|

|

|

[Page 162]

The Mass Exodus of Polish Jews

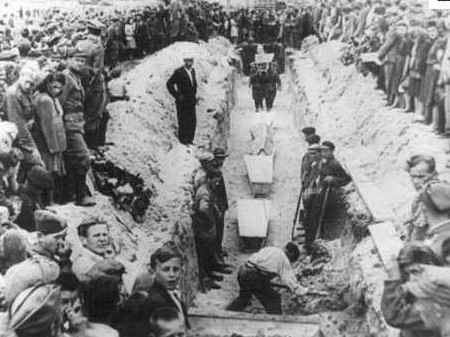

The Zionist homes and the AJRC homes worked with the “Aliyat Hanoar ” or youth immigration department in Palestine, a department of the Jewish Agency of Palestine. This office organized the children transports that left Poland legally and illegally. Children were assembled in small groups and sent with the “Brichah” or escape movement through Czechoslovakia to the German and Austrian D.P. camps or France where they joined Zionist homes. The Polish homes also sent children with families that were leaving Poland. The arrangements were cumbersome and time consuming while the Jewish situation in Poland was getting worse by the day. Anti–Semitism spread like wild fire across the country. Anti–Jewish acts were common as were pogroms. The height of the hysteria took place in the city of Kielce where a Polish mob attacked Jewish inhabitants on July 4, 1946 [1]. Forty–two Jewish Shoah survivors were killed and over 40 injured. Polish police units joined the pogrom. Special forces had to be sent to restore order in the city of Kielce.

|

|

| The burial of the Jewish victims following the Kielce pogrom. |

Fear seized the Jews of Poland. The fact that Polish security forces actively participated in the pogrom gave the Jews no hope. The Polish government already had a reputation among non–Jews of being dominated by Jewish interests and did not want to encourage this idea by interfering on behalf of the Jewish community. The government was also fighting for survival as the country approached a state of anarchy.

Even before the Kielce pogrom, Jews started to leave the war ravaged country. This trickle became a flood following the Kielce pogrom where Jews were accused of making matzoth with Christian blood. Jewish institutions in Poland introduced strict security measures. According to David Danieli, security was tightened at the Zabrze orphanage. The boys that usually slept on the upper floor were moved downstairs near the entrance and the girls were moved upstairs. Danieli went to his old neighborhood, dug up several guns that he brought back to the home and gave to Rudolf Wittenberg. The latter gave the guns to members of the “Ichud” kibbutz who were living at the Jewish compound while preparing themselves for Aliyah to Palestine. The older youngsters assumed defensive positions around the compound. Danieli was given two of his guns back to help defend the orphanage. Apparently, other weapons were also found for self–defense. It was a particularly difficult time for people who had already been through so much.

Jews throughout Poland and other areas of Eastern Europe became terrified at the situation. Since the Polish government was powerless to act, it decided to let the Jews leave, regardless of the consequences. Of paramount importance was the stability of the Polish government. The Polish Assistant Minister of Defense, Marshal Marian Spychalski, was ordered to conduct secret negotiations with Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman, one of the leaders of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto uprising and a member of the Central Committee of Polish Jews. An agreement was reached whereby Jews could leave Poland, no transit papers would be necessary, but they could take no gold or foreign currency. All transportation arrangements were the responsibility of the Polish Brichah as were all medical issues and special problems. The Polish government and institutions were not officially involved in the Jewish exodus. The agreement was secret and not announced publically by the parties involved. It was to commence on July 27, 1946, and end about February 1947.

|

|

| Yitzhak (Antek) Zuckerman |

|

|

| Marshal Marian Spychalski (center) |

|

|

| Children transport arrives at Nachod camp. |

|

|

| The Village of Nachod on the Czech side of the Czech–Polish border. |

The Brichah, with the financial assistance of the Polish JDC, agreed to funnel the massive exodus across different points along the long Polish–Czech borders. In 1945, 5,000 Polish Jews crossed the Polish–Czech border illegally. Following the Kielce pogrom, a mass movement of Polish Jews began to head to the Czech border. In May of 1946, 3052 Polish Jews crossed illegally to Czechoslovakia, in June of 1946, 8,000, in July of 1946, 19,000. August 1946, 35,346, in September 1946, 12,379 Jews crossed the border illegally [2]. During 5 months 77,777 Polish Jews crossed the Polish–Czech border at a single place called Nachod. Of course, there were other crossing points along the border namely at the village of Broumov. The number of Polish Jews leaving Poland were staggering in relationship to the total numbers of Jews following World War II. Of course, Polish Jews kept returning to Poland from Russia and soon joined the Brichah transports.

All of these Jews poured into Czechoslovakia illegally through various Polish border points namely Krosno, Dukla, Nowy Sacz, Kattowice, Walbrzych. Some Polish Jews actually left Poland legally to various Western countries and the USA. The total Jewish population in post–war Poland was 42,662 Jews in May 1945 [3]. By July 1946, with the massive arrival of repatriated Polish Jews from the Soviet Union, the number swelled to 240,489. But this number constantly declined with the mass departure of Jews as indicated above. The number of Jews in Poland at any given time following the war could not be ascertained due to the fluctuations.

|

|

| Polish Jews crossing the Polish–Czech border in broad day light. |

|

|

| Polish Brichah transporting Jews across the Czech–Polish border |

|

|

| Israel Gaynor Jacobson, JDC director in Czechoslovakia |

|

|

| Zdenek ‘Zoltan’ Toman (Asher Zelig Goldberger), Czech Deputy Minister of the Interior |

|

|

| Transport of Polish Jews leaving Nachod camp on their way to the Austrian or German D.P. camps |

The temporary refugee camp of Nachod had to be expanded rapidly to cope with the large number of arrivals. The camp would handle about 1,000 refugees for a day or two and then ship them on to Austria or Germany. The JDC in Paris sent huge stockpiles of food, clothing, and medicines to these reception camps to provide the refugees with the basic necessities before their departure from Czechoslovakia. In spite of the haste of organization the reception camps performed extremely well under the leadership of the JDC director of Czechoslovakia, Jacobson. The Czech government, particularly the assistant minister of the interior, Zdenek Toman or Asher Zelig Goldberg, helped the situation by granting the necessary permits for all these

|

|

| Polish Jewish children leaving Poland following the Kielce pogrom |

operations within Czechoslovakia. They gave the JDC and the Brichah a free hand in the country. Both Jewish organizations used it to the full extent. They enabled the Czech Brichah to work very closely with the Polish Brichah. The Brichah organization was run along national lines namely Polish Bricha or Italian Bricha. Each Brichah unit was familiar with the language, territory and customs of the country. The Polish Brichah was not of great use in Germany, but did develop excellent relations with the Polish border guards as the picture below shows.

|

|

| Polish border guard officers with Polish Brichah officials |

Translator's Footnotes

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Zabrze, Poland

Zabrze, Poland

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 13 May 2016 by JH