|

|

|

[Page 442]

by Dora Rophe-Goodis

Translated by Ala Gamulka

The Germans entered town on Friday, 27.6.41. Prior to their entrance there was heavy bombing on three sides: Matseyev Street, Brisk Street and Trisk Street.

The city was on fire. It began in the flour mill belonging to Armernik and spread from there over the entire area.

People searched for refuge and many of them found it in the Big Catholic Church.

The bombing continued all day. By Saturday morning the entire town had been conquered by the Germans. Two German officers entered the church and announced that the town is in their hands. They demanded from those gathered there to go back to their homes. Life will return to normal and no one will be hurt.

I went outside and I saw a frightening sight: the entire area, from Fabritchna Street to the Christian cemetery, burning intensely.

[Page 443]

The streets were filled with the German army. We saw the Germans catching Jews- supposedly for work. It was an omen for things to come.

I went with my late father to our laundry on Warshavska Street. When we arrived, we saw Germans taking Jews for labor. We slipped away from there and we hid in our store. There was a Christian neighbor in the courtyard and she denounced us. We heard loud banging on the door.

The Germans ordered me to work in the tobacco factory on Lutske Street. I was told to take a pail and a rag. In the factory I found many young Jewish girls who were also forced to work. I began to wash the floor and the windows. I was freed a few hours later and I returned home.

A few days later the Germans hung large posters on the streets. They announced that the Jews were to bring to the Command office radios, jewellery and other valuables. In addition, every Jew was to wear a white ribbon with a large blue star of David in it.

During the first weeks of the German conquest, life was, more or less, normal. Here and there, there were some frightening incidents. However, we did not see them as symptoms of the coming Holocaust. We believed we would be spared.

Our belief was strengthened when the Germans announced, innocently, that they would not interfere in our daily lives. The Jews were to elect a Judenrat — an Executive Committee- to organize our existence.

The following were elected to this committee: Vilik Pomerantz, chair, Shlomo Mandel, Itzel Bokser, Moshe Perl, Boris Levin and Yehuda Fried. Anna Lerner served as secretary.

Our serenity did not last. Our skies were darkened with heavy clouds. There were no pleasant rains, but instead there were bloody and tearful floods that were meant to exterminate us from this world.

Soon SS units arrived in town and the brutality began. Any Jew found on the street was whipped and his beard was torn off.

The SS units used to announce a curfew on a specific area and then they burst into the homes. They pretended to take the men for work, but none returned. Our non-Jewish neighbors told us that they saw many Jewish bodies lying on the streets, but, at first, we did not believe them. After several weeks, when our Jews did not return, we began to understand that these terrible stories were true, unfortunately.

This is how life continued from July 1941 to May 1942. During Passover 1942, we baked matzos and conducted a Seder. Our tears choked us and there was a true meaning to the sentence:

[Page 444]

“This year we are slaves, but next year we will be free”. We believed the sun would emerge through the heavy dark clouds and we would come out from darkness to light.

On the first day of Passover, in the morning, we went outside and witnessed a horrible sight: the butcher Feldman was hanging in the center of town at the corner of Brisk, Matseyev and Krutka Streets.

This hanging dispersed all the delusions which had been part of our belief. When we looked at Feldman's thrust tongue and his weeping eyes we saw the frightening ending that awaited us.

After Passover, there were rumors that a ghetto is being planned for our town. We knew that, in other towns, there were already ghettos and that our turn was coming.

The members of the Judenrat hurried to the High Commissioner's office, but they were unsuccessful in obtaining any information from him. He calmed them down and told them not to pay attention to unfounded rumors. However, talk and reality did not coincide. Soon an order came out telling the Jews to exchange their white ribbon for a yellow patch. The patch to be worn in front and the ribbon on the back.

What we dreaded did happen. On 21.5.42, at 4 am, the Germans announced the formation of two ghettos. The first – the “Sand ghetto”- covered the street between Kolyova, Listopdova, Zheromaskigo and Stara Kolyova. The second- the “Downtown ghetto”- was in the area to the left of the Turia bridge- between the Trisk Street, Matseyev Street and the Brisk Street bridges.

In the first ghetto were gathered all those who were able to work and they were given appropriate passes while in the second one were found the old, the sick and the children. Those in the second ghetto knew what their end would be.

The Germans announced a time limit of 10 minutes. In those short minutes people were to leave their homes and move to the ghetto. They took what they could and the rest was stolen by the Germans and the Ukrainians. The murderers had a great deal of loot- everything the Jews had accumulated with hard work.

There was a wall erected between the two ghettos. We, in the first ghetto, knew nothing of what was happening in the second one. However, a Jewish militia man would go from clerk to clerk and inform us about the dire events, each one worse than the previous one.

One night we heard shooting that continued until noon. When it stopped, a Jewish policeman arrived looking petrified. He suddenly burst out in crazy laughter. When he calmed down, he told us a story that horrified us: during the night there was an order given in the ghetto for everyone to take a few items to prepare for work.

[Page 445]

However, when he saw that those being prepared for work were elderly or women or children, it was clear that these unfortunate people were being taken to their deaths. Some managed to hide in cellars and attics, but those caught were killed on the spot.

These poor souls were gathered in the big marketplace. There was commotion and yelling. The children were crying together with their mothers. The air shook with these sounds.

I recall a terrifying picture: in Prazhmovsky's pharmacy there was a pharmacist called Granovsky. He resided in the house of Gelman. During the upheaval in the marketplace, both he and his wife were killed. Their little girl, only three years old, did not know what happened to her parents and she ran around crying: “Mama! Papa! Where are you?” Shlomo Mandel took the child and tried to comfort her. An SS officer passed by and asked the child: why are your crying? Mandel replied: her parents are lost and she is trying to find them. At that moment the officer pulled out his pistol and as he was saying — don't cry, my child — he shot right into her mouth.

The lost souls were forcibly placed on trucks and were driven to the train station. From there they were taken by freight train to the village of Bakhava.

In this village there was a valley formed by the digging of sand for construction. They brought our people to this valley and ordered them to undress. They were all shot to death. Nearby there was a detention camp for Russian prisoners. The Germans ordered these prisoners to cover the bodies with earth. Some non-Jewish eye witnesses spoke of the earth that was moving with the death tremors of those buried there- they had been buried alive. These movements continued for many hours. The people struggled and tried to escape until they died. This “action” continued for three days and 10 000 people were put to death. It was done by SS troops assisted by blood-thirsty Ukrainians. Around this valley of death, the Germans hung a sign saying: Danger! Mines! Do not approach!

When Kovel was liberated in 1944, I returned. We were a small group of survivors who came to pay respect to our fallen brothers and sisters.

Everything was confusing. We could not find our way to the village, but some Ukrainians we met on the road directed us to the mass grave. We began to dig and after one meter we found bodies. Some bodies were only covered with 10 cm.

The men said Kaddish in memory of their relatives and all other members of the Jewish community of Kovel. There was great sadness. The community had been eradicated.

We collected some money and paid for a wire fence around the mass grave. We cried and cried. What else could we do?

[Page 446]

by Ephrain Fishman

Translated by Selwyn Rose

After an exhausting and fear–filled escape I arrived in Kovel one day in February 1942. My disguise as an Aryan had succeeded and I had to find suitable lodging somewhere in the town. I approached the lawyer, Werber, whose address I knew and told him I was a Jew in disguise and sought his help in finding a place. He introduced me as the son of a Polish acquaintance from Równe to a Polish lawyer who helped me to arrange accommodation with the Powel Czun family living at 61 Monopolowa Street.

Every evening this Pole, as I saw while I was there, placed a parcel of sandwiches on his patio that disappeared by morning. I noticed all the time he was very careful when he did this. I followed up on his actions and discovered that Jewish people were coming, snatching the parcels and leaving the place quickly. From then on I too added part of my food. The activity didn't go on for long because after two weeks the Jews stopped coming to take the food – possibly they either escaped from the town to the forests or had perished.

Like all Polish and Ukrainian residents, I visited the labor office to get a work permit and ration card. The head of the office was a man called Wanski and according to rumors was a Volksdeutsche[1] from Poznan, the owner of a factory of knitwear. He controlled man–power in the Kovel area and demands for workers came through him and he would pass on the demand for the daily quota of workers needed to the Judenrat[2].

Because I spoke a number of languages I was employed as a translator in a German construction company, executing various works for the rail system. The manager of the Kovel branch of the railroad was a German named Lutz, together with an engineer called Dehring – both from Germany. Within the framework undertaken by the company, both Jews and non–Jews were employed. The conditions enjoyed by both groups of workers were different – the Christians received a fixed wage with the addition of a daily loaf of bread and the Jews received a minimal wage with no additions. It should be mentioned that there was an internal “arrangement” – the Christians forwent their bread because they had enough of their own and they passed their ration to the Jews.

One day, when the bread was being distributed, a Kovel Jewish man called Paletsky made a comment [in Yiddish] “He is an uncouth Pole” and a second Jew, Goldstein, answered “He should die an uncouth death!” In order not to endanger myself by a slip of the tongue like that, I found it advisable to talk to Paletsky and took him aside and told him to be careful not to talk too much –

[Page 447]

that there were Poles “who understood everything and even ‘the walls have ears’”. He opened his eyes wide and it was clear he understood. From then on our relationship was normal. When I had the opportunity I told him what had happened to the Jewish communities of Równe and Lutsk telling him also of the various programs the Germans had for the workers of the factories. He asked me about escaping to the forest and obtaining papers as an Aryan.

On more than one occasion they hanged Jewish workers in the factory for failing to report to work, as a threat to the Jewish population. One day the manager, Lutz, came to the office glowing and full of joy he told the staff about the bodies of Jews he had seen swinging to and fro on gallows. It was from his story that I learned about the Jews being hanged for smuggling food into the ghetto or not turning up for work.

The corpses, that were left hanging for a couple of days, were removed by permission only after payment of a heavy sum and taken for a Jewish burial.

The situation of Kovel's Jews worsened when a new chief of police by the name of Kassner, owner of a large dog arrived. The popular rumor in town claimed that the dog could identify Jews by smell. The rumor caused waves among the Jews who were gripped with fear whenever they came within sight of the animal. The fear was sensed, apparently by the dog and he would attack them while his blood–thirsty master would shoot the unfortunate victim as a “coup de grace”. He was a sadist by nature. He could not dine until he had killed or tortured someone.

On the first of May 1942 at 8 o'clock in the morning, when all the Jewish workers assembled at the railroad station ready to go to work by truck, the factory manager, Lutz, appeared and organized them into ranks of three and after giving the order to stand to attention, began a derogatory speech haranguing the Jews accusing them of exploiting the status of the workers, commanding them to end the assembly by singing the “Hatikva”. The singing of “Hatikva” under those circumstances was so vigorous and enthusiastic that those present felt it expressing the hope that the suffering of the persecuted people, even on the verge of despair, was accompanied by a spark of faith that Israel will endure and triumph.

I managed to visit the ghetto several times meeting with Riter who was the Judenrat member responsible for work schedules. I advised some of the Jews to escape because the same fate as Równe's Jews awaited them. The following day, early in the morning, sporadic shooting and the explosions of hand–grenades were heard from the direction of the market in the old town. That same morning I was taken back to my home by Ukrainian guards because of a general curfew. Neighbors who lived in the old town spoke of a bitter struggle among the young Jews who had barricaded themselves in the cellars of their shops and the synagogue, and the Ukrainian police.

[Page 448]

About five Ukrainians, at least, were brought out of the ghetto with smashed skulls. After some time we found some comments in Yiddish, Polish and Hebrew on the walls of the houses calling for vengeance against the murderers. The search for Jews in hiding continued for another few days and at the end of the week there were still a few individual Jews being taken to police establishments by Ukrainian police.

I heard the details of the fate of a couple of young Jewesses from the mouth of a German and a Ukrainian. Riva Freidman, a laboratory technician could have saved herself from liquidation because she had a card marked as “Required Jewess” but she refused to leave her mother and sister Regina in spite of the insistence a German who worked with her in the same institute and she was taken together with the other Jews.

Regarding the eventual fate of the attorney from Równe, a member of the Judenrat, I know the following details: He was transferred with his family to the ghetto in the new part of town. He was mobilized with another 50 people of standing in the town, for the burial of the dead. When the work was finished they were ordered to dig their own graves and thus they ended their lives. Their families remained alive for the time being in the ghetto. On that day of liquidation Ukrainian police moved through the town and marked all the Jewish homes. Notices were put up in town warning that anyone found looting Jewish property – would be shot. For several weeks collections were carried out and all the belongings sorted out in special store–rooms. Part of the items were allotted to the Municipality, part to the Ukrainian institutions or the needy families among the population who had applied for assistance and part, especially jewelry and expensive clothing, was sent by rail in special wagons to Germany (I witnessed with my own eyes these transports).

At the end of 1942 there were more than 10 young Jews in Kovel from other towns that lived with Ukrainian or Polish families. They all held papers as Aryans. There was an underground connection between them and occasionally they managed to wink at each other in the street as encouragement. Occasionally they helped each other look for emergency shelter or different lodging. Among these youngsters were a brother and sister Jochet(?) from Lutsk. They forged their papers by changing one letter of the family name to Jiost(?). In my presence they acted as strangers to each other. He worked as an electrical engineer and she as a RÖntgen technician with Doctor Jaborovski – may his name and memory be erased. Dr. Jaborovski suspected her as being Jewish from the first moment she arrived to work with him. During her first days he pestered her with penetrating questions. With the liquidation of the ghetto he told her unequivocally that he would ask for a police investigation of her origins. She escaped to Równe. Her brother was also compelled to escape after the liquidation because the Gestapo was tracking him.

I was informed that he had been arrested in Równe and imprisoned. At the time of the revolt of the prisoners in 1943 – he escaped,

One morning I woke up to the sound of shooting and explosions. I made my way to work because my absence could have awakened suspicions about me but I was returned when only about half–way (on the corner of Monopolowa Street and Warschawski Street) because that

[Page 449]

part of town had been declared under curfew. The firing continued for a couple of hours until noon. That action against the Jews was accepted with complete passiveness by the Christian population and was considered to be of “moderate proportions.” “Only” only about 10,000 had been taken to the lime–pits. The Christians related afterwards that the pits had been prepared a week previously. There were some Jewish people who also bore witness to that. A few days before the liquidation I spoke with some Jews who worked with me at the railroad station. I offered Goldstein some money but he refused it because he knew that his days were numbered. I advised them to escape to the forest but they didn't seem interested in the idea because they had heard from escapees that the Christian partisans weren't willing to accept Jews – especially after the Ukrainian police joined the partisans and sowed anti–Semitism among the ranks of the partisans.

I would like to mention some good things and bad things concerning a few individual Poles and Ukrainians. Among the residents of Kovel 2 was a Polish detective, a Volksdeutsche about 22 years old whose function was to penetrate different circles and discern the origins and intentions of suspicious people who arrive in town. He was furnished by the Germans with special documents and plenty of money. He spread the money and also supplies otherwise unobtainable to everyone who gave him information about the Jews. His name was Artomonov. According to the rumor I heard that at the time of the German retreat he escaped to Poland and was seen in the vicinity of Krakow.

The engineer Czerniak and the engineer Czun lived in the Monopol district and worked in the Municipality. They would inform the Judenrat about orders and instructions that they received from the German administration about new decrees that were about to come into force so that the Judenrat would know of all sorts of operations that were about to occur before the event.

Trapolowski was a Pole who lived in Kovel 2. His son was mobilized and served in the Russian army falling in the first days of the war leaving the father with his two daughters, Yanka and Dora. The elder daughter was a clerk in the Labor Department and directed workers to different institutions according to the requests that came in. Because everyone had to go through her, she received personal details from every worker, she knew every Jew that appeared with an Aryan name and ignored the fact. She would help them to penetrate into Polish companies. She invited me also to their home and introduced me into the circle of young Poles. When the ghetto was liquidated she transferred me to the branch–office of the Labor Department in Maniewicze (Monevitch). The Ukrainian partisans saw her as a representative of the government and one dark night they kidnapped her and the following morning she was found cut into pieces.

Translator's Footnotes

by Asher Peres

Translated by Selwyn Rose

Rumors arrived in the ghetto that a terrible slaughter was imminent and approaching. I went to the gates of the ghetto to see if I could get some more information. The people were gripped by fear and panic, pushing and being pushed, crushed and disorganized towards the gate, sweeping towards the Ukrainian guard and outside the ghetto boundaries.

I exploited that moment's opportunity and fled for my life. I had an acquaintance who owned a bakery situated facing the town's cinema on Mitskevycha Street. I made my way there and to my relief I found my brother there, now together with me in Israel.

We hid in our friend's house for about a week but he couldn't hide us longer because the Germans took possession of the bakery for their own use. One night I left with my brother, alone, abandoned and without knowing where we should go. We got to Macziew Street, crossed the bridge and found shelter in the cellar of an abandoned house. With the dawn we decided to lie low all day and by night to escape to the forest.

Suddenly a Christian woman came in and began to fill a sack with items belonging to the Jews who had abandoned the house. When she saw us she pretended that she sympathized with our plight and began to clasp her hands and promised to bring us bread and milk.

We didn't deceive ourselves regarding this “righteous soul”; we realized our situation was serious but with no alternative we stayed there because escape during daylight would be like just giving ourselves into the hands of the murderers who lay in wait for Jewish blood at every step of the way.

After about an hour a Ukrainian policeman came with his brother, a detective. The policeman was an acquaintance of mine and I was sure he had come to save us and take us to a safe shelter. To my great astonishment he began to threaten us that if we didn't give him gold and jewelry – we'll be killed on the spot. We gave him everything we had. He stripped us of all our clothes, beat us up severely and took us to the Great Synagogue. On the way he warned us not to tell the Germans that he robbed us of the gold, if we did – he'll rip us to shreds.

We arrived at the synagogue at 10 o'clock in the morning. We saw a long line of men and women standing in front of a barrier and next to them an SS officer wearing white gloves. Next to the officer was a bucket full of gold rings. Everyone who went in was obliged to throw a ring into the bucket. Whoever didn't have a ring on the finger – was severely beaten. When it was my turn I was forced to tell the truth that the Ukrainian policeman had taken it all from me

[Page 450]

- my silver, the gold, dollars and even my shoes. The SS officer didn't touch me but in fact attacked the Ukrainian policeman with blows that caused the blood to flow.

I am recording just the tip of the iceberg for the unhappy residents of my town and also for the sake the next generations, of the enormous threat that surrounded me from the very first moment that my feet entered the synagogue: in one corner sat a Jewish man, a pile of bones, his lips moving ceaselessly: “I have waited for Thy salvation O Lord.” Rosh Hashanah was imminent – O, Lord, eradicate the evil decree of Thy judgment, have mercy upon us, inscribe us in the book of life.

While the man was still pleading for mercy in walked a Ukrainian policeman leading a number of small children aged about one year and above.

The Ukrainian policemen – may their name be obliterated — played out a gruesome scene: they tossed the children in the air, as one would toss a ball and on falling the pure little angels were torn to shreds turning into a mixture of blood, ripped flesh and broken bones. All this was performed before the eyes of the horrified mothers.

One of the mothers recognized her child and like a crazed animal she fell upon the Ukrainian trying to save the fruit of her womb from his defiling hands. The murderer kicked her in the chest and sliced the baby into two and threw the two halves of the body at the fainting woman.

After about 7 days in the synagogue the order was given to mobilize 10 men for labor. I was among them and I was ordered to clean the house belonging to Menahem Reissesher(?).

When I returned to the synagogue I found many people missing. They told me that the healthy men had been taken away to the cemetery and there they were given shovels and ordered to dig a trench. When the work was finished they shot all of them in the grave they had dug for themselves.

My brother burst out crying and told me that in half an hour the murderers will return and take all of us to be slaughtered. I felt the blood drain from my face but I didn't panic. In that hour of dire peril I noticed a small opening beneath the Bema[1] of the synagogue. I pushed my brother in there and then tried to get in myself but the area was blocked by the bodies of two women who had been strangled. I pushed them to one side and managed to force my way in.

After about an hour some SS men came with Ukrainian policemen. The vehicles moved up close to the doors of the synagogue and the police lined up in two rows and began to force the miserable people out. From my small opening I looked out at how our dear loved ones went on their last journey. The Ukrainians snatched the smallest children who had been left without their mothers and fathers and smashed their heads on the sides of the trucks. The head came off this one, that one's neck was broken and that one died like a chicken being slaughtered. Thus in agonies such as this our little cherubs went on their way heavenwards.

The synagogue emptied out as they were all taken to their death and the Ukrainian police guard

[Page 451]

alone remained. We began to creep out cautiously from our hiding place to find the policemen asleep near the stairway. We took advantage of the moment and jumped out of the window. The police opened fire on us but we were not hit.

The town was in darkness and my brother and I continued towards our house. It had been destroyed and plundered. We went into the Karlini synagogue. The floor was broken up and we hid in the cellar. We lay there under the floor the whole day. We looked out of cracks in the building and saw Ukrainians coming with carts and wagons, stealing and destroying everything.

At night we left our hiding place and made our way towards the barbed wire fence of the ghetto with the idea of escaping. The barbed wire was very tangled but after a super-human effort we managed to break through. We suffered for months from the injuries we got from the rusty barbed wire.

When we got out we ran to the Golubchek(?) farm. When we got there it was dark and we went into the cow-shed and climbed up into the hay-loft staying there for a few days. Golubchek came every so often to give hay to the horse - but he didn't discover us.

Our situation was desperate. Hunger seemed almost to kill us and we expected to die of hunger. It was already twelve days since we had eaten even the smallest morsel and had no water, our throats were parched and speech was difficult to the point of enforced silence.

When Golubchek came in to feed and water the horse we went down from our hiding-place disclosing our presence to him. Seeing us he became a little fearful and started crossing himself. He saw us as if risen from the dead – specters from the valley of the ghosts because he had been told we had long been taken out for execution.

Golubchek brought us bread and sweet tea and warned us against anyone in the house knowing of our presence because his son-in-law was a rabid Jew-hater and was likely to inform the Germans that we were here.

We stayed in the hay-loft for about half the winter. We were almost naked. We covered ourselves with a thin blanket under the tin roof that itself produced intense cold. Strong winds blew and the cold seemed almost to kill us.

Our good fortune ended when Golubchek's son-in-law chanced on one occasion to come up into the loft. When he discovered us he let out a loud shout that because of us he and all his family would be killed by the Germans. Golubchek intervened and found a way to save us. There were two Jewish men hiding in the Zelena forest who were in touch with Golubchek who gave them bread and other food supplies. He had a talk with them and told them about us being in his hay-loft and one night one of them came to take us away. I went alone while my brother stayed. With great difficulty I managed to stand on my feet and dragged myself after my rescuer. We walked the whole night over rough ground until we arrived at the Zelena forest. On arriving there I discovered the Steinkrok(?) family – the cinema owners.

Our first act was to dig ourselves a trench for shelter in the forest. The digging took us a

[Page 452]

a whole week we were so broken and exhausted. We lay down there the entire night. In the morning we heard the sound of shooting. We escaped deeper into the forest and no one discovered our tracks. I occasionally went to Golubchek together with Steinkrok and we brought back life-supporting supplies of food and water. We brought sacks full of bread, I took my brother with me and we returned to the forest. The pathways were very poor and not well marked and we made a mistake. We sank into deep mud and were a step away from death by sinking in. All night long we trudged along unknown paths and only with the dawn did we find our hiding place. When we arrived we found Steinkrock's wife and his son crying bitterly in the belief we had been executed.

The following day I went on my own to the place where the second Jewish family was staying, hiding in a Christian house in Zelena. They told me not to lose heart because salvation would soon come.

On my way back I ran into a group of Polish partisans armed with pitch-forks. They shouted at me to stop and asked me where I had come from. I answered I was on my way home after visiting a Polish acquaintance. The partisans decided not to kill me for the time being. They intended to capture all the Jews hiding in the forest and kill them all together. On the way they found Steinkrock and his family, my brother and the two Jews. They beat them cruelly and ordered them to report that night to a certain house in Zelena. I told them not to obey because I felt something was not right and didn't bode well but they didn't listen. When they arrived at the house the Polish partisans killed them.

I and my brother went in another direction. We went to a house in Zelena and the house-wife, Drokova hid us in a bunker in the cow-shed. We stayed there for a couple of days. Afterwards we walked until we arrived at Kivertsi. Fierce battles were being fought all over the area between the Russian and German armies but the Russians gained the upper-hand. With the liberation of the area by the Red Army we were released as well and we were saved from the clutches of death.

Translator's Footnote

[Page 453]

by Aharon Weiner

Translated by Ala Gamulka

During the time he lived in Kovel, Mentey walked around with fears that, sooner or later, he would be tasked with the building of ovens meant for the Jews of New York. He fully believed that the Nazi conquests would reach across the ocean. The Fuhrer would rule over the entire world including all the seas. The United States would be overcome and be defeated and he, Mentey, would be invited to establish Majdanek and Auschwitz in Greater New York.

[Page 454]

This murderer thought along the lines of global destruction — a total annihilation of world Jewry. He openly stated that the Earth cannot stand both Nazi Germany and the international Jewish capital. Hitler could not be certain of his conquests as long as the Jewish community of the United States was still in existence.

When I arrived in Kovel, there were no Jews there any more. It was after Bakhava, after the elimination of the two ghettos and after the last Jew brought to the Great Synagogue was massacred. Here and there one could find remnants of the fertile Jewish community of Kovel. There were 6 Jews, in the open, who worked for Mentey. I believe that the number who were hidden by their Polish friends was not more than that.

I once told Mentey: Do you not see that there are no Jews remaining in town? Why do you care if these six will stay alive? He replied: You, Jew, have to understand. You see six Jews only, but I see five million Jews in the United States. They are our enemy as they declared a war of elimination on us. If not for them, there would not have been a World War.

I lived with this animal for many months. Daily I looked at his murderous face. Every day I had to listen to his curses and abuse and I saw the great sacrifice of innocent victims that he performed in his courtyard.

My road of suffering that brought me from Neskhiz to Kovel, to the house of this killer was as follows: when Mentey murdered the Jews of Kovel, there were no craftsmen left in town. The area commanding officer, Shpitura, heard that in Nesekhizh there were a few shoemakers. He demanded that they be brought to him and he would open a shoemaking shop. This is how I came to Kovel to the house of the late Appelbaum. This is where the offices were located.

Mentey had 3 Jewish shoe makers. One night the three escaped. Mentey had the police search for them, but they could not be found. When he heard that there was a Jewish shoemaker working for the area commander he sent a Ukrainian policeman to bring me to him. The policeman told me to come with him. He brought me to Monopoliova Street and we stopped at a beautiful house. Inside was housed a school of Ukrainian policemen, headed by Mentey.

I entered and I saw a character pulling up his pants nervously. He looked at me with suspicious eyes and said: “You are the shoemaker! Come with me”. He brought me to a room and said: You will work here! I had three Jews and they escaped. I hope you will not run away.

In the room I found a woman. Her father was a hatmaker and his shop was near the bridge. I asked her: How did you get here? She told me that she had been hidden by Germans, but they were afraid to be caught and decided to kill her.

[Page 453]

|

|

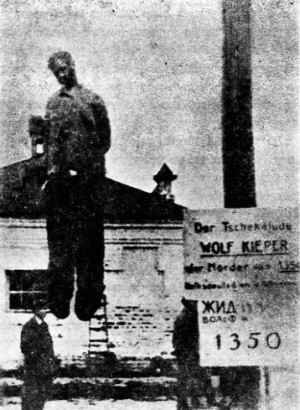

| A Jew named Wolf Kipper who was hanged in Kovel in 1942 |

She was brought to Brisk Street where she was shot, but she was only lightly injured. She went to the doctor and asked him to bandage her. When the doctor discovered that she was Jewish he immediately notified Mentey. After much torture she admitted that she had been hidden by Germans and she was jailed.

Mentey caught the Germans who had hidden her and sentenced them to five years in prison. He left her, for the time being, alive. The prison inspector had recommended her as an excellent dressmaker. This was her good fortune.

Suddenly I saw a young girl in Mentey's house. I did not know who she was.

[Page 456]

I asked her name and she told me she was Bina Roiter, the daughter of Asher Roiter. She had hidden in a house where Germans resided. The Germans lived downstairs and she was in the attic. When the Germans would go out she would come out of her hiding place to collect food scraps from the tables. This is how she sustained herself. However, she felt she had to escape from the house because in the long run someone would discover her. She had saved some gold coins and she decided to give them to Mentey in the hope that he would let her live. He received her, did not hurt her and made her his telephone secretary.

Once Mentey said to me: “These cursed Jews are tormenting me. They do not let me sleep at night. It seems to me that there is at least one Jew still alive.” He was afraid that his loyal helpers, the Ukrainian policemen did not execute the precise job on behalf of the purity of Aryan race. He was certain that the most dangerous enemies of the Reich are still in the town. You see, how can I sleep if my enemies are around me?

What did the murderer do? He found a young Ukrainian boy. He fed him with the best food and gave him a large salary. His task was to search everywhere for Jews. This young boy, may his name and memory be forever erased, was an excellent worker. The next day he brought Itzik the builder with his wife and children. Itzik had hidden for many days in a cellar. When he was brought to Mentey he was crawling. He was bent from the mud and dampness in which they had lived. They separated him from his wife and children. They brought a bit of food to revive him, but he kept some of it for his wife and children. The poor man did not know that they had already been killed.

Mentey used to murder the miserable souls in his courtyard. There was a broken automobile standing there and this is where he placed the one to be killed. The courtyard looked like an abattoir. When I looked through the window I saw human bodies thrown together with dead cats and dogs. Mentey did not want to even use a cart to take out only one or two bodies. It was only when he had several such bodies that he would order their removal for burial.

On 11 Kislev of 1942 35 Jews were brought from to Neskhiz to Kovel- for extermination. Among them were my children. I begged Mentey to allow me to say goodbye, to look at them and hug them. I wanted to give them a last kiss, but he would not listen to my begging. “They have to be killed immediately” – was his shrill command. “There is no place for Jews in this world!”. Still, he softened a little and brought me my oldest daughter. When my daughter saw me, she began to tear her hair out and hit her head on the ground. She screamed with inhuman sounds: “Father, save your daughter. They are going to kill me”.

[Page 457]

I begged Mentey, with tears rolling down my face: “If you cannot spare all my children, at least leave me this child”.

The murderer looked at me and said with stoic calmness: “You must understand that it is impossible to do so. I do not have a place for your daughter. There is no place at all for Jews in the world”.

They were all brought to the cemetery and killed there. When Mentey returned from his “action” he came to me and said: “I did you a favor because you are useful to me. I chose a good and easy death for your children and the other Jews.” “What do you mean by easy?” I asked. The murderer replies: “Usually we beat the Jews to death and we finish it off by shooting. This time I took pity and I did not allow the policemen to torture them. Not only that, but I personally shot them. I am a good shot and I managed it with bullet. I am certain your children did not even feel anything”.

The murderer said what he said and then he ordered me to collect the shoes that were removed from the dead. “Now fit these shoes to the feet of the policemen, their sons and daughters.” Among the pile of shoes I found my oldest daughter's dress. I wrapped it around me the way one does with a tallit and I sobbed out loud.

Mentey did not interfere and he let me cry. When I finally stopped I went into the courtyard. It was a cold winter day — one of the coldest. The Ukrainian boy brought new victims. I saw a Jew shivering with the cold with his feet covered in rags. His little daughter stood next to him completely frozen. I asked him: “Where are you from?” The miserable man replied that he was from Liubomol. “I was caught and now I am waiting for death”. The next day I was shaken by a worse calamity. I saw a Ukrainian policeman escorting a woman carrying a baby with another child following her. As the woman came to Mentey he grabbed the baby from her arms and threw it angrily down. When the killer saw that the baby was still alive, he picked him up and tore him in half. He then threw him on the pile of dead cats and dogs. The following day I saw the poor mother lying dead with the bodies of her children next to her. Near them lay the saintly man from Liubomol with his daughter. The mother's blood flowed together with that of her children as did the blood of the father with his child.

Three days after Purim in 1943, an unusual event took place. All the Ukrainian policemen headed by Shpitura rebelled against Mentey and fled into the forest. At night, Roiter's daughter came to tell me that something terrible was happening. A rebellion? We got up and saw an unbelievable sight: all the Ukrainian policemen stood armed. They broke the furniture with their guns, destroyed documents, burned pictures of the Fuhrer. They approached the German who was lying on his bed and shot him. They were searching for Mentey. Lucky for the murderer that he was sleeping that night in the command headquarters.

[Page 458]

If they had found him they would have cut him into pieces. The policemen destroyed everything and ran away.

In the morning, at dawn, we heard shots. Mentey returned and when he saw that the building was ruined and the policemen had disappeared, he began to behave abominably. He killed a Polish priest who happened to be in his way and he also killed two Jewish construction workers.

We lay in the attic and we did not know what to do: should we surrender to him or should we wait for the right moment to escape? Roiter's daughter went downstairs and informed us that Mentey had returned and was looking for us. We had no choice and we came downstairs. He looked at us and said that he was going to Lieutenant Rapp, the head of the police, to ask him what to do with us. We were certain that he would give the order to immediately kill us. We waited for death. Mentey came back and told us that since we came back of our own good will, Rapp had instructed him to keep us alive.

In our hearts we resolved to escape no matter what as soon as the right occasion presented itself. Since the Ukrainian policemen had gone the building was left unguarded. Mentey was afraid to sleep there and went to Rapp at night. We were alone in the building and we even had the keys.

As we were trying to decide how to escape, ten trucks approached the building. They were filled with German policemen. The Germans were surprised to see us: What? You are Jews? There are still some left of this cursed race? They pointed their guns at us and were prepared to shoot. Mentey interfered in and told the policemen: “Don't touch them. These are my workers.” A few days later all the Germans left the building and again we were alone. I told Roiter: we must run away now. If not, our end was near. She replied that she would not run away since she had nowhere to go.

Mentey used to come back to the building at 7 in the morning. We arose at 5 am and we wrote a good-bye letter to Mentey. We asked his forgiveness for the fact that we were leaving him. We had no work now and we would return when there would be more work. We placed the letter on his desk and we left. One of my Ukrainian friends told me later the when Mentey read the letter he was so angry that he went mad. Roiter's daughter did not join us. When the murderer saw her, he shot many bullets towards her. He only stopped his madness when he saw that her body was like a sieve because of all the bullet holes.

[Page 459]

by Aharon Weiner

(As told by an eye witness)

Translated by Ala Gamulka

Soon after the Germans entered town, they, so to speak, established a civilian government. It was headed by special departments of the police (Sonderabteilung). Representatives of the Jewish community were invited to speak to the German authorities. They were, Mendel, Perl and Dr. Pomeranz.

The three were told to choose a committee (Judenrat). Its purpose was to conduct a census of the population. The first committee was housed in the Jewish Community building on Koshtsiuska Street.

Even in the first weeks the Jews were ordered to give to the authorities their radios, foreign currency, jewelry, cash, bicycles, sewing machines and furs. There were long lines-several kilometers- of citizens bringing theses items. Some waited several days until they were able to give over their belongings.

After that, an order was given to the Jewish Community to provide workers for the Germans. Every household was told to send one worker. Anyone who refused had to hire someone in his place. They were allotted 120 grams of bread daily. The work was difficult and exhausting: they had to harvest potatoes from the fields, load wagons with coal, cut down trees and pack up goods for the front.

The women did housework- cleaning rooms, laundry and other sanitary jobs. They were also employed in factories, saw mills and flour mills. Only Jews were obliged to do this kind of work. The non-Jews were exempt. The Jews also had to hang a yellow star on their doors and shutters. The Germans had, as soon as they entered, ordered the wearing of a blue Magen David on a white background. This rule involved adults as well as children. It was followed by not allowing Christians to meet Jews. As the sun set, curfew followed. It was not permissible to leave the house. Anyone who wanted to sneak into his neighbor's house was in great danger.

***

At the beginning, Kovel had a High Commissioner who did not cause too many problems for the Jews. He accepted bribes and presents and he did not bother or kill the Jews. Highly observant Jews saw in this the results of the blessing of the Righteous from Nesekhizh. He had once blessed the town that it would not know any suffering. However, the calm days did not last long. Someone denounced him to

[Page 460]

The German authorities saying that the Commissioner was too kind to the Jews and that he had forgotten why he was sent to Kovel. He was replaced by a human beast, a sadist, a murderer called Kassner. He came, so to speak, as a simple worker and headed a group of them. He was cunning and managed to befriend the Jewish workers. He questioned them about the relationship of the High Commissioner with the Jews. He wanted to know if the Commissioner was good to the Jews and did not bother them. The poor innocent workers replied that the High commissioner was a good, kind man and that he allowed the Jews to feel calm.

Kassner informed the central command and the High Commissioner was immediately removed from his position. He was sent to trial and the town was handed over to the bloody Kassner.

While the High Commissioner was in his position, Dr. Pomeranz had contact with him. As soon as he was fired, Dr. Pomeranz was arrested and no one knew what happened to him. Certainly, his end must have been the same as that of other Jews in town.

***

As soon as the town was given over to the murderer Kassner, the situation changed completely. We felt that a great calamity was coming. And it was so. One evening Kassner appeared in the ghetto and waited for the workers. He did not come alone, of course, but with his murderous cohorts. They surrounded the ghetto. Kassner stood at the gate and checked the belongings of the men and women in case they smuggled money or food into the ghetto. Twenty people were caught with food. He immediately ordered them all to go down on their knees. Men, women and children congregated to see how this would end.

Kassner slowly pushed up his sleeves and had a murderous grin on his face. He pulled out his pistol and shot one of the kneeling people.

When the first victim fell, Krakover arose and ran away. He somehow was energized by inhuman forces, jumped over the fence and continued to run. Germans who were there caught him and stabbed him with their knives. He continued to run, but he was trapped. Kassner ordered him to be brought back to where he had been on his knees and then he shot him dead. All the people in the ghetto stood and watched this horrible event. Even his wife, his children and his parents were among the spectators. Kassner then arranged for the removal of the bodies, the cleaning of the sidewalk of blood and the erasure of this murderous deed.

Whenever Kassner drove his motorcycle on the street, there was great fear. Young children would jump from the windows into trenches in order to hide.

[Page 461]

One day Arthur Schultz came to the ghetto (owner of the billiard room in Kovel). He was regarded as a “friend” of the Jews and no one suspected he was sent by the Gestapo. He was interested in hearing how the Jews lived in the ghetto. He asked who had arms and who intended to join the partisans. He promised to do all he could to save the Jews from the jaws of death. A few days later Schultz appeared in the ghetto wearing an S.S. uniform. He was once walking on Monopoliova Street and saw Mania Armernik. He killed her on the spot.

***

One day, the wife of Prof. Reuven Erlich was walking with her son and daughter from Tishovsky Street. She had been informed that she was required to go to work. As she neared Brisk Square, the Ukrainians began to shoot in the air. It seemed like a game, supposedly. The women and children were frightened and began to run. The Ukrainians then shot them. The bullet hit the boy and went through his body into the mother. Both were killed. The poor little girl was left alone and began to run. She reached her uncle's house-Dr. Whiteman on Koshtsiuska Street. I, her aunt, Soibel-Whiteman, Raya Bokser (wife of Izsak Erlich), Gitel Ravenko (Burk) and Shoshana Schneider were working there. The child looked so awful that even the Germans had pity on her. It was a heart-wrenching sight. I will never forget her desperate shouts:” I am not a Jew!” “I am not a Jew!' “Don't kill me!” “Let me live!” We managed to calm her down with great difficulty. However, her fate was sealed as she was killed with the elimination of the ghetto.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Kovel', Ukraine

Kovel', Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Jun 2018 by MGH