|

[Columns 161–162]

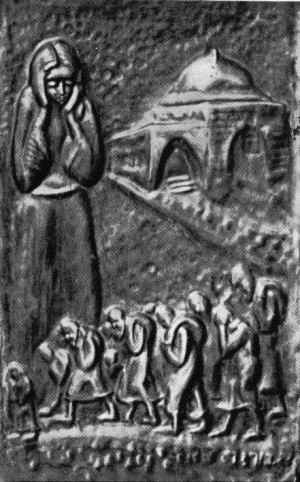

Memories from the Survivors

Columns 163–164

|

|

|

|

[Columns 165–166]

by Zehava Fogelman (Golde Akerman, daughter of Yoshke the cantor

Translated by Yael Chaver

English text transcribed by Genia Hollander

|

Zahava Fogelman (Golda Ackerman, daughter of Vosske the Hazan) was 19 years old when war began. There were four sisters and six brothers. The Germans entered the town after it had been bombed and burned. They compelled a Hassidic Jew to violate his own daughter before their eyes.

Zahava sewed trousers for the Germans and left needles in the seams. An action took place to liquidate the Jews. However, she was taken for a Christian and fled to Warsaw. In the Ghetto, she found a brother and her little sister.

A liquidation action commenced against the Warsaw Jews. She escaped to the Aryan side. Her little sister was shot. She lived together with her brother and other Jews in a camouflaged bunker on the Aryan side.

The Ghetto revolted. The Poles laughed. Zahava obtained cyanide of potassium. She had papers in the Polish name of Halina Wiszniewska. Dr. Lotek Grozberg, one of the people hiding in the bunker, developed lung disease and coughed. Since he might give away the others in hiding, he committed suicide.

The Russians approached. The Poles revolted. Polish anti–Semites shot her brother. His child, Hayimel, was concealed with Christians for payment. Zahava, who was supposed to be a Christian, worked in a secret Polish patriotic organisation.

The Russians entered. She returned to Warsaw. The Poles attacked her; robbed her and wanted to kill her. They were killing the Jewish survivors.

She married a survivor and came to Eretz Israel.

At the breakout of the war she is 19 years old.[3] Her family includes four sisters and four brothers. The Germans entered the town after it had been bombarded and burned. The German murderers force an ultra–orthodox Jew to rape his daughter. Zehava sews trousers for the Germans and leaves needles in the seam to prick them. The Aktion (operation to exterminate Jews) happens. Zehava looks like a Christian. She flees to the Warsaw ghetto and finds her sister and brother there. After the liquidation of Warsaw's Jews, she finds refuge in the Aryan section of the city. Her younger sister is shot by the Germans. Zehava lives with her brother and other Jews in a bunker. The Warsaw ghetto revolt begins. The Poles laugh. Zehava acquires a capsule of potassium cyanide. She has a Polish identity card in the name of Halina Wisniewska. One of the people in the bunker develops lung disease and coughs increasingly. He feels that he might betray the others hiding in the bunker, and commits suicide. The Russians approach. The Polish revolt occurs. Polish anti–Semites shoot her brother, who dies. Chaim'l, her brother's son, hides with Christians, for pay. Zehava works, as a Pole, in an underground Polish patriotic organization. The Russians enter the city. She returns to Warsaw. Poles attack her and rob her of her money. The Poles also want to kill her. They kill the surviving Jews. Zehava marries a Jewish survivor and emigrates to Israel with him.[4]

[Column 165]

A Father Forced to Commit Rape

In 1939, when the Germans took Poland, our town disappeared into flames. Only the Christian homes and churches remained. With great effort, anyone who could hammered together a rough shack out of boards, or stretched a roof over a surviving cellar, where they settled. This miserable accommodation was paid for dearly. The misery had just begun: hard forced labor, and murders. The murderers would attack the cellars by night and carry out murderous beatings, or humiliation for no reason. For instance, they once forced a Hasidic Jew to have sex with his daughter. One time, they came into the Kurow mikveh, where a pair of paupers – not locals – had found refuge.[5] The gang was headed by a Volksdeutsche from Puławy named Gedo, whom the Poles nicknamed “guinea pig.”[6] They beat the Jews bloodily, and did not leave before they

[Column 166]

tore off more than one ear, or gouged out people's eyes. As if this weren't enough, two strange Germans would occasionally come to pay us a visit. One was named Neffert. Compared to them, the past dog–beaters and horse thieves of Kurow were weaklings. They did not leave unless the street flowed with Jewish blood. They once came upon a friend of mine, Feyge Elenboygen, in the street. They beat her so badly that she bled all the way home as they followed her. They came the next day, to see whether she was still alive. Our own Ulrich, a German who had lived in Kurow from before the war, did not lag behind them either. Every night, he and his son would make the rounds of Jewish homes and demand money. He was especially vindictive towards Yitzchok, Elye's son, of Markuszów, with whom he had owned a mill in Kurow before the war. They tied him to a horse, which was whipped by its rider

[Column 167]

into a wild gallop. In this way they dragged him through the streets; when the Jew was half–dead, they untied him. When Yitzchok recovered a bit, he secretly fled to Lublin and hid there the whole time.

It is hard to say how Jews made a livelihood at that time, because travelling between cities was punishable by death. Even staying on the outskirts of a town or spending the night in a different house was forbidden. It was not so bad for tailors and shoemakers, as they had some work from the peasants in the neighboring villages, and were paid in food. My parents were hit very hard. My father, a scribe of sacred books, transcribed no more Torahs. He was a cantor as well, and was actually called “Yoske Khazn.”[7] However, our synagogue and house of study went up in flames. My father was able to rescue some Turkish tallises, prayer books, tefillin – which he himself had transcribed – and mezuzahs, in which he used to trade.[8] But who needed any of these? People were concerned, above all, for a bit of bread. Even before the war, this type of merchandise was in small demand; as the saying goes, “many professions and few results.” These days, it was even worse!

I stick needles into the Germans' trousers

So I went to work, mending uniforms for the Germans. In any case, they forced the remining young people to wash their floors and do their laundry. Now I was free of such tasks and was often paid by bread. But the fact bothered me intensely. I couldn't accept the fact that I would do such work for them. So I would leave needles in the seams. A German once put on a pair of trousers mended in this way. The instant he sat down he began to scream–he had sat on a needle. I was sure it was the end of me. But I was lucky to escape, simply because the Germans were suddenly ordered to leave Kurow and go to the front lines. Then I went to dig up potatoes at a farm. At the beginning I couldn't straighten up after work, because I wasn't used to it. We were paid by the piece, in potatoes. Because of this work, I was bent and crooked for a long time afterwards. Yet in spite of this work, we would have had nothing but water if not for my brother Arn, who worked in tailoring. He shared everything with us. down to the last bite, and also supported my sister–in–law's parents. We were four sisters and six brothers. Six of us were already married, and not everyone lived in Kurow. My youngest sister left for Warsaw, where my brother lived, at the very beginning of the war. I was the only one at home with our parents.

[Column 168]

“We don't give a damn”

My father was extremely observant and God–fearing. He always had great faith in God. But seemingly overnight, he turned, not gray but white, One time the Germans went around cutting beards off Jews. My father was very fastidious, and his beard was very well–kept. When they came to my father, the Germans' hands seemed paralyzed. They left his beard alone. My mother was the type to faint; now, she passed out often; when she revived would say, “What will happen, Yoysefshi, what will happen?”[9] Then my father would start singing, “Why worry about tomorrow? It's better to think about yesterday's deeds.”[10] He would then add, “We don't give a damn, we'll survive them.” This phrase cheered up the Jews as they went to forced labor. The Jews lived under terrible conditions, yet always had faith in God, hoping for better times.

Until the merciless year of 1942.

The first resettlement curse came to Lublin eight days before Passover. No one knew then where and what this was. Soon rumors started that hundreds of Jews had been gruesomely murdered on the spot. This spread great terror through the surrounding towns. My parents and the other Jews of Kurow wrung their hands and mourned the fate of the Jews of Lublin. Among them were my oldest sister Reyzl and her family, who lived in Lublin. But we couldn't mourn the Jews of Lublin for long, because these very events were repeated among us, in Kurow itself, on the last day of Passover.[11] At that time we were living near the pasture, among Christians. The whole town was encircled by SS gangsters. Shots were heard everywhere. The door of our apartment was soon pulled open, and the bass tones of the above–mentioned Gedo thundered in German: “Any Jews here?”

“It's God's decree!”

A neighbor happened to be visiting us who was a fellow student of mine, a Christian. Wanting to show that he knew German, he answered in that language, “No Jews here.” My parents weren't home, and the Germans went away. I went to the home of my Christian neighbor and asked him to go out and see what was going on. Ten minutes later, he returned and reported that all the Jews had been taken to the synagogue square; he said he had seen my parents there as well. Hearing this, I made a package, locked the door, and ran over to the square. The Germans who had come to our house and been answered “No

[Column 169]

Jews here” recognized me, identified me as Christian, and drove me away with their whips from the imprisoned Jews, thinking that I was trying to bring them food. I heard the last words of my dear father, “Don't come near, don't you see that it is God's decree!”

Hearing his cries, they ran over and beat him. I refused to leave and was arrested. However, as they thought I was a Christian, they let me go immediately. On the way home I saw the former Kurow magistrate with a wagon making the rounds of the houses and carting away the last Jewish possessions gathered over years of hard work.

From Kurow to Warsaw

Night fell, In terror, I spent the night at a Christian house. At the crack of dawn I went to Klementowice. I was stopped twice for inspection, once in Klementowice and again in Demblin. They were looking for goods the peasants would smuggle into Warsaw. They found nothing on me. No one recognized me. I arrived in Warsaw at night and waited at the train station along with the crowd until daybreak. Secret agents roamed the crowd, looking at people suspiciously. I collect my courage and look around boldly, though my heart is racing. I see many people being taken away, and hear shots right away. I am lucky here again. No one identifies me as Jewish.

It is day. I don't know what to do, where to go. I don't know Warsaw, and certainly have no idea how to get to my brother in the ghetto. At this point I remember the address of a Christian, through whom I used to send my brother packages. With no other choice, I decide to go to him. I already knew that no one identified me as Jewish, that I look like a Gentile girl, and I also knew the language well. I had decided earlier that I would not let anyone recognize me as Jewish. The fact that my brother had confided his location to this Gentile was another good indication that he could be trusted. I arrive at his place, tell him that I'm coming from Kurow, trying to make out his reaction. He immediately responded that I need not fear him, and made it clear that he was happy to take me to my brother. He was a tram inspector, on the only tram line that entered the ghetto.

People in Warsaw don't believe me…

At about 1:00 I sit in the tram with him. At 22 Franciszkanska the tram starts slowing down – apparently the inspector had arranged it with the driver – and I jump off.

[Column 170]

At my brother's, everyone was overjoyed to see me, while mourning the destruction of Kurow, about which they had already heard something. My little sister, who was staying with him, was very comforting. Some neighbors gathered, and consoled themselves with the thought that nothing like that could happen in Warsaw. It can't be denied that many Jews from the small towns flee to Warsaw; it's a big city, after all. No one believed the horrors that I recounted. Here, life was still more or less normal. I stayed with my brother for two days, and found that not even a crust of bread remained of his wealth. He had invested all his money in leather and walled it into one room. The Germans later took it.

In Kurow, I had hidden money that my sister Reyzl and brother–in–law gave me before I went away to Lublin, saying that no one else in the family need know. I followed their command, and did not touch the money even when times were hardest for the family. Later, I regretted it. Now, I decided to go back to Kurow and get that money. Everyone at my brother's begged me tearfully not to go. My little sister Dina hugged and kissed me, crying. “Don't go,” she begged, “you barely saved yourself.” But I didn't care, after my parents were taken away. I was so attached to them that I couldn't bear being without them in a strange place, even for a day. People used to laugh at me for still being tied to my mother's apron strings, though I was already 22.

Back to Kurow to dig out the money

I become almost careless. It doesn't matter. I'm prepared to be shot any minute. I crawl through a hole in the ghetto wall, and am outside.

Once again, I'm on the Aryan side. A Christian suddenly sees me and starts bothering me: if I don't give him money, he'll take me to the police. A tram passes by just then, and without thinking I jump into it, leaving the Gentile standing. Here I am, on the train again, to Kurow. I walk from Kementowice with several village Gentiles. They don't identify me, and have no idea that I am Jewish.

I stop near Kurow. It's only a few days since Kurow was afflicted. I tremble and grow chilled. Not a soul can be seen. I suddenly see Khayim Khanesman (now living in Israel), who somehow remained. I tell him everything, as well as why I've returned.. He comes with me to dig out the money. As we're walking, Zsaba – a former janitor famous for his thefts–comes up. He tells us that

[Column 171]

|

|

|

in the Po'ale Zion youth organization Sitting: Gitl Helfant, Rivke Lerman Survivors of this group: Taytlboym (Israel), Akerman, Lerman (New York) |

he's going to inform the Germans immediately. I ask him to bring a shovel and help me, and I'll pay him well. He is overjoyed and runs off to get a shovel. In the meantime, Chaim'l quickly helps me dig out the money, and by the time the janitor comes back I'm gone.

In the meadow by the river, I sew the money into my clothes. I've had nothing to eat or drink all day. I washed up a bit, and was on my way again. Once again, I went through two inspections safely, and am soon in Warsaw again with my brother. One thing less to worry about: we now have enough money. Resettlements occur from time to time here as well, but only from one street to another. Life is still normal: cinemas and theaters are still active, cafes are open. Only the number of beggars has increased.

Cinemas, theaters, beggars

Every day, at the same time, a little girl appeared on the street and sang with her last remaining strength in a voice that was beautiful though weak. People would throw down a piece of bread or a penny. There were also people called “snatchers,” who

[Column 172]

would grab food that someone was taking to work, or bread that he had bought. They would snatch and swallow it quickly, so that it couldn't be snatched back. Hunger increased and touched more and more people.

Six months after the resettlement in Kurow, the same process started in Warsaw. People heard that all the Jews of Kurow had been burned up, but no one believed it. Who knows, perhaps many could have been saved in time if they had believed it.

Czerniakow understood[12]

It started with the orphanage. The director was ordered to hand the children over.[13] He refused. He was then taken along with the children. The Jewish police were now commanded to provide a certain number of Jews every day or they themselves would be shot. Then the same was demanded of Czerniakow, the head of the Jewish Council. He understood the situation and what was going to happen, and asked the Germans for ten minutes to reflect. The Gestapo agreed to give him ten minutes, and went away. When they came back ten minutes later, they found Czerniakow dead. He had committed suicide rather than send Jews to their death.

Thousands were snatched off the streets every day and sent away, saying that they were being sent to work. The Germans also announced that those who volunteered to go would receive a daily loaf of bread with marmalade. Even the strongest porters pushed and shoved to get a better place in line. The Germans forced the prisoners inside the rail cars to write cheerful letters to their remaining relatives. However, a few persons escaped, and their accounts spread like lightning: quicklime was poured into the cars and people suffocated en route. Those who arrived alive were incinerated. How they were incinerated was not yet known.

Workshops, Umschlagplatz, Jewish police, Ukrainians[14]

At this time workshops started to be established, following the orders of the Germans. This meant that those who worked would not be deported. Various jobs were created in the shops: those of Tebens, Shultz, Aksaka. Jews paid large sums to get these jobs; the “shops” were headed by Jews. I myself paid 21 dollars for each of us to get into the Aksaka shop, where German uniforms were mended. Our director was Zemsz, a Warsaw Jew. However, all the workshop commanders seemed blind, and did not realize that they were being deceived. We would go to work every morning. One day we heard rumors that there would be a selection in our shop.

[Column 173]

By then, everyone knew what that meant. And that's actually what happened. The shop was quickly surrounded with yells, “Everyone out!” I began to feel dizzy. We were all standing outside, and a German with a stick motioned to people to go left or right. Left meant death. We, too, were directed to the left. We were already at the Umschlagplatz, from which Jews were loaded onto the rail cars like cattle and sent to death. We stood there and watched. Jews were being loaded on. Older people were shot to death on the spot as we watched, and bodies were being flung out of rail car windows. We waited in our line in the square. Suddenly, Meir Danzger, a guy from Prague (now in Israel) who had been with us the whole time, noticed a Jewish policemen he knew. He bribed him with much gold and dollars, and the policeman led us out.

You'd think we were saved? We had gone only a few steps when we suddenly heard “Halt! Hands up!” Two Ukrainians stood a few paces away, holding loaded guns. Shaking with fear, we approached. They led us into the courtyard and showed us many dead bodies; many people were barely breathing, and we could hear some faint moans. The Ukrainians turned to us: “You can still buy your way out with rings or watches. Otherwise you'll be shot.” Luckily, we had that type of merchandise: a few tin rings. We knew that they considered all that glittered to be gold. Once again we bought our freedom, and went on.

The Yom–Kippur candle and my little sister[15]

The Germans attacked mostly on the Jewish holidays. Once, on the eve of Yom Kippur, a neighbor in the next room lit a memorial candle.[16] Their wall adjoined our room, in which my sister and I were asleep. Suddenly there was a loud banging on the door: “Open!!” The residents of our courtyard flee to the hideouts they had prepared, cramming themselves into holes. But we stay in our beds unable to move, because the slightest rustle would betray us. We would immediately be seen through the window that opened out into the street where the murderers stood. Suddenly we hear the words: “We will slaughter you all if you don't blow out the light!” I'm ready to go and blow the candle out. But my little sister doesn't let me and struggles to stop me. In the dark, I grab her by the hair. I think, they are tricking us. She broke loose, to go and blow out the candle. I was left holding a tuft of hair. In that instant, I heard a shot, then another shot, and my sister's voice, “Golde, Golde, I'm dying!”

[Column 174]

She grew silent. I started shaking. My little sister! My one remaining consolation! I run in. It's dark, and I actually see her, lying on the ground. I try to pick her up. My hand reaches deep into her body, groping, and is dipped in blood. It's true, she is no longer alive! It is hard to imagine. I thought I would go out of my mind. Her voice was ringing in my ears: “Golde! Golde!” Her last words ring in my ears to this day. Each time I remember, it seems that pieces of my heart rip out. My brother came immediately. He had been on the second floor, and could only wring his hands; he could no longer cry. The next morning, they came with a box to bury her. I paid well, so that I could later at least have a marker of her grave. But they erected no marker. My brother Yisro'el turned gray overnight, and couldn't even speak to me. I didn't go to work for several days, until they ordered me to, and I had to go.

I become a real Gentile girl

One of the neighbors who visit had parents who were taken long ago. His name is Lotek Grozberg. He used to be a student at the surgical clinic; he's about thirty years old. He started urging me to go over to the Aryan side, and kept encouraging me to do so. I decided to take a gamble and do something for my dear remaining brother. I felt a strange inner force that drove me on. In any case, staying here was certain death. I also remembered that I was never identified anywhere, which encouraged me.[17]

I used makeup on my face, so as not to appear so pale, and crossed over. Life hung by a thread. Crossing over was not so easy. The ghetto was watched constantly, and anything unusual led to shots. This time, as well, luck was on my side. Once I was on the Aryan side, I met up with the Christian acquaintance who had taken me to my brother. Now he was hiding a Jewish girl, with whom he was in love. Knowing this, I could trust him without fear. At that time, there were enough empty houses, abandoned by the Jews who were forced to go into the ghetto. One needed only to go to the housing office and put their name down as a tenant. Any Gentile girl who even thought of getting married could have an apartment. This is how I got an apartment, at 16 Nowowiniarski St.[18] I paid the same Christian to create a Kennkarte[19], as it was called. I myself went to sign the card.

Well, now I'm called Halina Wiszniewskza. I'm a real shiksa[20]. Now, how do I take care of my brother?

[Column 175]

He needs to go to the Aryan side for work every day, and is of course watched by the Germans. Meir Dantziger, the guy from Prague who had become famous in the ghetto for good hideouts, also needs to be gotten out. I was able to fool them and get him out. Everything was risky and smelled of death. But there was nothing to lose, and I was successful. Once he was in my apartment, he started working. He walled up a door of the farthermost room, leaving only a small slit next to the floor, the width of the carpet that covered all the floors in the apartments. He glued a piece of plywood of the same size under the carpet, and attached a long strip of molding that ran from one corner of the wall to the other. The entire floor had these strips, which could be opened, and we could crawl in on all fours, like rats.[21] It was made very cunningly, and was invisible. The conditions and fears in which we lived are hardly imaginable. Meir Dantziger, who created this hideout, stayed there. When everything was ready, I smuggled out my brother, his wife, and their seven–year–old son, Chaim'l. This is what spurred me on. I slowly got used to this way of life, and walked the streets boldly. In any case, we were ready, thinking that we could be discovered any day. However, we felt much more secure here than in the ghetto. Here, we only feared the Poles. Over time, we had gotten so used to it that we were indifferent to everyone. Here, though, there was at least a chance; but Jewish hideouts were revealed here as well.

We look over at the ghetto and see the uprising

Later, Dr. Lutek Grozberg came to us, as well as the woman from Ryczywoł and her daughter.[22] They came through a sewer, bent over and wet to the waist. (Her husband had been shot by the ghetto underground, because he was the supervisor of a workshop.) They all came into the hideout, and we somehow rearranged ourselves. It wasn't too long before two more people arrived. One was from Prague: Vaysblat and his sister. They knew about us while they were still in the ghetto. I became anxious, first–because people knew about us; and second, it was really becoming crowded. There were nine of us altogether.

Our apartment was across from the ghetto and the brush workshop. We could see events in the ghetto, and often heard terrible screaming. One day, when I was in a street far from the apartment,

[Column 176]

shots suddenly rang out. I heard talk that the Jews had rebelled. I run home, and see many tanks already driving into the ghetto. Mortars are set up across from my apartment and shoot into the ghetto. Groups of Christians stand around laughing and enjoying the sight of Jews fleeing from a burning house. Molotov cocktails are flung out of the ghetto houses at the entering German tanks. Many also threw stones. Reinforcements arrive, thousands of armed Germans, as if preparing for a major battle. As if this wasn't enough, squadrons of planes came over. They flew low, dropping firebombs. Everyone in our house was happy and danced, thinking that Russian planes were coming to help the Jews. But I realized the truth, the bitter truth. The screams of burning Jews grew ever stronger. People came out of the burning hideouts on the top floors.. Hoping to save themselves, children jumped out of windows and were snagged on balconies, where they remained hanging. One image that I saw will stay with me to my dying day. On the fourth floor of a house opposite Nowiniarska Street, an elderly Jew inside a brush workshop wrapped himself in his tallis. Not wanting to fall alive into the hands of the murderers, he set himself on fire. I saw the flames engulfing him, and he fell like a burning coal. I stood between two worlds: on one side Jews were burning, and on this side Poles were standing without the slightest sympathy, heartless, laughing, pointing at the burning Jew and saying, “Niech sie smaln kobry!” (Let the poisonous snakes burn)…[23]

The last fighters of the ghetto threw themselves into the flames of the burning buildings. Here and there fighting was still continuing in the bunkers, a last stand against the German murderers.

The Poles laugh…

There was a lot of talk on the Aryan side about the uprising. The Poles wondered at the courage of the Jews. Many tanks were incinerated. Hundreds of dead Germans were brought out of the ghetto, many of them still gasping. As the Jews knew that everything was lost in any case, they at least let the Germans suffer. I stood like all the Gentile young people, watching everything. My heart was overflowing with pain, and I was often about to make an end to this game. I felt it could not go on like this. I couldn't look another Pole in the face, couldn't understand how they could stand so indifferently when people were burning up. One couldn't stand there and laugh even if animals were burning. And I'm living among them. I felt like scolding them,

[Column 177]

tricking them, taking revenge. I was almost ready to do this, and always carried a capsule of potassium cyanide on me. But then I remembered my nearest family as well as friends from the hideout. What would happen to them? I went on walking and sobbing. Once again, I hid the cyanide capsule away.

The ghetto was gradually cleaned out. I kept seeing the cemetery. All of us survived, but our courage was gone, though the urge to live was strong. After the uprising, spying on the Aryan side increased. I would see the Gestapo leading out Jews who were as pale as death, having been discovered in their hideouts. I would buy food far from the hideout, so no one would notice me buying so much.

The consolation of potassium cyanide

We, too, often had the Gestapo come to our apartment. They made the rounds, looking for arms held by the AK, the Home Army (Armia Krajowa). They even moved the small cabinet that served as the door to our hideout. But I was able to act confident and start to distract them. After they left without the slightest suspicion and I went into the hideout, our people were half–fainting. Their beating hearts were noticeable under the clothes. My brother stood glued to his little son, saying deathbed prayers. Even when I was inside, I couldn't pry the child away from his father. Once, coming back from the street, I suddenly saw a bunch of people in front of the courtyard. My heart begins to beat faster. But I control myself, not wanting to ask anything, and prick up my ears. I catch a few words: the Gestapo is looking for Jews. I decided that the moment I see our folks being led out, I'll run and cling to them. First of all, I had just gotten a larger amount of potassium cyanide, enough for everyone. Secondly, in any case I couldn't live without my brother, my last comfort. Night fell and everything became invisible. I approach my apartment. Suddenly, shots and explosions are heard. The Germans discovered a bunker at 14 Nowowiniarska, and were fighting. The next day I heard that many Germans had been killed. Many Jews had taken poison, not wanting to fall into the hands of the Germans. I felt the ground burning under us. I wish I knew of another hideout where I could take them. But where? I decide to search for someone I knew from the ghetto. He used to visit my friend, with whom he was in love. He was the head of the finance department,

[Column 178]

and knew her from before the war, when he would come to collect money. My brother knew him as well, and now tells me that he's working in the finance office again, in Section 11. I immediately go looking for him, but not without fear, because who knows what he's like now? But thinking too much is not a good idea. I go and see him, on the stairs. I greet him, but he looks at me as if he had never seen me. I start to ask him something, but he answers all my questions evasively. I can already see myself on the other side of the door. Starting to leave, I catch sight of his Jewish woman, his secretary. She recognizes me right away. Quietly, we go into another room, and fall into each other's arms, silently, without a word. Now the department head also comes in and – as I found out later – immediately recognizes me. But he was thinking like me, that I might have come to spy on him. Such things also happened. Now we breathed more easily. They visited us in the courtyard where we lived, and he became known as my relative. Everyone had a bit more respect for me, because of his position. I went to visit them as well, and we made an agreement: if one of our hideouts was discovered, we would move to the other hideout. He had prepared a hideout for her family but hadn't yet managed to move them in. He told me that the tram inspector was also hiding a Jew, and I made the same agreement with him. I often invite them on their holidays; they pretend to get drunk and sing loudly for all the neighbors to hear, “Bóg się rodzi!” (“God is born”).[24] I feel less threatened, and much more secure near them. The inspector was also in love with a Jewish girl, and helped a lot, thanks to her.

A cough can betray

Yet the days drag on like years, let alone the nights. Each night, one of us keeps watch, to keep us aware of anything that happens. Deep sleep can sometimes give us away, but one always hopes for better times. However, it only grows worse rather than better. The physician in my hideout falls ill and instructs me to bring various medicines. His cough grows louder, and we're afraid that it will betray us. He needs a doctor, and explains that somewhere around here there is a doctor with whom he went to medical school, and with whom he is on very good terms, as he helped him a lot. I find the doctor and tell him that Lutek Grozberg is in my hideout. Of course, the doctor considers me definitely Polish. He thinks that I'm hiding Lutek because he is my lover; there were many such cases. Only in this way

[Column 179]

could Christians save Jews. At first, he was afraid to come to my place. He finally made his decision, and came. He examined the sick man, and established that his lungs were not in good shape.

Grozberg had to put on makeup, and at twilight we took the risk of bringing him to an x–ray specialist. He looked like a complete Christian, and his expression was even more convincing that that of Christians.

But his dejection could have given him away. They took an x–ray, which showed that one lung was very cloudy. For a while, he gave himself injections into the vein with my help. Later, he taught me how to do it. However, his condition did not improve; on the contrary, it worsened. The airless hideout had a bad effect on him. He says he needs to atrophy one lung.[25] How can we do this? The news has a bad effect on everyone. We have come to love him. He would hold everyone spellbound for hours with his stories and conversations about medicine and surgery, as if he wanted to turn us all into physicians. We learned a lot from him. And now he needs to be moved into a separate room, so that the others won't be infected. What do we do if someone comes in? After all, inspections can occur again. His cough might give us away even in the hideout. He knew all this better than we did. Once, he called me over, showing me his most recent x–ray. “Do you see this? The second lung is also three–quarters infected. I have three weeks of life left, at the most. What will happen to you all if I die here?” He goes on to say, “If you don't get me potassium cyanide, you bear all the responsibility!”

Taking his own life

I can't listen any more. I feel the house spinning around me. He realizes that I'm no use to him and asks me to bring his doctor again. This time the doctor came at 1:00 a.m., and performed surgery on him; this surgery was widely discussed later. He wanted to help Lutek, but it was no longer possible. He brought him back, and Lutek sank into his thoughts, never once smiling. Actually, from the looks of him no one would say he was so ill: he was tall and broad–shouldered, a young man like a pine tree. Once, coming back from the street, I go to the cabinet, move it aside, and hand them a newspaper, as always. Suddenly, I hear noise at the door. Frightened, I move the cabinet back and glance at the door. I see Lutek

[Column 180]

running out. I'm afraid to run after him, but I see through the window that he is dressed and neatly combed. I go into his room and find this letter, snatch it up and read: “I received this poison from my friend, the doctor. Both of us are certain that my life is ending anyway. I feel this very strongly. I don't want to place you in any danger. That is why I am doing it far away from the house. Be well, and may you live to see freedom, may you live to take revenge, for everyone as well as for me. Be strong. Don't lose hope. I part from you forever. Yours, Lutek Grozberg.”

I run out, search through some streets, but there is no trace of him. The next morning I grab the newspaper; you can often read that a dead person has been found, with no documents. We would immediately understand that to be a Jew. This time, there was nothing in the paper. We suspected that Lutek had gone to the Vistula, taken the poison and flung himself into the water, so as not to fall into the hands of the murderers even when dead.[26] In other cases of suicide, the Germans always wanted to find out where the deceased had hidden. They would lock down entire streets and carry out inspections. Knowing Lutek, that is what we surmised, but we could not be sure.

The house became hollow. I read Jan Kochanowski's elegies.[27]

Twelve Germans for One Jew

I see a crowd gathered on Dluga Street and Krasinski Square. The Germans have pasted proclamations ordering all the Jews still hiding on the Aryan side to report to the hotel on Dluga: twelve German prisoners would be exchanged for one Jew. Those who registered would receive special documents, would be able to move around the streets freely, and could take with them anything they wanted. It worked. There was movement on the streets. Jews started to appear, paying much money in order to be the first to register.

A policeman came in suddenly and gave me a note in Yiddish. I was sure this was some kind of provocation; but as I had gotten used to keeping a level head at the worst times, I told him it was a mistake. He doesn't answer, leaves the note on the table, and runs off. I pick up the note, my hands still shaking, and read that my brother's friend, someone from Warsaw named Kulberd, had already registered (he and his wife had hidden with the policeman in return for a large sum of money). He writes telling us to hurry to the hotel as fast as possible, because they would run out of spots. As to money, he writes, we need not worry.

[Column 181]

Oh, how we want to believe, and how easily we are deceived

My brother believed this was a great deception, but Vaysblat and his sister would not change their minds, and went. By now, I was also curious, and went over there. I walk into what looks like a real paradise. Jews were embracing each other happily, rushing along the Warsaw streets to tailors' shops and ordering the most beautiful clothes, And Brand, the bane of Warsaw, arrives, pats Jewish children and gives them chocolate.[28] No one imagines that this could be another one of the murderers' tricks. Some who register could easily have survived the catastrophe: lawyers, intellectuals, and the richest who were still on the Aryan side. But when I walked only a few steps away I saw Gestapo police in parked trucks. Everyone was being taken under guard onto trucks. I run away quickly so as not to be noticed. I came home late at night, barely alive. The next day, the whole city was talking about how despicably the Jews had been tricked. Some had tried to hide at the last minute, but had been caught and immediately taken away to the Pawiak prison, where they were shot. The walls of the municipal toilets now bore inscriptions by various underground organizations warning the Jews not to be tricked any longer, and reporting that all the Jews en route to Hannover had been thrown into the sea.[29] Earlier, they had been forced to write letters to their relatives.

The Russians are nearing, the Polish uprising

I stayed at home for several days after this disaster. I was afraid that someone would recognize me on the street. This lasted until I seemed to fall into a trance again, and went outdoors. Three persons were now missing from my apartment, and it became more and more gloomy. The days dragged on again like years without end, without hope. There was only one thought in everyone's mind: How will it end? There are rumors that the Russians are approaching. Their cannons can be heard clearly. The Poles are overcome by panic. Many pack up and leave. People say that the Germans will not surrender Warsaw easily; that they will destroy the city and burn it when they need to retreat. But what can we do if this happens?[30] The only thing to do is to wait.

It was 4 p.m. on August 1, 1944, when all the sirens in town suddenly sounded a signal. It was the signal to start the uprising of the Poles against the Germans. The Germans knew ahead of time, and interfered, so that no one could stay at their post. Nevertheless, barricades were set up on the streets. For three days, the Poles

[Column 182]

dominated the situation. They hung Polish flags all over Staro Miasto.[31] Enthusiasm was great. People yelled, “We ourselves will liberate Warsaw!” We were also in a good mood. We believed that we'd already been rescued. But this mood did not last long. All of Warsaw soon began to burn, just as the Poles had predicted. The fire was coming closer to our apartment. The third courtyard from us was already on fire. Suddenly a fire–bomb fell, and ripped off the corner of our house as well. This was the worst. We had to leave. We ran into the cellars. The experienced anti–Semites immediately recognized us as Jews. I see myself being pointed out: this Halina Wisniewska is the one who hid all the Zhids.[32]

Forget about the bombs, remember the Zhids It's remarkable: bombs are raining down, many people are dead, life hangs by a hair, and they're still thinking only about the zhids! Most are yelling for the zhids to come out. Where can we go? You can't poke your head out, bombs and grenades are falling all around. The noise alone is knocking people over and swaying buildings. My brother Yisroel considers this and decides to join the ranks of the fighting Poles and take revenge on the murderers. He happened to meet up with members of the AK, who had long sought such a victim. They send him to the location with the heaviest fire. I beg him to stay, but nothing can stop him. However, many soldiers that had been beaten back from their positions could no longer go back. The Old City was still fighting.

Yechezkel Vaynberg offers his entire fortune for a grave

Bombs and hand grenades hail down everywhere. I peek out, and see many dead bodies on the ground. In their midst, a person stands next to a wall and looks up at the sky. I became very suspicious. I take another look: ragged, abstracted, filthy, he stands sunk in thought, not bothered by the bombs. Looking at him, his face seems familiar. I think hard, and remember; I need to ask him. I run over and ask quietly, so as not to be overheard, “Mr. Vaynberg?” He screams shrilly, “Co, snowu pieniądze?!” (“What, money again?!). Many Gentile girls had gotten money from him in this way, and he thought that this was the same. I run away so as not be to be overheard. But I see that he's sure to be hit by a bomb or a grenade. I turn fatalistic, and decide to tell him who I am. Now I'm sure that it's Khaskl Vaynberg (now living in Australia).

[Column 183]

I move towards him, saying, “I'm an Akerman,” and wink at him to join me. I take him into a sub–cellar, where my people were sitting separately from the Christians. He knows everyone and they know him. He takes off a women's belt with gold pieces and gold watches sewn in; turning to me, he says, “You take this, you're sure to survive. I, however, won't get out of here alive, and you'll have enough money to bury me so that people will know where I lie.” Meir Dantziker now calls out: “ I have an idea. There are no living beings in the ghetto any more. Should we look for a hideout there? And you, Khaskl, put the belt on again. The money might be useful.” “And I have enough of my own,” I tell Khaskl.

Without thinking too long, they went into the ghetto. The women stayed behind. They found a hideout under a four–storey building in which we had previously hidden. However, it was almost filled in; it was barely impossible to crawl inside. My brother actually came back that night. He said that he couldn't stay there.

My dream foretells my brother's death

On the way, they met two Jewish fighters who had been in the Pawiak prison the whole time and were now also looking for a hideout. These were Dovid Fogelman, and a guy named Jacek (now living in Israel). They all burrowed in like rats. There is a sudden commotion again: the courtyard where we live is on fire. My brother grabs two buckets and runs to help. Night falls, and he isn't back. Exhausted, I fall asleep. I dream that I've lost a tooth. I've never thought about it, but I heard Christians say that such a dream means the death of a family member. I wake up, look around, and decide that I'll go look for him as soon as it's light.

I rush around under a hail of bullets, searching for him. As I'm running, I cross a barricade into a German–held area. Once I realize where I am, I rush back. To this day, I can't understand why they didn't shoot at me. Maybe they didn't want to waste a bullet. My sister–in–law and Chaim'l were waiting for me with eyes swollen. They thought I was dead. They can't exist without me, even for a minute. But I can't sit here. My beloved brother, my only consolation, for whom I did so much, where is he? I can't live without him, in any case. And I run back. I gave an AK member 20 gold dollars to help me search. He brought me

[Column 184]

the terrible news that my brother was no longer alive! He'd been shot by a Pole, a member of the AK, an anti–Semite, who had been in the cellar with us from the beginning and had said that the Jews needed to leave. He'd waited for my brother outside, pretended to arrest him, and then shot him. I wanted to at least find out where his dead body lay, but they had started to watch me as well. Meanwhile the Germans were approaching. It was chaos. They came up with a tank and demanded that everyone surrender, because they were going to tear down the building. Everyone slowly came out, and surrendered.

I become a national Polish heroine

We go as well. However, as young people were told to walk separately, I must leave my group. Meanwhile, in the confusion, no one recognizes them. But what will happen later? I paid an elderly Christian woman to take my Chaim'l with her, and she agreed.

|

|

|

|

They take us to the train. We ride as far as Pruszkow, a transfer camp near Warsaw. From there, those who are capable will be sent to various camps. Christians come from the surrounding towns to help those wounded in the uprising, and they are scattered among the peasants. I stand despondently, waiting my turn. Suddenly one of those who came to help the wounded comes up to me and whispers, “Go into the toilet.” I don't understand, but I go. A nurse waits there. She changes my clothes, and together we carry out a half–dead man. Someone else was already waiting and took me along with the severely wounded man. He took us to Brwinow; He took me to his home, and the wounded man was sent to a peasant in the village. I soon realize that I am in the house of the regional chief of the AK. They

[Column 185]

intended to save as many as possible of the young fighters, the best of Warsaw. So I became one of the first female Polish patriots to be rescued.

They start to interrogate me. However, I still don't grasp what has happened to me. I can't focus my thoughts in order to answer them. I ask them if I can rest a bit, and say I'll tell them everything after a nap. They agree. Now that I am alone, I try to orient myself and think about what to tell them about myself. Later, I tell them which group I belonged to. As one of those who fought to the very last minute, I become a national heroine and everyone looks at me with great respect. As a resident in the home of the AK commander, I am invited to all the secret meetings. People take my remarks into account, and I'm courted by the best and richest members of the organization. I wonder at the fact that, despite all my experiences, everyone compliments me on my looks. This was a bit of pleasure in the midst of my sorrow, a kind of gift from God. But my heart constantly wept over my unfortunate brother, and I couldn't stop thinking about what might be happening to Chaim'l.

Meanwhile, Warsaw had been cleansed of people. The notice boards carried German announcements of a death sentence for anyone alive in Warsaw. Travel from one town to another is forbidden. However, as the AK officer works in Żyrardow as the leader of the local tailoring shops, I decide to go with him, on the chance that I'll meet my Chaim'l somewhere. When I travel with him, I am not questioned. Apparently, everyone knows him. Actually, I do meet the Christian woman who took Chaim'l. She demands money from me, as much as possible. What should I do? I make a note of her address. She lives not far from us. I give her my address, and promise to bring money as soon as I can. In the meantime, I learn that an office in Zyrardow gives privileged persons passes for Warsaw, to rescue anything important left behind in the cellars.

I search for Khayiml, the buried money, and my dead brother

I don't think too long, and go to the office. I tell them that I had left a sewing machine with an aunt in a cellar in Stare Miesto, and have no way to make a living without it. He tests me, asks me to sew something. Not only do I sew, but I also cut out a pair of trousers for his son. He claps me on the shoulder and says, “So young and already such an expert!” I have the pass in my hand a few minutes later,

[Column 186]

signed by the highest Gestapo officers. I am one of the privileged. They provide us with a truck and several German soldiers, who are ordered to take us wherever they are told. We leave at around 4 in the morning, along with six other men. Somewhere, a few grenades explode. But the soldiers tell us that things are the worst in the old city, and they will give me ten new sewing machines as long as we don't go there. But I need to go there. I buried a bit of money there; besides, I think I might find my brother's dead body. I refuse, telling them that I must find my machine. They are forced to go, because those are their orders. When we arrive, grenade explosions are heard often. The soldiers scatter and hide in the grass. I use this chance, find the spot, and quickly dig out the money. They yell to me from their hiding spots, “Faster! Faster!” Meanwhile, I'm already carrying a sewing machine. They come and help me, loading up the truck with goods that I don't even think of. They bring the goods home for each one, even bringing them indoors. Then, I ask them to sign, confirming that they fulfilled the orders. I hand over the goods to my host, who sells them for necessities.

Now I start to work on a plan to bring my Chaim'l here. I tell them the following story: during the war, a lost child came to me, whose parents had certainly been killed in the uprising. I took care of this child the whole time, until we had to part. Maybe, I tell them, I'm alive because of this good deed. Now I've found out where he is, and would like to take him, if you have no objection. The AK officer and his wife immediately agreed; but I was afraid of his wife's sister, who lived with them. She was an old, unmarried, repulsive creature, a freak of nature. She constantly cursed the Jews: “Niech sim tam smarza!” (Let them fry).

Chaim'l has forgotten Yiddish–I am calmed

Paying her no attention, I wrote to Chaimls' Christian woman. She shows up the next day and tells me that the child is waiting by the river. I had clothes ready for him, and immediately went there. When I saw the child, I was shocked: wild hair, dirty, as though he had never been washed. I hide under a nearby bush and wash him, changing all his clothes. But what can I do with such a shaggy child? Where can I go? He'll immediately look suspicious. But I have no choice. He can't go like that.

[Column 187]

|

|

|

|

I take him to the city outskirts. But the whole town is no bigger than a yawn. As I come in, the barber winks at me. I shudder, but pretend to ignore it. He cuts Chaiml's hair. I shove a handful of money at him, and leave. I change direction, so as not to take the same route, and keep looking around to make sure that no one is following me. Now the child looks completely different. I look at him: Won't he arouse suspicion? His complexion is dark. Luckily, he speaks a fine Polish, and has almost completely forgotten Yiddish. That calms me down a bit. On the way “home” I teach him what to say and who he is. I buy him a pretty flower bouquet. When he comes in, he kisses everyone's hand. No one had the slightest suspicion and they accepted everything I told them. However, two Christian girls from the neighboring courtyard spend too much time talking with me about the child, which worries me, although I'm on good terms with them. We always go to church together, but they go on saying that I shouldn't keep him with me. Only one thing consoles me: the Christian with whom I live won't say anything. Their economic situation is bad, and the household depends almost completely on my help.

[Column 188]

The Germans often come around to seize people for work, but all we need to do is to hide under the door, and they would leave. They never searched seriously here, and Heniek (Chaim'l) would sit at the table calmly reading or writing, as though nothing was happening.[33] They never even asked who the child was, because if the Poles didn't point out Jews, the Germans couldn't recognize them.

I spy on the Ukrainian family

Meanwhile, we have a meeting on the following Sunday.[34] The Ukrainians behaved very badly during the Polish uprising (the Jewish uprising was not even mentioned), and all the Poles hate them. The neighboring Ukrainian family is suspected of having collaborated. The majority voted to assassinate them in order to clear them out of the way. It was a family of four, not settled here for long. I would often have conversations with them. I was secretly sent by “my” AK organization to find out where they came from and where they had been during the uprising. In the course of our conversations, I slowly came to like them, and I felt that they weren't indifferent to me. I began to feel bad about their fate. But what can I do? I lost much sleep over this.

The night of the assassination was approaching. After battling with myself, I decided to tell them. I'm sure no one will suspect me. I go there at lunchtime and look around thoroughly to make sure there's no one on the street. I start a conversation with them, asking why the Ukrainians behaved so badly during the uprising. They tell me that they took no part in the whole thing. I tell them that the whole flock suffers because of a single scabby sheep.

I betray my organization

I tell them to be wary, because we will take revenge on them all. They ask, “What do you mean, ‘wary’? Where can we go? After all, we'll be surrounded by Poles everywhere.” At that point I say, “If you swear, hand on heart, that you'll do everything I tell you to do, I'll tell you something.” They became very frightened. They all stared at me. “Tell us,” they say, “we'll do everything you say.” I tell them that they've been sentenced to death. At first, they thought I was spying on them, and said they weren't afraid. I finally convinced them. As I was experienced in such matters, I taught them what to do: set a pot of meat on to cook, place a bottle of brandy on the table, start to change the bedding, so that it would look as though they

[Column 189]

had just gone out somewhere. I told them not to take anything with them, as they might still be spied on. At around 10 p.m., when it was very dark, those who were under orders entered the Ukrainians' house. The next morning they reported that the Ukrainians had apparently suspected something and had left by the back door. Alternatively, they might have been out in the street, and, noticing something, never came back. They said that the household seemed to be in the midst of normal activity, and gave a precise description of the way the house looked. Thank God, I thought, that everything went well. I never saw these people again.

Every cannon shot is balm to the soul

However, more problems are in store: Chaim'l is playing outside with the Christian boys. They start fighting over something, and one yells “Zhid slob.” Another kid asks, “What zhid?” The neighbors, who are hearing all this, start whispering to each other; the rumor reaches the ears of my landlady's disgusting sister. She tells me that, first of all, I shouldn't take him to church, because the sin would be mine… What do I do now? The Russian cannon barrage strengthens, and each shot is balm to my soul. To be murdered now, of all times? The only surviving child of my large family! I call him aside and threaten him seriously never to play with the Christian boys again. I won't tell him why. I think he doesn't remember being a Jew at all, as he says the Christian bedtime prayer whether anyone is there or not.I live in constant fear. Everyone in the house tells me that he might be Jewish. But I convince them that it's impossible, ridiculous. How would a Jew know this prayer?

Our conversation is interrupted by a sudden uproar. We run to the window – people crowd around. One person screams, “Sowieckie tanki na szosie!” (“Soviet tanks are on the avenue!”). I think, “It's probably a new trick to try me out.” I stay calm, as if it's not meant for me. My housemates run downstairs. I run as well. I hear the order: no one should run to watch them coming, no one should give them any water, even if they demand it.

Chaim'l on a Russian tank

But my Chaim'l is already running – who cares about orders. I can't hold him back, he's gone. Before I can go back into the house, my landlord runs in, upset, yelling: “Miss Halina! We're lost! With my own eyes, I

[Column 190]

saw Heniek sitting on the front of a tank, wearing a Russian cap!” I was completely stunned. How can frost be crackling underfoot again? Icicles might soon appear. A Jew – but I can't see anyone. Dear God, I think, are we the only ones left?

Germans. Panicking wildly. Running. Naked. Barefoot. Frost snaps under feet. Icicles hang from their noses. Many run to hide in the cemetery. What a joy to look at them! They run back and forth, as though possessed. I sneak away from my people, so as not to be seen. Run along the Brwinow road. The valleys are heaped with naked Germans, many with their intestines ripped out. But I can't afford to lose my wits now either. I must go back to my house. Chaim'l also comes back. Everyone hugs him. He doesn't answer questions. Bows his head and is silent. I'm still not sure, don't believe what I see yet. I tell him, “What will we do if the Russians withdraw again, as in Warsaw? We can't stay here any more because of you.” He answers, “I'm going back to them right now. If they withdraw, I'll go with them.”

Night fell quickly this time. The streets are tumultuous. Many people are preparing to flee from the Russians. And I grow even sadder. There's nowhere to go. No Jews. Hundreds of thoughts race through my mind in a single second. Maybe this is the time to take the poison? I can't stay among non–Jews any more, it is unbearable.

The Russians in Warsaw. Jews with Jews

The next day, my “girlfriend” from the A.K. comes in from the house next door and tells me, smiling ironically, that people are waiting outside for some reason. They're asking for Halina Wisniewska. I didn't want to go out. I was certain that they'll lure me out and then shoot me because of Chaim'l. But I go anyway. Dumbfounded, I stand still when I see Meir Dantziker and Khaskl Vaynberg standing there. Meir has a nose like that of a thousand Jews; he's recognizable as a Jew from a mile away. They want to hug and kiss me, but I keep my distance. I tell the Christian woman that these are my former neighbors, who heard that I'm here and have come to ask for help. I wink to them, signalling them to leave and that I'll follow.

I go out of the city with them. They tell me how they survived in the ghetto, in holes, living with the rats, and how they found out about me. They'll be bringing a wagon soon, to take Khayiml and myself to Warsaw. They've found a place in an untorched house, and brought flour they had hidden in a hideout.

[Column 191]

We grab the rusks that Meir prepared. There, I meet Dovid Fogelman, who had also hidden with us. They tell us how the Russians suspected the presence of people in the ghetto when they came, and, thinking that they were Germans, wanted to hurl grenades in. Those in the hideout preferred to be killed rather than to fall alive into German hands. But one of them mustered his courage and came out. The powerful explosions aroused his suspicions. The Russians, however, saw a wild man. When the first survivor saw Russians, he was overcome by tears and started screaming. The others in the cellar thought that he was being beaten, and, without thinking too much, came out to help him and take their last revenge. When the Russians saw all four “wild men,” they were bewildered and wanted to shoot. Our folks yelled,

“We're Jews!”

But the Russians didn't believe this, and yelled, “Hands up!” taking aim. One of the Jews yelled:

“Shma Yisro'el!”[35]

Apparently, there was a Jew among the Russians. Although he already had a Russian wife, he remembered those two words from his father. Agitated, he ordered the rifles to be lowered. He ran over to the Jews, whom he hugged and kissed. The others stood as if petrified. They soon brought over one of their barbers, as well as complete sets of clothing. They took vodka out of their pockets, and drank a “Le–Chayim” toast with the Jews.[36] The Jewish soldier explained that the tableau had moved him very much, and that he would start to be a real Jew. He also wrote a letter to his two children in Russia, who had no idea that their father was Jewish, explaining who they were and what they should remain.

Christian girls–members of Po'ale Zion…

We slowly started to feel like real people again. I see Jews again. The first one I met was Dr. Adolf Berman (living in Israel). I knew him before the war, when he would come to Kurow and give lectures on psychology. He took me to a place that was a meeting point for Jews, and also showed me a small library comprised of collected Jewish books.[37] Suddenly, I see two Christian girls from Brwinow whom I know well. They were the ones who dissuaded me from bringing my Chaim'l here, and I was frightened. “What are you doing here?” I ask them, surprised. They answer me with the same question. But when they hear me speaking Yiddish, they come over, kiss me, and break into tears. We hug

[Column 192]

for a long time. Then another old acquaintance comes up – my former teacher from before the war, from Lublin, Dr. Shtokfish (now in Israel). Oh, I think, if Hitler could see how Jews outlived him, he'll die again! His prophecy that if he saw a Jew in 1945 he would take off his hat in respect did not come true.[38] My two “Christians” and I, who lived through such tough days in Brwinow without being aware of each other, now drank with a real Jewish “Le–Chayim.”

Back in Kurow

Now that Jews were around, business slowly started up. I become aware that my cousin Arn Rubinshteyn is in Kurow. I decide to go there at the first opportunity. I want to be in my home town again, after thinking that I'd never see it again. My dreams are now coming true. I had the feeling that I would meet all my family members and dear friends there. But I left even faster than I traveled there. There are no more Jews in Kurow. All of Kurow is a cemetery. I recognize nothing. Our house, where I spent my childhood and youth, together with my parents, sisters, brothers, beloved neighbors, girlfriends – where did it all go? I don't even recognize the place. I want to run to the old, familiar cemetery, to cry my heart out. All I find is a plowed–up field, with cows grazing. Even the Lublin road, up to the post office, is unrecognizable. I can make out a bit of greenery in some spots, but the rest is empty, as though it had never held any life. Only the post office and the Polish homes remained.

The Poles once again…

I went into the post office, and saw the same cashier and clerk working there, my former classmates. They hinted that it would be better if I didn't come to Kurow any more. I understood the hints. I knew that the AK had received these orders from London, “Dobic resztki zydow” (“Kill the rest of the Jews”).[39] They carried out this order very faithfully. I went back to Warsaw, but was chased out of there as well. I went back to Kurow, fleeing back and forth insanely. This time I joined two other families, or almost three, who were living together. They were Levi, the son of Yankev the butcher, and another Russian–born Jew, as well as my cousin Arn Rubinshteyn. They lived as a collective. Arn supplied them with flour from his surviving mill., and someone else was starting to dealing in meat. But there was great fear. Everyone went to bed afraid. Once, sleeping at the butcher's,

[Column 193]

there was a rapping at the window at 2 a.m. A voice called out in Russian, “Open up, we only need to inspect documents.” But it was clear from their accent that they weren't Russians. Our hearts stopped with dread. No one doubted that these were Poles from the AK. “We're lost!” one of us said. When we didn't respond, we heard a yell, this time in Polish: “Open up, or we'll throw in grenades!”

Give them money and life

I climb up to the attic and grab my bit of money. Jumping down from the back, I fall right into their hands. It is very dark. They blindfold me and lead me back into the house. All the Jews are standing, shivering in their shirts.

They identify me on the basis of my outdated Polish papers. “What are you doing here, Halina Wisniewska, among Jews?' asks the leader, sarcastically. I tell him that when I came to town from Warsaw very late, I saw a light on here and asked to be allowed to spend the night. They order me to stand aside and start in on the butcher. A 15–year old boy hits him three times and orders him to hand over his money immediately, or everyone will be shot. They take all his money and want to lead him out. At this point, I can't restrain myself, and start talking to the commander: “As I have heard that you've saved many of ‘us’”… the door opens and I hear a voice, “Why, this is our fellow student Genia.” I am completely baffled now. Gone through so many experiences, I think, lived to see liberation, and now–here–to be shot!

The butcher's youngest son (now in Israel) begs them: “Let me, at least live; I'm the youngest.” Meanwhile, the criminals have packed up everything in the house and the attic, including the last bit of money that I saved! They hear a noise from outside, blow out the light, and run away. Malka Shtern (now in Israel), deathly afraid, crawls under the bed. They apparently notice this from behind the door, and turn back. Everything starts over again: If we don't give them the money, we'll all be shot. My explanation, that she was traumatized by the Germans and still hides automatically, is useless. I move the bed, and show them that there's nothing there.

[Column 194]

They search between the floorboards. Meanwhile, dawn has started to break. They leave, telling us not to move. Everyone was naked, wearing only a shirt. We sat that way in the cold, until morning; but thank God, everyone survived. I decide never to go to Kurow again, and tell the others to flee this place. But Levi says that he needs to get the money back first. I later found out that they had shot him in Kurow.

To the Land of Israel!

Back in Warsaw, someone named Mielnik (now in Israel) invited me to a party. He doesn't tell me the reason for the occasion. But I go, in order to be in the company of Jews. Once I get there, I meet Dr. Feldshu (Ben–Shem, living in Israel) among the couples at the set tables. There are talks, food, drinks, and a few hours later everyone leaves. I find out, a few weeks later, that the party is in honor of Dr. Feldshu's departure for Israel. After he leaves, there is more and more talk of people emigrating to Israel. Everyone you talk to is planning to go. I, too, am drawn there. I can't find my place here. The air is stifling. I want to flee from Poland, and no longer walk on soil that is saturated with Jewish blood and surrounded by sheer haters. The only thing left in Poland is an enormous Jewish cemetery. No, not even that. You can't even visit your ancestors' graves. I've spent enough time here because I had to. Now I no longer need to do so.

|

|

|

|

I found a companion to share my life with. We got married in Lodz, and left the very next day, travelling with many other Jews to the land of our dreams, the Land of Israel.

We travelled for six months. We met the Jewish Brigade, whose members were

[Column 195]

very devoted to us, supplied us with the very best, and housed us in a wonderful Italian villa in Florence.[40] A true rest home, where we were surrounded by maternal devotion. They obtained immigration certificates for us, and we came to the Land of Israel on board the ship “Princess Catterling.”[41]

The saved “Ukrainians”

P. S.

In Lublin after the war I heard a distant shout, “Miss Halina!” I see three people running after me, followed by many others. They want to make me stop. The first three run up to me and embrace me tearfully,

[Column 196]

saying in Polish, “You saved our lives!” Meanwhile, I hear them telling a few nearby Jews, “This Christian woman saved us from death!” The minute I hear them speaking Yiddish, I realize that this is the Ukrainian family. I hugged them, crying, “ But I am Jewish!” I cannot describe the scene. Everyone around started crying like small children along with us. Other people gathered. I was getting ready to leave Poland and couldn't spend time with them. We parted, wishing each other a speedy meeting in the Land of Israel. Unfortunately, I don't know what happened to them afterwards.

|

|

|

Zahava–Golda, her sister (in the centre) Reizel Rochman, Givatayim, Israel (left) |

Translator's footnotes:

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kurów, Poland

Kurów, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 11 Aug 2020 by JH