|

|

|

[Page 9]

| We are faced with a single task: To ensure that the memory of the status and the fate of the Jewish community of Brody will remain with us in this generation, and for generations to come. |

| Aryeh Tartakover |

[Page 11]

by Aryeh Tartakover

Translation by Moshe Kutten

Edited by Yocheved Klausner

From the speech during the assembly in memory of the destruction of Jewish Brody, 21st May 1951, Herzliya High–School, Tel Aviv, Israel

The place occupied by the Brody Jewish community in the history of the Jewish nation and of the human society in general cannot be defined by standard social concepts. There were more the a few phenomena in this community, which one cannot find in other places in Poland or in other countries.

We should start with the most prominent phenomenon, which is unique in itself. Brody was known to be one of the wealthiest and well established communities in the history of the Jewish nation, both economically and as a center of Jewish culture and creativity. It was also considered, for many generations, to be one of the largest centers of Jewish Zionism and nationalism. Such a triple combination is rare in the history of the Jewish nation and in other nations of world. It is customary among nations that one city is considered to be the economical center, then another – the political center and a third city the cultural and spiritual center. An important and characteristic example is the English nation: Its capital – London, serves as its political center, the economical center is Manchester, and its cultural and spiritual center is Oxford (or Cambridge). This is the situation in most other countries. There are cases where the same place serves as a political and economic center, or as a political and cultural center. However, cases where a location serves as a triple center are very rare. Brody was one of the exceptions to this rule. Not only was Brody a city where an immense Jewish wealth was accumulated, but it was also home to people like Nachman Krochmal, Shlomo Yehuda Rapoport, Yehoshua Heshel Shor, Zvi Peretz Chayut and others, who helped to establish the city as the center of Jewish thought. At the same time, the city played a highly important role as a Zionist city and one of the centers of the national Jewish movement in the Habsburg Empire. Brody not only sent a representative to the state parliament, but some prominent Jewish figures excelled in their service to the Jewish nation and served in pioneering national roles. An example would be the banker Natan Kalir, who was bestowed a title of nobility by the emperor due to his significant achievements in the field of economy. At the same time, Kalir acted vigorously toward the fulfillment of his dream of Jewish agriculture in Galicia, although at the end he did not succeed – mainly due to the internal Jewish resistance itself.

How can we explain the mystery behind the city's special status? People tried to explain it using various directions of reasoning, all of them logical. It would be worthwhile to summarize them in a few words, before we find the most important factor, which was probably decisive in the way things have developed.

It is possible to claim, that the special status of the Brody community was achieved, because the Jewish population of Brody was a majority of the general population, most of the time. There were not many other places in the world where this

[Page 12]

majority status was as prominent as in Brody. Brody was essentially a Jewish city where the non–Jews represented small minorities. The Jews were living almost independently (outwardly, this could be observed particularly during the Sabbath and holidays, when the city took on a festive atmosphere and the economic life came to a halt). Thus, because of numerical advantage and internal unity, the Jewish influence grew in all aspects of life. There is probably a significant measure of truth in this assumption; population homogeneity would have paved the road for important achievements, and probably played a major role in determining the special character of the Jewish population from the days it first appeared on the stage of history until today.

There is also another explanation. Not only were the Jews a majority among the city population, but they were not subjected to the influence of the non–Jewish population which was itself divided – both nationally and culturally. Brody was one of the few places in Galicia where the German language had an important status among the non–Jews, over the Polish and Ukrainian languages. In time, however, the German language was gradually rejected by the Polish language, which in turn began to feel the rivalry of the Ukrainian language; in happened particularly at the time when Ukrainian nationalism started to thrive among the Ukrainian population, which was a majority in eastern Galicia. However, competition between the languages reduced the circle of influence of all three languages, particularly since the groups who used these languages were far from maintaining friendly relations with one another; instead of interaction among these cultures, rivalry and antagonism prevailed. Under these conditions, the process of social and national–cultural assimilation was limited, and every group – and in our case, the Jewish group – was able to keep its independence and capabilities.

There is also a third explanation, which, like the other two explanations holds some truth in it: The feeling of distinguished status in the people's minds and souls, as well as the wealth, wisdom, and Zionist spirit of the Brody Jewish community prevailed not only during one or two generations in the last two centuries. These values were acquired over many generations, during which the standing of the community as one of the most respected communities of the Jewish nation was crystalized. Brody's Jews wanted to preserve this distinguished status regardless of the external circumstances. They succeeded to do so even during the first half of this century, when the conditions that enabled the economic growth of the city changed, when the “Golden Age” of the Galicia scholarship, of which Brody was the center, was over and when – particularly after the First World War – the center of the national Zionist movement started to shift more and more toward other regions of Poland and Western Europe. Even under these changes, Brody knew how to preserve its status in which it found a great deal of moral support.

All these explanations are valid to a certain extent. However, even with the historic perspective we now have, when accepting these explanations we are neglecting one major reason. This exceptional phenomenon of the triple social importance of Brody's community cannot be explained just by demographic or ecological reasons, may their weight be as it may. The reasons for these phenomena are, without a doubt, much deeper. We need to uncover them, as only then can we see the full picture.

It would be beneficial if we present the big dispute about the foundations of the social life during last two centuries. These were the centuries during which the development of the social philosophy transpired.

[Page 13]

We are all aware of the brilliant definition (albeit a one–sided one) by the founder of modern socialism, Karl Marx, according to which the economy is the basis of all phenomena of the social life, including cultural and political phenomena. This materialistic view of the world that found its strongest expression in Karl Marx's thinking, succeeded to conquer the hearts and the brains of common people and the elites, and many favor it even today. However, it encountered a strong resistance, the signs of which were revealed even before the final realization of materialism. In particular, the signs were discovered as part of the Utopian Socialism at the end of the last century (in which ethics and faith were the essence). Utopian Socialism's main interpretation can be attributed to the greatest German sociologist (also one of the world's greatest) – Max Weber. According to Weber, the economy is not the basis of social life, but the other way around – the economy is a result of various social factors, first and foremost – faith. This is where Weber's explanation of the growth of modern Capitalism came from. In his opinion, Capitalism grew from the depths of the Christian consciousness of the Protestants and Puritans. God's spirit that burnt in the souls of these people motivated them to increase their efforts in all facets of life including the economic facet. According to Weber, work was loaded on man's shoulder by the command of God, and therefore man cannot enjoy the benefits of his work. According to God's commandment man needs to live a modest and somber life and thus his income becomes an instrument for the amplification of the economic life. According to Weber, this is how capitalism was born.

These are, briefly, the main elements of Weber's philosophy, which also, as stated above, was notable in its one–sidedness and subject to corrections by many. The main claim against this philosophy was that it was impossible to visualize it as applicable in all circumstances and for all nations; it was claimed that there is an abundant number of examples in which the application of Weber's theory is doubtful. This is where it becomes relevant to our case. If there is any nation in the world, where this theory could be superbly applied, the Jewish nation would be one of the first. Weber himself, in his book about the growth of the modern capitalism, mentioned the Jews as comparable to the Puritans and the Protestants. There is no doubt that there are similarities between these groups, the same way that there is no doubt about the preeminence of the Jews in this matter. It seems that what happened to the Protestants and the Puritans during the transitional period between the middle–ages and modern time, happened to the Jews at the beginning of their existence, and even more when they were scattered among other nations, while preserving their special way of life, concentrated around their tradition and worship of God. Their economic activity grew significantly, but it was strongly affected, like other facets of their life, by their faith.

Here is, probably, where the road leads us to the true explanation of the unique character of Jewish Brody. Its soaring economy had, from the start, a special character, seemingly unparalleled to what happened in other nations under similar circumstances (except in the case of the Puritans and the Protestants mentioned above), including Western European Jews under similar circumstances. There was in Brody a deep association between economy and

[Page 14]

faith (maybe even more correct to say, between the economy and the traditional Jewish culture). This traditional culture was also linked to political phenomena in the Jewish society. As there was no partition between the secular and sacred life, as life was organized according to God's instructions, so there was also no partition between the culture and the economy or between the culture and the political phenomena.

In this respect, the Brody Jewish community was one of the most typical in the history of the nation during the last two hundred years. Not in all places, the coupling of economic, cultural and political aspects thrived as much as in the case of Brody, since opportunities for Jewish initiative were not as widely available in other places. We know of only one similar case, although it involved a much smaller community – the Jewish community of Lodz, in Congress Poland. In this community, similar to what happened in Brody, the tremendous soaring in the economic life was coupled by the prominent cultural standing (mainly in education but also in the Hebrew and Yiddish creativeness). At the same time, Lodz was one of hubs for the Zionist activity in Poland and the entire Jewish nation. There is a great distance between these two communities, in space and time, as the Lodz community reached its prime while Brody has already accumulated hundreds of years of important achievements. However, Lodz continued in its full momentum thrust forward right until the holocaust, while in Brody, the signs of decline appeared already during the period between the two World Wars. Despite the distance, the similarity between these two cities remained deeply rooted, and both symbolize the Jewish ingenuity.

On these foundations the entire structure of social life – the affirmation of life – was established; not just life, but life based on ideology, the ideology that was centered around the phrase: ”I shall not die but live, to tell about God's acts”. This was the foundation of the Jewish economic activity as well, which was more a mission than just an activity, and of a deep–rooted, large–scale and multifaceted culture. This culture was expressed by the tradition (the “golden chain” of the Brody Rabbis), by the Enlightenment Movement, that won numerous accomplishments here, or by the New Culture movement (Secular Judaism) with its various branches. The Zionist movement blossomed here as well, conquering the hearts of the Brody Jews like an exploding storm, and the Jewish nationalism was established. It drew the conclusions from the Krakov Conference of 1906 very quickly, and made the slogan of “conquering the communities to achieve fulfillment of national rights in various institutions” into reality, with far reaching results.

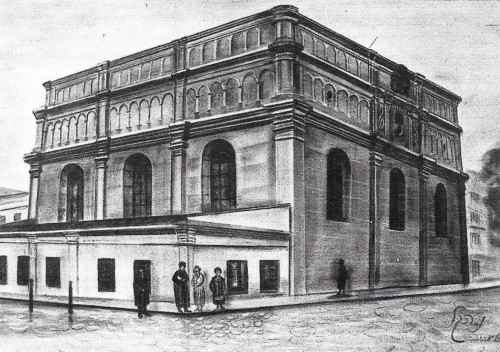

This was the miracle of the Jewish community of Brody. At the beginning of the century [20th century, MK], when you walked through the streets and open areas of the city, most of them ancient with seemingly strange names (The Golden Street, The Catholic Church Street, Yuridika Street, Ravik Park – named after the noble upon whose land the embankment park was built); when you passed through one of the alleys near the “Old” Synagogue, one of the most magnificent synagogues in Poland, where, according to tradition, Baal Shem Tov prayed, or near the “New” Synagogue, which was in itself an ancient building; when you walked by the Commerce and Industry Bureau, one of the three of this kind in the whole Galicia (the others were in Lvov and Krakow), probably the oldest one, and passed near the Community House that served as the National and Zionist center, always crowded with people at assemblies, meetings and lectures;

[Page 15]

when you passed by the government High–School, which changed its teaching language from German to Polish, and all of its Jewish students observed the Jewish holidays and most of them joined the clandestine Zionist youth–movement “Zion's Flowers”, despite the risk of being expelled from the school for this “sin”; when, at least while it was still possible, you saw the house where Yehoshua Heshel Schor edited his newspaper “the Pioneer” and Natan Kalir conducted his big businesses and dreamed of Jewish agriculture – then you would have understood the secret of the greatness of Brody's community despite the fact that it was not always possible to explain these phenomena according to ordinary logic, as the unordinary was above the ordinary here.

Only the memories are left from these great days that passed. The decline of Brody's community actually started during the twenties of this century (20th century, MK]. Even during Austrian Galicia, where poverty ruled, and much more when Brody was part of Poland that was bankrupt between the two World Wars, it was difficult to preserve the economic prominence of that community. It was also very difficult to preserve the cultural reputation, even though great effort was invested and some very important accomplishments have been attained. The worthy goal of the Enlightenment was successfully sustained by people like Chaim Tartakover, may his memory be blessed, and Nathan Michael Gelber, Mendel Zinger, Dov Sadan and others, may they live long. Although they were all born and educated in Brody, they carried its prominence to other places as well, and at the end to our free homeland. Whatever was left in Brody was destroyed during the Holocaust, as the entire Jewish–life was destroyed in Poland by the villains.

Today our responsibility is to make sure that the memory of the prominence and greatness of the Brody Jewish community will stay with us and with future generations. This is not only a matter of emotions, although emotions are important. There is also the lesson that we can learn from our experience in Brody, for the benefit of our future. If we know how to keep the deep–rooted foundations, from which all of these phenomena grew in the Brody community, melted into one unified concept, then our old tradition will come alive again and become the guide toward a future of honor. This would bring in its footsteps the salvation of our nation, and would have an impact on all those created in the Image of God. This is the commandment by which we all need to act.

[Page 16]

|

|

|

|

In the background part of the Old Synagogue |

by Simon Sauber

Translation by Moshe Kutten

Our memorial day ceremony is approaching. It is now 25 years that I prepare for this day every year.

The hall is always full. However, the change that occurs from one year to another is that our guests are getting old... and not only that.

Every year, we are being told that a certain person or an unknown person separated from us forever. Every such news is saddening and gloomy. It is thinning our lines and they would never fill up again.

We are all representing one generation. Although Brody still exists on the geographic map, it is not the same Brody and its residents are not the same residents. Therefore, I see the unique value in the meetings of Brody natives who live in Israel, sometimes with the participation of Brody natives who are scattered in all corners of the worlds, and all of whom are attracted to these meetings and they fill an emotional need for them.

This is the place to mention the arduous work invested by our comrades, especially by our friend Mr. Yosef Leiner (Parvary), who devote a good part of their private life to the organization of the meetings.

Despite of that, I feel sometimes a certain coolness and formality in these meetings. What is the reason for that? Are we fed up with these meetings? Do the worries of the daily life and daily events dull our memories? …and what memories! These are memories from our childhood and youth, which would never return - memories from the days of school, the images of our teachers, our classroom boyfriends and girlfriends, and of course the images of our closest relatives – our family members. Then there were those first steps in the Zionist youth movements and our songs, which were not very successful I may add, not very successful I may add, to our first loves.

Did we forget all of these memories?

Perhaps we are too burdened with our life experiences, or maybe because of our social status we do not want to return to the days in the past even in our memories. What a pity! This is too bad!

We often do not even recognize each other! It is possible that my old time friend, even my brother, with whom I lost contact forty years ago, is sitting in the same row and we simply do not recognize each other? Perhaps the passing years and our experiences are the cause or perhaps the cause is the fact that we changed our surnames or the authorities of the countries that our fate led us to changed them.

The irony of fate!

It is possible that my surname or my first name have been forgotten. However, my nickname from the school days, “White Sauber”, or “Philosopher” were certainly etched in the memory of people who were close

[Page 18]

to me. It is possible that people can't remember the name Pestes, but they do certainly remember who was “the orphan without a grandfather”.

Perhaps the school I went to, or my home address or my work can remind people who I am? Perhaps there are fortunate people among us who possess group pictures from those days? What an idea! We have to revive these old pictures from the period of our youth, in our heart and in our memory!

This idea does not force anybody to stick a sign on the forehead, a note on the wall will suffice, or perhaps, it is preferable that our organizers would publish a booklet or pamphlet where everybody can describe and record a portrayal of oneself, and where old pictures from those years can be copied and published. I am convinced that such picture booklet would revive in our heart and memory everything that we have lost and was gone into oblivion, and will provide us satisfaction, happiness and the possibility to cling to our past and our youth that have been robbed away from us. Let this project cost as much as it would – it is a worthwhile thing to do!

I recall the last “memorial service”. I was sitting in one of the rows. My wife was sitting by me, and several people, whose company I join to attend all the memorial services, were sitting around me. There were Polak, Vilner, Pestes, Shweibish and several others who are my friends from my youth. Who are all of the rest of Brody people who fill this hall to capacity?

At a certain moment, my wife turned to me and asked: “Tell me Shimon, Brody was not such a big city, the Jews were only part of the population and the people sitting here are all about the same age as yours, so why aren't you recognizing each other?”

How could I answer her question? I did provide some answer, but the stone she threw at me hit a very sensitive point in my consciousness. If I ignore the fact that drove me through different and strange roads and trails, I did spend my childhood and youth in that city among the people who gathered here.

From that point on, I could no longer listen to the talk given by the lecturer, or the stories, told by my friends around me, about their children and grandchildren. I immersed myself in my memories, and my eyes scanned the faces of the people around me with excitement and great suspension. How could I visualize these old people, whose hair turned gray, as my friends from my youth? How can one return to events and experiences that happened fifty years before?

Not everything has been forgotten!

I do remember our little apartment in the backyard of Gross on Kolejowa Street, along with the statue of Little Jesus, the fruit trees, and the cellar, in which ice was stored during the winter. I do remember vividly the cowsheds in the neighboring yard of the Grosskopf's. I see in my mind the barn attic above the cowshed, where we, the little ones, established a “hospital” as a game. I do recall that I always wanted to be a “doctor” rather than a “patient”.

I ask myself: ”who among the people present in this hall, was a participant in these games?” Perhaps the tall woman, sitting in the third row, is Henia Grosskopf? …and that little woman, sitting near me, is she the daughter of the Gross's? At her wedding, which took place at the Kelper Restaurant, I tried for the first time the bitter taste of the alcohol…as a close neighbor, almost a family member, I was asked by old Mr. Gross to collect the empty wine bottles from the tables. I was a ten years old boy at the time and I executed that mission with an exaggerated diligence.

[Page 19]

I did not forget to drink what remained of the wine at the bottom of the bottles. As a result, my parents found me, after a long search, deep asleep, under one of the tables.

That person with the gray hair, who is sitting in the first row, looks so similar to Sheinholtz, our religion teacher. It is true that whoever was fortunate to study under the other Hebrew teacher, Mr. Lerner, learned Hebrew properly; however, with Mr. Sheinholtz we studied the history of the Jewish nation, in Polish. I even remember his catchphrases: “When the Israelites won – the Amalekites ran away” (the phrase rhymes in Polish – and it sounds amusing). The phrase is stuck in my memory as if I heard it yesterday. Therefore I ask – is that man, sitting there, him? …or if not, who is he?

Memories follow memories. We moved to an apartment on 3 Rynek Street, where the Ponikova Beer warehouses were located above the apartment of Rabbi Popper. I have joyful and fascinating memories from there, formed on the joyous and lovely Jewish holidays at the Rabbi's house who celebrated them with all of his Hassidim.

There are also the delightful memories of first love of the thirteen years old Don Juan to my neighbor Papka Bel'or, and later on to her cousin Lola Frenkel. I recall the answer of that twelve years old “dame” to me: ”Jak Kuba Bogu, tak Bog Kubie” (literally – “whatever Jacob did to G-d, G-d would do to Jacob”; meaning “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”). Perhaps these girls are sitting here among the attendees.

…and perhaps, my other neighbor, Shveibish is here? She lent me her blue underwear for my appearance on the school's stage playing the part from “Guralu Chi Chi Nie Z'al?” (“Native of mountain-land, aren't you sad?” – the opening of a popular folk song). I am not sure whether I looked like a “native of mountain-land” on that stage, but I do remember vividly the spectators' surprised and astonished face expressions to the blue “feminine” underwear. Perhaps these Brody's beauties are here, at this moment, in this hall. …and you, my good friends from the meetings of the Zionist youth movement, do you remember our trips to the forest in Radzivilov and the beautiful songs we used to sing? Are you here among us now? I think yes. At least some of you are sitting here. The only thing is that we changed so much until we do not recognize each other anymore. Everybody closed themselves in their own home, and the years that passed blurred the rest of signs.

I do not think that you are indifferent to the memories from those happy days, which were certainly etched deep in your heart, like in mine. Therefore, I have a request: throw away your titles, honor and seriousness. Go back to the past for a moment. I promise you that this would be an unforgettable experience. We can sit here in a circle, as we used to sit in Ostrovchio, or in Radzivilov Forest, and you would be seen as you were in your youth. Even you, my friend, who thought once that the wealth of your father distinguishes you from the others, children of the poor, come and break the barrier you built to be different. Believe me, when we went to the public bath on Fridays with our grandfathers, we exposed our shiny behinds, over there on the upper rack, and they all seemed to be amazingly similar.

…and you, my city Brody's native, who this days “sits on the top of Olympus” in Tel Aviv, Haifa or Jerusalem, and chooses to participate with us solemnly in this memorial ceremony by sending wishes through the telephone or via a telegram – wake up! Throw away, just for one day,

[Page 20]

your titles, and your status halo, come down and sit down with us, for one evening, on this hard bench in this hall. Forget about the fact that you are a professor, doctor or manager and remember that you are the same Khayim, Moshe or Avram, who is made of the same diaspora material and who came from the same small town like the rest of us.

Do you remember how we played football in Ostrovchik, and how as small children, we carried on our shoulders the shoes of the Jewish football players, Bumza and Kantor, in order to be able to get into the stadium for free? …or perhaps you joined me once when we jumped the fences over to my neighbor's orchard to steal some apples off the trees, and like everybody else returned home with apples in your shirts and a hole in your pants.

Believe me that it is worthwhile to forget, for one day, the daily hardships and go back to memories from the old days. Those days would never return, but these memories would remind you about unforgettable experiences among people who were also born in Brody.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brody, Ukraine

Brody, Ukraine

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 13 May 2017 by MGH