[Page 105]

A Jewish Community in the Diaspora

By Manus Goldenberg (Israel)

Translated by Mindle Gross and Murray Kaplan

I see Kremenets before my eyes as if it were alive. Here's the long main street, the little shops that extend along its length closed and locked. It's a summer Sabbath morning. Jews in holiday dress are going to the synagogue and study halls. Silence and rest envelop everything and everyone. There is no sound of wheels turning, no clip–clop of horses' hooves. No one drives away and no one arrives on a Jewish Sabbath or holy day in this particular city.

When the Sabbath or holy day begins to wane, how crowded the street becomes; it's flooded by a holiday mass of people–young and old, men and women. The Sabbath Queen is ushered out; only the sad nighttime church bell foretells the approach of the grey workweek, full of worry.

The Jewish holy day comes in quietly and leaves quietly. And the next day its followers–confusion and turmoil–appear. There are thousands of wagons, a splash of brilliant color, proud, provocative clamor. The peasants are out in large numbers, and they flood the streets, shops, and workshops. The smell of pitch and tar penetrates everywhere. There is a mixture of Jewish and gentile voices: curses and blessings, laughter and anger wrapped up in one package. Jews and gentiles negotiate in the shops, in the street, and on the wagons. The multitude crowds in, and you can't cross the area. A great strength is hidden in the hardworking gentile mass. If that strength trends peacefully, then it brings prosperity with it. If it's provoked and let loose, however, it brings ruin and devastation. And you can't predict how it will go. Every bazaar and market day is subject to deterioration into a day of disaster and loss for the Jews. Therefore, the city breathes easier when, full of weariness, the day comes to an end. The wagons disappear and the peasants disappear, like locusts that spread and disperse suddenly. Only straw and cattle dung are left in the streets and marketplace. In the city, only the Jews and their earnings are left. Quiet descends on the city again. On its main street, thousands begin to stroll slowly, and hearty conversations begin slowly in their mother tongue, that succulent Volyn Yiddish.

The city and its environs are beautiful. In the main, its houses were built long ago. They were built of wood in the picturesque old Polish style. In the middle of the city, they are crowded one on top of the other, filled and overfilled with hardworking Jews, craftsmen and marketers, whose whole world is toil and weariness. Mountains and forests surround the city, and each street and alley loses itself in forests and mountains. There are also many orchards in town. The city is completely enveloped in greenery. To the east, lofty Mount Bona appears in its full beauty, and on it sit the ruins of the old fortress, the windows of its sloping sides reflecting greenery in summer and blending with white snow in the winter. From every attic window or cellar, you can see the mountain, which sends a wave of delight to everyone. The city can be seen from the mountaintop, as though it is spread out on the palm of the hand.

A separate magic lies in the city on Sabbath eve, when candles are lit. Tens of thousands of Jewish candle lighters bejewel the still Friday night beauty.

Over the course of many generations, the people have spun many legends around these very mountains.

[Page 106]

Every stone, every cross, and every life experience revealed in wonderful stories has its beginnings in this mountain. Folks would often stroll on this mountain and stop to rest in the shadow of its parks and orchards. Each holiday had its special mountain. One of the most beautiful parks was called Hasidic Park or Hasidic Forest. People used to say that, many years ago, Hasidim customarily strolled there on Saturdays and prayed the evening prayer in a minyan. In the summertime, Jews would rent summer homes from the farmers in the mountains and go there to enjoy a couple of months with their families. The dry, rarefied mountain air and the surrounding magnificence also drew summer guests from nearby cities. All these natural features affected the city dwellers' character and made them more pleasant and agreeable.

Happy and gifted with a rich imagination, Kremenets Jews greatly enriched Jewish folklore. Everyone loved their expressions and witticisms, which were handed down from generation to generation.

Kremenets is an old city. The remains of the forts and towers on Mount Bona drew their parentage from an old fortress built in the eighth century. In the chronicles, the city is mentioned in the year 1068. The Tartars laid siege to the fortress in 1241–1255 and could not conquer it. Only much later was the fortress destroyed by Chmielnitski's hordes.

The Jewish community in Kremenets is one of the oldest in Volyn. In 1484, it was granted a Writ of Permission from the prevailing authorities and, in 1548, Queen Bona confirmed these Jewish rights. In those days, the city included 50 Jewish families. Apparently, their financial situation wasn't very good, and they were exempted from paying the state tax.

At that particular time, several Kremenets Jews petitioned the authorities to be granted the concession for city and state tax collection. The Jews estimated that the sum of money they could collect in taxes was considerably higher than what the Christian concessionaires were currently collecting. The Jewish bid was accepted. This was a factor in worsening relations between the Christian and Jewish communities. The former tax collectors filed suit in the local court, and the tax collection concession was returned to them. The Jews appealed to the king's court to overturn the judgment. This intervention was successful, and the Jews were confirmed as tax collectors.

In the distant past, at the very beginning of the Kremenets community, there were rabbis of great reputation. Among them were Rabbi Yitschak HaKohen and Rabbi Avraham Chazan, author of the law review, who died in 1510. Regarding the esteem in which this community was held, there is evidence of this from the end of the 16th and the beginning of the 17th century; and in those years, their leader was Rabbi Mordekhay Yafe, author of the well–known book Levushim (On Propriety).

Rabbi Mordekhay Yafe was born in Prague and studied in Venice, where he intensified his knowledge of classical philosophy and languages. He was asked to take the position of chief rabbi of Poland in its most enlightened Jewish epoch. He was the rabbi of Grodno and later moved to Lublin, which was then a city of rabbis and writers. The yeshivas of the Council of Three Lands were founded there. Through Rabbi Yafe's efforts, Lithuania was brought into the union of these yeshivas, and from that point on they were called the Council of Four Lands. Rabbi Yafe was the head of the Polish yeshivas and chairman of this Council's rabbinical college. Although he was a Kabbalist–a mystic–he permitted, in a limited way, the study of secular subjects. He wrote a paper on the Rambam's Guide to the Perplexed. For a time he was the chief rabbi of Lublin. At the very height of his achievements, he moved to Kremenets and was the rabbi there until the death of the MHR”L[1] of Prague, whose position he was invited to occupy.

[Page 107]

During the great peasant revolt, which has been labeled with the terrible name “the edicts of 1648–1649,” the Kremenets Jewish population was almost entirely annihilated. R' Meir, son of Rabbi Shmuel, writes this information in his book Stressful Times [Tsuk HaItim].

“Kremenets, this holy and great community, was destroyed and transformed into a swamp, and the Jews were killed without pity.” So wrote Rabbi Lipman Heler, author of commentaries on the Talmud. The author narrates these events based on the description of a witness to the frightening events that took place in Kremenets. He writes as follows:

A murderer from Chmielnitski's hordes took a scalpel from a ritual slaughterer's scalpels and slaughtered several hundred Jewish children, and he asked his companion whether this was kosher or not and threw their bodies to the dogs. Then the murderer took one of these slaughtered children and broke into the slaughterhouse,saying, “This is kosher!” He then inspected the body as you do with a goat or a lamb. Later he impaled it on a spear and carried it throughout the city streets, crying, “Who wants to buy a little goat?”

The survivors who managed to save themselves in 1648 were killed in 1649. This also happened to the Jews of Dubno, Zaslav, and the surrounding communities, except those who escaped to Kremenets. A small group of Jews appeared again to rebuild the destroyed Jewish community. They were granted permission by Casimir, king of Poland, in 1650.

The Christian residents did not agree with the renewal of a Jewish presence in this area. They created disturbances for a long time, and in 1684, Franciscan priests presented accusations against the Jews and demanded that they be driven out. This case was brought before the Tribunal of Lublin, which finally ruled that the Jews had the right to live in the city.

There is absolutely no indication of what Jewish living conditions in Kremenets were from the beginning of the 18th century to the 19th century. Here and there, spread throughout the city archives, there are weak indications, as is the case for other locations.

The Council of Four Lands records state that at a certain yeshiva, founded in 1726 in Poznan, it was decreed to make a biannual payment to a Kremenets resident or his inheritors. This was for a debt owed the man by the Council: the community also received a portion of this payment. It is a fact that at that time there were wealthy individuals in the Kremenets community. However, it is also known that the city was impoverished at the end of the 18th century.

Two large fires occurred. And when the Jewish residents ventured to rebuild their homes, Christian homeowners prevented them from doing so. Again, the Jewish right of citizenship was challenged, but this time there was a trial that awarded permission to rebuild the fire–damaged and ruined homes.

The Polish Lyceum opened in Kremenets at the beginning of the 19th century. Its founders were Tadeusz Czacki and Kollataj, both of whom stood at the very head of the historical and renowned society for building coeducation, and it was they who made the greatest efforts to establish the Lyceum as an eastern Polish center in accordance with its stature and wealth. It was just possible to convert the institution into a school of higher education. Many of the Polish personalities of that time were educated between its walls. Among them was the poet Slovatski, who was born in Kremenets. The Lyceum library held about 40,000 books, many of them rare editions. A rich botanic garden was part of the institution. Czacki dreamed of enlarging the institution. From his bylaws, the possibility of establishing a seminary for Jewish teachers there was also developed.

There is no doubt that the Lyceum greatly influenced the Jewish people who came into close contact with it. Several Jewish children in the city studied there, and there were also Jewish students from out of town.

[Page 108]

The local merchants and craftsmen cooperated with the Lyceum.

After the Polish rebellion of 1831, in which the Lyceum students took part, the Russian authorities decided to close the school and transfer all its assets to Kiev. Incidentally, the Lyceum served as a branch of Kiev University. Some of the leading personalities of the Russian educational system in those days looked askance at the Lyceum and considered it a dangerous center for underworld activity in Poland. The Lyceum was the cause of disturbances in the dream of establishing Kiev University.

In about 1830, the building of the Great Synagogue in Kremenets began, a building that would be a credit to the city. It took 15 years to build the synagogue. Many Jewish craftsman and laborers donated their work willingly and without pay. For this project, they devoted their time pro bono. The Ark of the Covenant was the work of local masters. This very synagogue–the fruit of their labor for their simple posterity–remained for the future. The seats on the entire eastern wall were reserved for the builders, and their places were inherited by their descendants, who took great pride in this.

Yitschak Ber Levinzon returned to Kremenets in 1821 and remained there permanently. He lived on the outskirts of town, in a small, humble cottage comprising one room and a cellar, which was almost always flooded. His little house remained standing until the very end, when the entire Jewish population was annihilated. The “Russian Mendelssohn” worked and operated there for 35 years. In those days, it was very difficult to access his house, because the road to his house was always very muddy, and wagon wheels would sink into the mud even in the summertime; this served to isolate him from the city. When he first settled in Kremenets, Levinzon participated in communal affairs, but the publication of his book Testimony in Israel–the very book that strengthened the Enlightenment movement in Russia (he had received 1,000 rubles from Czar Nicholas I for it)–angered the Kremenets Hasidim, who then began persecuting him. They spared him no invective. Levinzon was forced to isolate himself from the community. Every Jew that came in contact with him was also subjected to all sorts of vexations, and his name was brought to shame–he was called “Teud'ke.”[2]

Levinzon's private letters of that time were written with much bitterness, and they are a testimony to the Kremenets Jews' social and economic conditions. He writes in one of his letters,

The people of the Enlightenment are not enlightened; the scholars are not scholars; the homeowners in the main are poor and poverty–stricken. What makes them all equal is that they are all under the dark veil of the Hasidic flag. All is foolish and meaningless, and that will also be their lot. And these are the ones who preach to the people. Their poor earnings come from the sale of tobacco, which grows in the area, or from the sale of liquor. A large number of them are tailors and plain laborers, and they live by their hard toil. And when poverty prevails, then a Jew who has assets of 2,000 rubles considers himself a wealthy man and seeks honor and wishes to be an advisor.

At this time, apparently, there was a downturn in the Kremenets Jews' situation, although at the end of his writing, he admits, “And all this has occurred in the past 40 years.” His bitterness toward Kremenets residents comes to the fore in a second letter, which reveals his enmity toward the Hasidim, and this is what we read, among other things:

Everywhere, daily, I hear the poor people's cries, from our brothers the Jewish managers and leaders, and from behind me I hear a great tumult, which is aimed at the fanatical rabbis and drunkards, herds of Hasidim dancing in the streets and shouting out loud. And new rabbis in carriages have started to visit the city. One drives away, and a second one arrives and they get drunk and then do holy dances in front of the fanatical rabbis.

[Page 109]

For his intense and varied studies, Levinzon needed books on scientific research and the wisdom of Israel, which he couldn't find in the local libraries. He was bitter about this. His relief came from the Lyceum library and Tadeusz Czacki's private library. The reference libraries were open to him as well. Several Lyceum principals and their teachers came in personal contact with Levinzon. They encouraged him in his striving for Jewish productivity.

Undoubtedly, in the years in which Levinzon worked in Kremenets, he left his mark on the life of the Jewish community and many of its residents, even though he was repudiated. During those times, many esteemed guests–enlightened Jews and Christian researchers–visited Kremenets especially to see Levinzon. Heads of government also came to see him. The city's enlightened populace surrounded him, among them Gotlober[3], who settled in Kremenets to be close to him.

A Jewish writer, poet, playwright, historian, journalist and educator. He mostly wrote in Hebrew, but also wrote poetry and dramas in Yiddish. His first collection was published in 1835.

Levinzon's studies and his call to cross over to craftsmanship and agriculture found broad acceptance among the city's Jewish masses. Fifty–two families expressed their willingness to settle in one of the agricultural colonies in Kherson province.

For a long time, Levinzon exchanged letters on this matter with the Interior Department and the governor of Volyn. In the end, the Jews were granted a plot of land in Kherson province and settled there. Among the families mentioned in this correspondence, we find the names of various families from Kremenets: Basis, Fishman, Barshap, Raykis, etc. This relationship between the authorities and Levinzon, and the gifts he received from them, raised his esteem in the eyes of the plain folk. And because of this, legends arose that remained in Jewish hearts for generations to come.

In 1856, a band of masked robbers attacked Levinzon's home, at which time he was sick in bed. Among other things, they stole his box of letters, in which he kept his important correspondence, including the letter from Nicholas I in connection with the publication of his book Testimony in Israel.

It is not known who the robbers were. Some suspected that this was the work of the Hasidim, who wanted to eradicate his writings.

In 1860, Yitschak Ber Levinzon died, and a great sorrow descended upon the city. All shops were closed that day. All the residents followed his casket. His important works were carried in front of him: “Justice shall go before him.”[4] Levinzon's students came from the city's enlightened and were then the more important segment of the city. The local Lovers of Zion movement and the Association of Lovers of the Hebrew Language emerged from them. The house of Nachman Prilutski, one of Levinzon's intimates, served as a meeting place for the Lovers of the Hebrew language. His son, Tsvi Prilutski, along with Dr. Tovye Hindes and Dr. Pines, founded the Lovers of Zion movement in Kremenets. Many of the local youth and study hall Jews were drawn to this movement. In the pages of Hamelits at the end of the 19th century, many writings by Tsvi Prilutski and later by Moshe Eydelman were distributed on the ongoing Zionist activities in Kremenets, the formation of the enlightened of Kremenets under Levinzon's influence, the Jewish daughters of the Enlightenment and their proud nationalistic bearing in Christian society, and so on and so on.

When Dr. Hindes immigrated to Israel, Tsvi Prilutski published his private letters in Hamelits. The letters are on very serious subjects, and from them one can learn the initial steps toward new methods in the realm of education and work habits. Tsvi Prilutski then moved to Warsaw from Kremenets. There he produced the periodical Dos Lebn and later Moment.

[Page 110]

Throughout the years, until the very last day of its existence, the paper fought for the rights of Jews in Poland.

|

|

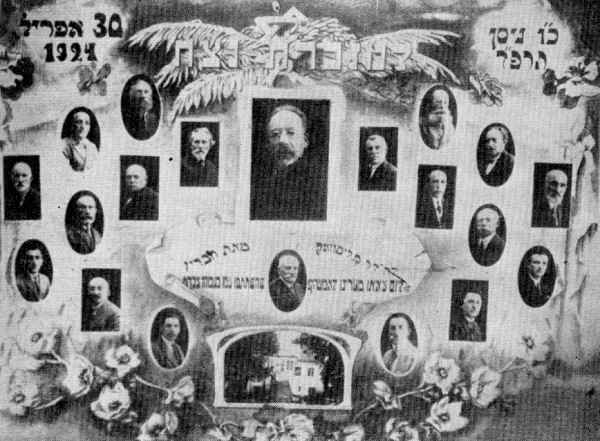

In Honor of Dr. Litvak, from North America[5]

From right to left, top: Zeyde Royt, Vaynberg, Perlmuter

Second row: M. Goldring, Dr. Sheynberg, Sikhodolier, Moshe Heydis

Bottom: Eli Landesberg and Moshe Gershteyn

Bottom right: Moshe Eydelman, Chayim Ovadies, Yitschak Poltorak, Optometrist Hindes, Ruven Goldenberg, Aharon Fridman, A. Shtern, L. Frishberg, and Shmuel Feldman

Middle: Dr. Litvak (top) and Mekhl Shumski (bottom). |

Tsvi Prilutski's son, Noach, the renowned man of letters and social activist, was brought up in Kremenets. His teacher was a student of Yitschak Ber Levinzon. Although he lived in Warsaw, Tsvi Prilutski did not sever his relationship with Kremenets, the city of his birth, where he had a family of dedicated Zionists. At the beginning of the 20th century, Dr. Pines also left Kremenets and moved to Bialystok. There he founded his eye clinic, which became famous in every corner of Russia and Poland.

These groups of activists dissolved and dispersed all over, but in the social arena back in Kremenets, fresh people appeared on the scene, and they took on the work of Zionism with particular enthusiasm. The most dedicated were Moshe Eydelman, Dr. Meir Litvak, Dr. Landesberg, Munye Dobromil, Getsel Klorfayn, and others.

The Kremenets Jews' material situation in the second half of the 19th century wasn't an especially good one. At that time, the standing of Jewish merchants elsewhere was advancing, but Kremenets city dwellers' economic life suffered.

[Page 111]

Kremenets lumber merchants didn't excel and weren't prosperous; manufacturers were almost nonexistent. The greatest potential for sales was to the area's peasants. Some engaged in the work of homebuilding. Some Jews devoted themselves to provisioning the local municipal seminary that occupied the Lyceum building. Two military regiments stationed close to the city were also a source of income for the Jews.

Understandably, news of the occurrences in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century and of the Russo–Japanese War also reached Kremenets. Several of the city's men were posted to the faraway eastern front, but they never quite made it, because enemy action halted. Only Dr. Litvak was at the front for a long time and returned as a high–ranking officer. He later published a book on his experiences at the front.

As for Dr. Litvak's personality, by the way, it is tied to several decades of Kremenets community life. He belonged to the last of the Mohicans in the family doctor category. In addition to healing the body, they also healed the soul. Although deluged with work, he still devoted most of his free time to civic activities, and there was no field of activity in which he wasn't active. He was a plain Jew of the people and remained that way to the end of his days. He was also largely accepted by the Christian population. A confirmed secularist and the best fluent Russian speaker, Dr. Litvak was the doctor and hygiene inspector for the public schools, even though there were also Christian doctors in the city. He was a fiery Zionist; he always accepted a broad spectrum of the people's work–in the synagogue and at funerals. He was especially concerned with public health. One of his aims in life was to build a monument to Yitschak Ber Levinzon. He gave much of his talent and energy to this project. When World War I broke out, he was mobilized, and he returned from the war in 1917 with the rank of general. Now, with redoubled energy he devoted himself to public service. Dr. Litvak died in 1930.

On the eve of the 1905 revolution, a strong Bundist organization formed in Kremenets. The members performed their work with great energy, but underground. They held their meetings in the mountains. Oftentimes, they were unexpectedly attacked by the police. Some propagandists and activists were punished with beatings. The youth among the local leaders of the intelligentsia joined this revolutionary movement. Some immigrated to America, and they occupied high positions in the labor movement there.

At the same time, the Labor Zionist organization was founded, which also attracted part or all of the revolutionary movement to its membership. What happened then is exactly what happened years later, when the Bundist activists joined the Communist Party after the October Revolution.

After the 1905 commotion, life in the city went along as if it were still water. It appeared as if the land had settled down, and like all provincial towns, Kremenets, too, dropped off to sleep.

Full of hope, young people turned their attention to long summers, during which Kremenets dreamed on. Its streets were empty, the regiments went out on maneuvers, studies at the schools stopped, and many local residents drove out to their summer homes.

The peasants were busy in the fields; only the storekeeper took care of his store and sighed into the empty street. Now, at this time, the machines in the tailors' street beat out their rhythm.

[Page 112]

The factories provided warm jackets by the thousands for the peasants, who were readying themselves for the winter season. And at the machines in small, lowly rooms sat sweat–soaked old and young people, who sweetened their long and trying days with heartfelt folk songs. After the summers came the winters, with market days and bazaars. These short seasons were almost the only sources of a living for Jewish residents. And winter also brought worry and headaches for many of the city's Jews. The fearsome, cold weather worked its way into their poor homes and made their lives miserable. And this is how the times changed. It appeared as if it had been this way in Kremenets from the very beginning and that it wouldn't change until the end of all generations.

But let us not forget our past in our beloved homeland.

There were Hebrew schools and a Talmud Torah in Kremenets before World War I. There was also a yeshiva, founded in 1910, and almost all the students came from tailors' families. Most Jewish children from Kremenets studied in the Jewish Russian public school under Goldfarb's leadership alone; he had studied at the rabbinical seminary in Zhitomir and was of the same generation of and a friend of Tsvi Prilutski and Hindes. He was an adherent of assimilation. He implanted his fervent love of Russian classical literature into his students as well. For many years, he remained the head of this school, and he educated generations of students, who carried his memory in their hearts with love and gratitude.

In 1904, a High School of Commerce was founded in Kremenets. The school was established almost entirely with the support of Jewish money. Superb buildings with balconies were built on the site of a grand old orchard. It had workrooms, chemistry laboratories, and a rich library, all donated. The Jewish assimilated businessman's only worry was: students …true, there were students aplenty in our city, and students came from all over the Russian region, but they were all Jewish, and according to the school statutes, which for the time were liberal enough, you could open a school only if 60 percent of the students were gentile and 40 percent were Jewish. So the Jews went out among the Christian residents (mainly poor laborers) and asked them to send their children to the school, Conversely, every Jew who wanted his son to be accepted in this business school was required to bring a gentile boy with him and even to buy him a uniform and supply him with everything he needed. In addition, the Jewish father was required to oversee the boy so that this young gentile boy would keep up with his studies and not drop out, God forbid. To achieve this, it was sometimes necessary to ply the Christian father with a good drink of whiskey. A son in business school with a shiny new uniform was a source of pride for the family. And Jews, even those who couldn't afford it, made the most strenuous efforts to give at least one son the opportunity to study at the School of Commerce. These Jewish sons made every effort to matriculate with a gold medal, and later they'd seek entry to the university, which, of course, then refused to accept them.

In 1907, Burshteyn the teacher opened a Hebrew school in Kremenets. It was called a “modern reformed” school, and it was coeducational. It wasn't easy for Burshteyn to acquire the necessary number of students, since the School of Commerce was competing for students, on the one hand, and on the other side was the traditional desire to send Jewish children to a Hebrew school. In Burshteyn's school, students were given a national Zionist education. Several students later transferred to the Mikve Israel Agricultural School in Jaffa. Almost all the students then distributed themselves among the activists in the Zionist movement. And Zionist activity before World War I was like life in general in those times–leisurely, according to custom; the annual sale of shkolim[6], shares in the bank, containers for collecting charity on Yom Kippur eve, etc., and sometimes a Zionist speaker in the study hall.

[Page 113]

In a certain private home, there was an illegal Zionist library consisting of a number of books and brochures. The chief of police, although he was a friend of the homeowner, who was a Jew, would give a warning when he had to do a house search. Then the library would be moved someplace else until a new search was required.

The Bundist and Labor Zionist activists conducted an extensive building program. Jewish literature captured the masses' imagination and won them over. And when Sh. Anski travelled from city to city throughout the Jewish Pale of Settlement with the aim of gathering Jewish folklore, he extended his visit in Kremenets. The student population gathered around him, especially those who hadn't wandered away from their language and customs there in Kremenets, and Anski simply melted with pleasure in their midst.

Life proceeded at a leisurely pace, and stillness reigned everywhere. It was the calm before the storm. And the storm drew closer. The initial clouds appeared on the horizon.

In 1913, our city acquired a cavalry regiment, which came to conduct maneuvers in the mountains, where the Austrian positions were later stationed. The first fatality of the approaching war had already fallen. He and his horse tumbled down the mountainside and were killed. The city's quiet was shattered. At the end of the summer of 1914, on a dark, humid night when the city streets were already empty, the sound of a galloping horse and rider was heard. As though thunderstruck, the latecomers were left stunned. Somebody yelled, “General mobilization,” and all the city dwellers quickly appeared in the streets. This was a “night of wakefulness” that brought us to the threshold between two eras.

In the morning, crying wives could be seen, and bearded fathers were being escorted on their way by whole families. And in a few days, city residents had already met the first gentile wagons carrying the wounded. Their bandages were soaked with blood; they were brought dirty from the front, the Austrian border. This first meeting with blood left the Jews shivering.

Stillness and quiet were literally a thing of the past. Day and night, the streets shook with long lines of wagons and squads of men marching in their brand–new uniforms. This was the Russian army marching to Brod in their successful offensive in Galicia. However, the following year, the tables turned, and endless multitudes in the worst of conditions ran in fear in the opposite direction: tired, tattered, battered, and weary soldiers. This was the great retreat, which came to a halt two kilometers from Kremenets. Here the front flared up, and the battle lasted 10 months. Artillery constantly thundered over the local people's heads. All municipal government and schools left the city. Some residents fled, and in their place, refugees arrived from surrounding towns that had been destroyed. Economic and social life was laid waste overnight. A lot of money flowed into the pockets of those who supplied the military, and this was a small group of people. Chaos and lassitude spread throughout the city. Kremenets was flooded with refugees. From every Ukrainian city, people fled from the hated Russian army. They ran in hope of a quick victory by the Austrian army, which had beleaguered the city. But the city wasn't conquered or destroyed. The surrounding mountains protected it.

On the second day of Shavuot in1916, the the Austro–Germans were defeated. The renowned Eleventh Army Corps established its headquarters in the city. Among the military sappers, drivers, and machine operators who worked at army headquarters were many workers–revolutionary movement activists–from Moscow and Petersburg.

[Page 114]

And when the February Revolution broke out, they were the first to organize meetings, which took place in a holiday atmosphere there in Kremenets. The ranks of the soldiers stationed there included Social Democrat and Socialist Revolutionary leaders in their midst, people with famous names. Also, the Bolsheviks were under the influence of that old Communist apparatchik, Krilenko, who carried on with Bolshevik propaganda in the city.

In the heat of the revolution's first days, Kremenets civic life, which so far had been asleep, awoke with a start. The Bund, Labor Zionists, and Zionist Organization came to life. Membership in all these organizations grew. A perpetual election for municipal government started up, for the community. The latter accumulated most of the workers and became known as the Red Community, which was the equivalent of election to the all–Russia Constitutional Assembly. At the convention of the Ukrainian Jews, etc., with much energy and devotion, they observed Zionist customs, raising the national flag and remaining devoted to it even in the worst days of this era.

The leaders were Dr. Binyamin Landsberg, a fiery speaker with a clear and impressive mind and an idealist and innovative societal activist who devoted his whole life to the people and the party, and took part in the stormy debates for the Zionist side, with great success; Meir Goldring, an energetic crusader with devotion to the party; Y. Shafir, who is currently living with us in the Jewish state; Gorngut, the first militia officer in Kremenets, now a resident of Haifa; and many more.

The exuberance of freedom had not yet sputtered out, and dark clouds of civil unrest began to cover the fair skies. The military became demoralized. In the marketplace, wagons full of stolen goods appeared and were sold to anyone. It had become so bad that there was a pogrom in Kremenets in December 1917. It was the work of gangs of soldiers. They ransacked shops and burned down houses, and two Jews were killed. The morning after the pogrom, the Jews organized a Jewish security force, formed from Jewish veterans who had returned from the front and still had their weapons.

The self–defense group didn't last long. The Germans, who were starting to attack Ukraine, entered the city and disbanded the group. Order was again invoked. The Jews began to wheel and deal. The Germans' heavy hand was not initially felt, but under the pressure of the Bolsheviks on the Ukrainian borders, persecutions and arrests began. Dr. Landsberg and others were arrested. They were freed in a few months. They freed the Ukrainian rebels, who had captured the city by force after a street slaughter with foreign highwaymen. At the head of the rebels were two local Jewish boys, Vaysberg and Balter.

This was the start of the era of Ukrainian independence, which was soaked in Jewish blood. Kremenets didn't suffer much from the slaughter, but the fear of death did not abate for several months. On one occasion at this particular time, when the inner forces were changing, Kremenets stood on the threshold of a large pogrom. This was in 1920. The Bolsheviks had retreated by this time and, for this reason, they shot several dozen former officers in the local population. The rebelling peasants, who fought their way into the city, were ready to vent their wrath on the Jews. But then an officer who had been miraculously saved informed them that among the slaughtered was a Jewish man named Tshatshkis. The Cheka[7] wanted to let him go, but he refused this favor and chose instead to share the fate of his comrades, the Ukrainians.

[Page 115]

The rebel chief accepted the survivor's testimony and used it on the peasantry. The rebels were satisfied with contributions and loot. At Dr. Litvak's initiative, there was an annual remembrance day in Kremenets in the Great Synagogue to honor Tshatshkis's memory.

The city's capture by the Poles and their accomplices also ended with robbery and persecutions and with the arrest of important Jewish citizens, who were thrown into concentration camps with others. With the Treaty of Riga, the city was definitively granted to Poland.

|

|

Management and residents of the Home for the Aged in Kremenets,

among them Aharon Efraim Grinshteyn (barber), aged 104. |

At the beginning of the Polish regime, all political activity in Kremenets was strictly forbidden. But after the establishment of relations with Warsaw and other centers, Jewish social and economic life reawakened. In the first elections to the Parliament, it was agreed that there would be a Jewish–Ukrainian voting bloc. Voting activity in the Jewish streets in Kremenets and its outskirts achieved great success.

Avraham Levinson, the candidate for deputy of the voting bloc then resided In Kremenets, and he was the representative for Kremenets, Dubno, and Ostrog. The local Zionists' activity in this election was the best testament to their political maturity and strong will. The election results were much better than expected. To this day, Avraham Levinson recalls with wonderment the days when he lived in Kremenets: he rates Jewish devotion to nationalism as very high.

[Page 116]

In the first decade of Poland's national independence, Kremenets enjoyed, so to speak, the most brilliant of times in many years. The city grew and spread out, business and industry developed, the quality of life increased, new institutions were born, and the old ones were broadened and renewed. The Zionist movement grew up in all its aspects and occupied beautiful new premises; its library was the largest in the city. The income to the national fund increased immeasurably. A Tarbut School (for culture) was founded, but initially struggled with restrictions from the authorities and from lack of funds. However, the school prevailed thanks to the Zionist business community's generosity.

In 1926, an ORT[8] school was built in Yitschak Ber Levinzon's name–a general school with a sewing department for girls and a locksmith shop for boys. At approximately the same time, the orphanage building was completed, the “dear child” of the philanthropist Leyb Rozental and Sofia Kremenetski, with the Burial Society's authority–in which, to a great extent, great sums of money were hidden from the public. She actually generously supported the city's philanthropic institutions. The Jewish Hospital and the Home for the Aged were increased in size and reinforced. TOZ, the Jewish institution for public health, broadened its activity and truly cared for the community's health. People's banks opened up in the city to support small businesses and craftsmen with loans, and at the same time, free loan societies became larger and stronger and increased their clientele. Jewish professional unions were established; their main issue was concern for the workers' daily wage, improved working conditions, and work in educational research. These professional unions were politically to the left in their orientation, and the authorities kept a sharp eye on them.

The Lyceum, which at the moment of Polish occupation had reopened its doors, forgot the agreement it had signed during its founding a hundred years before and closed its doors to Jewish youth, except for a special few. Only a few were admitted. The agricultural school, a branch of the high school, which was in trouble with the city, regarded itself as the foundation of pure bigotry: “entry to Jews forbidden.” Jews had studied in the Polish state high school, which replaced the Russian High School of Commerce, and now studied in public schools. The Polish students who entered the Lyceum and the agricultural school had a large and direct influence on the city's youth. The majority of the students came to learn, as in a university city. Their sports activity, which was energetically supported by the state, also awakened interest on the part of the Jews. The Jewish sports club, Chashmoni, grew in size and number, and many members excelled in the sports arenas, in which they were to that point unknown in the city.

The revolutionary years and the winds of freedom blew in from neighboring Russia and forced themselves on the essence of the people. They would no longer bend to the Polish aristocracy's authority. Every attempt by the “dear children” of the out–of–state Polish apparatchiks who studied in Kremenets to insult or to defame the Jews was cut off at the root, and for this they paid a pretty price. After every attempt by these people, several of the hooligans wound up in the hospital.

In the 1930s, the Polish Senate brought its harsh methods of governing, which were based on oppression and terror, to Kremenets. The authorities began to involve themselves in the community's inner life; they began to support the power structure that went along with them, thereby dividing the community. They took sides in arguments among the rabbis and ritual slaughterers and turned the wheel back in time. Anyone who protested was subject to persecution and loss of livelihood. Even so, the Kremenets merchants and Zionists persevered and accepted this difficulty.

[Page 117]

Dr. B. Landsberg was a jurist, and the authorities were ready to relieve him of the right to plead before the court at any moment. However, he never stopped fighting against all sorts of chicanery; Goldring showed no pity in his struggle against the powerful people who were supported by the regime. And so did Zeyde[9] Perlmuter (so–called, although he was energetic) and many others. At this time, Kremenets already needed to have its own open forum. So they published a weekly Jewish periodical in which Zionist activists of every stripe, as well as the unaffiliated, took part. I have saved several copies of this paper, which shows black–and–white examples of this obstinate struggle. It bears witness to agile national Jewish activity, which the publishers regarded as in the category of a commandment, day or night. The newspaper was published for a few years and had a great influence on the people.

As a matter of course, along with political suppression came economic suppression. Jews bent under the heavy weight of taxation. The flow of business was obstructed, unemployment was rampant among the young people, and they became corrupted.

An atmosphere of uninterrupted pogroms made its way into our region. A Jew was no longer safe alone in the black of night on a deserted street. It became dangerous to go for a stroll in the mountains. This confusion lasted for years–long and bitter ones until that fearful catastrophe arrived.

With the outbreak of Hitler's war, may his name be eradicated forever, the Polish government and diplomatic corps arrived in Kremenets. The Lyceum's huge buildings housed all of them. The Germans soon learned of this, and the city was bombed. The Red Army abandoned the city for two years. Jewish youth, who remembered well the Polish rod of discipline and the shame of unemployment, greeted the newcomers with open arms. At last, the Jewish residents breathed freely, for a short time.

However, the Zionist movement was ordered to lower the flag and stop its activity. The Bolsheviks didn't treat the Zionists badly. It was known that Goldring moved to Lemberg; Dr. Landsberg remained in the city to the end.

And because the Russians left the city unaware, a new catastrophe began for the Jews. Only a few Jewish youths accompanied the Red Army. The remaining Jews were left in the Germans' viselike grip. A few streets were blocked off and designated a ghetto, which lasted a full year. Every morning, the Jews went out to work under a watchful eye, and in the evening they returned. Life in the ghetto was unbearable. Hunger and sickness cut into their lives. Torture and agony relieved the ghetto Jews of their humanity. In October 1942, when the population was led to their slaughter, they were no longer people; they were ghosts.

During the Nuremberg trials, a German transportation planner who witnessed this slaughter described the great tragedy of the Kremenets Jews in the ghetto. But their attitude during their last journey was truly heroic.

Fifteen thousand Jews from Kremenets and the surrounding towns were slaughtered in just two days. They were all buried in a mass grave near the train station. A few hundred Jews barricaded themselves in the ghetto, and with weapons in hand, they fought the Germans and Ukrainians. After a short battle, the ghetto was burned down along with the fighters. A small detachment of young people, under the command of the young man Yonye Bernshteyn, got lucky and fled into the forest, where they continued to fight as partisans.

[Page 118]

Other survivors joined them, and it wasn't for nothing that the Germans put a large sum of money on Yonye Bernshteyn's head.

Nothing was left of Jewish Kremenets. Where the houses stood, there is a void. Even the Great Synagogue, with its thick walls and pillars, was bulldozed and erased from the face of the earth. In its place stands a plowed field facing the heavens. Only a few Jews from the large community of Kremenets survived.

|

|

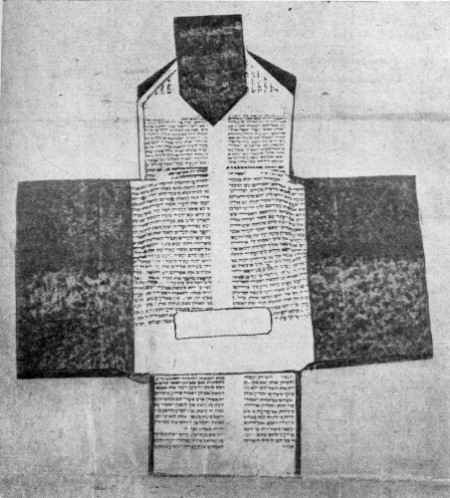

| A ladies' purse, made from Torah parchment, which a Gestapo agent sent to his wife as a gift from Kremenets during the Holocaust in World War II |

Translation Editor's Notes

- MHR”L is an abbreviation for “our teacher the rabbi, R' Loew”: Yehuda Loew of Prague, a 16th–century scholar. Return

- In Hebrew, Testimony in Israel is Teuda BeYisrael. The nickname “Teud'ke” is based on this title. Return

- Avraham Ber Gotlober was a writer, poet, playwright, historian, journalist, and educator, and a leader in the19th–century Jewish Enlightenment in Russia and Eastern Europe. Return

- “Justice shall go before him” is a quotation from Psalms 85:13. Return

- The text within the photo reads as follows. Top left: April 30, 1924; center: A Memorial for All Time; right: Nisan 26, 5684. Middle: To Dr. Litvak from Friends. Return

- Shkolim were tokens of membership in the Zionist Organization. Return

- The Cheka (the “political police”), which later became the NKVD, initially fought counter–Soviet activity. The acronym stands for Extraordinary Commission to Combat Counterrevolution, Sabotage, and Speculation. Return

- ORT stands for Obshestvo Remeslenofo Zemledelcheskofo Truda (Society for Trades and Agricultural Labor), which provided education and employable skills. TOZ stands for Towarzystwo Ochrony Zdrowia, Polish for Association for the Protection of Health. Return

- “Zeyde” (Perlumuter's nickname) means grandfather (and therefore supposedly old and lacking in energy. Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kremenets', Ukraine

Kremenets', Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 26 Dec 2018 by JH