|

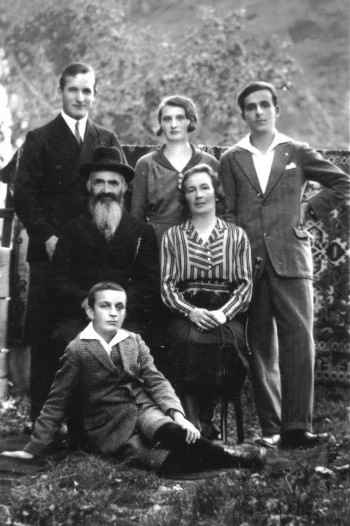

From the right: Standing: Ze'ev, Ester, Yeḥezkel;

Sitting: Tova, father of the family, and Meir Heller

|

|

[Page 360]

Translations by Moshe Devere

My husband was known as one of the founders of the Beitar branch in Suceava, so he left in January 1939 on an Aliya Bet [illegal immigration] (Aliya af al pi) from Constanta on the immigrant ship Rim. But on the way, the ship burned down and the passengers were deported to Rhodes for several months. When they finally arrived in Eretz [Israel], they were again captured by the English and sent to the camp. From 1941, my husband spent two years in a Beitar work-group in Kfar Saba, in what was then called the “Procuring work for Hebrews”.

In 1943, he moved to Haifa, and worked as a watchmaker, which he studied before Aliyah, with the late Ben-Zion Klueger. From 1944, my husband was independent, with a business in Haifa in watches and jewelry. We married in 1945, and we are parents to a son, Shimshon; and a daughter, Esther. And of course, we have grandchildren and a glorious family.

My husband suddenly passed away in February 1999 from an illness despite his being a healthy and athletic person. Blessed be his memory.

And these are the generations of Yisrael Heller's family

I was born to my father Yisrael Heller and my mother Reisel (née Rand) on 14 Kislev 5691 (Dec. 4, 1930) in Suceava. I remember my childhood in our house on 17 Dimitri Dan Street (Meltzer Barg).

My grandfather, R. Leibush Heller, son of R. Ḥaim, was one of the pillars of the Sadigura Ḥassidic Synagogue (Sadigurer Shiel). He organized a private charity fund whose money was distributed personally every month to needy families. My grandmother, Hannah (née Schaerf) was his helpmate, ran the house and also helped make a living by employing a team of knitting workers.

The family made a living from a trykotaż (knitwear) factory (mostly knitted winter clothes). My father had a partner named R. Shimshon Zwerling, a scholar, who came to Suceava from Poland. In partnership with my father, they founded the knitting factory in Admor R. Yankele Moskowici's courtyard. R. Shimshon was the technical director and Father was involved in materials purchasing and marketing. The livelihood was ample and we were among the affluent families in our city. At first, I studied in R. Kalchstein's ḥeder, but since I became ill a lot during my childhood, my father hired private teachers, including R. Gottlieb, who taught me religious and general studies at home.

[Page 361]

Our lives were tranquil until antisemitic decrees of the Romanian government began in 1938. Our financial situation began to deteriorate, after which the ghetto was set up, and we had to wear a yellow Star of David on our chests and back. On Thursday of the week, the second of the intermediate days of Sukkot, a proclamation was announced on the streets by a drummer on behalf of the authorities. He announced that within a few hours we must gather at the Burdujeni train station equipped with food for 24 hours and as much as clothes as we could carry.

We were put into very crowded cattle cars. The train left on its way in the evening. It turned out we were on the first transport to Transnistria. The next night, Saturday night, we arrived at the Ataky train station. We were taken off the train with shouting, beating and humiliation by the Romanian gendarmes and taken to the Great Synagogue of Ataky. Along the way, villagers attacked us with sticks, beat us and tried to rob our packs. I evaded them and keep my backpack.

On Friday evening, our family was separated from a Father who was taken away to convert his Romanian money into rubles, and we, grandparents, Mother and myself were led in a convoy to the Dniester River, which we crossed on rafts toward the city of Mogilev-Podolsk. Mother told me that some people drowned during the crossing. In Mogilev, we were put into an old barracks, which did not have any doors or windows. we were placed into one of the rooms on the second floor. On Sunday evening, Father returned to us. He had managed to bribe the gendarmes to keep us to remain in Mogilev until after Simḥat Torah. After the holiday, we were attached to a convoy that began to travel on foot from kolkhoz to kolkhoz. We slept in former pig-pens, until we reached the town of Lucinz on Shabbat Bereishit (27 Tishrei 5702) in the early evening. The local Jews greeted us with warm soup, which revived us. Luckily, we were housed, along with other families, in an attic in the home of a Ukrainian Jew where we could rest a little from the hardships of the road. The next day, my grandfather, R. Leibush, began putting on Tefillin and praying. As he placed Tefillin on his arm, an armed group of gendarmes, screaming loudly, entered and drove everyone out. My grandfather fell to the floor holding his head Tefillin and never got up again. A Jew who presented himself as a doctor pronounced him dead. Because of my grandfather's passing, my father bribed the commander to allow us to remain here for two more days so that we could bring my late grandfather to Jewish burial in Lucinz. My late grandfather's death on 28 Tishrei 5702 (Oct. 19, 1941), saved us from deportation to the German side of the Bug River.

Two days later, we joined a transport to the Ukrainian village of Zagora. We were housed in an abandoned ruined building, as were other families. A few days later, we rented a room with a peasant woman who had a disturbed son. Her husband was liquidated in one of Stalin's purges. There were hardly any Ukrainian men in this village.

[Page 362]

After about two months, when my mother was in advanced pregnancy, my father smuggled her into Mogilev to her brothers, the Rand family. Grandmother, Father and I remained in Zagora. A few weeks later, my grandmother Hana died of an illness on 29 Tevet 5702 (Jan. 18, 1942). Father risked his life and brought his mother, grandmother, to the Lucinz ghetto for Jewish burial. However, the ground was frozen and it was impossible to dig a grave. So, my grandmother was buried in a mass grave along with other Lucinz victims. After Father returned from Lucinz, we both sickened, a few days apart, with typhus. We lay on the floor with a very high fever, no food and no medical attention. Miraculously, we overcame the disease. My father reunited with the family in the Mogilev ghetto. We hired a peasant with a cart that drove us through the fields for a few nights until we arrived in Mogilev on the eve of Passover 5702 (1942). This is where we learned that Mother had given birth to a daughter who died.

Since we did not have a permit to stay in the ghetto, we each had to hide with a family member in a different hiding place. I could get into Orphanage ¹ 1, which was had been a hospital. Here I suffered from hunger and lice. Occasionally, my father or mother snuck in something for me to eat. Thus, it was all summer until the bitter and dreadful day, Friday, 28 Tishrei (1942), the anniversary of my late grandfather's death. When my father went to bring me food, he was caught on the way and forcibly transferred him to the Pechara death camp. On the same day, R. Shimshon Zwerling was also taken to Pechara from his sickbed. Mrs. Itzcovici, also from Suceava, managed to escape from the Pechara camp to the Morfa ghetto. Before her death, she told her husband that my father had tried to escape from the camp, was captured and killed. It was only a year later that we learned about my father's death from my uncle, my mother's brother, R. Leibush Rand, regarding Mr. Itzcovici's indirect testimony. Since then, I began reciting the Kaddish every year on 1 Kislev. My mother did not come to terms with the bitter news and continued to wait for her husband's return. Uncle Leibush took us under his wing and every Friday night invited us to his house. He would always say that, “During unbearable days, when a Jew wakes up from his sleep, he should know that today will be better for him than yesterday and that tomorrow will be better still.” This motto uplifted our spirits and helped overcome adversity. Uncle Shimon Rand, who worked at the foundry and received a daily ration of bread, also helped support us.

In March, a few days before Purim 5704 (March 1944), we were liberated from Nazi occupation. Two bridges were stretched over the Dniester River, which the deportees built for the German Army, my mother among them. We were saved by eleven partisans who took advantage of the confusion in the retreating German and Romanian Army, got onto the bridges and started throwing hand grenades at the retreating soldiers. The Germans thought the Russian Army had already arrived. So, they set off the booby-trapped bridges and blew them into the air along with the partisans. A monument was set up for them in Mogilev. It was later learned that the SS had already been in the ghetto at the time to exterminate all the Jews before withdrawing.

[Page 363]

We stayed in Mogilev after the liberation until the front moved further away even though we aspired to return to Suceava as soon as possible. It was not until July, after the border between Russia and Romania was closed on the Prut River, that we received permission from the authorities to travel to Czernowitz. We organized several families and hired two freight cars from the train-station manager in Mogilev to hook up with a military train going to Czernowitz. Instead, they connected the carriages to a train heading to the Iaşi front. For five days, we were very distressed. We suffered bombings by Messerschmitt's, and food and water shortages until the mistake was corrected. In July 1944, we arrived at Czernowitz train station. We slipped away from the train station and reached relatives living in the city who were not exiled. We rented a room on the Jews Street and I tried my talent in peddling. I bought contraband from the locomotive drivers returning from Romania and sold to the peasants in the area who came to market on Mondays. This is how we made a living until after Passover 5705 (April 1945), when we finally received permission to cross the border and return to Romania. For two days we lingered in Siret until we got a horse and wagon and returned to Suceava hoping to find the property we had left before the deportation. We had two houses here: one large one with eight rooms that we used to rent out and a smaller one that had two apartments. The big house was destroyed in the war and we were moved into the small one. We found two large knitting machines and two smaller ones that had not been stolen. We rented the machines to a cooperative that paid for using them. My mother was also recognized by the Romanian authorities as a war widow and received a small pension. From these incomes, we made a living until the end of 1947.

We asked for permits to emigrate to Eretz Israel. My mother immediately received the permit, but she did not take advantage of it because I was prevented from leaving Romania since I had reached recruitment age. After a few health committees, they discharged me from the army and I started working in a warehouse supplying the Aprozar stores. In my spare time, I studied with Rabbi Tarnover and Rabbi Naḥum Bacal and also with Rabbi Shaul Gottlieb. I also played chess in the town club.

So, life continued until December 1958, when we received a visa to enter the State of Israel. We took trains through Hungary, Austria and Italy, to the port of Naples. From there, we sailed on the Transylvania to Israel. We disembarked at Haifa Port on January 26, 1958. The Jewish Agency picked us up and gave us a 39 m² apartment for rent in Jerusalem, in the Ir Ganim neighborhood on 22a Avivit Street. I refused to attend Ulpan because I had to support my mother. I looked for a job and within two weeks I started working at Mr. Zvi Fuchs' wholesale store. In the summer of 1959, the Labor Bureau sent me to work in the Post Office, in the Payroll Division. Every six months I was fired and two weeks later I was put back to work at the Postal Bank, in the savings department. At the beginning of November 1960, the owners

[Page 364]

of Mero (a grocery wholesaler) offered me a job as the company's bookkeeper. I accepted the offer. The business that once employed five people developed to about 40 workers and I became chief accountant and company comptroller. I worked here until retiring in 1998.

In January 1961, I was drafted into the IDF and after an abbreviated boot camp; I was transferred to the reserves. The Akiva Rubinstein Club in Jerusalem was where I played chess. I reached the rank of candidate for Master Plus. In the summer of 1967, I took part in the Six-Day War and was privileged to be the first wounded person at the Training Farm outpost when the campaign to liberate Jerusalem was launched.

In May 1970, I was introduced to Ḥayya (née Schaechter) from Haifa, and I married her on February 16, 1971. We had two daughters: Yisraela, after my late father, and Batya Esther, after both our grandmothers. Ḥayya was a senior teacher and worked at the Evilina de Rothschild School and later taught at the Yehuda Halevi School. She was also active in education and was a member of the Teachers' Union Jerusalem Pedagogical Council. Alongside my accounting work, I was elected as a member of the “Zichron Kedoshim” Synagogue Committee, which was founded by Holocaust survivors in 5712 (1952), and was appointed (voluntarily) treasurer. After the committee's elders passed away, I was elected in 1980 as the director of the synagogue, a role I still fill to this day.

In early May 1995, Ḥayya was diagnosed with a malignant disease from which she did not recover. She passed away on 27 Menaḥem-Ab 5755 (Aug. 23, 1995) and was buried in Har Menuḥot in Jerusalem. My mother also passed away at a ripe old age on 23 Marḥeshvan 5759 (Oct. 13, 1999).

Our daughter Yisraela married Yedidya Dabash and we have four grandchildren from her (in the meantime!): Ḥayya Bat-el (after my wife), Roy, Hillel, and Vered.

Since Ḥayya's death, I have devoted myself to my work in the synagogue and expect our youngest daughter Batya to marry a decent guy and bring us good grandchildren.

(A note from the Editorial Board: Ze'ev Heller passed away in 2006 shortly after writing his story. Blessed be his memory.)

(Adapted by Yehuda Tennenhaus)

In 1941, I was in a forced labor detail in the Kachike Forest. When I was returned to Suceava, there was not a single Jewish soul there, because they were all deported to Transnistria. I made my own way to Ataky. There, I met a Romanian who served with me during our time in the Romanian Army in Bessarabia. He suggested that I be transferred to the other side of the Dniester [River] by myself and not part of a convoy. I discussed this with Dr. Teich. He agreed to give me funds for bribing the Romanian authorities

[Page 365]

not to transfer the Suceava Jews via the “Selection” camp. That way, some of the Suceava Jews could live in the cinema building and then move to Shargorod in a more convenient manner.

In November 1943, I married Hana (my wife) who came from Dorohoi. The wedding took place in Obcina. The ceremony was led by the late Rabbi Y.M. Marilus (Chief Rabbi of Bucharest after the war).

|

|

From the right: Standing: Ze'ev, Ester, Yeḥezkel; Sitting: Tova, father of the family, and Meir Heller |

In December 1943, the Dorohoi deportees were granted permission to return to Romania. So that we could stay together, I recruited two Jews who testified that I also came from Dorohoi. At Mogilev railway station, the people of Dorohoi were assembled to board a train that would take them to Romania. Unfortunately, among the Jews there were informants who told the Gendarme that three Jews among the candidates to return to Romania were not from Dorohoi. Gendarme Commander Colonel Bodoroga decided to execute the three by firing squad to serve as an example and a warning to the rest. Among those present from the Return to Romania Committee was Dr. Meir Teich as a representative of Shargorod; Moshe Katz, representative of Mogilev, and Fred Shraga, representative of the Jewish Federation of Bucharest. They bribed

[Page 366]

Bodoroga with a serious sum of money. So, he finally allowed us to board the train to Dorohoi. But also in Dorohoi there were informants and collaborators with the police, and so we were arrested and sent to Viznitza to face a military tribunal, and luckily, through bribes, we survived.

It is a story about two young people from Suceava who attended the Jewish high school in Suceava and continued to live together to this day. We do not intend to tell about persecution, humiliation, and the Holocaust, but to mention them, because they should not be forgotten, but much has already been written about this. Therefore, we will relate our personal stories.

Fritz Herrer's childhood

I, Fritz Herrer, was born in Fălticeni, a town near Suceava. My father, Heinrich Herrer, was born in Suceava to a poor family who worked hard to make a living. My grandfather, Shmuel-David, was born in Rădăuţi. Together with my grandmother, Shifra-Sophie, they barely raised their four children.

My grandfather did not run his own business. He spent his entire life working as a broker between merchants, so the children had to work from a very young age and help the family. My father was the only one who studied after elementary school, with the support of both the parents and the three siblings, Sally, Julius and Martin, and reached the matriculation exams. However, he failed the Romanian language test and was left without a diploma. My father did his military service in Fălticeni, where he met my mother, Rivka Weiss, from a large family and married her.

After their marriage and lacking financial means, my father, together with partners, began several business ventures that were unsuccessful: a soap and candle factory, wood transport for which he purchased a large truck. Finally, he worked as a baker in a bakery in which he succeeded and the family's condition improved. Afterward, with a Romanian partner from the Blando family from Bosanci, he built a large bakery with two modern ovens. The business was successful.

My second grandfather, Moshe-Zvi Weiss, was an accountant and worked as an employee in a sawmill in a small village called Sasca, not far from Fălticeni. To support the family, he also ran

[Page 367]

a small grocery store in his home in the village, along with my grandmother, Etel Weiss. This grandfather was a religiously observant man who gave all the children a religious education. He also made sure that all the children, four boys and four girls, had a thorough education and a profession so that they could support themselves.

We in the family led a traditional Jewish life. At age four, I studied in Ḥeder and later took religious lessons with a private tutor and also at the Jewish-Romanian elementary school, supported by both the authorities and the [Jewish] community. I continued my studies at the government school until the outbreak of the war, when a “Romanization” policy began and expelled the Jews from the villages, including Grandfather Weiss.

|

|

| Dr. Regina (Weitman), Herrer, her husband Fritz and their daughters |

My father was taken hostage and transferred out of the city, along with other Jews, and then sent to forced labor in quarries in Bessarabia. We were expelled from our house and Romanian invaders from other cities came to occupy it. We, my mother, myself and my little sister Ida, moved into two small, low-ceiling rooms that were once the house storerooms. Mother was expelled from the bakery, but out of pity, they allowed her to be the bakery shop's salesperson. We were left destitute and with a very poor livelihood.

To help the family, I began working as an apprentice and a junior employee and over time as an electrician in a car repair shop. I remember Mother crying when I brought home my weekly salary

[Page 368]

and asked for two pennies to buy seeds, which were a delicacy.

The family from Suceava; my grandfather, my grandmother and my aunt Sali, and then separately, Martin, his wife and baby son were deported to Transnistria. Uncle Julius escaped in time from Suceava to Bucharest, the capital, and was saved from deportation. It was not until the spring of 1944 that the Jews returned from Transnistria to Suceava, along with the liberation forces that reached Fălticeni. My father came home and looked after our livelihood.

Because of its proximity to the front, they deported all the residents of Fălticeni to Suceava. Again, we were refugees, but free. After the liberation of Suceava, the liberation authorities, together with the [Jewish] community, opened a Jewish high school so that the students could complete their studies swiftly and without vacations.

Faculty of educators, teachers and professors, mostly Jews, helped us study to pass the exams. By the end of 1945, I could finish my high school studies and matriculation exams and continue with academic studies.

The childhood of Regina Herrer (née Sternberg-Weitman)

Regina was born in Suceava to the Weitman family and was the youngest of four children. The father, Susia Weitman-Sternberg, was the youngest of six brothers. He was an established merchant with forest plots and a partner in the “Weitman-Klueger” flour mill of Suceava. He was a religious man and together with mother they ran a religious household and observant life.

Mother Golda (née Schmeterling), was born in Poland and was the oldest of the siblings. When they were orphaned, the children were dispersed among the relatives in various countries, and so Mother Golda came to the Klueger family in Suceava. One brother, Srulzio, grew up in Zagreb, Croatia, and immigrated to Israel when the State was established. A second brother, Ḥaim, lived in Gmunden, Austria. A sister, Maltzya, was in Poland. Both perished in the Holocaust. Another sister, Regina, lived in Vienna, Austria, and fled to London.

Besides primary and secondary education, the four Weitman children received a religious education from an early age. Big Brother Bibi worked with father in the business. The other brother, Adolf, studied medicine in Italy and continued in Romania and was a young doctor even before the war. Sisters Pepi and Regina studied in Suceava and also cared for their mother, who was ill for a long time and died young before the war.

When persecution and humiliation against the Jews began, Pepi and Regina sisters also suffered from them and were expelled from school. Together with the Jews from Suceava, they, brother Adolf and Father Susia were deported

[Page 369]

to Transnistria and arrived in Shargorod. Older brother Bibi, who married after Mother's death, was also deported to Transnistria with his wife, Rosica.

Adolf, being a doctor, was the family's principal supporter and was very helpful in its support. Susia, the father, died in the first year, in the winter of 1942. The daughters Pepi and Regina were taken to forced labor in tobacco and potato fields. Sister Pepi married a Jewish-Russian engineer. Adolf and Regina returned home at the end of the war. With the retreat of Romanian and German soldiers and with the liberation forces, the Jews returned to Suceava.

In 1944, my brother Bibi and his wife Rosica also returned to Suceava. Adolf and Regina could not cross the border in time and remained in Bessarabia for another year. It was not until May 1945 that Regina returned to Suceava to an empty and destitute house. Sister Pepi, with a baby son, returned in October 1945 and began studying at the School of Medical Nursing. In 1951, she emigrated to Israel and settled in Kibbutz Beit Oren on the Carmel.

When Regina learned of the possibility of completing the studies lost during the years of persecution, she enrolled in the Jewish high school and began studying.

As fate would have it, and Regina and Fritz met in the school corridor. When she asked Fritz to help her with her math classes. He agreed and in return received a kiss from a beautiful girl. Regina successfully completed her high-school studies and matriculation exams and continued on with academic studies. Since she was an orphan, brother Adolf supported her all this time as much as he could, until her graduation.

Suceava's Jewish High School

With the support of the authorities and the [Jewish] community, the faculty of educators, teachers, and professors tried to organize and expedite the studies. Most of them were young Jews returning from Transnistria and nearby cities: Fălticeni and Botoḥani. They helped hundreds of Jewish students accumulate the missing knowledge in a short time and pass the exams. We will not forget the wonderful staff of Jewish teachers such as Dr. Rosa Levy, the Principal; brothers Chaim and David (Puyo) Rimmer, Ziggy Rohrlich, Berl Bogen and Otilia Rimmer-Bogen, Ephraim Weissbuch, Clara Sorkis, the Vigder sisters and Zlochbar and others. We will also not forget Prof. Nimiciano for mathematics; Prof. Dimitrov and Prof. Boroyana, who were not Jewish, but helped us a lot. They were all good educators and friends and they will remain in our memories as dedicated people who have tried to help us achieve a new life.

Since most of the pupils at the school were older and of different ages, we were organized in different groups, socialists and Zionists, causing a lot of problems and troubles for the school's management.

[Page 370]

But there was also another life outside of school that continued even after we started attending university.

In Suceava, we would organize cultural evenings and spend Friday evenings with friends. We got together with Picocha Sternlieb, by Toby Sternlieb's daughter, with Sylvia and Ralika Sternlieb's daughters; Reuven Sternlieb's daughters; or by Marion Nachgher, where we played cards besides dancing.

On these evenings, we told about our creations, and jokes related to Suceava. We laughed a lot about the content and the way the messages were delivered in Suceava in the years 1944-1945 by a drummer who could not read or write and ruined the messages and the Romanian language. And sometimes, he even held the pages upside down! We also laughed at the “pearls of wisdom” heard from some community leaders in Suceava and other places; stories about the origin of the sobriquet meshiga [auf] Schotz and about the “judgment” and more. In particular, we would dance and we could be without close family supervision.

There were other past-times as well: Walks down the main street and garden in the city center and ended up at Wagner's eating cakes, cream torts and cream puffs. We went to plays and movies at the “Dom Pulaski” and the “Central” and also toured Zamca, Arini or Chatata. We hiked to Iţcani on the Starka and also to Burdujeni via the bridge.

Both of us, Fritz and Regina, studied together and could finish the Jewish high school in the fall of 1945 and passed the matriculation exams at the Ştefan Cel Mare government school in Suceava. Later, in winter, we went to Iaşi and enrolled at the university.

Life as students in Iaşi

In the fourth year, before my graduation, we got married even though we were destitute. We invited the families to a wedding in March 1949. They were surprised and answered our invitation very late. My father wanted a rich bride for me, and Regina's sister wanted a prince, and I was not that.

We went straight from the class to the marriage registrar. Then, went back to classes and in the afternoon, we received the families who arrived by train. The wedding ceremony was held in my room and the “feast” was in Regina's living room. Since there were few guests, the rooms were big enough, food was brought from Suceava, so there was enough for everyone. We did not discuss suits, since I only had one suit for the day, but Regina had a new nicer dress. The photographer was a friend of ours and he only took one black-and-white photo. The rabbi was brought by my father, from the Rebbe's courtyard in Paşcani.

[Page 371]

Regina's brother, Adolf, was not established yet, but very close to us. He took off his gold watch and put it on my wrist as a gift. My mother took care of new bedding. Others promised, but forgot about fulfilling them. The next day, the families left and returned home. Only our friend, Picocha Sternlieb, stayed with us for a few days. I moved all of Regina's possessions: one suitcase, half were books and the other half clothing. And that was all. We were married. A place to live we had, and it was good that we were together.

As soon as I graduated, I began working in the railroad management of Iaşi in the electronics and communications profession. Regina continued her studies and also worked in the fifth and sixth year of the hospital, as was customary for medical students. Both salaries were low, but we led a modest life and it was enough for us not to be starving.

Life as employees and emigrating to Israel

In 1951, I worked as communications and automation engineer and control in the railway management. Regina was already a doctor. We got better; we had our first daughter, Sylvia, and we also got an apartment, albeit in an old house, but it was pretty good. Over time, we received good salaries, because we both made progress at work. The situation in Romania improved, and we made a decent living. The family grew. We had a second daughter, Gertrude, and we were content.

We were socialists in our opinions, but in 1958, we applied for a permit to emigrate to Israel for family reunification. We were dismissed from our jobs and given low-level ones. We continued our requests for 12 years and were refused eight times, but we did not give up. Finally, in 1970, we could leave Romania, only after giving up all our possessions and Romanian citizenship (Romanian citizenship was returned to us, at our request, after the change of Romanian government in 1989).

In September 1970, within six days of receiving the passports, anxious that we could not leave, we rushed and left Romania and emigrated to Israel. During those years of waiting for approval, we were already well known at the Israeli Embassy in Bucharest. We received books and other material from them to learn the Hebrew language, and they also enabled us to emigrate to Israel in a short time. Having in-demand professions we began working successfully; I as an engineer and Regina as a doctor in the Haifa area. It should be noted that it was not until 1970 that Srulzio met his niece Regina, Golda's youngest daughter, by chance, when he visited the clinic where she worked as a doctor.

[Page 372]

I would like to emphasize that we were immediately and nicely absorbed because we wanted to be absorbed. We worked without complaint, in everything and without over-reaching. Our daughters studied after their military service. Sylvia, Electrical Engineering in Haifa; and Gertrude, Medicine, in Jerusalem. They are both married and we have four grandchildren, two from each daughter. Karen and Zvi Lupo and Maya and Lital Roitman, who studied. They served in the army and continued their studies.

Despite the many difficulties, we believe that we have succeeded in life, contributed to the State and ourselves and become respected pensioners who enjoy our extended family that will continue growing.

Finally, we would like to remember that we left Suceava, but we will not forget the place of our childhood. After the long journey of 60 hard years; from May 1945, when we first met at the Jewish high school in Suceava until May 2005, we have made progress and feel free, citizens of our country, Israel. We will do everything for it to be strong forever, for us and for future generations.

My name is Felicits (Liztzy) Tekuchiano (née Weiner). I was born in 1929 to my parents Anna and Nathan Weiner in Suceava, where we lived on the main street (22 Regele Ferdinand Street) until the deportation to Transnistria.

First, some memories and nostalgia: my mother Anna Weiner (née Dalfen), born in Suceava; Grandmother Ḥayya Dalfen (from Ostfeld) was also born in Suceava. My father, Nathan Weiner, was born in Storozhynets, but lived in Suceava since 1926. My parents had a book and stationery store on the main street (Librăria Modernă Weiner). An entire generation of kids and young people who went to school passed through our store. We knew everyone, and everyone knew us. Because of the type of store, selling books and newspapers, a lot of acquaintances would come in and talk about the situation in the city and politics and many things. I remember Libby Schaerf, reading a poem he wrote when the treaty between Russia and Germany was signed in 1940. I even remember the line, Verträge sind Fetzen Papier (Contracts are scraps of paper), to this day I do not know if it is original.

[Page 373]

|

|

| The Weiner Family Bookstore |

As for my childhood, it was like most of us. I was in the wonderful Isolis' kindergarten, which was conducted in Hebrew. It was a traditional kindergarten with many Hebrew poems, and a lot of stories from the Bible, which are my primary education in this area. I remember Purim and Passover celebrations with costumes and customs, the gymnastics we did at Maccabi, in the building of the Jewish community with the teacher Tennenbaum. I remember my parents would sometimes go to WIZO in the evenings to learn Hebrew, and we children, we took Hebrew lessons with the teacher Miller, who later perished in Czechoslovakia. The teacher that I studied with, Lichtbaum, did not return from Transnistria. The atmosphere was to give a good, secular, Romanian education but also a lot of what relates to the Jewish People. My parents were not religious, only traditional, but celebrated all the holidays in the GACH Synagogue. While the parents prayed, we children played in the synagogue courtyard. It was unforgettable. Apart from the prayers, it was a social gathering for adults, especially for the women. The men prayed all the time and the women also chatted a little.

I remember the summer trips to Zamca and the nearby fortress or carriage ride to the Suceava Stream. Another experience was visiting a restaurant in the garden at Hersh-Mendel Wagner's, who fired up an excellent grill or at Wagner's pastry shop in the basement with its wonderful cakes. There were many Jews, and the economic situation was pretty good. All the shops on the main street were Jewish, and the atmosphere was friendly.

All of this was true until the war. In 1940, The Legionnaires came to power. The [Jewish] children were banned

[Page 374]

from schools. Business had a lot of problems. The first deportations started in the surrounding villages. In October 1941, all the Jews from Suceava were sent to Transnistria. In Transnistria, our family came to Djurin where we stayed with my grandmother Bracha Weiner and my uncle Benjamin (Zigo) Weiner. The situation there is known to all of us. Forced labor for men by the Romanians and Germans, little food and a plenty of disease.

The whole family survived and returned in 1944 to Storozhynets in northern Bucovina, and in 1945, to Suceava, with nothing. Our apartment was no longer vacant, and we got two rooms on the same street.

I was 15, after finishing four grades in elementary school. In Suceava, the wonderful intervention for refugees was already functioning: Liceul Evreesc de Stat cu Drept de Publicitate; the well-known private Jewish high school. I covered six grades in one summer and was then able to integrate with my peers in the same school. I graduated in 1949 with a regular matriculation from the great Ştefan Cel Mare State High School.

I am going to move now to a very significant time in my life. In 1945, I joined the Zionist Youth movement, which influenced all my thoughts and planted a great love for Eretz Israel. It was an experience for the youth and a great deal of Zionist education. I remember that is where one emissary taught us that there are “two banks to Jordan, but we cannot get it. We have to take what we can, and over time, at every opportunity to expand a little.”

My uncle, Benjamin Weiner, who was active in the Beitar movement before the war and head of the Branch in Suceava, emigrated to Palestine in 1945. I tried to emigrate to Israel in 1949, and took part in the training of the Zionist Youth movement in Moldoviţei, Bucovina. I could not emigrate because of the cessation of Aliyah to Eretz [Israel] and returned to Suceava. Later, I enrolled at The University of Iaşi, in the Faculty of Chemistry, and I graduated in 1953.

In 1952, I again registered up for emigration, but my request was denied. This registration caused me many problems in getting work, but I finally emigrated to Israel in December 1963. We lived in Nahariya for a year, then 8 years in Kiryat Yam, and finally moved to Kiryat Ḥaim. After 5 years of looking for jobs and frequently changing them, I was hired as a chemist, in a laboratory in the HMO, Carmel Hospital. I worked there for 22 years until I retired in 1990.

In 1999, my husband Florin Tacucciano died, and I remained a widow after 37 years of marriage. I have a married daughter, Bruria Peled, and three grandchildren. The oldest of them is in the army. Indeed, in Eretz Israel, I eventually got along. My children are in Israel and my grandchildren.

[Page 375]

I was born in 1910, and now have vision and hearing problems. I remember that after World War I, a successful high school was opened in the Jewish Community Center under Prof. Halperin. The lessons were in Romanian. Apart from the usual subjects, there were lessons on Judaism and languages: Hebrew, French, English and German. It was a private school, and the tuition was very high. So, neither my sister Clara nor I could attend.

My cousin Yisrael Rachmut, later a member of the Romanian Academy, studied there for five years. But his brother, Karl Rachmut, only studied for one year. The school operated for eight years until 1928.

In Transnistria, I stayed in Shargorod, where I opened a kind of school without a chalkboard, in a room where my sick father was lying, with only a table and two benches. The children did not have books, nor notebooks and no pens to write, but they were eager to learn.

I taught them everything I knew. Since then, I had always been teaching children. After World War II, a Jewish high school was opened to enable students who had been exiled to Transnistria to complete their studies. The school operated for about five years and was headed by Dr. Rosa Levy for several years.

Translated and adapted from Romanian by Simcha Weissbuch

My family

My maternal great-grandfather, the late R. Moshe Mordechai Gertler Halevy, after being widowed, he emigrated to Israel in 1908, died in Jerusalem and was buried on Mount of Olives.

My grandfather, the late Naḥum Gertler Halevy, after several years of intensive Torah studies, studied a profession and chose bookkeeping. He served as chief accountant at a leather processing plant owned by the Sternlieb family, excelled in his role as a professional and trusted peson. He later became independent and with the help of his wife (my grandmother Ester) established a large textile trading house where his son Mordechai Gertler, his daughter, the late Hinka Unterport, and her late husband Yaakov worked.

[Page 376]

|

|

| Yosef Vizhnitzer |

My grandfather was known as an honest and decent man regarding weights and measures, and product quality. So, most of his clients were the German villagers (the Schwabians) who preferred a quality product at a fair price. Despite his many pursuits, he devoted time to studying Torah and Talmud studies. Every Shabbat, he would host a guest who had come by chance to the synagogue.

My late father, R. Nathan Neta Vizhnitzer, born in Horodenka (Galicia), arrived at 17 as a refugee at the end of World War I to his aunt Pearl Reicher, my grandmother Mariasi's sister, who lived in Bischetti. Thanks to his auto-didactic talent, he learned German, Romanian and Hebrew languages fluently besides Polish. He married my late mother, Haitze (Clara). They also ran a textile shop. My father was also known to be a prayer leader and was in demand during the High Holidays.

After the Communist regime came to power in 1948, my father taught Hebrew and grammar, thus instilling the Hebrew language to many Suceava emigrants before their emigration to Israel. After emigrating to Israel, he served as a teacher in the Talmud Torah in Ramat Vizhnitz in Haifa.

My uncle, Moshe Naḥman Gertler obm, graduated from electrical engineering in Austria and after his marriage moved to Czernowitz, where he became a representative for the Columbia Company.

My late uncle Chaim Boiman and my late aunt Yocheved were engaged in business and ran a large men's clothing store. My aunt died in the summer of 1941 before the deportation to Transnistria. The president of the Mizrahi movement in Schotz was my Uncle Ḥaim.

[Page 377]

My days living in Schotz were few and harsh ones, about 12 years, so the memories are mostly from my childhood and my youth. The house in which we lived was in the courtyard of the late Admor, Rabbi Yankele Moskowici of the late Rabbi Meir of Przemyślany dynasty. His followers (ḥassidim) were mostly from the surrounding area. He was a great host. His home had a special kitchen for the poor and guests from the surrounding area. And very famous are the wonderful stories of Rabbanit Hayaleh (the grandmother of Rabbi Yankele and the daughter of Rabbi Meir of Przemyślany) who would work magic with a stick in her hand.

Other experiences in the Rabbi's court were baking the matzah under his direct supervision and the exciting prayers during the High Holidays in the Rabbi's synagogue; the hustle and bustle and running around decorating of the large and beautiful Sukkah, the laps celebrated with a crowd on Simḥat Torah that attracted a large crowd from all around (including Christians). Also, the Purim days with the reading of the scroll [of Esther], the costumes, the competition in delivering food gifts, and the traditional Purim party.

The Admor with his family emigrated to Israel in 1951 and established their residence in Haifa on Hillel Street. Part of the apartment was used as a synagogue even after his death. This synagogue served as a place of prayer for many ex-Suceavas after emigrating to Israel. His son, Zalman Leib obm, served as a secretary of the Religious Council in Haifa in the 1970s. The Admor's son-in-law, the late Rabbi Frankel Mordechai of Botoḥani, after emigrating to Israel, served as rabbi of the French Carmel neighborhood of Haifa.

Among the worshippers in a synagogue near my residence were also: R. Gershon Hadayan, father of the late R. Simḥa Stettner and grandfather of the late Boumi Stettner, R. Yoel David Schwarz, late gabbai of the synagogue, and his brother Meir Schwarz, a scholar. I remember him leading prayers during the High Holidays wrapped in his talit, covered head to toe while singing the Piyyut lel orekh din. His voice sounded as if it was coming from heaven; the women weeping from the women's section. R. Yosef Lacks, who has an excellent prayer leader, the father of the late David Laks and the grandfather of Leibele Laks, R. Shimshon Zwerling, a scholarly kind man. I especially remember the elderly figure of R. Shamai Schapira, the father of the late Meir Schapira, the founder of Yeshivat Hochmei Lublin, as well as his son-in-law, R. Berl Liquornik obm.

The harsh memories, the gloomy clouds that heralded the coming of the period of persecution and extermination, actually gathered a few years before the expulsion. I remember going to elementary school in second grade and seeing convoys of the remnants of the Polish Army (officers wearing hats with a cross painted on them) on the main street of the city, who apparently crossed the Romanian border while Romania was still neutral. Then the Axis armies approached the Russian border, showing the coming outbreak of battles.

[Page 378]

I remember the anxiety that gripped my parents on Thursdays (market days) seeing the villagers from Zahareşti and Comăneşti entering our shop. Pogroms had been carried out in these villages, killing many Jews, including the Schaechter family from Comăneşti.

In the summer of 1940, I was expelled from elementary school, from third grade. Before the suppression of the uprising of the murderous Iron Guards in January 1941 by the Romanian Army, they carried out pogroms and other riots against the Jews. We, in Suceava, also suffered at their hands. The arrest of the “hostages” in the summer of 1941, who were imprisoned in the study hall near the Great Synagogue with poor sanitary conditions and in stifling heat. The “hostages” were chosen from among the affluent Jews. Those with status and influence, who were guarantors of the peace for the Romanian and German soldiers. Among them was my uncle, the late Ḥaim Boiman.

After battles broke out with the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, we would follow the newspapers on the rapid progress of the Axis armies toward Moscow. I remember the notorious newspapers such as “Curentul”, “Porunca-Vremii”, “Universul”; the more moderate newspapers like: “Timpul”, “Adevărul” and “Bacăul”, “Iaşul” that we bought.

Deportation to Transnistria

Much has been written about it, but several events were etched in my memory as a child. The announcement of the deportation by the drummer in the town square (the same drummer later served as mayor on our return to Suceava in the summer of 1944). The despair and panic that gripped everyone because zero hour was set at 17:00 for our arrival at Burdujeni train station. We arrived at Ataky on Friday night. Shots in the air, robbery by the mob waiting for the train's arrival, and the terrible continuation of that night in the ruins of the Ataky synagogue.

The bold stance of my late grandmother Ester, who despite the prohibition of carrying Romanian money and the obligation to convert it to the “Occupation Zone Mark”, carried it with her. This despite the entreaties by family members. In fact, with this money, we survived during this difficult time.

The next day, along our walk from Mogilev to Ozaryntsi, we discovered horrific scenes: people who were taken out for overnight transport from the infamous barracks and deliberately put into swamps. The upper parts of their body were discovered floundering and crying out for help without our being able to save them. Among those who perished from transport was R. Yosef, the ritual slaughterer. When we arrived in

[Page 379]

Ozaryntsi in the evening, broken and exhausted after an arduous journey on that terrible day, while searching for a night hostel, we heard familiar voices of joy and festivity in the darkened town. We approached the epicenter of joy and revealed to us an impossible sight for those days: The late Rabbi Yeshayahu Gross enthusiastically leading Simḥat Torah circuits with the participation of a large crowd. Indeed, they were all among those driven in the night convoy whose terrible traces were revealed to us the next day.

After a long journey with intermediate stations, Mogilev-Lucinz-Zagir'ye, we reached Shargorod. I especially remember that first winter of 1941-1942, the typhus epidemics, famine, and cold that felled many casualties. Despite the significant risk of contracting serious illnesses, Doctors from Suceava risked themselves providing medical help. Some of them perished. We went through harsh years there.

The liberation and return to Suceava

The coming liberation days were full of anxiety and tension. The movements of the German and Romanian military in different directions and the lack of minimal communication caused various and terrible rumors to spread, such as that with the withdrawal of the German Army, SS units were raiding villages and executing the surviving Jews.

On the morning of liberation day, there was complete silence in the town; literally a ghost town. The Jews gathered at the city's edge to find out the meaning of the silence. Suddenly, intermittent automatic weapon fire was heard. Everyone dispersed in all directions, feeling that these shots confirmed the rumors that had spread. In the end, it turned out that it was partisans shooting at German soldiers found in the area. Liberation Day itself is memorable, the sight of a jubilant crowd greeting the liberating Red Army.

The return to Suceava was also full of hard events such as the anxiety of kidnapping to Donbass, traveling at night on trains full of soldiers, armor and fuel containers, threatened by enemy aircraft circling above us. There were also cases of robbery along the way by Red Army personnel, who were mostly looking for tobacco and watches.

It took several weeks with stops at Mogilev, Secureni, Lipkani, Noah-Suliei, Czernowitz and Mehilen. The road from Mehilen took one long summer day and was littered with the Red Army. The roads were laden with tanks, infantry and cavalry

[Page 380]

as we rode on our meager little cart and tried to make our way through the hustle and bustle. Despite everything, our spirits were high, full of great expectations and hope as we approached our destination. In the afternoon, we reached the Burdujeni Forest, which was full of various army units. The wagon owner, who brought us from Mehilen, refused to go the short way to Suceava because of fear of the Russians. We were told that the bridge over the Suceava [River] was blocked by the army. Only after running around and bribes, we succeeded to cross over this bridge as well. Excited but exhausted, we arrived in Suceava. We thanked God that he returned us whole and healthy to our home. We were among the first who returned to Schotz in May 1944 before the border was closed, which was only reopened in 1945.

We were happy to find our house in good condition thanks to the rabbi of Fălticeni and his family, who lived there at the time after they were expelled from their home and transferred to Suceava. The next day, I took a tour of the city with my parents. We were thrilled and excited and could not believe at first sight that we were fortunate to return from the inferno.

Until August 1944, Suceava was blockaded. Almost every evening, German [planes] flew over the city for patrol and intelligence. City services such as water, electricity were out of order and were only restored in 1945. Large military convoys of infantry, cavalry, armor and artillery moved toward the front that had halted at the Carpathian foothills (Kachike). There were also large groups of German and Romanian prisoners-of-war that were transported to enc;osures in the area. But the feeling of being under siege, the front's closeness, and the cannon's roar did not cloud the joy of our homecoming. Of course, we did not know, nor could we imagine, that at that very time, the Germans began transporting the Jews of Transylvania to Auschwitz.

The [Jewish] community arranged setting up a Jewish school. We had to complete the three-year lag of Transnistria. We did so with great effort from 1944 to 1947. So, it is worth giving a good mention to the teachers who helped and encouraged us: Dr. Levy, the first principal of the mixed high school; after her, Mr. Schulman; Mr. Bogen and his wife. He was the history teacher, and she taught mathematics; Mrs. Sorkis, Latin teacher; Mr. Weissbuch, Hebrew and history of the Jewish People; Mrs. Nussbrauch, physics teacher; the Rohrlich brothers, French and Russian teachers; Mrs. Vigdor, physics teacher; Mrs. Schmelzer, philosophy teacher; Mrs. Zlochiver, civics teacher, and others who slip from my memory. I would also like to mention favorably the Romanian teachers who contributed their share in making up our lost school years.

[Page 381]

The Yearning and emigration to Eretz Israel

At the end of August 1944, with Romania severing its ties with the Axis powers, a large Romanian Army unit entered the city accompanied by a military band marching smartly in the best Romanian tradition. All of which was done to gain control over the city. In the eyes of many, and I as a 13-year-old, we saw this show as a strange yet funny event, and perhaps a harbinger of what was to come. This army, which only a few weeks ago had been defeated, humiliated, hungry and neglected; its captives led through the city streets, burst out in all its glory as a victorious army.

So, the euphoria that gripped us on our return to Suceava quickly dissipated. We realized our stay in the city would be a short and temporary one. Thanks to my membership and activity in the local Bnei Akiva ken, I was privileged to be among the emigrants of the Pan ships. It was under the Youth Aliyah framework, emigrating without our parents.

On Tuesday evening, December 22, 1947, I said goodbye to my parents and family and set out on a journey. I was full of hope and elation, even though the separation from my parents and the extended family was difficult. It clouded the festive event. It was customary to send the children ahead even if it was the family's only child. Although I was hoping for a quick family reunion, my reunion with my parents and sister only took place 11 years later. Because in those days, the means of communications were extremely limited; a letter arrived only after a month and a half, the disconnect was almost complete, painful and worrisome.

We got on the special train for the emigrants to Eretz Israel. The Mizrahi movement's emigrants were assigned a whole train car. The late Mr. Alexander Marilus was in charge. After 48 hours of tiring journey (until Thursday evening) but in an uplifted mood, we arrived at the port of Burgas in Bulgaria. The two ships anchored in the port were lit up. They appeared to me to be the biggest ships in the world. I went up the steps of the Pan York. I carried with me on board besides my backpack, two bags full of “snacks for along the way”, which my late mother attempted to equip me with. But here, by instruction from the stewards (Aliyah activists), I was unfortunately forced to part with the two food-laden bags. I had barely recovered from the loss of the bags when I was suddenly carried away and thrown on to one of the bunks inside the ship. After a long while, and the shock wore off, I got off the bunk and started to check out and get to know my surroundings. I went up on deck, finding it buzzing with people and youth. It then became clear to me that people who arrived later had to settle for just staying on deck despite the harsh weather conditions, cold and rain.

On Friday, full trains, mostly from Transylvania, continued to arrive. On Saturday afternoon, after the last train arrived, the loudspeakers announced that the two ships were about

[Page 382]

to set sail. Everyone who could tried to get on deck and I was among them.

Before the ships sailed, the blue and white flags were hoisted on the masts and a tremendous singing of the “Hatikva” burst out. Meanwhile, Bulgarian Army officers stood on the pier saluting the blue and white flag. Knowledgeable people said that also the late Moshe Sneh was also present on the pier. He was, in fact, responsible for organizing the operation to bring 16,000 immigrants on the two ships. For me, the little boy from Schotz, a “Transnistria veteran,” this scene of gentile officers saluting the blue and white flags accompanied by the “Hatikva” was thrilling, tearful; a kind of “Dayeinu...”.

During our voyage, we heard about events in Romania: the expulsion of King Mihai and the rise of the Communists to power, with the Jewess Ana Pauker as Foreign Minister. Only then we understood we had almost missed the train.

At the Bosphorus Straits, we were greeted by two British destroyers, and after two days, their number increased to seven. It was told that the commander of the British fleet asked the commander of our two ships whether it was an Aliyah or an invasion!

After sailing for a week on bunks, we arrived safely in Cyprus on January 1, 1948. We were placed at Summer Camp ¹ 55. They threw us tents, iron beds and blankets. We had to set up the encampment by ourselves.

Those who arrived with their families were better off and more comfortable. But for us, the Youth Aliyah children, the situation was difficult; hunger especially bothered us. The hope for imminent emigration made it easier for us. In March 1948, according to an agreement with the British, and as part of Youth Aliyah, we left the island and arrived at Tel-Aviv port, because Haifa port was blocked because of the battles to liberate the city taking place.

It is difficult to describe the excitement that gripped us upon our arrival in Tel-Aviv. We did not know if this was a dream or reality. We were moved by the warm welcome and rich refreshments we received from the WIZO women. I can still recall to this day the taste of fresh sandwiches after the period of famine.

The road to the immigrant camp was interesting. Initially, we were transferred to buses and got to know the Egged drivers. We were impressed with their outfit: the hat, shirt and khaki shorts. We saw on our way some streets of Tel-Aviv, Ramat Gan, and Petah Tikva. The Sharon orchards made a lasting impression on us. The Sea Coast Highway did not exist yet.

We spent a few weeks in the immigrant camp. The first Passover in Israel and the great Seder held in the camp's dining room was an exciting experience. However, the peak was on Friday, May 14, 1948. At 4:00 P.M., all the immigrants were asked to gather at the camp's large field

[Page 383]

to listen to the direct radio broadcast of the declaration of the establishment of the State of Israel by the late David Ben-Gurion. These were heart-wrenching moments that brought tears of joy and emotion to our eyes.

|

|

From the right: Top row: Clara Kaufman, Sidi Hollinger, Meir Schweizer, Yosef Vizhnitzer, ?; Middle row: Rut Klein, Giza Niederhopfer, Marta Marilus, Hana Itzcovici, Tillinger; Seated: Mrs. Niederhopfer, ?, Mrs. Hollinger |

In August 1948, we arrived at the Mikveh Israel Agricultural School and were accepted as students of the 28th class in the religious immigrant youth sector. This period of school was one of the most important in our lives for us. It helped with our rapid absorption in Israel. In a short time, we got to know and appreciate the Hebrew youth and keep up to date on what was happening in Eretz [Israel].

One phenomenon that astonished us was precisely the proficiency of the students from the secular sector (natives of Israel) in the Bible. In our meeting with them, they recited entire chapters from the prophets of Israel; Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. We remained open-mouthed. I wish it were so today.

Studies continued until May 15, 1950. During this period, we took part in GADNA training and guarding the liberated areas such as the Pillbox on the Jaffa border. The 28th class included five pupils from Suceava: Sidi Hollinger, Rut Klein, Clara Kaufman, Giza

[Page 384]

Niederhopfer, Yosef Vizhnitzer, and myself; almost 15% of the class. Hana Itzcovici and the late Berta Wald were in the 27th class.

A story related to our time in Mikveh Israel indirectly concerns the veterans of Suceava. But it is doubtful that it is widely known: One day after a short study period, we were astonished to hear that Mr. S. Rabinson, the Bible teacher, a mild-mannered and quiet man whose lessons were fascinating, was the brother of Ms. Ana Pauker, the Foreign Minister of Stalinist Romania. He lived with his family in a modest apartment in the school compound with his father, Ana Pauker's father; an impressive Jew with a long beard. Every time I met him in the school synagogue, I struggled to believe that there was a connection between him and his daughter (the Foreign Minister...).

In the summer of 1949, Mr. Rabinson was replaced by another Bible teacher, and his family also disappeared. Rumors circulated (that were later confirmed) that Mr. Rabinson had been sent on a mission by the Israeli government to Romania in order to influence his sister (Foreign Minister...) to allow emigration [to Israel]. His efforts bore fruit, and from the winter of 1949, the ship Transylvania anchored in Haifa port almost every month or more often. Some of the school's students, such as Sidi Hollinger and Giza Niederhofer, also got to see their parents before the graduation and their mothers even participated in the graduation celebrations.

Because of his mission, Mr. Rabinson was arrested and imprisoned in a Romanian prison for several months. A few years later, I met him in Haifa and he was thrilled to see me. We exchanged impressions and memories of Mikveh Israel.

My paternal grandparents came to Bucovina during the first half of the 19th century and those on my mother's side came in the second half, from the city of Salesclerk in Galicia. They were poor and settled in the village of Bosanci in the Suceava District, where more affluent relatives lived. Because Bucovina, which was under Austrian rule between 1775 and 1918, had a higher standard of living than that of Galicia and Czarist Russia, the Jews preferred to move there.

[Page 385]

|

|

| The late Dr. Adolf Weitman and his wife Coca |

Mother had five brothers and sisters. Her parents died young and were buried in Suceava. My paternal grandfather spent a lot of time on religious studies in the synagogue and lived modestly. He also had six children. After they married everyone off, he and his wife went to the Holy Land to end their lives there. They were buried in the Promised Land. All my investigations in Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias to discover their burial place were unsuccessful.

My brother Bibi obm was born in 1911. I was born two months after my late father was drafted into the Austrian Army in 1914, at the outbreak of the World War. Father fought in Italy on the front line by the Drava River, where he was wounded. He was discharged from the army toward the end of the war in 1918.

During the 59 years I lived in Europe, antisemitism has been an endemic disease and like a leitmotif throughout my life, from childhood until I permanently left Europe near old age. The instances I suffered as a Jew left a deep scar that has accompanied me all my life.

As early as four, in 1918, when Bucovina was supposed to be transferred to Romanian rule, several residents, led by a peasant family called Bursuc, decided one night to carry out a small pogrom against the Jews. I remember Mother hiding me in the basement. From there, I heard shattered windows in Jewish apartments. After that, dozens of Jewish families (except the Gingold family) left Bosanci and moved to Suceava.

[Page 386]

|

|

| Eugene Weitman at his wedding |

In Suceava, my parents had two more daughters in 1920 and in 1921. The first, Pepi (Pearl) who later became a nurse and the second, Regina, became a doctor. My bearded father was a ḥassid of Rabbi Friedman of Pashcani. The house had a traditional religious atmosphere and kept kosher. Father prayed in the synagogue every day, as well as on Saturdays and holidays. When Rabbi Friedman visited his ḥassidim in Suceava in 1925, he stayed with my parents and attended our house warming. He blessed me to succeed in the entrance exam for the first class in high school.

We all went to the city's elementary and high schools. My sisters learned their first Hebrew words in the Jewish community's kindergarten and later studied with private tutors to read in Yiddish. The language of instruction in the schools was Romanian. My sister Pepi attended a nursing school in Bucharest led by the Beitar youth movement. My brother and I first studied Hebrew with tutors, and then we went to study at a higher level in the Talmud Torah. I continued until before the matriculation exam to study Bible, modern Hebrew, grammar and literature with private teachers.

After Romania took over Bucovina, the influence of 143 years of Austrian rule was still felt. The little German boys, from whom the Romanian children also learned, shouted at us HEP-HEP;

[Page 387]

short for the antisemitic slogan Hierosolyma est perdita (Jerusalem is destroyed). In Suceava, there was a German football club named Jan, named after the renowned gymnast Friedrich Jan. At football matches between Maccabee Suceava and the Jan teams, the chants of HEP by the German team's fans did not stop for a moment, to our great sorrow.

In the last class of the elementary school, a fight broke out between Jewish and Christian children. It was called the “Battle on Bosanci Street.” The leaders of both groups were questioned. The person found guilty was, of course, the Jew Weitman, who was “rewarded” with 20 lashes by Teacher Olynyk.

At Ḥtefan Cel Mare High School, a teacher, Giorga Karlan, was a member of the antisemitic extremist movement “The League for the Protection of the Christian Nation.” He was my homeroom teacher, and in the first hour, he kicked me out for a week, claiming that I had met him on vacation and did not greet him. I went to another high school but lost a school year. During all the time I studied at this high school, not a day passed that Jewish students were not bullied by the calls of Jiddan (Jew-boy) or Juda, an allusion to Judas Iscariot who betrayed Jesus.

In the middle of my high-school years, I became a member of the Religious Youth Movement. A few years later, I moved to the Beitar movement, which had been recently founded in 1930. Twice I was commander of the Beitar in Suceava and a member of the Bucovina district leadership. I was active until the end of my medical studies in 1939.

At the end of my six years of studies in 1939, World War II broke out and some Jewish colleagues sought to be accepted into modest positions. Former pediatrics professor Jon Nicolau, a Democrat and an associate member of the Romanian Academy, who has meanwhile been appointed general secretary of the Ministry of Health, tried to help. After many days of procrastination, he told us: “Sorry, I wanted to help you, but it's impossible and you know why.” The pogrom spirit is blowing across the entire country against the Jews and harsh decrees have been placed against the Jewish communities. The sign of my clinic had to be followed by the notice “Jewish Doctor” with a Star of David. I had to wear a yellow Star of David patch on my lab coat, and it was forbidden to treat Christian patients.

|

|

| Erich Heitel (on the right) and Dr. A. Weitman |

[Page 388]

In 1941, I was once detained by a patient after the hour that Jews could travel outside. On the way home, I was stopped by police and detained along with drunks and thieves, all Christians, until the next day. In the morning, the first thing the officer asked me was which of the detainees was not Romanian. I could barely convince him I had been detained by a pitiful patient. In the end, he did not send me to the military court. Another time, before the deportation to Transnistria, I met at a crossroads in Suceava, a former colleague, Hannibal Lucescu, in the uniform of a military doctor. When I greeted him, he replied: “Măi jidane, mai trăieştiḥ” (Jew-boy, you're still alive?) and we continued, each one on his way.

In the deportation, I was with my family in Shargorod and there we went through hell. When I accompanied my late father Susia on his last journey, there were piles of corpses that had not yet been buried because the ground was frozen and the undertakers had difficulty working.

|

|

| Dr. Adolf Weitman with Marc Chagall |

After the liberation by the Russian Army in March 1944, those who survived the deportation returned to their homes. We hoped that the Jewish Problem had finally been solved under the new regime. But with renewed antisemitism, Jews were expelled from their jobs and accused of being from “unhealthy social origins.”

A few months after I returned to Suceava, I was accepted, after a tender, in the surgery department at the local hospital. I worked here for 28 years until I emigrated to Eretz [Israel]. Over the years, I served as director of the Surgery Department, senior physician, and also hospital director.

[Page 389]

In 1945, I married Coca (née Bandit) from Fălticeni, the love of my life. My only son, Eugene Alexander, was born and is now a Building Engineer. He chose this profession, hoping that he would be in great demand in Israel. Our son immigrated to Israel with us on October 4, 1973. The granddaughter of Bezalel Weissberg is married to him. He has been working for 18 years as chief engineer of the Amal school network, and they have three children: The eldest lives in Jerusalem and is married with three children. He studied international relations at the University of Geneva and is now completing his studies in economics. The youngest is in the Army, in the Armored Corps. The daughter, after completing her army service, is studying chemistry at Tel-Aviv University.

All members of the immediate family, my brother, sisters and myself, have concluded that the only solution for the Jewish Problem is the State of Israel. And so, for over twenty years, we have all left the city of Suceava and reach our destination of our longings, to our home country, the State of Israel.

Know where you came from

(Avot 3:1)

From my late father's family

My paternal great-grandfather, Simcha Weissbuch (1856-1922), after whom I was named, was a scholar, married to Rachel, a righteous woman who discretely served meals to those in need. His first-born son Levi Yitzchak (1876-1936), my grandfather, was married to Krentze (née Bleiman) and had two brothers, Moshe Ḥaim, a shopkeeper in Burdujeni, who died in Romania, and Henich (Heinrich), who died in Israel.

My grandfather had four children:

Daughter Rosa (1898-1972) was married to Reuven Sternlieb and they have two daughters, Sylvia and Rachel (Rela), (See articles about them) and the youngest son Shimon, father of daughter Hannah, (she has a son, Meir) and Reuven, a son from a second marriage, who is a graduate of Yeshivat Hesder, a Torah Reader and law student.

His son, Ephraim Ḥaim (1902-1984), my father, who married my mother (1902-1983) Hana (née Weitman).

Abraham, a physician, lived in France before World War II, and perished with his wife and two daughters in the Holocaust.

His son Saul, an engineer, also lived in France, survived the war, but died shortly thereafter when he intended to emigrate to Eretz [Israel].

My grandfather, Levi Yitzchak, had several brothers and sisters: Moshe, Jonah, Tauva, Haya, Jetti, and Ḥaim-Leib.

[Page 390]

|

|

| Ephraim and Hana Weissbuch |

Moshe and his wife Fani had a son Michal, who died very young (1918); David (1908-1995, married to Amelia) fought in the Spanish Civil War alongside the Republicans and later, in World War II was a member of the French Resistance; daughter Hana-Reisel (1910-1952, married to Lionel Shein and their daughters Stefania and Shoshana); and daughter Aliza (1915-1991, married to Marcel Helsinger, had a daughter Nora and grandchildren Gal and Dror). From Moshe's second marriage (to Anna), a daughter Rivka (1916-2000, who married Fritz Greenwald and they have a son, Raanan and two grandchildren, Abigail and Aryeh); and son Yitzchak/Andy (1921-2000, married to Edit and father to Jonah and Rami). Yitzchak was president of Hechalutz and a leader of the Bnei Akiva movement in Romania.

Jonah (1888-1954) was married to Maria and their daughters Fani (1915-1971) and Shelley. Fani was married to Raul Jowell and the second daughter is married to Architect Aristide Streja, author of Synagogues of Romania. They have a son who lives in the United States, and two granddaughters, Jill and Lynn.

Taube died childless in 1954.

Haya is married to Moshe Segal. Their son Ḥaim (1920-2000) and his wife Paula had two sons, Morel (father to Shmulik and Maya) and Pinḥas. Haya's other daughters were Feige and Miriam. Feige is married to Yaakov Tal and has sons Yoni and Doron. Miriam was married to Anchel Daphne and they have a daughter, Liora, and a son, Yaron, and eight grandchildren.

Jetti was married to Adolf Acks and their son Ben Junis (see separate article about him) and a daughter, Dr. Liza Stolano. She and her husband, Dr. Adolf Stolano live in Bucharest.

Ḥaim Leib (1902-1983), a scholar, Hebrew teacher, cantor, preacher and mild-mannered man,

[Page 391]

a founder of the Beit Avraham Synagogue in Kiryat Ḥaim. He and his wife Sarah (Sofika) had two daughters: Freida, who died very young (1930-1946) and Sylvia, who was widowed from Moshe Scheinfeld. Their daughter Gila is married to Oded Bergman and is mother to Shani and Karen.

From my late mother's family

Great-grandfather Avram Yaakov Weitman and great-grandmother Rivka came to Israel around 1910, died here and were buried in Hebron or Jerusalem. They had three sons: my grandfather Yitzchak Aryeh (Leibish); Shia (father of two daughters), and Susia (father of two sons and two daughters); and four daughters: Feige (later Salpeter, mother of four daughters); Tzipa (later Marling, mother of two sons and two daughters); Leah (later Weichsblatt, mother of a son and three daughters); and Sarah (later Schmelzer, mother of three daughters). Leibish and Shia are buried in Suceava and Susia in Shargorod. Feige and Tzipa emigrated to the United States in 1919, and both died there. Leah and Sara died in Transnistria.

My late grandfather Leibish (1878-1950) was an observant, cherished the rabbis, owned fields and forests around Suceava, and established, together with his brother Susia and his cousin Selig Klueger, a flour mill in Suceava.

His wife, my grandmother Golda (1878-1962), was the daughter of Shraga Feibisch and Liyoba Mancher. She had a sister, Tzipa (Riva's mother), a brother Yossl (father of Shimshon, Dina, Esther and Rosa), brother Benjamin (father to Gita and Shraga), brother Selig (father to Helena and Shraga), sister Dina, and sister Bila (mother to Rosa and Dudel).

My grandfather had seven children (five girls and two boys): Hannah, Coca, Penzia, Jeanette, Rut, Shimshon Dov (Simon) and Yosef.

My mother Hana was grandfather's eldest daughter. She was born in Bosanci near Suceava. Coca (died very young), Penzia (she was paralyzed in the lower limbs and died before World War II), Jeanette/Yaffa, was married to Ḥaim Sofinboim and died in Israel in 1982. They have a son, Yaakov / Jaro (1938-1985) and grandchildren, Guy, Assaf and Aviram.

Rut (later Baer) died in 1982. She had a son, Asher.

Shimshon Dov / Simon (1912-1975) was married to Rut (née Ellenbogen), who lives in Germany. They have a son, Aryeh, who lives in Herzliya and is father to Shimshon and Maya. Daughter Gita lives in the United States, is mother to Ryan (who has a daughter, Michaela Hanna) and David who emigrated to Israel. Simon passed away in Germany and was brought to rest in Israel.

[Page 392]

Yosef (1924-1992) was married to Rosa, who was widowed by Zelig Schmelzer and has a daughter Ḥayya (mother of Zavit and Lior and grandmother of three grandchildren).

My grandfather Levi Yitzchak obm:

Ask thy father and he will recount it to you / your elders and they will tell you (Deut. 32:7).

This grandfather was born and lived in Roman. A quintessential scholar, Reader, Cantor, and preacher, a brilliant orator with crowds flocking to hear him. He was fluent in the Hebrew language. In 1924 he published an article in the booklet Kibbutzei Ephraim titled “Tidbits of Wisdom”, in which he addresses an issue in the Tractate D'mai 7:6.

|

|

| Levi Yitzchak Weissbuch |

He was a well-known and revered figure in his city, and as Finco Pascal (16, p. 117) wrote. In 1903, he lectured and emphasized the role of culture among Jews and the need for unity among people. He was active in the community and a member of the Religious Committee (16, p. 45). I heard from my father that when he lay on his deathbed, two rabbis came to visit the sick. When my grandfather asked the rabbis to sit down, they refused and said that before a man who possesses the Torah like him, they must stand on their feet as they would do before a Torah scroll.

[Page 393]

My father Ephraim Ḥaim obm

The Glory of children are their fathers (Proverbs 17:6)

My father was born in March 1902, in Roman. At a tender age, my grandfather sent him to study at a yeshiva in Boju, where he learned and absorbed Torah from the great rabbis of the generation. He was only 16 years old when, with the special permission from the city's chief rabbi where he lived, he was appointed a Torah Reader and prayer leader, the youngest at the time. Since then, a long road has been paved that was all dedicated to doing the Creator's work and studying Torah.

Thus, as it was said, “Torah seeks its home” (Baba Metzia 85a); he was ordained in 1923 as rabbi after successfully passing the test for the degree (see document), and served as rabbi in the Kol Yisrael Haverim synagogue (16, p. 53). In 1927, he moved to Suceava and married my late mother, Hana. Before and after World War II, he taught Hebrew, Torah and religion, and there was hardly anyone of the young people in the city who were not among his pupils. He was active in the Mizrahi movement and had always aspired to emigrate to Eretz [Israel].

He was exiled with his family to Transnistria, in October 1941, and returned after liberation he returned to Suceava in May 1944. For almost 40 years he was a sexton (gabbai) in the GACH Synagogue, where he also the Reader and cantor.

When the Jewish school in Suceava allowed all those who had lost years of schooling because of the expulsion, to complete their studies, he was appointed as a teacher of Hebrew, religion and history of the Jewish People, while continuing to teach many children privately. After the school closed, he worked as an accountant but observed the sanctity of the Sabbath and the holidays (he worked on Sundays).

In September 1974, he emigrated to Israel with my mother. Here, he was a Reader, a prayer leader and a preacher at the Beit Yitzchak and Ohel Hedva Synagogue in Kiryat Ḥaim. Every Saturday after prayers, he sat with the congregation and discoursed about the reading or current events. On many Saturdays he preached before a Afternoon Prayer or at the se'udah shlishit meals at the Romanian synagogue in Kiryat Shmuel.