[Page 5]

With Publication of the Book[1]

By the Book Committee

Translated by Allen Flusberg

After a great deal of labor and continuous effort that has been invested in the gathering and compilation of the material, we are now presenting this Yizkor Book to those who hail from Dobrzyn–Golub.

Through the publication of this book we have sought to erect a memorial to the martyrs of the town, who perished by the hand of the Nazi foe and their henchmen, may their names be blotted out! In these few pages, however, it has not been easy to recreate the memory of this flourishing town—its prodigies, students and ordinary people—especially since only a remnant of its many inhabitants have survived. Nor has it been easy for the few who did remain alive to recall again those days of terror in which their most precious possessions were lost to them—their parents, siblings and children.

Yet we knew how important this undertaking to immortalize our town was, and therefore we insisted on eliciting contributions from our members and encouraging them to write, knowing fully well that they were not skilled at writing.

And indeed we did not toil in vain. In various sections of the book the town has been portrayed in all its richness: its houses and streets; its institutions and organizations; and its prominent figures. And we are inspired again as we recall the activities of the community leaders, whose highest priorities were their concern for the community and their love of humanity.

But how appalling and nerve–racking the descriptions of the Holocaust—accounts written by those of our brethren who experienced its terrors in the flesh. And even if we have heard and read of these things many, many times, our hair stands on end again and we are seized with terror as we contemplate these horrific events. The names of those we grew up with in the town, and whom we knew so well—the names of the martyrs—echo and resonate in our ears, demanding justice for their deaths, for the crime of their murders.

May this book serve as a memorial to the martyred members of our community, and may it provide some comfort, however small, to the remaining Dobrzyn townspeople in both Israel and the Diaspora.

Translator's Footnote

- From My Town: In Memory of the Communities Dobrzyn–Gollob, edited by M. Harpaz, (published by the Dobrzyn–Golub Society, Israel, 1969), p. 5. Return

[Pages 6-7]

From the Historical Sources[1]

Translated by Allen Flusberg

Dobrzyn

Until the end of the 13th century, Dobrzyn on the Dreventz[2] River, in the province of Plock, was a suburb of the city of Golub, which was located on the other side of the river, and served as a border-town between Prussia and the Kingdom of Poland.

Only in the year 1684 did the owner of the estate, Zygmunt of Działyń[3] (who was also the lord of the church of Działyń, the governor of the province of Kalisz, and even the mayor of Inowroclaw[4]), grant the citizens of Dobrzyn the right to choose their own independent mayor, who would serve also as a judge. Alongside him were two of the elders of the town, who together with him made up a court of law. With this he [Zygmunt] provided the residents with several additional rights: the right of residency; the right to build houses, to acquire land, to work the soil, and to plant orchards.

This is the first document that indicates the granting of partial independence to Dobrzyn—a document that was ratified again by his [Zygmunt's] son, Jakob Działyński, in the year 1721. Only in the year 1789, after Golub was annexed to Prussia (following the partition of Poland), did Ignacy of Działyń, governor of a province of the kingdom of Poland, grant independence to Dobrzyn, bestowing on it the status of a city, with a mayor at its head.

The town, whose buildings were wooden, burned down completely in 1857, after which it was rebuilt with buildings constructed of brick.

The roots of the Jewish community in Dobrzyn are ancient. This community suffered great hardship during the period of the wars between Sweden and Poland. Only a small number of Dobrzyn's Jews were left alive after the cruel riot by the forces of Czarniecki[5] (1656). But despite all this the community continued to exist, and already in the year 1765 the number of Jews within the “synagogue” reached 765, while the total number of Jews in that year within the bounds of Dobrzyn was 1,082.

The nobility (“szlachta”) of the city often plotted against the rights of the Jews by legislating anti-Semitic laws in the sejms[6]. The Church also restricted their movement. Thus, for example, by decision of a high clerical council, all the Jews were concentrated in a special area (1783).

In the year 1857 the town had a population of 2,452, of which 702 were Poles, 140 were German, and 1,610 were Jews. The Jews dealt mostly in crafts and petty trade; a small number of them were employed in agriculture.

At that time the town had a church, a cemetery for each of the communities, a synagogue, a city hall, an elementary school, a customs house, and a post office.

Twice a week there was a market day, and there were fairs six times a year.

Golub

Golub on the Dreventz River was in the province of Chelmno. In earlier times it was also called Golba. It extends along the foot of a mountain on whose peak the nobleman Konrad Sach (or Schach), a Crusader, built a magnificent castle in the year 1300.

Prince Dobrzyn, an estate owner, granted the Crusader order 50 fiefs of land in the vicinity of the castle. In the year 1410, after the defeat of the Crusaders in Grünwald[7], Dobieslaw Puchala established an order of the infantry knights there and conquered the fortress. In the year 1422 Wladyslaw Jagiello took the fortress during a storm, captured the entire region and ordered that the towers should be destroyed[8]. After a peace treaty was signed in the district city of Torun (the birthplace of Copernicus), Golub became a demilitarized city.

In 1605 Zygmunt III[9] transferred authority over the city to his sister Anna, who settled here and even established an orchard of fruit trees near the fortress. She cultivated this orchard exquisitely. (The remains of this orchard, consisting of fruit-bearing trees, were visible until the 1930s.)

The residents were employed mostly in trade of grain and wood. There were two churches in the city, one Catholic and one Protestant. Likewise there were the following: a synagogue, city hall, post office, telegraph station, courthouse, customs office, salt warehouse, and two schools—one for the Catholics and one for the Protestants.

In the distant past all the land was the property of the Church. Two heads of the Church—Simon Gallikus and Loczek of Stolno—handed them over to land tenants to farm. The resident land tenants were forced to pay tribute to the crusaders, as well, and some of them even served as soldiers in the Order of the Knights.

In 1655 the Swedes conquered the city and the fortress. In 1772 Golub was joined to Prussia. In 1781 they began the construction of a Lutheran church there.

In the middle of the 19th century the population was 4,000, of whom about 1,400 were Jews. The first Jews who arrived in this region came after the division of Poland, when the region was annexed to Prussia. They were employed mostly in commerce: textiles, grain, wool and furs.

The Jewish community was organized and well-established. The transfer of the entire region to Poland (after World War I) strengthened ties with the nearby Dobrzyn community.

Translator's Footnotes

- From My Town: In Memory of the Communities Dobrzyn-Gollob, edited by M. Harpaz, (published by the Dobrzyn-Golub Society, Israel, 1969), pp. 6-7. Return

- Polish: Drwęc Return

- Działyń lies about 10km south of Dobrzyn. Return

- Inowrocław, a city lying about 80km southwest of Dobrzyn Return

- Stefan Czarniecki, was considered a Polish hero because of his resistance against the Swedish invaders. To the Polish Jews, however, he was viewed as a despicable villain whose forces had massacred the Jews. See the following two links:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stefan_Czarniecki,

http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0005_0_04788.html Return

- Sejm = local parliamentary council (Polish) Return

- Also known as the Battle of Tannenberg. See the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Grunwald Return

- For additional details, see the following link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gollub_War Return

- Zygmunt III, King of Poland. See the following link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sigismund_III_Vasa Return

[Pages 8-9]

|

|

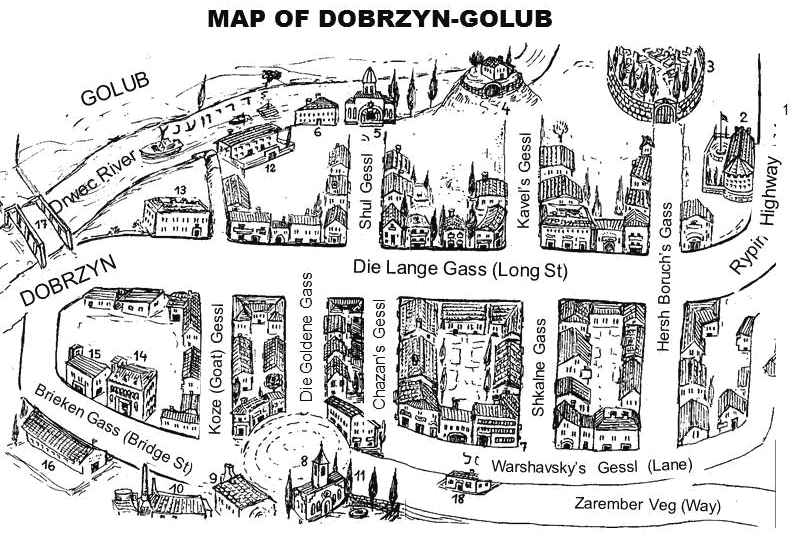

Key to Map

Translated by Allen Flusberg

- Underwear factory

- Barracks

- Jewish Cemetery

- Roker's Mount

- Synagogue

- Bet Midrash (Jewish Study Hall)

- Government (Public) School

- Market Square

- Flour Mill (Isaac)

- Power Station & Sawmill (Lipke)

- Polish Church

- Alexander Cheder

- “Reformed” (metukan) Cheder

- Fire Station

- Library

- Customs House

- Dobrzyn-Golub Bridge

- Pharmacy

|

[Page 10]

And You Shall Remember[1]

Translated by Allen Flusberg

And you shall remember and not forget,

Your eyes always seeing

All that was…

And is no more…

And your heart will pine for them:

For your parents, brothers and sisters,

For your childhood friends,

Killed in the field of slaughter…

And you shall embrace their memory

Forever, for all eternity. |

Translator's Footnote

- From My Town: In Memory of the Communities Dobrzyn–Gollob, edited by M. Harpaz, (published by the Dobrzyn–Golub Society, Israel, 1969), p. 10. Return

[Pages 23-24]

In the Shadow of the Destruction[1]

by the Editor

Translated by Allen Flusberg

About three decades have passed since the terrible Holocaust that utterly devoured the House of Israel. As the Nazi warriors swept across the countries of Europe, they consumed the Jewish communities in the towns and cities, murdering women and children, the young and the old, with a furious hatred; and torturing those left alive with hair-raising torment…

And the enlightened world stood by, washing its hands in innocence, without coming to the rescue of these blameless millions, whose only crime was the fact that they were Jews—members of an ancient people that, to its misfortune, had been forced to live among other nations.

During the Holocaust it became clear to us, more than ever, that there was no one the Jews could pin their hopes on but themselves. It was then, in the face of a hostile world, that the expression “all Jews are responsible for one another” became profoundly meaningful. The expression was articulated most unequivocally in the establishment of the State of Israel and in the displays of devotion and volunteerism by the Jewish people throughout all of their Diaspora.

For a generation we have lived in the shadow of this terrible Destruction, while our brethren, the remnant of survivors of the Holocaust, have dwelled with us and among us, bearing within them the memory of its terror. The pain and agony of that time have not faded away; on the contrary, they have continued to grow deeper.

The significance of what was lost in the Holocaust has become more apparent with the passing years, as our admiration for all that once was and is now gone has been rekindled and has intensified—our esteem for all those communities, poor perhaps in substance but rich in spirit; our reverence for the troops of learned sages who created the idealized image of the [religious] prodigy; and our admiration for the myriads of ordinary folk who displayed devotion to one another and faith in the Destiny of Israel.

The community of Dobryzn-Golub was only one of many, a Jewish community that had spun a rich web of Jewish life as it struggled for subsistence and livelihood while it was maintaining a spirit of transcendence and vision. Among the many memories of this town that survive are some that are heartrending, and yet others that are heartwarming.

Possibly the generation that did not know this community—the children of those who originated from Dobrzyn-Golub—will read this Memorial Book and from it become aware of their parents' roots, lives and dreams. And perhaps this perception will enrich their lives, as well, with deeper meaning.

|

|

| Dobrzyn was heart. Dobrzyn was feelings, charity, anonymous giving.[2] |

[Page 24]

| El Malei Rachamim: God, full of compassion, Who dwells above, provide complete rest under the protection of the Divine Presence, within the celestial heights reached by the holy martyrs and pure ones—shining as bright as the firmament—to the souls of the thousands of members of the martyred communities of Dobrzyn-Golub—men, women and children—who were murdered, slaughtered, incinerated, suffocated, or buried alive by the evil ones, Hitler's executioners and their lackeys—may their names be blotted out—during the years 1939 to 1944. May they find rest in Paradise; may the Compassionate One therefore bind their souls in Eternal Life; and may the Lord be their legacy. And may they rest peacefully in their resting place, and let us say Amen![3] |

|

|

Photograph of memorial plaque memorializing

the community of Dobrzyn-Golub[4] |

Translator's Footnotes

- From My Town: In Memory of the Communities Dobrzyn-Gollob, edited by M. Harpaz, (published by the Dobrzyn-Golub Society, Israel, 1969), pp. 22-23. Return

- From page 22 of reference cited in Footnote 1. Return

- Variants of the prayer El Malei Rachamim, memorializing departed individuals, groups or entire communities, are recited at gravesides, at various synagogue services and at other memorial services. For alternative English translations see, for example, the following links: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_male_rachamim; http://www.ou.org/yerushalayim/yizkor/emman.htm Return

- From p. 25 of reference cited in Footnote 1. The Dobrzyn synagogue is portrayed near the top, between the two eternal flames. The Hebrew text translates as follows: For an everlasting memorial, on Mt. Zion in Jerusalem, to the martyrs of the community of Dobrzyn-Golub and vicinity (located on the Dreventz River, Poland) who were exterminated, incinerated, murdered, or buried alive by the Nazis and their henchmen—may their names be blotted out—in the years 5699 to 5705. Earth, conceal not their blood. And may their souls be bound in Eternal Life. —The Dobrzyn-Golub Townsmen Organization, in Israel and in the Diaspora. A Declaration of Destruction. Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Golub-Dobrzyń, Poland

Golub-Dobrzyń, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Lance Ackerfeld

Copyright © 1999-2025 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 26 Nov 2016 by LA