|

|

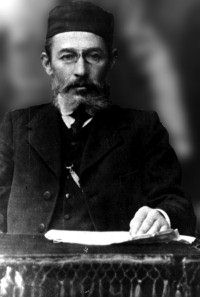

Rabbi Dovid Levin

Bassia Levin ne'e Rabinowitz

|

|

[Page 5]

one of the very few to be freed from this hell. It is no wonder that the widespread opinion among us was, “It would be best if the Ghetto were set up already; there the Lithuanians would not be able to cause us any harm, at least, we'll live among Jews!.. .”

In preparation for the transferal of Kovno's 30,000 Jews to the Ghetto, a Jewish committee (Komitet) was established to ease, from a technical standpoint, the relocation. Little by little, we dared visit the courtyard of the 'Komitet,' the Jewish committee that started working at Yatkever (Dauksos) Street 24. We wanted to see who were the communal workers who took the initiative at this difficult time. Among them were well-known community figures, such as Attorney Leib Garfunkel, Rabbi Shmuel-Abba Snieg, Attorney Jacob Goldberg and others, who during the Soviet rule were declared 'enemies of the people' and were jailed or confined to their houses.

After the move to the Ghetto, the Committee was merged into the Aeltestnrat – Council of Elders – the organization that with the assistance of the bureaucratic apparatus and the Jewish Ghetto police ran the internal life there.

Among the masses that assembled in the courtyard to seek help in getting a place to live in the Ghetto or to get a dear one freed from the 7th Fort, if they were still alive, and other similar requests, I overheard a women from the poorer class say, “Why did we speak against the rich when the Soviets ruled? After all, when they had money and food, so did we! Now, when they took everything away from them, what will be with us?”

Close to the sealing of the Ghetto in August 1941, I heard an influential man say to his wife, “I would really like to get a sack of flour for my house.” When we were confined to the Ghetto and the great starvation set in, I remembered that conversation and understood how vital it was. However, I also knew that it was not the most important thing: I learned that that man did manage to get what he wanted at that time, but he with his family was taken to the 9th Fort, the central location for the murder of the Jews of Kovno.

In the framework of the systematic and massive executions that were known as “Aktziyes” and began to be carried out from the beginning of setting up of the Ghetto, on October 6 1941, most of the Jews who lived in this area were murdered. The Jews called this event the “'Aktziye' of the Small Ghetto.” Only very few, including my family, succeeded in surviving to move to the main Ghetto.

As one who was blessed with the qualities of curiosity and a relatively good memory, I would frequently wander in the

[Page 6]

streets and alleyways of the Ghetto and soak up with my eyes impressions of the depressing reality into which it seemed that I was unintentionally dropped. Some of the impressions that my eyes saw and that my ears absorbed, I recorded in my mind and also in a special notebook. Thus, I was very impressed by the fact that a very large number of the Jews, including those that were not so scrupulous in their observance, participated in the prayers of the High Holidays. In Hebrew, they are known as Yamim Noraim, usually translated as Days of Awe, but the word Norah can also mean dreadful or terrible. Accordingly, there was a double meaning to the words, Yamim Noraim – Days of Dread, especially in the beginning when the Ghetto was set up. Prayer services (minyanim) were held in private houses, which were in any case, extremely crowded, since several families had to live together in a single apartment. I will never forget the cries and supplications that broke through during the services. I will especially remember Ne'ilah prayer on Yom Kippur; the voluntary cantor was an elderly Jew by the name of Leib Feler (his oldest son, Dr. Noah Feler later served as head of the Sharon Hospital in Petah Tikvah). When he got to the phrase, “Our Father our King, annul the evil decree,” he repeated the word 'annul' many times as his voice chocked with tears and the entire congregation moaned in tears after him. On one of the days of the holidays, in all the prayer houses where services were conducted there was a quick visit by two community leaders, one of them, the former Judge Vulf Lurie who was eventually one of the most powerful and unpopular people in the Ghetto, who came to convince the worshippers to leave immediately for forced labor. The Germans issued the Ghetto an ultimatum to immediately supply several thousand workers to construct a military airfield in Kovno …

It is no wonder that during this period of rampant bloodletting taking place almost non-stop in the Ghetto during the fall of 1941, none of us knew what was in store for us even in the hours immediately ahead. I was reminded of the verse in the Torah, [Deuteronomy 28:67] “In the morning you will say, 'If only it were evening!' and in the evening you will say, 'If only it were morning!' – because of what your heart shall dread and your eyes shall see.” At that time, when the order was issued that all jewelry and money had to be turned in, I was sure that all the Jews would do it without hesitation so as not to further endanger their lives. However, after my wealthy uncle Moshe Levin was taken to the Ninth Fort at the time of the Aktzia in the small Ghetto, I gathered my courage and went to his deserted house and took some Hebrew books to read, including some volumes of the annual publication Hatekufah [The Era] printed by the famous Shtibel publishers. While reading them, I found some pages that were stuck together, and between these pages there was money hidden. In retrospect, this money helped us endure the great famine that raged in the Ghetto especially in the brutal winter of 1941. During that time, we even ate the boiled skins of potatoes calling this dish “Cholent.”* Because of my age, I was not required to [report for forced] labor, but in exchange for a loaf of bread, I agreed to be a Mal'akh, an

[Page 7]

“angel.” That was the term was used to describe the young men who for a loaf of bread or some other similar payment went out to work in place of the older men. I worked in various and sundry places of forced labor, including the airfield, the Flugplatz as the Jews also called it. This was a large place and the most difficult one to work at. Between beatings and sadistic abuse thousands of Jews and Soviet prisoners of war worked from early in the morning until late at night under the open sky in all kinds of weather. During the day, they were given a piece of bread and some watery soup. In addition to all of this, the workers were forced to march for four hours to and from their place of work.

The day before “The Great Aktziye” that took place on 28 October 1941, the date the largest number of Jews was murdered in one day throughout the Holocaust in Lithuania, we were kept at forced labor for twenty-four hours! When I finally returned home before dawn, I still had time to join my parents and sister who were hurrying along with all the Jews of the Ghetto to report to “Democratu Square.” Even though I was exhausted, certain episodes from the Square are engraved in my memory – for example: the hysterical screaming of family members searching for one another; someone waving an umbrella in the air, in order to signal to someone looking for them, and more. Suddenly, an old man passed us by – it was my grandfather, Reb Dovid Levin, who on the advice of friends shaved his beard in the style of Franz Joseph, in order to look younger than he was. This was the first time in my life I saw him like that, it was almost as though he were naked! This was our last meeting, as on that day, he along with 10,000 Jews “unfit for labor” were detained in the “small Ghetto” and on the following day were taken to the 9th Fort where they were murdered. We were told about it the next day, although quite a few people refused to believe it, including my father. In spite of our precarious situation, for many days my father refused to wear my grandfather's clothing.

|

|

|||

| My grandfather Rabbi Dovid Levin |

My paternal grandmother, Bassia Levin ne'e Rabinowitz |

My Thoughts on the Jewish Establishment, the Ghetto Police, Forced Labor and the General State of Morale A short time after the “Great Aktziye” I was lucky to be apprenticed to the well-known furniture carpenter Mr. Landman. Unlike the airfield, where we worked nearly twelve hours outside in all kinds of weather, I worked for him eight hours in a heated room. I was also able to learn a useful trade in the Ghetto with him.

|

|

|

to do forced labor in the Ghetto |

However, after January 1942 when I was 17 years old, I was obligated just like the older men to report for forced labor and was no longer able to be an 'angel.' Yet, nobody fooled themselves into believing that there would no longer be any executions, but this interim period enabled me to explore my surroundings out of curiosity. So, for example, I looked at the condition of people's cheeks, whether they were full or sunken. Thus, I was able to tell who was suffering from

[Page 8]

starvation. I noticed that the Jewish police and most of the other functionaries looked satiated and even well fed.

I identified fully with the folk songs that sprouted in the Ghetto, like Nit Ayer Mazel – 'No Such Luck,' that expressed strong criticism against the Ya'alehs, the nickname for the 'Big Shots' in the Ghetto. The disapproval against the Ya'alehs focused on their inflated behavior and that they forgot that their high status in contrast to that of the 'regular people' in the Ghetto, was granted to them to a certain extent with the blessing of the homicidal German governor, whose interest they were actually serving. Owing to my careful observation, I noticed that the women were more conscious of their outward appearance even when doing forced labor outside the Ghetto. I remember that even during these difficult days there were people among us who made an effort to go out in the Ghetto streets wearing clean clothing and who greeted those that they knew by tipping their hats, just like free people and not prisoners. This was to prove to ourselves that we still had some measure of control over our own lives. Thus, it was common, even during the most difficult days of terrible hunger, to eat food with a fork and knife, to continue to brush ones teeth and so forth. Likewise, there were some in the Ghetto who tried to wear their Yellow Star of David, which we were required to sew on our chest and back, in an esthetic manner.

Like all the men, I, too, was required to remove my hat in front of the officials at the Ghetto gate when I returned from forced labor. I tried to do this with my head held high. I recall that I would jealously look at the stray cat who could cross the Ghetto barrier without interference. Besides the frustration of being locked behind barbed wire and especially the fear of not knowing what the next day would bring, the torment of constant hunger continued to afflict us. Under the best of circumstances, two or three times a day we ate a watery soup called Yushnik, which was the kind of thing fed to animals. Bread was a rare commodity. Once, my parents sent me to the food distribution station to bring our weekly bread ration, one and a half loaves, home to my family. On the way back, without even noticing it, I inadvertently started to nibble on the half-loaf and then the whole loaf. When I got home, there was absolutely nothing left and to this day, I am still ashamed of it! In addition to the misery of hunger, I felt suffocated living behind barbed wire walls faced by the open rifle muzzles of the erect Lithuanian guards surrounding the wall. Not infrequently, I was haunted by the question, “Is there nobody in the world that knows about us?” I talked about this a great deal. And when I would ask, “What will happen,” the answer would be, “Everything will be fine – for the Jews in America …”

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

With a Rifle in My Hand and Eretz Yisrael in My Heart, Dov Levin

With a Rifle in My Hand and Eretz Yisrael in My Heart, Dov Levin

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 27 Aug 2005 by LA