|

|

|

[Column 86]

10. The Workshops and Employment in Forced Labour Camps

In order to give this new propaganda slogan the appearance of truth, the Germans began to set up work outposts where only

|

|

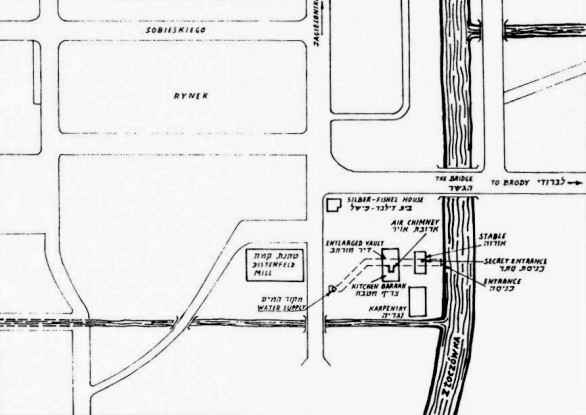

| Wiklicky bunker plan |

[Column 87]

Jews were employed. These were big private firms, the S.S. or military institutions. The Jewish community and its leaders fell readily into this trap not sensing what was behind it. A race for work began and even more for work-certificates (the so-called “Arbeitsausweis”), which, bought at a high price, gave their owners a doubtful security for an even more doubtful length of time. Because of the demand, prices varied according to the category of the work and the financial capacity of the buyers. In order to make all this appear more credible, employment cards were classified according to the importance of the place of work: -

Every owner of an Ausweis had the corresponding letter market on his armband. By order of the SS Camp Commandants began to set up new, smaller camps called Nebenlager around the original mother camps. Warzok, who was very business-like (he was a business agent by profession), was one of the first to organize a number of small workshops in Zloczow which were affiliated to the main camp workshops as the name indicates: (“Zwangsarbeitslager Lackie, Nebenstelle Zloczow Lagerkwerkstätte”). The main workshops were in the house of Engineer Alda at Lwowksa Street opposite the Jewish Hospital. The Ettinger bakery, in which I was working, was also requisitioned for a workshop in which Jews were to replace Ukrainians. The camp workers wore yellow armbands and had special certificates with the letter “L” (Lager Juden).

[Column 88]

At the time of the hectic search for life-preserving “Ausweise”, Israel Strassler, the owner of a little sweet factory in his house at Rynek, asked me to have Mr. Meyer use his influence with the Food Department to take over his factory which would then supply its entire output to the “Deutsches Lebensmittle-Geschäft”, the only German grocery in town. Strassler and his sons rightly calculated that if their suggestion were accepted, the workshop would become a place of employment and a haven of safety for a few Jewish families under the protective wings of Mr. Meyer. This proposition seemed sound and also appealed to me personally, for an event had taken place in the bakery a few days earlier which nearly cost me my life.

One night-shift, an offence was committed at the Bakery. Usually only Ukrainians worked at the Bakery during the night-shift but that night, the Jewish baker Schleicher was temporarily replacing the Ukrainian baker. The next morning SS officer Salzborn, the deputy of Warzok, dropped in at the Bakery and took away the Ukrainian Bakery Manager, Schleicher and myself to the Lackie camp. The manager was decent enough to point out that I was absolutely innocent as I was employed only during the day. The full weight of the accusation thereafter fell upon the unfortunate Schleicher who was promptly suspended from the legs, head down, until death ended his slow agony. I escaped with a few lashes.

Mr. Meyer readily agreed to the Strassler proposal and in addition entrusted us with the job of producing a mixture of cooked potatoes for the bread[12] so as to give our

[Column 89]

enterprise more validity and an appearance of greater usefulness to the local German Food Administration.

This little factory, which was affiliated soon after to the camp workshops, became an island of rescue, and an asylum for a few families who eventually survived the extermination.

11. Gestapo in Sight

A new and threatening shadow fell on our town the moment a Gestapo branch, whose district head office was in Tarnopol, was established. This institution was the dread of the whole population including the Germans themselves. Its tentacles reached out to every sphere of life, particularly Jewish life.

From the first moment the Judenrat tried to make some kind of contact with the head of the local Gestapo, one Ludwig and later on with his counterpart in Tarnopol, Müller. This task was undertaken by Zuckerkandel who went to Tarnopol for the purpose. Thanks to the intervention of Fleischer, a member of the Tarnopol Judenrat and with the help of some expensive presents, Zuckerkandel succeeded in reaching Müller himself. Zuckerkandel returned with an order to form an intermediary body (“Geschäfts-

[Column 90]

stele”) between the Judenrat and the Gestapo as in Tarnopol. This task was again entrusted to Zuckerkandel with Dr. S. Kahane as his secretary.

The first step taken was to provide sufficient funds for this office. These were collected from all the “Judenräte” in the district. Soon after, Müller 'graced' our town with several visits which extracted truckloads of gifts, not to speak of the jewels and precious stones that Zuckerkandel personally took to him to Tarnopol. It should be mentioned here that Zuckerkandel's intervention usually met with success, though only in small and unimportant matters.

The first victims of the Gestapo were Dr. Ambos and Mr. Aryeh Steinman, the former director of the Bacon Factory. One day they were suddenly arrested and taken away to Tarnopol. At the requests of their wives, Zuckerkandel was sent to intervene on their behalf but Müller told him that it was too late as he had already ordered them to be shot.

Besides the Gestapo, there was another authority, the “Kripo” (Kriminalpolizei) which inflicted much suffering on the Jews. One Polish detective – Ebert was particularly obnoxious. This rogue used to lie in wait for the Jews, secretly leaving the Jewish quarter – which was forbidden under penalty of death – in order to buy some food from the farmers. He pounced on these Jews ruth-

[Column 91]

lessly and arrested them, only agreeing to let them free for a ransom which his partner, a Jewish militiaman, would fetch from their families.

The “Gendarmerie” under Commandant Schwarz, was kept busy watching for Jews who dared leave their ghetto. Caught by the gendarmes, they would pay with their lives, as freedom of movement was limited even in the town itself, not to speak of outside its borders and inter-urban movement was strictly forbidden to Jews and punished with death. Is it any wonder that the Jewish communities were completely sealed off from one another and had no information as to what was going on? Sometimes nebulous gossip leaked through, spread by Ukrainians or Poles. Its credibility was usually doubted.

12. The First Alarm

The first alarm pierced the hermetically sealed walls of our town because of a tragic

[Column 92]

accident. In the spring of 1942, Herman Friedman, the representative of the Okocim Breweries who remained in his position under a Ukrainian manager and travelled with him on business to Lwow, was arrested by the Gestapo on his arrival there. As the Beer Warehouses were under the control of the Food Department, Friedman's daughter, Lusia and married to Hessel (who now lives in Warsaw) came running to me for help – for Meyer's intervention. Meyer tried to use his influence and declared that he himself had sent Friedman to Lwow on behalf of his department. His effort was of no avail as Friedman had already been put to death. (It seems that American dollars had been found on him). But Meyer's visit to the Gestapo was not in vain. On that occasion he came to know that in Lwow and neighbouring towns, some action was due to take place against so-called unproductive elements (Aussiedlungs-Aktion). On his return, and assured of the strictest secrecy as to the source and person from whom he had obtain this

[Column 93]

information, he asked me to warn the Judenrat, which I, of course, immediately did.

The Judenrat, like all civic bodies, usually contained two opposite groups: one of pessimists who had no illusions as to the tragic fate awaiting the Jews; the other of optimists who believed that every difficulty could be overcome with bribes and gifts. The optimists were sceptical as to the authenticity, arguing that if it were true, Zuckerkandel would know about it. Their naivety and blindness went so far that Dr. Gruber scolded me for spreading defeatism and panic instead of encouraging the people.

The Judenrat decided to send Zuckerkandel immediately to Tarnopol to see how the wind was blowing. He returned with the reassuring news that, as far as could be seen, nothing threatened Zloczow.

In spite of this good news, tension and fear were felt in the Jewish streets. Everybody tried frantically to get some “Ausweis” or other. Trade was brisk not only in real certificates but also in forged ones. All sorts of cheats and crooks exploited the situation. There even arrived a “specialist” from Lwow on forging documents and passports in Aryan names.

Others, more careful and practical, did not trust all these papers and began to build secret hiding places and well-camouflaged shelters. I myself was taken into confidence by four parties who decided to erect such shelters: (1) Strassler; (2) Furgang; (3) Munesh Margulies and (4) Barash at the carpentry.

13. The Beginning of the End

The Nazi began to carry out their plan of annihilation by instalments. After other towns, the turn of Zloczow came too.

In the middle of August 1942, Zuckerkandel

[Column 94]

was suddenly summoned to the Gestapo in Tarnopol. There, Sturmbannführer Müller told him that the Judenrat was called upon to supply 3,000 people who fell into the category of “unproductive”. He, of course, used the well-known propaganda trick that the removal of the unproductive elements was for the good of the community, as their elimination would ease the unbearable food and housing situation. At the same time, he added a warning that in case the Judenrat refused to comply with the order he would stage a “wild action” on his own in which he would take everybody he could lay hands on. Zukerkandel returned with Fleischer, the go-between of the Judenrat and the Gestapo in Tarnopol, who was supposed to help him to convince the Zloczow Judenrat to carry out Müller's order. Fleischer stated at our Judenrat meeting that the Tarnopol Judenrat had made a compromise approved by the Rabbinate. (This statement was false).

Frantic, dramatic consultations began. They were secret. There were single votes for the compromise but the majority were against it as nobody wanted to burden his conscience with such a crime. Fleischer returned to Tarnopol without a definite answer and had to report to Müller that the Zloczow Judenrat was about to take a final decision and that it would take some time to compile the list of the victims.

In spite of the well-guarded secrecy of the deliberations, the news of the Gestapo demands spread like lightning. I cannot find adequate words to describe the panic and terror that seized the community. Though a mortal blow had been expected for some time, nobody knew how or when it would fall. There had been no warning of it and now here it was! The sly Nazi bandits had even kept wagons in readiness for the tragic load.

[Column 95]

Late in the night of 27-28 August, Zuckerkandel was called to the local Gestapo at Podwojcie. He was accompanied by two Jewish militia men. (One of them was Landau). Müller was waiting for him. When asked for the list of the victims, Zuckerkandel, afraid to disclose that the Judenrat had refused to draw it up, stated that it was not ready yet. Müller yelled: “…You swine! I shall show you what the Gestapo is like”.

Meantime, one of the militia men who accompanied Zuckerkandel noticed a number of big trucks with dimmed lights at a distance near the brick factory (Cegielnia) on the Tarnopol highway. He deducted, or perhaps sensed instinctively that those trucks had been brought by the Gestapo for carrying away their victims.

Not waiting for Zuckerkandel, the militia men ran back to town and informed everyone they met about their misgivings and fear. This warning travelled like wildfire! People did not wait for any confirmation of the news but began to hide wherever they could – in shelters, cellars, garrets, lifts and holes. Some just barricaded themselves in their flats. I left my family in Furgang's shelter at Lwowska Street and myself, remained with the Strasslers.

It will never be known whether Müller told Zuckerkandel about the impending action on the following day. Zuckerkandel vehemently denied that Müller had said anything about the action. He claimed that he only received an order to appear at the Judenrat building at 7a.m. the following day, together with all the members of the Judenrat and the militia men.

On August 28th, in accordance with Müller's order, Zuckerkandel with a few members of the Judenrat and most of the militia men, reported punctually. At 7 o'clock, Müller drove up to the Judenrat building,

[Column 96]

followed by a long line of trucks manned by “Rollkomando”, SS and Ukrainian militia men. At the same time, a detachment of local gendarmes arrived on the scene. On seeing that only a few members of the Judenrat were present, Müller ordered Zuckerkandel to bring the rest with the help of the Jewish militia. This he did. Only Dr. Schotz was missing. Guessing what was in store for the Jews, he had hidden himself together with his family in the house of his Polish neighbour, Soltynski.

From the moment of his arrival, Müller was struck by the extraordinary quiet and complete inactivity in the Jewish quarter which was like a house of the dead. Asked about the reason for this lifelessness, Zuckerkandel stammered and gave lame excuses. Müller, suspecting that the Judenrat had warned the people, was enraged and roared like a wild beast: “– You cursed dogs; you shall pay for this dearly!”

Just then an SS Officer entered the room and declared that all the Jewish houses were locked and that nobody had responded to the call of his men to open them. Müller, now furious, ordered the Judenrat (with the exception of Dr. Mayblum who was ill at that time) and the Jewish militia to go out into the streets, each with an axe in hand. He divided his men into small groups, each led by a member of the Judenrat and a few militia men. At the point of the SS men's bayonets and under incessant beating by the butts of their rifles, these unhappy people were compelled to lead the way to Jewish homes, to break open the doors and to expose their terrorized occupants to the savage brutalities of the Nazi attackers. Old and young, sick and invalid, were forced out of their flats, cellars, nooks and corners by enraged beasts in human guise. The children's cries mingled with the wailing of the women and the moans of the beaten

[Column 97]

men. Above all was heard the wild yell of the Nazi: “Los, los – schnell! (out, out – quickly!). The turmoil was accompanied by ceaseless bursts of gunfire as Müller had ordered his men to shoot anyone who tried to escape. Once again the streets of Zloczow were strewn with the dead. It is impossible to delineate these blood-curdling scenes. Only two remain in my memory which I saw with my own eyes together with Wilo Freiman of Strasslers.

The late Marcus Smal who lived next door to the Strasslers was a corpulent man but owing to prolonged starvation, he became terribly bloated. Pursued to Ormianska Street with whips and blows, he could hardly keep pace and Müller ordered him to be shot. His order was promptly executed by a gendarme named Hirsakorn. The corpse was left for three days in the yard of a relative who buried him after the “action” had stopped.

The other incident also took place Ormianska Street, near the Judenrat. Müller ordered all the sick in the new Jewish Hospital to be taken away. Among them was a teacher, Samuel Schwarz who had gangrene in his foot. He asked the SS man to release him or shoot him as he had been an officer in the Austrian army during World War I. The SS man, himself an Austrian, wanted to let him free but Müller, who happened to be nearby, had the Jewish patient mercilessly shot.

The “action” lasted two days. The “hunted” were driven to a collecting point in the old Market Square, and from there, were sent to the railway station where they had to wait for a goods train. At the station, and later in the carriages, scenes from the inferno were enacted. The people were entirely without food but worse than the hunger was the thirst in the terrific heat of August. The Ukrainian hyenas, taking advantage of

[Column 98]

the suffering of the Jews, sold bottles of water for 100zl (about 2 dollars) each. The Ukrainian militia on guard exceed their SS colleagues in brutality and ruthlessness. Some German guards tried to help the unfortunate people. When their superiors were not watching, they fetched a bucket of water or even a little bread for the hungry children. The Ukrainians in such cases called the attention of the SS men, to prevent such little mercies.

When the cattle train finally arrived, people were loaded like animals: 100 and more to each wagon. People choked from the heat and lack of space. Müller moved constantly between the town and the railway station, personally supervising the loading of the “goods”. Eye-witnesses told us that the officer in charge, wanting to put an end to this terrible work, submitted to Müller a bigger list than he had actually loaded. To be on the safe side, he supplemented the number with the bodies of those who had been killed earlier so that the wagons were crowded with the living and the dead.

During the loading, Warzok appeared at the station to take back a few of the inmates of the camp but without their wives and children. Among others he tried to take back, Mann – the brother of Mrs. Sternchuss – but he was not allowed to have his wife Noemi, née Spanier, join him and he voluntarily returned to the train.

On 30th August, in the afternoon, the “death” train left in the direction of Lwow-Belzec. In spite of strong guards and sealed locks, some people who probably smuggled some tools with them, managed to break the doors during the journey and jumped out of the running train. Ninety-nine per cent of such escapees were fatal. Most of the desperate escapees found death under the wheels of the running train. Very few indeed succeeded in saving their lives and

[Column 99]

survived the war. One of them is Mrs. Irena Poplawska, née Rozka Lerner, and her seven year old son Jurek, who now lives in Haifa.

Having completed his murderous task which costs about 2,500 lives, Müller levied a tribute of 200,000 Zloty on the Judenrat to cover the cost of the “action”.

Later, we learnt from Mrs. Poplawska and some Polish railwaymen, including the train driver that the train had been sent to the liquidation camp in Belzec.

After the “action” the “Rollkommando” units vanished. Once again mortification, silence and mourning enveloped Zloczow. People slowly began coming to enquire about the fate of their dear ones who had been carried off. Some preferred to go on deluding themselves and would not believe the bitter truth.

The uneasiness of the people found an outlet in quarrels and heated arguments in the Judenrat. Once I heard Dr. Glanz accusing Dr. Mayblum and insulting Dr. Schotz, calling the latter a coward because he had hidden himself during the “action”. They nearly came to blows. Dr. Schotz said that he had done no harm to anyone by his absence and there was nothing to prevent anyone else from doing the same. Some of the people condemned those members of the Judenrat who took part in the action. But, the vast majority did realise the extenuating circumstances which accompanied this tragic event – and that one had no right to condemn a person who acted under brutal compulsion and whose only alternative was suicide.

After this “amputation” of the community, the Nazi, following their consistent line of deceit, tried to persuade the Jewish leaders that now that the deportation of the unproductive elements had been completed, normal and peaceful conditions would

[Column 100]

return. Unfortunately, there were still some naïve people who believed them.

Not long after the deportation, I visited Mr. Meyer and told him all about that “hunt”. Shocked to the depth of their hearts, he and his wife wept and wrung their hand in helpless despair and Mr. Meyer cried: “For God's sake, why do you go to slaughter like defenceless sheep?” But he immediately corrected himself, apologized for his words and said: “The German people and other nations are also helpless in the face of this Godless brood. Be on your guard and don't believe the treacherous assurances of these murderers. They will certainly go ahead with their devilish game”.

His prediction was fulfilled only too soon. Fundamental changes in the administration dealing with the Jewish population were introduced soon after. In spite of the reservations and protests of some high German dignitaries as well as a few generals[13] the whole Jewish community was transferred to the care of the Gestapo and the SS. The so-called: “Work-centres” were closed down and from now on, only Gestapo representatives might decide whether a certain workshop was to continue to operate and how many Jews were to be employed in it. A new order appeared annulling all “Ausweise” – work certificates – unless they were re-confirmed and signed by the district Gestapo official. Zuckerkandel was assigned to deal with this matter.

The Judenrat called on all holders of the “Ausweise” to hand in these life-giving, priceless documents – passports to life commonly and ironically called: “Hoshanah Rabah Quitlach” (Mighty Salvation Slips) in order

[Column 101]

to have them renewed by the Tarnopol Gestapo. Fees had to be charged for this transaction as it was impossible to go to Müller without a handsome gift. This order did not apply to camp inmates or workshop workers as they had already been long under SS rule.

Zuckerkandel returned from Tarnopol in triumph since he had succeeded in having all the certificates he took with him confirmed as valid.

After that, tension and terror subsided for some time – about 2 months – and relative calm seemed to prevail.

In the middle of September, 1942 I was suddenly summoned to Mr. Meyer. On my arrival I found an elegant and handsome officer who introduced himself to me as Capitan Pollinger * from the military town command. Noticing my reserve in the presence of the stranger, Mr. Meyer explained that he was an ardent anti-Nazi and absolutely trustworthy. They told me that only after a severe inner struggle did they decide, in spite of the serious risk they ran, to inform me of the terrible news they had received from the higher Nazi authorities in Lwow; the strictly-kept secret of the imminent and final liquidation of all the Jews. They did not yet have details or the exact date when this was to take place but it would be carried out gradually in the very near future. They had arrived at a conclusion which they suggested to me – that single individuals might perhaps escape their doom by hiding among non-Jews or in some safe hideouts. The only alternative hope lay in a quick victory by the Allies which did not seem to be very near.

[Column 102]

They permitted me to share this distressing news with some of my associates who could be trusted. I passed this “death sentence” on to Dr. Mayblum without, of course, mentioning the names of those who had given me this strictly guarded secret. Dr. Mayblum received the job-like biddings with sad resignation saying that only a miracle could save the Jews. At the next Judenrat meeting he tried to break the news very gently, camouflaging it among other matters under discussion. But those present were not all prepared to believe this hopeless truth and called the others pessimists and panic-stricken cowards who saw everything in black colours.

14. The Second Action

Only a few days after my talk with Meyer and Pollinger, Batish came again to me with the shocking news that the Gestapo had arrested Meyer and transferred him to Lwow. This was the greatest blow that could have befallen us and particularly me. I awaited arrest at any moment. To get some details about Meyer's arrest, I secretly went to his desperate wife who thought that her husband had been arrested because of his friendly attitude towards the Jews and also because of the anti-Nazi convictions which he openly expressed in the presence of his colleagues, some of whom must have denounced him.

After three days of fear and suspense, Mr. Meyer returned and sent for me at once. When I came I found him exhausted, dirty and unshaven. He told me that he had been kept in the Gestapo jail at Lwow for the reasons which his wife had correctly guessed. Thanks to his administrative abilities

[Column 103]

and perhaps even more, thanks to the intervention of some high-ranking personalities, he succeeded in escaping from the Gestapo clutches. He assured me that he did not intend to change his friendly attitude towards the Jews but more caution would be necessary.

After our consultation with Meyer and Pollinger *, Mr. Meyer advised us to keep watchmen at night on the outskirts of town in order not to be surprised by sudden 'surprise' actions. He also promised to keep in touch with us and immediately pass on any information he would get about suspicious movements. It was not easy to place guards at important points of traffic but a way was eventually found. It was done partly by the personnel of the Jewish hospital at the end of the Lwowska Street and the workers at Weintraub's flour mill kept constant watch on the highway leading to Tarnopol.

At the end of October, Mr. Meyer informed us that Pollinger had received news about orders for preparedness given by the higher authorities to all local police, gendarmerie and even units of the military town command.

This might have no connection with the feared action, as such orders had sometimes been given in the past under the pretext of approaching partisans; but in any case, we intensified our watchfulness.

On the night of November 1, 1942, somebody from the Jewish hospital (if I remember rightly it was Hesio Feuering) brought news of a column of military trucks drawn up nearby. Without waiting for any confirmation of this news, the Jews began to hide. People ran crazily

[Column 104]

from place to place to find a shelter. Everyone thought that others had a better one than their own.

This time the blow came from Lwow. On November 1, 1942, a special representative of the SS, Police Führer SS Vöbke descended on the town at the head of a destruction squad called: “Vernichtungs-Kommando”. This time there were no negotiations, no bargaining with the Judenrat. The hangman, experienced in manhunts, set about his work with great efficiency.

This time, people were dragged out of homes and shelters with greater bestiality and cruelty than ever. It was aid that in this action the Lotyshe who took part exceeded all previous executioners in bestiality. They pulled babies out of their cradles before the eyes of their mothers and smashed their heads against the walls.

Again, about 2000 victims went to the slaughter. At the end of the action and in order to crown it with success, Vöbke himself selected a number of Jewish militia men, including the commandant – Dziunek Landesberg – and ordered them to be added to the transport. He wished to do the same with the members of the Judenrat but here he met with opposition from Warzok who telephoned the Police-Führer in Lwow and convinced him that as long as there were still Jews in town and some labour camps in the district, the Judenrat was indispensable. Vöbke gave in only after the order was confirmed from Lwow. As was done after the first 'Action', the Judenrat was called upon to pay a big tribute to cover the expenses of the transport which was loaded as the first one had been and followed the same route – Belzec.

In this, as in the previous action, the scene of events were the streets near and around the Judenrat, particularly the

Compliments of Rose Kissel

[Column 105]

Ormianska Street, the Green Market and the railway station. Vöbke and his “aides” displayed a murderous zest for killing and soon the Jewish streets were littered with corpses. The old and the children, weakened by prolonged hunger were frequently shot on the way to the collecting-point as they could not run fast enough for their oppressors who used their whips generously and mercilessly.

Vöbke himself shot an old woman, Mrs. Sharer, in the street opposite our workshop. Inside the Jewish hospital, he also killed a number of patients who seemed to him unfit for transportation.

On December 1942, Vöbke staged a similar “action” in Przemyslany.

15. The Closing of the Ghetto – Hunger and Epidemics

After the second action, the noose on Zloczow Jewry was gradually tightened. At the end of November 1942, the order to seal the ghetto off completely was carried out.

A few weeks earlier, buildings and walls of the main street had been covered with big posters * showing a life-size Jew with a thick beard and side locks, an enormous hooked nose, dirty, tattered and covered with lice with a text that read as follows: “The Jews are the carriers of typhoid”. (It was the infamous cartoon from “The Sturmer”).

The area allotted for the ghetto consisted barely of a few streets, already overcrowded at the beginning of the German occupation which now concentrated the Jewish population in a “Judenviertel” (Jewish Quarter). The ghetto, reduced to a minimum, was

[Column 106]

enclosed with barbed wire and put under the guard of the Ukrainian militia. It had only two outlets – one in the corner of Mickiewicza Street and Poczlova and the second, at Sokola Street, to link it with the rest of the town. Anybody who dared leave the ghetto without a special permit was liable to be shot on the spot.

Into this hermetically sealed and greatly diminished area were forced 7500 souls – what remained of the Jewish population of Zlozcow and the surrounding townships after two actions. The overcrowding was simply unbearable. In every flat, several families were huddled, 10-15 persons in one room. It sounds unbelievable but people had no place to lay their heads and took turns in snatching a little sleep. The lack of space and of elementary hygienic conditions (soap was a luxury beyond dreams), coupled with widespread hunger, swiftly led to devastating consequences. An epidemic broke out and took a heavy toll on lives.

In these terrible conditions, the situation became very serious, indeed beyond control in spite of the superhuman efforts of the Jewish doctors and the sanitary personnel. The Judenrat spared neither effort nor money in this struggle for life, but in vain. It seemed as though the forces of darkness had joined together to bring the catastrophe nearer and nearer. There was no home without sick or dead. One misfortune after the other befell the worn-out people. And at this point, the German authorities ordered that the Jewish Hospital should be placed at the disposal of the District camp commander. Dr. Hreczanik, then director of the hospital, was asked to remove all the sick that did not belong to the camp without delay. The Judenrat swiftly organized a temporary hospital in the ghetto at Scharer's house in Chodkiewicza Street, but this could not function satisfactorily because of lack of such basic

[Column 107]

requirements as medicine and linen, which could not be had for gold.

In addition, news came of the outbreak of typhoid in the Lackie camp. Everything led us to believe that there was no hope and that the terrible fate of the camp lay before us.

The camp commandants were ordered to liquidate the camp in case of a severe epidemic and to burn everything including the sick and healthy alike. In any case, they were only Jews, of course;

At this moment, one of the camp doctors, Dr. Salomon Yollek who now lives in the United States, 156 Jackson Ave., New York, proved a real guardian angel. Thanks to his presence of mind, courage and heroism which bordered on madness under the prevailing circumstances, a great catastrophe was averted.

In order to give a clear picture of the situation, I have to return to the initial stages of the Lackie camp.

The first doctor of the camp was Dr. Silber, a refugee from western Poland who, with all his goodwill and the best of intentions, could not cope with the prevailing difficulties. During his term of office, the sick room of the camp hardly functioned. The sick and the injured in work accidents (there were many in the quarries) did not come there for treatment as they feared to be shot, in accordance with Nazi practice. After Dr. Silber's death (he contracted typhoid in the camp) Warzok requested the Judenrat to appoint a new doctor immediately. Here, a difficulty arose. Nobody wanted to take such a post which exposed the holder to the permanent danger of death at the hands of some Nazi brute. After various negotiations and a long search for a doctor without any family, the Judenrat required Dr. Yollek to take this position. Though Dr. Yollek had a wife and child and,

[Column 108]

had the right to refuse the job which was equal to walking into the lion's jaws, he volunteered for it readily as he felt it is duty and mission to help his fellow Jew. In spite of his family's strong protest, he stuck to his decision.

Before going to the Lackie camp he first demanded that the Judenrat should supply him with medicine and equipment which would enable him to work efficiently. With the help of Dr. Hollenderski, he set out to organize a proper dispensary which would meet the urgent needs of the camp inmates.

He worked with such devotion, zeal and dignified authority that even the Nazi brutes, including Warzok, could not help but admire him.

First of all, the practice of shooting the sick stopped. Dr. Yollek succeeded in transferring some patients to the hospital in Zloczow from where they freed themselves completely from the camp. When things settled down and it seemed that in this field at least conditions had improved and had become routine, a terrific epidemic of typhoid erupted in the Lackie camp. It began during Warzok's absence while he was on leave. The sick-room was full to overflowing and Dr. Yollek was under terrific pressure. What's more, he realized that the position might soon become tragic and without a second thought, he decided to save the camp no matter what befell.

The deputy commandant, SS Salzborn had made all preparations to carry out standing orders for such cases, namely – to burn the camp. He waited only for Warzok's return. He had already sent notice to the Judenrat to bring a few barrels of kerosene for the purpose. Dr. Yollek arrived with this cart and told the members of the Judenrat the situation and what was about to happen. He assured them at the same time,

[Column 109]

that he was ready to fight to the bitter end, but under the sole condition of receiving support and help, particularly with medicines. He had worked out a plan for convincing Warzok that the epidemic was not typhoid but the flu and chicken-pox. After receiving a promise of unconditional support from the Judenrat, he went back to Lackie where, in the meantime, Warzok had returned. Much courage was needed to put such a proposal to the Nazi hangman who could have shot him at will on the spot. Dr. Hollenderski (Dr. Yollek's colleague) offered to be the first to face Warzok and report on the latest events in the camp. He volunteered to bear the brunt of this encounter with Warzok in order to spare Dr. Yollek, but the latter refused and risking his head, went to Warzok who had already been informed about everything by his subordinates.

Warzok, as was to be expected, was infuriated and received Dr. Yollek with insults and curses. He declared his intention of burning the whole camp including the sick and the healthy, with the addition of the doctors and some of the Judenrat members. But Dr. Yollek, never losing his nerves, insisted convincingly that it was all a false alarm. He guaranteed by his own head that this was only a severe influenza which could easily be overcome with a little effort and good-will. Dr. Yollek knew well that there was no use in appealing to Warzok's humanitarian feelings for he had none, and decided, therefore, to strike a different note in order to save the camp from being turned to ashes. He tried to stress that during Warzok's absence, his subordinates had lost their heads because they lacked his own experience and resolution.

Warzok, as a practical and shrewd businessman, calculated that the destruction of the camp would lead to the loss of a high and lucrative office and expose him to the danger

[Column 110]

of being sent to the front, as had already happened to many other camp commandants. He, therefore, gradually softened and allowed himself to be persuaded by Dr. Yollek's arguments until he finally gave up the idea of burning the camp. To be on the safe side, he requested Dr. Yollek to produce a written statement, signed by two doctors, that the epidemic was not typhoid. Moreover, he ordered Dr. Yollek to have all the sick appear in the square for a roll-call. It was a great 'test' and an unbelievable sight: the victims of typhoid, shivering with high fever, barefoot and in underclothes, formed in rows – the stronger ones in front, of course. Warzok, at a safe distance, stood in front of them and shouted: “what is wrong with you?” (Was ist los mit euch?) To which he received a collecting answer: “Nothing serious, Herr Hauptsturmführer”. Warzok was only too keen not to prolong this macabre spectacle, and ordered the sick to be sent to the hospital in Zloczow *

So the first part of the battle was won by Dr. Yollek but there was still a long way to go. First of all, Dr. Yollek had to suppress the epidemic and prevent it from spreading. This was a life or death struggle. In the end, life triumphed. But was it life? Or an adjourned death sentence?

The next step was to obtain medicines and disinfectants and in sufficient quantities. For that, the Judenrat did its utmost but with poor results as it was next to impossible to secure medical stores for Jews. Here the Jewish pharmacist, Berish Lifschütz, Kaczek and Salitra proved a great help. As employees in pharmacies, they had access to medicines which they supplied legally or

*Dr. Hreczanik received from the director of the Municipal Hospital, Dr. Martynowicz, a fine and noble Pole, 100 beds to enlarge the Jewish hospital.

[Column 111]

Illegally, sometimes even stealing them in order to relieve the community. But all this was far from enough. Here too our guardian angel, Mr. Meyer, saved us as he had done so many times already *.

Dr. Yollek, for his part, toiled day and night to the verge of collapse. It was a fight against bitter odds. He had to bring medical help to people in the ghetto as well as the camp. He himself had to do all the disinfection and take steps to keep the epidemic from spreading among the weary and the starved. After his work in the camp, he would go from house-to-house, in the ghetto. Often, touched by the misery there, he would not only forego his fee but would leave some medicine or a little money to buy bread for starving children. He was loved and adored by everyone and well deserved the name of: “The Angel of the Ghetto”. Dr. Yollek's activities in that sorrowful period have indeed printed his name in letters of gold in the history of Zloczow Jewry.

16. The Epidemic Subsides

Yet, were it not for Mr. Meyer, all these individual efforts as well as those of Dr. Martynowicz and the Jewish doctors, would not have brought the epidemic under control. Medicines could not be obtained only in exchange for alcohol which, being a rare and precious commodity during a war was absolutely out of the reach of the Jews. No money could buy it.

In this hopeless situation, an unexpected event occurred. Warzok had given his magnanimous permission to transfer the sick

*Details of this effort of Mr. Meyer and his intervention are given elsewhere in this narrative.

[Column 112]

From the camp to the hospital and now wished to safeguard himself against possible informers, so he made frantic efforts to please his superiors. He did it in two ways: One, the most acceptable, was by sending valuable presents to high SS officers, these being jewels supplied, of course, by the Judenrat, who also had to supply an expensive car for Warzok himself. To please all who might be concerned, he had the idea of sending drinks and gifts for wounded SS men to one of the military hospitals. He decided on a home-made Eiercognac (egg-brandy) and began seeking an expert in making this speciality. He ordered Zuckerkandel to find one and also turned to me, thinking that I might have a recipe from my late father-in-law. He then approached Mr. Meyer for several hundred litres of alcohol, sugar and eggs, all needed for the preparation of this commodity, and this gave our good friend Meyer an opportunity of diverting some of the precious alcohol to the Jewish hospital. In this round-about way, the spirit destined for the egg cognac turned into medicines for the sick and helped to suppress the epidemic, which by then, had taken a toll of several hundred victims. Paradoxically as it sounds, the survivors envied those who had died and were decently buried; and in the Jewish quarter a new saying was coined: “Today W or Y died a luxurious death”.

Yet, even this luxury was not to last long for very soon, the dead were given no respite either. By order of the Nazi authorities, Jewish cemeteries were devastated. The marble tombstones were sent to Germany while ordinary stones were broken up by the Jewish slave labourers for use in roadmaking. By accident or miracle, the barbarians did not disturb the tomb mausoleum of the revered and saintly Rabbi Mechele of Zloczow.

[Column 113]

17. In Search of Rescue.

The shattering defeat of the German armies on all fronts during the years 1942-43 – Stalingrad in Russia and the defeat of Rommel's Africa Corps – together with the heavy bombardment of German cities did not in the least slow down the crimes of Hitler and his helpers. On the contrary, it led to the speeding up of their mad destruction, murder and loot as the idea crystallized in their sick minds that the fear of revenge for the atrocities perpetrated would prevent the Germans from capitulating. Needless to say, the first and main object of this fury and hatred remained the Jews. “The Final Solution” entered its last stages. The “Holy Task” begun by Heydrich was taken over by Ernst Kaltenbrunner who tried to outdo his predecessor in brutality.

Although the victorious offensive of the Allies raised some faint hopes in the hearts of the doomed, the slow progress made salvation look like a remote dream that was far from realisation. People began to think in different terms. Time was against them and they tried to find some immediate, practical ways of survival, a last straw to grasp at.

First of all, fair and tall people with “good looks” whose features could not be classified as Semitic began to make us of these attributes and tried to prove their “Aryan” origin with false birth, baptismal or marriage certificates. Again, there began a flourishing trade in these Christian certificates. This was carried on by Poles, some genuinely wishing to help, some heartless crooks who demanded exorbitant prices for a scrap of paper. There were many priests who provided Jews with original birth certificates in the names of persons long dead. The quest for an Aryan document was only the first step. The next acquisition had

[Column 114]

to be a so-called “Kennkarte” – a German identity card, the possession of which enabled one to find a “protector” who would arrange to transfer the “new-hatched Aryan” to a distant town where he was unknown and could hope to move about unsuspected. The larger the town, the safer. Yet, on the other hand, the more difficult it was to find food and accommodation. These “lucky Aryans” did not have an easy time. Very few of them survived their initial success. Many were recognized by Poles and Ukrainians; the dregs of society called “Schmalzowniks” *, who blackmailed their victims and extorted their last penny only to hand them over in the end to the Gestapo. A very few managed to escape these informers by changing their addresses quickly enough.

The more common and simpler way of hiding was, of course, to find a shelter, called a “bunker”. People who still had a little money or some valuables left and knew a reliable Pole or Ukrainian, tried to persuade him to build a little hideout. To find an acquaintance willing to engage in such an enterprise was more than difficult and to survive in such a bunker was a veritable miracle. Hiding or feeding a Jew was forbidden under penalty of death and who would risk one's life to save a Jew? The German even promised cash prizes and the property of the person denounced to those who handed over hiding Jews. In light of these circumstances, deep gratitude and great credit should be given to those noble Christians who, no matter what their motives may have been, took it upon themselves to hide Jews and persevered till the end. Not only the survivors, but the whole Jewish people are indebted to those heroes,

[Column 115]

to those great-hearted, individuals, many of them Germans like Mr. Meyer who risked their lives to help their down-trodden, outlawed and hunted fellow-beings. The warmth of their hearts, their nobility and mercy nourished within us a tiny flicker of faith that evil would not ultimately triumph.

It is interesting to note that most of those saviours belonged to the Polish upper class, to the intelligentsia and the peasant proletariat. This middle class was absolutely indifferent.

There were many cases of criminal luring of victims into a bunker and then handing them over to the Nazi after having deprived them of all of their belongings and sometimes even killing them. Money was not a decisive factor in finding safety. The opposite was often the case; many perished because of it, falling victims to human greed. In this way died: a) Dr. Sane Kahane with all his family (eight persons handed over to the Germans by a peasant who hid them for money); b- the dentist Zwerdling and his wife, killed by the bailiff of the village Kozaki; and many others.

Children were frequently renounced by desperate parents who, in the face of total destruction, tried to save at least one of their children. Using entreaties, presents and promises of rewards, they implored Polish families to “adopt” a girl. Those willing were afraid of their neighbours who immediately sensed such a feminine addition in a family. There was also a great difficulty in such a change-over which called for the prolonged training of the children who had to learn prayers, go to church, absolutely deny their Jewish origins, etc. A great number of such unfortunate children were caught by the Germans thanks to informers. I know of a few cases of survival. A number of children entrusted to convents were baptized and remained as Christians. I also know of a

[Column 116]

man, Kruth, who found refuge in the house of the Rev. Dzieduszycki and embraced the Catholic faith together with his whole family.

I wish to stress here that in Zloczow as elsewhere, there were many courageous and reckless people who had been brooding over the idea of obtaining arms and fighting their way to the forest. They dreamt of facing the mortal enemy and selling their lives dearly. But this remained mostly an unfulfilled dream in the face of terrific odds. This is not the place to engage in polemics or to defend those accused of cowardice because they allowed themselves to be led like sheep to the slaughter. To those hero-critics who never came anywhere near the horrors of neither war nor Hitler's hell for the Jews, I can only say that they are using empty arguments which are not worth answering. If the Jews of Europe had the slightest possibility of organizing themselves for self-defence – which is the first reaction of everything living creature, human or animal – the Nazi Moloch would not have claimed six million Jewish victims and our history would be full of the deeds of heroes whose names would belong to eternity.

A single glance at the geographical and ethnic conditions of Eastern Poland explains the tragic helplessness of the Jews there.

As in all occupied countries and at all times, there was a fighting underground under the German occupation. Its success depended not only on the bravery of its members but also on the flow of supplies – of arms and food. The success of guerrillas depends largely on the friendly milieu in which they move and on the cooperation of the local population. Eastern Poland, which the Nazi in their cunning chose as the “Cemetery of European Jewry”, was the most suitable place for this because of its favourable conditions. In those parts of the country

[Column 117]

inhabited only by Poles, the leftist underground helped to supply the Jewish fighters with arms.

The rightist Polish underground organization, the so-called N.S.Z. (National Armed Forces), openly helped the Germans in mopping up and wiping out Jewish fighters and murdering Jews wherever they could. In Eastern Galicia, predominantly inhabited by Ukrainians who from the outset of the war were the most ardent collaborators of the Nazi, any Jewish underground was absolutely doomed. The loitering bands of Banderists and Wlassovists – aspirants to an Independent Ukrainian State – fought the Poles but even more the Jews whom they mercilessly liquidated.

To support my statements, I shall give a few incidents known to me:

The rural population was mostly Ukrainian. At its best it was passive and did not

[Column 118]

help the Jews hiding in the forests. More often than not, they handed them over to the German executioners.

Understanding and insight into the specific conditions prevailing in Poland are needed. Any charge of cowardice is a vicious slander and an insult to the sacred memory of those who died the death of martyrs.

18. Strassler's Bunker.

Our camp-workshop at Strassler's was an exclusive outpost inside the Ghetto. There work went on at a very swift pace in producing the potato ad-mixture for bread and the egg cognac for Warzok. We worked feverishly, in constant tension and fear of Warzok, master of our lives, who threatened us with the most savage punishments should anything go wrong or any poison be found in the liquor.

Realizing that such a luxury as egg cognac might attract certain German officials, he forbade us to admit anybody into the workshop. This beneficial isolation was a boon. It enabled us to start working on a long-conceived plan to build a shelter which could offer safety during an action and perhaps help us to survive the war.

The initiators of this quite elaborate plan were the three Strassler brothers, Wilo Freiman and I. After again examining the plan and the possibilities of carrying it out, we set out to work, each of us with his own individual hopes and prospects. All the men and several women took part.

In the later stages of the work, after the liquidation of the Zloczow ghetto, two professional craftsmen joined our crew. These were Steinhauer and Rosen, who came to us from another outpost and were to play a sad part later in the tragic death of Wilo Freiman in the bunker.

[Column 119]

It is worth while giving a few details about this bunker which was a unique construction used for a unique propose to live in hiding under the surface of the earth. Thanks to it, twenty four people escaped the jaws of certain death and lived to see the liberation.

The building was planned to be executed in three stages:

Having decided on the place, our next problem was to secure the necessary building materials and tools as well as suitable professionals who would be reliable enough to carry out the work in absolute secrecy and under strict precautions.

First the cellars were walled up by Shyo Freiman, Wilo's brother. In one of the ground-floor storerooms above a walled-up cellar, an opening was then made in the corner to serve as a new entrance. In order to camouflage it, a big iron frame was constructed with a normal oven attached which could easily slide away. In an emergency, this entrance could be used and bolted from the inside with strong hooks.

After this beginning, the next step was

[Column 120]

to dig a hundred-meter long tunnel, two metres in diameter. This was a gigantic task for the disposal of such enormous amounts of earth was a formidable difficulty. The tunnel was dug in the form of a horizontal shaft and the earth was pushed into the sealed-off cellars.

At the beginning, work progressed very slowly and clumsily because of misunderstanding between the participants and financial obstacles. These were gradually overcome thanks largely to the will and energy of Wilo Freiman who knew how to inspire others with his courage and enthusiasm. The building was finished in time as scheduled.

19. The Liquidation of the Ghetto.

The ghettoes were slowly perishing. The Jews were behind walls and barbed wire under guard day and night, writhing in agony and despair. Although they knew what was to come, they waited for a miracle, clinging to the slightest ray of hope.

Conditions in Zloczow were not different from any other place. The five cold winter months after the last 'action' were terrible and there was no day without some sad event.

People, or rather shadows of people, lost their heads in their daily struggle to get a little bread and fuel for their freezing children who were swollen with hunger.

Risking their lives for a little food, they would leave the ghetto to search for it, only to be caught by the lurking Ukrainian police and handed over to the “Kripo” who shot them mercilessly on the spot.

Another calamity was the frequent visits of various German officials, either on duty or in their own private capacities, who raided Jewish homes for fun. For some time, poster reading “Beware, Typhoid here!” kept those

[Column 121]

visitors away, but after a while, this warning ceased to work. Particularly dreaded were the visits of the infamous gendarmes Mury, Hirsakorn, Zwillinger and Radke, who often used to drop into Jewish homes to torture people, mostly women and children. One day, these four creatures while drunk, broke into a flat, attracted by the moans of a woman – a certain Mrs. Gutfreund – and a child's whimpering. They found a woman that was ill, unconscious and with high fever. They stripped her naked and poured buckets of cold water over her, yelling as they roared with laughter that this shower would bring her fever down. They did the same to another woman, Mrs. Speiser.

Besides these individual tragedies, there were cases of a more general character which nearly brought disaster on the whole community.

One morning, a red flag appeared on the roof of the synagogue * - obviously an act of provocation by some unknown mischief maker. The Gestapo promptly arrested the executive of the Judenrat and a number of people residing in the neighbourhood. Mr. Treiber, the German using the premises, courageously explained and proved that the roof could be reached only by a person in possession of the keys which were in the hands of the exclusively Ukrainian personnel. Next day, one of them disappeared with the keys. Suspicion was diverted from the Jews and the incident ended without any loss of Jewish life.

Soon after, another incident happened which might also have had tragic consequences. A young boy, Siunio Freimann, Shyyo's son, left the ghetto and joined a group of shady partisans who, as rumours

[Column 122]

had it, were ordinary bandits. One night, an armed gang raided the homes of the Judenrat members and robbed them of cash and valuables and threatened to kill them if they reported it to the German authorities. The Gestapo came to know from another source and the Gestapo chief arrested the Judenrat accusing them of paying voluntary contributions to partisans and encouraging them to attack German outposts; proof of this being the participation of a local Jew in the raid. Zuckerkandel's intervention at the Gestapo Head Office in Tarnopol, supported as usual with an expensive present for its chief, put an end to this affair.

Another shock was caused by a so-called “parcel affair” in the Lackie camp. As mentioned before, the Relief Committee sent food parcels to the inmates regardless of the parcels sent to them by their families. Once, the late Leon Blaustein brought a batch of parcels from both sources to the camp. In Warzok's absences, his deputy Salzborn examined the parcels very carefully and found a small kitchen or pocket knife in one of the parcels. He immediately ordered the addressee to be shot and Blaustein to be detained in the camp after a severe flogging. He also threatened the Judenrat with reprisals for smuggling arms into the camp. This time, Zuckerkandel succeeded in pacifying Warzok and the matter was dropped.

These and similar events were the only distractions of the miserable Jewish existence until the day of the final destruction.

A few lucky “divers” managed to dive into nowhere and find shelter with Polish friends or left for the unknown with Aryan papers. The unlucky remainders pinned their hopes on the increasing victories of the Allies on the war fronts.

One of the signs indicating the impending catastrophe was the extensive digging of ditches by Russian prisoners of war near the

[Column 123]

village of Jelechowice. When the news of the mysterious diggings was brought by peasants to the town, people, still optimists, thought that they were army trenches and thus a good omen of the approaching Front and subsequent deliverance. Very soon, they were to find that those supposed trenches were their own future graves.

At about midnight on April 1, 1943, the ghetto plunged into complete darkness was surrounded by a double cordon of special murder units called “Mordscommando” brought from Lwow and Tarnopol for that purpose. They were followed by auxiliary “gendarmerie”, military police, “Orpo” and the Ukrainian militia of the entire district. The head of this large-scale slaughter was Hauptsturmführer Engels, a deputy for Jewish affairs in the S.S. Police, under General Katzman, Warzok, Lex *, Ludwig and Füg, all of the same rank, assisted Engels in his task.

Early that morning, leading ferocious and specially trained dogs, the murderers entered the ghetto and swiftly advanced through all streets simultaneously. Breaking into houses, they dragged everyone out and drove them forcibly to the “traditional” meeting place – the Green Market. This time the first to be brought were the members of the Judenrat and the Jewish Militia with their families. These were ordered to line up and place whatever money and valuables they had in baskets prepared for the purpose. Engels came up to the Judenrat members who stood in a row under the walls of Nussen's house and asked Dr. Mayblum to sign a statement that the ghetto had been

[Column 124]

liquidated because of an epidemic of typhoid. When he refused, the infuriated Engels began to be-labour him and finished him off on the spot. The same happened to Dr. Schotz and Jakier who also refused to sign. Then Engels unleashed his fury on a standing woman nearby who carried a baby in her arms. He seized the baby by its little feet and smashed its head against the wall. The unhappy mother, mad with shock and sorrow threw herself at Engels but was killed with a shot by Ludwig.

Meantime, more and more victims were brought. In the rainy and snowy weather of that April day, hundreds of people stood cold and wet, numbed and bewildered. No screams or cries were heard in this desperate crowd, resigned to their fate – only the whimpering of small children hugging their mothers. Everyone felt that their end had come. When the market was full and the three chiefs of the “Action” – Engels, Warzok and Ludwig – inspected the lines, a few bold optimists: Brown, Weinstock and Salitre, still hoping for salvation at the last moment, stepped out of line to plead for mercy. Brown, the dentist asked Warzok to spare him because of his devoted service which he was ready to continue. Warzok lashed him in the face with his whip shouting: “you cursed Jew; you won't touch German teeth anymore!” Salitre, the pharmacist reminded Ludwig that he had been an officer in World War I. Ludwig did not answer but released his Alsatian dog which bit him through the throat. The same happened to Munek Weinstock.

Many of the camp and workshop inmates who still had a lease of life came to the ghetto that tragic night and were also rounded up. A few were saved, without their families, by one decent German businessman – Shweiger by name – who courageously insisted on having his Jewish workers

[Column 125]

Back in his firm and pulled them out one by one from the death row promising them to save their families later. Of course his promise remained unfulfilled but the eight people whom he rescued survived the occupation. The late Bunio Rosen did not take advantage of this chance of survival as he refused to part with his wife and baby and perished with the others. Shweiger also intervened with Warzok and Ludwig and saved a few more people. One was Josio Tauber who, in the confusion, dragged two non-inmates with him. The Nazi refused to save Tauber's wife who served in Warzok's house as a servant.

20. Jelechowice – A New Jewish Cemetery.

This time the murderers did not bother to send their victims to a distant spot like Belzec. The Jelechowice woods, a place for Sunday outings and picnics, were destined to be their last resting place.

Military trucks drove up to the Market and each loaded up 40-50 people. Under strong guard, the ghetto dwellers made their last journey straight to their mass-graves in Jelechowice. Naked men, women and children were pushed into the ditches and machine-gunned. One transport followed the other; dead, half-dead and wounded filled the graves, layer by layer. Blood spurted and stained Nazi uniforms and faces, but Nazi heart and hands did not tremble nor stop their hellish work. The massacre went on for two days claiming some 6,000 souls. The hopeless agony and three-year old struggle of the Zloczow Ghetto came to an end in Jelechowice.

Two women escaped this slaughter by running into the woods under the hail of bullets. One – Leah Frankel – was hidden by peasants. The second, a young girl named Czortkower, disappeared without a trace.

[Column 126]

The truck hearses brought their loads to their destination and returned to the camp workshops with the clothes of the slaughtered which were first carefully searched by SS men for sewn-in valuables and were then passed on to be sorted by the inmates who often recognized the clothes of their near ones.

To hide their crimes, the Nazi covered and levelled the mass graves and ordered the neighbouring villages to plant trees over them. But this disguise did not succeed. According to reports from the peasants, the earth, soaked in blood, fermented and moved and rose in unyielding mounds for over six months.

21. The Last Manhunts.

While the ghetto was gradually perishing, the few Jews left in the labour camps were helpless and heartbroken onlookers. Some deserted to their families in the ghetto to join them in their death-march. Many committed suicide in despair. A very few let their comrades persuade them not to take this desperate step.

After the two days of slaughter, the Murder Commando left Zloczow entrusting the mopping up to the local gendarmerie and the German Auxiliary Police, the ORPO. The new Kreishauptmann Dr. Wendt, Captain Schwarz and Captain Füg took great pains to execute their task with real German precision. I wish to emphasize here that the Commandant of the ORPO, Lieutenant Oberst, flatly refused to participate in the liquidation of the ghetto. He was arrested and immediately sent to the Front*

[Column 127]

For a couple of weeks there was an additional hunt for people who had managed to find a shelter of sorts. Some, forced by hunger, came out of their hiding places, others were detected by the trained dogs of the gendarmes. The notorious Hirsakorn loitered day and night in the dead town.

All the actions took place under our very eyes as our workshop, unlike the others, was not outside the ghetto but in its very heart near the Green Market. Under strict orders, our gates were shut and locked and had a big, protective sign-post marked “camp workshop”. More than about ourselves, we were concerned for our dear ones who were with us but had no right to live after the liquidation of the ghetto. We placed the old people, the children and adults who had no 'camp certificates' in the bunker. There were the aged mothers of Freiman and Lonek Zwerdling, old Strassler and his wife, my wife and son, Rozka Lerner and son, Josio Strassler's wife with a new-born baby and a few others. Our situation grew more precarious each day. After the liquidation of the ghetto, some escapee knocked at our gates almost every night. Some even came crawling over the rooftops. What were we to do? On the one hand it was dangerous to take in these unfortunate wrecks; on the other, refusal meant pushing them straight into the arms of death. In spite of the danger, we decided to take them in and keep them in the bunker with our families. A few survivors had good hiding places of their own but they visited us at night for food and news. Fed and provided with whatever we could spare, they then returned to the nearby forest in Woroniaki.

The nightly visits and contacts were possible because our outpost was guarded by a Jewish Militia man, Ephraim Prager. We felt that this favourable state of affairs

[Column 128]

would not last long. The change came very soon and from an unexpected source.

Hirsakorn, that human hyena in the form of a gendarme who was constantly hanging around in the deserted ghetto, found a woman named Leider. He promised to let her live in exchange for information about hiding Jews. We do not know whether she knew about our bunker or whether there were rumours or whether sheer chance brought Hirsakorn to us.

On the evening of the 12th April, Kirsakorn accompanied by the woman and his Alsatian dog which was trained in sniffing out humans, broke into our workshop and called on us to hand over immediately the persons illegally hidden by us. On hearing our denial of this accusation, he ordered us to face the wall and set out on his search, luckily beginning with the upper floor. While we stood shocked at this sudden dangerous turn of our situation, Wilo Freiman reminded me that according to the rules, access to our workshop required the permission of the camp commandant, Warzok, in this case. In a split second, we decided to act and ran to Warzok as though our very lives were at stake; the dog might detect the bunker at any minute, smelling the people there. We knew that Warzok was at a party given for the personnel of the German firm “Radebeule”. On arriving there breathless, we asked Dr. Glanz's brother-in-law, who was serving, to let us in to see Warzok. Dead scared of the Nazi, he would not listen to our appeal. Luckily Warzok heard our argument and his name being mentioned and came to the door in the company of his mistress. Standing to attention, I reported Hirsakorn's intrusion. Warzok, probably wishing to show off before his lady, telephoned the Gendarme commandant and requested him to recall the gendarme. He also rang up his own

[Column 129]

staff asking one of the officers to take a few SS men, go to the place and expel Hirsakorn. He told us to go back and promised to follow soon. Covered with cold sweat for fear of arriving too late, we reached “home”. Hirsakorn had not yet reached the cellars. Almost at the same time, a car drove up to our gates with Warzok's people. A little while later, Warzok himself arrived.

When he saw the gendarme and his dog, Warzok, furious and most probably tipsy, disregarded our presence, lashed at Hirsakorn with his whip and without listening to his explanations, ordered him to clear out. Then he turned to us and said: “woe to you if there is anybody here besides the legitimate crew!” Then he left hurriedly with his men, issuing a new order that besides the Jewish militia man, a Ukrainian militia man should be placed on guard. What a relief this miraculous end was! This was the first time I saw a flicker of humanity in Warzok. We were all convinced that he knew quite well that we had hidden for he asked where Old Mother Strassler was and left without waiting for an answer.

The indescribable slaughter can be imagined by the effect it had on one of the professionally-trained Nazi murderers as illustrated by the following event.

One day, the above-mentioned Gendarme Muri knocked at the gates of our workshop. When he was told that admission to our outpost was strictly forbidden except with a special permit from the camp commandant, he begged and begged to be admitted and given a drink which he needed very much. Seeing him pale and in a queer state, we did not wish to irritate him but opened the door. After drinking, Muri covered his face with his hands and cried hysterically: “I can't bear it any longer! I have enough of this slaughter and mass-blood bath! What

[Column 130]

Do they want of us these superiors of ours the Kreishauptmann and Captain Fueg?”

We were greatly relieved when he left us. We were not surprised to hear later that Muri had had a severe nervous breakdown and had been transferred.

The new Ukrainian guard kept troublesome intruders like Hirsakorn and Muri away but at the same time, he made it hard for us to keep in contact with the bunker. We had to use all kinds of ruses and tricks to get him away from the chimneys and openings which were our life-lines. In the remotest room we treated him to the best food and drink, often until he was drunk.

The happy end of this first intrusion made us unhappy and concerned our future as to other possible informers and the Gestapo itself. We decided to act quickly in every possible was so as to safeguard our position. First, we tried to get some camp certificates the holders of which could leave the bunker. Others, who had relatives in some still existing ghettoes begged to be sent there or to some hiding places they had known about before the liquidation, but had not had time to use. With money and effort which we did not spare, we finally found a reliable Polish driver, Tadeusz Skorny* who risked his life to save them.

One night, Skorny, who was an employee of a big German building firm, drove up with his big truck, took all those concerned and brought them to safely to their destination. We later came to know that he did it for purely humanitarian reasons as most of the money we gave him as a reward for his dangerous enterprise was used to bribe the German guard.

*Mr. Skorny at present lives in Cracow, Poland with his Jewish wife who is the daughter of my acquaintance, Fechter of Przemyslany.

[Column 131]

For some time we kept the two aged and ailing mothers, W. Freiman and L. Zwerdling in a little cell in barrels covered with potatoes. Later on their sons transferred them to the Jewish hospital where they found a merciful death by poison and were saved from the savage brutality of the SS men. Josio Strassler and his wife decided on a similar merciful death for their new-born baby. The incessant crying of the infant, who was hopelessly ill with a double pneumonia, was a continuous threat to us all. A dose of morphine put it to sleep forever. Rozka Lerner's son Jurek was kept alone in the garret during the day and only at night was he taken to the room by his mother. The little boy of Nacio Feigenbaum, who was Warzok's driver, was hidden all day long in a box.

22. The Unsuccessful Revolt.

After the liquidation of the ghetto, only the handful of Jews employed in workshops and other German outposts remained alive. They were, of course, assured of their right to live and even survive the war, provided they worked hard and did not attempt any sabotage or opposition. Nobody believed these assurances. Whoever could, attempted to escape. Before the sealing of the ghetto, single youths and small groups tried to flee to the forests with arms. One of them, as I mentioned before, was Shyo Freimann who first joined a band of gangsters but soon left them and together with the painter, Nachumowicz, a camp worker, formed a group of some 30 people who were equipped with small arms and determined to fight in the forests. As they had no contact with any serious guerrilla force and no means of existence except looting raids on the local population, they did not have the slightest chance of success. They lived in

[Column 132]

two bunkers. One of them was accidentally discovered by a passing peasant whom they spared although Freimann advised that they should kill him so as to escape betrayal. Though the peasant swore by God that he was a friend of the Jews, he soon set the Germans on their track. They were all caught and shot by an expedition of the SS and the gendarmes. The second bunker with more people was deeper in the forest where the “brave” Germans did not venture. Instead, Warzok who headed that expedition, left sheets of paper on the trees calling on Nachumowicz to return to the camp and promising him safety. Nachumowicz responded to the call and returned to the workshop. Warzok kept his promise. When the time finally came to liquidate the camps too, Nachumowicz was sent with others to the Janowski Camp to find his death there. The other Jewish “partisans” were brutally murdered by various ravaging bands.

Of a more serious character was an uprising planned by two engineers; Hillel Safran and Bialostocki, a refugee from Warsaw, both employees of the German road-building firm 'Radebeule'. They planned to organize a big resistance group of young people who would fight to the last man. They tried to contact the Polish guerrilla in order to get arms from them and fight side-by-side with them but most Polish guerrilla were rightists and did not want to have Jews so they organized themselves separately under a five-man leadership with the two engineers at their head. The first step was to secure arms which could then be obtained in two ways: either by a lot of money or by stealing.

A certain amount of arms were bought from a reliable Pole at a very high price. The bulk had to be smuggled in very risky and dangerous ways. A few, who were working in the one-time arsenal of the artillery,

[Column 133]

Sorting out old arms and ammunition left by the Russians, were drawn into the conspiracy and ordered to steal suitable arms, hand grenades in particular. These stores of arms, useless to the Germans, were not rigidly guarded. The stolen articles were taken out and buried in the nearest forest. Now the most difficult part was to bring the precious consignment to its destination.

There was nobody bold enough to do it so Engineer Hillel Safran volunteered. As a trusted worker of 'Radebeule' which was situated behind the cemetery not far from the place where the arms were concealed, he managed to transfer some arms each day in his briefcase among papers and documents and deposited them in affixed place – the worker's cloakroom in one of the firm's blocks. Thus, while preparing his escape, he carried out this most dangerous duty, day in and day out.

Meantime, the wiping out of the Nachumowicz group discouraged and disheartened many of the conspirators so Safran and Bialostocki decided to hasten the flight. According to all preparations and careful calculations, success seemed to be assured but things took a very different turn.

In spite of the secrecy and precaution, there had been somebody spying on the planners who betrayed the five leaders on the eve of their enterprise. The informer was a boy from Lwow, the converted offspring of mixed marriage named Lewandowski. The five leaders were arrested and kept in the building of the Kripo which tried beating and inhuman torture in order to extract the names of their associates and the hiding place of the arms. Not one of the five betrayed their comrades. There were rumours that help was organized for them and escape offered but the Police quarters were so centrally situated – on the “Stare

[Column 134]

Waly” – that success was out of the question.

Zuckerkandel took up the matter and pleaded with Ludwig, the Gestapo head. But he was just fooling himself and those concerned as the doomed men best served the Germans as an intimidating example. They were all shot publicly in the Green Market Square.

From the balcony of our workshop we saw the late Hillel Safran, dignified in his calm, being led to the place of execution. When he was thrust against the wall by an SS, he threw himself on him trying to wrest the gun from him. But the Ukrainian militia man fired and he fell shouting: “death to the Nazi murderers”.

Such was the sad end of a heroic attempt on the part of Zloczow youth. Blessed be their memory!

23. The Changing of the Guard.

In spite of the victorious advance of the Soviet armies which were coming nearer and nearer, our nervous tension grew steadily together with our fear of the impending speed-up in the liquidation of the Jewish remnants. We felt that death was nearer than the dawn of liberation. The will to survive seemed stronger in us than ever before.

In spite of difficulties and squabbles, the work of improving our bunker made great progress. Nevertheless, I decided to leave and seek my own way to safety. I could, of course, count on my good friend Mr. Meyer, but as luck had it, a new source of help arrived unexpectedly as a reward for saving one worker, Wladyslaw Kulpa from being exiled to Siberia during the Russian occupation in 1940. In May 1943, this man – a small farmer in Jelechowice – came to me and told

[Column 135]