[Page 115]

Vatsevitsh (Iwacevicze)[a]

Jewish Forced Labor Under the German Occupation in the First World War

(Ivatsevichy, Belarus)

52°43' 25°20'

Y.L. Abramovitsh

Translated by Gloria Berkenstat Freund

A.

I know: now, after what the nation, may its name be erased, did to our people; now after the era of ghettos, concentration camps, gas chambers, crematoria, Jewish soap, and so on; after applying such methods of torture that only the “inventive” sick mind of the super–cannibals and scoundrels could have devised – now, taking records, crumbs of memories from years ago and describe that which the same Amalek [Hitler] – who even then wanted to be and ostensibly was supposed to be considered the main carrier of civilization – did with the civilian population in general and the Jews in particular in its occupied areas. Now to remember this is perhaps a travesty if not a desecration.

However, then, 40 years ago, times were a little different. The person still had a value. We still spoke then – and many truly and naïvely believed – about civilization, culture, progress and the like. We still believed in the human mission of bringing a more beautiful and better world. In short: “The 20th century!” Seemingly a trifle!

And the Germans went to all lengths to show the world and to parade themselves as the carrier of the flag for all of this. For many of us Jews, he ostensibly was supposed to be the “liberator”: he would free us from Nikolai whose administration then carried out the

[Page 116]

let–us–deal–wisely doctrine of narrowing and choking the Jews with edict after edict every day, both in the economic and cultural areas.

I still remember well how, for many Byten Jews, Kaiser Wilheim II was then truly the Moshiakh [redeemer]. Ironically, they called him “Reb Welwele.” “Reb Welwele” was then the pseudonym for Germany. “'Reb Welwele” is already in Grodno.” “He is standing outside of Brisk.” And so on. They heard his footsteps, counted the hours until his arrival in Byten. It is certain that it was not out of love. “Reb Welwele,” like the hated Nikolai, who had mainly since [Prime Minister Pyotr] Stolypin's regime had increasingly choked the Jews.

The accursed nation's greatest Hasid [in this case, follower] at that time in Byten was Shimeon the shteper [cutter and stitcher of shoe leather] – Bushulovitz, the brother of the famous artist with the Vilna Troupe, Noakh Nachbush. He was a fervid Zionist with a strong, warm Jewish heart. Despite his external, ostensible thoroughness and despite his inclination “to reprimand” very often, he truly was good natured, had a golden heart and he was always ready to do a favor and in secret if he could.

In his great enmity to Nikolai for persecuting and oppressing Jews, Shimeon saw a defeat for him. And the closer that Germany came to causing this defeat every day, his “love” for “Reb Welwele” became even stronger.

That summer, 1915, when it already was clear that Nikolai was doomed and that his downfall would come quickly, Shimeon the shteper became a very “different” man. His usual gloom disappeared. He became cheerful, with a particular liveliness in his eyes.

And the closer the Germans, the better was Shimeon's mood. He could not sit still in his house during the last weeks; he neglected the work in his workshop. He was seen much oftener in the street. Here at a small bridge, there near the other porch and there with a small circle [of people] around him. The main theme was “Nikolai's downfall.” “The Germans will be here very soon.”

A mood as if for a holiday excited him then. He looked like a Hasid who awaited his rebbe, like a groom who awaited his bride. He was something like the wedding in–laws. He would often rub one of his hands in the other from great, overpowering joy. I see him now before me as if he were alive. “Yitzhak–Leib,” he once said to me. “We will yet have a little whiskey!” A second time, he said to me:

[Page 117]

“Watch, we will soon make the Shekheyonu [blessing said on major holidays and to celebrate a joyous occasion]!” And another time: “A little leap forward!” May the Prussians live! Health to their little bones!”

Many Jews felt about the same way then. They believed in the Germans, waited for a bit of salvation from them. In some sort of change for the better – they were sure of this.

Then, 40 years ago, there still was another world. As well as a still disguised German. The disappointment was great when we began to feel the true German against us, the pain, the insults – difficult. They still remember it very well. I think something of this, how the Germans treated we Byten Jews during the First World War, must be recorded for history. History does not know of sentiments; history relies only on facts.

B.

There were stars in the sky when we left the house on that very frosty morning in the middle of winter, 1916.

We had been living in the very close village of Zarech'ye, in an abandoned peasant hut, where we had gone after the burning of our house during the retreat of the Czarist army in 1915.

And as we slowly managed to get to the headquarters, the morning star began to disappear and day began to break. The frost kept increasing.

At the headquarters, we met several people who had come a little earlier then we. With every minute still others arrived with their packs on their backs. The majority accompanied fathers, mothers. They began to exchange remarks. It was a little comfortable.

The so–called “civilian workers” were going to Vatsevitsh to work that morning. Twenty–five men and about the same number of women.

We were supposed to go only for a few weeks of work in a marmalade factory. We would make marmalade out of the large, sweet, “horsey” beets. We would eat and drink well, we would have a good place to live and then come home.

In short, it would be a pleasure. Thus, argued the Jewish militiamen who had announced days earlier who would have to go. The commissioner, who had to provide the workers, also kept assuring us. The Germans probably had said this to the commissioner.

However, we, those chosen by the headquarters, had a

[Page 118]

heavy heart. We were uneasy about the vagueness of our fate, and our fathers and our mothers were even uneasier.

We did not believe too much the “stories” that were told us. It was something “too good!” From our own experiences with how the Germans treated us here and at home, when we were driven daily to various work, we knew and sensed on our own backs and bodies what they considered “civilian work.” And if at home we had been beaten at work and we had been given various heavy, insulting punishments for trivialities and, at times, for nothing, only by virtue of ill treatment, well, what could await us far from home?!

And even worse, gnawing deep in our hearts: in general, were we being sent to Vatsevitsh? Perhaps, somewhere else, far, far away from home. Who knew where, for what, for how long?

We had a basis for all of these doubts. Rumors that young men would be taken from the shtetl to forced labor somewhere in Germany began to spread again at the beginning of winter. The rumors were denied; they died away. And immediately again and with more strength, they were revived. This is how it was for several weeks. The impact of this in the shtetl was unimaginable. The desperation of the parents who had children who were potential candidates was very great.

It became quiet after this. Personally, I do not believe that the intervention by Rabbi Ziv helped then. I am inclined to believe that the headquarters itself interceded with the higher authorities and prevailed. It was in the interest of the local headquarters to not let go of “hands [workers].” It alone conducted intensive work every season of the year in fields and forests, with making hay, digging trenches and with dozens of other jobs and could always make use of workers.

Information had long ago reached us from Slonim that Jews were being caught there and sent away to eastern Prussia, to a camp somewhere. The conditions there were so terrible, so unbelievable then that it threw a deadly fear on young people. They fell like flies there from torture. [As well as from] grave epidemic illnesses. Typhus and dysentery chiefly raged and took their victims. Several returnees, escapees or those sent back after serious illnesses, who looked like skeletons, told [of this].

Well, who knew if saying that we were going to Vatsevitsh was not a seduction, a deception?

The pity was on the parents. We were mostly still very young. A number, under 20 years old. And here the children were being torn away. They were being taken away, and God knows what, how, when and where?!

[Page 119]

Right on time, seven o'clock, the subordinate officer, Bobersky, and several of his aides appeared. This Bobersky belonged to office headquarters of the district commander and was the supervisor over the aides and the sending of the forced laborers daily. He would give the order to the several Jewish militiamen to provide him with the number of workers every day and where they needed to go.

After calling out our names and after counting [us], we were surrounded immediately by soldiers. We barely were able to say goodbye to our closest [relatives]. We lay our bundles in the “wicker” sleighs and began to move; we went with our sleighs, hurriedly gave our last words with our [family], consoling them that it would not be for long, and not far away. We would be back quickly. They accompanied us, keeping their distance a little. It was difficult for me to look at my father. His eyes caressed, warmed, but I saw well in them and on his face the suffering, the pain and the worry at our separation.

So we left the shtetl, passed the steam mill – the last house – and we found ourselves on the border with the village, Zaretshe. The sleighs stopped suddenly. A bit of excitement. Two feld gendarme [field gendarmes – German military police], in their green uniforms, ran. Absorbed only in themselves. I did not notice with the one closest that these were our two very “eminent” accompaniers, feld gendarme. They now asked us to sit on the sleighs. We had to “go to Iwacevicze more quickly,” they said.

We arrived in Iwacevicze at about one in the afternoon, right near the Moscow–Brisk train line. And very near the highway with the same name, between the Damanava and Lukashevo (Kossovo) stations. The Germans had built a military base, ammunition depot, warehouses of provisions, coal, oil, iron reserves and other necessary military resources. There, they also erected a “vegetable” factory and “our” marmalade factory, where we were supposed to work.

Earlier it had been quiet in the area: fields, forests. The familiar White Russian landscape, with its sad peacefulness, longing calm. The train would then speed by without stopping. And several times a day explode the dreamy monotony. Who had heard the names Vatsevitsh or Iwacevicze, as it was officially called, before? I, in any case, had not.

Now, there was excitement in the square. Feverish activity, movement and work. The Germans had built a train station here. Gave it the name Iwacevicze, after the nearby village, Vatsevitsh, that lay at the approach to the famous Pinsk swamps. We were brought here.

[Page 120]

|

|

The Byten Men – Group of Forced Laborers in Vatsevitsh

From right to left: Dovid Bresking, a Christian [name unknown], Sholem the bookbinder, Dovid Yosha's son, Ben–Tzion Afroimsky, Krasha's son Yankl Alter,

Ayzyk's son Kalman–Moshe, Moshe–Yitzhak Davidovsky, Zelik Yankl Novisaders, Ahron Veiner [Chatskl's son], Yitzhak–Leib Abramovitsh, Moshe [Gedelia's son] Yudkovski,

Vengovsky [Shmargai], Meir Glazer, unknown, Yakob Galinsky [Necha's son], Yisroel Fleshkier, “Filipka,” a Christian, worked with Mates Hilkes |

[Page 121]

We already had been standing outside in the burning frost for over an hour. It was a bit of luck that there was no wind and the sun provided a little warmth. The soldiers guarded us. However, our two main accompaniers were not here. The two feld gendarme immediately vanished somewhere and we were waiting for them. Probably, they had gone to eat. The devil knew. Perhaps they were “resting” at the local commandant, into whose authority they had to give us?

There was a bit of a disturbance; the women were being led away. To where?! And would they bring us to the same place?!

We received new bosses at three o'clock, soldiers with uncovered bayonets. They acted with severity toward us, as if we were who–knows–what kind of criminals. Placed in rows in two, we were told to march. We dared not take a step out of the row. Suddenly, a patrol appeared and threatened us with the butts of their rifles. At first, we did not understand this behavior toward us. The thought went through our head: worse than as prisoners of war. However, we pushed on quickly. They were guarding us in this way so that we would not escape.

After going a few viorst [a viorst is a little more than a kilometer], we were led to a small settlement. This was Vatsevitsh. It already was dark outside. [There were] very few village houses, here and there a hut. The village probably also disappeared with the fire. However, we noticed something like a piece of roof, projecting a little over the level ground. So much, so much barbed wire fencing. What could this be?!

We waited again, standing in the burning frost. The sun had set. We remembered that we were hungry. Groups of Russian prisoners of war under the watch of patrols appeared. They disappeared in one of the wire–surrounded holes. They had returned from work. Going by they looked at us with curiosity, surprise and, I thought, condolences and also compassion.

We were driven into one of the barracks along with the prisoners of war. It was clear to me what was to be with us. So here you have “Vatsevitsh.”

C.

Seventy meters long, eight meters wide and three meters high, more accurately, deep. It was dug in the earth. The dirt walls lined with beams. A roof from above, slightly sloping and elevated for half a meter above the level ground. An entrance in the middle, through which one went down steps. The door was always open, except during heavy snow storms and winds.

[Page 122]

Under the roof, in a few wall beams that were above the ground, were chiseled out holes of three quarters of a meter in several places. These were the “windows.”

The plank beds, lower and upper, extended along inside a little distance away from the walls. Only in the middle, just opposite the entrance, the plank beds were moved away one from another and formed a small passageway from the door to the wall opposite and simultaneously as if they would have divided the barracks into two half kingdoms.

A cast–iron field oven stood near the wall opposite the door. Ostensibly, this was supposed to warm the entire barracks. There always was pushing around the oven; we wanted to warm our hands and feet a little, dry the wet leggings. Sometimes, someone tried to bake a little bit of frozen turnip or a carrot that by a miracle he had received somewhere at work. Whoever was stronger, more arrogant, grabbed a spot. The tin tubes that were supposed to serve as a chimney provided us with an abundance of smoke and soot.

Above, in the middle of the same “corridor passage,” a small hanging lamp gave off smoke. This little fire always shook and bounced, throwing dancing shadows around it and caused vertigo. This was the only lighting inside.

Underneath, there was no sign of anything that could serve as a floor. Naked, wet, dirty ground. There was always mud near the entrance. The snow that those entering brought in mixed with the dirt even before it could melt. There always was a stir of mixed noise and talk in the air. The air itself was always thick, unfresh. I would say in our Byten language: “to cut with an axe.”

The plank beds were made of sticks, with spaces and here and there sharp knots. Once, originally, it appears that a little straw, husks was spread on the sticks, but when we came, there was no memory of this left, only a little bit of shredded, ground garbage.

This was our quarters. The barrack – first for Russian prisoners of war – was already overflowing with men. In the evening, when they began to drive us there, they asked the prisoners to make “space” in the plank beds in several places. Several Byteners and I, I no longer remember who, received an upper plank bed not far from the small oven. We lay down our packs at our heads. The crowdedness was frightening. The first night there – as before my eyes now – we had to lie on our sides, pressed like herring one against another. There was no space to lie straight. That day we were especially tired.

[Page 123]

We were young. We fell asleep immediately as if murdered. We did not feel the hard sticks under us. We were awakened several times through the night. [Things] crawled on our bodies, bit. We felt something – like worms, insects. Exhaustion and sleep soon overpowered me. I shook a few times and immediately fell back asleep. Once, I remember, more asleep than awake, I moved my hand on my body under my shirt, grabbed a handful and threw it somewhere, into the void. I did this unconsciously, instinctively, protecting myself. I did not know what it was. It did not occur to me that the bed could be so wormy.

They did not let us rest, sleep. Finally, my mind cleared a little. What was this … an affliction?! That night I put on a clean, new shirt. The last day before my departure, my mother had sewn several shirts for me out of the only piece of linen that remained in the entire pit of goods in our garden, which the Germans had opened and emptied. This we did a day or two before the retreat of the last Russian soldiers and before the burning of the shtetl, hastily digging a pit behind the house and hiding some goods there. Many Byteners then did the same thing. We were so naïve then. We even dug trenches in the gardens – large, deep pits, covered with boards on top – spread with a little sand. There was a hole on one side for an entrance. This was to serve the family as protection against the cannon fire from both sides. How childishly backwards we were then.

I put on a fresh, new shirt. I fell asleep. However, not for long. The same thing repeated itself. I could no longer fight a war with the attacking worms. My neighbors on both sides were moving all the time, muttering in their sleep, a curse. I envied them.

It was a salvation for me in the morning when the lance corporal ran in and “sang out” his “Everyone get up.”

D.

The lance corporal ran in at five in the morning. While still on the steps, he shouted: “Everyone get up!” Once and a second time. Instantly, we were up and in a minute or two down from the plank beds. The lance corporal's cane instantly began to “stroll” over whomever did not get up fast enough.

Coming down off the plank beds, one washed his face and hands with a little snow. We hurried to stand in the row for a little coffee. After this, we quickly

[Page 124]

stood again in a row [to be counted] and we went to work. An unlucky one, that is, one who was not agile enough, would miss his meal.

The large tubs of human excrement gathered for a day were taken out somewhere. The soldiers would grab the first one who came along whom he happened upon and honor him with the [task]. Because of this little work, one often missed the coffee, too.

A patrol would lead us to and from work. The same soldier would often also need to watch our work throughout the day. It was very difficult work: emptying and loading wagons with various kinds of ammunition, train rails and other iron, cement, sacks of various products, clearing away the snow, forest work and so on.

On the first day, I was led with another one to a freight wagon full to the edges with coal. We were given only two hours to empty it. No matter how hard the soldier drove us and all the while jumped at us with clenched fists, with a rifle at his left side and no matter how hard we worked, we could not empty the wagon is such a short time. Even the blows could not help in the end.

Most of the soldiers under whose supervision we would be were sort of “out of sorts.” Before, almost all had been on the active front once or more. They were sent away from the front only because they were no longer suitable for the front ranks; one was a bit of an invalid, one had been gassed, one was already ill and a large number were half idiots, fools, dazed with fear and by heavy bombardments on the front. Many of them suffered from a sort of inferiority complex.

Being our boss for the day, knowing how disorderly we were, such types began to show their “greatness,” their “strength.” It compensated them for their dejection and feeling of inferiority. And if such a madman was an anti–Semite, too, there was nothing with which to envy us from that day.

Many times we happened to work with the prisoners of war at various labor. We noticed well the difference in the relationship of the labor foremen to the prisoners of war and to us. They did not dare to drive, to chase the prisoners the way they did to us; [they had] respect mixed with fear for the Russian prisoners of war. At times [they had] a sort collegial attitude to us civilian workers, but it was a relationship from the top down. The

[Page 125]

strictness – great, difficult, an offensive relationship that fell even heavier than all physical persecutions.

The Russian prisoner was a little freer in his movement. However, we were not let alone for even a step. And if someone innocently – for a person's needs – began to leave his workplace, without receiving

|

|

| Iwaceviczer Men's Group at Work |

earlier permission, he received heavy blows. One case occurred that one of us, on the day of our arrival, did not hear the shouting of the patrol well enough to turn around; the disturbed soldier started to aim [his gun]. He would have [shot] if our voices had not turned around our comrade.

The patrol would bring us back to the barracks after a day of heavy labor. We received a little soup and we remained hungry. During the day at work, we would be given half an hour, I think, to eat and rest. However, not everyone had something to eat. Not everyone had an extra piece of bread to bring with him. Not all of us received, whenever there was an opportunity, a little bread for the week. The opportunity would be when an acquaintance had a horse and he would be asked by the Byten

[Page 126]

headquarters to carry something somewhere. In the slang jargon of that time, it was called “driving on Zhuravlikha.” We would receive a package of food, a greeting and even a piece of a letter, too, from such [a person]. Through such a person our parents would send us a greeting of several words.

Several of our group already had to survive on the German food alone during the first week. They began to suffer from hunger during their first days in Vatsevitsh. I divided my [food] with one of those during the first weeks. Later, the Zhuravlikha horse did not come to Vatsevitsh so often and not all would regularly have something sent. In our homes, it appeared, the little bit of rye that had been kept was used up. There was no place to buy anything even if one had the means to buy.

That winter of 1916 was extraordinarily cold and difficult. The older men would say, “We do not remember having such a winter in such a long time.” Great snowstorms occurred very often. Extraordinary frost did not end. Our work was outside. And it had an even greater effect on us.

The worst weather did not keep the Germans from driving us to work, even in blizzards – dogs to chase. It often happened that immediately after coming back from work and after grabbing the little bit of miserable soup, when we still had not recovered from the day's work in such weather, there would suddenly be a commotion: “Quickly, [line up]!”

Night. The famous Russian blizzard acted up even more, ran wild. And after a difficult day of work, we again were driven out.

We were needed somewhere on the train line, or at another point, to clear away the mountains of snow. We had to do this. And it also happened that after returning from such an expedition, one or two o'clock in the middle of the night, not being able to stand on our feet, we suddenly were awakened at five in the morning and driven to a day of work, as usual, as if nothing had happened.

There could not be too much good health. First – chills. One morning, Yisroel, the son of Zalman the wagon driver, could not raise his head because of a lead weight in his limbs and a considerable fever. The German who was in charge that day of such cases was more or less scrupulous and he let him stay in the barracks. Yisroel was not better by the evening and the next day, very early, he was burning like a fire. Finally we were successful in bringing a “doctor” – a field medic. He was supposed to give the first help.

“Oh, it is nothing,” said the “Professor,” – “He does not yet have a temperature of 42 [107.6 F.], only a meager 41 [105.8 F.].” He did not call a doctor for Yisroel, did not say that he be taken to a field hospital. He gave

[Page 127]

him some sort of capsule and let Yisroel lay in an open, cold and windy barracks. It made no difference if Yisroel did not have a temperature of 42, but only about 41. Returning from work at night, we did not find Yisroel in his bed. During the day they must have taken him from the barracks and brought him to a field hospital.

E.

We had not seen our sisters in sorrow since our separation on the first day. We heard, knew that they were in the same

|

|

| Women's Group in Iwacevicze Forced [Labor] Camp |

village, not far from us. However, here we were like arrestees behind wire, surrounded by guards.

I think during the fourth week after work, after eating, everyone rested in his own way. A German ran in and called out several of our names. He was in a good mood: “Di madchen [the girls]!” That is, the girls miss you! (Those whose names were called out.)

It was really simple. They [the girls] wanted to see their own people, talk. The relationship [of the Germans] with them was better than their relationship to us. Earlier, they also had been held. They convinced [the Germans], that is, some of them had asked to be with their relatives and friends for a while.

I no longer remember who were then the lucky ones. The second time my stars were very good to me. I do not know who called me out and I actually did not

[Page 128]

expect it. How much I then knew, I had no idea of someone who would be my relative there, or such a close acquaintance. I thought perhaps this one, the other one, but [could not guess]. However, I still remember well the surprise, when arriving there, I learned who had “required” me. I never would have thought of the name. It turned out that when one is young, one is really young and it also turns out one can never know what is going on in the heart of a girl of such an age.

The girls lived a bit like people in comparison to us. They were located in a house, above the ground and not like us, in the

|

|

| Byten Jewish and Christian Girls on a Holiday in a Forced Labor Camp |

ground. It was a small hut, also with upper and lower plank beds, the narrowness – terrible. When we entered there, we felt a wave of heat. At first, we were delighted with such warmth. However, it immediately became too hot for us. We already were not accustomed to this.

The field oven stood half a meter [about one and three quarter feet] from the wall, but it was a large one. It stood on a brick foundation, slightly built in. It burned well inside. We could not stand close to it. A good, tin chimney reached to the nearest wall and the chimney went outside through a hole hacked into the wall, not far from the straw thatched roof. I noticed that the wall near the oven was very warm and was sweating. The smoothly cut pine wallboards had large drops of tar on them. Several places were flooded with dripping resin.

Our visit ended. How quickly a quarter of an hour passed. Our little German called us back. We had to go.

A few weeks later, the “palace” disappeared in a fire.

[Page 129]

It happened in the middle of the night. The fire spread very fast on the outside and the inside. The German patrol noticed the fire in time and sounded the alarm. The fire quickly cut off the exits. Several women were nearly asphyxiated [and] barely crawled out through the windows. Without the quick, rapid help, there would have been many victims. Some sort of miracle occurred.

It is not known exactly how in the middle of the night, while people were in deep sleep, the inside wall [caught fire] and the thatched straw outside immediately began to burn.

F.

That winter there was hunger in many homes in Byten. They managed with the portion distributed by the Germans through the committee. There was no bread to buy anywhere. At the retreat of the czarist army, the Christian city and village population was evacuated deeper into Russia by the military regime. No food shops remained. Buying rye, flour and the like was impossible, even if there had been money. Byten was cut off from the world. No one was allowed in or out. Patrols stood at the most important points at the end of the city and kept watch day and night. To leave, one had to have a special pass from the headquarters. However, they were not provided. The well–known “green jackets” – the field gendarmes – always hung around all of the roads and certainly no one wished to meet them face to face.

Not everyone could prepare a little wheat from the abandoned peasants barns. Not everyone had the necessary physical strength and opportunities and also not the human resources to run, drag, carry, dig and search and so on.

This segment of the population could not even provide enough potatoes for a year. And in the autumn of 1915, there were hundreds of thousands of poods[2] of potatoes. One only had to go out into the fields and dig for them. However, not everyone had someone to do this. And if they dug out some potatoes, how much could old people, weak women, small children gather on their backs [to take] home?!

There were several in this category, both among the men and among the women, in our groups exiled to Vatsevitsh. They began to be hungry on the first day. They did not say anything. However their eyes spoke.

In later weeks, contact with Byten was much rarer. The Zhuravlikha wagons did not come as often and regularly. Now many began to suffer from hunger.

[Page 130]

And so crawled the days, the weeks at that time. We ran out of the barracks at five in the morning and stood in a row for a little bit of coffee. We then immediately had to stand for kontrole [to be counted] and we were forced at once under guard to work in groups. At night we were again driven to stand in rows for a little bit of soup. A few hours later would come the order to go to sleep.

Thus, day in and day out. Monotonous routine. Not enough to eat, not enough rest anytime as usual. From barracks to barracks, like wild animals in a cage. There was not the least bit of freedom to move alone. Home became even more distant like a beautiful dream.

A large number of our people were attacked by despair. Returning home?! So quickly – certainly not. Others became lifeless, bedraggled, indifferent. For those it was a terrible situation. Encouraging them by some of us helped little. They would move their hands, hopelessly.

After Purim. It was very cold, frost, snow. [It had been] a long winter. However, the days already were longer. The sun's warmth was stronger. We felt that the air was changing; how, was not clear. However, the outside called, laughed, drew. The nights were lighter.

On such a day, coming from work, I, after miserable food, quickly slipped out of the barracks to a bit of the small courtyard in front that was surrounded by a high barbered wire. Sometimes others also came out to stand at the fence to look at the open, free world behind the wire. The gnawing in my heart grew stronger, the longing for home – more painful. “Why was I imprisoned like an animal?! I am still a free man!” I clenched my fists instinctively, instinctively bit my lips. A curse quietly filtered through: “A dark year on them!”

I felt that I was losing my composure these last days. For the entire time, I was among the very few optimists. I cheered up the despairing, said and kept arguing that we would return home quickly. They cannot hold us always. We are not prisoners of war, but civilians and certainly not criminals. We must not cease to demand our due. Not suffer. The families and the committee in Byten must do this, and even we here must try. We cannot lose anything. We have nothing to lose. They should send us home as they at first promised us so many times.

I began to feel that I was losing my self–assurance little by little. Some sort of anxiety drove me, did not let me bear it. Could the “something in the

[Page 131]

changing air,” the first portent of the closely approaching spring, be the cause?!

Is youth – the days, the weeks, suffocated in cramped, dirty, infected barracks – the cause?!

G.

On such an afternoon, I think a Friday evening very close to Passover, standing in the small courtyard near the fence, we had a strange encounter. A very pleasant encounter. A strong surprise that also left a bit of a wound in the heart.

|

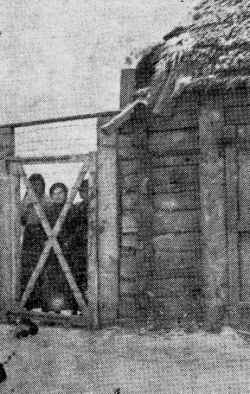

|

| The entrance to the women's barrack of the forced labor camp in Iwacevicze |

A young woman approached the fence on the free side. Immediately a second Jewish woman, not from Byten.

Seeing a woman here in the camp, except for those from Byten, of whom we knew, but whom we seldom saw during the entire time – was like a magical feat had fallen down from the sky. We spoke with them.

There were several dozen Jewish women, widely scattered in various places in the camp. There were Jewish women in other places around Vatsevitsh. They were all from Pinsk. Hunger was great in Pinsk, particularly among the poor Jews. For a long time the Jews had been asking, demanding work from the local headquarters. Finally, an answer once came from the headquarters that they could provide work for several hundred Jewish women. However, not in the city, but by sending them to various places, not far away. They needed young women.

At first, they did not want to hear about this: “Exiling Jewish girls from their home? No!”

[Page 132]

However, there was more torment from hunger in the homes. There was no alternative. Five hundred Jewish women were told to come to a certain collection point; they were forced into freight wagons and spread far from home in various places, among the German soldiers.

The Pinsk Jewish women – in addition to our Byten [women] – were the only women who those Germans encountered nearby. Several girls managed to become house–supervisors over the residences of the German officers. Many Jewish girls in this or some other way left the path of righteousness, the two Pinsk Jewish women, who stood near us on the other side of the barbed wire, added with open pain and tears in their eyes.

They, the Jewish girls, had heard several weeks ago that Jewish civilian workers had come to these barracks. They, the girls, were not held behind wire. They also could move about more freely. They had wanted to meet us for a long time, but for various reasons, mainly because of the great cold and short days, they had not succeeded.

We could see immediately that the two Jewish women came from middle class families, that they were polite and genteel children with a certain influence of education and culture. They came two or three times. There was not too much talking. It was difficult to carry on a conversation. I think that the two intelligent Jewish girls also had begun to lose their composure, which with all of their strength they had tried to maintain until now. Their longing for home was even stronger, I thought.

For several days, rumors went around that we were going to be allowed to go home for Passover; that we would be freed entirely. The foggy information actually came from home. Our families, the committee had, it appeared, made strong efforts with the commandant. The German gave hope. Our mood was elevated.

H.

A beautiful evening, close to Passover. They arrived with song. A joyful, lively melody. It was a sort of marching melody. When they entered the small barracks courtyard, we began to catch individual words: surprisingly they were singing Adon–Olam [Master of the World].

Fifteen sturdy young men (cedars) each of them, with wide shoulders, well fed, not weary like we from Byten for the most part and how hopeful they were.

[Page 133]

These were Jewish young men from nearby Kosava. They had come here for a short time, returning home for Passover.

“The same scene.” – I thought. “Wait a little!”

They looked at us a bit as if down from above. They kept themselves apart during the first days. “Kosava is not Byten!” Byten was considered as an area on the front. Not so Kosava. Byten was isolated, with a difficult approach. Not so Kosava.

They were somewhat freer in Kosava. In many cases they left and returned. Several shops were open. And chiefly – there was enough bread, still more than enough. Kosava had prepared. When the armies had changed, Kosava remained intact, not burned like our shtetele [small town]. Kosava Jews also remained in their places and did not have to escape from the shtetl for several days, like we from Byten. Kosava Jews – except perhaps for some individuals – did not know of all of the troubles, persecutions, hunger and being forced to work as much as those from Byten.

“We will not be held here for long,” they said and repeated. “May it come true!” – I thought.

It only took a few days. Their faces became a little paler, their backs bent. I thought their self–confidence disappeared. They now spoke a little quieter. They moved toward us a little. They began to ask for details.

“Children, I think we are all equal before the German. All forced laborers, slaves. Yes, front area, not front, all are equal: [those from] Byten, Kosava, Rozhinoi, Slonim – there is no difference for him. [We are] the same privileged people. And we are certainly all Jews to him.”

I.

It happened suddenly and unexpectedly. We returned from work and heard that today our Byten women had been sent back home. We found out that it came unexpectedly for them. In the morning, they were told to pack and be ready. Later, under guard by soldiers, they were sent home.

We felt as if we had suddenly been orphaned, forsaken, entirely abandoned.

We had left from home together. Unconsciously, instinctively, we had felt more secure the entire time because we were not far from the others. They, the women, had to be treated a little better than us and while they still were in Vatsevitsh, we would also remain here. We came together and they would not tear apart our group.

[Page 134]

Now we remained alone. We were happy that at least they had been freed. However, we also envied them. We also were afraid of the idea that perhaps we were sentenced to remain here for who knew how long. Perhaps they would send us from here to somewhere else.

The sudden sending home of the girls without us was not a good sign for us.

J.

Even before Purim we received uncertain information from home that we would be freed for Passover. We might even remain at home.

Our parents and the committee with Rabbi Ziv at the head fervently appealed to the commandant. Rabbi Ziv spoke personally to the commandant a few times. The Germans at that time had special esteem and respect for Rabbi Ziv. A man of stately appearance, a tall, distinguished, handsome man in his early 40s, with manners and bearing and the speech of an aristocratic and worldly man, he had mastered perfect German and several other languages. He possessed a high level of general education and was considered a gaon [sage] in the Jewish world, as one of the rising leaders who promised a great deal. He was also called the “Tawriker genius,” after the shtetl [town] from where he came to the yeshiva. Rabbi Ziv took over the Byten rabbinical seat from Rabbi, the gaon, Reb Matisyaha (Mednicki) – a rare type of Jews and rabbi, in general, who in his advanced old age, several years before the First World War, relinquished his rabbinical position, which he occupied for many years and left with the rest of his family for Eretz–Yisroel.

At that time Rabbi Ziv found favor [in the eyes of] the local headquarters. They relied upon him. They promised him to do everything they could. To be truthful, I personally will mention that I had very little faith: once a liar, swindler – always the same. And the Germans fooled us at every step. I did not speak about my doubts so as not to take away the bit of an illusion among my fellow sufferers.

The information of the date of our being sent back came from home a short time before Passover. It is possible that the Byten headquarters had intervened and made strong efforts with the ruling regime about this. However, the women were brought home and we were here. And it already was the last week before Passover. Here, now three days and then two days before the holiday. It already was erev Pesakh [the eve of Passover]. We were still here. We certainly would remain here for Passover.

[Page 135]

The disappointment was too great a blow. Some went around as if confused, their heads literally down, their faces – black. Passover – such a holiday! So close to home – 25 viorsts [about 25 kilometers – about 15.5 miles] entirely – and even on the first day we were not freed.

We wandered around cheerless, quiet, with unhidden sadness in our eyes, with open Jewish grief on our faces. We could find no place for ourselves. We left the barracks for the small courtyard; we immediately went back inside, and [repeated this] constantly.

One Artshik Viner, Khatskl's son, was a little different. Isolated, engrossed in himself. His eyes half downcast as if he only saw a few hands in front of him, not more distant and not a little to the side, like someone half not from here, as if he was occupied with something internal, as if he was preparing for something. He avoided speaking; he didn't even answer.

This day was the first night of Passover. The first Seder. There was the same din in the barracks as always. My several Bytener mostly were on the plank beds or standing on the ground; they looked as if “buried.”

I decided to take a “walk” across the barracks itself. “To look” at the world. In reality I was not yet very far from my plank bed. Let me see how my “colleagues,” the Russian captives, lived. My stroll did not last long. The same unease did not permit it. The captives mainly were involved with themselves. One was sewing a button, placing a patch on his pants. One was occupied with scraping frost from a thawed sweet beet or carrot. They had their own lighting – a tallow candle. They had many things that we did not have. They found a solution, that something would show up with them where it had no business being when they were unloading food and other things. It also was the same thing with smoking.

Others of them lay on plank beds, stretched out with their faces up, with a glowing cigarette between their fingers and sang quietly, continuing one song after another, mostly folks songs, sad, longing. Neighbors sang along. They longed for their homes, sown, spread across the immense Russia.

I returned from “seeing the world.” I stood in the small corridor near my plank bed. I did not yet want to crawl up on top. I wanted to know how my Byteners would pass time now. My gaze fell on the opposite side, on the plank bed right opposite mine, above. Artshik, Chatskl's son, sat near his small trunk on which was spread a piece of napkin. A candle burned in the other corner. On the small napkin – a small plate. What was happening there – I could not see. However, erev Pesakh he had received a small package through a special messenger. His parents probably had succeeded

[Page 136]

in sending something for Passover at the last minute. Artshik looked into a thin book. He recited the Haggadah [text used for the Passover Seder]. There was a solemn seriousness on his face. He shook rhythmically. At somewhat of a distance from him was Necha Galinski's son Yakov. He tried to follow. Artshik's voice changed: now, a little but higher, more solemn, the words slower. Immediately, back to the earlier high.

Several Byteners were located nearby, beneath. Just as I, they observed the “Seder.” Others had a mocking smile in the corner of their mouth, barely able to maintain it. I thought – there another fell [under the spell]. Their mockery died out little by little. Faces became serious. Their homey Seder night, those closest to them were now around the table there. Did it strongly move them?!

Dovid Breskin, Khienke's son, moved closer. Now, he already was on the plank bed near Artshik. He began to rock. He repeated the Haggadah.

I also noticed how several prisoners of war, neighbors, moved closer. They watched this with wide open eyes.

Artshik, as if moved, as if transplanted, straightened out a little. His voice began to ring higher. He sang:

“Khasal seder Pesakh k'hilkhato, k'khol mishpato v'khukoto Ka'asher zakhinu l'sadeyr oto, ken nizkeh la'asoto.” [“The Seder has come to its appointed conclusion. As we had the privilege to do it tonight, so we'll have the privilege to do it…”][1]

K.

On both sides of the Moscow–Brisk highway, not far from the new Iwacevicze train station created by the Germans, stood the large village of Jaglewicze abandoned by its owners escaping to Russia. We were there for the [subsequent] days of Passover. Peasant huts were divided among us. Quite good; not the dark, stinking barracks grave. We were in a bit of a human residence. Not several 100 men pressed together, but less than a group of 10. And relatively clean, too. It seems that the earlier residents took care of them. Would the current residents also behave that way?!

[Page 137]

We were much freer here. Almost no barbed wire here; not the accursed Vatsevitsh severity. They did keep an eye on us, but we did not see a special guard at the entrance. We left the huts after work and we could take a short stroll back and forth almost to the highway. We were permitted to do so. A Garden of Eden. Lord of the universe, let us not be disturbed!

The hunger no longer little by little tormented us. We were advised against receiving anything from home. A wagon from Zhuravlikha would not go astray and come here.

We went into the forest to work, near the highway, a few verst [about 1 kilometer or .6 miles] from us. We needed to clean up a certain place of the jumble of trees, beams, branches and wood shavings. The days on the street were beautiful. The snow melted under the rays of the warm sun and caressing winds. Pieces of naked earth appeared. We were not chased as much while working as we had been in Vatsevitsh.

Throughout the day at work we had a cold bath several times, often above the knee. This came unexpectedly. The blinding snow was deceptive here and there; from above it appeared completely solid, innocent, but deep below it water already was gurgling. At work in the forest, we often had to go over such spots and suddenly our feet sank quickly. They broke through the snow and had a bath.

My father did not rest. They freed me, sent me home. It happened so suddenly, completely unexpectedly for me. I was exchanged for another, just as in a story. It then was called a zatsman. A young gentile man from Zapol'ye came and took my place. There was hunger in his house, a large family with small children. They were removed from their village that was at the front and they were driven with other families like them to the empty villages near Byten: Zapol'ye, Mantsiuty, Rudnye and Zarech'ye. Their horse already had fallen; there was no money for another one. Spring already was here. But there was no horse to work the idle field areas.

Someone offered hundreds of rubles to the young gentile's parents. The peasant was eager. The young gentile was very willing; he would have more to eat there than at home. He proposed it to my father and the matter was carried out through the headquarters without whose assent and the necessary proper formalities the entire matter would not have been accomplished.

I knew that my father had very little money left after this and there were small children at home. He, himself, was in very weak health. He had to have a glass of milk that still could be gotten very secretly and for

[Page 138]

a [high] price and as a great “favor” from the two or three Jews who had successfully hidden their cows. What would happen now?”

I was the third one to be freed. Moshka Binies Mendeljevitch had been sent home several weeks before. I do not remember who the second one was.

Epilogue

It was finally deep into summer of the same year that the Byten group was sent home. The Vatsevitsh headquarters had not sent the forced laborers from Byten home out of good, free will, but because they were told to do so from above, by a higher authority. The Vatsevitsh headquarters argued that the village needed the laborers. They had a great deal of work. But the local Byten headquarters had said the same thing and demanded “its people” that it had “lent” for a short amount of time. Place of honor was decided on behalf of Byten with a bit of a compromise. We learned about all of this later.

As noted, the Byten headquarters directed very extensive work, very necessary for the German military machine. A few companies of engineers, technicians and the remaining personnel of the so–called pontoon–boat commandos, who quickly threw a bridge over a river, had been quartered in Byten since the first day of the occupation. The pontoon–boats were pulled by horses at that time, the large Belgian horses. They needed hay for the horses all year. There were large meadow areas of grass around Byten and the Germans would make hundreds of thousands of poods [a Russian measurement of about 16.4 kilograms or 36 pounds] of hay not only for themselves. They also provided hay for a section of the front itself. We did not cut the hay; we could not. But we did all of the other work such as raking, drying, erecting giant haystacks, loading onto wagons, unloading, binding and packing and the like. There really were not enough hands during the hay season and it had to be gathered before the fall rains began.

It was deep into summer of the same year that the Byten group was sent home, but not everyone lived to return. Even several of those returning, some immediately and others later, lost their young lives in one way or another because of the “Vatsevitsh” chapter [of their lives].

Let their names be recorded on this occasion. They also perished at the hands of the “master race” on their way to world rule. Their young lives were cut short only because of being exiled for forced labor by scoundrels. It should be understood that they also were martyred because of the conditions of that time.

[Page 139]

1. Itshe Dawidowski, the son of Welwl–Nisan the carpenter (in the synagogue courtyard).

2. Yisroel Bytenski; Welwl's son Yoshka–Leyzer.

They both were not yet 18. They were tortured by extreme hunger for the entire time. During the middle of the summer, 1916, while working in the forest, they picked a few mushrooms, cooked them immediately in a canned goods tin and they died in terrible suffering a few hours later.

They had done this by mistake, assuming that the poisonous toadstool mushrooms were good, sweet and they poisoned themselves.

3. Yankl Alter Kraszes. He did return, but several weeks later he was no longer among those living. He was 20 years old. His death made a terrible impression in the shtetl at that time. It happened this way:

Immediately after Sukkos [Feast of the Tabernacles], several of the former “Vatsevitshers” were told to prepare to return there in a few days (this was the “compromise”). Yankl was one of them. It appears that he was depressed the entire time, although, externally, it was not particularly noticeable in him. By nature, Yankl was extremely full of life, a “whirl and dynamo” young man and a strong man.

He did not come on the morning on which he had to report to the headquarters to be sent back to Vatsevitsh. His housemates found him hanging from a fruit tree in the orchard behind the house. He had left the house in the middle of the night – from Motl Alter Kraszes' (Kowenski) house – and horribly committed suicide.

There were other young lives cut short, although indirectly, the victims of being in Vatsevitsh on forced labor. They began to be sick, mostly with tuberculosis and died in a year or two. I do not remember everyone, just the following names:

Shlomo the bookbinder – the son–in–law of Yankl–Dovid the melamed [teacher in a religious primary school] – a man of about 40. He began to get sick after returning from Vatsevitsh and died a short time later.

Hershl Wilentshik's (the butcher) daughter. I do not remember her name. Her lungs were severely affected. Not that there was no way to save her and not that they could not go to a great doctor. Immediately after the war, in 1918, her sisters in America sent money. She was taken to Warsaw. But great doctors and Otwock, the famous [sanatorium], could not save her. It already was too late.

[Page 140]

There were several others who died too young, left the world because of being in Vatsevitsh. Nine or 10 people in the group who originally went there perished. That makes up a fifth and it is a proportionally very large percentage.

The Germans already were liars, swindlers, slave drivers, bloody murderers, insolent cynics on all bases of morality, ethics and relations toward people in those years of the First World War when outwardly they still tried to maintain proper behavior and were prized as civilized.

Recorded October 1953, Ramat Gan, Israel on my visit to the country.

Original footnote

- Official name Iwacevicze, but in our folk–language we said Vatsevitsh. Return

Translator's footnotes

- The text first presents the above words in a transliterated form in which the Hebrew words are elongated to mimic the sound of singing. Below this transliteration is the Haggadah's Hebrew text. Return

- A pood is the equivalent of 40 Russian pounds or 16.38 kilos or a little more than 36 pounds Return

This material is made available by JewishGen, Inc.

and the Yizkor Book Project for the purpose of

fulfilling our

mission of disseminating information about the Holocaust and

destroyed Jewish communities.

This material may not be copied,

sold or bartered without JewishGen, Inc.'s permission. Rights may be

reserved by the copyright holder.

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Byten, Belarus

Byten, Belarus

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Yizkor Book Director, Lance Ackerfeld

This web page created by Jason Hallgarten

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 12 Jan 2020 by JH