|

|

|

[Page 43]

Translated by Sara Mages

Most of the public activities concentrated in the synagogue and Beit-Hamidsrash [House of study]. The synagogue was always crowded with worshipers and students. It served as a meeting place for scholars, a treasure house of books for students and “Home owners,” an almshouse for the elderly and wise poor students, a hostel for visiting scholars, a resting place for the weary and the persecuted, and a shelter from trouble and grief.

The echoes of the big world reached it by wandering guests, beggars or emissaries from Israel and other countries.

The proceeds from the Aliyot[1], and other honors provided an additional income for the upkeep of the synagogue and for various social purposes like: supporting the needy, benevolence, “Kamcha Depascha”[2], assistant to the “burnt,” visiting the sick and funerals. The relief operations expanded during the days of the pogroms, and additional funds were added to the regular contributions.

Study took an important place in Beit-Hamidsrash. The title of “Rav DeKloiz,” meaning “Rabbi of Beit-Hamidsrash,” was added to the community's presiding judge. It was kind of an academic degree attached to his official role. Those who received a special allowance gathered in the Klotz[3]. Donations were given by private donors so they can sit in the house of learning and study the Torah day and night.

At night, the shadows of Jews, who were “professional students,” were seen on its walls. “Home owners” and “business men” swayed next to the pillar, studying to the light of milk and wax candles. Some came for midnight mourning prayers to lament the destruction of the temple and the exile of the Divine Presence, and some came at dawn, summer as winter, sat and studied until Shacharit [morning prayers].

Conferences, parties, social and family gatherings, took place in the synagogue or in its courtyard. Like: charitable meals of different societies, the final reading of the six orders of the Mishnah, the coronation of the town's rabbi, circumcision and the joy of marriage.

A large crowd participated in the wedding. A procession with musical instruments walked from the house to synagogue's courtyard, and young and old carried in the daylight lit Havdalah candles in their hands.

All statements and important warnings were made from the synagogue's Bimah[4]. When a person has done injustice to another or performed a morality sin in public, the reading of the Torah was delayed and the matter was brought before the community who sometimes imposed a penalty on the sinner: excluding him from an Aliyah or from passing before the Bimah for a certain period of time. Donations and banishments were announced to the public in the synagogue, and all kinds of restrictions that were imposed on the community by the synagogue and by the authority.

So, the synagogue was vibrant organism on weekdays, on the Sabbath and during the holidays.

The various craftsmen, who formed a mutual aid association, did their best to hold a regular Minyan[5] for their members, and if they had the financial means they would have built a special building for this purpose. In the 19th century, with the increase in the number of trade unions, also the number of their synagogues increased, mostly in the big cities.

[Page 44]

As mentioned, these synagogues and Minyanim were mutual aid administrative centers for the members. These Minyanim and synagogues also had official names like:

“Poaley Tzedek,” “Zovchai Tzedek,” “Chav,” “Chesed shel Emet” and others. They also had a decorative seal, sometimes with the union's logo.

And so, the synagogue gathered, inside and around it, the three foundations of the Jewish world: “Torah, Avodah, and G'milut Hasadim” [Torah, work, and benevolence].

For generations the image of the Jewish community was formed in the synagogue. The synagogue was also the meeting place where important matters in the Jewish world were discussed, like the elections to various organizations. Public affairs, like tax rates and community regulations, were ruled in the rooms adjacent to the synagogue. One of the committees was the synagogue affairs committee, which had the authority to run the synagogue's affairs and the construction of new synagogues.

Translated by Sara Mages

The townspeople were proud to say: “There are only three synagogues in the Jewish world similar to ours.”

The location of the synagogue

Contrary to regulations, the synagogue was located on the slopes of a small hill at the north-east end of town. The reason is - there were two Christian churches in the southern end of town, and the Jewish residents wanted to distance themselves, as much as possible, from any contact with the gentiles. A known law in the Jewish towns in Poland said that a synagogue couldn't be taller than a Christian church, and this law was also kept in Olkeniki. The Christian churches were taller, but the most noticeable building in town was the synagogue's building. And the reasons for that - the synagogue was built on the slopes of a hill, a matter that added to its height, and also its shape that resembled a pagoda added to its height.

The synagogue was built at the end of the wooden synagogues period. Documents tell that a worshipers' meeting took place in 1790, and they demanded that a new synagogue will be built after the old synagogue burnt down. The construction started in 1798 and was completed two years later. On the outside it looked like a Chinese pagoda – a typical synagogue style of that period. The synagogue's beams were made from big pine trees that were the pride of the town. The trees were cut in the forests, and each beam was 60(!) centimeters thick.

Before the Holocaust, the color of the outside walls was dark-grey because of the rains and “old age.” Because of the length of the beams - more than 10 meters – it was on the verge of collapse. Fifty years ago, the beams were reinforced by bright bars that were attached vertically to the walls. However, the internal structure was made of white wood – walnut, and the color remained clean and didn't change since the synagogue was built.

Aron HaKodesh

Four panels were fixed to the doors and the two pillars of Aron HaKodesh [6]. The two pillars are called “Boaz” and “Jachin” after the two pillars in the destroyed Holy Temple. A special mechanism moved the panels, and their hands indicated the seasons of the year, the zodiac, and the holidays according to the lunar cycle and in comparison with the solar cycle. The panels were calculated from the time of their construction to 448 additional years, that is, from the year 5558 to the year 6006.

These wonderful panels attracted the hearts of thousand who visited the synagogue.

The Ark was covered with a Parochet[7] and a Kaporet (a cloth that hung over the Parochet). The Parochet in Olkeniki was very famous. It is told that when Napoleon Bonaparte passed through the town on his way to Russia, he admired the artwork of the synagogue's interior. As an appreciation, he ordered to cut a section from the cover under his saddle, and gave it to the town and to the synagogue. The town's leaders prepared a Parochet from the cover. The Parochet's fabric was hard - it was embroidered with gold and silver ornaments. It is said, that it was difficult to fold the fabric, and its weight was more than three kilograms (!). The words “Gloria et Patria” (for glory and fatherland) were embroidered on the Parochet's corners. The townspeople fought many Parochet's “wars.” In 1915, Russian generals, who fought in the First World War, came to town and stole the Parochet. A general mourning was declared in town, and the synagogue's Gabbai traveled to beg before

[Page 46]

the authorities to return the plunder. And indeed, the Parochet was returned after a lot of pleadings. Baron Ginsburg tried to purchase the rare Parochet for the promoters of the “Haskalah Movement” in Peterburg. He offered the town an amount equal to 30 thousand Israeli Pounds. But the townspeople stood before the temptation and didn't sell it. The Parochet remained in the synagogue until it was destroyed.

The Bimah

The Bimah was composed of three floors and its style was different from Aron HaKodesh. A beautiful legend explains why: “….the Ark was built by a very talented artist. Before his death he managed to carve half of the “Shiviti”[8]. In his sick bed he said: “The artist who could finish the 'Shiviti' - will be allowed to build the Bimah. In time, such an artist was found. He carved the decoration with accuracy, keeping the style of the carving, but he built the Bimah according to a later style.”

Unlike the Ark, there weren't any decorations on the Bimah. The first floor was the floor level and its height was about a meter above ground. They climbed to it from the north and the south through gates covered with triangular awnings. A table for reading the Torah and a bench stood on the floor. The space between the floor and the Bimah was filled with torn books. The second story carried the pillars and they supported the Bimah's roof. There were 8 pillars, and every other one had a small awning that looked like the awnings of the entry gates to the Bimah. The third story was made of octagonal frames embedded with curved leaves and flowers, and decorated with artificial flowers. There was a round pillar the middle of the balcony, and an eagle with outstretched wings and a crown on his head stood at its center. It was speculated that it was the symbol of the Polish Government.

Circumcision ceremonies also took place in Olkeniki's synagogue. ”Elijah's chair”[9] where the Sandak [godfather] sat, and the “foreskin” table which was covered in sand were located in the corridor. We can read an interesting accurate description of a synagogue circumcision ceremony (not necessarily in Olkeniki) in the book “Pirkei Yaldut” [Chapters of childhood] by Yitzchak Dov Berkowitz.

“…when we arrived to the synagogue all the guests were already there. Rabbi Hirshel-Berel led the mother and her baby to the Bimah, and sat her on the bench on which the Torah scroll is rolled after the reading of the Torah. Today, it is called “Elijah Chair,” a place where the Sandak sat holding the baby on his knees…”Weddings and funerals took place in the synagogue's stone courtyard.

The destruction of the synagogue

On Rosh Chodesh Tamuz 5701 – 25 June, 1941, a bomb was dropped from a Nazi aircraft. The bomb hit a Soviet fuel tanker that stood in the town's market across from the Catholic Church. A quarter of the town's building burnt down including the synagogue and Beit-Hamidsrash. Three months later, on the eve of Rosh Hashanah 5702 – 20 September, 1941, all the townspeople were led for liquidation to the nearby town of Eshishuk [Eišiškes]. The few who survived the Holocaust returned to the town in 1944 and found it in ruins. The square in front of the synagogue and Beit- Hamidsrash was desolated and weeds grew between the ruins…

Translated by Sara Mages

“Chevrat HaPoalim”

Most of its members were poor people who united for shared interests. Since the public life concentrated around Beit–Hamidrash also “Chevrat HaPoalim” [the workers' society] was associated with Beit–Hamidrash. The “Stiebel” belonged to the “Chevra” and the members prayed there on the Sabbath and on holidays. Between Mincha and Ma'ariv the rabbi taught them a chapter from “Chayei Adam” and “Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.” Before the holidays he taught them matters concerning the holidays. The prayer and group study, the parties on “Simchat Torah” and the elections of the treasurers by ballot – brought its members closer in their daily life and on days of joy and grief. “Chevrat HaPoalim” continued to exist during the world wars. At the beginning of the century Rabbi Feive Ginzberg served as the rabbi of “Chevrat HaPoalim”. He was the town's judge and mohel. During the holidays he led the prayers at the synagogue. As a wise Jew he knew how to behave with the “simple folks,” and was also full of life in his old age. For a certain period he taught the Torah to the town's boys in his home. His house was wide open for everyone.

In those days the members of the society prayed in Beit–Hamidrash. In “Chevrat HaPoalim” it was customary that the parents enrolled their children to the society at a young age. The members of the society were mostly craftsmen and small merchants who earned their living from the sweat of their brow. “Chevrat HaPoalim” sent its candidates, who excelled in their integrity, for the elections to the synagogue or any other institution. All the sectors of the public trusted them. In the last years, before the Holocaust, when the community was abolished and a “council of Gabbim” was appointed in its place, almost of them were candidates of the aforementioned society. When it was dangerous to enter Beit–Hamidrash, members of “Chevrat HaPoalim” stood on guard on the Sabbath and on holidays. They established their own minyan for prayer throughout the year. They even came to read the Torah on the High Holidays. On the Sabbath, between Mincha and Ma'ariv, they studied “Chayei Adam” and “Ein Yaakov.” Before the Mincha prayer they studied the weekly Torah portion and “Pirkei Avoth.” After the death of Rabbi Feive they didn't have a regular “Maggid Shiur” [1] for several years, until the rabbi's brother–in–law, Rabbi Chaim Berger, started to say the lessons regularly.

In the last year of the town's existence, in 1941, when the Soviets entered, the Jews of “Chevrat Chayei HaAdam,” who came from the workers' sector and enjoyed the labor of the hands, were the backbone of Judaism and religion in town. With head held high and determination they kept the last remnant of “Chevrat Chayei HaAdam.” To their last day they didn't stop to study their regular mishna in “Chayei Adam [2].”

“Chevrat Ein Yaakov”

The northern table in Beit–Hamidrash belonged to “Chevrat Ein Yaakov [3].” When Rabbi Mendel z”l stopped teaching because of his weakness, Rabbi Chaim David Zilin inherited his place. Every day, between Mincha and Ma'ariv, he taught current affairs. On the month of Elul he translated, even to Yiddish, a chapter from “Mesillat Yesharim” [“Path of the Upright”]. When his student, Rabbi Shmuel Tzvi HaCohen Moshkowitz, who studied with him for many years and managed to understand a page in the Gemara on his own, left “Chevrat Ein Yaakov” and moved to study with “Chevrat Shas,” Rabbi Chaim David mustered the last of his strength and called him to justice because it was impossible to give up on a decent student in “Chevrat Ein Yaakov.” Meanwhile, the town was abuzz. The two “sides” got up and stood alongside the litigants. Rabbi Shmuel Tzvi won the judgment.

[Page 48]

However, the tailor from Eshishuk remembered the kindness of Rabbi Chaim David. When he gave a lesson in “Ein Yaakov.” which was at a different hour than the lesson at “Chevrat Shas,” he continued to sit and listen to the lesson of Chaim David the Shamash.

The membership in these societies gave each of its members a status in the town and in the society.

“Chevrat Shas”

Not everyone was able to be counted among its members because each candidate was required to understand a page in the Gemara. The candidate to “Chevrat Shas” [Talmud Society] had to participate in the lessons for a considerable period time and to arrive to the lessons at the time that is written in the society's regulations. Close to 70 minyanim (70 men) belonged to the society. The lesson took place every day between Mincha and Ma'ariv. The members belonged to all the classes of people. They prepared themselves for a long time for the conclusion of Shas, and all the townspeople participated in this celebration. The “Maggid HaShiur [1]” was the town's Chief Rabbi.

“Chevrat Mishnayot”

There were more members in “Chevrat Mishnayot [4]” than in “Chevrat Shas.” On Saturday morning the rabbi gave the lesson after the second minyan. Because of the overcrowding next to the table many had to stand and study in a circle around it. It's necessary to mention Rabbi Chaim Cohen, because after the death of Rabbi Shimon Bensky z”l he was one of the few who continued to teach the lessons even though he was very busy with his businesses.

A. Sidki, A. Hezekiah

Translated by Sara Mages

The holidays in Olkeniki were holidays of joy and light, but the holiday of “Simchat–Torah” exceeded them all. Mr. Shlomo Ferber tells a story that he had heard from Mr. Y. Agami who's also a former resident of Olkeniki:

All the residents of Olkeniki, from the water drawer to the merchants and the homeowners, studied the Torah every day, and for that reason each one of them saw the holiday of “Simchat–Torah” as his own. All the townspeople, except for the Perushim [1] and the Torah scholars who sat in Beit–Hamidrash and studied at irregular time, set a special time for the study of the Torah.

The workers and the poor gathered around R' Feive the slaughterer who placed their “minyan” in a room on the right side of the synagogue's “plush“ [vestibule]. Every evening, R' Feive, who was handsome, wise and popular, taught a chapter from “Chayei Adam” [“Life of Man”] or from “Kitzur Shulchan Aruch.”

The “homeowners,” and those who were students in Beit–HaMidrash in their youth, sat every evening next to the long table on the right and listened to a Gemara page from the rabbi himself.

R' Avraham Mende, the jealous Perushm who was “Orech Galut” (meaning, he left his home and his family, walked from town to town and studied the Torah), gathered around him a group of “Ein Yaakov” students.

R' Zev HaPerush sat nearby and read his lesson in the company of several Yeshiva students.

Along the benches sat dozens of young men hunched over the “stenders” (“pages”).

[Page 49]

They delved, in a soft melody, in the questions of the Gemara that its yellow pages were illuminated by stearin candles.

During the holiday the joy burst from each heart and every study group celebrated it in its own home. The festivities began the evening of “Simchat–Torah” and continued until the conclusion of the holiday. The “homeowners” gathered at the rabbi's house on holiday eve and started to eat and drink. After dinner, they returned in groups to Beit–HaMidrash, gathered around the Bimah, and “bought” verses from “Atah horeta lada'at” and “Shir Hama'aloth” from the auctioneer. They “paid” for the verses with drinks and all sorts of sweets and food in honor of the holiday. The sales and the celebration continued until midnight. On the next day, everyone brought a contribution for “ba'avor she–nadav,” and when the prayer ended the “homeowners” returned to the rabbi's house to continue to sing, eat and drink.

At the same time, the “simple folks” gathered at the home of R' Feive the slaughterer and there they celebrated with their rabbi, their Torah and their holiday. The slaughterer, who had to feed several dozen learners and worshipers of his “minyan,” got ready for this simcha two weeks in advance: he put aside all the intestines, spleens and other organs from the animals that he had slaughtered, and accumulated them for his family and his many guests. On the holiday eve the Rebbetzin and her neighbors were busy preparing the food for the holiday.

And now to the story itself:

One year, several days before the holiday, two of the important homeowners in town decided to pull a prank on “Simchat–Torah” and surprise the townspeople. The two were R' Avraham Azeranski – the synagogue's treasurer and the “reader of the Torah” who was well–dressed and rich, and his friend R' Chaim–Meir Nanes who was the “reader of the Torah” in Beit–HaMidrash and a high official in the forest trade. They decided to “pinch” the refreshment for the holiday, the stuffed intestines and the cooked and fried spleen, which were kept in special pots, from the oven of R' Feive the slaughterer and bring them to the rabbi's house.

They sat the “zero hour” for the time of the reading of the Torah. When everyone will be busy in the selling of aliyot, in the aliyot to the Torah and dancing they'll slip out of the synagogue, cross the two streets that separated the slaughterer's house from the rabbi's house, distract the slaughterer's daughters with all kind of excuses and “pinch” the refreshment. They kept the operation in the strictest confidence and only the wise rabbi, R' Yakov HaCohen z”l, knew about it.

The day of “Simchat–Torah” arrived. The two snuck out when the Cohanim were invited to the Torah and turned to the slaughterer's house. On the way they met the slaughterer's wife. They greeted her and were about to move on. To her question about the big baskets in their hands, they answered that they want to bring drinks to the rabbi's house because of the large number of invitees. The two approached the slaughterer's house. R' Chaim–Meir entered the house and called the two daughters to come out to the yard. While he was telling them something, R' Avraham entered the kitchen, opened the oven, removed the pots, put them in the baskets and left. The hot refreshment arrived to the rabbi's house.

After the prayer the “homeowners” gathered at the rabbi's house. The conductors of the singing and drinking were our two friends, R' Avraham and, R' Chaim–Meir. The guests were ready for the main course– quiche and cholent. Meanwhile, “Chevrat HaPoalim” arrived with their children to the home of their rabbi, R' Feive, and also here was a great deal of joy and revelry.

[Page 50]

The tables were set with all the best. R' Feive, who was a Lubavitch Hassid, started to sing and everyone followed him. Suddenly – Oh no!

The slaughterer's wife, who stood in the middle of the room with outstretched arms and red face, shouted: “Jews! The stuffed intestines and the spleens have been stolen!” noise and tumult, rushing around, inquiry and demand to find out who had the audacity to do such a thing. When they questioned the daughters who came to the house that day, they answered and said that R' Chaim–Meir came to inquire about a matter and they saw him leaving empty–handed. When they asked the daughters about the important matter that brought him to the slaughterer's house, they learned that that it was a trivial matter and understood how it was done. The messengers, who set out to find R' Chaim–Meir, found him as he was conducting the celebration at the rabbi's house. The negotiations began and the secret was revealed to all who came to the rabbi's house. The “injustice” that was done to the “simple folks” was amended on the spot. R' Feive was carried from his home to the rabbi's house accompanied by dozens of his fans. At the rabbi's house the children of the poor mingled with the homeowners, ate cholent, spleens and intestines with them, and danced and sang with joy. The two heroes of the deed were praised, and people talked about the prank of R' Avraham and R' Chaim–Meir for several weeks.

“And in the following years” – Mr. Ferber concludes – we brought up memories from the good old days with a sigh and said: there weren't good days in Olkeniki like the days of “Simchat–Torah.”

Amiran Sterk, Chaim Sabo

Translated by Sara Mages

Introduction

We, who now inhabit our country, have won to be included in the generation of redemption. However, we are just a link in a chain. Links of an enormous revival movement of the Jewish people in Europe at the end of the 19th century which managed to get it out of exile to redemption. We call this movement “Zionism,” because its ultimate goal was to bring all the Jews of the world to Zion.

Dan Brener, 5727 – 1967

The Zionist way of life in town

The longing to Zion was rooted in the nation long before the arrival of modern Zionism. The Jew lived in his place of residence in the Diaspora, but his heart was in Eretz–Yisrael. Morning and evening the Jew prayed “May our eyes see Your return to Zion in mercy,” and fully believed that even though the Messiah will be delayed – he will come.

The Jews of Olkeniki dreamt about Eretz–Yisrael and every news item, exhibit or fruit from the country was considered a scarce item for them.

In those days emissaries of the four holy cities, Zefat, Tiberias, Hebron and Jerusalem, walked around the towns. They came to solicit donations for charitable causes and for the Yeshivot. “Shelichei DeRabonan” [emissaries of the rabbis] brought small bags of soil from Eretz–Yisrael, receipts on which the name of their Yeshivot was printed, pictures and drawings of the country's landscape – the Western Wall, Rachel's Tomb and the Cave of the Patriarchs. The townspeople bought these pictures and hung them in their homes. Many Jews bought small bags of soil because they wanted them to be placed in their grave. Many elderly Jews immigrated to Israel to die and be buried there. The road to Israel was very dangerous and complicated and lasted many months.

In 1882–1890, when the Bilu'im's agricultural settlements were established, pictures of Jewish farmers and Jewish settlements in Eretz–Yisrael started to appear. These pictures excited the souls of the Jewish residents, especially the younger generation.

The establishment of the Zionist movement in town was fast because the townspeople accepted its ideas. Since their life in the Diaspora was life of misery they understood the requirement of Zionism to eliminate the Diaspora. The Zionist idea changed the face of the Jewish society because it turned it into a working and creative society.

The Jews of Olkeniki were very interested in all areas of Zionism and even sent delegates to the congresses. They opposed the Uganda Scheme.

The town's residents gathered prior to the Fifth Congress and sent this letter to the congress:

[Page 52]

| In the name of God who has chosen Zion The city of Olkeniki in the Vilna District To our distinguished brothers, the active members of the Zionist Committee, Shalom! Today we gathered to celebrate the opening of the “Jewish Colonial Trust.” In the presence of a large audience we, the undersigned, came to a clear and define recognition that Zionism is the special solution for the Jewish question in all the countries of the world. Therefore, we decided to express our emotional respect, great trust and confidence to the Zionist Movement and its leaders. We promise, on our side, to support the proposals and make all the efforts to distribute them among all the classes of people and all their parties. We are willing to stand shoulder to shoulder with the best leaders of our nation for the benefit of this movement and its usefulness. We ask the honorable members to express our blessings, which come from the depth of our hearts, to our nation's delegates and the attendees of the Fifth Congress in Basel. We'll pray to God, which resides in Zion, to help us to find the right way that will lead us to peace and tranquility in the land of our forefathers. Sunday, 2 Kislev, “Zot Chanukah” 5662 [The eight of Chanukah – 13 November 1901] Signed: the residents of the town |

The volunteering of Olkeniki's residents wasn't only expressed in words. When they learned about the campaign for the purchase of “Share Certificates for Eretz–Yisrael” or Shekalim, they immediately established a committee whose duty was to walk from house to house, explain the importance of the campaign, and sell shares and Shekalim.

A few families started to immigrate to Israel at the beginning of this century. In 1900, the old tinsmith, R' Monash–Goldman, immigrated from Olkeniki to Israel with his wife. In 1911, R' Velvel Zev Braz immigrated to Israel with his family.

Gad Landau

|

[Page 53]

|

|

[Page 54]

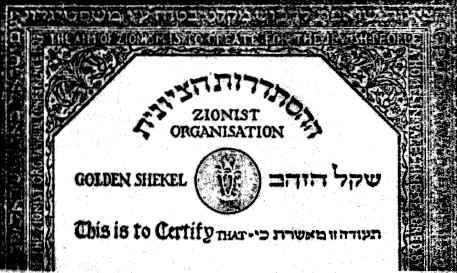

Shekel

The Shekel was the membership card to the World Zionist Organization. It was named after the ancient Jewish coin – the Shekel. The name was suggested by Dr. David Wolffsohn z”l whose leadership was approved at the First Zionist Congress.

The Shekel gave the right to vote and be voted to the Zionist Congress. Every Jew, who accepted the decisions of the congress and recognized the “Basel Program,” was able to renew his membership every year.

The Balfour Declaration

“The declaration shined like a lightning on a dark night, ignited the hearts and thrilled the town's youth. The details of the discussions and the negotiations weren't known in the town. We didn't ask about it, the principle of the content was clear. From now we have a corner in the world to which we can turn.

I remember the procession which was led by national flags and the Torah scrolls under the chuppah. After the festive event all the town's residents, the Christians among them, gathered in the square across from the Old Synagogue. The pharmacist Strenin gave the opening speech and the town's rabbi spoke after him. After the speeches of the brothers, Yeshayahu and Hillel Dan, I, the youngest, gave a speech about the “Vision of the dry bones.”

Since then, an extensive cultural activity started among the layers of the town's youth. There was hardly a young person who didn't participate in these activities. Everyone, shoemakers, tailors, seamstresses, blacksmiths and housewives participated in collecting contributions for the movement's funds”.

According to – “Ha–ayara be–lehavot” [Olkeniki in Flames]

From the words of Mr. Shlomo Ferber

Adi Haskelovich, 1969

The Zionist activity in town

The “Balfour Declaration” resulted in a wide cultural and educational activity among town's youth. There was hardly a young person who was indifferent to the activities of the Zionist Movement. All the people who work, and even the unemployed, contributed their contribution to the movement.

The children studied about Eretz–Yisrael from a young age, long before they entered a primary school.

The youth was recruited for activities for “Keren HaKayemet” and “Keren HaYesod.”

The youth movements conducted conferences, meetings and summer camps.

[Page 55]

They spoke Hebrew in these gatherings, learned about Eretz–Yisrael and sang from the songs of Zion.

The youth began to train themselves for immigration to Eretz–Yisrael.

The founding of “HeHalutz” in Olkeniki

In 1920, during the period between the Polish and Russian rule in Lita, a group of members of “Tzeirei Zion” traveled in indirect roads and on foot from Lita to Israel. The “Halutz” movement, and later, “HeHalutz Hatzair,” were established on the basis of this pioneering migration of the members of “Tzeirei Zion.” Since then, about ten people immigrated from Olkeniki to Israel before the Holocaust. Fifteen survivors, who served in the Red Army and the ranks of the partisans, immigrated to Israel after the Holocaust.

|

|

A membership card to the “Halutz” movement |

[Page 56]

Four principles were required from the members of “HeHalutz”:

“Hakhshara”

In the 1930s, graduates of the youth movements could gain an immigration certificate to Israel only if they have been approved by the members of the “Hakhshara.”

“Hakhshara” [training] camps were established next to agricultural farms or industrial plants. The members worked there for their living, received training in manual labor and became accustomed to communal life. The physical effort was difficult for many, but they found satisfaction that they were able to overcome any obstacle and hold a job.

The members of the “Hakhshara” tried, as much as possible, to manage their life as life in a kibbutz in Israel. In addition to work they also engaged in sports and studies. They mostly studied Hebrew and knowledge of the Land of Israel, but they also tried to expand the general education of the members.

Some members spent several years in a “Hakhshara” camp because of the limited number of immigration certificates to Israel. The longing to Israel rose during this period. These longings were expressed in stories, songs and a collection of memorabilia that were sent by friends and members who already immigrated to Israel.

When the graduates of the “Hakhshara” came to Israel they constituted the best human power for the settlements. It was possible to find them in the kibbutzim and in the agricultural settlements that were established throughout the country until the end of the 1930s. Today they occupy a prominent place in all sectors of the economy, military and government.

The Second World War and the Holocaust, which came with it, prevented thousands of members, who were in “Hakhshara” camps at that time, from immigration to Israel.

Yosef Robinzon, D. Stiasni, S. Florian, G. Rosental, Y. Doron

Translated by Sara Mages

The Jewish youth movement gave birth to the Israeli youth movement, and it's also one the most prominent examples of the formation of a constructive youth movement.

It's necessary to distinguish between the Jewish youth movements that are familiar to us today: between the youth movements in Israel and youth organizations in the Diaspora – and the movements that existed in Europe from 1910 to the Holocaust.

The youth movements in Europe expressed the rebellious nature of the young Jewish generation. The period between the years 1910–1920, was a period of unrest in Europe. The First World War and the Russian Revolution were only a few of the crises that struck the continent in a period of fifteen to twenty years.

These crises also affected the youth in each location, but the Jewish youth was influenced by them the most. It's clear, that in those days almost every educated Jew, like young educated individuals from other religions and nationalities, revolted against the sins of the previous generation.

However, in addition to that, the young Jews obviously felt that it was time to correct their situation and the situation of their nation.

This way, when they connected together the quest to fix the world and the idea of populating the Land of Israel, they have created the appropriate conditions for the development of the Zionist youth movement.

Yael Avni, Ruth Barak, N. Yitzhaki, Y. Cohen, M. Shapira

[Page 58]

And these are the youth movements that operated in Eastern Europe

Hashomer Hatzair: – A pioneering–socialist youth movement that was founded in Galicia and other locations in Poland as a Youth Scouts Federation. In 1927, it was decided that the educational–socialist movement will become an independent youth movement and will be associated with “Hakibbutz Haartzi. [1]”

Hanoar Hatzioni: – A pioneering youth movement that was founded in Poland in 1932. At first it was associated with the “General Zionists Party” and later with “HaOved HaTzioni. [2]”

Betar: – Abbreviated name of Berit Yosef Trumpeldor. It was founded in 1923 in Riga, Latvia. At first it was associated with the “Revisionist Zionist Alliance” from which evolved the Herut political party in Israel.

Gordonia: – A pioneering Zionist youth movement that was founded at the end of 1925 in Galicia. It was named after Aaron David Gordon. In Israel, its members were absorbed in the Kvotzot [agricultural settlements] of “Hever HaKvutzot. [3]”

“Hashomer Hadati” “Bnei Akiva”: – Religious youth movements which started to operate in Eastern Europe in 1928. The movements were associated with the political party “Hapoel HaMizrachi” and “HaKibbutz HaDati. [4]”

“HeHalutz”: – A world federation of young Jewish Zionist who trained themselves for immigration and manual labor in Israel. It was founded in 1917 in Russia by Yosef Trumpeldor and developed rapidly in Eastern Europe and the United States.

“HeHalutz Hatzair”: – The young guard of the “Halutz Federation.“ Most of its members came from the movements “Dror“ and “Habonim,” and also from the ranks of non–partisan Zionist youth.

Yael Avni, Ruti Barak

Translated by Sara Mages

The Lithuanian Division - what is it?

At the outbreak of the war between Russia and Germany many refugees streamed eastward. Among the escapees were members of the governments of the Baltic Soviet Republics and Soviet government officials who knew that they would be murdered if they fall into Germans' hands.

At the end of 1941, the Soviet government decided to establish national units within the framework of the Red Army in order to lift the “morale.” In addition, they also sought to foster patriotism in the hearts of the various nationalities that showed little affection to the regime. In this way the foundation was laid for the Lithuanian Division. Its base was established in the town of Balakhan on the banks of the Volga River, a short distance from the big and beautiful city of Gorki. The exact name of the division was “The 16th Lithuanian Rifle Division.”

Later, the division was presented with the “Order of the Red Banner,” and much later - the name of the city of Klaipëda (or Memel) that the division captured in 1944. The aforementioned names: “The Red Banner” and “ The Kloipidit” were added to the division's official name.

How was it founded? Who trained it?

The division was established in the month of November or December 1941.

The division was established by the men of the Red Army who managed to retreat in a fairly organized way to Russia, commissars in the Russian Army which were based in Lita, cadets in the officers school (among them was Polkovnik Vakesky who was later awarded the title “Hero of the Soviet Union”) and party activists. At the same time the deposed Lithuanian government managed to set up offices for Lithuanian refugees in various locations in Russia. Later, these offices were used as recruiting stations and the best address for Lithuanian refugees. The instructors were officers and sergeants in the Lithuanian army who fled from Lita. The officers were of Lithuanian origin but natives of Russia and the Lithuanian language was foreign to them. Of course, there were also many Russian officers, mostly commissars, who were sent to the division.

How the Jews reached it?

The Jews constituted the largest number of refugees who left Lita. Many were forced to return from the border because they were unable to cross it. These refugees traveled in very long caravans, in trains to various locations in Russia. I found myself in a small railway station in the republic of Moldova together with 3000 refugees. The first news of the existence of the Lithuanian unit reached me in the spring of 1942. It's worth noting, that until then I've tried several times (like thousands of other young Jewish men) to volunteer to the Red Army. However, at the recruiting station our request was responded with the routine answer:” If we'll need - we'll call you.”

On the same spring of 1942, a small unit from the division arrived to the town where I lived to acquire equipment, especially horses.

[Page 60]

By chance I stood next to them and noticed that all of them spoke Yiddish. It's clear that I immediately learned about the division and started to make plans to reach it. My request was granted in May 1942. Like me, many Jews arrived to the division from various locations in the Soviet Union, mostly from Central Russia. Many refugees, who escaped the harsh winter to warm areas, also arrived. They did not know that diseases, pandemics and famine were waiting for them there.

Every single day hundreds of volunteers arrived to the sorting camp in Bãlãceana, and from there to the regiments that were being organized.

How the Jews were accepted to the division?

In 1942, anti-Semitism wasn't felt in the division because it was largely “Semitic” and the Jews were received with joy. Even before the new recruit arrived to the office he met friends, acquaintances and sometimes relatives that he didn't know about. These meetings elevated the hearts and added a lot to the connection to the unit. The recruits went through the usual stages of recruitment at the sorting camp and sent to the units immediately.

I was sent to the artillery regiment which was at its final stages of organization. The Jews constituted the vast majority in the infantry regiments. In our regiment there was a small number of Lithuanians and a large percentage of Russians from the vicinity of Gorky, and we became friendly with them very quickly.

Where did they fight?

The division received an order to leave for the front at the end of 1942. According to the strategy of that time the division had to strengthen itself for battle by marching hundreds of kilometers in the wind and in the storm.

We were transferred by trains to the region of Tula. Our regiment camped in Yasnaya-Polyana, the country estate of Leo Tolstoy. From there we were marched, in a harsh winter and snow storms, in the direction of Oryol.

The first battle that the division encountered was near the village of Alekseyevka in Oryol Oblast. It was a completely exposed area without hills, forests or other natural shelters. The ground was frozen to a depth of more than a meter and a half. There was no way to dig and snow blocks served as improvised trenches. The regiments that were thrown into battle were overpowered in a relatively short time. Thousands of the best Jewish youth, who stormed the Nazi enemy with shouts of “Horah,” found their death in the battle field near Oryol. Within two or three weeks the division, which bled the blood of its best sons, was transferred to a second line for reorganization.

In the summer of 1943, the division operated in the same front line but with greater success. For the first time we were able to ward off the Nazis and chase them to a distance of several hundred kilometers. It's symbolic that the division ended its fighting near a small village named “Litva.”

[Page 61]

After additional months of organization and strengthening in the vicinity of the city of “Tula” (relatively pleasant months), the division was sent to a new battle zone in Vallokya-Lukistria Russa (names of places that are well known to those who are knowledgeable in the Russian-Polish wars). It was a typical marshy area. If the ground was completely frozen in Oryol, it was impossible to dig here because of the water and mud. The fighting was very difficult in this area and the losses were heavy.

From there we were sent to the vicinity of Vitebsk-Polotsk, an area rich with forests and lakes.

From there, the division was moved to the Lithuanian border and was among the units that liberated Lita from the Nazis. The division progressed rapidly and reached Šiauliai - a place where fierce fighting took place.

The last battle zone was in Latvia. A large number of nationalists SS units, who fought for every inch of land, concentrated there.

Many victims from the division have fallen in Latvia. Many of them were new recruits, Lithuanians who were recruited against their will.

After the war (which found us on 9 May, 1945), the division passed, by foot, in a victory parade from Lita to Vilna.

How did they fight?

Many Jews have proven themselves on the battlefield and received honorable decorations. There was no need to conduct propaganda among the Jews to encourage them to self-sacrifice. Sometimes, it was necessary to curb and restrain the spirit of sacrifice. Thousands of young Jews gave their lives in the Oryol fields and other locations in the war against the Nazi invader.

How the spiritual life was conducted in the division?

The commissars were in charge of the spiritual life and during the war years they have done everything to cultivate hatred for the enemy invader. There weren't any difficulties in this area - the many Jews were imbued with hatred for the enemy, more than the Russians.

There was, of course, another kind of spiritual life. In the early years you could hear “Jewish talk” coming from the bunkers, Hebrew conversations around the campfire, and Yiddish and Hebrew songs were heard everywhere. The newspaper “Ainkayt” arrived to the division and it had a section with stories about the heroism of the division's soldiers. The articles of Ilya Ehrenburg were read out aloud in the units.

Were there signs of anti-Semitism?

If there were such signs they weren't prominent in the early years. It wasn't felt in the units. Maybe there was discrimination in the appointment of commanders, promotion to a higher rank, etc.

[Page 62]

The signs of anti-Semitism began to be more visible at the end of the war. Entertainment evenings in Yiddish were forbidden. Many Jews were discriminated against during the enlistment of the core group for the Lithuanian government (1944). Anti-Semitism was particularly evident during the recruitment of new Lithuanians. Many decrees limited the cultural activities among the Jews.

Who attended the victory parade?

A few were sent to represent the division in accordance with the scale that was set for all the units. If I'm not mistaken, our artillery battalion was represented by 3-4 sergeants. Later, they told us about their experiences in the historic parade in Moscow.

What did the Jewish soldiers find in the Lithuanian towns when they returned from the front?

During the entire war the soldiers of the division didn't receive vacations because there was nowhere to go. When the fighting ended, each one of us hurried to his town to search for family members who survived the war.

The great destruction and a personal Holocaust - welcomed them. One from the town and two from the area - who remained alive - were only able to tell how and where they were killed. At that time there wasn't a stable civilian rule, and the released fighters used the opportunity to avenge the murder of their family members as much as they could, and indeed, they've done a lot in this area.

The soldiers, who were released from the division, were offered various respectable positions in liberated Lita. I, for example, was offered to be a prosecutor in the town of Ukmergë. However, the soldiers opted to concentrate in Vilna. Their main concern was the Jewish society, the Jewish environment and family reunion. At the same period the residents of Vilna and the environment, who were Polish citizens until 1939, were able to leave Lita. Many Jews, myself included, left Lita with these citizens and found their way to the “Bricha” [escape] organization which was already operating in Vilna. Regrettably, not everyone who wanted to leave was able to do so.

[Page 63]

Translated by Sara Mages

The greatest dilemma in the ghetto was - how can we get to the partisans. They didn't think, and didn't want to think - how life will be among the partisans, would they be able to get along with the Gentiles, the officers and the forest. Yet, how can we get there? The forest is far from the town, the ghetto is guarded by Lithuanian and German soldiers and closed on all sides. There's no exit from the ghetto to work. The few workers who leave are counted when they exit and when they return, and they can't infiltrate from the town to the forest. How can we reach them when the Gentile environment is hostile and the partisans are located in the forests not in the villages? The few who went to them were killed on the way. It's impossible to leave the ghetto in a partisan way and ordinary people aren't accepted into the ranks of the FPO[1], that is to say: 1) A party member, 2) A bachelor, 3) Married without children, 4) Equipped with a weapon, at least with a pistol. And the main thing, also here you need vitamin F (favoritism).

Those who reached the forest were accepted as full-fledged members therefore they asked to go into action. The desire for revenge blinded their eyes and dulled their senses and they went out to dangerous actions. There was a real devotion among them. The Jews were among the first who volunteered, and for the most part also the initiators.

The women opted to go into action than working in the kitchen or in the sewing workshop. Berta Dinerstein, from the village of Kalofi, refused to work as a nurse in the field hospital. During the siege, when she went into action against the Germans, she noticed that a partisan (a Gentile) left his submachine gun and fled from his position at the front line because of the pressure of the enemy's bullets. She left her position with a submachine gun in her hand, and warned him that she would kill him on the spot as a deserter if he does not return to his place. The partisan returned, and the attack was pushed.

This young woman used to come to the town at mid day (Vileyka and the surrounding area) dressed as a peasant and a pistol was always hidden in her clothes. She took out Jews from the towns, obtained “Aryan” papers for Jewish boys and received leaflets, which were printed by Jews in German printing houses, for the partisans. These leaflets had a great impact on the local population. In the end, she was attacked by a Gentile partisan and when she fought for her purity he shot and killed her.

>A second young woman, Feigel from the village of Kornitz, used to come to the Gentiles at night to ask for bread and potatoes for some Jewish families who were in a difficult situation in the forest. The Gentiles knew her and from time to time gave her food. She was captured by the Germans in one of the manhunts and was taken to village of Starina where the Germans' headquarters was located. hey tortured her severely and tried to get her to admit that the Gentile villagers give food to Jews who lived in the forests. The villagers watched her torture with anxiety because their life depended on her words. She was tortured for three days, but she didn't confess. She claimed that the Gentiles chase them out of the villages and beat them mercilessly, and the only food that they have is what they steal from the fields or given to them by the partisans. When they realized that the method of torture wasn't helping

[Page 64]

they began to coax her and promise her various things. They brought her to a Gentile who already admitted that he gives food to the Jews of the forest, but she said that he was lying, that he was one of the cruel farmers who make trouble to the Jews. Then they tortured her until her pure soul expired.

Her death caused unusual excitement in the village. The Gentiles couldn't understand how a woman was able to withstand her tormentors and decided that she was one of the saints who were masquerading as humans. They took her body in secret, buried her in the village cemetery and prayed on her grave.

A group of partisans (five), David Kopoliwitch from Vileyka among them, left for the central train station to destroy the railroad tracks when two trains were to meet at that point. For a whole day they sat waiting in a deserted and isolated wheat warehouse a few kilometers away. At night they arrived to the place at the designated hour. David had to tie the brick, which was full of dynamite, to the railroad tracks and return. The others had to stand on guard and protect him with their weapons. To this day no one knows how a shot was fired from the machine gun that was hanging on him. At the same moment shots, which were fired from rifles and machine guns, began to thunder throughout the area and rockets lit up the sky. The four partisans began to crawl through the bushes and returned to the deserted warehouse. They were sure that David was killed when the Germans spotted him. However, David lay all the time without moving. When the shooting stopped a bit, he crawled slowly slowly from the area and returned to the warehouse a few hours later. When he told his friends about the incident they couldn't forgive him. Since this was the first action that he was responsible for, he decided to stay for another night and carry out the operation on the next day. The next evening, when they left the warehouse for the railroad tracks, a black cat crossed the road. Then they decided that it was an unlucky action. “We aren't going to take a risk,” they said. All the requests didn't help. They stuck to their opinion - “we aren't going and we don't want to participate in this operation.” David saw it as an attack on him and especially on his honor as a Jew, so he asked who would volunteer to go with him. A second young man, a Jew from Minsk named Nisenebitz, said that he was willing to go. It was decided on the spot that both of them remain in the warehouse and perform the mission the next night and the rest will return to the base. On the next day they placed the explosives and returned safely to the base. As a result, two trains were destroyed, the rail traffic was suspended for two days and the Jewish commander won the respect that he deserved.

Avenging Partisans

This is what I know about partisans from Olkeniki. A young man named Eliyahu Leib Katz, who was 18 years old, escaped to the forest with his sister Leibka (Ahuva). He was located in “Naliboki Pushcha” and was one of the most famous avengers in the area. He was an excellent fighter and had a lot of initiative and courage. He took revenge on those who collaborated with the Germans and carried out operations in the villages. The Gentiles talked about him as if he was a “demon.” He took revenge without mercy. When he learned that a Jew, who was staying with a Gentile, was in a difficult situation or about a village that refused to give food to the Jews who were hiding there, he first warned them. He arrived to every location by himself, and when they didn't listen to him he punished them by killing them and burning their property. The Gentiles responded to his requests since his name was known throughout the region.

He fell in one of the blockade's bloody battles with a machine gun in his hand.

A second partisan named Avraham Tike (he survived and lives in Israel), who was also in “Naliboki Pushch,” took his revenge after liberation. On the first day of the massacre in Eshishuk he was in the last group to be executed. After the barrage of gunshots he fell into the pit shocked and wounded. As he lay in the pit he found himself among the bodies of the dead and dying, and began to feel pain in his injured leg. He felt that he was still alive even though he lost a lot of blood.

He heard the voices of the Lithuanian policemen who were planning to pour chlorine and soil into the pit. Meanwhile it got dark. When the policemen were busy drinking Vodka, Avraham pulled himself from among the corpses and slowly crept out of the pit. He fled to the barn of a local farmer and hid there, he wasn't able to go farther.

On the next day he saw through the cracks how the remaining Jews of Olkeniki and Eshishuk were being led, and how mothers pushed their children's strollers to the killing pit.

After liberation, in 1944, Avraham came to Olkeniki. On Sunday, when the Gentiles went to their church, he met on a street corner a “Shkotzim” [Gentile] who was one of the murderers in Eshishuk. Avraham ran to the police. By chance, the policeman on duty was a Jew that he knew from the village of Dekshenia. He asked him to give him a gun so that he could arrest the “collaborator.” He followed the Gentile to the youth club that was established by the Soviets. When he entered the club he threatened with the gun in his hand and ordered everyone to leave, one after the other, because he was looking for “collaborators.” The “Shkotzim” started to escape and when the killer came out of the door and started to run. Avraham chased him and killed him on the spot. Avraham was arrested but was released after lengthy negotiations.

Twenty young people from the town joined the partisans, but only two of them survived - Leibka Ahuva) Katz and Teik. Leibka worked as a nurse and also went out to action with a weapon in her hand. She, for example, pulled down telephone poles and railroad tracks, and participated in raids to get food from the rural population for the partisans.

[Page 66]

The partisan headquarters in Naliboki Forest was in Jewish hands, the Bielski brothers. There were several religious families and from time to time the slaughterer from Voranava butchered an animal and provided them with kosher meat. They set up a minyan on the Shabbat and on the holidays, and conducted a “seder” on Passover. Several Yeshiva students from the area (Radon) also gathered there. Among them was a teacher from Olkeniki who was nicknamed “Tel Hai.” He was a member of “Betar” and instead of “Shalom” and “Boker Tov”[good morning] he said “Tel Hai” to everyone in the forest. He survived and today he's in Israel (his name is Itzkovitch).

A partisan, named Chaim Solel, knew the whole area. He managed to take out a group of FPO[1] from the Vilna Ghetto to Rudniki Forest. In the forest he served as a translator (to Lithuanian) and a guide. He also attended the meetings in the headquarters. In each village he organized groups of trustworthy Gentiles who provided information to the partisans. More than once the partisans were saved from attacks thanks to the information that they provided on the movement of the Germans in the area.

A second partisan, named Mitzke Basmateski, who was also from the area (he was born in a village in the area), took many partisans from the Vilna Ghetto to Kodnidena Forests and helped them to obtain food and weapons.

A third partisan, named Yisrael-ke “Der Vilner,” (he got married in Olkeniki), had a facial appearance that didn't give him away. He used to come to the ghetto in the middle of the day dressed as a Gentile, and when people left for work he joined them and led them to the forest, to the partisans. In fact, every action of these young men entailed a mortal danger. Their commanders often abused them. When one of them excelled in action, they searched for dangerous operations for him so he would be killed. Most of the best young Jewish men fell because their commanders wanted to get rid of them.

[Page 67]

Translated by Sara Mages

The Germans, as is well known, were especially cruel and used to organize the largest “Aktziot” on Jewish holidays. The children were first to be executed because the Germans considered them the new generation, the young force that can fight for the Jewish people.

And here is a story about one of the girls from Olkeniki. Her name was Yoheved z”l and she was the daughter of Rabbi Kalman Ferber. The girl, who was about seven years old, was very beautiful. On the holiday of Purim, which was designated for an “Aktzia,” the residents of the ghetto (Vilna Ghetto), who wanted to give the children a sense of security, organize a party for them. Yoheved z”l dressed as Queen Ester. When she returned home from the party, as soon as she got home, the Nazis came and abducted her… and she disappeared without a trace. After the war the unfortunate parents, like other surviving parents, tried to find her in complete faith that she was still alive (after all, they didn't witness her death), but without any results.

Years have passed and the wound didn't heal. When the parents (who are very religious) realized that if Yoheved z”l was alive she would be about 25 years old, they decided to honor her memory and give her a “wedding.” The parents asked a scribe to repair an old Torah Scroll that survived the Holocaust. They covered the Torah with a velvet coat and inscribed on it a dedication to Yoheved z”l who was abducted by the Germans (they made sure not to mention that she was killed because they didn't know for sure that she was dead). The bereaved parents donated the scroll to their synagogue.

The ceremony was magnificent: the guests were invited to the parents' home, the scroll, which was wrapped in a coat and covered with a parochet, was placed on a table and a memorial candle was placed on each side. The parents were blessed with “Mazel Tov,” as if it was a real wedding. The excited parents were happy with their deed even though the wound was reopened. The guests sat around the tables, men and women apart, ate refreshments, sang and were happy as in a real wedding. Then, the holy book, which was placed under a chupa, was led through the neighborhood's streets. The crowd followed it and the young danced in front of it and sang incessantly. When they arrived to the synagogue the Torah Scroll was placed in the Holy Ark in a special festive prayer. Meanwhile, the women set the tables with drinks and all the best, the men helped them and there was a lot of joy.

There has never been a wedding similar to this wedding. The parents did everything they could for their missing daughter and lit a memorial candle in her memory.

|

|

JewishGen, Inc. makes no representations regarding the accuracy of

the translation. The reader may wish to refer to the original material

for verification.

JewishGen is not responsible for inaccuracies or omissions in the original work and cannot rewrite or edit the text to correct inaccuracies and/or omissions.

Our mission is to produce a translation of the original work and we cannot verify the accuracy of statements or alter facts cited.

Valkininkai, Lithuania

Valkininkai, Lithuania

Yizkor Book Project

Yizkor Book Project

JewishGen Home Page

JewishGen Home Page

Copyright © 1999-2026 by JewishGen, Inc.

Updated 4 Mar 2014 by MGH