|

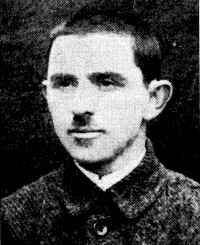

[“village elder”]

|

|

[Pages 245/246]

by David Sadeh

Translated from Hebrew by Miriam Bulwar David–Hay

Donated by Anne E. Parsons – Department of History, UNC Greensboro

Petliura's people[1] frequently visited the town. The soldiers were housed in the homes of residents, which were requisitioned according to need. The Jews were scared of them. The Petliurovists were quite wild, and their weapons gave them added audacity. Neither were they careful with their weapons, and this lack of caution almost caused a disaster in the town. And this is what happened in that incident:

Petliura's soldiers stopped in the town, the people of the White Guard[2], dressed well, in the dress of the nationalist Cossacks. They filled the entire market square and in the middle placed a heavy machine gun, “Pulemiyot[3],” with a unit [of soldiers] that serviced it.

Suddenly a loud explosion from heard from the command post, which was housed in “Zlota–Polska.” All the residents quickly hid inside their houses, out of fear of what was coming.

Hutman, the Petliurist “officer,” decided immediately that the Bolshevik Jews had thrown a grenade at the command post, and came up with a plan to render judgment on the civilian population. He turned to the town council with a threat that if they did not turn over the assassin within a certain time, he would aim the machine gun at the council buildings. A search began in the town to find who had thrown the bomb. To the good fortune of the residents, it became clear that the soldiers of the guard, who were equipped with grenades, had behaved carelessly. One of them put a “bottle” [grenade] on the table. The bottle rolled off onto the floor and exploded without causing damage. The soldier had the courage to reveal the deed, and thanks to that, a catastrophe was averted for the Jewish residents of the town from Petliura's people, who knew no mercy in their meetings with the Jews, and much blood was spilled at their hands at other opportunities.

Most residents of the town were counted among the ranks of the poor and middle–class, and for this reason did not fear the entry of the Bolsheviks to the town. They had nothing to lose. Everyone also knew that the Bolsheviks behaved well to the Jews, and among them were many Jews, men and women, who did not hide their Jewishness at all. And there were times when the residents would even receive food items from the Bolsheviks, when they had enough.

On a scorching summer day in 1917, the Polish front was breached and the Bolshevik army flowed through the town in the direction of the bridge over the Horyn [River], on the road leading to Rivne. How did the Bolshevik army look? Was it even possible to call them an army? It is hard to say. The soldiers were dressed in tatters, in women's clothes, sometimes even in furs (even though it was a blazing summer). The military equipment was also worn out. The Jews received the Bolsheviks well and served them by distributing cold water to the tired army, which flowed by the thousands along the entire length of the road. The army dallied in the town and was accommodated in houses [of residents], where food was cooked for them and their clothes were washed for them. In their free time, many chatted in friendliness with the people in the homes about everything that was happening all around them, and more than once they discussed the Jewish question.

In the town was a road and also a bridge over the Horyn River on the road leading to Russia. Therefore Tuchyn functioned as a transit point for armies and felt every change on the front. And like all the towns that lay on the transit roads, Tuchyn also suffered from every movement on the front. The Poles, who had been subordinated under the Russians and under the Germans–Austrians, organized and fought for the freedom of their land and the establishment of an independent nation. Mainly they fought on the eastern front against the Bolshevik army. The Poles would manage to advance to Kiev[4] and the Red Army would attack and send reinforcements and chase them back to the depths of Poland. I remember one night of a Polish retreat, and that was the night of Yom Kippur.

In the evening, we heard loud exchanges of gunfire in the area. Someone said the Poles were retreating and the Bolsheviks were advancing. The Jews were scared to gather for prayers in the synagogue. And therefore the Yom Kippur eve prayers were held in small minyans[5], in private homes, with the windows and doors blacked out. As if that would ensure the safety of the residents. The prayers were said despite being under a heavy barrage of gunfire because no one knew what the next moment would bring. The prayers ended and the worshippers each went back to their own homes. Suddenly there were knocks on our door and shouts in Yiddish and Polish. We opened the door and saw Polish soldiers with a large group of Jews who were being led to repair the bridge so that the retreating Polish army could cross it. My father was also conscripted [to repair the bridge] and went despite the holiness of Yom Kippur. There was no choice, and all that night the Jews worked at repairing the bridge.

After the retreat, the Poles placed landmines on all the roads, and it must be noted that despite the work in the dark, all the Jews returned home safely, escorted by the soldiers, who transferred them between the mined areas.

[Pages 247/248]

As stated, Tuchyn was passed from hand to hand, and shots and battles near the town were not rare things. The same morning the Bolsheviks who were staying in the town announced that a battle was likely to take place in the town, and they advised the citizens to leave while they still could. The Jews were already used to battles and knew what to prepare. First they prepared food, baked bread and cooked potatoes, took a few clothes, and were ready to set off. Where did the Jews go? To the synagogue, which was a strong brick building, and in it there was a feeling of safety. On the way, we passed next to the house of Zalman Shatz. He saw my mother passing with two children and a maid and invited us into his house. But Mother preferred to go to the synagogue, and it was good that she did, because the same day soldiers broke into the Shatz house and plundered it thoroughly. From the synagogue we continued on to a place considered even more safe: the cemetery. Many residents of the town arrived there, in this way distancing themselves from the main road, where the military forces were moving.

The women and the children settled themselves between the stone tombstones, and they each loosened their bundles and feasted to their hearts' content. A real “picnic.” But this time of rest did not last long. The bullets and mortars arrived also at the cemetery. We moved further through the Ukrainian suburb past the “Zamd[6],” which was also far from the main road, until the fury would pass.

Following the civil war[8] numerous gangs were formed. A minority had a political orientation, and most were gangs of robbers and bullies.

The Jews in Ukraine suffered greatly from these gangs. And many were the incidents of robbery, rape and murder. The Jews of Tuchyn initiated and established an organization for self–defense, purchased weapons, rifles and guns, passed training, and were ready to meet the gangs face to face, not with pleas or with anxiety, but with ready weapons. The gangs were not prepared for resistance by Jews, and after a number of attempts to attack that did not succeed, they avoided trying to harm the town. Special and unusual for those times, there was cooperation in the self–defense by the residents of the Ukrainian suburbs, with Anton Kornin at the head. Of course, this cooperation only strengthened the defense of the town, and many gangs would not get close to it.

Members of the defense, most of the youth of the town, would pass training and would take turns keeping guard. Some would go out in shifts to the outskirts of the town in order to guard the entrances to the town, to prevent the penetration of gangs or cells planning to rob the shops and houses at the edges of the town.

I remember once that the patrol unit of a gang drew close to the city. A short battle broke out and the head of the gang, “Lalka,” was killed. The gang was very strong, and was based in the area of the village Shubkiv. In the city there was great fear of attacks in the name of revenge. That fear grew with the arrival of information that the entire brigade from Shubkiv was heading for Tuchyn, which was told by a carter who had come from Rivne. He had seen the large funeral that was being held for the head of the gang, in which thousands of Ukrainians participated. But the defense force heard and acted, and deterred the gangs from attacking the town. They [the Ukrainians] buried the gang leader in the cemetery in the village of Shubkiv, and years later they showed me his ornate grave. From the self–defense organization, I remember Avraham Stoler, who had in his possession a rifle and would sometimes allow me to press the trigger.

The defense organization would prevent [trouble at] market days, “fairs.” In those days, they would close all the roads to the town on the regular market days, to prevent the entry of rioters. With the end of the wars, an order was published that stated: Every weapon must be handed over to the authorities, otherwise a heavy punishment can be expected for any civilian found in possession of a weapon. The Jews returned their weapons, given that they could not do otherwise. But the spirit of defense continued to drive the residents of the town of Tuchyn, and after every incident in which a Jew was attacked by a Ukrainian or a Pole, the Jews would heroically respond twice as hard. This was especially dangerous if a skirmish began on market day, a “fair,” because there was then in the city a large concentration of peasants, some of them drunk and easy to provoke.

I remember that a drunken Polish “osadnik[9]” was walking through the market, wobbling on his legs. A light rain was falling and the ground was wet and slippery. The Pole slipped, fell in the mud, and got dirty. What did he do? He went into the store of Zisha Batt, took a piece of material without asking permission, and started wiping the mud from his clothing.

Although there was a great fear of the osadniks, who were trained military men as well as the possessors of great insolence, and who were also supported by the authorities without any limits, Zisha Batt took the Pole and pushed him out of his store. The store was quite high [off the ground], and the Pole who was ejected was quite surprised and was not expecting that a Jew with a beard would dare to throw him out. He flew out and rolled several times. Filled with anger, he drew out a knife to stab the Jew. To his aid came some of his friends, but the Jews also did not hold back, and they [the Poles] received such a dose that all the enjoyment they had from the market day was forgotten by them. They quickly hitched up their horses and fled, but on the way to their village they passed the “Zamd” and there they wanted to settle their account with the Jews, because they thought there was another kind of Jew there [namely, one that would not fight]. But there they received another helping of vigorous blows, and with difficulty they left the town, beaten and injured.

The Ukrainians, in incidents of fights with Poles, remained neutral and enjoyed watching from the sidelines how the Poles they hated so much would receive blows from the Jews.

The Ukrainians themselves also more than once received blows from the Jews, and they would lower their heads before them. I remember several times when a Ukrainian would speak impudently and start to curse that my father would respond to him one for one and would add: The time has passed since your Petliura was around, he is not here anymore, and no one is scared of you. And it happened more than once that an altercation would break out with the Ukrainians and the Jews would respond with full force. And this would

[Pages 249/250]

become known quite quickly all around the area. All the Poles and the Ukrainians knew that it was not worth their while to start anything with the Jews of Tuchyn, because they [the Jews] would not make concessions, and in this way many altercations were prevented.

Once a gentile came in to the store of Tanchum Wallach to buy materials. It was a market day; the whole city was full and bursting with the wagons of gentiles. The gentile decided that he desired some material without paying. He chose a piece of material and secretly hid it inside his clothing. Manya, the wife of Tanchum, tall and red–faced, saw what the gentile had done and without warning slapped him with all her strength. The stunned gentile fell in a faint, either from the force of the blow or possibly from the great surprise that a Jewish woman could hit like that. The incident was quite unpleasant and a very large crowd gathered, thinking that he had fallen down dead. After some time, the gentile awakened from his faint and fled in shame, upon perceiving that it was not easy to steal.

Boruch Motchar, a tiny grain merchant, went to a village to buy grain and was met by a known Ukrainian brute who started arguing with him. Boruch replied and the gentile grew angry and beat the Jew with murderous blows. The Jew could not stand up to this gentile, who was strong and who had been given added strength by alcohol. So he fled from the fracas with noticeable black eyes. The gentile was not satisfied with this and promised to come with his friends to his [Motchar's] street and to show all the Jews who were neighbors of Boruch Motchar what the power of the gentiles was. Boruch quickly went home to warn the Jews of the danger awaiting them. The Jews took and prepared tools for hitting, hoes, handles of shovels, and waited, out of concern that the Ukrainians would act to realize their threats. And indeed they did act. Within some time, a number of drunken and brutish Ukrainians appeared in the street and began cursing the Jews, their mothers and their religion. The Jews knew they could not prevent a skirmish and answered them one by one, and then the gentiles began chasing after the Jews and hitting them. The Jews had been waiting for this and appeared on all sides, and began beating them with murderous blows. Humiliated and injured were the gentiles in the street. Fear fell upon the Jews, in case the police would come and arrest them. What did they do? They informed the police that the gentiles had gotten drunk and had beaten each other up. The gentiles were embarrassed to say the Jews had beaten them, but they remembered the lesson and from then on did nothing more to provoke the Jews or to harm them when they appeared in the Ukrainian street.

The “prizivniki[10]” were young men who were waiting to have a health test before being drafted into the army. The examination committee had its seat in Tuchyn and it was to here that came all the young men from the city and from all the villages around it. Thousands of young men would come to the town from remote villages. Turning up for conscription as a “prizivnik” was for many “shketzim[11]” an outing from their village and a big holiday in their lives, and they celebrated by drinking themselves into inebriation and rioting in the streets of the city. The residents of the “Zamd” suffered especially hard from this, because there sat the “prisodsteva,” the medical committee. The police did not interfere in the pranks of the “prizivniki” and simply looked at them through their fingers. What did Chaim Shprintz do? Upon learning that the city officer [the police chief] was sitting with his family and his guests to drink tea, he took a brick and threw it through the window. Of course, all the police came running. Chaim claimed that the prizivniki had thrown the brick. The police saw that the privizniki were getting carried away and prohibited the sale of alcohol to them and also [prohibited them from] running around in the streets of the city.

In this way the brave Jews of Tuchyn lived their lives without fear for many years, ready to defend their lives and their honor, until the German murderers came, and in collusion with the Ukrainian nationalists, broke and destroyed the dignity of the Jews. Using various tactics, they killed off the leaders of the Jewish street from time to time and weakened the strength of the group. But when the bitter day came, the Jewish community in Tuchyn awakened. And when they saw that they [the Germans/Ukrainians] wanted to exterminate them, they did the best they could to damage their property so that it would not fall into the hands of the haters, burning everything that could be burned. Some endangered their lives so as not to fall into the hands of the gentiles. Many hundreds fled to the forests. Most of them were annihilated without any protection against the stronger force of the Ukrainians. A few hid, [and] some joined the partisans, who endured the days of the Holocaust and managed to emerge from the valley of death.

It was hard for the Children of Israel to make a living. The means of earning an income were limited and many were closed to Jews altogether. So the Jews sought out new sources for making a livelihood. One important source of income for many Jews was the production of “samogon” – an alcoholic beverage made of potatoes or rye flour, which was manufactured in secret from the authorities and was sold to the peasants. A manufacturer of samogon could expect a lengthy prison term, and the seller could also expect a fine and imprisonment. And despite all this, many Jews were occupied in this livelihood. The production of samogon was mostly organized in an isolated rural house or in a grain storage barn, in a threshing room, in an enclosed basement that was sealed off and isolated, in the forests, and similar. In such a place they would work until their traces were discovered and then they would leave and move to another place.

The police were mostly bribed and turned a blind eye, and sometimes would inform the people in advance, who would leave the place, and the police would then confiscate the equipment.

The samogon producers had excellent horses, which would compete against the police horses. And more than once when they felt that the police were following them, they would make an “escape,” and the police would not be able to catch them. And in the event that the police did catch them, they would escape from the prison building.

In one incident, the head of the producers was put on trial and disappeared from the courthouse, and for a long time they searched for him, and a large prize was announced for his capture. Once this elder of the family was caught in the synagogue on the Sabbath in a surprise search by the police, apparently as a result of someone informing on him. The head of the district came to see the man who had caused such a commotion for all the police in the district.

Translator's Footnotes

By Shalom Cholevski

Translated from Hebrew by Miriam Bulwar David–Hay

Donated by Anne E. Parsons – Department of History, UNC Greensboro

The testimonies are those of Yaakov Tchubok, Natan Shulman and Miriam Shvartzman–Kouts, collected by Nesia Reznik (“Moreshet[1],” pp. 360–363). The rest of the testimonies[2] are from the archives of Yad Vashem[3].

The town of Tuchyn lies on the left bank of the Horyn River, 26 kilometers from the district city Rivne.

In Tuchyn before the war lived Ukrainians, Poles, Germans, and Jews. Like in all the towns of Israel[4], the Jews in them were occupied, some in commerce and some in trades. Until the outbreak of the war, relations between the residents appeared to be in order. The fate of the Jews of Tuchyn, upon the outbreak of the war, is told in the following testimonies.

“The Russian–German war broke out on the 22nd of June, 1941, and after a short time, the Germans were already in our town (this was at the beginning of July).

The Ukrainians went out to welcome the Germans. I remember that they laid out a red carpet and threw flowers towards the German soldiers. Among those welcoming the Germans were: the family of butchers (that's how they were called in the town) the Tzemti family, Ivan Stendik[5], and others. They called out cries of welcome to the Germans and shouted,‘Death to the Jews.’ The Germans stationed themselves in the city. Ukrainians were appointed to high positions: Rytchak the lame entered the police force. Stendik

[Pages 259/260]

was named deputy mayor, and his brother Vasil, who in the time of the Russians was active in the Communist Party, worked in the town administration and excelled in many activities.”[6]

“The Ukrainian population received the Germans with enthusiasm. They helped the German army enter the city. They placed boats at their disposal to help them cross the Horyn River.”[7]

“The Ukrainians started acting already on the first day of the German entry [into the town]. They went into the houses of Jews with large sacks in their arms. When they left, the sacks were full of Jewish property. No one resisted them. The Ukrainians abused and cursed the inhabitants of the homes … Three days after the entry of the Germans, German soldiers broke into the house of Chaim Shprintz. This Jew had built a synagogue in his yard. In the synagogue were six Torah scrolls. The Germans took the Torah scrolls out from the Holy Ark.[8] They threw them on the ground and set them alight. They promised the Ukrainians that they would liberate Ukraine and it would be an independent country. In the afternoon, the Ukrainians went through the houses of the Jews, took all the men outside, and an order was given to build a gate for the Ukrainian soldiers who had enlisted to assist the Germans.

Every one of them was equipped with a baton and they shouted at us: ‘Stalin is already gone and you too, Jews, will soon be gone …’

I returned from work. Next to the house stood a wagon. A Ukrainian gentile, Andrei Dubytch of Sinne Street, went from house to house, collected the property, and put it on his wagon. His son Mikhelke, age 17, and his 12–year–old daughter sat in the wagon and guarded the property. This Andrei beat every woman who happened to cross his path. He went from house to house.

I came and saw the sight. My blood boiled inside me. I approached the wagon. I lowered part of the harness and began hitting Andrei and his son. They did not expect a reaction like that and fled. They left all the full sacks that they had loaded onto the wagon.”[9]

“After a short time there was a pogrom in Tuchyn. The pogrom was organized by young Demien Rytchak. Of course Dmitri Prokof [Prokop] also knew very well what was about to happen and was in on the doings. That night rioters broke into the house of Sioma Spozhnik. They murdered his wife Teivel. Her infant son, who was lying next to her on the bed, remained alive. What the fate of Sioma was I do not know. I know that the baby was given to a neighbor who was nursing.

Even before the ghetto was set up, all the Jews were ordered to wear a yellow patch on which there was a Star of David. Two patches were worn, on the back and on the chest. It was prohibited for Jews to leave the city. Anyone who breached the order was taken and executed. Hunger forced the Jews to breach the order. The Jews would take risks and go out to the villages, in order to exchange clothing and items of value for bread. Rytchak the lame kept watch over the Jews; he was a policeman. Once he caught me and my mother. He hit my mother with murderous blows. I shouted out loudly. He aimed his rifle towards my mother. I panicked even more and shouted even more loudly: ‘This time I won't shoot you because of the boy! If you get caught again, then I won’t have any mercy!’ That Rytchak was once our neighbor. That time we returned home safely.

A Judenrat[10] was chosen. At the head of the Judenrat stood Getzel Shvartzman and his deputy was Meir Himelfarb. The Jews received an order to bring all the furs and gold jewelry to the Germans.

Those responsible for carrying out the order were the Judenrat. It was announced that any Jew in whose house gold jewelry or fur was found would be shot.”[11]

“On the 4th of July, Thursday, the Germans conquered Tuchyn. On the night of the 6th of July, 1941, a group of Ukrainian policeman went out, armed with knives, axes, and planks in which nails had been stuck, and carried out a pogrom.

In that pogrom, around 60 Jews fell. Ten died after suffering greatly and more than 20 injured recovered later. The Ukrainian doctor Humeniuk did not want to give medical assistance to the Jews. He announced that the Jews had lived enough.

A few days after the pogrom, the Ukrainian police ordered the Jews to collect bedding, utensils, plates and spoons. In every house, only one plate and one spoon were allowed to remain.

The Jews, in their wish to live in peace with everyone, tried to satisfy their desires, and especially not to cause any provocations and especially to defer ‘aktzias[12]’ …

The Jews of Tuchyn began fleeing to Rivne, thinking that in a bigger city there was no place for unruliness. The Ukrainians stopped the Jews on the roads, robbed them, and executed them.

Four weeks after the entry of the Germans, there came to Tuchyn the German commandant Grabner. Grabner levied a ‘kontributzia[13]’ on the Jews, and ordered them to hand over the cows, the horses, the wagons, bicycles, machines, furniture, clothing, and so on.

During the entire time of the German occupation, the Germans and the local civil authority, and also the Ukrainian residents, even though they did not have any official ties with the authorities, would place orders incessantly for objects and things of value.

The Jews from the whole town were [held] responsible if there was discovered among them a Jew from another city. The Judenrat in Tuchyn bribed, as much as possible, the police and the peasants in order to ransom the Jews who fell into their hands.

In Tuchyn there was a Ukrainian medic, Humeniuk, and a doctor, Dr. Bortnovsky. Humeniuk was a bad man and a hater of Jews. Dr. Bortnovsky was a decent man. The Ukrainians said that if they gave help to injured Jews they would be punished severely.

Despite the threats, Dr. Bortnovsky gave assistance to wounded Jews. He helped the Jews through all the difficult times. There was [also] a merciful veteran nurse in Tuchyn. Her name was Genia. She was Russian. She also helped …[14]

[Pages 261/262]

There was in Tuchyn an engineer by the name of Gross. I do not remember if he came to the town from Warsaw or from Lodz. In the town there were around 10 factories for processing skins [leathers]. Gross understood that it was very important that the Jews would work. He traveled to the ‘Gebietskommissar[15]’ (the area governor) and obtained work permits for all the men from the age of 16. He operated all the factories and took care that every Jew would have a regular place of work. The factories supplied quantities of leather products. The Germans were interested in this product and this perhaps was one of the reasons the ghetto in Tuchyn continued for so much time after they killed the Jews in all the surrounding towns.

I worked in a group in which there were five men. Our manager was Nachum Balinski. Our work was special in its nature: the preparation of firewood for the Germans.

We had the opportunity to supply firewood to all the Jews in the town. We would also sell wood to the Ukrainians in exchange for bread. We would supply bread to the Jews. We would chop the wood in the Pustomyty forests (around 12 kilometers from Tuchyn).

The Gebietskommissar was Koch[16].

One day Koch went to Gross and said to him: ‘Even though you are a Jew, I permit you to remove your yellow patch.’

‘I am a Jew and the law for me is the same as the law for all the Jews,’ replied Gross, and did not remove the patch.”[17]

“In the summer of 1942, across almost the entire territory of Volhynia, ‘Judenrein[18]’ aktzias were carried out. Jews were still living in Tuchyn, Zdolbuniv, Mizoch and Ostroh. In the summer of 1942 talk began that in the forests there were partisans, and the Jews sought ways to make contact and to establish ties with them. A Pole was found who said that the partisans would not accept people who did not have weapons, and that he could supply weapons and make contact with the partisans. To that end, the Jews collected a great deal of money and gold. The Pole took the money and was never seen again …

My brother David Shvartzman, Yitzchak Portnoy, Ludvik Gross, Aharon Marakish, Nissel Zilberberg and other young men began searching for a way to [reach] the partisans. In the village of Richytsia from time to time Russian paratroopers would land. Once I saw with my own eyes that a fire was lighting up the night and paratroopers were descending. Mostly the fate of the paratroopers was bitter. Many of them were caught and executed. The Ukrainians would deliver them to the hands of the Germans.

The young people whom I mentioned above began to take an interest in who was looking after the paratroopers. It was assumed that near the place there were people who had contact with the paratroopers.

One day Vornitski came [to us]. He was Russian. We did not place great trust in him. Vornitski said he was in contact with the partisans and was prepared to act as the liaison between the young Jews and the partisans. After much hesitation, it was decided to take the risk. Each day, young people (around 50 people) would leave Tuchyn to chop down trees in the forests. Nachum Balinski was the brigadier in this group … Talks were held with Vornitski. That day, the Judenrat doubled the number of people leaving for the forest. My two brothers, David and Liova, also went out that day to chop trees in the forest with Vornitski. It was agreed that someone from the partisans would wait for the young people and would lead them to their camp. The young people went out to the forest. They worked until the late hours. No one came. Disappointed, the young people returned to their homes.

The situation in Tuchyn worsened. Refugees would arrive every day in Tuchyn. Because about our city, legends spread: A town without a ghetto. Jews work and live. The number of Jews is growing. There were already 6,000 souls (Jews) in Tuchyn …”[19]

“An order was given to establish a ghetto. We had to leave the place and move to the area of the ghetto, which was in the center of the city. We moved some of our clothing and property to the center and stayed living in our house until the order would be given to move. One day I got up in the morning, [and] Mother sent me to buy milk. Suddenly I saw outside, in every corner, Ukrainian police. I ran home and told my mother: ‘Mother, trouble is coming our way.’ I told her what I had seen in the street. We closed the door of the house and sat down to eat breakfast. Through the window we saw armed police moving around the house. I panicked greatly and told my mother: ‘Mother, they're going to kill all of us.’ Mother calmed me and said, ‘Nothing will happen. They'll take us to the ghetto.’

I left the house and went into the house of Itche the blacksmith. On the way I saw Itche's son, Hershel, running away and Ukrainian police chasing after him. They shot him. The bullet hit and the youth fell, swimming in his own blood …

I panicked and returned home. Police came in to us and ordered us to go to the ghetto. We gathered up our bedding and the rest of our belongings and together with the other families who lived near us we walked to the ghetto. The things that we could not take with us we told our neighbor to take for herself. At the gate of the ghetto stood Aharon Kuzion. He told us: ‘Fools, they're digging pits here. People are thinking how to get out, and you're coming in.’ I burst out crying. I was not the only one. The whole ghetto was weeping. That was two days before Yom Kippur …

A rumor spread that at night all the Jews would be taken out to the Kotovsky woods. There four pits had already been prepared. A gentile came and told of this. Around the ghetto, a fence made of planks of wood was set up. The gate of the ghetto was next to the house of the Zeitchik family. On the other side the ghetto bordered the cemetery, which was on a hill. On that hill, outside the area of the ghetto, were concentrated the [Ukrainian] police and the Germans. Everything that transpired in the ghetto happened in front of their eyes, [and] they could shoot from the hill straight into the ghetto …

There was running around inside the ghetto. People did not know what to do and the time was passing. Meir Himelfarb and Getzel Shvartzman gathered the Jews into the synagogue and told them: Jews, do not go like sheep to the slaughter! Your eyes can see, the gentiles are already standing ready around the ghetto and their weapons are in their hands. They are ready to plunder our property, the hard work of generations. Every Jew

[Pages 263/264]

who has in his possession an ax, a gun – arm yourselves with everything that comes to hand. Whoever has kerosene, gasoline – take it out! We, the people of Tuchyn, will fight. The moment you see a fire break out from one of the houses – that will be the signal for you. Go out and set your houses on fire.

The Gestapo man appeared in the ghetto. He said that all the young men needed to present themselves, a labor brigade was being organized.

Getzel Shvartzman replied: ‘We cannot at this time organize people for work.’ I do not know how the negotiation ended. People did not go out to work.”[20]

“The Jews had already been concentrated in the city beforehand. Now only the fence was built. The ghetto was established. When the Jews were gathered up and concentrated in the center of the city, it was already clear to us that a fence would also be built and that we would live in the ghetto.

Shvartzman passed along a message to prepare as much kerosene and gasoline as we could get our hands on. It was clear that with the building of the fence the end was coming nearer for the ghetto in Tuchyn. The brigade in which I worked, the forest brigade, obtained weapons in exchange for money. We had three rifles and several hand grenades. We hid the weapons. Shvartzman said only to prepare gasoline. The purpose was clear to all of us. The grain storerooms were currently inside the area of the ghetto. Inside the storerooms were huge quantities of grain[21].

At 3:30, shots were heard. Germans and the men of the [Ukrainian] police concentrated next to the fence. Immediately we, the few who had weapons, began to fire towards the Germans. Every person took care to burn their house. My mother was burned then, inside the ghetto. We broke through the fence and everyone who had the strength to run ran towards the Pustomyty forests. I think that among those who ran, at least 1,000 people were killed by German gunshots. They shot without pause.

Elderly Jews, those with beards and wigs[22], prayed and while praying jumped into the fire. Among them was Rabbi Abramel Vitkover. Shmuel Marakish, a Jew aged around 42, took his 10–year–old son and together with him jumped into a nearby well. They both drowned. That day terrible things happened. The town burned. From all directions they shot. Families lost each other. There were cases in which a mother ran away and the father and the children were left in the burning ghetto.

An acquaintance of mine, Shepsel Chrovshov, fled with two of his children. A bullet hit one of his children and with the little one in his arms he arrived in the forest.

We ran. All the houses went up in flames. The synagogues, which were full of grain, were burned down to the last seed.”[23]

“In the ghetto people began to end their own lives. Yehoshua Zeitchik, owner of an iron store, drowned himself in a water well. Mottel, the son of the tailor, cut open his veins. Jews prepared according to the instructions of the Judenrat. Our family lived in the house of Chaya Bern. In the afternoon they put me and Chayka's[24] son into the bunker. Suddenly I heard my mother's voice: Yaakov! Yaakov! I came out of my hiding place. I saw that the house of Sara Horbate (hunchback)[25] was burning. Immediately, shots were heard.

Another house went up in flames. Mottel, Chayka's husband, took two cans of kerosene, poured them over all the bundles and the furniture, wrapped himself in a tallis[26] and cried out: ‘Shema Yisrael!’[27] To us he shouted: ‘Run away, all of you, I want to burn inside the house.’ The house burned and Mottel, wrapped in his tallis, remained standing inside the flames. My father grabbed [me] by the hand and Mother held my little brother in her arms. I remember that in my father's hands were an ax and half a loaf of bread. Mother said to my father: ‘You run away with Yaakov. I will stay here. I do not have the strength to run with the little one. If I can, I will try. Meanwhile, don't wait for me. Run!’

We ran, my father and I. We fled. The fence had already been breached. Jews ran in all directions. The whole ghetto was burning. There was light all around. The shots from the hill did not stop even for a moment. Most of the people ran to the slope, in the direction of the cemetery, because from there it was easier to get out to the fields. Tuvia Tchubok ran to the purification house[28]. I saw how a bullet hit him and he fell. Dozens of people fell. Father and I managed to get out and to reach the Sobivka forest. I do not know how many people managed to flee. It was said that around 3,000 people fled.”[29]

In the early hours of the morning the local population began to bring to the Gestapo Jews who had been discovered hiding in parks, in gardens, and in other places.

The rural population did the same thing. The Jews who were on the roads they robbed. Sometimes they murdered them or turned them over to the Gestapo. On the night of the fire, several hundred Jews lost their lives in the ghetto. The rest fled in every direction. From Thursday (Yom Kippur was on Monday) until Friday, 1,000 to 1,500 Jews were caught.[30]

“Jews who wandered in the forests, in hunger and in panic, did not know where to hide and what to do with themselves. Parents with small children mainly returned to Tuchyn. Before the next day around 300 Jews were caught. They were allocated three houses. On Friday in the morning the new ghetto was surrounded. The Ukrainians and the Germans led the Jews to the cemetery and there they shot them.

A [female] Jewish pharmacist had been accepted once again for work. When the Jews were being led to the cemetery she saw that they were also leading her children. She leaped out of the pharmacy. They ejected her. She struggled with the police and together with the children went to die.

After that Friday, even though it was known that the Germans were deceiving [the Jews] and encouraging the return to the ghetto, the Jews continued to return to the town. They returned to death in full awareness, together with their children and their elderly parents, because they did not have anywhere to hide or a place to go. The peasants did not let them into their houses, did not give them a slice of bread, not even a sip of water.

On the roads were wandering many lone children, crying bitterly. These children had either lost their parents, or had been left on purpose. Babies were crawling on all fours on the roads and in the forest. With me was my three–year–old son. It was difficult for me to run with the baby in my arms, and his legs did not yet have the strength to run together with me.

[Pages 265/266]

I asked to leave him behind. But he burst into tears and begged me not to leave him. He said: ‘Mother, throw away your scarf[31] and it will be easier for you to carry me.’ I threw away my scarf in the forest. I met my cousin and we joined a group of 20 people, and we decided to move further into the forest, until we would find the partisans.

We walked in the forest, [and] on the way more and more Jews joined us, until we were 50 to 60 people. Young men, healthy and without families, began to persuade us that there was no chance of making it with such a big group, because doing so was filled with danger and because in this way we would not get to our intended region. They demanded that we split into smaller groups. The rumor was that the partisans were to be found in the Brezlevi[32] forest 20 to 30 kilometers from where we were at that time.

So it was decided that a group of men and women who did not have families would go out through the fields. A second group would go via a route that was shorter, but more dangerous. And the elderly, the women and the children would go through the forest. We traveled a distance of about 30 kilometers and we did not find any sign of the presence of partisans. The hunger, the thirst, and also the lice and the filth bothered us greatly, until we reached the point of utter exhaustion. I, together with two other women with babies, decided to leave the forest and to buy or beg for the charity of a little bread and water. My boy was three years old. Rachel Elbert had a boy of two–and–a–half, Aharon was his name. The third woman was carrying a baby just a few months old.

Behind the forest we found some huts. Next to one of them stood a woman. I approached her and asked for a slice of bread. She replied that she did not live in that hut and that if I would wait in the forest, she would bring me bread in about half an hour. After some time I peeked out from the forest. Next to that hut, apart from the woman, stood two men. In the hand of one of them I could see an ax. He noticed me and whistled to his friend. I understood and I began to run as hard as I could into the thick woods, and together with me ran the other women. Together with our children we huddled into the ground. Out of fear the children were silent and fell asleep. In the forest it was already getting dark. The peasant with the ax came close to us a few times. He understood that we were hiding there, but he did not notice us. God struck his eyes with blindness. The peasant cut some marks in the trees of the wood with his ax, and returned home. We began speaking to each other in whispers. What would happen when the children woke up and started crying? We all came to an agreement that we did not want to die because of the children. Each of us hoped still to find her [other] children who were lost and her husband.

We all began to run with our babies in our arms. With superhuman strength we passed all the obstacles that were in our way, and they were enough, the brambles and the branches of the wood that grew wild and that tore our bodies and our clothes. We reached the ‘old forest.’ Rachel, who was holding her son Aharon, in whose mouth a rag had been placed[33], tripped over a tree stump and fell. The boy apparently lost consciousness. Rachel, out of the reasonable belief that the baby was dead, left him there and continued her race. We ran a good part of the way and then continued walking.

Rachel wept bitterly over having left her dead baby behind. We reached a distance of about 20 kilometers from that forest. About six days later, Rachel met a Jewish woman from Tuchyn, and she told her that around three kilometers from that spot in the forest, she had seen Aharon, dazed and alone. It turned out that the next day [after he was left behind], the forest guard found the boy and took him home. Two days later, Jews came to him, asking for bread. The forest guard told them he had found a Jewish boy and demanded that they take him with them. [The guard said:] He is of your faith – take him. If not, I will take him to the city. Berel Zalman [Zaltzman] took the boy. He carried him for a few days and brought him to the same place, but when he saw that [looking after] the child was causing him considerable trouble, he hid him inside a pile of straw. But the child emerged from the pile of straw and wandered in the forest. Rachel left for the place described by the woman. There she found her Aharon, who came out towards her from behind one of the bushes. He was holding a small stick in one hand, and in the other some acorns. The boy was swollen from hunger. Around two weeks later, Rachel was forced to go with her son Aharon and with three other children she had found in the forest and to return to Tuchyn, so as to ease their hunger and their thirst before they were led to the gallows.

I walked with my boy for another five to six kilometers. There I found a group of Jews who told me that not far from there they had seen my husband, and indeed, I then found my husband and my older children …”[34]

“We escaped. The Pustomyty forest. A large crowd had gathered there. I estimate that there were around 2,000 Jews there. There were women, children, and men. There were women who had come without their children. Fathers who were bereaved or who had lost their wives and their children. Gathered in the forest were remnants of families, broken people. Roaming around were orphaned and abandoned children who had managed to flee without knowing to where.

They wandered among us.

Two weeks we were in the forest. It was autumn. Hiding in the forest. It was cold. One day I heard the crying of a small child. I went out. It was before sunrise – two days after the burning of the ghetto. On the wet ground was lying a woman (she was the daughter of David Wolf, who had a large house in the town) and on both sides of her were two young children. The mother was shrunken with cold, trembling and exhausted. She still had a slice of bread. I divided it between the two [children].

The next morning I did not hear any voice or murmur from around the corner where the woman had lain. I approached: The three of them were lying there, killed. The forest was close to the road. A Ukrainian by the name of Yukhim, who had been a policeman in the time of the Russians, passed by on his wagon, went into the forest, met the woman and her children, and killed them on the spot.

The autumn was in full force. We were in the forest. Two days we lay [there], lacking everything. There was no food and my brother Yossel and I went out to the village of Pustomyty, which was behind the forest. We went into the house of a certain Ukrainian, a Baptist, his first name was Sergei, [and] we asked him for food. He took out two loaves of bread and gave them to us.

[Pages 267/268]

Sergei told us: ‘I have just come from Tuchyn. The Germans have collected a lot of wagons harnessed to horses. People are saying that they are planning to come to the Pustomyty forests and to collect all the Jews from here.’

We returned to the forest and passed on the news. We had just finished speaking and we could already hear the noise of wagon wheels in the distance. A short time passed and the Ukrainians and the Gestapo people laid siege to the forest. Shots were heard. Bullets started flying in the forest. Women and children did not know where to run, and ran in front of the machine guns. The Ukrainians and the Gestapo people collected more than a thousand souls.

I, my brother Yosef, and a young [female] cousin of ours started to run.

A barrage of shots rained down on us. On the way we saw a large pit. We jumped inside, lay down, and the terrible screams of the Jews filled our ears.

We lay in that pit until 10 o'clock at night. It was a night with a moon. We returned to the forest, to the place where we had hidden beforehand.

We approached the pits. The pits were open. The bodies of the Jews were swimming in rivers of blood.

The residents of the village divided up the clothes of the Jews between them.

We ran to the house of an acquaintance of ours in the village. In the attic of his house, we found our brothers and also their wives. We collected the family members and also others who remained and returned to the Pustomyty forest. This time we distanced ourselves from the village, moved into the thick of the forest, and began to dig bunkers.

My brothers Yosef, Gershon, Nachum, Aizik [Isaac] and I – the five Shulman sons, and members of the Shef family, Shayke, Rikel, and Uri, and Fishel Rozgovitz – we were the fellows who took the wheel into our hands.

We began building bunkers. We finished digging. We had eight bunkers. In every bunker lived around 20 people – the few who remained after the siege on the forest.

The entrance to the bunker we concealed with tree stumps. During the nights we would go out to the village and collect foods from the villagers. We did not reveal our hiding place. We divided the food among all the bunkers.

The first snow fell. We were forced to go out to the village to get food. Our tracks were visible in the snow. The shepherds in the village noticed the tracks. One day the shepherds brought dogs to the village. They identified the bunkers, went to Tuchyn, and informed the Gestapo: ‘Jews are hiding in the forest.’

The Germans were scared to enter the forest. They sent Italian soldiers to the forest. They blew up the bunkers. The bunker where I was living was some distance from the other eight bunkers, about two kilometers away. Fishel Rozgovitz together with Eka[35] were the only two survivors out of all the eight bunkers. Both of them came running to our bunker and told us what happened.

Now there remained 14 people out of the 2,000 who ran to the forests on the day the ghetto burned. It was impossible to remain in the bunker in those forests any longer.”[36]

Now begins a long road, filled with many torments, of wandering and hiding in villages, in which a death trap awaited [us] at every path, house and barn. The winter of 1943 arrives. The “Bandrovists[37],” who had previously fought by the side of the Germans, began to fight against them. In order to overcome the Bandrovists, the Germans began burning entire villages if they suspected there were Bandrovist supporters in them. And the persecution of the remnants of the Jews did not stop.[38]

The testimony of Yaakov Tchubok continues:

”We met in the forest with a group of 20 people. A gentile we had met on the way warned us not to run in the direction of the village Zhalianka because there were gentiles there armed with pitchforks and knives who were robbing the Jews. I must emphasize that all the roads were blocked. At every place Ukrainians were waiting for us. They would strip the Jews naked. There were Ukrainians who with their own hands would murder the Jews. Others would take them back to the ghetto and hand them over to the Germans.

In Petrovitsa we met a Jew from Tuchyn. He told us that the elderly, women and children too had fled in the direction of the Pustomyty forests. We wanted to meet up with mother. We walked to the Pustomyty forests. We were told that they [the Jews there] had seen Mother and they also showed us the direction in which she had gone. We went. Luckily for us, we also found Mother. Our brother was in her arms. She was dressed in a torn dress.

German and Ukrainian police would every so often lay siege to the forests and kill the Jews.

Together with our mother and little brother, we walked to the village Petrovitsa. Or more accurately, to the forest next to the village. On the way we met a group of gentiles from the Kotovsky family. There were four young men. One of them had a gun. The rest had knives. They took away Father's boots. They took away his coat. Father remained barefoot and without a coat. It was already autumn and the cold was growing steadily. We managed to get to the Petrovitsa forest. On that forest too they had placed a siege. We managed, the whole family, to evade it and to get to Kudrianka[39]. There we met a lot of Jews. There were about a hundred Jews there. Among them were elderly people, women and children.

We noticed that Jews who knew the places began to avoid them. It was dangerous to crowd together because the matter would immediately become known to the Germans and they would lay siege [to the area].

Among the Jews was one family who before the war lived in Kudrianka. They knew all the roads and the paths in the area. And they also knew the forest well. Winter was approaching. The cold was growing. My mother said to me: ‘Yaakov, come and let's return to Tuchyn, there we left a lot of clothing with Andrei Maktera. Come with me and we'll take some [clothing] for us. Otherwise we'll freeze from the cold.’

[Pages 269/270]

A youth from the village of Kudrianka, aged around 17, agreed to come with us, to show us the way. He was also interested in receiving a few things. I was scared and did not want to go. I promised mother that at night I would steal into the village and would take some clothes that were hanging on their lines. The young man convinced my mother that nothing would happen and that it was possible to go. I took pity on my mother and went with her. We set off on the way at night. We arrived close to Tuchyn. On the walls of the houses were stuck announcements in German: Every Jew from the Tuchyn ghetto who returns to his home – nothing will happen to him.

We went into Andrei Maktera's house. He saw us. He let his dog loose. He held a pitchfork in his hand and shouted at us: ‘You dare to cross the doorstep of my house? Get out of here, and if you don't, I will finish all of you.’

This was a gentile who was a good acquaintance of ours. We had given him all our property: leather coats, leathers for shoe soles, shoes, and suits of clothing. We brought to his house sheets, pillows and feather blankets. In short, a large and valuable amount of property. This was the reception given to us by this ‘friend.’ Mother was caught, the Germans shot at her from behind.

I ran injured. I would run and flatten myself on the ground. I was nine years old then. I was scared. I was by myself in the forest at night. I knew that the Germans had taken my mother. I did not feel the pains [of the injuries]. At home, they always used to tell me stories of forests and wolves. From those stories I remembered that wolves did not climb trees and that there was no place as safe as a tree. I climbed up a tree. I curled up and sat there. Only when I sat up in the tree did I feel something dripping down my leg. I groped with my hand and I felt that I had an injury.

I held the wound with my hand and sat. The blood dripped. When the morning light came, I climbed down from the tree. I made it to the forest to Father. Father asked me: Where is Mother?

I panicked terribly. Suddenly I understood that something terrible had happened to my mother. I started telling Father, stammering throughout. Father cried a lot. My little brother, who was then three, also understood that something bad had happened and he too burst into tears. From that day on, I was the main supplier. I would go out to the villagers, beg for charity, and bring food to the forest, for Father and for my little brother.”[40]

Only a few, mostly lone individuals, continued to wander in the fields and in the forests, and even from those, only some prevailed to liberation.

Translator's Footnotes

By Miriam Shvartzman–Kouts

Translated from Hebrew by Miriam Bulwar David–Hay

Donated by Anne E. Parsons – Department of History, UNC Greensboro

In September 1939 the Russians entered our town. Communist Party activists arrived from the Soviet Union and they managed matters in the town. The Russians left the Jewish school alone and even opened additional classes. At that time it had 10 classes. The Polish school was closed and instead the Russians opened a Ukrainian school of 10 classes.

In 1940 the Soviets conscripted the young people to the Red Army. Many Jews were called up. The recruitment was in April 1940. I remember the matter because my brother Leibl was also conscripted. Many Ukrainians were also recruited to the army. According to news that arrived after the war, my brother fell [was killed] during the war. The Soviets removed the Germans out to Germany and brought to our area Ukrainians from the area of the Bug [River]. A number of Jews from Tuchyn were sent to Siberia.

In 1941, with the outbreak of the war [between the Germans and the Soviets], the Germans advanced with giant strides. The Germans entered Tuchyn at the beginning of July. About two weeks after the outbreak of the war, during their retreat, the Soviets transferred to the Soviet Union all the people who had been working in government offices. Many young Jews escaped in the wake of the Red Army.

On the Horyn River was a bridge that connected Tuchyn with the Ukrainian village Shubkiv. During their retreat, the Russians blew up this bridge. The Ukrainian population received the Germans with enthusiasm. They helped the German army enter the city. They placed boats at their disposal and helped their boats cross the Horyn River. Fear fell upon the Jews of Tuchyn. Every family looked for a place to hide. Many families left their homes. It seemed to the Jews that it was worth dispersing to houses further away, that stood at the edge of the city.

Our family moved to the house of a cousin of my mother's, Moshe Giterman, who was the owner of a farm and lived outside the city.

The Germans entered the city. Many Jews did not manage to get to the homes of their acquaintances in the “Sand[1].” The Germans ordered all the Jews to assemble.

|

|

| Getzel Shvartzman the “soltis” [“village elder”] |

[Pages 271/272]

They thoroughly examined the bundles in the hands of the Jews, whom they had stopped in the street. They were searching for weapons. The Ukrainians led the Germans to the houses of the Jews and pointed to the homes in which Jews lived. In Moshe Giterman's house that day were a number of families – around 50 people. The Germans went into the house, ordered all of us to go outside, and ordered us to raise our arms. They carried out a search inside the house, and when they did not find anything they ordered us to disperse and for each person to return to his own home.

The German soldiers set themselves up in Tuchyn. In the first days they took over all the offices: city hall, the post office, the schools. In those initial days they left people in their homes. Our house was in the “Sand.” Our neighbors by a vast majority were Poles; Ukrainians also lived in our area. In those first days, brigades of German soldiers would come to the city, rest, and continue on to the front. The soldiers would pass through the city. There was constant movement by day and by night. Brigades left and new brigades came. German soldiers also took over the city park. This garden had belonged to the owner of the Otfinowski[2] estate, and the Russians turned it into the city park.

The Ukrainians felt themselves to be the masters of the city. Not just from Tuchyn, but also from the villages in the area, Ukrainians began arriving with sacks in their hands. They would break in to the houses of the Jews and fill the sacks with clothing, bedding, and anything that had value. About a week after the entry of the Germans, the first pogrom in Tuchyn was carried out by Ukrainians. The organizers were sons of the city who during the time of the Russians had cooperated with them and declared their loyalty to the Soviets. Already in the first days [of the German occupation], they changed their colors. At the head of the rioters stood: Rytchak the lame[3], Prokofchik, Ostomenka, Prokop Polishtchuk, and others. At night Ukrainians broke into the houses of the Jews. The criminals acted mainly in the center of the city. They murdered and plundered. Jewish blood was spilled. There was not a house in the center in which killed and injured people were not found. Killed and injured were in the houses of: Halperin, Katzman, Gitelman, Chisado, Spozhnik, Zabodnik, Feldman and others. To the “Sand” the rioters did not come that night. In Tuchyn there was a Ukrainian paramedic, Humeniuk, and a Polish doctor, Bortnovsky. Humeniuk was a Jew hater. Dr. Bortnovsky offered his help to the Jews during all the difficult times. There was a merciful Russian nurse, Genia, who also helped.

After the pogrom, the German and the Ukrainian police in Tuchyn gathered up around 30 Jews and led them to Shubkiv. Before that, they tortured all of them in the gendarmerie and on the way to Shubkiv shot all of them. It was then that they murdered Pink [sic] Tsilingold, Yankel Gelfenboim, Baba Shpitz – all of them were residents of Tuchyn. The rest were refugees from different towns in the area. They were promised that they would be returned from Shubkiv to their places of residence, but on the way all of them were murdered. I saw how they were leading the people. Together with other Jews I was sweeping the streets of the city under an order by the Ukrainians. The Ukrainians took over the government of the city and immediately organized their own police force. As head of the police, Prokop Polishtchuk was appointed. Ostomenka was his deputy. Also active in the police force were Rytchak the lame, Alexander Meshovkov, and others. They were all known as robbers and murderers, haters of Jews. Shetcherbeniuk from the village Sinena was appointed head of the town. He too was a known anti–Semite. Also working in city hall was Grishka from Tuchyn. In the city offices worked the Ukrainian nationalists, all of them known anti–Semites.

The Gestapo people from Rivne came to us. They came with the premeditated intention to kill Jews. They ordered the Ukrainians to collect the Jewish Communists in the town. The police went from house to house and searched for men. All together they collected around 28 men, young and mature, and in the yard of the police [headquarters] they shot them all. The Ukrainians were active and tried to catch as many Jews as possible. The Germans were very punctual people and the end of this “aktzia[4]” was set for a specific time. The Ukrainians were extremely disappointed when people who arrived late were sent home. The Germans told the Ukrainians: The time for the action has ended, no more will be shot today. That day they killed Moshe Gemer and his son, Baruch Rozenberg and his two sons, Hershel German and his two sons, Yitzchak Driker, and others.

The Ukrainians began catching Jews for work. To our house one day came Polishtchuk and Ostomenka from the police. They ordered my father to establish a “Judenrat[5]” in Tuchyn and to serve as its head. My father was always the “soltis[6]” in Tuchyn (crowned) and everyone knew him. Maybe because of that they turned to him. My mother opposed this completely, that my father should take on this role. I know that my father also did not want this, but he had no choice. The Germans did not ask him. They forced this job on him. Despite this, many Jews turned to my father and asked him to take the position. He was the man in Tuchyn who in orderly times would sort out the issues of the Jews in the government offices.

The Judenrat was established. The Jewish population placed their trust in my father. The Judenrat in Tuchyn may indeed have carried the name, but in practice it functioned as an eye of the Jewish community. Appointed as my father's deputy was Meir Himelfarb, who was a respected Jew in the town. He too was a merchant. As members of the Judenrat were chosen: Yosef Rotenberg, Elik Chomut, Berel Zaltzman, Chaim Glatshtein, Krishtol, Aharon Marakish. Other Jews would help the Judenrat in times of need. The secretary of the Judenrat was Yosef Rotenberg. In the secretariat worked three young women: Chaya Apel, Basia Valdman, and me (Manya Shvartzman).

In Tuchyn was the commandant of the district – Kreislandwirt[7]. He was a German who had been sent to us from Germany, and his name was Grabner, and there also arrived Germans who worked in the Gestapo and in the government offices. In the Gestapo in Tuchyn there also worked Ukrainians. Everyone would turn to the Judenrat: Grabner, the Gestapo people, the Ukrainians. Each came with his own demands. The Germans would demand Jews for labor and would sent them to cut down trees in the forests in the area, to work in the fields in Shubkiv (in Shubkiv the Russians in their time had established “Shubkhoz[8]”

[Pages 273/274]

and this continued to exist as an agricultural farm also in the days of the Germans). They would demand Jewish women as cleaning workers in the offices and private homes (houses of Germans and Ukrainians). The Judenrat was forced to organize the list of people for labor and took care that all the Jews would return from the work. The Judenrat would pay large bribes to everyone who came in contact with the Jews: to Grabner, to the police, to the Ukrainians, and also to those supervising the work. They paid and they bribed so as to guard the safety of the Jews.

In Rivne there was a central Arbeitsamt[9] for all the district. The Gebietskommissar[10] was Dr. Bayer. There [in Rivne] was also the office of the Reichskommissar[11] for Ukraine – Koch[12]. The Judenrat would also send large gifts to Rivne to the people in the Arbeitsamt – the labor office. They would bring them clothing, shoes, furs and pork. All these things the Judenrat would collect from the Jews, with their aim being to have an effect on the center, so that the Jews would not have to leave the city, Tuchyn.

Immediately after the Judenrat was established, the head, Getzel Shvartzman (my father) was invited to the gendarmerie. There awaiting him were Germans from Rivne and Ukrainian gendarmes and they demanded that he pay a “kontributzia[13].” They demanded that he bring jewelry, gold, silver, and foreign currency. On top of all that, they imposed a head tax [on the Jewish population] in German marks. The Germans ordered my father to bring the “kontributzia” by evening the next day. I remember that in the Judenrat then we worked all night in order to organize the lists. Many Jews had come to Tuchyn as refugees from cities and towns in the area in which there had already been “aktzias”: from Kostopil, Mezhyrich, Rivne, and other places. There were in Tuchyn also refugees from Poland, who had already escaped the Germans in 1939. These Jews were in Tuchyn illegally and they needed to be guarded from the eyes of strangers. There was obvious danger to them from the Ukrainian detectives, who were always ready to inform on the refugee Jews to the Germans. A Jewish refugee who was caught would be returned to his city and it was obvious that he was at risk of death. Of course my father ordered us not to put the names of refugees into the lists, and also not the names of Jews who were missing a work permit (Arbeitskarte).

The same day my father turned to the Jews of Tuchyn and spoke to them from the podium in the synagogue. He told of the trouble (the “kontributzia”) and asked for their response. Many Jews brought their jewelry themselves. A large crowd gathered next to the Judenrat and the people from the Judenrat were frightened that the gathering and the movement in the streets would awaken the attention of the Ukrainians, who were always complaining that too many Jews were roaming through Tuchyn. So they [the Judenrat] urged the Jews to return home and the Judenrat people would pass through the houses and collect the valuables.

The next day my father and Yosef Rotenberg went to the gendarmerie to hand over the kontributzia. My father explained to the Germans that Tuchyn was a poor town and it was impossible to collect more money. This time the Germans were satisfied with what had been brought to them, and they returned to Rivne.

Months passed and Tuchyn did not deport Jews, and the Judenrat continued to bring bribes. One day a new police commandant was appointed in the town, Stadnyk, and his deputy was Stiopa Trofimtchuk. Rytchak moved to the district [office]. These Ukrainians acted according to German instructions. In the gendarmerie a new department was opened – the punishment department. At the head of this department was a Ukrainian from Galicia, Vitovitch, who was known for his cruelty in the whole area. New police also came to Tuchyn. The situation worsened and it was necessary to build ties anew with the police. It was necessary again to bring gifts and again to bribe. The bribes and the gifts had to be presented without anyone seeing. It was forbidden that one clerk would know about the other.

There was one policeman, Petro from Glinsk, who would cooperate with the Judenrat and passed on all the important news. The punishment department would abduct innocent people and in order to free the prisoners much money had to be paid. The head of the department would arrest Jews, put them in the jail, and wait until they came from the Judenrat to ransom him.

With the entry of the Germans, food ration cards were distributed to all the residents. The food rations would be distributed in the same store that in the days of the Russians had been the cooperative. In the lines [waiting to receive the rations] the gentiles would beat the Jews, push them, curse them, and abuse them. When the time arrived to receive foodstuffs, every Jew had to pass through torments until they arrived at the cooperative store, and even there they had to absorb humiliations and insults until the clerk handed over the sparse portion. In practice the Jews received only bread and I do not remember what the size of the ration was. I only remember that every time they would make the portion of bread smaller. In order to prevent all this, the Judenrat decided to receive all the rations for the Jews of Tuchyn in one concentrated lot. In one of the houses the Judenrat set up a center where they would distribute the foodstuffs. Once in a while they would also get a bit of sugar and oil. A young woman, Miriam Vinshelboim, would distribute the rations.

One day Grabner called in Getzel Shvartzman and told him: “In Tuchyn there is no ghetto and in order to know who is a Jew, from this day and on, all the Jews must wear two yellow patches, one on the chest and the second on the back.” (Until that day the Jews of Tuchyn wore on the left arm a white stripe on which had been stitched a blue Star of David.) My father tried to reduce the evil of this decree. He spoke to Grabner's heart, a gift was also presented to him, and the matter of the patches was forgotten for a certain time, until my father was summoned again to Grabner and this time he was informed that it was impossible to delay the order any longer and the Jews of Tuchyn had to wear the two patches. You of course do not need to wear the patches, Grabner consoled my father. But he replied: “I am a Jew and I will wear the patches like all the Jews.”

The Germans distributed work cards. A Jew who did not have a work card could expect to be deported and sometimes worse than that. Every Jew

[Pages 275/276]

from the age of 14 had to work. With the entry of the Germans, my two brothers, David and Liova, worked at repairing machines and bicycles for the Ukrainians and the Germans, of course in fear and without payment. The Judenrat began looking for workplaces for the Jews of Tuchyn. Workshops (werkstaelle) opened: haircutting, tailoring, shoemaking, metalwork, carpentry, welding, and so on. The organizers of the workshops were: my brother David Shvartzman, Yitzchak Portnoy, Sioma Spozhnik; the bookkeeper was Chaikel Fuks. In the accounts management worked Sara Sheinfeld, Shifra Sheinfeld, and others. The orders would be handed over by the Germans to the management of the workshops. The Germans and the Ukrainians would also place private orders: shoes, boots and clothes for themselves, their wives, their children, their lovers, and ordinary acquaintances and friends. All the orders had to be prepared by a set date. In the workshops worked professionals and also ordinary Jews who did not have places to work.

The winter of 1941 arrived. The “passportization” began. Every person from the age of 14 had to obtain a passport[14]. The Jews also had to obtain passports. A Jew without a passport was sentenced to deportation. The Ukrainians who worked in the town administration did not know German. They turned to the Judenrat to give them three people who spoke German and Ukrainian to assist in producing the passports. The Judenrat sent to this work Yosef Rotenberg, Sara Rozenberg, and me. In the passport production worked the Ukrainians Vasil Trofimtchuk, Rytchak the lame, and Nadia, who was a Volksdeutsche[15]. Her brother worked in the Gestapo and was known as a murderer. We the Jews were seated between the Ukrainians, so that they could keep an eye on us. In the initial period, each Jew would come by himself to collect his passport, in which was written his occupation. In every Jewish passport we would try to write as an occupation a trade of some kind, as the free professions[16] and commerce would bring about catastrophe for their owners. In the beginning the Ukrainians did not understand and we succeeded in this. But they quickly learned the names of the professions in German and began to supervise and check the passports. A second problem that we did not know how to solve was the problem of the Jewish refugees. They could not come to the town hall to collect passports, because the Ukrainians knew everyone in the town. Rytchak and Trofimtchuk would torment the Jews at the time of handing over the passports. Sometimes Germans would appear in the town hall too, and would ask how it was possible that in Tuchyn there were still so many Jews walking around. The Judenrat found advice for this too. After a suitable gift into the hand of the mayor, it was “explained” to him that, for the sake of the efficiency of the work, it was worthwhile that the passports would be prepared in the town hall and that the head of the Judenrat or his deputy would come twice a week and collect the ready passports and distribute them to the Jews. The mayor agreed to the offer. Now a new era started in our work. The Judenrat would prepare lists for us, and among the names of the Jews of Tuchyn they would insert the names of the refugees. In addition to writing the passports, it was part of my job to check them and present them to Trofimtchuk to sign and to stamp. The arrival of Germans at the town hall would cause panic among the Ukrainians. Trofimtchuk and his friends would go outside to a meeting with them [the Germans] in the neighboring yard. In his panic, Trofimtchuk would forget to close the stamp. I would make use of hours like these and would stamp empty passports and smuggle them to the Judenrat, which later would fill them out and give them to Jews who were not kosher [who did not have the required papers].

Apart from the refugees, there were also non–kosher Jews [without legal documents] who had been active during the time of Soviet rule and had not managed to escape with the Red Army, or the parents and relatives of those young Jews who had fled. I had to wrap up the bundles of passports. I remember the picture clearly: My father would come to collect the passports, his face pale and a cigar in his mouth. He would stand in front of me; he would always try to control his demeanor and also to calm me. I would wrap the bundle and would insert the non–kosher passports inside, everything with the speed of lightning. Father would take the money out of his pocket and pay (for every passport it was necessary to pay a certain sum). Sometimes I would stay to work in the afternoons, on days when there was a lot of work. That was an excellent opportunity to act according to the need. Twice a week they would come from the Judenrat to collect the passports, once my father would come, once Himelfarb. In some cases I got out passports with Polish nationalities to Jewish women who were refugees from Poland. As far as I know, thanks to a passport like this, Hanka Zilbershtein of Warsaw stayed alive.

The passportization chapter ended. Yosef Rotenberg and Sara Rozenberg returned to the city and I continued to work in the town hall according to the demand of Rytchak, who was deputy mayor and managed the economy and the work in the town hall. My father explained to me that I had to be alert and keep an eye on all the orders received in the city in relation to the Jews. In the department worked with me: Nina Stadnyk – Ukrainian; Sasha Osiptchuk – Ukrainian; Vanda Kopistinska – Polish. Rytchak had his own office and we would sit in the next room. Sometimes we would need to go into his room, to give him a document to sign, or to ask him for typewriters. One day I went into Rytchak's room. By chance, at the same time the mayor called him into his room. On Rytchak's desk I saw an order that had been marked with a red pencil, a sign of urgency. In this document was written that on a certain date 150 Jews needed to be taken from Tuchyn for work in Tynne[17] (I do not remember the date). I returned home and told my father. It was two days before the order was due to be carried out. The Judenrat immediately called the Jews to an urgent meeting in the synagogue. My father related what was about to happen and said to them: “Jews, do whatever you can, hide, flee!”

In the morning at sunrise the black vehicles of the Germans entered and crossed the city. They did not find a living soul across Tuchyn. The Germans ordered the Judenrat to bring 150 Jews immediately. My father replied that he did not know where the Jews were and he could not find them.

[Pages 277/278]

On the machines of the Germans was written T.O.D. in large letters, and at that time we did not yet know what their meaning was. We did not yet know about the German department T.O.D., whose role was to build bridges, pave roads, and so on. Many Jews thought that the meaning of T.O.D. was death[18] and the panic in the city was great. The Germans returned my father in one of the vehicles; they led him across the whole city and announced on loudspeakers: “If within one hour 150 Jews are not assembled at the Judenrat, the head [of the Judenrat] will be executed.” The Germans went to houses and removed the women and the children, and the husbands and fathers came out of their hiding places to release their loved ones. Seventy people came. The Germans led them to Tynne and they worked there at paving roads. After a few days, my father together with Yitzchak Portnoy traveled to Tynne. They went to the Germans who were supervising the work and with a large ransom succeeded in releasing the 70 Jews and returning them to Tuchyn. Basia Valdman was sent to work in a Ukrainian Arbeitsamt. Her manager was Vitovitch. The Judenrat was interested in obtaining information on what was being done in the Arbeitsamt.