|

|

|

[Pages 424-432 - Yiddish] [Page 168-174 - Hebrew]

by Shlomo Untzig, Tel-Aviv

Translated by Moses Milstein

In the little shtetl of Krasnobrod, the Untzigs, a broadly extended family, made up a good fifteen percent of the population.

Who did not know Shimon Untzig, the Gerer Chasid, who used to tell wonderful stories, Saturday evenings at the melave malkas, about the Bal Shem Tov, about the Barditsher R' Levi-Itzhak, and other rabbis. Everybody would come to hear his stories.

This large family lived quietly and happily. All the children, except for me, were married and lived in Krasnobrod. Come a Saturday or a holiday, the sons and daughters and their children would get together at father's house. We were happy in each other's company. Mother would pass out presents to her grandchildren…And in this way, we lived peacefully, until the year 1939 arrived, and World War II broke out.

With the arrival of the Germans, the population fled to the forests on Mt. St. Roch. My father and I, and a few other older Jews, locked ourselves in our house. We sat and recited psalms. We begged God for a quick end to the war. Then, we heard banging on the door. I opened it, and several Germans entered shouting, “Jude, get out fast, or you'll burn with your house.” We fled straight to the lonke, to Yankele Gareler. We threw ourselves down on the ground. It was night already, but bright as day. The city was on fire. I heard a shot, and Eli Liebel fell dead. We lay on the ground, we didn't dare to look up, our lives were in peril. I held my siddur and prayed to God, father pleaded with God, loudly, to have pity on His few Jews and put an end to their sorrows.

The fire grew, the shul burned down, and the fire moved on until a miracle occurred. The fire stopped at Natan Lipschitz's house and at ours. The houses remained intact. Father thanked God for His help. His house was not burned. He did not know that, because his house was spared, it would become the cause of the destruction of our entire family. Father said, “ I will take all the children in to live with me. Why should I run to Russia, when I don't know if I will ever come back?” …

Nevertheless, I went to Rawa-Ruska. After a few months there, I became homesick for my parents. I got ready to return home. It meant stealing over the border… I took with me Feige, Arele Untzig's daughter. We staggered through the forests in deep snow. Feige's feet froze. She couldn't walk. I practically had to carry her on my shoulders until we got over the border. (She later, unfortunately, was killed by the Germans).

I managed to get to Krasnobrod in peace. It is impossible to describe my parent's joy…

One day, I went out and saw a horrible scene. A German was driving Natan Lipschitz through the streets and beating him. Shkotsim followed them, the German shouting, “He deserves to be punished. He charged a Christian more than the goods are worth.” Natan lay in bed all Shabbos from the blows. On seeing this, I resolved to go back to Rawa-Ruska immediately. Early Sunday, Yekutiel Kupiec and I headed for the border. My dear mother accompanied me and cried bitterly on our parting. It did not occur to me then that I was leaving my parents and my sisters and brothers forever…

I stayed in Rawa-Ruska for a few weeks, and then I became the first sacrifice: I was arrested in the street, and sent to Siberia. I will not dwell on the years I spent in Russia. Whoever has been there, knows full well how life was…

As the end of the war approached, I wrote two letters to Krasnobrod. One to our neighbor, Pavlovsky, and the other to Shitkowisk with the question as to whether any of my family still lived. To my great sorrow, I received the news that my parents were dead. I cried long at these tragic tidings. Nevertheless, a spark glimmered in me. I hoped, that if I could leave Russia for Poland, I could get to Krasnobrod and see if anyone was still alive from the huge family that we had.

And I lived to see the day when I arrived in Szczecin, Poland. From there, I left for Lublin. And on that very night, traveling to Lublin, another disaster struck, the Kielce pogrom. The Poles were determined to finish what Hitler could not—the annihilation of the Jews. In Lublin I met Moshe-Eli Untzig and Moshe Fishl. They would not allow me to travel to Krasnobrod. Moshe Fishl told me all about the great tragedy that had happened there. I decided not to travel there for the time being.

|

It took a year, but Moshe-Eli Untzig and I got permission from the Zamosc authorities to exhume our relatives' bodies. We requested an escort from the Zamosc police. But they refused to send any of their men. It seems that, in broad daylight, the police in Krasnobrod had been taken out of their station and shot. This was done by the bandits of the A. K.[1] Nevertheless, we were determined to go there and carry out the exhumations. No one can feel or comprehend the great calamity of someone who has to go around looking for the bones of his parents, his sisters and brothers. No writer in the world could understand it adequately in order to describe what I went through. Once in Krasnobrod, Moshe-Eli and I went to the village Szur. Under a tree in Szur, Moshe-Eli's mother, Matl Untzig, lay buried. We were led there by a Christian who identified the grave by the name of the interred. We began to shovel and dig. We quickly uncovered some bones and a head. We gathered the bones and transported them to the cemetery and buried them there.

Now I turned to the hunt for the remains of my own family. I wanted to know how and in what circumstances the Nazi murderers killed my parents, sisters, brothers and their children.

My family had hidden themselves in an attic, concealed by planks. At night, one person would steal out to find food for everyone. A Christian lived in the house, but he did not know that there were Jews sheltering in the attic. The coming of winter brought cold and greater hunger. One day, a child was crying, and a passing sheygitz heard and quickly ran to bring the Germans. They were all brought down from the attic, taken to Sziskowski's wall, that was Shmuel Ozer's place, and shot. Many Christians stood around and calmly looked on as the last Jews of Krasnobrod were eliminated…Who did not know Janek Zomb? He went around removing the boots and shoes from everyone. He dug out a large grave and buried everyone in it. I was told that my dear brother, Henoch Untzig, refused to turn his head to the wall, so they shot him first…

It was not easy to find a goy who would help me dig up the bones. I had to resort to the same Janek Zomb (Jaszek Kaszkales). With great enthusiasm, and for a good fee, he agreed to help me with the work of disinterring the same people he had buried there with his own hands. I went with him to Milniczik at the sawmill, bought some boards and built two coffins. I then went to work opening the grave. Rivers of tears fell from my eyes. From a whole city if Jews only I am left to do this holy duty. I had just begun to dig the earth when in only a couple of shovelfuls, I came on bones with children's heads… --Dear, innocent children, why did you have to be taken from the world! I placed the remains in a coffin and continued to dig. I began to find larger skulls. I couldn't tell if it was mother or a sister or brother. I placed these in the second coffin. And then I unearthed a head which was so dear and familiar, as if alive. It was my father's head with the blond hair in his beard. And Zomb, my assistant adds: “This is your father, who I hid here four years ago.” My wails reached the sky. It was indeed my father's beard… there was a curious group of goyim standing around and they added their agreement, “This is your father, Shimon.”

I had to steel myself and stop crying so that I could keep removing the bones, and put them in the coffins with a little earth. I accompanied my holy family to the cemetery. I met many Christians along the way. I could see that they were laughing at me. With lowered head and constricted heart, I brought the martyrs to a Jewish burial ground.

The cemetery was also destroyed and in ruins. The tombstones had been torn out. At the very entrance, at the end, the ground was sown with wheat. The tombstones had been removed by the Germans to pave the roads. I looked for a spot deep in the cemetery. There was a large rock near a tree. Here I ordered a grave be dug. I lowered the two coffins, filled in the graves, and left a mound of earth on top. For a tombstone I placed a large board between stones and inscribed the names. I quietly recited Kaddish, and said good-bye to them forever.

It is hard to imagine how strong a person can be, how hardened he can become in times like this…There was one small consolation; I was able to do one last deed for them after their death…

On the way back to the shtetl, I passed the new bakery in the building that Itche Mendele's had begun. And, in this very place, I was told, lay the buried bodies of the children. One hundred and twenty seven perished here. Here too lies my brother Itzhak-Moshe. They were taking his children away and he went with them to their death. The Germans used grenades to kill them. The blood of the children flowed through the streets.

I came to my house and found the Christian, Zob, living there. Jusef Kazenowski lived in my brother's house. Everything was familiar to me. The same shutters hung that I used to close every evening. I saw my name written on the wall and various invoices my father had written for shingles for the goyim. I crawled up to the attic. Tattered siddurs and chumashes lay around. I picked everything up. It was all infinitely dear to me, because mother and father had held them and prayed to God…

Back down again I looked around. In this room my quiet uncle, Israel-Leib Untzig, had lived. He perished in Belzec. And here is the house where my uncle Henoch and aunt Sarah Untzig, Aharon Gershon Kleiner, and Chaim Untzig had lived. He was shot in the middle of the day on Shavuot. The house of Hershele Untzig remained. I found out that my aunt Malkah Gross and her children perished. They had come here from Siedlce. The entire family of Hersh Untzig perished, his children Itche Untzig, and his family. Shia Untzig, and his family, Yechazkiel Untzig, and his family. My uncle, Aharon Shmuel Mintz, and his children. No one was left from Chaim Bronstein, and Yankele Gortler's families. Only the empty place where their houses once stood. Now the town hall stood here. On Shmuel Levenfuss's place a wooden house now stood, a gentile one…

I went further and saw the place where my brother, Henoch Untzig, had lived. A little further on—Shlomo Glomb. Every day, I used to get the paper at Yonah Glomb's. All these places have been built up with small wooden farm style houses. The lots of Pesach Helfman and Itzhak Untzig held houses now. Farther toward the bridge, there had lived Baruch Eli Broder. We used to daven together at the Gerer shtiebl. A little further on, Shmuel Gortler's place has houses on it…Jewish life was torn out by its roots and extinguished by the Germans with the help of the Krasnobrod Polish population. Every foot of earth is saturated with Jewish blood. My sister-in-law, Surele Zimmerman lies in the Zielone forests. A shaygets killed her with a club.

Shlomo Zeltzer and I unburied the remains of his sister, Kaile Soshtchak, and buried them in a Jewish cemetery. Jews, in the hundreds, lie buried along the roads, in yards. Cattle and horses tread over their graves.

There is one Christian I stayed with whose memory I must laud. That is Felek Kozenowski. He kept with him in his house for a long time Yankele Laizer's grandson. Later, afraid of the neighbors, he sent him to his sister. But death was not eluded; he was killed with her on the way.

It is impossible for me to describe everything I heard while in Krasnobrod. Day and night I asked everyone about how and where people had died. They told me about how they dragged Hersh Leibl Briks and his wife from the sanatorium and shot them. I could not tear myself away from Krasnobrod. Time after time I went to the cemetery to say farewell to my nearest and dearest, and to all the martyrs of Krasnobrod. When I came to Israel and met my brother, Shmuel, my burdened lessened somewhat. I could at least tell it all to him.

Translator's note:

[Page 433 - Yiddish] [Page 162 - Hebrew]

by Moshe Eliyahu Untzig (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Moses Milstein

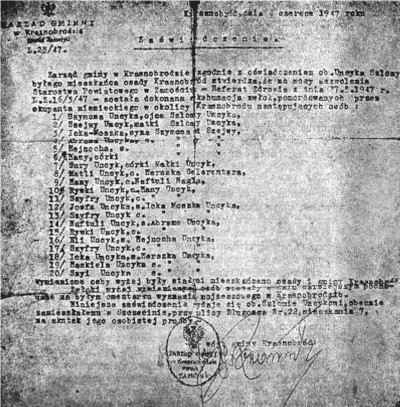

I inscribe here the names of the martyrs of the Untzig family who perished in Krasnobrod. May their names be memorialized in this book.

The dead are:

Itzhak Untzig, and my mother, Matel Untzig. The oldest sister, Tsirl, and her husband Itzhak Zilberstein, and their two children. The next oldest sister, Roize, and her husband, Yosef Lam, and one child. The third sister, Aidel Kimmer, and her child. The fourth sister, Sarah Untzig, 16 years of age. The fifth child, Meir Untzig, 14 years old. The sixth child, Etl Untzig, 11 years old. And the seventh child, Sheindl Untzig, was 10 years old.

Those are the ones who died in my family!

Now I will list the family of Yehoshua Untzig and his wife, Elke, and their three children, two girls, Etl and Shaindl, and a son, Chaim Untzig.

The family of Yechezkel Untzig, his wife, Baile, and their five children: Chanaleh, Shlomo, Chaim, Leah, and Perl. All killed!

I was repatriated to Poland from Russia in 1946, and I went to Lublin. From there, I wrote to Krasnobrod inquiring as to the fate of my family. I received an answer that 20 members of my family were taken from Shimon Untzig's attic and shot. They had had to first dig a mass grave on Shmuel–Ozer Kupic's land.

That was the atonement.

Soon after that, I travelled to Zamosc, with Shlomo Untzig who had also arrived from Russia, to acquire permission to perform an exhumation in Krasnobrod. When we got there, in the course of about 8 days, we dug up the remains in the mass grave, and buried them in the Jewish cemetery in Krasnobrod. It consists of one family grave near the rebbe's tombstone which has remained intact to this day.

In that grave lie Shimon Untzig and his wife, Sheva, and their children: Henoch, Avramke, with his wife and their children, and Itche Moshe Untzig and his family.

While in Krasnobrod, I learned that my mother, Matl had been killed in the village of Szur, and she was buried on the village magistrate's property. So Shlomo and I travelled to the magistrate in Szur. We made a coffin, opened the grave and transferred the remains of my holy mother. Her clothes were still intact…We put everything into the coffin and buried her according to Jewish law. This was on May 29, 1947.

For the few days we spent in Krasnobrod, we stayed with Michal Macikewicz. He told us that during the last liquidation in Krasnobrod, the old people and children were assembled in the unfinished bakery, shot and buried there. The soltis from near the church, Klisz, told us that Fishl Shlegel was called to the gemina and shot there.

[Page 435 - Yiddish] [Page 177 - Hebrew]

By Shabtai Barg

Translated by Moses Milstein

|

|

| Yakov Lederman |

The trials and survival of Yakov Lederman, a son of Yosl and Hindeh Lederman, who finds himself in Poland today, are here described by his friend, Shabtai Barg. While he was in Poland, Shabtai Barg discovered that Yakov was alive. He tracked him down and met him in 1946. Here he passes on what he was told by Yakov.

In 1946, I found myself in Szczecin, Poland. By chance, I met Shlomo Untzig. He told me that my cousin, Yankel Lederman, had managed to save himself from the Nazi murderers. He was now living in a village among goyim. He gave me an address with a Christian name, Jan Malinowski. He got the address during his last visit to Krasnobrod.

I was strongly moved by the news that my cousin, the always happy and cheerful, Yankel Lederman, was still alive, and I quickly sent off a postcard. I waited impatiently for a reply. After several days of anxious waiting, he arrived. But I was stunned and shocked by his appearance! His clothes – tattered; his feet wrapped in rags. Truly naked and barefoot. He looked greatly aged and worn out. I found it hard to believe that this was the same Yankel. I could not take in the idea that a man in the bloom of his youth, who had always been so happy and full of life, could become like this at the age of 32.

After we had well and truly cried, and talked about what had happened to our families – relatives, brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, who had been martyred by the murderous Nazis – I wanted to know how he had survived and why he was in such a deplorable state. I tried to hearten him and encouraged him to talk as much as I could. I must add that the city also had made a strong impression on him, seeing how life there was more or less normal, and that it was possible for Jews to meet. He was certain that there were no Jews left in Poland.

– What should I tell you, Shefsel, he began, and where should I begin, since each day was its own separate tragedy…You never knew what the day, or the night would bring. No one had an inkling of when his fate would be sealed: today or tomorrow. There was no food. We were swollen from starvation. Death was always staring us in the face.

– Tell me, Yankel, I urged him – How did you save yourself and where did you last see your mother and your sisters, your uncle, Melech, and his family, and your aunt, Blumeh, and her family?

– When Krasnobrod was burned down at the outbreak of the war – he went on – all of us, meaning our family, uncle Abraham Itche and his family, and later also uncle Melech and his family, we all went to Shumsk, to aunt Blumeh. She had lived there before. Shumsk was under Russian occupation. Grandmother, Baile, mother, Etl, and her two little children, aunt Tsetl and her family, uncle Volvish, and his family, and my brother, Nachum, and his family, all remained behind in Krasnobrod. Uncle Shmuel, and aunt Sarah Riva and their two little children stayed in Shebreshin.[1] In Shumsk, we soon found work. I got work in a Christian bakery. My sister, Gitl, worked in a pharmacy. We planned on sitting out the war here, and then returning to Krasnobrod.

Uncle Abraham Itche, and all of his children, could not wait, and they registered to return to Krasnobrod…But instead of Krasnobrod, they, along with many others, were sent deep into Russia. They envied us our staying behind and not having to wander who knows where…We did not want to register ourselves, and were preoccupied with figuring out how to return to the burnt – out houses we had left. So we kept on waiting…until the fire came to us.

As soon as the Germans, may their names be cursed, took the shtetl of Shumsk, they set up a ghetto, and packed all the Jews in there. All our families and myself were in the ghetto. The younger people were led out every day, under heavily armed guard, to various kinds of labor. They were brought back at night. I was also among them.

I worked in the same bakery where they baked bread for the Christian population. I got along well with the Christian workers. Among them, there was also a Christian girl, Stefa, who had a special affection for me. She tried to cheer me up in any way she could. She knew that I had a mother and sister in the ghetto. She would bring me all kinds of news, what was going on in the shtetl, what the word was about the war. One day, she told me that they were going to liquidate the ghetto. – “What do you mean, liquidate the ghetto?” I asked her. “Maybe they are going to set us free?” She was silent for a moment and then said quite clearly, “It means, liquidating the Jews.” I wanted to know how she knew such things, and where she had heard this. “It was heard,” she said, ”from drunken Gestapo mouths. If you want you and your family to be saved,” she advised me, “you have to escape from the ghetto before it's too late. I will show you a place you can hide.”

When I returned to the ghetto and told my mother and uncle, Melech, they refused to believe it. “It's not possible,” they said, “that they would kill all the Jews, and we mustn't risk it by running.” It wasn't long before, on a certain morning, they shut up the ghetto and surrounded it with soldiers. No one was let out of the ghetto, not even those who had been taken out to work before. We saw that we were lost. Stefa had been right. She wanted to save us and we had not believed her. Now it was too late. What to do? We were hopeless and in shock. Our blood congealed in our veins. We looked at each other with deathly fear. We saw each other as dead already. There was no hope or salvation. Some tried to console themselves, “Is it really possible that they would simply just kill us, slaughter us like sheep?”… People hid, crammed themselves into any hole, in order not to see the face of the murderers.

Outside it was pouring rain, as if God were weeping at our fate. Night fell, and the killers did not enter the ghetto. Perhaps the rain hindered them.

|

|

|

Hinde Lederman with her children On the right, Yakov Lederman |

We sat pressed together, in despair and trembling, our hearts pounding. At such a tragic moment, when we were facing death, my dear mother found some courage and said, “If we were all too late to escape, maybe, my son, it is not too late for you. The darkness of the night and the rain will help you. Jump over the fence.” I will never forget the deep sorrow I saw in my mother's eyes. That look still accompanies me wherever I go. I will never forget how she pressed me to her heart,

[Page 436]

“Go, my son, save yourself. Maybe we will see each other again.” I could not oppose my mother's will. We quietly said our goodbyes. We had to restrain our feelings in order not to attract attention. With a prayer on my lips that we should someday be reunited, I left the house, and all those dear to me.

When the rain got stronger, I jumped over the fence and took off running. But after running only a few tens of steps, a hail of bullets suddenly fell on me. I thought it would never end. I didn't know if they were shooting at me or at the ghetto. I quickly dropped to the ground. The swamp covered me almost completely. Each time the shooting increased, I dug my face deeper into the mud to shield myself from the bullets. I lay there like that for hours on end. My face was covered in cold sweat, and my life shimmered before my eyes. The shooting finally stopped. I started crawling on my belly, on all fours. When I passed my hands over my face and my head, my hair came off in my hands… I was struck with fear. I didn't understand what had just happened to me. I began to feel my head: Maybe I was wounded and was too full of fear to know it? No, I was not wounded. My hair fell out by the roots from pure fear – Is it a surprise for you to see me as I am? – Slowly I made my way back to Stefa before daylight.

Here, a new chapter of my sad story, with new sorrows, of a life lived in a dark cellar, begins.

No one could know about me in Stefa's house, not her brothers or sisters; it had to be kept a secret from them. Hiding a Jew was punishable by death. But Stefa, with her devotion, kept me from strangers' eyes. She hid me, as I said, in the cellar of their home. I sat in a large sauerkraut vat beneath another vat. Stefa cared for me like for a small child. She brought me food that she stole from the house, and carried away my things. She told me about the terrible disaster in the ghetto. About my dear mother and my young sweet, sisters. They sent me away to save myself, and they are here no more. The vat was wet with my tears. – What is the point of living? Stefa told me how heroically my uncle, Melech Tentser, defended Jewish honor. When he and his household, and other Jews were being led from the ghetto to be shot, he threw himself on a German murderer, tore the rifle from him, and shot him, calling out, “Jews, save yourselves!” But no one came to his aid, and he was shot there with his two little children. And that's how the murderers finished with the Jews of the shtetl.

|

|

| Melach Tentser and his wife and child. Hy”d. |

Stefa's parents noticed that bread was missing in the house. Bread was treasure in those days. Her father snooped around so long – until he found me sitting in the cellar…

[Page 437]

This created a terrible situation. He did not want me to be there any longer. Stefa defended me, and first of all, begged him not to betray me to anyone. He agreed, but on the condition that I leave his house. Stefa promised him, and took to finding me a new hiding place. After much running around, she managed to find a place at a friend's house, but only for a short time, until she was could find another place. She went off to a village to look for a hiding place. In the meantime, she heard that the Germans were registering farmers for work in Germany. She reasoned that the two of us should register so that we could get away from here. She doubted she could keep me here safely much longer. The plan appealed to me. That way, I could have a chance to breathe fresh air, and see the sun again, and not have to creep around in darkness afraid of the slightest sound.

But for me, it wouldn't be so easy. All those who were registered for work had to be examined by a medical committee, naked, to see if they were healthy. How could I do this? They would immediately know that I was a Jew. But clever Stefa had an idea. She found someone who, for a certain amount of money, presented himself to the medial committee and went through all the formalities. With these documents, I applied for transport. My name was Jan Malinowski.

Stefa was very happy that I was able to walk about in the free air. But I – how could I be happy when everyone was so cruelly murdered. How could one forget what the murdering bands did to our sisters and brothers, and I, a lone Jew, left to wander on the earth? Oh, how horrible this is. But I owe Stefa a lot. She is my guardian angel; she placed her life in danger for me. She left her home, her parents, her whole family, in order to save me.

Our transport carried us to Germany like cattle. They drove us to some small town, to the marketplace. Surrounded by villagers, we waited wondering what the bandits were going to do with us, where they were going to send us. They made us assemble in rows, and gave everyone a number, pinned to our lapels. My number was F854. Then, the Gestapo announced that they had brought “slaves for sale.” They allocated a price for each number according to age and physical strength.

The “buyers” were already waiting for the “merchandise.” First, they busied themselves examining us, feeling our muscles, pushing us to see if we would stagger, and then, they began to haggle over the prices. And that was the meaning of “they're taking us to Germany for work…” And that was how, exactly like the army, or maybe even much worse and brutal, in the year 1943, they sold us for slaves.

Stefa and I were bought by a farmer, a brutal person, to work his land. They treated us exactly like cattle, harrying us, cursing us “Faster, faster…,verfluchte untertanen!” Food was never enough. We worked and we starved, always living in fear, sundered from the world, with the horrible knowledge that all my near ones are long gone. And us – how long will we endure? Will it ever end?

Remark: Here I temporarily ended my talk with Yankel. I saw that he was too exhausted to continue telling me about his terrible experiences. We postponed it for another time. Regrettably, we did not meet again, because I left Poland shortly thereafter.

I only know that when the war ended, he travelled back to Poland with Stefa, settled in a village and lived there. He was certain that there were no more Jews left in Poland.

He did go to Krasnobrod to see if maybe, someone was still alive. But he could not even find any graves. He left his address with a goy who was once his neighbor in case some survivor would inquire about him and want to look him up. That was how I got his address.

Today, Yankel is in Sczczecin, Poland.

Dear aunt Gitl!

I have been saved from the claws of a monster, the likes of which the world has never seen – from Hitler.

…The battle for my poor life was very, very difficult. My bitter lot, my constant anxieties, and what I had lived through in the war, and what I had afterward seen in Krasnobrod, saw and heard – I say to you, that for me, it was not worth the struggle. It would have been better if I had perished along with my sisters and my mother.

…The Hitler sadists, along with the Polish people, destroyed, in the cruelest way, all the best and dearest that we possessed. We have no one left. Our shtetl Krasnobrod has been erased. Even the cemetery was not spared, the tombstones broken. The earth – plowed…

Your nephew, Yakov Lederman.

Translator's note:

By Shlomo Sonnstein (New York)

Translated by Moses Milstein

For the exaltation of the holy souls of the Krasnobrod martyrs; all those who fell and perished for the honor of the Jewish people, for the exaltation of the Jewish faith, Yizkor!

May these lines that I write be a ray of light in the ner – tamid that burns in our hearts. May it light the mass grave of the holy congregation, a congregation that was exterminated by a cursed, stupid, murderous, beastly people.

May the holy Jewish letters in this book shine clearly and by their light reveal the greatness of Jewish life, and the mighty courage of the Jewish Kiddush Hashem.

May our children and grandchildren read these words written in blood about our diaspora life; may they know what a bloody price we paid. May they understand how to cherish freedom and independence of Jewish life in our dear, free Jewish state. May they gain strength and courage from Jewish martyrology to fight for our freedom. May it be the consolation for our sorrow at the lives that were cut off before their time, for the community that was mercilessly annihilated before the eyes of the non – Jewish world.

Fate decreed that I, an unburned remnant of the holy Krasnobrod community, should be a living eyewitness to the fire that consumed the Jewish community. Thus fate punished me so that I would see with my own eyes, the first burnt sacrifices under the ruins of Jewish homes.

Krasnobrod was the first of the burned – out Jewish communities in Poland. It was the first of the sacrifices to be consumed by the flames of the worldwide fire. We were the first to be crushed by Nazi boots in their bloody march over the soil of Poland.

[Page 446]

Among the first victims were Shmuel – Ozer Kupiec and his son Mechl. Their faces were burned beyond recognition. We recognized the father by his tallit katan, which miraculously survived the flames. It was like a holy sign, and a symbol that the Jewish body can burn, but the spirit will survive any fire.

We found other burned bodies in the ruins. Unfortunately, we could not identify them, most were refugees from other Jewish communities.

On the same day, the Nazis shot: Leibish Kramer, Shmuel (Shmelke) Shtemer, and the mentally ill, Reuven.

That was only the beginning, the beginning of the end. The fire that consumed our shtetl, took a third of our people. It dried up the spiritual wells of Jewish life, and destroyed the generations – long, settled and deeply rooted, Jewish communities in Europe.

The murderous hands of the oppressors also did not spare the Krasnobroders who fled to the cursed soil of the Ukraine. There they shared the tragic fate of the Jews from Breilov.

The Germans carried out their murderous actions with meticulousness and precision. First, they murdered those who either had no trade, or had a trade that was not needed by the murderers. The tradesmen were then murdered after they were of no use anymore for slave labor.

Between one action and the next, people tried to find a way to escape the ghetto. In particular, they wanted to get to the areas under Romanian occupation…, in the so – called Transdniester. Although Jews there also lived in ghettos and in prison camps, the mass slaughters that were occurring with the Germans had not yet happened. They risked their lives and reached Zhmerinka and Breilov.

On a clear day at dawn, Romanian soldiers surrounded the ghetto, and drove all the refugees, 300 in number, to the slaughter, halfway between Zhmerinka and Breilov.

Among those driven to death were a Krasnobrod mother with her son and two daughters. They were Mirl Kupiec and her children, Chana, Bina, and Abraham. Chana refused to obey the murderers' order to strip naked; she was tortured to death. But morally she triumphed. She perished in her clothes.

May eternal shame accompany the murderers who wanted to disgrace the honor of this virtuous Jewish daughter, Chana. May the blood she shed be a holy gift for that which decides Jewish fate, and weaves it into the web of history, and soaks foreign soil with Jewish blood.

Yizkor! May the names of the holy martyrs of Krasnobrod be sanctified, may their memories remain forever in our minds, as the sorrow lives in our hearts.

Translated by Moses Milstein

Yonah Berland, Leibche's son, a lad of 20, while serving in the Polish army at the end of the war traveled to Krasnbrod with the hope of finding someone from his family still alive. The goyim caught him in the shtetl, and murdered him.

Feigele Fuchs, Itche Mendeleh's daughter, 18 years old. She survived in the forests until the end of the war. She went to Turzyniec. At the place where her parents had a mill, where she went to beg for some food from some goyim she knew, she was thrown into the water by shkotzim and drowned.

Tzipe Krelman, Moshe Krelman's wife and a 16 year old daughter had hidden in the forests near Botshiv. Soon after the war, when the Russians had taken the surrounding cities, they were told by the local farmers that they could return to their home in the town. On the way home, 2 km from the shtetl, at the village of Hutkow, she was seen through the window of the house of a goy who had been learning the shoemaking trade from her husband. He chased them both into the forest and murdered them.

Yosef Rind, Shmuel Rind's son. When the Zhmerinker ghetto was created, he gave all that he possessed to a farmer acquaintance. From time to time, he stole out to the farmer to sell something in order to provide for him and his family. At one such visit, the farmer, “his protector,” murdered him.

by Abraham Barg (Tel Aviv)

Translated by Moses Milstein

There was once a town here not long ago. It seems only yesterday that I was there, spoke with everyone, saw everyone–and suddenly, all of this is gone.

A shtetl, like many other shtetls in Poland, settled by peaceful, quiet Jews, citizens for generations–and suddenly, they are all gone.

A shtetl with all kinds of chassidim: Belzer, Radziner, Gerer, and Trisker…They travelled to visit their rebbes, good Jews, bringing petitions, and pleas for prosperity, doing business, wandering around, modest achievements–and suddenly all this is wiped out and gone.

There were scholars, proud of their Yiddishkeit, studying Torah day and night, surviving often on only a heel of bread and water, all undertaken for the love of His name–and now they are all gone.

There were businessmen, honest, hard–working people, preoccupied with the burden of making a living, but never forgetting to financially help out a brother, a friend, or the community fund to lend money to a near one, to help a neighbor in need, to visit the sick, and not only grant the mitzvah of bikur cholim, but also thereby, leave some money under the pillow in secret–and suddenly, all these dear people are no more.

There were the dear blooming youngsters, full of ideals, goals, politically engaged, debating issues, fighting among themselves for a better tomorrow, who thought they would bring salvation to the world, and to the Jews–and now they are all gone.

There once were children, bright, sweet, “yedder kind mit zein mazel,” as the Yiddish expression goes. There were mothers and fathers with their joys and sorrows, with their hopes. They hoped and strived to live to see a little naches from their children, and it is all obliterated and gone.

There are no more little children. There are no more mothers and fathers. There are no longer any hopes or dreams…There are no more sisters or brothers! Oh, dear, goodhearted Jews, I see you all, you are all around me. Here I see you in the days before Passover as you go from house to house collecting maos chitin[1], providing wine and matzos for the poor. Now I see you at dawn, still dark out, walking sleepily to slichot, carrying big lanterns, woken up by Zalman Ber, the shammos, who went from house to house, and with his big wooden hammer banged on the doors and shouted: “Wake up, wake up, holy Jews! Get up for avodat habora[2]!”

And now I see you, little children, Lag B'omer, dancing happily on the way to the tall “Mt. Sinai,”[a] carrying bows and little rifles, the mothers at the doors of their houses looking proudly on at their children who will grow up and study Torah, and forge the chain of the Jewish people.

Holy Krasnobroder Yiddelach, joyful children, future generations! Where are you now? Where have you gone? Where did the whole shtetl full of Jews go? None of you are left! Everyone killed, murdered; houses and their inhabitants incinerated, young and old dying together! hunted in every little corner, dragged out from all the dark hiding places, accompanied by taunts to the graves where the wild beasts were lurking, and who fell on your exhausted bodies like blood–thirsty animals, tore living pieces from you, threw you alive into your graves, one on top of the other, people covering people. Machine guns and rifles muted your death cries, suffocated your last breaths; your lives were wasted for the smallest things, by any vile creature. Nobody interfered with the murderers. No one asked, “Why?” Everyone was happy that your blood ran like water, the blood of children mixing with their mothers'.

Fathers, mothers, sisters, brothers of Krasnobrod. Who tore you away from us, tortured you to death, starved you, murdered you! Who stole from us our treasure, the youth of Krasnobrod! Daughters of Krasnobrod, gentle, tender, you were dragged by the two–legged beasts to the forests, raped, dishonored, and murdered. Mothers who shielded their children with their own bodies were shot with the same bullet.

Little children of Krasnobrod, little babes torn from their mothers' arms, thrown into the air like toys. Their screams, their sobs, concerned no one. The cries of children were not heard by heaven. Innocent children. Little souls! Why did you merit such a punishment? Who can comprehend it, who can endure such grief, such pain?

Woe to us that we lived to see with our own eyes the great sorrow, the terrible rage that God poured over His people Israel. Is there such a fire in hell? Does the tochecha contain such curses, that mothers and children should die such deaths!

Krasnobroder grandfathers, grandmothers, where shall we look for you? Where are your graves, where do your persecuted bones lie, your hands and feet that were tied to wagons and dragged through the streets. Where should we look for you–in the fields, the forests, in the gutters, or in Majdanek, Belzec, Auschwitz, where the German beasts, in the shape of humans, had built modern gas ovens for you? And what were you guilty of?–just being Jewish. And for that reason no one saw or heard the great tragedy. No one felt this great pain. No one wanted to help you. No one heard your cries for help, not in the east, not in the west…Enemies laughed. “Friends” were silent. Perhaps, they thought, we will be rid of the Jews forever.

The call to avenge the six million hangs forever in the air, and warns and demands that we not forget the blood that was spilled. Punish them God, the wicked, the murderers, for our innocent blood. Punish them for making soap of our flesh. Make them pay dearly for the ones they starved to death. May the murderers consume themselves, and tear their children asunder. The Aryan devils wanted to exterminate and obliterate every trace of the ancient line of Israel. May they disappear themselves.

We are left orphaned, perpetual mourners. Who can console us, understand our grief?

|

|

|

First row from the right, standing: Sh. Babad, F. Dimond, A. Giter Second row seated: A. Rind, A. Borg, G. Borg, A. Lochfeld First row from left, standing: Sh. Gurtler, M. Fishl, Sh. Levenfus Second row, seated: Y. Shlegel, A. Gurtler, A. Untzig, M. Rapoport |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photographed by Hersh Ben Moishe Gurtler |

|

|

|

|

Translator's notes:

Original footnote:

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Krasnobród, Poland

Krasnobród, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 7 Jul 2022 by LA