|

Drawn by Adele

|

|

[Page 22]

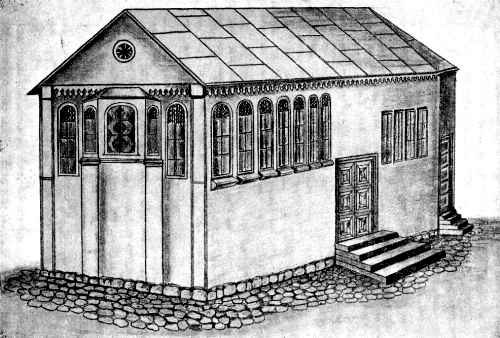

The Klobuck Synagogue

by Adele

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

In far away Australia, the Klobuck Synagogue, destroyed by the defiled Germans, begins to shine before my eyes in the brightest light. No, it is not burned - somewhere this holiness exists, somewhere the divine piety of my childhood years flutters.

The sunlight piously, modestly radiates through the high windows with the colored windowpanes like the silent prayer of Shmoneh Esreh [central prayer of Jewish worship]. These colored rays of sun that light up every corner of the synagogue still shine today in my heart.

Past experiences and childish excitement on Friday nights and holiday evenings in the synagogue emerge in my memory, chandeliers and extra bright oil lamps pour their light over the Shabbos [Sabbath] and holiday Jews who all are joined in holy prayer to the Creator of the World.

And there is the God-fearing Kol-Nidre [All Vows - the opening prayer recited on the eve of Yom Kippur - the Day of Atonement], the hot tears of Jewish Klobuck, the prayers of the men and women pour into the clear, warmed lightness. The Kol-Nidre singing rolls and reaches higher and higher; it appears that the synagogue becomes higher. The sacred painted ceiling disappears and the gates of heaven have opened.

On Tisha B'Av [the ninth of Av], the night of the destruction of Jerusalem, dark shadows spread in the synagogue; the mourning Klobuck Jews sit removing their shoes from their feet and near a small candle they cry out their Book of Lamentations song at the destruction of the Temple.

And after all of the sadness of the people - it again becomes animated with the beaming joy of the people: Klobuck Jews rejoice with the Torah -

[Page 23]

|

|

| The Synagogue of Klobuck Drawn by Adele |

[Page 24]

Simkhas Torah [holiday commemorating the completion of the yearly reading of the Torah and the start of the reading for the new year]. Light, joy, religious ardor merged the individual Klobuck Jews into one congregation that filled the synagogue with singing, dancing in honor of the Torah.

* * *

The Klobuck Synagogue, the small Temple, was destroyed with the kehile [organized religious community]. However, it lives in my heart and soul with those closest and dearest, who were cruelly tortured.

I have tried with a weak effort to bring this synagogue again to paper so that its appearance and its memory will never be removed from our eyes and hearts.

by Gitl Goldberg

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

My mother, Rayzl Leah, of blessed memory, often talked about the Klobuck synagogue and how difficult it was to build and, later, to finish the synagogue.

Before there was a synagogue, everyone prayed in the small house on Zawada where all of the Jews were once concentrated. The plot with the small house belonged to Reb Ahron Wajs, the grandfather of Reb Wolf. Reb Ahron gave this small house as a house of prayer. They prayed there for many years.

They approached the building of the synagogue with very little money. However, they immediately found a generous donor who took upon himself the holy duty of helping to build a house of prayer. The generous donor was – Reb Shimeon Weksler, a wealthy man, who with his wife leased the alcohol factory in Zagorsz. With Reb Shimeon's money, they first properly approached the building of the synagogue. When the walls and the ceiling finally were erected, they again lacked money. Therefore, they made collections in the shtetlekh [towns] around Klobuck. Meanwhile, they prayed in the uncovered four walls.[1]

It took a long time until the completion of the synagogue and the women's synagogue to which led many steps.

The name of Reb Shimeon Weksler, the generous donor, of blessed memory, was carved over the ark for all time.

Translator's Footnote

by Borukh Szimkowicz

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The Klobuck synagogue had a reputation in the area as the tallest synagogue. And in truth the synagogue was very high, sturdily built with long windows. Several wide steps led to the entrance to the synagogue; beautiful wide doors opened into the anteroom. The anteroom was spacious and had three doors: one led out onto the synagogue courtyard, the second – to a small house of prayer and two wide, thick half doors opened into the synagogue. The large anteroom also was used on Shabbos [Sabbath] for the public reading of the Torah.

One entered the synagogue by descending several steps in order to fulfill the saying, “From the depth I call to You, God.” The neyr-tomed, a perpetual flame, six-sided with a brass Mogen Dovid [shield of David – the Star of David] hung from the ceiling a little further, dark red, blue glasses from which always shone a dim light. From my childhood years I remember how we kheder [religious primary school] boys interpreted the words neyr-tomed – the light burns by itself through a miracle, because we could not understand how the shamas [synagogue caretaker] could reach and light the neyr-tomed when it hung so high and there was no ladder in the synagogue.

The eastern wall had three small windows with half round, blue, red and green panes high up. Two dark brown lions carved out of wood stood over the Aron Kodesh [ark holding the Torah scrolls], leaning on the blue tablets on which the Ten Commandments were engraved in golden letters. A little lower, on both sides of the ark, stood two large flowerpots with fruits.

The ark was deep into the wall. Many Torah scrolls were located inside, as were posle [sacred books and pages no long considered fit for use] wrapped with avneytim (cloth bands). They were used only on Simkhas Torah [holiday celebrating the conclusion of the annual Torah reading and the beginning of the new cycle of readings] for hakafos [procession of Torahs encircling the synagogue]. There were several steps to go up to the ark that were on both sides. One went up on the right side and down on the other side. There were two important “seats” on both sides under the ark.

[Page 27]

The rabbi always prayed on the right; on the left, the respected property owner Mendl Guterman prayed. It seems that he inherited his “seat” here.

Near the ark stood the large synagogue's lectern over which hung the Shivisi [first word of the chapter in Psalms that begins, “I stand before God…”]. The sheliekh tsibei [representatives of the community before God] – Reb Dovid Hirsh and Reb Moshe Zander, both shoykhets [ritual slaughterers] – always prayed at the lectern.

Reb Dovid Hirsh, with his stately appearance and long, patriarchal beard stood before the lectern during the Days of Awe for over 40 years and was the reader of the prayers of the Klobuck Jews. Many tears poured out here in the synagogue when Reb Dovid Hirsh wrapped in his talis [prayer shawl] and in his kitl [white coat worn on special religious occasions, which also serves as a burial shroud] sincerely prayed and sang his cantorial pieces with flourishes. An apprehensive stillness engulfed the synagogue when the cantor, with his powerful voice, shouted: “Fearsome and awesome almighty One”. His sons stood on the steps on both sides of him and helped him sing the melodies of the Days of Awe.

Reb Moshe Zander, my former teacher, prayed shakharis [morning prayer] at the lectern. He had new melodies every year that he brought with him from the Radomsker Rebbe. It was known in the shtetl: if Moshe the shoykhet had been in Radomsk before the Days of Awe, they would hear new melodies. His singing drew the musical ones in the shtetl who, because of this, especially came to the synagogue to pray to hear Reb Moshe's new melodies. His praying on Shabbos and his welcoming of Shabbos was sweet.

When one thinks about the Klobuck synagogue, the Synagogue Street swims into one's memory. This was not just any street that led to a synagogue, but a sort of “antechamber” to the house of prayer. Since a Jewish kehile [organized Jewish community] was established in Klobuck, generation after generation, every Klobuck Jew walked through this street many, many times. In addition, to the synagogue and house of prayer, where they went to prayer three times a day – in the morning and Minkhah-Maariv [afternoon and evening prayers] they walked through this street to get to the mikvah [ritual bathhouse]. The khederim [religious primary schools], where mothers led their small children during the summer to learn the alef-beis [the Hebrew alphabet, the basics of education] and where older boys went alone to study Torah, also were located in the Synagogue Street.

[Page 28]

Let us here remember the melamdim [teachers in religious schools] of the Synagogue Street: the teachers of the youngest children were – Reb Itshe Ber with the nickname Kurczak [chicken] and the lame Leibele; Itshe Lewkowicz, Yosef Buchwajc, Moshe Szajowic (Deitsch) and Moshe Yakov Rozental taught Khumish [books of the Torah] and Rashi and to older children.

The hakhnoses orkhim [hospitality for poor Shabbos guests] and the Gerer and Aleksanderer shtiblekh [one room prayer houses] were also located in the Synagogue Street. At that time, the famous rabbi and righteous man, Reb Yankele, may the memory of a righteous man be blessed, lived on the street and his yeshiva [religious secondary school] was located there.

Right after the synagogue stood the small stooped little house of Ayzyk Chlapak. There was prayer and the reading of the Torah there every Shabbos. The Torah reader was Yitzhak Zajbel. The worshippers created a gmiles-khesed [interest-free loan] fund. Three blind women, Zlata, Nakhela and Ritshl, lived in a small room in the house. Reb Ayzyk Chlapak served them as a mitzvah [commandment, often translated as good deed]. Thus appeared the Synagogue Street in Klobuck.

The Young Men of the House of Prayer

In addition to the synagogue, Klobuck also had two houses of prayer – a large one and a small one. The large house of prayer, which really was big, did not rest – not winter and not summer. Day and night. Here they prayed and studied, recited Psalms and simply conversed. The writer of these lines also spent many years in the house of prayer pressed to a bench, studying.

My Klobuck house of prayer remains deeply engraved in my memory… The long, thick, planked benches and tables. The large cabinet of religious books, old books with yellowed pages, the various Talmuds and several set of the Shulkhan Aruch [Code of Jewish Law]. The young men who studied with me remain in my memory: Emanuel Chorzewski, Yakov Granek, Leyzer Klajnberg, Ahron Wajs, Yakov Dawidowicz, Yehiel Rozyn, Yakov Ahron Bloj, Mendl Lipier and Leibl, Moshe the shoykhet's brother-in-law.

We were then the house of prayer's “middle” young men. In addition to us, there were the “bigger” students, that is, the older young men to whom we looked with particular respect.

[Page 29]

The sons of the members of the clergy belonged to this group: Moshe the rabbi's son, Shlomo Menakhem – son of the shoykhet Yakov Borukh, Moshe Rudek, Avraham Mendl Dudek, Levi Wajnman, Levi Kurland.

There was another group of house of prayer young men, “beginners,” very young, who had just begun to engage independently with the Torah. Avraham Goldberg, Mendel Chorzewski, Hilel and Yosef Leib Zoltabrocki, Chaim Dzialowski, Yosef and Yehiel Guterman and Moshe Zelkowicz belonged to this group.

We came to study at the house of prayer at four o'clock in the morning. The first worshippers came an hour later: Yitzhak Lipszic, Yitzhak Szuster, Yehiel Kraszkowski, Shmuel Szperling, Ahron Zajdman, Yakov Fishl Rozental, Yitzhak Zajbel, Ahron Saks and Kh. M. Goldberg. They were the first minyon [group of 10 men required for organized prayer]. The young men-students moved to the small house of prayer as soon as they began to pray.

Every year, Rosh Khodesh Adar [the start of the month of Adar – February-March], the words Mishenikhnas Adar Marbim B'Simkhah [When Adar arrives we increase our joy] were written in large calligraphic letters on the eastern wall of the large house of prayer. Moshe the shoykhet interpreted the acronyn of the word b'simkhah [joyfully]: “Bronfn shtarkn muzn Hasidim hobn” [Hasidim must have strong whiskey]. A long table reached from the eastern wall to the door. The yeshiva young men sat around the table swaying over their gemaras [Talmudic commentaries] and called to one another with: “Rava said and Abba said” [references to Talmudic sages]. The table also was used for the large kehile [organized Jewish community] meetings. Every year, during the time of the Days of Awe, Reb Kasriel the book-seller would spread out his Mokhzorim [holiday prayer books], prayer books, all sorts of books, story books of miracle workers, thick and thin havdalah [candles – used at the conclusion of Shabbos].

Reb Kasriel was not from Klobuck. He especially came with his holy books for the Days of Awe. When several days passed and he had not taken in any money, he created a “lottery.” He raffled off a dozen Khumishim, a Sheyver Muser [18th century treatise – Rod of Chastisement], a Kav Hayosher [18th century moral treatise – The Just Measure] that I could win for only three kopikes. After Reb Kasriel had gathered a sum that the books cost, a drawing took place.

[Page 30]

A number was drawn from a long small bag and whoever had the luck, received the book.

The small house of prayer also was not empty. Here one studied only during the summer and prayed on Shabbosim and the holidays throughout the year. The worshippers were mostly sellers of livestock and horses. They always stuck together as a society, drank and played cards together.

An old well was located in the synagogue courtyard. A large bucket was attached to a long iron chain that served for washing the hands before entering the house of prayer. The clear water of the well was always filled with small stones that “customers” threw in to see how the water bubbled.

I remember how every year, erev [eve of] Yom Kippur before Kol Nidre [opening prayer], Reb Dovid Hersh washed his dressy slippers with the bucket. It was said then that this is a Strikower custom because Reb Dovid Hersh was a Strikower Hasid.

The Community Bathhouse and the Mikvah

A small enclosure was also located in the synagogue courtyard that was feared by the children. Inside the enclosure stood the casket for the dead and the black wagon with which Jews were taken to their eternal rest at the cemetery. When it was seen from the distance that the door of the enclosure was open, it was known that there was a funeral today. The kehile did not own a horse with which to take the bodies; they always had to borrow a horse from a wagon driver.

On the left of the synagogue courtyard, not far from the casket for the dead, was the mikvah. Pious, observant Hasidim immersed themselves almost every day in the morning before praying, both summer and winter. Almost all of the Klobuck Jews went to the bathhouse Friday afternoon. The entire week the mikvah also served the observance of the laws regulating marital life… On the days of Slikhes [penitential prayers recited before the Days of Awe], many pious Klobuck Jews went to immerse themselves in the morning before saying Slikhes.

The mikvah, which was very near the young men of the house of prayer,

[Page 31]

had the first effect of awakening heretical thoughts… The young students began to say among themselves that the mikvah was terribly dirty and they had complaints for the rabbi – how could he justify such an unclean mikvah?

The Klobuck bathhouse consisted of a large room with an entry, where the bath attendant, Shlomo Rozental (Uliarsz) always was found chopping wood for heat and to warm the water. One paid to use the bathhouse. There was no established price, one paid as much as one wanted to give – from two kopikes to 10 groshn. Whoever paid more received another bucket of warm water.

It was always dark in the bathhouse because of the steam. As one became accustomed to the darkness, he first noticed the benches nailed to the wall. One had two choices in undressing: either waiting until someone would get dressed or to lay the package of things on that person's package. Later, when getting dressed, a search began. The clean shirt that they had brought with them to change into often lay dirty on the wet floor. With no other choice, one had to put it on in order to change the shirt one had worn for the entire week.

The bathhouse also possessed three bathtubs in which two or three men at a time would sit. They sat, told stories, mocked and enjoyed themselves. Whoever had time meanwhile waited until they could also slip into the bathtub. After getting out of the bathtub, the bath attendant treated them by pouring a half bucket of water over them… Shrewd men secretly went up to the faucet and took another bucket of water behind the bath attendant's back. The water in the bathtub as well as in the mikvah was rarely changed.

by Batya Zajbel-Izraelewicz

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

The mikvah [ritual bathhouse] bordered our meadow. The mikvah water flowed through a specially created canal onto the surrounding meadows. Streams were created at various places in which our ducks splashed.

Once, on a Thursday night, the ducks disappeared. We looked for them all over and, not finding them, we were sure that they had been stolen. My father, as always, when something unusual happened, responded with a saying, “Never mind, a kapore[1] on the ducks, as long as we have other fowl.”

However, it happened: There was a pious Jew in Klobuck, a God-fearing person, an Aleksanderer Hasid, Reb Yudl Ahron, who went to the mikvah every day to immerse himself. On that Friday morning, when he entered the dark mikvah, he suddenly heard splashing in the water. In his imagination, he saw images moving on the surface of the water.

Frightened, he quickly ran out, went home and, later in the beis hamedrash [house of prayer], said that he had seen ghosts in the mikvah… Several bold Jews, among them my father, took a chance and went into the mikvah. Here they saw our ducks swimming in the mikvah. They were given the nickname, Kosher ones, immersed ducks.

Mrs. Gitl Goldberg talks about the mikvah in her memoirs: My father-in-law always spoke about the problems the Klobucker Jewish residents had in building the mikvah. It seems that gentiles were afraid of the Jewish mikvah that was being built and twice they burned the building that was being built.

A delegation of esteemed Jewish Klobuck businessmen went to Piotrkow to the governor and obtained permission for the regime to protect the religious facilities of the Jews. The Klobuck police turned to the Polish managing committee at the city hall and made it responsible for every case of setting fire to the mikvah. This had the effect that the building of the mikvah was completed.

Translator's Footnote

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

As in all of the cities and shtetlekh [towns] of Poland and Lithuania of the past, Klobuck had its own kehile [organized Jewish community] that was led by three or four people, the so-called dozores [synagogue council]. They decided and carried out all of the communal business matters and managed the revenues and expenditures, consisting of the etat [communal tax] and the like. They consulted with the rabbi in religious matters, for example: in ordering the Passover flour for matzos, in creating eyrovim [wire boundaries indicating a “private area”] to enable the carrying of things on Shabbos [Sabbath]. Such matters were decided only with the rabbi's ascent.

There also were exceptional cases when meetings were called, as for example: when the synagogue or the house of prayer had to be repaired or a new fence had to made around the cemetery and for this purpose money was needed – the entire kehile was called to a meeting. Friday night after the prayers, the shamas [synagogue sexton] banged on the Torah reading table and announced that the dozores had called a meeting that would take place on Sunday afternoon in the house of prayer. Only the leading citizens, the finest business owners in Klobuck were called when hiring a rabbi or shoykhet [ritual slaughterer]. The shamas would receive a list of names from the dozores of who had to be invited to the meeting.

The expenditures of the Klobuck kehile at that time consisted of: the salaries for the rabbi, shamas and shoykhet; heating during the winter and lighting (candles, kerosene) in the houses of prayer; support for the hakhones-orkhim [hospitality on the Sabbath and on holidays for poor travelers], the mikvah [ritual bath] and the cemetery. The main source of revenue was the etat, that is, the yearly tax that every Klobuck Jew had to pay to the kehile. Only those about whom it was known that they were “reduced to a loaf of bread” were freed of paying the etat. There was an evaluation of the income of each and every one and the level of the etat that he could pay was done by the dozores themselves. The list of the tax payers was sent to a high Russian official in Czenstochow by the leaders of the kehile and the general czarist tax administration collected it all.

[Page 34]

In addition to the etat, the kehile had income from the ritual slaughtering. There was a special fee from butchers for slaughtering; this payment also was taken from each family. A “receipt” had to be obtained from Ahron Zajdman for the slaughter of poultry. When the shoykhet received such a “receipt,” he was permitted to slaughter. The receipts cost: four groshn – for a goose or a duck, for a chicken – three groshn. The income for the Resh Khet-Shin (for making use of the clergy – Rov, Khazan and Shoykhet)[1] was an exceptional part of the kehile budget. A special fee was required for weddings, brisn [ritual circumcisions], registering the newborn and eybodl lekhaim [words said between the mention of birth and death to separate them] and registering of death. This income went only to the clergy: rabbi, shoykhet and shamas.

The clergy also had a traditional holiday income. It was the custom in Klobuck that on the day of erev [eve of] Yom Kippur both shoykhetim went from house to house to slaughter the kapores [chicken used in the pre-Yom Kippur atonement ritual]. Every Jew would properly [pay] for the efforts and performed the mitzvah [commandment] of covering the blood after the slaughter. On Purim, each head of household knew that he must send shalakhmones [gifts of cakes and drinks] and Purim money to the rabbi and shoykhet. The same for Chanukah – Chanukah money.

I remember the dozores from my young years: Meir and Shmuel Szperling, Moshe Shmulewicz, Feywl Mas, Dovid Ziglman, Shimsha Lichter, Ahron Mas, Moshe Szperling, Ahron Zaks and Avraham Jakubowicz.

The Jewish communities in the villages around the shtetl, such as Miedzno, Kocin, Ostrowy, Najdorf, Walenczów, Libidza, Łobodno, Złochowice, Wręczyca and Kamyk, also belonged to the Klobuck kehile.

The Kehile During the First World War

The Klobuck kehile leadership began “to reform” itself during the German occupation during the First World War. The three dozores at that time were: Avraham Jakubowicz, Ahron Zaks (the tall Ahron) and Moshe Szperling. The head of the kehile, Avraham Jakubowicz, began to introduce reforms: notices from the kehile were not delivered by the shamas in the synagogue, but through announcements in Yiddish that were hung up in the house of prayer.

[Page 35]

Jakubowicz also reformed the special help given by the kehile so that the needy person did not feel humiliated and that the business owners not use the shamas and the rabbi for assignments that did not belong to their offices. The head of the dozores organized the first inexpensive kitchen for the poor and required that the kehile ask advice on all important questions through frequent meetings.

The rabbi was not happy with these reforms and a conflict arose between him and the democratic dozor [member of the synagogue council]. However, Jakubowicz was sufficiently bold and declared that there need not be agreement with everything that the rabbi said.

Translator's Footnote

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Klobuck, Poland

Klobuck, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 26 Feb 2014 by MGH