|

|

|

[Page 225]

| Woe, the horrifying times! Where did this nightly tempest Blow its dust, where did the morning furiously disperse people Their spilled blood still throbbing in the dirt of the fields. |

| Jacob Fichman: “Bessarabia” |

In October–November 1939, following the destruction of the Polish Jewish community by the Nazi occupiers, the Jewish community of Romania, including Kishinev, assumed an important role among the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe. It was only natural that the Romanian Jewry counting almost a million people will substitute the Polish community and will become the spiritual and economic citadel in Eastern Europe. The Kishinev community would then assume an important part of this role.

The reality was that even in February 1940, after Molotov declared that Soviet Russia did never relinquish Bessarabia and that it belongs to Russia, the Kishinev Jewry abandoned the leadership dreams.

The situation of the Jewish community immediately took a turn for the worst which was reflected in the public and economic life of the people. A lot of community leaders did not believe that the return of Bessarabia to the Soviet Russia is certain or did not see it coming and continued with their regular activities. The community and leaders apathy was fed by rumours that Romania will join Nazi Germany and since the community will be eventually destroyed there is no real advantage to flee to Bucharest or other cities in Romania. And without being prepared, the Jews of Kishinev woke up to the new Soviet regime.

In June 28, 1940, the Red Army entered Kishinev. Immediately after the annexation, thousands of Jews originally from Bessarabia, now living in Romania, came to Kishinev hoping to escape the Romanian fascists. The refugees from Romania crowded Kishinev and caused great pressure on the community services and resources, but the feeling was that they escaped the dangerous Nazis.

Life was changed and new orders were imposed.

[Page 226]

Overnight all community institutions, parties, the Zionist Union and the public life disappeared. The Zionist activity ceased, but the activists still believed that the redemption day will come. The Zionist youth did not stop looking for contacts abroad and ways to continue their work. The Soviet regime did not restrict their work. Only on June 13, 1941, when it became clear that the Romanians and the Germans are ready to invade Bessarabia, the Soviets decided to deport thousands of families, among them a lot of known Zionists. Many family members were separated causing great suffering and many were killed in exile.

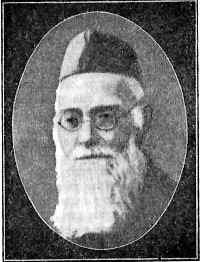

From the beginning of the war on June 22, 1941, Kishinev was bombed every day. The Jewish neighbourhoods suffered the most from the Romanian artillery. Rabbi Judah Leib Zirelson (Tsirelson) was killed in one of the bombardments. His body was shattered by a bomb and was scattered all over his backyard and his head was never found. The community was in shock when they heard that they had to bury the Rabbi without his head.

Rabbi Zirelson, z'l, was elected as head of the Rabbinate in 1910 and served in this capacity for more than 36 years. Even when he was active in Agudat Israel and got some opposition from a large section of the community, he was respected because of his knowledge of the Torah. He wrote many books on Torah and philosophy: Etzei Lebanon (Trees of Lebanon), Gevul Yehudah (Borders of Yehudah), Hegyon haLev (Logic of the Heart), Lev Yehudah (Heart of Yehudah). All his life he defended the honour of Israel and struggled against the fascists and the Cuzists. He courageously addressed the Romanian Senate on 20 Kislev 5787 (1927) and was attacked by a gang of priests causing him to retire from the Senate. He was the first to warn the Romanians that their country will disintegrate if they do not uproot the anti–Semitism. In the last years of his life, as head of the Agudat Israel, he managed to change his attitude toward Zionism and Eretz Israel.

I will not forget the last meeting with him before I left for Eretz Israel in May 1940. We sat in his study, a room full of books and a desk full of papers where he spent many hours

[Page 227]

|

|

writing. We mainly discussed Eretz Israel and the Zionist movement and the Rabbi wanted to show me the articles he wrote about Zionism in the past, in order to prove that Zionism was in his heart. A year after that he sent me, with my father who was still in Kishinev, his urgent request to immigrate to Eretz Israel. He asked for an immigration visa, but in the same day I received the request, I was told that the Rabbi was killed in the bombardment.

Kishinev was shelled for more than three weeks and thousands of Jews were killed. Witnesses told about the atrocities in those days. Some Jews run out of Kishinev, but the majority did not have a chance to survive. In order to save lives, the Soviet regime decided to relocate the population of Kishinev to areas of Russia, far away from the front.

[Page 228]

Few Christians decided to leave Kishinev, but more than 30 thousand Jews, about a third of the population started the march to the safe haven. Every exit from the city became jam–packed of carts, some cars, but mostly people on foot. They left all their properties and belongings and joined the Red Army that retreated to over the Dniester River. These convoys that stretched for more that tens of kilometers were easy targets for the enemy; many were massacred and their bodies left on the way, on the fields and on the banks of the Dniester. Ironically, the survivors of Kishinev were precisely the people who joined in this exodus.

When the people left, the Soviets set fire to most of the institutions and big homes. The fires burned for three days from the 13 to the 15 of July. Most of the Jewish homes were burned in these fires and the Jews who fled understood, when looking back, that this is the fate of the Diaspora Jew; flames that devoured their homes, destruction and all that is left is the walking stick and a small bundle of belongings. The only desire now was a spot to rest and to escape from the enemy.

A new immigrant to Israel who marched this dreadful trek told me: “We did not speak of the future because our only aim was to escape the Nazi murderers. The will to live pushed us to flee, to run away from death, but in our hearts we wanted to survive and arrive to a better place and this hope helped us stay alive. We dreamed that this wandering on the banks of the Dniester and the Volga will lead to the banks of the Jordan River and the Kinneret, the Sea of the Galilee, but only a few were fortunate to fulfill this dream.”

The next stage of the destruction of the Jewish community of Kishinev was the establishment of the Ghetto.

Even if thousands left, there were still about 15.000 Jews in the city who stayed for various reasons. We learned about the fate of the remaining people from the few who escaped and were able to come to Eretz Israel. One of them was H.D. Chernivsky, who was an activist and is mentioned in the Black Book that was published in Bucharest.

During the war years the ruler of Romania was Ion Antonescu,

[Page 229]

a staunch supporter of Hitlerism. His goal was to destroy the Jewish communities of Bessarabia and Bucovina and he succeeded at that very well.

On 8 July 1941, nine days before Romania invaded Bessarabia, Antonescu gave a speech in the Parliament where he presented the plan to rid Romania of the Jewish population. He said: “I think that right now we have the opportunity to eradicate the Jewish population from Bessarabia and Bucovina and to chase them over the borders… and I do not care if the history will call us savages. The Roman Empire actions, that some may consider savagery, culminated in building the biggest empire of all. In our history we do not have a more favourable moment like that. And if the need arises we could use gun power.”

Armed with this “spiritual” motivation, the Romanian fascists marched into Bessarabia.

The next day after the invasion, on July 17, 1941, the Romanian soldiers went from house to house mainly on Podolskaya and Liobskaya Streets and drove out all the males from their homes into the Gestapo headquarters on Sadovaya Street, where the Third Gymnasia once was. They concentrated there about 600 people who were forced to hard labour the entire week and even strapped them to carts to carry water from the river. The ones who couldn't carry out their work were shot on the spot. Only 26 people returned to the Ghetto. Among the ones who returned was Isar Rabinovich, the secretary of Keren Kayemet. In the first 10 days, until July 27, 1941, the Jewish population lived in appalling conditions; they were robbed, killed, maimed and violated. Jewish blood spilled like water. The dead bodies rotting in the yards were buried by relatives in the yards or on the streets. The number of victims reached thousands!

On July 27, 1941, the Ghetto was legally established on Harlamb–Piesvskaya Streets and the soldiers and policemen gathered there about 10,000 Jews. Looking at the map of Kishinev, we see that the Ghetto was established on the same area where in 1770–1790, the first Jewish settlers established the community. During the centuries the community grew and the Jewish population spread all over the beautiful parts of the city. Now they were forced to the small area where the community originated on the banks of the Bik River[1]

[Page 230]

in the poor neighborhoods. During the three months, from July to the end of October, the majority of Jews were massacred and the survivors were deported to Transnistria.

Most of the houses were destroyed and the Ghetto was crowded. People had to fight for a room with a roof and at the end many people shared one little place. The conditions were appalling, no sanitation or other basic necessities. The Ghetto was crowded and lacked bread and water. When the dictator of Bucharest decided to grant the Jews the “right to live,” the Ghetto received permission to administer its own affairs and a council was established to take care of the Jewish population needs. This council had 60 members. In the Ghetto there were a number of physicians, lawyers, engineers, teachers and a large number of former Zionist activists and community representatives among them Leib Belzen, Isar Rabinovich, Yehudith Geler, Shlomo Greenberg, A. Nemirovsky, and many others. The widows of Dr. I. Bernstein–Cohen and M. Roitman were also there at that time, while the other activists were deported to remote parts of Russia.

Among the exiled activists were Shlomo Berliand, the chairman of the Zionist Union, Z. Rosenthal, I. Vinitzky, Tzvi Cohen, Leib Alexandrovsky, Sh. Ortemberg, I. Ritikh, the poet K. Bertini, and others. The activists and workers of the community institutions and journalists were also deported at that time.

The Ghetto council received an apartment on Popovsky Street and started organizing the lives of the despondent crowd. First they organized supplies of flour for bread and water by collecting donations from the people and by stripping the dead (whose number grew every day) of their possessions. For a while they received some support from Bucharest, but this stopped very soon. The water shortage caused the most suffering. In the entire Ghetto there were only two wells near the Bik River and the soldiers were beating the Jews to death when they came for water. Each drop of water was paid with blood! All exits were boarded up with barbed wire and were guarded by armed soldiers who did not let anyone in or out.

The suffering increased with each day. Many died of hunger. Soldiers were patrolling the Ghetto, robbing, killing and violating. Each “visit” by a commander caused terror and pain. When the murderers appeared at the gates of the Ghetto it was sure that

[Page 231]

|

|

[Page 232]

new suffering will befall the poor people crowded on the narrow lanes. The proof in the looting was found in the house of Ion Paraskivescu, the commander of the Police Division 23. He had an entire storage of valuable objects, furniture, rugs and hundreds of stolen items.[2]

This awful situation of torture and looting terrorised the Jews in the Kishinev Ghetto. The will of revenge grew among the youth in the Ghetto, but they were isolated from the rest of the world and did not have a chance to obtain any weapons.

A month after the Ghetto opened on the 1st of August 1941 an order was received to organize a group of 450 young, intellectual people under the age of 30 for various works.[3]

Following this order, the soldiers amassed the young men and women in the “lime pit” on Yacovlevskaya Street. They had to pass a German officer's inspection, who decided if they will work or set free. 200 young men, 200 young women and 50 people aged 45 were selected and at 3:00 PM they were marched towards the Ogheiev suburb to work. At 9:00 PM only 39 older people returned and brought the tragic news that 411 people were shot neat the Vistranitzky Station. They were tossed in the ditches and the survivors had to cover them with earth. Among the victims were: engineer Sh. Shwatzman, engineer Krasniansky, Mrs. Milshtein, the Gosberg family and others. The German officer informed the survivors that this is a collective punishment for the support the Jews gave to the enemy. It's impossible to imagine the terror that this brutality caused in the Ghetto. A few days after the massacre, a group of people from the Christian village next to the Ghetto came to complain about the stink and the blood that was oozing from the mass graves. The Ghetto council sent people to cover the graves and when they finished this gruesome job, they said the Kadish Prayer for the victims.

[Page 233]

For the wounded there was no other joy than the verdict to stay alive a few more days. The Community organized a hospital in the building of the Old Talmud Torah, a pharmacy, an orphanage, an old folk home and a soup kitchen for the needy. The authorities demanded every day 600–1200 people for forced labour. People went to work willingly because they left the Ghetto for the upper area of the city and were given a piece of bread and water at the end of the day, sometimes a few cents. One day, 100 people were sent to the village of Vandzuru and only 20 seriously wounded returned! They were beaten by the guarding soldiers.

After a week an order came from the military commandment to send 550 people to work at the lime quarry in Edinitz, some kilometers away from Kishinev, to carry stoned for building kilns. The community leaders refused to send the people arguing that it is very dangerous to have people working outside Kishinev. The authorities lined the entire community leadership on the street and took away every fifth person as hostage. They threatened that if the people do not report for work by noon, the hostages will be shot. Immediately people volunteered for work in order to save the community leaders. About 550 people were sent to Edinitz. After a week only 220 returned because the commanding officer claimed that there was work only for 330 people. Many military trains were passing through Edinitz and when they stopped, the soldiers came out, beating the working Jews and sabotaging their work. Once the soldiers accused the Jews of laying stones on the railway in order to sabotage the transports and violently beat them up. Most of the people were seriously wounded and 20 critically wounded had to be hospitalized in the Ghetto hospital. A few days after, an order was received to send back the wounded people to Edinitz for investigation. It became clear after a while that the 330 people were prosecuted and condemned to death. They were executed in a forest near Strashny.

When the Jewish New Year 5701 (1941) approached the persecutions increased. On the holiday of Simhat Torah (October 4, 1941) the order was given to liquidate the Ghetto and to deport all its inhabitants to Transnistria.

The first transport of 1000–1500 people started marching on the Orgheiev–Rezina road. Most of the people were forced to walk as only a few carts were available. They were guarded by armed policemen. At the exit they were met by soldiers who beat them and robbed them of their last few possessions.

Most of them perished on the icy snowy roads and only a few crossed the Dniester River.

Every Thursday and Friday a new convoy was assembled. People were running from street to street, from one apartment to another in the desperate hope to avoid deportation

[Page 234]

or hoping that the deportations will stop and they will be saved.

The deportations continued. The community leaders endangered their lives in order to help the community. The lawyer A. Shapirin, a member of the community council, dressed in an officer's uniform, found a way to fly by military plane to Bucharest to plead for the cessation of the deportations.

The Federation of Jewish Communities in Bucharest sent an envoy, the Christian lawyer Mushat to review the situation of the Kishinev Ghetto and to save whatever could be saved. His efforts were not successful. On the 30th of October 1941 he telegraphed: “The trial is lost, all the people were found guilty. Bucharest should investigate.”[4] This was the cruelest verdict given to the Jews of Kishinev. Some people still tried to escape this circle of death, but did not succeed. On the last week of October 1941 they sent thousands of panicked telegrams to organizations and relatives asking for help and protection. They did not know that all their efforts were futile and hopeless and they did not want to accept their destiny until the last moment. From the coded letters that were sent in those days we see that they still hoped that their brothers in Bucharest will provide some help.

M. Carp published in the Black Book, a number of desperate coded telegrams which were sent in the last days, before the annihilation of the Ghetto. Here are some:

October 22, 1941 Kishinev–Urgent–Censored

“Father is sick and desperate. Send medication immediately! Address: Shwartzberg–Halperin. Please answer at once. Mother.”

October 22, 1941

“Telegraph at once if the 14 sick patients can receive the medication. Telegraph to Dr. Feigel Pinchevsky. The situation is very critical. Mila Sonya”

All efforts were hopeless. The order was given to empty the Ghetto. The lawyer Shapirin was advised to remain in Bucharest, but he refused to save himself and chose to return and join in the common destiny.

The desperation was limitless. Many committed suicide instead of taking to the road in the rain, without water or food, chased by the brutal gendarmes.

About 9000 deportees arrived to Bogdanovka on the bank of the Dniester and

[Page 235]

were shot by the Ukrainians near the building of the local “Sovkhoz.” Many Jews from Odessa also perished in the same place.

On the 31 of October 1941, the last transport left the Kishinev Ghetto. Only 50–60 people were left in the Ghetto. Some had special permission from the government and some had contagious diseases. A few dozen Jews succeeded to run from the Ghetto and went to Romania, only to be found after someone notified the authorities that a clerk helped them escape. When arrested, the clerk released all the names to the police. The escapees were found and arrested in Bucharest. They were returned to Kishinev, where they were kept until May 1942 in an abandoned building in the Ghetto and then shipped to Transnistria. A few succeeded to return to Bucharest and some even made it to Eretz Israel.

Footnotes

We cannot conclude the Martyrdom chapter of the Jews of Kishinev without recalling the atrocities they suffered in the many locations they passed together with other remains of the Jewish communities of Bessarabia. Transnistria and “Struma” were at the forefront of these locations. We will not give here details about the hell the deportees suffered in Transnistria, but we will present a letter from a man from Kishinev, who miraculously survived the atrocities and now lives in Israel[1].

“The name of the death camp was Akhmitchetka (Acmicetca), like the neighboring Ukrainian village in the Dumanovka region, the Golta district, on the bank of the Bug River. About 2 kilometers from the village, in the valley, there were four long barns covered with hey and straw, which served as a pig farm during the Soviet Regime. A few huts and some stone buildings where the farm workers lived were located on the hill. In the spring 1942, an order came from the Prefect of the Golta region, M. Isopescu in coordination with the commander of Dumanovka, the lawyer Blanaru, that all the Jews who were deported there and that could not work in the fields or at road paving, to be concentrated at the Akhmitchetka pig farm and left there to die of hunger and thirst.

On May 10th, 1942 (the National Day of Romania), the order was implemented.

[Page 236]

People who were weak, sick, old, women and children from all over were herded to this awful place, later named “toite lagger” (the death camp). A tall barbwire fence was built and a deep ditch was dug around the camp with Ukrainian policemen guarding so no one could escape. Thousands of people were kept in these inhumane conditions without water or food. Whoever still had some valuables, gold or precious stones, sold them for ridiculous prices to the policemen in order to buy a slice of bread or a piece of fruit to quench their hunger and thirst.

The remaining Jews knew what happened to their unfortunate brothers and even if they had a strong desire to survive, they couldn't because the Jews could not move from one place to another. After many attempts, the Jews of Dumanovka finally got permission in July 1942 to go to the camp and bring a cart with food. We did not have a lot in our basket, but we saved a few scraps by fasting once a week and collected them for the less fortunate. The news that reached us just shook us to the bones. They were starving to a slow death and dying by the hundreds. One Sunday at the beginning of August 1942, I was given the task to take the food cart to the camp. A dreadful scene unfolded before my eyes. Even from the distance I could hear shouts of joy. The people gathered next to the fence and waived their hands. When I approached I could not look at the unfortunate people, naked and barefoot with only some rugs to cover themselves. I saw men and women, children and young women looking like skeletons, dirty, covered with wild hair. Their stomachs were swollen and some were searching for a few grass blades in the dirt. I saw some women cooking something on a weak fire. I saw some people who were too weak to stand on their feet, only a spark of hope remaining in the eyes. Among them. I recognized some people who marched together with me from Kishinev to Transnistria. They were once healthy and strong, now they hardly could reach to get the piece of pitiful bread.”

Footnote

In the winter of 1942, at the time of the Transnistria tragedy, when the criminal hand of the Romanian Hitlerists reached all the Jews of Bessarabia and Bucovina and deported them to the hell over the Dniester River, a partial solution appeared–“Struma”–a boat of 170 tons used for transporting cattle. 769 people overcrowded this boat in the hope that they will be saved from persecutions and from being deported to Transnistria and get to Eretz Israel. Among them, a number of

[Page 237]

|

|

[Page 238]

Jews from Kishinev and other places in Bessarabia. They had a bitter fate – instead of arriving at the promised shores, they ended up at the bottom of the sea. The criminal British government of the time did not show any humanitarian compassion toward the 769 Jewish souls and did not let them disembark in Eretz Israel and on the way back the boat was torpedoed and all the passengers drowned in the middle of the sea.

The sole survivor was David Stoliar from Kishinev. He was 20 years old at the time. Fate made him the sole survivor in order to tell about the suffering of the Struma refugees who could not be saved.[1]

Here is his account of the last moments of the Struma refugees as published in the book “The Struma Affair.”

“It was on Sunday, the 22nd of February 1942 (5th of Adar). After weeks of never ending waiting, desperation and hope, we received two telegrams that elated our spirits. One was from a benefactor in Eretz Israel who encouraged us not to despair (I don't have words to express what this telegram meant for us, the desperate people!) and another one was from Rabbi Stephen Weiz from New York, who informed us that he obtained 2000 certificates to go to Eretz Israel and that we will also receive some of them. This was a day of happiness and joy. Every person saw the end to suffering getting closer and closer. That night, we all imagined our life in Eretz Israel!

In the morning a tug boat approached us and we feared the worst, but we hoped for the best. We spent more hours of waiting, between hope and despair. At 1:00 PM a boat full of policemen came to untie the Struma. They told us they are taking us to a nearby spot for disinfection. One of the policemen said: “They are going to return you to the Black Sea to Burgas in Bulgaria or to Constanta in Romania.” These words instilled great panic among the refugees who could not take this dreadful news after a day of hope. The whispering between the Head of Police and the Captain just increased the fears. We refused to disembark and the policemen left the boat. After a short while another boat with 80 policemen approached the Struma, but the refugees did not let them board. The captain did not resist at all. He collected his belonging and was ready to flee. We did not trust him, although he had signed and promised to take us to Eretz Israel.

At 10:00 PM the boat made it to the Black Sea, about 5 km from the shore. Here the tug boat disconnected and we heard shouts: “You are going to Burgas!”

Food supplies were very low on the boat because the last shipment of food came more than a week ago; we also knew that the boat does not have enough fuel for the trip.

No one closed an eye on that night and no one dared to say a word.

[Page 239]

We sat in shock the whole night. Tuesday morning I went on the bridge and I could see that the boat advanced about 3 km from the shore. We started to repair the engine; the captain told us that we are still in the territorial waters of Turkey. The captain was afraid to speak, he told us that when the engine will function he will let us know and he will return us to Turkey.

The boat did not move. The sea was calm. At 9:00 AM we heard a strong explosion and the boat sank in a few minutes. I was thrown into the air and when I landed in the water I saw only a few dozen refugees struggling in the water. Awful screams of men and women could be heard. Wreckage from the boat floated in the waters and some of the refugees tried to hold on and I did the same. The waters were ice cold. The refugees weakened by the cold and the waters sank one by one. By noon I realized that I was all alone. I was wearing a short leather coat which helped me endure the cold. It was frightening to be the only one in the middle of the sea. The birds of prey attacked the corpses and the food debris floating on the waters. At sundown I saw a man floating, coming towards me. When he approached, I recognized that he was the second officer Lazar. He was very tired. I helped him on my bench and let him rest a while. When I asked him what happened he said that he saw a mine floating towards the boat and called the captain, but in the mean time the boat sank. He told me that he saw the captain in the waters a few hours, but eventually he drowned. He knew that no one survived. We decided not to fall asleep so we will not freeze. We warmed each other as best as we could.

The night passed; the second officer became very weak and fell into the waters and drowned. His death distressed me a lot. I could see the shore in the distance and I decided to swim, but after 200 meters my strength gave up and I decided to return to the bench. I was afraid I will have the same fate as the second officer and I decided to put an end to my life. I had a knife in the pocket and I tried to cut my wrist, but my hands were frozen and I could not do it. Without any choices, I waited for the next…

All of a sudden I saw a cargo ship approaching. I called with all my strength for help. It passed me within a few meters, but did not stop to help. The sailors signed with their fingers that they do not understand and I thought they told me to swim to shore. They did not understand that I do not have the strength to swim or even take my life!

In these desperate moments I saw a boat coming towards me. This was the rescue boat sent from Shila (the small Turkish village on the Black Sea) with a few Turkish sailors with all the recue tools needed. They hoisted the corpse of the second officer that was still nearby

[Page 240]

and one more body. They put me on a stretcher, provided first aid and brought me to the village. They cared for me and gave me an injection.”

In the spring of 1942, the few Jews who fled from the Kishinev Ghetto to Bucharest are returned to Kishinev. One of the survivors who returned in April described the city. Kishinev was cleaned of Jews. The main streets that were once bursting with life were now empty as if the Jews never lived there.

The spring sky, the trees in bloom and the fresh smell of greenery seem to be there to cover the Jewish blood spilled in every corner. On the Sinadini Street I met with an acquaintance, a bank clerk who helped me a lot in the past. When he saw a live Jew on the street he could not believe his eyes. First reaction was: “You are still alive? I was sure that you were dead.” That's what the “good goym” were thinking. The “goy” felt he made a mistake, but the Jew distanced himself rapidly. He roamed the streets in the hope he will meet another Jew, but, alas, they were none left.

He entered the central city park, one of the most beautiful corners in the city. Everything was blooming here, the trees on the boulevard, the flowers, the birds sang. In the middle of the park stood the statue of A. Pushkin, gazing at the park with his sad eyes. On the base there is an inscription of two lines of his poem:

“on the strings of the lyre

I wandered here to the Northern wasteland…”

Pushkin did not know then, that 110 years after he was exiled from Moscow to Kishinev, his sad poem will have a new meaning.

One of the last Jews of Kishinev who stood in front of Pushkin's statue felt that even if nature is alive around him, he is in a desolate wasteland.

Footnote

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Chişinău, Moldova

Chişinău, Moldova

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 03 Dec 2017 by JH