|

|

|

|

|

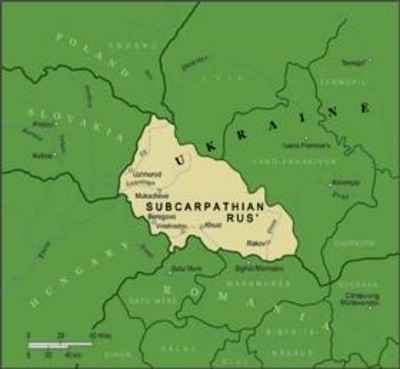

| The area marked in yellow was called the Subcarpathian Rus. The area was annexed by the Soviet Union following World War II. |

The region that was known as Subcarpathian Rus lies in present–day Ukraine, and is now known as Zakarpatska Ukrajina. The area became part of Czechoslovakia following World War I and remained Czech until Czechoslovakia was dismembered by Hitler in March 1939. Then the Hungarians annexed the area.

The first Jews likely settled in the area during the Turkish occupation of Hungary (1526–1686); they were probably of Sephardic origin. Later, a tiny stream of Moravian and Bohemian Jews arrived via the northern Slovak counties. The major influx of Jews, however, occurred in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and consisted of migrants wandering southward from Galicia. The newcomers were welcomed by Magyar magnates, in particular by the Schönborn dynasty, which owned much land in the area. The Jewish population rapidly increased: in 1840 there were 21,640 Jews, a number that rose by 1880 to 83,076; by 1921 to 93,008; and by 1941 to 162,065 Jews. The population growth after the mid–nineteenth century can be attributed primarily to natural increase; the region had one of the highest fertility rates of European Jewry. Most of the Jewish population was very religious and the Hasidic movement was very popular among the Jews in the area. Neolog (Liberal) Judaism appeared in Ungvár (Uzhgorod. Uzhhorod) and Máramarossziget (Sighet Marmației) but was small in numbers. Zionism also made its appearance, especially among the youth.

The area was poor and over populated. Many Jewish inhabitants were unemployed and sometimes homeless. Those gainfully employed included manual laborers in forestry who worked as lumberjacks, in agriculture and in artisan shops. Jews engaged in banking, wholesale trade, estate management and industry, especially timber.

During the existence of the Czechoslovak Republic, Jews could assert Jewish nationality and enjoyed all political freedoms. In 1930 the Czech government conducted a nationwide census that gave the inhabitants of the country a choice to state their cultural and linguistic preferences. Of course, they were all citizens of Czechoslovakia. The residents chose their preferences, including Czech, Slovak, German, Hungarian, Jewish, Ukrainian and Russian. A sizable portion of the Jewish population, including the family of writer Franz Kafka, chose the German culture in which they were raised. Some Jews chose the Hungarian culture, especially in Slovakia, and some Jews selected the Yiddish culture, especially in the Subcarpathian region.

With the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia, the Hungarians seized the Subcarpathian region and began the persecution of Jews. Jews who did not have proper legal Czechoslovakian papers were harassed even if they had lived in the area for generations. Starting in late July, in just a few weeks, the Hungarian authorities transports approximately 17,000 Jews across state borders to areas occupied by German troops. In late August the majority of these people (around 15,000) were machine–gunned into mass graves by SS units in the outskirts of Kaments–Podolisk.[1]

Young Jews were drafted into labor battalions where they would perish later on the Eastern front. Jewish companies were “arayanized” or seized and given to Hungarians. The Jewish population was slowly pauperized. Then the Germans invaded Hungary and rounded up the Jews of Hungary and the Subcarpathian region and deported them to Auschwitz between April and July 1944. Most of the deported Jews were murdered.

Soviet troops liberated the Subcarpathian region in the fall of 1944 and immediately annexed the area to the Soviet Union. The borders were closed to the outside world, and international aid organizations such as the Red Cross, the JDC and even UNRRA were not permitted to operate there. Nobody could leave the Subcarpathian region except those who were Czech, Slovak, Hungarian or German citizens. Citizenship was determined by the birthplace or cultural preference sheet that each person signed in the census of 1930. Jews who selected the Yiddish culture were not permitted to leave the area. The surviving Shoah Jews felt trapped and began to look for ways to enter Czechoslovakia. The Czech Brichah and the JDC helped these

|

|

| A typical roundup of Jews in Hungarian–held areas prior to their deportation to the gas chambers in Poland |

Jews escape.

William Leibner, author of this book remembered illegally crossing the Polish–Czech border and reaching the city of Brno by train. His group of illegal Polish Jewish refugees was joined by another group, supposedly from Poland also. But their Yiddish was not similar to Polish or Ukrainian Yiddish. Leibner asked his father, Jakob, about the strange speech patterns and was told that the Jews were from Czechoslovakia. The group actually consisted of Subcarpathian Jews who were smuggled out of the area under false Polish papers. On reaching Prague, the Subcarpathian Jews were immediately sent by the Brichah to the Czech–German border to reach safety in one of the German DP camps.

The Soviet authorities were aware of Jews disappearing from the Subcarpathian area and decided to act. They began to pressure the Czechoslovak police to expel all Soviet citizens from the country. The Czech police had no desire to comply with this request even though it was repeated several times. The Soviets decided to take control and ordered the Soviet NKVD or secret police to prepare an extensive dragnet to seize all Soviet citizens in Czechoslovakia, mainly Jewish citizens from Subcarpathia, and deport them to the Soviet Union. Zdenek Toman, head of Czech secret service, got wind of the plan and decided to act. He sent a letter to the Berman family to visit his office in Prague.

Nicholas and Gisele Berman knew Toman and his family. Gisele Berman was born in Sobrance as was Toman. Both went to the local school and later met in Uzhhorod, the provincial capital of the Subcarpathian area. Nicholas Berman was born in Uzhhorod and met Toman at the local high school. Nicholas and Gisele Berman married prior to the war. Both were deported and barely managed to survive. Gisele Berman returned to liberated Sobrance but found no surviving family and the few Jews there did not welcome her. She decided to move to Uzhhorod where there were more Jews. She also needed to recuperate and restore her health. She kept searching for family, mainly for her husband.

Aranka Goldberger, sister of Toman, also had returned from the death camps but found no survivors. Aranka Goldberger was born as Aurelie Goldberger on April 8, 1918 in Sobrance. She survived the Sipa Riga camp and Stutthof concentration camps.[2] She was liberated by the Soviet Army, reached Sobrance but found none of her family, so she too moved on to Uzhhorod.

|

|

| The Uzhhorod synagogue |

Gisele Berman soon received the news that her husband, Nicholas Berman, had survived the Shoah but was gravely ill in a hospital.[3] She began to search desperately for transportation to Prague but none was available. She then met Aranka Goldberger and told her the problem. Aranka informed Gisele that her brother, Zdenek Toman, was sending a car to bring her to Prague. She offered Gisele a ride that was immediately accepted. The two women drove to the hospital and located Nicholas. He needed medication that the hospital did not have, but was obtained with the help of Toman and his sister. Nicholas slowly recovered and the couple settled in the City of Decin in Czechoslovakia near the German border.[4] The city attracted many Jews from the Subcarpathian area. Life in Decin was better than in many other places but there were terrible food shortages. Gisele returned to visit Sobrance where a small Jewish community had begun to function. With the help of the JDC, the Jewish community would reach about 200 members.[5]

The great majority of the Jewish survivors were from the district and not from the city proper, according to Anna Neufeld.[6] Most of the Jews left the city in 1949 and settled in Israel. Gisele also visited Uzhhorod and saw a small Jewish community that struggled to exist within the Soviet economy. Most of the Jews of the Subcarpathian area would leave the region with the help of the Brichah. It is estimated that between 6,000–10,000 Jews

|

|

| Jewish transients waiting for the train in Bratislava, now in Slovakia, to take them to the DP camps beyond Czech borders |

were smuggled out of the Subcarpathian area.[7] The Brichah and the JDC were deeply involved in this dangerous game but managed to get most of these Jews out of the area and into Czechoslovakia, whereupon most of them left the country under Brichah guidance.

Zdenek Toman was also very involved in these operations and managed to save a large number of Jews like the Berman family. The Berman's received an invitation from Toman and were afraid to open it. The letter merely stated that Toman wanted to see them in his office at their earliest convenience. The name of Toman was feared throughout Czechoslovakia. Few people had met him but his name and his office were enough to scare any citizen. Toman received the Berman's and told them that they had to leave Czechoslovakia if they wanted to live. He let them know that the Soviet secret police would soon begin to round up all Soviet citizens in Czechoslovakia, including Nicholas Berman who was born in Uzhhorod, and deport them to the Soviet Union. Toman further stated that he would not be able to protect the Berman's if they were arrested and urged them to leave immediately. They started to look for relatives in the United States who could send the necessary papers. The Berman's warned other Jews and they too began to make plans for a hasty departure. Toman also informed Jacobson of the impending Soviet police action. The Soviet secret police soon visited the JDC offices in Czechoslovakia and various Jewish aid offices but did not find many Soviet citizens.

The entire operation produced little for the Russians. The Berman's managed to reach the United States along with many Subcarpathian Jews. Others reached Britain and the DP camps in Germany and Austria. The Soviet police knew that somebody had leaked the information but did not pursue the matter.

Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Brichah

Brichah

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 24 Mar 2017 by JH