|

|

|

[Page 5]

| We Want To Live © 1949- Jacob Rassen © 2007- the Family of Jacob Rassen |

[Page 6]

|

For his translation of the original 1949 text by Jacob Rassen, Professor Murray Sachs of Brandeis University. For her editing of Professor Sach's translation, Beth Homing. For his help in publishing this book, Bill Nowlin of Rounder Books, Burlington, Mass.

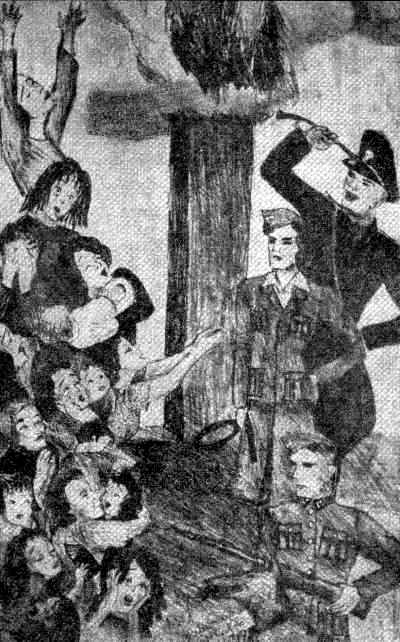

The graphics contained in this book were from the origina11949 printing. Although their quality varies, we thought it best to include them to preserve the integrity of the original published work.

(from the original 949 text) ABRAHAM SHAPIRO (Boston) And Simon and Jacob Black, Robert Band, Rabbi A. Goldin, Max Volk, Yafe, Robert Laps, M. Levine, Frank Sandler, Dr. and Mrs. Sudarsky, Berol Segal, Tsvee and Hanna Plitch, Harry Kogan, Abraham Krieger, Samual Shereshevsky, and others- A heartfelt thank you and more power to all of you. |

[Page 7]

|

REMEMBRANCE!

May it be remembered in our hearts and in the heavens, and may it remain unforgotten for all eternity, that holy memory of our sainted and purified dead-our slaughtered six million Jews. REMEMBER! Remember what Nazi enmity has done to us-murdered our fathers, mothers, children, wives, sisters, brothers, one third of the Jewish people, our flesh and blood! |

[Page 8]

|

|

| ...and mothers and fathers will tell their children: “It happened then, in those dark years, when the evil beast had broken loose from his chain, and had ruled over human beings; when the evil beast undertook to wipe us out, the entire Jewish people, without mercy.... But we did not want to go under. We wanted to live. We fought, bitterly fought, for our lives.... That happened then, in those historic bloody days.” |

[Page 9]

(Introductory Remarks by Dr. M. Sudarsky)

“I am a hunted animal, just like a wolf, a fox, or a mouse.... Give me shelter, you thick forest! Strengthen in me the animal spirit!”

So wrote Jacob Rassen as he fled the Nazis. It could have served as an epigraph for his book We Want to Live-a book all Jews should read so tbat they will never forget what happened to human beings, to our brothers and sisters, to our fathers and mothers, to our entire people.

Turning one page after another, we come to understand how this Jew-the&150;scholar, the weakling, the persecuted one-was driven to transform himself into a “hunted animal.” We see him wantonly trodden upon like grass under everyone's feet, and then we see life spring forth anew in him, as it does in a tree that, even with many branches and much of its trunk hacked away, sprouts fresh leaves. We see him tap his innate spiritual and physical heroism, those “irrepressible strengths of our people, which are forever alive and able to survive everything.”

The author goes through the entire course of suffering that befell our brothers and sisters in the years from 1941 to 1945. He depicts, in strong, realistic images, the terrible destruction of Lithuanian and Latvian Jewry. He tells of how he ran, terrified and bewildered, with the Jewish multitudes across the bloody and fiery roads, fields, and forests of Lithuania, Latvia, and Byelorussia, only to fall into the claws of the bloodthirsty enemy. He reveals the spectral horror of Dvinsk, Riga, Kovno, and other ghettos and concentration camps-places where human beings instinctively turn their backs on the tortured, the victims who are already walking their last mile.

At that point, on the very brink of death, the author was seized with a tremendous will to live, to fight, to avenge the innocent blood that had been spilled. With one leap he entered a world in which he remained dependent on himself alone. He lost his comrades. He lay buried in stables and barns between garbage and straw, and after that he took refuge in forests and ditches. He dug himself in, at night, like a mole in gardens, gnawed on all kinds of raw herbs, and finally, when he could no longer bear the hunger, he started taking food from peasant storerooms. No longer did he hope for human good heartedness. He only prayed to God to give him “sharp nails, the feet of a deer, wolf's teeth, and a stout robber's heart.”

Those moments, which are described in such simple human terms, are among the strongest in the book, and one must read them, and think deeply about them, in order to understand the weird transformations people are capable of when they want above all to live-to endure and accomplish something with their little piece of life.

[Page 10]

How could it have happened? What inborn human strengths make that kind of magic possible?

The author as I knew him was a good scholar and builder, an agronomist. He was a genuinely creative product of the broad, lively Jewish culture that existed in Lithuania between the two world wars. He received a traditional Jewish education, finished high school, and studied agriculture in Lithuania and Germany. He eagerly accumulated both Jewish and worldly knowledge, and dedicated all of it to the Jewish student youth in the schools established by the ORT (from the Russian words Obshestvo Remeslenofo zemledelcheskofo Truda, which mean The Society for Trades and Agricultural Labor). He introduced young Jews to the great discipline of land management, strengthening the foundation of the Jewish economy and social structure.

He published a collection of lectures about different branches of land management, the first such collection in Yiddish, in Lithuania. After that, he produced the land management section of the great “ORT Calendar” and several handsome books, including Most Beautiful Indoor Flowers, Jews and Land Management, and Gardening for Homes. In doing so, he created an entire terminology in Yiddish for a hitherto little-known scientific discipline. He was also a regular contributor to the Yiddish press (in “The Yiddish Voice” and “The Folk Sheet”), writing on agricultural and economic questions. At the same time, he was an expert consultant to the All-Lithuanian Alliance of Jewish Farmers, helping to subsidize Jewish agriculture and integrate Jews into the discipline of land management.

As time passed, Jacob Rassen became the leader of the entire land management division of the Lithuanian ORT. He directed the ORT's courses in land management, as well as the agriculture school in the special farms that the organization created. Together with students-most of them young refugees from Germany and pioneers who hoped to settle in Israel-he published a splendid book of writings about agriculture entitled We are Becoming Peasants.

Driven by his restless spirit and his passionate desire to be useful to his people, Jacob Rassen traveled to Israel for a year, and worked there as a highly qualified agronomist. But shortly before the war, he went back to Lithuania, as though driven by fate to be with his brothers and sisters in their horrible time of trouble.

Yet human beings, no matter how much trouble they face, remain human. Their thoughts, their spirit, their will to live, their faith-these are what maintain in them their human soul and move them to bold deeds. That is also how it was with Jacob Rassen. Not for long did he wander about in the forests like a passive animal, wanting only to wait out the storm in his lair. He was drawn to people, to the embittered, the angry, the combative, those like himself. On twisting side roads and detours, he fought his way at last to Russian partisans

[Page 10]

and helped to organize a new partisan army in the forests and swamps he knew so well. He became one of the boldest and most determined avengers of the suffering and violence that the Nazis and their allies inflicted on the Jewish people.

The author fought heroically in the ranks of the partisans, and in the end he managed to fight his way back, with the Red Army, to his old homeland. And there...there, it only remained for him to bewail the horrifying destruction that the ruthless Nazi beasts had left behind. He could not stay on in his old home, on the blood-soaked ground. He was driven on to new paths. New hopes awakened in his soul, a mighty striving toward a new land, toward a new life.

The realistic stories and pictorial renderings in this book seem like a dream to us, unbelievably barren. It is hard to imagine that anything like that could have happened to people.

And so, as we struggle to imagine it, we begin to grasp what a tremendous responsibility Jacob Rassen has assumed. He has realized that anyone who comes out of such a hell spiritually whole is obliged to bear witness before people, before earth and the heavens. The author tells us everything that he has seen with his eyes and heard with his ears, and everything that he himself has endured. Telling the stories, bearing witness, and never letting anything be forgotten-that is his mission on earth.

No matter how gruesome the tales might be, we must nevertheless read them and transmit them from generation to generation, in order to remember what kind of misfortune befell our people in the middle of the twentieth century. We Want to Live should serve as both a warning and an affirmation. It should reinforce our belief in the “eternal, spiritual strengths that are rooted in our people.” The Jewish people will, in spite of our enemies, continue to exist and to thrive. We will live to see our revival in our own land, and everywhere else in the world.

The author is now in America. May it be his lot here to record that new era of revival, in which our much-tested people will flourish.

| Dr. M. Sudarsky New York, September 1948 |

[Page 12]

| “I am the man that hath seen affliction by the rod of his wrath; He hath led me, and Brought me into darkness But not into light.” |

| (Lamentations, Ch. 3, verses 1&2) |

I am leafing through the half-ruined pages of my rescued diary and other writings. Pictures, scenes, and events I recorded during the years of destruction rise up again before my eyes. I am reliving the pain and suffering of that time, the indescribable sense of loss and helplessness people feel when they are being driven on their last journey-to death, to the slaughter, to prepared holes in the ground that will be their graves.

I see again the dug-up territory of Lithuania, Latvia, and Byelorussia. Mercilessly gruesome and darkly hopeless was the long, bloody road. First came the ghettos and concentration camps, and then my two escapes, my animallike existence in the woods, and my life-and-death struggle against the enemy with partisans in the hinterland. Finally, I took up the life of a soldier in the Russian army-until my return to Lithuania.

Only there, in my former home, was I able to fully remember the tremendous destruction that cast me, and thousands of others like me; out into the world, where we searched for the path to a new life, to a new land, to the Land of Israel.

I see and feel all of it again, and yet even I can scarcely believe that it truly happened.

I am again looking over what remains of my writings line by line, and trying to recreate exactly what happened to me and tens of thousands of other Jews in Lithuania, Latvia, and neighboring countries. Contrary to what a normal person living in normal conditions might think, nothing is exaggerated or invented here-the reality alone is fantastically grim.

Likewise, as I write this book, I have been combing through the couple of dozen songs and poems that I wrote down in the ghettos, camps, and forests. These songs and poems are reproduced here without alterations or “refinements.” They are just as raw and naked, as primitive and rough, as they were when they were created, under the direct influence of the bloody events. I do not put so much weight on their literary or artistic worth as I do on their historical value: This is how the songs were sung, how the poems were declaimed and passed along in the ghettos and camps, and so may they remain as a memorial to those who died and who disappeared.

To be honest, I myself don't know how the songs and poems came to be.

[Page 13]

I am neither a poet nor the son of a poet, and I wrote what I wrote not in the name of poetry, but simply ...I don't know myself. But I do remember that after I showed the first song-“The Living Dead”-to a friend of mine in the Dvinsk ghetto, he showed it to a few others, and it was, for a few days, sung in various melodies and given the title “The Ghetto-March.”

From that time on, my roommates and friends would say, “It is so exactly right. How are you able to capture it so well, and write down what all of us are thinking and feeling? Write down more things. Let people at least read about us later, if we are no longer here....”

It was not your destiny, my beloved friends, to survive. You are gone forever. May the rescued songs tell the world about you and thousands upon thousands like you, about your inhuman suffering, and, at the same time, about your hopes. May they show how you wore a human face until the very last moment, how you endured pain, bled, lived, fell, and...sang.

I hope that my descriptions, together with the songs and poems, will give the reader a faithful reflection of how those dear to us, in our former home, lived and suffered, and how they perished in blood and fire.

To know the truth about the fate of our blessed and pure victims, and to carve into our hearts, as though on gravestones, a holy memorial-that is how we repay our eternal debt. It is the last honor that we can bestow upon those who died.

| Jacob Rassen |

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

We Want to Live

We Want to Live

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 10 Dec 2017 by LA