev Pesach, we ate breakfast around eight or nine. This was our last meal of chometz before Pesach. We usually had a bagel with some milk. This was a Kuty bagel. It neither looked nor tasted like a Montreal bagel. This was also the only time of the year the I ever remember us eating a bagel. The mil we used for this meal already had to Kosher for Pesach and it came from our neighbour Tatke Zwiebach's cow (for Pesach we wouldn't use the milk we usually bought from the peasants). Then we ate the piece of fluden that we had saved since Purim especially for this meal, the last meal where we could eat bread. After breakfast, we took out the bag of crumbs that we had collected the night before. We then said the appropriate b'ruchah and burned the chometz in the stove.

After the evening prayers, we sat down for the first Seder. It was a very solemn meal. Our Pesach supper was fish, soup with a lot of latkes,

[Page 45]

different meats, kugels, desserts and last but not least, a lot of reciting, singing and chanting of the Haggadah from beginning to end, without omitting a single letter. My father was a very good singer and reader. I wasn't too bad either, but now with the passage of time, I am forgetting some of the melodies.

We knew that some people, after finishing their own Seder, would go to the house of Shaye Bergman, our Baal Tefila, and stand outside to hear him and his family sing the Haggadah. Shaye had two sons, Berl and Leibele, who were his choir in our synagogue. However, at his home, the choir was bigger. His two daughters and some said even his wife, joined in. The Bergman women, contrary to many others, were educated in Hebrew. There was another son, Avrum, the eldest, about whom strange stories circulated in town.

Apparently, Avrum was not present at the Seder. He was a lawyer and had never married. Besides lawyering, he also tutored some boys. Since he didn't need this extra work to make a living, the general consensus was that he must be a homosexual. Later these rumours were confirmed. We once went to hear the Bergman's Haggadah singing, but we didn't go again. Our Seder lasted until pretty late in the evening and besides, we heard Shaye and his sons regularly in our synagogue.

The first two days of Pesach were very solemn. The next four days were Chol Hamoed, a half holiday where there was less prayer and when one could work. The last day, the 8th day, was also the day of Yizkor with prayers for the dead.

[Page 46]

Shavuot

The second of the Shalosh Regalim holidays is Shavuot. It is a commemoration of the day we received the Ten Commandments, engrave on the two-stone tablets that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai. Shavuot was a holiday that was celebrated with less preparation and less fervour than Pesach. I always thought that it should have been the opposite, and here is the reason why: It is true that the liberation from Egyptian slavery was the first step in our becoming a free people. But we were then only a band of undisciplined and lawless nomads, destined to wander in the desert for forty years. The Bible also says that many Egyptians, tired of Pharaoh's rule, mingled with the Jews and left Egypt. Some slaves of other ethnic groups and some couples of mixed marriages went out with the Jews too. The Torah calls all these non-Jews who followed the mass of Jews leaving Egypt, Eirev Rav (the great mixture).

This reminds me of the massive Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union during and after the period of “Perestroika”. Many non-Jews, ethnic Russians or members of other ethnic groups, passed themselves off as Jews in order to join the Jewish emigration. At that time, non-Jews were not allowed to leave the Soviet Union. This confirms, once more, King Solomon's famous saying: “There is nothing new under the sun” (Ayn chadash tachat hashemesh).

We became a normal settled people only from the time that we received the Ten Commandments and all the other laws that Moses

[Page 47]

introduced. One can call this a constitution, a codex or a charter. Without this foundation there only exists a free-for-all state that is anarchy. That was the state of the Jewish people before the Ten Commandments and the Mosaic laws. It is an axiom since centuries and especially in the modern world, that only a people who live on its own national territory can be called a free and independent people. The Jews, as happens so often in their history, are an exception. Standing at the foot of Mount Sinai, the people assembled there heard The Voice from above say to them: “Today, you become a free people” (Hayom nihieta l'am). They did not yet have a defined territory (it would take forty more years of wandering in the desert to come to it). The Jews became a free and independent people, not through physical force, but through the spiritual force of the Torah and the Ten Commandments.

During Shavuot, the houses were decorated with green branches and flowers and we only ate dairy products. In the synagogue, the cantor read the poem of Akdamoos which exalts the greatness of the Lord. And he read the scroll of Ruth, the story of the Moabite girl who married Boaz, the grandfather of King David.

[Page 48]

Succoth, Hoshana Raba and Simchat Torah

The third of the Shalosh Regalim holidays was Succoth when we would build a Succah. The Succah is a hut covered with branches and other green plants built in remembrance of the tents in which the Jews lived for the 40 years in the desert after leaving Egypt. For the 8 days of Succoth, we ate all our meals in the Succah (when it didn't rain). On rainy days we just made Kiddush there and then fled inside our house. There was no roof over the it. It had to be covered only with branches or other green plants so that they sky could be seen through the openings. My father made the Succah from panels he assembled into walls and then he put down some planks to make a floor. The Succah was mounted on the outside, against the walls of the house. During the year, these panels and the planks were stored in the attic.

At first, we used to cover the roof with branches from pine trees, but in dry weather, the desiccated pine needles would fall into our soups and sauces and it was difficult to fish them out. Sometimes, one of us would start coughing and choking on a pine needle. So, in later years, we began to cover the Succah with corn (maize) stalks. This too had another small inconvenience. Me and my friends used the dry tassels for tobacco and rolled cigarettes from the husks which enveloped the cobs. These cigarettes would burn with a pungent odour and taste, and often resulted in one of us being overcome with nausea and vomiting.

[Page 49]

Of the nine days of the Succoth holiday, only the first six days were the true Succoth. During the first two days we spent the whole morning in the Shul and then ate our meals in the Succah. The next four days were Chol Hamoed, a kind of semi-holiday with less prayers. During these four days, one was allowed to work. The seventh day was Hoshana Raba. The eighth day was Shemini Atzeret and the last day was Simchat Torah.

Hoshana Raba

The seventh day of Succoth was Hoshana Raba. It is a very interesting holiday. On the one hand it is a regular working day like any of the other (four) days of Chol Hamoed, and on the other hand, it is a holiday unto itself. This day is closely related to Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur. Our sages say that God does not seal His verdict for every person's life during the Neilah prayer (the last prayer) on Yom Kippur. But in fact, the verdict is only sealed on the day of Hoshana Raba; Consequently, each person still has the possibility of repenting until Hoshana Raba and be forgiven for his sins.

The part of Hoshana Raba which stands out most in my mind is the custom of the “banging of the willow branches”. When the Chazan began to sing the first words of the prayer Hosha-na, everyone, especially the children, started to bang the tables, desks and benches with a bunch of willow branches that they had brought to the synagogue for this purpose. This made a lot

[Page 50]

a lot of noise and left the floor covered with a layer of leaves from these branches.

Before the service, many Ukrainian and Polish children came to the front of the synagogue carrying bundles of willow branches. They got them from the banks of the river and sold them to us for a few groshen (pennies). These willow branches were called, in Yiddish, Hoshanas (what else!). The words Hoshana Raba mean, in Hebrew, “The Great Save Us” (Hoshana became Hosanna in the Christian liturgy).

I never learned the explanation for this custom. I think that it must have originated in the Middle Ages when such actions were believed to repel Satan, who, on this day, acted as prosecutor against the people, while God decided their verdict. Anyway, it was a tradition and still is in Orthodox synagogues, and we children adored it.

Simchat Torah

The ninth day of Succoth was Simchat Torah. On this day we read the last chapters of the book of Deuteronomy and so finished the reading of the Pentateuch for the current years.

On this day, every male gets an Aliyah (is called to the Torah), even children who were not bar-mitzvahed yet. With only one read, this would have taken hours, so the seven or eight Torah scrolls were taken to the homes of various synagogue members where other readers could officiate. My maternal grandfather took home a scroll which had been donated in memory of a member of the family by his father, Mordecai.

[Page 51]

A group of neighbours came home with us and one of them read from the Torah. This was only until I passed my bar-mitzvah and could then be the reader. In the afternoon, we invited a dozen or more members of the synagogue, the same people who had come for the reading in the morning and we had a good time together. My mother had baked a lot of pastry during Chol-Hamoed and there were nuts of different kinds, fruits, kugel and a barrel of beer. These were wooden barrels, corked on one side. The barrel was placed standing up and a wooden faucet was hammered in through the cork. We ate, drank, danced and sang zmirots. What stands out in my mind is my grandfather's cousin, Avremel Kastner, dancing on the table when he had drunk too much. Normally, he was a kind of fun-loving person, a jester and all the more when he had a glass too much to drink. There was a very heimish and festive atmosphere and it was my favourite holiday after Pesach. I will come back to Simchat Torah later.

Shemini Atzeret was celebrated in exactly the same way as Simchat Torah with the same prayers and the same Hakafot. Hakafot means the designation of the people who got to carry the Torahs around the synagogue.

[Page 52]

Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur

The High Holidays were purely religious (not national) holidays. They were called in Hebrew, Yomim Noraim, which means awe-inspiring holidays. This conveys perfectly the atmosphere which prevailed during the holiday period, first during the days leading up to Rosh Hashana and during the holiday proper.

For a whole week before Rosh Hashana, we recited the Slichot prayers, some at midnight and some at dawn. During the first two days of Tishre, we passed five to six hours at the synagogue and another two hours in the evening.

Before Yom Kippur, my mother went to the market to buy the poultry for Kaparoth: roosters for the men and hens for the women. On the eve of Yom Kippur, every single person took a bird, hoisted it over his head and said a short prayer in which it is said that we place our sins on that bird which would be sacrificed, and then we asked for forgiveness. This is probably a reminder of the ancient times when the High Priest in Jerusalem took a goat, placed his hands on the goat's head and sent it away into the desert (where it must have died from lack of food and water) to atone for the sins of the people. From there comes the expression 'scapegoat' which became, in our case, 'scapebird'. The chickens were then brought to the shochet. I remember standing in line at the shochet's for an hour or more because the line before the entrance to the shochet's place was usually very long. Part of the meat from those chickens was eaten after Yom Kippur and part of it was given to the poor.

[Page 53]

Then came the candles. A few days before Yom Kippur, my mother bought sheets of wax. They were broken into pieces which were placed in hot water. When the wax became soft enough, it was rolled into a long cylinder which was then flattened into a long tablet, about six centimetres wide and about 70-80 cm long. There were two of them which served as two candles, one for the living and one for the dead. The wicks were made of several cotton threads. They were put in the middle of the table and the wax was closed over the wick. The cotton threads were placed one-by-one and the name of a family member was pronounced over each one. Each thread represented a person, dead or alive, depending on the candle. These huge candles were placed in boxes filled with sand and brought to the Shul before Kol Nidre and then lit. They were placed in the corridor leading to the sanctuary or even inside the Shul. The smell of the burning candles was awful. The smoke irritating but when the Chazan intoned Kol Nidre, nobody paid attention to that. We spent two hours in that hot and choking air and then almost everyone went home, but a few older people stayed the whole night. My grandfather was one of those who stayed. They would read the Psalms and some other chapters from certain Prophets or later authors. Can we imagine today men in their seventies, fasting for 25 or 26 hours, staying awake all night and praying most of the time?

During the day, it was prayers from eight in the morning to eight in the evening with only a short interruption of about two hours between Musaf and Mincha. At around six o'clock, everyone came back for Neila. It ended around eight and

[Page 54]

then Maariv was read and only took a few minutes. Then everybody waited for the Shofar. From the age of 10, I tried to fast. At first, I could only fast until 11 or 12 o'clock. At the age of 12, I fasted until 4 p.m. but I started to get weak and vomited. So, during Mincha, I ran home, grabbed a piece of bread, ate it in a hurry and ran back for Neila. At the age of 13, I fasted the full day for the first time. For weeks after Yom Kippur, I was humming the tunes of the holiday prayers. They were ringing in my ears. For no reason, I would find myself singing silently Kol Nidrei tunes, Hallel tunes or Sh'mone Esrei tunes. They were a part of me.

Lesser Holidays (Post Biblical)

Purim

Purim is a commemoration of events told in the scroll of Esther, Haman, a minister at the court of the Persian King Ahasuerus (some historians believe that he was the historical kind Artaxerxes), plotted the destruction of the Jewish population of the Persian Empire. Esther, the Jewish Queen who succeeded Vashit, foiled the plot. She begged the king to spare her people, revealing to him for the first time, that she was Jewish. The king annulled the decree he had already signed and authorized the Jewish community to resist and even kill their assailants. Then he ordered Haman and his sons to be hanged.

[Page 55]

Before visiting the King, Esther had fasted and prayed for three days. That is why we fast the day before Purim. It is called the fast of Esther (Tanit Esther in Hebrew and Esther Tahnes in Yiddish).

Before Purim there was a lot of cooking and baking and buying of fruit. This is because in the scroll of Esther, it is written that when she succeeded in thwarting Haman's plan, there was a great rejoicing among the Jews. There were big feasts, eating, drinking and gift giving. This gift giving remained as a feature of Purim to this day (especially among Orthodox groups). Ordinary households kept the habit of giving part of the food to the poor.

Another feature of Purim was buying or preparing masks for the disguises of the children. The children went out in disguise visiting the neighbours and asking for a groschen (a penny). Most of us wore only a small mask and that was our disguise. I also got to wear a piece of fur on my shoulders that served as my cape. One place that we visited was a tiny store owned by a man called Reuven (I don't know his last name). I remember him because he used to make us dip our index finger into a bowl of indelible ink when we came in to ask for Purim gelt. This way, we couldn't come back later to ask him for another Purim gift. Some would put part of this money into the boxes of the, Keren Kayemet for Israel-Palestine, or those of Rabbi Meir Baal Nes, a quasi-saint and sage, but others kept it for themselves. What did I do? I will invoke the fifth amendment now against self-incrimination!

The baked pastry lasted until Pesach. The last chometz breakfast on the eve of Pesach consisted of a bagel with mil and a piece of pastry

[Page 56]

remaining from Purim. In our house, this Purim pastry was a piece of Fluden, a cake made with honey, jam, nuts and lemon and spread over a thin flaky pastry dough.

There was also a popular Purim special event in the person of Chaim Pesie Roises. He was the shames of the Great Synagogue. He blackened his face, put on a wig with long hair and dressed like a gypsy. He carried a bell mounted on a pole which he shook so that he was heard coming from far away. Children ran to him and followed him making a lot of noise. He had a bag on his shoulders. He visited wealthy people and collected gifts for the poor in need for Pesach. It could be a gift of money or a pledge for 25 or 50kg of potatoes, a pledge of meat or matzos, which would be distributed later. He was an institution in himself.

And last but not least, during the week of Purim, there was a ball organized by different Jewish groups (mostly Zionist), with refreshments, good music and dancing.

Chanukah