|

|

|

[Page 320]

by L. Eler (Kremenitser Shtime)

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

The day when the first group of children became independent and left the building was a great holiday. They had finished their studies, and the trade they had learned helped them earn enough money to support themselves and not be dependent on outside help.

The faces of the self-supporting orphans were serious and thoughtful, because they were aware that the day represented an important step in their lives. From that day on, they knew, they must care for themselves, earn money to cover all their needs, and be responsible for whatever happened in their lives. For the educators, teachers, and organization members, this was a day of deep satisfaction and moral fulfillment. They remembered the children's condition on their arrival, how much effort and work they had invested in each child, how worried they were when a child was sick, or, on the other hand, how much joy they felt with every good grade the children brought back from school or evening courses. These were the thoughts that went through the heads of the teachers and “graduates” alike when they observed the younger children of the orphanage being happy, singing, and dancing at the celebration that evening.

The next day, they took their things and went out to begin their independent lives, each according to his or her means.

At first they stopped in often “to see how things were and what was new,” and later they would come every Sabbath “to visit.” In time, these visits naturally became rarer, since they were busy working and taking care of every little thing. However, spending so much time alone and being in the streets so much during their free time worried their former teachers, so they began to think of creating a place where the older children could gather and spend their free time.

Such a place was soon established-the Circle of Independent Orphans. Its aim was to hold literary evenings, establish a library, and so on.

Later, a drama group was also founded, which successfully performed The Treasure, a play by Shalom Aleichem-with the entire proceeds donated to the orphanage. The Circle members helped the Society with all its activities. Every evening, they would meet in the place rented for the “club,” so old friendships formed in the orphanage days were kept alive.

It is hoped that the Circle will help keep this “family of children” together and that at least some of them will become “doers” who are always concerned with the welfare and development of the orphanage, where their little sisters and brothers are still being educated.

May the first fruits of our labor be blessed!

Long live the Circle of Independent Children!

[Page 321]

by B. Barshap (New York)

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

Kremenets was, to a certain extent, a city of labor and crafts, a city of Jewish hard workers. Beside the scholars and liberal professions, the city was home to many different trades and occupations, which supplied industrial necessities to the many smaller towns and villages that surrounded it.

Let us list of the various occupations that existed and flourished in town, thanks only to the Jews.

There were tailors-of two kinds: fine, high-quality tailors and poor tailors. They made men's wear, women's wear, and military uniforms. Our Yankel Shmukler is worth mentioning here: he was highly valued by high-ranking military types. He received orders for the most important uniforms, especially those with rank emblems woven or embroidered in gold thread; he worked on them by hand, one by one.

There were carpenters who made fine furniture and construction joiners; roof constructors and tile layers; lathe workers, who worked on two products: fine furniture decorations and cigarette holders-the latter exported to Russia; blacksmiths and tinsmiths; wagon-wheel makers, tile makers, coppers (barrel makers), shoemakers, leather workers, tanners, potters, glaziers, cotton makers, purse makers, goldsmiths, watchmakers, road and bridge workers, grinders, brick makers, carriers, water carriers, butchers, barber-surgeons, cigarette makers, linen seamstresses, etc.

The transport business was in Jewish hands as well, whether it was delivery or hauling wares between the neighboring villages. Of the carriage drivers, Shimele Poyker, the lively, beloved wagon owner, is worth mentioning. Every Sabbath afternoon, young boys and girls would gather at his house, and he would read to them from books he obtained ahead of time from Moshe Pakentreger …

The Jewish people in Kremenets lived modestly, their livelihood based on their own toil. This was the way they managed their community activities as well. They didn't make much noise, as others did.

Even the first strike-over the demand to have the nights of Jewish holidays free-was decided on a Saturday morning after prayers, during the Kiddush they held at the home of Etel, Manus's wife …

… And my ears would absorb scores of folk wisdom on winter days, when we would seek a little warmth behind the stove in the Butchers' Synagogue.

This is what we were when we came over here, to the free land of America, armed not only with working hands but also with the heritage of the home where we were born. Here as well, we observed and cherished our fathers' simple, unsophisticated, and modest lifestyle.

[Page 322]

by S. Fingerut

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

| In the little town of K, in the middle of Green Street lived a tailor; his face is pale-it looks green as well. In a little room, always too dark, the tailor worked, deep in thought. His room is full of dust, never very clean, as was fitting for a beggar-it is easy to see … Children, little ones, half-naked and bare, roam around, each wanting to eat, to put something in their mouth. The poor, sickly father must work and toil, sew and produce clothes for the smallest of pay. His wife, she doesn't know what to do first: cook the “warm meal” or sit by the sewing machine. Poor thing, she wants to help and earn something, too, so she cannot think about warm meals now. The children cry: “Mommy, give us something to eat!” The tailor, as well, cannot forget this cry. His heart is weak, pulling him down to earth: “Woe to the fate bestowed on me, always toil, always hard labor, nothing of my own. Still, this is God's little world, and there's nothing to say, and whatever happens must be taken as good. One must have complete faith in His mercy, since He leads His world in splendor and beauty, which we, little men, can never understand… . Since He is the God, the only Creator, we believe in Him and learn His Torah.” So the poor tailor must follow his fate, and from his darkened nest strive and aspire- while thousands of others are happy and full, and never knew a bad day. … At the end of the Green Street, to the right, that is where the tailor lives. You know him very well … |

[Page 323]

by Hadasah Rubin

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

|

Who needs strength?-I sell strength- a back of iron, and hands, too.

One bag of coals, and ten bags of fire.

My eyes are fixed on the dusty sky.

We carry the rich and noble their mirrored wardrobes,

Hey, you, don't rush, watch the mirror, go slow!

Faster, go faster, the children are waiting.

I'm selling my days, my years and my strength

You who are full and tired from the abundance of food-give me the bundle,

“Father, for weeks we don't have any flour-

Children should have rosy cheeks-

Nobleman, take me, I'm the healthiest,

Over the years I have carried many pounds of wheat on my back,

Strength for sale! Who needs some strength?

Yes, I long for more heavy wardrobes and plush velvet sofas |

[Page 324]

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

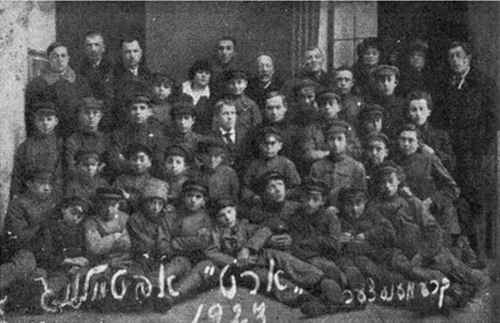

One of the most beautiful and important institutions owned by Kremenets was the ORT School, which during its existence educated Jewish young people and turned them into helpful and productive elements of society.

The ORT School was founded in 1922, thanks mainly to F. Perlmuter and Ovadies. At first, the school operated in a rented apartment and had two divisions: a locksmith workshop and a lathe workshop. The school's first director was Eng. Dekalboym.

The ORT Central Office in Warsaw provided the school with the necessary tools. The school's high educational standards were of great interest to Jewish youth in Kremenets and vicinity.

In time, the school grew and relocated to a building of its own, and two new divisions were opened. The new director was Eng. Raykh.

The school's graduates worked in various craftsmen's workshops, and some of them remained in the school workshops and continued working and teaching there.

Exhibitions of products created in ORT workshops gained recognition from the Jewish and non-Jewish population alike. The beautiful and trustworthy tailoring department, which always had orders for several months in advance, became especially famous.

The school's regular budget was covered mainly by the Central Office, but also by tuition, income from the sale of products created in the various workshops, etc. The financial situation was never very good, and the school had to overcome several crises.

|

|

[Page 325]

|

|

Thanks to the teachers-including non-Jews as well-who almost never received the full pay they deserved, and to the devotion of a group of people headed by Ovadis, the ORT School managed to stay alive. From time to time, fundraising meetings were organized, and the public would respond warmly and generously. The students would organize theater performances and donation days-with all earnings going to the school. An effort was always made to cooperate with the ORT Society members.

From time to time, a Central Office representative would come to Kremenets and help carry out various decisions for the school's benefit.

The city mayor assigned certain sums from the city budget to the school. The high school helped with building materials and wood for heating.

All this has helped expand craftsmanship and general education even to the poorest segments of the Jewish population.

In 1932, the school's principal and director was Eng. Avraham Rozin, and at that time the ORT School was recognized by the state as a State Craftsmanship School.

In 1936, ORT had 160 students. Seven classes had graduated by then, including 39 candidates for the tailor's assistant exam and 14 candidates for the locksmith's exam. There were also special seamstress courses for adult women, which have earned a very good reputation.

[Page 326]

Under Soviet rule, the ORT School was converted into a school for tractor drivers.

Many of the graduates now live in Israel and are practicing their professions.

For many years, the ORT School in Kremenets enjoyed the help and support of the Relief Society in America. A testament to the ORT School's popularity and the respect it commanded among the Jewish population is the fact that Yitschak Ber Levinzon's place was registered under the ORT name-the only state-authorized institution with a permit to buy real estate.

Active supporters of ORT last year included Goldring Meir, Vaynshtok, Trakhtenberg M., Margalit Yisrael, Ovadies Chayim, Kroyt, and Eng. Rovin.

[Page 326]

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

From time to time, a drama or theater group-Jewish, Polish, or Ukrainian-would come to Kremenets and give a performance. The performances were usually well received by the Jewish public, and attendance was very satisfactory.

However, Jewish young people weren't content with that alone, and various organizations created drama circles. These circles organized performances as well, sometimes very successfully. To their credit, it must be said that even a failure wouldn't discourage them, and the Jewish public would forgive them, because “they're our own people … who are ‘playing the theater,' and the artists are only amateurs.”

Performances included plays by Perets Hirshbeyn, performed by the Professional Organization's drama circle and directed by Bluvshteyn; “The Haunted Inn,” also by Hirshbeyn, performed by the Independent Orphans drama circle under the same direction; “The Vagabond,” performed by the Zionist Organization Amateur Group and directed by Pinchasovitsh; “Kol Nidrei” and “Bar Kochba” by the same group, and many others.

Musical-artistic evenings were sometimes held at the Tarbut and ORT schools. These evenings were usually very successful, the subjects being poetry reading and singing, as well as short plays in either Hebrew or Yiddish. The audience consisted mainly of the children's parents, who received these evenings with enthusiasm and supported them willingly.

Other organizations would arrange such evenings as well, and they offered very pleasant entertainment. Especially when a satiric-humorous evening was organized, and the “victims” were local active members and various organizations, the entire town was in an uproar.

[Page 327]

Kremenitser Shtime

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

One of the most popular institutions in town was the Charity Fund. It was established in 1927, and with the ruin of the community, this beautiful enterprise was destroyed as well.

The founders and managing members made every effort to increase the fund's income. They organized Support Circles and a Charity Fund Month, advertised in the local press, asked for pledges on Simchas Torah, etc.

On the fund's fifth anniversary, a special booklet was issued as part of the festivities. The City Council and the Jewish community both assigned sums of money for the Fund.

The Joint helped as well and supervised the fund's activities. While the fund's only income came from philanthropic sources after appeals to the people's goodwill, bookkeeping followed strict economic principles. The treasurer and accountants would see to it that loans were paid on time, no debts accumulated, and all past debts collected.

Before a holiday, when needs and, accordingly, loans increased, a good soul could always be found to donate several hundred zloty to the fund.

Loans were given to cart owners to buy a horse, to needy sick people to buy medicine, to poor families to help pay the rent, to small businessmen and craftsmen to help with yearly expenses, etc. The loans were always interest free and were paid back in weekly installments.

The Charity Fund has given a great deal of help to the Jewish masses. Thanks to the fund, many families were saved. The fund administrators were very careful not to lose one zloty. People who were too ashamed to ask openly for a loan would receive one secretly.

The local rabbi, Rabbi Mendiuk, would often mention the Charity Fund in his sermons; sometimes he devoted the entire sermon to the commandment to help the needy and the necessity of having a fund for this purpose. And the fund's main objective was, indeed, to make sure everyone who needed help would receive it.

The members of the fund's last administration were Moshe Gershteyn, Shlome Fingerut, Duvid Goldenberg, and Neta Shtern.

Our Charity Fund was a branch of the Charity Fund central offices in Poland, and its representatives participated in the funds' general conferences.

[Page 328]

One conference was held in Kremenets, with representatives from neighboring towns participating.

A special fund was organized in the Dubno district as well.

[Page 328]

by M. Gershteyn (Kremenitser Shtime, January 8, 1932)

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

According to the ledger that began in 5587 [1827], the oldest charity fund in Kremenets was the Free Loan Society, which lent money to the needy against a guarantee. The register shows that this society was a carryover from another of the same name that had ceased to exist.

“These are the activities of Free Loan, duly recorded in this LEDGER,” we read on the cover page of the 1827 ledger.

That year, several respected members of the community-educated people from Y. B. Levinson's time-got together with the aim of renewing the former Free Loan Society's activity. They compiled the following regulations:

[Page 329]

The above regulations have been compiled and approved by the general assembly and officers of the society. Signed:

The scribe Moshe Shlome, son of our master and teacher, R' Yakov of Ludmir

As we can see from the minutes of the meetings in the following years, the regulations changed over time. We find, for example, that the society's officers were elected by a majority of votes and not by drawing lots. The permitted loan amount increased to three rubles. The monthly membership fee was lowered, the loan repayment period was extended from three months to three years, the registration fee increased from three to six rubles, etc.

The number of borrowers can be assumed from the total amount of the loans issued. When the society was founded, the sum of the loans issued was 50 rubles, 52 years later it was 300 rubles, and in 1913 it reached 1,000 rubles.

Considering that the maximum amount loaned was 5 rubles in 1913, we can easily imagine the great number of borrowers and the fund's success in Kremenets Jewish population in.

According to the minutes registered in the books, elections took place every year, no later than the week of Mishpatim, in a festive atmosphere. In time, at the formal meals organized by the chief officer, 13 courses were served; however, brandy wasn't allowed, only beer, which guests had to pay for.

[Page 330]

The members covered the rest of the cost of the meal. The leftovers were used by former and newly elected officers. The Free Loan Society never knew any conflict or disagreement.

In the ledger containing members' names, we find some most distinguished individuals, including great scholars, such as Chayim Landsberg and Dr. Arye Landsberg, the descendants and followers of Avraham Ber Landsberg, of blessed memory. They were relatives and friends of Y. B. Levinson. R' Avraham Ber Landsberg died on the 33rd day of the counting of the omer [May 1], 1831, during an epidemic. He was the father of Arye Leyb Landsberg, the well-known scholar and bibliophile, and Shlome Yeshaya Landsberg, Hakarmel [2] contributor. The leaders also included Nachman Prilutski, father of Moment editor Tsvi Prilutski.

A former leader's son told me that 45 years ago, the well-known community activist Dr. Hindes's membership was terminated because he came from the craftsman's class. It was rumored that he and his friend Tsvi Prilutski went to the officer and demanded to be shown where in the ledger it was stated that Hasidim and craftsmen couldn't be accepted as members.

Naturally, there was no such statement in the ledger. The fact was, however, that Hasidim and craftsmen weren't accepted as society members.

At the outbreak of World War I, the fund's activity ceased, and it was only when the war ended that a general assembly was called and the members tried to renew the activity. Finally, however, after several meetings and investigations, the decision was made to liquidate the society. Guarantees were returned to borrowers, and loans were canceled; some of the silverware that had been deposited as guarantees was donated to the local Home for the Aged, and the rest of the valuable guarantees were sold. The money was used to help renovate the public bath, which had been built 41 years before by a Jewish tailor named Malakhov, who had built the big New Study Hall as well. The income from the bath was supposed to fund the maintenance of the study hall.

In consideration of the community's needs, the remaining Free Loan Society members decided to donate the rest of the society's capital to the maintenance and renewal of the hospital, orphanage, and Home for the Aged. The renovated bath was turned over to the management of a homeless Jew in return for payment of a certain amount of interest.

The society owned two stores and used to add the rent to its budget. Since societies like the Free Loan Society weren't registered during Russian rule, the stores were registered in the officer's name. In later years, the two stores were demolished, and an heir of the last officer sold the property to a Christian.

Thus ended the existence of this old Jewish charitable institution, and all that remained was its history, recorded in an old ledger…

[Page 331]

|

|

Translation Editor's Note

[Page 333]

Kremenitser Shtime

Translated by Yocheved Klausner

Kremenets has become famous for its institutions, devoted community workers, beautiful youth, and energetic civic life. However, the truth must be told: there were negative aspects as well-disputes, betrayals, and even fights. To be sure, Kremenets was no exception to this.

There were intrigues and conspiracies, different “camps” formed, and arguments became conflicts… Still, the sympathy of Jewish society in general was always with the honest people.

A dispute might occur anywhere, even in the synagogue during prayer. It would begin with a simple discussion but would soon develop into a fight-sometimes a real fistfight-and more than once the affair ended up in court.

The local press held these fights in check, somewhat: people were ashamed “to be mentioned in the newspaper.” On the other hand, some people found ways to overcome this problem: the paper was printed in Rovno, and an anonymous hand would mysteriously delay its arrival until after the Sabbath, when the news was already “old news” and readers had lost interest.

A burial society had existed for over 100 years, but another society, the Pallbearers, was created and soon received a license from the authorities. Fierce competition between the two caused the authorities to appoint a special “commissar” to investigate the matter, and some of the managers were arrested during the investigation.

Although the rabbi was usually elected by an enormous margin, there were some who tried to prevent him from taking the post by getting the authorities to intervene.

In the Hasidic Synagogue, a fierce argument broke out concerning the appointment of a cantor, and the same thing happened in the Magid's Synagogue.

One community leader didn't come to meetings for an entire year and conducted a campaign against the community.

The greatest aggravation, however, was caused by an open attack on the community in 1931. The butchers went on strike, asking for a reduction in the fees they had to pay for slaughtering. Since their demands weren't met, they took the animals to slaughterers in surrounding towns. This dispute grew into a huge, long fight: the butchers hired their own slaughterer from a neighboring town, the community confiscated the slaughtering knives, the butchers responded by snatching another slaughterer's knife, and so on.

[Page 333]

The community secretary was even beaten, and a meeting to try and resolve the dispute ended in nothing but some broken teeth and a demand from the head of the community that he resign. Instead, he called the police. The police began an investigation.

The Union of Rabbis then sent the “obedient crown rabbi” from Rovno to aid the investigation and end the dispute.

Then a special committee was appointed, and according to its decision, the rabbis and several community leaders “toured” the Jewish butcher shops and asked customers not to buy meat slaughtered outside the town. This infuriated the butchers even more, and they gave the rabbi and his friends a good beating. A protest meeting was called; over 1,000 people came to the meeting and condemned the butchers' behavior. Finally, the authorities intervened again, and at long last the bitter conflict was liquidated. The final stage of the affair was played out in the local court, which recognized the Kremenets Jewish community's full rights in the slaughtering dispute. Since the community won the trial, its authority was strengthened, and the Jewish public could finally relax.

|

|

[Page 334]

|

|

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kremenets, Ukraine

Kremenets, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 06 May 2012 by JH